Abstract

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are fermentative microorganisms and perform different roles in biotechnological processes, mainly in the food and pharmaceutical industries. Among the LAB, Lactobacillus acidophilus is a species that deserves to be highlighted for being used both in prophylaxis and in the treatment of pathologies. Most of the metabolites produced by this species are linked to the inhibition of pathogens. In this study, we utilized a pangenomic and metabolic annotation analysis using Roary and BlastKOALA, ML-based probiotic activity prediction with iProbiotic and whole-genome similarity using ANI to identify strains of L. acidophilus with potential probiotic activity. According to the results in BlastKOALA and iProbiotics, L. acidophilus NCTC 13721 had the greatest potential among the 64 strains tested, both in terms of its ability to be a Lactobacillus spp. probiotic, when in the amount of genes involved in the metabolism of organic acids and quorum sensing. In addition, DSM 20079 proved to be promising for prospecting new probiotic Lactobacillus from BlastKOALA analyses, as they presented similar results in the number of genes involved in the production of lactic acid, acetic acid, hydrogen peroxide, except for quorum sensing where the NCTC 13721 strain had 14 more genes. L. acidophilus NCTC 13721 and L. acidophilus La-5 strains showed greater ability to be Lactobacillus spp. probiotic capacity, showing 84.8% and 51.9% capacity in the iProbiotics tool, respectively. When analyzed in ANI, none of the evaluated strains showed genomic similarity with NCTC 13721. In contrast, the DSM 20079 strain showed genomic similarity with all evaluated strains except NCTC 13721. Furthermore, eight strains with characteristics with approximately 100% genomic similarity to La-5 were listed: S20_1, LA-5, FSI4, APC2845, LA-G80-111, DS1_1A, LA1, and BCRC 14065. Therefore, according to the findings in iProbiotics and BlastKoala, among the 64 strains evaluated, NCTC 13721 is the most promising strain to be used for future in vitro studies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-023-01139-3.

Keywords: Bioinformatics, Probiotics, Lactic acid bacteria, Lactobacillus, Lactic acid, Pangenome

Introduction

Probiotics are defined as live microorganisms that confer a health benefit on the host if administered in adequate amounts [1]. Among the various probiotics, species belonging to the previously known Lactobacillus genus represent a group of bacteria with heterogeneous characteristics, having the following classification: phylum Firmicutes, class Bacilli, order Lactobacillales, and family Lactobacillaceae [2]. They are non-spore-forming, catalase-negative, gram-positive, and facultatively anaerobic rods [3]. It is also important to point out that Lactobacillus can ferment carbohydrates into lactic acid in their primary metabolism, which characterizes them as lactic acid bacteria (LAB) [4]. These probiotic microorganisms inhabit the human gastrointestinal and vaginal microbiota and have been gaining prominence due to their beneficial effects on the health of the host, which can occur directly between cells or indirectly through their metabolites [5, 6]. Among the many protective effects of Lactobacillus spp. is the modulation of the intestinal microbiota and immune system, the intestinal barrier’s reinforcement, and the regulation of crucial pathways in epithelial cells [7].

Various L. acidophilus strains have already been described with probiotic properties [8]. This species contains important probiotics, as it acts in several functions related to the health of the host, mainly in inhibiting pathogenic microorganisms, regulating the intestinal epithelial barrier, and anti-inflammatory effect, increasing its use in the food and pharmaceutical area [9]. In addition, L. acidophilus stands out for having characteristics such as resistance to bile salts, low pH, good ability to adhere to human colon cells in cell culture, regulation of host immune responses, and promising in the prophylaxis and treatment of infections. Among its functional mechanisms, the current study has shown that L. acidophilus regulates the intestinal microbiota by decreasing pH and producing metabolites [8].

The fermentation process with LAB generates an accumulation of organic acids, having lactic acid as the principal end product of carbohydrate metabolism. The accumulation of this acid, with the consequent reduction in pH, is responsible for a broad-spectrum inhibitory activity for both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. When LAB is in the presence of oxygen, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is produced. On the other hand, superoxide anions in the presence of H2O2 form hydroxy radicals, which can lead to peroxidation of membrane lipids and an increase in the membrane. The bactericidal effect obtained from these metabolites is believed to result from the oxidizing effect on the bacterial cell, the destruction of nucleic acids, and cellular proteins [10].

Quorum sensing (QS) is the mechanism through which bacterial cells communicate between and within species after reaching a certain level of cell density [11]. Communication occurs through signaling by autoinducer molecules (AI) produced by cells. QS inhibition appears to be how probiotics modulate the intestinal system and lessen the harmful effects of pathogenic bacteria [12].

Given the need for a better understanding of probiotic strains, using bioinformatics tools is a viable alternative. Bioinformatics is an interdisciplinary area of knowledge that uses tools such as computer science, mathematics, and biology, to promote a greater understanding of biological data, benefiting biomedical research in several aspects to understand the relationship between genes and the system stimulus [13]. Studies on pangenomics have become a powerful tool, as genetic analysis and comparison can be helpful to explore and characterize a shared pattern among microorganisms, providing a better understanding of the function and evolution of genomes. Furthermore, researchers can evaluate specific genomic characteristics to determine and characterize a species with better performance in the production of a particular protein or metabolite, for example [14].

