Abstract

The survival rates for relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) remain poor. We and others have reported that ALL cells are vulnerable to conditions inducing energy/ER-stress mediated by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). To identify the target genes directly regulated by AMPKα2, we performed genome-wide RNA-seq and ChIP-seq in CCRF-CEM (T-ALL) cells expressing HA-AMPKα2 (CN2) under normal and energy/metabolic stress conditions. CN2 cells show significantly altered AMPKα2 genomic binding and transcriptomic profile under metabolic stress conditions, including reduced histone gene expression. Proteomic analysis and in vitro kinase assays identified the TATA-Box–Binding Protein–Associated Factor 1 (TAF1) as a novel AMPKα2 substrate that downregulates histone gene transcription in response to energy/metabolic stress. Knockdown and knockout studies demonstrated that both AMPKα2 and TAF1 are required for histone gene expression. Mechanistically, upon activation, AMPKα2 phosphorylates TAF1 at Ser-1353 which impairs TAF1 interaction with RNA polymerase II (Pol II), leading to a compromised state of p-AMPKα2/p-TAF1/Pol II chromatin association and suppression of transcription. This mechanism was also observed in primary ALL cells and in vivo in NSG mice. Consequently, we uncovered a non-canonical function of AMPK that phosphorylates TAF1, both members of a putative chromatin-associated transcription complex that regulate histone gene expression, among others, in response to energy/metabolic stress.

Implications:

Fully delineating the protein interactome by which AMPK regulates adaptive survival responses to energy/metabolic stress, either via epigenetic gene regulation or other mechanisms, will allow the rational development of strategies to overcome de novo or acquired resistance in ALL and other cancers.

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common cancer and the main cause of cancer-related deaths in children and adolescents (1). Our previous data demonstrated AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-dependent vulnerability of ALL cells to energy/metabolic- and ER-stress (2–5). AMPK is a highly conserved heterotrimeric kinase complex composed of one catalytic α-subunit (α1 or α2) and two regulatory β (β1 or β2) and γ (γ1, γ2, or γ3) subunits (6, 7). AMPK senses changes in the AMP/ATP ratio resulting from energy/metabolic stress (e.g., glucose deprivation), leading to its activation. AMPK can be pharmacologically activated by small molecules such as 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribofuranoside (AICAR), biguanides, and others (8, 9). Upon activation, AMPK phosphorylates its substrates to stimulate catabolism and inhibit anabolism to restore cellular energy homeostasis.

AMPK plays a role in ALL biology. Deletion of AMPKα2 decreases cell viability in B-lineage ALL, and the B-lymphoid transcription factors PAX5 and IKZF1 act as metabolic gatekeepers to maintain AMPK activity (10). AMPK also regulates intermediates of cellular metabolism such as acetyl-CoA, α-ketoglutarate, and NAD, which are essential cofactors for chromatin-modifying enzymes. Emerging data suggest that AMPK epigenetically regulates transcription by binding to chromatin or chromatin-associated factors, such as phosphorylation of histone H2B, DNA methyltransferase TET2, and histone methyltransferase EZH2 (11–13).

TATA-Box–binding protein–associated factor 1 (TAF1; TAFII-250) is the largest subunit and core scaffold of the TFIID complex that make up the RNA polymerase II (Pol II) preinitiation complex (14). TAF1 interacts with transcription factors to modulate transcription initiation rates (15). It possesses histone acetyltransferase activity and intrinsic protein Ser/Thr kinase activity capable of autophosphorylation or transphosphorylation of transcription initiation factor TFIID subunit 7 (TAF7), general transcription factor IIF subunit 1 (GTF2F1, RAP74), tumor protein P53 (TP53), and others (16). TAF1 contains a tandem pair of bromodomains that interact with acetylated lysine residues on histones (17–19), known to play a critical role in AML1-ETO–driven leukemogenesis (20, 21). An analogous role for TAF1 has not yet been described in ALL.

Nucleosomes in chromatin are composed of DNA wrapped around eight histone proteins (two each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 subunits; ref. 22). The N-terminal tail of histones is post-translationally modified via methylation, phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitylation, and sumoylation (23), and these epigenetic marks dictate whether the genes are turned on or off. Histone gene expression is transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally controlled, and tightly regulated during the cell-cycle and DNA replication (23), and histone proteins regulate chromosome packaging, transcriptional activation/inactivation, DNA repair/recombination, and chromosome segregation (24).

In this study, we report that AMPKα2 associates with chromatin and co-localizes with Pol II across different regulatory regions in the genome. Both AMPKα2 and Pol II showed distinct patterns of chromatin occupancy following energy/metabolic stress, thereby regulating gene expression and inducing a robust transcriptional gene reprogramming, including downregulation of histone gene expression. Furthermore, we uncovered TAF1 as a new AMPKα2-binding partner and phosphorylation substrate in regulating histone gene expression. Mechanistically, in response to energy/metabolic stress, AMPKα2 phosphorylates TAF1 at Ser-1353 to alter TAF1-Pol II interaction, leading to histone gene downregulation. In conclusion, our study is the first to highlight the functional role of the metabolic sensor AMPKα2 in modulating TAF1 activity to reprogram gene expression and thereby rendering cancer cells vulnerable to metabolically challenged conditions.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, apoptosis, and proliferation assays

CCRF-CEM (T-ALL), KASUMI-2 (Bp-ALL), KE-37 (T-ALL), and HEK293T cell lines were obtained from the ATCC and/or DSMZ (Germany) and grown as indicated in the Supplementary Methods. All cell lines were authenticated by the manufacturer and tested for Mycoplasma, as previously described (25). Cell growth and apoptosis (Annexin V-FITC/PI) were assayed as previously described (26). The reagents used are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Plasmids, transfection, and lentivirus

Plasmids are described in the Supplementary Methods. HEK293T cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). CCRF-CEM cells were either nucleofected (Mirus, program C-005) or transduced with lentivirus. For lentivirus particles, the lentiviral packaging plasmids psPAX2 and pMD2.G were co-transfected into HEK293T cells and lentiviruses were collected at 48–72 hours and concentrated using a lenti-X concentrator (Clontech).

Western immunoblots, subcellular fractionation

Immunoblots were performed as described previously (27) and antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Subcellular fractionation was performed using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

In vitro kinase assay

The pCDH-HA-TAF1 and pCDH-HA plasmids were transfected into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After 24–48 hours, proteins were extracted from cell lysates and immunoprecipitated (1.5 mg) using Pierce HA-beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Phosphorylation reactions were performed using an AMPK in vitro Kinase Assay kit (SignalChem). Phosphorylated-TAF1 was visualized by Western blotting using an anti-phospho-serine/threonine/tyrosine antibody. The amount of the AMPKα2β1γ1 heterotrimeric kinase complex (His-AMPKα2) was assessed by immunoblotting using an anti-His antibody.

RNA isolation, RT-qPCR, and RNA-seq

RNA extraction, cDNA preparation, and TaqMan assays were performed as described previously (25). The TaqMan primers/probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) are listed in Supplementary Table S3. RNA-seq was performed at the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center (SCCC) Onco-Genomics Shared Resource Facility. Samples were sequenced using single-ends (75 bp) on an Illumina NextSeq-500 instrument. RNA-seq bioinformatics are described in the Supplementary Methods (Accession Number: GSE210214).

Mass spectrometry

HEK293T cells expressing HA-TAF1 (WT, wild-type) were treated ± AICAR (2.5 mmol/L) for 2 hours, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using Pierce HA beads. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated on 4%–12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gels and stained (Coomassie blue). Excised gel pieces were submitted to the Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility at the Harvard Medical School for phosphorylation analysis.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation, ChIP-seq, and ChIP-qPCR assays

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as previously described (28). The antibodies and primers for ChIP-qPCR/ChIP-seq are described in Supplementary Tables S4 and S5. ChIP-seq (library preparation and sequencing) was performed at the SCCC Onco-Genomics Shared Resource Facility. ChIP DNA samples were sequenced using single reads (75 bp; 30–40 M reads per sample) with an Illumina NextSeq-500; bioinformatics analysis is described in the Supplementary Methods (Accession Number: GSE210214).

