ABSTRACT

The successful employment of messenger RNA (mRNA) as vaccine therapy for the prevention of COVID-19 infection has spotlighted the attention of scientific community onto the potential clinical application of these molecules as innovative and alternative therapeutic approaches in different fields of medicine. As therapy, mRNAs may be advantageous due to their unique biological properties of targeting almost any genetic component within the cell, many of which may be unreachable using other pharmacological/therapeutic approaches, and encoding any proteins and peptides without the need for their transport into the nuclei of the target cells. Additionally, these molecules may be rapidly designed/produced and clinically tested. Once the chemistry of the RNA and its delivery system are optimized, the cost of developing novel variants of these medications for new selected clinical disorders is significantly reduced. However, although potentially useful as new therapeutic weapons against several kidney diseases, the complex architecture of kidney and the inability of nanoparticles that accommodate oligonucleotides to cross the integral glomerular filtration barrier have largely decreased their potential employment in nephrology. However, in the next few years, the technical improvements in mRNA that increase translational efficiency, modulate innate and adaptive immunogenicity, and increase their delivery at the site of action will overcome these limitations. Therefore, this review has the scope of summarizing the key strengths of these RNA-based therapies and illustrating potential future directions and challenges of this promising technology for widespread therapeutic use in nephrology.

Keywords: in vitro transcription, kidney diseases, mRNA-based therapies, nephrology, translational medicine

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, messenger RNA (mRNA) has been recognized as a potential therapeutic tool against several intractable or genetic diseases (comprising genetic/hereditary kidney diseases) and, thanks to the rapid development of innovative technological skills for its large-scale production, it has been successfully employed as vaccine therapy against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

mRNAs as therapy could target almost any genetic component within the cell, many of which are unreachable using other technologies (including both small molecules and antibodies), and encode proteins/peptides in the cytoplasm of the target cells without being transported into the nuclei (thus allowing protein production in post-mitotic cells) [1]. Therapeutic applications of mRNAs include: synthesis of a single protein for replacing the function in the case of monogenic disease; mRNA coding for transcription or growth factor used to modulate cell behavior; and mRNA-encoded factors involved in immune response.

The advantages of mRNAs include the low risk of adverse effects and toxicities because of their transient nature, and absence of insertional mutagenesis because they do not integrate into the genome [1, 2].

mRNA is easily synthesized through the in vitro transcription (IVT) process and is more effective, rapid in design and production, flexible, and cost-effective than conventional therapeutics [3]. In fact, once the chemistry of the RNA and its delivery system are optimized, the cost of developing novel variants of these medications for new selected clinical disorders is significantly reduced.

Nevertheless, several challenges have significantly hampered the employment of mRNA as a therapy in medicine [4]. First, mRNA is vulnerable to ubiquitous RNases which are highly abundant in the extracellular space and tissues; secondly, due to its negative charge, it cannot be easily transported across the cell membrane [5]; and finally, mRNA is able to stimulate the innate immune system [6–9] by activating Toll-like receptors and pattern recognition receptors.

Thanks to the recent advances in bioinformatics and nanotechnology these hurdles have been, at least partially, overcome leading to an increase in the potential applications of mRNA therapeutics.

MAIN STRATEGIES TO MANUFACTURE, AND REDUCE IMMUNOGENICITY, IMPROVE INTRACELLULAR STABILITY AND FACILITATE DELIVERY OF mRNA

Synthesis and optimization of mRNA

After IVT mRNA synthesis, using linearizing plasmid DNA or a PCR product as template and T3, T7 or SP6 RNA polymerase, a capping step is required to avoid degradation of mRNA by RNase and/or activation of the immune system by the 5′-ppp group [10, 11].

The capping of mRNA can be performed through a co-transcriptional or a post-transcriptional method [12, 13]. The latter uses capping enzymes from vaccinia virus that add a 7-methylguanosine cap at the 5′ end of the RNA using GTP and S-adenosyl methionine as donors (Cap 0 structure). Furthermore, 2′ ribose position of the first cap-proximal nucleotide is 2′O-methylated to form a Cap 1 structure (m7GpppN2′OmN), and, in ∼50% of transcripts, the second cap-proximal nucleotide is 2′O-methylated to form a Cap 2 structure (m7GpppN2′OmN2′Om), which reduces mRNA immunogenicity [14, 15].

Unfortunately, because of the presence of a 3′-OH on both the 7-methylguanosine and guanosine moieties, up to half of the mRNAs contain caps incorporated in the reverse orientation, which cannot be recognized by the ribosome and hinder overall mRNA translation activity [15–19]. This problem was overcome by the introduction in the transcription reaction of anti-reverse cap analogs bearing modified m7G at the 2′ or 3′ position (2′-O-methyl, 3′-O-methyl, 3′-H) ensuring correct orientation and higher translation efficiency [20, 21].

The mature mRNA also includes a 3′ poly(A) tail that can be added post-transcriptionally using the poly-A-polymerase enzyme or incorporated in the DNA template [1, 22, 23]. Optimization of the poly(A) tail length (100–300 nucleotides) has proven critical in balancing the translation efficacy of mRNAs [24–26].

