Abstract

Aim:

Patients with polycythemia vera (PV), a rare and chronic blood cancer, are at a higher risk for thromboembolic events, progression to myelofibrosis, and leukemic transformation. In 2021, ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft (BESREMi®) was approved in the US to treat adults with PV. The purpose of this study is to estimate the cost–effectiveness of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft, used as a first- or second-line treatment, for the treatment of patients with PV in the US.

Materials & methods:

A Markov cohort model was developed from the healthcare system perspective in the United States. Model inputs were informed by the PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV studies and published literature. The model population included both low-risk and high-risk patients with PV. The model compared ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft used either as first- or second-line versus an alternative treatment pathway of first-line hydroxyurea followed by ruxolitinib.

Results:

Over the modeled lifetime, ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft provided an additional 0.4 higher quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and 0.4 life-years with an added cost of USD60,175, resulting in a cost per QALY of USD141,783. The model was sensitive to treatment costs, the percentage of patients who discontinue hydroxyurea, the percentage of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft users who switch to monthly dosing, the percentage of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft users as 2nd line treatment, and the treatment response rates. A younger patient age at baseline and a higher percentage of patients with low-risk disease improved the cost–effectiveness of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft.

Conclusion:

Ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft is a cost-effective treatment option for a broad range of patients with PV, including both low- and high-risk patients and patients with and without prior cytoreductive treatment with hydroxyurea.

Keywords: cost–effectiveness, polycythemia vera, ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft

Plain language summary

What is the article about?

This research analyzed the costs and benefits of a therapy called ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft used to treat patients with polycythemia vera (PV), which is a rare type of blood cancer.

How was the research carried out?

A model was created that compared ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft used either as the first or second therapy option for patients with PV versus an alternative treatment pathway without ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft. The data from randomized clinical trials and from real-world sources were included. The model followed patients from treatment initiation through their lifetime and tracked blood clot events and disease progression. Patients who experienced blood clots or disease progression had higher risk of death, higher healthcare costs, and lower health-related quality of life. The lifetime total costs, years alive, and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were compared between the alternative treatment pathways.

What were the results?

Over a lifetime, the model showed that patients who received ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft had more years alive (0.4), and higher QALYs (0.4), and higher cost (USD60,175). Weighing the additional costs versus the additional QALY gains results in a cost per QALY of USD141,783.

What do the results mean?

The results suggest the benefits of treatment with ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft outweigh the costs for a broad range of patients with PV.

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a rare, chronic, and life-threatening blood cancer and type of myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) that affects approximately 160,000 people in the US [1]. PV occurs when hematopoietic progenitor cells acquire somatic mutations, primarily JAK2 V617F, leading to proliferation and an excess of myeloid blood cells [2,3]. Patients with PV are at risk for disease progression to myelofibrosis (post-PV MF) or transformation to blast phase (MPN-BP) which is akin to acute myeloid leukemia [4–6], both of which are associated with poor prognosis. Within 10 years of diagnosis, an estimated 10% of patients with PV progress to post-PV MF and 2–9% experience leukemic transformation to MPN-BP [4,7]. In patients with MPNs whose disease undergoes leukemic transformation, a median survival of 3.6 months is expected [8].

In addition to the risk of progression, patients with PV are at an increased risk for arterial and venous thromboembolic events (TEs) which are associated with higher mortality, lower quality of life, and higher healthcare costs [9–12]. Real-world data from a large, prospective registry of patients with PV in the US reported a 4-year mortality rate over 10% with approximately a third of deaths due to thrombotic complications [13]. In a retrospective analysis of US claims data, healthcare costs for patients with PV were three- to four-times higher among patients who experienced a TE versus those who did not [12]. Treatment guidelines have focused on regular monitoring of blood counts to reduce the risk of thrombosis as well as symptom management through the use of aspirin and phlebotomies, and for some patients, cytoreductive therapy [14].

For patients with PV who are at low risk for TEs – those under 60 years of age and no prior thrombosis – regular phlebotomies with aspirin alone may be sufficient to manage disease. However, phlebotomies may not maintain the target hematocrit levels of <45% associated with lower risk of TEs, and frequent phlebotomies can negatively impact patients' quality of life. Patient-reported symptom burden has been reported to persist despite control of blood counts, including symptoms that may be due to iron deficiency [15,16]. Furthermore, younger patients with PV, who are often classified as low-risk and not routinely treated with cytoreductive therapies, remain at higher risk of mortality compared with the general population [17].

For high-risk patients and those who are not managed well with aspirin and phlebotomy alone, cytoreductive therapy may be given, which is often hydroxyurea (HU) although it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of PV. However, patients treated with HU may continue to need regular phlebotomies and remain at risk for TEs. Among patients treated with HU, the 3-year risk of TE is higher among those with 3 or more phlebotomies per year versus 0–2 phlebotomies per year (20.5 vs 5.3%) [18], although this relationship has not been confirmed in randomized clinical trials [19]. In addition, resistance and intolerance to HU has been documented in 11% and 13% of patients and is associated with higher risk of disease progression and death [20]. For adults who have had an inadequate response to or are intolerant of HU, ruxolitinib (RUX) may be considered as a treatment option [21].

