Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the antimicrobial efficacy of polyhexamethylene hydrochloride guanidine (PHMGH) compared to chlorhexidine digluconate (CLX) for use as an oral antiseptic during dental procedures in wild cats. This research is crucial due to limited information on the diversity of oral microorganisms in wild cats and the detrimental local and systemic effects of oral diseases, which highlights the importance of improving prevention and treatment strategies. Samples were collected from the oral cavities of four Puma concolor, one Panthera onca, and one Panthera leo, and the number of colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) was counted and semi-automatically identified. The antimicrobial susceptibility profile of bacterial isolates was determined using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC), and time-kill kinetics of PHMGH and CLX. A total of 16 bacterial isolates were identified, consisting of six Gram-positive and 10 Gram-negative. PHMGH displayed MIC and MBC from 0.24 to 125.00 μg/mL, lower than those of CLX against three isolates. Time-kill kinetics showed that PHMGH reduced the microbial load by over 90% for all microorganisms within 30 min, whereas CLX did not. Only two Gram-positive isolates exposed to the polymer showed incomplete elimination after 60 min of contact. The results could aid in the development of effective prevention and treatment strategies for oral diseases in large felids. PHMGH showed promising potential at low concentrations and short contact times compared to the commercial product CLX, making it a possible active ingredient in oral antiseptic products for veterinary use in the future.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-023-01107-x.

Keywords: Wildlife medicine, Microbiology, System stomatognathic, Synthetic polymer, Antiseptic

Introduction

The oral health of wild cats is jeopardized by a plethora of diseases caused by diverse pathogens, which can result in dire consequences, including extinction [1]. Despite several studies investigating the oral anatomy and pathologies of these animals, the limited knowledge regarding their oral microbiota poses a challenge for the efficacious prevention and treatment of these diseases [2]. In addition to the dearth of information on the microbiota, malnutrition, stress, inbreeding, and anthropogenic activities exacerbate the risk of oral diseases, thus endangering the survival of wild cats [1].

It is worth noting that researchers often rely on domestic cats as a reference, despite their distinct oral health issues, such as periodontal disease, chronic gingivostomatitis complex, and odontoclastic resorptive lesions [3]. However, recent studies have highlighted differences in the bacterial composition of healthy and diseased oral cavities in both domestic and wild cats [4]. Furthermore, the inappropriate use of several antiseptic products for controlling oral microorganisms in animals can lead to bacterial resistance, and each product has its own therapeutic responses and side effects, making them less effective and affordable; therefore, there is a need for research into novel antiseptic products in veterinary dentistry [5, 6].

One such product with potential is the synthetic polymer hydrochloride polyhexamethylene guanidine (PHMGH), which has been scientifically demonstrated to have in vitro antibacterial and antifungal effects and low toxicity. However, there is limited data regarding its use in veterinary dentistry, particularly with respect to wild cats [7–9].

Given the severe local and systemic consequences of oral diseases in wild cats, this study aims to evaluate the antimicrobial susceptibility profile of bacterial isolates from their oral cavities against PHMGH and compare it to chlorhexidine digluconate (CLX). This will provide valuable insights into the potential use of PHMGH as a safe and effective alternative antiseptic product for treating oral diseases in wild cats.

Material and methods

Ethical considerations

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use (CEUA) of the University of Franca (UNIFRAN), process number 9615071020.

Animal selection

Six wild cats were used in this study, including four Puma concolor (two females and two males), one Panthera onca (male), and one Panthera leo (male), all of them adult, healthy, castrated, and intact, weighing between 45 and 180 kg, and aged between 2 and 18 years old. These animals were sourced from the Dr. Fabio Barreto Municipal Park (Ribeirao Preto, SP, Brazil), which follows all standard licensing conditions for the care and maintenance of captive wild cats (IN 07/2015).

All the wild cats included in the study had been housed in captivity for over a year and were kept in enclosures equipped with environmental enrichment. They were provided with a daily diet consisting of bones, beef, and chicken in the evening, and had unrestricted access to water throughout the day. None of the animals had undergone prior dental treatment, and their health was ensured by laboratory exams conducted by the research team immediately after material collection for the present study.

Experimental design

The animals were anesthetized following a 12-h fast. The pharmacological restraint used was dissociative (pre-anesthetic medication with midazolam followed by a combination of ketamine, dexmedetomidine, and butorphanol administered intramuscularly via blowpipe darts), with the doses calculated using interspecific allometric extrapolation [10, 11]. We then performed physical and complementary exams, weighed the animals, and collected biological materials. The felids were monitored during all procedures and throughout the anesthesia recovery period until fully rehabilitated.

