Abstract

The stem, consisting of nodes and internodes, is the shoot axis, which supports aboveground organs and connects them to roots. In contrast to other organs, developmental processes of the stem remain elusive, especially those initiating nodes and internodes. By introducing an intron into the Cre recombinase gene, we established a heat shock–inducible clonal analysis system in a single binary vector and applied it to the stem in the flag leaf phytomer of rice (Oryza sativa). With detailed characterizations of stem structure and development, we show that cell fate acquisition for each domain of the stem occurs stepwise. Cell fate for a single phytomer was established in the shoot apical meristem (SAM) by one plastochron before leaf initiation. Cells destined for the foot (nonelongating domain at the stem base) also started emerging before leaf initiation. Cell fate acquisition for the node began just before leaf initiation at the flank of the SAM, separating cell lineages for leaves and stems. Subsequently, cell fates for the axillary bud were established in early leaf primordia. Finally, cells committed to the internode emerged from, at most, a few cell tiers of the 12- to 25-cell stage stem epidermis. Thus, internode cell fate is established last during stem development. This study provides the groundwork to unveil underlying molecular mechanisms in stem development and a valuable tool for clonal analysis, which can be applied to various species.

A heat shock–inducible clonal analysis system for rice revealed the temporal order of cell fate establishment of stem organs in the flag leaf phytomer.

IN A NUTSHELL.

Background: The stem, which consists of nodes and internodes, is an axis of the shoot that physically supports lateral organs such as leaves and flowers and enables water transport and solute exchange. In contrast to other organs such as leaves, roots, and flowers, stem development remains poorly understood. In seed plants, the stem is produced from the shoot apical meristem as a part of the developmental unit called the phytomer, which comprises a leaf, a stem, and an axillary bud.

Question: In what temporal order is cell fate established for each organ in a phytomer? To address this question, we developed a heat shock–inducible clonal analysis system in rice (Oryza sativa). By introducing clonal sectors at various time points during flag leaf phytomer development, we examined whether the fate of a given cell is determined for a certain organ.

Findings: We found that cell fate establishment occurs stepwise for each organ. First, phytomer founder cells are determined before leaf initiation from the shoot apical meristem. Next, the fate of the node is determined in the meristem flank, splitting cell lineages destined for the leaf and the stem. Axillary bud cell fate is established shortly after leaf initiation. Finally, the cell population destined for internodes emerges from, at most, a few cell tiers in the stem. Therefore, the internode develops last in the phytomer.

Next steps: The molecular mechanisms governing early stem development are largely unknown. We demonstrated that there are distinct steps in phytomer development, and thus, the molecular features (e.g. gene expression) that characterize each step can now be determined experimentally. Developmental mutants with altered plant height can also provide insights into stem development.

Introduction

The clonal analysis gives insights into cell lineages and cell fate acquisition during the development of multicellular organisms. In principle, cells are genetically labeled at a certain point of development with a cell-autonomous marker(s) for visualization, and the extent to which the resulting clonal sectors continue among tissues or organs is investigated. Although a detailed description of the tissue of interest is a prerequisite for interpreting data in clonal analysis, this approach provides critical information in understanding the dynamic processes of morphogenesis, such as cell proliferation, the timing of cell fate establishment, and estimation of location and number of initial cells, all of which are not accessible in histological observation (Poethig 1987).

Clonal analyses have been conducted using several different techniques. Seminal works in Datura used colchicine to induce periclinal chimera of polyploids, which can be identified histologically/cytologically in tissue sections (Satina et al. 1940; Satina and Blakeslee 1941). These studies demonstrated the presence of 3 clonally related cell layers (L1, L2, and L3) in the shoot apical meristem (SAM) and their contributions to leaf and flower development (Satina et al. 1940; Satina and Blakeslee 1941). Subsequently, the number of initial cells was estimated to be 1 to 3 in shoots and 3 in roots (Brumfield 1943; Stewart and Dermen 1970). Ionizing radiation, such as X-ray or gamma ray, is the most used method to induce sectors. This method is quite effective when combined with heterozygous recessive mutations affecting chlorophyll or anthocyanin biosynthesis because the deletion of the dominant/functional allele results in the expression of recessive sectors that can be visually examined. Alternatively, pigmentation genes or reporter genes with DNA transposon insertions in their coding regions are also useful tools in clonal analyses (e.g. Dawe and Freeling 1990; Scheres et al. 1994). Upon transposon excision, these genes revert to functional ones and can be traced as colored sectors.

As knowledge in plant histology and development accumulated, a number of clonal analyses were conducted in various species. In shoot meristems, for example, numbers and locations of cells in the embryonic shoot meristem contributing to adult organs have been estimated in maize (Zea mays) (Steffensen 1968; Johri and Coe 1983; Poethig et al. 1986; McDaniel and Poethig 1988), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) (Poethig and Sussex 1985a, b), sunflower (Helianthus annuus) (Jegla and Sussex 1989), and Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) (Furner and Pumfrey 1992; Irish and Sussex 1992). Similar efforts were made in roots (Brumfield 1943; Scheres et al. 1994). Additionally, clonal analyses also revealed that male gametes in anthers originate from the subepidermal L2 layer of shoot meristems (Satina and Blakeslee 1941; Dawe and Freeling 1990). Recently, a heat shock–inducible clonal analysis in Arabidopsis roots determined the origin of vascular cambium stem cells and revealed the function of neighboring xylem cells as an organizer for the cambium (Smetana et al. 2019). Thus, clonal analysis is a powerful method to address important questions in plant development.

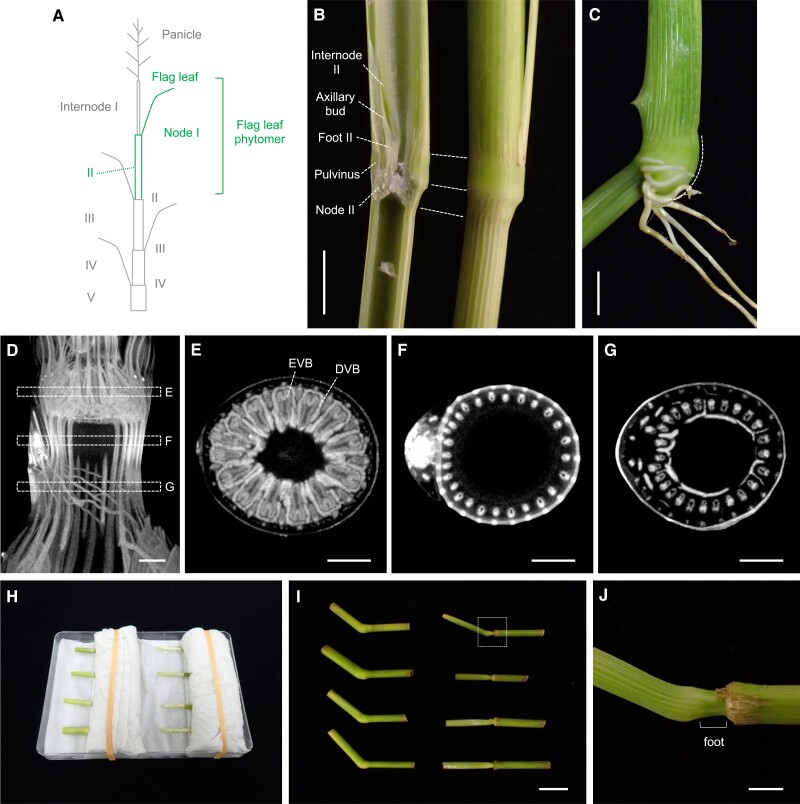

The stem is one of the major organs in vascular plants, which supports aboveground organs and connects the entire body through vascular networks. The stem in seed plants consists of reiterations of nodes and internodes. The node is an attachment point of a leaf to the stem in which the longitudinal growth is quite limited, whereas the internode is a domain of the stem that greatly elongates to lift leaves for light capture (Fig. 1, A and B). The extent of stem elongation determines plant height. Therefore, the stem has been an important target in crop breeding, as exemplified by dwarf mutations utilized in the Green Revolution in the 1960s (Ferrero-Serrano et al. 2019). Despite its importance, however, stem development remains poorly studied. This is contrasting to other major organs such as roots, leaves, and flowers in which detailed regulatory mechanisms have been extensively studied and is possibly due to a lack of clear landmarks specific to each part of the stem, at least externally, in many species (Serrano-Mislata and Sablowski 2018).

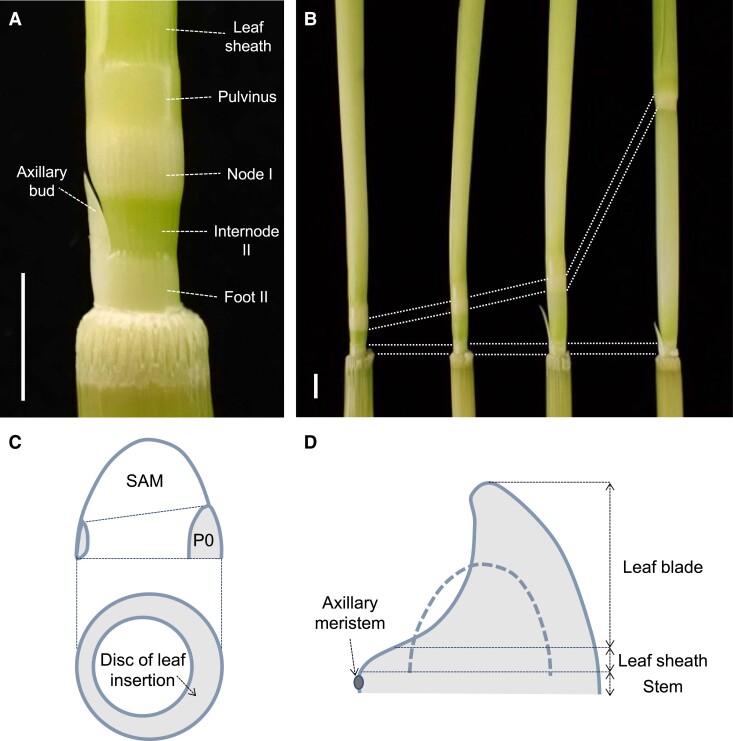

Figure 1.