In 2022, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) updated their treatment guidelines to include ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft (BESREMi®) as a treatment option for patients with both low- and high-risk PV [14], and in 2023, the NCCN updated the guidelines to indicate that ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft is a preferred treatment regimen for both low- and high-risk PV [22]. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft is a purposely-designed, monopegylated, long-acting interferon that was approved by the US FDA in November 2021 for the treatment of adults with PV [23]. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft has demonstrated safety and efficacy in studies including both low- and high-risk patients and patients with and without prior cytoreductive treatment with HU [24–26]. In the Phase 3, randomized, controlled, open-label study PROUD-PV and its expansion study, CONTINUATION-PV, ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft demonstrated high rates of CHR and higher hematologic and molecular responses compared with treatment with HU observed starting after 2 years of treatment [26,27]. After 3 years of treatment, 67 of 95 (71%) patients who received ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft achieved CHR versus 38 of 74 (51%) patients who received HU [26,27]. Molecular response after 3 years based on JAK2 allele burden was 66% versus 27% for patients who received ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft and HU, respectively [26,27].

PV is a chronic blood cancer that requires lifelong therapy which can prevent or delay negative clinical outcomes but is also associated with additional costs to payers and patients. Therefore, it is important to assess the value of any new treatments that are introduced to understand the relative benefits and costs. The purpose of this study is to estimate the cost–effectiveness of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft, used as a first- or second-line treatment, for the treatment of patients with PV in the US based on the evidence from the PROUD/CONTINUATION-PV studies.

Methods

Overview & structure

A Markov cohort model was developed (Figure 1) with six health states to estimate the cost–effectiveness of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft used as first- or second-line treatment for patients with PV from the perspective of the US healthcare system. Results were presented over a lifetime horizon to reflect the long-term consequences of treating PV. The model used one-year cycles, and costs and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were discounted at 3% per year. The model was developed using Microsoft Excel 2016 (WA, USA).

Figure 1. . Model Structure.

CHR: Complete hematologic response; MF: Myelofibrosis; MPN-BP: Myeloproliferative neoplasms in blast phase; PV: Polycythemia vera; TE: Thromboembolic event; 1L: First-line; 2L: Second-line; 3L: Third-line.

The model compared ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft used either as first- or second-line versus an alternative treatment pathway of first-line HU followed by RUX (HU/RUX). The comparator of HU followed by RUX was selected in order to reflect clinical practice guidelines and RUX's labeled indication for the treatment of PV in adults who have had an inadequate response to or are intolerant of HU [14,21]. Patients receiving ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft followed a treatment pathway of either (a) first-line ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft followed by HU and finally RUX (ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft/HU/RUX) or (b) first-line HU followed by ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft and then RUX (HU/ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft/RUX). Based on the baseline patient characteristics from the PROUD-PV trial, 65% of the patients in the ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft cohort followed the ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft/HU/RUX treatment pathway and 35% followed the HU/ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft/RUX treatment pathway in this model [26].

Patients entered the model on their initial treatment and without complete hematologic response (CHR). During every year in the model, a proportion of patients discontinue their initial treatment and are switched to their next line of treatment. In addition, a proportion of patients experienced a TE each year, and those who recovered moved to the Post-TE health state. Patients on treatment, including those who have experienced a TE, were at risk for progression to post-PV MF or transformation to MPN-BP. Patients with post-PV MF were also at risk for MPN-BP. The patients who progressed to post-PV MF or MPN-BP discontinued their PV treatment, and it was assumed that they subsequently received treatment for post-PV MF or MPN-BP, respectively. At any time in the model, a proportion of patients on treatment achieved CHR. These patients were at lower risk for progression to post-PV MF but otherwise followed the same clinical course as patients who did not achieve CHR. Patients could transition to death from any health state.

Population

The model population was comprised of 22.7% low-risk and 77.3% high-risk patients with PV based on the baseline characteristics from a large, prospective registry of patients with PV in the US [28]. Patients in the low-risk group were assumed to start in the model at age 49.7 years based on the population in the LOW-PV study [24] and patients in the high-risk group were assumed to start in the model at age 60 years based on the definition of high risk. Given these characteristics, the starting age for the cohort entering the model was 58 years. It was assumed that 61% of the model population required 8 phlebotomies per year at baseline, which was reflective of the PEGINVERA study [25].

Clinical inputs

The probability of achieving CHR for ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft and HU was based on the CHR rates observed in PROUD/CONTINUATION-PV [26]. For RUX, the CHR rates were taken from the RESPONSE trial [29]. Twenty four percent of patients had complete hematological remission at week 32, which was used for the year 1 CHR rate in the model, and 38% of these patients were reported to progress after 5 years. The model assumed a constant decline in response between year 1 and year 5. For all treatments, the year 5 CHR rates were carried forward for the remainder of the model time horizon.

The annual risk for a first TE while undergoing treatment with ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft (1.0%) and HU (1.2%) was based on 5-year results from PROUD/CONTINUATION-PV [27]. The annual risk for a 1st TE for treatment with RUX (3.1%) was based on a meta-analysis of RUX studies [30]. After the first TE, patients were at a higher risk for experiencing a subsequent TE, which was applied to the treatment-specific TE risks [31]. The additional TE risk remained constant for the remainder of the model time horizon, irrespective of the number of TEs.

