Abstract

Protoanemonin is a toxic metabolite which may be formed during the degradation of some chloroaromatic compounds, such as polychlorinated biphenyls, by natural microbial consortia. We show here that protoanemonin can be transformed by dienelactone hydrolase of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 to cis-acetylacrylate. Although similar Km values were observed for cis-dienelactone and protoanemonin, the turnover rate of protoanemonin was only 1% that of cis-dienelactone. This indicates that at least this percentage of the enzyme is in the active state, even in the absence of activation. The trans-dienelactone hydrolase of Pseudomonas sp. strain RW10 did not detectably transform protoanemonin. Obviously, Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 possesses at least two mechanisms to avoid protoanemonin toxicity, namely a highly active chloromuconate cycloisomerase, which routes most of the 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate to the cis-dienelactone, thereby largely preventing protoanemonin formation, and dienelactone hydrolase, which detoxifies any small amount of protoanemonin that might nevertheless be formed.

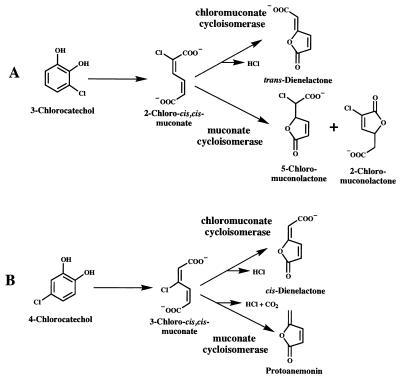

A major route for mineralization of chloroaromatics is their transformation into chlorocatechols (14) and further metabolism to Krebs cycle intermediates by enzymes of the chlorocatechol pathway (8, 9, 19). In contrast to earlier assumptions that enzymes of this route catalyze reactions analogous to those of the widespread 3-oxoadipate pathway, it has recently been shown that muconate cycloisomerase and chloromuconate cycloisomerase, which act on cis,cis-muconates formed by intradiol cleavage of catechols, catalyze different reactions with chloromuconates as substrates (Fig. 1). In the case of 2-chloro-cis,cis-muconate, chloromuconate cycloisomerase catalyzes a dehalogenation to form trans-dienelactone (19), whereas muconate cycloisomerase produces a mixture of 2-chloro- and 5-chloromuconolactone (22). In the case of 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate, chloromuconate cycloisomerase carries out a dehalogenation reaction to form the cis-dienelactone, whereas muconate cycloisomerase simultaneously dehalogenates and decarboxylates to form protoanemonin (3), a toxic metabolite (7, 20).

FIG. 1.

Bacterial metabolism of 2-chloro-cis,cis-muconate (A) and 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate (B) according to Blasco et al. (3) and Vollmer et al. (22).

The formation of protoanemonin has recently been shown to be a major reason for the poor performance of bacterial polychlorinated biphenyl degraders in environmental settings (2). These experiments also indicated that the natural microflora in such settings has the potential to further transform protoanemonin, although the metabolic route involved has not until now been investigated.

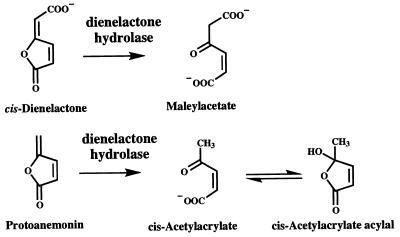

Protoanemonin can be regarded as a structural analog of cis- and trans-dienelactone, which are intermediates in the degradation of chlorocatechols by enzymes of the chlorocatechol pathway. Dienelactones are transformed by dienelactone hydrolase of this pathway into maleylacetate (19). On the basis of crystallographic studies of the dienelactone hydrolase of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 (5, 12), it has been argued that a carboxyl substituent is an essential structural element of the substrate for the fully active enzyme (1).