Illustration of the rice stem structure and a phytomer unit. A) An immature stem of the flag leaf phytomer, consisting of Node I, Internode II, and Foot II. B) Stem samples at various stages of elongation. Note that only internodes elongate significantly. C) A disc of leaf insertion (gray) from which a phytomer unit will form. This region corresponds to the P0 region where the initial downregulation of KNOX genes occurs. D) The leaf primordium that had just encircled the SAM to illustrate a phytomer unit, which consists of a leaf blade at the top, a leaf sheath, an axillary bud, and a stem at the bottom. Scale bars are 5 mm.

The earliest event in stem development is the recruitment of leaf founder cells from the SAM (Fig. 1C). Class I knotted1-like homeobox genes, which maintain an undifferentiated state of the SAM, are downregulated in the P0 region (Jackson et al. 1994). This region corresponds to the disc of leaf insertion, which gives rise to a phytomer unit consisting of a leaf at the top, a node, an internode, and an axillary bud at the bottom (Fig. 1, C and D) (Sharman 1942). Based on histological observations, the upper and lower halves of the disc of insertion were suggested to develop into the leaf and the internode, respectively (Sharman 1942).

Studies of clonal sectors induced in maize dry embryos or young seedlings showed that many sectors found in internodes started at the ear and extended into the leaf above (Johri and Coe 1983; McDaniel and Poethig 1988). Therefore, these organs often share a common cell lineage in early development, supporting the notion of a phytomer unit in grasses (Johri and Coe 1983; McDaniel and Poethig 1988). It was shown that sectors induced at one plastochron before leaf initiation were confined to a single phytomer but not to individual organs (Poethig and Szymkowiak 1995). Another study also in maize suggested that internodes remain a single or a few tiers of L1 cells after several plastochrons from their initiation (Johri and Coe 1996). Thus, the cell fate for a single phytomer has already been established in the SAM just prior to the leaf initiation, but those for individual organs are likely to be specified later. It is still unknown, however, when and in what order the cell fates for individual organs, especially for the node and the internode, are established.

To address this question, a detailed analysis of clonal sectors induced at various time points of a certain phytomer development is important. In rice (Oryza sativa), the node and internode pattern is conspicuous due to extensive internode elongation after the reproductive transition (Fig. 1, A and B). This transition is tightly controlled by the critical day length (Itoh et al. 2010). Therefore, the flag leaf and accompanying stem with extensive elongation can be artificially induced in short-day (SD) conditions. Thus, rice can be a good model for studying stem development, and we aimed to establish a clonal analysis system in rice. The clonal analysis for vascular cambium in Arabidopsis mentioned above utilized a heat-inducible promoter and the cyclic recombinase (Cre) from the P1 bacteriophage to activate a β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter (Smetana et al. 2019). In this study, we adopted this system with several modifications for rice and established a faithful induction of clonal sectors upon heat shock treatments. Using this system, we investigated the temporal order of cell fate establishment in the flag leaf phytomer in rice.

Results

Development of a clonal analysis system for rice in a single binary vector

The system of heat shock–inducible clonal analysis, originally developed in Arabidopsis, consisted of 2 binary vectors; one containing a heat shock–inducible promoter and the gene encoding Cre recombinase fused to cyclin B1;1 (CYCB1;1) destruction box (dBox) (hereafter called pHS_Cre), and another vector possessing the 35S promoter, a roadblock (loxP-tpCRT1-loxP), and the GUS gene (p35S_lox_GUS) (Smetana et al. 2019). The presence of dBox in the former vector results in the proteolysis of Cre proteins at the M phase in the cell cycle, avoiding a carryover of the protein. Upon heat shock treatments, the Cre recombinase removes the roadblock by recombining 2 loxP sites and allows the expression of GUS reporter. Because these recombination events occur by chance, the GUS reporter is activated in certain cells randomly, and such cells will generate clonal GUS-positive sectors.

To save time and effort due to 2 rounds of transformation, we aimed to combine the components into a single binary vector (Fig. 2, A and B). It will be significant, especially in crop species with longer life cycles. Besides, we replaced the 35S promoter with the maize ubiquitin (UBQ) promoter because we previously found that the 35S promoter is often silenced, and the UBQ promoter shows much more stable activity in rice (Tsuda et al. 2022). We also inserted a GFP coding sequence at the C terminus of GUS to allow nondestructive monitoring of spontaneous reporter activation.

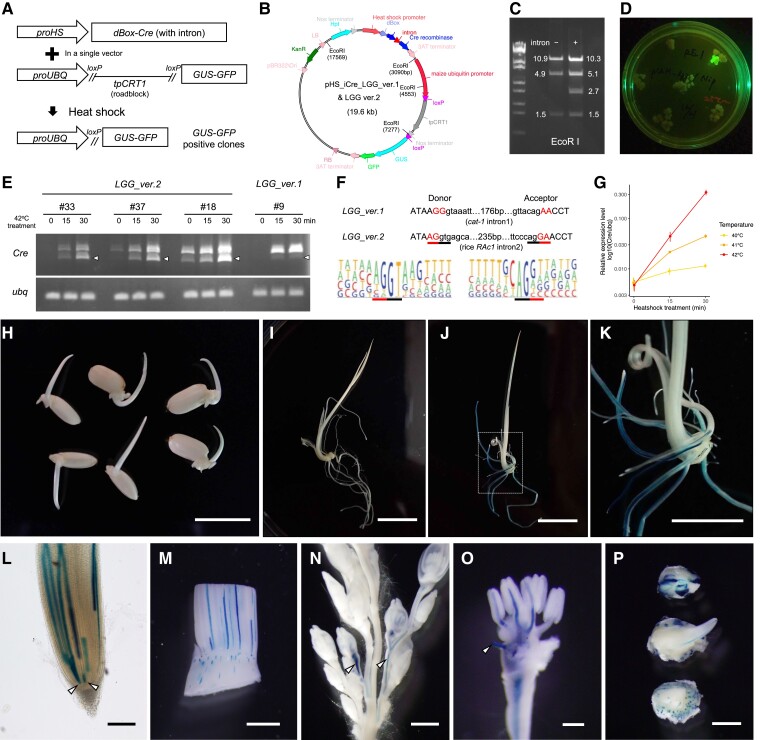

Figure 2.

Development of a clonal analysis system in rice. A) A schematic representation of this system. B) A map of the components equipped in the vectors. EcoRI sites are indicated inside the circle. C) EcoRI restriction digestion fragments of the plasmid with or without the cat-1 intron. Note that the fragment at 2.7 kb corresponding to the tpCRT1 roadblock is missing in the absence of the intron. D) A spontaneous GUS-GFP reporter activation monitored by GFP. This example is from a single case observed in LGG_ver.1. E) RT-PCR for intron-Cre genes. Arrowheads indicate the spliced form. Rice ubq was used as an internal control. F) Comparison of the flanking sequences of the intron. DNA sequences of the first and second versions were indicated above the pictograms, showing consensus sequences of the splicing donor and acceptor sites in the rice genome. Black and red underbars represent less variable dinucleotides in the intron and flanking exons, respectively. Pictograms are from Campbell et al. 2006. G) RT-qPCR for the Cre during heat shock treatments in LGG_ver.2 #33. Error bars are Sds of 3 biological and 2 technical replicates. H) Germinating seedlings at 3 DAG without induction. Note that there is no GUS staining. Two individuals of LGG_ver.2 #33, #37, and #18 (from left to right) were stained for GUS. I) A germinating seedling of LGG_ver.2 #33 at 6 DAG without induction. There is no GUS staining. J and K) A germinating seedling of LGG_ver.2 #33 at 6 DAG with induction at 42 °C for 30 min. A dashed box in J) indicates the region magnified in K). L) A root tip with multiple GUS sectors. Arrowheads indicate putative GUS sectors induced in stem cells. M) GUS sectors induced in the shoot apex. Longitudinal cell files are conspicuous in the leaf sheath, whereas sectors induced in the nonelongating vegetative stem are confined to small regions. N) Two inflorescence sectors (arrowheads) induced at the reproductive transition (+5 SD). O) A sector in the spikelet, showing that 3 anthers share a common vascular cell lineage. An arrowhead indicates a vascular bundle entered into the lemma (removed). P) Embryonic sectors induced during development and stained at 2 DAG. Scale bars are 5 mm in H) and K), 1 cm in I) and J), 200 µm in L) and O), and 1 mm in M), N), and P).

Initially, we tried to transfer this proUBQ-loxP-tpCRT1-loxP-GUS-GFP fragment into the Cre-containing binary vector, but it was unsuccessful. When we digested the resultant plasmid, the band pattern indicated that the plasmid lacked the tpCRT1 roadblock (Fig. 2C). This is possibly due to the misexpression of Cre recombinase in Escherichia coli and unwanted loxP recombination. Therefore, we inserted the first intron of the castor bean (Ricinus communis) catalase gene catalase-1 (cat-1) into the Cre coding region. This intron is widely used in the intron-GUS reporter gene in binary vectors (Tanaka et al. 1990). As we expected, the resultant plasmid pHS_iCre_LGG_ver.1 (LGG stands for lox, GUS, and GFP) showed a predicted band pattern after restriction digestion, indicating that the introduction of the intron stabilized the plasmid structure (Fig. 2C).

The initial version of the intron-Cre gene had a low splicing efficiency

We introduced pHS_iCre_LGG_ver.1 into rice calli (hereafter we call the transgenic plants LGG_ver.1) and monitored spontaneous reporter activation by observing GFP fluorescence (Fig. 2D). Spontaneous activation in LGG_ver.1 was rare (only 1 in 34 independent transgenic T0 calli). Next, we regenerated transgenic shoots from these calli and tested the induction rate of GUS sectors. Because it has been reported that a heat shock treatment at 42 °C induces the expression of heat shock protein genes in rice (Hu et al. 2009; Zou et al. 2009), we treated LGG_ver.1 regenerated plants at this temperature for 30 min. Among 15 independent transgenic T0 lines that we examined, only 9 sectors in 5 lines were found. Thus, even in the lines capable of induction, the induction rate was very low: 1 or 2 GUS sectors per plant. To determine a possible cause of this low induction rate, we checked the Cre gene expression by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR). We found that the spliced form of the Cre gene product was very faint, and the majority was in an unspliced form (Fig. 2E). Thus, LGG_ver.1 had a very low induction rate, possibly due to inefficient splicing of the intron introduced into the Cre gene.

