Abstract

While there are many studies on the relationship between anxiety disorders and childhood traumas in the literature, there are limited studies on the relationship between separation anxiety disorders and traumatic experiences in early life. It is widely known that trauma and negative cognitive processes are important factors in the etiology and prognosis of psychiatric disorders. In this study, it was aimed to determine the relationship between adult separation anxiety levels and childhood traumas and cognitive distortions, and to examine the mediating role of cognitive distortions in the relationship between childhood traumas and separation anxiety. A total of 366 students attending a private university were included in the study. The scales, which were converted into online questionnaires by the researchers, were sent to the students via e-mail, and were administered online. The participants were evaluated using “Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire”, “Childhood Trauma Questionnaire”, and “Cognitive Distortions Scale”. The results of the study indicated that there was a positive and significant relationship between adult separation anxiety levels and childhood sexual abuse while there was no statistically significant correlation between adult separation anxiety levels and physical and emotional abuse, or physical and emotional neglect. A positive and significant relationship was found between separation anxiety levels and the sub-dimensions of cognitive distortions’ self-image, self-blame, helplessness, hopelessness, and preoccupation with danger. In addition, it was determined that the helplessness and preoccupation with danger sub-dimensions of cognitive distortions had a full mediator effect on the relationship between sexual abuse and separation anxiety. Our results show that there is a positive relationship between separation anxiety disorder and childhood sexual abuse, and cognitive distortions play a mediating role between both variables.

Keywords: Separation anxiety, Childhood traumas, Cognitive distortions

Introduction

Separation anxiety refers to the state of intense anxiety or fear experienced by the individuals upon being separated from those people to whom they are closely attached. This type of anxiety, which is considered as periodically normal in children, is labelled as Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD) when it is severe enough to be developmentally inappropriate and affects daily life functioning (Koroglu, 2014). DSM-IV defines SAD as an anxiety disorder that is seen in childhood and adolescence beginning before the age of 18. However, the studies on this subject have reported similar symptoms and findings in adults (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Seligman & Wyulek, 2007; Shear et al., 2006). In the DSM-5, the criterion of being 18 years old for the onset of SAD was omitted, and the disorder was categorized under adult anxiety disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2014).

Although separation anxiety symptoms are not common, it was found in a prospective study on adolescents and young adults aged 17–24 years that its prevalence was 7.8% in a lifetime (Bruckl et al., 2006). Shear et al. (2006) reported SAD prevalence in adults as 6.6%. The studies on the etiology of adulthood SAD indicated the roles of genetic and environmental factors (Alkin, 2010; Scaini et al., 2012). The clinical studies on the subject investigated comorbid psychiatric diseases and particularly panic disorder, family history of psychiatric disorders, gender, cultural characteristics, temperamental aspects, adult attachment style (i.e., insecure attachment), psychosocial challenges in childhood, and lifelong traumas including childhood, as factors that could be associated with SAD (Manicavasagar et al., 2009; Demir and Gorgulu, 2020; Mertol and Alkin, 2012; Boelen et al., 2014). There are studies showing that SAD is associated with childhood traumas (Olmez et al., 2022; Namli et al., 2022).

Childhood traumas can be generally defined as negative life events including emotional, physical, sexual abuse and/or neglect that an individual is exposed to before turning eighteen, as well as loss of parents, migration, war, accidents and natural disasters that an individual experiences at an early age (Herman, 2011). It is known that childhood traumas are associated with various psychiatric disorders in adults such as anxiety disorders, depression, suicidal behavior, substance abuse, and dissociative disorder (Erol et al., 2013; Hovens et al., 2010; Pietrek et al., 2013; Mandelli et al., 2015; Orsel et al., 2011). An important effect of trauma on mental health is that it negatively affects cognitive processes (Bremner et al., 2000). Many researchers try to explain the effects of childhood traumas on mental health with a cognitive behavioral approach (Shelby, 2010; Ready et al., 2015).