Oral microbiological samples were obtained by the same veterinarian dentist using a sterile swab (Olen® 27-28 Model K41-0102, China) inserted into the animals’ oral cavity, followed by gentle rubbing of the gums, mucosa, soft and hard palate, tongue, and teeth. The samples were immediately placed in Stuart medium, individually identified, and sent to the Laboratory of Applied Microbiology Research at the University of Franca (LaPeMA), where they were processed using conventional techniques [12].

Microbiological analysis

The swabs were immersed in test tubes containing 3mL of 0.9% saline solution (Eurofarma Laboratório S.A., Ribeirão Preto—SP) and incubated in aerobic conditions at 36.5°C overnight. Afterwards, a 100 μL aliquot was transferred from each tube to a new tube containing 0.9 mL of saline solution, resulting in an initial 10-fold dilution. Three serial dilutions were performed in the scales of 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, starting from the undiluted original sample (100) [12].

For every dilution achieved, 100 μL of the saline solution was carefully placed onto Petri dishes containing Brain and Heart Infusion agar (BHI, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), which served as the growth medium. The allocated aliquot of the sample on each plate was evenly spread using the Drigalski technique. Subsequently, the plates were placed in an inverted position and incubated at a temperature of 36.5°C for a duration of 24 h. The uniformity of colony growth within the three different dilutions was assessed. To quantify the microbial population, the number of colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) was determined. The CFU counts were then converted to CFU/mL by utilizing the formula: number of counted colonies divided by the dilution factor of the sample, multiplied by the volume of the sample that was inoculated.

Plates with the highest diversity of colonies were selected based on morphological characterization. A portion of the chosen morphotype was transferred and seeded using the exhaustion technique on BHI agar culture medium. The plates were identified according to the description of the chosen morphotype and incubated under the same conditions as before until a completely pure colony was obtained.

After the colonies were purified, the isolates were transferred using aseptic technique to Petri dishes containing selective MacConkey agar medium (Kasvi, São José do Pinhais, Brazil) to promote the growth of Gram-negative bacteria. The plates were inverted and incubated at 36.5°C for 24 h, and bacterial growth was evaluated. Additionally, the Gram staining technique was performed to confirm the purity and classify the bacteria based on their cell wall characteristics.

The analysis was performed semi-automatically using the BBL Crystal Enteric/Nonfermenter and BBL Crystal Gram-Positive Kits (BD Life Sciences, East Rutherford, NJ, USA) for Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, as previously described. The reading was performed using the BBL Crystal Light Box (BD Life Sciences, East Rutherford, NJ, USA) and the BD BBL Crystal MIND software, following the specifications of each kit.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The MIC technique was performed in triplicate, as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [13], using resazurin (0.02%, Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, San Luis, Missouri, USA) as a bacterial growth indicator [14]. To validate the technique, sterility controls were carried out for the BHI broth, PHMGH mother solution, and solvent control (sterilized distilled water).

The tested concentrations for PHMGH ranged from 0.12 to 2000 μg/mL, which is equivalent to 0.000012 to 0.2%. The positive control, CLX, was tested at concentrations ranging from 0.12 to 59 μg/mL, or 0.000012 to 0.0059%, in accordance with the methodology recommended by CLSI [13].

To obtain the inoculum, bacterial isolates were subcultured on BHI agar and incubated under aerobic conditions at 36.5°C for 24 h. Afterward, bacterial colonies were transferred to a test tube containing 3 mL of 0.9% saline using a sterilized inoculation loop. The suspensions were standardized to a 0.5 McFarland scale (1.5 × 108 CFU/mL). Next, dilutions of each bacterial suspension were prepared by transferring 500 μL to a tube containing 4.5 mL of 0.9% saline, resulting in a concentration of 1.5 × 107 CFU/mL. From this tube, 2 mL was transferred to another containing 10 mL of BHI broth, resulting in a concentration of 2.5 × 106 CFU/mL. When 20 μL was added to the microplates, the final volume was 100 μL, and the concentration was 5 × 105 CFU/mL per well.

After preparing the PHMGH, positive control, and inoculum, the microdilution method was performed in broth to determine the polymer’s MIC against bacterial isolates. Sterilized 96-well microplates were used for each bacterial isolate and the polymer. Initially, 50 μL of BHI broth was added to all wells to allow for the serial dilution of the PHMGH solution. Then, 50 μL of the PHMGH solution was added to the first well, and 50 μL from the first well was transferred to the second well, and so on, until all dilutions were completed. After dilution, a complementary volume of 30 μL of BHI broth was added, and finally, 20 μL of each bacterial suspension (inoculum) was added to all wells, resulting in a final volume of 100 μL.

For the evaluation of CLX, 59 μL of BHI broth was added to wells of the microplate designated for the positive control. Then, 59 μL of the positive control’s mother solution was added to the first well, and 59 μL from the first well was transferred to the second well, and so on, until all dilutions were completed. After dilution, a complementary volume of 21 μL of BHI broth was added, and 20 μL of the bacterial isolates’ inoculum was added to all wells, resulting in a final volume of 100 μL in each well.