Adjusting the intron structure improved the splicing efficiency and sector induction rates

To improve the splicing efficiency, we compared the sequences around the splicing donor and acceptor sites of the inserted intron with those of the consensus in the rice genome (Fig. 2F; Campbell et al. 2006). Although the dinucleotides at the donor (GT) and acceptor (AG) sites were the same as the consensus, outside sequences in flanking exons differed (red underbars in Fig. 2F). The upstream exons adjacent to the donor site in the consensus frequently end with a dinucleotide “AG” in the rice genome, whereas our case had “GG.” In addition, the downstream exons in the consensus frequently start with “G,” but our case did with “A.” This comparison suggested that the sequences around the intron insertion site were not optimal for efficient splicing in rice. It was also possible that the internal sequence of this cat-1 intron was not suitable for efficient splicing in this specific case.

Based on these considerations, we shifted the intron insertion site by 1 bp to the 5′ side to match the flanking exon sequences with those of consensus in the rice genome (Fig. 2F). We also replaced the intron of cat-1 gene with that of the rice actin gene, RAc1, which is highly and constitutively expressed (McElroy et al. 1990). We named this second version pHS_iCre_LGG_ver.2 and introduced it into rice calli. The frequency of the spontaneous reporter activation was similarly low as the first version (2 in 46 independent transgenic T0 calli). Importantly, among the 30 T0 lines, which were successfully regenerated, 27 showed the induction of multiple GUS-positive sectors after the heat shock treatment. Thus, the adjustment in the intron structure enabled a successful induction of GUS sectors upon heat shock treatments.

Testing the induction conditions for Cre gene expression and GUS sectors

To test the performance of this system, we selected 3 independent lines and examined the induction of the Cre gene in response to varying degrees of heat shock treatments. RT-PCR showed that the spliced Cre transcript in LGG_ver.2 was induced upon heat shock, although we still detected a substantial amount of the unspliced form (Fig. 2E). In line #33, the Cre transcript was undetectable before induction, and the induction level was likely to be the lowest among the 3. Upon heat shock treatments, the transcript level increased in the first 15 min, and the level further increased with longer incubation and/or at higher temperatures (Fig. 2, E and G). Similar trends were found in the other 2 lines (#37 and #18), although they had leaky and higher expression levels (Fig. 2E).

Next, we examined the efficiency of sector induction under various conditions (Table 1). We treated germinating seedlings 3 d after germination (DAG) and stained GUS sectors at 6 DAG. We counted the numbers of seedlings and roots (in both seminal and crown roots) with GUS sectors to evaluate the induction frequency. Importantly, without induction, germinating seedlings of these 3 lines at T2 generation showed no GUS staining, indicating that this system was kept uninduced through 2 rounds of generations under greenhouse conditions (Fig. 2, H and I andTable 1). Incubation at 40 oC for 15 min did not induce GUS sectors. A small number of sectors was first observed after the treatment at 40 °C for 30 min (15.4% of total plants and 3.7% of total roots, Table 1).

Table 1.

GUS-sector induction rate in germinating seedlings

| Line | Heat shock treatments | Number of plants with sectors | Total plants | Plants with sectors/total (%) | Number of roots with sectors | Total roots | Roots with sectors/total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGG_ver.2 #33 | Untreated | 0 | 14 | 0.0 | 0 | 73 | 0.0 |

| 40 °C 15 min | 0 | 12 | 0.0 | 0 | 58 | 0.0 | |

| 40 °C 30 min | 2 | 13 | 15.4 | 2 | 54 | 3.7 | |

| 41 °C 15 min | 7 | 13 | 53.8 | 14 | 61 | 23.0 | |

| 41 °C 30 min | 10 | 13 | 76.9 | 21 | 59 | 35.6 | |

| 42 °C 15 min | 9 | 12 | 75.0 | 29 | 60 | 48.3 | |

| 42 °C 30 min | 14 | 14 | 100.0 | 61 | 77 | 79.2 | |

| LGG_ver.2 #37 | Untreated | 0 | 7 | 0.0 | 0 | 42 | 0.0 |

| 42 °C 15 min | 4 | 7 | 57.1 | 8 | 34 | 23.5 | |

| 42 °C 30 min | 7 | 7 | 100.0 | 41 | 48 | 85.4 | |

| LGG_ver.2 #18 | Untreated | 0 | 5 | 0.0 | 0 | 29 | 0.0 |

| 42 °C 15 min | 5 | 5 | 100.0 | 23 | 25 | 92.0 | |

| 42 °C 30 min | 5 | 5 | 100.0 | 27 | 28 | 96.4 | |

| LGG_ver.1 #9 | Untreated | 0 | 9 | 0.0 | 0 | 53 | 0.0 |

| 42 °C 15 min | 1 | 8 | 12.5 | 1 | 45 | 2.2 | |

| 42 °C 30 min | 2 | 8 | 25.0 | 5 | 50 | 10.0 |

The induction rate substantially increased at 41 °C; nearly half of the plants and a quarter of the roots generated GUS sectors after 15 min, and these rates were further increased after 30 min. At 42 °C, GUS sectors were observed in 75% of plants and 50% of roots after 15 min, and all individuals and 79.2% of total roots had at least one sector after 30 min (Fig. 2, J and K and Table 1). In line #18, which showed the highest Cre expression level, the induction rate was even higher (Table 1). Thus, the Cre expression levels and GUS-sector induction rates associated. In contrast, the induction rate was very low in LGG_ver.1, indicating that the improvement of the intron was essential for efficient induction (Table 1).

Sector inducibility in various tissues and organs

Next, we examined whether GUS sectors could be induced in various tissues and organs using LGG_ver.2 #33 at T2 generation. In crown roots, as shown earlier, longitudinal cell files of GUS sectors were often observed (Fig. 2, J and K). By closely examining their root apices, we identified sectors induced in the putative stem cell regions (Fig. 2L). In the vegetative shoots, longitudinal cell files and small patches of GUS sectors were found in the young leaf sheath and stem, respectively (Fig. 2M and Supplemental Table S1). Clonal analyses described in the following sections also showed that GUS sectors could be induced in the SAM during the reproductive transition (Figs. 4 and 5). Furthermore, sectors could also be induced in developing panicles and embryos (Fig. 2, N to P). Thus, these observations demonstrated the utility of this system in studying various tissues and organs in rice.

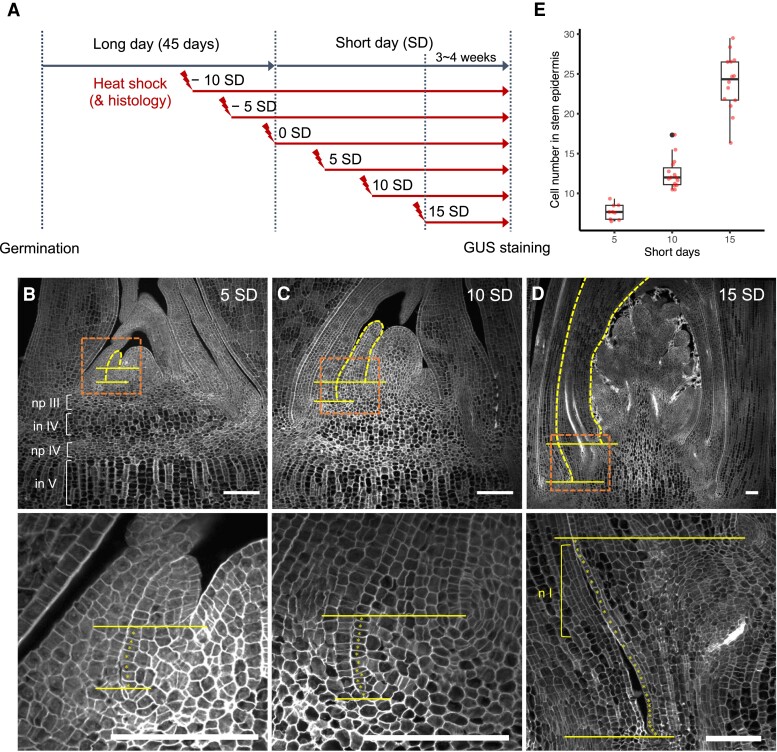

Figure 4.

Histological observation of stem development. A) A schematic representation of inducing the reproductive transition and heat shock treatments during stem development. B to D) Confocal images of the shoot apex sections at +5 SD in B), +10 SD in C), and +15 SD in D). Yellow horizontal lines indicate the bottom of leaf primordia to show putative stem regions where epidermal cell numbers were counted. Yellow dashed lines indicate flag leaf primordia, and orange dashed boxes are approximate regions magnified in the panels below. Magnified images with clear cell boundaries are taken from sections different from those in the top panels. numbers after each domain symbol indicate the order from the top (e.g. np III is nodal plate III). Asterisks in lower panels represent individual cells in the epidermis. Scale bars represent 100 µm. E) Epidermal cell numbers of putative stems counted in tissue sections at +5, +10, and +15 SD. Red points represent each sample. Center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range; black points, outliers. np, nodal plate; n, the putative node region.

