Abstract

Treatments for alopecia areata (AA) have traditionally been prescribed off-label, and there has been no universal agreement on how to best manage the condition. Baricitinib is the first oral selective Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor approved for the treatment of adults with severe AA. As a better understanding of the evidence supporting the management of AA in clinical practice is needed, we conducted a systematic literature review and subsequent narrative review to describe available evidence pertaining to the efficacy and tolerability of treatments currently recommended for adults with moderate-to-severe forms of AA. From 2557 identified records, a total of 53 records were retained for data extraction: 9 reported data from 7 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) versus placebo, and 44 reported data from unique RCTs with no placebo arm, non-randomized trials, or observational studies. Across drug classes, data were reported heterogeneously, with little consistency of data collection or clinical endpoints used. The most robust evidence was for the JAK inhibitor class, in particular the JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor baricitinib. Five RCTs (three for baricitinib) demonstrated a consistent benefit of JAK inhibitor therapy over placebo across various clinical outcomes in adult patients with at least 50% scalp hair loss. Overall, hair regrowth varied widely for the other drug classes and was generally low for patients with moderate-to-severe AA. Relapses were commonly observed during treatment and upon discontinuation. Adverse effects were generally consistent with the known safety profile of each intervention. The heterogeneity observed prevented the conduct of a network meta-analysis or an indirect comparison of different treatments. We found that the current management of patients with moderate-to-severe AA often relies on the use of treatments that have not been well evaluated in clinical trials. The most robust evidence identified supported the use of baricitinib, and other oral JAK inhibitors, in patients with severe AA.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-023-01044-5.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, Baricitinib, Janus kinase inhibitors, Systematic review, Treatment

Plain Language Summary

To date, there has been no universal agreement on how to best manage alopecia areata (AA), suggesting that a better understanding of the evidence for the different treatment options is needed. Most of the treatments traditionally used for AA have not been approved for this indication. Baricitinib is the first oral selective Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor approved for the treatment of adults with severe AA. Consequently, we extensively reviewed the available literature for evidence regarding the efficacy and tolerability of treatments currently recommended for adults with moderate-to-severe forms of AA. Although we found many potential reports, only 53 provided the type of information we believed to be relevant, with 9 describing findings from 7 randomized controlled trials versus placebo. Across treatments, there was little consistency of data collection or clinical endpoints used. The most robust evidence was for the JAK inhibitor class, in particular baricitinib, which was consistently more beneficial than placebo across various clinical outcomes in adults with at least 50% scalp hair loss. For the other classes of drugs, hair regrowth varied widely, was generally low for patients with moderate-to-severe hair loss, and commonly did not last. Reported adverse effects were generally as expected for each treatment. We found that the current management of patients with moderate-to-severe AA often relies on the use of treatments that have not been well evaluated in clinical trials. However, strong evidence supports the use of baricitinib, and other oral JAK inhibitors, in patients with severe AA.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-023-01044-5.

Key Summary Points

| There has been no universal agreement on how to best manage alopecia areata (AA), possibly because of the lack of options approved for this indication and the heterogeneous reporting of data across drug classes, with little consistency of data collection or clinical endpoints used. | |

| A systematic literature review identified that the most robust available evidence is for the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor class, in particular baricitinib, which was consistently shown to be more beneficial than placebo across various clinical outcomes in adults with at least 50% scalp hair loss. | |

| Overall, hair regrowth varied widely for the other classes of drugs (systemic corticosteroids, topical immunotherapy, cyclosporine A, methotrexate, and azathioprine), was generally low for patients with moderate-to-severe AA, and relapses were common. | |

| The current management of patients with moderate-to-severe AA often relies on the use of treatments that have not been well evaluated in clinical trials, but the most robust available evidence supports the use of baricitinib, and other oral JAK inhibitors, in patients with severe AA. |

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease associated with non-scarring hair loss that typically affects the scalp but can also affect other parts of the body; its severity can range from small patches of hair loss to total hair loss [1–4]. Hair regrowth is common in the early stages of the disease (spontaneous or on treatment), but tends to be rare for patients with chronic and extensive hair loss [1, 5]. AA can be associated with a substantial quality-of-life impairment and psychological burden [6–8].

Until 2022, physicians had traditionally relied on treatments prescribed off-label [9], as there were no systemic therapies for AA approved by major regulatory bodies such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or European Medicine Agency (EMA). Several guidelines and an expert consensus have been published, but no universal agreement exists on how to best manage AA [1, 4, 10, 11].

With the recent approval of baricitinib [12, 13], an oral selective Janus kinase (JAK)1/JAK2 inhibitor, for the treatment of AA, there is a need to better understand the evidence supporting the management of AA in clinical practice. To this end, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) to describe the evidence pertaining to the efficacy and tolerability of treatments currently recommended for moderate-to-severe forms of AA.

Methods

SLR

We conducted an SLR in accordance with guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [14]. The eligibility criteria that defined the scope of studies to be synthetized in the SLR were defined according to Population, Intervention, Comparators, Outcomes, and Study (PICOS) design criteria and are listed in Table 1. The list of interventions included in the search strategies was identified from treatment guidelines and consensus statements [1, 10, 11, 15].

Table 1.

Summary of PICOS eligibility criteria for the SLR

| PICOS | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Patient population | Adults (as defined by the investigator) with alopecia areata (including alopecia universalis, alopecia totalis, and alopecia ophiasis) |

Children Any population that is not mentioned in the inclusion criteria |

| Interventions |

Topical CS: e.g., desoximetasone, clobetasol Intralesional steroids: e.g., triamcinolone, hydrocortisone Systemic CS: e.g., prednisolone, methylprednisolone, dexamethasone Glucocorticoids: e.g., prednisone, hydrocortisone, betamethasone Contact immunotherapy: e.g., 1-chloro,2,4-dinitrobenzene, squaric acid dibutyl ester, 2,3-diphenylcyclopropenone (diphencyprone) Photochemotherapy: psoralen plus artificial phototherapy Potassium channel opener: e.g., minoxidil Plasma-rich protein Topical dithranol (anthralin) Topical calcineurin inhibitors: e.g., ciclosporin (cyclosporine A), tacrolimus, pimecrolimus Systemic immunosuppressants: e.g., methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine Prostaglandin F2α analogues: e.g., latanoprost, bimatoprost JAK inhibitors: e.g., baricitinib, tofacitinib, ruxolitinib, ritlecitinib, deuruxolitinib Biologics: e.g., tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (e.g., etanercept); interleukin inhibitors (e.g., ustekinumab) Miscellaneous treatments: isoprinosine, 308-nm excimer laser, aromatherapy, hypnotherapy, bexarotene, mycophenolate mofetil, dapsone, simvastatin/ezetimibe, sulfasalazine, and apremilast |

Interventions not listed |

| Comparators |

Any of the above interventions of interest Placebo No comparator |

Comparators not listed |

| Outcomes |

Any ClinRO measure for scalp hair (e.g., Severity of Alopecia Tool score) Any ClinRO measure for eyebrow hair loss† Any ClinRO measure for eyelash hair loss† Any PRO measure for scalp hair† (e.g., Scalp Hair Assessment) Any PRO measure for eyebrows† Any PRO measure for eyelashes† Any PRO measure for eye irritation† Other PRO measures Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) Alopecia Areata Quality of Life Index Short-Form-36 EuroQol-5 Dimension (all forms/types) Skindex 16 or 29 adapted or used for alopecia areata Drug safety measures AEs Serious AEs |

None of the outcomes listed as inclusion criteria |

| Study design |

RCTs‡ Prospective trials (non-randomized) All observational studies (prospective or retrospective or case reports, or case series) with pooled results (i.e., outcomes reported across multiple patients) Commentaries or letters with original data |

SLRs§ Studies which do not have study drug efficacy/safety as a primary or secondary objective Preclinical studies Prognostic studies Case reports/series with individual patient data/results Commentaries and letters without original data Consensus reports Narrative reviews |

| Time frame | No time limit | No restrictions |

| Countries | No limit | No restrictions |

| Language¶ | None | No restrictions |

AE adverse event, ClinRO clinician-reported outcome, CS corticosteroid, JAK Janus kinase, PICOS Population, Intervention, Comparators, Outcomes and Study design, PRO patient-reported outcome, RCT randomized controlled trial, SLR systematic literature review

†Studies reporting similar/generic PROs were included at the screening process and a decision was made on whether to extract based on the type of data available

‡RCTs without results (e.g., trial listings) were included but not extracted

§Previous SLRs were identified separately and their bibliographies were searched for any additional studies not otherwise identified in our search strategy

¶The search did not exclude non-English studies, but such studies (if not accompanied by English-language versions) were retained separately to determine whether they likely contained additional relevant information

Search Strategies and Information Sources

Searches for peer-reviewed publications were conducted in Embase, MEDLINE, and using the Cochrane website. Conference proceedings (as summarized in Table 2) for the years 2019–2022 were searched.

Table 2.

Conference proceedings searched for articles of interest

| Conference | Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting | Embase | Embase | Hand search | Hand search |

| Annual Alopecia Areata Conference (National Alopecia Areata Foundation) | Hand search | Hand search | Hand search | – |

| British Association of Dermatologists Annual Meeting | Embase | Embase | Hand search | Hand search |

| European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress | Hand search | Hand search | Hand search | – |

| European Society for Dermatological Research Annual Meeting | Hand search | No meeting | Hand search | – |

| Society of Investigative Dermatology Annual Meeting | Embase | Embase | Hand search | Hand search |

– Not searched because the meeting for that year occurred after the search was run or the database was not available, Embase Excerpta Medica database

Clinical trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and the European Union Clinical Trials Register), key Health Technology Assessment (HTA) databases, and other relevant websites were also searched to identify ongoing trials and drug assessments. Additionally, the bibliographies of several published SLRs were hand-searched for eligible records.

Literature searches were originally performed on July 2, 2021, and they were updated on February 4, 2022, and again on July 11, 2022. The full search strategies used for each search are presented in Table S1.