Furthermore, other modifications that can enhance translational efficiency and reduce immunogenicity include changes in the open reading frame by replacing rare codons with more frequently occurring variants (codon optimization) [27], elimination of structural motifs able to activate innate immune response and the introduction of chemical alterations that render the mRNA more similar to an endogenous molecule [28–30].

Purification of mRNA

After synthesis, IVT mRNA is mixed with unwanted side products such as DNA templates, short mRNA, uncapped mRNA, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and mRNA fragments. All these contaminant impurities must be removed in order to avoid interference with mRNA translation, activation of innate immunity or overestimation of the total functional mRNA cargo [25, 31, 32].

Purification of IVT mRNA can be carried out by different procedures, including acidic phenol-chloroform extraction, precipitation with LiCl, elution based on silica matrices or chromatographic methods [33]. All these procedures eliminate proteins, nucleotides and other components of the IVT reaction but cannot remove dsRNA impurities.

The established way to eliminate dsRNA contaminants from long IVT mRNAs is by using ion pair reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [31, 34]. However, this method has some disadvantages: it is not scalable, the toxic effects of acetonitrile and the high cost [31, 35].

Based on the selective binding of dsRNA to cellulose in ethanol-containing buffer, Baiersdörfer et al. [35] have developed a feasible cellulose-based chromatography method for the elimination of dsRNA contaminants with a quality comparable to that of the corresponding HPLC-purified mRNA.

Another possible approach is to use the dsRNA-specific nuclease RNase III [36]. A potential drawback is that this enzyme may cleave the double-stranded secondary structure formed by single-stranded RNA.

Finally, short RNAs can be removed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) followed by excision and elution of the band of interest from the gel, and long RNAs can be separated by denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis [37, 38].

Delivery methods for mRNA

Targeted delivery of IVT mRNA is a great challenge for the in vivo application of mRNA-based therapeutics. The large molecular weight (approximately 1–15 kb) [27] and high negative charge of this nucleic acid impair its permeation across cellular membranes [39]. Moreover, it is highly susceptible to degradation by nucleases and its median intracellular half-life is only approximately 7 h [40]. Therefore, different strategies have been developed to protect mRNA from degradation and optimize its delivery at the tissue target [27].

In general, IVT mRNA delivery can be obtained by three strategies: physical methods, viral-based approaches and nonviral vectors.

Physical methods such as electroporation (which uses high voltage electric pulse to increase cell permeability) transiently disrupt the barrier function of the cell membrane with frequent damage to the cells, and are therefore not suitable for in vivo applications [41, 42].

The recombinant viruses use the naturally occurring biological modes of uptake but are associated with several limitations such as potential reverse genome insertional risks, difficulties in controlling the gene expression and vector-size limitations, as well as strong immunologic side effects [43, 44].

The nonviral vectors that use rationally designed and easily developed chemical nanocarriers have huge potential for the delivery of nucleic acids [42].

One of the most well-developed methods for mRNA delivery is co-formulation into lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [45], typically composed of four components: (i) neutrally charged phospholipids (structural lipids); (ii) cholesterol as a stabilizing agent for the lipid bilayer; (iii) pH-sensitive ionizable cationic lipids needed for the loading of negatively charged nucleic acids into LNPs; and (iv) stealth lipids (mainly polyethylene glycol (PEG) polymer–conjugated lipids) to reduce immunogenicity [46–48].

More recently, the use of lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles, which integrate the properties of lipids with polymeric nanomaterials, has shown higher efficiency of mRNA delivery [49].

A critical hinderance for the correct delivery of LNPs is their rapid uptake by antigen-presenting cells and macrophages. The usual approach to prolong the circulation of mRNA-loaded LNPs is the addition of PEG units on the surface of LNPs which cause formation of a hydration layer that prevents clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system [50]. Moreover, the addition of a ligand to cell-membrane to imitate “self” materials can avoid the uptake by phagocytes [51, 52].

More recently, other new procedures, developed for delivery of nanoparticle-based drugs, include the mononuclear phagocyte system blockade by low-toxicity “blocking” agents [53], macrophage depletion by means of the administration of clodronate/gadolinium chloride [54] and pre-induced depletion of erythrocytes by administration of a low dose of allogeneic anti-erythrocyte antibodies [55, 56]. It is plausible that these methods could be used in future also to prolong the circulation time of mRNA and to optimize delivery to target tissue.

To efficiently reach their target to deliver the cargo, LNPs can be also conjugated with specific ligands to the surface that help the identification and the uptake by the intended cells. These ligands can be peptides, antibodies, nucleic acid aptamers, carbohydrates or small molecules [22].

Other systems developed as alternatives to LNPs are biological delivery vehicles such as cells or extracellular vesicles. The main advantages of this methodology comprise biocompatibility, wide range of customization, extended longevity in circulation and reduced toxicity [57–60].

However, current challenges in their clinical use include the characterization, the isolation method and their purification [61, 62].

DELIVERY METHODS FOR mRNA THERAPY IN KIDNEY DISEASES

mRNA delivery in the kidney is difficult due to its architecture and the large number of different cell types within the organ [22]. Moreover, the glomeruli that eliminate proteins above 50 kDa and the slit diaphragm with a diameter of 10 nm prevent entry of most molecular therapies from the blood into the kidney [63].