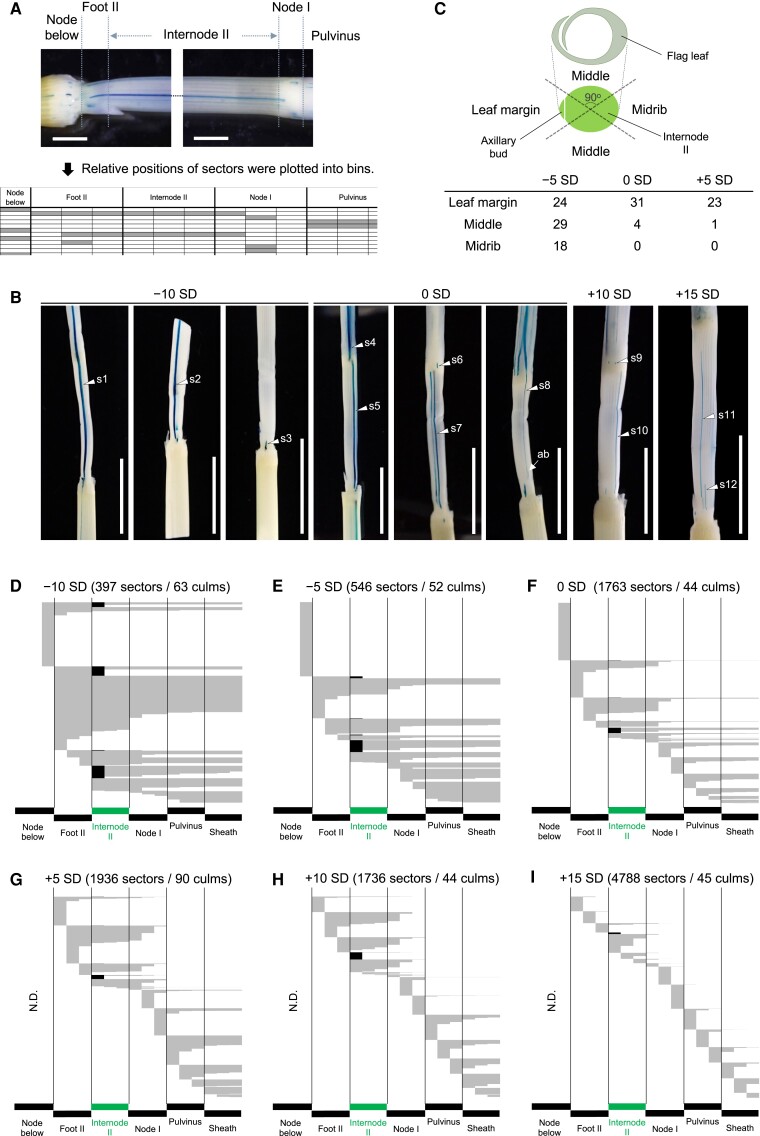

Figure 5.

GUS sectors induced in the stem of the flag leaf phytomer. A) GUS sectors and their assignment to each bin. Note that each domain of the phytomer is divided into 3 bins, and the relative positions of sectors were assigned to these bins. Bars represent 2 mm. B) Representative GUS sectors induced at various time points. Arrowheads indicate key sectors spanning 2 phytomers (s1), the entire flag leaf phytomer (s2), from the node to the sheath (s4), from the foot to the node (s5, s7, and s10), from the axillary bud to the flag leaf margin (s8), or those confined to the foot (s3), to the node (s6, s9), and to the internode (s11, s12). Bars represent 1 cm. C) Sectors spanning the entire flag leaf phytomer or from Node II to the flag leaf sheath were preferentially found on the leaf margin side at 0 and +5 SD. The circumference of the flag leaf phytomer was divided into 4 regions (leaf margin, 2 middle, and midrib regions, 90° for each), and the number of such sectors in each region was counted. D to I) The extent of GUS sectors induced at −10 to +15 SD in D) to I), respectively. Each sector is recorded in each row of the plot. Sectors found in axillary buds are colored black. The numbers of sectors and culms examined are shown at the top. N.D., not determined; ab, an axillary bud;

Characterization of the stem structure in rice

Before conducting clonal analyses, we characterized the structure and development of the stem in the flag leaf phytomer (Figs. 1 and 3). Here, we define the term “domain” as a part of organs with distinct features. For example, the stem consists of 3 domains including the node, internode, and foot (Fig. 1A). Upon reproductive transition, the SAM produces the flag leaf and turns into the inflorescence meristem. The internode, whose elongation is limited during the vegetative phase, starts rapid elongation simultaneously in common rice cultivars. Elongating internodes are numbered from the top; the uppermost internode beneath the panicle is Internode I, and the second one beneath the flag leaf is Internode II (Fig. 3A; Takane and Hoshikawa 1993; Yamaji and Ma 2014). Nodes are also numbered in a similar way; the node at the flag leaf insertion (i.e. beneath the Internode I) is called Node I, and the next node below is Node II. The foot, which is a nonelongating domain at the base of the stem (explained later), was numbered in a similar way in this study; that in between Internode II and Node II was named Foot II (Figs. 1A and 3B). Thus, the flag leaf phytomer consists of the flag leaf, Node I, Internode II, an axillary bud, and Foot II.

Figure 3.

The structure of the rice stem. A) The structure of rice plants and the numbering of each stem. Numbers for nodes and internodes are shown on the right and left, respectively. The flag leaf phytomer focused on in this study is colored green. B) A longitudinal cut of the stem. Note that a central lacuna is continuous from Internode II to Foot II. C) Node-specific structures. The pulvinus, whose bottom part expands (indicated by a dashed line), bends the stem in response to gravity. Crown roots had been initiated from the node. D to G) Micro-CT images representing internal structures of an immature stem of the flag leaf phytomer. D) is a longitudinal section, and E), F), and G) are transverse sections at Node I, Internode II, and Foot II, respectively. Regions shown in E) to G) are indicated with dashed boxes in D). H) An experimental setting to test gravitropism responses in the stem. Stem cuts of Node II were fixed with wet papers and rubber bands. Leaf sheathes and pulvini were removed in the right 4 samples. I) Samples after 2 d. Left 4 samples with intact pulvini bent upright. When the pulvinus was removed (on the right), only one sample slightly bent and the other 3 failed. A dashed box represents the region magnified in J). J) A magnification of the boxed region in I) shows that the bottom of the internode, but not the foot, can show a gravitropism response in rice. DVB, diffusing vascular bundles. Scale bars are 5 mm in B), C), 500 µm in D) to G), 1 cm in I), and 2 mm in J).

Nodes are externally conspicuous in rice and other grasses, possibly because leaves encircle the entire circumference of the stem (Figs. 1A and 3B [Tsuda et al. 2017; Yamaji and Ma 2017]). Internally, node-specific enlarged vascular bundles (EVBs) derived from a leaf at the corresponding node connect to surrounding vascular bundles such as diffusing and transit vascular bundles originating from upper stems through the nodal vascular anastomosis at the bottom of nodes (Fig. 3, D and E and Supplemental Fig. S1) (Yamaji and Ma 2017). This complex vascular network is important for solute exchange because EVBs, and surrounding veins/tissues are the site of action for transporters of various minerals (Yamaji and Ma 2017). Nodes can also exhibit gravitropism owing to the pulvinus located at the base of the leaf sheath and are the site of initiating crown roots (Fig. 3C). In internodes, vascular bundles are narrow and arranged longitudinally, presumably optimized for rapid elongation (Fig. 3, D and F). Internode elongation is important to lift leaves and panicles for light capture and pollination, respectively. Thus, nodes and internodes have distinct but essential roles for survival.

In rice, there is another nonelongating portion beneath internodes, which has not been well characterized yet (Fig. 1, A and B). We recently named this region “foot” (Tanaka et al. 2023). Although the foot shares a central cavity with the above internode at maturity (Fig. 3B), it is a chlorophyll-less and nonelongating tissue in which vascular bundles from the axillary bud connect to those of the stem (Fig. 1, A and B and Fig. 3, D and G). Because the sheath pulvinus surrounds the foot at the leaf base (Fig. 3B), the foot could be a culm pulvinus, which is often present at the bottom of internodes in Panicoideae (Brown et al. 1959). We examined whether the foot can respond to gravity stimulus using stem cuts (Fig. 3, H to J).

When the leaf sheath and the pulvinus were removed, stem cuts often failed to bend. Interestingly, however, one sample without the sheath pulvinus could respond to gravity, and the actual site of additional growth was just above the foot (Fig. 3, I and J). This indicated that the foot is not the primary site acting in gravitropism in rice. The culm pulvinus is likely located at the base of the internode as in Panicoideae, although its ability to respond to gravity is very limited in rice. Thus, it is appropriate to treat the foot as a structure distinct from the internode above.

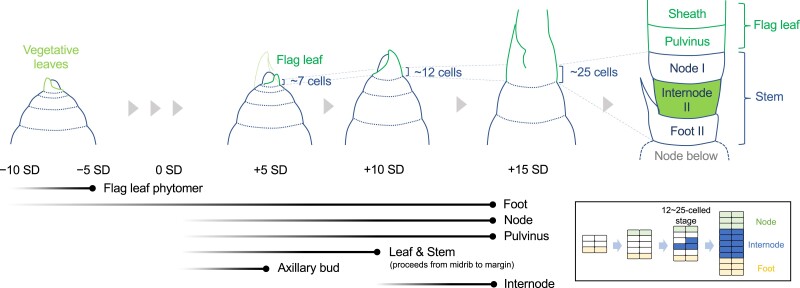

Histological observation of stem development

To characterize stem development in rice, we conducted histological observations during the initiation of the flag leaf phytomer (Fig. 4 and Supplemental Fig. S2). Because this reproductive transition is triggered by shifting day length from long-day (LD) to SD conditions in a photoperiod-sensitive cultivar Nipponbare (Itoh et al. 2010), the formation of this phytomer can be artificially induced (Fig. 4A). After growing plants under LD conditions for 45 d, the day length was shifted to SDs. Because a new leaf is produced every 5 d on average in rice (Itoh et al. 1998), we took tissue samples every 5 d from 10 d before (−10 SD) until 15 d after the transition (+15 SD) from the top 4 shoots (Fig. 4A).

At +5 SD, the flag leaf primordium had just been initiated (a yellow dashed line in Fig. 4B). We counted the number of epidermal cells in the putative stem region below this primordium (between 2 horizontal yellow lines in Fig. 4, B to D). Although it was difficult to determine where the boundary between the leaf and the stem would be, this cell number was useful to refer to the stages of stem development explicitly. At +5 SD, the cell number in the putative stem region was around 7, and there was no sign of node and internode differentiation histologically (Fig. 4, B and E). In the central region of the stem 2 plastochrons older than the flag leaf phytomer, the putative node–internode organization was perceptible at this point (np III and in IV in Fig. 4B), consistent with the previous observation (Kaufman 1959). Nodal plates consist of flattened and less ordered cells, whereas the putative internodes in the center form longitudinal files of elongating cells (Fig. 4B). However, at the periphery of these stems, cells do not show such specialized organizations (Supplemental Fig. S2, A to C). Hence, differentiation along the longitudinal axis remains unclear in the stem periphery.

