ABSTRACT

To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies assessing the association between serum vitamin D status and mortality in patients with COVID- 19. We searched PubMed and Embase for studies addressing the association of serum vitamin D levels and COVID-19 mortality published until April 24, 2022. Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence interval (CIs) were pooled using fixed or random effects models. The risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. The meta-analysis included 21 studies that measured serum vitamin D levels close to the date of admission, of which 2 were case- control and 19 were cohort studies. Vitamin D deficiency was associated with COVID-19 mortality in the overall analysis but not when the analysis was adjusted to vitamin D cutoff levels < 10 or < 12 ng/mL (RR 1.60, 95% CI 0.93-2.27, I2 60.2%). Similarly, analyses including only studies that adjusted measures of effect for confounders showed no association between vitamin D status and death. However, when the analysis included studies without adjustments for confounding factors, the RR was 1.51 (95% CI 1.28-1.74, I2 0.0%), suggesting that confounders may have led to many observational studies incorrectly estimating the association between vitamin D status and mortality in patients with COVID-19. Deficient vitamin D levels were not associated with increased mortality rate in patients with COVID-19 when the analysis included studies with adjustments for confounders. Randomized clinical trials are needed to assess this association.

Keywords: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; 25-hydroxyvitamin D; meta-analysis; systematic review; SARS-CoV-2

INTRODUCTION

Since the first case of COVID-19 was recorded in Wuhan (Hubei Province, China) in December 2019, SARS-CoV-2 infection has spread rapidly across the globe due to the strong contagious and infectious characteristics of this virus ( 1 , 3 ). Until May 13, 2022, COVID-19 has caused 6,216,708 deaths ( 4 ).

Global data from the pandemic has demonstrated a mortality rate of 0.9% in patients with COVID-19 and without comorbidities, but this rate grows progressively with the patients’ increasing age and number of comorbidities ( 5 ). Studies associating serum vitamin D levels with acute respiratory infections ( 6 ) have led to an ecological study, which showed that countries with populations with lower serum vitamin D levels have higher infection rates and mortality associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection ( 7 ). Additionally, Isaia and cols. ( 8 ) have found a correlation between higher levels of solar ultraviolet (UV) radiation in some regions and lower morbidity and mortality rates related to COVID-19. The authors hypothesized that this finding could be related to the vitamin D levels in the population.

Skin exposure to UV radiation determines the local photoconversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to previtamin D3 ( 9 ). Two forms of vitamin D are available, i.e. , D2 and D3, and the primary source of vitamin D3 – which comprises about 80% of the vitamin D stored in the body – derives from UV conversion ( 10 ). Vitamin D formed in the skin or obtained from diet is metabolized in the liver into 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D), which is the vitamin form used to determine a patient's vitamin D status. This form is then hydroxylated in the kidneys into the active form of the vitamin, i.e. , 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25[OH]2D).

Vitamin D status is defined according to 25(OH)D levels as insufficient when < 30 ng/mL, deficient when < 20 ng/mL, and severely deficient when < 10 ng/mL ( 11 , 12 ) or <12 ng/mL, according to some authors ( 13 , 14 ). Small observational studies analyzing the association of vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency with COVID-19 outcomes have shown conflicting results ( 15 , 19 ). Based on these considerations, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the association between vitamin D status and mortality in patients with COVID-19.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). This study has not been registered.

Data search

In November 2020, two of the investigators performed a search in PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases. Studies published until April 24, 2022, were included in the analysis. The following search strategy was used: “vitamin D” AND “coronavirus” OR “coronavirus infections” OR “COVID-19” OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2”. Among the articles identified in the search, only those published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese were included in the analysis.

Study selection

Two independent authors screened the retrieved arti- cles. Disagreements were resolved through discussion among all the authors. The authors read the abstracts of the retrieved articles and, after excluding irrelevant studies, proceeded to read the full article for screening.

For inclusion in the analysis, the studies should meet the following population, intervention, control, and outcomes (PICO) criteria: (A) include hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (must have included throat swabs for direct identification of upper respiratory SARS-CoV-2 infection using nucleic acid real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction [RT- PCR] to confirm the diagnosis of COVID-19); (B) include patients with COVID-19 older than 18 years and with vitamin D status identified as “deficient” or “insufficient” by measurement of serum vitamin D (25[OH]D) levels close to the date of the COVID-19 diagnosis (specifically, up to 30 days before or up to 7 days after the diagnosis); (C) enroll patients with COVID-19 and vitamin D status identified as “sufficient,” who were used for comparison; (D) examined the association between vitamin D status and mortality. Studies in which serum vitamin D levels measured at admission were not mentioned, letters to the editor, case reports, and articles reporting ecological, cross-sectional, animal model, or pediatric studies were excluded from the analysis.

Data extraction

The eligible studies included the assessment of death in individuals with measured serum vitamin D levels. The studies should have informed odds ratios (ORs), risk ratios (RRs), or hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The inclusion in the analysis was not restricted by study size.

The data extracted from the studies included information about the authors, study design, country of origin, patients’ demographic characteristics (age and sample size), COVID-19 diagnosis, outcomes, and confounders. Two independent investigators extracted the data using a structured form designed by the authors. Disagreements were resolved through discussion among all authors.

Analysis of results

The analysis focused on the impact of vitamin D deficiency on mortality outcomes in patients with COVID-19. For this, we first performed an analysis stratified by vitamin D cutoff level (< 20 or < 25 ng/mL and < 10 or < 12 ng/mL, according to each study). We then performed another stratified analysis including studies that adjusted analyses for confounding factors versus those that did not perform such adjustments. For the present meta-analysis, we standardized the vitamin D measurement unit as ng/mL, and for those studies with levels presented in nmol/L, we transformed the values into ng/mL ( 10 ). We also performed sensitivity analysis by omitting individual studies to detect the influence of each study on the overall effect estimate.

Quality assessment, risk of bias, and statistical analysis

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to evaluate the quality of observational studies. This scale assigns up to 9 points to each study (4 points for selection, 2 points for comparability, and 3 points for exposure or outcome) ( 20 ). Studies scoring at least 6 points are considered to have a low risk of bias. The studies included in the present meta-analysis reported ORs, HRs, or RRs; for studies not reporting these effects, the RR was calculated according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ( 21 ).

