Abstract

Recent research has highlighted the alarmingly high rates at which sexual and gender diverse (SGD) individuals experience Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE). ACE, in turn, are strongly related to mental illness—an important correlate of substance use. The present study explores whether mental illness moderates the relationship between ACE and substance use outcomes among SGD adults. As part of a larger community-based participatory research study, we assessed ACE, self-reported mental illness, and past-year substance use and misuse among a large and diverse sample of SGD community members in South Central Texas (n = 1,282). Multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess relationships between ACE, mental illness, substance use, and substance misuse (DAST > 3). Interaction terms between ACE and history of mental illness were created to assess moderation effects. Cumulative ACE scores were associated with a significantly higher odds of self-reported past year substance use (AOR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.34–1.54) and substance misuse (AOR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.11–1.32). History of mental illness was associated with an increased odds of self-reported substance misuse (AOR = 2.07, 95% CI = 1.20–3.55), but not past year substance use. There was a significant interaction of ACE and history of mental illness on the odds of past year substance use (AOR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.69–0.89), but not for substance misuse. These results provide support for theoretical models linking ACE, mental illness, and substance use among SGD adults. Longitudinal research designs are needed to address temporality of outcomes and test mediation models of trauma, mental illness, and substance use. Future directions for prevention and intervention are discussed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40653-023-00560-y.

Keywords: ACE, Anxiety, Depression, PTSD, Substance use, LGBTQ+

Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) are commonly described as a highly correlated and cumulative set of traumatic experiences including abuse (psychological/verbal, physical, and sexual), neglect (emotional and physical), and indicators of household dysfunction including parental intimate partner violence, household member substance misuse and mental illness, and household member incarceration (Felitti et al., 1998). Those exposed to ACE report more alcohol use (Anda et al., 2006; Dube et al., 2002; Strine et al., 2012), tobacco use (Felitti et al., 1998; Grigsby et al., 2021), and other substance use (Dube et al., 2003; Felitti et al., 1998; Forster et al., 2019) relative to non-exposed peers. The life-course relationship between childhood adversity, substance use behavior and addiction are well documented in the general population. This sequela starts with increased ACE exposure, increased frequency and quantity of substance use, followed by heightened risk for substance use disorder over the lifespan (Afifi et al., 2008; Anda et al., 2006; Dube et al., 2002, 2003). In general population studies, ACE exposure has also been associated with a number of mental health outcomes, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Afifi et al., 2008; Schalinski et al., 2016), anxiety and depression (Afifi et al., 2008; Felitti et al., 1998; Schalinski et al., 2016), as well as suicidality (Afifi et al., 2008; Brodsky & Stanley, 2008; Felitti et al., 1998).

Felitti (2009) hypothesized that experiences of childhood trauma and adversity are associated with poor mental health status in adulthood, and that increases in substance use may, in part, be explained by these resulting mental health problems. According to the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (TMSC), a framework for understanding ways of coping with stressful situations, stressful experiences are seen as person–environment transactions, and the way in which individuals appraise stressors directly contributes to their method of coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Individual control over stressors is a key component of this model, where lower control is associated with worse coping strategies. Hence, we postulate that since children have little control over their family environment (ACE exposure), this exposure would foster maladaptive coping (substance misuse) especially among those experiencing previous or ongoing health issues (mental illness).

Sexual and gender diverse (SGD) individuals reflect a range of sexual and gender minority identities as described by the colloquial LGBTQIA acronym (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual/aromantic/agender), and represent a notable high-risk population for trauma, mental health, and addiction research. In one of the earliest studies (Blosnich & Andersen, 2015) ACE was identified as a central driving factor for mental health disparities observed in lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults relative to heterosexual peers. A further population-based study (Austin et al., 2016) of ACE in sexual minority adults (i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual) using data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System identified that sexual minority adults had between a 1.4 to 3.1 increase in the odds of reporting specific ACE compared to heterosexual respondents. Additionally, people identifying as transgender or gender diverse have been shown to report specific ACE events, such as emotional abuse and neglect, more frequently than cisgender sexual minority individuals (Schnarrs et al., 2019) prompting the need for more research on ACE experiences and related outcomes in SGD populations.