After the incubation period of the microplates, each well was added with 30 μL of resazurin to evaluate the results. The microplates were then reincubated for 30 min to visualize the color changes, where bacterial growth was characterized by a pink color and the absence of growth was characterized by blue [14].

Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)

The MBC technique was used to determine the lowest concentration of the PMHG that exhibits bactericidal action, indicated by the absence of colonies on BHI agar, or bacteriostatic activity, indicated by bacterial growth in the medium.

The MBC technique was performed before adding resazurin to the MIC. Therefore, 10 μL from each well of the microplate was transferred to BHI agar, and the plates were incubated for 24 h at 36.5°C. After incubation, the result was evaluated by the absence or growth of colonies in each inoculated aliquot. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed in μg/mL.

Time kill-kinetics

The aim of this assay was to determine the time of bacterial isolates death [15, 16], in response to PHMGH concentrations of 2000 μg/mL (0.2%) and CLX concentrations of 1200 μg/mL (0.12%). The assay was carried out with modifications following the methodology described by CLSI [17].

To prepare each bacterial suspension, colonies that had grown on BHI agar for 24 h were inoculated in tubes containing 5 mL of 0.9% saline solution. The turbidity was compared to the McFarland scale at a concentration of 3 × 109 CFU/mL. From this suspension, 500 μL was transferred to a tube containing 4.5 mL of 0.9% saline (3 × 108 CFU/mL). Then, 900 μL of the 108 inoculum was distributed into empty tubes for the addition of 100 μL of each tested solution. The tubes were identified according to each bacterial isolate.

After adding the sample, 100 μL aliquots were taken at time intervals of 0 s, 30 s, 1 minute, 5 min, 10 min, 30 min, and 60 min. These aliquots were then spread on BHI agar plates with a Drigalski loop. The plates were subsequently incubated at 36.5°C for 24 h, and surviving colonies were counted on each plate at different exposure times and concentrations of PHMGH and CLX. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed in Log10 CFU/mL and percentage reduction.

Results

Microbiological analysis

Bacterial growth was observed in all six oral cavity samples collected from the wild cats. The total microbial counts for the study specimens at standardized dilutions are shown in Table 1. A total of 16 bacterial isolates were identified, including six Gram-positive (three cocci and three bacilli) and 10 Gram-negative (nine bacilli and one coccobacillus) isolates (Table 2).

Table 1.

Colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) of samples collected from the oral cavities of Panthera leo, Panthera onca, and Puma concolor kept in captivity

| Samples | Species | Total microorganisms | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Panthera onca | 232.000 CFU/mL | 10−1 |

| 2 | Panthera leo | 8.760.000 CFU/mL | 10−3 |

| 3 | Puma concolor | 1.945.000 CFU/mL | 10−1 |

| 4 | Puma concolor | 1.764.000 CFU/mL | 10−1 |

| 5 | Puma concolor | 2.111.000 CFU/mL | 10−1 |

| 6 | Puma concolor | 1.995.000 CFU/mL | 10−1 |

Table 2.

Identification (Gram-positive or negative) and frequency of isolates of bacteria isolated from the oral cavity of large felines of the species Panthera leo, Panthera onca, and Puma concolor kept in captivity

| Identification | Number of isolates | Total isolates in percentage | Panthera leo | Panthera onca | Puma concolor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive | |||||

| Oerskovia sp. | 1 | 6.25 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Corynebacterium sp. | 1 | 6.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 1 | 6.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Enterococcus raffinosus | 1 | 6.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Leifsonia aquatica | 1 | 6.25 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Staphylococcus lentus | 1 | 6.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 6 | 37.5 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Gram-negative | |||||

| Bergeyella zoohelcum | 1 | 6.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| BGN | 2 | 12.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Providencia rustigianii | 2 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Serratia marcescens | 2 | 12.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Serratia plymuthica | 2 | 12.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | 1 | 6.25 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 10 | 62.5 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Total isolates | 16 | 100 | 6 | 2 | 8 |

Of the 16 bacterial isolates, two were identified at the species group level (Gram-negative bacilli), two at the genus level (Corynebacterium sp. and Oerskovia sp.), and 12 at the species level (Bergeyella zoohelcum, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus raffinosus, Leifsonia aquatica, Staphylococcus lentus, Serratia marcescens, Serratia plymuthica, Providencia rustigianii, and Yersinia enterocolitica).

Six genera of Gram-positive bacteria and four genera and five species of Gram-negative bacteria were identified, with six isolates from Serratia marcescens, Serratia plymuthica, and Providencia rustigianii. Eight bacterial isolates were identified from Puma concolor (four Gram-positive and four Gram-negative) with six species, two isolates from Panthera onca (Gram-negative) with two species, and six isolates from Panthera leo (two Gram-positive and four Gram-negative) with four species.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)

Table 3 presents the MIC and MBC values of oral microorganisms that were isolated from wild cats and exposed to either PHMGH or CLX.

