Abstract

In this prospective study, we aimed to investigate whether surgical gowns become contaminated during surgery. Samples from the gowns of five surgeons during 19 surgeries were collected using sterile swabs in circular standard delimited areas on both wrists and the mid-chest at three time-points: immediately before surgical incision (t=0), 30 min (t=30), and 60 min (t=60) later. Additionally, at t=0 and t=60, three settle plates of plate count agar were positioned at 1.5 m from the ground and remained open for 20 min. The operating room temperature and relative humidity were monitored. The swabs were cultivated and incubated, and colony-forming units per gram (CFU/g) counts were measured. The CFU/g counts for bacteria or fungi did not differ among the three sampling sites. The surgeons’ lateral dominance in manual dexterity did not influence the gowns’ contamination. There were significant variations in the temperature and relative humidity over time, but not in the CFU/g counts. In conclusion, during the first hour of surgery, surgical gowns did not become a source of contamination and are an effective barrier against bacterial and fungal contamination even under non-standard surgical environmental conditions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-023-01162-4.

Keywords: Contamination, Microbiological load, Surgical site infection, Surgical gown

Introduction

According to the definition of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the USA, surgical site infection (SSI) is a postoperative infection that occurs in the part of the body where the surgery took place [1]. In the 1960s, a pioneering study demonstrated that values greater than 105 microorganisms per gram of tissue contaminate the operative site and increase the risk of developing an SSI [2].

SSIs may result in poor cosmetic outcomes, increased surgery costs, tissue injury, increased risk of pharmacotherapy side effects, and patient death [3]. Eugster et al. [4] found that 5.8% of the examined animals showed postoperative signs of infection-related inflammation and 3% developed an infection associated with purulent discharge. Nicholson et al. [5] reported a postoperative infection rate of 5.9%. SSIs developed in 4.7%, 5.0%, 12%, and 10.1% of clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated, and dirty surgical wounds, respectively [6]. Mayhew et al. [7] reported SSIs in 5.5% of clean and clean-contaminated open surgeries.

Surgical gowns are included in the SSI prevention protocol [1]. However, the relationship between surgical gowns and the risk of SSI remains unclear because of large methodological variations in the available studies, complicating the interpretation of the results [8]. Research is often focused on the type of material used [9]. Pasquarella et al. compared surgical gowns that allow ventilation with those that do not and found no difference in the growth of aerobic microorganisms according to the type of surgical gown [10]. Whyte et al. [11] compared different materials and their ability to repel contaminants, but they did not evaluate their intraoperative use. Finally, Belkin determined that the type of material, its thickness, and the number of washes it undergoes can influence its ability to provide a barrier to microorganisms [12]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined gown contamination during the intraoperative period. In addition, research on bacterial adhesion and transference should include different surfaces in the operating room as possible sources of infection [13, 14].

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate whether surgical gowns become contaminated during surgery, thus becoming a possible source of bacterial and fungal contamination.

Materials and methods

Sampling conditions

All samples were collected in the same operating room (36 m2) of the Small Animal Surgical Center of the University Veterinary Hospital. The room temperature was maintained using an air conditioning system. The maximum room occupancy limit for the experiment was set at seven people, that is, one person/5 m2.

Samples were obtained only during clean or clean-contaminated surgeries according to an established classification [3, 4, 6, 15]. Ten new 100% cotton (270 g/m2) denim gowns purchased from the same manufacturer were used and sterilized after each surgery.

Culture media were sterilized in a vertical autoclave (Model CS3940-80L, Marte Científica, São Paulo, Brazil), with moist saturated steam at 121°C for 15 min, as indicated by the media manufacturer. Glassware and utensils were sterilized and packed in surgical grade paper for 60 min. On the other hand, the surgical gowns were sterilized in a horizontal autoclave (Model 39206-9, Phoenix Luferco, Araraquara, Brazil), with a steam and pressure generation system at 132°C for 20 min. Immediate verification of the process was carried out with a class-1 chemical indicator (Comply Lead-Free Steam Indicator Tape 1322, 3M, Sumaré, Brazil) in all packages. Sterilization of the material was confirmed by the presence of a microbiological test at t=0 (sterile swabs).

Microbiological evaluation of the surgical gowns (sterile swabs)

Samples were collected from the gowns of five veterinary surgeons by two experimenters (individuals procuring the samples) during 19 clean or clean-contaminated surgical procedures on dogs at three time-points: immediately before the surgical incision (t=0), 30 min (t=30), and 60 min (t=60) after. The surgeons did not conduct the operations concomitantly. Four surgeons performed four procedures each, while the fifth surgeon only performed three. Surgeons were informed of sample collection just before the surgical procedure. Only surgeries performed within a 60-min period were included.

