Abstract

The incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) in the United States continues to grow rapidly, paralleling the overweight and obesity epidemic. For many years the only therapeutic options for type 2 DM were sulfonylureas and insulin. However, over the last 9 years there has been an explosion of new and exciting agents approved for the treatment of type 2 DM. Some of the treatments target insulin deficiency and others insulin resistance, the hallmarks of the disease. Other drugs delay the intestinal absorption of carbohydrate. Recently several combination agents have been released. With these new drugs has come an overwhelming mountain of information, making it difficult for the busy clinician to know how best to manage the ever-increasing portion of patients with type 2 DM.

New questions have arisen: Which agent to start as first line? How much of this drug to use before adding something else? How long for this drug to reach full effect? Which agent to add second? Should a patient uncontrolled on dual therapy begin insulin or start a third oral agent? If insulin therapy is started, what should become of the patient's oral agents? How best to explain the patient's weight gain on therapy? These are not easy questions and no review can fully detail all the therapeutic combinations possible. Instead, the practical approach of reviewing the agents in terms of their mechanism of action and critically comparing their dosing, effect and cost, is undertaken herein. Also addressed is the possible niche some newer classes of agents and combination drugs may or may not hold in the management of type 2 DM. The decision of using insulin versus a third oral agent will be looked at from the standpoint of where the patient is on dual therapy in relation to the hemoglobin A1c goal. In this way it is hoped that some clarity will be brought to the dizzying array of information that both the physician and patient have to deal with in regard to the management of this prevalent and serious disease.

Keywords: Type 2 DM, Insulin secretagogues, Insulin sensitizers, Diabetes therapy, Glucose absorption inhibitors

INTRODUCTION

Vast amounts of literature have been written about the current and growing epidemic of diabetes mellitus (DM) and its associated complications. The cost of diabetes to the United States healthcare system is staggering, amounting to $100 billion in direct and indirect expenditures annually.1 Currently 15 million Americans have diabetes, one third of whom have yet to be diagnosed. Ninety percent of these cases represent type 2 DM. The incidence of type 2 DM and its precursor (impaired glucose tolerance) continues to rise, paralleling that of overweight and obesity.2 Frighteningly, this is occurring in children and adolescents, as well as adults.3 Over the last 9 years a growing number of oral medications and newer insulin analogs have become available for use in type 2 DM. The optimal use of these agents has become more difficult with the increased complexity a greater number of choices bring. This task is made more challenging with the pharmaceutical industry spending large sums of money annually in direct marketing toward physicians and patients.4 For better or worse, prescribing patterns are affected by this marketing, or obviously such amounts of money would not be so spent.5

It should be stressed that despite the vast literature available, many patients and physicians alike still view type 2 DM as a “less severe” illness than type 1 DM. On the contrary, because of the much greater prevalence of type 2 DM, the great majority of microvascular complications occurs in these patients. The increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in type 2 DM has led to more stringent goals for the management of cholesterol and blood pressure, in addition to the use of aspirin.6 Therefore, close attention should be paid to the overall cardiovascular health of patients with type 2 DM, not just their hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).

The optimal management of type 2 DM cannot be discussed by simply outlining what agents are available along with their doses, effectiveness and side effects. More difficult management issues need to be explored as well. Also, as CVD is so prevalent in patients with type 2 DM the potential for non-glycemic benefits of some of the newer agents deserves mention. This review will focus not only on the oral agents per se, but also on their proper use over time and in combination. The potential benefit of non-glycemic effects of some agents will be mentioned briefly. The use of insulin in combination with oral agents will also be described. It is hoped that through a better understanding of these agents providers of care for patients with type 2 DM will be aided in the most difficult task of preventing the complications of the disease.

ORAL AGENTS AVAILABLE FOR THE TREATMENT OF TYPE 2 DM

Prior to 1994 selecting an oral agent for the treatment of type 2 DM was as simple as choosing which sulfonylurea (SU) to use. Since then, a variety of newer agents with unique mechanisms of action and even some combination agents have been released for use as monotherapy or in any number of combination regimens. This trend is likely to continue as even newer agents with completely different mechanisms of action are currently under investigation. Along with this explosion of therapeutic options has come uncertainty over how to use these agents effectively. When thought of simply, there are but three ways in which these agents work toward improving glycemic control: (1) increasing insulin secretion [insulin secretagogues], (2) increasing insulin action [insulin sensitizers], and (3) decreasing insulin need [inhibitors of glucose absorption].

Increasing insulin secretion (secretagogues)

SULFONYLUREAS

These agents were first introduced for the management of type 2 DM in the mid-1950s. These were the only oral agents available in the United States until 1994. These drugs work by binding to a regulatory protein (commonly referred to as the SU receptor) on pancreatic β-cells, which in turn, results in closure of ATP-dependent potassium (KATP) channels leading to membrane depolarization and influx of calcium through voltage-dependent channels, which subsequently leads to insulin secretion.7

As the second generation SUs are currently the most widely used, this discussion will be limited to these agents. The dosing, and the cost and effect of the SUs on HbA1c are summarized in table 1. As is apparent, their relative potency is similar. The most common side effect of the SUs is hypoglycemia, the risk of which varies somewhat among the agents. It is generally accepted that glyburide has twice the risk of hypoglycemia compared to the other second generation SUs.8,9 This is due to increased duration of binding to the SU receptor, resulting in fasting hyperinsulinemia with glyburide. This degree of fasting hyperinsulinemia is generally not seen with the other SUs, which are more glucose-sensitive (and thus prandial) in their stimulation of insulin secretion.9 An additional factor in this regard is glyburide's suppression of several counter-regulatory hormones. Weight gain is variable, but tends to be greatest with glyburide, which relates to its greater propensity to induce hypoglycemia. There is some evidence that glipizide-gastrointestinal therapeutic system (glipizide-GITS) and glimepiride are more weight neutral.10 Also, the potential for decreasing myocardial protective mechanisms via cross-reactivity of SUs with myocardial KATP channels seems to be greater with glyburide than other SUs.11

Table 1.