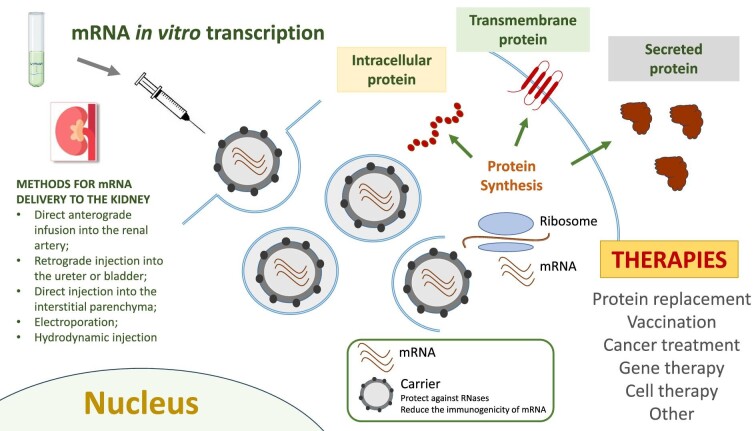

Some methods previously developed for gene therapy in kidney diseases can be used for mRNA delivery into the kidney: direct anterograde infusion into the renal artery targeting the glomeruli and tubular epithelium; retrograde injection into the ureter or bladder, and directly into the interstitial parenchyma [64].

In particular, recently, renal artery injection of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β/Smad-small interfering RNA (siRNA) has been used for the treatment of glomerulonephritis and renal vein injection of FAS-siRNA for improving survival after ischemia/reperfusion injury in mouse models [65, 66].

Other ways to directly deliver drug to kidney include physical methods such as electroporation [67], pressure stimulation, hydrodynamic injection, magnetically guided oligonucleotide-loaded nanoparticles [68], light-triggered lipid-based nanoparticles and aptamers, which have been applied to cancer therapy [69, 70] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1:

A schematic representation of the steps of mRNA therapy in kidney diseases. After IVT, mRNA is purified and administered via several possible routes (direct anterograde infusion into the renal artery; retrograde injection into the ureter or bladder; direct injection into the interstitial parenchyma; electroporation; hydrodynamic injection) to reach the kidney. Once in the organ, mRNA is translated by ribosomes in cytoplasmatic, transmembrane or secreted proteins. The potential applications of this therapy are: protein replacement, vaccination, cancer treatment, gene therapy and cell therapy.

Electroporation has been used for delivery of siRNA targeting TGF-β1 to the kidney to reduce the progression of matrix expansion in an animal model of glomerulonephritis [67]. However, membrane destruction associated with this method may lead to the loss of cytoplasmic content with significant cytotoxicity [71].

Pressure stimulation such as pushing or suction after normal intravenous injection has been previously tested to introduce plasmid DNA (pDNA) or siRNA into the kidney with good efficiency and no renal dysfunction [72, 73].

The addition of hydrodynamic injection to pressure stimulation has recently been developed to administer mRNA-loaded polyplex nanomicelles via renal pelvis injection into the kidney [74, 75]. The administration of mRNA-loaded nanomicelles by this route in kidneys of ICR mice induced protein expression in a greater number of tubular epithelium cells for some days compared with naked pDNA and naked mRNA, although introduced in the same way [75]. The renal function after administration remained similar to those of the sham-operated controls, without marked changes in histological sections, demonstrating the safety of the methodology.

In order to efficiently reach their target tissue, the nanoparticles containing the IVT mRNA can be conjugated with specific ligands (peptides, antibodies, nucleic acid aptamers or small molecules) to the surface that help the identification and the uptake by the intended cells [22]. Nevertheless, none of them has yet been used for mRNA delivery, but we expect that they could be employed in the future.

For example, the cyclo-(Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe-Cys) peptide has been used as a specific ligand of αvβ3 integrin receptor on the podocyte surface [76]. Likewise, megalin in the proximal tubular cells has been used as a target for specific peptides [77].

Antibodies can be attached to the delivery vehicle by means of Fc-binding peptides in combination with a surface linker [78]. In addition, the LNPs can be noncovalently coated with targeting antibodies via a recombinant lipoprotein (named ASSET) that is incorporated into siRNA-loaded LNP and interacts with the antibody Fc domain [79]. Several studies have also developed the use of antibody fragments instead of whole immunoglobulins in order to reduce immunogenicity, increase loading capacities and, thereby, improve the efficacy [80]. This methodology has been used for anti-cancer and siRNA therapies [81].

Aptamers are short single-stranded oligonucleotides that can bind specific proteins to modulate their functions. For example, Emapticap pegol (NOX-E36) is an RNA aptamer that binds and inhibits the C-C motif ligand 2, currently in phase II trials for type 2 diabetes mellitus and albuminuria [82]. Aptamers are characterized by high affinity for their target molecules, being nonimmunogenic and, due to their small size, being able to bind to sites inaccessible to larger antibodies, and rapid synthesis and lower manufacturing costs [83].

THE APPLICATION OF mRNA-BASED THERAPIES IN KIDNEY DISEASES: SOME INITIAL EXAMPLES

No mRNA therapies for the kidney have yet been introduced in the clinic, and preclinical studies are very limited. However, the employment of these RNA-based therapies on systemic diseases with secondary kidney involvement (including primary oxaluria and Fabry disease) appears more promising.