Mouse ALL xenograft and bioluminescent imaging

CCRF-CEM-Luc cells’ engraftment in NSG mice and bioluminescent imaging assessment were performed as described previously (29) under the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were randomly assigned to three treatment groups (5 mice/group): Vehicle (control), TAF1 Inhibitor BAY-299 [150 mg/kg in 10% alcohol:50% PEG400:40% H2O, oral gavage (O.G.) daily], and AMPK activator phenformin (Phen, 150 mg/kg in H2O, O.G. daily). For RT-qPCR assays, spleens were harvested after 12 days of treatment, and RNA was extracted from isolated engrafted ALL cells.

Results

AMPKα2 is enriched at selected gene promoters and co-localized with RNA polymerase II on chromatin in ALL cells

AMPKα2 is the main AMPKα subunit translocated to the nucleus of mammalian cells, therefore we investigated its role in epigenetic gene regulation in ALL under energy/metabolic stress. A CCRF-CEM (T-ALL) stable cell line–expressing N-terminal epitope-tagged HA-AMPKα2 (CN2 cells) was generated, and immunoblots confirmed high HA-AMPKα2 expression in the whole-cell, cytoplasm, and nuclear fractions of CN2 cells (Fig. 1A, right). Importantly, HA-AMPKα2 was also detected in the chromatin-bound fraction, suggesting that nuclear AMPKα2 is associated with chromatin. As expected, no-glucose and AICAR conditions triggered significant AMPK/T172 phosphorylation (p-AMPK) as compared with the basal level of p-AMPK detected in untreated cells (Fig. 1A, left).

Figure 1.

AMPKα2 binds to chromatin and co-localizes with RNA polymerase II to regulate gene expression in ALL cells. A, Left, Western blot analysis of p-AMPK/T172 and total AMPK (t-AMPK) protein expression in whole-cell extract of CN2 (CCRF-CEM expressing HA-AMPKα2) cells untreated (control, CTRL) or treated with no-glucose or AICAR (500 μmol/L) for 24 hours. β-Actin was used as loading controls. Right, Western blot analysis of HA (HA-AMPKα2) and AMPKα2 in whole-cell lysate (Total), cytoplasmic (Cyto), nuclear (Nuc), and chromatin subcellular fractions of CN2 cells untreated (CTRL) or treated without glucose or with AICAR (500 μmol/L) for 24 hours. Histone H3 was used as chromatin loading controls and Lamin B was used as both chromatin and nuclear loading controls. The “*” indicates non-specific bands. B, Metaplot profiles showing HA-AMPKα2 ChIP-seq tags on HA-AMPKα2 bound chromatin regions (±1.0 kbp) in CN2 cells untreated (CTRL) or treated with no glucose for 24 hours. ChIP-seq was performed using anti-HA antibody. C, Genomic distributions of the 455 HA-AMPKα2 peaks identified in CN2-untreated cells. D, Venn diagram showing overlap of gene loci (441 annotated genes) exhibiting recruitment of HA-AMPKα2 and Pol II in CN2-untreated cells. ChIP-seq assays were performed using anti-HA or anti-Rpb1 (Pol II) antibody. E, Metaplot profiles showing HA-AMPKα2 and Pol II ChIP-seq tags on HA-AMPKα2 bound regions in the control in CN2 cells, in treated and untreated conditions. F, Bar graph showing the top enriched biological processes (with P values) identified in the HA-AMPKα2 and Pol II–overlapping gene set (239 genes) from CN2-untreated cells using Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Process library. G, Metaplot profiles showing recruitment of HA-AMPKα2 and Pol II to histone genes, TSS regions ± 5.0 kbp (left) and TSS regions ± 1.0 kbp (right) in CN2 cells untreated (CTRL) or treated with no glucose for 24 hours. H, ChIP-seq tracks showing HA-AMPKα2 and Pol II occupancy in the promoter proximal TSS regions of representative replication-dependent (H1–4, H4C4, H1–3, H1C7, H2AC8, H2BC8, H3C8, and H4C8) and replication-independent (H2AX) histone genes in CN2 cells treated ± glucose deprivation for 24 hours. I, ChIP-qPCR confirming decreased AMPKα2 (HA-AMPKα2) occupancy on the TSS region of H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4 histone gene promoters in CN2 cells treated with glucose deprivation for 24 hours versus untreated condition (CTRL). ChIP-qPCR were performed using anti-HA or IgG antibody. J, ChIP-qPCR confirming decreased AMPKα2 occupancy on the TSS region of H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4 histone gene promoters in KASUMI-2 cells treated with glucose deprivation or AICAR 500 μmol/L for 24 hours versus untreated condition (CTRL). ChIP-qPCR were performed using anti-AMPKα2 (Cell Signaling Technologies, 2757) or IgG antibody. Error bars represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). Significance was assessed using the two-tailed Student t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To further explore the significance of chromatin-bound HA-AMPKα2, we performed ChIP-seq in CN2 cells using an anti-HA-tag antibody under control versus energy/metabolic stress conditions (no glucose). ChIP-seq identified 455 HA-AMPKα2 chromatin-bound peaks, corresponding to 441 annotated genes in the control condition, which were reduced or showed no binding to chromatin under glucose deprivation conditions (Fig. 1B). Of the 455 HA-AMPKα2 peaks, approximately 40% were bound to intergenic regions, and approximately 45% (44.3%) were enriched in promoter and promoter proximal regions (Fig. 1C), underlying the regulatory potential of AMPKα2 binding to chromatin. The observed enrichment of HA-AMPKα2 peaks in gene transcriptional regulatory regions led us to investigate the occupancy of Pol II at the HA-AMPKα2 bound 441 annotated genes in CN2 cells. Interestingly, we detected that 54% (239 annotated genes) of HA-AMPKα2–bound regions were co-bound with Pol II (Fig. 1D), which were also reduced or lost under metabolic stress condition (Fig. 1E), further substantiating the regulatory potential of AMPKα2 binding to chromatin to actively regulate gene transcription and coordinate cellular metabolic status in response to energy/metabolic stress.

To identify the molecular functions of these AMPKα2 and Pol II co-bound chromatin regions in CN2 cells, we performed the Gene Ontology (GO) term analysis (30). The analysis revealed enriched occupancy of genes involved in chromatin organization, such as nucleosome assembly, telomere organization, spliceosome, and chromatin silencing (Fig. 1F). Among these genes, we uncovered a cluster of histone genes that were enriched for both AMPKα2 and Pol II, and exhibited decreased recruitment of HA-AMPKα2 and Pol II at their promoter regions following glucose deprivation (Fig. 1G). As depicted (Fig. 1H; Supplementary Fig. S1A–S1C), ChIP-seq tracks showed decreased HA-AMPKα2 and Pol II recruitment to selected histone gene promoters in CN2 cells following glucose deprivation. These data were confirmed using ChIP-qPCR in CN2 cells (Fig. 1I) and validated in Bp-ALL (KASUMI-2; Fig. 1J) and T-ALL (KE-37; Supplementary Figs. S1D and S2A and S2B) cell lines under energy/metabolic stress conditions.

AMPKα2 activation suppresses histone gene transcription in response to energy/metabolic stress in ALL cells

To correlate gene mRNA expression and recruitment of AMPKα2 to chromatin, we performed RNA-seq in CN2 cells grown ± glucose for 24 hours. RNA-seq identified 3,497 differentially expressed genes in response to energy/metabolic stress as compared with untreated cells (Fig. 2A), and 60%–70% exhibited downregulation. BioPlanet gene set analysis (31) indicated that downregulated genes were enriched in energy-expending pathways, such as DNA replication, cell cycle, and cellular metabolism (Fig. 2B). RNA-seq analysis also identified 51 differentially downregulated histone genes following glucose deprivation (Fig. 2C), which was confirmed by RT-qPCR for selected histone genes (H1–2, H1–3, H4C4) in Bp-ALL (KASUMI-2) and T-ALL (CCRF-CEM, KE-37) cells under the same conditions (Fig. 2D–F). Our data establish a role for AMPKα2 and a direct correlation between histone gene mRNA downregulation and decreased recruitment of AMPKα2 to promoter proximal regions of histone gene loci.

