This randomized clinical trial assesses the effect of hypoglossal nerve stimulation vs sham intervention on blood pressure, sympathetic activity, and vascular function in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

Key Points

Question

What is the effect of hypoglossal nerve stimulation (HGNS) therapy on measures of cardiovascular health in patients with moderate-severe obstructive sleep apnea?

Findings

In this double-blind, sham-controlled, randomized crossover therapy trial of 60 patients, mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure and other cardiovascular end points were not significantly different between sham and active HGNS therapy.

Meaning

Future sham-controlled HGNS trials can be better designed to examine meaningful short-term and long-term outcomes in patients undergoing HGNS therapy for obstructive sleep apnea.

Abstract

Importance

Sham-controlled trials are needed to characterize the effect of hypoglossal nerve stimulation (HGNS) therapy on cardiovascular end points in patients with moderate-severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Objective

To determine the effect of therapeutic levels of HGNS, compared to sham levels, on blood pressure, sympathetic activity, and vascular function.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This double-blind, sham-controlled, randomized crossover therapy trial was conducted from 2018 to 2022 at 3 separate academic medical centers. Adult patients with OSA who already had an HGNS device implanted and were adherent and clinically optimized to HGNS therapy were included. Participants who had fallen asleep while driving within 1 year prior to HGNS implantation were excluded from the trial. Data analysis was performed from January to September 2022.

Interventions

Participants underwent a 4-week period of active HGNS therapy and a 4-week period of sham HGNS therapy in a randomized order. Each 4-week period concluded with collection of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), pre-ejection period (PEP), and flow-mediated dilation (FMD) values.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The change in mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure was the primary outcome, with other ABPM end points exploratory, and PEP and FMD were cosecondary end points.

Results

Participants (n = 60) were older (mean [SD] age, 67.3 [9.9] years), overweight (mean [SD] body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, 28.7 [4.6]), predominantly male (38 [63%]), and had severe OSA at baseline (mean [SD] apnea-hypopnea index, 33.1 [14.9] events/h). There were no differences observed between active and sham therapy in 24-hour systolic blood pressure (mean change on active therapy, −0.18 [95% CI, −2.21 to 1.84] mm Hg), PEP (mean change on active therapy, 0.11 [95% CI, −5.43 to 5.66] milliseconds), or FMD (mean change on active therapy, −0.17% [95% CI, −1.88% to 1.54%]). Larger differences between active and sham therapy were observed in a per-protocol analysis set (n = 20) defined as experiencing at least a 50% reduction in apnea-hypopnea index between sham and active treatment.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this sham-controlled HGNS randomized clinical trial, mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure and other cardiovascular measures were not significantly different between sham and active HGNS therapy. Several methodologic lessons can be gleaned to inform future HGNS randomized clinical trials.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03359096

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a disorder characterized by repetitive collapse of the upper airway during sleep that leads to nocturnal hypoxemia and recurrent arousals.1 In addition to decreased neurobehavioral performance from recurrent nocturnal arousals, there is an increased risk of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events, as well as heightened all-cause mortality, in patients with moderate-severe OSA.2,3 As the prevalence of moderate-severe OSA has increased in the past decade, now affecting 10% to 17% of men and 3% to 9% of women, untreated OSA represents a looming public health risk for cardiovascular disease.4

It has been frequently demonstrated that blood pressure, including 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), improves with positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy and that the effect is reversed when the patient discontinues PAP therapy for as little as 2 weeks.5,6,7,8,9,10,11 Intermediate measures of sympathetic and vascular function provide mechanistic insight into these effects. Pre-ejection period (PEP), the time between the electrical and mechanical systole, is a noninvasive measure of cardiac sympathetic nervous system activity.10 Patients with increased sympathetic activity, including patients with OSA, show decreased PEP due to high β-adrenergic tone.11 Flow-mediated dilation (FMD) measures the brachial artery dilatory response to stress as a measure of vascular health. In untreated patients with severe OSA, FMD values are significantly lower than in control participants,12,13 and PAP therapy improves these parameters.14,15 To our knowledge, no studies have thoroughly examined ABPM, PEP, and FMD simultaneously in the context of OSA treatment. Most of the studies examining long-term cardiovascular morbidity with OSA showed an association of OSA with hypertension,16 and while improvements in ABPM may correlate with improvement in vascular measures, it still remains unclear if alterations in vascular function testing reflect alterations in hypertensive burden.17

Despite the cardiovascular benefits of PAP therapy, fewer than 50% of patients in clinical practice adequately use treatment.18,19,20 As reviewed in prior studies, oral appliance and PAP therapy have comparable effects on blood pressure, while effects of surgical interventions for OSA are more varied.21,22 Hypoglossal nerve stimulation (HGNS), approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of OSA in 2014, is a surgically implanted device that stimulates the primary pharyngeal dilator muscle in synchrony with the respiratory cycle. At 36 months, patients demonstrated stable, marked improvement in key polysomnography indices, sleepiness measures, and functional outcomes with HGNS adherence greater than 80%.23

There exists a dearth of literature related to the effect of HGNS on cardiovascular sequelae.24,25 Herein, we describe the results of a double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled crossover study to examine the cardiovascular effect of HGNS in participants with moderate-severe OSA. Our primary hypothesis was that there would be a significant reduction in mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure with active therapy compared to sham therapy; secondary hypotheses included expected improvements in PEP and FMD.

