Abstract

Urban channels in amazon cities are very polluted, with garbage and sewage disposal in these aquatic environments, favoring the high dissemination of waterborne viruses such as human adenovirus (HAdV). The aim of this study was to perform the detection and molecular characterization of adenovirus in urban channels and in a wastewater treatment plant located in a metropolitan city in the Amazon. Additionally, metagenomic analyses were performed to assess viral diversity. Samples were concentrated by organic flocculation, analyzed by quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) and sequenced (Sanger e next generation sequencing). Cell culture was performed to verify the viability of HAdV particles. A total of 104 samples were collected, being the HAdV positivity of 76% (79/104). Among the positive samples, 29.1% (23/79) were characterized as HAdV-F40 (87%, 20/23), HAdV-F41 (8.7%, 2/23), and HAdV-B (4.3%, 1/23). Average precipitation rates ranged from 163 to 614 mm, while the pH ranged from 6.9 to 7.6. Eight positive samples were inoculated into A549 cells and in 4 of these, was observed changes in the structure of the cell monolayer, alteration in the structure of the cell monolayer was observed, but without amplification when analyzed by PCR. The metagenomic data demonstrated the presence of 14 viral families, being the most abundant: Myoviridae (41% of available reads), Siphoviridae (24.5%), Podoviridae (14.1%), and Autographiviridae (6.9%) with more than 85% of the total number of identified reads. This study reinforcing that continuous surveillance may contribute to monitoring viral diversity in aquatic environments and provide early warning of potential outbreaks.

Keywords: Virus, Wastewater, Metagenomic, Amazonian

Introduction

The large Amazonian cities are cut by rivers that have been converted, over the years, into urban drainage channels (UDC) with the aim of accumulating and draining rainwater, in order to avoid flooding, in addition to being a destination for rainwater sewage and sanitary. Communities of viruses, bacteria, and parasites are dispersed from the release of sewage and garbage on a large scale, causing serious socio-environmental problems, harming the population health and affecting the Amazonian aquatic ecosystems [1].

Enteric viruses are the most common pathogens in the wastewater due to their environmental stability, low infectious dose (few particles infect an individual), high viral shedding rate in the environment, and the ability to develop severe infectious diseases, especially in children [2, 3]. HAdV are non-enveloped viruses, with a capsid of icosahedral symmetry, measuring approximately 90 nanometers (nm) in diameter and their genome is composed of double-stranded, linear, and non-segmented DNA; these characteristics provide great resistance environmental. These viruses are part of the Adenoviridae family, and the genus Mastadenovirus is formed by 104 serotypes that are divided into seven species classified from A to G. Species B, C, and E, for example, are responsible for affecting children and causing respiratory or ocular syndromes. Species D can cause keratoconjunctive epidemics and species A, G, and F are more associated with enteric infections [4, 5].

Gastroenteric infections are mainly caused by F species, types 40 and 41, which are responsible for 57 to 66% of these cases [6–9]. In addition to gastroenteric manifestations, HAdV is also related to ocular infections (acute follicular conjunctivitis, pharyngoconjunctival fever, and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis) and respiratory tract infections (infection of non-ciliated respiratory epithelium cells, such as tonsils and adenoids) [10].

Recently in the UK, HAdV-F (mainly type 41) was detected in 65.9% of the feces of children with acute hepatitis [11–13]. Previously, HAdV-41 was not associated with hepatitis and was generally considered to cause gastroenteritis in children and immunocompromised patients [11]. There is a possibility that a change in the tropism of HAdV-41 could be responsible for its link with acute hepatitis, but further investigations are needed to define the true cause of these cases [14]. Although HAdV-41 could be detected in part of the infants showing acute hepatitis of unknown etiology in many localities, it has shown that the overt of clinical signs might be more related to Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), single-stranded DNA parvoviruses, as demonstrated recently by Servellita et al. [15]. Epidemiological investigation in wastewater can predict possible increases in the circulation of this virus in humans [16].

Next generation sequencing (NGS) approaches have been widely used to characterize the wastewater unknown viromes and support the reconstruction of viral complete genomes. DNA sequencing, using the Sanger technique, can be valuable as confirmation of insertion and cloning and confirmation of equivocal NGS results. However, the most recently NGS technologies have performance capabilities and lower costs per sample [17]. Used together, both can provide results that complement each other in virome analysis in wastewater.

In this scope, the present study aimed to detect human adenoviruses using molecular methods and cell culture for isolation, in addition to characterizing the virome composition in wastewater samples from UDC in the city of Belém, Pará, Brazil.

Material and methods

Sampling points and collections

The study was carried out in the city of Belém, in the Amazon region, Northern Brazil. Wastewater samples were collected monthly from January to December 2021 from a wastewater treatment plant (WTP) (WTP—1° 25′ 41.9″ S, 48° 29′ 31.9″ W); and from eight points of drainage channels (PT): PT01 (1°26′ 11.8″ S, 48° 28′ 39.4″ W); PT02 (1° 27′ 38.5″ S, 48° 28′ 58.2″ W); PT03 (1° 26′ 31.6″ S, 48° 29′ 30.7″ W); PT04 (1° 27′31.6″ S, 48° 29′ 56.6″ W); PT05 (1° 27′ 24.8″ S, 48° 27′ 34.6″ W); PT06 (1° 27′ 46.1″ S, 48° 28′ 25.0″ W); PT07 (1° 28′ 20.9″ S, 48° 29′ 51.8″ W); PT08 (1° 28′ 20.4″ S, 48° 27′ 17.8″ W) (Fig. 1). The choice of points was made based on the watersheds located in the central and peninsular region of the city that suffer the most environmental impacts, in addition, easily accessible channels and without riparian forest in the surroundings were also included as an option. Sampling was defined as non-probabilistic for convenience.