Dosing, efficacy and cost of oral agents for treatment naïve type 2 diabetes mellitus patients.

| Agent | Doses (mg) | Maximum dose (mg) | Maximum effective dose (mg) | HbA1c reduction (%)a | Cost/year ($)b |

| glyburidec | 1.25, 2.5, 5 | 10 bid | 10 qd49,53 | 1.5–2.0 | 130 |

| glipizidec | 5, 10 | 20 bid | 10 qd-bid49–51,54 | 1.5–2.0 | 175d |

| glipizide-GITS* | 2.5, 5, 10 | 20 qd | 5–20 qd49,52 | 1.5–2.0 | 300e |

| glimepiride | 1, 2, 4 | 8 qd | 4 qd67 | 1.5–2.0 | 330 |

| repaglinide | 0.5, 1, 2 | 4 tid | 2 tid68–70 | 1.5–2.0 | 910 |

| nateglinide | 60, 120 | 120 tid | 120 tid | 0.5–1.0 | 1,100 |

| metforminc | 500, 850, 1000 | 850 tid | 1000 bid30 | 1.5–2.0 | 600 |

| Glucophage-XR* | 500 | 2000 qd | 2000 qd | 1.5–2.0 | 1,000 |

| rosiglitazone | 4, 8 | 8 qd, 4 bid | 4 bid32 | 1.5 | 1,875f |

| pioglitazone | 15, 30, 45 | 45 qd | 45 qd | 1.5 | 2,110 |

| acarbose | 50, 100 | 100 tid | 50 tid71 | 0.5–1.0 | 700 |

| miglitol | 25, 50, 100 | 100 tid | 100 tid72 | 0.75–1.2 | 880 |

| Glucovance* | 1.25/250, 2.5/500, 5/500 | 5/500, 2 bid | 2.5/500, 2 bidg | 1.3h | 1,400 |

| Avandamet* | 1/500, 2/500, 4/500 | 2/500, 2 bid | 2/500, 2 bidg | N/Ai | 2,170 |

| Metaglip* | 2.5/250, 2.5/500, 5/500 | 5/500, 2 bid | 5/500, 2 bidg | 2.1j | 1,400 |

a Approximate hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) reduction versus placebo at maximally effective dose, except where indicated.

b Cost of maximally effective dose, average wholesale price for brand name, or maximal allowable cost as set by a regional insurer for generic.

c Generic preparations.

d 10 mg bid dosing.

e 10 mg qd dosing.

f 8 mg tablets, 1/2 bid (4 mg bid: $1,975/year).

g Represents equivalent maximally effective doses of components.

h Mean dose 4.1 mg/824 mg daily (Glucovance package insert).

i No clinical efficacy trials conducted.

j Mean dose 7.4 mg/1477 mg daily (Metaglip package insert).

* Glucophage-XR, Glucovance and Metaglip (Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, NJ).

* Avandamet (GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC).

* Glipizide gastrointestinal therapeutic system (glipizide-GITS).

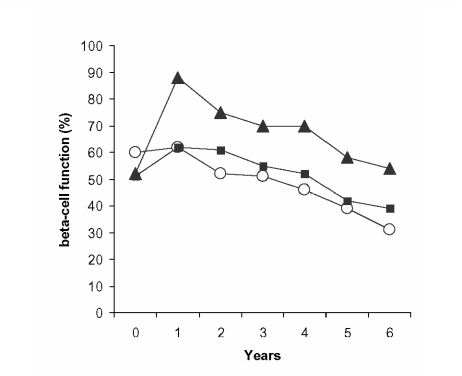

The clinical importance of this is not known, but the controversy regarding increased risk of myocardial events with SUs noted in the University Group Diabetes Program12,13 has finally been put to rest by the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) where a decreased event rate fell just short of statistical significance.14 Another concern laid to rest by the UKPDS it that SUs may hasten the demise of the β-cell. On the contrary, by the end of the study those on SU therapy had higher β-cell function than those not on such therapy because of increased insulin secretion in the first year, the rate of decline thereafter paralleling that of the other groups (figure 1).15 These agents and their metabolites are excreted by various degrees via the kidneys. Caution should be used in the setting of renal insufficiency. Of the second-generation agents, glyburide may be of most concern in this regard with the others being generally safer in mild renal insufficiency.16 Overall, the SUs are a potent, safe and cost-effective management option in type 2 DM.

Figure 1.

β-cell function in patients allocated to diet therapy (○), sulfonylurea (▴), or metformin (▪) (adapted from reference 15).

NON-SU SECRETAGOGUES

Repaglinide and nateglinide were released in 1998 and 2001, respectively. These agents are not SUs. These agents are also a different class from each other, repaglinide being a member of the meglitinide family and nateglinide a derivative of phenylalanine. The main difference between these agents and the SUs is the rapidity and duration of stimulation of insulin secretion. The non-SUs differ from SUs in two ways:17 (1) dosing at each meal, (2) potentially less risk of hypoglycemia, especially if a meal is missed.

In terms of overall potency, repaglinide is equivalent to the SUs, with nateglinide being less effective (table 1). As they are metabolized and excreted by hepatic mechanisms exclusively, these agents can be safely used in more advanced renal insufficiency (vs. glimepiride for example).

Much has been said in regard to the ability of these agents to control postprandial glucose (PPG) because of their faster onset of action. There is no doubt that control of PPG is important in the optimal control of type 2 DM. There is also evidence that increased PPG levels may translate into a greater risk of CVD.18 If PPG levels are targeted, the goal should be <140 mg/dL at 2 hours, as documented by the American Diabetes Association position statement.19 The unanswered question is how best to achieve this postprandial control.

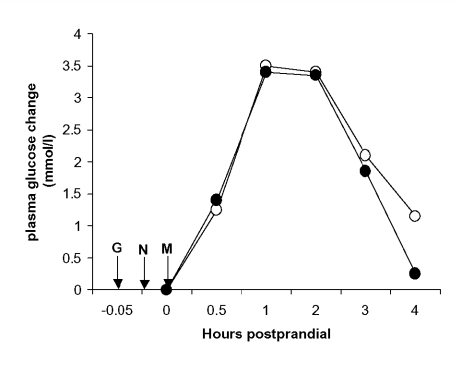

Despite the methods in which these newer insulin secretagogues have been marketed, there is little published evidence they control PPG better than the SUs. Indeed, Landgraf et al. failed to show a significant difference in PPG between repaglinide and glibenclamide (glyburide).20 However, nateglinide did fare somewhat better than glyburide, with a PPG of <140 mg/dL achieved in 30% and 13%, respectively.21 Recently, data has emerged comparing glipizide to both repaglinide22 and nateglinide23 revealing little, if any, difference in PPG control (figure 2). In fact, the conclusion of Carroll et al. went as far as to say,

Figure 2.

Mean postprandial plasma glucose excursions from baseline with glipizide (•) or nateglinide (○) after a standardized breakfast in 20 subjects with type 2 diabetes (adapted from reference 23). G, glipizide; M, meal; N, nateglinide.