Table 3.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC), in μg/mL, of polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride (PHMGHH—0.12 to 2000 μg/mL) and chlorhexidine digluconate (CLX—0.12 to 59 μg/mL), against bacteria isolated from the oral cavity of Puma concolor, Panthera onca, and Panthera leo kept in captivity

| Bacterial isolates | MIC/MBC (μg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|

| PHMGH | CLX | |

| Gram-positive | ||

| Corynebacterium spb | 3.91/3.91 | 0.92/0.92 |

| Enterococcus faecalisb | 125.00/125.00 | 3.69/3.69 |

| Enterococcus raffinosusb | 1.95/1.95 | 0.92/0.92 |

| Leifsonia aquaticaa | 3.91/3.91 | 1.84/1.84 |

| Oerskovia sp.a | 7.81/7.81 | 1.84/1.84 |

| Staphylococcus lentusb | 7.81/7.81 | 0.92/0.92 |

| Gram-negative | ||

| Bergeyella zoohelcumb | 0.48/0.48 | 3.69/3.69 |

| Gram-negative bacillib | 0.24/0.24 | 0.46/0.46 |

| Gram-negative bacillia | 31.25/31.25 | 0.92/0.92 |

| Providencia rustigianiib1 | 0.48/0.48 | 0.46/0.46 |

| Providencia rustigianiib2 | 0.24/0.24 | 0.92/0.92 |

| Serratia marcescensa | 62.50/62.50 | 7.38/7.38 |

| Serratia marcescensc | 7.81/7.81 | 3.69/3.69 |

| Serratia plymuthicaa | 7.81/7.81 | 1.84/1.84 |

| Serratia plymuthicac | 31.25/31.25 | 7.38/7.38 |

| Yersinia enterocoliticaa | 7.81/7.81 | 7.38/7.38 |

aMicroorganism isolated from Panthera leo

bMicroorganism isolated from Puma concolor

cMicroorganism isolated from Panthera onca

b1Microorganism isolated from individual 1 of Puma concolor

b2Microorganism isolated from individual 2 of Puma concolor

PHMGH showed lower MIC/MBC values than CLX, ranging from 0.24 to 0.48 μg/mL against bacteria Bergeyella zoohelcum, Gram-negative bacilli (isolated from Puma concolor), and Providencia rustigianii (from one of the Puma concolor individuals). For bacteria Corynebacterium sp., Enterococcus raffinosus, Leifsonia aquatica, Oerskovia sp., Providencia rustigianii (from one of the Puma concolor individuals), Staphylococcus lentus, Serratia marcescens (isolated from Panthera onca), Serratia plymuthica (isolated from Panthera leo), and Yersinia enterocolitica, the bactericidal activity of PHMGH was observed at concentrations ranging from 0.48 to 7.81 μg/mL.

At higher concentrations, PHMGH exhibited bactericidal activity against Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia marcescens (isolated from Panthera leo), Serratia plymuthica (isolated from Panthera onca), and Gram-negative bacilli (isolated from Panthera leo), with MIC/MBC values of 125 μg/mL, 62.50 μg/mL, 31.25 μg/mL, and 31.25 μg/mL, respectively.