Figure 2.

RNA-seq data analysis: AMPK regulates histone gene expression in ALL cells. A, Heat map of 3,497 differentially expressed genes identified in CN2 cells untreated (CTRL) versus treated with glucose deprivation for 24 hours (fold change >1.5 or ≤1.5, q value < 0.05). B, Bar graphs showing top 10 biological processes (with P values) identified in genes downregulated by no glucose treatment in CN2 cells using the BioPlanet 2019 gene set analysis. C, Heat map of 54 histone differentially expressed genes in CN2 cells untreated (CTRL) versus treated without glucose for 24 hours (fold change >1.5 or ≤1.5, q value < 0.05). D–F, AMPK downregulates histone gene expression in response to energy/metabolic stress. Levels of H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4 histone gene mRNA expressions in CCRF-CEM (D), KASUMI-2 (E), and KE-37 (F) cells untreated (CTRL) or treated without glucose or AICAR 500 μmol/L for 24 hours. RT-qPCR data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA level and expressed as relative to untreated cells. G, Levels of PRKAA2, H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4 mRNA expressions in CCRF-CEM tet-shAMPKα2 cells treated with or without doxycycline (Dox) for 48 hours, and then treated with or without glucose deprivation or AICAR 500 μmol/L for 24 hours. RT-qPCR data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA level and expressed as relative to untreated control cells (–Dox CTRL). H, Western blot analysis of AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 expression in HEK293T CRISPR control (CTRL) and CRISPR AMPKα1/α2 DKO cells. β-Actin was used as loading controls. I, Levels of H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4 mRNA expressions in HEK293T CRISPR control (CTRL) and CRISPR AMPKα1/α2 DKO cells. RT-qPCR data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA level and expressed as relative to CTRL. J, Levels of H1–2, H1–3 and H4C4 mRNA expression in CCRF-CEM cells transfected with or without constitutively active HA-AMPKα2 T172D mutant plasmid. RT-qPCR data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA level and expressed as relative to control (CTRL) cells. Error bars represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). Significance was assessed using the two-tailed Student t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To confirm the role of AMPKα2 on histone gene transcription, we generated a stable tetracycline/doxycycline (Dox)-inducible shAMPKα2 CCRF-CEM cell line to downregulate AMPKα2 expression in CCRF-CEM cells, and examined histone gene mRNA expression in AMPKα2 knockdown cells under metabolic stress. As shown in Fig. 2G, the level of PRKAA2 (AMPKα2) mRNA transcript was significantly reduced (>80%) in CCRF-CEM/tet-shAMPKa2 cells upon Dox-induced shRNA expression. Strikingly, we observed reduced levels of H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4 mRNA transcripts upon AMPKα2 knockdown, suggesting that AMPKα2 acts as a transcriptional activator under non-stressed conditions (Fig. 2G, Dox+ Control). A further reduction in H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4 mRNA transcript levels was noted upon the induction of metabolic stress (Fig. 2G, +Dox No-glucose and AICAR).

To further confirm these data, we generated AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 knockout HEK293T cells using CRISPR/Cas9. As we detected both AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 isoforms in the nucleus and chromatin-bound fractions (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. S3), suggesting that AMPKα1 could have a role similar to AMPKα2 in regulating gene expression, we examined the effect of both AMPK isoforms on histone gene transcription using the AMPKα1/AMPKα2 double knockout (DKO) cell line. Immunoblot confirmed the knockout of both AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 expressions in HEK293T AMPKα1/AMPKα2 DKO cells, and RT-qPCR validated histone H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4 mRNA downregulation in AICAR-treated HEK293T cells versus untreated control (Fig. 2H–I). Consistent with our CCRF-CEM/tet-shAMPKα2 data (Fig. 2G), AMPKα1/AMPKα2 DKO itself in HEK293T cells significantly downregulated histone gene mRNA expression (Fig. 2I). AMPKα1/AMPKα2 DKO cells treated with AICAR exhibited additional histone gene downregulation (Fig. 2I). We interpret this finding as a result of the known off-target AMPK-independent effects of AICAR on gene expression, cell cycle and/or apoptosis (2, 4, 25, 32). Nevertheless, the significant downregulation of histone gene mRNA expression in untreated AMPKα1/AMPKα2 DKO compared with WT HEK293T cells clearly suggests that AMPKα2 acts as transcription activator in normal conditions and its concomitant dissociation following activation leads to decreased histone gene transcription in response to energy/metabolic stress in ALL cells.

Finally, to investigate the role of AMPK kinase activity, we determined the effect of the constitutively active (CA)-AMPKα2/T172D mutant on histone gene expression in CCRF-CEM cells. Indeed, expression of CA-AMPKα2 significantly decreased histone H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4 mRNA expressions in CCRF-CEM cells (Fig. 2J), suggesting that AMPK kinase activity plays a role in histone gene downregulation following energy/metabolic stress.

AMPKα2 phosphorylates TAF1 at ser-1353

AMPK lacks a DNA-binding domain, suggesting that chromatin binding occurs via interaction with other chromatin-associated protein(s). To identify members of a putative AMPKα2-chromatin–associated transcription complex, we analyzed the HA-AMPKα2 and Pol II–overlapping gene set (239 genes) from untreated CN2 cells using the Encode and ChEA consensus TFs CHIP-X database. We identified the negative elongation factor E (NELFE), TAF7, promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML), and TAF1 as potential AMPKα2 targets/partners on chromatin (Fig. 3A). Using Scansite [Home—Scansite 4 (mit.edu)], a software designed to search for motifs within proteins potentially phosphorylated by kinases (e.g., AMPK; ref. 33), we identified TAF1 as a putative AMPK-phosphorylated target. To determine whether AMPK interacts with TAF1, we performed Co-IP assays in HEK293T cells co-transfected with vectors overexpressing Flag-AMPKα2 and HA-TAF1, and pulled-down AMPKα2 and TAF1 using anti-Flag-tag or anti-HA-tag antibodies, respectively. Figure 3B shows that AMPKα2 co-immunoprecipitated with TAF1, and conversely, TAF1 co-immunoprecipitated with AMPKα2, validating their interaction. This AMPK–TAF1 interaction was also confirmed in control and glucose-deprived CN2 cells (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

AMPKα2 interacts with the TATA-Box–Binding Protein–Associated Factor (TAF) and phosphorylates TAF1 at Ser-1353. A, Bar Graph showing the top 10 transcription factors (TF; with P values) identified in the HA-AMPKα2 and RNA Pol II–overlapping gene set (239 genes) from CN2 untreated cells using the “ENCODE and ChEA Consensus TFs from ChIP-X” gene set library. B and C, AMPKα2 interacts with the TAF1 protein. B, Lysates from HEK293T cells co-transfected with vectors overexpressing Flag-AMPKα2 and HA-TAF1 were immunoprecipitated using anti-HA or anti-FLAG antibody, and Co-IP products were examined by Western blotting using anti-Flag (Flag-AMPKα2) and anti-HA (HA-TAF1) antibodies. β-Actin was used as loading controls. C, Lysates from CN2 cells treated with or without glucose starvation for 24 hours were immunoprecipitated using an anti-TAF1 antibody, and Co-IP products were examined by immunoblotting using anti-HA (HA-AMPKα2) and anti-TAF1 antibodies. The input represents 10% of the cell lysates used in the Co-IP experiments. Arrow indicates HA-AMPKα2 band detected in TAF1-IP products. D, Diagram of TAF1 WT full-length and truncated TAF1 peptides. The full-length TAF1 (TAF1 FL, 1893 amino acids) consists of five domains: the N-terminal kinase, histone acetyltransferase (HAT), RAP74 binding domain (RAPiD), zinc knuckle motif (Zn), two bromodomains (2XBRM), and C-terminal kinase domains. The truncated TAF1 protein-expressing constructs contain either the N-terminal (AA 1–516), the middle segment (AA 517–1358), or the C-terminal domain (AA 1361–1893). DNA fragments encoding full-length or truncated TAF1 proteins were cloned into the pCDH-MSCV-HA TAF1-EF1-copGFP vector, as described in the Materials and Methods. E, Cell extracts from HEK293T cells co-transfected with genetic constructs expressing TAF1 WT full-length (FL) or truncated TAF1 proteins (N, N-terminal domain amino acids 1–516; M, middle segment amino acids 517–1358; and C, C-terminal domain amino acids 1361–1893), and Flag-AMPKα2 were immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag antibody, and the Co-IP products were examined by Western blotting using anti-HA (HA-TAF1) and anti-Flag (FLAG-AMPKα2) antibodies. β-Actin was used as loading controls. The input represented 10% of the cell lysate used in the Co-IP experiment.

