Abstract

Objective

Literature on the genotypic spectrum of Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome (IESS) in children is scarce in developing countries. This multicentre collaboration evaluated the genotypic and phenotypic landscape of genetic IESS in Indian children.

Methods

Between January 2021 and June 2022, this cross‐sectional study was conducted at six centers in India. Children with genetically confirmed IESS, without definite structural‐genetic and structural‐metabolic etiology, were recruited and underwent detailed in‐person assessment for phenotypic characterization. The multicentric data on the genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of genetic IESS were collated and analyzed.

Results

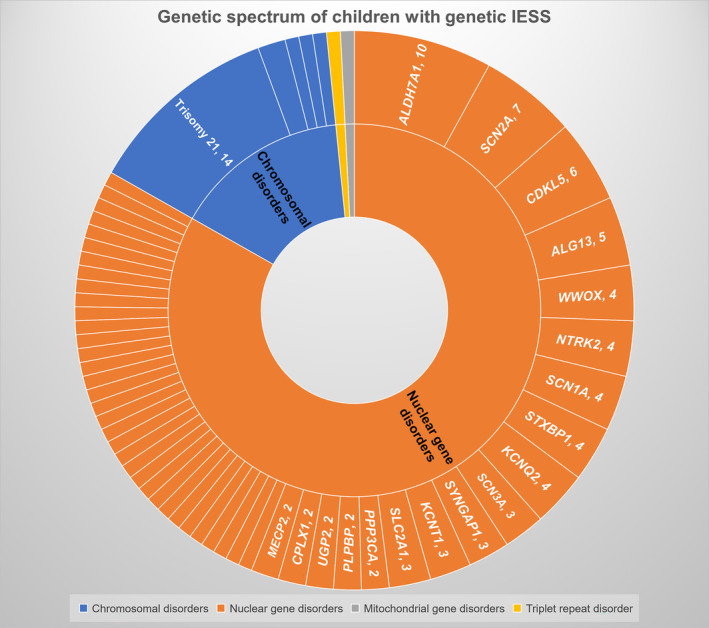

Of 124 probands (60% boys, history of consanguinity in 15%) with genetic IESS, 105 had single gene disorders (104 nuclear and one mitochondrial), including one with concurrent triple repeat disorder (fragile X syndrome), and 19 had chromosomal disorders. Of 105 single gene disorders, 51 individual genes (92 variants including 25 novel) were identified. Nearly 85% of children with monogenic nuclear disorders had autosomal inheritance (dominant‐55.2%, recessive‐14.2%), while the rest had X‐linked inheritance. Underlying chromosomal disorders included trisomy 21 (n = 14), Xq28 duplication (n = 2), and others (n = 3). Trisomy 21 (n = 14), ALDH7A1 (n = 10), SCN2A (n = 7), CDKL5 (n = 6), ALG13 (n = 5), KCNQ2 (n = 4), STXBP1 (n = 4), SCN1A (n = 4), NTRK2 (n = 4), and WWOX (n = 4) were the dominant single gene causes of genetic IESS. The median age at the onset of epileptic spasms (ES) and establishment of genetic diagnosis was 5 and 12 months, respectively. Pre‐existing developmental delay (94.3%), early age at onset of ES (<6 months; 86.2%), central hypotonia (81.4%), facial dysmorphism (70.1%), microcephaly (77.4%), movement disorders (45.9%) and autistic features (42.7%) were remarkable clinical findings. Seizures other than epileptic spasms were observed in 83 children (66.9%). Pre‐existing epilepsy syndrome was identified in 21 (16.9%). Nearly 60% had an initial response to hormonal therapy.

Significance

Our study highlights a heterogenous genetic landscape and phenotypic pleiotropy in children with genetic IESS.

Keywords: developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, genetic epileptic spasms, genetic infantile spasms, genetic West

Key points.

Of 124 with genetic IESS, 105 had single gene disorders (104 nuclear and one mitochondrial), including one with concurrent triple repeat disorder (fragile X syndrome), and 19 had chromosomal disorders.

Trisomy 21, ALDH7A1, SCN2A, CDKL5, and ALG13 were the common causes of genetic IESS in this study.

Pre‐existing developmental delay, early age at onset of ES (<6mo), central hypotonia, facial dysmorphism, microcephaly, movement disorders, and autistic features were remarkable clinical findings.

1. INTRODUCTION

Infantile epileptic spasms syndrome (IESS) is characterized by the onset of epileptic spasms (ES) in the 1‐24 months age group along with abnormal interictal electroencephalogram (classically hypsarrhythmia or other epileptiform abnormalities) and temporally associated developmental slowing. 1 Although the incidence of IESS is estimated to be 6.7 cases per 10 000 live births, it is one of the commonest causes of developmental and epileptic encephalopathy in infancy. 2 , 3 , 4 The etiologies of IESS are diverse and include genetic, structural, metabolic, infectious, immune, unknown, or a combination of the above. 5 , 6 , 7

With the advent of genetic testing, the proportion of children with defined genetic causes for IESS is increasing. It is well understood now that within the genetic subgroup, implicated genes are widely heterogeneous. 5 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 However, the literature on the novel genetic variations underlying IESS is mostly available from the developed Western countries through funded multinational consortia, such as the Epi4K consortium, 8 which is skewed toward these countries and does not represent the global genetic landscape of IESS.

Overall, there is a paucity of literature on genotype–phenotype correlates of ‘unknown‐etiology’ IESS from developing countries, as many children remain incompletely investigated. 18 , 19 Therefore, exploring the same in developing countries is the need of the hour, especially in the era of precision‐based medicine. Hence, scrutinizing the genetic determinants of IESS to better understand its pathogenesis, epidemiological aspects in a specific geographical region, any genotype–phenotype correlations, and any therapeutic or prognostic implications is of utmost importance. Therefore, our study aimed to address this knowledge gap by exploring the genetic profile of IESS, focused exclusively on unexplained IESS without known definite structural etiology, with objectives of genotypic and phenotypic characterization and determination of any detectable genotype–phenotype association.

2. METHODS

This cross‐sectional, multicentre study was conducted at a tertiary‐care center in North India in collaboration with five other pediatric centers across India over 18 months (Jan 2021‐June 2022).

2.1. Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patients consent

The study was initiated after approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee and Institute Collaborative Research Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the children who participated in the study. The Department Review Board also approved the manuscript.

2.2. Study subjects

IESS, for the purpose of the study, was defined as a constellation of infantile‐onset (2 months‐2 years) epileptic spasms and classical or modified hypsarrhythmia on EEG with or without developmental delay or regression.

Recently diagnosed or under follow‐up children with a prior diagnosis of genetic IESS, tested between January 2018 and June 2022, attending pediatric neurology services of any of the participating centers were included. For the purpose of the current study, genetic IESS was defined as “children with IESS who had a genetic etiology confirmed by genetic tests like next‐generation sequencing, Sanger sequencing, karyotyping, chromosomal microarray, triplet repeat polymerase chain reaction, or methylation‐specific MLPA”. The variant classification was done as per the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) 2015 recommendations, and only children with confirmed pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants were included. 20 Children with known structural‐genetic (like neurofibromatosis‐1, tuberous sclerosis complex, structural malformations such as Miller‐Dieker syndrome, ARX, TUBA1A, TUB4A, etc.) and structural neurometabolic etiologies (like glutaric aciduria type 1, Leigh syndrome, sulfite oxidase deficiency, etc.) were excluded.

2.3. Methodology

All the included children underwent detailed in‐person assessment at the respective center they followed up with, except those who could not come for follow‐up or had expired. These exceptions underwent telephonic assessment and retrospective chart review. A predesigned structured proforma was used to capture the clinical details, details of investigations (including neuroimaging and genetic analysis), and management at each center. The completed study proforma and genetic report details were shared with the principal investigator in Microsoft Excel by electronic mail after anonymization.

2.4. Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was genotypic particulars of children with genetic IESS, and secondary outcome measures included phenotypic characterization of these children as assessed by age at onset of ES, the severity of ES, pre‐existing developmental delay, comorbid movement disorder and autistic features, neuroimaging findings, electroencephalogram findings, treatment response, cessation of spasms, relapse, etc. Response to treatment was defined by a complete clinical cessation of epileptic spasms lasting for at least 4‐week duration during the course of therapy.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The multicentric data were collated and analyzed using Microsoft spreadsheet and SPSS. Descriptive statistics were performed as applicable. The categorical variables were presented as the frequency with percentages, while the median (IQR) /mean (SD) were used to present summary figures for continuous variables.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Cohort recruitment

A total of 124 children with genetic IESS were recruited from six tertiary‐care pediatric neurology centers in India, including the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh (n = 45), Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health, Bengaluru (n = 35), Christian Medical College, Vellore (n = 23), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh (n = 15), Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University Medical College, Pune (n = 3), and Royal Institute of Child Neuroscience, Ahmedabad (n = 3). All children [67 boys; median age at enrolment (Q1, Q3): 18 (8, 39) months] were evaluated by a pediatric neurologist for phenotypic characterization and data acquisition. The median age (Q1, Q3) at confirmation of genetic diagnosis was 12 (8, 27) months.