Substance use and addiction researchers have repeatedly called for research to identify root causes of existing disparities affecting SGD individuals (Mereish, 2019; Watson et al., 2018). Population studies have shown that SGD individuals have higher rates of smoking and drinking compared to cisgender individuals (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013; Matthews & Lee, 2014). A recent review (Connolly & Gilchrist, 2020) of substance use among transgender adults provided evidence of higher prevalence of use across substances, that trans women are particularly at risk for substance use and related problems, and that much of the existing research supports minority stress theories. Similar research suggests that sexual minority individuals are more likely than others to consume illicit substances (King et al., 2008; Newcomb et al., 2014) without adjusting for ACE or mental illness.

A limited number of studies have investigated the relationships between ACE, mental health, and substance use among SGD populations. After demonstrating a significant difference in exposure to ACE based on sexuality, one study found no significant difference in binge drinking or physical health after statistically correcting for ACE (Austin et al., 2016). In the same study, the authors reported no significant differences in binge drinking or smoking based on sexual minority status, and noted that disparities in mental illness were attenuated, but not eliminated, after adjusting for ACE. Another study (McCabe et al., 2020) using data from the 2012 − 2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (a cross-sectional, nationally representative survey of non-institutionalized US adults) reported higher rates of comorbid substance use and mental health disorders among sexual minority adults with a history of ACE. In particular, the authors noted a curvilinear relationship between ACE and comorbid substance use and mental health disorders, and sexual minorities consistently had a higher ACE mean than concordant heterosexual respondents. Finally, a recent cross-sectional study comparing SGD and non-SGD college students (Grigsby et al., 2021) concluded that increased ACE exposure was a significant predictor of current cigarette use for SGD students and highlighted the importance of mental health mechanisms underlying their observed relationships. Identifying patterns of traumatic experiences, mental health, and substance use is a necessary next step in developing targeted prevention and intervention programs for the SGD community.

To our knowledge, no existing research study has investigated the ACE, mental health, and substance use hypothesis proposed by Felliti (2009) that is inclusive of the broader SGD community. The present study sought to fill this gap in the literature. The use of a moderation framework will aid the field in understanding how harmful health behaviors, such as problematic substance use, observed in ACE exposed SGD adults might vary between those with and without a history of mental illness. Following Felliti (2009) we hypothesized that higher ACE scores would be positively associated with self-reporting past year substance use and substance misuse. Moreover, we hypothesized that the relationship of ACE on self-reported substance use and misuse would be significantly greater among participants reporting a history of mental illness compared to those who did not.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Data come from phase three of a larger community health project called Strengthening Colors of Pride focused on understanding resilience and health in SGD adults living in South Texas. This study was designed using the principles of community based participatory research and included a community advisory board (CAB). CAB members participated as full collaborators on the project and were instrumental in the decision-making processes related to every aspect of this project.

We employed a multifaceted recruitment strategy. First, recruitment emails were distributed to existing study participants from Phase 1 of the project to individuals on the Pride Center San Antonio and other partner organizations’ email list servers, and to individuals whose email address were collected during the Annual San Antonio Pride Celebration in 2019. Second, we posted recruitment messages on social media, LGBTQ + websites, and organizational partners’ websites. Finally, palm cards were distributed during community events during the summer of 2019. All recruitment materials included a brief overview of the study, inclusion and exclusion criteria, information about survey length and incentives, and a link to the online survey. Potential respondents who clicked on the survey link were taken to the study information page where they provided consent prior to beginning the survey. Participants were first screened for inclusion. To participate in the parent study, respondents had to be at least 16-years-old, identify with a SGD category (e.g., LGBTQ+), and reside in the study catchment area. The online survey was a broad community health assessment that took approximately 30-minutes to complete. Participants who completed the survey were sent a $10 electronic Amazon gift card for their time. All study procedures were approved by the Trinity University Institutional Review Board. Data for the present analysis was restricted to those ages 18 to 64 (n = 1,282) who were no longer in high school as we were interested in adult health outcomes of ACE exposed SGD individuals.