Prior to entering the surgical room, all surgical team members were dressed in scrub clothes, surgical footwear, surgical caps, and surgical face masks. Prior to collection, all sterile surgical team members (surgeons and experimenters) underwent a standard surgical team preparation [16]; they performed a 5–7-min hand and arm scrub (2% chlorhexidine gluconate, Rioquimica, São José do Rio Preto, Brazil) and dressed in sterile gowns and sterile surgical gloves.

All sterile swabs were applied over a region bounded by sterile stainless-steel rings (4.75 cm2). Three areas were used: both wrists (in the center of the ventral surface, just above the limit of the surgical glove) and a point on the midline of the chest, taking as its lower limit an imaginary line that passed through the sternum. Immediately after each collection, the swabs were immersed in a test tube containing 2 mL of sterile 0.9% NaCl solution. After the collection process, the tubes were sent to the microbiological analysis laboratory.

The contamination index was evaluated using the total bacterial count with a surface counting technique [17]. Briefly, 100 μL of each tube was dispersed on a standard plate count agar (PCA) surface using a Drigalsky loop. The plates were incubated for 48 h in an oven at 37°C. Subsequently, the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) was counted. The assay was performed in duplicate, and the final calculation was adjusted to express the number of CFU/g.

Microbiological evaluation of the operating environment

Air contamination was evaluated using the sedimentation plate (SP) technique [18, 19] in proportion to one for each 12 m2.

The SPs were positioned at fixed points: the first, between the operating table and the anesthesia machine; the second, next to the surgical instrument table; and the third, below the air conditioner. Petri dishes containing PCA agar were opened at t=0 and t=60. The exposure time was 20 min. After capping, they remained in an oven at 37°C for 48 h. Subsequently, the numbers of CFUs of bacteria and fungi were counted.

Operating room temperature and relative humidity monitoring

A certified digital hygrometer (Model 7663, Incoterm, Porto Alegre, Brazil) was used for temperature and humidity monitoring. The device was positioned 1.5 m above the floor and fixed to the wall.

The parameters were recorded at the gown-sample collection times (t=0, t=30, and t=60) and when the sedimentation plates were opened (t=0 and t=60) and closed (t=20 and t=80).

Data analysis

The dependent variables, CFU/g counts of bacteria and fungi in the surgical gown, were subjected to regression analysis for categorical data with repeated measures using the generalized estimating equation methodology with the GENMOD procedure of SAS (2002), adjusting a model for a negative binomial response, and adopting the independent type (IN) for the correlation matrix. Similarly, as dependent variables, CFU/g counts of bacteria and fungi in the environment were subjected to the same analysis, but the model was adjusted for response with the Poisson distribution. The variables temperature and humidity were analyzed using analysis of variance for a randomized block design and Student’s t test to compare the averages. SAS (Statistical Analysis System, version 9.00, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) software was used for all statistical analyses. GraphPad Prism (version 5.01, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) was used for graphic design. A significance level of 5% was adopted.

Results

Of the 19 surgeries, 11 (58%) were clean and eight were clean-contaminated. There was no difference in the bacterial and fungal counts (CFU/g) across surgeries.

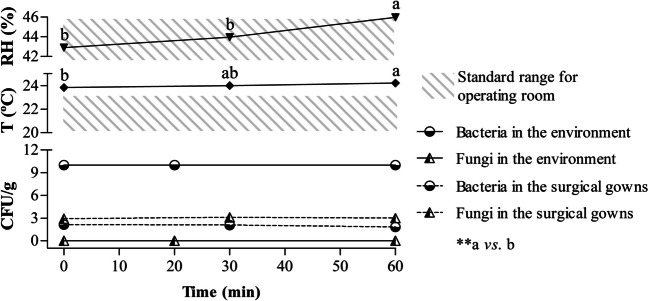

A total of 168 gown samples (58/local) were collected, and there was no significant interaction (P<0.05) between time points and collection areas (both wrists and chest). Moreover, there was no difference (P<0.05) in the CFU/g counts of bacteria and fungi according to the collection areas or time-points. The average operating room ambient temperature significantly increased with time, and the relative humidity (RH) was higher at t=60 than at the other time-points. The SPs showed no variation in the number of CFUs/g for both bacteria and fungi over time (0 to 20 min and 60 to 80 min). Figure 1 summarizes the results displayed in tables (online resources).

Fig. 1.