The risk of post-PV MF was time-dependent based on a recent analysis of US data [32], patients with post-PV MF were at a constant risk for transformation to MPN-BP [5]. For patients who achieved CHR, the risk of progression to post-PV MF was 61% lower based on a recent publication estimating the impact of achieving CHR [31,32]. The risk for transformation to MPN-BP was constant based on a recent meta-analysis of outcomes among patients on HU which did not indicate that the risk of MPN-BP changed over time [5].

The model incorporated age-specific background mortality with additional mortality risks for TE (relative risk vs no TE), post-PV MF, and MPN-BP [5,8,11]. Based on recent evidence that suggested life expectancy for patients with PV can be similar to the general population [32], the base-case model assumed the background mortality for patients with PV was the same as the general population. The base-case model included a higher risk of mortality among patients who experienced TEs. However, given the improvements in treatment and management of TEs, a scenario analysis explored the effect of no excess mortality after patients experience TEs.

The annual discontinuation rates for ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft and HU were 16.5% and 12.6% respectively, as reported in PROUD/CONTINUATION-PV [26]. The model assumed that treatment discontinuation did not depend on current line of treatment, treatment history, or risk stratification based on the lack of data to suggest otherwise. Based on clinical guidelines, RUX was considered a last-line treatment and as such, the model did not allow patients to discontinue RUX once they received RUX in the treatment pathway.

Cost inputs & resource use

The wholesale acquisition costs (WAC) of the treatments were taken from RedBook [33]. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft was assumed to be self-administered every two weeks by subcutaneous injection. The initial treatment with ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft included a one-time cost for training and administering treatment, using HCPCS Code 96372 to estimate physician fee costs [34]. Based on ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft's product label [23], patients on ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft who achieved CHR for a model cycle (1 year) subsequently switched to a monthly dosing schedule. For HU, dosing was assumed to be 2,000 mg daily. RUX was assumed to be administered 10 mg twice daily [21].

In addition to treatment costs, patients who did not achieve a CHR were assumed to have 8 phlebotomies per year based on the results of the PEGINVERA trial where patients received a median of 2 phlebotomies in the 3 months prior to PV screening [25]. The cost of phlebotomy was estimated using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Physician Fee Schedule for 2022.

The annual cost of TE, both the first and recurrent, reflected the total cost of management from a payer perspective. It was assumed that the post-TE annual costs were equivalent to the TE annual costs, which were incurred for the remainder of the model time horizon or until death [12]. The annual costs of post-PV MF and MPN-BP were based on US claims analyses [35]. All costs were adjusted to USD 2022 using the Medical CPI.

Utility inputs

The base health state utilities reflected age-specific US population norms using EuroQol 5-Dimension 5-Level (EQ-5D-5L) [36]. A disutility of -0.117 was applied to patients on treatment who did not achieve CHR [37]. Given the lack of data, no utility decrement was applied to patients who received a phlebotomy and as discussed, is a limitation to this study. This assumption was explored in a scenario analysis using a decrement of -0.0003 based on data coming from a recent study assessing quality of life related to infusions administered to patients with hemophilia A [38]. Patients with a TE were given a disutility of -0.038 in the cycle when the TE occurred [39] and patients with post-PV MF were given a disutility of -0.152 [37].

Analyses

Results were expressed in terms of total and incremental costs, life-years, and QALYs. The incremental cost–effectiveness ratio (ICER), calculated as the difference in total costs divided by the difference in QALYs, was compared with a threshold of USD150k/QALY to determine the cost–effectiveness of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft.

As noted above, two scenario analyses were explored: one where there is no added risk for death from TE (i.e., relative risk of death from TE = 1), and a second additional scenario analysis using a disutility of -0.0003 for phlebotomies. One-way sensitivity analyses varied the input parameters by +/- 20%. To facilitate the interpretation of results from the one-way sensitivity analysis, the net monetary benefit (NMB) was reported using a willingness to pay (WTP) threshold of USD150k/QALY [40]. NMB was calculated as , where Δ signifies the difference between the ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft and comparator. A positive NMB implies that ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft was cost-effective at the WTP threshold. In addition, probabilistic sensitivity analyses varying all input parameters simultaneously were conducted using 5,000 samples. Probability distributions and the range of sampled values from the probabilistic sensitivity analyses were included in Table 1.

Table 1. . Model inputs.

| Input |

Base-case value |

Distribution for PSA |

Range of sampled values from PSA |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population characteristics | ||||

| Population characteristics | ||||

| Starting age (years) |

58 |

Normal (μ = 57.6, σ = 5.8) |

32–82 |

|

| Cohort – low risk |

22.7% |

– |

Not varied |

[28] |

| Cohort – high risk |

77.3% |

– |

Not varied |

[28] |

| Requiring phlebotomies |

61% |

Beta (α = 32, β = 21) |

36–79% |

[25] |

| Phlebotomies per year | 8 | Normal (μ = 8, σ = 0.8) | 5–11 | [25] |

| Clinical inputs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual discontinuation – ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft |

16.5% |

Beta (α = 22, β = 107) |

8–31% |

[26] |

| Annual discontinuation – HU |

12.6% |

Beta (α = 17, β = 112) |

5–25% |

[26] |

| CHR rates – ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft |

Year 1: 62% Year 2: 71% Year 3: 71% Year 4: 61% Year 5: 56% |

Beta (α = 60, β = 37) Beta (α = 68, β = 29) Beta (α = 68, β = 29) Beta (α = 58, β = 38) Beta (α = 54, β = 43) |