It was perhaps unexpected, therefore, that in preliminary experiments we found that cell extracts of 3-chlorobenzoate-grown cells of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 were able to transform protoanemonin with a specific activity of 2 to 4 U/g of protein, which corresponds to about 1% of the activity obtained with cis-dienelactone as a substrate. Unless stated otherwise, enzyme activities were assayed spectrophotometrically at 260 nm for protoanemonin as a substrate, with a reaction coefficient of 13.1 mM−1 cm−1 (calculated from the difference in absorption of protoanemonin with ɛ260 = 15.1 mM−1 cm−1 and the reaction product cis-acetylacrylate with ɛ260 = 2.0 mM−1 cm−1), or at 280 nm for cis-dienelactone (ɛ260 = 17.0 mM−1 cm−1) as a substrate in 10 mM histidine-HCl (pH 6.5) (18) with 50 μM substrate. Protein concentrations were measured by the procedure of Bradford (4). To ascertain whether or not dienelactone hydrolase is responsible for this activity, the enzyme was purified to homogeneity from 3-chlorobenzoate-grown cells by a modification of a previously described procedure (11). Cell extracts were prepared after resuspension in 20 mM ethylenediamine buffer (pH 7.3) containing 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The extract (volume, 5 ml; protein, 146 mg) was initially applied to a Mono Q HR 10/10 column. Proteins were eluted with 10 mM ethylenediamine buffer (pH 7.3)–0.1 mM DTT and a 200-ml 0 to 0.2 M linear gradient of NaCl (flow rate, 2 ml/min; fraction volume, 4 ml). The fractions with the highest activity (12 ml; eluting at ca. 0.1 M NaCl) were pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration to a final volume of 2.5 ml. Ammonium sulfate was added to 45% saturation. The supernatant was clarified by centrifugation and applied to a Phenyl Superose HR 5/5 column. Proteins were eluted with 50 mM Tris-HCl (50 mM)–2 mM MnSO4–0.1 mM DTT and a 12-ml linear gradient from 2 to 0.8 M (NH4)2SO4 followed by a 30-ml linear gradient of 0.8 to 0 M (NH4)2SO4 (flow rate, 0.5 ml/min; fraction volume, 0.5 ml). Fractions with the highest activity (eluting at ca. 0.6 M) were pooled, concentrated by ultrafiltration to a final volume of 0.27 ml, and applied to a Superose 6 HR 10/30 column. Elution of proteins was performed with 50 ml of Tris-HCl (50 mM [pH 7.5]) containing 100 mM NaCl at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The purification yielded a product which showed a single band at 28 to 29 kDa on sodium dodecyl sulfate gels. There were no impurities observed on sodium dodecyl sulfate gels, which indicates that the preparation was highly homogeneous (>95%).

As shown in Table 1, activities for cis-dienelactone and protoanemonin copurified, indicating that dienelactone hydrolase is responsible for protoanemonin transformation in B13. By analogy with the hydrolysis of dienelactone, cis-acetylacrylate could be expected as the reaction product (Fig. 2). This compound was synthesized as a standard from trans-acetylacrylate according to the method of Schlömann et al. (16). The transformation of protoanemonin by purified dienelactone hydrolase was followed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) by a previously described procedure (13). The reaction mixture contained (in a total volume of 300 μl) Bis-Tris (10 mM [pH 6.5]), 220 μM protoanemonin, and 20 μl of purified dienelactone hydrolase (corresponding to 0.077 U, when the activity was measured with cis-dienelactone as a substrate). With an aqueous solvent system of 4.5% methanol and 0.1% H3PO4, the retention volume of protoanemonin was 10.6 ml, that of cis-acetylacrylate was 3.4 ml, and that of trans-acetylacrylate was 7.0 ml. Formation of a single product which coeluted with and showed an absorption spectrum (λmax = 205 nm) identical to that of authentic cis-acetylacrylate was observed. Assuming the identity of the reaction product with cis-acetylacrylate, transformation of protoanemonin to this product by dienelactone hydrolase was essentially quantitative (88% ± 5%).

TABLE 1.

Purification of dienelactone hydrolase of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13

| Purification step | Vol (ml) | Amt of protein (mg) | Total activity (U)a | Sp. act. (U/g)a | Recov- ery (%) | Purifi- cation (fold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract | 5 | 146 | 37.9 (0.35) | 260 (2.4) | 100 | 1 |

| Mono Q eluate | 2.5 | 1.25 | 25.0 (0.25) | 20,000 (200) | 66 | 77 |

| Phenyl-Sepharose eluate | 0.27 | 0.28 | 7.3 (0.067) | 26,500 (240) | 19 | 102 |

| Superose 6 eluate | 1.5 | 0.10 | 5.8 (0.058) | 58,800 (580) | 15 | 226 |

Values are given for cis-dienelactone as the substrate. Values in parentheses are the corresponding values for protoanemonin as the substrate.

FIG. 2.

cis-Dienelactone and protoanemonin conversion by the dienelactone hydrolase of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. cis-Acetylacrylate under acidic conditions is present in a cyclic form (21).