Fig. 1.

Geographic distribution of the collection points of this study: the eight urban channels and the treatment plant in the city of Belém, Northern Brazil. Source: Google Earth

The collections were carried out monthly by technicians and researchers in two moments (due to logistical reasons), in the interval of 2 weeks. In the first moment, samples were obtained from points PT01 to PT04 and in the second moment from points PT05 to PT08, totalizing 96 samples from the UDC and eight from the WTP. The specimens were always collected as close as possible to the sewage outlet in the channel and the WTP. Immediately after obtaining them, they were placed in 1-l flasks, with screw caps, whose containers were hermetically closed and refrigerated in an isothermal box with ice (± 4 °C), in order to be transported to the Laboratory of Gastroenteric Viruses (LVG), of the Virology Section (SAVIR), where they were processed for viral investigation.

At the collection time were made the following measurements were taken: pH and wastewater temperature (°C) using a portable pH measuring device (pHEP®4, Hanna); and water volume level in the channel (dry, medium, and full). The daily rainfall was obtained from the National Institute of Meteorology database (https://portal.inmet.gov.br/).

Viral concentration and total nucleic acid extraction

Viral concentration was performed using the organic flocculation method with skimmed and acidified milk, as described by Calgua [18], this method dispenses with the use of membranes and ultracentrifuges, reducing costs and being easy and quick to perform. Subsequently, total nucleic acid was obtained using a commercial kit (5x MagMaxTMPathogen RNA/DNA kit, Applied Biosystems, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell culture and viral isolation

For viral viability assays, HAdV positive wastewater samples were propagated on the continuous A549 cell line (human adenocarcinoma alveolar basal epithelial cells—ATCC, CCL-185). The criteria used in selecting the inoculated samples were having the best cycle threshold (CT) (< 35), having a sufficient amount of material, and having been sequenced by traditional genomic sequencing.

A volume of 200 μL of concentrated wastewater samples treated with PSA antibiotics (penicillin 100 U/mL streptomycin sulfate, 100 mg/mL/amphotericin B 0.25 mg/mL) were inoculated using Dulbecco’s minimal essential (DMEM) growth medium in 25 cm2 bottles, targeting HAdV particles isolation.

To prepare the plates, the A549 cells were treated with trypsin and distributed in the cell culture plate, that was kept in an oven at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After the growth of the monolayer to satisfactory confluence, (about 80%) the growth medium was discarded; then, 200 μL of the concentrated wastewater samples were inoculated in the monolayer in duplicate and incubated for viral adsorption, for 1 h in an oven at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 (with the application of gentle circular movements, every 15 min).

After 1 h of adsorption, the inoculum was removed and maintenance medium corresponding to 1.5 mL of DMEM at 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added to refeed the cells taken to an oven at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. The plates were observed daily for detailed evaluation of the cellular monolayer, in an inverted light microscope and verification of the formation of cytopathic effect (CPE).

All bottles, with or without CPE, were frozen at −70 °C, on the seventh post-inoculation day. In order to evaluate the behavior of the possible isolated samples of HAdV in culture, they were submitted to four passages, whose inoculum, consisted of the suspension obtained by two cycles of freezing and thawing of the culture plates, carried out with an interval of 8 days.

Viability of viral particles recovered by ICC-PCR assay (cell culture integrated PCR)

Cultured samples suggestive of HAdV infection were retested by qPCR with the expectation of obtaining lower CT values when compared to those obtained before cell culture assays.

After the fourth passage, all cells were subjected to qPCR, using 2 μl from each tube, which were heated once at 95 °C, followed by freezing on dry ice. Those that showed a decrease in Ct for HAdV would be considered positive in cell culture.

HAdV detection, Sanger nucleotide sequencing, and phylogenetic analysis

For initial screening, HAdV detection targeting partial hexon gene amplification was performed by qPCR using the GoTaq Probe qPCR Master Mix, 2x (PROMEGA, USA) and the primers and probes described by Hernroth [19] with some modifications [20] with an amplification of a 69 pb fragment. The reactions were made in the QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosytems, USA) under the following conditions: 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min.

HAdV qPCR positive samples were retested by one-step PCR targeting hexon gene using the AD1 and AD2 primer [21]. Reactions were carried out using 2.5 μL H2O-free DNAse/RNAse, 12.5 μL of 2X Reaction Mix, 0.5 μL of each primer (20 pmol), and 1 μL SuperScript® III Platinum™ Taq Mix. Amplicons of the size of 482 base pair (bp) were purified (Qiaquick PCR purification kit, Qiagen, Germany) and sequenced using the Big Dye Terminator® v.3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosytems®) on the 3130xl Genetic Analyzer Automatic Sequencer (Applied Biosystems®).

Genome sequences from other parts of the world were downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and aligned with the genomes from present study using the Mafft v.7.471 [22]. For the phylogenetics analysis, the IQ-TREE software version 2 [23] with 1000 bootstraps was used as statistical support and the phylogenetic trees were generated by the maximum likelihood method and was used to define the best substitution model and after the comparison, the GTR was defined as the best nucleotide substitution model.

NGS libraries for metagenomic analysis

NGS genomic libraries were constructed from 50 ng of DNA using the Ion Xpress Plus Fragment Library kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) and quantified by qPCR using the Ion Library TaqMan Quantitation kit (Applied Biosystems, USA). Libraries were pooled at equimolar concentration (100 pM) and the pool was diluted for a final concentration of 30 pM. The Ion 530 chip was loaded using automated template preparation Ion Chef System (Thermo Fisher, USA) and sequenced in the Ion GeneStudio S5 semiconductor sequencer (Thermo Fisher, USA).