Measures

Adverse Childhood Experiences. Ten ACE items were taken directly from the Kaiser ACE study questionnaire and used to retrospectively assess whether the respondent had experienced various forms of childhood trauma (Dube et al., 2003; Felitti et al., 1998). Items assessed exposure to abuse (verbal, physical, sexual), neglect (emotional, physical), and household dysfunction (domestic violence, parental divorce, household member incarceration, household member substance use and mental illness). A 5-point Likert scale was used, with response options ranging from 0=“never” to 4=“always”. Any response other than “never” was coded one to create a cumulative ACE variable for analysis (range: 0–10) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for complete case data and using multiple imputation by chained equation (n = 1,282)

| Complete case data | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 31.64 | 9.82 |

| f | % | |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Bisexual/Pansexual | 426 | 33.23 |

| Gay/Lesbian/Same Gender Loving | 676 | 52.73 |

| Heteronormative/Asexual/Other | 36 | 2.81 |

| Heterosexual | 60 | 4.68 |

| Queer | 84 | 6.55 |

| Gender identity | ||

| Agender/Non-binary/Non-Gender Conforming/Other | 157 | 12.25 |

| Cisgender | 1,061 | 82.76 |

| Transgender | 64 | 4.99 |

| Race | ||

| African-American | 154 | 12.01 |

| Asian/South Asian | 54 | 4.21 |

| Latino/a/x | 475 | 37.05 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 583 | 45.48 |

| Other | 16 | 1.25 |

| Imputed data | Proportion | 95% CI |

| History of mental illness | ||

| No | 0.538 | 0.506-0.569 |

| Yes | 0.462 | 0.430-0.494 |

| Past year drug use | ||

| No | 0.690 | 0.659-0.720 |

| Yes | 0.310 | 0.279-0.340 |

| Substance use problem (DAST > 3) | ||

| No | 0.805 | 0.774-0.836 |

| Yes | 0.195 | 0.164-0.226 |

| Annual income | ||

| Less than $10,000 | 0.166 | 0.144-0.187 |

| $10,000-$19,999 | 0.101 | 0.085-0.119 |

| $20,000–29,999 | 0.187 | 0.166-0.209 |

| $30,000-$39,999 | 0.212 | 0.189-0.234 |

| $40,000-$49,999 | 0.121 | 0.103-0.139 |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 0.127 | 0.108-0.145 |

| $75,000-$100,000 | 0.042 | 0.032-0.054 |

| More than $100,000 | 0.041 | 0.030-0.052 |

| Education | ||

| Some high school | 0.008 | 0.003-0.013 |

| Currently attending high school | 0.010 | 0.004-0.016 |

| High school diploma or GED | 0.161 | 0.140-0.182 |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 0.333 | 0.307-0.359 |

| Four-year college degree | 0.337 | 0.311-0.364 |

| Master’s degree | 0.122 | 0.104-0.140 |

| Doctorate | 0.027 | 0.019-0.037 |

| Free lunch status | ||

| No | 0.644 | 0.617-0.671 |

| Yes | 0.356 | 0.329-0.383 |

| Total ACE | ||

| Mean | 3.81 | 3.62–4.01 |

Note: M = mean, SD = standard deviation, f = frequency, %=percent, SE = standard error, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, DAST = Drug Abuse Screening Test

History of mental illness

Participants endorsed whether they had ever experienced or been diagnosed with anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These three binary yes/no variables were used to generate a history of mental illness variable (0 = none, 1 = yes to any) akin to previous research (Hayes et al., 2022). Single-item measures of global mental health status perform well in comparison to larger scales (Ahmad et al., 2014) and clinical assessment (Maske et al., 2017) and were used in the present study due to space limitations on the community health survey.

Self-reported substance use and substance misuse

Participants were asked about the last time they used various substances including alcohol, benzodiazepines, cannabis, cocaine/crack cocaine, hallucinogens, heroin, methamphetamine, prescription opioids, synthetic party drugs, or “other drugs.” Responses of “never” or “more than a year ago” were coded 0 and responses of “during the past 30 days,” “more than 1 month ago, but less than 3 months ago,” “more than 3 months ago, but less than 6 months ago,” and “more than 6 months ago, but less than 1 year ago” were coded 1 for analysis. The second outcome variable, self-reported substance misuse, was assessed using the 10-item Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) and coded one if participants exceeded the cutoff score of 3 and coded 0 otherwise (Yudko et al., 2007).