Recently, Zhu et al. [84] carried out a preclinical study involving Fabry disease, a lysosomal storage disorder caused by the deficiency of alpha-galactosidase, which leads to cellular accumulation of glycosphingolipid [particularly globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) and the deacylated Gb3 analog globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3)], and progressive damage in tissues such as kidney, heart and skin [85]. The mRNA encoding human alpha galactosidase A (h-α-Gal A), synthesized in vitro and packaged into LNP, was administered intravenously in α-Gal A–deficient Fabry mouse model at three different dosages, 0.5, 0.1 and 0.05 mg/kg. A single dose resulted in an increment in protein activity and glycosphingolipid reduction in tissues and plasma for up to 6 weeks. Likewise, repeated administration of 0.2 mg/kg or 0.5 mg/kg h-α-Gal A mRNA every week or 0.5 mg/kg h-α-Gal A mRNA every month for 3 months restored α-Gal A activity in tissues and reduced lyso-Gb3 and Gb3 in a dose-dependent manner.

The same procedure in non-human primates (0.5 mg/kg intravenously every week for four doses) confirmed the results obtained in mice, with the absence of an immune response to the protein encoded by the mRNA [84].

Another lysosomal storage disease with mRNA therapy preclinical study is cystinosis, caused by mutations in the cystinosin (CTNS) gene and consequent intra-lysosomal cystine accumulation. It initially affects the kidneys with defective proximal tubular reabsorption (renal Fanconi syndrome) and glomerular damage leading to kidney failure [86, 87].

Direct injection of CTNS mRNA (500 ng/mL) in a zebrafish model for cystinosis (ctns -/-) improved proximal tubular uptake of low molecular weight dextran (a marker for proximal reabsorption) and reduced overall proteinuria [88].

Kidney injury is also one of the symptoms of methylmalonic acidemia/aciduria (MMA), an autosomal recessive disease due to partial or complete deficiency of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (MUT), a vitamin B12-dependent mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes the isomerization of methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA, the final step in the oxidation of odd-chain fatty acids, the amino acids valine, isoleucine, methionine and threonine, and cholesterol, providing metabolites for the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Other symptoms include growth retardation, acute metabolic decompensation with acidosis, vomiting, dehydration, hepatomegaly and psychomotor retardation with cognitive dysfunction. The intravenous administration of a single dose of human MUT (hMUT) mRNA (0.5 mg/kg) packaged into LNP in MMA mouse models resulted in 75%–85% reduction in plasma methylmalonic acid and was associated with increased hMUT protein expression and activity in the liver and substantially improved the biochemical abnormalities characteristic of the disorder [89].

The RNA technology can also be used for CKD-related comorbidities such as hypertension. In a recent phase I study, zilebesiran, an RNA interference therapeutic agent designed to achieve specific reduction in hepatic angiotensinogen mRNA levels, when administered to patients with hypertension induced dose-related decrease in both serum angiotensinogen levels and blood pressure after single subcutaneous doses. This effect was sustained for up to 24 weeks [90]. The great advantage of this agent is the specific hepatic target which limits the consequences of off-target renal renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibition [90].

Another interesting application of mRNA as therapy is mRNA-based vaccines against infectious diseases and several types of cancer [91]. Two mRNA vaccines have been developed to treat renal cell carcinoma (RCC). The first is an in vitro transcribed naked mRNA, generated using plasmids coding for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her-2/neu), carcinoembryonic (CEA), tumor-associated antigens mucin 1 (MUC1), telomerase, survivin and melanoma-associated antigen 1 (MAGE-A1). The trial involved 30 metastatic RCC (mRCC) patients divided into two cohorts. The vaccine was administered on Days 0, 14, 28 and 42 (20 μg/antigen) in the first 14 patients (Cohort A) and at Days 0–3, 7–10, 28 and 42 (50 μg/antigen) in the consecutive 16 patients (Cohort B) [92, 93]. In both cohorts, after this induction period, vaccinations were repeated monthly until tumor progression. The treatment was safe and well tolerated with no relevant side effects, and the median survival was longer than predicted according to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) risk score. Interestingly, the long-term survival update (after 10 years) showed a clear correlation with CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to tumor-associated antigens encoded by the naked mRNA vaccine [93].

More recently, in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), the identification of four genes [neutrophil cytosol factor 4 (NCF4), formin-like protein 1 (FMNL1), DNA topoisomerase II alpha (TOP2A) and docking protein 3 (DOK3)] significantly up-regulated, positively associated with antigen-presenting cell infiltration and associated with decreased survival probability, suggested their use as potential effective neoantigens for KIRC mRNA vaccine development [94].

AGS-003 is an autologous dendritic cell vaccine prepared ex vivo from mature monocyte-derived dendritic cells (DCs) co-electroporated with the patient's amplified tumor RNA and synthetic CD40L RNA [95, 96]. When administered by intradermal injection, these RNA-loaded mature DCs are capable of presenting relevant patient-specific tumor antigens via major histocompatibility complex Class I presentation to T cells in the draining lymph node. Intradermal injections of AGS-003 in combination with sunitinib (the first-line treatment of mRCC) in an unselected, intermediate and poor-risk mRCC patient population was associated with a doubling of expected survival, encouraging long-term and 5-year overall survival, and an excellent safety profile [97]. These results have encouraged the current phase III (NCT01582672) trial.