3.2. Genotypic landscape

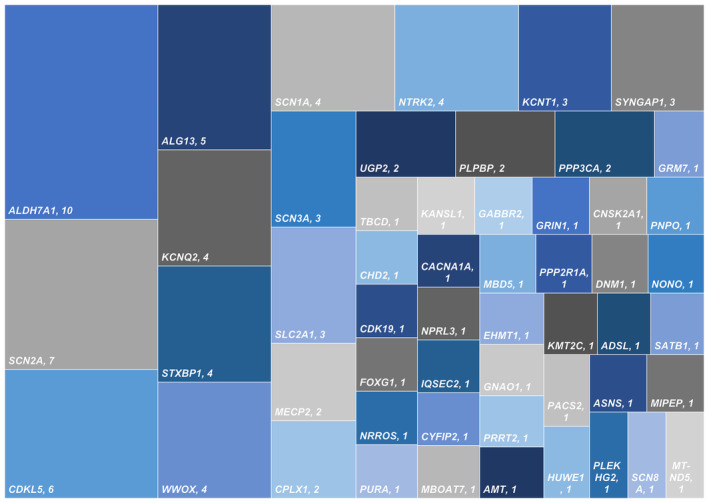

Of 124 included children, 19 had underlying chromosomal disorders (14/19 are Trisomy 21), 105 had single gene disorders (104 nuclear DNA, one mitochondrial DNA), and one had a triple repeat disorder (fragile X syndrome) along with a likely pathogenic nuclear gene (Figure 1). The commonest chromosomal disorder was trisomy 21 (Down syndrome; 14/19), followed by Xq28 duplication (2/19). Other chromosomal disorders were Cri‐du‐Chat syndrome, 15q duplication, and unbalanced translocation (1p36 deletion and 18q terminal duplication). Fifty‐one pathogenic/ likely pathogenic monogenic disorders with 92 variations (Table 1) were identified, with the most frequent ones being ALDH7A1 (10/104), SCN2A (7/104), CDKL5 (6/104), and ALG13 (5/104) (Figure 2). Other common genes with pathogenic variations included KCNQ2 n = 4, NTRK2 n = 4, STXBP1 n = 4, SCN1A n = 4, and WWOX n = 4. Twenty‐five of the 92 identified variants were novel (Table 1). Few of the included cases in the study were reported previously, either as case reports or part of the case series, and are indicated in Table 1. 11 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 Among the single gene disorders, 58 (55.2%) were autosomal dominant, 31 (29.5%) were autosomal recessive, 15 (14.2%) were X‐linked, and one had a mitochondrial inheritance.

FIGURE 1.

Genetic spectrum of children with genetic IESS.

TABLE 1.

Genotypic description of the children with genetic IESS due to monogenic causes.

| Serial no. | Gene | Exon/intron location | Chromosomal location | Type of variation | Specify gene variation | Variant amino acid change | Zygosity | Inheritance pattern | Variant classification as per ACMG | Novelty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ALDH7A1 | Exon 12 | Chromosome 5 | Nonsense | c.1048C>T | p.Arg350Ter | Homozygous | AR | Pathogenic | rs1015686016 |

| 2 | ALDH7A1 | Intron 12 and Exon 11 | Chromosome 5 | Splice site and nonsense | c.1093+1G>A and c.1003C>T | 5′ splice site and p.Arg335Ter | Compound heterozygous | AR | Pathogenic | rs794727058; rs1015686016 |

| 3 | ALDH7A1 (ENST00000636879.1) | Exon 16 and Exon 15 | Chromosome 5 | Insertion and nonsense | c.1456_1457insG and c.1269T>G | p.Leu486ArgfsTer4; p.Tyr423Ter | Compound heterozygous | AR | Pathogenic | rs772766995, rs121912710 |

| 4 | ALDH7A1 | Exon 14 | Chromosome 5 | Missense | c.1279G>C | p.Glu427Gln | Homozygous | AR | Pathogenic | rs121912707 |

| 5 | ALDH7A1 | Exon 1 | Chromosome 5 | Nonsense | c.187G>T | p.Gly63Ter | Homozygous | AR | Pathogenic | rs760636660 |

| 6 | ALDH7A1 | Exon 17 | Chromosome 5 | Missense | c.1556G>A | p.Arg519Lys | Homozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | rs561343926 |

| 7 | ALDH7A1 (ENST00000636879.1) | Exon 7 | Chromosome 5 | Missense | c.575C>A | p.Ala192Glu | Homozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | rs764417585 |

| 8 | ALDH7A1 | Exon 9 | Chromosome 5 | Nonsense | c.841C>T | p.Gln281Ter | Homozygous | AR | Pathogenic | rs1170817007 |

| 9 | ALDH7A1 | Exon 1 | Chromosome 5 | Nonsense | c.187G>T | p.Gly63Ter | Homozygous | AR | Pathogenic | rs760636660 |

| 10 | ALDH7A1 | Exon 1 | Chromosome 5 | Nonsense | c.187G>T | p.Gly63Ter | Homozygous | AR | Pathogenic | rs760636660 |

| 11 | SCN2A (NM_001040142.2) | Exon 23 | Chromosome 2 | Insertion | c.4004_4005insGGAAT | p.Ser1336GlufsTer5 | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 12 | SCN2A | Exon 7 | Chromosome 2 | Missense | c.788C>T | p.Ala263Val | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs387906686 |

| 13 | SCN2A | Exon 3 | Chromosome 2 | Nonsense | c.330C>A | p.Tyr110Ter | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | Reported without RS id |

| 14 | SCN2A | Exon 27 | Chromosome 2 | Missense | c.5645G>A | p.Arg1882Gln | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs794727444 |

| 15 | SCN2A | Exon 23 | Chromosome 2 | Nonsense | c.4303C>T | p.Arg1435Ter | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs796053138 |

| 16 | SCN2A | Exon 19 | Chromosome 2 | Missense | c.3631G>A | p.Glu1211Lys | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs387906684 |

| 17 | SCN2A | Exon 17 | Chromosome 2 | Missense | c.2995G>A | p.Glu999Lys | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs796053126 |

| 18 | CDKL5 | Exon 6 | Chromosome X | Missense | c.211A>G | p.Asn71Asp | Heterozygous | XL | Pathogenic | rs587783072 |

| 19 | CDKL5 | Exon 10 | Chromosome X | Missense | c.587C>T | p.Ser196Leu | Heterozygous | XL | Pathogenic | rs267608501 |

| 20 | CDKL5 | Exon 6 | Chromosome X | Missense | c.248G>T | p.Gly83Val | Heterozygous | XL | Pathogenic | rs587783402 |

| 21 | CDKL5 (NM_001323289.2) | Exon 18 | Chromosome X | Deletion | c.2486delT | p.Leu829Argfs*8 | Heterozygous | XL | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 22 | CDKL5 | Intron 9 | Chromosome X | Splice site | c.554+5G>A | 5′ Splice site | Heterozygous | XL | Pathogenic | rs1925577525 |

| 23 | CDKL5 (ENST000 00379989) | Exon 10 | Chromosome X | Deletion | c.633delT | p.Pro212LeufsTer16 | Heterozygous | XL | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 24 | ALG13 | Exon 3 | Chromosome X | Missense | c.320A>G | p.Asn107Ser | Hemizygous | XL | Pathogenic | rs398122394 |

| 25 | ALG13 | EXON ‐3 | Chromosome X | Missense | c.320A>G | p.Asn107Ser | Hemizygous | XL | Pathogenic | rs398122394 |

| 26 | ALG13 | Exon 17 | Chromosome X | Missense | c.2057G>A | p.Cys686Tyr | Hemizygous | XL | Likely pathogenic | rs767698446 |

| 27 | ALG13 | Exon 3 | Chromosome X | Missense | c.320A>G | P.Asn107Ser | Hemizygous | XL | Likely pathogenic | rs398122394 |

| 28 a | ALG13 | Exon 3 | Chromosome X | Missense | c.320A>G | p.Asn107Ser | Hemizygous | XL | Likely pathogenic | rs398122394 |

