Abstract

Apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) is the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD), leading to earlier age of clinical onset and exacerbating pathologies. There is a critical need to identify protective targets. Recently, a rare APOE variant, APOE3-R136S (Christchurch), was found to protect against early-onset AD in a PSEN1-E280A carrier. In this study, we sought to determine if the R136S mutation also protects against APOE4-driven effects in LOAD. We generated tauopathy mouse and human iPSC-derived neuron models carrying human APOE4 with the homozygous or heterozygous R136S mutation. We found that the homozygous R136S mutation rescued APOE4-driven Tau pathology, neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation. The heterozygous R136S mutation partially protected against APOE4-driven neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation but not Tau pathology. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing revealed that the APOE4-R136S mutation increased disease-protective and diminished disease-associated cell populations in a gene dose-dependent manner. Thus, the APOE-R136S mutation protects against APOE4-driven AD pathologies, providing a target for therapeutic development against AD.

Subject terms: Alzheimer's disease, Neurodegeneration

Nelson et al. report that the APOE-R136S mutation protects against APOE4-promoted Alzheimer’s disease pathologies, including phosphorylated Tau accumulation, neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, in mouse and human neuron models.

Main

Apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) is the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD)1–3. It exacerbates AD-related pathologies, including amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques, Tau tangles, neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation4–16. As APOE4 carriers make up 55–75% of AD cases17–20, there is a critical need to investigate the roles of APOE4 in AD pathogenesis and to identify protective targets to mitigate its detrimental effects.

APOE is involved in lipid metabolism and highly expressed in the brain21, where it is primarily produced in astrocytes but also in neurons and microglia in response to stress22–28. APOE has two functional domains: an amino-terminal receptor-binding region (residues 136–150) and a carboxyl-terminal lipid-binding region (residues 244–275)2,29,30. A single residue change between APOE4(Arg112) and APOE3(Cys112) isoforms alters protein structure and function in both domains3,30–35. The receptor-binding region is enriched with positively charged amino acids and binds with negatively charged cell surface receptors, including heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs)30,35–37. The C-terminal domain of APOE weakly binds with HSPGs, and it also indirectly modifies the function of the N-terminal receptor-binding domain30. Therefore, mutations in both regions can directly or indirectly alter the binding of APOE to various cell surface receptors35–37. Variants of APOE with point mutations near or within these regions, such as APOE2(Cys112, Cys158)18,38, APOE3-V236E39,40 and APOE4-R251G40, are associated with protection against AD.

A recent discovery that a rare APOE variant, APOE3-R136S (APOE3-Christchurch)36, strongly protects against early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD) highlights the importance of studying rare variants of APOE in AD pathogenesis and protection. The reported patient was protected from the clinical effects of PSEN1-E280A, a highly penetrant mutation causing EOAD dementia41,42, for 28 years by the homozygous APOE3-R136S mutation36. This patient displayed extremely high Aβ pathology but minimal Tau burden, hippocampal atrophy and neuroinflammation36,43,44. A major functional effect of the R136S mutation is disruption of its binding to anionic HSPGs on cell surface36,45. Intriguingly, over the past decade, HSPGs have been revealed as essential players in the cellular uptake of Tau46–48. Tau accumulation and propagation during AD progression correlate with neurodegeneration and clinical effects49, which are major targets in the development of disease-modifying therapies for AD50,51. The differential contributions of APOE isoforms to Tau pathology, neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation are of great interest, yet the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. The discovery of AD-protective APOE-R136S mutation raises a fundamental question as to whether the R136S mutation can also protect against APOE4-driven pathologies in LOAD.

To address this question, we engineered the R136S mutation into the APOE4 allele background both in vivo in human APOE4 knock-in (E4-KI) mice52 and in vitro in human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) derived from a patient with AD with homozygous APOE4 (ref. 6). To investigate the effects of the R136S mutation in vivo under a disease-relevant condition, we cross-bred isogenic E4-KI and E4-R136S-KI mice with a widely used tauopathy mouse model expressing Tau-P301S (PS19 line)53. Using these PS19-APOE mouse and isogenic hiPSC models, in which any pathological changes are due solely to the introduction of this mutation overcoming APOE4 effects, we show that the R136S mutation robustly protects against APOE4-driven AD pathologies, and we present potential mechanisms underlying these effects.

Results

Generating tauopathy mice expressing human APOE4 or APOE4-R136S

To determine if the R136S mutation also protects against the detrimental effects of APOE4 in LOAD, we generated homozygous and heterozygous human APOE4-R136S-KI mice (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a−d), referred to as E4-S/S-KI and E4-R/S-KI mice, respectively. We used CRISPR–Cas-9-mediated gene editing to introduce the R136S mutation into the APOE4 locus in human E4-KI mice that were previously generated in our laboratory52. Genomic DNA (gDNA) sequencing verified on-target gene editing of R136 to S136 in APOE4 (Extended Data Fig. 1d) and found no changes within the top predicted potential off-target sites (Extended Data Fig. 1e). APOE and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) double immunostaining confirmed high APOE expression in astrocytes of E4-S/S-KI mice (Extended Data Fig. 1f), identical to that seen in astrocytes of the parental E4-KI mice (Extended Data Fig. 1f). For detailed APOE expression characterization, also see single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) analysis below.

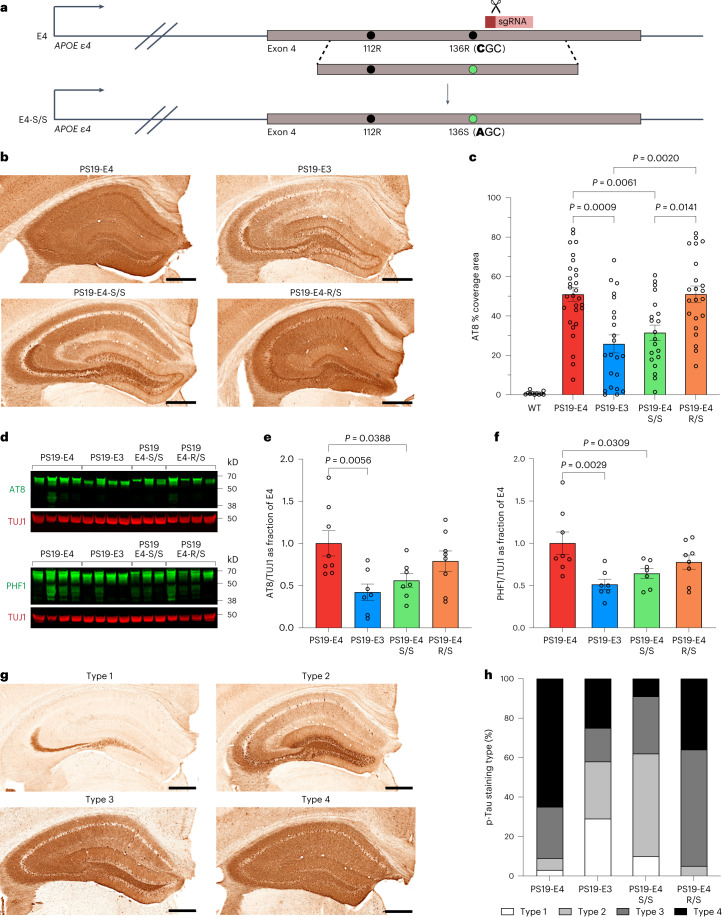

Fig. 1. Homozygous R136S mutation rescues APOE4-promoted Tau pathology in tauopathy mice.

a, Schematic of CRISPR–Cas-9-mediated gene editing strategy to generate human APOE4-R136S knock-in mice. b, Representative images of p-Tau immunostaining in hippocampus of 10-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S and PS19-E4-R/S mice with the AT8 monoclonal antibody. c, Quantification of the percent AT8 coverage area in the hippocampus of these mice (PS19-E4, n = 29; PS19-E3, n = 22; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 20; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 22) and WT mice (n = 11). d, Representative western blot images with p-Tau-specific AT8 or PHF1 antibody. TUJ1 was used as a loading control. e,f, Quantification of AT8+ (e) and PHF1+ (f) p-Tau levels in hippocampal lysates of PS19-E4 (n = 8), PS19-E3 (n = 7), PS19-E4-S/S (n = 7) and PS19-E4-R/S (n = 8) mice. p-Tau levels were normalized to TUJ1 first and then to those of PS19-E4 mice. g, Representative images of four AT8 staining patterns in the hippocampus. h, Distribution of four p-Tau staining patterns in the hippocampus of 10-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S and PS19-E4-R/S mice (PS19-E4, n = 29; PS19-E3, n = 22; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 20; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 22). Scale bars in b and g, 500 µm. Throughout, data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Differences between groups were determined by Welch’s ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparison test (c) or ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (e,f). Comparisons of P ≤ 0.05 are labeled on the graph.

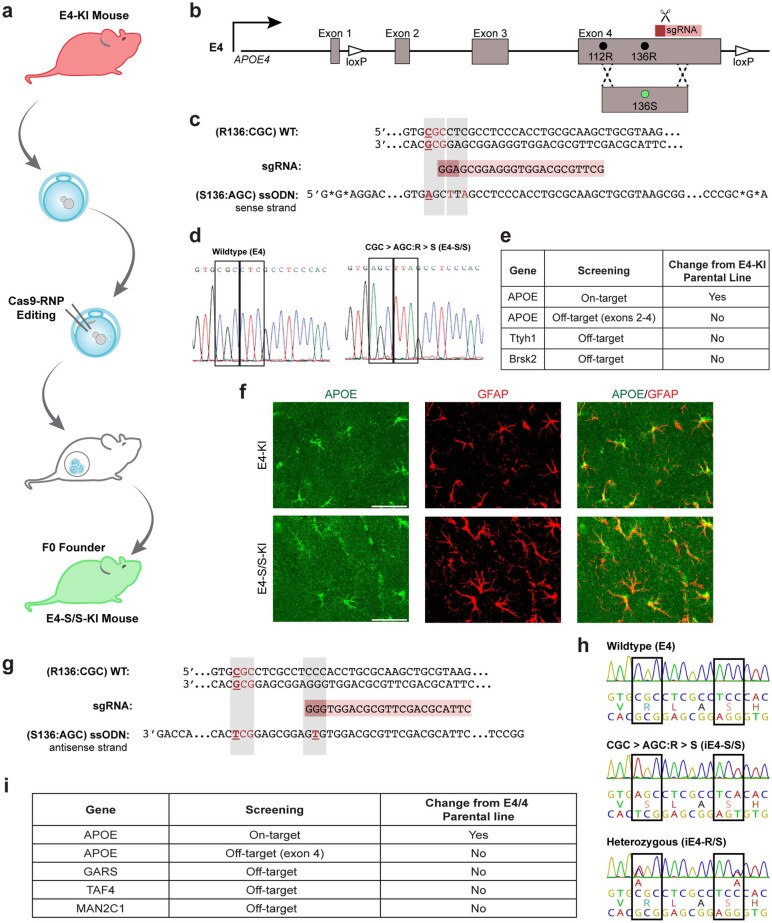

Extended Data Fig. 1. Generation of human APOE4-R136S knock-in mice and APOE4-R136S hiPSC lines by CRISPR/Cas-9-mediated gene editing.

a, Schematic of generating human APOE4-R136S knock-in (E4-S/S-KI) mice using CRISPR/Cas-9-mediated gene editing. b, Schematic of gene editing strategy to generate the R136S mutation in human E4-KI mice (with the loxP sites, unused in current gene-editing strategy) and to generate APOE4-R136S (E4-S/S) hiPSC lines (without the loxP sites). c, DNA sequences of WT human APOE4 loci encoding for R136, designed sgRNA, and single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides donor repair template encoding for S136 and silent mutation at PAM site for generating E4-S/S-KI mice. d, Sanger DNA sequencing of WT APOE4 and APOE4-S/S at and near the site encoding for residue 136 in E4-S/S-KI mice. e, Summary of on-target R136S editing in APOE4 and potential off-target mutation screening for knock-in mice. f, Representative immunofluorescent images of APOE (green) and GFAP (red) in CA1 hippocampal subfield in E4-KI and E4-S/S-KI mice at 12 months of age (scale bar, 50 μm). g, DNA sequences of WT APOE4 loci encoding for R136, designed sgRNA, and single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides donor repair template encoding for S136 and silent mutation at PAM site for generating E4-S/S hiPSC lines. h, Sanger DNA sequencing of WT E4, E4-S/S, and E4-R/S at and near the site encoding for residue 136 in hiPSC lines. i, Summary of on-target R136S editing in APOE4 and potential off-target mutation screening in hiPSC lines. Experiments depicted in representative images in f were performed on n = 3 mice per genotype using 2 brain sections per mouse, with reproducible data. WT, wildtype; sgRNA, single guide RNA; ssODN, single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide.

Reduced Tau pathology was a critical feature of the reported human case with resistance to autosomal-dominant EOAD, although amyloid pathology was exceedingly high in this individual36,43. Thus, we cross-bred the E4-KI and E4-S/S-KI mice with a tauopathy mouse model, PS19 (ref. 53). Four groups of mice with different APOE genotypes—PS19-E4, PS19-E4-S/S, PS19-E4-R/S and PS19-E3 (as control)—were used in this study. All mice were analyzed at an average age of 10 months to allow for the development of key AD pathologies7.