This work aimed to prospect, through bioinformatics, strains of L. acidophilus that have potential probiotic activity through pangenomic analysis and predictive models. In addition, we identified through bioinformatics the number of genes involved in the production of lactic acid, acetic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and quorum sensing related to probiotic activity.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition

Complete genome sequences of L. acidophilus strains were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) using the Datasets portal (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/). A total of 64 L. acidophilus records were retrieved, 13 complete genomes and 51 draft genomes. L. acidophilus phage records were excluded, along with records without a FASTA and GBFF (GenBank File Format) file available. Names, accession codes, completion levels, and references of the strains used in the present work are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Identification and access codes of the L. acidophilus strains used in the present study

| Strain | BioSample | BioProject | Code NCBI | Completion level | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCFM | SAMN02603047 | PRJNA82 | GCA_000011985.1 | Complete | [15] |

| FSI4 | SAMN03274004 | PRJNA271341 | GCA_000934625.1 | Complete | [16] |

| LA1 | SAMN05631052 | PRJNA340059 | GCA_002286215.1 | Complete | [17] |

| YT1 | SAMN08142761 | PRJNA421407 | GCA_003952845.1 | Complete | - |

| LA-G80-111 | SAMN15165794 | PRJNA638040 | GCA_013342945.1 | Complete | - |

| NC55 | SAMN23011956 | PRJNA779097 | GCA_020883435.1 | Complete | - |

| 5460 | SAMN24563600 | PRJNA793589 | GCA_021432145.1 | Complete | - |

| La-14 | SAMN02603216 | PRJNA196176 | GCF_000389675.2 | Complete | [18] |

| ATCC 53544 | SAMN07357495 | PRJNA394684 | GCF_002224305.1 | Complete | - |

| DSM 20079 | SAMN06606133 | PRJNA379350 | GCF_003047065.1 | Complete | - |

| HN017 | SAMN29766956 | PRJNA859117 | GCF_024397395.1 | Complete | - |

| LA-2 | SAMN29862208 | PRJNA860779 | GCF_024665075.1 | Complete | - |

| LA-5 | SAMN29862214 | PRJNA860779 | GCF_024665555.1 | Complete | - |

| NCTC13721 | SAMEA3881062 | PRJEB6403 | GCA_900452495.1 | Draft | - |

| KLDS 1.0901 | SAMN05949236 | PRJNA218564 | GCF_001868765.1 | Draft | [19, 20] |

| LA1063 | SAMN14422845 | PRJNA613973 | GCF_017009725.1 | Draft | [21] |

| LMG P-21904 | SAMN07187785 | PRJNA388854 | GCF_002914945.1 | Draft | - |

| BCRC 14065 | SAMN14363925 | PRJNA612162 | GCF_017009515.1 | Draft | [21] |

| BCRC 17008 | SAMN14371317 | PRJNA612399 | GCF_017009595.1 | Draft | [21] |

| BCRC 17481 | SAMN14371318 | PRJNA612401 | GCA_017009655.1 | Draft | [21] |

| NBRC 13951 | SAMD00046914 | PRJDB1353 | GCF_001591845.1 | Draft | - |

| La-5 | SAMN14401351 | PRJNA613347 | GCA_017009715.1 | Draft | [21] |

| CIRM-BIA 442 | SAMEA2272381 | PRJEB1530 | GCF_000442865.1 | Draft | - |

| ATCC 4356 | SAMN03105773 | PRJNA263693 | GCA_000786395.1 | Draft | [22] |

| BCRC 16092 | SAMN14363928 | PRJNA612164 | GCA_017009575.1 | Draft | [21] |

| BCRC 16099 | SAMN14371312 | PRJNA612394 | GCA_017009605.1 | Draft | [21] |

| NBIMCC 8242 (180) | SAMN23827470 | PRJNA787572 | GCF_021229035.1 | Draft | - |

| DSM 20242 | SAMEA2272474 | PRJEB1533 | GCA_000442825.1 | Draft | - |

| QAULAN51 | SAMN20114166 | PRJNA744373 | GCA_022509485.1 | Draft | - |

| s-4 | SAMN15579838 | PRJNA647640 | GCF_013867555.1 | Draft | - |

| BCRC 14079 | SAMN14363926 | PRJNA612163 | GCF_017009475.1 | Draft | [21] |

| CIRM-BIA 445 | SAMEA2272655 | PRJEB1531 | GCA_000469765.1 | Draft | - |

| s-13 | SAMN15579847 | PRJNA647640 | GCF_013867605.1 | Draft | - |

| BCRC 80064 | SAMN14371424 | PRJNA612405 | GCF_017009695.1 | Draft | [21] |

| L3_101_000G1_dasL3_101_000G1_metabat.metabat.48 | SAMN17800807 | PRJNA698986 | GCA_018367455.1 | Draft | [23] |