Time kill-kinetics

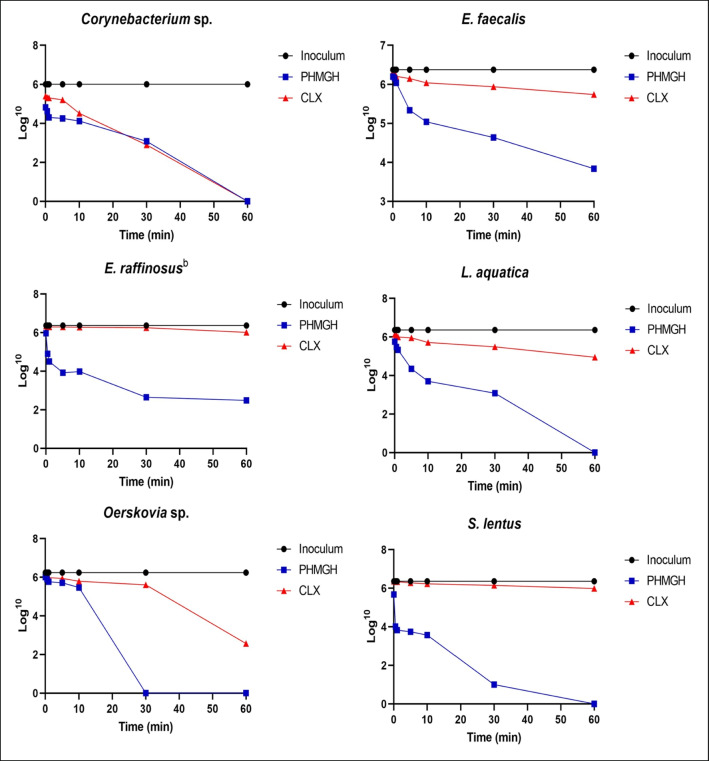

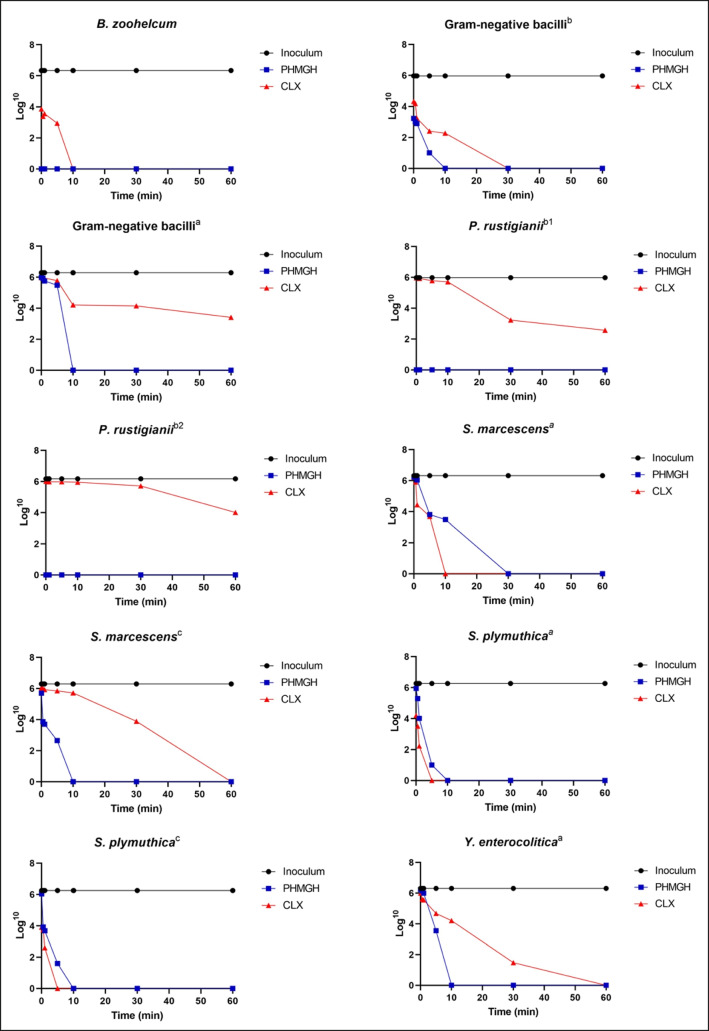

The Log10 UFC/mL values of identified bacterial isolates at different contact times with PHMGH and CLX are presented in Figs. 1 and 2. The percentage reduction values of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial load are also shown in supplementary materials.

Fig. 1.

Microbial load values (CFU/mL Log) of Gram-positive bacteria isolated from the oral cavity of large felids of the species Panthera leo, Panthera onca, and Puma concolor kept in captivity, as a function of contact time (minutes) with polyhexamethylene hydrochloride guanidine (PHMGH) and chlorhexidine digluconate (CLX) at concentrations of 2000 μg/mL (0.2%) and 1200 μg/mL (0.12%), respectively

Fig. 2.

Microbial load values (CFU/mL Log) of Gram-negative bacteria isolated from the oral cavity of large felids of the species Panthera leo, Panthera onca, and Puma concolor kept in captivity, as a function of contact time (minutes) with polyhexamethylene hydrochloride guanidine (PHMGH) and chlorhexidine digluconate (CLX) at concentrations of 2000 μg/mL (0.2%) and 1200 μg/mL (0.12%), respectively. a Microorganism isolated from Panthera leo, b Microorganism isolated from Puma concolor, c Microorganism isolated from Panthera onca, b1 Microorganism isolated from individual 1 of Puma concolor, b2 Microorganism isolated from individual 2 of Puma concolor

Among the Gram-positive bacteria, the shortest time required for PHMGH to eliminate 100% of the bacterial load was 30 min (for Oerskovia sp. and Staphylococcus lentus) and 60 min (for Corynebacterium sp. and Leifsonia aquatica).