Summary of results displayed in tables

Discussion

This study showed that even under non-standard operating room conditions, the microbiological load on surgical gowns remains stable during, at least, 60 min of surgery. An average ambient operating room temperature of 24.02 ± 0.19°C does not influence bacterial and fungal growth and/or establishment on the surgical gowns. Clean or clean-contaminated surgeries were selected according to previously established criteria [3, 6] because they have very similar rates of SSI occurrence. The difference in SSI occurrence between clean or clean-contaminated surgeries ranged between 0.3% [15] and 2%66 However, when compared with contaminated and dirty, the difference reaches 7.3% [15] and 15.6% [6], respectively. This selection criterion (clean and clean-contaminated surgeries) eliminated one of the intrinsic (patient-related) risk factors, while the extrinsic factor—surgical gown contamination—was investigated specifically [20]. In this study, data did not show differences in gown contamination according to surgery.

The skin of the individuals present in the operating room is the source of airborne bacteria [21]. The number of bacterium-carrying particles released by surgical staff was 4 CFU/s in a study [22]. In addition, movement leads to the suspension of particles deposited on surfaces and, conversely, deposition of microorganisms on a surface usually occurs from a fluent suspension, implying the action of forces to deposit and others to promote adhesion [23] However, adhesion must resist shear forces, grouped into two categories, i.e., those that prevent it and those that stimulate the detachment of the already adhered microorganisms [24]. The five surgeons declared themselves to be right-handed in their daily activities and thus predominantly used the right hand during surgery, even to pick up materials from the operating table. Interestingly, this did not result in greater contamination of the right wrist over the left. Considering that there was no barrier to deposition, we can say that the gown’s surface did not allow adhesion or that it occurred for a short period because it did not resist the shear forces.

Furthermore, there was no difference in the count of microorganisms between the wrists and the chest. Additionally, there was no significant temporal variation in microbial load.

In this study, the operating room occupancy rate in the intraoperative period was maintained below one person/5 m2. An increase in the number of individuals present in the operating room is correlated with an increase in the microbial count, and a maximum occupancy of 20 people/1000 ft2 (1 person/5 m2) was recommended [25]. Based on the literature and our results, this extrinsic risk factor did not interfere with CFU/g counts.

Environmental monitoring during the intraoperative period was performed by measuring the temperature, RH%, and microbiological control of the air, the last, using the sedimentation plate method. We wondered whether temperature and/or RH% variations could interfere with the contamination of the gowns and/or surgical environment. Recommendations for operating room RH% and temperature ranges vary slightly among authors [1, 25–28]. Our study found that the average values of RH% and temperature ranged from 42.9–45.98% and 23.83–24.21°C, respectively. Although there was a significant increase in RH% in the last 30 min of surgery, the average values remained in the recommended interval of 30–60% [1]. Conversely, the average temperature was outside the standard values of 20–23 °C27 and close to the predicted optimum growth temperatures for many bacteria.

It is not possible to state with absolute precision what was the degree of interference of these findings in the result of the work. However, considering that there were no CFU/g counts indicating a probable contamination of the surgical field [2], it can be suggested that temperature variations were not of sufficient magnitude to generate expressive bacterial and/or fungal growth within 60 min. Furthermore, SPs opened in the environment during the intraoperative period did not show significant variation in the number of CFU/g for both bacteria and fungi over time (0 to 20 min and 60 to 80 min). Thus, the room temperature reaching outside the recommended range did not interfere with the microbial load.

Another important aspect is that the surgical gown should prevent contamination of the surgical field. The low CFU/g count for both bacteria and fungi demonstrated the fulfillment of this requirement. Nevertheless, it should be considered that assessments of gowns did not exceed 60 min and that longer surgeries are correlated with increased SSI rates [3].

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to evaluate the contamination of surgical gowns during use and not based on the type of material from which they are made. In addition, we conducted a prospective study under controlled conditions; most of the studies examining the contamination [9–12] of surgical gowns have been retrospective. During, at least, 60 min of surgery, the microbiological load on surgical gowns remains low and stable even under non-standard operating room conditions.