However, more studies should be performed to assess the safety of this therapeutic approach. In fact, in the last few months, de novo vasculitis, cases of minimal change disease, acute interstitial nephritis and occasional recurrence of primary disease have been described after mRNA-based vaccines [98, 99]. Moreover, it is important to note that there are some limitations to its use. For example, the approved COVID-19 vaccines can be stored for several months depending on the formulation, but only at extremely low temperatures below freezing, which can lead to logistical barriers to distribution in certain areas. Furthermore, the need for multiple doses of the mRNA vaccines may pose a challenge for people to complete the series of their immunizations. There is also ongoing research looking into the duration of mRNA vaccines, as their development is still in early stages compared with other vaccines and more research is needed before they can widely be used for additional viral diseases.

Finally, at the moment, there is no specific guidance from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or European Medicines Agency (EMA) for mRNA products. However, there are numerous clinical trials, in particular for mRNA-based vaccines, under EMA and FDA oversight demonstrating that products are safe and acceptable for testing in humans [91]. Additionally, since mRNA can be considered a gene therapy product, the recommendations defined for DNA vaccines and gene therapy vectors can be applied, at least partially, to mRNA. However, it is likely that specific guidelines will be developed in the future to regulate the manufacture, quality control testing and administration of mRNA as therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

Although the use of mRNA therapy is a new, valid and potential therapeutic weapon against a series of pathologies and can represent a valid alternative to classical therapy, many doubts still exist about its use for the treatment of renal pathologies. Instead, its application for treating systemic diseases appears much more promising.

It is necessary to intensify research in this field and to start studies and clinical trials in order to assess the real potential of mRNA therapy in nephrology.

However, we expect that in the future, this technology could represent a therapy for many rare and neglected genetic kidney diseases. However, some hurdles should be overcome to permit the dissemination of its employment in several clinical settings.

Contributor Information

Simona Granata, Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation Unit, Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Foggia, Foggia, Italy.

Giovanni Stallone, Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation Unit, Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Foggia, Foggia, Italy.

Gianluigi Zaza, Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation Unit, Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Foggia, Foggia, Italy.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