Bioinformatic analysis

The reads were trimmed using the fastp tool [23] and assembled with the Megahit V.1.2.9 software using the NR database (NCBI Non-Redundant Protein Database [https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov]). Taxonomic classification was performed in the Kraken 2 program [24] interactive analysis performed in Pavian R and Krona [25]. For editing the viral contigs, the Geneious v.9.1.8 program was used [26]. All the softwares were performed with default parameters unless specified.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using BioEstat 5.0 software [27]. The simple linear regression test was used to establish comparisons of precipitation and Ph with HAdV positivity. G-test was used to correlate channel water level with HAdV positivity and compare adenovirus positivity in WTP × UDB; a p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance with 95% confidence interval.

Results

A total of 104 wastewater samples were collected from eight UDC (N = 96) and one WTP (N = 8) and analyzed by qPCR, obtaining a positivity of 76% (79/104), with 75% (72/96) from UDC and 87.5% (7/8) from WTP.

HAdV was detected in all eight UDC, with 100% (12/12) positivity in PT1 and PT2 at sampling points PT1 and PT2. Regarding the monthly distribution, HAdV was detected in all months of the year with greater positivity in February, March, May, and November. Precipitation ranged from 163 (October) to 614 mm (February) unrelated to HAdV positivity (F = 0.2127; P = 0.6577). The average pH value varied from 6.9 at PT1 sampling point to 7.6 at PT5/PT7 and also did not influence the positivity obtained for HAdV (F = 1.7470; P = 0.2140) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Detection, pH, and precipitation of adenovirus in 104 wastewater samples from eight urban drainage channels and one wastewater treatment plant during January to December 2021

| Sampling points | Type of sample | AdV detection | pH | Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (N/total) | Mean value (min–max) | Monthly average value (min–max) | ||

| PT01 | Wastewater from urban drainage channels | 100 (12/12) | 6.9 (6.2–8.6) | 331.79 (163.40–614.10) |

| PT02 | 100 (12/12) | 7.1 (6.5–9.2) | ||

| PT03 | 58.3 (7/12) | 7.0 (5.7–8.3) | ||

| PT04 | 75.0 (9/12) | 7.4 (6.7–9.0) | ||

| PT05 | 75.0 (9/12) | 7.6 (6.7–9.6) | ||

| PT06 | 58.3 (7/12) | 7.4 (6.1–9.8) | ||

| PT07 | 75.0 (9/12) | 7.6 (6.5–9.9) | ||

| PT08 | 58.3 (7/12) | 7.3 (6.6–9.6) | ||

| WTP | Treated wastewater | 87.5 (7/8) | NI | |

| % (N/total) | 76 (79/104) | - | - | |

| Statistical analysis | G-test = 0.1397; p = 0.7085a | F = 1.7470; p = 0.2140b | F = 0.2127; p = 0.6577c | |

NI not informed

aComparison of adenovirus positivity in WTP × urban drainage channels

bAdenovirus positivity × pH

cAdenovirus positivity × precipitation

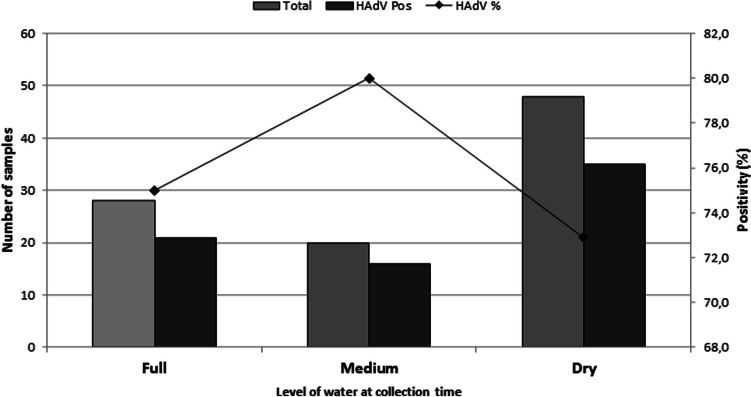

Variations in the water volume level at the time of collection (dry, medium, and full) are shown in Figure 2, and they did not influence on the HAdV positivity obtained (G = 0.3762; P = 0.8285).

Fig. 2.

Variation in water volume level at the time of collection and positivity obtained for HAdV in eight urban drainage channels in a large Amazon city, Brazil, January to December 2021

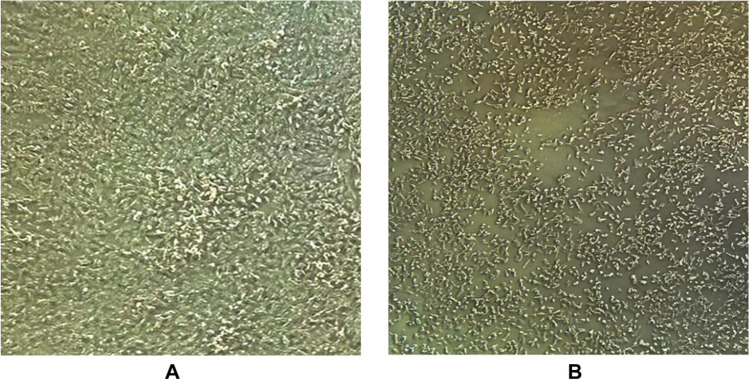

Regarding cell culture, eight HAdV positive samples from UDC (N = 7) and WTP (N = 1) were inoculated. These samples demonstrated the following qPCR CTs, 27.0 (PT01); 30.8 (PT02); 31.0 (PT03); 27.1 (PT05); 31.4 (PT06); 31.3 (PT07); 29.9 (PT08); and 34.4 (WTP). After the fourth passage, four samples showed a change in the structure of the cell layer 7 days of inoculation (Fig. 3). The second, third, and fourth passage of these cells were subjected to qPCR, but all showed negative results.