We extracted the effect estimates with the most significant degree of adjustment for potential confounding factors. We also considered HR comparable to RR. For studies reporting ORs, a corrected RR was computed as previously described ( 22 ). Pooled RRs and 95% CIs were calculated using fixed or random effects models according to the study's homogeneity. Cochran's Q test and I2 statistic were used to evaluate, respectively, the statistical significance and the degree of heterogeneity between the studies. An I2 statistic value ≥ 50% reveals substantial heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was also performed, removing each study from the meta-analysis to investigate the source of heterogeneity. Finally, publication bias was examined using Egger's test and funnel plot analysis. All analyses were performed using the software Stata/SE, v.14.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the selected studies

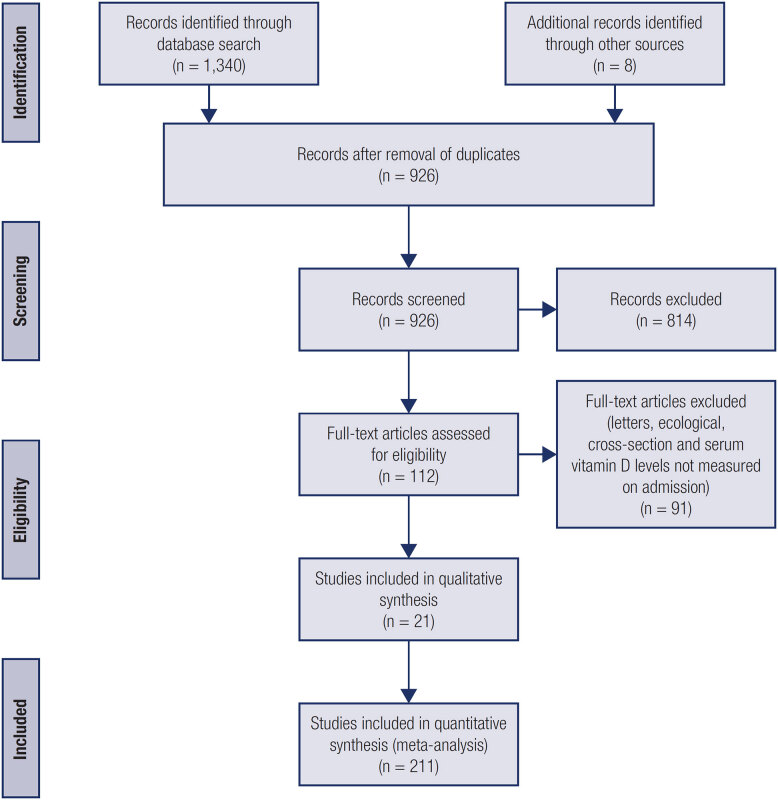

The database search identified 1,340 articles. Of these, 814 were duplicates or were excluded based on predetermined eligibility criteria during title/ abstract review. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we identified 21 articles ( 23 , 43 ) eligible for the present systematic review and meta- analysis ( Figure 1 ), which involved 6,096 participants. Among the identified articles, 19 were cohort studies ( 23 , 24 , 26 – 28 , 30 – 34 , 36 – 43 ) and two were case-control studies ( 25 , 35 ). Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the selected studies and study participants.

Figure 1. Flowchart of study selection.

Table 1. Characteristics of the selected studies.

| Author | Country | Study Design | Follow-up | Population | Age (years) * | Outcomes | Sample Size | Exposure, n (cutoff level) | Adjusted confounders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abrishami and cols., 2021 ( 23 ) | Iran | Retrospective cohort | February 28 2020 – April 19, 2020 | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | 55.18 ± 14.98 | Death and hospitalization | 73 | -Vitamin D≤ 25 ng/mL | Age, sex, and comorbidities |

| Afaghi and cols., 2021 ( 39 ) | Iran | Retrospective cohort | March 16 2020–February 25, 2021 | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | 53.7 ± 15.8 | ICU admission, invasive mechanical ventilation, duration of hospitalization, and death | 646 | 109(Vitamin D≤ 20 ng/mL) | Age, sex, and comorbidities |

| AlSafar and cols., 2021 ( 38 ) | United Arab Emirates | Retrospective cohort | August 2020 –February 2021 | Adult patients with COVID-19 | 46.6 ± 14.6 | Death and severity | 464 | 127 (Vitamin D≤ 12 ng/mL)182(Vitamin D≤ 20 ng/mL) | Age, sex, smoking status, and comorbidities |

| Baktash and cols., 2020 ( 24 ) | UK | Prospective cohort | March 1st–April 302020 | Patients aged ≥ 65 years hospitalized with COVID-19 | 81 (65-102) * | Mortality secondary to COVID-19; NIV support and admission to HDU, COVID-19 radiographic changes on chest X-ray | 70 | 39 (Vitamin D≤ 12 ng/mL) | Not adjusted |

| Barassi and cols., 2021 ( 33 ) | Italy | Prospective cohort | April 8 –May 25 2020 | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | 61 (24-92) * | Mortality | 118 | 87 (Vitamin D≤ 20 ng/mL) | Not adjusted |

| Bennouar and cols., 2021 ( 30 ) | Algeria | Prospective cohort | July 6 – August 15, 2020 | Patients with severe COVID-19 | 62.3 ± 17.6 | Mortality | 120 | 32 (Vitamin D≤ 10 ng/mL)35 (Vitamin D≤ 20 ng/mL) | Age, sex, acute kidney injury, cardiac injury, blood glucose, CRP, NLR, LDH, albumin, and total cholesterol |

| Cereda and cols., 2021 ( 31 ) | Italy | Cohort | March –April 2020 | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | 77 (65-85) * | Mortality | 129 | 99(Vitamin D< 20 ng/mL) | Age, CRP, and ischemic heart disease |

| Derakhshanian and cols., 2021( 41 ) | Iran | Retrospective cohort | February 20 2020–April 20, 2020 | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | 61.6 ± 16.9 | COVID-19 severity (death and ICU admission) | 290 | 142 (Vitamin D < 20 ng/mL) | Not adjusted |

| Güven & Gültekin 2021( 43 ) | Turkey | Retrospective cohort | March 1st–December 31st, 2020 | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | 64 (53-77) ** | Survival | 520 | 355 (Vitamin D< 12 ng/mL) | Age, sex, and comorbidities |

| Hafez and cols., 2022 ( 34 ) | United Arab Emirates | Retrospective cohort | April – May 2020 | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | 43 ± 12 | Severity | 126 | 10 (Vitamin D < 10 ng/mL)62(Vitamin D < 20 ng/mL) | Age, sex, race, and comorbidities |