Only two Gram-positive bacteria (Enterococcus raffinosus and Enterococcus faecalis) exposed to PHMGH did not show complete reduction of bacterial load. In contrast, five bacteria exposed to CLX (Leifsonia aquatica, Oerskovia sp., Enterococcus raffinosus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Staphylococcus lentus) did not exhibit complete reduction of bacterial load. Regarding Gram-negative bacteria, PHMGH eliminated 100% of bacterial load of all bacteria in 30 min or less. Moreover, three bacteria exposed to CLX (Gram-negative bacilli of Panthera leo and the two isolates of Providencia rustigianii) did not show complete reduction of bacterial load within 60 min of contact with the product.

Discussion

The findings of this study represent a significant advancement in the potential use of the PHMGH (synthetic polymer) as an antiseptic against oral pathogens in feline oral cavities. The predominant bacterial phyla identified in the analyzed samples were consistent with previous research investigating the oral microbiota of domestic cats [3, 4], specifically including Proteobacteria (Providencia rustigianii, Serratia marcescens, Serratia plymuthica, and Yersinia enterocolitica) and Firmicutes (Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus raffinosus, and Staphylococcus lentus).

Using both the MIC and MBC techniques, the PHMG demonstrated potent bactericidal activity against a wide range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. These results support previous reports describing the broad-spectrum action of this polymer [7, 8, 18–20]. Furthermore, studies conducted by Zhang et al. [18], Mathurin et al. [21] and Zhou et al. [22] have demonstrated that the effectiveness of guanidine-based cationic polymers varies depending on the genus of the microorganism, and our study supports this observation for PHMGH in the context of feline oral pathogens.

Our findings indicate that the PHMGH polymer displayed potent bactericidal activity against all Gram-positive bacteria tested, with the highest concentration observed for the CIM and CBM against Enterococcus faecalis. This agrees with the results of Zhou et al. [22], who investigated the susceptibility of the polymer compared to CLX against clinical human isolates. Zhang et al. [18] reported that Enterococcus faecalis is highly resistant in the oral cavity, even in the absence of other microorganisms or substrate, and is resistant to various irrigants and medications [23].

Similarly to our investigation, the study by Zhou et al. [22], which evaluated clinical human isolates, showed that PHMGH exhibited comparable or superior antimicrobial activity to CLX against various Gram-negative bacteria, especially Bergeyella zoohelcum, BGN and Providencia rustigianii. The effective antimicrobial activity of PHMGH against Gram-negative bacteria is noteworthy, as they are typically more resistant to antimicrobial agents due to the presence of an outer membrane that acts as a barrier, restricting the entry of agents into the bacterial cytosol [7, 21]. The studies conducted by Zhou et al. [22], Alfei and Schito [24], and Moshynets et al. [25] have suggested that the superior antimicrobial activity of PHMGH compared to CLX may be attributed to the presence of a flexible linear alkyl chain in the polymer. This feature enhances its ability to partition into the hydrophobic regions of the plasma membrane, disrupting the phospholipid bilayer and causing leakage of cytosolic content, ultimately leading to bacterial inactivation. Additionally, PHMGH acts on the bacterial cell membrane by inhibiting essential enzymes required for bacterial growth and germination [7, 19, 26]. Moreover, according to Allen et al. [27], there is evidence that PHMGH can bind to bacterial DNA upon entering the cell, causing damage and inactivation of the genetic material.

This study demonstrates the potential antiseptic effect of PHMGH at low concentrations and short exposure times, evidenced by its efficient reduction of microbial load compared to commercial CLX [19, 22], particularly against Gram-positive bacteria. These findings align with those reported for other bacterial strains such as Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella choleraesuis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Bacillus subtilis, highlighting the rapid onset of PHMGH-induced bacterial death [7, 8]. Notably, the potency of PHMGH may depend on the concentration used, exposure time, and bacterial inoculum size, as previously emphasized by Zhou [22]. Wei et al. [26] reported 90% antimicrobial activity of PHMGH against standard strains within 15 min of contact in an in vitro study. In the present investigation, we observed a similar reduction in bacterial load for most evaluated oral bacteria in captive wild cats within 10 min of contact with the polymer.

Our findings suggest that PHMGH has potential as an effective active ingredient in a new oral antiseptic product for use as a mouthwash during dental procedures in large felids. The polymer demonstrated excellent antimicrobial activity at low concentrations and in a short time against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, which could significantly reduce local infection and oral bleeding during the surgical period. This reduction in microbial load would lead to shorter operating times, lower anesthesia risks, reduced procedure costs, and faster oral tissue recovery [28].

In addition, a PHMGH-based oral antiseptic product could potentially reduce bacteremia caused by microorganisms and their metabolites entering lymphatic and blood vessels during dental procedures. This could help prevent the formation of immune complexes in the bloodstream, which can cause local inflammation, endothelial lysis, and functional damage to various organs, especially in elderly patients [29].