| BCRC 17486 | SAMN14371319 | PRJNA612404 | GCF_017009585.1 | Draft | [21] |

| PNW3 | SAMN10979321 | PRJNA504734 | GCA_004348805.1 | Draft | - |

| MGYG-HGUT-02379 | SAMEA5851883 | PRJEB33885 | GCF_902386525.1 | Draft | - |

| DSM 9126 | SAMEA2272239 | PRJEB1839 | GCA_000469745.1 | Draft | - |

| LA_AVK2 | SAMN13198280 | PRJNA587688 | GCF_009741835.1 | Draft | - |

| LA_AVK1 | SAMN13198235 | PRJNA587652 | GCF_009742735.1 | Draft | - |

| BCRC 12255 | SAMN14363914 | PRJNA612160 | GCF_017009485.1 | Draft | [21] |

| DS9_1A | SAMN05583792 | PRJNA336518 | GCF_003061925.1 | Draft | [24] |

| DS5_1A | SAMN05583788 | PRJNA336518 | GCF_003061985.1 | Draft | [24] |

| BIO6307 | SAMN12856535 | PRJNA574342 | GCF_008868625.1 | Draft | - |

| DSM 20079 | SAMN02369388 | PRJNA222257 | GCA_001433895.1 | Draft | [25] |

| DS24_1 | SAMN06464090 | PRJNA336518 | GCA_003053135.1 | Draft | [24] |

| DS8_1A | SAMN05583791 | PRJNA336518 | GCA_003061945.1 | Draft | [24] |

| DS10_1A | SAMN05583778 | PRJNA336518 | GCA_003053245.1 | Draft | [24] |

| CIP 76.13 | SAMEA2272342 | PRJEB1532 | GCF_000469705.1 | Draft | - |

| DS11_1A | SAMN05583779 | PRJNA336518 | GCF_003062025.1 | Draft | [24] |

| UBLA-34 | SAMN10136005 | PRJNA493554 | GCF_003641085.1 | Draft | - |

| DS20_1 | SAMN06464087 | PRJNA336518 | GCA_003061885.1 | Draft | [24] |

| DS1_1A | SAMN05583775 | PRJNA336518 | GCA_003062045.1 | Draft | [24] |

| DS13_1B | SAMN05583783 | PRJNA336518 | GCF_003061905.1 | Draft | [24] |

| ATCC 4796 | SAMN00001471 | PRJNA31477 | GCA_000159715.1 | Draft | - |

| DS13_1A | SAMN05583782 | PRJNA336518 | GCF_003061965.1 | Draft | [24] |

| APC2845 | SAMN13342918 | PRJNA590940 | GCA_017695935.1 | Draft | - |

| LA-G80 | SAMN18679498 | PRJNA720781 | GCF_018252545.1 | Draft | - |

| PB2021-BA04 | SAMN18297454 | PRJNA714263 | GCA_023093425.1 | Draft | - |

| P2 | SAMN07665576 | PRJNA407882 | GCF_002406675.1 | Draft | - |

| WG-LB-IV | SAMN04628015 | PRJNA317797 | GCF_001639165.1 | Draft | - |

| DS2_1A | SAMN05583785 | PRJNA336518 | GCA_003062005.1 | Draft | [24] |

| CFH | SAMN02401339 | PRJNA227335 | GCF_000497795.1 | Draft | - |

Pangenome analysis

After selecting the Lactobacillus strains, the Roary v3.13 software—native to Linux— [26] was used, which receives GFF3 files (General Feature Formats version 3) as input. The present study converted GenBank data to the GFF3 format using BioPerl (https://bioperl.org/). It was established as part of the core gene, the genes present in at least 95% of the genomes, and the minimum similarity between two genes must be 70% for them to belong to the same orthologous group. The mentioned software provides several files with statistics of genes shared by a large part of the lineage or throughout (soft core and core genes) and some genomes (accessories, subdivided into cloud and shell genes) [27].

Identification of genes associated with the production of metabolites and probiotic activity

The genes involved in the production of lactic acid were obtained from the KEGG database, which links biological functions. Subsequently, the BlastKOALA [28] program was applied, a tool used for annotation and can identify proteins involved in signal transduction, catabolism, transport, biosynthesis, and glycan metabolism, among other metabolic pathways available from the KEGG database [29]. After the metabolic annotation of the pangenome (protein-coding genes in FASTA format, generated by Roary), the identified results were compared with the EC codes (Enzyme Commission Number) described in the KEGG database as associated with the production of lactic acid, acetic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and quorum sensing. This step used an in-house Python script and the libraries BioPython (https://biopython.org/) and BioServices (https://pypi.org/project/bioservices/). The number of genes identified for each biological process in each strain was then scaled based on the greatest number of gene occurrences for each biological process across all strains. Based on this value, an average was calculated to reflect an empirical score.

Probiotic capacity analysis

For the analysis of the potential probiotic capacity of the different strains of L. acidophilus, the tool called iProbiotics was used, which facilitates the rapid screening of probiotics, based on the prediction of probiotic activity in silico, from the genome, which was obtained in FASTA format [30]. iProbiotics has three different parameters: a predictor of probiotic and non-probiotic strains (model one); a predictor of Lactobacillus probiotics, Bifidobacterium probiotics, and other probiotics (model two); and a predictor of probiotic Lactobacillus and non-probiotic Lactobacillus (model three), models three being used in this work, as it is more specific for Lactobacillus spp. This tool uses characteristics to define probiotic capacity, such as the composition of oligonucleotides, since it plays the role of a molecular marker and genes related to probiotic function, such as adsorption gene, competitiveness gene, a gene linked to growth rate, hydrolase gene of bile salts and gene related to retention.

Similarity analysis between genomes

Similarity analysis between genomes was performed using the FastANI tool, which is a method that estimates the Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) through sequence comparison without alignment [31]. In all, 4096 ANI comparisons were produced since the analysis is carried out in an “all against all” (all-vs-all) way. Briefly, the ANI technique allows for estimating a global similarity between two genomes, also serving as an indicator for the taxonomic classification of genera and species [32].

Results

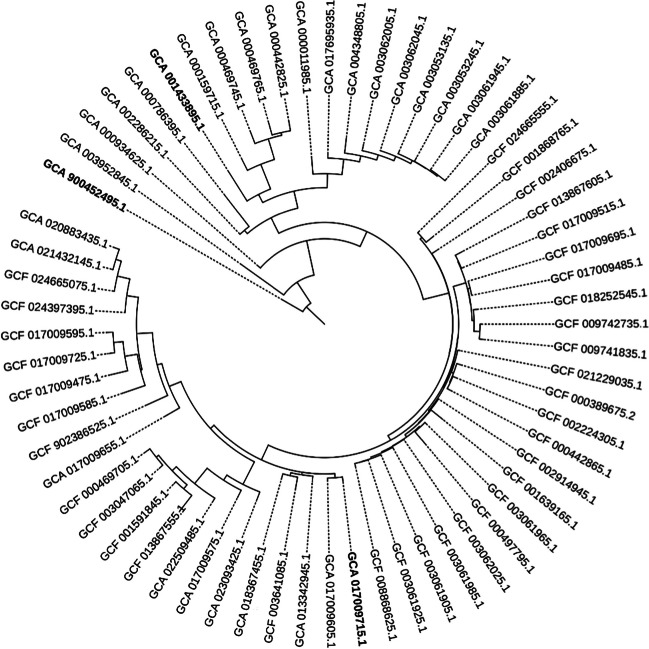

Table 2 shows the numbers of genes identified by the Roary tool from the pangenome, showing the core genome, pangenome, and accessory genome, with 1506 genes, 2643 genes, and 4149 genes, respectively. A representation of the size distribution of the pangenome and core genome is shown in Figure 1. Based on this analysis, it is possible to observe a trend in the growth of the pangenome as more strains are added (considering the average in different permutations), while there is stability in the core genome, which indicates that the pangenome is “open” (the gene repertory of the species is more suitable to grow). Furthermore, it is visible that at some points, there is discontinuity, indicating diversity in the genomes of the strains used.

Table 2.