| Hernández and cols., 2021( 25 ) | Spain | Case-control | March 10 –March 31st, 2020 | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | 61 (47.5-70) ** | COVID-19 severity (death, ICU admission, and NIV) | 216 | 162 (Vitamin D ≤ 20 ng/mL) | Age, sex, BMI, smoking, diabetes mellitus, history of cardiovascular events, oral vitamin D supplements, CRP, and GFR |

| Infante and cols., 2021 ( 40 ) | Italy | Retrospective cohort | March 1st –April 302020 | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | Survivors 65 ± 13 Non-survivors 70 ± 29 | Survival, length of stay in hospital and ICU | 137 | 69 (Vitamin D ≤ 10 ng/mL) | Not adjusted |

| Jain and cols., 2020 ( 26 ) | India | Prospective cohort | 6 weeks | Patients with COVID-19 aged 30-60 years | 51.41 ± 9.12 | Serum IL-6, serum TNF-alpha, serum ferritin, deaths, and serum level of vitamin D | 154 | 90 (Vitamin D< 20 ng/mL) | Not adjusted |

| Karahan & Katkat, 2021 ( 29 ) | Turkey | Retrospective cohort | April 1st–May 20 2020 | Adult patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 | 63.5 ± 15.3 | Mortality | 149 | 103 (Vitamin D < 20 ng/mL) | Age, smoking, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, chronic atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, acute kidney injury, eGFR, hemoglobin, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, white blood cell count, CRP, albumin, and calcium |

| Nimavat and cols., 2021 ( 35 ) | India | Case-control | August 1st–September 5, 2020 | Patients aged ≥18 years hospitalized with confirmed COVID-19 | 41.6 ± 16.4 | Mortality | 156 | 25 (Vitamin D < 10 ng/mL) | Not adjusted |

| Pecina and cols., 2021( 36 ) | USA | Retrospective cohort | April 16 –October 17, 2020 | Patients aged ≥18 years hospitalized with confirmed COVID-19 | 61 (50-74) ** | ICU mortality and duration of hospitalization | 92 | 15(Vitamin D < 20 ng/mL) | Not adjusted |

| Radujkovic and cols., 2020 ( 27 ) | Germany | Prospective cohort | March 18 –June 18 2020 | Inpatients and outpatients diagnosed with COVID-19 | 60 (49-70) ** | NVI and survival | 93 | 29 (Vitamin D< 12 ng/mL) 47(Vitamin D < 20 ng/mL) | Age, sex, and presence of comorbidity |

| Ramirez- Sandoval and cols., 2022 ( 42 ) | Mexico | Retrospective cohort | March 13 2020 –March 1st, 2021 | Patients with severe COVID-19 | 57 (46-67) ** | Survival and discharge | 2098 | 571 (Vitamin D< 12 ng/mL) | Age, sex, BMI, acute kidney injury, and diabetes |

| Reis and cols., 2021 ( 37 ) | Brazil | Prospective cohort | June 2nd July 21st, 2020, and July 22nd September 25th, 2020 | Patients aged ≥18 years hospitalized with confirmed COVID-19 | Vitamin D <10 ng/mL group: 61.3 ± 14.4 Vitamin D ≥10 ng/mL group: 54.7 ± 14.5 | Mortality and duration of hospitalization | 220 | 16 (Vitamin D < 10 ng/mL) | Not adjusted |

| Smet and cols., 2020 ( 28 ) | Belgium | Retrospective cohort | March 1st–April 7, 2020 | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | 69 (52-80) ** | COVID-19 severity (stage disease and death) | 186 | 109 (Vitamin D < 20 ng/mL) | Age, sex, coronary artery disease, and diabetes |

| Vassiliou and cols., 2021 ( 32 ) | Greece | Prospective cohort | March 18 –May 25 2020 | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | 61 ± 14 | Mortality and NIV | 39 | 32 (Vitamin D < 20 ng/mL) | Not adjusted |

Abbreviations – BMI: body mass index, CRP: C-reactive protein; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDU: high-dependency unit; TNF-alpha: tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL interleukin 6; ICU: intensive care unit; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; NLR: neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; NIV: noninvasive ventilation.

Data represented as mean ± standard deviation.

Data represented as median (interquartile range).

Serum vitamin D level and mortality in patients with COVID-19

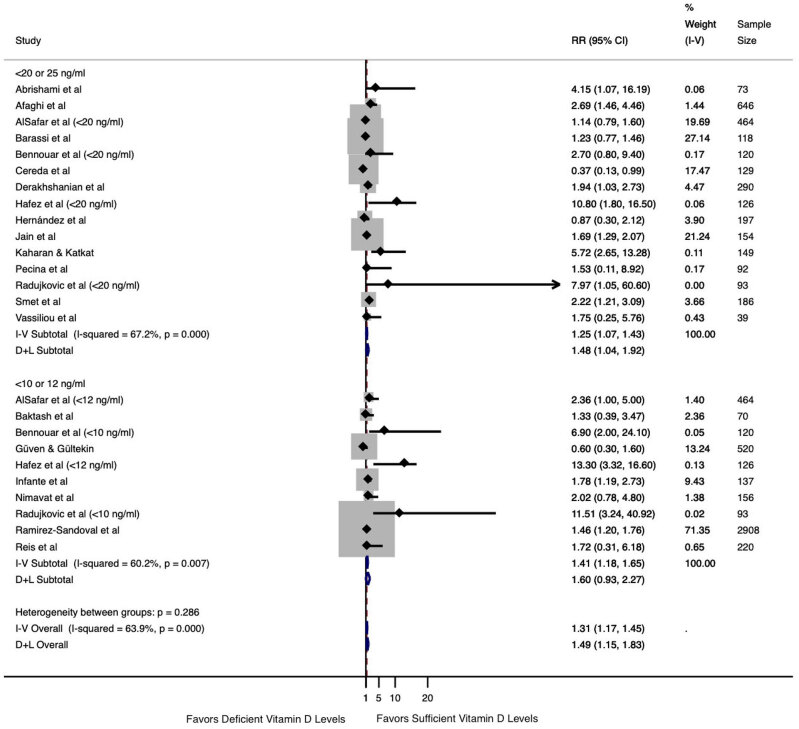

The mortality outcome was extracted from all 21 studies. The studies by AlSafar and cols. ( 38 ), Bennouar and cols. ( 30 ), Hafez and cols. ( 34 ), and Radujkovic and cols. ( 27 ) were included twice as they analyzed two vitamin D cutoff levels (< 10 or < 12 ng/mL and < 20 ng/mL). As shown in Figure 2 , the overall mortality analysis differed between patients with deficient vitamin D levels (regardless of cutoff level adopted) versus those with sufficient vitamin D levels (RR 1.49, 95% CI 1.15-1.83, I2 63.9%). Similarly, the analysis including the cutoff levels of < 20 or < 25 ng/mL indicated an increased risk of death (RR 1.48, 95% CI 1.04-1.92, I2 67.2%). However, the analysis including the cutoff levels of < 10 or < 12 ng/mL showed no difference between the groups with deficient versus sufficient vitamin D levels (RR 1.60, 95% CI 0.93-2.27, I2 60.2%).