Fig. 3.

Continuous line A549 cells (adenocarcinoma human alveolar basal epithelial cells) observed under an inverted optical microscope at ×10 magnification. A Normal, non-inoculated cell layer (cell control) eighth day of isolation, fourth passage. B Cell inoculated with adenovirus (HAdV) showing cytopathic effect after the fourth passage, eighth day of isolation

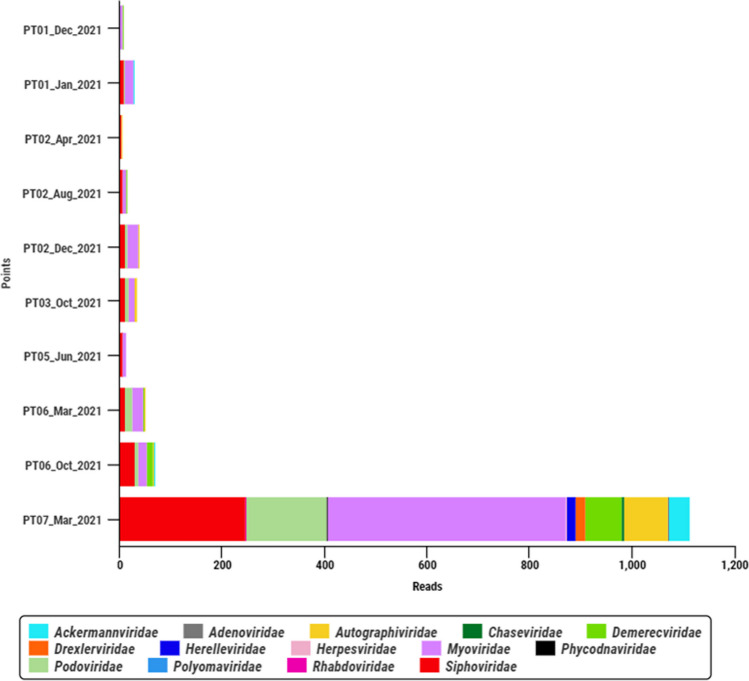

Sequencing by NGS using the metagenomic approach was performed on samples that presented satisfactory quantification (approximately 50 ng of DNA), and covered the following collection points: PT01, PT02, PT03, PT05, PT06, and PT07. The sequencing generated 16,706,595 reads and a total of 14 different viral families of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses were identified. The bacteriophage families Myoviridae (41% of available reads), Siphoviridae (24.5%), Podoviridae (14.1%), and Autographiviridae (6.9%) were the most abundant, with more than 85% of the total reads identified (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Most abundant viral families detected in the 10 wastewater samples from six urban drainage channels in a large Amazon city, Brazil, January to December 2021

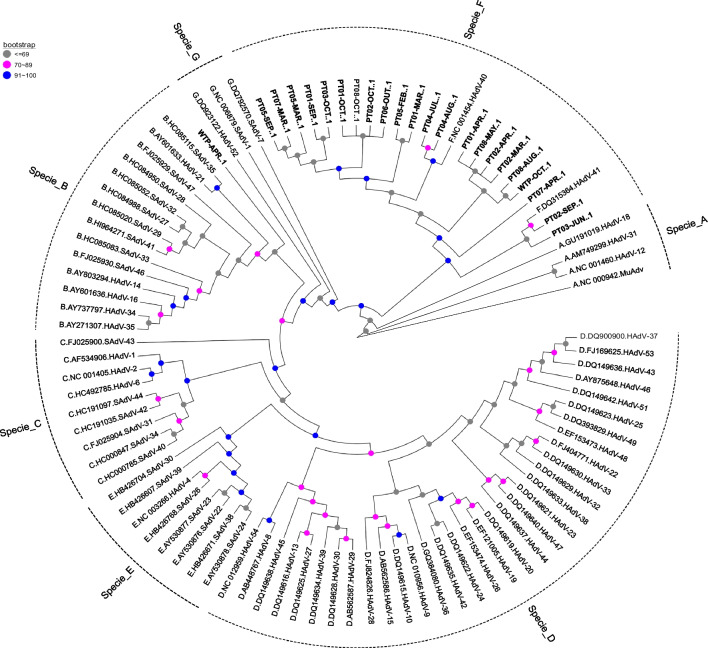

Of the 79 HAdV positive samples, 23 (29.1%) were sequenced by the Sanger method. The phylogenetic tree of the hexon gene demonstrated that the strains detected in this study were classified as species F type 40 (87%—20/23); species F type 41 (8.7%—2/23), and species B (4.3%—1/23) (date accessed on the GenBank: OR105914; OR105915; OR105916; OR105917; OR105918; OR105919; OR105920; OR105921; OR105922; OR105923; OR105924; OR105925; OR105926; OR105927; OR105928; OR105929; OR105930; OR105931; OR105932; OR105933; OR105934; OR105935; OR105936 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree for human adenovirus constructed from a partial region of the hexon gene (size = 482 bp), related to wastewater samples from eight urban drainage channels and one wastewater treatment plant of a large Amazon city, Brazil, January to December 2021, using the maximum likelihood method, using GTR as a nucleotide substitution model of 1000 bootstrap replicates. Study samples are marked in bold. The accession numbers are OR105914-OR105936

Discussion

The city of Belém have many channels that drain water from the center to the riverbanks, and that receive raw sewage due to the lack of an efficient sewage treatment system. Currently, only 17.12% of the city has domestic sewage collection, occupying the sixth worst position among all Brazilian municipalities [28].