TAF1 contains two kinase domains (N-terminal and C-terminal), a histone acetyltransferase domain (HAT), a RAP74-binding domain (RAPiD), a zinc knuckle motif (Zn), and two bromodomains (refs. 20, 21, 34; Fig. 3D). To determine which TAF1 domain(s) interact with AMPKα2, we generated genetic constructs expressing truncated HA-TAF1 peptides to include either the N-terminal kinase domain, mid-portion domain (HAT/RAPiD/Zn), or the C-terminal domain (bromodomains, C-terminal kinase; Fig. 3D). These were co-transfected with the Flag-AMPKα2 vector into HEK293T cells, and Co-IP assays were performed. We show that TAF1’s N-terminal domain (N) exhibited strong binding affinity with AMPKα2 compared with the other truncated HA-TAF1 peptides, suggesting that AMPKα2 binds primarily to TAF1’s N-terminal domain (Fig. 3E).

To determine whether TAF1 is phosphorylated by AMPK, we performed an in vitro kinase assay. Lysates from HA-TAF1–transfected HEK293T cells were immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA antibody and incubated ± the active AMPKα2β1γ1 heterotrimeric kinase complex. Phosphorylated TAF1 (p-TAF1) was detected only when incubated with the active AMPKα2β1γ1 kinase complex (Fig. 4A, bottom), indicating direct TAF1 phosphorylation by AMPKα2β1γ1. Furthermore, we detected enhanced TAF1 phosphorylation in vivo following AMPK activation/phosphorylation by AICAR (increased p-ACC/S79) in HEK293T and CCRF-CEM (Fig. 4B and C) cells. These results were consistent with the above Co-IP data (Fig. 3C) and further confirmed in HEK293T AMPKα2 knockout cells (AMPKα2 KO), in which TAF1 phosphorylation was significantly reduced in AICAR-treated cells compared with control cells (Fig. 4D). Consequently, AMPKα2 expression/activation is required for TAF1 phosphorylation.

Figure 4.

AMPKα2 phosphorylates TAF1 at Ser-1353 in ALL cells in response to energy/metabolic stress. A, Top, Lysates from HEK293T cells transfected with pCDH-HA-TAF1 (HA-TAF1) or pCDH-HA (HA-empty vector) were immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA antibody. Bottom, The immuno-purified products were incubated with or without the active AMPKα2β1γ1 heterotrimeric kinase complex. Phosphorylated proteins (p-TAF1) were detected using an anti–phospho-serine/threonine/tyrosine (p-S/T) antibody. Anti-His antibody was used to detect His-AMPKα2 to assess the amount of the AMPKα2β1γ1 heterotrimeric kinase complex in the assay (see the Materials and Methods). The input represents 10% of the cell lysates used in the co-IP experiments. β-Actin was used as loading controls. B and C, TAF1 is phosphorylated in response to metabolic stress. B, HEK293T cells expressing HA-TAF1 or HA-empty vector were treated with or without AICAR (2.5 mmol/L) for 2 hours, and cell lysates were subjected to IP assays using an anti-HA antibody. The Co-IP products were examined by Western blotting using anti-HA, anti-phospho-(Ser/Thr) AMPK substrate, and anti-phospho-Ser/Thr antibodies. Input materials (10% of cell lysates) of HEK293T untreated and AICAR-treated cells were examined by Western blotting to detect p-ACC S79 and total ACC (T-ACC) protein expression. β-Actin was used as loading controls. C, CCRF-CEM cells were treated with or without AICAR (2 mmol/L) for 2 hours, and cell lysates were subjected to IP assays using an anti-TAF1 or normal IgG antibody. The Co-IP products were examined by Western blotting using anti-TAF1, anti-AMPK, and anti-phospho-(Ser/Thr) AMPK substrate antibodies. The input materials (10% of cell lysates) of CCRF-CEM–untreated and AICAR-treated cells were analyzed by Western blotting to detect TAF1 and AMPK protein expression. D, HEK293T control (CTRL) and HEK293T/AMPKα2 KO cells expressing HA-TAF1 were treated with or without AICAR (2.5 mmol/L) for 2 hours, and cell lysates were subjected to IP assays using an anti-HA antibody. The Co-IP products were examined by Western blotting using anti-HA and anti-phospho-(Ser/Thr) AMPK substrate antibodies. Input materials (10% of cell lysates) were analyzed for TAF1 (HA-TAF1) and AMPKα2 protein expression. β-Actin was used as loading controls. E, TAF1 is phosphorylated at S1353 in response to metabolic stress. Top, Amino acid sequence alignment of a TAF1 region spanning the putative phosphorylation site Ser1353 among mammalian species. Schematic representation of the TAF1 structural domains to illustrate the position of the S1353 residue. Bottom, HEK293 cells expressing HA-TAF1 (WT) or HA-TAF1 S1353A were treated with or without AICAR (2.5 mmol/L) for 2 hours, and cell lysates were subjected to IP assays using an anti-HA antibody. The Co-IP phosphorylated products were examined by Western blotting using anti-HA, anti-phospho-(Ser/Thr) AMPK substrate, and a p-S/T antibody. The input materials (10% of cell lysates) were analyzed for TAF1 (HA-TAF1) protein expression. β-Actin was used as loading controls. F, Lysates from H293T cells co-transfected with vectors expressing HA-TAF1 (WT) or HA-TAF1 S1353A, and either constitutively active AMPKα2 (Flag-AMPK T172D) or inactive AMPKα2 (HA-AMPK T172A) vectors were IP with an anti-HA antibody, and Co-IP products were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HA (HA-TAF1), anti-Flag (Flag-AMPKα2), and anti-phospho-(Ser/Thr) AMPK substrate antibodies. Input materials (10% of cell lysates) were analyzed for TAF1 (HA-TAF1) and AMPKα2 (Flag-AMPKα2) protein expressions. β-Actin was used as loading controls.

Finally, using tandem mass spectrometry (MS), we identified putative TAF1 phosphorylation site(s) targeted by AMPK in AICAR-treated HEK293T cells expressing HA-tagged-TAF1 (Supplementary Table S6). On the basis of its phospho-peptide intensity score (45,000), we selected and further characterized the TAF1 residue Ser-1353 as the AMPK-targeted phosphorylation site. The TAF1 Ser-1353 residue is located between the zinc knuckle motif and bromodomains, a highly conserved region in mammals (Fig. 4E). To validate TAF1 Ser-1353 as an AMPK phosphorylation site, we generated mutant TAF1 S1353A by substituting Ser-1353 with alanine using site-directed mutagenesis. Phosphorylation of TAF1 S1353A was significantly lower compared with WT TAF1 in AICAR-treated HEK293T cells (Fig. 4E), validating Ser-1353 as a TAF1 AMPK-phosphorylated site. To examine the phosphorylation of TAF1 WT versus the TAF1 S1353A mutant, we used plasmids expressing constitutively active (CA) or inactive/dominant-negative (DN) AMPKα2 isoforms. HA-TAF1 WT or HA-TAF1 S1353A constructs were co-transfected with CA-AMPKα2 (Flag-AMPK/T172D) or DN-AMPKα2 (HA-AMPK/T172A) vectors in HEK293T cells and TAF1 WT versus TAF1 S1353A mutant phosphorylation examined. Immunoblots using antibody that recognizes p-AMPK substrate motif to probe phospho-TAF1 demonstrated greater TAF1 WT phosphorylation in CA-AMPKα2 compared with DN-AMPKα2–expressing cells, which was also significantly greater than the phosphorylation of the TAF1 S1353A mutant in CA-AMPKα2–expressing cells (Fig. 4F). These data strongly support the TAF1 Ser-1353 residue as a prime AMPK phosphorylation site.