“The clinical decision to use glipizide versus nateglinide should be based on factors other than the control of postprandial hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes.”23 Although not directly compared with the non-SU secretagogues, glimepiride also has a significant effect on PPG control.11 The usefulness of these agents remains to be seen and must take into account their increased cost, and what differences there truly are versus the SUs in terms of PPG control.

Increasing insulin action (insulin sensitizers)

BIGUANIDES

Metformin had been in widespread use overseas for many years before being approved in the United States in 1994. This delay was due to the high risk of fatal lactic acidosis with phenformin, which was removed from the United States market in the mid-1970s. The risk of this severe complication is 10 to 20 times lower with metformin, and is limited to those with renal insufficiency and other predispositions to acidosis, such as chronic pulmonary disease and congestive heart failure.24 Metformin's actual mechanism of action is not fully known, but its main effect is to decrease hepatic gluconeogenesis, thus improving fasting hyperglycemia.25 There is also a peripheral effect of improved insulin action in muscle tissue, which may be related to metformin's ability to lower free fatty acids (FFA)26,27 and/or its induction of mild weight loss through decreased caloric intake.

Metformin is likely the initial treatment of choice for most patients with type 2 DM for a variety of reasons. By improving insulin sensitivity it also improves a variety of other factors related to increased cardiovascular risk.28 These improvements in surrogate markers do indeed translate into decreased event rates. Although the exact mechanism was unclear in the obese cohort of the UKPDS, metformin (vs. conventional therapy) was shown to significantly reduce the rate of myocardial infarction and all-cause mortality.29 Metformin is also advantageous in that it is often weight neutral or induces slight weight loss through its appetitesuppressive action. This is true of monotherapy and in combination with other agents.

The main side effect of metformin is gastrointestinal intolerance (nausea, abdominal pain and diarrhea), which occurs in approximately 30% of patients.30 This problem is related to total dose and the rapidity with which the medication is titrated upward. Much of this difficulty can be avoided by administration with food and by increasing the dose by 500 mg per day, every 1 to 2 weeks (thus allowing 3 to 7 weeks before a full dose is reached). Very few patients need to discontinue metformin due to adverse events when these guidelines are followed. As mentioned, the risk of lactic acidosis with metformin is minimal so long as its use is avoided in those at risk (serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dL in men or ≥1.4 mg/dL in women). When uncertainty arises as to the validity of serum creatinine, creatinine clearance should be measured or calculated (≥60 mL/minute is considered safe). Metformin should also be avoided in patients with liver disease or habits that put them at risk of such (alcohol abuse and/or binge drinking) and other conditions that may predispose to acidosis (congestive heart failure and/or pulmonary disease). Its use in patients over 80 years of age also carries greater risk. Lastly, metformin should be held for 48 hours prior to and after surgery and/or administration of radiocontrast materials.

It deserves mention that an extended-release metformin, Glucophage XR (Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, NJ), is now available allowing once daily administration. Although priced less than brand name Glucophage (Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, NJ), it is significantly more expensive than generic metformin (table 1). While studies showed only a 9.5% incidence of diarrhea, it should be recognized that this low rate might have stemmed from the much lower incidence of diarrhea in the entire study. In fact, the risk of diarrhea with Glucophage XR was 3 to 4.5 times that of placebo, a similar degree of increase over placebo seen in trials of metformin (Glucophage XR package insert). Also, in these same trials there was an unexplained increase in triglyceride levels with Glucophage XR that was not seen in trials of metformin. Thus, there seems to be no benefit of Glucophage XR beyond that of once daily dosing, which is unlikely to be worth the increased cost versus generic metformin.

THIAZOLIDINEDIONES (TZD)

With the introduction of troglitazone in 1997, an exciting new era in the management of type 2 DM dawned. Despite the removal of troglitazone from the market in 2000 because of liver toxicity, two newer agents, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone (approved in 1999), continue in widespread use without evidence of similar problems.31 However, the edema and weight gain seen with the TZDs can be limiting in some patients. These agents bind to peroxisome proliferator activator receptor-gamma nuclear receptors affecting gene regulation in target cells. Interestingly, this alteration of gene transcription takes place in adipocytes and the genes concerned primarily regulate fatty acid metabolism, the net result of which is to decrease serum FFA by approximately 20% to 40%.32–34 This reduction in FFA, in turn, improves insulin action in muscle tissue, thus implicating elevated FFA as a major contributor to insulin resistance. Further-more, this reduction in FFA improves β-cell function by decreasing lipotoxicity, a process whereby increased FFA eventually leads to β-cell death.35 In various trials the TZDs have increased β-cell function by up to 60%.33,35,36 Unlike the increase in β-cell function seen with SUs in the first year of the UKPDS, the increased functional capacity induced by TZDs is maintained for at least 2 years.37,38

Both agents have been approved for use as monotherapy and in combination with other oral agents. They are not approved for use in most triple therapy regimens, except for the combination of Glucovance (Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, NJ) and rosiglitazone. Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone have been approved in combination with insulin. TZDs are contraindicated in patients with liver disease and those with New York Heart Association class III or IV cardiac status. From a therapeutic standpoint, there is likely no significant difference between these agents in terms of glucose-lowering effect39–43 and they may be slightly less potent than the SUs or biguanides (table 1). This apparent decreased potency may be related to a significant rate of non-responders; however, as when responders are looked at separately, the potency is comparable to other agents (see later).44 Their effect on glucose control may be more sustained over time than that of other agents.37,38 The durability of glucose control over time with glyburide, metformin, or rosiglitazone in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetics will be definitively addressed in A Diabetes Outcome Progression Trial (ADOPT).45

Like metformin, the TZDs have widespread beneficial effects on a variety of surrogate markers of cardiovascular risk; extensive study is ongoing in this area. Perhaps the most noticeable of these non-glycemic effects is the ability of the TZDs to raise high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol by up to 13%.32,39–43,46 Furthermore, there may be a differential effect on HDL subtypes with rosiglitazone, preferentially effecting HDL-2 (the most protective HDL subfraction).46 The effects on triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels tend to be more variable and there is mounting evidence that pioglitazone performs consistently better in these regards than rosiglitazone.39–43 A double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel design, phase IV study directly comparing the effects of these two agents on the lipoprotein profile is currently underway. Despite their tendency to increase total LDL cholesterol, the TZDs shift the LDL particle size to larger, less atherogenic molecules, although it is uncertain what this means to overall cardiovascular risk.46

In addition to these effects on lipid parameters, the TZDs beneficially affect plasminogen activator inhibitor, C-reactive protein, endothelial function, smooth muscle proliferation and carotid intimal media thickness. Extensive reviews on this subject can be found.47,48 Despite this growing body of circumstantial evidence, the most crucial question remains unanswered; will the use of TZDs translate into a reduction in cardiovascular events? The answer will be known the latter part of this decade. The following trials will definitely settle these issues:

Rosiglitazone Evaluated for Cardiac Outcomes and Regulation of glycemia in Diabetes (RECORD);

Action to Control CardiOvascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD);

Bypass Angioplasty Revasculization Investigation Type 2 Diabetes (BARI-2D);

PROspective Actos Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events (PROactive [Actos, Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc., Lincolnshire, IL]).