At +10 SD, the flag leaf primordium became taller, and its margins encircled the inflorescence meristem (Fig. 4C and Supplemental Fig. S2D). The putative stem region beneath the flag leaf had ∼12 epidermal cells at this stage, and there was still no sign of differentiation (Fig. 4, C and E). At +15 SD, when the inflorescence branching had started, the cell number in the putative stem epidermis reached ∼25 cells (Fig. 4, D and E). At this stage, the organization of Node I and Internode II was likely emerging in the peripheral region, although their boundary was still ambiguous and the distinction between Internode II and Foot II was still unclear (Fig. 4D and Supplemental Fig. S2, F and G). This organization was more evident in the stem one phytomer below (Supplemental Fig. S2H, compared with Supplemental Fig. S2, E and G). Subepidermal cells in putative Node II and Foot III are less ordered, whereas those in putative Internode III are arranged in longitudinal files (Supplemental Fig. S2H). Taking together, although the differentiation of putative nodes and internodes becomes distinct in early development in the central region of the stem, that of cells at the periphery, which give rise to the main stem tissue at maturity, remains unclear until later stages.

Induction of GUS sectors during the reproductive transition

To investigate the timing and the order of cell fate establishment in the stem, we applied our clonal analysis system to the stem development of the flag leaf phytomer. Along with the growth scheme of the above-mentioned reproductive transition, we prepared 6 sample groups at intervals of 5 d (Fig. 4A). The heat shock conditions were at 42 °C for 30 or 45 min because treatments of lower temperature or shorter time did not induce enough sectors in the stem (Supplemental Table S2). After the last treatment at +15 SD, we let LGG_ver.2 #33 plants grow for an additional 3 to 4 wk and harvested culms for GUS staining. Each sample group comprised the top 4 or 5 culms from at least 10 individuals. Because the Internode II was much longer than other domains, we plotted the relative positions of GUS sectors into 3 bins for each domain (Fig. 5A). Besides, as samples were cut at Node II or Internode III for the lower end and at the middle of the flag leaf sheath for the upper end, we did not deal with sectors found in these regions except when the continuity of sectors from the neighboring domains was considered.

We examined sectors under a dissecting microscope and selected epidermal and subepidermal sectors that satisfied the following 2 criteria: (i) sectors that were clearly separated from neighbors, and (ii) both the start and the end of sectors were clear. Edges of epidermal sectors were usually clear-cut, whereas those in the subepidermal layer were blurry. Therefore, subepidermal sectors tended to be excluded from the analysis. To avoid including sectors of 2 adjacent cell origins, we excluded sectors that were extraordinarily wide (e.g. twice the width of the most frequent sectors) or when subepidermal sectors were underlying the epidermal ones (Supplemental Fig. S3). When sectors were too crowded to confidently delineate, we excluded such samples (Supplemental Fig. S3E).

Definition of terms and data interpretation in this study

Here, we define 2 terms, “cell fate” and “cell lineage,” that are involved in the interpretation of clonal analyses. “Cell fate” is the final destination of a cell of interest to organs/domains at maturity. “Cell lineage” is generally defined as the developmental history of differentiated tissues or organs. More specifically in clonal analyses, this term is often used to indicate a group of cells descendant to a cell of interest at a certain point of development, which is visualized as a sector. We use the latter definition for “cell lineage” in most cases in this study. “Cell identity” can be generally defined as the differentiated state of the cell, which can only be determined by the expression of molecular markers or detailed cellular structures. Because no such marker is currently available for stem domains, we do not deal with cell identity in this study.

It is generally accepted that a cell lineage is often decoupled into cell populations with distinct fates depending on the position of cells relative to their surroundings in many aspects of plant development (Poethig et al. 1986; McDaniel and Poethig 1988; Steeves and Sussex 1989; Scheres 2001). We explore the developmental stages when the cell fate establishment for each organ/domain starts and completes. If a sector is induced before this stage, the cell proliferates over time during development, and its cell lineage (or a sector) results in spanning multiple organs/domains. If a certain sector was confined to a single organ or domain, we consider that the cell lineage did not proliferate beyond the organ/domain boundaries, and hence, that the fate of the cell of interest had been established at the point of induction. When all sectors were confined to a single organ/domain, we interpret that the founder cells for that organ/domain were fully present at the point of induction.

The earliest events were the establishment of cell fates for the flag leaf phytomer and Foot II

The number of sectors ranged from 397 to 4788, depending on the timing of the heat shock treatment (Fig. 5, B and D to I). Samples induced at later time points tended to have more sectors because the number of cells in the tissues of interest increased as the plant grew. Overall, GUS sectors initially spanned broadly but were gradually confined to narrower regions of the stem (Fig. 5B and Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

The number of sectors extended for multiple TTs

| Stage | Two phytomers | Entire flag phytomer | Four TTs | Three TTs | Two TTs | Single TT | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −10 SD | 25 (8.7) | 94 (32.8) | 32 (11.1) | 32 (11.1) | 65 (22.6) | 39 (13.6) | 287 |

| −5 SD | 0 | 40 (11.8) | 35 (10.3) | 101(29.7) | 79 (23.2) | 85 (25.0) | 340 |

| 0 SD | 0 | 12 (1.0) | 31 (2.5) | 275 (22.0) | 240 (19.2) | 691 (55.3) | 1249 |

| +5 SD | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 267 (13.7) | 424 (21.7) | 1,229 (64.5) | 1952 |

| +10 SD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 154 (8.6) | 357 (19.9) | 1,284 (71.5) | 1795 |

| +15 SD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 (0.3) | 191 (4.0) | 4,546 (95.7) | 4788 |

Numbers in parentheses are percentages by total sectors. Sectors confined in Node II were not considered. TT, tissue type.

Table 3.

Sectors confined in a single TT

| Stage | Foot | Axillary bud | Internode | Node | Pulvinus | Sheath | Single TT sectors | Total sectors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −10 SD | 36 (12.5) | 3 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 39 (13.6) | 287 |

| −5 SD | 68 (20.0) | 5 (1.5) | 0 | 10 (2.9) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 85 (25.0) | 340 |

| 0 SD | 332 (26.6) | 11 (0.9) | 0 | 206 (16.5) | 112 (9.0) | 30 (2.4) | 691 (55.3) | 1249 |

| +5 SD | 487 (24.9) | 31 (1.6) | 0 | 394 (20.2) | 247 (12.7) | 101 (5.2) | 1,260 (64.5) | 1952 |

| +10 SD | 270 (15.0) | 61 (3.4) | 50 (2.8) | 346 (19.3) | 349 (19.4) | 208 (11.6) | 1,284 (71.5) | 1795 |

| +15 SD | 812 (17.0) | 37 (0.8) | 653 (13.6) | 1,081 (22.6) | 1,161 (24.2) | 839 (17.5) | 4,583 (95.7) | 4788 |

Numbers in parentheses are percentages by total sectors. Sectors confined in node II were not considered. TT, tissue type.

In samples treated at −10 SD, most sectors (91.3%) were confined to the flag leaf phytomer (s2 in Fig. 5, B and D and Table 2). Among these, sectors spanning the entire flag leaf phytomer were the most prominent (32.8%), and those across multiple organs were also frequent (Table 2). This indicates that, at 2 plastochrons prior to the flag leaf initiation, the cell fates for this phytomer but not for specific organs had been largely established in the SAM. At substantial frequencies, however, we observed sectors confined to the bottom of Foot II (12.5%, s3 in Fig. 5B, and Table 3), suggesting that Foot II may be the earliest domain whose cell fate starts being determined in the flag leaf phytomer. Occasionally, we also observed sectors that spanned across 2 successive phytomers (8.7%, s1 in Fig. 5B, and Table 2). According to previous studies in maize, these are sectors induced in the SAM above the peripheral zone (McDaniel and Poethig 1988).

In samples treated at −5 SD, sectors that spanned across 2 phytomers disappeared, although 40.9% of the sectors extended into both the flag leaf sheath and the stem (Fig. 5E and Supplemental Table S3). Therefore, the fate of the flag leaf phytomer had been completely established but has yet to be for specific organs. In addition, sectors confined to the bottom of Foot II became more evident (20%, Table 3), consistent with data at −10 SD.

Determination of nodal cell fates split the flag leaf and the subtending stem

In samples treated at 0 SD, sectors that extended for the entire phytomer almost disappeared (1%), and those confined either to the stem or to the flag leaf became evident (88.8%, s4 and s5 in Fig. 5, B and F, Table 2, and Supplemental Table S3). Therefore, cell lineages specifically contributing to the flag leaf or the stem had been largely established at the flank of the SAM or in the P0 region. This divergence of cell lineages for the flag leaf and the stem was accompanied by the frequent emergence of sectors confined in Node I or the pulvinus (25.5%, s6 and s9 in Fig. 5B, and Table 3). These trends became more evident in the samples treated at +5 SD (Fig. 5G and Table 3). Therefore, Node I and the associated leaf sheath pulvinus may be second domains whose cell fates started being established, splitting neighboring cell lineages into the flag leaf and subtending stem.

However, we also observed that a fraction of sectors still spanned both the flag leaf and the stem at around 0 to +5 SD (s8 in Fig. 5B). Grass leaf development is known to proceed from the midrib side toward margins as the primordia encircle the SAM (Sharman 1942), and the leaf sheath margins are formed late (at P3 to P4 in maize [Scanlon and Freeling 1997; Scanlon 2003; Johnston et al. 2015] and P2 in rice [Itoh et al. 2005]). Therefore, we determined the location of large sectors spanning the entire flag leaf phytomer or from Node II to the flag leaf sheath around the circumference to reveal the nature of these sectors (Fig. 5C). Most of them were found on the leaf margin side, and none of them were found on the midrib side at 0 and +5 SD. This biased distribution was not clear at −5 SD (Fig. 5C). Thus, on the midrib side, the cell fates had already diverged for the leaf and stem at 0 SD on the flank of the SAM, whereas this fate determination had not been completed on the marginal side at +5 SD, indicating that cell fate establishment for the flag leaf and the stem proceeds gradually from the midrib side toward the leaf margins.