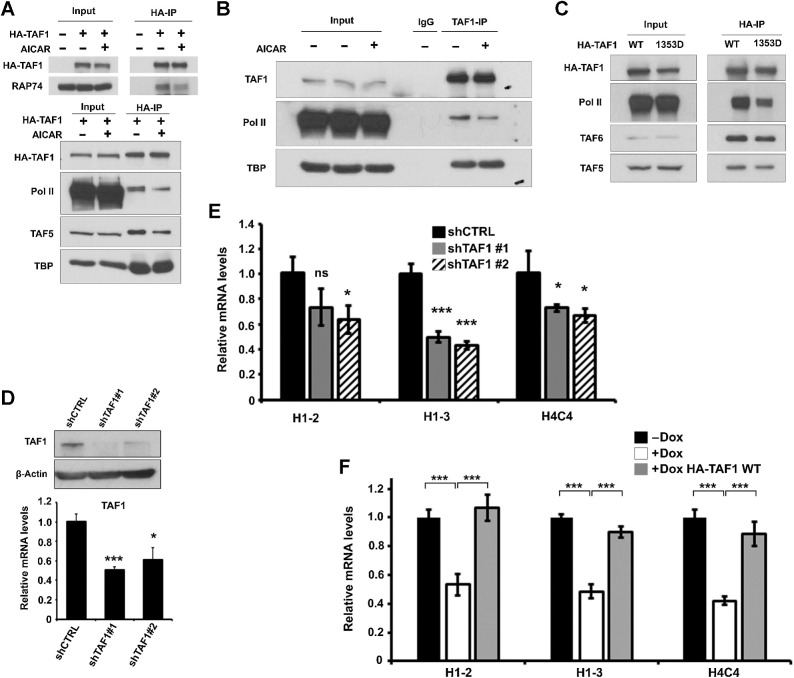

TAF1 phosphorylation at ser-1353 impairs its interaction with RNA polymerase II

To investigate the physiological relevance of TAF1 phosphorylation in ALL cells, we examined its transcriptional role in response to energy/metabolic stress. TAF1 is a member of the Pol II transcription preinitiation complex, which includes the Pol II-associated proteins RAP74 and RAP30 (14). To test whether TAF1 phosphorylation alters its binding ability to RAP74 and Pol II, we performed Co-IP using cell extracts from HEK293T and CCRF-CEM cells treated ± AICAR to induce AMPK-mediated TAF1 phosphorylation. Fig. 5A shows that the binding ability of TAF1 to RAP74 and Pol II was decreased in AICAR-treated HEK293T cells compared with untreated cells, and similarly decreased in AICAR-treated CCRF-CEM cells (Fig. 5B), suggesting that phosphorylation of TAF1 by AMPK alters its interaction with the Pol II transcription complex under energy/metabolic stress. In addition, p-TAF1 exhibited decreased binding affinity to other members of the TFIID complex, such as TAF5 (Fig. 5A), whereas p-TAF1’s interaction with the TATA-box–binding protein (TBP) remained unaltered (Fig. 5A and B). These data are consistent with a previous report, indicating that TAF1 and TBP can form a small complex in the cytoplasm before interacting with other components of TFIID (e.g., TAF5 and TAF6) during assembly of the TFIID complex (35).

Figure 5.

Phosphorylation of TAF1 at S1353 impairs its interaction with RNA polymerase II. A, HEK293T cells expressing HA-TAF1 were treated with or without AICAR (2.5 mmol/L) for 2 hours, and cell lysates subjected to IP experiments using anti-HA antibody. The input materials (10% of cell lysates) and Co-IP products were examined by Western blots using anti-HA (HA-TAF1), RAP74, RPB1 (Pol II), TAF5 and TBP antibody. B, CCRF-CEM cells were treated with or without AICAR (2.5 mmol/L) for 2 hours, and cell lysates subjected to IP experiments using anti-TAF1 or normal IgG antibody. The input (10% of cell lysates) and Co-IP products were analyzed by Western blots using anti-TAF1, anti-RPB1 (Pol II), and anti-TBP antibody. C, Cell lysates from HEK293T cells expressing HA-TAF1 (WT) or HA-TAF1 S1353D (mutant mimicking TAF1 serine 1353 phosphorylation state) were subjected to IP experiments using anti-HA antibody. The input (10% of cell lysates) and Co-IP products were examined by Western blots using anti-HA (HA-TAF1), RPB1 (Pol II), TAF5, and TAF6 antibody. D, Top, Western blot analysis of TAF1 expression in CCRF-CEM cells transfected with scramble shRNA (shCTRL) or shRNA targeting TAF1 (shTAF1#1, shTAF1#2). β-Actin was used as loading controls. Bottom, Levels of TAF1 mRNA expression in CCRF-CEM cells transfected with scramble shRNA (shCTRL) or shTAF1 (#1, #2). RT-qPCR data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA level and expressed as relative to shCTRL. E, Levels of histone H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4 gene mRNA expressions in CCRF-CEM cells transfected with scramble shRNA (shCTRL) or shTAF1 (#1, #2). RT-qPCR data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA level and expressed as relative to shCTRL. Significance was assessed using the two-tailed Student t test. F, CCRF-CEM tetracycline-inducible shTAF1 cells were transduced with lentivirus particles expressing HA-TAF1 (WT) and induced for 3 days with doxycycline (Dox) before protein and mRNA expression analysis. Levels of H1–2, H1–3 and H4C4 mRNA expression in these CCRF-CEM tet-shTAF1 cells treated ± Dox. RT-qPCR data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA level and expressed as relative to untreated Dox treated cells. Significance was assessed using an ANOVA multiple comparison test. ns, non-significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To confirm that TAF1 phosphorylation at Ser-1353 is causal for the observed decreased binding to RAP74 and Pol II, the TAF1 S1353D mutant (serine for aspartate substitution), known to mimic serine's phosphorylation state, was generated by site-directed mutagenesis and its interaction with RAP74 and Pol II compared with TAF1 WT. As shown in Fig. 5C, the TAF1 S1353D and Pol II interaction was significantly decreased compared with that of TAF1 WT, indicating that p-TAF1 (Ser1353) was responsible for its impaired binding to the Pol II transcription complex. Consistent with this finding (Fig. 5A), the TAF1 S1353D mutant exhibited altered binding to both TAF5 and TAF6, confirming that AMPK phosphorylation of TAF1 at S1353 impairs its interaction with members of the TFIID complex. Therefore, our data show that in response to energy/metabolic stress, AMPKα2 directly phosphorylates TAF1, decreasing its interaction with the Pol II complex and subsequently altering gene transcription.

AMPK–TAF1 regulates histone gene expression in ALL cell lines, primary cells, and in ALL cells grown in vivo in NSG mice

To test whether TAF1 plays a role in histone gene transcription in ALL cells, we used shRNA TAF1 to knockdown TAF1 expression in CCRF-CEM cells (Fig. 5D) and examined histone mRNA expression. TAF1 knockdown in CCRF-CEM cells led to significant downregulation of histone gene mRNA (H1–2, H1–3, H4C4) compared with scramble shRNA (shCTRL; Fig. 5E). To confirm these data, we performed rescue experiments using a Dox-inducible shTAF1 CCRF-CEM stable cell line, in which TAF1 (WT) was introduced via lentivirus transduction. Histone gene expression (H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4) was decreased in Dox-induced TAF1-knockdown CCRF-CEM, and more importantly, rescued by overexpression of TAF1 WT (HA-TAF1 WT), strongly confirming the requirement of TAF1 in histone gene transcription in ALL cells (Fig. 5F). To determine whether p-TAF1 alters histone mRNA expression in ALL cells, we compared the effect of TAF1 (S1353D; mimicking p-TAF1) mutant with TAF1 WT in Dox-inducible shTAF1 CCRF-CEM cells, and found that expression of the TAF1 (S1353D) mutant lowered histone gene mRNA expression compared with TAF1 (WT; P < 0.05–0.001; Supplementary Fig. S4). Consequently, TAF1 phosphorylation at Ser-1353 decreases the mRNA expression of histone genes.