These issues of durable control over time and cardiovascular outcomes are of great importance not only to physicians caring for patients, but also to help healthcare systems determine whether these slightly less potent agents are worth their cost.

Decreasing insulin need (inhibitors of glucose absorption)

ALPHA-GLUCOSIDASE INHIBITORS (AGIs)

The two agents in this class currently available, acarbose and miglitol, were released in 1996. These drugs only affect PPG levels and do so by competitively inhibiting the binding of oligosaccharides to the alpha-glucosidase enzyme in the brush border of the small intestine. This enzyme cleaves oligosaccharides to monosaccharides, which can then be absorbed. Thus, when taken with the first bite of food, these agents delay the absorption of carbohydrate. These drugs do not cause hypoglycemia or weight gain. However, because they only affect PPG levels the potency of the AGIs is significantly less than most other agents (table 1). For this reason and for the often significantly troublesome side effects of flatulence, abdominal pain and diarrhea, these agents are used sparingly in the United States.

IMPORTANT MANAGEMENT ISSUES IN TYPE 2 DM

Maximal prescribable dose vs. maximally effective dose

As mentioned previously, the cost of diabetes on the United States healthcare system is staggering. As newer, more costly treatment modalities become available, physicians need to be increasingly aware not only of the agents themselves, but also of how to use them cost-effectively. The maximal prescribable doses and maximally effective doses are listed in table 1. There is some debate as to the validity of describing a “maximally effective” dose because of the high degree of variability in response to SUs.49–51 While the author uses the listed maximally effective doses as such for glyburide and glimepiride, clinical experience has led to utilizing up to 10 mg bid for glipizide and 10 mg qd for glipizide-GITS.

Significant cost savings can be achieved by a better understanding of the maximally effective dosage of medications and how quickly to expect to reach that full effect. Savings can then be achieved on several fronts:

Avoidance of prolonged therapy that is unlikely to work.

Use of only as much of a given agent as is needed.

More timely addition of other treatment modalities.

An all too common scenario is when an uncontrolled patient, for example with a HbA1c of 10.5% on glyburide 10 mg daily, is told to increase to 10 mg twice daily and follow-up in several months. A more appropriate sequence of events might start with the realization that the effect of glyburide is close to full at 10 mg daily and any increase will certainly not get this patient to goal. Secondly, even if a dose increase was attempted, the full effect of an SU would be seen within 1 to 2 weeks, with follow-up planned accordingly.52 Delayed follow-up only allows for continued poor control of diabetes, further raising the risk of costly complications. How many patients are being treated with an SU dose beyond what they need and at what extra cost? Generally, increasing an SU from the maximally effective to maximum dose leads to an additional HbA1c lowering effect of ≤0.4% while doubling cost.49,50,53,54 Granted these medications are among the least expensive, but they are also the most widely prescribed. Thus, the savings of optimal dosing would likely be substantial.

Several points regarding the insulin sensitizers warrant mention here as well. First, metformin dosages beyond 1,000 mg twice daily will unlikely offer further benefit and may increase the risk of gastrointestinal side effects that could potentially result in the discontinuation of this extremely useful agent.30 The effect of metformin on glucose control is also seen fairly quickly, on the order of one to two weeks. The TZDs are somewhat less confusing in this regard in that the maximal prescribable dose is the same as the maximally effective dose. However, with rosiglitazone it should be noted that 4 mg twice daily may be more potent than 8 mg once daily.32 Lastly, it should be realized that it takes more time for the TZDs to demonstrate full effect than the other oral agents (3 to 4 months vs. several weeks).32,33,36

Combination agents

Within the last 2 years several combination agents have been released for use in the management of type 2 DM. The patient-friendly nature of these agents is a frequently sited benefit. “By prescribing these agents physicians can decrease cost (one co-pay) and increase compliance (fewer tablets).” The issue of cost certainly is important. However, the number of co-pays is but one factor in medication expenditures. Increased use of more expensive combination agents could increase overall drug cost indirectly by increasing insurance premiums. In regard to compliance, there is published evidence-and it makes intuitive sense-that compliance is higher with one drug versus two.55 Compliance however, is more complex than pill number or frequency, and in the author's opinion, is more strongly affected by physician-patient discussions that occur (or do not occur) in regard to combination therapy. An informed patient is more likely to comply with therapy than an uninformed or confused patient.

For a combination agent to be useful it should be comparable, if not less, in cost to its components and should involve fewer tablets daily (and/or decreased frequency of dosing). With this in mind, it is interesting to see that the various combination agents available do not fare well (table 2). Indeed, none offer fewer tablets daily than the components taken separately. In reference to cost, only Avandamet (GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC) offers savings over its components separately (approximately $400 per year less). There is some unpublished, retrospective data suggesting that Glucovance lowers HbA1c to a greater degree than similar doses of metformin and glyburide separately. These results suggest a benefit of 0.13% to 0.6% with Glucovance. Until these results can be confirmed by a prospective, randomized trial, they should be interpreted with caution. Even if confirmed, the cost-effectiveness of this benefit (an additional $700 annually) is unclear.

Table 2.

Cost comparison of combination agents versus component agents separately.

| Agent | Maximum effective dose (mg) | Cost/year ($)a | Pills/day | Component cost/year ($)a | Pills/day |

| Glucovance* | 2.5/500, 2 bid | 1,400 | 4 | 730 | 3 |

| Avandamet* | 2/500, 2 bid | 2,170 | 4 | 2,550 | 4 |

| Metaglip* | 5/500, 2 bid | 1,400 | 4 | 775 | 4 |

aAverage wholesale price for brand name and maximal allowable cost for generic preparations.