The basic principle of cognitive therapy is based on the assumption that an individual’s cognition (thoughts) and emotions have an impact on their behaviors (Beck, 2001). Inappropriate affect in psychiatric diseases is explained by cognitive processes (Beck et al., 1985). Beck (1976) cognitive structure, cognitive schemas, cognitive distortions, cognitive defines it as triple and automatic thoughts. Cognitive schemas are shaped by past events and affect the perception and interpretation of current events. Cognitive distortions occur when the cognitive schema is negative. Cognitive distortions are described as false thoughts that occur in the wrong and dysfunctional processing of information. Cognitive distortions; all or nothing style thinking, selective abstraction, emotional reasoning, mind reading, catastrophizing, extreme generalization, labeling, extreme magnification, reduction, personalize, categorize with must-have sentences (Beck, 2001, 2011). Of the person as a result of cognitive distortions; seeing the future negatively, developing a negative self-perception, living the world negative attitude that presents obstacles in the way of achieving its goals seeing it as the environment forms the cognitive triad (Possel & Thomas, 2011). Cognitive distortions automatic thoughts caused by personal and specific the first word/image that comes to mind and serial thoughts. These automatic thoughts are unreal and if it is dysfunctional, the individual himself and his environment cause a negative assessment of they can be (Turkcapar, 2014). Cognitive schemas, cognitive distortions, cognitive triad including automatic thoughts it is argued that the negative content of structures has a causal relationship with many mental illnesses, especially depression and anxiety disorders (Beck, 2008, 2011; Possel & Thomas, 2011; Weems et al., 2001; Coban & Karaman, 2013). Cognitive distortions may also play a role in adult separation anxiety disorder. For example, avoiding intimacy and the existence of cognitive distortions about relationships can increase the level of adult separation anxiety (Basbug et al., 2017).

While there are many studies examining the relationship between anxiety disorders and childhood traumas in the literature, the number of studies examining the relationship between SAD and traumatic experiences in early life are limited (Hovens et al., 2010; Pietrek et al., 2013; Orsel et al., 2011; Fernandes & Osório, 2015; Gul et al., 2016; Gulcu Ok, 2017). It has been known that trauma and negative cognitive processes are important factors in the etiology and prognosis of psychiatric disorders. Considering the prevalence of separation anxiety signs and symptoms in adults and their negative effects on the quality of life, it is considered to be important to examine the factors associated with adult SAD in detail. In this study, it was aimed to determine the relationship between adult separation anxiety levels and childhood traumas and cognitive distortions, and to examine the mediating role of cognitive distortions in the relationship between childhood traumas and separation anxiety.

Method

Participant

366 students selected by simple random sampling method among students studying at a private university in Istanbul in the 2020–2021 academic years were included in the study. The scales, which were converted into an online questionnaire, were sent to 385 students via e-mail. 371 of the students filled out the questionnaires. Five of the participants were not included in the study because the necessary data were missing. The required minimum sample sizes were calculated by G*Power (3.1.9.4) analysis against the entered nominal significance level (α = 0.5) and power value (1-β = 0.8 and 1-β = 0.9). Two-way analysis was performed considering that the correlation could be positive or negative. Since a larger effect size is expected on the G*Power screen, 0.5 was entered in the “Correlation H1” part and 0.3 was entered to see the result with medium effect size. On the other hand, “Correlation H0” was written as 0 since it was tested whether the correlation value was 0 (whether the relationship was significant or not). As a result of the evaluation, the required minimum sample size (n) was found to be 112. Inclusion criteria were determined as being 18 years or older, and volunteering to participate in the study.

Evaluation Tools

A Sociodemographic Data Form was prepared by the researchers, consisting questions demographic characteristics such as the participant’s age, gender and grade.

Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire (ASA) was developed by Manicavasagar et al. (2009) to evaluate separation anxiety symptoms in adults. ASA is a 27-item, 4-point Likert- type self-report scale. Turkish validity and reliability studies of the scale were conducted by Dirioz et al. (2012).