TAF1 decreased binding affinity to Pol II under energy/metabolic stress conditions suggested that TAF1 may regulate histone gene expression through binding to chromatin. To test this, we performed ChIP-qPCR with TAF1 and Pol II antibodies in Bp-ALL (KASUMI-2) and T-ALL (CN2, KE-37) cells treated with glucose deprivation or AICAR. We found that recruitment of TAF1 to histone gene promoters (H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4) was significantly decreased in both AICAR-treated and glucose-deprived Bp- and T-ALL cells (Fig. 6A–C), and decreased Pol II occupancy to histone gene loci following TAF1 phosphorylation by AMPK in ALL (Supplementary Fig. S2A and S2B). These data support a mechanism by which p-TAF1 downregulates the transcription of histone genes by dissociating from the AMPK–TAF1–Pol II chromatin-associated transcription complex in response to energy/metabolic stress in ALL.

Figure 6.

TAF1 binds to histone promoter TSS regions to regulate gene expression in ALL cell lines, primary cells, and in ALL cells grown in vivo in NSG mice. A–C, TAF1 enrichment on the TSS region of histone genes is decreased in ALL cells in response to metabolic/energy stress. ChIP-qPCR showing decreased TAF1 occupancy on the TSS region of H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4 histone gene promoters in CN2 (A), KASUMI-2 (B), and KE-37 (C) cells treated with glucose deprivation for 24 hours or AICAR (500 μmol/L) for 24 hours versus untreated condition (CTRL). ChIP-qPCR were performed using anti-TAF1 or anti-IgG antibody. D, AICAR-induced phosphorylation of TAF1 downregulates histone gene expression in primary ALL cells. Levels of H1–2, H1–3 and H4C4 mRNA expression in Patient #1 (pre-B ALL), Patient #2 (pre-B ALL), and Patient #3 (T-ALL) treated with AICAR (500 μmol/L) for 24 hours. RT-qPCR data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA level and expressed as relative to untreated cells. E, TAF1 interacts with AMPK in primary Bp-ALL cells (Patient #2). Cell lysates were subjected to IP assays using anti-TAF1 or anti-IgG antibody. The input (10% of cell lysates) and Co-IP products were examined by Western blots using anti-AMPK and anti-TAF1 antibody. Arrow indicates AMPK band detected in TAF1-IP products. F, TAF1 interacts with Pol II in primary Bp-ALL cells (Patient #2) treated with or without AICAR (500 μmol/L) for 24 hours. Cell lysates were subjected to IP assays using anti-TAF1 or anti-IgG antibody. The input (10% of cell lysates) and Co-IP products were examined by Western blots using anti-TAF1 and anti-RPB1 (Pol II) antibody. β-Actin was used as loading controls. G, Representative analysis of bioluminescent signal demonstrating engraftment in 5 NSG mice (with CCRF-CEM-Luc cells) determined at day 12 after injection following treatment with vehicle (Control), BAY-299 (150 mg/kg), and phenformin (150 mg/kg) as described in the Materials and Methods. H, Levels of H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4 mRNA expressions in ALL cells collected from spleen of engrafted mice treated with vehicle (Control), BAY-299 and phenformin (Phen) at day 12. RT-qPCR data were normalized to Gapdh mRNA level and expressed as relative to untreated cells. Error bars represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). Significance was assessed using the two-tailed Student t test between treatment and Control. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To probe the physiological relevance of this putative AMPK–TAF1–Pol II–histone regulatory axis, we examined the effect of energy/metabolic stress on histone gene mRNA expression and the interaction between TAF1–AMPKα2–Pol II in primary ALL patient samples. RT-qPCR showed that the mRNA expression of selected histone genes (H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4) was significantly decreased in AICAR-treated primary Bp-ALL (Patients #1 and #2) and T-ALL (Patient #3) samples (Fig. 6D) compared with untreated cells. Immunoblots confirmed the AMPK–TAF1 interaction (Fig. 6E) and decreased TAF1-Pol II binding in AICAR-treated primary ALL cells (Fig. 6F). These data validate the physiological relevance of our findings in cell line models. In addition, we treated NSG mice engrafted with human CCRF-CEM-Luc cells (confirmed by bioluminescence detection; Fig. 6G) with the TAF1 inhibitor BAY-299 (36) or the AMPK-activator phenformin (37) and examined histone gene transcription in vivo. Similar to AICAR, both BAY-299 and phenformin have been shown to inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis in ALL cells (Supplementary Fig. S5A–S5D; refs. 2, 4, 25, 38). We found that the level of mRNA expression of selected histone genes (H1–2, H1–3, and H4C4) was significantly decreased in CCRF-CEM-Luc cells collected from spleens of engrafted mice treated for 12 days with BAY-299 or phenformin (Phen) as compared with vehicle (control, CTRL; Fig. 6H). These in vivo data are consistent with and confirm our in vitro findings in human cell lines and primary ALL patient cells, suggesting the potential clinical relevance of the AMPK/TAF1/Pol II/histone regulatory mechanism(s) described herein.

Discussion

In the present study, we uncovered the transcription factor TAF1 as a novel AMPKα2 substrate within a putative multi-protein chromatin-associated complex that, following AMPK's TAF1 phosphorylation at Ser1353, downregulates histone gene transcription, among others, in ALL cells in response to energy/metabolic stress.

Genomic profiling and transcriptomic analysis of CN2 (T-ALL) cells enabled us to identify the target genes whose promoters and proximal regulatory regions were co-bound by AMPKα2 and Pol II. The prominent GO terms analysis (mRNA splicing, DNA methylation, PRC2 histone methylation, Histones) suggested that AMPKα2 regulates important cellular functions critical to genome integrity and cell viability. AMPK has been reported to bind to p53-targeted gene promoters and phosphorylate histone H2B at S36, to promote cell survival (11). In our study, we found that AMPK knockdown led to reduced levels of histone gene transcription, suggesting the AMPK ability to activate transcription and control cellular proliferation by regulating cellular homeostasis of histones. It is conceivable that under normal physiological conditions, AMPK activates histone gene expression and promotes cellular proliferation. However, the encountered metabolic stress conditions and consequent AMPK activation, leads to the suppression of histone genes, enabling the cells to survive in metabolically challenged conditions. The paradoxical roles of AMPK have been reported, AMPK has been described as tumor-suppressor or tumor-promoting oncogene (38–40), depending on the cellular context. Our findings suggest that AMPK might act as a tumor-promoting oncogene in our experimental model, encouraging a state of quiescence and enabling cancer cell survival under metabolically challenged conditions.

We and others have previously reported that the AMPK activator AICAR induces a diverse set of anti-proliferative (cell-cycle arrest, growth inhibition, DNA damage, and cellular stress) and apoptotic effects, which are executed by different AMPK-dependent and -independent pathways (2, 4, 25, 32). In this context, nucleotide pool imbalance has been attributed as a cause of decreased transcription and replication stress via an AMPK-independent mechanism. However, we did not observe significant differences in histone gene transcript levels between short (<60 minutes) and long (24 hours) AICAR exposure conditions (Barredo and colleagues, unpublished data). Because both short (<60 minutes) and long (24 hours) AICAR exposure conditions yielded similar degrees of downregulation of histone gene expression, it is highly unlikely that nucleotide pool imbalance, growth inhibition, apoptosis, or cell-cycle arrest, contributed to the observed histone gene suppression under our experimental conditions. Our previously published data and those of others have shown that cell growth inhibition, cell death, or cell-cycle arrest require AMPK targeting for 24 hours or longer (2, 3, 5, 26, 32, 41, 42). Complementary, expression of direct regulators of histone gene transcription such as the Oct-1 coactivator OCA-S and the histone acetyltransferase 1 (HAT1) that have been shown to regulate S-phase–dependent histone H2B transcription and induce gene expression to enhance proliferation via histone modification, respectively (43, 44), could be altered under metabolic stress and/or regulated by AMPK that could lead to decrease histone expression. The role of AMPK on these histone transcription regulators needs to be addressed. We could speculate that, as histone proteins play a vital role in genome structural and functional regulation (gene transcription, DNA repair/recombination, chromosome segregation), AMPK might contribute to the previously reported effects of transcription downregulation and replication stress via regulation of histone gene transcription. Nonetheless, how AMPK is recruited to target gene loci and the detailed molecular composition of a putative chromatin-associated AMPK–protein(s) complex remains to be elucidated.