Covariates

Covariates were selected to reflect the sexual and gender diversity of the sample as well as important social determinants of health related to exposure and experiences of the primary predictor (ACE), moderator (history of mental illness) and outcomes (substance use and misuse) (Henderson et al., 2022). A three-part question allowed participants to identify their gender, as suggested by the Williams Institute (Williams Institute, 2014). First, participants were asked their sex assigned at birth, on their original birth certificate. Next, we asked participants if they identified as transgender, gender non-conforming, or whether their gender now was different from their sex assigned at birth. Third, participants were asked their gender identity. Options for the third question included male, female, transgender, gender non-conforming, agender, non-binary, gender non-conforming, and none of the above. For analysis, gender identity was coded as 0 = cisgender [reference], 1 = transgender, and 2 = agender, non-gender conforming, non-binary, and other. Sexual orientation was assessed with a single item and coded as 0 = gay, lesbian, or same gender loving [reference], 1 = bisexual or pansexual, 2 = queer, 3 = heterosexual, and 4 = asexual, heteroflexible, and other.

To measure race and ethnicity, participants endorsed whether they were “American Indian/Alaska Native”, “Asian”, “South Asian”, “Black/African American”, “Latinx/Latino/Latina/Hispanic”, and “Non-Hispanic White” [reference]. Additionally, due to sparsity, Asian and South Asian identities were combined to one variable. Education level was assessed as the highest level of education completed by participants (ranging from some high school to Doctorate degree). Participants were asked to endorse their income during the last year (less than $10,000; $10,000-$19,999; $20,000-$29,999; $30,000-$39,999 [reference]; $40,000-$49,999; $50,000-$74,999; $75,000-$100,000; more than $100,000). We also assessed whether participants received free lunch at school as a child or teenager (0 = no [reference], 1 = yes).

Analysis Plan

First, data were summarized and missing data was assessed. Missing data was handled using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) since it does not assume a multivariate normal distribution and can be readily used to impute categorical or count variables (White et al., 2011). Visual inspection of missingness patterns and results of Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test supported the assumption data were missing at random (MAR). MICE was used for variables with missingness over 10%. Performance of the multiple imputation process was explored and assessed using relative variance increase (RVI) and fraction of missing information (FMI). The largest observed FMI was used to suggest the adequate number of imputations according to the rule of thumb, i.e., FMI x100. For the present data, the largest FMI was 0.43 and 43 imputations were used, respectively.

Next, multivariate logistic regression models were used with the ‘mi estimate’ command in Stata version 16 (Stata Corp., 2019) to assess the relationship between ACE and (i) past year substance use, and (ii) substance misuse (DAST > 3). To evaluate whether associations varied between participants with and without a history of mental illness we included interaction terms (ACE*history of mental illness) in a second set of models. Results from complete case and multiply imputed data were compared to evaluate changes in statistical conclusion validity (Grigsby & McLawhorn, 2019). Findings are presented as adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). To visualize statistically significant interaction terms, plots of marginal effects were generated using the ‘mimrgns’ and ‘marginspots’ commands.

Results

The average age of the sample was 31.64 years (SD = 9.82), and the majority of the sample identified as non-Hispanic White (45.48%) followed by Latino/a/x (37.05%), African American (12.01%), Asian or South Asian (4.21%), and other (1.25%). The most commonly reported sexual identity was gay/lesbian/same gender loving (52.73%) and the most commonly reported gender identity was cisgender (82.76%). Participants reported, on average, 3.81 ACE (95% CI = 3.62–4.01). Approximately 46.2% of the sample reported history of a mental health problem, 31% reported past year substance use and 20.5% reported substance misuse.