Number of genes present in the pangenome (total genes), core genome (core genes and soft core genes), and accessory genome (shell genes and cloud genes), as calculated by the Roary tool. The core genome is composed of conserved genes in at least 95% of the analyzed strains

| Gene pool | Abundance | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Core genes | (95% <= strains <= 100%) | 1506 |

| Soft core genes | (94% <= strains < 95%) | 0 |

| Shell genes | (15% <= strains < 94%) | 485 |

| Cloud genes | (0% <= strains < 15%) | 2158 |

| Total genes | (0% <= strains <= 100%) | 4149 |

Fig. 1.

Graph showing the size of the pangenome and conserved genes (core genome) for different iterations from Roary analysis

As presented in Table 3, we noticed a variable distribution of genes involved in producing metabolites such as acetic acid, hydrogen peroxide, lactic acid, and quorum sensing among the strains, in addition to the score generated by the presence of these genes. Among the 64 strains of L. acidophilus tested, NCTC 13721 stood out, as it presented a more significant number of genes involved in the quorum sensing process when compared to the other strains and a considerable number of genes involved in hydrogen peroxide, lactic acid, and acetic acid metabolism, with a score of 91%. Followed by NCTC 13721, DSM 20079 showed a relevant amount of hydrogen peroxide, lactic acid, and acetic acid metabolism genes. However, the number of genes involved in QS was a little lower compared to DSM 20079, which obtained a score of 77%.

Table 3.

Number of genes involved in the metabolic production of different strains of L. acidophilus identified from the analysis with BLASTKOALA

| Strain | Genome | Production metabolic | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acid acetic | Hydrogen peroxide | Acid lactic | Quorum sensing | |||

| NCTC 13721 | GCA_900452495.1 | 21 | 21 | 10 | 38 | 0.91 |

| DSM 20079 | GCF_003047065.1 | 22 | 22 | 9 | 24 | 0.77 |

| APC2845 | GCA_017695935.1 | 21 | 21 | 7 | 26 | 0.71 |

| DSM 20079 | GCA_001433895.1 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 29 | 0.71 |

| ATCC 4796 | GCA_000159715.1 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 28 | 0.70 |

| NCFM | GCA_000011985.1 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 27 | 0.70 |

| DSM 20242 | GCA_000442825.1 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 27 | 0.70 |

| DSM 9126 | GCA_000469745.1 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 27 | 0.70 |

| DS24_1 | GCA_003053135.1 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 26 | 0.70 |

| DS10_1A | GCA_003053245.1 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 26 | 0.70 |

| DS20_1 | GCA_003061885.1 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 26 | 0.70 |

| DS8_1A | GCA_003061945.1 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 26 | 0.70 |

| DS2_1A | GCA_003062005.1 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 26 | 0.70 |

| DS1_1A | GCA_003062045.1 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 26 | 0.70 |

| CIRM-BIA 445 | GCA_000469765.1 | 21 | 21 | 7 | 28 | 0.69 |

| YT1 | GCA_003952845.1 | 20 | 20 | 7 | 25 | 0.69 |

| La-5 | GCA_017009715.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 27 | 0.69 |

| LA1 | GCA_002286215.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 26 | 0.68 |

| LA-G80-111 | GCA_013342945.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 26 | 0.68 |

| BCRC 16092 | GCA_017009575.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 26 | 0.68 |

| BCRC 16099 | GCA_017009605.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 26 | 0.68 |

| BCRC 17481 | GCA_017009655.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 26 | 0.68 |

| L3_101_000G1_dasL3_101_000G1_metabat.metabat.48 | GCA_018367455.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 26 | 0.68 |

| BIO6307 | GCF_008868625.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 26 | 0.68 |

| LA_AVK2 | GCF_009741835.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 26 | 0.68 |

| LA1063 | GCF_017009725.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 26 | 0.68 |

| ATCC 4356 | GCA_000786395.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| FSI4 | GCA_000934625.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| QAULAN51 | GCA_022509485.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| PB2021-BA04 | GCA_023093425.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| La-14 | GCF_000389675.2 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| CIRM-BIA 442 | GCF_000442865.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| CIP 76.13 | GCF_000469705.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| CFH | GCF_000497795.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| WG-LB-IV | GCF_001639165.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| KLDS 1.0901 | GCF_001868765.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| ATCC 53544 | GCF_002224305.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| P2 | GCF_002406675.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| BA05 | GCF_002914945.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| DS9_1A | GCF_003061925.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| DS13_1A | GCF_003061965.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| DS5_1A | GCF_003061985.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| DS11_1A | GCF_003062025.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| UBLA-34 | GCF_003641085.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| s-13 | GCF_013867605.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| BCRC 12255 | GCF_017009485.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| BCRC 14065 | GCF_017009515.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| BCRC 80064 | GCF_017009695.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| LA-G80 | GCF_018252545.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| LA-5 | GCF_024665555.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.68 |

| NBRC 13951 | GCF_001591845.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 24 | 0.68 |

| DS13_1B | GCF_003061905.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 24 | 0.68 |

| LA_AVK1 | GCF_009742735.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 24 | 0.68 |

| s-4 | GCF_013867555.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 24 | 0.68 |

| NBIMCC 8242 (180) | GCF_021229035.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 24 | 0.68 |

| MG-HGUT-02379 | GCF_902386525.1 | 18 | 18 | 7 | 27 | 0.67 |

| 5460 | GCA_021432145.1 | 18 | 18 | 7 | 26 | 0.67 |

| HN017 | GCF_024397395.1 | 18 | 18 | 7 | 26 | 0.67 |

| LA-2 | GCF_024665075.1 | 18 | 18 | 7 | 26 | 0.67 |

| NC55 | GCA_020883435.1 | 18 | 18 | 7 | 25 | 0.67 |

| BCRC 17008 | GCF_017009595.1 | 18 | 18 | 7 | 25 | 0.67 |

| BCRC 17486 | GCF_017009585.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 0.66 |

| BCRC 14079 | GCF_017009475.1 | 18 | 18 | 7 | 25 | 0.64 |

| PNW3 | GCA_004348805.1 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 23 | 0.63 |

Table 4 shows the 64 strains of L. acidophilus and their probability to be a probiotic. Results were presented in descending order and generated through iProbiotics using models one (probiotics probability) and three (probiotic Lactobacillus probability). Strains are sorted based on the model’s three results. As shown, the iProbiotics model could not discriminate the strains, and all of them were predicted as potential probiotics, while model three predicted as probiotics only the strains NCTC 13721 and La-5 with probabilities of 84.8% and 51.9%, respectively.