Our data establish a non-canonical function for AMPKα2, which phosphorylates TAF1 at S1353 in response to energy/metabolic stress, a highly conserved site critical for TAF1’s binding to chromatin (20, 21, 45). This is supported by: (i) decreased phosphorylation of the TAF1 S1353A by AMPKα2 compared with WT TAF1, and conversely greater phosphorylation of TAF1 WT compared with TAF1 S1353A mutant in cells expressing constitutively active (CA)-AMPKα2, and (ii) TAF1 phosphorylation at S1353 impaired the TAF1–Pol II interaction, as evidenced by the decreased interaction between the TAF1 S1353D mutant compared with WT TAF1. Our data showing impaired TAF1–Pol II interaction led to downregulation of histone genes’ expression, are consistent with TAF1’s role as transcription coactivator (16, 22). Alternatively, because TAF1 is capable of modifying/recognizing histones, the AMPK–TAF1 interaction might also modulate the underlying chromatin structure, leading to the observed changes in gene transcriptional changes under metabolic stress conditions. We have also identified additional AMPKα2 targets/partners, such as the PML and the NELFE. PML is known to play an important role in p53-dependent/p53-independent apoptosis (46), whereas NELFE represses Pol II transcription elongation (47), raising the possibility that PML and NELFE may similarly interact with AMPKα2, leading to adaptive transcriptome changes under energy/metabolic stress.

Mechanistically, we demonstrated that AMPKα2 interacts with TAF1 to regulate histone gene expression. Upon energy/metabolic stress, AMPKα2 phosphorylates TAF1 at S1353-impairing TAF1’s interaction with Pol II and leading to a compromised state of p-AMPKα2/p-TAF1/Pol II chromatin association and downregulation of histone gene transcription (Fig. 7, proposed model). As strong evidence for this model, AMPKα2 or/and TAF1 knockdown/knockout in ALL cells downregulated histone mRNA. To our knowledge, this non-canonical function of AMPK, which phosphorylates TAF1 to regulate histone gene expression in response to energy/metabolic stress, has not been previously described. Although this study primarily focused on AMPKα2, we also uncovered AMPKα1 localization in the nucleus of ALL cells, suggesting a similar role for AMPKα1 following its nuclear translocation. The latter is important because some ALL subtypes express low to “undetectable" levels of AMPKα2 (ref. 48; Barredo and colleagues, unpublished data). Importantly, the clinical relevance of our experimental model findings was confirmed in primary ALL patient cells and in vivo in NSG mice. Further elucidation of the physiological effects of AMPK's interactions with chromatin-associated proteins elicited by energy/metabolic stress will provide valuable biological insights and confirmation of the epigenetic role of AMPK.

Figure 7.

Proposed model for AMPK–TAF1–Pol II-mediated gene regulation in ALL cells in response to energy/metabolic stress. A, In normal condition, AMPKα2 interacts with TAF1, a member of a putative chromatin-associated transcription initiation complex, to regulate gene expression (e.g., histone genes). B, Under energy/metabolic stress, AMPK is activated and phosphorylates TAF1 at Ser-1353 site that impairs TAF1 interaction with RAP74 (subunit of TFIIF) and Pol II leading to decreased binding affinity of both p-AMPKα2 and p-TAF1 to the chromatin-associated transcription initiation complex. Alteration of the AMPK–TAF1–Pol II transcription initiation complex leads to gene downregulation.

In conclusion, herein we uncovered a novel non-canonical function of AMPKα2 that phosphorylates and regulates TAF1 function, both members of a putative chromatin-associated transcription complex to regulate histone gene expression, among others, inducing adaptive transcriptome changes in response to alterations in cellular energy status in ALL. Fully delineating the networks by which AMPK regulates adaptive responses to energy/metabolic stress, either via epigenetic or other mechanisms, will allow the rational development of strategies to overcome de novo or acquired resistance in ALL and possibly other cancers.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Methods

AMPKalpha2 binds to chromatin and co-localizes with RNA polymerase II (Pol II) on the TSS region of histone genes.

RNA Polymerase II occupancy on the TSS region of histone genes is decreased in Bp- and T-ALL cells in response to energy/metabolic stress.

AMPKalpha1 isoform is expressed in the cytoplasmic, nuclear, and chromatin-bound fractions of CN2 cells.

Phosphorylation of TAF1 at S1353 impairs regulation of histone gene expression.

TAF1 inhibition leads to cell growth inhibition and induction of apoptosis in ALL cells.

Chemicals used in this study.

Antibodies used in this study.

TaqMan RT-qPCR primers and probes used in this study.

Antibodies used for ChIP-seq/ChIP-qPCR assays in this study.

Primers for ChIP-qPCR used in this study.

Mass spectrometry analysis of putative TAF1 phosphorylated sites identified in HEK293T cells in response to energy/metabolic stress.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the library preparation and sequencing services provided by the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center (SCCC) Onco-Genomics Shared Resource. The authors thank the IVIS Small Animal Imaging Core Facility at the SCCC, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, for their help in the animal imaging with the optical Xenogen IVIS SPECTRUM system, and Dr. L. Fan (University of Miami) for helpful discussions. This research was supported by grants from the Batchelor Foundation and the Florida Biomedical Research Programs/Live Like Bella (# 20L09).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of publication fees. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This article is featured in Selected Articles from This Issue, p. 1249

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Molecular Cancer Research Online (http://mcr.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors' Disclosures

No disclosures were reported.