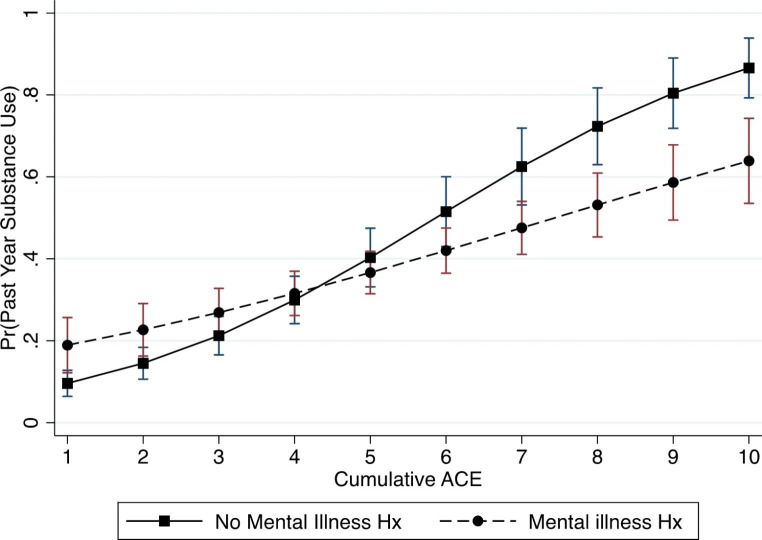

Controlling for covariates, the odds of reporting past year substance use increased 1.43 times (95% CI = 1.34–1.54) for every additional ACE reported while a history of mental illness was not associated with past year substance use (Table 2a). The interaction between ACE and history of mental illness was statistically significant (p < 0.05). As shown in Fig. 1, the probability of reporting past year substance use significantly differs between participants with and without history of mental illness as cumulative ACE increases. As seen in Table 2b, predicting self-reported substance misuse (DAST > 3), the odds were significantly higher for those reporting a history of mental illness (AOR = 2.07, 95% CI = 1.20–3.55), and increased with every additional ACE reported (AOR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.11–1.32) in the main effects model. However, the interaction between ACE and history of mental illness was not significant (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression models predicting (a) past year substance use and (b) substance misuse (DAST > 3) using multiple imputation by chained equation (n = 1,282)

| (a) Past year substance use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects | Moderation model | |||

| Predictor | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI |

| Cumulative ACE | 1.43 | 1.34–1.54 | 1.61 | 1.47–1.77 |

| Mental illness | 0.89 | 0.60–1.33 | 2.87 | 1.46–5.60 |

| ACE*mental illness | 0.78 | 0.69–0.89 | ||

| (b) Substance misuse (DAST > 3) | ||||

| Main effects | Moderation model | |||

| Predictor | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI |

| Cumulative ACE | 1.21 | 1.11, 1.32 | 1.21 | 1.08–1.36 |

| Mental illness | 2.07 | 1.20, 3.55 | 2.14 | 0.81–4.86 |

| ACE*mental illness | 0.99 | 0.85–1.16 | ||

Note: Significant results in bold. ACE = adverse childhood experiences; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval. All models adjust for race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, annual income, education level, and free lunch status as a child. Past year substance use included as a covariate for model predicting substance misuse

Fig. 1.

Predicted probability of past year substance use comparing participants with no history of mental illness (square markers) and those with a history of mental illness (circle markers) across cumulative adverse childhood experiences

Discussion

The findings of the main effects analysis supported our hypothesis. Specifically, the odds of past year substance use and misuse increased as participants reported more ACE. These results contribute to a growing literature that has evidenced associations between ACE and substance use outcomes among sexual and gender diverse individuals (Grigsby et al., 2021; McCabe et al., 2020; Schneeberger et al., 2014). These findings support previous calls to incorporate ACE screening as a routine part of health care and to develop trauma-informed prevention programs and interventions to reduce the disproportionate burden of substance use and substance use disorder in SGD populations (McCabe et al., 2020). In addition, continued research is needed to compare outcomes within the SGD communities given previous work, for example, has revealed that individuals with a bisexual identity report greater experiences of trauma, substance use, and other adverse health outcomes (Batchelder et al., 2021; McCabe et al., 2020).

We observed a significant interaction between ACE and history of mental illness for past year substance use, but not experiencing substance misuse which partially supported our hypothesis. The probability of reporting past year substance use was lower among those reporting a history of mental illness, relative to those with no history of mental illness, as cumulative ACE scores increased. This is contrary to Felliti’s (2009) hypothesis which would suggest an opposite pattern. However, it is possible that individuals with a history of mental health problems would abstain from alcohol and other drug use. Other factors that were not assessed in the present study—such as perceiving alcohol and drugs as high risk or personally disapproving of substance use (King et al., 2019) may be stronger among those with a history of childhood trauma and mental illness which could explain this finding. We also did not observe a significant interaction between ACE and history of mental illness with reporting substance misuse. Methodological limitations may have contributed to this null result as well. For example, individuals may not self-endorse themselves as experiencing a substance use problem due to perceived fear of consequences or social desirability and this may be especially true among those with a history of mental health problems. Alternatively, Felitti (2009) proposed a mediational relationship between these variables, but due to the cross-sectional nature of this work we were unable to test temporal associations between these variables. It is possible that mental illness may mediate, but not moderate, the relationship between ACE and substance misuse in this population. Future research employing a longitudinal research design and collection of corroborative data (e.g., biological data, peer/family report) is needed to further examine Felliti’s hypothesis using a mediational framework (Felitti, 2009).