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) was developed by Bernstein (1994) questions childhood neglect and abuse in adults. CTQ is a 28-item, 5-point Likert-type self-report scale. CTQ has five subscales: “Sexual Abuse”, “Physical Abuse”, “Emotional Abuse”, “Physical Neglect” and “Emotional Neglect”. Turkish validity and reliability studies of the scale were conducted by Sar et al. (2012).

Cognitive Distortions Scale (CDS) was developed by Briere (2000), and questions the dysfunctional cognitive thoughts of individuals. CDS is a 40-item, 5-point Likert-type self- report scale. CDS has five subscales: “Self-Perception”, “Self-Blame”, “Helplessness”, “Hopelessness”, and “Preoccupation with Danger”. Turkish validity and reliability studies of the scale were performed by Agir and Yavuzer (2018).

Procedure

The ethical approval was obtained from the university committee. The scales were converted into online questionnaires by the researchers, and were sent to the students via e-mail. Initially, an informative form about the research was sent to the students, and their consent was obtained for participation in the study. All the scales were administered online and simultaneously, and were completed in a single session lasting approximately 20 min.

Statistical Analysis

All the data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) Windows version 22.0 software. The relationship of ASA scores with CTQ and CDS was analyzed with the “Pearson correlation test”. The mediating effect of CDS between ASA and CTQ was tested using the “causal steps approach” method of Baron and Kenny (1986). The statistical significance of the mediating effect of CDS was analyzed using the bootstrap method as suggested by Preacher and Hayes (2008).

Results

312 (85.2%) of the participants were female and 54 (14.8%) of them were male. The average age ranged between 21.66 ± 1.76 years. Sixty-seven students (18.3%) were in the 1st year, 70 (19.1%) in the 2nd year, 117 (32.0) in the 3rd year, and 112 (30.6%) in the 4th year.

The mean ASA, CTQ, and CDS scores of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The mean scores of the participants’ ASA, CTQ, and CDS

| Min | Max | Mean | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA | 1.00 | 79.00 | 29.10 | 14.85 | |

| CTQ | Emotional Abuse | 5.00 | 25.00 | 8.26 | 3.74 |

| Physical Abuse | 5.00 | 23.00 | 5.79 | 2.11 | |

| Sexual Abuse | 5.00 | 22.00 | 6.36 | 3.07 | |

| Emotional Neglect | 5.00 | 24.00 | 10.78 | 4.42 | |

| Physical Neglect | 5.00 | 16.00 | 6.40 | 1.82 | |

| Total CTQ | 25.00 | 83.00 | 37.61 | 10.85 | |

| CDS | Self Perception | 9.00 | 40.00 | 18.50 | 6.20 |

| Self-Blame | 7.00 | 35.00 | 16.24 | 5.67 | |

| Helplessness | 8.00 | 40.00 | 18.80 | 6.65 | |

| Hopelessness | 8.00 | 39.00 | 17.22 | 7.72 | |

| Preoccupation with Danger | 8.00 | 40.00 | 19.46 | 6.68 |

ASA: Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire; CTQ: Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; CDS: Cognitive Distortions Scale

When the relationship between ASA scores and total and subscale scores of CTQ was examined, a positive but weak significant relationship was found between ASA scores and Sexual Abuse subscale (p < 0.05). No significant correlation was found between ASA scores and scores of Physical Abuse, Emotional Abuse, Physical Neglect, Emotional Neglect subscales, or total CTQ scores (p > 0.05). When the relationship between ASA scores and CDS subscale scores was examined, a positive but weak significant relationship was determined between ASA scores and Self Perception subscale scores (p < 0.01). ASA scores were positively and moderately correlated with the scores of Self-Blame, Helplessness, Hopelessness, and Preoccupation with Danger subscales (p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients between the variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional Abuse | - | 0.55** | 0.49** | 0.17** | 0.70** | 0.87** | 0.01 | 0.41** | 0.38** | 0.44** | 0.33** | 0.41** |

| 2. Physical Abuse | - | 0.33** | 0.00 | 0.40** | 0.60** | − 0.01 | 0.24** | 0.24** | 0.22** | 0.18** | 0.26** | |