| 29 | KCNQ2 | Exon 5 | Chromosome 20 | Missense | c.793G>A | p.Ala265Thr | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs794727740 |

| 30 | KCNQ2 | Exon 6 | Chromosome 20 | Missense | c.917C>T | p.Ala306Val | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs864321707 |

| 31 | KCNQ2 (NM_172107.4) | Exon 6 | Chromosome 20 | Missense | c.850T>C | p.Tyr284His | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | Reported without RS id |

| 32 | KCNQ2 | Exon 5 | Chromosome 20 | Missense | c.794C>T | p.Ala265Val | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs587777219 |

| 33 | STXBP1 | Exon 18 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.1654T>C | p.Cys552Arg | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs1842046459 |

| 34 | STXBP1 | Exon 9 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.704G>A | p.Arg235Gln | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs794727970 |

| 35 | STXBP1 | Exon 14 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.1216C>T | p.Arg406Cys | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs796053367 |

| 36 | STXBP1 (ENST00000637953.1) | Exon 10 | Chromosome 9 | Nonsense | c.863G>A | p.Trp288Ter | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 37 | WWOX (ENST00000566780.6) | Exons 6 and 9 | Chromosome 16 | Deletion and missense | c.553_566del and c.1193G>A | p.Ala185ArgfsTer6 and p.Trp398Ter | Compound heterozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | rs759794876; Novel |

| 38 | WWOX (ENST00000566780.6) | Exons 2 and 7 | Chromosome 16 | Deletion and nonsense | c.155_156del and c.744C>A | p.Arg52Lyster16 and p.cys248Ter | Compound heterozygous | AR | Pathogenic | Novel; Novel |

| 39 | WWOX (ENST00000566780.6) | Exons 5 to 8; Intron 5 | Chromosome 16 | Deletion; splice site | (516+1_517–1)_(1056+1_1057‐1)del; c.517‐3c>A | Exonic deletion and 3′ splice site | Compound heterozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | Uncertain; Novel |

| 40 | WWOX | Exon 7 | Chromosome 16 | Nonsense | c.790C>T | p.Arg264Ter | Homozygous | AR | Pathogenic | rs756762196 |

| 41 | SCN1A | Exon 16 | Chromosome 2 | Missense | c.2311G>A | p.Asp771Asn | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | Reported without RS id |

| 42 | SCN1A | Intron 28 | Chromosome 2 | Splice site | c.4853‐1G>C | 3′ splice site | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs1553520530 |

| 43 a | SCN1A (ENST00000674923.1) | Exon 15 | Chromosome 2 | Duplication | c.2712dupT | p.Ala905CysfsTer10 | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | Novel |

| 44 | SCN1A | Exon 7 | Chromosome 2 | Missense | c.1007G>A | p.Cys336Tyr | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs794726798 |

| 45 | NTRK2 (NM_006180.6) hg19 | Exon 12 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.1301A>G | p.Tyr434Cys | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs886041091 |

| 46 a | NTRK2 (NM_006180.6) hg19 | Exon 12 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.1301A>G | p.TyrY434Cys | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs886041091 |

| 47 a | NTRK2 (NM_006180.6) hg19 | Exon 12 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.1301A>G | p.Tyr434Cys | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs886041091 |

| 48 a | NTRK2 (NM_006180.6) hg19 | Exon 12 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.1301A>G | p.Tyr434Cys | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs886041091 |

| 49 | KCNT1 (ENST00000371757.7) | Intron 2 | Chromosome 9 | 3′ splice site | c.255‐2A>G | 3′ splice site | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 50 | KCNT1 | Exon 12 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.1038C>G | p.Phe346Leu | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs767434859 |

| 51 | KCNT1 | Exon 11 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.862G>A | p.Gly288Ser | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs587777264 |

| 52 | SYNGAP1 | Exon 5 | Chromosome 6 | Nonsense | c.490C>T | p.Arg164Ter | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs1057518352 |

| 53 | SYNGAP1 | Exon 8 | Chromosome 6 | Non‐sense | c.1081C>T | p.Gln361Ter | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs1554121231 |

| 54 | SYNGAP1 | Exon 17 | Chromosome 6 | Non‐sense | c.3718C>T | p.Arg1240Ter | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs869312955 |

| 55 | SCN3A | Exon 28 | Chromosome 2 | Missense | c.5576G>A | p.Arg1859His | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs778995406 |

| 56 | SCN3A | Exon 28 | Chromosome 2 | Missense | c.5576G>A | p.Arg1859His | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs778995406 |

| 57 | SCN3A (NM_006922.4) | Exon 21 | Chromosome 2 | Missense | c.3734A>C | p.Lys1245Thr | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | Reported without RS id |

| 58 | SLC2A1 (NM_006516.4) | Exon 9 | Chromosome 1 | Duplication | c.1119dup | p.Gly374TrpfsTer7 | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 59 | SLC2A1 (NM_006516.4) | Exon 6 | Chromosome 1 | Missense | c.691C>G | p.Leu231Val | Homozygous | AR | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 60 | SLC2A1 (NM_006516.4) | Exon 6 | Chromosome 1 | Missense | c.691C>G | p.Leu231Val | Homozygous | AR | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 61 | MECP2 | Exon 2 | Chromosome X | Deletion | ChrX:g.(?_154019188_(154031459_?)del | Exonic deletion of 12.27 kb | Heterozygous | XL | Pathogenic | – |

| 62 | MECP2 | Exon 3 | Chromosome X | Nonsense | c.799C>T | p.Arg267Ter | Heterozygous | XL | Pathogenic | rs61749721 |

| 63 | CPLX1 (ENST00000304062.11) | Exon 3 | Chromosome 4 | Deletion | c.151_183del | p.Lys51_Ala61del | Homozygous | AR | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 64 | CPLX1 (ENST00000304062.11) | Exon 4 | Chromosome 4 | Nonsense | c.210C>G | p.Tyr70Ter | Homozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | Reported without RS id |

| 65 | UGP2 (ENST00000445915.6) | Exon 2 | Chromosome 2 | Missense | c.61A>G | p.Met21Val | Homozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | rs768305634 |

| 66 | UGP2 | Exon 2 | Chromosome 2 | Missense | c.34A>G | p.Met12Val | Heterozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | rs768305634 |

| 67 | PPP3CA (NM_000944.5) | Exon 12 | Chromosome 4 | Deletion | c.1255_1256del | p.Ser419CysfsTer31 | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs1553920383 |

| 68 | PPP3CA | Exon 12 | Chromosome 4 | Duplication | c.1283dup | p.Thr429AsnfsTer22 | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs1727004803 |

| 69 | GRM7 | Exons 3–4 | Chromosome 3 | Deletion | c.(736+1_737–1)_(1033+1_1034‐1)del | Exonic deletion of 7.99 kb | Homozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | – |

| 70 | TBCD | Exon 18 | Chromosome 17 | Missense | c.1661C>T | p.Ala554Val | Homozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | rs1555641324 |

| 71 | CHD2 | Exon 37 | Chromosome 15 | Missense | c.4763G>A | p.Arg1588Gln | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs1164926261 |

| 72 | CDK19 (NM_015076.5) | Exon 12 | Chromosome 6 | 18 base pair duplication | c.1113_1130dup | p.Gln373_Gln378dup | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | Novel |

| 73 | FOXG1 (NM_005249.5) | Exon 1 | Chromosome 14 | Single BP insertion | c.953_954insC | p.Arg320ProfsTer135 | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 74 a | NRROS | Exon 2 | Chromosome 3 | Deletion | c.1359del | p.Ser454Alafs*11 | Homozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | rs1346764478 |

| 75 a | PURA (NM_005859.5) | Exon 1 | Chromosome 5 | Duplication | c.479dup | p.Glu161GlyfsTer40 | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 76 | KANSL1 | Exon 6 | Chromosome 17 | Missense | c.1799A>G | p.Lys600Arg | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs770594188 |

| 77 | GABBR2 (NM_005458.8) | Exon 15 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.2084G>A | p.Ser695Asn | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | Reported without RS id |

| 78 | GRIN1 | Exon 18 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.2452A>C | p.Met818Leu | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs1554770628 |

| 79 | CSNK2A1 (NM_001895.4) | Exon 13 | Chromosome 20 | Missense | c.1012A>G | p.Ser338Gly | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | Novel |

| 80 | PNPO | EXON 4 | Chromosome 17 | Missense | c.413G>A | p.Arg138His | Homozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | rs764940495 |

| 81 | CACNA1A (NM_001127222.2) | Exon 20 | Chromosome 19 | Deletion | c.3550delC | p.His1180ThrfsTer6 | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | Novel |