Figure 2. Association between serum vitamin D levels and mortality in patients with COVID-19 according to 25(OH)D cutoff level.

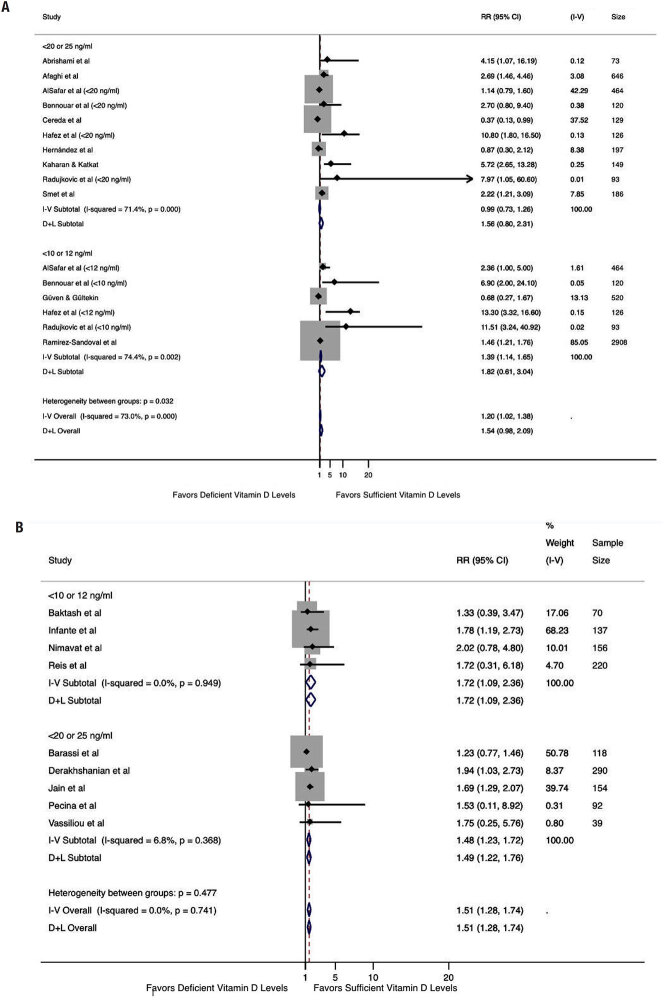

Subgroup analysis ( Figure 3A ) including studies performing analyses adjusted for age and at least one more confounding factor (obesity, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or cardiovascular disease) revealed no association between low vitamin D levels and death (RR 1.82, 95% CI 0.61-3.04, I2 74.4% for cutoff levels of < 10 or < 12 ng/mL and RR 1.56, 95% CI 0.80-2.31, I2 71.4% for cutoff levels of < 20 or < 25 ng/mL). In contrast, the analysis including studies not mentioning adjustment for confounders ( Figure 3B ), showed an increased risk of death for low vitamin D levels (RR 1.72, 95% CI 1.09-2.36, I2 0.0% for cutoff levels of < 10 or < 12 ng/mL and RR 1.48, 95% CI 1.23-1.72, I2 6.8% for cutoff levels of < 20 or < 25 ng/mL).

Figure 3. Association between serum vitamin D levels and mortality in patients with COVID-19, including studies that adjusted the analysis for age and at least one more confounder (obesity, hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, and cardiovascular disease) and studies without adjustment for confounders. (A) Analysis performed by 25(OH)D cutoff level, including only studies with adjustments; (B) analysis performed by 25(OH)D cutoff level, including studies without adjustments.

Sensitivity analyses, assessment of heterogeneity, and risk of bias

Sensitivity analysis was performed excluding, individually, each study that adjusted for confounding factors regarding the mortality outcome. The Cochran's Q test remained unchanged, and the I2 varied from 44.1%-78.5% for the cutoff levels of < 10 or < 12 ng/mL and 56.7%-74.5% for the cutoff levels of < 20 or < 25 ng/mL, indicating that the result was not influenced by heterogeneity ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. Sensitive analysis for the mortality outcome, including studies that performed adjusted analysis for confounders.

| Study omitted (25[OH]D < 10 or < 12 ng/mL) | RR | 95% CI | I2 | p value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlSafar and cols., 2021 | 1.76 | 0.33-3.18 | 78.5% | >0.05 |

| Bennouar and cols., 2021 | 1.77 | 0.54-2.99 | 78.5% | >0.05 |

| Güven & Gültekin 2021 | 3.90 | 0.96-6.90 | 73.2% | >0.05 |

| Hafez and cols., 2022 | 1.30 | 0.62-1.98 | 44.1% | >0.05 |

| Radujkovic and cols., 2020 | 1.78 | 0.57-2.99 | 78.3% | >0.05 |

| Ramirez-Sandoval and cols., 2022 | 3.99 | 0.66-7.23 | 77.8% | >0.05 |

| Study omitted (25[OH]D < 20 or < 25 ng/mL) | ||||

| Abrishami and cols., 2021 | 1.54 | 0.78-2.30 | 74.0% | >0.05 |

| Afaghi and cols., 2021 | 1.37 | 0.60-2.13 | 69.7% | >0.05 |

| AlSafar and cols., 2021 | 1.95 | 0.81-3.09 | 73.9% | >0.05 |

| Bennouar and cols., 2021 | 1.53 | 0.76-2.31 | 74.1% | >0.05 |

| Cereda and cols., 2021 | 1.90 | 0.98-2.85 | 56.7% | >0.05 |

| Hafez and cols., 2022 | 1.41 | 0.73-2.09 | 67.5% | >0.05 |

| Hernández and cols., 2021 | 1.78 | 0.88-2.69 | 74.5% | >0.05 |

| Kaharan & Katkat, 2020 | 1.46 | 0.73-2.20 | 71.9% | >0.05 |

| Radujkovic and cols., 2020 | 1.56 | 0.80-2.33 | 74.4% | >0.05 |

| Smet and cols., 2020 | 1.37 | 0.58-2.15 | 67.2% | >0.05 |

Abbreviation: 25(OH)D: 25-hydroyvitamin D.