Table 4.

Different strains of L. acidophilus and their respective ability to be a probiotic according to model one of the iProbiotics web server

| Strain | Genome | iProbiotics models | |

|---|---|---|---|

| One | Three | ||

| NCTC 13721 | GCA_900452495.1 | 84.26% | 84.8% |

| La-5 | GCA_017009715.1 | 99.0% | 51.9% |

| DS20_1 | GCA_003061885.1 | 98.51% | 34.6% |

| L3_101_000G1_dasL3_101_000G1_metabat.metabat.48 | GCA_018367455.1 | 99.25% | 32.7% |

| BA05 | GCF_002914945.1 | 99.56% | 32.6% |

| DS5_1A | GCF_003061985.1 | 99.65% | 31.2% |

| DS10_1A | GCA_003053245.1 | 99.02% | 30.3% |

| KLDS 1.0901 | GCF_001868765.1 | 99.53% | 30.0% |

| CFH | GCF_000497795.1 | 99.07% | 28.6% |

| UBLA-34 | GCF_003641085.1 | 98.83% | 27.4% |

| BCRC 17486 | GCF_017009585.1 | 99.63% | 26.3% |

| LA-G80 | GCF_018252545.1 | 99.24% | 24.9% |

| PB2021-BA04 | GCA_023093425.1 | 99.47% | 24.6% |

| P2 | GCF_002406675.1 | 99.61% | 23.2% |

| LA1063 | GCF_017009725.1 | 99.6% | 22.5% |

| APC2845 | GCA_017695935.1 | 99.75% | 22.1% |

| DS13_1A | GCF_003061965.1 | 97.49% | 21.8% |

| BCRC 17008 | GCF_017009595.1 | 99.44% | 21.6% |

| DS9_1A | GCF_003061925.1 | 99.53% | 21.2% |

| s-13 | GCF_013867605.1 | 99.74% | 21.0% |

| PNW3 | GCA_004348805.1 | 99.64% | 20.3% |

| MG-HGUT-02379 | GCF_902386525.1 | 99.42% | 20.0% |

| LA_AVK1 | GCF_009742735.1 | 99.6% | 19.6% |

| BCRC 12255 | GCF_017009485.1 | 99.82% | 19.6% |

| BCRC 14079 | GCF_017009475.1 | 99.79% | 18.8% |

| DSM 20079 | GCA_001433895.1 | 99.67% | 18.3% |

| DS11_1A | GCF_003062025.1 | 98.89% | 17.9% |

| BCRC 80064 | GCF_017009695.1 | 99.79% | 17.7% |

| QAULAN51 | GCA_022509485.1 | 98.86% | 17.2% |

| s-4 | GCF_013867555.1 | 98.86% | 17.2% |

| WG-LB-IV | GCF_001639165.1 | 99.46% | 17.1% |

| BCRC 16092 | GCA_017009575.1 | 99.73% | 17.0% |

| DS8_1A | GCA_003061945.1 | 99.49% | 16.2% |

| LA_AVK2 | GCF_009741835.1 | 99.01% | 14.3% |

| BCRC 17481 | GCA_017009655.1 | 99.74% | 14.3% |

| DS1_1A | GCA_003062045.1 | 99.57% | 14.0% |

| BCRC 16099 | GCA_017009605.1 | 99.3% | 12.7% |

| BIO6307 | GCF_008868625.1 | 99.54% | 12.1% |

| BCRC 14065 | GCF_017009515.1 | 99.73% | 10.7% |

| NBIMCC 8242 (180) | GCF_021229035.1 | 99.76% | 10.7% |

| DS24_1 | GCA_003053135.1 | 98.94% | 9.4% |

| NBRC 13951 | GCF_001591845.1 | 99.47% | 9.3% |

| DS13_1B | GCF_003061905.1 | 99.67% | 8.7% |

| HN017 | GCF_024397395.1 | 99.45% | 8.6% |

| LA-2 | GCF_024665075.1 | 99.5% | 8.3% |

| 5460 | GCA_021432145.1 | 99.5% | 8.3% |

| YT1 | GCA_003952845.1 | 99.47% | 7.9% |

| NC55 | GCA_020883435.1 | 99.49% | 7.2% |

| DS2_1A | GCA_003062005.1 | 99.57% | 7.1% |

| ATCC 4356 | GCA_000786395.1 | 99.67% | 5.4% |

| DSM 9126 | GCA_000469745.1 | 99.69% | 5.4% |

| CIP 76.13 | GCF_000469705.1 | 99.69% | 5.3% |

| CIRM-BIA 445 | GCA_000469765.1 | 99.73% | 5.0% |

| DSM 20242 | GCA_000442825.1 | 99.59% | 4.7% |

| CIRM-BIA 442 | GCF_000442865.1 | 99.64% | 4.2% |

| ATCC 53544 | GCF_002224305.1 | 99.69% | 4.0% |

| NCFM | GCA_000011985.1 | 99.71% | 3.7% |

| La-14 | GCF_000389675.2 | 99.7% | 3.7% |

| LA1 | GCA_002286215.1 | 99.69% | 3.7% |

| LA-G80-111 | GCA_013342945.1 | 99.7% | 3.7% |

| FSI4 | GCA_000934625.1 | 99.7% | 3.7% |

| LA-5 | GCF_024665555.1 | 99.7% | 3.7% |

| DSM 20079 | GCF_003047065.1 | 99.72% | 3.3% |

| ATCC 4796 | GCA_000159715.1 | 99.8% | 0.16% |

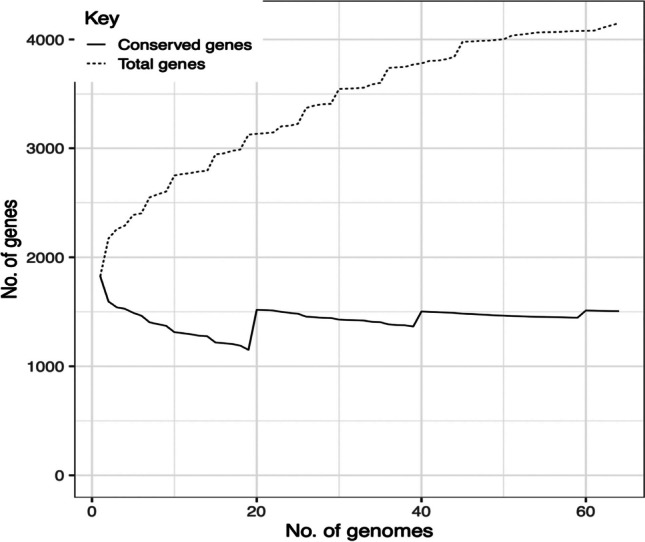

The phylogenetic tree produced by the multiple sequence alignment of the proteins encoded by the core genome is displayed in Figure 2. The NCBI genome assembly accessions of the three strains were identified as more promising for probiotics activity, as predicted by iProbiotics and BlastKOALA, as indicated in bold. Finally, ANI similarity values are present for each pair of strains in Supplementary Data 1. In this analysis, the NCTC 13721 strain did not present genomic similarity with any of the strains tested, considering the minimum threshold of 95% for species. DSM 20079, on the other hand, showed genomic similarity with all strains except NCTC 13721. La-5 obtained about 100% of genomic similarity with eight different strains: L. acidophilus 20_1, L. acidophilus LA-5, L. acidophilus FSI4, L. acidophilus APC2845, L. acidophilus LA-G80-111, L. acidophilus DS1_1A, L. acidophilus LA1, and L. acidophilus BCRC 14065.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree made from the 64 strains of L. acidophilus, with GCA_001433895.1 (DSM 20079), GCA_900452495.1 (NCTC 13721), and GCA_017009715 (La-5). In this analysis, these strains were evolutionarily distant