Methods

Trial Design

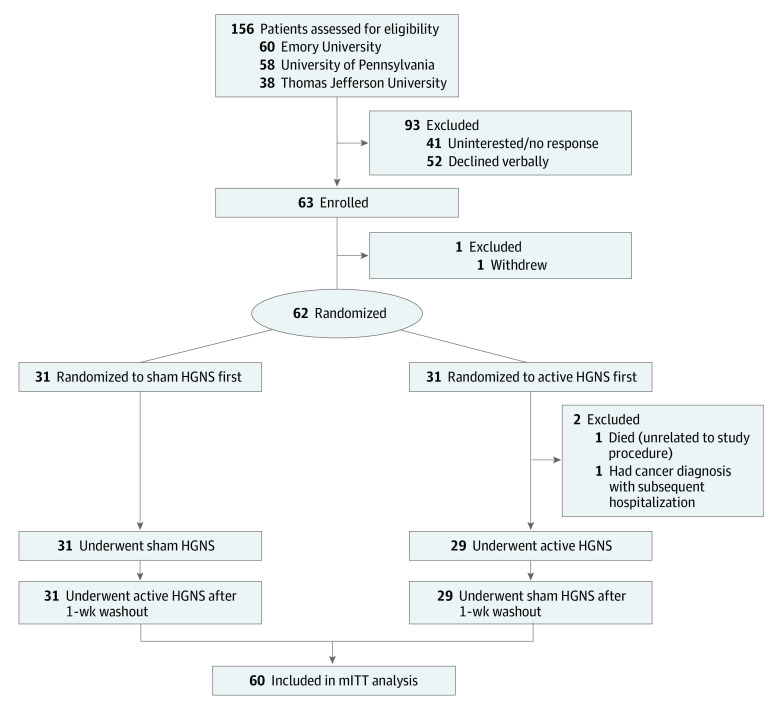

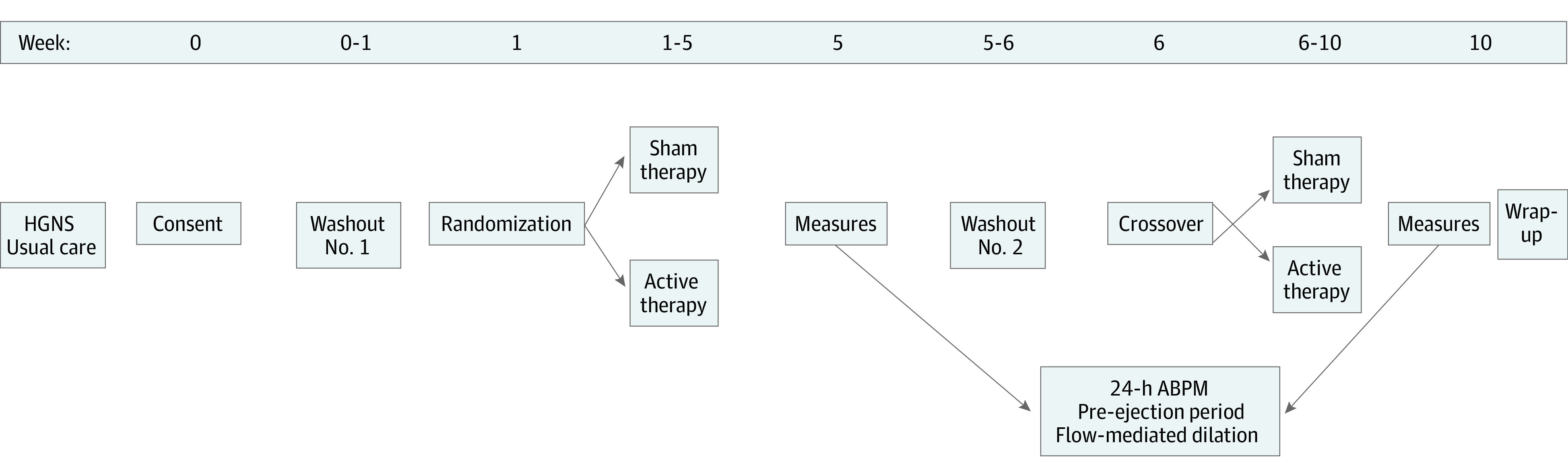

The Cardiovascular Endpoints for Obstructive Sleep Apnea With Twelfth Nerve Stimulation (CARDIOSA-12) study was a double-blind, sham-controlled, randomized crossover trial (protocol in Supplement 1).17 All participants and study team members, with the exception of the primary research coordinator, were blinded to treatment order to minimize potential bias in outcomes assessments (particularly for exploratory patient-reported outcomes [data not shown]). The total trial length was 10 weeks, including the two 1-week washout periods and two 4-week treatment periods (Figure 1). The local institutional review board approved the clinical trial protocol (Penn IRB No. 834158), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Additional details regarding participant eligibility criteria, randomization scheme and blinding, cardiovascular and sleep assessments, and power/sample size calculations are discussed below and in eMethods in Supplement 2, as well as in the previous methods publication.17 Participants self-identified race and ethnicity at study entry. Options regarding race and ethnicity were defined by technical data elements within the Epic Systems Electronic Health Record. Race and ethnicity were captured and studied because OSA and cardiovascular health demonstrate racial differences.

Figure 1. Study Flow.

ABPM indicates ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; HGNS, hypoglossal nerve stimulation.

There were 2 significant changes to the original study protocol that occurred in response to COVID-19–related challenges and transfer of the study from Emory University to the University of Pennsylvania in 2019. Microneurography and pulse wave velocity were no longer regularly performed due to an absence of available expertise. Additionally, to include participants with low therapeutic voltages (<1.0 V), an exclusion criterion was amended to use relative differences (≥30%) between active and sham therapy as opposed to absolute differences (≥0.5 V). This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Active and Sham Therapy HGNS Setting Determination

Active therapy was the voltage determined by the patient’s treating clinician prior to entering the trial. To determine sham therapy settings, in a reclined position, the participants were asked to keep their mouth open and breathe via the nose as stimulation was increased incrementally from 0.1 V until either (1) gross tongue motion was observed or (2) the participant reported sensation of tongue movement. This process was repeated twice, and the average value was used to define the sham HGNS threshold. The same pulse width, frequency, and electrode configuration were maintained between the participant’s active and sham thresholds.