Selection Procedure

Titles and abstracts of identified publications were independently checked by two reviewers in parallel to select those that would proceed to full-text review; discrepancies in decisions were referred to a third reviewer. The same process was applied to publications selected for full-text review to ascertain final eligibility. Searches of conference proceedings, clinical trial registries, HTA databases, and other websites were performed by a single reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Conference abstracts that presented data also available in a peer-reviewed publication were excluded. If duplicate abstracts with identical information were identified, only the most recent abstract was selected. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram was created.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted by one reviewer and independently checked by another. To facilitate the synthesis of evidence, selected records were allocated to one of three categories based on population, intervention, and study design. The first category (category 1) included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) versus placebo, with interventions recommended for the treatment of adults with moderate-to-severe forms of AA (systemic corticosteroids, topical immunotherapy, systemic immunosuppressants [i.e., cyclosporine A, methotrexate, azathioprine], and oral JAK inhibitors) [1, 10, 11, 15]. A suitable number of studies in this category may allow meta-analysis or combined analysis across treatments. The second category (category 2) included non-randomized trials and observational studies as well as RCTs without a placebo arm, with interventions recommended for the treatment of adults with moderate-to-severe forms of AA. The final category (category 3) included records with data from adults with mostly mild-to-moderate forms of AA or severity of hair loss at baseline that was not documented; records of studies assessing interventions that did not fall into category 1 or 2 (i.e., that were not recommended or were recommended in mild forms of AA or as adjunctive therapy only) were also included in category 3. Category 1 describes studies providing the highest level of evidence, while category 2 provided data for a narrative summary beyond placebo-controlled RCTs. Records in all three categories met the inclusion criteria, but only those included in categories 1 and 2 met the objective of our SLR. As a result, full data extraction was carried out for records falling into categories 1 and 2, whereas records falling into category 3 were summarized only. There was no formal data extraction from relevant entries identified in clinical trial registries, HTA databases, and other websites; rather, this search was conducted for informative purposes to better understand the treatment landscape.

Narrative Summary

The narrative summary focused on category 1 and 2 records, which reported data related to interventions recommended for the treatment of adults with moderate-to-severe forms of AA: systemic corticosteroids, topical immunotherapy, systemic immunosuppressants (cyclosporine A, methotrexate, azathioprine), and oral JAK inhibitors.

Quality Assessment

Quality assessment was performed by one reviewer and then checked by a second reviewer for all fully extracted records, except for conference proceedings and category 3 records. Assessment of the quality of RCTs was conducted using guidance provided by the Cochrane Collaboration [16]. The Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) checklist [17] was used for non-randomized trials and observational studies.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

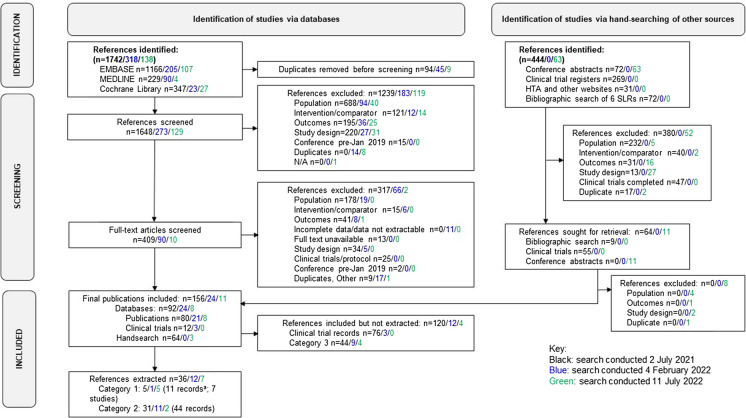

Of 2557 identified records, a total of 53 were retained for data extraction. Nine records reported data from seven RCTs versus placebo (category 1), and 44 reported data from unique non-randomized trials, observational studies, or RCTs with no placebo arm (category 2) (Fig. 1). Data related to category 1 and 2 records are presented in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 [18–70]. Information on records allocated to category 3 and excluded from the current summary is provided in Table S2.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the evolution of studies included in the current systematic narrative review. Category 1: RCTs versus placebo, with interventions recommended for moderate-to-severe forms of AA (systemic corticosteroids, systemic immunosuppressants, JAK inhibitors, contact immunotherapy). Category 2: uncontrolled and observational studies and RCTs without placebo, with interventions recommended for moderate-to-severe forms of AA. Category 3: mixed populations of adults and children; only or mostly adults with mild-to-moderate forms of AA or severity of hair loss at baseline that was not documented; interventions that did not fall into category 1 or 2 (i.e., they were not recommended in guidelines or were recommended in mild forms of AA or as adjunctive therapy only). aTwo of these records were abstracts that reported preliminary data from studies with full publications. These records were subsequently excluded to give a total of 53 references with extracted data (9 category 1 and 44 category 2). AA alopecia areata, HTA Health Technology Assessment, JAK Janus kinase, PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, RCT randomized controlled trial

Table 3.

Summary of category 1 and 2 systemic corticosteroid studies included in the SLR

| Study | Study type | Baseline severity | Sample size (completers) | Treatments | Duration of disease | Response assessment(s)† | Response assessment period | Main efficacy findings | Tolerability/safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1: PBO-controlled RCT | |||||||||

| Kar et al. [18] | PBO-controlled RCT | Severe AA: ≥ 40% scalp hair loss or > 10 patches scattered over scalp and body |

N = 43 (N = 36) |

PN (200 mg QW) (PT) N = 23 PBO N = 20 |

PN: mean 3.1 Yr PBO: mean 2.8 Yr |

> 30% hair regrowth > 60% hair regrowth Relapse (hair loss > 20%) |

3 Mth FU: EOT + 3 Mth |

Hair regrowth > 30% PN: 8/20 (40%) PBO: 0/16 (0%) P < 0.03 Hair regrowth > 60% PN: 2/20 (10%) PBO: 0/16 (0%) Relapse PN: 2/8 (25%) |

AE rates: PN: 11/20 (55%) PBO: 2/16 (13%) P < 0.05 AEs: weakness, acne, weight gain, gastrointestinal symptoms, facial mooning, oligomenorrhea |

| Category 2: non-randomized trials, observational studies, RCT without PBO control | |||||||||

| Dehghan et al. [19] | Non-randomized | Severe AA: ≥ 30% of scalp hair loss or > 10 patches on scalp and body |

N = 40 (N = 35) |

PN (200 mg QW for 3 Mth) (PT) N = 20 MP (500 mg IV 3 × per Mth for 6 Mth) (PT) N = 20 |

PN; mean 3.3 Yr MP: mean 2.9 Yr |

31–60% hair regrowth > 60–90% hair regrowth 91–100% hair regrowth |

≤ 12 Mth |

6 Mth Hair regrowth 60–90% PN: 4 (22%) MP: 10 (59%) Hair regrowth 91–100% PN: 5 (28%) MP: 7 (41%) 12 Mth Hair regrowth 60–90% PN: 3 (17%) MP: 6 (35%) Hair regrowth 91–100% PN: 4 (22%) MP: 7 (41%) |

AEs: acne, heartburn, striae |

| Kurosawa et al. [20] | Retrospective | “Extensive” AA: single or multiple patches or AT/AU |

N = 91 AA: n = 51 AT/AU: n = 38 |

PN (80 mg/d for 3 days Q3M) (PT) N = 29 IM TA (40 mg 1 Q1M, then Q1.5 M for 1 Yr) N = 43 DM (0.5 mg/d for 6 Mth) N = 19 |

NR |

> 40% regrowth of terminal hair (response) Relapse (appearance of new patches or abnormal increase in hair loss) |

EOT FU: EOT: + ≥ 3 Mth |

Response rates in AA (patches) PN: 9/12 (75%) TA: 24/31 (77%) DM: 4/10 (40%) Response rates in AT/AU PN: 10/17 (59%) TA: 8/12 (67%) DM: 3/9 (33%) Relapse rates in AA (patches) PN: 3/12 (25%) TA: 10/31 (33%) DM: 5/10 (50%) Relapse rates in AT/AU PN: 8/17 (47%) TA: 9/12 (75%) DM: 9/9 (100%) |

AE rates: PN: 3/29 (10%) TA: 23/56 (41%) DM: 6/20 (30%) AEs: dysmenorrhea, abdominal discomfort, acne, weight gain, weakness, mooning |

| Vano-Galvan et al. [21] | Non-randomized | AT, AU |

N = 31 AT: n = 9 AU: n = 22 |

DM (0.1 mg/kg/d 2 × per Wk) (PT) N = 31 | NR |

Complete response: regrowth on ≥ 75% of scalp Partial response: regrowth on < 75% of scalp Persistent response: > 75% regrowth for ≥ 3 Mth after EOT |

4 Mth FU: EOT + 3 Mth |

Complete response: 22/31 (71%) Partial response: 3/31 (10%) Persistent response: 10/31 (32%) |

AE rate: 10/31 (32%) AEs: weight gain, Cushing syndrome, striae, irritability AE-related discontinuations: n = 1 |

| Yoshimasu et al. [22] | Non-randomized |

S1 (< 25% hair loss) S2 (25–49% hair loss); S3 (50–74% hair loss) S4 (75–99% hair loss); S5 (100% hair loss) |

N = 55 S1 & S2 for ≤ 6 Mth: n = 18 S1 & S2 for > 6 Mth: n = 2 S3 & S4 for ≤ 6 Mth: n = 18 S3 & S4 for > 6 Mth: n = 11 S5 for ≤ 6 Mth): n = 2 S5 for > 6 Mth:n = 4 |

MP (500 mg/d IV for 3 days Q1M for up to 3 courses) (PT) | Severity groups divided according to duration ≤ 6 vs. > 6 Mth |

Short-term FU response: any regrowth of vellus hair Long-term FU response: > 75% regrowth |

Short-term FU: EOT Long-term FU: EOT + 6 Mth |

Response rates S1 & S2 for ≤ 6/ > 6 Mth: 100%/100% (short-term FU) 100%/100% (long-term FU) S3 & S4 ≤ 6/ > 6 Mth: 83%/82% (short-term FU) 67%/73% (long-term FU) S5 (≤ 6/ > 6 Mth): 100%/0% (short-term FU) 50%/0% (long-term FU) |

AE rate: 20/55 (36%) AEs: myalgia/numbness, edema, stomach discomfort, infection, arthralgia, burning sensation |

All drugs administered orally unless otherwise mentioned

AA alopecia areata, AE adverse event, AT alopecia totalis, AU alopecia universalis, d day(s), DM dexamethasone, EOT end of therapy, FU follow-up period, IM intramuscularly, IV intravenously, MP methylprednisolone, Mth month(s), N total number of patients, n number of patients in the category, NR not reported, PBO placebo, PN prednisolone, PT pulse therapy, QxM every x months, QW once a week, RCT randomized controlled trial, SLR systematic literature review, TA triamcinolone acetate, Wk week(s), Yr year(s)

†Including primary hair regrowth endpoint (where specified); other hair regrowth endpoints focus on SALT50 and eyebrow and eyelash regrowth and relapse, where reported

Table 4.