Software installation and usage

BlastKoala and iProbiotics were accessed from their respective web servers (https://www.kegg.jp/blastkoala/ and http://bioinfor.imu.edu.cn/iprobiotics/public/). Roary, Python, BioPython, BioServices, and FastANI were installed locally using conda (https://docs.conda.io/en/latest/) and Python “pip.”

Discussion

According to the results, of the 64 strains tested in silico, L. acidophilus NCTC 13721, L. acidophilus DSM 20079, and L. acidophilus La-5 showed more significant potential for future in vitro studies. NCTC 13721 presented a higher amount of QS genes compared to the other strains. In addition, NCTC 13721 and DSM 20079 showed similar results in the number of acetic acid, lactic acid, and hydrogen peroxide metabolism genes.

L. acidophilus NCTC 13721, obtained from the vaginal microbiota of a volunteer patient in the United Kingdom and available from the National Collection of Type Cultures bank (NCTC: 13721), showed promising results based on the BlastKOALA and iProbiotics analysis with model one and three; however, this strain is still poorly characterized and have not been evaluated as probiotic to our knowledge. It is relevant to mention that NCTC 13721 presented a total of 90 genes related to processes involved in the probiotic activity (production of acid acetic, hydrogen peroxide, and acid lactic), followed by the DSM 20079 strain with 77 genes. In addition, NCTC 13721 exhibited a significant number of quorum sensing (QS) genes compared to the other strains. These results are important, as lactic acid bacteria with probiotic capacities are related to producing organic acids, bacteriocins, hydrogen peroxide, and biosurfactants [8]. Additionally, they can act by inhibiting bacterial QS and other microorganisms present in the same environment [33]. The QS is fundamental in forming the biofilm, which can increase the time the bacteria will survive in the intestine, increasing its colonization capacity and, thus, making the exchange of nutrients between the host and the microbiota. Furthermore, QS is capable of causing a cooperative change in the expression of bacterial genes, such as the expression of virulence factors [34].

L. acidophilus La-5 strain, correctly predicted as probiotics in our analysis, has already been widely studied in different applications in human health, ranging from in vitro [35–37] to clinical trials [32, 33] studies. Formulations containing this strain are usually prepared in combination with Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lacti and have already been evaluated for a variety of conditions, including diarrhea [38], dermatitis [39], diabetes mellitus [40], and ventilator-associated pneumonia [41].

Regarding the genes involved in producing lactic acid, strains NCTC13721 and DSM 20079 showed higher abundance when compared to other strains. The first showed ten genes, the second 9 genes, and the other 62 strains showed seven genes involved in producing this metabolite. Among the most promising activities of probiotics, the antimicrobial stand out, helping to compete with opportunistic pathogens and inhibiting their adhesion to the mucosa. Lactic acid is an elementary antimicrobial factor [42], responsible for reducing the pH, which leads to inhibition of the growth of pathogenic bacteria [43], since the pH of several pathogenic bacteria is slightly alkaline [8]. The inhibitory and biocidal effects of pure lactic acid in vitro, it is able to act against Gram-negative bacteria: Salmonella enteritidis, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and also against Gram-positive: Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, and Listeria monocytogenes [44]. This inhibitory effect occurs since lactic acid can reduce the pH, preventing the activity of the pathogen’s urease, making this microorganism unable to grow at the adhesion site, thus acting as a bactericidal agent. Furthermore, this acid suppresses pro-inflammatory responses mediated by immune cells causing intestinal and immunological homeostasis through enterocyte renewal and macrophage mobilization [45, 46]. Thus, strains with many genes involved in this metabolic process can be prominent allies against different pathogens.