Authors' Contributions

G. Sun: Conceptualization, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft. G.J. Leclerc: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. S. Chahar: Resources, data curation, software, formal analysis, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. J.C. Barredo: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft, project administration, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Pui CH, Mullighan CG, Evans WE, Relling MV. Pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: where are we going and how do we get there? Blood 2012;120:1165–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sengupta TK, Leclerc GM, Hsieh-Kinser TT, Leclerc GJ, Singh I, Barredo JC. Cytotoxic effect of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-4-ribofuranoside (AICAR) on childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells: implication for targeted therapy. Mol Cancer 2007;6:46–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leclerc GM, Leclerc GJ, Kuznetsov JN, DeSalvo J, Barredo JC. Metformin induces apoptosis through AMPK-dependent inhibition of UPR signaling in ALL lymphoblasts. PLoS One 2013;8:e74420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kuznetsov JN, Leclerc GJ, Leclerc GM, Barredo JC. AMPK and Akt determine apoptotic cell death following perturbations of one-carbon metabolism by regulating ER stress in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mol Cancer Ther 2011;10:437–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leclerc GJ, DeSalvo J, Du J, Gao N, Leclerc GM, Lehrman MA, et al. Mcl-1 downregulation leads to the heightened sensitivity exhibited by BCR-ABL positive ALL to induction of energy and ER-stress. Leuk Res 2015;39:1246–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stapleton D, Mitchelhill KI, Gao G, Widmer J, Michell BJ, Teh T, et al. Mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase subfamily. J Biol Chem 1996;271:611–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thornton C, Snowden MA, Carling D. Identification of a novel AMP-activated protein kinase beta subunit isoform that is highly expressed in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 1998;273:12443–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: an energy sensor that regulates all aspects of cell function. Genes Dev 2011;25:1895–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim J, Yang G, Kim Y, Kim J, Ha J. AMPK activators: mechanisms of action and physiological activities. Exp Mol Med 2016;48:e224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chan LN, Chen Z, Braas D, Lee JW, Xiao G, Geng H, et al. Metabolic gatekeeper function of B-lymphoid transcription factors. Nature 2017;542:479–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bungard D, Fuerth BJ, Zeng PY, Faubert B, Maas NL, Viollet B, et al. Signaling kinase AMPK activates stress-promoted transcription via histone H2B phosphorylation. Science 2010;329:1201–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu D, Hu D, Chen H, Shi G, Fetahu IS, Wu F, et al. Glucose-regulated phosphorylation of TET2 by AMPK reveals a pathway linking diabetes to cancer. Nature 2018;559:637–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wan L, Xu K, Wei Y, Zhang J, Han T, Fry C, et al. Phosphorylation of EZH2 by AMPK suppresses PRC2 methyltransferase activity and oncogenic function. Mol Cell 2018;69:279–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 14. Zaborowska J, Taylor A, Roeder RG, Murphy S. A novel TBP-TAF complex on RNA polymerase II-transcribed snRNA genes. Transcription 2012;3:92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weinzierl RO, Dynlacht BD, Tjian R. Largest subunit of drosophila transcription factor IID directs assembly of a complex containing TBP and a coactivator. Nature 1993;362:511–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tavassoli P, Wafa LA, Cheng H, Zoubeidi A, Fazli L, Gleave M, et al. TAF1 differentially enhances androgen receptor transcriptional activity via its N-terminal kinase and ubiquitin-activating and -conjugating domains. Mol Endocrinol 2010;24:696–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dikstein R, Ruppert S, Tjian R. TAFII250 is a bipartite protein kinase that phosphorylates the base transcription factor RAP74. Cell 1996;84:781–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li HH, Li AG, Sheppard HM, Liu X. Phosphorylation on Thr-55 by TAF1 mediates degradation of p53: a role for TAF1 in cell G1 progression. Mol Cell 2004;13:867–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kloet SL, Whiting JL, Gafken P, Ranish J, Wang EH. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of cyclin D1 and cyclin A gene transcription by TFIID subunits TAF1 and TAF7. Mol Cell Biol 2012;32:3358–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jacobson RH, Ladurner AG, King DS, Tjian R. Structure and function of a human TAFII250 double bromodomain module. Science 2000;288:1422–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bhattacharya S, Lou X, Hwang P, Rajashankar KR, Wang X, Gustafsson JA, et al. Structural and functional insight into TAF1-TAF7, a subcomplex of transcription factor II D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:9103–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xu Y, Man N, Karl D, Martinez C, Liu F, Sun J, et al. TAF1 plays a critical role in AML1-ETO driven leukemogenesis. Nat Commun 2019;10:4925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lawrence M, Daujat S, Schneider R. Lateral thinking: how histone modifications regulate gene expression. Trends Genet 2016;32:42–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Armstrong C, Spencer SL. Replication-dependent histone biosynthesis is coupled to cell-cycle commitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2021;118:e2100178118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sun G, Shvab A, Leclerc GJ, Li B, Beckedorff F, Shiekhattar R, et al. Protein kinase D-dependent downregulation of immediate early genes through class IIA histone deacetylases in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mol Cancer Res 2021;19:1296–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. DeSalvo J, Kuznetsov JN, Du J, Leclerc GM, Leclerc GJ, Lampidis TJ, et al. Inhibition of Akt potentiates 2-DG-induced apoptosis via downregulation of UPR in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mol Cancer Res 2012;10:969–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zheng S, Leclerc GM, Li B, Swords RT, Barredo JC. Inhibition of the NEDD8 conjugation pathway induces calcium-dependent compensatory activation of the pro-survival MEK/ERK pathway in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncotarget 2018;9:5529–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yue J, Lai F, Beckedorff F, Zhang A, Pastori C, Shiekhattar R. Integrator orchestrates RAS/ERK1/2 signaling transcriptional programs. Genes Dev 2017;31:1809–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leclerc GM, Zheng S, Leclerc GJ, DeSalvo J, Swords RT, Barredo JC. The NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor pevonedistat activates the eIF2alpha and mTOR pathways inducing UPR-mediated cell death in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Res 2016;50:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 2009;4:44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang R, Grishagin I, Wang Y, Zhao T, Greene J, Obenauer JC, et al. The NCATS bioplanet—an integrated platform for exploring the universe of cellular signaling pathways for toxicology, systems biology, and chemical genomics. Front Pharmacol 2019;10:445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Du L, Yang F, Fang H, Sun H, Chen Y, Xu Y, et al. AICAr suppresses cell proliferation by inducing NTP and dNTP pool imbalances in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. FASEB J 2019;33:4525–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Obenauer JC, Cantley LC, Yaffe MB. Scansite 2.0: proteome-wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res 2003;31:3635–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang H, Curran EC, Hinds TR, Wang EH, Zheng N. Crystal structure of a TAF1-TAF7 complex in human transcription factor IID reveals a promoter binding module. Cell Res 2014;24:1433–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Patel AB, Greber BJ, Nogales E. Recent insights into the structure of TFIID, its assembly, and its binding to core promoter. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2020;61:17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhou L, Yao Q, Ma L, Li H, Chen J. TAF1 inhibitor Bay-299 induces cell death in acute myeloid leukemia. Transl Cancer Res 2021;10:5307–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Garcia Rubino ME, Carrillo E, Ruiz Alcala G, Dominguez-Martin A, A Marchal J, Boulaiz H. Phenformin as an anticancer agent: challenges and prospects. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vara-Ciruelos D, Dandapani M, Russell FM, Grzes KM, Atrih A, Foretz M, et al. Phenformin, but not metformin, delays development of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma via cell-autonomous AMPK activation. Cell Rep 2019;27:690–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jeon SM, Chandel NS, Hay N. AMPK regulates NADPH homeostasis to promote tumour cell survival during energy stress. Nature 2012;485:661–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kishton RJ, Barnes CE, Nichols AG, Cohen S, Gerriets VA, Siska PJ, et al. AMPK is essential to balance glycolysis and mitochondrial metabolism to control T-ALL cell stress and survival. Cell Metab 2016;23:649–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Campas C, Lopez JM, Santidrian AF, Barragan M, Bellosillo B, Colomer D, et al. Acadesine activates AMPK and induces apoptosis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells but not in T lymphocytes. Blood 2003;101:3674–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Santidrian AF, Gonzalez-Girones DM, Iglesias-Serret D, Coll-Mulet L, Cosialls AM, de Frias M, et al. AICAR induces apoptosis independently of AMPK and p53 through upregulation of the BH3-only proteins BIM and NOXA in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Blood 2010;116:3023–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zheng L, Roeder RG, Luo Y. S phase activation of the histone H2B promoter by OCA-S, a coactivator complex that contains GAPDH as a key component. Cell 2003;114:255–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gruber JJ, Geller B, Lipchik AM, Chen J, Salahudeen AA, Ram AN, et al. HAT1 coordinates histone production and acetylation via H4 promoter binding. Mol Cell 2019;75:711–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Curran EC, Wang H, Hinds TR, Zheng N, Wang EH. Zinc knuckle of TAF1 is a DNA binding module critical for TFIID promoter occupancy. Sci Rep 2018;8:4630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bernardi R, Pandolfi PP. Structure, dynamics, and functions of promyelocytic leukaemia nuclear bodies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007;8:1006–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yamaguchi Y, Inukai N, Narita T, Wada T, Handa H. Evidence that negative elongation factor represses transcription elongation through binding to a DRB sensitivity-inducing factor/RNA polymerase II complex and RNA. Mol Cell Biol 2002;22:2918–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, et al. The cancer cell line encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature 2012;483:603–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Methods

AMPKalpha2 binds to chromatin and co-localizes with RNA polymerase II (Pol II) on the TSS region of histone genes.

RNA Polymerase II occupancy on the TSS region of histone genes is decreased in Bp- and T-ALL cells in response to energy/metabolic stress.

AMPKalpha1 isoform is expressed in the cytoplasmic, nuclear, and chromatin-bound fractions of CN2 cells.

Phosphorylation of TAF1 at S1353 impairs regulation of histone gene expression.

TAF1 inhibition leads to cell growth inhibition and induction of apoptosis in ALL cells.

Chemicals used in this study.

Antibodies used in this study.

TaqMan RT-qPCR primers and probes used in this study.

Antibodies used for ChIP-seq/ChIP-qPCR assays in this study.

Primers for ChIP-qPCR used in this study.

Mass spectrometry analysis of putative TAF1 phosphorylated sites identified in HEK293T cells in response to energy/metabolic stress.