| 82 | PLPBP (NM_007198.4) | Exon 8 | Chromosome 8 | Missense | c.727G>A | p.Gly243Arg | Homozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | Novel |

| 83 | NPRL3 | Exon 5 | Chromosome 16 | Deletion | c.423_426del | p.Leu142IlefsTer27 | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs1567139896 |

| 84 | PLPBP (NM_007198.4) | Exon 8 | Chromosome 8 | Missense | c.727G>A | p.Gly243Arg | Homozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | Novel |

| 85 | IQSEC2 (ENST000 00396435. 3) | Exon 7 | Chromosome X | Nonsense | chrX:g.53277315G>A | p.Arg855Ter | Homozygous | XL | Pathogenic | rs587777261 |

| 86 | CYFIP2 | Exon 4 | Chromosome 5 | Missense | c.259C>T | p.Arg87Cys | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs1131692231 |

| 87 | MBOAT7 (NM_024298.5) | Exon 8 | Chromosome 19 | Deletion | c.1059del | p.Tyr354ThrfsTer11 | Homozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | Novel |

| 88 | MBD5 | Exon 8 | Chromosome 2 | Insertion | c.539_540ins | p.Gln190TyrfsTer88 | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | – |

| 89 | PPP2R1A (NM_014225.6) | Intron 10 | Chromosome 19 | Splice site | c.1302+2T>G | 5′ splice site | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 90 | DNM1 | Exon 6 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.709C>T | p.Arg237Trp | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs760270633 |

| 91 | NONO | Intron 8 | Chromosome X | Splice site | c.1028+3A>G | 5′ splice site proximal | Hemizygous | XL | Likely pathogenic | rs1447518463 |

| 92 | EHMT1 | Exon 19 | Chromosome 9 | Missense | c.2842C>T | p.Arg948Trp | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs368702408 |

| 93 | GNAO1 | Exon 8 | Chromosome 16 | Missense | c.935A>G | p.Asn312Ser | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs758503575 |

| 94 | PRRT2 | Exon 2 | Chromosome 16 | Duplication | c.649dupC | p.Arg217Profs*8 | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | rs587778771 |

| 95 | AMT | Exon 7 and Exon 1 | Chromosome 3 | Missense and others | c.794G>A and c.2T>C | p.Arg265His and p.Met1Thr | Compound Heterozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | rs757918826; rs1266259634 |

| 96 | KMT2C | Intron 37 | Chromosome 7 | 4 (splice acceptor variant) | c.7443‐2delA | Splice acceptor variant | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs753425356 |

| 97 | ADSL (ENST00000216194) hg19 | Intron 6 and Exon 9 | Chromosome 22 | Missense | c.701+1G>A; and c.926G>A | 5′ splice site and p.Arg309His | Compound Heterozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | rs546878201; rs749817666 |

| 98 | SATB1 (NM_001131010.4) | Intron 10 | Chromosome 3 | Splice site | c.1780‐2A>G | 3′ splice site | Heterozygous | AD | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 99 | PACS2 (ENST00000447393.6) | Exon 6 | Chromosome 14 | Missense | c.625G>A | p.Glu209Lys | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | Novel |

| 100 | HUWE1 | Exon 64 | Chromosome X | Missense | c.9209G>A | p.Arg3070His | Hemizygous | XL | Pathogenic | rs2061745581 |

| 101 | ASNS | Exon 10 | Chromosome 7 | Missense | c.1138G>T | p.Ala380Ser | Homozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | rs758183057 |

| 102 | MIPEP (NM_005932.4) | Exon 13 | Chromosome 13 | Missense | c.1409T>C | p.Leu470Pro | Homozygous | Ar | Likely pathogenic | Novel |

| 103 | PLEKHG2 | Exons 18 and 19 | Chromosome 19 | Both missense | c.1855G>A and c.3953C>T | p.Glu619Lys and p.Ser1318Leu | Compound Heterozygous | AR | Likely pathogenic | rs750591987; rs755575206 |

| 104 | SCN8A | Exon 27 | Chromosome 12 | Missense | c.5614C>T | p.Arg1872Trp | Heterozygous | AD | Likely pathogenic | rs796053228 |

| 105 | MT‐ND5 | Mitochondrial DNA | Mitochondrial DNA | Missense | m.13513G>A | p.Asp393Asn | Heteroplasmic | Mito | Pathogenic | rs267606897 |

Previously published cases.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of single‐gene disorders causing genetic IESS.

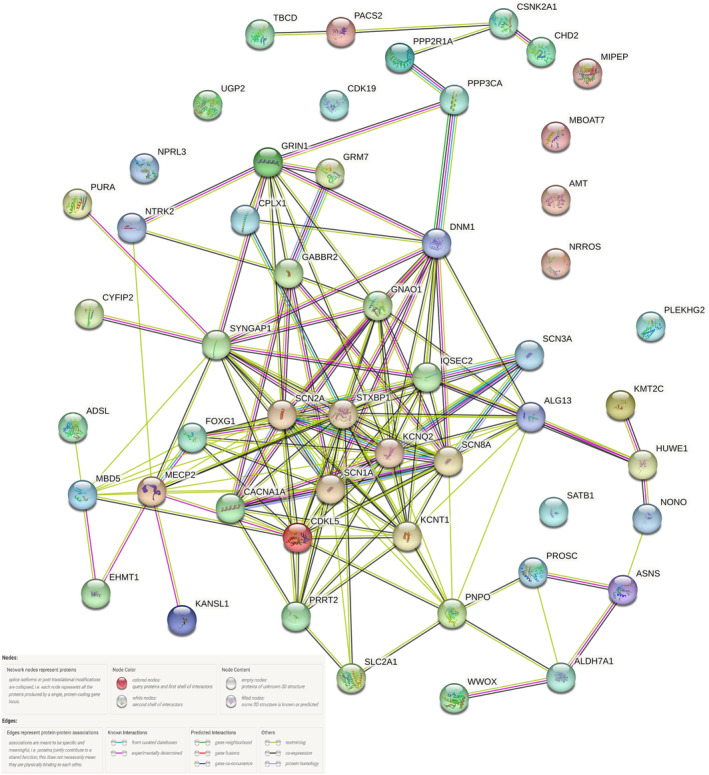

The functional significance and relationship of the various genes were explored using STRING bioinformatics database version 11.5 (Figure 3 and Figure S1). 25 Among the various functional categories, the majority of genes had a role in regulating cell communication, signaling, nervous system development, and cellular component organization.

FIGURE 3.

Gene network diagram and its interactions among the genes observed in the study.

3.3. Phenotypic characteristics

The median age at the onset of ES was 5 months (Q1‐Q3: 3 to 10) (Figure S2). Onset after the first year of life was seen in 22 children [Trisomy 21 (n = 3), Xq28 duplication syndrome (n = 2), ALG13 (n = 2), SYNGAP1 (n = 2), SLC2A1 (n = 2), 15q duplication syndrome (n = 1), SCN1A (n = 1), SCN2A (n = 1), ADSL (n = 1), SATB1 (n = 1), NRROS (n = 1), MECP2 (n = 1), SCN3A (n = 1), IQSEC2 (n = 1), FOXG1 (n = 1) and GABBR2 with Fragile X syndrome (n = 1)]. Developmental delay before the onset of ES was present in more than 90% of children, while seizures other than ES were observed in two‐thirds of patients (Tables 2 and 3). Developmental delay before the onset of ES was present in all except seven children (ALG13 n = 2, NTRK2 n = 1, KCNT1 n = 1, GRIN1 n = 1, SCN1A n = 1, and MECP2 n = 1) and they did not have any definite contrasting feature which delineated them from the rest of the cohort. Twenty‐one (16.9%) children evolved from another epilepsy syndrome [Early infantile developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (n = 20) and Epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal seizures (n = 1)] to IESS (Table 2). Common clinical findings include central hypotonia (81%), facial dysmorphism (70.1%), microcephaly (77.4%), movement disorders (45.9%), and autistic features (42.7%). Normal neuroimaging in Magnetic Resonance imaging was observed in 67.7% and the remaining had non‐specific neuroimaging findings without any neuroimaging clue (Table 2). Around 60% of children responded to initial hormonal therapy. Relapses after the initial therapeutic response were observed in one‐third of children.