| 3. Physical Neglect | - | 0.09 | 0.57** | 0.66** | 0.03 | 0.28** | 0.24** | 0.25** | 0.22** | 0.31** | ||

| 4. Sexual Abuse | - | 0.14* | 0.41** | 0.11* | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.12* | 0.07 | 0.23** | |||

| 5. Emotional Neglect | - | 0.86** | − 0.00 | 0.47** | 0.36** | 0.46** | 0.38** | 0.42** | ||||

| 6. Total CTQ | - | 0.03 | 0.45** | 0.39** | 0.46** | 0.36** | 0.48** | |||||

| 7. ASA | - | 0.28** | 0.42** | 0.36** | 0.32** | 0.42** | ||||||

| 8. Self Perception | - | 0.72** | 0.67** | 0.70** | 0.67** | |||||||

| 9. Self-Blame | - | 0.72** | 0.70** | 0.76** | ||||||||

| 10. Helplessness | - | 0.86** | 0.73** | |||||||||

| 11. Hopelessness | - | 0.70** | ||||||||||

| 12.Preoccupation with Danger | - |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, Pearson Correlation Test; CTQ: Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; ASA: Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire

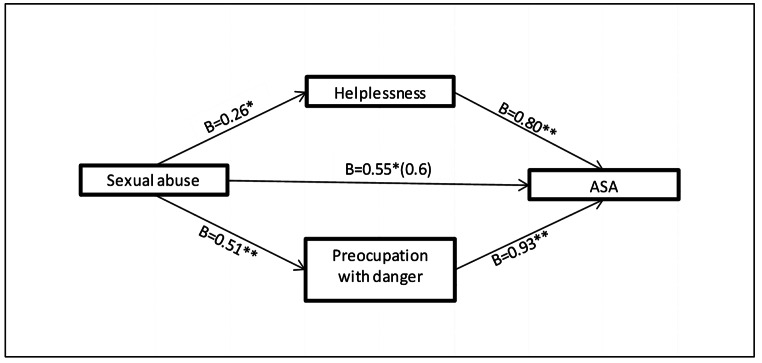

The mediating role of cognitive distortions in the relationship between sexual abuse and ASA levels was examined in line with the three rules proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986). The first rule suggests that ASA should be significantly correlated with sexual abuse and cognitive distortions, both of which are independent variables. The second rule suggests that cognitive distortions which are the mediating variables should be associated with sexual abuse and ASA. The third rule suggests that there should be a decrease in the quality of relationship between the two variables when the mediator variable is controlled. A decrease in the quality of the relationship is accepted as an indicator of a partial mediating effect, and the loss of significance of the relationship is accepted as an indicator of a full mediating effect. In case of meeting the necessary criteria, the mediating effects of the CDS’s Helplessness and Preoccupation with Danger subscales were tested in the established model on the relationship between sexual abuse and ASA levels. Three separate regression equations presented in Fig. 1 were created. According to the results of the regression analysis, sexual abuse has a direct and significant effect on ASA levels (B = 0.54; t = 2.16; p < 0.05). It is seen that sexual abuse significantly and directly predicts the mediating variables of helplessness (B = 0.26; t = 2.38; p < 0.05) and preoccupation with danger (B = 0.51; t = 4.63; p < 0.01). When the variables of helplessness and preoccupation with danger were added to the model, the effect of the sexual abuse variable lost its significance on ASA. Helplessness (B = 0.80; t = 7.30; p < 0.01) and preoccupation with danger (B = 0.93; t = 8.64; p < 0.01) play full mediator roles in the relationship between sexual abuse and ASA (B = 0.80; t = 7.30; p < 0.01) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The mediator roles of helplessness and preoccupation with danger subscales in the relationship between sexual abuse and ASA levels. *p < 0.05,**p < 0.001; ASA: Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire

Significance levels of the effects of mediating variables were examined using the bootstrap method. Bootstrap is a non-parametric method based on resampling many times (1000 or 5000) by displacement method, based on the research sample. The indirect mediation effect is calculated for each new sample. The significance of the mediation effect is determined by calculating the confidence interval, best-known parameter, and whether there is zero in this interval. The absence of zero in the confidence interval indicates that the indirect effect is different from zero. As suggested by Preacher and Hayes (2008), the effects of mediating variables on a 1000-person bootstrap sample were examined. The results indicated that the mediating effects of the subscales of helplessness (B = 0.21, 95% BCa CI [0.03–0.45]) and preoccupation with danger (B = 0.48, 95% BCa CI [0.28–0.71]) were significant.