Summary of category 2 topical immunotherapy studies included in the SLR

| Study | Study type | Baseline severity | Sample size (completers) | Treatments | Duration of disease | Response assessment(s)† | Response assessment period | Main efficacy findings | Tolerability/safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category 2: non-randomized trials, observational studies, RCT without PBO control | |||||||||

| Al Bazzal et al. [23] | RCT without PBO control |

AA: > 20% scalp hair loss (persistent AT or AU excluded); Mean SALT 69.46–85.20 |

N = 30 |

DPCP (QW) test protocol N = 15 DPCP (QW) standard protocol N = 15 |

DPCP test protocol mean 81 Mth DPCP standard protocol: mean 49 Mth |

SALT75 | 6 Mth |

SALT75 test protocol: 4/15 (27%) standard protocol: 1/15 (7%) No patients achieved complete hair regrowth |

AEs: hand/neck eczema, severe pruritus and blistering on scalp |

| Avgerinou et al. [24] | Non-randomized |

AA: > 25% of scalp hair loss or long-lasting AA (no hair re-growth for > 12 months |

N = 64 (N = 54) S1 (≤ 25% scalp hair loss): n = 6 S2 (26–50%): n = 14 S3 (51–75%): n = 20 S4 (76–99%): n = 8 S5 (100%): n = 6 |

DPCP (QW) | Mean 5.8 Yr |

Grade 1: regrowth of vellus hair Grade 2: regrowth of sparse pigmented terminal hair Grade 3: regrowth of terminal hair with patches of alopecia Grade 4: regrowth of terminal hair on the whole scalp |

6 Mth FU: to 2 Yr |

Grade 3: 15/54 (28%) Grade 4: 20/54 (37%) Relapsed and retreated: 31/45 (69%) |

AEs: contact dermatitis of face/neck AE-related discontinuations: n = 4 (7%) |

| Case et al. [25] | Non-randomized | Severe AA: > 30% scalp hair loss, AT, AU |

N = 26 (N = 21) AA: n = 11 AT/AU: n = 10 |

SADBE | Mean 8.3 Yr | Complete regrowth (100% of scalp regrowth) |

NR FU: to 1 Yr |

Complete regrowth 6/21 (29%) AA: 4/11 (36%) AU/AT: 2/10 (20%) Relapse: 4/6 (67%) |

AEs: contact dermatitis of face, lymphadenopathy |

| Cotellessa et al. [26] |

No PBO control Split-scalp, randomized, then whole scalp if response |

Extensive AA for ≥ 1 year: > 30% scalp hair loss |

N = 56 (N = 52) 30–90% scalp hair loss: n = 14 > 90% scalp hair loss: n = 42 |

DPCP (QW) for 6–12 Mth | Mean 6.0 Yr |

Grade 1: regrowth of vellus hair Grade 2: regrowth of sparse pigmented terminal hair Grade 3: regrowth of terminal hair with patches of alopecia Grade 4: regrowth of terminal hair on the whole scalp |

6 Mth FU: EOT + 6–18 Mth |

Grade 4: 25/52 (48%) Grade 3/2: 11/52 (21%) Relapse: 10/25 (40%) |

AEs: contact eczema of face/neck, edema of eyelids AE-related discontinuations: n = 4 (7%) |

| Ghandi et al. [27] | RCT without PBO control | AA: > 25% scalp hair loss |

N = 50 (N = 35) |

DPCP N = 25 DPCP + anthralin N = 25 |

NR |

A0: No hair regrowth A1: < 25% hair regrowth A2: 26–50% regrowth A3: 51–75% hair regrowth A4: 76–99% hair regrowth A5: 100% hair regrowth |

6 Mth |

DPCP A1: 10/16 (63%) A2: 1/16 (6%) A3: 1/16 (6%) A4: 1/16 (6%) A5: 3/16 (19%) DPCP + anthralin A1: 8/19 (42%) A2: 2/19 (11%) A3: 5/19 (26%) A4: 1/19 (5%) A5: 3/19 (16%) |

AEs: pruritus, hyperpigmentation, erythema AE-related discontinuations: DPCP 5/25 (20%) DPCP + anthralin 3/25 (12%) |

| Hull and Norris [28] |

Non-randomized Split-scalp |

Mild to moderate AA (< 50% scalp hair loss); severe AA (> 50% scalp hair loss); subtotal alopecia; total alopecia |

N = 36 (N = 28) Mild to moderate: n = 4 Severe: n = 4 Subtotal AA: n = 7 Total AA: n = 13 |

DPCP (QW) | Mean 19.9 Yr |

Grade 1: regrowth of vellus hair Grade 2: regrowth of sparse pigmented terminal hair Grade 3: regrowth of terminal hair with patches of alopecia Grade 4: regrowth of terminal hair on the whole scalp |

8 Mth |

Grade 4: 8/28 (29%) Grade 3: 2/28 (7%) Grade 2: 2/28 (7%) Grade 1: 2/28 (7%) |

AEs: blistering eruptions, periorbital edema, eczematous rashes AE-related discontinuations: n = 2/36 (6%) |

| Maryam et al. [29] | Retrospective | Severe AA: > 75% hair loss; Moderate AA: 26% to 75% hair loss; Mild AA: < 25% hair loss |

N = 54 Mild AA: n = 1 Moderate AA: n = 16 Severe AA: n = 37 |

DPCP (QW) | Mean 7.8 Yr |

Terminal scalp hair regrowth: Excellent (76–100%) Good (51–75%) Moderate (26–50% Mild (< 25%) |

During tx (> 1.5 Yr) |

Excellent: 22/54 (41%) Good: 8/54 (15%) Moderate: 8/54 (15%) Mild: 16/54 (30%) Relapse during tx: 33% |

AEs included: dermatitis on face/neck, hyperpigmentation, occipital lymphadenopathy |

| Rocha et al. [30] | RCT without PBO control |

AA; SALT score ≥ 50 SALT range 60–100 |

N = 24 (N = 16) Total AA: n = 3 UA: n = 13 Extensive multifocal AA: n = 8 |

DPCP N = 13 Anthralin N = 11 |

Duration of current episode: 8–240 Mth | SALT score | 6 Mth |

Median SALT score (BL/6 Mth) DPCP: 98/89.9 Anthralin: 100/99.9 No patient achieved > 75% hair regrowth |

AEs: eczema, urticaria, erythema and pruritus) |

| Shapiro et al. [31] | RCT without PBO control for treatment of interest | Chronic severe AA: > 50% scalp hair loss |

N = 15 (N = 13) |

DPCP (QW) (N = 7) DPCP + 5% minoxidil (N = 6) |

Mean 12 Yr (range 2–55) | Response: > 75% regrowth of terminal hair | 24 Wk |

DPCP: 3/7 DPCP + minoxidil: 2/6 |

AEs: localized lymphadenopathy, severe generalized dermatitis, painful scalp vesiculations, hyperpigmentation AE-related discontinuations (n = 2, 13%) |

| Sriphojanart et al. [32] | Retrospective | AA: > 50% scalp hair loss | N = 39 |

DPCP (QW) test protocol (N = 16) DPCP (QW) standard protocol (N = 23) |

Test protocol Mean 61.9 Wk Standard protocol Mean 56.9 Wk |

> 75% hair regrowth Relapse: > 25% hair loss after complete hair regrowth |

6 Mth FU: EOT + ≥ 6 Mth |

> 75% hair regrowth Test protocol: 8/16 (50%) Standard protocol: 12/23 (52%) Relapse Test protocol: 4/16 (25%) Standard protocol: 5/23 (22%) |

AEs: blistering, widespread eczema, dyspigmentation, lymphadenopathy |

| Thuangtong et al. [33] |

Not randomized to intervention of interest Split-scalp, randomized |

Chronic, severe AA: > 50% hair loss (N = 2), AT (N = 1), AU (N = 7); mean SALT: 47.1–47.3 |

N = 10 (N = 8) |

DPCP (QW) + PBO DPCP (QW) + anthralin |

Median 3.6 Yr (range 0.08–20) | SALT score | 6 Mth |

Mean SALT score (BL/6 Mth) DPCP + PBO: 47.3/40.7 DPCP + anthralin: 47.1/38.62 |

AEs: dryness, excessive dermatitis, pruritus, folliculitis, hyperpigmentation AE-related discontinuation: n = 1 (10%) |

| Thuangtong et al. [34] |

No PBO control Split-scalp, randomized |

AT (N = 6) AU (N = 14) |

N = 20 (N = 12) |

DPCP (QW) test protocol DPCP (QW) standard protocol (details NR) |

Mean 1.0 Yr (range 0.17–15) |

> 75% hair regrowth < 75% hair regrowth |

34 Wk |

> 75% hair regrowth: 5/20 (25%) < 75% hair regrowth: 7/20 (35%) |

AEs: vesicle formation, generalized eczema, folliculitis AE-related discontinuations: n = 5 (25%) |

| Tiwary et al. [35] | RCT without PBO control | AA: > 20% of scalp hair loss |

N = 24 (N = 24) |

SADBE (QW) N = 12 DPCP (QW) N = 12 |

NR |

CFB in SALT score Hair regrowth A0 = no change or further loss of hair A1 = 1–24% regrowth A2 = 25–49% regrowth A3 = 50–74% regrowth A4 = 75–99% regrowth A5 = 100% regrowth |

24 Wk |

Mean CFB in SALT score: SADBE: 21.3 DPCP: 14.1 Hair regrowth SADBE A0: 0/12 A1: 0/12 A2: 4/12 A3: 7/12 A4: 1/12 A5: 0/12 DPCP A0: 1/12 A1: 2/12 A2: 5/12 A3: 4/12 A4: 0/12 A5: 0/12 |

AE rates: SADBE: 2/12 DPCP: 10/12 AEs: contact urticaria, vesicular eruptions, regional lymphadenopathy, hypopigmentation, local abscess, generalized urticaria, facial edema, flu-like symptoms |

All drugs administered orally unless otherwise mentioned

AA alopecia areata, AE adverse event, AT alopecia totalis, AU alopecia universalis, BL baseline, CFB change from baseline, DPCP diphenylcyclopropenone, EOT end of therapy, FU follow-up, Mth month(s), N total number of patients, n number of patients in the category, NR not reported, PBO placebo, QW once a week, RCT randomized controlled trial, SADBE squaric acid dibutyl ester, SALT Severity of Alopecia Tool, SALT75 > 75% change in SALT score from BL, SLR systematic literature review, tx treatment, Wk week(s), Yr year(s)

†Including primary hair regrowth endpoint (where specified); other hair regrowth endpoints focus on SALT50 and eyebrow and eyelash regrowth and relapse, where reported

Table 5.