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic characteristics of the entire cohort of children with genetic IESS.

| Phenotypic features (n = 124) | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age of onset of spasms in months with Q1, Q3 | 5 months (Q1, Q3: 3, 10) |

| Developmental delay before the onset of spasms |

117 (94.3%) Global developmental delay (109), Only Language and Social adaptive delay (8) |

| Seizures other than epileptic spasms (n with %) | 83 (66.9%) |

| Pre‐existing epilepsy syndrome |

21 (16.9%) Early infantile developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (20), Epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal seizures (1) |

| Other relevant history | |

| History of neonatal encephalopathy or seizures | 15 (12.09%) |

| Consanguinity | 19 (15.3%) |

| Family history of epileptic spasms/seizures/neurological illness | 9 (7.2%) |

| Examination findings | |

| Facial dysmorphism | 87 (70.1%) |

| Microcephaly | 96 (77.4%) |

| Central hypotonia | 101 (81.4%) |

| Autistic features | 53 (42.7%) |

| Movement disorder | 72 (58.0%) |

| With onset before the onset of epileptic spasms | 17 |

| Dystonia/choreoathetosis/both/stereotypies | 24/10/7/38 |

| Non‐specific neuroimaging abnormalities without definite etiological clue | 40 (32.3%) |

| Brain atrophy | 16 |

| Non‐specific changes in cerebral cortex | 2 |

| Non‐specific changes in white matter | 2 |

| Non‐specific changes (morphology or signal intensity) in corpus callosum | 15 |

| Non‐specific changes (morphology or signal intensity) in basal ganglia/ thalamus/brainstem/cerebellum | 2 |

| Ventriculomegaly | 3 |

| Therapeutic response | |

| Clinical response to epileptic spasms attained anytime | 97 (72.5%) |

| Response to initial hormonal therapy | 74 (59.6%) |

| Response to vigabatrin | 31 |

| Response to nitrazepam | 25 |

| Response to zonisamide | 4 |

| Response to topiramate | None |

| Response to KD | 5 |

| Relapse observed | 43 (34.6%) |

TABLE 3.

Clinical outcomes of the cohort as observed at the last follow‐up.

| Characteristic (n = 124) | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Mortality | 8 (6.4) |

| Median age at death with Q1, Q3 (n = 8) | 42 (13, 60) |

| Median age at assessment for those surviving with Q1, Q3 | 18 months (8, 39) |

| Epilepsy outcomes | N = 116 |

| Current spasms frequency per day | |

| Nil | 84 |

| 1–5 | 20 |

| 5–10 | 4 |

| More than 10 but <50 | 5 |

| More than 50 | 3 |

| Current seizure frequency per day (apart from spasms) | |

| Nil | 81 |

| 1–3 episodes per day | 27 |

| 3–5 episodes per day | 4 |

| More than 5 episodes per day | 4 |

| Admission for status epilepticus in last 2 y (n = 116) | 24 (19.3%) |

| Evolution to Lennox Gastaut syndrome | 31 (25%) |

| Developmental status at last visit (n = 124) | |

| Global developmental delay | 109 (88%) |

| Only language delay | 2 (1.6%) |

| Both language and socio‐adaptive delay | 12 (9.6%) |

| Normal development | 1 (0.8%) |

| Ambulation at last follow‐up (applicable for 101 children) | |

| Ambulatory | 42 (33.8%) |

| Non‐ambulatory | 59 (47.5%) |

| School‐going status at last follow‐up (applicable for 59 children) | |

| School going | 14 (11.2%) |

| Non‐school going | 45 (36.2%) |

| Behavioral issues at the last follow up | 83 (67%) |

| Hyperactivity | 11 (8.8%) |

| Autistic | 43 (34.6%) |

| Autistic and hyperactivity | 19 (15.3%) |

| Behavioral issues present but not fitting above | 10 (8%) |

| No behavioral issues at the last follow up | 41 (33%) |

| Sleep disturbances based on history at the last follow up | 30 (24.1%) |

Eight of the included children (6.4%) had succumbed, with the median age at death being 42 months (Q1, Q3: 13, 60). Nearly 70% of children were seizure or spasms‐free at the last follow‐up, while one‐fifth of included children required hospitalization for status epilepticus in the previous 2 years. Evolution to LGS was observed in 25% of the included children. All except one child had some developmental delay at the last follow‐up. Around 40% of children were ambulatory, while 23% went to school. Significant behavioral issues were observed in two‐thirds of surviving children (most common being autistic features), while sleep disturbances were observed in one‐fourth of surviving children.

3.4. Genotype–phenotype association

Phenotypic details of four common monogenic disorders seen in the cohort‐ ALDH7A1 n = 10, SCN2A n = 7, CDKL5 n = 6, and ALG13 n = 5 have been compared (Table 4). Early onset of ES (<6 months) was remarkable and universal with ALDH7A1 and CDKL5. Among these four disorders, all children except one child with ALG13‐related DEE had pre‐existing developmental delay; All these disorders except ALG13 among these four monogenic DEE had other seizure types before the onset of ES (including neonatal onset seizures), and many of these had evolved from early infantile developmental and epileptic encephalopathy to IESS (Table 4). Central hypotonia was frequently associated with all these disorders, while microcephaly, autistic features, and movement disorders were associated with SCN2A, CDKL5, and ALG13 (Table 4). The long‐term outcome was good in ALDH7A1, with the attainment of seizure freedom with pyridoxine in all children. However, the long‐term neurodevelopmental outcome was poor in most children with SCN2A (5/6 non‐ambulatory, 4/7 autistic, one progressed to LGS); CDKL5 (two succumbed, all had persistent daily seizures, three progressed to LGS), and ALG13 (all except one had autistic features with stereotypies and prominent sleep disturbances).

TABLE 4.

Master table of the phenotypic characteristics of the various genotypes among monogenic causes in descending order of frequency.

| Serial no gene | Sex | Seizures (age in months); prior epilepsy syndrome if any | Movement disorder (onset: age in months) | Phenotypic characteristics | Treatment response | Outcome until the last follow‐up (age in months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 ALDH7A1 |

M | FC (1), ES (3); prior EIDEE | Absent | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, responded with VGB & pyridoxine | ESC, SF, BC (8) |

|

2 ALDH7A1 |

M | FC (2), ES (5) | Absent | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, response with VGB & pyridoxine | ESC, SF, AMB, BC (12) |

|

3 ALDH7A1 |

M | MC (1), ES (5); prior EIDEE | Absent | NHC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with pyridoxine | ESC, SF, Normal DEV (6) |

|

4 ALDH7A1 |

F | GT (1), ES (4); prior EIDEE | Absent | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, response with pyridoxine | ESC, SF, AMB (22) |

|

5 ALDH7A1 |

M | GT (1), ES (6) | Absent | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, response with pyridoxine | ESC, SF, AMB (48) |

|

6 ALDH7A1 |

M | GT (1), ES (4); prior EIDEE | Absent | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, response with pyridoxine | ESC, SF, AMB (112) |

|

7 ALDH7A1 |

M | GT (1), ES (3); prior EIDEE | Stereotypies (12) | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, response with pyridoxine | ESC, SF, AMB (15) |

|

8 ALDH7A1 |

F | GT (1), ES (4); prior EIDEE | Absent | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, response with pyridoxine | ESC, SF, AMB (16) |

|

9 ALDH7A1 |

F | FUA (1), ES (3); prior EIDEE | Stereotypies (10) | NHC, C HYP, CVI | FIHT, response with pyridoxine | ESC, SF, AMB (12) |

|

10 ALDH7A1 |

M | GT (1), ES (5); prior EIDEE | Absent | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, response with pyridoxine | ESC, SF, AMB (15) |

|

11 SCN2A |

M | ES (18) | Absent | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, response with NZ, NRTP | ESC, SF, NAMB, AU (40) |

|

12 SCN2A |

F | FT, GT (1), ES (3); prior EIDEE | Absent | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, response with VGB, NRTP | ESC, SF, NAMB, BC (67) |

|

13 SCN2A |

F | ES (6) | Stereotypies (12) | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, relapse, response with VGB, NRTP | ESC, SF, NAMB, AU (60) |

|

14 SCN2A |

M | GT (1), ES (3); prior EIDEE | Absent | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, response with NZ | ESC, SF (8) |

|

15 SCN2A |

M | ES (10), GT (18) | Absent | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB | ESC, SF, AMB (36) |

|

16 SCN2A |

F | GT (6), ES (7) | Stereotypies (14) | NHC, C HYP, CLDY | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB | ESC, SF, NAMB, AU (81) |

|

17 SCN2A |

F | GT (2), ES (2); prior EIDEE | Absent | NHC, MS, HTL, HAP, spasticity, CVI, HI | RIHT, relapse, poor responder | PES, DRE, NAMB, LGS, AU (18) |

|

18 CDKL5 |

F | FC, MC (3), ES (5) | Stereotypies (12) | MIC, C HYP, CVI bruxism | FIHT, response with NZ | ESC, DRE, NAMB, AU (72) |