There were no data generated or analysed during the current review.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sahin U, Karikó K, Türeci Ö. mRNA-based therapeutics—developing a new class of drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014;13:759–80. 10.1038/nrd4278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Newbury SF. Control of mRNA stability in eukaryotes. Biochem Soc Trans 2006;34:30–4. 10.1042/BST0340030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beckert B, Masquida B. Synthesis of RNA by in vitro transcription. Methods Mol Biol 2011;703:29–41. 10.1007/978-1-59745-248-9_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weng Y, Li C, Yang T et al. The challenge and prospect of mRNA therapeutics landscape. Biotechnol Adv 2020;40:107534. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dowdy SF. Overcoming cellular barriers for RNA therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol 2017;35:222–9. 10.1038/nbt.3802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R et al. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by toll-like receptor 3. Nature 2001;413:732–8. 10.1038/35099560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H et al. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science 2004;303:1529–31. 10.1126/science.1093616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science 2004;303:1526–9. 10.1126/science.1093620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sergeeva OV, Koteliansky VE, Zatsepin TS. mRNA-based therapeutics—advances and perspectives. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2016;81:709–22. 10.1134/S0006297916070075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pichlmair A, Reis e Sousa C. Innate recognition of viruses. Immunity 2007;27:370–83. 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hornung V, Ellegast J, Kim S et al. 5′-Triphosphate RNA is the ligand for RIG-I. Science 2006;314:994–7. 10.1126/science.1132505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muttach F, Muthmann N, Rentmeister A. Synthetic mRNA capping. Beilstein J Org Chem 2017;13:2819–32. 10.3762/bjoc.13.274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ouranidis A, Vavilis T, Mandala E et al. mRNA therapeutic modalities design, formulation and manufacturing under Pharma 4.0 principles. Biomedicines 2021;10:50. 10.3390/biomedicines10010050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jackson NAC, Kester KE, Casimiro D et al. The promise of mRNA vaccines: a biotech and industrial perspective. NPJ Vaccines 2020;5:11. 10.1038/s41541-020-0159-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galloway A, Cowling VH. mRNA cap regulation in mammalian cell function and fate. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 2019;1862:270–9. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stepinski J, Waddell C, Stolarski R et al. Synthesis and properties of mRNAs containing the novel “anti-reverse” cap analogs 7-methyl(3′-O-methyl)GpppG and 7-methyl (3′-deoxy)GpppG. RNA 2001;7:1486–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peng ZH, Sharma V, Singleton SF et al. Synthesis and application of a chain-terminating dinucleotide mRNA cap analog. Org Lett 2002;4:161–4. 10.1021/ol0167715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kore AR, Shanmugasundaram M, Vlassov AV. Synthesis and application of a new 2′,3′-isopropylidene guanosine substituted cap analog. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2008;18:4828–32. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jemielity J, Fowler T, Zuberek J et al. Novel “anti-reverse” cap analogs with superior translational properties. RNA 2003;9:1108–22. 10.1261/rna.5430403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kocmik I, Piecyk K, Rudzinska M et al. Modified ARCA analogs providing enhanced translational properties of capped mRNAs. Cell Cycle 2018;17:1624–36. 10.1080/15384101.2018.1486164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Decroly E, Ferron F, Lescar J et al. Conventional and unconventional mechanisms for capping viral mRNA. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012;10:51–65. 10.1038/nrmicro2675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bondue T, van den Heuvel L, Levtchenko E et al. The potential of RNA-based therapy for kidney diseases. Pediatr Nephrol 2023;38:327–44. 10.1007/s00467-021-05352-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holtkamp S, Kreiter S, Selmi A et al. Modification of antigen-encoding RNA increases stability, translational efficacy, and T-cell stimulatory capacity of dendritic cells. Blood 2006;108:4009–17. 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pelletier J, Sonenberg N. The organizing principles of eukaryotic ribosome recruitment. Annu Rev Biochem 2019;88:307–35. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rohner E, Yang R, Foo KS et al. Unlocking the promise of mRNA therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol 2022;40:1586–600. 10.1038/s41587-022-01491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grier AE, Burleigh S, Sahni J et al. pEVL: a linear plasmid for generating mRNA IVT templates with extended encoded poly(A) sequences. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2016;5:e306. 10.1038/mtna.2016.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kowalski PS, Rudra A, Miao L et al. Delivering the messenger: advances in technologies for therapeutic mRNA delivery. Mol Ther 2019;27:710–28. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Al-Saif M, Khabar KS. UU/UA dinucleotide frequency reduction in coding regions results in increased mRNA stability and protein expression. Mol Ther 2012;20:954–9. 10.1038/mt.2012.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang Z, Ohto U, Shibata T et al. Structural analyses of Toll-like receptor 7 reveal detailed RNA sequence specificity and recognition mechanism of agonistic ligands. Cell Rep 2018;25:3371–81.e5. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Freund I, Eigenbrod T, Helm M et al. RNA modifications modulate activation of innate toll-like receptors. Genes 2019;10:92. 10.3390/genes10020092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Karikó K, Muramatsu H, Ludwig J et al. Generating the optimal mRNA for therapy: HPLC purification eliminates immune activation and improves translation of nucleoside-modified, protein-encoding mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2011;39:e142. 10.1093/nar/gkr695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Granados-Riveron JT, Aquino-Jarquin G. Engineering of the current nucleoside-modified mRNA-LNP vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Biomed Pharmacother 2021;142:111953. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martins R, Queiroz JA, Sousa F. Ribonucleic acid purification. J Chromatogr A 2014;1355:1–14. 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.05.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Weissman D, Pardi N, Muramatsu H et al. HPLC purification of in vitro transcribed long RNA. Methods Mol Biol 2013;969:43–54. 10.1007/978-1-62703-260-5_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baiersdörfer M, Boros G, Muramatsu H et al. A facile method for the removal of dsRNA contaminant from In vitro-transcribed mRNA. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2019;15:26–35. 