44–77% 48–85% 47–84% 42–78% 38–74% |

[26] |

| CHR rates – HU |

Year 1: 75% Year 2: 49% Year 3: 51% Year 4: 45% Year 5: 44% |

Beta (α = 58, β = 20) Beta (α = 34, β = 35) Beta (α = 39, β = 37) Beta (α = 35, β = 43) Beta (α = 34, β = 43) |

56–89% 28–69% 30–70% 26–64% 26–67% |

[26] |

| CHR rates – RUX |

Year 1: 24% Year 2: 22% Year 3: 20% Year 4: 18% Year 5: 15% |

Uniform (0.19, 0.29) Uniform (0.17, 0.22) Uniform (0.16, 0.24) Uniform (0.14, 0.22) Uniform (0.12, 0.18) |

19–29% 17–26% 16–24% 14–22% 12–18% |

[29] |

| Annual risk for first TE – ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft |

1.0% |

Uniform (0.008, 0.012) |

0.8–1.2% |

[27] |

| Annual risk for first TE – HU |

1.2% |

Uniform (0.010, 0.014) |

1.0–1.4% |

[27] |

| Annual risk for first TE – RUX |

3.1% |

Uniform (0.025, 0.037) |

2.5–3.7% |

[30] |

| RR, subsequent TE |

2.67 |

Log Normal (μ = 0.98, σ = 0.1) |

1.88–3.90 |

[31] |

| Risk of post-PV MF |

Year 0–4: 0.4% Year 4–8: 1.2% Year 8–12: 1.8% Year 12–16: 2.5% Year 16–20: 3.9% Year 20–24: 2.4% Year 24+: 4.8% |

Log Normal (μ = -5.5, σ = 0.1) Log Normal (μ = -4.5, σ = 0.1) Log Normal (μ = -4.0, σ = 0.1) Log Normal (μ = -3.7, σ = 0.1) Log Normal (μ = -3.3, σ = 0.1) Log Normal (μ = -3.7, σ = 0.1) Log Normal (μ = -3.0, σ = 0.1) |

0.3–0.6% 0.8–1.6% 1.3–2.5% 1.7–3.5% 2.6–5.5% 1.6–3.4% 3.5–6.9% |

[32] |

| RR of post-PV MF, CHR vs no CHR |

0.39 |

Log Normal (μ = -0.9, σ = 0.1) |

0.27–0.54 |

[31] |

| MPN-BP annual risk |

0.4% |

Log Normal (μ = -5.5, σ = 0.1) |

0.3–0.6% |

[41] |

| Annual risk of post-PV MF to MPN-BP |

3.1% |

Log Normal (μ = -3.5, σ = 0.1) |

2.1–4.4% |

[5] |

| RR, Mortality from TE (vs no TE) |

1.93 |

Log Normal (μ = 0.66, σ = 0.05) |

1.57–2.30 |

[11] |

| Annual risk of mortality from post-PV MF |

14.6% |

Log Normal (μ = -1.9, σ = 0.05) |

12–18% |

[5] |

| Annual risk of mortality from MPN-BP | 80% | Log Normal (μ = -0.2, σ = 0.05) | 66–95% | [8] |

| Cost inputs (annual) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft |

$195,182 |

Gamma (α = 100, β = 1951.8) |

$132,307–270,103 |

[33] |

| HU |

$1,090 |

Gamma (α = 100, β = 10.9) |

$767–1,492 |

[33] |

| RUX |

$203,013 |

Gamma (α = 100, β = 2030.1) |

$138,611–278,498 |

[33] |

| No CHR |

$511 |

Gamma (α = 100, β = 5.1) |

$355–740 |

|

| TE (first and recurrent) |

$34,858 |

Gamma (α = 100, β = 348.6) |

$23,287–48,062 |

[12] |

| Post-PV MF |

$105,280 |

Gamma (α = 100, β = 1052.8) |

$72,056–$144,477 |

[35] |

| MPN-BP | $280,236 | Gamma (α = 100, β = 2802.4) | $192,274–$379,741 | [42] |

| HRQoL inputs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CHR |

-0.117 |

Uniform (-0.14, -0.09) |

-0.14–-0.09 |

[37] |

| TE |

-0.038 |

Uniform (-0.05, -0.03) |

-0.05–-0.03 |

[39] |

| Post-PV MF |

-0.152 |

Uniform (-0.18, -0.12) |

-0.18–-0.12 |

[37] |

| MPN-BP | 0.53 | Uniform (0.42, 0.64) | 0.42–0.64 | [43] |

CHR: Complete hematologic response; HU: Hydroxyurea; MF: Myelofibrosis; MPN-BP: Myeloproliferative neoplasms in blast phase; PSA: Probabilistic sensitivity analyses; PV: Polycythemia vera; RR: Relative risk; RUX: Ruxolitinib; TE: Thromboembolic events.

Result

Base case results for PV population

The base case cost–effectiveness results are shown in Table 2 below. Over a lifetime time horizon, the total costs of treatment with HU/RUX were USD1,873,157 and USD1,933,332 for treatment with ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft when 65% of the ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft cohort used ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft as first-line and 35% as second-line, a difference of USD60,175. The total QALYs for HU/RUX were 14.8 and 15.2 for ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft, resulting in a gain of 0.4 incremental QALYs when treating with ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft. Total life years with HU/RUX were 21.2, and 21.5 with ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft, an incremental gain of 0.4 LYs. The incremental cost–effectiveness ratio (ICER) was USD141,783 indicating that ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft was a cost-effective treatment option at a standard willingness to pay threshold of USD150 k/QALY.