The broad-spectrum action of PHMGH combined with its rapid action could also benefit the dental team involved in the procedure by reducing the number of pathogenic microorganisms in suspension in the surgical center [28]. Furthermore, PHMGH demonstrated superior antimicrobial activity against some oral microorganisms when compared to commercial CLX, which is currently considered the “gold standard” in the prevention and treatment of oral diseases in both humans and animals. Furthermore, CLX can demonstrate side effects, including changes in dental coloration, restorations, prostheses, and tongue, supragingival calculus formation, loss of taste, burns in the soft tissue, oral sensitivity, and xerostomia when used long term [30–33]. Thus, a PHMGH-based oral antiseptic product could be a safer and more effective alternative to CLX for preventing and treating oral diseases in felids undergoing dental procedures.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the study reveals that PHMGH could serve as a potent antimicrobial agent for maintaining oral hygiene. The outcomes establish that PHMGH can deliver equivalent results to CLX, but with reduced concentrations and quicker outcomes. Hence, PHMGH appears to be a promising candidate for developing oral antiseptic products.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 58 kb)

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance code 001) and Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento Tecnológico—Brasil (CNPq)—Process number 312524/2021-8.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Highlights

• PHMGH exhibits bactericidal activity against pathogenic bacteria, showing its broad-spectrum antimicrobial potential.

• PHMGH is more effective than CLX in eliminating bacterial load, particularly among Gram-positive bacteria.

• PHMGH eliminates 100% of bacterial load in just 30 min, demonstrating its fast-acting antimicrobial potential.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Larsson MHMA, Flores AS, Fedullo JDL, Teixeira RHF, Mirandola RMS, Ito FH, Pessoa RB, Itikawa PH. Biochemical parameters of wild felids (Panthera leo and Panthera tigris altaica) kept in captivity. Semin. 2017;38(2):791–800. doi: 10.5433/1679-0359.2017v38n2p791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King LM, Wallace SC. Phylogenetics of Panthera, including Panthera atrox, based on craniodental characters. Hist Biol. 2014;26(6):827–833. doi: 10.1080/08912963.2013.861462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sturgeon A, Pinder SL, Costa MC, Weese JS. Characterization of the oral microbiota of healthy cats using next-generation sequencing. Vet J. 2014;201(2):223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weese SJ, Nichols J, Jalali M, Litster A. The oral and conjunctival microbiotas in cats with and without feline immunodeficiency virus infection. Vet Res. 2015;46(21):2–11. doi: 10.1186/s13567-014-0140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Argyraki A, Markvart M, Stavnsbjerg C, Kragh KN, Ou Y, Bjorndal L, Bjarnsholt T, Petersen PM. UV light assisted antibiotics for eradication of in vitro biofilms. Sci Rep. 2018;107(1):2411–2502. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34340-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeyakumar J, Sculean C, Eick S. Anti-biofilmactivityof oral health-care products containing chlorhexidine diguclonate and citrox. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2020;18(1):981–990. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a45437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oulé MK, Azinwi R, Bernier AM, Kablan T, Maupertuis AM, Mauler S, Nevry RK, Dembéle K, Forbes L, Diop L. Polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride-based disinfectant: a novel tool to fight meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and nosocomial infections. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57(12):1523–1528. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/003350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oulé MK, Quinn K, Dickman M, Bernier AM, Rondeau S, Moissac D, Boisvert A, Diop L. Akwaton, polyhexamethylene-guanidine hydrochloride-based sporicidal disinfectant: a novel tool to fight bacterial spores and nosocomial infections. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61(1):1421–1427. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.047514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oulé MK, Staines K, Lightly T, Roberts L, Traoré YL, Dickman M, Bernier AM, Diop L. Fungicidal activity of Akwaton and in vitro assessment of its toxic effects on animal cells. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64(1):59–66. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.079467-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freitas GC, Carregaro AB. Aplicabilidade da extrapolação alométrica em protocolos terapêuticos para animais selvagens. Cienc Rural. 2013;43(2):297–304. doi: 10.1590/S0103-84782013000200017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souza MV, Nascimento LR, Hirano LQL, Santos ALQ, Pachaly JR. Chemical restraint of jaguars Panthera onca Linnaeus, 1758 with allometrically scaled doses of tiletamine, zolazepam, detomidine, and atropine. Semin. 2018;39(4):1595–1606. doi: 10.5433/1679-0359.2018v39n4p1595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trabulsi LR, Alterthum F. Microbiologia. 4. ed. São Paulo: Atheneu; 2005. p. 718p. [Google Scholar]

- 13.CLSI (ed) (2020) Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptitibility Testing. 30th ed. CLSI supplement M100, Wayne, PA, Clinical and Laboratory Institute