*Glucophage-XR, Glucovance and Metaglip (Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, NJ); Avandamet (GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Dual therapy options

As was shown in the UKPDS, most patients with type 2 DM will eventually require multiple oral agents to maintain optimal glycemic control. With the availability of newer agents that target not only the defect in insulin secretion, but also insulin action, a variety of combination strategies are now possible. A full discussion of these options is beyond the scope of this review, but several excellent summaries are available.56,57 In general, the combination of an insulin secretagogue and sensitizer is most often used and makes intuitive sense given the two major pathogenic mechanisms of type 2 DM (insulin resistance and insulin deficiency). Most often this involves the use of metformin and an SU, as this combination brings together high potency, low cost and a low potential for weight gain. Certainly, a TZD should be substituted for metformin in the case of contraindications to the latter. The use of non-SU secretagogues and/or AGIs brings increased cost, decreased potency, and more potential for side effects (with AGIs).

The potential utility of metformin plus a TZD as dual therapy is interesting. From the standpoint of annual cost, this combination ($2,500) is certainly more expensive than metformin plus SU (∼$800). Metformin plus TZD is also slightly less potent than metformin or TZD plus SU.56,57 However, despite both being insulin sensitizers, this combination still makes good pharmacologic sense, as each improves insulin resistance primarily in a different tissue. Also, there may be some potential for limiting weight gain with TZDs when used with metformin. Furthermore, with the data on preservation of β-cell function, a TZD may help preserve insulin secretory capacity and thus delay secondary failure of oral agent therapy.35,37,38 As well, this combination may allow for tighter glycemic control without the risk of severe hypoglycemia that using an SU might bring. Lastly, the beneficial effects on surrogate markers of CVD cannot help but make one think of the potential benefit of TZDs beyond lowering glucose. What might be the potential cost-benefit of early use of TZD therapy, if they are shown to prevent cardiovascular events and/or deaths?

Triple oral therapy or insulin initiation?

Perhaps one of the most difficult decisions in the management of type 2 DM has become whether to add a third oral agent or to start insulin therapy in an uncontrolled patient. This has only become an issue since the release of the TZDs several years ago. As mentioned previously, there may be several reasons why these agents should be used earlier in the course of treatment than is typically the case. TZDs have now been primarily used as third line agents and they will be discussed as such in this setting. There are three key issues that need considering when facing this decision.

First, how far from goal is the patient? This is important in terms of both whether to add a TZD or start insulin, also how intense an insulin program to start, if need be. The addition of a TZD as a third agent is beneficial in about 60% of patients.44 In those who respond the effect can be substantial with a mean HbA1c reduction of approximately 2.5% seen in a troglitazone trial.44 When taken as a whole (responders and non-responders alike), the mean reduction in HbA1c by adding troglitazone third line was only 1.4%.58 In the only published trial (in letter form) of the currently available TZDs, rosiglitazone added to glimepiride and metformin therapy,59 led to a 1.4% reduction in HbA1c. Patients whose HbA1c is above 9.5% on dual therapy are unlikely to get to goal by the addition of a TZD. A trial can be given to these patients (especially those particularly averse to insulin therapy), but follow-up for consideration of other options should be scheduled after 3 months at maximal dose. The TZD should be discontinued if the patient does not respond. If the decision to start insulin is made it should be stressed that adding bedtime insulin to daytime oral agent therapy will only lower HbA1c by 2% to 2.5%.60 Therefore, if the HbA1c is above 9.5% on dual therapy, the patient is likely to need a more intensive insulin program. Also, there is no evidence that bedtime glargine insulin results in better glycemic control than bedtime neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin, although there is certainly less hypoglycemia with the former.61 Use of glargine insulin increases costs by 65% versus NPH insulin. As is noted in table 3, triple oral agent therapy costs over twice as much as SU and metformin plus bedtime NPH insulin for a similar reduction in HbA1c.

Table 3.

Cost comparison of triple oral therapy (adding thiazolidinediones) versus institution of various insulin programs in patients uncontrolled on sulfonylureas (SU) and metformin combination therapy.

| Therapya | Cost/year ($)b | HbA1c reduction (%) | Comments |

| SU maximal dosec + | |||

| metformin 1000 bid | 900 | N/A | Baseline |

| SU maximal dose + | |||

| metformin 1000 bid + | 1.4 overall58,59 | ||

| TZD maximal dosed | 2,900 | 2.5 for responders44 | ∼60% response rate44 |

| SU maximal dose + | |||

| metformin 1000 bid + | |||

| Bedtime NPHf | 1,200 | 1.5–2.0 | 20 units/day60 |

| NPH and regular bid or | 1,400 | 120 units/daye (70% NPH; 30% short-acting insulin) | |

| NPH and Humalog/NovoLog bidg | 1,900 | Based on dosage | |

| metformin 1000 bid + | |||

| NPH and regular bid or | 1,650 | 82 units/day62,63 (70% NPH: 30% short-acting insulin) | |

| NPH and Humalog/NovoLog bid | 1,950 | Based on dosage | |

| SU maximal dose + | |||

| metformin 1000 bid + | |||

| NPH and regular bid or | 1,600 | 46 units/day62,63 (70% NPH; 30% short-acting insulin) | |

| NPH and Humalog/NovoLog bid | 1,800 | Based on dosage |

a Insulin doses for oral agents plus insulin regimens represent “insulin-sparing” effects of oral agents as described in references noted.

b Average wholesale price for brand name and maximal allowable cost for generic (oral agents ± insulin vials) (syringes included).

c SU (sulfonylurea), Glipizide-GITS 10 mg qd or glimepiride 4 mg qd.

d TZD (thiazolidinediones), pioglitazone 45 qd or rosiglitazone 4 bid.

e Insulin dosage assumes a 100 kg patient requiring 1.2 units/kg/day.

f NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn.

g Humalog (Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN ); NovoLog (Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Princeton, NJ).

Second, if insulin is started, which oral agent(s) should be stopped? This will depend on the type of insulin program contemplated. If bedtime insulin is chosen, then daytime oral agents should be continued. However, if a more intensive insulin program is started, then three options should be considered: (1) continue both the SU and metformin, (2) stop the SU and continue metformin, (3) discontinue both oral agents. Provided appropriate adjustments in insulin are made, each of these three options will likely result in a similar improvement in HbA1c. The cost is surprisingly similar as well, owing to the differences in total insulin dose that will be needed to achieve control (i.e., continuing oral agents will result in less insulin being needed) (table 3).62,63 Continuation of metformin makes intuitive sense, as its mechanism compliments that of insulin and tends to lessen any weight gain that might occur. On the contrary, an SU works in relatively the same manner as insulin and thus is often discontinued. It should be remembered, that the SU is often still having some, albeit an inadequate, effect on glucose control. If discontinued, the SU effect will dissipate quickly, allowing glucose levels to sometimes rise dramatically. The physician should relay this possibility to the patient so as to not mislead them into believing that the insulin is not working and they were “better off on pills.” This may be particularly important in patients who have been very resistant to insulin and in those who are less likely to be compliant with scheduled follow-up. Continuation of both the SU and metformin may be best in these patients. Interestingly, the incremental cost of using fast-acting insulin analogs versus regular insulin becomes less as one or more oral agents are continued with insulin initiation due to an “insulin-sparing” effect of oral agents (table 3). As β-cell failure progresses, an increase in exogenous insulin will be required, thus rendering the continued use of the SU less cost-neutral.