Table 2. . Base case results.

| HU/RUX | 1st- or 2nd-line ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime total costs | $1,873,157 | $1,933,332 | $60,175 |

| Total QALYs | 14.8 | 15.2 | 0.4 |

| Total LYs | 21.2 | 21.5 | 0.4 |

| ICER | $141,783 |

HU: Hydroxyurea; ICER: Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; LY: life year; QALY: Quality-adjust life year.

Scenario & sensitivity analyses

Ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft remained cost-effective in the two scenario analyses that were explored. In a scenario analysis where there is no added risk for death from TE (i.e., relative risk of death from TE = 1), the ICER was USD132,954. In a second additional scenario analysis, a disutility of -0.0003 was included for each phlebotomy, and the resulting ICER was USD141,309.

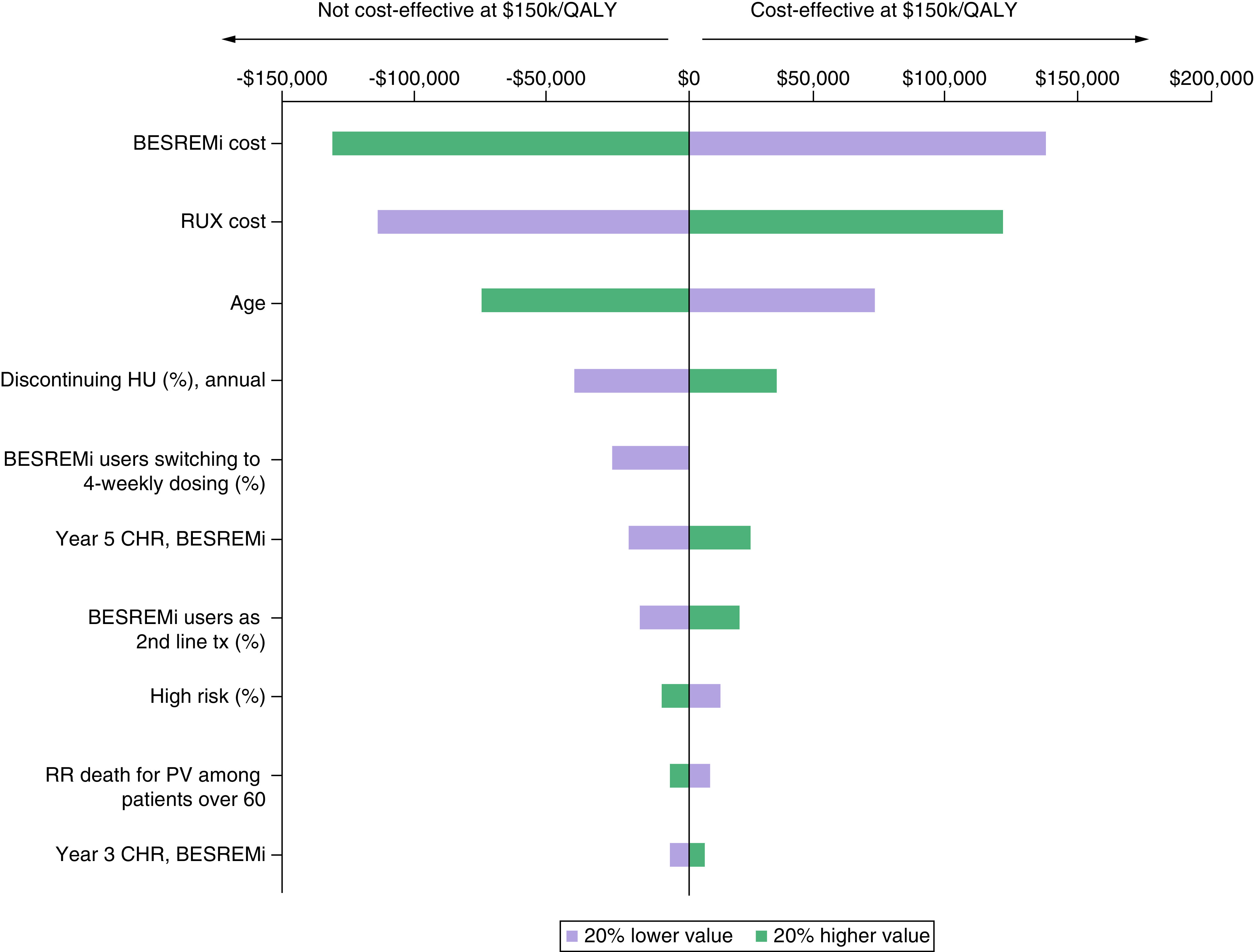

Based on one-way sensitivity analyses that varied key input parameters by ±20%, the model was most sensitive to the cost of treatment with ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft or RUX (Figure 2). Treatment characteristics including the percentage of patients who discontinue HU, the percentage of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft users who switch to monthly dosing, the percentage of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft users as 2nd line treatment, and the CHR response were also influential in the model. In terms of patient characteristics, a younger patient age at baseline and a higher percentage of patients with low-risk disease improved the cost–effectiveness of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft. Results from the probabilistic sensitivity analysis suggest that treatment with ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft was more effective (i.e., higher QALYs) in all simulations. ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft was found to be dominant (i.e., higher QALYs and lower costs) in 19% of simulations and cost-effective in a further 18% of simulations (Appendix).