E4-S/S reduces Tau pathology in tauopathy mice

With these tauopathy mouse models, we first examined the levels of phosphorylated Tau (p-Tau) accumulation in the hippocampus by immunocytochemistry with an AT8 antibody. We observed heterogeneity in the percent AT8 coverage area within each group. This level of heterogeneity in hippocampal Tau pathology has been reported as a feature of age in the PS19 model54 and has also been reported in studies using PS19 mice crossed with human E4-KI or E3-KI mice7,55. PS19-E4 mice displayed roughly two-fold higher AT8+ p-Tau coverage area than PS19-E3 mice (Fig. 1b,c), as reported previously7,55. Remarkably, PS19-E4-S/S mice exhibited markedly reduced p-Tau accumulation, roughly to the levels in PS19-E3 mice (Fig. 1b,c). This reduction was not seen in PS19-E4-R/S mice (Fig. 1b,c), suggesting that the protection of APOE4-driven p-Tau accumulation in the hippocampus requires the homozygous R136S mutation. Unsurprisingly, we observed minimal AT8 immunopositivity in 10-month-old wild-type (WT) control mice (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 2a). No significant difference was observed in p-Tau pathology across various APOE genotype groups of 6-month-old mice, although PS19-E4-S/S mice had a trend toward lower p-Tau pathology (Extended Data Fig. 2b,e). Hippocampal lysates of PS19-E4 mice had significantly higher p-Tau levels than those of PS19-E3 mice at 10 months of age, as determined by western blotting with AT8 and PHF1 antibodies (Fig. 1d–f). Again, PS19-E4-S/S mice, but not PS19-E4-R/S mice, had significantly reduced p-Tau levels as compared to PS19-E4 mice at 10 months of age (Fig. 1d–f).

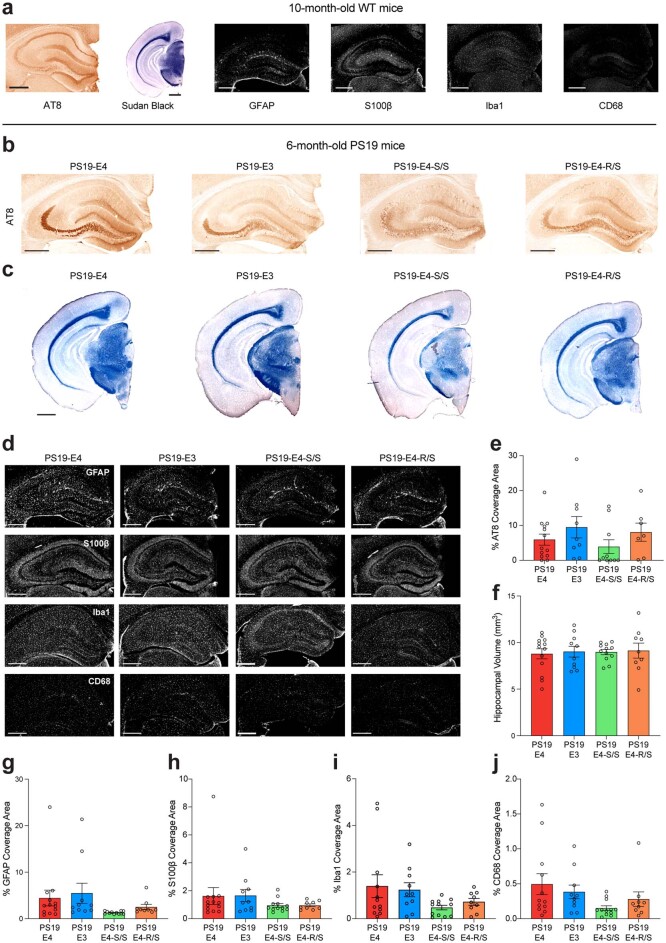

Extended Data Fig. 2. Histopathological analyses of 10-month-old WT and 6-month-old PS19-E3, PS19-E4, PS19-E4-S/S, and PS19-E4-R/S mice.

a, Representative images of 10-month-old WT mouse (n = 11) brain sections stained with AT8 monoclonal antibody to visualize p-Tau (scale bar, 500 µm), Sudan black to enhance hippocampal visualization (scale bar, 1 mm), GFAP and S100β to measure astrocytosis (scale bar, 500 µm), and Iba1 and CD68 to measure microgliosis (scale bar, 500 µm). b,c, Representative images of 6-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S, and PS19-E4-R/S mouse brain sections stained with AT8 antibody for p-Tau (scale bar, 500 µm) (b) or Sudan black (scale bar, 1 mm) (c). d, Representative images of GFAP and S100β immunostaining for astrocytes and reactive astrocytes, respectively, as well as Iba1 and CD68 immunostaining for microglia and reactive microglia, respective, in the hippocampus of 6-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S, and PS19-E4-R/S mice. Scale bar, 500 µm. e–j, Quantification of % AT8 coverage area (e), hippocampal volume (f), % GFAP coverage area (g), % S100β coverage area (h), % Iba1 coverage area (i), and % CD68 coverage area (j). In a–j, PS19-E4, n = 12; PS19-E3, n = 11; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 12; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 9; n=mice. Experiments depicted in representative images in a–d were performed using 2 brain sections per mouse, with reproducible data. Throughout, data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Differences between groups were determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (e,f) or Welch’s ANOVA followed with Dunnett T3 multiple comparison test (g-j); comparisons of p ≤ 0.05 were labeled on graph.

Previous studies reported distinct p-Tau staining patterns as functions of progressive tauopathy in PS19-E mice with different APOE genotypes7,11. We observed similar categories of p-Tau staining (Fig. 1g). Type 1 displays AT8 positivity in mossy fibers and hilus with occasional sparse CA3 and somatic staining; type 2 has additional dense, tangle-like staining in dentate gyrus (DG) granule cells (GCs), some staining in CA3 pyramidal cells and sparse neurite staining in the CA1 region; type 3 shows further staining in the stratum radiatum of the CA region, primarily neurite staining, with dense staining in only some of the soma; and type 4 has further staining over the entire hippocampus.

The most advanced type 4 p-Tau staining was enriched in PS19-E4 mice, with roughly 90% of sections analyzed showing type 3 or type 4 p-Tau staining (Fig. 1h). The early p-Tau staining types 1 and 2 were enriched in PS19-E3 mice (Fig. 1h), as seen previously7. The PS19-E4-S/S mice displayed the lowest fraction of type 4 p-Tau staining (~10%) and showed similar levels of enrichment of type 1 and type 2 staining to PS19-E3 mice (Fig. 1h). Notably, the PS19-E4-R/S mice still showed roughly 90% type 3 or type 4 p-Tau staining (Fig. 1h), with a slight preference for type 3 over type 4 p-Tau staining as compared to PS19-E4 mice, possibly indicating a slight slowing of APOE4-driven progression of p-Tau pathology.

As another measurement of p-Tau pathology, we quantified the number of AT8+ soma in the cell layer of the hippocampal CA1 subregion of 10-month-old mice. Both PS19-E4 and PS19-E4-R/S mice had significantly more AT8+ soma in CA1 than PS19-E3 and PS19-E4-S/S mice (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Notably, the number of AT8+ soma in the CA1 cell layer strongly correlated with the percent AT8 coverage area in the hippocampus (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Together, these data indicate that the R136S homozygosity is required to effectively protect against APOE4-driven p-Tau accumulation and progression of p-Tau staining patterns in this tauopathy mouse model.

Generating isogenic E4-S/S and E4-R/S hiPSC lines

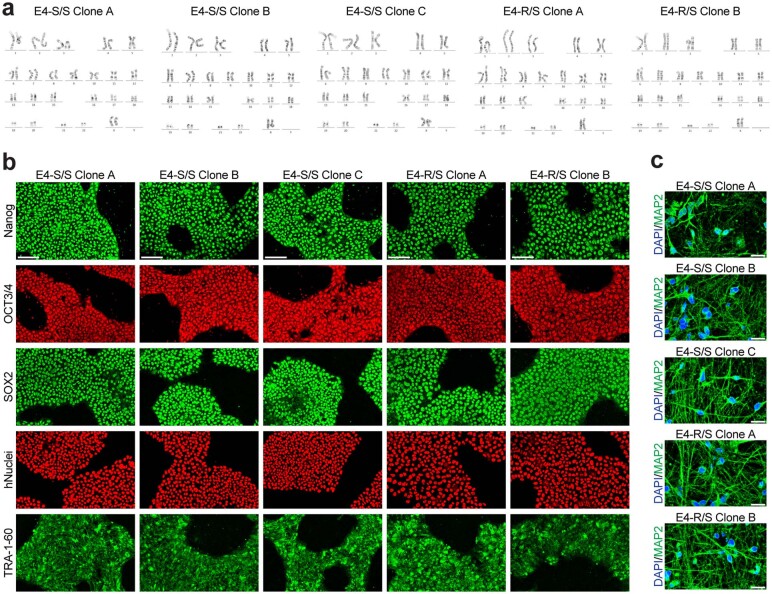

To determine the mechanisms underlying the protection of the R136S mutation against APOE4-driven Tau pathology, we further modeled it in hiPSC-derived neurons. A parental APOE4/4 hiPSC line was previously generated from a patient with AD homozygous for the APOE4 allele, which provided a human and disease-relevant cellular model6. From this APOE4/4 hiPSC line, we generated isogenic hiPSC lines with either the homozygous (E4-S/S) or the heterozygous (E4-R/S) R136S mutation using CRISPR–Cas-9-mediated gene editing (Extended Data Fig. 1g,h). gDNA sequencing verified the correct editing of R136 to S136 in APOE4 (Extended Data Fig. 1h) and found no mutations in the top predicted potential off-target sites (Extended Data Fig. 1i).

Five stable, isogenic hiPSC lines (three E4-S/S clones and two E4-R/S clones) were karyotyped to ensure no chromosomal abnormalities (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Additionally, they all expressed stem cell markers Nanog, OCT3/4, SOX2 and TRA-1-60 (Extended Data Fig. 3b). hiPSC lines were then differentiated into neurons expressing mature neuronal marker MAP2 (Extended Data Fig. 3c) via an optimized method using dual-SMAD inhibition6,56. Both the E4-S/S and E4-R/S neuronal cultures showed normal morphology, neurite outgrowth pattern and viability (Extended Data Fig. 3c). We then used the following isogenic hiPSC-derived neurons for further analyses: the parental E4 hiPSC line (E4), a previously generated isogenic APOE3 hiPSC line (E3)6 and the isogenic E4-S/S and E4-R/S hiPSC lines. Immunocytochemistry analysis confirmed that MAP2+ neurons expressed APOE (Supplementary Fig. 2a), as reported previously6. The neuronal cultures were also validated negative, via immunocytochemistry, for non-neuronal cell types, such as neural stem cells (SOX2), astrocytes (GFAP) and oligodendrocytes (Olig2) (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b). As reported previously6, the E4 neuron culture had a lower fraction of GABA+ inhibitory neurons than the E3 neuron culture (Supplementary Fig. 2c,d). The E4-S/S neuron cultures showed a similar proportion of GABA+ inhibitory neurons to the E3 neuron cultures (Supplementary Fig. 2c,d), suggesting that the R136S mutation may reduce APOE4’s detrimental effect on GABAergic neurons. The E4-S/S neurons also had a lower ratio of APOE fragment/full-length APOE than E4 neurons at both the individual hiPSC line level and the combined hiPSC line level (Supplementary Fig. 2e,f), suggesting that the R136S mutation results in less APOE4 fragmentation6.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Characterization of E4-S/S and E4-R/S hiPSC lines and neuronal differentiation.

a, Karyogram of E4-S/S-A, E4-S/S-B, E4-S/S-C, E4-R/S-A, and E4-R/S-B hiPSC lines. For all cell lines, metaphase was examined for n = 20 cells per line. b, Representative immunofluorescent images of pluripotent stem cell markers Nanog, OCT3/4, SOX2, hNuclei, and TRA-1-60 from E4-S/S-A, E4-S/S-B, E4-S/S-C, E4-R/S-A, and E4-R/S-B hiPSC lines (scale bar, 100 μm). c, Representative immunofluorescent images of mature neuronal marker MAP2 (green) and DAPI (blue) in 3-week-old neurons differentiated from E4-S/S-A, E4-S/S-B, E4-S/S-C, E4-R/S-A, and E4-R/S-B hiPSC lines (scale bar, 20 μm). Representative images were selected from n = 3 fields of view from each cell line.

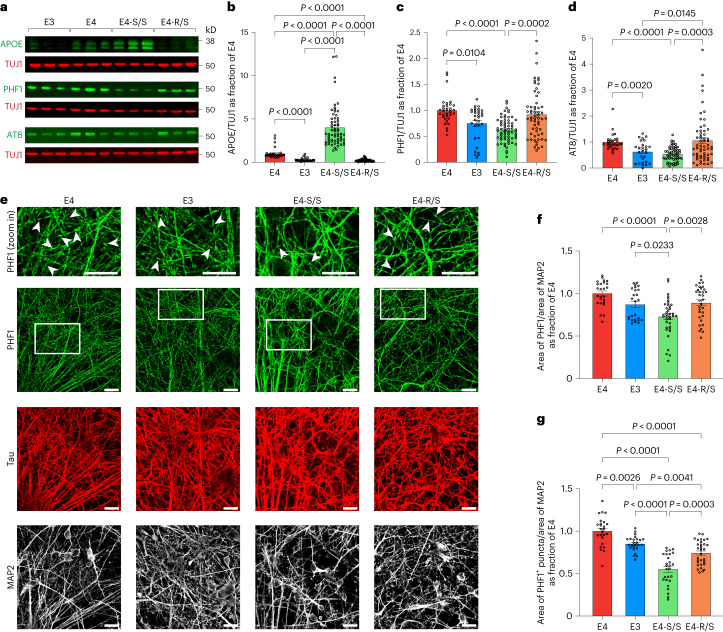

E4-S/S reduces p-Tau accumulation in human neurons

The effect of the R136S mutation in human neurons was first assessed by quantification of APOE levels via western blotting. The E4-S/S neurons had a five-fold increase in APOE protein levels compared to E4 neurons (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Because we did not observe a similar phenotype in PS19-E4-S/S mouse hippocampal lysates (Supplementary Fig. 4), this is likely an across-species difference, which warrants further study. The E4-R/S neurons did not show such an effect on APOE protein levels (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Fig. 3a).