Statistical Methods

Primary, Secondary, and Exploratory Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was mean 24-hour systolic blood pressure (SBP); other measures from ABPM were considered exploratory, including 24-hour diastolic blood pressure (DBP), as well as wake and sleep SBP and DBP. Cosecondary end points included mean PEP and FMD values.

Power and Sample Size

Historical data from an OSA cohort demonstrated an overall mean (SD) 24-hour SBP of 133 (11) mm Hg.26 Assuming this SD and an α of .05 for our primary outcome, 60 participants would provide at least 80% power to detect a mean difference of 4 mm Hg between active and sham therapy, a blood pressure reduction that is expected to significantly reduce stroke and heart disease mortality.27,28 For secondary end points, published PEP values in a cohort of patients with OSA have shown a mean (SD) of 93 (17.3) milliseconds,11 and published FMD values in a cohort of surgically treated patients with OSA have shown a mean (SD) of 5.2% (5.0%).29 Clinically important changes in PEP and FMD values are believed to be 10 milliseconds and approximately 50% increase (or a value of 2.6%, based on the observed mean), respectively. Based on these values and assuming an α of .025 (2-tailed) for our 2 secondary end points, a total of 32 and 38 patients were required to maintain at least 80% power for detecting these differences in PEP and FMD values, respectively. Thus, our sample of 60 patients was expected to provide good statistical power for evaluation of primary and cosecondary end points in this study.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are summarized using means and SDs, and categorical data are summarized using frequencies and percentages. Given the randomized crossover design, where each individual serves as their own control, statistical analyses comparing sham vs active therapy were performed using methods appropriate for paired data (eg, paired t tests for differences in continuous measures). To evaluate whether the effects of active therapy differed within specific subgroups of patients, we used linear regression models to compare differences between active and sham therapy separately among groups defined based on randomized therapy order (sham first vs active first), age (<70 vs ≥70 years), body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; <30 vs ≥30), hypertension (no vs yes), and sex (female vs male). When interpreting statistical significance of the findings, a P < .05 threshold was used for the primary end point (mean 24-hour SBP), and a P < .025 threshold was used for cosecondary end points (mean PEP and FMD values). A Hochberg step-up procedure was used to control type I error at 5% across multiple exploratory end points.30,31 Notably, results are presented with an emphasis on clinical significance of effect sizes and 95% CIs rather than focusing on strict interpretations of statistical significance.

Analysis Sets

Primary analyses were performed in a modified intention-to-treat (mITT) analysis set, defined as all randomized participants who completed both arms of the study. Of 62 randomized participants, 2 (3%) were excluded from the mITT analysis set; 1 participant died and 1 had a cancer diagnosis with subsequent hospitalization (Figure 2). In addition, as the primary goal of the study was to compare patients receiving sham (nontherapeutic) vs active (therapeutic) HGNS, we defined a per-protocol (PP) analysis set of individuals who exhibited a 50% or greater difference in improvement in apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) between the sham and active therapy arms. The AHI is the number of apneas (complete collapse of the airway) and hypopneas (partial collapse of the airway) per hour during sleep and is a measure of OSA disease severity. A higher AHI indicates worse disease severity. Analyses were repeated in the PP analysis set to understand the benefit of HGNS when patients were effectively treated (active) vs untreated (sham) as envisioned in the original protocol. Analyses were performed using Stata/SE, version 14.3 (StataCorp LLC), and SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Figure 2. CONSORT Diagram.

HGNS indicates hypoglossal nerve stimulation; mITT, modified intention-to-treat.

Results

The overall flow of participants is illustrated in Figure 2. Briefly, 156 patients were contacted, and 63 were subsequently enrolled. Sixty-two participants were randomized, with 60 completing the trial, constituting the mITT analysis set. Clinical characteristics of the primary mITT analysis set are presented in Table 132; similar data for the PP analysis set are presented in eTable 1 in Supplement 2. Randomized participants were older adults (mean [SD] age, 67.3 [9.9] years) and overweight (mean [SD] BMI, 28.7 [4.6]), and a majority were male individuals (38 [63%]). Of the 60 participants, 1 (2%) was Asian, 3 (5%) were Black, 1 (2%) was Hispanic, and 55 (92%) were White. Participants had severe OSA prior to HGNS implant, with a mean (SD) AHI of 33.1 (14.9) events/h. There was generally good covariate balance between those randomized to sham therapy first compared to those randomized to active therapy first (Table 1), with the exception that individuals randomized to active therapy first were more likely to be former smokers (18 [62%]), whereas those receiving sham therapy first were more frequently never smokers (18 [58%]). Among 58 individuals who responded to the question regarding blinding adequacy, 51 (87.9% [95% CI, 79.5%-96.3%]) correctly guessed their treatment order—considerably greater than the expected 50%.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Modified Intention-to-Treat Analysis Set.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 60) | Sham first (n = 31) | Active first (n = 29) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 22 (37) | 11 (36) | 11 (38) |

| Male | 38 (63) | 20 (64) | 18 (62) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 67.3 (9.9) | 67.1 (11.8) | 67.6 (7.5) |

| <70 y | 34 (57) | 16 (52) | 19 (62) |

| ≥70 y | 26 (43) | 15 (48) | 11 (38) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Black | 3 (5) | 0 | 3 (10) |

| Hispanic | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 |

| White | 55 (92) | 29 (94) | 26 (90) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.7 (4.6) | 27.9 (4.2) | 29.6 (4.9) |

| <30 | 36 (60) | 22 (71) | 14 (48) |

| ≥30 | 24 (40) | 9 (29) | 15 (52) |

| Diabetes | 15 (25) | 6 (19) | 9 (31) |

| Hypertension | 35 (58) | 19 (61) | 16 (55) |

| Receiving hypertension medications | 36 (60) | 19 (61) | 17 (59) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current | 6 (10) | 4 (13) | 2 (7) |

| Never | 27 (45) | 18 (58) | 9 (31) |

| Former | 27 (45) | 9 (29) | 18 (62) |

| Preimplant AHI, mean (SD), events/h | 33.1 (14.9) | 31.9 (14.9) | 34.4 (15.0) |

| HGNS configurationa | |||

| +/−/+ | 45 (75) | 23 (74) | 22 (76) |

| −/−/− | 3 (5) | 0 | 3 (10) |

| −/○/− | 5 (8) | 3 (10) | 2 (7) |

| ○/−/○ | 7 (12) | 5 (16) | 2 (7) |

Abbreviations: AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; HGNS, hypoglossal nerve stimulation.