Figure 2. . One-way sensitivity analysis applied to the economic model base case (top 10 most influential parameters).

CHR: Complete hematologic response; HU: Hydroxyurea; PV: Polycythemia vera; QALY: Quality-adjust life year; RR: Relative risk; RUX: Ruxolitinib.

Discussion

The results of the cost–effectiveness analysis demonstrated the clinical and economic value of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft used as first- or second-line treatment for patients with PV. Extended treatment with ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft is associated with higher rates of CHR compared with HU as seen in CONTINUATION-PV [26], such that over a modeled lifetime, patients receiving ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft experienced gains in life expectancy and QALYs. These benefits offset the additional costs, such that ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft was shown to be a cost-effective treatment option over the modeled lifetime.

In our analysis, treating patients at a younger age led to more cost-effective results, suggesting that earlier initiation of treatment of PV with effective therapy can translate to more favorable cost to benefit ratios. By treating patients earlier, more severe and costly events can be avoided. Additionally in our analysis, a cohort with a higher percentage of low-risk patients led to more cost-effective results. In PROUD/CONTINUATION-PV, patients with low-risk PV achieved higher CHR rates than patients with high-risk disease, indicating that low-risk patients may have greater potential benefit when receiving ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft [44]. In addition, findings from a recently published, open-label, randomized study of 127 low-risk PV patients indicate that the benefits of ropeginterferon-alfa-2b-njft added to phlebotomy + aspirin were sustained over 24 months, consistent with the results at 12 months from randomization, which was the primary end point period [45]. Low-risk patients are typically younger than high-risk patients, but growing evidence indicates the need for treatments that inhibit disease progression even among younger patients and those presenting with lower-risk disease. In a contemporary cohort of 630 patients with MPNs evaluated at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institution, pediatric and young adults were at higher risk of TE compared with older adults, and these younger patients remain at risk for disease progression and transformation [46]. Twenty four percent of pediatric and young adults with PV progressed to post-PV MF after a mean of 24 years and 4% transformed to MPN-BP after a mean of 28 years. A separate analysis of MPN patients in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-18 database reported that excessive all-cause mortality was significantly higher in patients with PV under 60 years compared with over 60 years (3.16 vs 1.92) [17]. These data indicate the risk of progression and death in younger patients with PV remains high, and that these patients may be affected by undertreatment.

There are a few key limitations of the study. The full benefits of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft may not be fully captured in the model, and in particular, data on disutility of phlebotomy are lacking. Although some patients may tolerate regular phlebotomies, others can experience iron deficiency which can negatively impact quality of life. While the results from a scenario analysis incorporating a small decrement in utility had minimal impact on the cost–effectiveness results, due to the lack of data in this area, this estimate remains conservative. The indirect costs such as time and productivity loss are not accounted for when considering the frequency of phlebotomies. Future studies assessing the impact of phlebotomies on patients with PV could provide more robust evidence-based estimates. Long-term durability of response data are limited, and the model assumed the 5-year results held for the remainder of the model. As the response rate for HU declined more quickly during the 5-year observation period than for ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft in PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV, the model may underestimate the full benefits of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft. In addition, the model considered RUX as a last line treatment based on clinical guidelines, and as such, the model did not allow patients to discontinue RUX once they received RUX in any of the treatment pathways. Clinical practice may differ from guidelines and in a real-world setting, patients who are resistant to or intolerant of HU discontinued treatment with RUX after a median of 29–35 months [47]. This study took a US healthcare perspective and the results may not generalize to other countries given the differences in healthcare resource use, costs, and cost–effectiveness thresholds between countries. Finally, the clinical trials for PV treatments, including PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV, are not powered to show differences in disease progression. The data informing the relationship between CHR and post-PV MF used in this model come from a recent analysis of real-world data that was not specific to a treatment. Although the model was not sensitive to changes in this estimate, future studies assessing this relationship would strengthen the evidence.

Conclusion

When used as either a first- or second-line therapy long-term in the CONTINUATION-PV study, ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft demonstrated improved CHR compared with HU [26]. Based on these data, the results from the current economic model demonstrated that patients treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft had longer life expectancy and accrued more QALYs over a lifetime. These results suggest that ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft is a cost-effective treatment option for a broad range of patients with PV, including both low- and high-risk patients and patients with and without prior cytoreductive treatment with HU.

Summary points

Patients with polycythemia vera (PV) are at risk for thromboembolic events and disease progression to myelofibrosis or transformation to blast phase, which are associated with higher mortality, lower quality of life, and higher healthcare costs.

Ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft is a preferred treatment regimen for both low- and high-risk PV and has demonstrated higher hematologic and molecular responses compared with treatment with hydroxyurea (HU) observed starting after two years of treatment.

The current study evaluated the cost–effectiveness of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft versus HU for treating patients with PV in the US.

A Markov cohort model was developed using inputs informed by the PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV studies and published literature.

The model compared ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft used either as first- or second-line versus an alternative treatment pathway of first-line hydroxyurea followed by ruxolitinib.

Over the modeled lifetime, ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft provided an additional 0.4 higher quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and 0.4 life-years with an added cost of USD60,175, resulting in a cost per QALY of USD141,783.