Because the same product was formed by cell extracts of 3-chlorobenzoate-grown cells and not further metabolized, a preparative transformation was performed. Freshly prepared protoanemonin (80 μmol in 500 ml of Bis-Tris [pH 6.5]; 30 mM) (3) was incubated with a cell extract corresponding to 160 mg of protein, and transformation was monitored by HPLC. After complete conversion of the substrate, the reaction mixture was acidified to pH 2 and extracted with ethyl acetate (three times at 200 ml each). The dried residue was redissolved in 2 ml of 5% methanol (in H2O) and in portions of 200 μl purified by preparative HPLC with an aqueous solvent system containing 5% methanol and 0.1% H3PO4 at a flow rate of 6 ml/min on a GG350 column (16 by 250 mm) filled with Lichrosorb RP8 (10 μm). Fractions containing the reaction product were extracted with ethyl acetate as described above. The dried product was further analyzed by 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance. The recorded spectrum (in d6-acetone) was identical to that reported for cis-acetylacrylate acylal, the tautomeric form of cis-acetylacrylate (21). Besides protons of a methyl substituent with a chemical shift of δ = 1.63 ppm, two single protons (6.07 and 7.44 ppm) showing a vicinal coupling of 5.6 Hz were identified.

Typical Michaelis-Menten kinetics were observed with both cis-dienelactone and protoanemonin. Transformation was recorded at 285 nm for protoanemonin as the substrate (ɛ285 = 3.8 mM−1 cm−1) or at 310 nm for cis-dienelactone as substrate (ɛ310 = 4.3 mM−1 cm−1). Whereas the Km values for protoanemonin (415 ± 46 μM) and cis-dienelactone (381 ± 28 μM) were similar, the Vmax for protoanemonin transformation was only 0.8% of that for cis-dienelactone. The kcat values for protoanemonin and cis-dienelactone were calculated to be 125 ± 8 min−1 and 15,600 ± 660 min−1, respectively (assuming a molecular weight of 25,489 as calculated from the nucleotide sequence [10]). Inhibition experiments involving the addition of up to 300 μM protoanemonin to a reaction mixture containing 25 to 200 μM cis-dienelactone demonstrated that protoanemonin acts as a competitive inhibitor of the transformation of cis-dienelactone. Ki was calculated to be 430 μM.

Dienelactone hydrolases have been classified into three distinct groups based on their substrate specificity (15, 18). The dienelactone hydrolase of B13 and the pJP4-encoded enzyme for chlorocatechol metabolism showed turnover of both cis- and trans-dienelactone (18). The dienelactone hydrolase of Burkholderia cepacia, however, hydrolyzes only the cis isomer with significant activity and differs in basic properties from the enzymes described above (17). A third class of enzymes convert trans-dienelactone, but not the cis isomer (15). Both cis-dienelactone hydrolase from B. cepacia and trans-dienelactone hydrolase from Pseudomonas putida RW10 (3) were partially purified by anion-exchange chromatography and analyzed for their activity on protoanemonin. Cell extracts (1 ml, ca. 20 mg each) were applied to a Mono Q HR 5/5 column, and proteins were eluted with a 20-ml linear gradient from 0 to 0.4 M NaCl in Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) plus 2 mM MnCl2 (flow rate, 1 ml/min; fraction volume, 0.5 ml). Fractions exhibiting the highest activities were analyzed. The activity of cis-dienelactone hydrolase from B. cepacia with 50 μM protoanemonin was 0.08% of that observed with 50 μM cis-dienelactone. No activity of trans-dienelactone hydrolase with protoanemonin was detected (detection limit about 0.1% of the activity observed with 50 μM trans-dienelactone). The Km value of this enzyme for trans-dienelactone was calculated to be 1.8 mM.

The dienelactone hydrolase of B13 has been intensively studied. The hydrolysis of dienelactones involves a catalytic triad comprised of Cys123, His202, and Asp171. The crystal structure suggests that native enzyme exists predominantly in a catalytically inert configuration in which the cysteine is neutral and points away from the active site binding cleft (1, 6). It has been suggested that substrate binding induces two conformational changes at the active site. On one hand, the anionic side chain interacts with Arg206, which leads to a conformational shift in Glu36. On the other hand, the carbonyl oxygen forms a hydrogen bond with Leu124, thus allowing the thiol group of Cys123 to rotate. Whereas protoanemonin can be assumed to form the necessary hydrogen bond with Leu124, it should not induce the necessary conformational changes allowing the Glu36 to abstract the thiol proton. Comparison of the Km and Vmax values seems to confirm this. trans-Dienelactone is bound most efficiently (Km = 15 μM [11, 19]), while cis-dienelactone and protoanemonin bind less efficiently, most probably due to lack of or inefficient interaction with Arg206 and Arg81. cis-Dienelactone, however, still seems to trigger the activation mechanism, as evidenced by a Vmax similar to that of trans-dienelactone (11, 19), whereas protoanemonin is converted by the naturally existing population of active state enzyme at a much slower rate.