The HGNS device can be programmed to have a bipolar (+/−/+) configuration or 1 of 3 monopolar configurations (−/−/−, −/o/−, o/−/o). The different configurations may differ in their current penetration and electric field strength.32

AHI Response and Treatment-Related Metrics

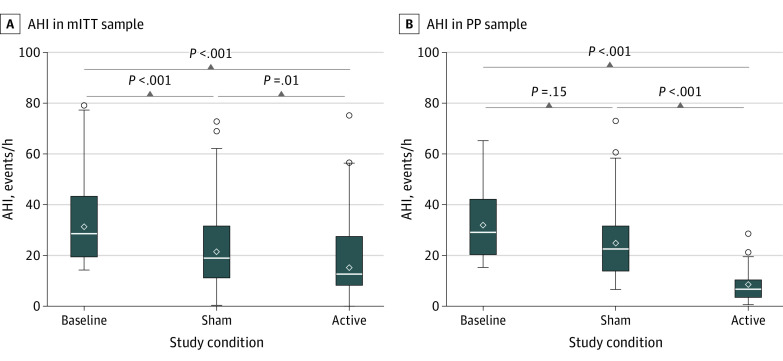

As shown in Figure 3, compared to the preoperative baseline mean (SD) of 33.1 (14.9) events/h, mean (SD) AHI decreased to 23.0 (15.6) events/h with sham therapy and 18.1 (14.8) events/h with active therapy, resulting in a 4.9-events/h (95% CI, 1.0-8.8 events/h) greater reduction with active vs sham therapy (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Additional details of treatment-related characteristics and AHI response are presented in eTable 2 in Supplement 2. Among the mITT sample, voltage was increased by 1.01 (95% CI, 0.88-1.14) V from a mean (SD) of 0.91 (0.45) V with sham therapy to 1.92 (0.76) V with active therapy. Participants demonstrated a 1.4-hour (95% CI, 1.04-1.84 hours) greater adherence to sham therapy (mean [SD], 8.19 [1.22] hours/night) than active therapy (mean [SD], 6.80 [1.74] hours/night).

Figure 3. Comparison of Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) Across Study Conditions in Modified Intention-to-Treat (mITT) and Per-Protocol (PP) Analysis Sets.

Box and whisker plots compare AHI across study conditions: baseline or preimplant AHI, sham AHI, and active AHI in the mITT analysis (n = 60) (A) and the PP analysis (n = 20) (B). The boxes represent the IQR defined as 25th to 75th quartiles or the middle 50% of data. The upper and lower whiskers represent 1.5 × IQR above the 75th percentile and 1.5 × IQR below the 25th percentile, respectively, or the maximum/minimum values if they fall within this range. Any open circles beyond the whiskers are possible outliers. The horizontal line within the boxes represents the median value, and the open diamond within the boxes represents the mean value.

Thirty-nine patients (65%) achieved an AHI less than 20 events/h with active treatment, whereas 20 patients (33%) met our PP criteria of at least a 50% reduction in AHI between sham and active therapy. Similar differences between sham and active therapy in voltage (1.13 [95% CI, 0.91-1.35] V) and daily adherence (−1.0 [95% CI, −1.9 to −0.03] hours) were observed in the PP analysis set (eTable 2 in Supplement 2), although by design there was a much larger reduction in AHI of 17.9 (95% CI, 11.7-24.0) events/h with active therapy.

mITT Analysis

Results of primary analyses comparing sham and active treatment within the mITT analysis set are shown in Table 2. There were no meaningful differences observed in 24-hour SBP between active and sham therapy, with a mean change with active therapy of only −0.18 (95% CI, −2.21 to 1.84) mm Hg (Table 2). Similar to the primary end point, no meaningful differences between sham and active therapy were observed in mean PEP (mean change with active therapy, 0.11 [95% CI, −5.43 to 5.66] milliseconds) or FMD (mean change on active therapy, −0.17% [95% CI, −1.88% to 1.54%]) values (Table 2). Comparisons of additional measurements obtained from ABPM did not demonstrate any meaningful differences between sham and active treatment within the mITT analysis set (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparisons of Outcomes During Sham and Active Therapy Among Modified Intention-to-Treat (mITT) and Per-Protocol (PP) Analysis Sets.

| Clinical measures | Sham | Active | Differencea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean (SD) | No. | Mean (SD) | No. | Mean (95% CI) | |

| mITT analysis set | ||||||

| ABPM measures,b mm Hg | ||||||

| 24-h SBP | 60 | 123.0 (10.8) | 60 | 122.8 (11.8) | 60 | −0.18 (−2.21 to 1.84) |

| 24-h DBP | 60 | 72.1 (7.0) | 60 | 71.9 (7.8) | 60 | −0.22 (−1.27 to 0.83) |

| Wake SBP | 60 | 126.9 (11.0) | 60 | 126.7 (12.4) | 60 | −0.23 (−2.66 to 2.19) |

| Wake DBP | 60 | 75.1 (7.6) | 60 | 74.7 (8.3) | 60 | −0.42 (−1.72 to 0.89) |

| Sleep SBP | 60 | 114.8 (14.0) | 60 | 115.0 (14.6) | 60 | 0.15 (−2.33 to 2.63) |