Value for heterogeneity among studies assessed with Cochran's Q test.

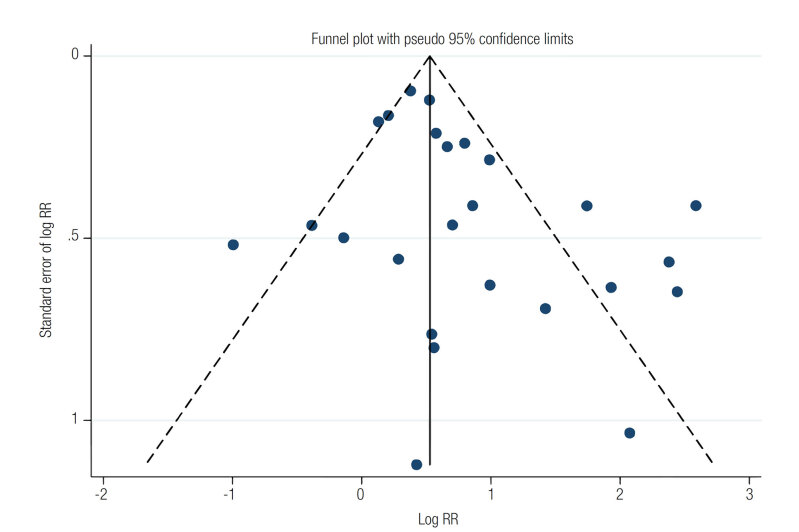

Table 3 shows the risk of bias in the analyzed studies. The median quality score of the studies was 8 (range 6-9). The estimated bias coefficient was 0.105, with a p value of 0.053, indicating the absence of small- study effects. The funnel plot analysis performed also detected no possible small-study effects ( Figure 4 ). Therefore, the tests provided weak evidence for the presence of publication bias.

Table 3. Quality assessment of the selected articles according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

| Case-control | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | Total points | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1A | 1B | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Hernández and cols., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 8 |

| Nimavat and cols., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Cohort | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total points | ||||||

| Studies | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1A | 1B | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Abrishami and cols., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Afaghi and cols., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| AlSafar and cols., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Baktash and cols., 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Barassi and cols., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Bennouar and cols., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Cereda and cols., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Derakhshanian and cols., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

| Güven & Gültekin 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Hafez and cols., 2022 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Infante and cols., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Jain and cols., 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Karahan & Katkat, 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Pecina and cols., 2021 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Radujkovic and cols., 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Ramirez-Sandoval and cols., 2022 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Reis and cols., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Smet and cols., 2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Vassiliou and cols., 2021 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

Abbreviations – N: no; Y: yes.

Figure 4. Funnel plot using data from 21 studies associating serum vitamin D levels and mortality. Four studies were included twice, as they analyzed two 25(OH)D cutoff levels.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis assessed only studies in which serum vitamin D levels were measured close to the date of the COVID-19 diagnosis. Observational studies have associated low serum vitamin D levels and poor outcomes in patients with COVID-19. However, many of these studies used the level measured between a few months and many years before the diagnosis of COVID-19 ( 44 , 45 ). Vitamin D has known biological variability, and its serum levels can vary from 13%-26% over 4 months. The levels can also vary with age and with the emergence of comorbidities ( 46 , 50 ).

Despite the overall analysis and the analysis by cutoff levels of < 20 or < 25 ng/mL showing an association between low serum vitamin D levels and mortality, the analysis by cutoff levels of < 10 or < 12 ng/mL did not reveal increased mortality risk. A possible explanation for the association between mortality and vitamin D deficiency for the < 20 or < 25 ng/mL group but not for the < 10 or < 12 ng/mL group in the meta-analysis lies in the weight of the studies that did not adjust their analyses for confounders (54.8% in the < 20 or < 25 ng/mL group versus 4.4% in the < 10 or < 12 ng/mL group), as discussed below. The subgroup analyses including studies that have adjusted the analysis for age and at least one more confounder did not show such association, both in the overall analysis and in the analysis by cutoff levels. However, one analysis including only studies not adjusting for confounders revealed an association between low serum vitamin D levels and an increased (1.51 times) risk of death, which suggests that confounding factors may have driven many results in previous studies. Therefore, our meta- analysis suggests that vitamin D status has no causal effect on mortality in patients with COVID-19.

Investigating the causality of the association between vitamin D status and severity of COVID-19 infection, Patchen and cols. studied single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) related to the risk of vitamin D deficiency. The authors found no association between genetically predicted differences in long-term vitamin D nutritional status and poor outcomes in patients with COVID-19 ( 51 ).

Hypovitaminosis D shares many risk factors with the severe form of COVID-19. Indeed, older age, obesity, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease are some critical risk factors that have been reported as associated with the severity of COVID-19 ( 52 , 55 ). Evidence indicates that vitamin D deficiency can be caused by older age, obesity, and chronic kidney disease ( 56 , 61 ). Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease also are associated with vitamin D deficiency ( 62 , 63 ). Thus, many confounders may compromise the analysis between serum vitamin D levels and COVID-19 outcomes, and the results of observational studies must be interpreted with caution. Despite the well-known modulatory role of vitamin D in the immune response, the participation of the vitamin in preventing mortality in patients with COVID-19 may be outweighed by other mechanisms involved in the complex pathophysiology of the disease ( 64 , 65 ).

Other hypotheses must also be considered to explain our results. The liver hydroxylates vitamin D into 25(OH)D (calcifediol), the circulating form of the vitamin, which has a plasma half-life of 3 weeks (the whole-body half-life of this form is 2-3 months) ( 66 ). The serum calcifediol levels are generally used to check an individual's vitamin D status. Calcifediol is hydroxylated into its active form – i.e. , 1,25(OH)2D–which has a plasma half-life of 4 hours; this half-life is related to the presence of this form of the vitamin mainly in the kidneys but also in some sites other than the kidneys, including pulmonary epithelial cells ( 10 , 66 ). The serum level of 1,25(OH)2D is roughly 1,000 times lower than that of calcifediol ( 67 ). The kidney is the main organ regulating serum 1,25 (OH)2D ( 68 ). The ACE2 protein, which is present in renal and lung cells, is a target for SARS-CoV-2 to enter these cells ( 69 , 70 ). Renal dysfunction caused directly by the virus or indirectly by the presence of acute renal injury associated with COVID-19 infection may lead to a reduction in the activity of 1-alpha hydroxylase, the enzyme that converts calcifediol to 1,25(OH)2D ( 71 , 72 ).