It is noteworthy that, at 0 SD, sectors confined to the axillary bud and Internode II were rare and absent, respectively; sectors found in axillary buds often extended to Internode II (Supplemental Fig. S4, A and B), and those in the Internode II always spanned either to the Foot II or Node I (s7 in Fig. 5, B and F). These data indicate that cell fates for the axillary bud and Internode II had not been established at 0 SD.

The internode is the last part of the stem whose cell fate was established

In contrast to earlier sample groups, sectors in axillary buds induced at +5 SD hardly extended into Internode II anymore (Fig. 5G and Supplemental Fig. S4, C to E). The size of sectors in axillary buds gradually became smaller in samples treated later. Therefore, founder cells contributing to axillary buds had been fully present by the time the flag leaf primordium was encircling the SAM (Fig. 4B). In contrast, all sectors found in Internode II spanned to neighboring domains (Fig. 5G). Thus, the cell fate establishment for Internode II had yet to be started.

Sectors confined to Internode II were first observed at a low frequency (2.8%) in samples treated at +10 SD (Fig. 5H and Table 3). In the sample group treated at +15 SD, most GUS sectors found in Internode II (88.8%) did not extend into neighboring tissues anymore (s11 and s12 in Fig. 5, B and I, Table 3, and Supplemental Table S3). Therefore, cell fate determination for the internode likely occurred between the 12- and 25-celled stages. Notably, the majority of these sectors in Internode II spanned more than half of the length of Internode II (Fig. 5I), suggesting that the number of cells destined for Internode II was still very few at +15 SD. Thus, the Internode II was the last domain whose cell fate determination began in the flag leaf phytomer.

Discussion

In this study, we established an efficient tool for clonal analysis in rice. Based on the detailed description of the stem development, we applied our tool to reveal the temporal order of cell fate determination in the stem tissues of the flag leaf phytomer. Because our system can be readily applied to any organs in rice examined so far, it will be a powerful tool to widen the knowledge of cell lineage and cell fate determination, which is still very limited in rice. Inserting an intron into the Cre-coding region enabled us to unite the system components into a binary vector, allowing a rapid establishment of experimental lines through a single transformation. Moreover, because the heat shock treatment requires no chemical inducers such as dexamethasone or estradiol, it is harmless to researchers. It can be applied to a wide range of plant species of various sizes.

Spontaneous activation of GUS sectors was rare, and GUS-sector induction strictly required heat shock treatments even with a leaky expression of the Cre gene. The unspliced form of the Cre transcript was still detected in the improved version LGG_ver.2. Therefore, it is possible that this incomplete splicing hindered the accumulation of the mature transcript above a certain threshold and hence might have served as a rate-limiting step for induction. In this scenario, the level of mature Cre transcripts in the leaky lines may be simply under this threshold before the heat shock. Spontaneous inductions of sectors that we observed in calli may be the cases in which the basal expression level of Cre exceeded this level. Although the exact mechanism for this requirement of heat shock is unclear, the insertion of an intron likely resulted in a faithful induction system.

The frequency of GUS-sector induction increased with higher temperatures and longer treatments. In germinating seedlings, efficient induction of GUS sectors was already observed at 41 °C, and upregulation of Cre was observed within 15 min after the treatment. However, in the case of the flag leaf phytomer, the heat shock treatment at 42 °C for 30 min or longer was required for an efficient induction (Supplemental Table S2). This is probably due to the requirement of higher temperatures or a longer time for heat conduction to reach the shoot apices enclosed by adult leaves. Thus, the optimal condition for heat shock depends on how the tissue of interest is exposed. It is important to select the lowest temperature and the shortest duration to avoid undesired side effects such as growth retardation or tissue damage.

In this study, we exclusively focused on the epidermal and subepidermal sectors. However, sectors can also be induced in the internal tissues. For example, we detected sectors in the internal tissues of developing leaves and stems of vegetative shoots. After heat shock treatments, it was important to cut samples to expose the tissue of interest to GUS substrates. Alternatively, sectors may be observed using GFP fused to GUS in this system.

In every sample group, we observed considerable variabilities in the extent to which sectors extended. For example, most sectors induced at −10 SD were confined to the flag leaf phytomer, whereas some spanned to neighboring Node II (Fig. 5D). In axillary buds, although most sectors extended to neighboring organs until +5 SD, those confined to this organ were observed at low frequencies repeatedly (Fig. 5, D to F and Table 3). Even in a single sample, some sectors extended for more numbers of phytomers/organs/domains than their neighboring sectors. According to the studies in maize, there are 2 possible sources of these variances (Poethig et al. 1986; McDaniel and Poethig 1988). First, there must be variances in developmental stages among samples at the point of induction. This is trivial but unavoidable. Second, more importantly, cells at similar positions in a certain organ/domain may contribute differently due to the variance in the frequency and orientation of cell division. Thus, even at similar positions, individual cells can vary in their final lineage sizes or fates, and the sectors confined to a single domain found in earlier samples may reflect the existence of cells that do not actively divide until late development. Besides, the timing of cell fate determination also depends on the organ developmental program. Consistent with the course of leaf development, which proceeds from the midrib side to the leaf sheath margin side, we observed that cell fate determination in the midrib region occurred earlier than that in the leaf marginal region.

The induction of sectors in 2 adjacent cells can be misleading in data interpretation. Sectors induced in 2 horizontally adjacent epidermal cells are expected to be twice wider than average sectors in the same domain at the same stage. We occasionally found such sectors (Supplemental Fig. S3, A and B) and excluded them from the analysis. The frequency of such wide sectors calculated based on the earlier samples (−10 to 0 SD) was ∼1% (Supplemental Fig. S3C). In the case that 2 adjacent cells aligned in a longitudinal direction, such sectors are expected to be longer than average sectors in the corresponding organ/domain at the same stage. However, the variance in the longitudinal direction was inherently large, and we were not able to distinguish sectors of 2 longitudinally adjacent cell origins from other variances, although we expect that longitudinal adjacent sectors would occur at a frequency similar to that of horizontally adjacent sectors (∼1%).

To reduce the chance of including 2 adjacent sectors, we filtered out samples in which the number of sectors in each bin exceeded a certain threshold (Supplemental Fig. S5). We counted the number of sectors in each bin of each sample, and if this number exceeded a threshold in any bin, we excluded such a sample. Because samples treated at later stages tended to have more sectors per bin, they tended to be filtered out and lost the analytical power at lower thresholds. Nevertheless, the overall trend of sector distribution was consistent across different thresholds of filtering, suggesting the presence of sectors of 2 adjacent cell origins does not largely affect data interpretation.

Our experiments showed that the cell fates for distinct parts of the stem are determined stepwise depending on the tissue type (summarized in Fig. 6). Around −10 SD when the leaf primordium 2 plastochrons before the flag leaf is initiating, the cell fate for the flag leaf phytomer is largely but incompletely established in the SAM, and it becomes complete 5 d later. Thus, founder cells for the flag leaf phytomer are fully present at −5 SD. This is consistent with the observation in maize, in which the fate for a single phytomer is established one plastochron before its initiation (Poethig and Szymkowiak 1995). In addition, a fraction of the cell population had already been committed to the bottom part of Foot II, suggesting that the most bottom tiers of cells destined for the flag leaf phytomer in the SAM start establishing their fate first.

Figure 6.

The temporal order of cell fate acquisition in the rice stem. The fate of the flag leaf phytomer is established 1 to 2 plastochrons prior to the leaf initiation. Fates for nonelongating domains such as Foot II, Node I, and the pulvinus start being established earlier than elongating domains. Internode II is the last part of the stem whose cell fate determination starts. It is likely to originate from a very limited number of cells between Node I and Foot II (inset). Black gradient lines at the bottom left show the start (left) and end (right) of cell fate establishment. Stages at which the founder cells are fully present are indicated by dots at the end of black lines. Light green lines, leaf primordia before the flag leaf; green lines, flag leaf primordia; blue lines, stem and axillary buds. Internode II was filled in green. In the inset, cells distained for the node, internode, and foot are filled in green, blue, and yellow, respectively.

At the onset of the reproductive transition (0 SD), cell fates for the nodal tissue, including Node I and the pulvinus, start being established at the flank of the SAM, leading to the divergence of cell lineages for the flag leaf or the stem. This result supports the hypothesis proposed by Sharman (1942), in which the upper and lower halves of the disc of leaf insertion contribute to the leaf and the stem, respectively. In addition, this fate split between the leaf and the stem proceeds from the midrib side toward the leaf sheath margins and becomes complete by +10 SD. Thus, founder cells for the flag leaf and the stem are fully present at +10 SD. At +5 SD, cells committed to the axillary bud are also established. It is not until +10 to +15 SD that the cell fate for Internode II starts being established. The number of epidermal cells in the developing stem at this point ranges from 12 to 25, and the cell fate commitment for Internode II likely occurs in a single to a few tiers of cells. This is consistent with the report in maize, in which internodes remain a single or a few tiers of L1 cells after several plastochrons from their initiation (Johri and Coe 1996). At +15 SD, most sectors were confined to each domain, suggesting that founder cells for each domain are almost fully present. Overall, cell fate commitment for nonelongating tissues starts first and that for the internode takes place at the end.