This scenario contributes to the contamination of water bodies that receive waste from this sewage, compromising the health of the population in the surrounding [1]. Research on HAdV in wastewater is necessary to show the circulation of these viruses in the population, taking into account that they are eliminated in the feces [29].

The results of this study demonstrated that HAdV was present throughout the year in almost all sampling points. Studies have already shown that this virus is much more abundant in wastewater and occurs in higher concentrations (1000 times or more) than other enteric viruses [30, 31].

A study carried out by Rigotto [32] in samples from various water sources, including urban sewage, corroborated with our study and demonstrated that HAdV was detected almost all year round in the environment. Schlindwein et al. [33] stated that the high percentage of positive samples for HAdV distributed during the study period (June 2007 to May 2008) indicated that there was no occurrence of defined seasonality, since this virus was excreted throughout the year.

Similar results regarding the high positivity found in this study were also obtained by Rodrigues et al. [34] when they tested a total of 123 water samples collected at seven points along the Rio dos Sinos watershed, southern Brazil, from March to December 2011, 59 from treated water and 64 from untreated water with HAdV positivity of 74.6% (44/59) and 75% (48/64), respectively. Furthermore, Gonella et al. [31] also identified 73% positivity in surface water of a stream in Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo. More recently, Nour et al. [35] found a percentage of 61.1% in a WTP located in Saudi Arabia.

The high positivity rate observed for HAdV in the WTP reveals the existence of flaws in the treatment process for viruses removal. The WTP works only with a mixed system (aerobic and anaerobic), containing preliminary treatment, followed by an Anaerobic Sludge Blanket Reactor (UASB), a submerged aerated biofilter and a secondary decanter. According to Gerba et al. [36] for virus reduction to different levels of regulatory control, more advanced treatments are needed, such as chemical clarification, reverse osmosis, ultrafiltration, and advanced oxidation. Pointing out that the WTP constantly receives water from the canals in the center of the city, contributing to the large accumulation of viruses at that point, in addition, when we individually compare the waters of the UDC with that of the WTP, we do not find major differences in relation to positivity for HAdV (being found up to with more contamination compared to other UDC) reinforcing that its treatment is not effective for viruses.

Sampling points PT01 and PT02 were the ones with the highest frequency of positivity for HAdV. These channels are located in less favored areas of the city, which do not receive frequent maintenance and have compromised structure and silting. These are areas where the accumulation of debris and rubbish reveal the existence of precarious sanitation conditions.

In this study, adenoviruses were detected regularly throughout the period; therefore no relationship was observed between precipitation and the water level in the channels at the time of collection, with the positivity rate for HAdV. Studies have already shown that precipitation levels can influence in the circulation of enteric viruses and that probably the detection of viruses in the environment may be impaired after rainy events, due to the high viral dilution with the increase in water levels, as well as it may be favored in periods of drought where there is a higher concentration of these viral particles and greater danger of contamination [37–40]. However, this data was not observed in our study because the HAdV showed little change in their positivity in relation to seasonal trends throughout the year.

The pH values found varied between acid (6.9) and basic (7.6). This physical-chemical parameter can be changed by the influence of tides and precipitation, but this association was not observed in our study. The values obtained are in accordance with the current Brazilian legislation [41], which determines a pH variation of 5 to 9 for the release of effluents into the receiving body.

The F specie of HAdV types 40 (11%) and HAdV-41 (83.5%) were also the most frequent in sewage samples collected in Sydney and Melbourne, Australia [42]. In a research conducted by Ogorzaly et al. [5], involving and the effluents of four Luxembourgish WTP HAdV-41 were considered the most abundant in the tested samples. Iaconelli et al. [43] identified HAdV-41 in Italy in a 1 year of monitoring 22 WTP, with a higher frequency than the other genotypes.

The HAdV-F is already well recognized as one of the main causes of acute gastroenteritis in children. In clinical samples from children with gastroenteric symptoms from Brazil and Bangladesh, it was identified a prevalence of 43.9% and 54.8%, respectively [44, 45].

More recently, the HAdV-F was associated with cases of acute hepatitis of unknown etiology, requiring liver transplantation in more severe cases [11]. However, the role of HAdV in these cases has not yet been well defined and further studies involving the pathogenesis of this illness are necessary [12].

One sample was identified as HAdV-B which is commonly associated with acute respiratory illness. Bibby and Peccia [46] identified that the most abundant HAdV species in samples of sewage sludge in the USA were HAdV-C (78%) and B (20%), highlighting the importance of identifying respiratory HAdV in human populations, suggesting a surveillance of these viruses in sewage, as is already done for other respiratory viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 [47].

In the present study, after submitting the inoculated A549 cell culture to the qPCR technique for HAdV, no positivity was verified, although several studies point to this lineage as an excellent HAdV replicator, including enteric ones (HAdV-40 and -41) [48–51]. The absence of viral replication observed may be a consequence of the following: (i) the small amount of viral particles and/or viable viruses in the evaluated environmental matrices; (ii) large amount of cytotoxic inhibitors and interferents contained in the environmental samples; (iii) the fastidious nature of HAdV-40 and -41 and their difficult replication in cell lines in vitro; and (iv) growth of other viruses that can also grow in the A549 cell [48].

Metagenomics was used to determine viral composition and diversity in UDC wastewater samples. However, some difficulties were found that may be considered a limitation of this study, such as the lack of prior treatment in the wastewater samples, which contain many molecular inhibitors, which may have interfered with sequencing coverage. It was not possible to evaluate such inhibitors in this study due to the unavailability of a protocol for this analysis.