Another possible hypothesis to explain our findings is that tissue damage caused by SARS-CoV-2 in the kidneys and, to a lesser extent, in the lungs may lead to an active decrease in 1,25(OH)D levels, which are responsible for the majority of the biological actions of vitamin D, but does not result in decreased levels of the vitamin form usually measured in serum (calcifediol). Previous studies have shown that serum 25(OH)D levels may not correlate with serum 1,25(OH)2D levels in some clinical conditions ( 73 , 75 ).

Reduced calcium and phosphorus have been found in critically ill patients with COVID-19, which may indicate a reduction in 1,25(OH)2D in these patients since the active form of vitamin D is an essential regulator of calcium and phosphorus levels acting in intestinal absorption and renal reabsorption ( 68 ).

Despite the well-known autocrine and paracrine production of 1,25(OH)2D by immune system cells, it is difficult to identify whether serum 1,25(OH)2D levels influence the immune response against SARS- CoV-2. Playford and cols. have shown that serum levels of 1,25(OH)2D but not those of 25(OH)D are associated with cardiovascular risk factors, a common outcome in patients with severe COVID-19 ( 76 ). Likewise, Nguyen and cols. have found that serum 1,25(OH)2D levels are a better predictor of mortality by sepsis than those of calcifediol ( 77 ). Notably, an antiviral action has been proposed for 1,25(OH)2D against SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses ( 78 , 79 ).

The present study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of studies that have included the vitamin D status from serum 25(OH)D levels measured on or close to the date of hospital admission in patients with COVID-19 and the first to include studies with analyses adjusted for confounders. The main limitations of the present study were the fact that the analysis included different cutoff levels for serum vitamin D in the same subgroup, that vitamin D levels were measured 30 days before hospitalization for COVID-19 in one of the included studies ( 43 ), the presence of substantial heterogeneity, and the observational design of the selected studies.

In conclusion, the results of the present study showed that, overall, vitamin D status was associated with mortality in patients with COVID-19, but not when the analysis included studies that adjusted measures of effect for confounding factors. Confounders may have led to the conclusion of the detrimental effects of low serum 25(OH)D levels in patients with COVID-19 observed in some previous studies. Large randomized clinical trials are needed to assess the effects of vitamin D levels (including those of 1,25[OH]2D) on mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bogoch II, Watts A, Thomas-Bachli A, Huber C, Kraemer MUG, Khan K. Pneumonia of unknown aetiology in Wuhan, China: potential for international spread via commercial air travel. J Travel Med . 2020;2020:1–3. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol . 2020;92 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO WHO – Pneumonia of unknown cause – China [Internet] World Health Organization . 2020. [[cited 2020 Aug 16]]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/

- 4.WHO WHO Coronavirus Disease [Internet] WHO.int . 2020. [[cited 2020 Dec 19]]. pp. 1–1. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/

- 5.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med . 2020;46(5):846–848. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martineau AR, Jolliffe DA, Greenberg L, Aloia JF, Bergman P, Dubnov-Raz G, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory infections: Individual participant data meta-analysis. Health Technol Assess . 2019;23(2):1–44. doi: 10.3310/hta23020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilie PC, Stefanescu S, Smith L. The role of vitamin D in the prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 infection and mortality. Aging Clin Exp Res . 2020;32(7):1195–1198. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isaia G, Diémoz H, Maluta F, Fountoulakis I, Ceccon D, di Sarra A, et al. Does solar ultraviolet radiation play a role in COVID-19 infection and deaths? An environmental ecological study in Italy. Sci Total Environ . 2021;757:143757–143757. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norval M, Björn LO, De Gruijl FR. Is the action spectrum for the UV-induced production of previtamin D 3 in human skin correct? Photochem Photobiol Sci . 2010;9(1):11–17. doi: 10.1039/b9pp00012g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahota O. Understanding vitamin D deficiency. Age Ageing . 2014;43(5):589–591. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malabanan A, Veronikis IE, Holick MF. Redefining vitamin D insufficiency. Lancet . 1998;351(9105):805–806. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)78933-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holick MF. Vitamin D Deficiency. N Engl J Med. . 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amrein K, Scherkl M, Hoffmann M, Neuwersch-Sommeregger S, Köstenberger M, Tmava Berisha A, et al. Vitamin D deficiency 2.0: an update on the current status worldwide. Eur J Clin Nutr . 2020;74(11):1498–1513. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-0558-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cashman KD. Vitamin D Deficiency: Defining, Prevalence, Causes, and Strategies of Addressing. Calcif Tissue Int . 2020;106(1):14–29. doi: 10.1007/s00223-019-00559-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brenner H, Holleczek B, Schöettker B. Vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency and mortality from respiratory diseases in a cohort of older adults: potential for limiting the death toll during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients . 2020;12(8):2488–2488. doi: 10.3390/nu12082488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerget B, Kerget F, Kiziltunç A, Koçak AO, Araz Ö, Yilmazel Uçar E, et al. Evaluation of the relationship of serum vitamin d levels in covid-19 patients with clinical course and prognosis. Tuberk Toraks . 2020;68(3):227–235. doi: 10.5578/tt.70027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye K, Tang F, Liao X, Shaw BA, Deng M, Huang G, et al. Does Serum Vitamin D Level Affect COVID-19 Infection and Its Severity?-A Case-Control Study. J Am Coll Nutr . 2021;40(8):724–731. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2020.1826005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carpagnano GE, Di Lecce V, Quaranta VN, Zito A, Buonamico E, Capozza E, et al. Vitamin D deficiency as a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19. J Endocrinol Invest . 2021;44(4):765–771. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01370-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hastie CE, Mackay DF, Ho F, Celis-Morales CA, Katikireddi SV, Niedzwiedz CL, et al. Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev . 2020;14(4):561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta- analyses. Eur J Epidemiol . 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JP, Li T, Deeks JJ. Chapter 6: Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. Cochrane Training [Internet]. Cochrane . 2019. [[cited 2020 Jun 9]]. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-06 .