This sample of SGD adults reported a high rate of ACE exposure which is consistent with data from national (McCabe et al., 2020) and community-based studies (Dowling et al., 2023) in the U.S. A heightened ACE risk for sexual and gender diverse groups can be explained by adapting the culturally-informed ACE framework, or C-ACE framework (Bernard et al., 2021) which extends the traditional ACE framework to understand the role of ACE exposure risk factors—such as sexual and gender minority status—and the role of heterosexism or gender norms as a driver of traumatic experiences in the household. Moreover, there is a robust body of work surrounding the experiences of SGD youth in terms of difficult family interactions (Puckett et al., 2015) as well as stressful events occurring at schools (Basile et al., 2020) and in the broader community (Hatzenbuehler & McLaughlin, 2014), that are driven by heterosexism and heteronormativity. While creating safe and affirming environments for SGD youth to reduce exposure to stigma and discrimination have been explored (Black et al., 2012) considerably less attention has been given to developing interventions addressing the impact ACE has on adult SGD health with an emphasis on mental health and substance use disorder prevention such as developing trauma-informed screening and intervention protocols for use in primary care settings, college campuses, and workplaces. According to the TMSC framework, social support (i.e., the help individuals receive from members of their social network) can have “stress-buffering” effects on health behaviors and should be explored as an intervention target to disrupt the associations observed here. More work is needed to understand how ACE experiences differ for SGD youth and whether such differences account for some of the noted health disparities within this population and in comparison to cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Though not assessed directly in the present study, specific states and traits that are characteristic of mental illness may partly explain the moderated relationship observed here. For example, the link between insecure attachment and substance use disorder is well established in the literature (Schindler, 2019). To move the field forward, it is also important to recognize the role of multiple stressors that impact insecure attachment for SGD populations. In fact, Keating and Muller (2020) found that experiences of SGD-related discrimination were related to attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, and emotional dysregulation. Future research should begin to probe the relationship between exposure to family-based childhood adversity, minority stress (i.e., community-based adversity), and mental health/psychological functioning using the C-ACE framework to explore the role of independent and joint ACE-health relationships experienced by this population. Moreover, greater attention to the manifestation of mental illness, in terms of severity and duration, may also uncover important mechanisms linking trauma, mental health, and externalizing problems (e.g., substance use) that would be crucial for developing effective screening and intervention programs.

Strengths and Limitations

There are several important limitations to consider in the interpretation of the study findings. These analyses were based on cross-sectional data, and cause-effect conclusions cannot be made. Specifically, the temporal ordering of ACE, mental illness, substance use, and substance use problems would be more readily established with a longitudinal data collection design. Second, although we used a multipronged recruitment strategy to recruit members of a historically hard to reach population, the final analytic sample is not representative of the broader SGD population. Third, MICE was selected to handle missing continuous and categorical variables due to its flexibility, but the approach is not theoretically justified like other imputation approaches (Azur et al., 2011). However, the use of this technique did not impact our statistical conclusion validity. Fourth, rather than asking about the last time participants used a substance, a timeline follow-back data collection protocol would have been preferred. Fifth, our assessment of ACE was not exhaustive and did not include extra-familial ACE such as poverty, community violence, and bullying victimization. Lastly, the single-item measures of anxiety, depression, and PTSD does not allow for the proper assessment of other mental health issues producing similar symptoms nor does it capture all aspects of these disorders. Furthermore, the use of these items does not allow us to draw conclusions about the role of severity or point to specific symptomology associated with substance use behavior following traumatic experiences, such as ACE. These limitations are inherent in the community-based participatory research design used to collect these data.

There are also noteworthy strengths to the present study. First, we recruited a large sample of sexual and gender diverse adults who have been historically underrepresented in the scientific literature despite being identified as a priority population in epidemiological research. Second, the CBPR approach used to collect data establishes a unique cohort that can be enrolled into future longitudinal studies.

Conclusions

Potentially traumatic experiences early in the life course may be especially important in explaining why rates of substance use and disorder are prevalent and persistent issues across SGD communities as indicated by previous research (Rojas et al., 2019; Schuler et al., 2020). Our findings indicated roughly one in four participants self-reported they had a substance use problem as an adult, and we observed a relationship between ACE exposure, mental health, and substance use problems. As health researchers begin to extend research on the long-term impacts of ACE in SGD populations, more evidence is needed to disentangle the complex interplay of ACE, minority stress, and mental health on the biopsychosocial processes that influence an array of health behaviors, including substance use.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Support for this research was provided by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Interdisciplinary Research Leaders program. Interdisciplinary Research Leaders is a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation led by the University of Minnesota. Dr. Claborn is supported in part by a grant from National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; K23DA039037; PI: Claborn). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA or the National Institutes of Health.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Afifi TO, Enns MW, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJG, Stein MB, Sareen J. Population attributable fractions of Psychiatric Disorders and suicide ideation and attempts Associated with adverse childhood experiences. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(5):946–952. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad F, Jhajj AK, Stewart DE, Burghardt M, Bierman AS. Single item measures of self-rated mental health: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14(1):398. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Dube SR, Giles WH. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;256(3):174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A, Herrick H, Proescholdbell S. Adverse childhood experiences related to poor Adult Health among Lesbian, Gay, and bisexual individuals. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106(2):314–320. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azur MJ, Stuart EA, Frangakis C, Leaf PJ. Multiple imputation by chained equations: What is it and how does it work? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2011;20(1):40–49. doi: 10.1002/mpr.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Clayton HB, DeGue S, Gilford JW, Vagi KJ, Suarez NA, Zwald ML, Lowry R. Interpersonal violence victimization among High School Students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements. 2020;69(1):28–37. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelder AW, Fitch C, Feinstein BA, Thiim A, O’Clerigh C. Psychiatric, Substance Use, and structural disparities between gay and bisexual men with histories of childhood sexual abuse and recent sexual risk behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2021;50:2861–2873. doi: 10.1007/s10508-021-02037-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard DL, Calhoun CD, Banks DE, Halliday CA, Hughes-Halbert C, Danielson CK. Making the “C-ACE” for a culturally-informed adverse childhood Experiences Framework to Understand the Pervasive Mental Health Impact of Racism on Black Youth. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. 2021;14(2):233–247. doi: 10.1007/s40653-020-00319-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, A., Harel, O., Matthews, G., Mehl, M., & Tamlin, S. (2012). Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (1st ed.). Guilford Press.

- Blosnich JR, Andersen JP. Thursday’s child: The role of adverse childhood experiences in explaining mental health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual US adults. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2015;50(2):335–338. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0955-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky BS, Stanley B. Adverse childhood experiences and suicidal behavior. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2008;31(2):223–235. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly D, Gilchrist G. Prevalence and correlates of substance use among transgender adults: A systematic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2020;111:106544. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling BA, Grigsby TJ, Ziomek GJ, Schnarrs PW. Substance use outcomes for sexual and gender minority adults with a history of adverse childhood experiences: A scoping review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports. 2023;6:100129. doi: 10.1016/j.dadr.2022.100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB. Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27(5):713–725. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF. Childhood abuse, neglect, and Household Dysfunction and the risk of Illicit Drug Use: The adverse childhood Experiences Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):564–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ. Adverse childhood Experiences and Adult Health. Academic Pediatrics. 2009;9(3):131–132. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and Household Dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster M, Rogers CJ, Benjamin S, Grigsby TJ, Lust K, Eisenberg ME. Adverse childhood experiences, ethnicity, and Substance Use among College students: Findings from a two-state sample. Substance Use & Misuse. 2019;54(19):2368–2379. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2019.1650772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, Muraco A, Hoy-Ellis CP. Health Disparities among Lesbian, Gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a Population-Based study. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(10):1802–1809. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigsby TJ, McLawhorn J. Missing Data Techniques and the statistical conclusion validity of Survey-Based alcohol and drug Use Research Studies: A review and comment on reproducibility. Journal of Drug Issues. 2019;49(1):44–56. doi: 10.1177/0022042618795878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grigsby, T. J., Schnarrs, P. W., Lunn, M. R., Lust, K., & Forster, M. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences and past 30-Day cigarette and E-Cigarette use among sexual and gender minority College Students. LGBT Health, 8(6), 10.1089/lgbt.2020.0456. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA. Structural Stigma and Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenocortical Axis Reactivity in Lesbian, Gay, and bisexual young adults | Annals of behavioral Medicine | Oxford Academic. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;47(1):39–47. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9556-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S, Carlyle M, Haslam SA, Haslam C, Dingle G. Exploring links between social identity, emotion regulation, and loneliness in those with and without a history of mental illness. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2022;61(3):701–734. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson ER, Goldbach JT, Blosnich JR. Social determinants of sexual and gender minority Mental Health. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry. 2022;9(3):229–245. doi: 10.1007/s40501-022-00269-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keating L, Muller RT. LGBTQ + based discrimination is associated with ptsd symptoms, dissociation, emotion dysregulation, and attachment insecurity among LGBTQ + adults who have experienced trauma. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2020;21(1):124–141. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2019.1675222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, Nazareth I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. Bmc Psychiatry. 2008;8(1):70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SM, McGee J, Winters KC, DuPont RL. Correlates of substance use abstinence and non-abstinence among High School seniors: Results from the 2014 Monitoring the Future Survey. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2019;28(2):105–112. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2019.1608343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Maske UE, Hapke U, Riedel-Heller SG, Busch MA, Kessler RC. Respondents’ report of a clinician-diagnosed depression in health surveys: Comparison with DSM-IV mental disorders in the general adult population in Germany. Bmc Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1203-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DD, Lee JGL. A Profile of North Carolina Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Health Disparities, 2011. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(6):e98–e105. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Hughes TL, West BT, Evans-Polce RJ, Veliz PT, McCabe VV, Boyd CJ. Sexual orientation, adverse childhood experiences, and Comorbid DSM-5 Substance Use and Mental Health Disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2020;81(6):20m13291. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereish EH. Substance use and misuse among sexual and gender minority youth. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2019;30:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, Greene GJ, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. Prevalence and patterns of smoking, alcohol use, and illicit drug use in young men who have sex with men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;141:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett JA, Woodward EN, Mereish EH, Pantalone DW. Parental rejection following sexual Orientation Disclosure: Impact on internalized Homophobia, Social Support, and Mental Health. LGBT Health. 2015;2(3):265–269. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas JI, Leckie R, Hawks EM, Holster J, del Carmen Trapp M, Ostermeyer BK. Compounded stigma in LGBTQ + people: A Framework for understanding the Relationship between Substance Use Disorders, Mental Illness, Trauma, and sexual minority status. Psychiatric Annals. 2019;49(10):446–452. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20190912-01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schalinski I, Teicher MH, Nischk D, Hinderer E, Müller O, Rockstroh B. Type and timing of adverse childhood experiences differentially affect severity of PTSD, dissociative and depressive symptoms in adult inpatients. Bmc Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):295. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler A. Attachment and Substance Use Disorders—Theoretical models, empirical evidence, and implications for treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019;10:e727. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnarrs PW, Stone AL, Salcido R, Baldwin A, Georgiou C, Nemeroff CB. Differences in adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and quality of physical and mental health between transgender and cisgender sexual minorities. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2019;119:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeberger AR, Dietl MF, Muenzenmaier KH, Huber CG, Lang UE. Stressful childhood experiences and health outcomes in sexual minority populations: A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2014;49(9):1427–1445. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0854-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS, Prince DM, Breslau J, Collins Substance Use Disparities at the intersection of sexual identity and Race/Ethnicity: Results from the 2015–2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. LGBT Health. 2020;7(6):283–291. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strine TW, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Prehn AW, Rasmussen S, Wagenfield M, Dhingra S, Croft JB. Associations between adverse childhood experiences, psychological distress, and adult alcohol problems. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2012;36(3):408–423. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.3.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson RJ, Goodenow C, Porta C, Jones A, Saewyc E. Full article: Substance Use among sexual minorities: Has it actually gotten better? Substance Use & Misuse. 2018;53(7):1221–1228. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1400563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine. 2011;30(4):377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams Institute (2014). Home. Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/.

- Yudko E, Lozhkina O, Fouts A. A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the drug abuse screening test. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32(2):189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.