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Foster JB, Choudhari N, Perazzelli J et al. Purification of mRNA encoding chimeric antigen receptor is critical for generation of a robust T-cell response. Hum Gene Ther 2019;30:168–78. 10.1089/hum.2018.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aviv H, Leder P. Purification of biologically active globin messenger RNA by chromatography on oligothymidylic acid-cellulose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1972;69:1408–12. 10.1073/pnas.69.6.1408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mansour FH, Pestov DG. Separation of long RNA by agarose-formaldehyde gel electrophoresis. Anal Biochem 2013;441:18–20. 10.1016/j.ab.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reichmuth AM, Oberli MA, Jaklenec A et al. mRNA vaccine delivery using lipid nanoparticles. Ther Deliv 2016;7:319–34. 10.4155/tde-2016-0006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sharova LV, Sharov AA, Nedorezov T et al. Database for mRNA half-life of 19 977 genes obtained by DNA microarray analysis of pluripotent and differentiating mouse embryonic stem cells. DNA Res 2009;16:45–58. 10.1093/dnares/dsn030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Van Meirvenne S, Straetman L, Heirman C et al. Efficient genetic modification of murine dendritic cells by electroporation with mRNA. Cancer Gene Ther 2002;9:787–97. 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Guan S, Rosenecker J. Nanotechnologies in delivery of mRNA therapeutics using nonviral vector-based delivery systems. Gene Ther 2017;24:133–43. 10.1038/gt.2017.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wadhwa A, Aljabbari A, Lokras A et al. Opportunities and challenges in the delivery of mRNA-based vaccines. Pharmaceutics 2020;12:102. 10.3390/pharmaceutics12020102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang W, Hagedorn C, Schulz E et al. Viral hybrid-vectors for delivery of autonomous replicons. Curr Gene Ther 2014;14:10–23. 10.2174/1566523213666131223130024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kauffman KJ, Dorkin JR, Yang JH et al. Optimization of lipid nanoparticle formulations for mRNA delivery in vivo with fractional factorial and definitive screening designs. Nano Lett 2015;15:7300–6. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol 2015;33:941–51. 10.1038/nbt.3330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Semple SC, Akinc A, Chen J et al. Rational design of cationic lipids for siRNA delivery. Nat Biotechnol 2010;28:172–6. 10.1038/nbt.1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ball RL, Hajj KA, Vizelman J et al. Lipid nanoparticle formulations for enhanced co-delivery of siRNA and mRNA. Nano Lett 2018;18:3814–22. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b01101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhao W, Zhang C, Li B et al. Lipid polymer hybrid nanomaterials for mRNA delivery. Cell Mol Bioeng 2018;11:397–406. 10.1007/s12195-018-0536-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Harris JM, Chess RB. Effect of pegylation on pharmaceuticals. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2003;2:214–21. 10.1038/nrd1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shi J, Huang MW, Lu ZD et al. Delivery of mRNA for regulating functions of immune cells. J Control Release 2022;345:494–511. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gustafson HH, Holt-Casper D, Grainger DW et al. Nanoparticle uptake: the phagocyte problem. Nano Today 2015;10:487–510. 10.1016/j.nantod.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Magaña IB, Yendluri RB, Adhikari P et al. Suppression of the reticuloendothelial system using λ-carrageenan to prolong the circulation of gold nanoparticles. Ther Deliv 2015;6:777–83. 10.4155/tde.15.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Diagaradjane P, Deorukhkar A, Gelovani JG et al. Gadolinium chloride augments tumor-specific imaging of targeted quantum dots in vivo. ACS Nano 2010;4:4131–41. 10.1021/nn901919w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nikitin MP, Zelepukin IV, Shipunova VO et al. Enhancement of the blood-circulation time and performance of nanomedicines via the forced clearance of erythrocytes. Nat Biomed Eng 2020;4:717–31. 10.1038/s41551-020-0581-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mirkasymov AB, Zelepukin IV, Nikitin PI et al. In vivo blockade of mononuclear phagocyte system with solid nanoparticles: efficiency and affecting factors. J Controlled Release 2021;330:111–8. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang H, Alarcón CN, Liu B et al. Genetically engineered and enucleated human mesenchymal stromal cells for the targeted delivery of therapeutics to diseased tissue. Nat Biomed Eng 2022;6:882–97. 10.1038/s41551-021-00815-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ye B, Zhao B, Wang K et al. Neutrophils mediated multistage nanoparticle delivery for prompting tumor photothermal therapy. J Nanobiotechnol 2020;18:138. 10.1186/s12951-020-00682-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020;367:eaau6977. 10.1126/science.aau6977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gupta D, Zickler AM, El Andaloussi S. Dosing extracellular vesicles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021;178:113961. 10.1016/j.addr.2021.113961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wang H, Zang J, Zhao Z et al. The advances of neutrophil-derived effective drug delivery systems: a key review of managing tumors and inflammation. Int J Nanaomedicine 2021;16:7663–81. 10.2147/IJN.S328705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vader P, Mol EA, Pasterkamp G et al. Extracellular vesicles for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2016;106:148–56. 10.1016/j.addr.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rubin JD, Barry MA. Improving molecular therapy in the kidney. Mol Diagn Ther 2020;24:375–96. 10.1007/s40291-020-00467-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Davis L, Park F. Gene therapy research for kidney diseases. Physiol Genomics 2019;51:449–61. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00052.2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Morishita Y, Yoshizawa H, Watanabe M et al. siRNAs targeted to Smad4 prevent renal fibrosis in vivo. Sci Rep 2014;4:6424. 10.1038/srep06424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hamar P, Song E, Kökény G et al. Small interfering RNA targeting Fas protects mice against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:14883–8. 10.1073/pnas.0406421101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Takabatake Y, Isaka Y, Imai E. In vivo transfer of small interfering RNA or small hairpin RNA targeting glomeruli. Methods Mol Biol 2009;466:251–63. 10.1007/978-1-59745-352-3_18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Prijic S, Sersa G. Magnetic nanoparticles as targeted delivery systems in oncology. Radiol Oncol 2011;45:1–16. 10.2478/v10019-011-0001-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yavlovich A, Smith B, Gupta K et al. Light-sensitive lipid-based nanoparticles for drug delivery: design principles and future considerations for biological applications. Mol Membr Biol 2010;27:364–81. 10.3109/09687688.2010.507788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhao D, Yang G, Liu Q et al. A photo-triggerable aptamer nanoswitch for spatiotemporal controllable siRNA delivery. Nanoscale 2020;12:10939–43. 