Summary of category 1 and 2 cyclosporine A studies included in the SLR

| Study | Study type | Baseline severity | Sample size (completers) | Treatments | Duration of disease | Response assessment(s)† | Response assessment period | Main efficacy findings | Tolerability/safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1: PBO-controlled RCT | |||||||||

| Lai et al. [36] | PBO-controlled RCT | Moderate-to-severe AA**, mean SALT 79.4 |

N = 36 (N = 32) |

CsA (4 mg/kg/d) N = 18 PBO N = 18 |

Duration of current episode: mean 6.5 Yr |

Primary: SALT50 Pt achieving ≥ 1-grade improvement in EB/EL assessment scale score (0, none to 3, normal) |

3 Mth |

SALT50 CsA: 5/16 (31%) PBO: 1/16 (6%) ≥ 1-grade improvement in EB score CsA: 5/16 (31%) PBO: 0/16 (0%) P = 0.02 ≥ 1-grade improvement in EL score CsA: 3/16 (19%) PBO: 0/16 (0%) |

AE rates: CsA: 15/18 (83%) PBO: 15/18 (83%) AEs in ≥ 5% pt: headache, paresthesia, abdominal pain, nausea, UTI, musculoskeletal disorders, respiratory disorders, pruritis, hirsutism |

| Category 2: non-randomized trials, observational studies, RCT without PBO | |||||||||

| Ferrando and Grimalt [37] | Non-randomized |

Severe AA‡ AU, AT, patchy |

N = 15 | CsA (average: 150 mg BID) | Mean 9.8 Yr (range 1–24) | % hair regrowth | 1–12 Mth |

≥ 90% hair regrowth: 2/15 (13%) ≥ 75% hair regrowth: 5/15 (33%) |

AEs: asthenia, gingival hyperplasia/residual diastema, hypotrichosis, severe hypertension, atopy AE-related discontinuations: n = 1 |

| Gupta et al. [38] | Non-randomized trial | Severe AA, AU, AT: > 5 patches on scalp |

N = 6 AU: n = 3 AT: n = 1 AA: n = 2 |

CsA (6 mg/kg/d) | Mean 8 Yr (range 0.5–17) | Scalp hair regrowth > 90% | EOT (12 Wk) and after 3 Mth |

Hair regrowth > 90%: EOT: 3/6 (50%) EOT + 3 Mth: 0/6 (0%); scalp cosmetically unacceptable in all patients |

AEs: headache, dysesthesia, fatigue, diarrhea, erythematous rash, transient elevations in blood urea nitrogen, gingival hyperplasia, flushing, myalgias |

| Jang et al. [39] | Retrospective |

Mild AA: < 50% scalp hair loss Severe AA: ≥ 50% scalp hair loss, including AT, AU |

N = 88 Mild: n = 21 Severe: n = 67 |

CsA (50–400 mg/d) N = 51 BM (2–6 mg/day, 2 consecutive days per week) N = 37 |

NR | Response: > 50% hair regrowth | NR |

Response Overall: CsA: 28/51 (55%) BM 14/37 (38%) Relapse after EOT: CsA: 2/51 (4%) BM: 1 (3%) |

AE rates CsA: 29/51 (57%) BM: 27/37 (73%) AEs occurring in ≥ 5% pt: gastrointestinal symptoms, hypertrichosis, hypertension, weight gain, headache/dizziness, facial edema, acne, skin atrophy Nephrotoxicity reported in 3 pt receiving CsA |

| Shapiro et al. [40] | Non-randomized | Chronic severe AA: ≥ 95% scalp hair loss (AU, preuniversalis, AT) | N = 8 | CsA (5 mg/kg/d) and prednisone (5 mg/d) | Mean 7.5 Yr | > 75% hair regrowth | 24 Wk |

> 75% hair regrowth: 2/8 (25%) Relapse after EOT 2/2 (100%) |

‘Significant’ AEs in 4 patients included generalized edema, hypertension, abnormal liver function, abnormal lipid levels, hypertrichosis AE-related discontinuations: n = 3 |

All drugs administered orally unless otherwise mentioned

AA alopecia areata, AE adverse event, AT alopecia totalis, AU alopecia universalis, BID twice daily, BM betamethasone, CsA cyclosporine A, d days(s), EB eyebrow, EL eyelash, EOT end of therapy, Mth month(s), N total number of patients, n = number of patients in the category, NR not reported, PBO placebo, pt patient(s), RCT randomized controlled trial, SALT severity of alopecia tool, SALT30 > 30% change in SALT score from BL, SAE serious AE, SLR systematic literature review, Yr year(s)

†Including primary hair regrowth endpoint (where specified); other hair regrowth endpoints focus on SALT50 and eyebrow and eyelash regrowth and relapse, where reported

‡Definition of severity class not available

Table 6.

Summary of category 2 methotrexate studies included in the SLR

| Study | Study type | Baseline severity | Sample size (completers) | Treatments | Duration of disease | Response assessment(s)† | Response assessment period | Main efficacy findings | Tolerability/safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category 2: non-randomized trials, observational studies, RCT without PBO | |||||||||

| Alsufyani et al. [41] | Retrospective | AA: multifocal, AT, AU, diffuse |

N = 28 Multifocal: n = 14 AT: n = 2 AU: n = 9 Diffuse: n = 3 |

MTX (10–25 mg per Wk) N = 9 MTX (10–25 mg per Wk) + systemic CS: 20–30 mg/d N = 19 |

Median 5 Yr (range 0.4–42) |

Hair regrowth: 0–25% regrowth 26–50% regrowth 51–75% regrowth 76–99% regrowth 100% regrowth |

NR FU: to 3–51 Mth |

MTX alone > 50% regrowth: 4/9 (44%) 100%: 1/9 (11%) MTX + CS > 50% regrowth: 15/19 (79%) 100%: 5/19 (26%) Relapse: 7/19 (37%) with > 50% regrowth |

AEs: nausea, epigastric pain, diarrhea, leucopenia, transaminase activity elevations |

| Asilian et al. [42] | RCT without PBO control |

Severe AA: Baseline SALT 100% |

N = 36 |

MTX (15 mg QW) N = 12 BM (3 mg/d, QW) N = 12 MTX + BM N = 12 |

4.5–6.4 (units NR) | Improvement in SALT score |

EOT: 6 Mth FU + 3 Mth |

Mean SALT score (BL/9 Mth) MTX: 100%/78% BM: 100%/74% MTX + BM: 100%/57% |

AEs: gastrointestinal symptoms |

| English and Heinisch [43] | Retrospective | AA: > 50% scalp hair loss, AT, AU | N = 31 |

MTX (15 or 20 mg QW) ± Prednisone: 1 mg/kg/d, 21 d |

NR | % Hair regrowth | Average 12 Mth |

Cosmetically acceptable hair regrowth: 8/31 (26%) Relapse mean 2.3 Mth after EOT: 7/8 (88%) |

NR |

| Firooz and Fouladi [44] | Non-randomized | Severe AA‡, AU, ophiasis |

N = 10 AU: n = 9 Ophiasis: n = 1 |

MTX (5 or 10 mg QW) + Prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/d |

Mean 8.1 Yr (range 0.5–15) |

Grade 1: regrowth of vellus hair Grade 2: regrowth of sparse pigmented terminal hair Grade 3: regrowth of terminal hair with patches of alopecia Grade 4: regrowth of terminal hair on scalp (success) |

NR FU: to mean 14.4 Mth (4–32) |

Grade 3: 2/10 (20%) Grade 4 (success): 8/10 (80%) Relapse: 4/8 (50%) |

AEs: acne, herpes, anemia, hypertension, weight gain, amenorrhea, muscle cramp |

| Joly et al. [45] | Retrospective | AT, AU | N = 22 |

MTX (15, 20, or 25 mg QW) for 9–18 Mth (N = 6) MTX (15, 20, or 25 mg QW) + PN (10 or 20 mg/d) for 9–18 Mth (N = 16) |

Mean 11.1 Yr (range 1–33) | Complete hair regrowth (total regrowth of terminal hair during treatment) |

NR FU: median EOT + 15 Mth (range 6–72) |

Complete hair regrowth MTX: 3/6 (50%) MTX + CS: 11/16 (69%) Relapse: 8/14 (57%) |

AEs: transient transaminase activity elevations, persistent nausea No severe AEs |

All drugs administered orally unless otherwise mentioned

AA, alopecia areata, AE, adverse event, AT, alopecia totalis, AU, alopecia universalis, BL, baseline, BM, betamethasone, CS, corticosteroid, d, day(s), EOT, end of therapy, FU, follow-up period, Mth, month(s), MTX, methotrexate, N, total number of patients, n = number of patients in the category, NR, not reported, PBO, placebo, QW, once a week, RCT, randomized controlled trial, SALT, severity of alopecia tool, SLR, systematic literature review; Wk, week(s), Yr, year(s)

†Including primary hair regrowth endpoint (where specified); other hair regrowth endpoints focus on SALT50 and eyebrow and eyelash regrowth and relapse, where reported

‡Definition of severity class not available

Table 7.