- 14.Sarker SD, Nahar L, Kumarasamy Y. Microtitre plate-based antibacterial assay incorporating resazurin as an indicator of cell growth, and its application in the in vitro antibacterial screening of phytochemicals. Methods. 2007;42(4):321–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao Y, Yin H, Wang W, Pei P, Wang Y, Wang X, Jiang J, Luo SZ, Chen L. Killing Streptococcus mutans in mature biofilm with a combination of antimicrobial and antibiofilm peptides. Amino Acids. 2020;52(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00726-019-02804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moraes TS, Leandro LL, Santiago MB, Silva LO, Bianchi TC, Veneziani RCS, Ambrósio SR, Ramos SB, Bastos JK, Martins CHG. Assessment of the antibacterial, antivirulence, and action mechanism of Copaifera pubiflora oleoresin and isolated compounds against oral bacteria. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;129(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CLSI - Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Approved standard. M26-AWayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 1999. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Jiang J, Chen Y. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of polymeric guanidine and biguanidine salts. Polymer. 1999;40(22):6189–6198. doi: 10.1016/S0032-3861(98)00828-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vitt A, Sofrata A, Slizen V, Sugar SRV, Gustafsson A, Gudkova EI, Kazeko LA, Ramberg P, Buhlin K. Antimicrobial activity of polyhexamethylene guanidine phosphate in comparison to chlorhexidine using the quantitative suspension method. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2015;14(36):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12941-015-0097-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan Y, Xia Q, Xiao H. Cationic polymers with tailored structures for rendering polysaccharide-based materials antimicrobial: an overview. Polymers. 2019;11(8):1283–1299. doi: 10.3390/polym11081283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathurin YK, Koffi-Nevry R, Guéhi ST, Tano K, Oulé MK. Antimicrobial activities of polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride - based disinfectant against fungi isolated from Cocoa Beans and reference strains of bacteria. J Food Prot. 2012;75(6):1167–1171. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Z, Wei D, Lu Y. Polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride shows bactericidal advantages over chlorhexidine digluconate against ESKAPE bacteria. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2015;62(2):268–274. doi: 10.1002/bab.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beyth N, Shvero DK, Zaltsman N, Houri-Haddad Y, Abramovitz I, Davidi MP, Weiss EI. Rapid kill-novel endodontic sealer and Enterococcus faecalis. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alfei S, Schito AM. Positively charged polymers as promising devices against multidrug resistant gram-negative bacteria: a review. Polymers. 2020;12(5):1–47. doi: 10.3390/polym12051195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moshynets OV, Baranovskyi TP, Iungin OS, Kysil NP, Metelytsia LO, Pokholenko I, Potochilova VV, Potters G, Rudnieva KL, Rymar SY, Semenyuta IV, Spiers AJ, Tarasyuk OP, Rogalsky SP. Edna inactivation and biofilm inhibition by the polymeric biocide polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride (PHMGH-Cl) Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):731. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei D, Ma Q, Guan Y, Hu F, Zheng A, Zhang X, Teng Z, Jiang H. Structural characterization and antibacterial activity of oligoguanidine (polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride) Mater Sci Eng C. 2009;29(6):1776–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2009.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen MJ, Morby AP, White GF. Cooperativity in the binding of the cationic biocide polyhexamethylene biguanide to nucleic acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318(2):397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khazandi M, Bird PS, Owens J, Wilson G, Meyer JN, Trott DJ. In vitro efficacy of cefovecin against anaerobic bacteria isolated from subgingival plaque of dogs and cats with periodontal disease. Anaerobe. 2014;28(1):104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang SH, Park JW, Cho KH, Do JY. Association between periodontitis and low-grade albuminuria in non-diabetic adults. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2017;42(2):338–346. doi: 10.1159/000477784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guimarães ARD, Peres MA, Vieira R, Ferreira RM, Ramosjorde ML, Apolinario S, Debom A. Self-perception of side effects by adolescents in a chlochexidine-fluorede-based preventive oral health program. J Appl Oral Sci. 2006;14(4):291–296. doi: 10.1590/s1678-77572006000400015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawrence JR, Zhu B, Swehone GDW, Topp E, Roy J, Wassenaar LI, Rema T, Korber DR. Community-level assessment of the effects of the broad-spectrum antimicrobial chlorhexidine on the outcome of river microbial biofilm development. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(11):3541–3550. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02879-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cruz LMM, Nascimento AGS, Silva LE, Leal B, Kalil MTAC, Almeida HCC. Avaliação da citotoxicidade das soluções de clorexidina nas concentrações de 2,5% a 5% Int J Sci Dent. 2012;38(1):23–28. doi: 10.22409/ijosd.v1i38.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pegoraro J, Silvestri L, Cara G, Stefenon L, Mozzini CB. Efeitos adversos do gluconato de clorexidina à 0,12% J Oral Investig. 2014;3(1):33–37. doi: 10.18256/2238-510X/j.oralinvestigations.v3n1p33-37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 58 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.