Supplementary information

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Berríos-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, et al. Centers for disease control and prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(8):784–791. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindberg RB, Moncrief JA, Switzer WE, Order SE, Mills W. The successful control of burn wound sepsis. J Trauma. 1965;5(5):601–616. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196509000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson LL. Surgical site infections in small animal surgery. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2011;41(5):1041–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eugster S, Schawalder P, Gaschen F, Boerlin P. A prospective study of postoperative surgical site infections in dogs and cats. Vet Surg. 2004;33(5):542–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2004.04076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholson M, Beal M, Shofer F, Brown DC. Epidemiologic evaluation of postoperative wound infection in clean-contaminated wounds: a retrospective study of 239 dogs and cats. Vet Surg. 2002;31(6):577–581. doi: 10.1053/jvet.2002.34661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasseur PB, Levy J, Dowd E, Eliot J. Surgical wound infection rates in dogs and cats. Data from a teaching hospital. Vet Surg. 1988;17(2):60–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.1988.tb00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayhew PD, Freeman L, Kwan T, Brown DC. Comparison of surgical site infection rates in clean and clean-contaminated wounds in dogs and cats after minimally invasive versus open surgery: 179 Cases (2007-2008) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;240(2):193–198. doi: 10.2460/javma.240.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humphreys H. Preventing surgical site infection. Where now? J Hosp Infect. 2009;73(4):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koch F. Perspectives on barrier material standards for operating rooms. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32(2):114–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2003.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasquarella C, Pitzurra O, Herren T, Poletti L, Savino A. Lack of influence of body exhaust gowns on aerobic bacterial surface counts in a mixed-ventilation operating theatre. A study of 62 hip arthroplasties. J Hosp Infect. 2003;54(1):2–9. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(03)00077-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whyte W, Hamblen DL, Kelly IG, Hambraeus A, Laurell G. An investigation of occlusive polyester surgical clothing. J Hosp Infect. 1990;15(4):363–374. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(90)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belkin NL. Effect of laundering on the barrier properties of reusable surgical gown fabrics. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27(3):304–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knobben BA, van der Mei HC, van Horn JR, Busscher HJ. Transfer of bacteria between biomaterials surfaces in the operating room—an experimental study. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;80(4):790–799. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker M, Singh A, Rousseau J, Weese JS. Bacterial contamination of gloves worn by small animal surgeons in a veterinary teaching hospital. Can Vet J. 2014;55(12):1160–1162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown DC, Conzemius MG, Shofer F, Swann H. Epidemiologic evaluation of postoperative wound infections in dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1997;210(9):1302–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fossum TW. Preparation of the surgical team. In: Fossum TW, editor. Small Animal Surgery. 5. St Louis: Mosby. United Kingdom; 2018. pp. 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark DS. Studies on the surface plate method of counting bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1971;17(7):943–946. doi: 10.1139/m71-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trabulsi LR, Alterthun F, Gompertz OF. Candeias JAN. Microbiologia. 6. São Paulo: Atheneu; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Utescher CLA, Franzolin MR, Trabulsi LR, Gambale V. Microbiological monitoring of clean rooms in development of vaccines. Braz. J Microbiol. 2007;38(4):710–716. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burgatti JC, Lacerda RA. Systematic review of surgical gowns in the control of contamination/surgical site infection. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2009;43(1):237–244. doi: 10.1590/S0080-62342009000100031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z, Liu H, Yin H, Rong R, Cao G, Deng Q. Prevention of surgical site infection under different ventilation systems in operating room environment. Front Environ Sci Eng. 2021;15(3):36. doi: 10.1007/s11783-020-1327-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadrizadeh S, Tammelin A, Ekolind P, Holmberg S. Influence of staff number and internal constellation on surgical site infection in an operating room. Particuology. 2014;13:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.partic.2013.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Oss CJ, Good RJ, Chaudhury MK. The role of van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonds in “hydrophobic interactions” between biopolymers and low energy surfaces. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1986;111(2):378–390. doi: 10.1016/0021-9797(86)90041-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boks NP, Norde W, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Forces involved in bacterial adhesion to hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces. Microbiology (Reading) 2008;154(10):3122–3133. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/018622-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu Shaw L, Chen IH, Chen CS, et al. Factors influencing microbial colonies in the air of operating rooms. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2928-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medeiros AC, Araújo-Filho I. Surgical theater and safe surgery Centro cirúrgico e cirurgia segura. J Surg Cl Res. 2017;8:77–105. doi: 10.20398/jscr.v8i1.13037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sehulster LM, Chinn RYW, Arduino MJ, et al. Recommendations from CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). In. Chicago IL: American Society for Healthcare Engineering/American Hospital Association; 2004. Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities; p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- 28.A.B.N.T. Air conditioning for healthcare facilities - requirements for design and installation [Tratamento de ar em estabelecimentos assistenciais de saúde (EAS). Requisitos para projeto e execução de instalações]. In: ABNT, ed. Vol NBR 7.256/2005. Rio de Janeiro, BR2005.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.