Discussion

The results of our study indicated a positive and significant correlation between adult separation anxiety levels and childhood sexual abuse, and there was no statistically significant relationship between adult separation anxiety levels and physical and emotional abuse, or physical and emotional neglect. A positive and significant relationship was found between separation anxiety levels and the sub-dimensions of cognitive distortions’ self-image, self-blame, helplessness, hopelessness, and preoccupation with danger. In addition, it was determined that the helplessness and preoccupation with danger sub-dimensions of cognitive distortions had a full mediator effect on the relationship between sexual abuse and separation anxiety.

Childhood abuse and neglect is an important health problem that paves the way for the emergence of many psychiatric diseases in adulthood. Only few studies in the literature examined the relationship between childhood traumas and SAD (Baldwin et al., 2016). In a large epidemiological study by Silove et al. (2015), it was determined that SAD starting before and after the age of 18 years was associated with negative childhood experiences and a lifelong trauma level. In a cross-sectional study conducted with 230 immigrant groups to examine the effects of trauma on separation anxiety symptoms, the level of lifelong trauma including childhood was found to be significantly higher in the patient group with SAD (Tay et al., 2016). In the present study, a significant relationship was found between only sexual abuse among childhood traumas, and SAD symptom levels, but no significant relationships were found between physical and emotional abuse, physical and emotional neglect and SAD symptoms. The results of the studies examining the relationship between childhood traumas and psychiatric diseases are conflicting. A recent study conducted on 635 university students in Turkey examined the relationship between childhood traumas and psychopathology, and did not find any significant difference between the groups with and without a psychiatric diagnosis in terms of childhood traumas (Dereboy et al., 2018). In a study conducted by Gibb et al. (2007), 857 patients diagnosed with anxiety disorder and depression were evaluated, and a significant relationship was found between childhood traumas and depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and social phobia, while there was no significant correlation with generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder. A large study by Cougle et al. (2010) found that exposure to sexual abuse was associated with generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and panic disorder in women, however physical abuse was only associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and specific phobia. The conflicting results on the relationship of childhood traumas with psychiatric disorders may be related to post-traumatic growth. Researchers have observed some positive psychological developments in individuals after traumatic experiences. Post- traumatic growth refers to the positive psychological development that happens as a result of the cognitive, emotional and behavioral transformation occurring in the process of the struggle of the person with the traumatic event (Sawyer & Ayers, 2009; Shakespeare-Finch & Allysa, 2012). In this study, no relationship was found between childhood traumas other than sexual abuse and SAD symptom levels, and it is possible that post-traumatic growth might have had a protective effect on psychopathologies. The studies examining the childhood and lifetime effects of trauma have shown that the repetition of traumatic experiences in adolescence and/or later are significantly correlated with the development of psychopathology (Classen et al., 2005). The fact that only childhood traumas were examined in our study may be an important limitation as well as another reason for not finding a relationship with SAD symptom levels.