An intriguing question is how the cell/tissue identities along the longitudinal axis of the stem are determined. Our data suggested that the cell fates for the node and its associated pulvinus are established in the SAM before the initiation of flag leaf primordia, whereas that for the internode is determined in a very limited number of cells much later (inset in Fig. 6). This is in clear contrast to the central region of the stem in which the putative node and internode patterns emerge almost simultaneously. The central regions in the internode and the foot form cavities or lacunae for gas exchange, possibly through programed cell death (Steffens et al. 2011; Fujimoto et al. 2018), whereas this does not occur in the peripheral region. It is possible that distinct regulatory programs govern patterning events in the central and peripheral regions of the stem from the very early stage of development. Studies in deepwater rice have shown the presence of several activators and a repressor of internode elongation, which confer the regulated competency for internode growth depending on water levels, even in the vegetative phase (Hattori et al. 2009; Kuroha et al. 2018; Nagai et al. 2020). In the vegetative stem of common cultivars, internodes may be present but simply cannot elongate due to the repressor (Gomez-Ariza et al. 2019). Alternatively, internode initiation per se may be repressed in this phase. So far, molecular mechanisms involved in these regulations and those that specify the node and internode pattern are entirely unknown. The stepwise establishment of cell fates revealed here will be the foundation to unveil underlying mechanisms in stem development by providing clues regarding the timing of key events in future studies.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The original heat shock–inducible clonal analysis system reported by Smetana et al. (2019) consists of 2 binary vectors: one containing a heat shock–inducible promoter and the gene encoding Cre fused to cyclin B1;1 destruction box (dBox) (called pHS_Cre in this study), and another possessing the 35S promoter, a roadblock (loxP-tpCRT1-loxP) and a β- GUS coding region (p35S_lox_GUS). To combine these components into a single binary vector, we mutated the original KpnI site in pHS_Cre and reintroduced a new KpnI site next to the SacI site by ligating annealed double-stranded oligonucleotides (KT1320-1321, Supplemental Table S4). This vector containing the neighboring SacI and KpnI cloning sites was named pHS_Cre2.

We also modified p35S_lox_GUS to achieve stable expression and nondestructive monitoring of spontaneous reporter activation in rice (O. sativa). To place the loxP-tpCRT1-loxP-GUS under the maize (Z. mays) UBQ promoter, we subcloned a 4.6 kb HindIII fragment containing these elements from p35S_lox_GUS into pPUBn (Tsuda et al. 2022) and named this plasmid pUBQ_lox_GUS. Then, we fused GFP to the C terminus of GUS through seamless cloning (NEBuilder, NEB) using primers KT1101, KT1102, KT1103, and KT1104. We named this plasmid pUBQ_LGG. The first intron sequence from the castor bean (R. communis) catalase-1 (cat-1) gene in the pBGH1 vector (Ito and Kurata 2008) was introduced into pHS_Cre through NEBuilder using primer sets KT1387, KT1388, KT1389, and KT1390. The resultant plasmid was named pHS_iCre.

A 7.4 kb SacI-KpnI fragment containing pUBQ-loxP-tpCRT1-loxP-GUS-GFP from pUBQ_LGG was subcloned into pHS_iCre, and this plasmid was named pHS_iCre_LGG_ver.1.

We replaced the cat-1 intron with the second intron of the rice Actin1 (RAc1) gene through NEBuilder using primers KT1491, KT1492, KT1493, and KT1494 and named the resultant plasmid pHS_iCre2. Finally, the 7.4 kb SacI-KpnI fragment from pUBQ_LGG was subcloned into pHS_iCre2, and this plasmid was named pHS_iCre_LGG_ver.2.

DNA sequences amplified using PCR were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Primers used in the plasmid construction are listed in Supplemental Table S4.

Plant materials, transformation, and growth conditions

Transgenes were introduced into Nipponbare using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation as described previously (Toki et al. 2006). Hygromycin-resistant plants were transferred to soil in black vinyl pots (13.5 cm diameter) until maturity. Transgenic plants at subsequent generations were genotyped for the hygromycin phosphotransferase (hpt) gene using primers KT287 and KT288, and hpt-positive plants were grown in the growth chamber under the LD condition (14-h light at 30 °C and 10-h dark at 25 °C). At 45 DAG, the day-night cycle was shifted to the SD condition (10-h light at 30 °C and 14-h dark at 25 °C). Light intensity was at 350 μmol photons m−2 s−1. The relative humidity was maintained at 70%.

Heat-shock treatments

To test heat-shock conditions, transgenic seedlings at 3 DAG were incubated in a water bath at 40, 41, and 42 °C for 15 and 30 min. After the heat shock, plants were grown for 3 d in the growth chamber until GUS staining.

For sector induction in the Internode II, plants at 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, and 60 DAG (for −10, −5, 0, +5, +10, and +15 SD treatments, respectively) were incubated in a water bath at 41 or 42 °C for 30 or 45 min. To avoid the temporal drop of water temperature at the beginning of the heat shock, up to 3 pots with soil were incubated in 35 L of water at once, and the water temperature was monitored. After the heat shock, plants were cooled down at room temperature for 30 min and grown in the growth chamber for an additional 3 to 4 wk until the lamina joint distance between the flag leaf and a leaf below reached 3 to 5 cm. At this stage, the length of internode II ranged from 1 to 8 cm.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and RT-PCR

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, RT-PCR, and reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) were performed as described previously (Tsuda et al. 2022). Total RNA was extracted from germinating seedlings at 3 DAG. At least 3 plants were pooled in each biological replicate, and 3 biological replicates were performed for each data point. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, and the rice ubiquitin (ubq) gene was used as an internal standard. The primers used in PCR are listed in Supplemental Table S4.

Recording and representation of GUS sectors in the flag leaf phytomer

GUS staining was conducted as described previously (Jefferson et al. 1987; Tsuda et al. 2022). The stained sectors were observed under the dissecting microscope (SZX16, Olympus). We dealt with only epidermal and subepidermal sectors that can be unambiguously traced. To record the approximate positions of sectors, each domain (Foot II, Internode II, Node I, the pulvinus, and the flag leaf sheath) was divided into 3 bins: bottom, middle, and top thirds. The relative position of each sector was recorded in spreadsheets, in which rows and columns correspond to samples and bins, respectively. After rows in this spreadsheet were sorted by the relative position of sectors, data were plotted using the “heatmap” function in base R (Supplemental Data Set 1 and Supplemental Files 1 and 2).

Micro-computed tomography

Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scanning was performed as described previously (Tsuda et al. 2017; Maeno and Tsuda 2018). Rice stem samples (5 mm) were fixed in FAA (formalin:acetic acid: 50% [v/v] ethanol = 5:5:90) overnight. The fixative was replaced with 70% ethanol and stored at 4 °C until observation. Before scanning, samples were soaked in the contrast agent (0.3% [w/v] phosphotungstic acid in 70% [v/v] ethanol) for 18 d and scanned using X-ray micro-CT at a tube voltage peak of 80 kVp and a tube current of 90 µA. Samples were rotated 360° in steps of 0.24°, generating 1,500 projection images of 992 × 992 pixels. The micro-CT data were reconstructed at an isotropic resolution of 5.5 × 5.5 × 5.5 µm3. Three-dimensional tomographic images were obtained using the OsiriX software.

Histological observation

Shoot apices were dissected and fixed in FAA and were embedded in Paraplast Plus (McCormick Scientific) as described previously (Tsuda et al. 2017). Eight micrometer sections were stained using toluidine blue O and observed under light microscopy (Olympus BX50). To count epidermal cells in the developing stem, sections were stained with calcofluor white and imaged under the Fluoview FV300 CLSM system (Olympus) with excitation at 404 nm and detection at 430 to 460 nm.

Accession numbers

Accession numbers for rice genes examined in this study are LOC_Os03g13170 (RAc1) and LOC_Os03g13170 (ubq). The annotation was based on the rice genome annotation project (http://rice.uga.edu/index.shtml).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ari Pekka Mähönen for providing original binary vectors for the clonal analysis in Arabidopsis and Keisuke Nagai for critical reading and comments on the manuscript. We also thank Kae Kato and Ayako Otake for their technical assistance.

Contributor Information

Katsutoshi Tsuda, Plant Cytogenetics Laboratory, Department of Gene Function and Phenomics, National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Shizuoka 411-8540, Japan; Department of Genetics, School of Life Science, Graduate University for Advanced Studies, Mishima, Shizuoka 411-8540, Japan.

Akiteru Maeno, Plant Cytogenetics Laboratory, Department of Gene Function and Phenomics, National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Shizuoka 411-8540, Japan.

Ken-Ichi Nonomura, Plant Cytogenetics Laboratory, Department of Gene Function and Phenomics, National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Shizuoka 411-8540, Japan; Department of Genetics, School of Life Science, Graduate University for Advanced Studies, Mishima, Shizuoka 411-8540, Japan.

Author contributions

K.T. designed this work, conducted experiments, and analyzed data. A.M. performed the micro-CT observation. K.-I.N. supervised the project. K.T. wrote the manuscript with the help of K.-I.N. K.T. revised the manuscript.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Simplified illustrations of vascular networks in the rice stem.

Supplemental Figure S2. Histological observations of stem development during initiation of the flag leaf phytomer.

Supplemental Figure S3. Examples of sectors that were excluded from the analysis.

Supplemental Figure S4. Examples of sectors induced in axillary buds at different stages.

Supplemental Figure S5. Sector distributions at different filtering thresholds.

Supplemental Table S1. GUS sector induction rate in the vegetative shoot apex.

Supplemental Table S2. GUS sector induction rate in the Internode II.

Supplemental Table S3. The details of sectors extended for multiple tissue types (TTs).

Supplemental Table S4. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Data Set 1. A CSV file of sector data.

Supplemental File 1. R scripts for plotting sector data.

Supplemental File 2. R scripts for filtering sector data.