A younger patient age at baseline and a higher percentage of patients with low-risk disease improved the cost–effectiveness of ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft. ICER.

Ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft is a cost-effective treatment option for a broad range of patients with PV, including both low- and high-risk patients and patients with and without prior cytoreductive treatment with HU.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge R Arguello from Stratevi LLC for his medical writing contributions in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: https://bpl-prod.literatumonline.com/doi/10.57264/cer-2023-0066

Author contributions

Authors AG Ellis, C Castro, MM Flynn, M Manning, R Urbanski were responsible for study conception and design; author AG Ellis was responsible for the model development and analysis; all authors contributed to the interpretation of results and the drafting and revision of the manuscript.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This study was funded by PharmaEssentia Corporation. AG declares consultation for PharmaEssentia, GSK/Sierra Oncology, BMS/Celgene, Incyte, Kartos/Telios, Incyte, Novartis, AbbVie, Merk/Imago Biosciences. C Castro, F Snopek, MM Flynn, M Manning, R Urbanski are employees of PharmaEssentia USA Corporation. AG Ellis is an employee of Stratevi LLC, which received consulting fees for conducting this work. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Medical writing support was provided by Stratevi LLC and was funded by PharmaEssentia Corporation.

Open access

This work is licensed under the Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Mehta J, Wang H, Iqbal SU, Mesa R. Epidemiology of myeloproliferative neoplasms in the United States. Leuk. Lymphoma 55(3), 595–600 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boissinot M, Vilaine M, Hermouet S. The hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/Met axis: a neglected target in the treatment of chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms? Cancers (Basel) 6(3), 1631–1669 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galan-Diez M, Cuesta-Dominguez A, Kousteni S. The bone marrow microenvironment in health and myeloid malignancy. Cold Spring. Harb. Perspect. Med. 8(7),a031328 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKinnell Z, Karel D, Tuerff D, Sh Abrahim M, Nassereddine S. Acute myeloid leukemia following myeloproliferative neoplasms: a review of what we know, what we do not know, and emerging treatment strategies. J Hematol. 11(6), 197–209 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masarova L, Bose P, Daver N et al. Patients with post-essential thrombocythemia and post-polycythemia vera differ from patients with primary myelofibrosis. Leuk. Res. 59, 110–116 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finazzi G, Caruso V, Marchioli R et al. Acute leukemia in polycythemia vera: an analysis of 1638 patients enrolled in a prospective observational study. Blood 105(7), 2664–2670 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tefferi A. Essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, and myelofibrosis: current management and the prospect of targeted therapy. Am. J. Hematol. 83(6), 491–497 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tefferi A, Mudireddy M, Mannelli F et al. Blast phase myeloproliferative neoplasm: mayo-AGIMM study of 410 patients from two separate cohorts. Leukemia 32(5), 1200–1210 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griesshammer M, Kiladjian JJ, Besses C. Thromboembolic events in polycythemia vera. Ann. Hematol. 98(5), 1071–1082 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tefferi A, Rumi E, Finazzi G et al. Survival and prognosis among 1545 patients with contemporary polycythemia vera: an international study. Leukemia 27(9), 1874–1881 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Landolfi R et al. Vascular and neoplastic risk in a large cohort of patients with polycythemia vera. J. Clin. Oncol. 23(10), 2224–2232 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parasuraman SV, Shi N, Paranagama DC, Bonafede M. Health care costs and thromboembolic events in hydroxyurea-treated patients with polycythemia vera. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 24(1), 47–55 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein BL, Patel K, Scherber RM, Yu J, Paranagama D, Miller CB. 484 Mortality and Causes of Death of Patients with Polycythemia Vera: Analysis of the Reveal Prospective, Observational Study. In: 62nd ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition. (American Society of Hematology; (December 6, 2020). (Virtual). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerds AT, Gotlib J, Ali H et al. Myeloproliferative Neoplasms, Version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl Compr. Canc. Netw. 20(9), 1033–1062 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grunwald MR, Burke JM, Kuter DJ et al. Symptom Burden and Blood Counts in Patients With Polycythemia Vera in the United States: An Analysis From the REVEAL Study. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 19(9), 579–584.e1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scherber RM, Geyer HL, Dueck AC et al. The potential role of hematocrit control on symptom burden among polycythemia vera patients: insights from the CYTO-PV and MPN-SAF patient cohorts. Leuk. Lymphoma 58(6), 1481–1487 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abu-Zeinah K, Saadeh K, Silver RT, Scandura JM, Abu-Zeinah G. Excess mortality in younger patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leuk. Lymphoma 64(3), 725–729 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvarez-Larran A, Perez-Encinas M, Ferrer-Marin F et al. Risk of thrombosis according to need of phlebotomies in patients with polycythemia vera treated with hydroxyurea. Haematologica 102(1), 103–109 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barbui T, Carobbio A, Ghirardi A, Masciulli A, Rambaldi A, Vannucchi AM. No correlation of intensity of phlebotomy regimen with risk of thrombosis in polycythemia vera: evidence from European Collaboration on Low-Dose Aspirin in Polycythemia Vera and Cytoreductive Therapy in Polycythemia Vera clinical trials. Haematologica 102(6), e219–e221 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvarez-Larran A, Pereira A, Cervantes F et al. Assessment and prognostic value of the European LeukemiaNet criteria for clinicohematologic response, resistance, and intolerance to hydroxyurea in polycythemia vera. Blood 119(6), 1363–1369 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Food and Drug Administration. Jakafi (ruxolitinib) Package Insert (2011). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/202192lbl.pdf

- 22.Gerds AT, Gotlib J, Abdelmessieh P et al. Myeloproliferative Neoplasms, Version 1.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. In: NCCN Guidelines. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; (2023). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mpn.pdf [Google Scholar]; • This document describes the clinical guidelines for the management of myeloproliferative neoplasms, including polycythemia vera.