- 22.Zhang J. What's the Relative Risk?: A Method of Correcting the Odds Ratio in Cohort Studies of Common Outcomes. J Am Med Assoc . 2008;280(19):1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrishami A, Dalili N, Mohammadi Torbati P, Asgari R, Arab- Ahmadi M, Behnam B, et al. Possible association of vitamin D status with lung involvement and outcome in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study. Eur J Nutr . 2021;60(4):2249–2257. doi: 10.1007/s00394-020-02411-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baktash V, Hosack T, Patel N, Shah S, Kandiah P, Van Den Abbeele K, et al. Vitamin D status and outcomes for hospitalised older patients with COVID-19. Postgrad Med J . 2020;2:1–6. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernández JL, Nan D, Fernandez-Ayala M, García-Unzueta M, Hernández-Hernández MA, López-Hoyos M, et al. Vitamin D Status in Hospitalized Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J Clin Endocrinol Metab . 2021;106(3):e1343–e1353. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain A, Chaurasia R, Sengar NS, Singh M, Mahor S, Narain S. Analysis of vitamin D level among asymptomatic and critically ill COVID-19 patients and its correlation with inflammatory markers. Sci Rep . 2020;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77093-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radujkovic A, Hippchen T, Tiwari-Heckler S, Dreher S, Boxberger M, Merle U. Vitamin D deficiency and outcome of COVID-19 patients. Nutrients . 2020;12(9):1–13. doi: 10.3390/nu12092757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Smet D, De Smet K, Herroelen P, Gryspeerdt S. Serum 25(OH) D Level on Hospital Admission Associated With COVID-19 Stage and Mortality. Am J Clin Pathol . 2020;25:1–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karahan S, Katkat F. Impact of Serum 25(OH) Vitamin D Level on Mortality in Patients with COVID-19 in Turkey. J Nutr Health Aging . 2021;25(2):189–196. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1479-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennouar S, Cherif AB, Kessira A, Bennouar DE, Abdi S. Vitamin D Deficiency and Low Serum Calcium as Predictors of Poor Prognosis in Patients with Severe COVID-19. J Am Coll Nutr . 2021;40(2):104–110. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2020.1856013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cereda E, Bogliolo L, Klersy C, Lobascio F, Masi S, Crotti S, et al. Vitamin D 25OH deficiency in COVID-19 patients admitted to a tertiary referral hospital. Clin Nutr . 2021;40(4):2469–2472. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vassiliou AG, Jahaj E, Pratikaki M, Keskinidou C, Detsika M, Grigoriou E, et al. Vitamin D deficiency correlates with a reduced number of natural killer cells in intensive care unit (ICU) and non-ICU patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Hellenic J Cardiol . 2021;62(5):381–383. doi: 10.1016/j.hjc.2020.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barassi A, Pezzilli R, Mondoni M, Rinaldo RF, DavÌ M, Cozzolino M, et al. Vitamin D in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) patients with non-invasive ventilation support [Internet] Panminerva Med. . 2021 doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.21.04277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hafez W, Saleh H, Arya A, Alzouhbi M, Fdl Alla O, Lal K, et al. Vitamin D Status in Relation to the Clinical Outcome of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. Front Med . 2022;9:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.843737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nimavat N, Singh S, Singh P, Singh SK, Sinha N. Vitamin D deficiency and COVID-19: A case-control study at a tertiary care hospital in India. Ann Med Surg . 2021;68:102661–102661. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pecina JL, Merry SP, Park JG, Thacher TD. Vitamin D Status and Severe COVID-19 Disease Outcomes in Hospitalized Patients. J Prim Care Community Health . 2021;12:1–7. doi: 10.1177/21501327211041206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reis BZ, Fernandes AL, Sales LP, Santos MD, Dos Santos CC, Pinto AJ, et al. Influence of vitamin D status on hospital length of stay and prognosis in hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr . 2021;114(2):598–604. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqab151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alsafar H, Grant WB, Hijazi R, Uddin M, Alkaabi N, Tay G, et al. COVID-19 disease severity and death in relation to vitamin D status among SARS-CoV-2-positive UAE residents. Nutrients . 2021;13(5):1–14. doi: 10.3390/nu13051714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Afaghi S, Tarki FE, Rahimi FS, Besharat S, Mirhaidari S, Karimi A, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcomes of vitamin d deficiency in covid-19 hospitalized patients: A retrospective single-center analysis. Tohoku J Exp Med . 2021;255(2):127–134. doi: 10.1620/tjem.255.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Infante M, Buoso A, Pieri M, Lupisella S, Nuccetelli M, Bernardini S, et al. Low Vitamin D Status at Admission as a Risk Factor for Poor Survival in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19: An Italian Retrospective Study. J Am Coll Nutr . 2021;0(0):1–16. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2021.1877580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Derakhshanian H, Rastad H, Ghosh S, Zeinali M, Ziaee M, Khoeini T, et al. The predictive power of serum vitamin D for poor outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Food Sci Nutr . 2021;9(11):6307–6313. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramirez-Sandoval JC, Castillos-Ávalos VJ, Paz-Cortés A, Santillan-Ceron A, Hernandez-Jimenez S, Mehta R, et al. Very Low Vitamin D Levels are a Strong Independent Predictor of Mortality in Hospitalized Patients with Severe COVID-19: Hypovitaminosis D and COVID-19 mortality. Arch Med Res . 2022;53(2):215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Güven M, Gültekin H. Association of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Level with COVID-19-Related in-Hospital Mortality: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Am Coll Nutr [Internet] 2021. [[cited 2022 May 16]]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07315724.2021.1935361 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Hastie CE, Pell JP, Sattar N. Vitamin D and COVID-19 infection and mortality in UK Biobank. Eur J Nutr . 2021;60(1):545–548. doi: 10.1007/s00394-020-02372-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raisi-Estabragh Z, McCracken C, Bethell MS, Cooper J, Cooper C, Caulfield MJ, et al. Greater risk of severe COVID-19 in black, asian and minority ethnic populations is not explained by cardiometabolic, socioeconomic or behavioural factors, or by 25(OH)-vitamin D status: Study of 1326 cases from the UK biobank. J Public Health . 2020;42(3):451–460. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stamp TC, Round JM. Seasonal changes in human plasma levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Nature . 1974;24(5442):563–565. doi: 10.1038/247563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levis S, Gomez A, Jimenez C, Veras L, Ma F, Lai S, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and seasonal variation in an adult south Florida population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab . 2005;90(3):1557–1562. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brescia V, Tampoia M, Cardinali R. Biological Variability of Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Other Biomarkers in Healthy Subjects. Lab Med . 2013;44(1):20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jorde R, Sneve M, Hutchinson M, Emaus N, Figenschau Y. Grimnes G.Tracking of Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels During 14 Years in a Population-based Study and During 12 Months in an Intervention Study. Am J Epidemiol . 