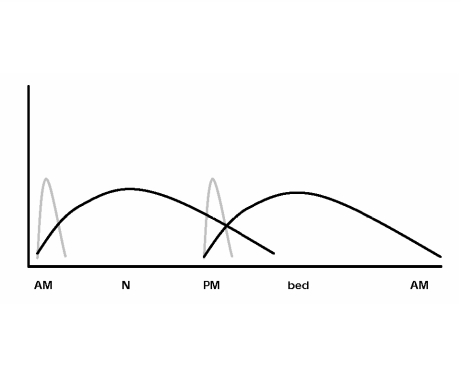

Lastly, what type of insulin program should be started? While a complete discussion of insulin options beyond bedtime dosing only is impossible here, one of the most common strategies is to employ a twice-daily regimen of an intermediately-acting insulin mixed with a short-acting insulin (figure 3). Whether self-mixing of insulin or premixed formulations are used is a matter of preference, but the author prefers the former for its greater flexibility, which allows tighter control with less hypoglycemia. However, self-mixing of insulin may result in less accuracy. The choice of regular insulin versus an insulin analog can be debated. Most often this debate centers on cost-benefit issues as each vial of an insulin analog is priced approximately $34 more than regular insulin. As previously mentioned, this incremental cost becomes less of an issue as oral agents are used with insulin. There is good evidence that both insulin analogs result in improvements in HbA1c (Humalog, 0.3% to 0.4% [Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN] and NovoLog, 0.12% to 0.16% [Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals Inc., Princeton, NJ]) when compared to regular insulin.64 Both analogs have also been shown to reduce hypoglycemic risk (especially nocturnal hypoglycemia) when compared with regular insulin.64 For these reasons the author prefers to use insulin analogs.

Figure 3.

Characteristic action profiles of a twice-daily regimen of an intermediately acting insulin (black line) mixed with a short acting insulin (gray line).

Weight gain associated with the treatment of type 2 DM

Excess body weight and obesity play a large role in the development of type 2 DM. Many patients have struggled unsuccessfully for years to lose weight. Depending on a variety of factors patients might be gaining, maintaining, or even losing weight when they are diagnosed with type 2 DM. The weight gain that often occurs in the first year of treatment can thus be especially frustrating. The propensity for weight gain differs significantly between treatment options with metformin generally being the most weight-neutral. Insulin and the TZDs are at the other end of the spectrum, being prone to cause the greatest weight gain. The causes of weight gain associated with treatment of type 2 DM are listed in table 4. The distribution of weight gain shows two-thirds representing increased fat mass and one-third lean body mass.65 The weight-neutral characteristic of metformin may be due to its ability to decrease energy intake.66

Table 4.

Mechanisms of weight gain with treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The contribution of decreased glycosuria to weight gain can be substantial and will be greatest in those with the poorest baseline control. However, those with the poorest baseline control will improve the most with therapy. For every 100 g per day decrease in glycosuria, there is a positive energy balance of 400 kcal per day.57 With 1 kg of adipose tissue representing approximately 7,700 kcal, it can take just 3 weeks to gain 1 kg once glycosuria ceases. Data from the UKPDS demonstrated a 2.5 kg weight gain in the intensively treated group versus the conventional group. The HbA1c difference was 0.9%.14 Thus, one might expect a 2.8 kg (6.16 pound) weight gain for every 1% decline in HbA1c. The increased food intake associated with hypoglycemia may be related to the treatment of overt events, stimulation of appetite by mild hypoglycemia and attempts by the patient to prevent future events. The greater a drug's propensity to cause hypoglycemia, the larger an issue this becomes. Therefore, glyburide and insulin are the agents for which this component of weight gain can be substantial. The weight gain associated with TZDs is a mixture of increased fat mass and fluid retention.57 Both the incidence of edema and amount of total weight gain with TZDs increases from monotherapy (4%, 1 to 3 kg) to combination with SU (6%, 2 to 2.5 kg) to combination with insulin (15%, 4 to 5.4 kg) (rosiglitazone package insert).

CONCLUSION

The optimal care for the growing number of patients with type 2 DM has been and will remain a complex and difficult task. The importance of optimal control has become clear with the results of the UKPDS. The cost of type 2 DM to the United States healthcare system is enormous. With newer agents now available treatment costs will continue to rise as well. Physicians must critically appraise the true benefits of newer drugs (including combination agents) from the standpoint of glucose control, side effects, potential non-glycemic effects and cost. This difficult task is made even more difficult by the endless barrage of information provided by pharmaceutical companies to physicians and patients alike. It is not acceptable to allow the optimal care of patients with type 2 DM to be so confusing as to be impossible for the busy clinician to implement. When looked at from the standpoint of its component parts-insulin resistance and insulin deficiency-the management of type 2 DM becomes somewhat clearer. Furthermore, if one is allowed the opportunity to truly compare the cost and effectiveness of the newer agents and combination drugs with more tried agents, the appropriate choice of therapy becomes more obvious. The potential benefits of some newer agents on the cardiovascular system and on β-cell rejuvenation need to be considered, as well, with the significant burden that CVD and secondary failure to oral agents represent in the management of type 2 DM. This review hopes to demystify the management of type 2 DM from the initiation of oral agents through dual (potentially triple) therapy onto insulin initiation. The more we can understand about the agents available to us, the better off our patients will be.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Gary S. Plank, Ph.D., former Manager, Security Health Plan Pharmacy, and Eric Paulsen, Manager, Clinic Pharmacy of Wausau, for helping with drug costs. Thanks also to Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation for providing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript through the services of Graig Eldred and Alice Stargardt.