Fig. 2. Homozygous R136S mutation protects against APOE4-induced p-Tau accumulation in human neurons.

a–d, Representative western blot images (a) and quantification of APOE (b), PHF1+ p-Tau (c) and AT8+ p-Tau (d) levels in lysates of E4, E3, E4-S/S or E4-R/S neurons. In b, APOE levels were normalized to those of E4. TUJ1 was used as loading control (E4, n = 32; E3, n = 31; E4-S/S, n = 64 (n = 24 from E4-S/S-A; n = 8 from E4-S/S-B; n = 32 from E4-S/S-C); E4-R/S, n = 59 (n = 31 from E4-R/S-A; n = 28 from E4-R/S-B)). In c, PHF1+ p-Tau levels were normalized to those of E4. TUJ1 was used as loading control (E4, n = 32; E3, n = 31; E4-S/S, n = 64 (n = 24 from E4-S/S-A; n = 8 from E4-S/S-B; n = 32 from E4-S/S-C); E4-R/S, n = 59 (n = 31 from E4-R/S-A; n = 28 from E4-R/S-B)). In d, AT8+ p-Tau levels were normalized to those of E4. TUJ1 was used as loading control (E4, n = 28; E3, n = 27; E4-S/S, n = 55 (n = 16 from E4-S/S-A; n = 11 from E4-S/S-B; n = 28 from E4-S/S-C); E4-R/S, n = 59 (n = 31 from E4-R/S-A; n = 28 from E4-R/S-B)). e, Representative images showing immunostaining of p-Tau (PHF1), total Tau and MAP2 in E4, E3, E4-S/S or E4-R/S human neurons, with some PHF1+ puncta (white arrowheads in insets). f,g, Quantification of fraction of the PHF1+ area over MAP2+ area (f) and fraction of PHF1+ puncta area over MAP2+ area (g) (E4, n = 25 fields of view; E3, n = 25 fields of view; E4-S/S, n = 38 fields of view; E4-R/S, n = 33 fields of view). The ratio of PHF1+ area (f) and PHF1+ puncta area (g) over MAP2 area was normalized to that of E4. Western blot data (b–d) were made up of at least three independent rounds of differentiation, and all data were combined. Scale bars (e), 20 µm. In b–d, n = biological replicates. Throughout, data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Differences between groups were determined by Welch’s ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparison test (b–d,g) or ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (f). Comparisons of P ≤ 0.05 are labeled on the graph.

Western blotting analysis of cell lysates with PHF1 and AT8 antibodies revealed that the E3 neurons had a significant reduction in p-Tau levels compared to E4 neurons (Fig. 2a,c,d and Supplementary Fig. 3b,c), confirming our previous report6. The E4-S/S neurons showed an approximately 40% reduction in p-Tau levels compared to E4 neurons at both the combined hiPSC line level (Fig. 2c,d) and the individual hiPSC line level (Supplementary Fig. 3b,c). Notably, E4-R/S neurons did not show the same reduction of p-Tau levels (Fig. 2a,c,d and Supplementary Fig. 3b,c).

Likewise, immunocytochemical staining with the PHF1 antibody also revealed an approximately 35% reduction in p-Tau levels in E4-S/S neurons versus E4 neurons (Fig. 2e,f), whereas no such effect was seen in E4-R/S neurons (Fig. 2e,f). We also observed some beading patterns in PHF1+ neurites, suggesting p-Tau aggregates and/or degenerating neurites, which were the least prevalent in E4-S/S neurons (Fig. 2e, arrowheads, and Fig. 2g). Taken together, these data illustrate that only the homozygous R136S mutation protects against APOE4-induced p-Tau accumulation in human neurons, in line with the in vivo observations in tauopathy mice (Fig. 1).

E4-S/S reduces HSPG-mediated Tau uptake by human neurons

Recent findings show that cell surface HSPGs mediate a large portion of neuronal uptake of Tau monomers and aggregates46,57. Additionally, neuronal uptake of exogenous Tau in culture can be competitively inhibited with the addition of heparin46,57. Notably, the APOE-R136S has severely reduced binding affinity to heparin, as the mutation occurs within the receptor-binding region of APOE36,45,58. By contrast, APOE4 has increased binding affinity (up to two-fold) for heparin and HSPG over APOE3 (refs. 32–35). We hypothesized that the E4-S/S-reduced p-Tau accumulation in human neurons was, in part, due to its defective HSPG binding and, consequently, the reduced Tau uptake promoted by APOE4 via HSPGs.

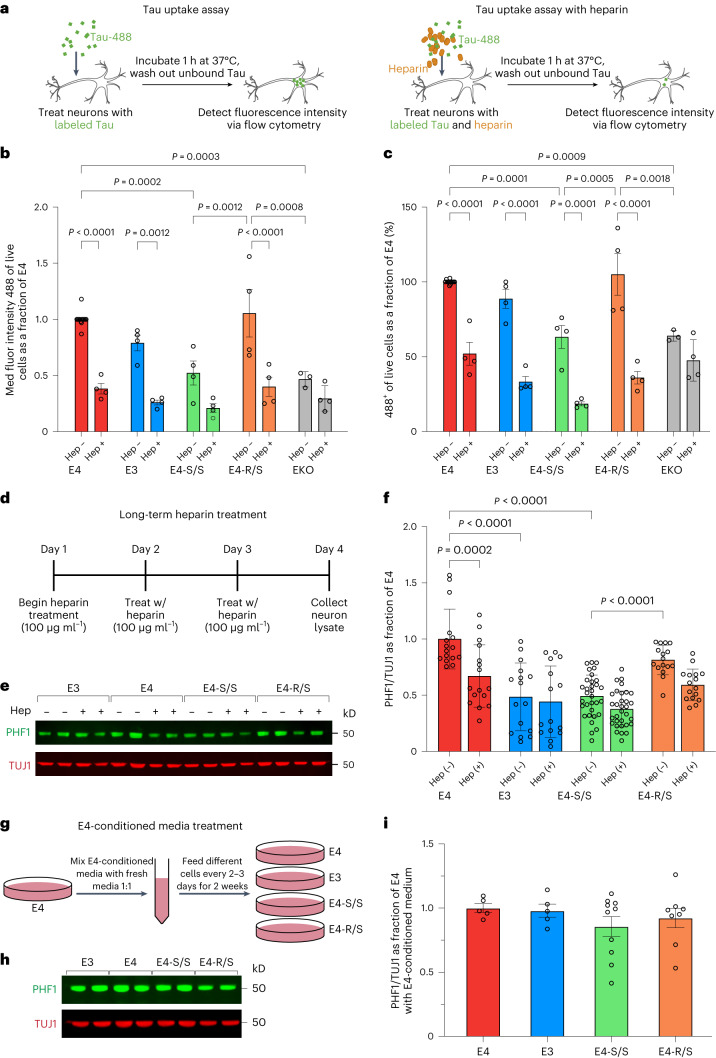

To test this hypothesis, we assessed the effects of E4-S/S and E4-R/S on Tau uptake using human neurons. We first labeled recombinant Tau protein (2N4R) with Alexa Fluor 488 fluorophore (Tau-488) and then treated neuronal cultures with 25 nM Tau-488 (Fig. 3a), as reported previously46,47,57. Flow cytometry was used to determine the differences in the internalization of exogenous Tau-488 by human neurons with different APOE genotypes. Neurons were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with either Tau-488 alone or Tau-488 together with 100 µg ml−1 heparin to inhibit Tau uptake via an HSPG-dependent pathway. We repeated the experiments for both conditions at 4 °C to prevent endocytosis so as not to conflate signal from surface-bound Tau-488 with internalized Tau-488. The detectable signal at 4 °C was negligible at this concentration of Tau-488 and incubation time (Extended Data Fig. 4a), as was previously reported46. We also treated E4 neurons with 25 nM unlabeled recombinant Tau and performed the same uptake experiment as a control to ensure that the 488 signal was not due to Tau incubation-induced cellular changes, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, that could lead to autofluorescence (Extended Data Fig. 4a).

Fig. 3. Homozygous R136S mutation protects against APOE4-induced p-Tau accumulation by reducing Tau uptake via the HSPG pathway.

a, Diagram of Tau-488 uptake assay. Neurons treated with either Tau-488 alone (left) or Tau-488 together with 100 µg ml−1 heparin (right) before flow cytometry analysis. b, Measurement of individual neuronal Tau-488 uptake (25 nM, 1-h incubation) based on MFI per cell in human neurons. c, Measurement of Tau-488 uptake (25 nM, 1-h incubation) based on percent Tau-488+ human neurons. In b,c, n = independent experiments and normalized to E4 MFI (b) or uptake (%) (c). E4, n = 13; E4+heparin, n = 4; E3, n = 4; E3+heparin, n = 4; E4-S/S, n = 4; E4-S/S+heparin, n = 4; E4-R/S, n = 4; E4-R/S+heparin, n = 4; EKO, n = 3; EKO+heparin, n = 4. Analysis was performed on a live cell population of estimated 5,000 cells for each sample. d, Experimental design for long-term heparin treatment of human neurons. e,f, Representative western blot images (e) and quantification of PHF1+ p-Tau levels (f) in lysates of E4, E3, E4-S/S or E4-R/S neurons under long-term heparin treatment. In f, PHF1+ p-Tau levels were normalized to those of E4. TUJ1 was used as loading control (E4, n = 16; E4+heparin, n = 16; E3, n = 16; E3+heparin, n = 15; E4-S/S, n = 32; E4-S/S+heparin, n = 32; E4-R/S, n = 16; E4-R/S+heparin, n = 16). g, Experimental design for E4 neuron-conditioned medium treatment of human neurons with different APOE genotypes. h,i, Representative western blot images (h) and quantification of PHF1+ p-Tau levels (i) in lysates of E4, E3, E4-S/S or E4-R/S neurons after E4 neuron-conditioned medium treatment. In i, PHF1+ p-Tau levels were normalized to those of E4. TUJ1 was used as loading control (E4, n = 5; E3, n = 5; E4-S/S, n = 10; E4-R/S, n = 10). In f,i, n =biological replicates. Throughout, data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Differences between groups were determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (b,c,f) or ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (i). Some comparisons of P ≤ 0.05 are labeled on the graph. Hep, heparin; fluor, fluorescence.

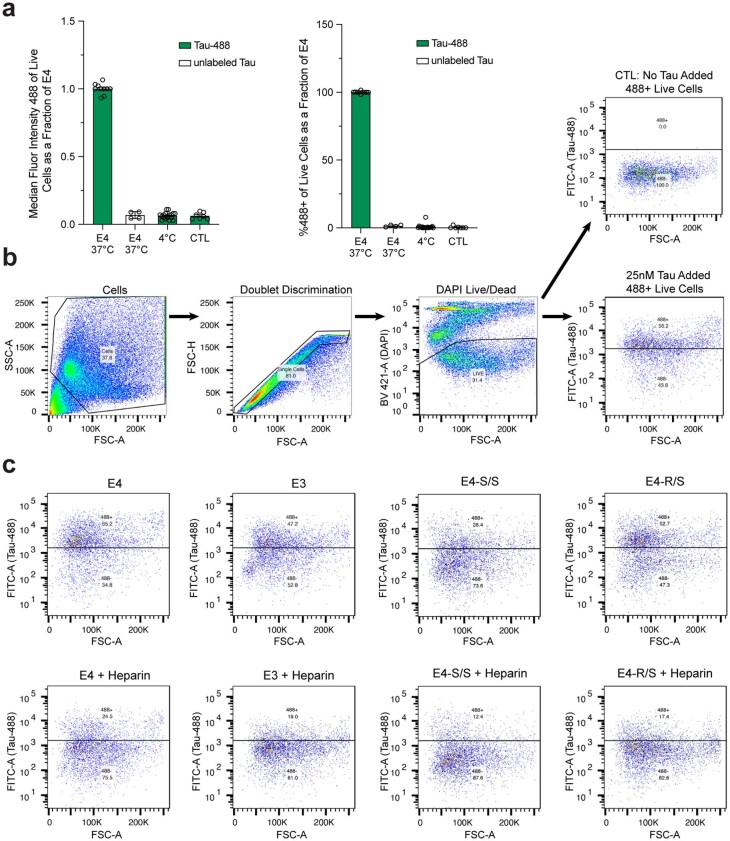

Extended Data Fig. 4. Measurement of neuronal uptake of Tau-488 by flow cytometry.

a, Internal controls of Tau-488 uptake assay as measured by median fluorescent intensity at 488 nm of live cell population (left) or % 488-positive live cell population (right) via flow cytometry. All values normalized to E4 cells at 37 °C, collected over separate experiments. Samples treated with Tau-488 are colored in green and samples treated with unlabeled tau are colored in white. E4 at 37 °C with Tau-488, n = 10; E4 at 37 °C with unlabeled Tau, n = 4; E4 at 4 °C with Tau-488, n = 18; E4 at 37 °C no Tau CTL, n = 7; n=independent experiment with unique biological samples. b, Gating strategy for Tau uptake assay. First, cells were gated on forward scatter/side scatter (FSC/SSC). Cells were then gated on forward scatter height (FSC-H) versus area (FSC-A) to discriminate doublets. Dead cells were removed from the analysis using nuclear stain with DAPI, and positive cells were determined by gating on a control (no Tau-488 added) population. c, Scatter plots of flow cytometry analysis of live cell population at 488 nm (FITC-A versus FSC-A) for E4, E3, E4-S/S, or E4-R/S neuronal cultures with or without the treatment with 100 µg/ml heparin. Roughly 1×105 to 5×105 events were recorded in each experiment. The live cell population analyzed was roughly 5000 cells for each sample. In a, data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m.

We analyzed the median fluorescence intensity (MFI), reflecting the median level of Tau-488 uptake at an individual cell level, in neurons with different APOE genotypes (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 4b,c). The E4-S/S neurons exhibited an approximately 50% reduction in MFI compared to E4 neurons (Fig. 3b), indicating reduced Tau-488 uptake. The E3 neurons also showed a trend of reduced Tau-488 uptake (~20%) compared to E4 neurons, although not reaching significance. The E4-R/S neurons showed no significant difference in MFI versus E4 neurons (Fig. 3b), suggesting no alteration in Tau-488 uptake. To clarify the role of APOE in Tau uptake by neurons, we also included an APOE knockout (EKO) human iPSC line that we generated previously6. The EKO neurons showed a marked decrease in Tau-488 uptake versus E4 neurons, to roughly the level of E4-S/S neurons (Fig. 3b). This suggests that (1) the APOE-independent Tau-488 uptake by EKO neurons occurs at a similar level to E4-S/S neurons and (2) the receptor-binding-defective R136S mutation diminishes the ability of APOE to functionally contribute to Tau-488 uptake in E4-S/S neurons, mimicking EKO neurons.