10.1039/D0NR00301H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cools N, Van Camp K, Van Tendeloo V et al. mRNA electroporation as a tool for immunomonitoring. Methods Mol Biol 2013;969:293–303. 10.1007/978-1-62703-260-5_18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mukai H, Kawakami S, Takahashi H et al. Key physiological phenomena governing transgene expression based on tissue pressure-mediated transfection in mice. Biol Pharm Bull 2010;33:1627–32. 10.1248/bpb.33.1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mukai H, Kawakami S, Hashida M. Renal press-mediated transfection method for plasmid DNA and siRNA to the kidney. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008;372:383–7. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Woodard LE, Cheng J, Welch RC et al. Kidney-specific transposon-mediated gene transfer in vivo. Sci Rep 2017;7:44904. 10.1038/srep44904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Oyama N, Kawaguchi M, Itaka K et al. Efficient messenger RNA delivery to the kidney using renal pelvis injection in mice. Pharmaceutics 2021;13:1810. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13111810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Pollinger K, Hennig R, Breunig M et al. Kidney podocytes as specific targets for cyclo(RGDfC)-modified nanoparticles. Small 2012;8:3368–75. 10.1002/smll.201200733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Oroojalian F, Rezayan AH, Shier WT et al. Megalin-targeted enhanced transfection efficiency in cultured human HK-2 renal tubular proximal cells using aminoglycoside-carboxyalkyl-polyethylenimine-containing nanoplexes. Int J Pharm 2017;523:102–20. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Almeida B, Nag OK, Rogers KE et al. Recent progress in bioconjugation strategies for liposome-mediated drug delivery. Molecules 2020;25:5672. 10.3390/molecules25235672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kedmi R, Veiga N, Ramishetti S et al. A modular platform for targeted RNAi therapeutics. Nat Nanotechnol 2018;13:214–9. 10.1038/s41565-017-0043-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Richards DA, Maruani A, Chudasama V. Antibody fragments as nanoparticle targeting ligands: a step in the right direction. Chem Sci 2017;8:63–77. 10.1039/C6SC02403C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Okamoto A, Asai T, Kato H et al. Antibody-modified lipid nanoparticles for selective delivery of siRNA to tumors expressing membrane-anchored form of HB-EGF. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014;449:460–5. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.05.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Su CT, See DHW, Huang JW. Lipid-based nanocarriers in renal RNA therapy. Biomedicines 2022;10:283. 10.3390/biomedicines10020283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mu Q, Annapragada A, Srivastava M et al. Conjugate-SELEX: a high-throughput screening of thioaptamer-liposomal nanoparticle conjugates for targeted intracellular delivery of anticancer drugs. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2016;5:e382. 10.1038/mtna.2016.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zhu X, Yin L, Theisen M et al. Systemic mRNA therapy for the treatment of Fabry disease: preclinical studies in wild-type mice, Fabry mouse model, and wild-type non-human primates. Am Hum Genet 2019;104:625–37. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Yuasa T, Takenaka T, Higuchi K et al. Fabry disease. J Echocardiogr 2017;15:151–7. 10.1007/s12574-017-0340-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ivanova EA, De Leo MG, Van Den Heuvel L et al. Endo-lysosomal dysfunction in human proximal tubular epithelial cells deficient for lysosomal cystine transporter cystinosin. PLoS One 2015;10:e0120998. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ivanova EA, Arcolino FO, Elmonem MA et al. Cystinosin deficiency causes podocyte damage and loss associated with increased cell motility. Kidney Int 2016;89:1037–48. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Bondue T, Berlingerio SP, van den Heuvel L et al. The Zebrafish Embryo as a Model Organism for Testing mRNA-Based Therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:11224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. An D, Schneller JL, Frassetto A et al. Systemic messenger RNA therapy as a treatment for methylmalonic acidemia. Cell Rep 2017;21:3548–58. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Desai AS, Webb DJ, Taubel J et al. Zilebesiran, an RNA interference therapeutic agent for hypertension. N Engl J Med 2023;389:228–38. 10.1056/NEJMoa2208391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Porter FW et al. mRNA vaccines—a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018;17:261–79. 10.1038/nrd.2017.243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Rittig SM, Haentschel M, Weimer KJ et al. Long-term survival correlates with immunological responses in renal cell carcinoma patients treated with mRNA-based immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2016;5:e1108511. 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1108511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Rittig SM, Haentschel M, Weimer KJ et al. Intradermal vaccinations with RNA coding for TAA generate CD8+ and CD4+ immune responses and induce clinical benefit in vaccinated patients. Mol Ther 2011;19:990–9. 10.1038/mt.2010.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Xu H, Zheng X, Zhang S et al. Tumor antigens and immune subtypes guided mRNA vaccine development for kidney renal clear cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer 2021;20:159. 10.1186/s12943-021-01465-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Calderhead DM, DeBenedette MA, Ketteringham H et al. Cytokine maturation followed by CD40L mRNA electroporation results in a clinically relevant dendritic cell product capable of inducing a potent proinflammatory CTL response. J Immunother 2008;31:731–41. 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318183db02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. DeBenedette MA, Calderhead DM, Tcherepanova IY et al. Potency of mature CD40L RNA electroporated dendritic cells correlates with IL-12 secretion by tracking multifunctional CD8(+)/CD28(+) cytotoxic T-cell responses in vitro. J Immunother 2011;34:45–57. 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181fb651a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Amin A, Dudek AZ, Logan TF et al. Survival with AGS-003, an autologous dendritic cell-based immunotherapy, in combination with sunitinib in unfavorable risk patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC): phase 2 study results. J Immunother Cancer 2015;3:14. 10.1186/s40425-015-0055-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Czerlau C, Bocchi F, Saganas C et al. Acute interstitial nephritis after messenger RNA-based vaccination. Clin Kidney J 2022;15:174–6. 10.1093/ckj/sfab180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Anderegg MA, Liu M, Saganas C et al. De novo vasculitis after mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccination. Kidney Int 2021;100:474–6. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There were no data generated or analysed during the current review.