References

- 1.Killilea T. Long-term consequences of type 2 diabetes mellitus: economic impact on society and managed care. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8:S441–S449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Nelson DE, Engelgau MM, Vinicor F, Marks JS. Diabetes trends in the U.S.: 1990–1998. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1278–1283. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha R, Fisch G, Teague B, Tamborlane WV, Banyas B, Allen K, Savoye M, Rieger V, Taksali S, Barbetta G, Sherwin RS, Caprio S. Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance among children and adolescents with marked obesity. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:802–810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Findlay SD. Direct-to-consumer promotion of prescription drugs. Economic implications for patients, payers and providers. Phamacoeconomics. 2001;19:109–119. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200119020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chew LD, O'Young TS, Hazlet TK, Bradley KA, Maynard C, Lessler DS. A physician survey of the effect of drug sample availability on physicians' behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:478–483. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:S33–S50. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmerman BR. Sulfonylureas. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1997;26:511–522. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shorr RI, Ray WA, Daugherty JR, Griffin MR. Individual sulfonylureas and serious hypoglycemia in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:751–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb03729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCall AL. Clinical review of glimepiride. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2001;2:699–713. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cefalu WT, Bell-Farrow A, Wang ZQ, McBride D, Dalgleish D, Terry JG. Effect of glipizide GITS on insulin sensitivity, glycemic indices, and abdominal fat composition in NIDDM. Drug Dev Res. 1998;44:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langtry HD, Balfour JA. Glimepiride. A review of its use in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 1998;55:563–584. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199855040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.University Group Diabetes Program, author. A study of the effects of hypoglycemic agents on vascular complications in patients with adult-onset diabetes. I. Design, methods, and baseline characteristics. Diabetes. 1970;19((suppl 2)):747–783. [Google Scholar]