Summary of category 2 azathioprine studies included in the SLR

| Study | Study type | Baseline severity | Sample size (completers) | Treatments | Duration of disease | Response assessment(s)† | Response assessment period | Main efficacy findings | Tolerability/safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category 2: non-randomized trials, observational studies, RCT without PBO | |||||||||

| Vañó-Galván et al. [46] | Non-randomized | AU | N = 14 | Azathioprine 2.5 mg/kg/d for 1–36 Mth | Mean 24.5 Mth (range 8–72) |

Complete response: regrowth on ≥ 75% of scalp Partial response: regrowth on < 75% of scalp Persistent response: > 75% of regrowth > 6 Mth after EOT |

NR FU: Mean 18 Mth (range 6–30) |

Regrowth on ≥ 75% of scalp: 6/14 (43%) Regrowth on < 75% of scalp: 0/14 Persistent response: 4/14 (29%) |

AEs: elevated liver enzymes, pancreatitis (serious), bone marrow suppression (serious), diarrhea Treatment discontinuations: n = 4 |

†Including primary hair regrowth endpoint (where specified); other hair regrowth endpoints focus on SALT50 and eyebrow and eyelash regrowth and relapse, where reported

AE adverse event, AU alopecia universalis, d day, Mth month, FU follow-up period, N total number of patients, n = number of patients in the category, PBO placebo, RCT randomized controlled trial, SLR systematic literature review, Yr year(s)

Table 8.

Summary of category 1 and 2 JAK inhibitor studies included in the SLR

| Study | Study type | Baseline severity | Sample size (completers) | Treatments | Duration of disease | Response assessment(s)† | Response assessment period | Main efficacy findings | Tolerability/safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1: PBO-controlled RCT | |||||||||

| King et al. [47] (BRAVE-AA1) |

PBO-controlled RCT Phase 3 |

Severe AA: ≥ 50% scalp hair loss Mean SALT 84.7–86.8 |

N = 654 |

Bari (2, 4 mg QD) N = 184, 281 PBO N = 189 |

Mean 11.8–12.6 Yr |

Percentage with SALT score ≤ 20 (primary endpoint) Proportion with ClinRo EB ≥ 2 or EL ≥ 2 at BL achieving ClinRo EB (0, 1) or ClinRo EL (0, 1) with ≥ 2-point improvement SALT50 |

36 Wk |

SALT score ≤ 20 Bari 2 mg: 23% Bari 4 mg 39% PBO 6% P < 0.001 for each dose vs. PBO ClinRo EB (0, 1) Bari 2 mg: 22% Bari 4 mg 35% PBO 4% P < 0.001 for each dose vs. PBO ClinRo EL (0, 1) Bari 2 mg: 15% Bari 4 mg 36% PBO 4% P < 0.001 for Bari 4 mg vs. PBO SALT50 Bari 2 mg: 11% Bari 4 mg 22% PBO 5% P < 0.05 for each dose vs. PBO |

AE rates: Bari 2 mg 93/183 (51%) Bari 4 mg 167/280 (60%) PBO 97/189 (51%) AEs occurring in ≥ 5% pt: URI, headache, nasopharyngitis, acne, UTI, blood creatine increase SAEs: 2% of each treatment group |

|

King et al. [47] (BRAVE-AA2) |

PBO-controlled RCT Phase 3 |

Severe AA: ≥ 50% scalp hair loss Mean SALT 84.8–85.6 |

N = 546 |

Bari (2, 4 mg QD) N = 156, 234 PBO N = 156 |

Mean 11.8–13.1 Yr |

Percentage with SALT score ≤ 20 (primary endpoint) Proportion with ClinRo EB ≥ 2 or EL ≥ 2 at BL achieving ClinRo EB (0, 1) or ClinRo EL (0, 1) with ≥ 2-point improvement SALT50 |

36 Wk |

SALT score ≤ 20 Baricitinib 2 mg: 19% Baricitinib 4 mg 36% PBO 3% P < 0.001 for each dose vs. PBO ClinRo EB (0, 1) Bari 2 mg: 13% Bari 4 mg 39% PBO 6% P < 0.001 for Bari 4 mg vs. PBO ClinRo EL (0, 1) Bari 2 mg: 12% Bari 4 mg 37% PBO 7% P < 0.001 for Bari 4 mg vs. PBO SALT50 at Wk 12 Bari 2 mg: 12% Bari 4 mg 25% PBO 3% |

AE rates: Bari 2 mg 106/155 (68%) Bari 4 mg 154/233 (66%) PBO 97/154 (63%) AEs occurring in ≥ 5% pt: URI, headache, nasopharyngitis, acne, UTI, blood creatine increase |

| Mesinkovska et al. [48]a (BRAVE-AA1/AA2) |

PBO-controlled RCT Phase 3 subgroup analysis |

Severe AA Pt with/without atopic background Mean SALT 87.2/84.2 |

N = 1200 38% with an atopic background (defined by history of/ongoing atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, allergic asthma or allergic conjunctivitis) 62% with no atopic background |

Bari (2, 4 mg QD) PBO |

NR |

Percentage with SALT score ≤ 20 Proportion with ClinRo EB ≥ 2 or EL ≥ 2 at BL achieving ClinRo EB (0, 1) or ClinRo EL (0, 1) with ≥ 2-point improvement |

36 Wk |

Pt with/without atopic background SALT score ≤ 20 Bari 2 mg: 22%/19% Bari 4 mg 41%/30% PBO 2%/5% ClinRo EB (0, 1) Bari 2 mg: 19%/14% Bari 4 mg 38%/30% PBO 6%/2% P ≤ 0.002 for each dose vs. PBO ClinRo EL (0, 1) Bari 2 mg: 16%/10% Bari 4 mg 37%/32% PBO 6%/3% |

Safety profile similar to that in overall BRAVE-AA1/AA2 population Safety profile independent of atopic background |

| Taylor et al. [49]a (BRAVE-AA1/AA2) |

PBO-controlled RCT Phase 3 subgroup analysis |

Severe AA: SALT 50–94 Very severe AA: SALT 95–100 |

N = 1200 Severe: 47% Very severe:53% AU: 44% |

Bari (2, 4 mg QD) PBO |

NR | Percentage with SALT score ≤ 20 (primary endpoint) | 36 Wk |

SALT score ≤ 20 Severe AA Bari 2 mg: 33% Bari 4 mg 48% PBO 8% Very severe Bari 2 mg: 10% Bari 4 mg 21% PBO 1% AU Bari 2 mg: 20% Bari 4 mg 28% PBO 3% P < 0.001 for all doses vs. PBO in all subgroups |

NR |

| Senna et al. [50]a (BRAVE-AA1/AA2 phase III subgroup analysis) |

PBO-controlled RCT Phase 3 subgroup analysis |

AA (NR) |

N = NR Pt not achieving SALT ≤ 20 at 36 Wk |

Bari (2, 4 mg QD) PBO |

NR | Proportion with ClinRo EB ≥ 2 or EL ≥ 2 at BL not achieving SALT ≤ 20 achieving ClinRo EB (0, 1) or ClinRo EL (0, 1) with ≥ 2-point improvement | 36 Wk |

ClinRo EB (0, 1) Bari 2 mg: 10% (P < 0.01 vs. PBO) Bari 4 mg 20% (P < 0.001 vs. PBO) PBO 4% ClinRo EL (0, 1) Bari 2 mg: 9% Bari 4 mg 23% (P < 0.001 vs. PBO) PBO 4% |

NR |

|

King et al. [51] (BRAVE-AA1) |

PBO-controlled RCT Phase 2 |

Severe AA: ≥ 50% scalp hair loss Mean SALT 83.4–90.0 |

N = 110 |

Bari (1, 2, 4 mg QD) (N = 28, 27, 27) PBO N = 28 |

Mean 12–17 Yr |

Percentage with SALT score ≤ 20 (primary endpoint) Proportion with ClinRo EB ≥ 2 or EL ≥ 2 at BL achieving ClinRo EB (0, 1) or ClinRo EL (0, 1) with ≥ 2-point improvement SALT50 |

36 Wk |

SALT score ≤ 20 Bari 2 mg 33.3% (P = 0.016 vs. PBO) Bari 4 mg 51.9% (P = 0.001 vs. PBO) PBO 3.6% ClinRo EB (0, 1) Bari 2 mg: 29% Bari 4 mg 39% PBO 4% P < 0.05 for each dose vs. PBO ClinRo EL (0, 1) Bari 2 mg: 40% Bari 4 mg 60% PBO 6% P < 0.05 for Bari 4 mg vs. PBO SALT50 Bari 2 mg: 48% Bari 4 mg: 67% PBO: 4% P ≤ 0.01 for both doses vs. PBO |

TEAE rates Bari 2 mg: 19/27 (70%) Bari 4 mg: 21/27 (78%) PBO: 17/28 (61%) Most frequent TEAEs: URI, acne, nausea No SAEs or deaths reported |

|

King et al. [52] (ALLEGRO) |

PBO-controlled RCT Phase 2a |

AA with ≥ 50% scalp hair loss Mean SALT 86.4–89.4) |

N = 142 |

Ritle (200 mg QD for 4 Wk, 50 mg QD for 20 Wk) N = 48 Brepo (60 mg QD for 4 Wk, 30 mg QD for 20 Wk) N = 47 PBO N = 47 |

Median 4.8–8.4 Yr |

CFB in SALT (primary endpoint) Proportion achieving ≥ 1-grade improvement in EB/EL assessment scale score (0, none to 3, normal) SALT50 |

24 Wk |

Least-squares mean difference from PBO in SALT score CFB Ritle: 31.1 Brepo: 49.2 (P < 0.0001 for both vs. PBO) ≥ 1-grade improvement in EB score Ritle: 21/41 (51%) Brepo: 28/39 (72%) PBO: 6/40 (15%) ≥ 1-grade improvement in EL score Ritle: 22/37 (60%) Brepo: 29/36 (81%) PBO: 5/35 (14%) SALT50 Ritle: 40% Brepo: 53% PBO: 2% |