|

19 CDKL5 |

F | ES (4), GT (12) | Stereotypies (84) | MIC, C HYP prominent ears | FIHT, response with NZ | ESC, DRE, NAMB, AU (120) |

|

20 CDKL5 |

F | GT (1), ES (5); prior EIDEE | Absent | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, response with NZ | ESC, DRE, non‐ambulatory, AUHA (60) |

|

21 CDKL5 |

F | GT, MC (1), ES (4) | Stereotypies (24) | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, relapse, response with VGB | ESC, DRE, NAMB, AU (44) |

|

22 CDKL5 |

F | FC (2), ES (4) | Stereotypies (12) | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, response with ZON | ESC, DRE, NAMB, AU (36); EXP due to SUDEP |

|

23 CDKL5 |

M | ES (2) | Choreathetosis and Dystonia (2) | NHC, C HYP, CVI | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB | DRE, LGS, NAMB, AU (46); EXP at 48 m due to AP |

|

24 ALG13 |

F | ES (5) | Stereotypies (12) | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with NZ | ESC, SF, AMB, AU (50) |

|

25 ALG13 |

F | ES (6) | Dystonia (6) | MIC, C HYP, LSE, HTL | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB | ESC, SF, NAMB (12) |

|

26 ALG13 |

M | ES (14), FUBA (14) | Stereotypies (5) | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB | ESC, SF, AMB, AU (47) |

|

27 ALG13 |

F | ES (13) | Stereotypies (5) | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB | ESC, SF, AMB, AU (19) |

|

28 ALG13 |

F | ES (5) | Stereotypies (12) | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB | ESC, SF, NAMB, AU (27) |

|

29 KCNQ2 |

M | FC (2), ES (4) | Absent | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, response with NZ | ESC, SF, NAMB (22) |

|

30 KCNQ2 |

M | MC (1), ES (2) | Absent | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with NZ | ESC, SF, NAMB (26) |

|

31 KCNQ2 |

F | FT (1), GT (1), ES (6); prior EIDEE | Absent | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, response with NZ | PES, DRE, LGS, AUHA (47) |

|

32 KCNQ2 |

F | GT (1), ES (6); prior EIDEE | Dystonia and Choreoathetosis (24) | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with NZ | ESC, DRE, NAMB, AU (36) |

|

33 STXBP1 |

F | ES (2) | Absent | MIC | FIHT, poor responder | PES, SF, NAMB (50) |

|

34 STXBP1 |

M | ES (3) | Dystonia (5) | NHC, C HYP | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF, AMB, BC (24) |

|

35 STXBP1 |

F | FUA (2), ES (3) | Dystonia (5) | NHC | FIHT, response with VGB | PES, SF, NAMB (7) |

|

36 STXBP1 |

F | FUBA (1), ES (3) | Dystonia (6) | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, response with VGB | ESC, SF, AMB, (18) |

|

37 WWOX |

M | FUA (2), ES (4) | Absent | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, response with VGB | ESC, SF (12) |

|

38 WWOX |

F | ES (3) | Absent | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with NZ | ESC, SF, NAMB (12) |

|

39 WWOX |

F | GTC (2), ES (3) | Absent | MIC, C HYP, UTN, SP | FIHT, response with ZON | PES, SF (6) |

|

40 WWOX |

F | ES (2) | Dystonia (8) | MIC, C HYP, LSE UTN, SP, HYTR | FIHT, poor responder, Failed KD | PES, DRE, NAMB (30) |

|

41 SCN1A |

F | ES (10) | Stereotypies (9) | MIC | FIHT, response with VGB | ESC, SF, NAMB, LGS, AUHA (25) |

|

42 SCN1A |

M | ES (5) | Absent | NHC | RIHT, relapse, response with NZ | ESC, DRE, ASE, NAMB, AUHA (40) |

|

43 SCN1A |

F | ES (2), GTC (3) | Absent | MIC | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB | PES, DRE, ASE, AMB, BC (48) |

|

44 SCN1A |

M | ES (24), GTC (6) | Absent | NHC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with NZ | ESC, SF, AMB, HA (92) |

|

45 NTRK2 |

M | ES (6) | Stereotypies and choreoathetosis (6) | NHC, C HYP | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF, NAMB (24) |

|

46 NTRK2 |

M | ES (3), FC (11), GT (11) | Stereotypies and choreoathetosis (9) | NHC, C HYP, CVI | FIHT, response with KD, relapse | PES, DRE, ASE, NAMB, HA (74) |

|

47 NTRK2 |

F | ES (6) | Dystonia and choreoathetosis | NHC | FIHT, response to valproate and clobazam, relapse | PES, SF, NAMB (55) |

|

48 NTRK2 |

M | ES (6), FT (6) | Absent | MC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, poor responder | ESC, DRE, LGS, NAMB (58) |

|

49 KCNT1 |

M | ES (7) | Absent | NHC, C HYP | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF, AMB (23) |

|

50 KCNT1 |

F | GT (2), FT (2), ES (4) | Absent | MIC, C HYP, CVI | FIHT, relapse, response with VGB | ESC, SF, AMB (24) |

|

51 KCNT1 |

M | FT (2), FTBTC (3),ES (3); Prior EIMFS | Stereotypies (8) | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, poor responder | ESC, DRE, LGS, NAMB, AU (43) |

|

52 SYNGAP1 |

M | ES (11), MA with EM (13) | Stereotypies (18) | NHC, C HYP long face, large ears | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF, AMB, AU (48) |

|

53 SYNGAP1 |

F | ES (24) | Stereotypies (12) | NHC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with clobazam | ESC, SF, AMB, AU (123) |

|

54 SYNGAP1 |

M | ES (15), MA with EM (18) | Stereotypies (18) | NHC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, poor responder | ESC, SF, AMB, AUHA (92) |

|

55 SCN3A |

M | ES (18), GTC (20) | Dystonia (6) | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, Responded with VGB | ESC, DRE, LGS, NAMB, AU (32) |

|

56 SCN3A |

M | ES (12), GTC (18) | Dystonia (9) | MIC | RIHT, No requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, DRE, AMB, HA (44) |

|

57 SCN3A |

M | ES (2) | Absent | NHC | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB | ESC, SF, AMB (31) |

|

58 SLC2A1 |

M | GTC (2), ES (5) | Absent | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, response with KD | ESC, SF, AMB, AUHA (40) |

|

59 SLC2A1 |

M | ES (14), GTC (10) | Dystonia and choreoathetosis (24) | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, response with KD | ESC, SF, AMB, AU (38) |

|

60 SLC2A1 |

M | ES (13), GTC (11) | Dystonia and choreoathetosis (20) | MIC | FIHT, response with KD | ESC, SF, AMB, AU (24) |

|

61 MECP2 |

F | GT (5), MC (5), ES (10) | Stereotypies (8) and choreoathetosis (12) | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF, AMB, AU, prominent sleep disturbance (39) |

|

62 MECP2 |

F | ES (18) | Stereotypies (8) and ataxia (12) | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF, AMB, AU (27) |

|

63 CPLX1 |

F | ES (3), MC (3) | Absent | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, poor responder | PES, DRE, ASE, NAMB (48) |

|

64 CPLX1 |

M | ES (3) | Absent | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, poor responder | PES, DRE (6) |

|

65 UGP2 |

M | ES (3) | Absent | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB | EXP at 13 months |

|

66 UGP2 |

F | GT (3), ES (4) | Dystonia (4) | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, relapse, response with VGB and ZON | PES, SF, prominently delayed onset and fragmented sleep (8) |

|

67 PPP3CA |

F | ES (3) | Absent | MIC, C HYP, CVI | FIHT, response with ZON | PES, CVI (9) |

|

68 PPP3CA |

F | ES (4), FC (15) | Stereotypies (10) | MIC, C HYP, CVI, HI | FIHT, poor responder | DRE, NAMB, LGS, AU (26) |

|

69 GRM7 |

F | GT (1), ES (11) | Absent | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, poor responder, sedation with ZON | PES, NAMB, AU (17) |

|

70 TBCD |

M | ES (12), FUBA (20), FTBTC (22), GT (24) | Stereotypies (18), dystonia (30) | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, transaminitis with valproate | ESC, DRE, ASE, LGS, AU (52) |

|

71 CHD2 |

M | ES (7) | Absent | NHC, C HYP | RIHT | ESC, SF (12) |

|

72 CDK19 |

M | ES (8) | Absent | MIC, C HYP, CVI, HI, hypotelorism, bulbous nose | FIHT, response with VGB | PES, BC (13) |