Heparin treatment significantly reduced MFI in E4, E3 and E4-R/S neurons (Fig. 3b), whereas the treatment led only to a trend toward lower MFI in E4-S/S neurons (Fig. 3b), indicating already decreased HSPG-dependent Tau uptake in E4-S/S neurons. The EKO neurons treated with heparin showed a similarly small decrease (Fig. 3b), which represents the APOE-independent but HSPG-dependent Tau-488 uptake. Notably, E4 neurons treated with heparin exhibited reduction of MFI (~40%) to levels not significantly different from E4-S/S neurons and EKO neurons without heparin treatment. Furthermore, we quantified the percentage of Tau-488+ cells, reflecting the proportion of cells with detectable levels of the internalized Tau-488 across the entire culture (Fig. 3c). Only E4-S/S and EKO neurons had a significantly reduced fraction (~30%) of cells with internalized Tau-488, as compared to E4 neurons (Fig. 3c). It is again notable that E4 neurons treated with heparin reduced the fraction of neurons with internalized Tau-488 to levels seen in E4-S/S neurons and EKO neurons without heparin treatment. The effect of heparin treatment on the fraction of neurons with internalized Tau-488 was similar in E4 and E4-R/S neurons (Fig. 3c). Taken together, these data suggest that E4-S/S and EKO neurons, but not E4-R/S neurons, have similarly reduced Tau uptake compared to E4 neurons, which may be due to the defective HSPG binding of E4-S/S and the lack of APOE, respectively.

Defective HSPG binding of E4-S/S protects against p-Tau accumulation

We next tested if the lowered HSPG-dependent Tau uptake, as seen after 1-h incubation with recombinant Tau in E4-S/S neurons, could contribute to protection against APOE4-induced endogenous p-Tau accumulation in human neurons. We designed an assay to measure the relative long-term effect of heparin treatment on endogenous levels of p-Tau in neuronal cultures (Fig. 3d). hiPSC-derived neurons were treated with 100 µg ml−1 heparin daily for three full days and then analyzed for p-Tau (Fig. 3d,e). Remarkably, this treatment lowered endogenous p-Tau levels in E4 neurons by approximately 25%, similar to those seen in untreated E4-S/S neurons (Fig. 3f). Notably, heparin treatment did not significantly alter endogenous p-Tau levels in E4-S/S neurons (Fig. 3f). These data suggest that the defective HSPG binding of the R136S mutation may contribute to the reduced APOE4-driven Tau accumulation in human neurons.

To further test this possibility, we asked whether the presence of E4 neuron-conditioned medium would diminish the APOE-isoform-dependent effects on p-Tau accumulation in various human neurons (Fig. 3g). In fact, treatment with E4 neuron-conditioned medium (1:1 mixed with fresh medium) for 2 weeks increased p-Tau accumulation in both E3 and E4-S/S neurons to the level of E4 neurons (Fig. 3h,i). Thus, the presence of exogenous APOE4, even with much higher endogenous APOE4-S/S levels (Fig. 2a,b), was sufficient to increase p-Tau accumulation in E4-S/S neurons to levels similar to those seen in E4 neurons. Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that homozygous R136S mutation protects against APOE4-induced p-Tau accumulation at least in part due to defective HSPG binding.

E4-S/S ameliorates neurodegeneration in tauopathy mice

In addition to limited Tau tangle burden, previous reports of a PSEN1 mutation carrier with the APOE3-R136S mutation also described protection from other AD pathologies, including neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation36,43,44. These pathologies can also be exacerbated in the presence of APOE4 in LOAD4,7,59. Thus, we sought to determine if the R136S mutation protects against APOE4-promoted neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in PS19-E mice.

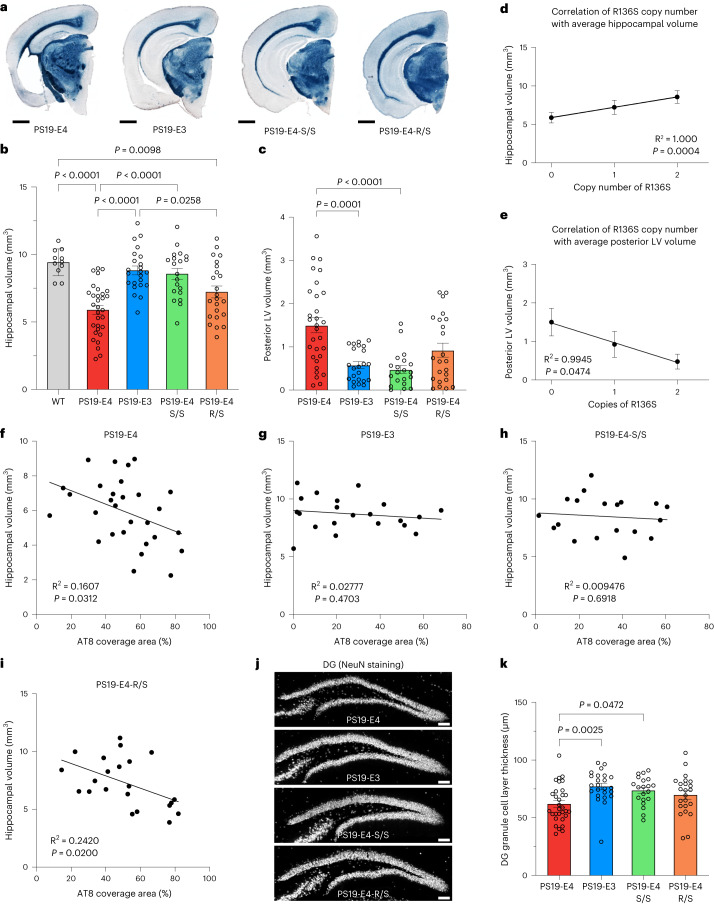

We evaluated the extent of neurodegeneration in 10-month-old PS19-E mice with different APOE genotypes and in WT mice. PS19-E4 mice exhibited significantly reduced hippocampal volume compared to WT and PS19-E3 mice (Fig. 4a,b and Extended Data Fig. 2a), as reported previously7,55. Strikingly, hippocampal atrophy of PS19-E4-S/S mice was reduced to similar levels of those seen in WT and PS19-E3 mice (Fig. 4a,b). We also observed a partial rescue of hippocampal atrophy in PS19-E4-R/S mice toward PS19-E3 levels (Fig. 4b). No significant difference was observed in hippocampal volume across various APOE genotype groups of 6-month-old mice (Extended Data Fig. 2c,f).

Fig. 4. The R136S mutation ameliorates APOE4-driven neurodegeneration in tauopathy mice.

a, Representative images of 10-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S and PS19-E4-R/S mouse brain sections stained with Sudan black to enhance hippocampal visualization (scale bar, 1 mm). b,c, Quantification of hippocampal volume (WT, n = 11; PS19-E4, n = 31; PS19-E3, n = 23; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 20; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 23; n = mice) (b) and posterior lateral ventricle volume (PS19-E4, n = 30; PS19-E3, n = 23; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 20; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 23; n = mice) (c). d,e, Correlation of the APOE4-R136S gene copy number with the average of hippocampal volume (PS19-E4, n = 31; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 20; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 23; n = mice) (d) or the average of posterior lateral ventricle volume (PS19-E4, n = 30; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 20; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 23; n = mice) (e) in PS19-E4 mice with 0, 1 or 2 copies of the APOE4-R136S gene mutation. f–i, Correlations between percent AT8 coverage area and hippocampal volume in 10-month-old PS19-E4 (n = 29) (f), PS19-E3 (n = 21) (g), PS19-E4-S/S (n = 19) (h) and PS19-E4-R/S (n = 22) (i) mice. j, Representative images of the DG stained for NeuN in 10-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S and PS19-E4-R/S mice (scale bar, 100 μm). k, Quantification of DG GC layer thickness in 10-month-old PS19-E4 (n = 30), PS19-E3 (n = 23), PS19-E4-S/S (n = 20) and PS19-E4-R/S (n = 23) mice. Throughout, data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. except for correlation plots. Differences between groups were determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (b,k) or Welch’s ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparison test (c). Comparisons of P ≤ 0.05 are labeled on the graph. Pearson’s correlation analysis (two-sided). LV, lateral ventricle.

Furthermore, 10-month-old PS19-E4 mice displayed significantly enlarged lateral ventricles compared to PS19-E3 mice, and this was protected in PS19-E4-S/S mice (Fig. 4a,c). Again, the PS19-E4-R/S mice had a partial rescue (Fig. 4c). Analysis of correlation between the APOE4-R136S copy number (0, 1 or 2) and the average of hippocampal volume or the average of posterior lateral ventricle volume revealed a clear gene dose-dependent effect of the R136S mutation on the protection of APOE4-promoted hippocampal degeneration (Fig. 4d,e).

In 10-month-old PS19-E4 mice, the AT8 (p-Tau) percent coverage area was negatively correlated with hippocampal volume (Fig. 4f), as shown previously7,55, indicating a deleterious role of p-Tau in hippocampal degeneration. Similarly, the number of AT8+ soma in CA1 cell layer was negatively correlated to hippocampal volume in PS19-E4 mice (Supplementary Fig. 1c). These relationships disappeared in PS19-E3 and PS19-E4-S/S mice (Fig. 4g,h and Supplementary Fig. 1d,e), suggesting that milder Tau pathology in these mice might not contribute to hippocampal degeneration. These relationships were still present in PS19-E4-R/S mice (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Fig. 1f), suggesting that the lack of protection against p-Tau pathology in PS19-E4-R/S mice (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1a) could be a contributing factor to neurodegeneration in these mice.

We also assessed neurodegeneration by measuring the thickness of the NeuN+ GC layer of the DG (Fig. 4j). PS19-E3 and PS19-E4-S/S mice showed a significant increase (~20%) in DG GC layer thickness over PS19-E4 mice (Fig. 4k). Again, PS19-E4-R/S mice showed a non-significant increase (12%) in DG GC layer thickness over PS19-E4 mice. Taken together, these data indicate that the R136S mutation ameliorates APOE4-driven neurodegeneration in the tauopathy mice, with the homozygous mutation being required for a full rescue.

E4-S/S reduces astrocytosis in tauopathy mice

We then tested whether the R136S mutation protects against APOE4-driven gliosis in 10-month-old PS19 mice with different APOE genotypes. We quantified astrocytosis with two methods: (1) percent astrocyte coverage area of the hippocampus to account for both glial cell number and morphological size changes and (2) discrete astrocyte number normalized to the hippocampal area to avoid the confounding effect of hippocampal atrophy. PS19-E4 mice displayed the highest hippocampal GFAP coverage area (Extended Data Fig. 5a) and cell numbers (Fig. 5a,b), and both PS19-E3 and PS19-E4-S/S mice had markedly reduced GFAP coverage area (Extended Data Fig. 5a) and cell numbers (Fig. 5a,b) versus PS19-E4 mice. Although PS19-E4-R/S mice showed a significant reduction in GFAP coverage area (Extended Data Fig. 5a) and cell number (Fig. 5a,b) compared to PS19-E4 mice, they still had significantly higher GFAP immunostaining than PS19-E4-S/S mice (Fig. 5a,b and Extended Data Fig. 5a). Similar results were obtained for quantifications of activated astrocyte (S100β+) coverage area and cell numbers (Fig. 5c,d and Extended Data Fig. 5b). Notably, a significant correlation was observed between the APOE4-R136S copy number and GFAP+ cell number (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Thus, the R136S mutation protects against APOE4-driven astrocytosis in a clear gene dose-dependent manner in this tauopathy model.

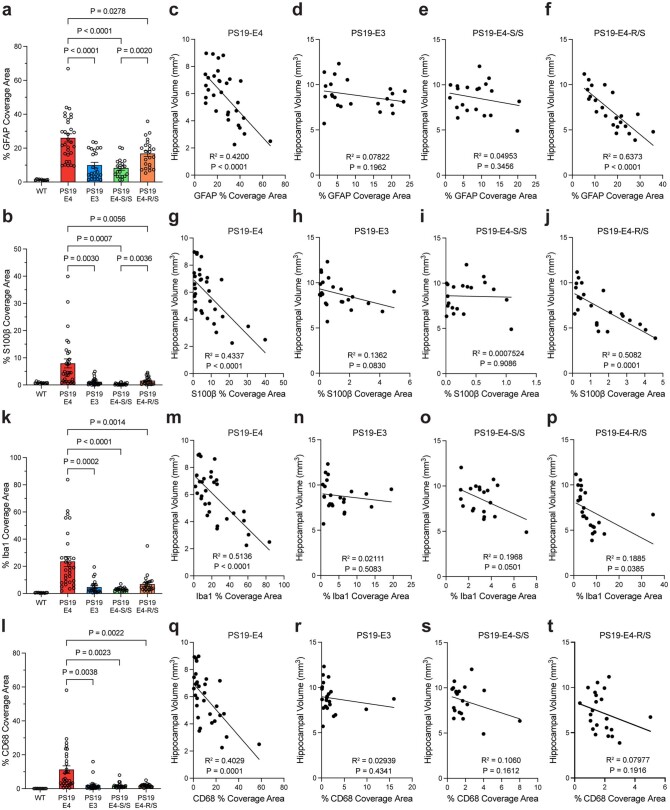

Extended Data Fig. 5. Quantifications and correlations between % coverage area of glial markers and hippocampal volume in tauopathy mice.

a,b, Quantification of % GFAP (a) or % S100β (b) coverage area in hippocampus of 10-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S, and PS19-E4-R/S mice. c–f, Correlation between % GFAP coverage area and hippocampal volume in PS19-E4 (n = 31) (c), PS19-E3 (n = 23) (d), PS19-E4-S/S (n = 20) (e), and PS19-E4-R/S (n = 23) (f) mice at 10 months of age. g–j, Correlation between % S100β coverage area and hippocampal volume in PS19-E4 (n = 31) (g), PS19-E3 (n = 23) (h), PS19-E4-S/S (n = 20) (i), and PS19-E4-R/S (n = 23) (j) mice at 10 months of age. k,l, Quantification of % Iba1 (k) or % CD68 (l) coverage area in hippocampus of 10-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S, and PS19-E4-R/S mice. m–p, Correlation between % Iba1 coverage area and hippocampal volume in PS19-E4 (n = 31) (m), PS19-E3 (n = 23) (n), PS19-E4-S/S (n = 20) (o), and PS19-E4-R/S (n = 23) (p) mice at 10 months of age. q–t, Correlation between % CD68 coverage area and hippocampal volume in PS19-E4 (n = 31) (q), PS19-E3 (n = 23) (r), PS19-E4-S/S (n = 20) (s), and PS19-E4-R/S (n = 23) (t) mice at 10 months of age. For all quantifications in a,b,k,l, WT, n = 11; PS19-E4, n = 31; PS19-E3, n = 24; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 21; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 23. In a,b,k,l, data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. and differences between groups were determined by Welch’s ANOVA followed with Dunnett T3 multiple comparison test; comparisons of p ≤ 0.05 were labeled on graph. Pearson’s correlation analysis (two-sided).