Although many studies in the literature have examined cognitive distortions in SAD in childhood, studies on adults are limited (Bogels et al., 2013). In a study conducted in Turkey on the subject, 444 university students with a mean age of 21 years were examined to evaluate the mediating role of interpersonal cognitive distortions on SAD, and it was found that the avoidance of intimacy and unrealistic relationship expectation sub-dimensions of the cognitive distortion scale predicted separation anxiety symptoms (Basbug et al., 2017). The results of our study indicated that SAD symptom levels were positively and significantly correlated with the self-perception, helplessness, hopelessness, self-blame and preoccupation with danger sub-dimensions of cognitive distortions. The “self-perception dimension” of cognitive distortions indicate the negative and low self-perception of individuals and dissatisfaction with themselves, the “self-blame dimension” shows the excessive responsibility and guilt about the results of the events, the “helplessness sub-dimension” indicates the meaninglessness of the effort to produce a change related to the course and outcome of events, “hopelessness sub-dimension” characterizes pessimistic negative perceptions and evaluations about the future, and “preoccupation with danger sub-dimension” shows the beliefs that they will have negative experiences and may be harmed by others (Briere, 2000). Negative self-perception, hopelessness, helplessness, guilt, seeing life in danger may cause an individual to experience the situation more sadly and anxiously than usual during separation from the people to whom he/she is attached. Separation with the person to whom he/she is attached may lead to the thought that the individual cannot cope with this situation, triggering the emergence of separation anxiety symptoms.

In this study, it was found that sexual abuse had a direct and significant effect on SAD symptoms, and when the helplessness and preoccupation with danger sub-dimensions of cognitive distortions were controlled, the effect of sexual abuse on SAD symptoms lost its significance. In other words, it was determined that helplessness and life-threatening cognitive distortions played a full mediating role in the relationship between sexual abuse and SAD symptoms. Various studies have shown that childhood traumas negatively affect the self-perception and perception of others, resulting in early maladaptive schemas and cognitive distortions. In a study conducted on 1102 university students, it was reported that childhood traumas negatively affected cognitive processes, and directly predicted early maladaptive schemas (Gong & Chan, 2018). Similarly, another study conducted on 439 university students with an average age of 22 years found a positive and moderately significant relationship between the participants’ early maladaptive schemas and their childhood trauma levels (Rezaei & Ghazanfari, 2016). The results suggest that sexual abuse experienced in childhood affects the cognitive structure of individuals, causing helplessness and seeing life as dangerous. Hopelessness and seeing life in danger may lead individuals to perceive the separation from their attached people as a dangerous situation, and feel insecure. It is an expected situation to show anxiety symptoms to feel helpless when an individual perceives himself/herself in danger during separation.

Strengths and Limitations

There are some limitations of our study. The fact that the sample group of this study was selected from the students studying at a private university can be considered as a limitation. However, considering the financial conditions of the private higher educational institutions in Turkey and the income status of the students participating in the study, the results obtained from the sample are considered to be generalizable. Evaluation of the SAD symptom levels of the participants with only self-reported scales, and the lack of diagnostic evaluation is a limitation. In addition, the fact that only the childhood traumas, but not lifetime traumas of the participants were evaluated, is supposed to be an important limitation.

Clinical Implications

The results of our study show that there is a significant relationship between childhood sexual abuse and separation anxiety disorder levels and those cognitive distortions have a full mediator effect on the helplessness and preoccupation with danger sub-dimensions in the relationship between both variables. Studies examining the relationship between separation anxiety disorder and childhood traumas and cognitive distortions in adults are limited in the literature. In addition, no study examining the mediating role of cognitive distortions in the relationship between both variables was found. Our study is thought to be important in this respect. Although our results suggest that the history of childhood sexual abuse and cognitive characteristics should be considered in the clinical evaluation of patients with separation anxiety disorder, longitudinal studies on the subject are considered necessary for a better interpretation of our results.

Authors’ Contributions

M.C. and O.S. conceptualised and designed the study, collected the data. O.S. wrote the article. M.C. and A.D. supervised the study and helped in the writing of the article. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

Ethical Considerations

Ethics committee approval of the study was obtained from Beykent University Social and Human Sciences Ethics Committee, on July 01, 2020.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this research.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agir MS, Yavuzer H. Cognitive distortion scale turkish form: Reliability and validity study. Mediterranean Journal of Educational Research. 2018;12:175–198. doi: 10.29329/mjer.2018.172.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alkin T. Adult separation anxiety disorder. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;3:53–63. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2014). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). In Koroglu E (Ed.), Hekimler Yayın Birliği.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Baldwin DS, Gordon R, Abelli M, Ogliari A, Tambs K, Spatola The separation of adult separation anxiety disorder. CNS Spectrums. 2016;21:289–294. doi: 10.1017/S1092852916000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basbug S, Cesur G, Durak Batigun A. Perceived parental styles and adult separation anxiety: The mediating role of interpersonal cognitive distortions. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;28:255–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the Emotional Disorders. Oxford, UK: International Universities Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, J. S. (2001). In H. Sahin (Ed.), Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and Beyond. Turk Psikologlar Dernegi Yayinlari.