2010;171:903–908. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fontanive TO, Dick NRM, Valente MCS, dos Santos Laranjeira V, Antunes MV, de Paula Corrêa M, et al. Seasonal variation of vitamin D among healthy adult men in a subtropical region. Rev Assoc Med Bras . 2020;66(10):1431–1436. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.66.10.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patchen BK, Clark AG, Gaddis NM, Hancock DB, Cassano PA. Genetically predicted serum vitamin D and COVID-19: a Mendelian randomisation study. medRxiv [Internet] 2021. Available from: http://medrxiv.org/content/early/2021/02/01/2021.01.29.21250759 . abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Fang X, Li S, Yu H, Wang P, Zhang Y, Chen Z, et al. Epidemiological, comorbidity factors with severity and prognosis . 2020;12(13):12493–12503. doi: 10.18632/aging.103579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petrakis D, Margină D, Tsarouhas K, Tekos F, Stan M, Nikitovic D, et al. Obesity – a risk factor for increased COVID-19 prevalence, severity and lethality (Review) Mol Med Rep . 2020;22(1):9–19. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grasselli G, Greco M, Zanella A, Albano G, Antonelli M, Bellani G, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19 in Intensive Care Units in Lombardy, Italy Supplemental content. JAMA Intern Med . 2020;180(10):1345–1355. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z, Guo Q, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS- CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis . 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghotane SG, Challacombe SJ, Gallagher JE. Fortitude and resilience in service of the population: a case study of dental professionals striving for health in Sierra Leone. BDJ Open . 2019;5(1):7–7. doi: 10.1038/s41405-019-0011-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pereira-Santos M, Costa PRF, Assis AMO, Santos CAST, Santos DB. Obesity and vitamin D deficiency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev . 2015;16(4):341–349. doi: 10.1111/obr.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heaney RP, Horst RL, Cullen DM, Armas LAG. Vitamin D3 Distribution and status in the body. J Am Coll Nutr . 2009;28(3):252–256. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2009.10719779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walsh JS, Bowles S, Evans AL. Vitamin D in obesity. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes . 2017;24(6):389–394. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gallagher JC. Vitamin D and Aging. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am . 2013;42(2):319–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jean G, Souberbielle JC, Chazot C. Vitamin D in chronic kidney disease and dialysis patients. Nutrients . 2017;9(4):328–328. doi: 10.3390/nu9040328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mitri J, Pittas AG. Vitamin D and diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am . 2014;43(1):205–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skaaby T, Thuesen BH, Linneberg A. Vitamin D, cardiovascular disease and risk factors. Adv Exp Med Biol . 2017;996:221–230. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-56017-5_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Looman KIM, Jansen MAE, Voortman T, van den Heuvel D, Jaddoe VWV. Franco OH, et al.The role of vitamin D on circulating memory T cells in children: The Generation R study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol . 2017;28(6):579–587. doi: 10.1111/pai.12754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang TT, Nestel FP, Bourdeau V, Nagai Y, Wang Q, Liao J, et al. Cutting Edge: 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D 3 Is a Direct Inducer of Antimicrobial Peptide Gene Expression. J Immunol . 2004;173(5):2909–2912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martinaityte I, Kamycheva E, Didriksen A, Jakobsen J, Jorde R. Vitamin D stored in fat tissue during a 5-year intervention affects serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d levels the following year. J Clin Endocrinol Metab . 2017;102(10):3731–3738. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dusso AS, Brown AJ, Slatopolsky E. Vitamin D. Am J Physiol Physiol . 2005;289(1):F8–F28. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00336.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang C, Ma X, Wu J, Han J, Zheng Z, Duan H, et al. Low serum calcium and phosphorus and their clinical performance in detecting COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol . 2021;93(3):1639–1651. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Datta PK, Liu F, Fischer T, Rappaport J, Qin X. SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and research gaps: Understanding SARS-CoV-2 interaction with the ACE2 receptor and implications for therapy. Theranostics . 2020;10(16):7448–7464. doi: 10.7150/thno.48076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kai H, Kai M. Interactions of coronaviruses with ACE2, angiotensin II, and RAS inhibitors – lessons from available evidence and insights into COVID-19. Hypertens Res . 2020;43(7):648–654. doi: 10.1038/s41440-020-0455-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang CQ, Ma GZ, Tao MD, Ma XL, Liu QX, Feng J. The relationship among renal injury, changed activity of renal 1-α hydroxylase and bone loss in elderly rats with insulin resistance orType 2 diabetes mellitus. J Endocrinol Invest . 2009;32(3):196–201. doi: 10.1007/BF03346452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Werion A, Belkhir L, Perrot M, Schmit G, Aydin S, Chen Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 causes a specific dysfunction of the kidney proximal tubule. Kidney Int . 2020;21(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Christensen MHE, Lien EA, Hustad S, Almås B. Seasonal and age-related differences in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone in patients from Western Norway. Scand J Clin Lab Invest . 2010;70(4):281–286. doi: 10.3109/00365511003797172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fleet JC, Replogle RA, Reyes-Fernandez P, Wang L, Zhang M, Clinkenbeard EL, et al. Gene-by-diet interactions affect serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels in male BXD recombinant inbred mice. Endocrinology . 2016;157(2):470–481. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li CH, Tang X, Wasnik S, Wang X, Zhang J, Xu Y, et al. Mechanistic study of the cause of decreased blood 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D in sepsis. BMC Infect Dis . 2019;19(1):1020–1020. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4529-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Playford MP, Dey AK, Zierold C, Joshi AA, Blocki F, Bonelli F, et al. Serum active 1,25(OH) 2 D, but not inactive 25(OH)D vitamin D levels are associated with cardiometabolic and cardiovascular disease in psoriasis. Atherosclerosis . 2019;289:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nguyen HB, Eshete B, Lau KHW, Sai A, Villarin M, Baylink D. Serum 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D: An Outcome Prognosticator in Human Sepsis. PLoS Med . 2013;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee C. Controversial effects of vitamin d and related genes on viral infections, pathogenesis, and treatment outcomes. Nutrients . 2020;12(4):962–962. doi: 10.3390/nu12040962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mok CK, Ng YL, Ahidjo BA, Hua Lee RC, Choy Loe MW, Liu J, et al. Calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D, is a promising candidate for COVID-19 prophylaxis. medRxiv . 2020 [Google Scholar]