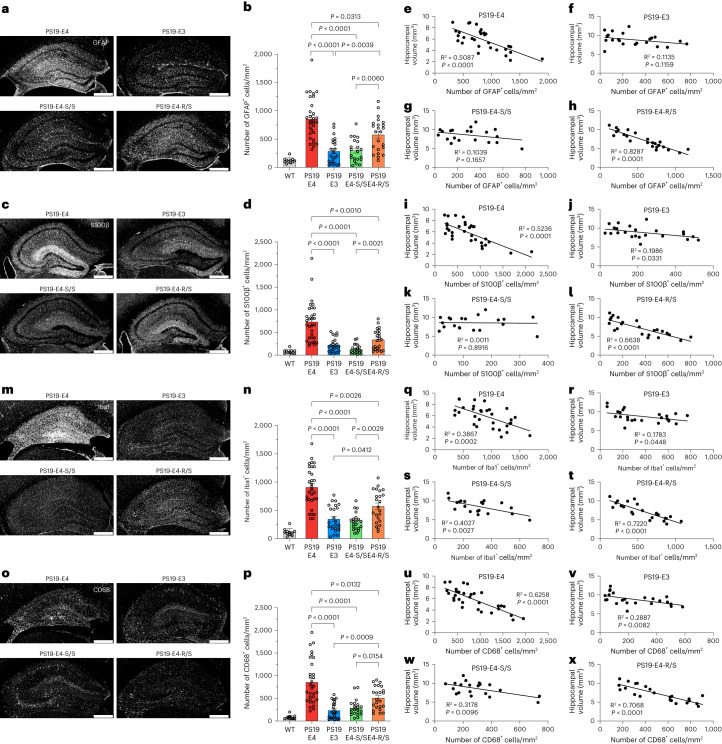

Fig. 5. The R136S mutation reduces APOE4-driven gliosis in tauopathy mice.

a,b, Representative images of GFAP immunostaining of astrocytes in the hippocampus of 10-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S and PS19-E4-R/S mice (a) and quantification of the number of GFAP+ cells per mm2 (b) in the hippocampus of these mice and WT mice. c,d, Representative images of S100β immunostaining of astrocytes in the hippocampus of 10-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S and PS19-E4-R/S mice (c) and quantification of the number of S100β+ cells per mm2 (d) in the hippocampus of these mice and WT mice. e–h, Correlations between GFAP+ cells per mm2 and hippocampal volume in PS19-E4 (n = 31) (e), PS19-E3 (n = 23) (f), PS19-E4-S/S (n = 20) (g) and PS19-E4-R/S (n = 23) (h) mice. i–l, Correlations between S100β+ cells per mm2 and hippocampal volume in PS19-E4 (n = 31) (i), PS19-E3 (n = 23) (j), PS19-E4-S/S (n = 20) (k) and PS19-E4-R/S (n = 23) (l) mice. m,n, Representative images of Iba1 immunostaining of microglia in the hippocampus of 10-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S and PS19-E4-R/S mice (m) and quantification of the number of Iba1+ cells per mm2 (n) in the hippocampus of these mice and WT mice. o,p, Representative images of CD68 immunostaining of microglia in the hippocampus of 10-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S and PS19-E4-R/S mice (o) and quantification of the number of CD68+ cells per mm2 (p) in the hippocampus of these mice and WT mice. q–t, Correlations between Iba1+ cells per mm2 and hippocampal volume in PS19-E4 (n = 31) (q), PS19-E3 (n = 23) (r), PS19-E4-S/S (n = 20) (s) and PS19-E4-R/S (n = 23) (t) mice. u–x, Correlations between CD68+ cells per mm2 and hippocampal volume in PS19-E4 (n = 31) (u), PS19-E3 (n = 23) (v), PS19-E4-S/S (n = 20) (w) and PS19-E4-R/S (n = 23) (x) mice. For all quantifications in b,d,n,p, WT, n = 11; PS19-E4, n = 31; PS19-E3, n = 24; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 21; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 23. Scale bars, 500 µm in a,c,m,o. Throughout, data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. In b,d,n,p, differences between groups were determined by Welch’s ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparison test. Comparisons of P ≤ 0.05 are labeled on the graph. Pearson’s correlation analysis (two-sided).

PS19 mice at 6 months of age did not show the same differences in astrocytosis across APOE genotype groups, although PS19-E4-S/S mice had a trend toward lower astrocytosis as compared to PS19-E4 mice (Extended Data Fig. 2d,g,h). This suggests that the protection of R136S mutation against APOE4-driven astrocytosis in the context of tauopathy starts at about or after 6 months of age.

Notably, both GFAP and S100β coverage areas (Extended Data Fig. 5c,g) and cell numbers (Fig. 5e,i) inversely correlated with hippocampal volume in 10-month-old PS19-E4 mice, suggesting the contribution of astrocytosis to hippocampal degeneration, as reported previously7. This correlation was mostly eliminated in PS19-E3 mice (Fig. 5f,j and Extended Data Fig. 5d,h) and PS19-E4-S/S mice (Fig. 5g,k and Extended Data Fig. 5e,i), suggesting that milder astrocytosis in these mice might not contribute to hippocampal degeneration. However, this relationship was preserved in PS19-E4-R/S mice (Fig. 5h,l and Extended Data Fig. 5f,j), suggesting that moderate astrocytosis is sufficient to contribute to hippocampal degeneration.

Although mild Tau pathology in PS19-E3 and PS19-E4-S/S mice may not contribute to hippocampal degeneration (Fig. 4g,h), it positively correlated with astrocytosis (Supplementary Fig. 6e,f,i,j). This suggests that mild Tau pathology can induce mild astrocytosis, although the latter may not be sufficient to contribute to hippocampal degeneration (Fig. 5f,g,j,k). In PS19-E4-R/S mice, in which severe Tau pathology (Fig. 1c,e,f) and moderate astrocytosis (Fig. 5b,d) occurred, the Tau pathology positively, albeit weakly, correlated with astrocytosis (Supplementary Fig. 6m,n). Thus, in the presence of severe Tau pathology and moderate astrocytosis, both pathologies contribute to hippocampal degeneration (Figs. 4i and 5h,l). In PS19-E4 mice, in which both severe Tau pathology (Fig. 1c,e,f) and severe astrocytosis (Fig. 5b,d) occurred, Tau pathology had a trending correlation with astrocytosis (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b). These findings suggest that the astrocytosis might reach a plateau in PS19-E4 mice. Notably, in the presence of both severe Tau pathology and severe astrocytosis, both pathologies contribute to hippocampal degeneration (Figs. 4f and 5e,i and Extended Data Fig. 5c,g).

E4-S/S reduces microgliosis in tauopathy mice

We next surveyed hippocampal microgliosis via immunostaining of Iba1 (Fig. 5m), a marker for total microglial population, and CD68 (Fig. 5o), a marker of activated microglia, in 10-month-old PS19 mice with different APOE genotypes. The PS19-E4 mice exhibited significantly higher microglia immunoreactivity (both coverage area and cell number) via measurements of both markers than the PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S and PS19-E4-R/S mice (Fig. 5m,n,o,p and Extended Data Fig. 5k,l). The PS19-E4-R/S mice showed significantly higher Iba1+ and CD68+ cell numbers than PS19-E4-S/S mice (Fig. 5n,p), suggesting an intermediate level of protection against microgliosis. This was confirmed by significant correlation of the APOE4-R136S copy number to Iba1+ cell number (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Together, these data indicate that the R136S mutation protects against APOE4-promoted microgliosis in the context of tauopathy in a gene dose-dependent manner.

In the 6-month-old PS19 mice, we did not observe the same differences in microgliosis across APOE genotype groups. The PS19-E4-S/S mice did show a trend toward lower microgliosis as compared to PS19-E4 mice (Extended Data Fig. 2d,i,j), suggesting that the E4-S/S protection against microgliosis may start at about or after 6 months of age.

Similar to findings of astrocytosis, both Iba1 and CD68 coverage areas (Extended Data Fig. 5m,q) and cell numbers (Fig. 5q,u) inversely correlated with hippocampal volume in 10-month-old PS19-E4 and PS19-E4-R/S mice (Fig. 5t,x and Extended Data Fig. 5p,t), suggesting the contribution of microgliosis to hippocampal degeneration, as reported in previous studies7,55. Unlike the data in astrocytosis, the relationship between microgliosis and hippocampal degeneration in PS19-E3 and PS19-E4 mice was somewhat preserved (Fig. 5r,s,v,w).

Similar to findings of astrocytosis, mild Tau pathology in PS19-E3 and PS19-E4-S/S mice may not contribute to hippocampal degeneration (Fig. 4g,h) yet positively correlates with microgliosis (Supplementary Fig. 6g,h,k,l). This suggests that mild Tau pathology can induce mild microgliosis. Interestingly, mild microgliosis negatively correlated with hippocampal volume in PS19-E3 and PS19-E4-S/S mice (Fig. 5r,s,v,w), suggesting that mild microgliosis is likely more toxic than mild astrocytosis and sufficient to cause hippocampal degeneration (Fig. 5f,g,k). In PS19-E4-R/S mice, in which severe Tau pathology (Fig. 1c,e,f) and moderate microgliosis (Fig. 5n,p) occurred, Tau pathology positively correlated with microgliosis (Supplementary Fig. 6o,p). Thus, in the presence of severe Tau pathology and moderate microgliosis, both pathologies contribute to hippocampal degeneration (Figs. 4i and 5t,x). Interestingly, in PS19-E4 mice, in which both severe Tau pathology (Fig. 1c,e,f) and severe microgliosis (Fig. 5n,p) occurred, Tau pathology significantly correlated with only CD68+ (active) microgliosis (Supplementary Fig. 6d) but not Iba1+ (general) microgliosis (Supplementary Fig. 6c). These data indicate that the general microgliosis might reach a plateau in PS19-E4 mice. Notably, in the presence of both severe Tau pathology and severe microgliosis, both pathologies contribute to hippocampal degeneration (Figs. 4f and 5q,u and Extended Data Fig. 5m,q).

In all, these findings indicate that the homozygous and, to a lesser extent, heterozygous R136S mutation protects against APOE4-driven astrocytosis and microgliosis in the context of tauopathy in an age-dependent manner, which can lead to reduced hippocampal neurodegeneration and atrophy.

E4-S/S rescues transcriptomic changes in neurons and oligodendrocytes

We next evaluated whether the R136S mutation affects the transcriptomic signature of the hippocampus at a cell-type-specific level. We performed snRNA-seq on isolated hippocampi from 10-month-old PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S and PS19-E4-R/S mice. The dataset contained 175,080 nuclei covering 26,422 genes after normalization and filtering (Extended Data Fig. 6). Unsupervised clustering by the Louvain algorithm60 and visualization by uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) produced 38 distinct cell clusters (Fig. 6a). Based on canonical marker gene expression, we identified 16 excitatory neuron clusters (1, 4, 6–8, 11, 15, 18, 20, 22–24, 26, 28, 30 and 33), five inhibitory neuron clusters (5, 10, 12, 31 and 34) and 17 non-neuronal clusters, including three oligodendrocyte clusters (2, 3 and 9), two astrocyte clusters (13 and 36), two microglia clusters (17 and 19) and one oligodendrocyte progenitor cell (OPC) cluster (14) (Fig. 6a, Extended Data Fig. 6a,b and Supplementary Table 1). As expected, APOE was highly expressed in astrocytes (13 and 36) and, to a lesser extent, in microglia (17 and 19) in all groups of mice (Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 8a,e). Some neurons and oligodendrocytes also express APOE (Fig. 6b), as we previously reported22,55. No significant difference was observed in APOE expression in each cell cluster across various APOE genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 7).

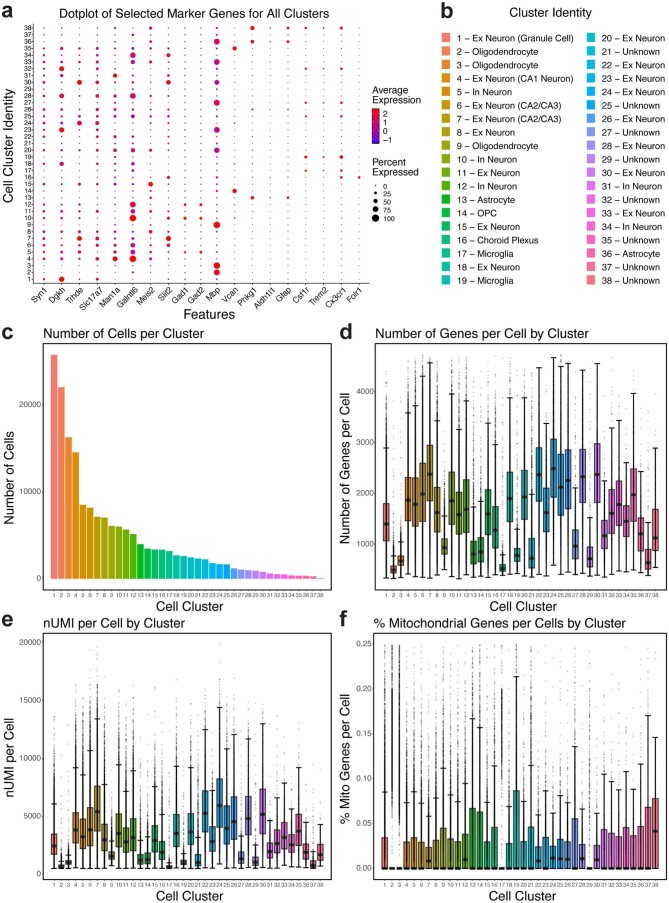

Extended Data Fig. 6. Quality control measures in snRNA-seq analysis of tauopathy mice with different APOE genotypes.

a, Dot-plot depicting normalized average expression of selected cell identity marker genes for all 38 distinct hippocampal cell clusters from mice at 10 months of age. b, Cluster identity of 38 distinct cell types. c, The number of cells per cluster. d, The number of genes per cell in each cluster (± s.e.m). e, The number of nUMI (unique molecular identified) per cell in each cluster (± s.e.m). f, The % mitochondrial genes per cell in each cluster (± s.e.m). Number of cells (n) for each cell cluster can be found in c. For details of the analyses, see Methods.