- Beck AT. The evolution of the cognitive model of depression and its neurobiological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:969–977. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS. Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. 2. New York: The Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. T., Emery, G., & Greenberg, R. L. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. Basic Books.

- Boelen PA, Reijntjes A, Carleton RN. Intolerance of uncertainty and adult separation anxiety. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2014;43:133–144. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2014.888755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogels SM, Knappe S, Clark LA. Adult separation anxiety disorder in DSM-5. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:663–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Shobe KK, Kihlstrom JF. False memories in women with self-reported childhood sexual abuse: An empirical study. Psychological Science. 2000;11:333–337. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere, J. (2000). Cognitive distortion scales (CDS) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Bruckl TM, Wittchen HU, Höfler M, Pfister H, Schneider S, Lieb R. Childhood separation anxiety and the risk of subsequent psychopathology: Results from a community study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2006;76:47–56. doi: 10.1159/000096364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen, C. C., Palesh, O. G., & Aggarwal, R. (2005). Sexual revictimization a review of the empirical literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse Volume, 6, 103 – 29. 10.1177/1524838005275087. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Coban AE, Karaman NG. Interpersonal cognitive distortions, the level of anxiety and hopelessness of university students. Journal of Cognitive Behavioral Psychotherapy and Research. 2013;2:78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cougle JR, Timpano KR, Sachs-Ericsson N, Keough ME, Riccardi CJ. Examining the unique relationships between anxiety disorders and childhood physical and sexual abuse in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication. Psychiatry Research. 2010;177:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir NO, Gorgulu Y. The prevalance of separation anxiety disorder in patients with generalised anxiety disorder who applied to an university hospital outpatient clinic. Turkish Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2020;23:188–195. doi: 10.5505/kpd.2020.16046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dereboy C, Sahin Demirkapı E, Sakiroglu M, Safak Ozturk C. The relationship between childhood traumas, identity development, difficulties in emotion regulation and psychopathology. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry. 2018;29:147–153. doi: 10.5080/u20463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirioz M, Alkin T, Yemez B, Onur E, Eminagaoglu N. The validity and reliability of turkish version of separation anxiety symptoms inventory and adult separation anxiety questionnaire. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;23:108–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erol A, Ersoy B, Mete L. Association of suicide attempts with childhood traumatic experiences in patients with major depression. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;24:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes V, Osório FR. Are there associations between early emotional trauma and anxiety disorders? Evidence from a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry. 2015;30:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Chelminski I, Zimmerman M. Childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and diagnoses of depressive and anxiety disorders in adult psychiatric outpatients. Depression & Anxiety. 2007;24:256–263. doi: 10.1002/da.20238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J, Chan RC. Early maladaptive schemas as mediators between childhood maltreatment and later psychological distress among chinese college students. Psychiatry Research. 2018;259:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gul A, Gul H, Ozen NE, Battal S. The relationship between anxiety, depression, and dissociative symptoms on the basis of childhood traumas. Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2016;6:107–115. doi: 10.5455/jmood.20160718070002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gulcu Ok, N. E. (2017). Attachment Styles, Temperament, Childhood Traumas and Early Life Events in Panic Disorder Comorbid with Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder. Thesis. Baskent University Faculty of Medicine.

- Herman, J. L. (2011). Trauma and Recovery In Tosun T (Ed.), Literatür Yayincilik.

- Hovens JGFM, Wiersma JE, Giltay EJ, Van Oppen P, Spinhoven P, Penninx BWJH, Zitman FG. Childhood life events and childhood trauma in adult patients with depressive, anxiety and comorbid disorders vs. controls. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010;122:66–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroglu, E. (2014). Clinical Psychiatry. Hekimler Yayin Birligi.