| Sleep DBP | 60 | 66.3 (8.7) | 60 | 65.8 (9.1) | 60 | −0.43 (−1.97 to 1.11) |

| PEP,c ms | 50 | 105.4 (16.8) | 51 | 105.7 (16.5) | 50 | 0.11 (−5.43 to 5.66) |

| FMD,c % | 42 | 6.79 (5.03) | 43 | 6.65 (4.38) | 40 | −0.17 (−1.88 to 1.54) |

| PP analysis set | ||||||

| ABPM measures,b mm Hg | ||||||

| 24-h SBP | 20 | 120.1 (11.0) | 20 | 118.9 (10.5) | 20 | −1.20 (−3.49 to 1.09) |

| 24-h DBP | 20 | 69.4 (7.2) | 20 | 68.3 (6.4) | 20 | −1.10 (−2.26 to 0.06) |

| Wake SBP | 20 | 123.7 (12.0) | 20 | 121.7 (12.1) | 20 | −2.00 (−4.71 to 0.71) |

| Wake DBP | 20 | 72.9 (8.6) | 20 | 70.9 (7.8) | 20 | −2.00 (−3.71 to −0.29) |

| Sleep SBP | 20 | 111.5 (12.8) | 20 | 111.9 (12.2) | 20 | 0.40 (−3.08 to 3.88) |

| Sleep DBP | 20 | 62.1 (7.8) | 20 | 62.3 (6.4) | 20 | 0.20 (−1.83 to 2.23) |

| PEP,c ms | 16 | 105.9 (17.3) | 17 | 108.2 (16.4) | 16 | 1.93 (−6.24 to 10.10) |

| FMD,c % | 16 | 6.50 (3.42) | 15 | 7.41 (4.64) | 15 | 0.94 (−1.14 to 3.02) |

Abbreviations: ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FMD, flow-mediated dilation; PEP, pre-ejection period; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Difference calculated as active minus sham.

Decreases with active therapy considered positive treatment benefit.

Increases with active therapy considered positive treatment benefit.

PP Analyses

In addition to primary analyses in the mITT analysis set, we repeated analyses within a PP analysis set defined by a reduction in AHI between sham and active treatment of at least 50% (Table 2). While meaningful differences were again not observed for primary (mean 24-hour SBP) or cosecondary (mean PEP and FMD values) end points, effect sizes were larger in this selected sample. While none of the exploratory end points remained statistically significant after consideration of multiple comparisons, a potentially clinically important improvement in wake DBP of 2.00 (95% CI, 0.29-3.71) mm Hg was observed.

Subgroup Analyses

Differences between active and sham therapy within clinically important patient subgroups were investigated in the mITT (eTable 3 in Supplement 2) and PP (eTable 4 in Supplement 2) analysis sets. In general, we did not observe evidence that the effects of active HGNS differed based on age, BMI, sex, or hypertension status. Notably, results comparing those randomized to active first vs sham first did not show evidence of potential carryover effects from the 1-week washout period, with most outcomes showing no differential effects based on order of therapy, and PEP showing a larger increase with active HGNS compared to sham among those who had active HGNS (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

In this crossover randomized clinical trial, mean 24-hour SBP was not significantly different between sham and active HGNS therapy. Similarly, PEP and FMD values were comparable when receiving active HGNS vs sham HGNS. Within a PP analysis restricted to patients who demonstrated a meaningful improvement in AHI from sham to active HGNS, effect sizes were larger and consistent with benefits of active therapy for all cardiovascular outcomes when compared to the primary mITT analysis, although results did not achieve statistical significance.

While HGNS represents a fairly new surgical approach to OSA without robust cardiovascular outcome data, the effect of traditional OSA surgical treatments on cardiometabolic parameters has been previously studied. Halle et al33 performed a comprehensive systematic review of surgical treatments for OSA, including airway bypass surgery, skeletal surgery, and soft tissue surgery (eg, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty), on cardiovascular end points. Studies investigating the effects of tracheostomy and maxillomandibular advancement demonstrated significant reductions in blood pressure; however, they lacked a control group, were retrospective in nature, and used single in-office blood pressure measurements.33,34,35,36 Regarding soft tissue surgery, 8 studies evaluated systemic blood pressure as a primary or secondary outcome. In a study by Yu et al, 24-hour ABPM revealed a significant reduction in nocturnal, but not diurnal, blood pressure.33,37 While this study used 24-hour ABPM and had a large effect size, the findings are coincident with significant weight loss as the main confounder. Overall, the published literature evaluating cardiovascular end points of surgical treatment for OSA is limited, of low level evidence (level 3 and 4), and hampered by inherent challenges associated with surgical trial design.

A randomized, sham-controlled trial design represents the gold standard for evaluating efficacy of new medical therapies.38 The on/off functionality of the HGNS system permits a sham-controlled component, which is unique compared to traditional surgical trials. While the published literature examining cardiovascular end points from PAP therapy is well studied, the published literature in sham-controlled OSA nonsurgical treatment trial design is fairly limited. Additionally, sham-controlled arms offer the benefit of reducing bias in the assessment of the untreated response, particularly for the assessment of subjective outcomes (ie, sleep-related patient-reported outcomes), which were an exploratory outcome in this trial that will be described elsewhere.39 In a randomized, double-blind, parallel group trial of 340 patients with moderate-severe OSA assigned to either continuous PAP therapy (CPAP) or sham CPAP, Durán-Cantolla et al26 found that CPAP produced a statistically significant, but not clinically relevant, reduction in blood pressure (−1.5 mm Hg, P = .01). Two studies evaluated the effect of CPAP on blood pressure through a randomized, sham-controlled crossover trial design. Robinson et al40 randomized 35 patients with OSA to 1 month of CPAP followed by 1 month of subtherapeutic CPAP (1 cm H2O) or vice versa and reported no overall significant difference between groups in mean 24-hour blood pressure (−0.74 mm Hg, P = .71). Hoyos et al41 performed a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled crossover trial with 38 patients with OSA and found that compared to sham CPAP (0.5 cm H2O), CPAP significantly reduced SBP (−4.1 mm Hg, P = .003). This study is of particular interest, being the first (to our knowledge) to demonstrate a positive CPAP effect through a sham-controlled component, as well as sharing similarities (eg, trial design, participant characteristics, inclusion criteria) with our own study; however, it is unclear why such a strong signal was detected. Regarding oral appliance therapy, there are 2 randomized, sham-controlled parallel-group trials that evaluated efficacy of oral appliance therapy on blood pressure in patients with OSA, both of which did not find significant reductions in 24-hour blood pressure.42,43 A randomized, controlled crossover trial of 61 patients with OSA conducted by Gotsopoulous et al44 reported a modest yet statistically significant difference in mean 24-hour DBP, but not SBP, in patients fitted with a mandibular advancement splint compared to a sham appliance (78.0 mm Hg vs 76.4 mm Hg, P = .001).