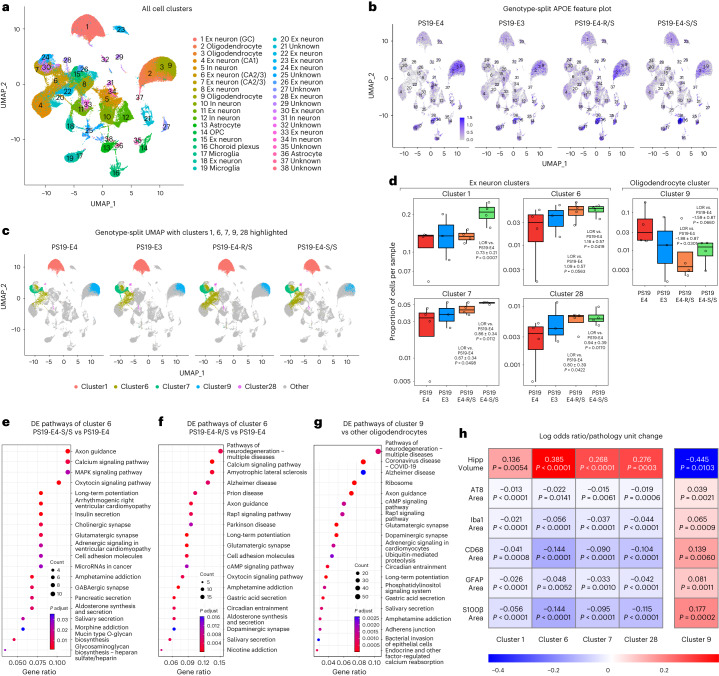

Fig. 6. snRNA-seq reveals protective effects of the R136S mutation on APOE4-driven neuronal and oligodendrocytic deficits in mice.

a, UMAP projection of 38 distinct cell clusters in hippocampi of 10-month-old PS19-E4 (n = 4), PS19-E3 (n = 3), PS19-E4-S/S (n = 4) and PS19-E4-R/S (n = 4) mice. b, Feature plot showing relative levels of normalized human APOE gene expression across all 38 hippocampal cell clusters by APOE genotype (PS19-E4, n = 4; PS19-E3, n = 3; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 4; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 4; n = mice). c, UMAP projection highlighting hippocampal cell clusters 1, 6, 7, 9 and 28 for each genotype group. d, Box plot of the proportion of cells from each sample in clusters 1, 6, 7, 9 and 28 in PS19-E4 (n = 4), PS19-E3 (n = 3), PS19-E4-R/S (n = 4), and PS19-E4-S/S (n = 4) mice. The lower, middle and upper hinges of the box plots correspond to the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The upper whisker of the box plot extends from the upper hinge to the largest value no further than 1.5 Å~ IQR from the upper hinge. IQR, interquartile range, or distance between the 25th and 75th percentiles. The lower whisker extends from the lower hinge to the smallest value at most 1.5 Å~ IQR from the lower hinge. The LORs are the mean ± s.e.m. estimates of LOR for these clusters, which represents the change in the log odds of cells per sample from PS19-E3, PS19-E4-R/S or PS19-E4-S/S mice belonging to the respective clusters compared to the log odds of cells per sample from PS19-E4 mice. e,f, KEGG pathway enrichment dot plot of top 20 pathways significantly enriched for DE genes of neuronal cluster 6 in PS19-E4-S/S (e) or PS19-E4-R/S (f) versus PS19-E4 mice. P values are based on a two-sided hypergeometric test and are adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Gene ratio represents the proportion of genes in the respective gene set that are deemed to be DE using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test as implemented in the FindMarkers function in Seurat. g, KEGG pathway enrichment dot plot of top 20 pathways significantly enriched for DE genes of oligodendrocyte cluster 9 versus oligodendrocyte cluster 2. h, Heat map plot of LOR per unit change in each pathological measurement for clusters 1, 6, 7, 9 and 28. The LOR represents the mean estimate of the change in the log odds of cells per sample from a given animal model, corresponding to a unit change in a given histopathological parameter. Associations with pathologies are colored (negative associations, blue; positive associations, red). P values in d are from fits to a GLMM_AM, and P values in h are from fits to a GLMM_histopathology; the associated tests are two-sided. All error bars represent s.e.m. Ex neuron, excitatory neuron; In neuron, inhibitory neuron.

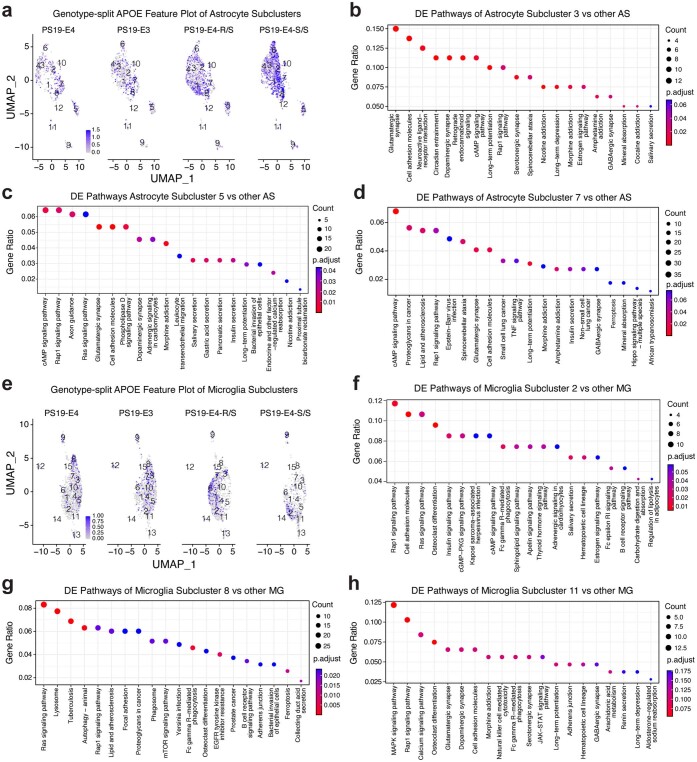

Extended Data Fig. 8. snRNA-seq analysis of astrocyte and microglia subclusters.

a, Feature plot showing relative levels of normalized human APOE gene expression across all 12 astrocyte subclusters by APOE genotype from mice at 10 months of age. b–d, KEGG pathway enrichment dot-plot of top 20 pathways significantly enriched for DE genes of astrocyte subclusters 3 (b), 5 (c), and 7 (d) versus other astrocyte subclusters. e, Feature plot showing relative levels of normalized human APOE gene expression across all 15 microglia subclusters by APOE genotype from mice at 10 months of age. f–h, KEGG pathway enrichment dot-plot of top 20 pathways significantly enriched for DE genes of microglia subclusters 2 (f), 8 (g), and 11 (h) versus other microglia subclusters. In b–d and f–h, P-values are based on a two-sided hypergeometric test and are adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Gene Ratio represents the proportion of genes in the respective gene set that are deemed to be differentially expressed using the two-sided Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test as implemented in the FindMarkers function in Seurat.

To further examine cell-type-specific alterations in PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S and PS19-E4-R/S mice versus PS19-E4 mice, we used log odds ratio (LOR) estimates from a generalized linear mixed-effects model to assess association with animal models (GLMM_AM). We discovered clusters in which there was a significant change in the likelihood that the cluster contained more or fewer cells from PS19-E4-S/S or PS19-E4-R/S mice than from PS19-E4 mice. For example, excitatory neuron cluster 1 (GC) and cluster 6 (CA2/3) had significantly higher odds of containing cells from PS19-E4-S/S mice than from PS19-E4 mice (Fig. 6c,d and Supplementary Table 1), suggesting that E4-S/S promotes the survival of, or protects against the loss of, these neuronal subpopulations. Excitatory neuron clusters 7 (CA2/3) and 28 had significantly higher odds of containing cells from either PS19-E4-S/S or PS19-E4-R/S mice than from PS19-E4 mice (Fig. 6c,d and Supplementary Table 1), suggesting that both E4-S/S and E4-R/S promote the survival of, or protect against the loss of, these neuronal subpopulations.

Analyses of differentially expressed (DE) genes and their enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways in PS19-E4-S/S or PS19-E4-R/S mice versus PS19-E4 mice revealed that the top enriched DE pathways in these clusters were indicative of neuronal health and function, including axon guidance, synaptic integrity and long-term potentiation (Fig. 6e,f for cluster 6; Extended Data Fig. 7a–f for clusters 1, 7 and 28; and Supplementary Table 1 for clusters 1, 6, 7 and 28). These suggest that even heterozygous R136S mutation provides protection against APOE4 effects in these clusters at the transcriptomic level. Notably, some DE pathways did differ based on the R136S gene dose. For example, some neurodegenerative disease-related pathways appeared only in the comparison of PS19-E4-R/S versus PS19-E4 mice, and heparin sulfate biosynthesis pathways appeared only in the comparison of PS19-E4-S/S versus PS19-E4 mice (Fig. 6e,f, Extended Data Fig. 7c–f and Supplementary Table 1). This suggests gene dose-related differential effects of APOE4-R136S mutation on these pathways in some neuronal clusters.

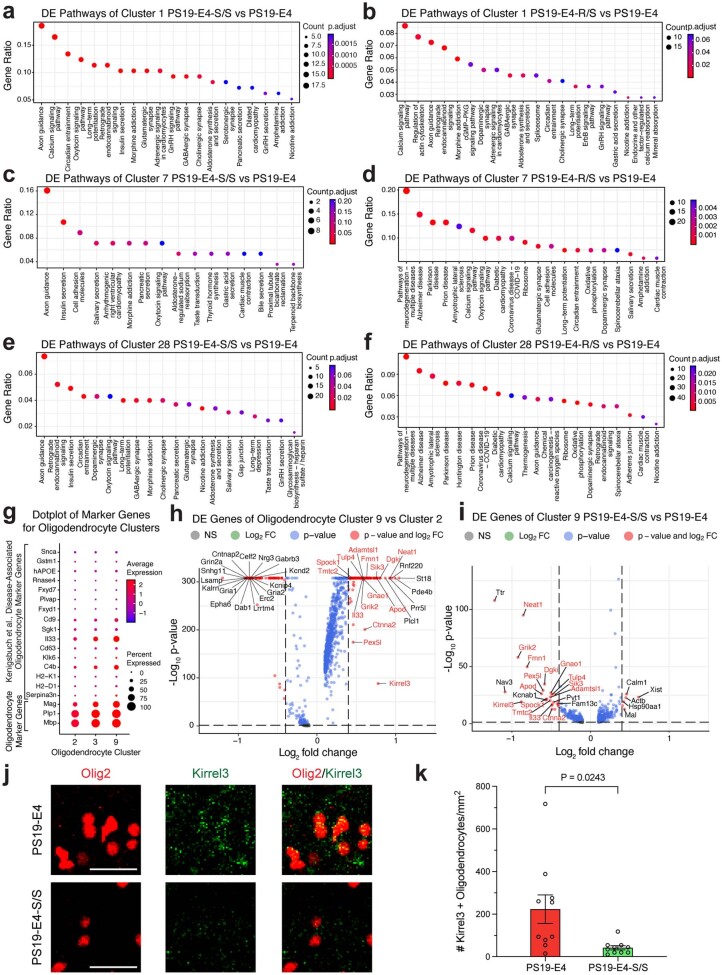

Extended Data Fig. 7. snRNA-seq analysis of disease-protective neuronal clusters and disease-associated oligodendrocyte cluster.

a,b, KEGG pathway enrichment dot-plot of top 20 pathways significantly enriched for DE genes of neuronal cluster 1 in PS19-E4-S/S (a) or PS19-E4-R/S (b) versus PS19-E4 mice at 10 months of age. c,d, KEGG pathway enrichment dot-plot of top 20 pathways significantly enriched for DE genes of neuronal cluster 7 in PS19-E4-S/S (c) or PS19-E4-R/S (d) versus PS19-E4 mice at 10 months of age. e,f, KEGG pathway enrichment dot-plot of top 20 pathways significantly enriched for DE genes of neuronal cluster 28 in PS19-E4-S/S (e) or PS19-E4-R/S (f) versus PS19-E4 mice at 10 months of age. g, Dot-plot normalized average expression of selected homeostatic and disease-associated oligodendrocyte (DAO) marker genes for oligodendrocyte clusters 2, 3, and 9. h, Volcano plot for top DE genes of oligodendrocyte cluster 9 versus cluster 2. i, Volcano plot for top DE genes of oligodendrocyte cluster 9 in PS19-E4-S/S versus PS19-E4 mice at 10 months of age. j, Representative images of Kirrel3+ Olig2+ oligodendrocytes in the hippocampus of 10-month-old PS19-E4 and PS19-E4-S/S mice at 10 months of age. Scale bars are 25 µm. k, Quantification of the number of Kirrel3+ Olig2+ oligodendrocytes (per mm2) within the dentate gyrus of hippocampus in 10-month-old PS19-E4 (n = 10) and PS19-E4-S/S (n = 10) mice at 10 months of age. In a–f, P-values are based on a two-sided hypergeometric test and are adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Gene ratio represents the proportion of genes in the respective gene set that are deemed to be differentially expressed using the two-sided Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test as implemented in the FindMarkers function in Seurat. In h,i, horizonal dashed line indicates p-value = 0.05 and vertical dashed lines indicate log2 fold change = 0.4. All error bars represent s.e.m. Difference between groups in k was determined by unpaired, two-sided Welch’s t-test. DE, differentially expressed; NS, nonsignificant; FC, fold change. For details of the analyses, see Methods.