|

73 FOXG1 |

F | GT (8), GTC (8), ES (14) | Stereotypies (6), dystonia, and choreo‐athetosis (6) | MIC, C HYP, AUHA | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB | ESC, DRE, ASE, AUHA, prominently decreased sleep (42) |

|

74 NRROS |

M | FUBA (9), ES (18) | Dystonia (30) | MIC, HI | FIHT, poor responder, neuroregression | PES, DRE, NAMB; EXP at 36 months |

|

75 PURA |

F | ES (5) | Stereotypies, dystonia | NHC, HTL, CVI, AU, plagiocephaly | FIHT, response with VGB | ESC, SF, NAMB, AU (51) |

|

76 KANSL1 |

M | ES (12) | Absent | NHC, C HYP, Obesity | Initially started on VGB, response with VGB, relapse, response with NZ | PES, DRE, LGS, NAMB, BC (27) |

|

77 GABBR2 |

M | ES (18) | Stereotypies (12) | NHC, C HYP, AU, BF | FIHT, response with VGB, relapse, response with NZ | ESC, SF, NAMB, AU (36) |

|

78 GRIN1 |

F | GT (2), ES (2); prior EIDEE | Stereotypies (8) | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, poor responder | PES, AMB, LGS, delayed onset sleep prominently (13) |

|

79 CSNK2A1 |

F | ES (3) | Absent | MIC, C HYP, LSE, MS, MG | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF (9) |

|

80 PNPO |

F | GT (1), ES (2) | Dystonia (3) | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB, good response to pyridoxine and P‐5P | ESC, SF, AMB (26) |

|

81 CACNA1A |

F | ES (2), GTC (3) | Absent | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF (30) |

|

82 PLPBP |

M | FUBA (2), ES (5) | Absent | NHC | RIHT, relapse, response with NZ | ESC, SF, AMB, AUHA (120) |

|

83 NPRL3 |

F | FT (1), GT (1), ES (3); prior EIDEE | Absent | NHC | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF (6) |

|

84 PROSC |

M | GT (1), ES (6); Prior EIDEE | Stereotypies (6) | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, response with NZ | ESC, DRE, ASE, LGS, AMB, HA (120) |

|

85 IQSEC2 |

M | FT (6), ES (19), GT (50) | Stereotypies (24) | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, poor responder | ESC, DRE, LGS, AMB, HA (90) |

|

86 CYFIP2 |

M | FC (2), ES (11) | Absent | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with KD | NAMB before death; EXP at 2 y 7 mo of age |

|

87 MBOAT7 |

M | ES (6) | Absent | NHC, C HYP | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF, NAMB (22) |

|

88 MBD5 |

M | GTC (6), ES (6) | Absent | NHC, C HYP | RIHT, poor responder | ESC, DRE, AMB (30) |

|

89 PPP2R1A |

F | E (4), MC (11) | Stereotypies (9) | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, poor responder | DRE, LGS, AMB, AUHA (132) |

|

90 DNM1 |

M | ES (3) | Absent | MIC, C HYP, CVI, HI | FIHT, poor responder | PES, NAMB (40) |

|

91 NONO |

M | ES (6), GTC (84) | Stereotypies (12) | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, poor responder | PES, AMB, AU (199) |

|

92 EHMT1 |

F | ES (5) | Stereotypies (12) | MIC, C HYP, synophrys, LSE, brachycephaly | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF, NAMB, AU (20) |

|

93 GNAO1 |

F | GT (2), ES (3) | Dystonia (3) | NHC, C HYP | FIHT, response with NZ | ESC, SF, NAMB (48) |

|

94 PRRT2 |

F | GT (4), ES (7) | Dystonia (5) | NHC | FIHT, response with VGB | ESC, SF (9) |

|

95 AMT |

M | FC (2), ES (3) | Absent | MIC | FIHT, response with NZ | ESC, DRE (10) |

|

96 KMT2C |

M | FC (3), ES (5) | Stereotypies (18) | MIC, C HYP, AU | FIHT, response with NZ | PES, DRE, AMB, AU (108) |

|

97 ADSL |

F | FC (2), ES (15) | Stereotypies | MIC, Long eyebrows | FIHT, response with NZ | ESC, DRE, LGS, NAMB, AU (84) |

|

98 SATB1 |

M | ES (18), FUBA (130), GT (132) | Stereotypies | MIC, LSE | FIHT, response with VGB | ESC, AMB, AUHA (144) |

|

99 PACS2 |

M | ES (5) | MIC, C HYP | FIHT, response with NZ | ESC, NAMB, AUHA (44) | |

|

100 HUWE1 |

M | ES (10), GT (13) | Dystonia and choreoathetosis (12) | MIC, C HYP, BF, flat occiput, LSE, brachydactyly, NPF, deep eyes | RIHT, relapse, response with NZ | ESC, NAMB (20) |

|

101 ASNS |

M | FC (2), MC (2), ES (6) | Stereotypies | MIC | RIHT, relapse, response with ZON | ESC, DRE, AU, EXP at 8 months |

|

102 MIPEP |

M | ES (6), GTC (6) | Severe dystonia (8) | MIC, C HYP | RIHT, relapse, response with VGB | ESC, SF, NAMB (22) |

|

103 PLEKHG2 |

F | GTC (4), MC (4), ES (9) |

Stereotypies Dystonia (6) |

MIC, C HYP, AU | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF, AMB, AU (132) |

|

104 SCN8A |

M | GT (5), FUBA (6), ES (8) | Stereotypies | NHC, C HYP, HTL, LSE, deep eyes | FIHT, responded with NZ, No response to phenytoin | ESC, SF, AU (10) |

|

105 MT‐ND5 |

F | ES (6) | Dystonia (10) | NHC, C HYP, BF, large ears | RIHT, no requirement of second‐line therapy | ESC, SF, NAMB, neuroregression following varicella around 2 y of age (30) |

Abbreviations: AMB, ambulatory; AP, aspiration pneumonia; ASE, admission for status epilepticus in the preceding 2 y at last visit; AU, autistic; AUHA, autistic and hyperactive; BC, behavioral concerns like excessive anger, disobedient, self‐injurious behavior, etc.; BF, broad forehead; C HYP, central hypotonia; CLDY, clinodactyly; CVI, cortico visual impairment; DEV, development; DRE, drug refractory epilepsy; EIDEE, early infantile developmental and epileptic encephalopathy; EIMFS, epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal seizures; ESC, epileptic spasms under control; ES, epileptic spasms; EXP, expired; FC, focal clonic; F, female; FIHT, failed initial hormonal therapy; FTBTC, focal tonic to bilateral tonic clonic; FT, focal tonic; FUA, focal unaware seizure with automatisms; FUBA, focal unaware seizure with behavioral arrest; GT, generalized tonic; HA, hyperactive; HAP, high arched palate; H, hormonal therapy; HI, hearing impairment; HTL, hypertelorism; IESS, infantile epileptic spasms syndrome; LSE, low set ears; MC, myoclonic; MIC, microcephaly; M, male; MS, mongoloid slant; NAMB, non‐ambulatory; NHC, normal head circumference; NPF, narrow palpebral fissure; NRTP, no response to phenytoin; PES, persistent epileptic spasms; RIHT, responded to initial hormonal therapy; SF, seizure free.

4. DISCUSSION

The current study provides a glance at the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of genetic IESS in a multicentric Indian cohort of 124 children, diagnosed since January 2018 (over the last 4.5 years). The median diagnostic lag in genetic diagnosis was 7 months after the onset of ES, which might be multifactorial and contributed by due to the delay in the recognition of ES by parents and clinicians, the delay in other initial investigations, and the relatively huge cost of genetic investigations, which is usually out‐of‐pocket expenditure for Indian families and not covered by health insurance. 26 The structural genetic etiologies like tuberous sclerosis complex and malformations were excluded from the study as the point of interest in this study was exclusively unexplained and unknown etiology IESS. Hence, we did not include well‐established structural genetic causes of IESS like tuberous sclerosis complex, lissencephaly, focal cortical dysplasia, and various structural malformations.