When including a sham control arm, future studies should be meticulous when defining sham component criteria in an effort to minimize partially therapeutic effects, which likely confound study findings. In this regard, a chief limitation of the present study was the apparent partially therapeutic effect of sham HGNS; compared to preoperative baseline, AHI decreased by about 10 events/h with sham therapy and 15 events/h with active therapy. Sham HGNS voltages were determined from patient sensation and investigator observation of gross tongue motion, suggesting partial anatomic effects on the airway even at minimal HGNS voltages. To mitigate this effect, we performed a secondary PP analysis within a subset of patients (n = 20) with significant improvement in AHI between active therapy and sham therapy; while effects were increased, this sample had diminished analytic power. In this regard, it is important to recognize that recruitment of patients with dramatic symptomatic improvement with HGNS was challenging, as these patients declined to be without treatment for 6 out of 10 weeks as required by the study. This is consistent with the problem many trials face with recruiting patients with dramatic responses to therapy, which may bias the study findings here and elsewhere. The sham HGNS arm also resulted in 1.4 more hours of nightly usage compared to active therapy, likely due to reduced sleep time from discomfort with active therapy (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2), or in some cases, sham therapy was inadvertently left on after the patient awoke (some participants disclosed such incidents to our study team). Supplementary analyses suggest that these differences in adherence were not associated with outcomes in our sample (eTables 5 and 6 in Supplement 2).

Limitations and Strengths

As the first (to our knowledge) sham-controlled HGNS trial, other anticipated limitations deserve mention. First, HGNS therapy is appropriate for a select subset of patients with OSA, thereby limiting generalizability of these study findings. However, higher AHI was strongly associated with greater blood pressure across all ABPM measurements in our sample (eTable 6 in Supplement 2), a finding consistent across OSA studies. As our sample size was determined to ensure good power to detect a 4-mm Hg decrease in blood pressure, the trial was likely underpowered to identify the smaller effects that have more recently been described in meta-analyses of PAP therapy,5 but should have had excellent power to detect the larger responses recently reported for surgical therapies.21 Certain baseline outcome measurements (ABPM, PEP, FMD) were not obtained because they are not routinely performed clinically. While baseline AHI was obtained from patient medical records, there was lack of standardization in sleep study type and hypopnea definitions. Given that our sham therapy levels may have been at least partially therapeutic in most participants, future trials should consider obtaining additional standardized baseline measurements (eg, blood pressure, AHI) prior to HGNS implantation or without HGNS stimulation. As Schwarz et al6 noted that a 2-week washout period returned blood pressure values to baseline measures, it is possible that the 1-week washout period in our trial may be considered insufficient due to potential for carryover effect. However, the Stimulation Therapy for Apnea Reduction (STAR) trial was designed with a 1-week withdrawal, which resulted in a subsequent return of AHI to baseline status.45 Moreover, our analyses comparing response in patients randomized to active therapy first vs those receiving sham therapy first did not indicate any carryover effects. Due to ethical concerns, we excluded severely excessively sleepy patients with OSA (defined as having fallen asleep while driving resulting in a near-miss or traffic collision within 1 year prior to implant); as prior studies have suggested that the blood pressure benefits of therapy are stronger in excessively sleepy patients,40,46 this may have influenced our ability to identify significant benefits of active therapy. Alternative designs that allow estimation of causal treatment effects from observational data may be required to include these patients in future studies.47 More generally, heterogeneity in the severity of hypoxia and symptom presentation (eg, excessive sleepiness) among patients with OSA has been shown to influence both cardiovascular risk and response to PAP therapy48,49 and could have influenced the results of our study. Future studies should further investigate the effect of OSA subtypes on HGNS-related outcomes. Although patients were instructed to simulate similar environments during their cardiovascular assessments (ie, 24-hour ABPM; WatchPAT home sleep apnea test [Itamar Medical]) during sham and active HGNS therapy, ambulatory blood pressure monitors were not necessarily used on the same day of the week for each patient, which represents another possible source of bias. Patients’ active therapy parameters (voltage, pulse width, frequency, electrode configuration) were previously determined by their treating clinician, which may not represent the optimal stimulation parameters at the time of trial entry. While the randomized order of participants was meant to ensure blinding to active vs sham therapy, it was largely ineffective, as 88% of participants correctly guessed their treatment order. Our study sample was also greater than 90% White race, limiting racial and ethnic generalizability. In an effort to broaden generalizability, we included normotensive patients (42%), in whom the benefit of blood pressure reduction is unclear. Finally, the institutional transfer of the principal investigator amid the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in discontinuation of the muscle sympathetic nerve activity and peripheral arterial stiffness outcome measures due to resource constraints.