Based on the analysis using iProbiotics, the NCTC 13721 strain showed close results when tested in model one and model three. It is important to mention that the third is more specific for Lactobacillus spp. with probiotic capacity. In comparison, La-5 showed different results when compared in the two models; in model one, it presented 99%, and in model three, 51.9%, respectively. It is relevant to say that we noticed that iProbiotics was little used until writing this article. This tool uses machine learning, not mapping the mechanisms of action of the probiotic, which are essential to analyze whether or not an organism has the capacity to perform such a function [30]. It is already known that each probiotic will have specific characteristics, and its activities beneficial to the host may not be the same since each strain has its individual particularities [47]. Therefore, in this study, we made a prediction of probiotics based on the criteria used as probiotic mechanisms dictated by the iProbiotics program. We were able to observe that; when we compare model one with model three, the first presents approximately 99% of the strains with probiotic capacity above 90%. Therefore, it is understood that model three is more specific for Lactobacillus spp. with probiotic capacity, informing different percentages for each strain.

According to ANI-based molecular classification standards (Supplementary Data 1), values below 96% similarity and 90% global alignment indicate that the isolates may belong to different species [32]. The NCTC13721 strain showed approximately 81% similarity in genomics compared to the others, including La-5. Therefore, further characterization studies of the NCTC13721 strain are needed to confirm its classification. The genus Lactobacillus spp. has heterogeneous characteristics and includes species with diverse physiological and biochemical features. At present, the definition of L. acidophilus is shown in DNA-DNA hybridization, with its CG content of species ranging from 32% to 50%, exceedingly higher than is reported for well-defined bacterial genera [48, 49]. We highlight that, from the phylogenetic tree, the most promising strains: NCTC 13721, DSM 20079, and La-5, are not similar in their evolutionary characteristics, reinforcing the idea of heterogeneity. L. acidophilus La-5 showed about 100% genomic similarity with eight strains, namely: L. acidophilus DS20_1, L. acidophilus LA-5, L. acidophilus FSI4, L. acidophilus APC2845, L. acidophilus LA-G80-111, L. acidophilus DS1_1A, L. acidophilus LA1, and L. acidophilus BCRC 14065. However, these strains have few reports in the literature, consequently, few in vitro evaluations.

Conclusion

As demonstrated by the in silico analysis, NCTC 13721 strain presents genomic features that are desirable for probiotic bacteria, including a higher number of genes involved in QS metabolism. In addition, NCTC 13721 and DSM 20079 showed more genes involved in the production of metabolites involved in the probiotic activity (lactic acid, acetic acid, and hydrogen peroxide) in relation to the microbial inhibitory effect. However, more studies are needed to better characterize the NCTC 13721 strain since the ANI analysis showed a lower similarity with the other strains from the same species.

Supplementary information

(XLSX 72 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Fábio Pereira Leivas Leite, Daniela Peres Martinez, and Carlos James Scaini for the contribution in the manuscript revision and the Omixlab (Bioinformatics Laboratory of the Federal University of Pelotas) team for all the analysis support. We also thank CAPES and the Post-Graduate Program in Health Sciences of Federal University of Rio Grande for the scholarship granted, which made this work possible.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Responsible Editor: Gisele Monteiro

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.FAO/WHO. World Health Organization. Joint FAO/WHO consultation on evaluation of health and nutritional properties of probiotics in food including powder milk with live lactic acid bacteria. Published online 2001. https://www.fao.org/3/a0512e/a0512e.pdf. Accessed 1 Nov 2022

- 2.Zheng J, Wittouck S, Salvetti E, et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020;70(4):2782–2858. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.004107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein EJC, Tyrrell KL, Citron DM. Lactobacillus species: taxonomic complexity and controversial susceptibilities. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(suppl_2):S98–S107. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salvetti E, Torriani S, Felis GE. The genus Lactobacillus: a taxonomic update. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2012;4(4):217–226. doi: 10.1007/s12602-012-9117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid G, Younes JA, Van der Mei HC, Gloor GB, Knight R, Busscher HJ (2011) Microbiota restoration: natural and supplemented recovery of human microbial communities. Nat Rev Microbiol 9(1). 10.1038/nrmicro2473 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Scillato M, Spitale A, Mongelli G et al (2021) Antimicrobial properties of Lactobacillus cell-free supernatants against multidrug-resistant urogenital pathogens. MicrobiologyOpen 10(2). 10.1002/mbo3.1173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Xiao Y, Zhao J, Zhang H, Zhai Q, Chen W (2021) Mining genome traits that determine the different gut colonization potential of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species. Microb Genomics 7(6). 10.1099/mgen.0.000581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Gao H, Li X, Chen X, et al. The functional roles of Lactobacillus acidophilus in different physiological and pathological processes. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022;32(10):1226–1233. doi: 10.4014/jmb.2205.05041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li W, Zhang Y, Li H, et al. Effect of soybean oligopeptide on the growth and metabolism of Lactobacillus acidophilus JCM 1132. RSC Adv. 2020;10(28):16737–16748. doi: 10.1039/D0RA01632B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naidu AS, Bidlack WR, Clemens RA. Probiotic spectra of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1999;39(1):13–126. doi: 10.1080/10408699991279187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salman MK, Abuqwider J, Mauriello G. Anti-quorum sensing activity of probiotics: the mechanism and role in food and gut health. Microorganisms. 2023;11(3):793. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11030793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao X, Yu Z, Ding T. Quorum-sensing regulation of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Microorganisms. 2020;8(3):425. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8030425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang X, Zhu W, Lv Z, Zou Q. Molecular computing and bioinformatics. Molecules. 2019;24(13):2358. doi: 10.3390/molecules24132358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang Z, Zhou X, Stanton C, et al. Comparative genomics and specific functional characteristics analysis of Lactobacillus acidophilus. Microorganisms. 2021;9(9):1992. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9091992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altermann E, Russell WM, Azcarate-Peril MA, et al. Complete genome sequence of the probiotic lactic acid bacterium Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102(11):3906–3912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409188102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iartchouk O, Kozyavkin S, Karamychev V, Slesarev A (2015) Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus acidophilus FSI4, isolated from yogurt. Genome Announc 3(2). 10.1128/genomeA.00166-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Chung WH, Kang J, Lim MY, et al. Complete genome sequence and genomic characterization of Lactobacillus acidophilus LA1 (11869BP) Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:311400. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stahl B, Barrangou R (2013) Complete genome sequence of probiotic strain Lactobacillus acidophilus La-14. Genome Announc 1(3). 10.1128/genomeA.00376-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Yang X, Wang Y, Huo G (2013) Complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis KLDS4.0325. Genome Announc 1(6). 10.1128/genomeA.00962-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Yu J, Du X, Wang W et al (2011) Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of lactic acid bacteria isolated from sour congee in Inner Mongolia of China. J Gen Appl Microbiol 57(4). 10.2323/jgam.57.197 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Huang CH, Chen CC, Chiu SH, et al. Development of a high-resolution single-nucleotide polymorphism strain-typing assay using whole genome-based analyses for the Lactobacillus acidophilus probiotic strain. Microorganisms. 2020;8(9):1445. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palomino MM, Allievi MC, Martin JF et al (2015) Draft genome sequence of the probiotic strain Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356. Genome Announc 3(1). 10.1128/genomeA.01421-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.(PDF) Infant gut strain persistence is associated with maternal origin, phylogeny, and functional potential including surface adhesion and iron acquisition. ResearchGate. 10.1101/2021.01.26.428340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Gangiredla J, Barnaba TJ, Mammel MK, et al. Fifty-six draft genome sequences of 10 Lactobacillus species from 22 commercial dietary supplements. Genome Announc. Published online June 28, 2018. 10.1128/genomea.00621-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Sun Z, Harris HMB, McCann A, et al. Expanding the biotechnology potential of lactobacilli through comparative genomics of 213 strains and associated genera. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carpi FM, Coman MM, Silvi S, Picciolini M, Verdenelli MC, Napolioni V. Comprehensive pan-genome analysis of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum complete genomes. J Appl Microbiol. 2022;132(1):592–604. doi: 10.1111/jam.15199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sitto F, Battistuzzi FU. Estimating pangenomes with roary. Hall BG, ed. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37(3):933–939. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Morishima K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J Mol Biol. 2016;428(4):726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomez-Fuentes S, Hernández-de la Fuente S, Morales-Ruiz V, et al. A novel, sequencing-free strategy for the functional characterization of Taenia solium proteomic fingerprint. Rinaldi G, ed. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(2):e0009104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun Y, Li H, Zheng L, et al. iProbiotics: a machine learning platform for rapid identification of probiotic properties from whole-genome primary sequences. Brief Bioinform. 2022;23(1):bbab477. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbab477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5114. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciufo S, Kannan S, Sharma S, et al. Using average nucleotide identity to improve taxonomic assignments in prokaryotic genomes at the NCBI. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68(7):2386–2392. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savijoki K, San-Martin-Galindo P, Pitkänen K, et al. Food-grade bacteria combat pathogens by blocking AHL-mediated quorum sensing and biofilm formation. Foods. 2022;12(1):90. doi: 10.3390/foods12010090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng Z, Luo XM, Liu J, Wang H. Quorum sensing, biofilm, and intestinal mucosal barrier: involvement the role of probiotic. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:538077. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.538077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwendicke F, Korte F, Dörfer CE, Kneist S, Fawzy El-Sayed K, Paris S. Inhibition of Streptococcus mutans growth and biofilm formation by probiotics in vitro. Caries Res. 2017;51(2):87–95. doi: 10.1159/000452960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Najarian A, Sharif S, Griffiths MW. Evaluation of protective effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus La-5 on toxicity and colonization of Clostridium difficile in human epithelial cells in vitro. Anaerobe. 2019;55:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zambori C, Morvay AA, Sala C, et al. Antimicrobial effect of probiotics on bacterial species from dental plaque. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2016;10(3):214–221. doi: 10.3855/jidc.6800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fox MJ, Ahuja KDK, Robertson IK, Ball MJ, Eri RD. Can probiotic yogurt prevent diarrhoea in children on antibiotics? A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006474. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Litus O, Derkach N, Litus V, Bisyuk Y, Lytvynenko B. Efficacy of probiotic therapy on atopic dermatitis in adults depends on the C-159T polymorphism of the CD14 receptor gene - a pilot study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(7):1053–1058. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tonucci LB, Olbrich Dos Santos KM, Licursi de Oliveira L, Rocha Ribeiro SM, Duarte Martino HS. Clinical application of probiotics in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2017;36(1):85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsilika M, Thoma G, Aidoni Z, et al. A four-probiotic preparation for ventilator-associated pneumonia in multi-trauma patients: results of a randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2022;59(1):106471. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2021.106471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tachedjian G, Aldunate M, Bradshaw CS, Cone RA. The role of lactic acid production by probiotic Lactobacillus species in vaginal health. Res Microbiol. 2017;168(9-10):782–792. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hernández-Aquino S, Miranda-Romero LA, Fujikawa H, Maldonado-Simán EDJ, Alarcón-Zuñiga B. Antibacterial activity of lactic acid bacteria to improve shelf life of raw meat. Biocontrol Sci. 2019;24(4):185–192. doi: 10.4265/bio.24.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stanojević-Nikolić S, Dimić G, Mojović L, Pejin J, Djukić-Vuković A, Kocić-Tanackov S. Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid against pathogen and spoilage microorganisms: antimicrobial activity of lactic acid. J Food Process Preserv. 2016;40(5):990–998. doi: 10.1111/jfpp.12679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe T, Nishio H, Tanigawa T, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota prevents indomethacin-induced small intestinal injury: involvement of lactic acid. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297(3):G506–G513. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90553.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Markowiak-Kopeć P, Śliżewska K. The effect of probiotics on the production of short-chain fatty acids by human intestinal microbiome. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1107. doi: 10.3390/nu12041107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajab S, Tabandeh F, Shahraky MK, Alahyaribeik S. The effect of lactobacillus cell size on its probiotic characteristics. Anaerobe. 2020;62:102103. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2019.102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bull M, Plummer S, Marchesi J, Mahenthiralingam E. The life history of Lactobacillus acidophilus as a probiotic: a tale of revisionary taxonomy, misidentification and commercial success. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2013;349(2):77–87. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amann RI, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59(1):143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX 72 kb)