- 13.University Group Diabetes Program, author. A study of the effects of hypoglycemic agents on vascular complications in patients with adult-onset diabetes. II. Mortality results. Diabetes. 1970;19((suppl 2)):785–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group, author. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulfonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.UKPDS Study Group; UKPDS 16, author. Overview of six years' therapy of type 2 diabetes - α progressive disease. Diabetes. 1995;44:1249–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrower AD. Pharmacokinetics of oral antihyperglycaemic agents in patients with renal insufficiency. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996;31:111–119. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199631020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damsbo P, Clauson P, Marbury TC, Windfeld A. A double-blind randomized comparison of meal-related glycemic control by repaglinide and glyburide in well-controlled type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:789–794. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanefeld M, Fischer S, Julius U, Schulze J, Schwanebeck U, Schmechel H, Ziegelasch HJ, Lindner J. Risk factors for myocardial infarction and death in newly detected NIDDM: the Diabetes Intervention Study, 11-year follow-up. Diabetologia. 1996;39:1577–1583. doi: 10.1007/s001250050617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Diabetes Association, author. Postprandial blood glucose. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:775–778. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landgraf R, Bilo HJ, Muller PG. A comparison of repaglinide and glibenclamide in the treatment of type 2 diabetic patients previously treated with sulphonylureas. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;55:165–171. doi: 10.1007/s002280050613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollander PA, Schwartz SL, Gatlin MR, Haas SJ, Zheng H, Foley JE, Dunning BE. Importance of early insulin secretion: comparison of nateglinide and glyburide in previously diettreated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:983–988. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cozma LS, Luzio SD, Dunseath GJ, Langendorg KW, Pieber T, Owens DR. Comparison of the effects of three insulinotropic drugs on plasma insulin levels after a standard meal. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1271–1276. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.8.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carroll MF, Izard A, Riboni K, Burge MR, Schade DS. Control of postprandial hyperglycemia: optimal use of short-acting insulin secretagogues. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2147–2152. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeFronzo RA, Goodman AM The Multicenter Metformin Study Group, author. Efficacy of metformin in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:541–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hundal RS, Krssak M, Dufour S, Laurent D, Lebon V, Chandramouli V, Inzucchi SE, Schumann WC, Petersen KF, Landau BR, Shulman GI. Mechanism by which metformin reduces glucose production in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2000;49:2063–2069. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.12.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Del Prato S, Marchetto S, Pipitone A, Zanon M, Vigili de Kreutzenberg S, Tiengo A. Metformin and free fatty acid metabolism. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1995;11:S33–S41. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610110506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abbasi F, Carantoni M, Chen YD, Reaven GM. Further evidence for a central role of adipose tissue in the antihyperglycemic effect of metformin. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1301–1305. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.8.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palumbo PJ. Metformin: effects on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 1998;12:110–119. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(97)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group, author. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34) Lancet. 1998;352:854–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garber AJ, Duncan TG, Goodman AM, Mills DJ, Rohlf JL. Efficacy of metformin in type II diabetes: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response trial. Am J Med. 1997;103:491–497. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lebovitz HE, Kreider M, Freed MI. Evaluation of liver function in type 2 diabetic patients during clinical trials: evidence that rosiglitazone does not cause hepatic dysfunction. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:815–821. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips LS, Grunberger G, Miller E, Patwardhan R, Rappaport EB, Salzman A The Rosiglitazone Clinical Trials Study Group, author. Once- and twice-daily dosing with rosiglitazone improves glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:308–315. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fonseca V, Rosenstock J, Patwardhan R, Salzman A. Effect of metformin and rosiglitazone combination therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:1695–1702. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamasaki Y, Kawamori R, Wasada T, Sato A, Omori Y, Eguchi H, Tominaga M, Sasaki H, Ikeda M, Kubota M, Ishida Y, Hozumi T, Baba S, Uehara M, Shichiri M, Kaneko T Glucose Clamp Study Group, Japan, author. Pioglitazone (AD-4833) ameliorates insulin resistance in patients with NIDDM. AD-4833 Tohoku J Exp Med. 1997;183:173–183. doi: 10.1620/tjem.183.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell DS, Ovalle F. Tissue triglyceride levels in type 2 diabetes and the role of thiazolidinediones in reversing the effects of tissue hypertriglyceridemia: review of the evidence in animals and humans. Endocr Pract. 2001;7:135–138. doi: 10.4158/EP.7.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Einhorn D, Rendell M, Rosenzweig J, Egan JW, Mathisen AL, Schneider RL The Pioglitazone 027 Study Group, author. Pioglitazone hydrochloride in combination with metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther. 2000;22:1395–1409. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(00)83039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gould E, Cobitz A. Long-term durability of rosiglitazone as monotherapy or in combination therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes; Proceed 84th Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society, San Francisco, CA, June 19–22, 2002; [June 24, 2003]. Available at: http://www.abstracts-on-line.com/abstracts/ENDO/Itinerary_Builder/PrintOut.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bell DS, Ovalle F. Long-term efficacy of triple oral therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2002;8:271–275. doi: 10.4158/EP.8.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.King AB. A comparison in a clinical setting of the efficacy and side effects of three thiazolidinediones. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:557. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.4.557b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.LaCivita KA, Villarreal G. Differences in lipid profiles of patients given rosiglitazone followed by pioglitazone. Curr Med Res Opin. 2002;18:363–370. doi: 10.1185/030079902125001038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyle PJ, King AB, Olansky L, Marchetti A, Lau H, Magar R, Martin J. Effects of pioglitazone and rosiglitazone on blood lipid levels and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective review of randomly selected medical records. Clin Ther. 2002;24:378–396. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)85040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan MA, St Peter JV, Xue JL. A prospective, randomized comparison of the metabolic effects of pioglitazone or rosiglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes who were previously treated with troglitazone. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:708–711. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gegick CG, Altheimer MD. Comparison of effects of thiazolidinediones on cardiovascular risk factors: observations from a clinical practice. Endocr Pract. 2001;7:162–169. doi: 10.4158/EP.7.3.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gavin LA, Barth J, Arnold D, Shaw R. Troglitazone add-on therapy to a combination of sulfonylureas plus metformin achieved and sustained effective diabetes control. Endocr Pract. 2000;6:305–310. doi: 10.4158/EP.6.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viberti G, Kahn SE, Greene DA, Herman WH, Zinman B, Holman RR, Haffner SM, Levy D, Lachin JM, Berry RA, Heise MA, Jones NP, Freed MI. A diabetes outcome progression trial (ADOPT): an international multicenter study of the comparative efficacy of rosiglitazone, glyburide, and metformin in recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1737–1743. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freed MI, Ratner R, Marcovina SM, Kreider MM, Biswas N, Cohen BR, Brunzell JD Rosiglitazone Study 108 investigators, author. Effects of rosiglitazone alone and in combination with atorvastatin on the metabolic abnormalities in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:947–952. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parulkar AA, Pendergrass ML, Granda-Ayala R, Lee TR, Fonseca VA. Nonhypoglycemic effects of thiazolidinediones. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:61–71. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raji A, Plutzky J. Insulin resistance, diabetes and atherosclerosis: thiazolidinediones as therapeutic interventions. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2002;4:514–521. doi: 10.1007/s11886-002-0116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garber AJ. Using dose-response characteristics of therapeutic agents for treatment decisions in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2000;2:139–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2000.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feinglos MN, Hollis CR. The benefit of increasing sulfonylurea dose. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:537. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-6-199309150-00028. author reply 538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Epstein MD. The benefit of increasing sulfonylurea dose. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:537–538. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-6-199309150-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simonson DC, Kourides IA, Feinglos M, Shamoon H, Fischette C The Glipizide Gastrointestinal Therapeutic System Study Group, author. Efficacy, safety, and dose-response characteristics of glipizide gastrointestinal therapeutic system on glycemic control and insulin secretion in NIDDM. Results of two multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:597–606. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Groop LC, author. Sulfonylureas in NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:737–754. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stenman S, Melander A, Groop PH, Groop LC. What is the benefit of increasing the sulfonylurea dose? Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:169–172. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dailey G, Kim MS, Lian JF. Patient compliance and persistence with antihyperglycemic drug regimens: evaluation of a Medicaid patient population with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1311–1320. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Inzucchi SE. Oral antihyperglycemic therapy for type 2 diabetes: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;287:360–372. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lebovitz HE. Oral therapies for diabetic hyperglycemia. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2001;30:909–933. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yale JF, Valiquett TR, Ghazzi MN, Owens-Grillo JK, Whitcomb RW, Foyt HL. The effect of a thiazolidinedione drug, troglitazone, on glycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus poorly controlled with sulfonylurea and metformin. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:737–745. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-9_part_1-200105010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kiayias JA, Vlachou ED, Theodosopoulou E, Lakka-Papadodima E. Rosiglitazone in combination with glimepiride plus metformin in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1251–1252. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yki-Järvinen H, Ryysy L, Nikkilä K, Tulokas T, Vanamo R, Heikkilä M. Comparison of bedtime insulin regimens in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:389–396. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-5-199903020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yki-Järvinen H, Dressler A, Ziemen M HOE 901/3002 Study Group, author. Less nocturnal hypoglycemia and better post-dinner glucose control with bedtime insulin glargine compared with bedtime NPH insulin during insulin combination therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1130–1136. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.8.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yki-Järvinen H. Combination therapies with insulin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:758–767. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buse J. Combining insulin and oral agents. Am J Med. 2000;108:23S–32S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heise T, Heinemann L. Rapid and long-acting analogues as an approach to improve insulin therapy: an evidence-based medicine assessment. Curr Pharm Des. 2001;7:1303–1325. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Laville M, Andreelli F. Mechanisms for weight gain during blood glucose normalization. Diabetes Metab. 2000;26((suppl 3)):42–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Makimattila S, Nikkilä K, Yki-Järvinen H. Causes of weight gain during insulin therapy with and without metformin in patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1999;42:406–412. doi: 10.1007/s001250051172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goldberg RB, Holvey SM, Schneider J The Glimepiride Protocol #201 Study Group, author. A dose-response study of glimepiride in patients with NIDDM who have previously received sulfonylurea agents. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:849–856. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.8.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Strange P, Schwartz SL, Graf RJ, Polvino W, Weston I, Marbury TC, Huang WC, Goldberg RB. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and dose-response relationship of repaglinide in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 1999;1:247–256. doi: 10.1089/152091599317143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schade DS. Repaglinide dose response? A clinician's viewpoint. Diabetes Technol Ther. 1999;1:257–258. doi: 10.1089/152091599317152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Strange P, Goldberg RB. Repaglinide dose response? A clinician's viewpoint. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2000;2:119–121. doi: 10.1089/152091599316847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fischer S, Hanefeld M, Spengler M, Boehme K, Temelkova-Kurktschiev T. European study on dose-response relationship of acarbose as a first-line drug in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: efficacy and safety of low and high doses. Acta Diabetol. 1998;35:34–40. doi: 10.1007/s005920050098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Drent ML, Tollefsen AT, van Heusden FH, Hoenderdos EB, Jonker JJ, van der Veen EA. Dose-dependent efficacy of miglitol, an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor, in type 2 diabetic patients on diet alone: results of a 24-week double-blind placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Nutr Metab. 2002;15:152–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]