It has been reported that both the 3-oxoadipate pathway and the chlorocatechol pathway are induced in B13 cells growing on 3-chlorobenzoate (3). Consequently, the muconate and chloromuconate cycloisomerases compete for the intermediate 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate under these conditions. Blasco et al. (3) reported the accumulation of only cis-dienelactone, when a mixture of muconate and chloromuconate cycloisomerases was used for transformation of 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate, presumably due to the high activity of chloromuconate cycloisomerase for this substrate. However, it is likely that some protoanemonin can be formed from 3-chloro-cis,cis-muconate under certain inducing conditions and by other microorganisms according to the relative affinities of the isoenzymes for the substrate. It seems likely, therefore, that dienelactone hydrolase has the additional function of detoxification of minor amounts of protoanemonin that may be formed during chloroaromatic degradation.

Acknowledgments

K.N.T. expresses his gratitude to the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie for generous support. We thank H.-J. Hecht for many helpful and productive discussions and for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beveridge A J, Ollis D L. A theoretical study of substrate induced activation of dienelactone hydrolase. Protein Eng. 1995;8:135–142. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blasco R, Mallavarapu M, Wittich R-M, Timmis K N, Pieper D H. Evidence that formation of protoanemonin from metabolites of 4-chlorobiphenyl degradation negatively affects the survival of 4-chlorobiphenyl-cometabolizing microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:427–434. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.427-434.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasco R, Wittich R-M, Mallavarapu M, Timmis K N, Pieper D H. From xenobiotic to antibiotic. Formation of protoanemonin from 4-chlorocatechol by enzymes of the 3-oxoadipate pathway. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29229–29235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheah E, Ashley G W, Gary J, Ollis D. Catalysis by dienelactone hydrolase: a variation on the protease mechanism. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1993;16:64–78. doi: 10.1002/prot.340160108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheah E, Austin C, Ashley G W, Ollis D. Substrate-induced activation of dienelactone hydrolase: an enzyme with a naturally occurring Cys-His-Asp triad. Protein Eng. 1993;6:575–583. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.6.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Didry N, Dubreuil L, Pinkas M. Activité antibacterienne des vapeurs de protoanémonine. Pharmazie. 1991;46:546–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorn E, Knackmuss H-J. Chemical structure and biodegradability of halogenated aromatic compounds. Substituent effects on 1,2-dioxygenation of catechol. Biochem J. 1978;174:85–94. doi: 10.1042/bj1740085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorn E, Knackmuss H-J. Chemical structure and biodegradability of halogenated aromatic compounds. Two catechol 1,2-dioxygenases from a 3-chlorobenzoate-grown pseudomonad. Biochem J. 1978;174:73–84. doi: 10.1042/bj1740073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frantz B, Ngai K-L, Chatterjee D K, Ornston L N, Chakrabarty A M. Nucleotide sequence and expression of clcD, a plasmid-borne dienelactone hydrolase gene from Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:704–709. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.704-709.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ngai K-L, Schlömann M, Knackmuss H-J, Ornston L N. Dienelactone hydrolase from Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:699–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.699-703.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pathak D, Ollis D. Refined structure of dienelactone hydrolase at 1.8 A. J Mol Biol. 1990;214:497–525. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90196-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prucha M, Wray V, Pieper D H. Metabolism of 5-chlorosubstituted muconolactones. Eur J Biochem. 1996;237:355–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reineke W, Knackmuss H-J. Microbial degradation of haloaromatics. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1988;42:263–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlömann M. Evolution of chlorocatechol catabolic pathways. Conclusions to be drawn from comparisons of lactone hydrolases. Biodegradation. 1994;5:301–321. doi: 10.1007/BF00696467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlömann M, Fischer P, Schmidt E, Knackmuss H-J. Enzymatic formation, stability, and spontaneous reactions of 4-fluoromuconolactone, a metabolite of the bacterial degradation of 4-fluorobenzoate. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5119–5129. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5119-5129.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlömann M, Ngai K-L, Ornston L N, Knackmuss H-J. Dienelactone hydrolase from Pseudomonas cepacia. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2994–3001. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2994-3001.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlömann M, Schmidt E, Knackmuss H-J. Different types of dienelactone hydrolase in 4-fluorobenzoate-utilizing bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5112–5118. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5112-5118.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt E, Knackmuss H-J. Chemical structure and biodegradability of halogenated aromatic compounds. Conversion of chlorinated muconic acids into maleoylacetic acid. Biochem J. 1980;192:339–347. doi: 10.1042/bj1920339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seegal B C, Holden M. The antibiotic activity of extracts of Ranunculaceae. Science. 1945;101:413–414. doi: 10.1126/science.101.2625.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seltzer S, Stevens K D. The preparation of cis-β-acetylacrylic acid. J Org Chem. 1967;33:2708–2711. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vollmer M K, Fischer P, Knackmuss H-J, Schlömann M. Inability of muconate cycloisomerases to cause dehalogenation during conversion of 2-chloro-cis,cis-muconate. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4366–4375. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.14.4366-4375.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]