Our study also bears several strengths, particularly related to the ability to include a sham treatment arm, an opportunity rarely available in surgical trials. By randomizing patients to sham or active therapy first, we were able to control for possible order effects, which mitigates possible bias from possible carryover effects from active therapy given the relatively short 1-week washout period. The use of a crossover trial allowed participants to serve as their own control participants, reducing the effect of participant-level variation seen in parallel group trials. In terms of generalizability, our trial included participants from 3 different institutions and a sizeable female sample (37%). While polysomnography may be considered the gold standard for sleep apnea testing, home sleep apnea testing was implemented to minimize patient burden by reducing the number of onsite visits and to provide a more representative night of sleep in the patient’s standard home environment. Furthermore, the use of Inspire Cloud (Inspire Medical Systems) provided nightly adherence monitoring data throughout the trial, critically important to ensure therapy usage during the nights of ABPM and home sleep apnea testing.

Ultimately, there are several important lessons that should be gleaned for future sham-controlled HGNS trials. First, therapy voltages that result in gross tongue motion (or patient perception of motion) provide a significant therapeutic effect and do not reliably blind participants; therefore, sham therapy should be set at the lowest possible setting (0.1 V), as was recently reported in the Effect of Upper Airway Stimulation in Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea (EFFECT) study.50 Second, to detect a sham treatment effect, baseline (untreated) values for AHI, sleep-related patient-reported outcomes, and study outcome variables should be collected, despite the practical challenges of an additional washout period. Third, greater incentives must be provided to recruit participants currently doing well with HGNS therapy, as these patients are less willing to enroll in trials but are necessary to understand the full potential of HGNS, leading to greater understanding of both physiologic mechanisms and consequences of treatment. Finally, sleep logs should be used in concert with therapy adherence monitoring in the event that sham therapy extends beyond the participant’s sleep period.

Conclusions

CARDIOSA-12 did not demonstrate differences in 24-hour blood pressure or sympathetic or vascular measures over a 10-week randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled, crossover trial. Based on important insights from this study, future trials can and should be better designed to examine meaningful differences in short-term and long-term outcomes in patients undergoing HGNS therapy for OSA.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Ambulatory Blood Pressure Output

eFigure 2. Pre-ejection Period Output

eFigure 3. Flow-mediated Dilation Output

eFigure 4. Example of Inspire Cloud Data in a Study Subject

eTable 1. Demographics of the Per Protocol Analysis Set

eTable 2. Comparisons of treatment characteristics during sham and active therapy

eTable 3. Comparisons of outcomes in mITT analysis set stratified by relevant subgroups

eTable 4. Comparisons of outcomes in PP analysis set stratified by relevant subgroups

eTable 5. Correlations between changes in outcomes in changes in treatment-related measures

eTable 6. Correlations between outcomes and treatment-related measures during sham and active therapy