The oligodendrocyte cluster 9 had lower odds of containing cells from PS19-E4-S/S and PS19-E4-R/S mice than from PS19-E4 mice (Fig. 6c,d, and Supplementary Table 1). Further analyses comparing oligodendrocyte cluster 9 versus cluster 2 revealed enrichment of DE genes and KEGG pathways related to neurodegeneration, including AD (Fig. 6g and Supplementary Table 1), suggesting that cells in cluster 9 are disease-associated oligodendrocytes (DAOs). Some DE genes recently identified as markers of DAOs in AD mouse models61 were also upregulated in cluster 9 versus cluster 2, such as those mediating the inflammatory process (H2-D1, Il33 and C4b) (Extended Data Fig. 7g). Additionally, the DAO cluster 9 had many significantly upregulated genes uniquely identified in the current study, including Kirrel3, Neat1, Apod, Dgki, Fmn1, Pex5l, Sik3 and Grik2 (Extended Data Fig. 7h). Notably, many of these highly upregulated DAO genes unique to cluster 9 were markedly downregulated in PS19-E4-S/S mice versus PS19-E4 mice (Extended Data Fig. 7h,i). These data indicate not only that the DAO cluster 9 was diminished by the APOE4-R136S mutation but also that the R136S mutation markedly reverses the distinct transcriptomic profile of the DAOs. Using Kirrel3 as a marker, immunofluorescent staining confirmed a significant decrease in the DAO cluster 9 in the hippocampus of PS19-E4-S/S mice versus PS19-E4 mice (Extended Data Fig. 7j,k).

LOR estimates from another GLMM to assess associations with histopathology (GLMM_histopathology) uncovered that the proportion of cells in excitatory neuron clusters 1, 6, 7 and 28 exhibited significant positive associations with hippocampal volume and negative associations with the coverage areas of p-Tau and gliosis (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Table 2). Conversely, the proportion of DAOs in oligodendrocyte cluster 9 had significant negative association with hippocampal volume and positive association with the coverage areas of p-Tau and gliosis (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Table 2). Thus, the APOE4-R136S mutation promoted the survival of excitatory neuronal subpopulations (clusters 1, 6, 7 and 28) and the elimination of DAO subpopulation (cluster 9).

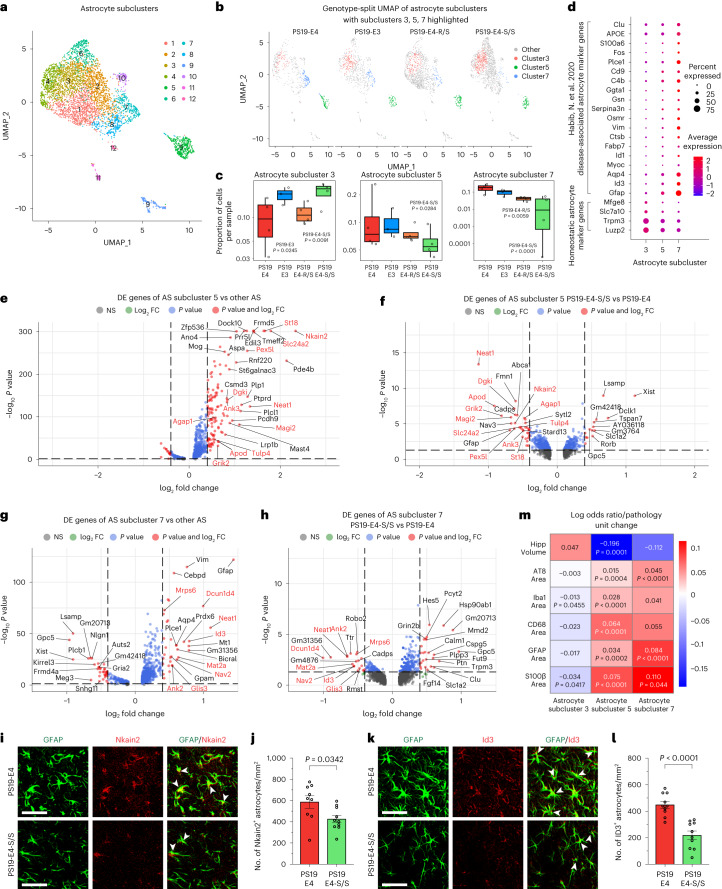

E4-S/S increases disease-protective and decreases disease-associated astrocytes

Based on our observation that even E4-R/S significantly reduces gliosis (Fig. 5 and Extended Data Fig. 5), we further dissected the effects of the APOE4-R136S mutation on subtypes of astrocytes and microglia. Subclustering of astrocytes (clusters 13 and 36 in Fig. 6a) produced 12 astrocyte subpopulations (Fig. 7a). LOR estimates from a GLMM_AM showed that astrocyte subcluster 3 was enriched in PS19-E3 and PS19-E4-S/S mice, but not in PS19-E4-R/S mice, compared to PS19-E4 mice (Fig. 7b,c and Supplementary Table 3). LOR estimates also revealed that astrocyte subclusters 5 and 7 had lower odds of containing cells from PS19-E4-S/S mice than from PS19-E4 mice (Fig. 7b,c and Supplementary Table 3). In fact, subcluster 7 was almost completely eliminated in PS19-E4-S/S mice (Fig. 7b). PS19-E4-R/S mice also had a significant decrease in LOR of astrocyte subcluster 7, although to a lesser extent than PS19-E4-S/S mice (Fig. 7b,c). All of these three astrocyte subclusters (3, 5 and 7) expressed high levels of APOE (Extended Data Fig. 8a). DE gene analyses comparing each of these subclusters to all other astrocyte subclusters identified astrocyte subcluster 3 as homeostatic astrocytes and astrocyte subclusters 5 and 7 as disease-associated astrocytes (DAAs), with upregulation of Gfap, Aqp4, Ctsb, Vim, Serpina3a, C4b and Cd9 expression (Fig. 7d and Supplementary Table 3), similar to those reported previously62. Additionally, astrocyte subclusters 5 and 7 also had many highly upregulated DE genes uniquely identified in the current study for subcluster 5 (Neat1, Pex5l1, Nkain2, Dgki, Apod and Ank3) and subcluster 7 (Neat1, Ank3, Mat2a, Nav2, Glis3 and Mrps6) (Fig. 7e,g and Supplementary Table 3), as compared to other astrocyte subclusters. Many of these highly upregulated DE genes in DAA subclusters 5 and 7 were markedly downregulated in PS19-E4-S/S mice versus PS19-E4 mice (Fig. 7f,h and Supplementary Table 3). Using Nkain2 as a marker for DAA subcluster 5 and Id3 as a marker for DAA subcluster 7, immunofluorescent staining confirmed a significant decrease in both DAA clusters in the hippocampus of PS19-E4-S/S mice versus PS19-E4 mice (Fig. 7i–l).

Fig. 7. The APOE4-R136S mutation increases disease-protective and decreases disease-associated astrocyte subpopulations.

a, UMAP projection of 12 astrocyte subclusters after subclustering hippocampal cell clusters 13 and 36 (Fig. 6a) from 10-month-old mice with different APOE genotypes. b, UMAP projection highlighting astrocyte subclusters 3, 5 and 7 for each genotype group (PS19-E4, n = 4; PS19-E3, n = 3; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 4; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 4; n = mice). c, Box plot of the proportion of cells from each sample in astrocyte subclusters 3, 5 and 7 in PS19-E4 (n = 4), PS19-E3 (n = 3), PS19-E4-R/S (n = 4), and PS19-E4-S/S (n = 4) mice. The lower, middle and upper hinges of the box plots correspond to the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles, respectively (see Fig. 6d for details). The LORs are the mean ± s.e.m. estimates of LOR for these clusters, which represents the change in the log odds of cells per sample from PS19-E3, PS19-E4-R/S or PS19-E4-S/S mice belonging to the respective clusters compared to the log odds of cells per sample from PS19-E4 mice. LOR versus PS19-E4 for subcluster 3: PS19-E3, 0.67 ± 0.30; PS19-E4-S/S, 0.71 ± 0.27; subcluster 5: PS19-E4-S/S, −0.74 ± 0.34; subcluster 7: PS19-E4-R/S, −1.57 ± 0.57; PS19-E4-S/S, −2.75 ± 0.62. d, Dot plot of normalized average expression of selected homeostatic and DAA marker genes for astrocyte subclusters 3, 5 and 7. e, Volcano plot for top 30 DE genes of astrocyte subcluster 5 versus other astrocyte subclusters. f, Volcano plot for top 30 DE genes of astrocyte subcluster 5 in PS19-E4-S/S versus PS19-E4 mice. g, Volcano plot for top 30 DE genes of astrocyte subcluster 7 versus other astrocyte subclusters. h, Volcano plot for top 30 DE genes of astrocyte subcluster 7 in PS19-E4-S/S versus PS19-E4 mice. i, Representative images of Nkain2+GFAP+ astrocytes in the hippocampus of 10-month-old PS19-E4 (n = 9) and PS19-E4-S/S (n = 10) mice. j, Quantification of the number of Nkain2+GFAP+ cells (per mm2) within the molecular layer of hippocampus. k, Representative images of Id3+GFAP+ astrocytes in the hippocampus of 10-month-old PS19-E4 (n = 10) and PS19-E4-S/S (n = 10) mice. l, Quantification of the number of Id3+GFAP+ cells (per mm2) within the molecular layer of hippocampus. m, Heat map plot of LOR per unit change in each pathological measurement for astrocyte subclusters 3, 5 and 7. P values in c are from fits to a GLMM_AM, and P values in m are from fits to a GLMM_histopathology; the associated tests are two-sided. In e–h, horizonal dashed line indicates P = 0.05, and vertical dashed lines indicate log2 fold change = 0.4. The unadjusted P values and log2 fold change values used were generated from the gene set enrichment analysis using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test as implemented in the FindMarkers function of the Seurat package. Gene names highlighted in red text indicate that they are selected marker genes for DAAs. Scale bars in i and k, 50 µm. All error bars represent s.e.m. Differences between groups in j and l were determined by unpaired, two-sided Welch’s t-test. AS, astrocyte; NS, not significant; FC, fold change.

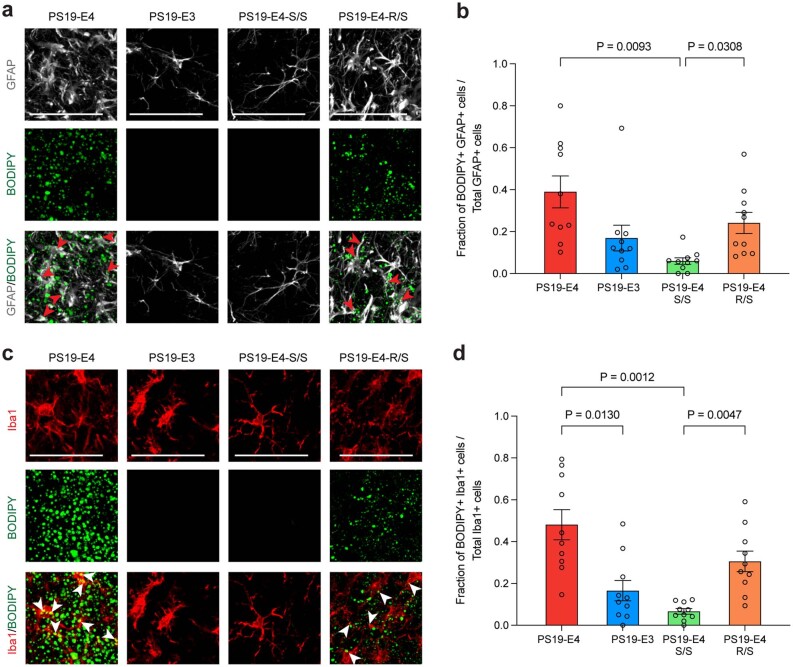

DE pathway analyses supported the notion that subcluster 3 comprised homeostatic astrocytes and subclusters 5 and 7 comprised DAAs (Extended Data Fig. 8b–d and Supplementary Table 3). Interestingly, DAA subcluster 7 had enrichment of lipid and atherosclerosis pathway genes (Extended Data Fig. 8d and Supplementary Table 3), and GFAP/BODIPY double staining revealed neutral lipid accumulation in astrocytes in PS19-E4 mice (Extended Data Fig. 9a,b). Strikingly, the R136S mutation eliminated neutral lipid accumulation in astrocytes in PS19-E4-S/S mice (Extended Data Fig. 9a,b), suggesting that the R136S mutation protects against APOE4-induced dysregulation of this process in astrocytes. Additionally, astrocytes in PS19-E4 mice had enlarged Lamp1+ lysosomes as compared to those in PS19-E3 mice, and the APOE4-R136S mutation reduced lysosome size to levels similar to that of the PS19-E3 mice (Supplementary Fig. 8a,b).

Extended Data Fig. 9. The R136S mutation reduces APOE4-induced neutral lipid accumulation in astrocytes and microglia in tauopathy mice.

a, Representative images of neutral lipid visualized with BODIPY staining in GFAP+ astrocytes in the dentate gyrus of hippocampus in PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S, and PS19-E4-R/S mice at 10 months of age (example overlap shown in red arrows). b, Quantification of the fraction of BODIPY+ GFAP+ cells per total GFAP+ cells in the dentate gyrus of hippocampus in PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S, and PS19-E4-R/S mice at 10 months of age. c, Representative images of neutral lipid visualized with BODIPY staining in Iba1+ microglia in the dentate gyrus of hippocampus in PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S, and PS19-E4-R/S mice at 10 months of age (example overlap shown in white arrows). d, Quantification of the fraction of BODIPY+ Iba1+ cells per total Iba1+ cells in the dentate gyrus of hippocampus in PS19-E4, PS19-E3, PS19-E4-S/S, and PS19-E4-R/S mice at 10 months of age. In a and c, scale bars are 50 µm. In b and d, PS19-E4, n = 10; PS19-E3, n = 10; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 10; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 10; n=mice. In b,d, data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. and differences between groups were determined by Welch’s ANOVA followed with Dunnett T3 multiple comparison test; comparisons of p ≤ 0.05 were labeled on graph. DE, differentially expressed; AS, astrocyte; MG, microglia. For details of the analyses, see Methods.