Funding

This work is supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI 18H04845, 20H04891, 22H02319, and 23H04754 to K.T. and 21H04729 to K.-I.N.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- Brown WV, Pratt GA, Mobley HM. Grass morphology and systematics. II. The nodal pulvinus. Southwestern Naturalist. 1959:4(3):126–130. 10.2307/3669020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brumfield RT. Cell-lineage studies in root meristems by means of chromosome rearrangements induced by X-rays. Am J Bot. 1943:30(2):101–110. 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1943.tb14737.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MA, Haas BJ, Hamilton JP, Mount SM, Buell CR. Comprehensive analysis of alternative splicing in rice and comparative analyses with Arabidopsis. BMC Genomics. 2006:7(1):327. 10.1186/1471-2164-7-327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe RK, Freeling M. Clonal analysis of the cell lineages in the male flower of maize. Dev Biol. 1990:142(1):233–245. 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90167-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero-Serrano A, Cantos C, Assmann SM. The role of dwarfing traits in historical and modern agriculture with a focus on rice. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2019:11(11):a034645. 10.1101/cshperspect.a034645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto M, Sazuka T, Oda Y, Kawahigashi H, Wu J, Takanashi H, Ohnishi T, Yoneda JI, Ishimori M, Kajiya-Kanegae H, et al. Transcriptional switch for programmed cell death in pith parenchyma of sorghum stems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018:115(37):E8783–E8792. 10.1073/pnas.1807501115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furner IJ, Pumfrey JE. Cell fate in the shoot apical meristem of Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 1992:115(3):755–764. 10.1242/dev.115.3.755 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Ariza J, Brambilla V, Vicentini G, Landini M, Cerise M, Carrera E, Shrestha R, Chiozzotto R, Galbiati F, Caporali E, et al. A transcription factor coordinating internode elongation and photoperiodic signals in rice. Nat Plants. 2019:5(4):358–362. 10.1038/s41477-019-0401-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori Y, Nagai K, Furukawa S, Song XJ, Kawano R, Sakakibara H, Wu J, Matsumoto T, Yoshimura A, Kitano H, et al. The ethylene response factors SNORKEL1 and SNORKEL2 allow rice to adapt to deep water. Nature. 2009:460(7258):1026–1030. 10.1038/nature08258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Hu G, Han B.. Genome-wide survey and expression profiling of heat shock proteins and heat shock factors revealed overlapped and stress specific response under abiotic stresses in rice. Plant Sci. 2009: 176(4):583–590. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish VF, Sussex IM. A fate map of the Arabidopsis embryonic shoot apical meristem. Development. 1992:115(3):745–753. 10.1242/dev.115.3.745 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Kurata N. Disruption of KNOX gene suppression in leaf by introducing its cDNA in rice. Plant Sci. 2008:174(3):357–365. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.12.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh J, Hasegawa A, Kitano H, Nagato Y. A recessive heterochronic mutation, plastochron1, shortens the plastochron and elongates the vegetative phase in rice. Plant Cell. 1998:10(9):1511–1522. 10.1105/tpc.10.9.1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh J-I, Nonomura K-I, Ikeda K, Yamaki S, Inukai Y, Yamagishi H, Kitano H, Nagato Y. Rice plant development: from zygote to spikelet. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005:46(1):23–47. 10.1093/pcp/pci501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H, Nonoue Y, Yano M, Izawa T. A pair of floral regulators sets critical day length for Hd3a florigen expression in rice. Nat Genet. 2010:42(7):635–638. 10.1038/ng.606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, Veit B, Hake S. Expression of maize KNOTTED1 related homeobox genes in the shoot apical meristem predicts patterns of morphogenesis in the vegetative shoot. Development. 1994:120(2):405–413. 10.1242/dev.120.2.405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson RA, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW. GUS fusions: b-glucoronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 1987:6(13):3901–3907. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02730.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jegla DE, Sussex IM. Cell lineage patterns in the shoot meristem of the sunflower embryo in the dry seed. Dev Biol. 1989:131(1):215–225. 10.1016/S0012-1606(89)80053-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston R, Leiboff S, Scanlon MJ. Ontogeny of the sheathing leaf base in maize (Zea mays). New Phytol. 2015:205(1):306–315. 10.1111/nph.13010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johri MM, CoeEH, Jr. Clonal analysis of corn plant development. I. The development of the tassel and the ear shoot. Dev Biol. 1983:97:154–172. 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90073-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johri MM, Coe EH. Clonal analysis of corn plant development. Genetica. 1996:97(3):291–303. 10.1007/BF00055315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman PB. Development of the shoot of Oryza sativa L. II. Leaf histogenesis. Phytomorphology. 1959:9:277–311. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroha T, Nagai K, Gamuyao R, Wang DR, Furuta T, Nakamori M, Kitaoka T, Adachi K, Minami A, Mori Y, et al. Ethylene-gibberellin signaling underlies adaptation of rice to periodic flooding. Science. 2018:361(6398):181–186. 10.1126/science.aat1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeno A, Tsuda K. Micro-computed tomography to visualize vascular networks in maize stems. Bio Protoc. 2018:8(1):e2682. 10.21769/BioProtoc.2682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel CN, Poethig RS. Cell-lineage patterns in the shoot apical meristem of the germinating maize embryo. Planta. 1988:175(1):13–22. 10.1007/BF00402877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy D, Rothenberg M, Reece KS, Wu R. Characterization of the rice (Oryza sativa) actin gene family. Plant Mol Biol. 1990:15(2):257–268. 10.1007/BF00036912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai K, Mori Y, Ishikawa S, Furuta T, Gamuyao R, Niimi Y, Hobo T, Fukuda M, Kojima M, Takebayashi Y, et al. Antagonistic regulation of the gibberellic acid response during stem growth in rice. Nature. 2020:584(7819):109–114. 10.1038/s41586-020-2501-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poethig RS. Clonal analysis of cell lineage patterns in plant development. Am J Bot. 1987:74(4):581–594. 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1987.tb08679.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poethig RS, Coe EH Jr., Johri MM. Cell lineage patterns in maize embryogenesis: a clonal analysis. Dev Biol. 1986:117(2):392–404. 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90308-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poethig RS, Sussex IM. The developmental morphology and growth dynamics of the tobacco leaf. Planta. 1985a:165(2):158–169. 10.1007/BF00395038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poethig RS, Sussex IM. The cellular parameters of leaf development in tobacco: a clonal analysis. Planta. 1985b:165(2):170–184. 10.1007/BF00395039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poethig RS, Szymkowiak EJ. Clonal analysis of leaf development in maize. Maydica. 1995:40:67–76. 10.2307/2436864 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satina S, Blakeslee AF. Periclinal chimeras in datura stramonium in relation to development of leaf and flower. Am J Bot. 1941:28(10):862–871. 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1941.tb11017.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satina S, Blakeslee AF, Avery AG. Demonstration of the three germ layers in the shoot apex of datura by means of induced polyploidy in periclinal chimeras. Am J Bot. 1940:27(10):895–905. 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1940.tb13952.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon MJ. The polar auxin transport inhibitor N-1-naphthylphthalamic acid disrupts leaf initiation, KNOX protein regulation, and formation of leaf margins in maize. Plant Physiol. 2003:133(2):597–605. 10.1104/pp.103.026880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon MJ, Freeling M. Clonal sectors reveal that a specific meristematic domain is not utilized in the maize mutant narrow sheath. Dev Biol. 1997:182(1):52–66. 10.1006/dbio.1996.8452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres B. Plant cell identity. The role of position and lineage. Plant Physiol. 2001:125(1):112–114. 10.1104/pp.125.1.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres B, Wolkenfelt H, Willemsen V, Terlouw M, Lawson E, Dean C, Weisbeek P. Embryonic origin of the Arabidopsis primary root and root meristem initials. Development. 1994:120(9):2475–2487. 10.1242/dev.120.9.2475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Mislata A, Sablowski R. The pillars of land plants: new insights into stem development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2018:45:11–17. 10.1016/j.pbi.2018.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharman BC. Developmental anatomy of the shoot of Zea mays L. Ann Bot. 1942:6(2):245–282. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a088407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana O, Makila R, Lyu M, Amiryousefi A, Sanchez Rodriguez F, Wu MF, Sole-Gil A, Leal Gavarron M, Siligato R, Miyashima S, et al. High levels of auxin signalling define the stem-cell organizer of the vascular cambium. Nature. 2019:565(7740):485–489. 10.1038/s41586-018-0837-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeves TA, Sussex IM. Patterns in plant development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Steffens B, Geske T, Sauter M. Aerenchyma formation in the rice stem and its promotion by H2O2. New Phytol. 2011:190(2):369–378. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03496.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen DM. A reconstruction of cell development in the shoot apex of maize. Am J Bot. 1968:55(3):354–369. 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1968.tb07387.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RN, Dermen H. Determination of number and mitotic activity of shoot apical initial cells by analysis of mericlinal chimeras. Am J Bot. 1970:57(7):816–826. 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1970.tb09877.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takane M, Hoshikawa K. Science of the rice plant: morphology. Tokyo: Food and Agriculture Policy Research Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka A, Mita S, Ohta S, Kyozuka J, Shimamoto K, Nakamura K.. Enhancement of foreign gene expression by a dicot intron in rice but not in tobacco is correlated with an increased level of mRNA and an efficient splicing of the intron. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990:18(23):6767–6770. 10.1093/nar/18.23.6767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka W, Yamauchi T, Tsuda K. Genetic basis controlling rice plant architecture and its modification for breeding. Breed Sci. 2023:73(1):3–45. 10.1270/jsbbs.22088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toki S, Hara N, Ono K, Onodera H, Tagiri A, Oka S, Tanaka H. Early infection of scutellum tissue with Agrobacterium allows high-speed transformation of rice. Plant J. 2006:47(6):969–976. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02836.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda K, Abraham-Juarez MJ, Maeno A, Dong Z, Aromdee D, Meeley R, Shiroishi T, Nonomura KI, Hake S. KNOTTED1 cofactors, BLH12 and BLH14, regulate internode patterning and vein anastomosis in maize. Plant Cell. 2017:29(5):1105–1118. 10.1105/tpc.16.00967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda K, Suzuki T, Mimura M, Nonomura KI. Comparison of constitutive promoter activities and development of maize ubiquitin promoter- and gateway-based binary vectors for rice. Plant Biotechnol. 2022:39(2):139–146. 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.22.0120a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji N, Ma JF. The node, a hub for mineral nutrient distribution in graminaceous plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2014:19(9):556–563. 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji N, Ma JF. Node-controlled allocation of mineral elements in Poaceae. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017:39:18–24. 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J, Liu A, Chen X, Zhou X, Gao G, Wang W, Zhang X.. Expression analysis of nine rice heat shock protein genes under abiotic stresses and ABA treatment. J Plant Physiol. 2009:166(8):851–861. 10.1016/j.jplph.2008.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement