Abstract

The Staphylococcus aureus cap5P and cap5O genes of the type 5 capsule biosynthetic locus restore enterobacterial common-antigen expression to Escherichia coli mutants defective in rffE and rffD gene expression, respectively. Cap5P and Cap5O likely function as UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase and UDP-ManNAc dehydrogenase enzymes, respectively, in the synthesis of the capsule precursor UDP-ManNAcA.

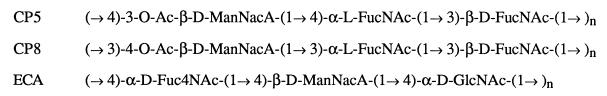

Clinically relevant Staphylococcus aureus serotype 5 and 8 strains produce polysaccharide capsules comprised of N-acetylmannosaminuronic acid (ManNAcA) and 2-acetamido-2,6-dideoxygalactose (FucNAc) (2, 9). However, the type 5 (CP5) and type 8 (CP8) polysaccharides differ in the position of O-acetyl groups and the linkages between the aminosugars (Fig. 1). Recently, the genetic regions involved in CP5 and CP8 synthesis have been cloned and sequenced (6, 13, 14). The cap5 and cap8 gene regions each consist of 16 open reading frames, designated capA through capP (13). The two loci share nearly identical flanking sequences (capA through capG and capL through capP) but differ in the central serotype-specific gene region (capH through capK).

FIG. 1.

Structural comparison of S. aureus CP5 and CP8 polysaccharides and E. coli ECA. O-Ac, O-acetyl; Fuc4NAc, 4-acetamido-4,6-dideoxygalactose.

The S. aureus cap5G and cap5P genes code for putative proteins of 374 and 391 amino acids, respectively (13). Both sequences demonstrate homology to the Escherichia coli rffE gene product (1, 7). The rffE gene encodes UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase, an enzyme which catalyzes the conversion of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) to UDP-N-acetylmannosamine (UDP-ManNAc) during biosynthesis of enterobacterial common antigen (ECA) in E. coli (8). The purified protein encoded by the E. coli rffE gene also demonstrates UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase activity in vitro (12). Additionally, Cap5G and Cap5P share sequence similarity to the UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerases Cps19fK, which is involved in Streptococcus pneumoniae type 19F capsule biosynthesis (10), and RfbC, which is involved in O:54 polysaccharide biosynthesis in Salmonella enterica serovar Borreze (5). As determined by sequence alignments created with the Bestfit program (Wisconsin Package Version 8.0; Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.) by using the default settings Cap5P shows greater homology to the 389-amino-acid RffE protein of E. coli (50% identity and 68% similarity across 368 amino acids) than does Cap5G (30% identity and 50% similarity across 365 amino acids).

The S. aureus cap5O gene codes for a putative protein of 420 amino acids (13). Cap5O shows sequence homology to the E. coli rffD gene product, which is required for ECA biosynthesis (1, 8). The 420-amino-acid RffD enzyme, UDP-ManNAc dehydrogenase, oxidizes UDP-ManNAc to produce UDP-ManNAcA (8). Cap5O is 45% identical and 68% similar to RffD across 399 amino acid residues. Both protein sequences contain the N-terminal ADP-binding domain characteristic of enzymes, particularly dehydrogenases, requiring NAD+ as a cofactor (16).

UDP-ManNAcA is a biosynthetic precursor of ECA, a surface-associated glycolipid common to members of the Enterobacteriaceae (Fig. 1). In E. coli, UDP-ManNAcA is produced from UDP-GlcNAc in a two-step enzymatic reaction as follows (3, 4, 8, 12):

|

Transposon inactivation of the E. coli rffE and rffD genes has been shown to inhibit the conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-ManNAcA and abolish ECA expression (8). In this study, the S. aureus cap5G, cap5P, and cap5O genes were rated for their abilities to functionally complement mutations in the homologous rffE and rffD genes of E. coli and restore ECA expression.

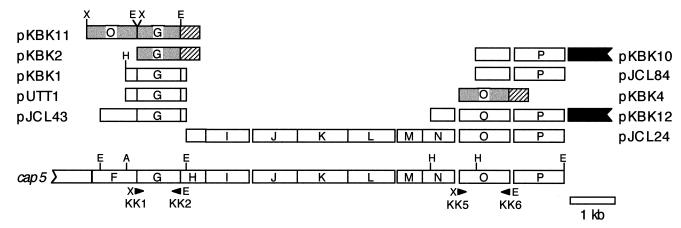

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. PCR amplification of the cap5G gene from plasmid pJCL43 with primers KK1 (5′-ACAATCTAGAGCCAGATACGTATTTCTTGG-3′) and KK2 (5′-ACAAGAATTCCATTTCCTCCAAGTATTTCG-3′), and of cap5O from pJCL24 with primers KK5 (5′-ACAATCTAGACATACAAATCGTTTTATTTGG-3′) and KK6 (5′-ACAAGAATTCTTGTCGATAAAATTAAATATATTGC-3′), was performed with UlTma DNA polymerase from Perkin-Elmer (Foster City, Calif.) for 25 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 45°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 7 min. PCR amplicons were digested with XbaI and EcoRI and were ligated into pUC19 to yield pKBK2 (cap5G) and pKBK4 (cap5O) (Fig. 2). Plasmid pKBK11 (cap5O cap5G) was created by ligating the cap5O PCR amplicon upstream of cap5G in plasmid pKBK2 (Fig. 2). Plasmids pKBK1 (cap5G), pKBK10 (cap5P), and pKBK12 (cap5O cap5P) were created in pUC19 by direct subcloning of restriction fragments from cap5 subclones (Fig. 2).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| AB1133 | K-12 thr-1 leuB6 Δ(gpt-proA)66 hisG4 argE3 thi-1 rfbD1 lacY1 ara-14 galK2 xyl-5 mtl-1 mgl-51 rpsL31 kdgK51 supE44 | 8 |

| 21546 | As AB1133, but rff::Tn10-46 | 8 |

| 21566 | As AB1133, but rff::Tn10-66 | 8 |

| JM109 | F′ traD36 lacIq Δ(lacZ)M15 proA+B+/e14− (McrA−) Δ(lac-proAB) thi gyrA96 (NaIr) endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) relA1 supE44 recA1 | New England Biolabs |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC19 | Cloning vector (Apr) | New England Biolabs |

| pGEM-7Zf+ | Cloning vector (Apr) | Promega |

| pUTT1 | 1.4-kb AccI-EcoRI fragment from pJCL43 (cap5G) in pGEM-7Zf+ | This study |

| pKBK1 | 1.4-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment from pUTT1 (cap5G) in pUC19 | This study |

| pKBK2 | 1.2-kb PCR amplicon from pJCL43 (cap5G) in pUC19 (lacZ′ fusion) | This study |

| pKBK4 | 1.3-kb PCR amplicon from pJCL24 (cap5O) in pUC19 (lacZ′ fusion) | This study |

| pKBK10 | 1.9-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment from pJCL84 (cap5P) in pUC19 | This study |

| pKBK11 | 1.3-kb SphI-EcoRI fragment from pKBK4 (cap5O) in pKBK2 (cap5G-lacZ′ fusion) | This study |

| pKBK12 | 1.3-kb HindIII fragment from pJCL24 (cap5O) in pKBK10 (cap5P) | This study |

| pJCL19 | 34-kb fragment of S. aureus Reynolds DNA (containing the cap5 gene region) in pHC79 | 6 |

| pJCL24 | 9.1-kb EcoRI fragment (cap5I through cap5P) from pJCL19 in pLI50 | 6 |

| pJCL43 | 2.2-kb EcoRI fragment (cap5G) from pJCL19 in pGEM-7Zf+ | This study |

| pJCL84 | 6.2-kb HindIII fragment (cap5P) from pJCL19 in pGEM-7Zf+ | This study |

FIG. 2.

S. aureus cap5 subclones. A portion of the S. aureus cap5 locus is represented, with relevant restriction sites and primer locations indicated. The cap5 subclones listed in Table 1 are aligned above the cap5 locus. S. aureus cap5 coding sequences are represented by open boxes (restriction subcloned) or shaded boxes (PCR subcloned) and labeled with their letter designations (e.g., G for cap5G). Non-cap5 sequences and the lacZ α-peptide coding sequence (lacZ′) from pUC19 are represented by solid and diagonally striped boxes, respectively. Designations of primers used in the PCR amplification of cap5O and cap5G are given below the arrowheads. A, AccI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; X, XbaI.

The S. aureus cap5 subclones were transformed into two ECA-negative mutant strains of E. coli (mutants 21546 and 21566 and the parental strain, AB1133, were kindly provided by P. D. Rick, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md.). Complementation was assessed by Western blot analysis of ECA expression, which is dependent on the activities of both the rffE and rffD gene products (8). Bacteria were grown at 37°C overnight in Luria-Bertani medium with 10 μg of tetracycline/ml, 100 μg of ampicillin/ml, and 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Western blot analysis was conducted as described previously (11), except for the use of 2% skim milk as a blocking agent, 2 μg of anti-ECA monoclonal antibody (MAb 898, kindly provided by D. Bitter-Suermann, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany)/ml, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated recombinant protein A (Zymed, South San Francisco, Calif.) diluted 1:1,000, and 3′,3,5′,5-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB membrane peroxidase substrate; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) to develop the blots. Blots and gels were imaged with the FOTO/Analyst archiver (Fotodyne, Inc., Hartland, Wis.) and processed with Adobe Photoshop 3.0 on a Power Macintosh 6100/66.

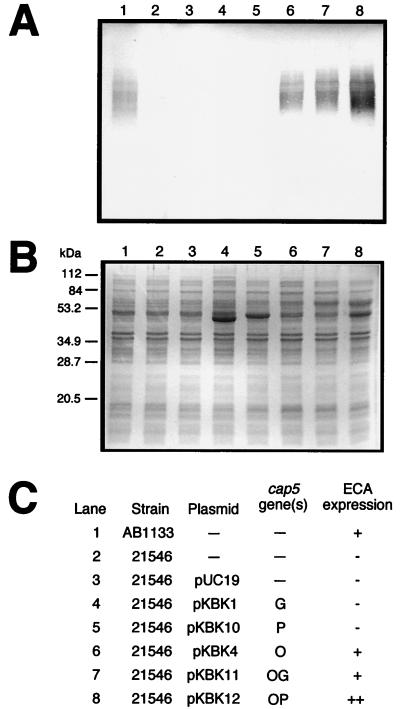

E. coli AB1133, the parent of the ECA-negative strains 21546 and 21566 (8), synthesized ECA polymers which were detected by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A and 4A, lanes 1). E. coli 21546, containing a Tn10 insertion in rffD, was shown previously to lack UDP-ManNAc dehydrogenase activity but to retain UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase activity (8). The Western blot confirmed that the rffD mutation in strain 21546 created an ECA-negative phenotype (Fig. 3A, lane 2). The mutant strain transformed with the pUC19 vector alone remained ECA negative (Fig. 3A, lane 3).

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of ECA expression by E. coli 21546 carrying the S. aureus cap5G, cap5P, and cap5O genes. Cell extracts were run on SDS–14% PAGE gels, and proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (A) or stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (B). An ECA-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb 898) was used to detect ECA polymers. Positions of molecular-mass markers run on the gel shown in panel B are indicated on the left. (C) Table identifying each sample run by strain, plasmid, cap5 gene, and resultant phenotype for ECA expression.

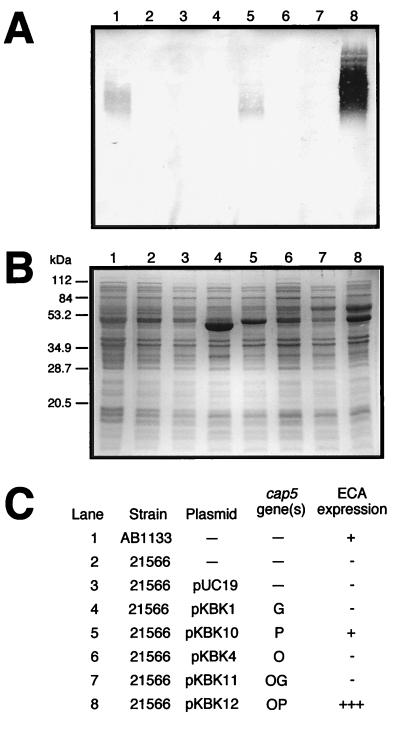

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of ECA expression by E. coli 21566 carrying the S. aureus cap5G, cap5P, and cap5O genes. Cell extracts were run on SDS–14% PAGE gels, and proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (A) or stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (B). An ECA-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb 898) was used to detect ECA polymers. Positions of molecular-mass markers run on the gel shown in panel B are indicated on the left. (C) Table identifying each sample run by strain, plasmid, cap5 gene, and resultant phenotype for ECA expression.