AEs Ritle: 32/48 (67%) Brepo: 36/47 (77%) PBO: 35/47 (74%) AEs occurring in ≥ 5% pt: URI, nasopharyngitis, headache, acne, nausea SAEs: rhabdomyolysis (N = 2) with Brepo |

| King et al. [53] |

PBO-controlled RCT Phase 2 |

Moderate-to-severe AA: ≥ 50% scalp hair loss Mean SALT 87.9 |

N = 149 |

Deuru (4 mg BID) N = 30 Deuru (8 mg BID) N = 38 Deuru (12 mg BID) N = 37 PBO N = 44 |

Duration of current episode: mean 4.2 Yr | SALT50 (primary endpoint) | 24 Wk |

SALT50 Deuru 4 mg: 21% Deuru 8 mg: 47% Deuru 12 mg: 58% PBO: 9% P < 0.001 vs. PBO for 8-mg and 12-mg groups) |

AE rates Deuru 4 mg 25/29 (86%) Deuru 8 mg 31/38 (82%) Deuru 12 mg 30/36 (83%) PBO 31/44 (70.5%) AEs occurring in ≥ 10% pt: headache, nasopharyngitis, acne, URI, nausea, cough, folliculitis, increased creatinine phosphokinase, diarrhea, oropharyngeal pain |

| Category 2: non-randomized trials, observational studies, RCT without PBO | |||||||||

| AlMarzoug et al. [54]b | Non-randomized |

AA‡, AT, AU Baseline SALT 76.8 (n = 56) |

N = 65 (N = 45) |

Tofa (5 mg BID) | 9.8 Yr |

SALT50 SALT5–50 |

6 Mth |

SALT50: 28/45 (62%) SALT5–50: 17/45 (38%) |

AEs NR |

| Almutairi et al. [55] | RCT without PBO control |

Severe AA: severe multifocal alopecia (> 30% scalp hair loss), AT, AU Median SALT (99.6–99.8) (range 40.4–100 |

N = 80 (N = 75) AA: n = 33 AT: n = 25 AU: n = 17 |

Tofa (5 mg BID) N = 40 Ruxo (20 mg BID) N = 40 |

Mean 29.6–31.4 Mth |

SALT0–24 SALT25–49 SALT50–74 SALT75–99 SALT100 |

6 Mth |

SALT75 Tofa: 24/37 (65%) Ruxo: 26/38 (68%) SALT50 Tofa: 29/37 (78%) Ruxo: 32/38 (84%) Relapse (> 25% hair loss): Tofa: 26/37 (70%) Ruxo: 28/38 (74%) |

AEs occurring in ≥ 5% pt with either JAK inhibitor: leukopenia, increased transaminase activity, increased triglycerides, URIs, UTIs, zoster, folliculitis, genital warts, headache, fatigue, weight gain No discontinuations due to AEs |

| Chen et al. [56] | Non-randomized trial |

Severe AA: > 50% scalp hair loss SALT 52.2–100.0) |

N = 6 (N = 5) |

Tofa (5–10 mg QD) | Duration of current episode: 1.5–12 Yr | SALT50 | 6 Mth | SALT50: 60% |

AEs NR No SAEs |

| Cheng et al. [57] | Retrospective |

Severe AA: AT, AU SALT 50–100 |

N = 11 (N = 10) |

Tofa (5 mg QD to 11 mg extended release BID) ± intralesional triamcinolone | Mean 5.6 Yr | SALT score ≤ 5 | PRTIR |

SALT score ≤ 5: 5/10 (3 receiving concomitant triamcinolone) Relapse after EOT: 5/5 |

AEs: lipid abnormalities, weight gain, gastrointestinal symptoms, acne, joint pain, multiple sclerosis |

| Dincer Rota et al. [58] | Retrospective |

AA, AU SALT 45–100 |

N = 13 AA: n = 3 AU: n = 10 |

Tofa (≤ 10 mg/d) | Range 3–26 Yr |

SALT1–10 SALT10–75 SALT76–100 |

NR |

Response SALT1–10: 1/13 (8%) SALT10–75: 0/13 (0%) SALT76–100: 7/13 (54%) Relapse: 5/8 |

AEs: acne, oily skin transaminase activity elevations |

| Hogan et al. [59] | Retrospective |

Severe AA** Mean SALT 88 (range 50–100) |

N = 20 AA: n = 2 AT: n = 4 AU: n = 14 |

Tofa (5 mg BID up to 25 mg/d) | Duration of current episode: mean 2.4 Yr |

SALT50 SALT90 |

3 Mth |

SALT50: 11/20 (55%) SALT90: 5/20 (25%) |

AEs: hypercholesterolemia, URI, transient transaminase elevations, zoster, morbilliform eruption and peripheral edema, palpitations, leukopenia, acute kidney injury |

| Ibrahim et al. [60] | Retrospective |

AA Mean SALT 92.7 (range 71.6–100) |

N = 13 AA: n = 4 AT: n = 2 AU: n = 7 |

Tofa (5 mg BID) | Mean 18 Yr | SALT50 | NR | SALT50: 7/13 (54%) | AEs: lipid and liver abnormalities, morbilliform eruption, peripheral edema |

| Jabbari et al. [61] | Non-randomized | Moderate to severe AA SALT46–100 |

N = 12 AA: n = 7, AT, AU: n = 5 |

Tofa (5 to 10 mg/d) | Range 1–34 Yr | SALT50 |

EOT (range 6–18 Mth) FU: EOT + 6 Mth |

SALT50: 8/12 (67%) Relapse after EOT: 6/7 (1 responding patient continued tx outside the study) |

AEs: URI, increased bowel movement frequency, blood on urinalysis, loose stools, acne, weight gain, asymptomatic bacteriuria, hypertensive urgency, bloating, constipation, dizziness, headache, neuropathic pain, vaginal spotting, conjunctivitis, urinary retention, transaminitis |

| Kennedy Crispin et al. [62] | Non-randomized | Severe AA: AA with ≥ 50% scalp hair loss, AT, AU |

N = 70 (N = 66) AA: n = 11 Ophiasis: n = 3 AT: n = 6 AU: n = 46 |

Tofa (5 mg BID) | Duration of current episode: median 5 Yr |

SALT50 SALT5–50 |

3 Mth |

SALT50: 21/66 (32%) SALT5–50: 21/66 (32%) |

AEs occurring in ≥ 5% pt: URI, headache, abdominal pain, acne, diarrhea, fatigue |

| Kerkemeyer et al. [63] | Retrospective |

AA of the beard‡ Mean SALT 62 |

N = 45 ≥ 1 patches on scalp:‡ n = 19 Diffuse AA:‡ n = 8 AT: n = 4 AU: n = 14 |

Tofa (mean dose 7.2 mg) | Mean 61.2 Mth (of beard AA) |

Beard regrowth: none, partial, or complete (assessed by independent observer evaluation of photographs) Mean SALT |

5–28 Mth (mean 16 Mth) |

Beard regrowth: Complete regrowth: 10/45 (22%) Partial regrowth: 19/45 (42%) No regrowth: 16/45 (36%) Mean SALT at EOT: 41.7 |

AEs: URIs, elevated liver transaminases, fatigue, acne No SAEs |

| Liu et al. [64] | Retrospective | Severe AA: ≥ 40% scalp hair loss, AT, AU (scalp hair loss ≥ 90%) |

N = 90 (N = 65) |

Tofa (5–10 mg BID) ± prednisone 300 mg QM for 3 doses | Median 18 Yr (range 2–54 Yr) |

SALT90 SALT51–90 SALT6–50 |

EOT (median 7–15 Mth) |

SALT90: 13/65 (20%) SALT51–90: 25/65 (38.4%) SALT6–50: 12/65 (18.5%) |

AEs occurring in ≥ 5% pt: URI, headache, acne, fatigue, weight gain, hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, LDL elevations No SAEs |

| Mackay-Wiggan et al. [65] | Non-randomized |

Moderate-to-severe AA‡ Mean SALT 65.63 |

N = 12 | Ruxo (20 mg BID) | NR | SALT50 |

6 Mth FU: EOT + 3 Mth |

SALT50: 9/12 (75%) Relapse after EOT: 3/9 |

AEs: minor skin infections, URI, UTI, mild pneumonia, conjunctival hemorrhage following surgery, mild gastrointestinal symptoms No SAEs |

| Park et al. [66] | Retrospective |

Moderate-to-severe AA: > 30% hair loss Median SALT 99.5 (range 30.4–100) |

N = 32 AA N = 11 AT N = 10 AU N = 11 |

Tofa (5–10 mg BID) | Median 8 Yr (range 1–35) |

SALT50 SALT90 |

EOT (median 7.5 Mth (range 4–17) |

SALT50: 18/32 (56%) SALT90: 9/32 (28%) Relapse after EOT: 5/18 |

AEs NR No SAEs |

| Serdaroğlu et al. [67] | Retrospective | AA > 40% scalp hair loss, AT, AU |

N = 63 AA N = 14 AT N = 3 AU N = 46 |

Tofa (5 mg BID) | Median 7 Yr (range 1–40) |

SALT50 SALT90 |

NR |

SALT50: 52/63 (83%) SALT90: 25/63 (40%) |

AEs: hyperseborrhea, URI, acne No SAEs |

| Shin et al. [68] | Retrospective |

AT: > 80% scalp hair loss AU: > 80% scalp hair loss with total body hair loss SALT 98.1–100 |

N = 74 |

Tofa (5 mg BID) N = 18 Steroid ± CsA, N = 26 DPCP N = 30 |

Median 5–8 Yr (range 1–25) |

SALT50 SALT90 |

6 Mth |

SALT50 Tofa: 8/18 (44%) Steroid ± CsA: 9/24 (38%) DPCP: 3/27 (11.1%) SALT90 Tofa: 2/18 (11%) Steroid ± CsA: 2/24 (8%) DPCP: 0/27 (0%) |