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Malhotra A, White DP. Obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet. 2002;360(9328):237-245. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09464-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1046-1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71141-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Punjabi NM, Caffo BS, Goodwin JL, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and mortality: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(9):1006-1014. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu X, Fan J, Chen S, Yin Y, Zrenner B. The role of continuous positive airway pressure in blood pressure control for patients with obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2015;17(3):215-222. doi: 10.1111/jch.12472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwarz EI, Schlatzer C, Rossi VA, Stradling JR, Kohler M. Effect of CPAP withdrawal on BP in OSA: data from three randomized controlled trials. Chest. 2016;150(6):1202-1210. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waradekar NV, Sinoway LI, Zwillich CW, Leuenberger UA. Influence of treatment on muscle sympathetic nerve activity in sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(4 pt 1):1333-1338. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.4.8616563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Usui K, Bradley TD, Spaak J, et al. Inhibition of awake sympathetic nerve activity of heart failure patients with obstructive sleep apnea by nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(12):2008-2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imadojemu VA, Mawji Z, Kunselman A, Gray KS, Hogeman CS, Leuenberger UA. Sympathetic chemoreflex responses in obstructive sleep apnea and effects of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Chest. 2007;131(5):1406-1413. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherwood A, Allen MT, Obrist PA, Langer AW. Evaluation of beta-adrenergic influences on cardiovascular and metabolic adjustments to physical and psychological stress. Psychophysiology. 1986;23(1):89-104. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00602.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelesen RA, Dimsdale JE, Mills PJ, Clausen JL, Ziegler MG, Ancoli-Israel S. Altered cardiac contractility in sleep apnea. Sleep. 1996;19(2):139-144. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.2.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung S, Yoon IY, Lee CH, Kim JW. The association of nocturnal hypoxemia with arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction in male patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Respiration. 2010;79(5):363-369. doi: 10.1159/000228905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nieto FJ, Herrington DM, Redline S, Benjamin EJ, Robbins JA. Sleep apnea and markers of vascular endothelial function in a large community sample of older adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(3):354-360. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-756OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu H, Wang Y, Guan J, Yi H, Yin S. Effect of CPAP on endothelial function in subjects with obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Respir Care. 2015;60(5):749-755. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korcarz CE, Benca R, Barnet JH, Stein JH. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in young and middle-aged adults: effects of positive airway pressure and compliance on arterial stiffness, endothelial function, and cardiac hemodynamics. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(4):e002930. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rana D, Torrilus C, Ahmad W, Okam NA, Fatima T, Jahan N. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular morbidities: a review article. Cureus. 2020;12(9):e10424. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dedhia RC, Quyyumi AA, Park J, Shah AJ, Strollo PJ, Bliwise DL. Cardiovascular endpoints for obstructive sleep apnea with twelfth cranial nerve stimulation (CARDIOSA-12): rationale and methods. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(11):2635-2643. doi: 10.1002/lary.27284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotenberg BW, Murariu D, Pang KP. Trends in CPAP adherence over twenty years of data collection: a flattened curve. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;45(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s40463-016-0156-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weaver TE, Grunstein RR. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):173-178. doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-119MG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, et al. Objective measurement of patterns of nasal CPAP use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147(4):887-895. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.4.887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang KT, Yeh TH, Ko JY, Lee CH, Lin MT, Hsu WC. Effect of sleep surgery on blood pressure in adults with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;62:101590. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bratton DJ, Gaisl T, Wons AM, Kohler M. CPAP vs mandibular advancement devices and blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314(21):2280-2293. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodson BT, Soose RJ, Gillespie MB, et al. ; STAR Trial Investigators . Three-year outcomes of cranial nerve stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea: the STAR trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154(1):181-188. doi: 10.1177/0194599815616618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dedhia RC, Shah AJ, Bliwise DL, et al. Hypoglossal nerve stimulation and heart rate variability: analysis of STAR trial responders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160(1):165-171. doi: 10.1177/0194599818800284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikeda AK, Li Q, Quyuumi AA, Dedhia RC. Hypoglossal nerve stimulation therapy on peripheral arterial tonometry in obstructive sleep apnea: a pilot study. Sleep Breath. 2019;23(1):153-160. doi: 10.1007/s11325-018-1676-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durán-Cantolla J, Aizpuru F, Montserrat JM, et al. ; Spanish Sleep and Breathing Group . Continuous positive airway pressure as treatment for systemic hypertension in people with obstructive sleep apnoea: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341(1):c5991. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R; Prospective Studies Collaboration . Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9349):1903-1913. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11911-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease: part 1, prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990;335(8692):765-774. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90878-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee MY, Lin CC, Lee KS, et al. Effect of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty on endothelial function in obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(3):369-374. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75(4):800-802. doi: 10.1093/biomet/75.4.800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang Y, Hsu JC. Hochberg’s step-up method: cutting corners off Holm’s step-down method. Biometrika. 2007;94:965-975. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asm067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heiser C. Advanced titration to treat a floppy epiglottis in selective upper airway stimulation. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(suppl 7):S22-S24. doi: 10.1002/lary.26118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halle TR, Oh MS, Collop NA, Quyyumi AA, Bliwise DL, Dedhia RC. Surgical treatment of OSA on cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review. Chest. 2017;152(6):1214-1229. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prinsell JR. Maxillomandibular advancement surgery in a site-specific treatment approach for obstructive sleep apnea in 50 consecutive patients. Chest. 1999;116(6):1519-1529. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.6.1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyd SB, Walters AS, Waite P, Harding SM, Song Y. Long-term effectiveness and safety of maxillomandibular advancement for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(7):699-708. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Islam S, Taylor CJ, Ormiston IW. Effects of maxillomandibular advancement on systemic blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;53(1):34-38. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu S, Liu F, Wang Q, et al. Effect of revised UPPP surgery on ambulatory BP in sleep apnea patients with hypertension and oropharyngeal obstruction. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2010;32(1):49-53. doi: 10.3109/10641960902993079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fudim M, Ali-Ahmed F, Patel MR, Sobotka PA. Sham trials: benefits and risks for cardiovascular research and patients. Lancet. 2019;393(10186):2104-2106. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31120-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutherland ER. Sham procedure versus usual care as the control in clinical trials of devices: which is better? Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4(7):574-576. doi: 10.1513/pats.200707-090JK [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson GV, Smith DM, Langford BA, Davies RJO, Stradling JR. Continuous positive airway pressure does not reduce blood pressure in nonsleepy hypertensive OSA patients. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(6):1229-1235. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00062805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoyos CM, Yee BJ, Wong KK, Grunstein RR, Phillips CL. Treatment of sleep apnea with CPAP lowers central and peripheral blood pressure independent of the time-of-day: a randomized controlled study. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(10):1222-1228. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpv023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andrén A, Hedberg P, Walker-Engström ML, Wahlén P, Tegelberg A. Effects of treatment with oral appliance on 24-h blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension: a randomized clinical trial. Sleep Breath. 2013;17(2):705-712. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0746-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rietz H, Franklin KA, Carlberg B, Sahlin C, Marklund M. Nocturnal blood pressure is reduced by a mandibular advancement device for sleep apnea in women: findings from secondary analyses of a randomized trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(13):e008642. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gotsopoulos H, Kelly JJ, Cistulli PA. Oral appliance therapy reduces blood pressure in obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized, controlled trial. Sleep. 2004;27(5):934-941. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.5.934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strollo PJJ Jr, Soose RJ, Maurer JT, et al. ; STAR Trial Group . Upper-airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(2):139-149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barbé F, Mayoralas LR, Duran J, et al. Treatment with continuous positive airway pressure is not effective in patients with sleep apnea but no daytime sleepiness. a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(11):1015-1023. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-11-200106050-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pack AI, Magalang UJ, Singh B, Kuna ST, Keenan BT, Maislin G. Randomized clinical trials of cardiovascular disease in obstructive sleep apnea: understanding and overcoming bias. Sleep. 2021;44(2):zsaa229. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pack AI. Unmasking heterogeneity of sleep apnea. Sleep Med Clin. 2023;18(3):293-299. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2023.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Redline S, Azarbarzin A, Peker Y. Obstructive sleep apnoea heterogeneity and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20(8):560-573. doi: 10.1038/s41569-023-00846-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heiser C, Steffen A, Hofauer B, et al. Effect of upper airway stimulation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (EFFECT): a randomized controlled crossover trial. J Clin Med. 2021;10(13):2880. doi: 10.3390/jcm10132880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Ambulatory Blood Pressure Output

eFigure 2. Pre-ejection Period Output

eFigure 3. Flow-mediated Dilation Output

eFigure 4. Example of Inspire Cloud Data in a Study Subject

eTable 1. Demographics of the Per Protocol Analysis Set

eTable 2. Comparisons of treatment characteristics during sham and active therapy

eTable 3. Comparisons of outcomes in mITT analysis set stratified by relevant subgroups

eTable 4. Comparisons of outcomes in PP analysis set stratified by relevant subgroups

eTable 5. Correlations between changes in outcomes in changes in treatment-related measures

eTable 6. Correlations between outcomes and treatment-related measures during sham and active therapy

Data Sharing Statement