The enrichment of cells in the homeostatic astrocyte subcluster 3 was positively associated with hippocampal volume and negatively associated with the coverage areas of p-Tau and gliosis (Fig. 7m and Supplementary Table 4), as determined by LOR estimates from GLMM_histopathology. Likewise, the LOR estimates also revealed that enrichments of DAA subclusters 5 and 7 were negatively associated with hippocampal volume and positively associated with the coverage areas of p-Tau and gliosis (Fig. 7m and Supplementary Table 4). Together, these findings illustrate that E4-S/S increases disease-protective homeostatic astrocytes (subcluster 3) and both E4-S/S and E4-R/S eliminate DAAs (subclusters 5 and 7) in the hippocampus of the tauopathy mice, with E4-S/S having a greater effect than E4-R/S.

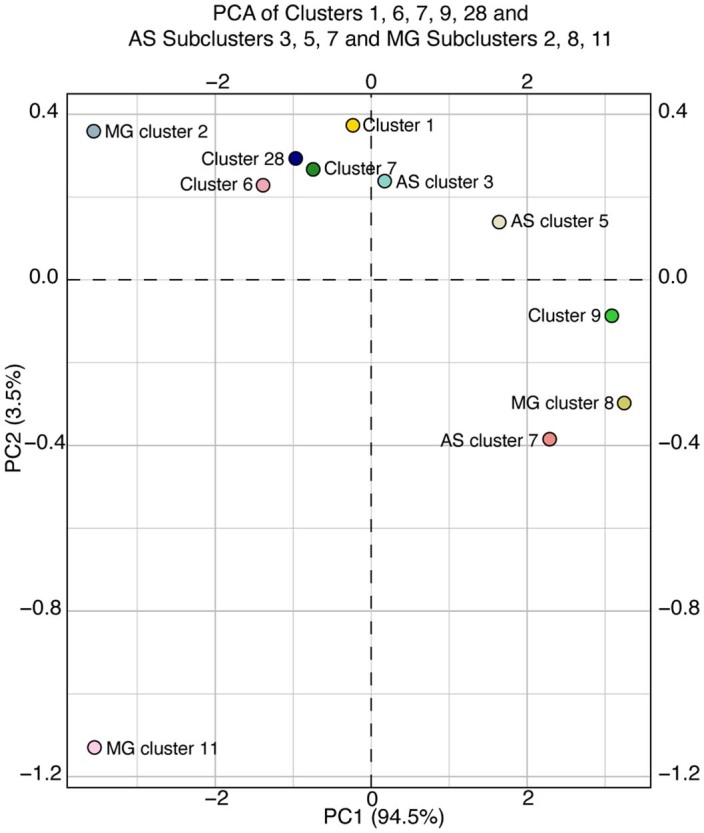

To further assess the relationship between the disease-protective and disease-associated astrocyte subpopulations, we applied principal component analysis (PCA) clustering of neuronal clusters 1, 6, 7 and 28 and oligodendrocyte cluster 9 together with astrocyte subclusters 3, 5 and 7 against all measured pathologies. Such PCA analysis revealed that the disease-protective astrocyte subcluster 3 had a similar contribution to the measured pathologies as the four disease-protective neuronal clusters (1, 6, 7 and 28) (Extended Data Fig. 10). Likewise, DAA subcluster 7 had a similar contribution to the measured pathologies as the DAOs (cluster 9) (Extended Data Fig. 10). These findings support the notion that APOE4-R136S leads to a significant increase in the disease-protective homeostatic astrocyte subpopulation, likely contributing to the enrichment of neuronal clusters 1, 6, 7 and 28, as well as to a significant reduction in the DAA subpopulation, likely contributing to the elimination of the DAOs.

Extended Data Fig. 10. PCA clustering of selected hippocampal cell clusters as well as astrocyte and microglia subclusters against all measured pathologies.

Principal component analysis plot for hippocampal clusters 1, 6, 7, 9, 28, astrocyte subclusters 3, 5, 7, and microglia subclusters 2, 8, 11 against all measured pathologies (hippocampal volume and coverage areas of AT8, Iba1, CD68, GFAP, and S100β). PC1 and PC2 showed the overall relationship between clusters based on similarity of the estimated log odds ratio per unit change in six pathologies per cluster/subcluster. AS, astrocyte; MG, microglia. For details of the analyses, see Methods.

E4-S/S increases disease-protective and decreases disease-associated microglia

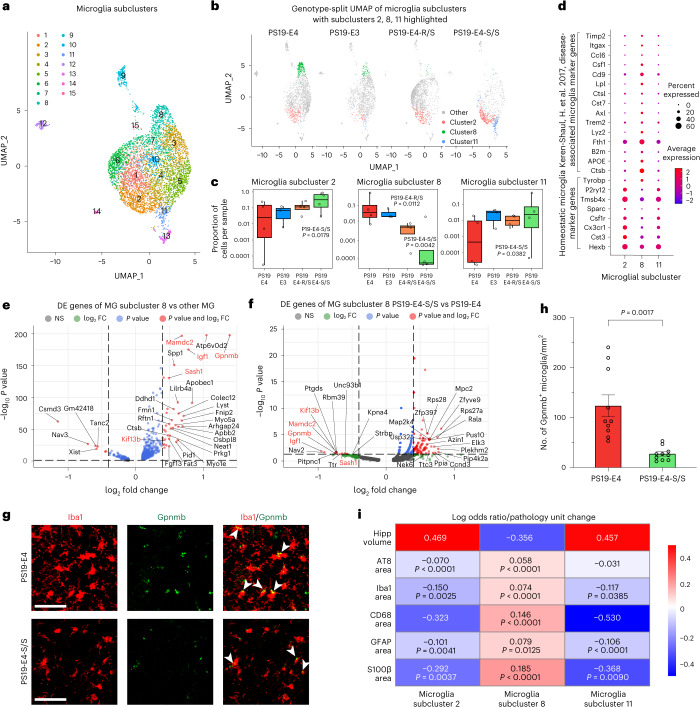

We also subclustered microglia (clusters 17 and 19 in Fig. 6a) and identified 15 microglial subclusters (Fig. 8a). LOR estimates from GLMM_AM revealed that microglia subclusters 2 and 11 were likely to contain more cells from PS19-E4-S/S mice than from PS19-E4 mice, whereas microglia subcluster 8 was likely to contain fewer cells from PS19-E4-S/S mice than from PS19-E4 mice (Fig. 8b,c and Supplementary Table 5). PS19-E4-R/S mice also had a significant decrease in microglia subcluster 8, although to a lesser extent than PS19-E4-S/S mice (Fig. 8b,c and Supplementary Table 5). Microglia subcluster 8 expressed high levels of APOE, whereas microglia subclusters 2 and 11 expressed relatively low levels of APOE (Extended Data Fig. 8e). DE gene analyses comparing each of these microglia subclusters with all other microglia subclusters identified microglia subclusters 2 and 11 as homeostatic microglia and microglia subcluster 8 as disease-associated microglia (DAMs) (Fig. 8d and Supplementary Table 5), with downregulation of homeostatic microglial genes and upregulation of DAM genes, similar to those reported previously63. Additionally, DAM subcluster 8 had many highly upregulated DE genes uniquely identified in the current study, including Igf1, Gpnmb, Mamdc2, Kif13 and Sash1 (Fig. 8e and Supplementary Table 5), as compared to other microglia subclusters. Strikingly, these highly upregulated DE genes in the DAM subcluster 8 were heavily downregulated in PS19-E4-S/S mice versus PS19-E4 mice (Fig. 8f and Supplementary Table 5). Using Gpnmb as a marker for DAM cluster 8, immunofluorescent staining confirmed a significant decrease in this DAM cluster in the hippocampus of PS19-E4-S/S mice versus PS19-E4 mice (Fig. 8g,h).

Fig. 8. The APOE4-R136S mutation increases disease-protective and decreases disease-associated microglial subpopulations.

a, UMAP projection of 15 microglia subclusters after subclustering hippocampal cell clusters 17 and 19 (Fig. 6a) from 10-month-old mice with different APOE genotypes. b, UMAP projection highlighting microglia subclusters 2, 8 and 11 for each mouse genotype group (PS19-E4, n = 4; PS19-E3, n = 3; PS19-E4-S/S, n = 4; PS19-E4-R/S, n = 4; n = mice). c, Box plot of the proportion of cells from each sample in microglia subclusters 2, 8, and 11 in PS19-E4 (n = 4), PS19-E3 (n = 3), PS19-E4-R/S (n = 4), and PS19-E4-S/S (n = 4) mice. The lower, middle and upper hinges of the box plots correspond to the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles, respectively (see Fig. 6d for details). The LORs are the mean ± s.e.m. estimates of LOR for these clusters, which represents the change in the log odds of cells per sample from PS19-E3, PS19-E4-R/S or PS19-E4-S/S mice belonging to the respective clusters compared to the log odds of cells per sample from PS19-E4 mice. LOR versus PS19-E4 for subcluster 2: PS19-E4-S/S, 3.02 ± 1.28; subcluster 8: PS19-E4-R/S, −2.58 ± 1.02; PS19-E4-S/S, −3.36 ± 1.17; subcluster 11: 2.69 ± 1.33. d, Dot plot of normalized average expression of selected homeostatic and DAM marker genes for microglia subclusters 2, 8 and 11. e, Volcano plot for top 30 DE genes of microglia subcluster 8 versus other microglia subclusters. f, Volcano plot for top 30 DE genes of microglia subcluster 8 in PS19-E4-S/S versus PS19-E4 mice. g, Representative images of Gpnmb+Iba1+ microglia in the hippocampus of 10-month-old PS19-E4 (n = 10) and PS19-E4-S/S (n = 10) mice. Scale bars, 50 µm. h, Quantification of the number of Gpnmb+Iba1+ cells (per mm2) within the DG of hippocampus. Difference between groups in h was determined by unpaired, two-sided Welch’s t-test. i, Heat map plot of LOR per unit change in each pathological measurement for microglia subclusters 2, 8 and 11. P values in c are from fits to a GLMM_AM, and P values in i are from fits to a GLMM_histopathology; the associated tests are two-sided. In e,f, horizonal dashed line indicates P = 0.05, and vertical dashed lines indicate log2 fold change = 0.4. The unadjusted P values and log2 fold change values used were generated from the gene set enrichment analysis using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test as implemented in the FindMarkers function of the Seurat package. Gene names highlighted in red text indicate that they are selected marker genes for DAMs. All error bars represent s.e.m. AS, astrocyte; FC, fold change; MG, microglia; NS, not significant.

Furthermore, DE pathway analysis revealed enrichment of KEGG pathways related to MAPK signaling, cAMP signaling and synaptic function in microglia subclusters 2 and 11 (Extended Data Fig. 8f,h, and Supplementary Table 5), supporting their homeostatic function. Conversely, DAM subcluster 8 had enrichment in KEGG pathways related to lysosome, autophagy and various diseases (Extended Data Fig. 8g and Supplementary Table 5), supporting its disease association. We also observed enrichment of lipid and atherosclerosis pathway genes in DAM subcluster 8 (Extended Data Fig. 8g and Supplementary Table 5). Iba1/BODIPY double staining confirmed neutral lipid accumulation in microglia in PS19-E4 mice but not PS19-E3 mice (Extended Data Fig. 9c,d). Notably, the R136S mutation eliminated neutral lipid accumulation in microglia in PS19-E4-S/S mice (Extended Data Fig. 9c,d), suggesting that the R136S mutation protects against APOE4-induced dysregulation of lipid accumulation in microglia. No significant difference was observed in Lamp1+ lysosomal size in microglia with different APOE genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 8c,d).

The LOR estimates from GLMM_histopathology revealed that the proportion of cells in microglia subclusters 2 and 11 exhibited positive associations with hippocampal volume and negative associations with the coverage areas of p-Tau and gliosis, whereas microglia subcluster 8 had a negative association with hippocampal volume and a significant positive association with the coverage areas of p-Tau and gliosis (Fig. 8i and Supplementary Table 6). Together, these findings indicate that the APOE4-R136S mutation increases disease-protective homeostatic microglia (subclusters 2 and 11) and eliminates DAMs (subcluster 8), with E4-S/S having a greater effect than E4-R/S.

Furthermore, PCA analysis revealed that the disease-protective microglia subcluster 2 had a similar contribution to the measured pathologies as the four disease-protective neuronal clusters (1, 6, 7 and 28) (Extended Data Fig. 10). Likewise, DAM subcluster 8 had a similar contribution to the measured pathologies as the DAOs (cluster 9) (Extended Data Fig. 10). These findings again support the notion that APOE4-R136S leads to a significant increase in the disease-protective homeostatic microglia subpopulation, likely contributing to the enrichment of neuronal clusters 1, 6, 7 and 28, as well as to a significant reduction in the DAM subpopulation, likely contributing to the elimination of the DAOs.

Discussion

The protection conferred by APOE3-R136S against EOAD caused by the PSEN1-E280A mutation is a milestone discovery36. It emphasizes the key roles of APOE variants in AD pathogenesis and/or protection. Our approach of studying APOE4-R136S allows us to investigate if and how this mutation may also be protective against AD pathologies promoted by APOE4 (Supplementary Fig. 9). Our data show that homozygous R136S mutation fully protects against APOE4-driven Tau pathology, neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in a tauopathy mouse model (Supplementary Fig. 9). We also demonstrate the protection of the APOE4-R136S mutation against Tau uptake and p-Tau accumulation in an AD-relevant context using hiPSC-derived neurons (Supplementary Fig. 9).