AE rates Tofa 6/18 (33%) Steroid ± CsA 19/26 (73%) DPCP 10/30 (33%) AEs occurring in > 5 pt: abdominal discomfort, acneiform eruption, severe eczema Discontinuations due to AEs Tofa 0/18 (0%) Steroid ± CsA 6/26 (23%) DPCP 3/30 (10%) |

| Wambier et al. [69] | Retrospective |

Severe AA‡ SALT 66–100 |

N = 12 | Tofa (5–10 mg BID) + Minoxidil (2.5 mg QD or BID) | Duration of current episode: median 1–7 Yr; pt with a current episode > 10 Yr duration excluded |

SALT75 SALT11-74 |

3 Mth |

SALT75: 8/12 (67%) SALT11-74: 4/12 (33%) |

AEs included: hypertrichosis, acne |

| Zhang et al. [70] | Retrospective |

Moderate-to-severe AA (SALT ≥ 25) Median SALT 50–60 |

N = 61 Moderate AA: n = 23 Severe AA: n = 38 |

Tofa (5–10 mg BID) (N = 20) Tofa (5–10 mg BID) + steroids (N = 23) Steroids alone (N = 18) |

Median 1.8–9.7 Yr | SALT50 (primary endpoint) | NR |

SALT50 Tofa: 12/20 (60%) Tofa + steroids: 18/23 (78%) Steroids: 12/18 (67%) |

AE rates Tofa: 7/20 (35%) Tofa + steroids: 13/23 (57%) Steroids: 12/18 (67%) AEs occurring in ≥ 5 pt: acneiform eruption, weight gain |

All drugs administered orally unless otherwise mentioned

AA alopecia areata, AE adverse event, AT alopecia totalis, AU alopecia universalis, Bari baricitinib, BID twice daily, BL baseline, Brepo brepocitinib, CFB change from BL, ClinRo clinician-reported outcome CsA cyclosporine A, d day(s), Deuru deuruxolitinib, DPCP diphenylcyclopropenone, EB eyebrow, EL Eyelash, EOT end of therapy, FU follow-up period, JAK Janus kinase, Mth month(s), N total number of patients, n number of patients in the category, NR not reported, PBO placebo, PRTIR patient-reported time to initial response, pt patient(s), QD once daily, QM once monthly, RCT randomized controlled trial, Ritle ritlecitinib, Ruxo ruxolitinib, SAE serious adverse event, SALT severity of alopecia tool, SALTX > X% change in SALT score from BL, SLR systematic literature review, Tofa tofacitinib, tx therapy, URT upper respiratory tract infection, UTI urinary tract infection, Wk week(s), Yr year(s)

aSubgroup analyses of BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2 were presented in abstract form

bAlMarzoug (2021) was an epub with an accompanying publication from 2022. As the two citations are effectively duplicates, we excluded the 2022 version as it did not report any different information

†Including primary hair regrowth endpoint (where specified); other hair regrowth endpoints focus on SALT50 and eyebrow and eyelash regrowth and relapse, where reported

‡Definition of severity class not available

Systemic Corticosteroids

Efficacy

One category 1 study was identified (Table 3) comparing 3 months of weekly oral prednisolone pulse therapy and placebo in 43 patients with severe AA [18]. Severe AA was defined as ≥ 40% scalp hair loss or > 10 patches scattered over the scalp and body. Results were reported only for the 36 study completers. After 3 months, 8 of 20 (40%) patients on corticosteroids achieved > 30% hair regrowth, compared with none of those receiving placebo (p < 0.03). Only two patients in the corticosteroid group achieved > 60% regrowth. At the end of a 3-month post-treatment follow-up, two of the eight responders had relapsed.

Four category 2 studies were identified. Treatment protocols varied across studies, and sample sizes ranged from 31 to 89 patients. In studies that included patients with AAs of varying severity, response rates to corticosteroid therapy were lower in those with extensive hair loss [20, 22]. In one study that reported data from 31 patients with alopecia totalis (AT) or universalis (AU), 22 (71%) achieved ≥ 75% scalp hair regrowth after 4 months of oral dexamethasone [21]; persistent response (defined as the maintenance of > 75% regrowth for at least 3 months after therapy withdrawal) was observed for 10 patients. Across studies, relapse rates after discontinuation of corticosteroids ranged from 25 to 100% [18, 20].

Tolerability

Corticosteroid therapy was associated with a higher rate of adverse events (AEs) versus placebo (55% vs. 13%) [18]. AEs reported with corticosteroids across the five studies most commonly included acne, weight gain, gastrointestinal symptoms, dysmenorrhea, striae, myalgia, and edema [18–22].

Topical Immunotherapy

Efficacy

No placebo-controlled studies were identified. Data were extracted from 13 category 2 studies mostly involving diphenylcyclopropenone (12 studies), with initial sample sizes varying from 10 to 64 [23–35]. Overall, response varied widely across the studies, with rates of complete response (where reported) ranging from 0 to 52% in study completers (Table 4). Baseline severity of disease and definition of response were not consistent across studies. Efficacy was lower in patients with AT/AU than in those with less severe scalp hair loss in one study [25], but this was not seen in another study [28]. Rates of relapse after treatment discontinuation ranged from 22 to 69% [24–26, 29, 32].

Tolerability

Notable AEs across studies included lymphadenopathy, contact dermatitis of the face or neck, generalized dermatitis, eczema, pruritus, hyperpigmentation, and urticaria (Table 4). The rate of AE-related discontinuations ranged from 6 to 25% in studies that reported these data [24, 26–28, 31, 33, 34].

Cyclosporine A

Efficacy

Two records reported the interim data [71] and final data [36] from a single RCT conducted in 36 adults with moderate-to-severe AA who received oral cyclosporine A 4 mg/kg/day or placebo for 3 months (Table 5). The final analysis performed on data from 32 patients found no statistically significant difference for the primary endpoint (50% improvement in Severity of Alopecia Tool score; SALT50) and most secondary endpoints after 3 months of treatment. Data from four category 2 studies were also extracted (Table 5). Sample sizes ranged from 6 to 88. Cyclosporine A was mostly used in monotherapy.

In a prospective study conducted in 15 patients with severe AA (> 50% scalp hair loss), five (33%) patients achieved ≥ 75% scalp hair regrowth over treatment durations ranging from 1 to 12 months [37]. In a retrospective study including 51 patients with mild to severe AA treated with cyclosporine A, 55% of patients achieved > 50% hair regrowth [39]. A reported relapse after treatment discontinuation occurred in 2 patients, with an additional 20 showing improved but sustained hair loss, from the total treated population of 51 patients (initial responses of individual patients were not described) in one study [39] and both responding patients in another [40].

Tolerability

In the category 1 study, 83% of patients in both the cyclosporine A and placebo groups reported at least one AE [36]. AEs reported at a higher rate with cyclosporine A than with placebo included urinary tract infection, musculoskeletal and respiratory disorders, gastrointestinal symptoms, hypertrichosis, hypertension, and hirsutism [36]. Similar AE profiles were reported across the category 2 studies (Table 5) [37–40].

Methotrexate

Efficacy

No placebo-controlled RCT was identified. One RCT was conducted in 36 patients with severe AA (SALT score 100%) randomized to receive oral methotrexate, oral betamethasone pulse therapy, or both combined [42]. At month 6 (end of treatment), the mean SALT score was 78% for methotrexate, 63% for betamethasone, and 62% for the combination; mean SALT score was unchanged 3 months after methotrexate treatment completion (Table 6). Across-group comparisons were not significant, and no patient achieved complete scalp hair regrowth. In the four remaining studies, methotrexate was mostly used in combination with systemic corticosteroids. Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 31, and, where provided, baseline severity ranged from > 50% to complete hair loss. Relapse rates ranged from 37 to 88% [41, 43–45]. Relapses were sometimes observed on treatment [41, 43], but mostly occurred when methotrexate and/or concomitant systemic corticosteroids were either tapered or discontinued [41, 43, 45].

Tolerability

Across studies, reported AEs included gastrointestinal complaints, leucopenia, and increases in transaminase activity (Table 6) [41–45].

Azathioprine

Efficacy

No placebo-controlled RCT was identified (Table 7). A prospective study provided data on 14 patients with AU treated with azathioprine. Six patients achieved ≥ 75% scalp hair regrowth and two relapsed after the withdrawal of azathioprine [46].

Tolerability

AEs were reported in five patients and included diarrhea, elevation of liver enzymes, pancreatitis, and bone marrow suppression (Table 7). Treatment was discontinued in four patients.

JAK Inhibitors

Efficacy

Seven category 1 records reporting data from five placebo-controlled RCTs were identified (Table 8).

King et al. [47] reported the outcomes of two phase 3 double-blind, parallel-group RCTs (BRAVE-AA1, N = 654 and BRAVE-AA2, N = 546). In each study, adults with severe AA (≥ 50% scalp hair loss) were randomized to receive baricitinib 4 mg or 2 mg or placebo. The primary outcome (proportion of patients achieving a SALT score ≤ 20 at week 36) was achieved by each dose in both trials (p < 0.001 for each dose versus placebo) (Table 8). Significant results were observed for most secondary outcomes for baricitinib 4 mg, including the achievement of eyebrow and eyelash hair regrowth. When baricitinib 2 mg was considered, response rates were generally lower than with baricitinib 4 mg.

Subgroup analyses of these two trials were provided in three congress reports. These showed that the efficacy of baricitinib was not notably affected by an atopic background [48], was achieved in patients with various degrees of scalp hair loss [49], and that benefit was obtained with continued treatment in patients without an initial response (SALT score > 20 at week 36) [50] (Table 8). Findings of the phase 2 portion of BRAVE-AA1, conducted in 110 adult patients with severe AA (≥ 50% scalp hair loss), support the phase 3 findings [51].

Another phase 2 randomized, placebo-controlled trial, ALLEGRO [52], assessed two unlicensed JAK inhibitors, ritlecitinib (a JAK3/tyrosine kinase expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma [TEC] family kinase irreversible inhibitor) and brepocitinib (an inhibitor of tyrosine kinase 2 and JAK1), for the treatment of patients with AA (≥ 50% scalp hair loss). Significantly better results were observed for both JAK inhibitors compared with placebo (both p < 0.0001) for the primary endpoint (change from baseline in SALT score at week 24). Numerical improvements versus placebo were also seen with both drugs across several additional outcome measures related to scalp, eyebrow, and eyelash regrowth.