Expression of Cap5G from plasmid pKBK1, of Cap5P from plasmids pKBK10 and pKBK12, and of Cap5O from plasmid pKBK12 was readily visible by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic (SDS-PAGE) analysis; the proteins migrated near 47, 50, and 60 kDa, respectively (Fig. 3B and 4B, lanes 4, 5, and 8). The cap5G and cap5P genes, encoding putative UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerases, had no effect on ECA expression when introduced into strain 21546 (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 5, respectively). The lack of clearly visible Cap5O expression from plasmids pKBK4 and pKBK11 (Fig. 3B and 4B, lanes 6 and 7, respectively) is likely a result of the PCR subcloning of the cap5O gene. Since only 32 bp of cap5 sequence upstream of the cap5O initiation codon was present in plasmids pKBK4 and pKBK11, compared with 881 bp upstream of cap5O in plasmid pKBK12 (Fig. 2), translational initiation may be less efficient in the PCR subclones. However, expression of the cap5O-lacZ′ fusion from plasmid pKBK4 was confirmed by plating E. coli JM109 transformants in the presence of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) and IPTG, which gave rise to blue colonies. The cap5O gene, coding for a putative UDP-ManNAc dehydrogenase, was able to functionally complement the rffD mutation of strain 21546 (Fig. 3A, lanes 6 through 8). The cap5O PCR subclones restored ECA expression to a level similar to that of the wild type. However, in strain 21546/pKBK12, in which Cap5O expression was higher, ECA expression was likewise greater. The ability of each of the three cap5O subclones to complement the rffD mutation indicated that the recombinant Cap5O proteins were expressed and enzymatically active.

E. coli 21566 was shown previously to contain a Tn10 insertion in rffD, as well as an additional DNA insertion in rffE (7). As a result, this strain lacked both UDP-ManNAc dehydrogenase and UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase activities. Strain 21566 alone or carrying pUC19 was ECA negative by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 3, respectively). ECA expression was detected in strain 21566/pKBK10, containing the cap5P gene alone (Fig. 4A, lane 5). However, ECA expression was not detected when this strain was transformed with either plasmid pKBK1 (cap5G) or pKBK4 (cap5O) (Fig. 4A, lanes 4 and 6, respectively).

Plasmid pKBK12 (cap5O cap5P) transformed into strain 21566 restored ECA expression to a level greater than that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 4A, lane 8). When plasmid pKBK11 (cap5O cap5G) was introduced into strain 21566, no complementation was observed (Fig. 4A, lane 7). Similar to the expression of the PCR-cloned cap5O gene, Cap5G expression from pKBK11 was not clearly detectable by SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 4B, lane 7). However, expression of the cap5G-lacZ′ fusion from plasmid pKBK11 was confirmed by plating E. coli JM109 transformants in the presence of X-Gal and IPTG, which gave rise to blue colonies.

The complemented E. coli ECA-negative strains displayed variable phenotypes related to the level of ECA expression and size distribution of the ECA polymers. Strains 21546 and 21566 carrying the cap5O and cap5P genes in tandem (Fig. 3A and 4A, lanes 8) produced more ECA than the parental strain, AB1133 (Fig. 3A and 4A, lanes 1). The combination of the overexpressed cap5O and cap5P gene products most likely allowed for increased conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-ManNAcA, which in turn resulted in increased production of ECA. The ability of the cap5P gene alone to complement ECA expression in strain 21566, in which both rffE and rffD were inactivated, suggested that this strain had a low-level dehydrogenase activity that went undetected until the introduction of very high levels of its substrate, UDP-ManNAc. Increased synthesis of UDP-ManNAc through the 2-epimerization of UDP-GlcNAc would result from the high level of Cap5P expression from the multicopy pUC19 vector.

It also appeared that ECA polymer chain length was affected in strain 21566 complemented with cap5O and cap5P in tandem (Fig. 4A, lane 8). The predominant ECA polymers of this complemented strain migrated more slowly when separated by gel electrophoresis than those of the other ECA-positive strains. This did not appear to be an effect of overloading ECA polymers in the gel, since the predominant polymers of a diluted extract of strain 21566/pKBK12 also migrated at the higher molecular weight (data not shown). Little is known about the regulation of ECA chain length determination in E. coli. Factors such as the increased intracellular concentration of the ECA precursor UDP-ManNAcA may have influenced the regulation of polymer chain length in strain 21566.

The evidence gathered by functional complementation in E. coli indicates that the S. aureus cap5P and cap5O genes code for enzymes that catalyze the sequential conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-ManNAcA. We propose that one branch of the CP5 biosynthetic pathway consists of the enzymatic conversion of UDP-GlcNAc by a UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase (product of the cap5P gene) to UDP-ManNAc, followed by the oxidation of UDP-ManNAc by a UDP-ManNAc dehydrogenase (product of the cap5O gene) to form UDP-ManNAcA. Since the cap5O and cap5P genes are nearly identical to their cap8 counterparts, and since ManNAcA is a subunit constituent of both CP5 and CP8, this branch of the capsule biosynthetic pathway is likely conserved between the S. aureus type 5 and 8 strains.

To date, the activities of only three UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerases, E. coli RffE, S. pneumoniae type 19F Cps19fK, and S. enterica serovar Borreze RfbC, have been demonstrated biochemically or by genetic complementation (5, 8, 10, 12). We were not able to demonstrate function of the cap5G gene product in this analysis. Cap5G may serve as an epimerase in another branch of the CP5 biosynthetic pathway. Since the cap5G and cap8G genes lie in common regions of the cap5 and cap8 loci, respectively, and both CP5 and CP8 contain FucNAc residues, it is possible that these genes code for a nucleotide sugar epimerase involved in the biosynthesis of UDP-FucNAc, a putative donor of FucNAc residues.

On the basis of genetic evidence, it is probable that the cap5G gene is essential to S. aureus CP5 biosynthesis, since mutations in the nearly identical cap8G gene have been shown to eliminate S. aureus CP8 biosynthesis (15). Since mutations in cap8G are not complemented by the chromosomal copy of cap8P (15), it is unlikely that both genes code for the same enzyme. According to the proposed pathway, the enzymatic steps catalyzed by Cap5P and Cap5O are essential to CP5 biosynthesis. The cap8O gene, which is nearly identical to cap5O, is required for CP8 expression (15). In contrast, a mutation in cap8P, which is nearly identical to cap5P, does not affect CP8 expression (15). However, the mutation described was in frame and may not have completely inactivated the Cap8P enzyme. Mutational studies of the S. aureus cap5G, cap5O, and cap5P genes are in progress to confirm their roles in CP5 expression.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. D. Rick for helpful discussions and for donating bacterial strains. We are grateful to D. Bitter-Suermann for providing the anti-ECA monoclonal antibody.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI29040 and T32-AI07410 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Daniels D L, Plunkett III G, Burland V, Blattner F R. Analysis of the Escherichia coli genome: DNA sequence of the region from 84.5 to 86.5 minutes. Science. 1992;257:771–778. doi: 10.1126/science.1379743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fournier J M, Vann W F, Karakawa W W. Purification and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus type 8 capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1984;45:87–93. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.1.87-93.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ichihara N, Ishimoto N, Ito E. Enzymatic formation of uridine diphosphate N-acetyl-d-mannosaminuronic acid. FEBS Lett. 1974;39:46–48. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(74)80013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawamura T, Ishimoto N, Ito E. Enzymatic synthesis of uridine diphosphate N-acetyl-d-mannosaminouronic acid. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:8457–8465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keenleyside W J, Perry M, MacLean L, Poppe C, Whitfield C. A plasmid encoded rfbO:54 gene cluster is required for biosynthesis of the O:54 antigen in Salmonella enterica serovar Borreze. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:437–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J C, Xu S L, Albus A, Livolsi P J. Genetic analysis of type 5 capsular polysaccharide expression by Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4883–4889. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.4883-4889.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marolda C L, Valvano M A. Genetic analysis of the dTDP-rhamnose biosynthesis region of the Escherichia coli VW187 (O7:K1) rfb gene cluster: identification of functional homologs of rfbB and rfbA in the rff cluster and correct location of the rffE gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5539–5546. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5539-5546.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meier-Dieter U, Starman R, Barr K, Mayer H, Rick P D. Biosynthesis of enterobacterial common antigen in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13490–13497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreau M, Richards J C, Fournier J M, Byrd R A, Karakawa W W, Vann W F. Structure of the type-5 capsular polysaccharide of Staphylococcus aureus. Carbohydr Res. 1990;201:285–297. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(90)84244-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morona J K, Morona R, Paton J C. Characterization of the locus encoding the Streptococcus pneumoniae type 19F capsular polysaccharide biosynthetic pathway. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:751–763. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2551624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rick P D, Mayer H, Neumeyer B A, Wolski S, Bitter-Suermann D. Biosynthesis of enterobacterial common antigen. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:494–503. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.2.494-503.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sala R F, Morgan P M, Tanner M E. Enzymatic formation and release of a stable glycal intermediate: the mechanism of the reaction catalyzed by UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3033–3034. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sau S, Bhasin N, Wann E R, Lee J C, Foster T J, Lee C Y. The Staphylococcus aureus allelic genetic loci for serotype 5 and 8 capsule expression contain the type-specific genes flanked by common genes. Microbiology. 1997;143:2395–2405. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sau S, Lee C Y. Cloning of type 8 capsule genes and analysis of gene clusters for the production of different capsular polysaccharides in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2118–2126. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2118-2126.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sau S, Sun J, Lee C Y. Molecular characterization and transcriptional analysis of type 8 capsule genes in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1614–1621. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1614-1621.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wierenga R K, Terpstra P, Hol W G J. Prediction of the occurrence of the ADP-binding βαβ-fold in proteins, using an amino acid sequence fingerprint. J Mol Biol. 1986;187:101–107. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]