- Mandelli L, Petrelli C, Serretti A. The role of specific early trauma in adult depression: A meta-analysis of published literature. Childhood trauma and adult depression. European Psychiatry. 2015;30:665–680. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manicavasagar V, Silove D, Marnane C, Wagner R. Adult attachment styles in panic disorder with and without comorbid adult separation anxiety disorder. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;43:167–172. doi: 10.1080/00048670802607139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertol S, Alkin T. Temperament and character dimensions of patients with adult separation anxiety disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;139:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namli Z, Ozbay A, Tamam L. Adult separation anxiety disorder: A review. Current Approaches in Psychiatry. 2022;14:46–56. doi: 10.18863/pgy.940071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olmez SB, Sarigedik E, Ataoglu A. The relationships between separation anxiety disorder, childhood traumas, and anxiety sensitivity in a sample of medical students. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports. 2022;9:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2022.100367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orsel S, Karadag H, Kahilogullari K, Aktas A. The frequency of childhood trauma and relationship with psychopathology in psychiatric patients. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;12:130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrek C, Elbert T, Weierstall R, Müller O, Rockstroh B. Childhood adversities in relation to psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2013;206:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possel P, Thomas SD. Cognitive triad as mediator in the hopelessness model? A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Psycholog. 2011;67:224–240. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing ındirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ready CB, Hayes AM, Yasinski CW. Overgeneralized beliefs, accommodation, and treatment outcome in youth receiving trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for childhood trauma. Behavior Therapy. 2015;46:617–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei M, Ghazanfari F. The role of childhood trauma, early maladaptive schemas, emotional schemas and experimental avoidance on depression: A structural equation modeling. Psychiatry Research. 2016;246:407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sar V, Ozturk PE, İkikardes E. Validity and reliability of the turkish version of childhood trauma questionnaire. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences. 2012;32:1054–1063. doi: 10.5336/medsci.2011-26947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer A, Ayers S. Post-traumatic growth in women after childbirth. Psychology & Health. 2009;24:457–471. doi: 10.1080/08870440701864520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaini S, Ogliari A, Eley TC, Zavos HMS, Battaglia M. Genetic and environment contributions to separation anxiety: A meta-analytic approach to twin data. Depression & Anxiety. 2012;29:754–761. doi: 10.1002/da.21941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman LD, Wyulek L. Correlates of separation anxiety symptoms among first-semester college students: An exploratory study. The Journal of Psychology. 2007;141:135–145. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.141.2.135-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare-Finch J, Allysa JB. Behavioural changes add validity to the construct of posttraumatic growth. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25:433–439. doi: 10.1002/jts.21730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear K, Jin R, Ruscio AM, Walters EE, Kessler RC. Prevalence and correlates of estimated DSM-IV child and adult separation anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1074–1083. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelby, J. (2010). Cognitive-behavioral therapy and play therapy for childhood trauma and loss. In N. B. Webb (Ed.), Helping bereaved children: A handbook for practitioners (pp. 263–277). The Guilford Press.

- Silove, D., Alonso, J., Bromet, E., Gruber, M., Sampson, N., Scott, K., & Kessler, R. C. (2015). Pediatric-onset and adult-onset separation anxiety disorder across countries in the world mental health survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 2015; 172:647–656. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14091185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tay AK, Rees S, Kareth M, Silove D. Associations of adult separation anxiety disorder with conflict-related trauma, ongoing adversity, and the psychosocial disruptions of mass conflict among West papuan refugees. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86:224–235. doi: 10.1037/ort0000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkcapar H. Bilişsel Terapi. Ankara: Hekimler Yayın Birliği Yayıncılık; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF, Berman SL, Silverman WK, Saavedra LM. Cognitive errors in youth with anxiety disorders: The linkages between negative cognitive errors and anxious symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:559–575. doi: 10.1023/A:1005505531527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]