King et al. [53] reported a phase 2 randomized, placebo-controlled trial of deuruxolitinib, an oral JAK1/2 inhibitor, in adults with moderate-to-severe AA (≥ 50% scalp hair loss). Patients were randomized to receive deuruxolitinib (4 mg, 8 mg, or 12 mg twice daily) or placebo for 24 weeks. There was a dose-dependent increase in the percentage of patients achieving SALT50 at week 24 (primary endpoint), with statistical significance versus placebo (p < 0.001) for the 8 mg and 12 mg groups (Table 8).

A total of 17 category 2 studies were identified. Sample size ranged from 6 to 90 patients and baseline severity of hair loss ranged from > 30% scalp hair loss to AT/AU. In these studies, JAK inhibitors were mostly used in monotherapy, with tofacitinib (a JAK1/3 inhibitor) the most studied.

Most patients experienced a relapse of hair loss after tofacitinib discontinuation in category 2 studies; data concerning relapse have not been reported for the other JAK inhibitors (Table 8).

Tolerability

AEs occurring at a higher frequency with JAK inhibitors than with placebo included upper respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, nasopharyngitis, acne, blood creatine phosphokinase and transaminase increases, headache, and nausea. Across studies, AEs were mostly mild or moderate in severity (Table 8).

Quality Assessment

Major concerns for potential sources of bias were identified, especially related to blinding, the distribution of patients, and intention to treat. Only the category 1 BRAVE-AA1 phase 2 [51] and BRAVE-AA1/AA2 phase 3 studies of baricitinib [47], the phase 2 study with ritlecitinib and brepocitinib [52], and the Lai study [36] investigating the efficacy of cyclosporine A mentioned both the methods used for randomization and allocation concealment. Overall, except for these placebo-controlled trials, the studies from extracted records were considered to be of moderate-to-poor quality. Table 9 includes details of the quality assessment of the RCTs (placebo controlled and active controlled) identified and included in the SLR (see Table S3 for the quality assessment of the non-randomized included trials).

Table 9.

Critical appraisal of the included randomized trials

| Study | Was the method used to generate random allocations adequate? | Was the allocation adequately concealed? | Were the groups similar at the outset of the study in terms of prognostic factors? | Were the care providers, participants, and outcome assessors blind to treatment allocation? | Were there any unexpected imbalances in dropouts between groups? | Is there any evidence to suggest that the authors measured more outcomes than they reported? | Did the analysis include an intention-to-treat analysis? If so, was this appropriate and were appropriate methods used to account for missing data? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel-group studies | |||||||

| Al Bazzal et al. [23]† | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear | No | Yes |

| Almutairi et al. [55]† | Unclear | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Asilian et al. [42]† | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Ghandi et al. [27]† | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | No | No | No |

| Kar et al. [18] | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| King et al. [47] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| King et al. [51] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| King et al. [52] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Lai et al. [36] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Rocha et al. [30]† | Unclear | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| King et al. [53] | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Tiwary et al. [35]† | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | No | No |

| Split-scalp | |||||||

| Shapiro et al. [31] | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | No | No |

| Thuangtong et al. [33] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No |

| Thuangtong et al. [34]† | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | No |

†Study was a randomized trial with no placebo control

Discussion

Here, we summarize the available evidence pertaining to the clinical effects of treatments used in AA, with a focus on interventions recommended for use in adult patients with moderate-to-severe forms of AA. Among the 53 records retained for data extraction, only 9 reported data from 7 placebo-controlled RCTs (category 1). Five of these studies assessed one or several JAK inhibitors in adult patients with at least 50% scalp hair loss and demonstrated a consistent benefit over placebo across various clinical outcomes [47, 51–53]. The other two studies assessed oral prednisolone and cyclosporine A. Oral prednisolone pulse therapy was compared to placebo in a small monocentric trial, but the findings were not conclusive [18]. In the other trial, which was also small and monocentric, oral cyclosporine A was not superior to placebo after 3 months of therapy [36, 70]. Overall, the results in terms of hair regrowth varied widely across the remaining identified studies and were generally low for patients with moderate-to-severe AA. Relapses were commonly observed during treatment and upon discontinuation. AEs were generally consistent with the known safety profile of each intervention.

Our results align with those of a Cochrane review performed in 2008, which focused on RCTs evaluating the effectiveness of both topical and systemic interventions for AA, AT, and AU that were published prior to the introduction of JAK inhibitors [9]. The authors’ conclusions included that none of the interventions identified showed a significant treatment benefit in terms of hair growth when compared to placebo, that only a few treatments used for AA had been well evaluated in RCTs, and that most of these RCTs were small and had been reported poorly [9]. A more recent systematic review examining the effectiveness of systemic treatments for people with AA, AT, or AU also concluded that there was no specific systemic therapy that is supported by a robust body of evidence from RCTs [72].

A network meta-analysis (NMA) of RCTs comparing two or more AA treatments conducted in patients with AA of any severity and published prior to August 2019 included only three of the RCTs identified in the current SLR: the placebo-controlled RCTs by Kar et al. [18] for corticosteroids and Lai et al. [36] for cyclosporine A and the RCT comparing the JAK inhibitors ruxolitinib and tofacitinib (no placebo control) by Almutairi et al. [55]. In that NMA, the authors concluded that the highest treatment success rate was associated with pentoxifylline plus topical corticosteroids, followed by pentoxifylline alone [73]. Pentoxifylline is not currently recommended for the treatment of patients with AA; hence, only category 3 data were identified for this agent in the current SLR (see Table S2).

As part of the current SLR, we investigated whether the conduct of an NMA or indirect treatment comparison of the treatments used to manage adults with severe AA was possible using a feasibility assessment [74]. For the placebo-controlled trials, it would be statistically possible to conduct separate pairwise anchored indirect comparisons to compare the JAK inhibitor baricitinib with the oral immunosuppressant cyclosporine A and with the oral steroid prednisolone due to the use of a common placebo in the trials. However, such a comparison was not recommended due to several major limitations. The sample sizes in the cyclosporine and prednisolone trials were very small compared to the available data for baricitinib; hence, the results would be highly uncertain. In addition, complete data for potential prognostic factors and effect modifiers were not available. The remaining studies were uncontrolled, with small sample sizes and high heterogeneity between patient populations. Baseline characteristics and the timing of follow-up were not consistently reported, and outcome measures varied across studies. Unanchored indirect comparisons were not recommended due to the limited data and the strong assumptions that would be required for such an analysis [75]. An indirect comparison of individual JAK inhibitors was not performed as most are not available in clinical practice and the tofacitinib trials were predominantly non-randomized and/or retrospective.

Limitations/Strengths

The conclusions to be drawn regarding the efficacy and safety of treatments recommended for patients with moderate-to-severe AA are primarily limited by the excessive heterogeneity across the included records with respect to study design and population (severity, disease duration) and by the overall moderate-to-poor quality of the conduct and reporting of the studies.

The differing definitions for the severity of AA at baseline and the use of a wide range of response outcomes are also problematic. The SALT score is an objective, validated, and standardized tool recommended by experts for grading the extent and density of scalp hair loss in patients with AA in clinical trials [76, 77]. While SALT-based parameters were reported in the placebo-controlled RCTs identified for JAK inhibitors and cyclosporine A, most of the other studies used another method to assess percentage hair regrowth, often without providing any details on how the assessment was performed. This heterogeneity between studies prevented the conduct of a NMA of the available data.

Against these limitations, the strengths of our study should be taken into consideration. The broad scope of the SLR aimed to ensure the identification of the relevant evidence supporting the treatments for moderate-to-severe AA recommended in current guidelines. Additionally, the assessment of the quality of the included randomized and non-randomized studies using Cochrane and CRD checklists, respectively, means that the conclusions drawn can be considered robust.

Conclusion

The current management of patients with moderate-to-severe AA still relies on the use of treatments that have not been well evaluated in clinical trials. The most robust evidence identified supported the use of the EMA- and FDA-approved baricitinib, and other currently unapproved oral JAK inhibitors, in patients with severe AA.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Gill Gummer and Caroline Spencer (Rx Communications), funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design and the analysis of data for the work were performed by Erin Johansson. Interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content were done by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and the Rapid Service Fee were funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Alexander Egeberg has received research funding from Almirall, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, the Danish National Psoriasis Foundation, the Simon Spies Foundation, and the Kgl Hofbundtmager Aage Bang Foundation, and honoraria as a consultant and/or speaker from Amgen, AbbVie, Almirall, Leo Pharma, Zuellig Pharma Ltd., Galápagos NV, Sun Pharmaceuticals, Samsung Bioepis Co., Ltd., Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis, Union Therapeutics, Galderma, Dermavant, UCB, Mylan, Bristol Myers Squibb, McNeil Consumer Healthcare, Horizon Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Louise Linsell is an employee of Visible Analytics, Oxford, UK. Sergio Vañó-Galván is an advisor for Pfizer and Eli Lilly and Company. Erin Johansson, Frederick Durand, and Guanglei Yu are employees and minor shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Messenger AG, McKillop J, Farrant P, McDonagh AJ, Sladden M. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of alopecia areata 2012. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:916–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Simakou T, Butcher JP, Reid S, Henriquez FL. Alopecia areata: a multifactorial autoimmune condition. J Autoimmun. 2019;98:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pratt CH, King LE, Jr, Messenger AG, Christiano AM, Sundberg JP. Alopecia areata. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17011. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukuyama M, Ito T, Ohyama M. Alopecia areata: current understanding of the pathophysiology and update on therapeutic approaches, featuring the Japanese Dermatological Association guidelines. J Dermatol. 2022;49:19–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Delamere F. Interventions for alopecia areata. J Evid Base Med. 2009;2:62. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-5391.2009.01011_1.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S, Lee H, Lee CH, Lee WS. Comorbidities in alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:466–77.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abedini R, Hallaji F, Lajevardi V, Nasimi M, Khaledi MK, Tohidinik HR. Quality of life in mild and severe alopecia areata patients. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;4:91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torales J, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A, Almirón-Santacruz J, Barrios I, O'Higgins M, et al. Alopecia areata: a psychodermatological perspective. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:2318–2323. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]