All viral sequences identified were from double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) virus. In fact, there is evidence that dsDNA viruses are more abundant than single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses in water samples [52]. The most abundant viral families found were bacteriophages of the order Caudovirales (Myoviridae, Autographiviridae, Podoviridae, and Siphoviridae), frequently described in environmental matrices [53–56].

Recently, a new viral order named Tubulavirales was proposed containing new families which were found in our study, highlighting the following: Autographiviridae whose members infect bacteria of the classes Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria, and the phylum Cyanobacteria; Demerecviridae which has Aeromonas, Escherichia, Klebsiella, Proteus, Salmonella, Shigella, Vibrio, and others as hosts; and the Drexlerviridae whose hosts are members of the class Gammaproteobacteria [57]. Studies show that bacteriophages are important for the renewal of organic matter and increase bacterial diversity, in addition, their detection is related as an important indicator of fecal contamination [53, 58].

One sample (PT07 from March 2021) submitted to metagenomics stood out among the others in terms of the reads number and diversity of viral families obtained. This sampling point is geographically located close to two large water bodies that surround the city (Baía do Guajará e Rio Guamá) and in the rainiest period (March, for example) it is common to be constantly flooded. The mixing of rainwater with river water during these floods may have favored the entry of viruses composing the natural virioplankton of these ecosystems, contributing to the greater diversity in this specific sample.

Conclusion

This study showed a high frequency of HAdV, an enteric virus of interest to Public Health, using molecular techniques (qPCR) and genotyping (SANGER sequencing). In addition, it showed the presence of bacteriophages that perform ecological functions within aquatic ecosystems, furthermore to indicating sources of fecal contamination. There was no relationship between the variables precipitation and level of water at the collection time and the HAdV positivity.

These findings demonstrate the risk to human health resulting from exposure to these waters and highlight the impact generated by the lack of sewage treatment and Public Policies aimed at protecting water bodies receiving effluents in the city of Belém. More studies aiming to analyze the viability of viral particles detected in water should be developed, to improve the evaluation of the microbiological quality of wastewater and aiming the adoption of policies that improve handling prior to release into natural aquatic environments.

Acknowledgements

We thank Instituto Evandro Chagas (Ministry of Health) Brazil for the technical and scientific support in carrying out this work; the Fundação Amazônia de Amparo a Estudos e Pesquisas (FAPESPA), National Council for Scientific and Technological Development of Brazilian Institutes (CNPq/Brasil), and Foundation for Scientific and Technological Development in Health (FIOTEC - Project VPGDI-047-FIO-20) by LCPNC, GJLP, JAMS, are the scholarship recipients; to the Environment and Virology technicians and collaborators for their assistance during sample collection and processing; to the leadership of SAVIR for scientific support; and to the graduate program in Parasitic Biology in the Amazon of the State University of Pará for the support and opportunity during the doctorate degree (LCPNC).

Author contribution

LCPNC: prepared the manuscript, analyzed, and performed the laboratory tests; LDS: reviewed the manuscript and analyzed the results; DMT and JAMS: performed the laboratory tests, reviewed the manuscript, and analyzed the results; ECSJ: provided support for phylogenetic analysis of the detected samples; JLF and GJLP: performed the laboratory tests; and YBG: reviewed the manuscript, analyzed the applied methodology and results, and was involved in general discussions with the first author. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Evandro Chagas Institute, Brazilian Ministry of Health.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

All authors gave formal consent to participate to the study.

Consent for publication

All the authors agreed to publish the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tourinho HLZ, Lopes MSB, Vieira MRS, Cabral ACLC (2021) City’s master plan of Belém (PA) and water urban rives. Res Soc Dev. 10.33448/rsd-v10i10.19159