- 23.Food and Drug Administration. BESREMi (ropeginterferon alfa-2b-njft) Package Insert (2021). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/761166s000lbl.pdf .

- 24.Barbui T, Vannucchi AM, De Stefano V et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus phlebotomy in low-risk patients with polycythaemia vera (Low-PV study): a multicentre, randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 8(3), e175–e184 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gisslinger H, Zagrijtschuk O, Buxhofer-Ausch V et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b, a novel IFNalpha-2b, induces high response rates with low toxicity in patients with polycythemia vera. Blood 126(15), 1762–1769 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gisslinger H, Klade C, Georgiev P et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus standard therapy for polycythaemia vera (PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV): a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial and its extension study. Lancet Haematol. 7(3), e196–e208 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This original article reports the results from PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV trials comparing ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus hydroxyuria.

- 27.Kiladjian JJ, Klade C, Georgiev P et al. Long-term outcomes of polycythemia vera patients treated with ropeginterferon Alfa-2b. Leukemia 36(5), 1408–1411 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This article reports on the 5-years results from PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV.

- 28.Grunwald MR, Kuter DJ, Altomare I et al. Treatment patterns and blood counts in patients with polycythemia vera treated with hydroxyurea in the United States: an analysis from the REVEAL study. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 20(4), 219–225 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiladjian JJ, Zachee P, Hino M et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib versus best available therapy in polycythaemia vera (RESPONSE): 5-year follow up of a phase 3 study. Lancet Haematol. 7(3), e226–e237 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masciulli A, Ferrari A, Carobbio A, Ghirardi A, Barbui T. Ruxolitinib for the prevention of thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 4(2), 380–386 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tremblay D, Srisuwananukorn A, Ronner L et al. European LeukemiaNet Response Predicts Disease Progression but Not Thrombosis in Polycythemia Vera. Hemasphere 6(6), e721 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abu-Zeinah G, Silver RT, Abu-Zeinah K, Scandura JM. Normal life expectancy for polycythemia vera (PV) patients is possible. Leukemia 36(2), 569–572 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merative Micromedex. RED BOOK [database on the internet] (2023). http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/

- 34.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CY 2022 Physician Fee Schedule Look-Up Tool (HCPCS Code 96372) (2022). https://www.cms.gov/medicare/physician-fee-schedule/search

- 35.Copher R, Kee A, Gerds A. Treatment patterns, health care resource utilization, and cost in patients with myelofibrosis in the United States. Oncologist 27(3), 228–235 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang R, Janssen MFB, Pickard AS. US population norms for the EQ-5D-5L and comparison of norms from face-to-face and online samples. Qual. Life Res. 30(3), 803–816 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abelsson J, Andreasson B, Samuelsson J et al. Patients with polycythemia vera have worst impairment of quality of life among patients with newly diagnosed myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leuk. Lymphoma 54(10), 2226–2230 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnston K, Stoffman JM, Mickle AT et al. Preferences and Health-Related Quality-of-Life Related to Disease and Treatment Features for Patients with Hemophilia A in a Canadian General Population Sample. Patient Prefer Adherence 15, 1407–1417 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V. Preference-Based EQ-5D index scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Decis Making 26(4), 410–420 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. 2020–2023 Value Assessment Framework. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, Boston, MA, USA: (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferrari A, Carobbio A, Masciulli A et al. Clinical outcomes under hydroxyurea treatment in polycythemia vera: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Haematologica 104(12), 2391–2399 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reyes C, Engel-Nitz NM, DaCosta Byfield S et al. Cost of Disease Progression in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia, Acute Myeloid Leukemia, and Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Oncologist 24(9), 1219–1228 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan F, Peng S, Fleurence R, Linnehan JE, Knopf K, Kim E. Economic analysis of decitabine versus best supportive care in the treatment of intermediate- and high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes from a US payer perspective. Clin. Ther. 32(14), 2444–2456 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiladjian J-J, Klade C, Georgiev P et al. 4345 Efficacy and Safety of Long-Term Ropeginterferon Alfa-2b Treatment in Patients with Low-Risk and High-Risk Polycythemia Vera (PV). In: 64th ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition. American Society of Hematology, LA, USA: (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barbui T, Vannucchi AM, De Stefano V et al. Ropeginterferon versus Standard Therapy for Low-Risk Patients with Polycythemia Vera. NEJM Evidence 2(6), (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris Z, Kaizer H, Wei A et al. Characterization of myeloproliferative neoplasms in the paediatric and young adult population. Br. J. Haematol. 201(3), 449–458 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Altomare I, Parasuraman S, Paranagama D et al. Real-World Dosing Patterns of Ruxolitinib in Patients With Polycythemia Vera Who Are Resistant to or Intolerant of Hydroxyurea. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 21(11), e915–e921 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.