- 2.Bányai K, Estes MK, Martella V, Parashar UD. Viral gastroenteritis. Lancet. 2018;392:175–186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31128-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong TT, Lipp EK. Enteric viruses of humans and animals in aquatic environments: health risks, detection, and potential water quality assessment tools. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:357–371. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.2.357-371.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grondahl-Rosado RC, Yarovitsyna E, Trettenes E, Myrmel M, Robertson LJ. A one year study on the concentrations of norovirus and enteric adenoviruses in wastewater and a surface drinking water source in Norway. Food Environ Virol. 2014;6:232–245. doi: 10.1007/s12560-014-9161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogorzaly L, Walczak C, Galloux M, Etienne S, Gassilloud B, Cauchie HM. Human adenovirus diversity in water samples using a next-generation amplicon sequencing approach. Food Environ Virol. 2015;7:112–121. doi: 10.1007/s12560-015-9194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JS, Lee SK, Ko DH, Hyun J, Kim HS, Song W, Kim HS (2017) Associations of adenovirus genotypes in Korean acute gastroenteritis patients with respiratory symptoms and intussusception. Biomed Res Int. 10.1155/2017/1602054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Tahmasebi R, Luchs A, Tardy K, Hefford PM, Tinker RJ, Eilami O, de Padua Milagres FA, Brustulin R, Teles MDAR, Dos Santos MV, Moreira CHV, Buccheri R, Araújo ELL, Villanova F, Deng X, Sabino EC, Delwart E, Leal É, Charlys da Costa A. Viral gastroenteritis in Tocantins, Brazil: characterizing the diversity of human adenovirus F through next-generation sequencing and bioinformatics. J Gen Virol. 2020;101:1280–1288. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Portal TM, Reymão TKA, Quinderé Neto GA, Fiuza MKDC, Teixeira DM, Lima ICG, Sousa Júnior EC, Bandeira RDS, De Deus DR, Justino MCA, Linhares ADC, Silva LDD, Resque HR, Gabbay YB. Detection and genotyping of enteric viruses in hospitalized children with acute gastroenteritis in Belém, Brazil: occurrence of adenovirus viremia by species F, types 40/41. J Med Virol. 2019;91:378–384. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Primo D, Pacheco GT, Timenetsky MDCST, Luchs A. Surveillance and molecular characterization of human adenovirus in patients with acute gastroenteritis in the era of rotavirus vaccine, Brazil, 2012-2017. J Clin Virol. 2018;109:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2018.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lefeuvre C, Salmona M, Feghoul L, Ranger N, Mercier-Delarue S, Nizery L, Alimi A, Dalle JH, LeGoff J (2021) Deciphering an adenovirus F41 outbreak in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients by whole-genome sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 10.1128/JCM.03148-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Baker JM, Buchfellner M, Britt W, et al. Acute hepatitis and adenovirus infection among children - Alabama, October 2021-February 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:638–640. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7118e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutierrez Sanchez LH, Shiau H, Baker JM, et al. A case series of children with acute hepatitis and human adenovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:620–630. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakim MS. The recent outbreak of acute and severe hepatitis of unknown etiology in children: a possible role of human adenovirus infection? J Med Virol. 2022;94:4065–4068. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grand RJ (2022) A link between severe hepatitis in children and adenovirus 41 and adeno-associated virus 2 infections. J Gen Virol 103. 10.1099/jgv.0.001783 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Servellita V, Sotomayor Gonzalez A, Lamson DM, et al. Adeno-associated virus type 2 in US children with acute severe hepatitis. Nature. 2023;617:574–580. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05949-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gholipour S, Ghalhari MR, Nikaeen M, Rabbani D, Pakzad P, Miranzadeh MB. Occurrence of viruses in sewage sludge: a systematic review. Sci Total Environ. 2022;10(824):153886. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorado G, Gálvez S, Rosales TE, Vásquez VF, Hernández P. Analyzing modern biomolecules: the revolution of nucleic-acid sequencing - review. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1111. doi: 10.3390/biom11081111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calgua B, Mengewein A, Grunert A, Bofill-Mas S, Clemente-Casares P, Hundesa A, Wyn-Jones AP, López-Pila JM, Girones R. Development and application of a one-step low cost procedure to concentrate viruses from seawater samples. J Virol Methods. 2008;153:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernroth BE, Conden-Hansson AC, Rehnstam-Holm AS, Girones R, Allard AK. Environmental factors influencing human viral pathogens and their potential indicator organisms in the blue mussel, Mytilus edulis: the first Scandinavian report. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:4523–4533. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.9.4523-4533.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muscillo M, Pourshaban M, Iaconelli M, Fontana S, Di Grazia A, Manzara S, Fadda G, Santangelo R, La Rosa G. Detection and quantification of human adenoviruses in surface waters by nested PCR, TaqMan real-time PCR and cell culture assays. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2008;191:83–93. doi: 10.1007/s11270-007-9608-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu W, McDonough MC, Erdman DD. Species-specific identification of human adenoviruses by a multiplex PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4114–4120. doi: 10.1128/JCM.38.11.4114-4120.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katoh K, Asimenos G, Toh H. Multiple alignment of DNA sequences with MAFFT. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;537:39–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-251-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, von Haeseler A, Lanfear R. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:1530–1534. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood DE, Lu J, Langmead B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):257. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ondov BD, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Interactive metagenomic visualization in a Web browser. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:385. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayres M, Ayres JRM, Ayres DL, Santos AS. BioEstat 5.0-Aplicações Estatísticas nas Áreas das Ciências Biológicas e Médicas. Belém, Brasília: Sociedade Civil Mamirauá, CNPq; 2007. p. 290. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Instituto Trata Brasil . Ranking do Saneamento do Instituto Trata Brasil de 2023 (SNIS 2021) 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumthip K, Khamrin P, Ushijima H, Maneekarn N. Enteric and non-enteric adenoviruses associated with acute gastroenteritis in pediatric patients in Thailand, 2011 to 2017. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0220263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitajima M, Iker BC, Pepper IL, Gerba CP (2014) Relative abundance and treatment reduction of viruses during wastewater treatment processes--identification of potential viral indicators. Sci Total Environ 488-489. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.04.087 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Gonella JM, Tonani KAA, Fregonesi BM, Machado CS, Trevilato RB, Zagui GS, Alves RIS, Muñoz SIS. Adenovírus e rotavírus em águas superficiais do córrego Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brasil / Adenovirus and rotavirus in surface water of the Ribeirão Preto stream, São Paulo, Brazil. Mundo Saúde. 2016;40:474–480. doi: 10.15343/0104-7809.20164004474480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rigotto C, Victoria M, Moresco V, Kolesnikovas CK, Corrêa AA, Souza DS, Miagostovich MP, Simões CM, Barardi CR. Assessment of adenovirus, hepatitis A virus and rotavirus presence in environmental samples in Florianopolis, South Brazil. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;109:1979–1987. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlindwein AD, Rigotto C, Simões CM, Barardi CR. Detection of enteric viruses in sewage sludge and treated wastewater effluent. Water Sci Technol. 2010;61:537–544. doi: 10.2166/wst.2010.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodrigues MT, Henzel A, Staggemeier R, de Quevedo DM, Rigotto C, Heinzelmann L, do Nascimento CA, Spilki FR. Human adenovirus spread, rainfalls, and the occurrence of gastroenteritis cases in a Brazilian basin. Environ Monit Assess. 2015;187:720. doi: 10.1007/s10661-015-4917-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nour I, Hanif A, Zakri AM, Al-Ashkar I, Alhetheel A, Eifan S (2021) Human adenovirus molecular characterization in various water environments and seasonal impacts in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 10.3390/ijerph18094773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Gerba CP, Betancourt WQ, Kitajima M, Rock CM. Reducing uncertainty in estimating virus reduction by advanced water treatment processes. Water Res. 2018;133:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xagoraraki I, Kuo DH, Wong K, Wong M, Rose JB. Occurrence of human adenoviruses at two recreational beaches of the great lakes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:7874–7881. doi: 10.1128/aem.01239-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sidhu JP, Hodgers L, Ahmed W, Chong MN, Toze S. Prevalence of human pathogens and indicators in stormwater runoff in Brisbane, Australia. Water Res. 2012;46:6652–6660. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerba CP. Virus occurrence and survival in the environmental waters. In: Bosch A, Zuckerman AJ, Mushahwar IK, editors. Human viruses in water. Oxford: Elsevier; 2007. pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipp EK, Kurz R, Vincent R, et al. The effects of seasonal variability and weather on microbial fecal pollution and enteric pathogens in a subtropical estuary. Estuaries. 2001;24:266–276. doi: 10.2307/1352950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brasil. Ministério do Meio Ambiente . Resolução Conama N° 430 DE 13 de Maio de 2011. Dispõe sobre as condições e padrões de lançamento de efluentes, complementa e altera a Resolução n° 357, de 17 de março de 2005, do Conama. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lun JH, Crosbie ND, White PA. Genetic diversity and quantification of human mastadenoviruses in wastewater from Sydney and Melbourne, Australia. Sci Total Environ. 2019;675:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iaconelli M, Valdazo-González B, Equestre M, Ciccaglione AR, Marcantonio C, Della Libera S, La Rosa G. Molecular characterization of human adenoviruses in urban wastewaters using next generation and Sanger sequencing. Water Res. 2017;121:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.do Nascimento LG, Fialho AM, JdSR d A et al (2022) Human enteric adenovirus F40/41 as a major cause of acute gastroenteritis in children in Brazil, 2018 to 2020. Sci Rep. 10.1038/s41598-022-15413-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Afrad MH, Avzun T, Haque J, Haque W, Hossain ME, Rahman AR, Ahmed S, Faruque ASG, Rahman MZ, Rahman M. Detection of enteric- and non-enteric adenoviruses in gastroenteritis patients, Bangladesh, 2012-2015. J Med Virol. 2018;90:677–684. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bibby K, Peccia J. Prevalence of respiratory adenovirus species B and C in sewage sludge. Environ Sci Process Impacts. 2013;15:336–338. doi: 10.1039/c2em30831b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martins RM, Carvalho T, Bittar C, Quevedo DM, Miceli RN, Nogueira ML, Ferreira HL, Costa PI, Araújo JP Jr, Spilki FR, Rahal P, Calmon MF (2022) Long-term wastewater surveillance for SARS-CoV-2: one-year study in Brazil. Viruses. 10.3390/v14112333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Hashimoto S, Sakakibara N, Kumai H, Nakai M, Sakuma S, Chiba S, Fujinaga K. Fastidious human adenovirus type 40 can propagate efficiently and produce plaques on a human cell line, A549, derived from lung carcinoma. J Virol. 1991;65:2429–2435. doi: 10.1128/JVI.65.5.2429-2435.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leonardi GP, Costello P, Harris P. Use of continuous human lung cell culture for adenovirus isolation. Intervirology. 1995;38:352–355. doi: 10.1159/000150463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee C, Lee SH, Han E, Kim SJ. Use of cell culture-PCR assay based on combination of A549 and BGMK cell lines and molecular identification as a tool to monitor infectious adenoviruses and enteroviruses in river water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6695–6705. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6695-6705.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cromeans TL, Lu X, Erdman DD, Humphrey CD, Hill VR. Development of plaque assays for adenoviruses 40 and 41. J Virol Methods. 2008;151:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roux S, Enault F, Robin A, Ravet V, Personnic S, Theil S, Colombet J, Sime-Ngando T, Debroas D (2012) Assessing the diversity and specificity of two freshwater viral communities through metagenomics. PLoS One. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Alanazi F, Nour I, Hanif A, Al-Ashkar I, Aljowaie RM, Eifan S (2022) Novel findings in context of molecular diversity and abundance of bacteriophages in wastewater environments of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. PLoS One. 10.1371/journal.pone.0273343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Korf IHE, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Adriaenssens EM, Kropinski AM, Nimtz M, Rohde M, van Raaij MJ, Wittmann J. Still something to discover: novel insights into Escherichia coli phage diversity and taxonomy. Viruses. 2019;11:454. doi: 10.3390/v11050454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Azam AH, Tanji Y. Bacteriophage-host arm race: an update on the mechanism of phage resistance in bacteria and revenge of the phage with the perspective for phage therapy. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;103:2121–2131. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-09629-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Potapov SA, Tikhonova IV, Krasnopeev AY, Suslova MY, Zhuchenko NA, Drucker VV, Belykh OI (2022) Communities of T4-like bacteriophages associated with bacteria in Lake Baikal: diversity and biogeography. PeerJ. 10.7717/peerj.12748

- 57.Adriaenssens EM, Sullivan MB, Knezevic P, et al. Taxonomy of prokaryotic viruses: 2018-2019 update from the ICTV bacterial and archaeal viruses subcommittee. Arch Virol. 2020;165:1253–1260. doi: 10.1007/s00705-020-04577-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Strange JES, Leekitcharoenphon P, Møller FD, Aarestrup FM. Metagenomics analysis of bacteriophages and antimicrobial resistance from global urban sewage. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1600. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-80990-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.