Nearly 90% and 67% of children had pre‐existing developmental delay and epilepsy, which suggests the ongoing developmental epileptic encephalopathy associated with these genetic abnormalities since early infancy. Hence, most of the included children did not fit into the definition of “idiopathic IESS,” which has normal prior development and a poor yield of genetic investigations. Many genetic abnormalities were associated with the late onset of ES (beyond 1 year of age). Some genes like ALDH7A1, CDKL5, KCNQ2, KCNT1, NTRK2, STXBP1, UGP2, and WWOX characteristically had an early infantile‐onset in the current cohort similar to that described previously, while genetic variations in NRROS and SYNGAP1 (2/3) had onset of ES beyond 1 year of life like that reported in most patients with these disorders. 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 21 , 27

Microcephaly, facial dysmorphism, movement disorders, behavioral abnormalities, and non‐specific neuroimaging findings were not uncommon in the current cohort, as reported previously with other developmental epileptic encephalopathies. 13 , 14 , 15 Therapeutic response to initial hormonal therapy was much higher than that reported in IESS from South Asia, suggesting a relatively better epilepsy outcome in genetic IESS. 28 However, the treatment response in this study was defined only clinically and it did not include electrographic resolution in the definition. Commenting on electrographic resolution was not possible as this was a multicentric study with slight variation in management practices and it included retrospectively enrolled cases as well. This was one of the challenges which we faced and this is one of the limitations of the study. Precision‐based therapy was possible among identified genetic variants in ALDH7A1, PLPBP, PNPO, SLC2A1, KCNQ2, KCNT1, SCN2A, and SCN8A genes. However, response to precision‐based therapy was documented only in children with identified genetic variants in ALDH7A1, PLPBP, PNPO, and SLC2A1 genes. Ketogenic diet, a standard‐of‐care treatment modality for children with drug‐resistant epilepsy was effective in five children and it highlights the need of its trial in resistant cases. 29 The mortality was much less than that reported in IESS, probably due to the lower median age at assessment (18 months). 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 Long‐term epilepsy outcomes were much better than those reported in previous studies on IESS from India. 28 , 35 However, the long‐term neurodevelopmental outcomes were broadly comparable. Trisomy 21 was the study's most typical cause of genetic IESS, followed by ALDH7A1 (pyridoxine‐dependent epilepsy), SCN2A, and CDKL5‐related DEE. Overall, single‐gene disorders were the most common genetic category, complementing the idea behind whole exome sequencing as the first‐line genetic investigation for these children. 5 , 9 , 36 The commonest monogenic disorder observed was PDE, contrasting the findings of large genetic IESS cohorts. 8 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 This might be because seven children with PDE (three unrelated cases had the same variant; possible founder variation) were contributed by a single center catering to a population with a high prevalence of consanguinity. The frequencies of the other monogenic disorders, such as SCN2A, CDKL5, STXBP1, WWOX, etc., were comparable to that reported in previous cohorts. 8 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 The other common genes reported in previous cohorts, such as ARX, TSC, TUBA1A, Miller Dieker syndrome, and other structural neurometabolic disorders at initial presentation, were not observed in the current study since these were systematically excluded at the outset due to the associated characteristic neuroimaging abnormalities. 8 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 Furthermore, one child had a mitochondrially inherited disorder. Hence, the mitochondrial genome needs to be considered during evaluation once other genetic investigations are unyielding. The metabolic causes of genetic IESS in the current cohort with no definite neuroimaging clues include pyridoxine‐dependent epilepsy, adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency, arginosuccinate synthetase deficiency, mitochondrial disease, and glycine encephalopathy/non‐ketotic hyperglycinemia. This highlights the importance of genetic testing in unknown etiology IESS to identify potentially treatable metabolic conditions like pyridoxine‐dependent epilepsy.

The current study represents the largest cohort of genetic IESS from South Asia and provides the spectrum and the distribution of the various genetic causes and their phenotypic characteristics which exist in a resource‐limited setting. Unlike the large funded multinational consortia on epilepsy genetics, such as the Epi4K consortium, this study gives an insight into the impediments faced by epilepsy researchers working in low‐middle income settings. The genetic testing in resource‐limited settings is primarily done through out‐of‐pocket expenditure, and many families might not be affording. Hence, the yield and the landscape represented in the current cohort may not represent the actual figures. Unless robust funding mechanisms are available to pursue epilepsy genetic research in these countries with a huge burden, this seems the most feasible way to study the genotypic landscape (although with its shortcomings). Efforts were made to overcome these concerns associated with the retrospective study design, such as recall and case ascertainment biases in old cases, etc., through prospective assessment and case record review of all patients by a pediatric neurologist. Besides, it would have been useful and interesting to know the genetic yield of each diagnostic test and the distribution of the various etiologies of IESS including non‐genetic ones identified from all the centres in the study period. However, these details were not available as this was a non‐funded multicentre study and the objective of the study was focussed on understanding the genetic landscape of unexplained cases of IESS. Hence, the denominator of total number of IESS cases managed at all centers was not particularly looked at.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The spectrum of genetic IESS is heterogenous. Collectively, monogenic disorders are the most common cause of genetic IESS. Trisomy 21, ALDH7A1, SCN2A, CDKL5, and ALG13 are the common causes of genetic IESS. Strikingly, the cohort shows clinicians' efforts in identifying the treatable causes, such as pyridoxine‐dependent epilepsy in resource‐limited settings (ALDH7A1 was the commonest monogenic disorder). The mitochondrial inherited disorder can cause IESS. Central hypotonia, developmental delay before the onset of spasms, early onset of spasms (<6 months of age), autistic features, and facial dysmorphism were notable findings observed in children with genetic IESS.

6. FUTURE PERSPECTIVE

In the future, more genotypic‐specific multicentric studies exploring phenotypes and phenotype–genotype association are needed to broaden our understanding and knowledge in this area. This vital information on the neurobiology of these genes and genetic causes could have future prognostic and therapeutic implications. This is only the initial step in the right direction in the field of epilepsy genetics, with an ongoing quest for precision medicine in IESS.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

BN: study design, drafting the work, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing and approval of the manuscript; AK, AGS, LS, RS, and NS: study design, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting the work, and approval of the manuscript; PM: data collection, data interpretation, revising work critically, and approval of the manuscript; VKG, SY, IS, KS, NV, and others: study design, data interpretation, revising work critically and approval of manuscript JKS: conceptualization of study and design, drafting the work, data collection, data interpretation, manuscript writing, and approval of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee and Institute Collaborative Research Committee.

ADDITIONAL FINANCIAL INFORMATION UNRELATED TO THE CURRENT RESEARCH COVERING THE PAST YEAR

Jitendra Sahu has received an honorarium from the Indian Journal of Pediatrics for working as a Section Editor. He also received research grant support paid to his institution from the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi. Sandeep Negi received support from the Indian Council of Medical Research (Grant reference No. 3/1/3/147/Neuro/2021‐NCD‐1).

POLICY ON ETHICAL PUBLICATION

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Informed consent was obtained from the parents.

Supporting information

Figure S1–S2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Priyanka Madaan was supported by the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) Grant Reference No. Pool‐9000‐A. Sandeep Negi was supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research (Grant reference No. 3/1/3/147/Neuro/2021‐NCD‐1). We also acknowledge the families and children who participated in the study.

Nagarajan B, Gowda VK, Yoganathan S, Sharawat IK, Srivastava K, Vora N, et al. Landscape of genetic infantile epileptic spasms syndrome—A multicenter cohort of 124 children from India. Epilepsia Open. 2023;8:1383–1404. 10.1002/epi4.12811

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All‐important data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and uploaded as supplementary information.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zuberi SM, Wirrell E, Yozawitz E, Wilmshurst JM, Specchio N, Riney K, et al. ILAE classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset in neonates and infants: position statement by the ILAE task force on nosology and definitions. Epilepsia. 2022;63(6):1349–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lux AL, Osborne JP. A proposal for case definitions and outcome measures in studies of infantile spasms and West syndrome: consensus statement of the West Delphi group. Epilepsia. 2004;45(11):1416–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, Higurashi N, Hirsch E, Jansen FE, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the international league against epilepsy: position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):522–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hunter MB, Yoong M, Sumpter RE, Verity K, Shetty J, McLellan A, et al. Incidence of early‐onset epilepsy: a prospective population‐based study. Seizure. 2020;75:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wirrell EC, Shellhaas RA, Joshi C, Keator C, Kumar S, Mitchell WG. How should children with West syndrome be efficiently and accurately investigated? Results from the National Infantile Spasms Consortium. Epilepsia. 2015;56:617–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, Connolly MB, French J, Guilhoto L, et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):512–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Osborne JP, Lux AL, Edwards SW, Hancock E, Johnson AL, Kennedy CR, et al. The underlying etiology of infantile spasms (West syndrome): information from the United Kingdom infantile spasms study (UKISS) on contemporary causes and their classification. Epilepsia. 2010;51:2168–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Epi4K Consortium, Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project , Allen AS, Berkovic SF, Cossette P, Delanty N, Dlugos D, et al. De novo mutations in epileptic encephalopathies. Nature. 2013;501(7466):217–221. 10.1038/nature12439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lemke JR, Riesch E, Scheurenbrand T, Schubach M, Wilhelm C, Steiner I, et al. Targeted next generation sequencing as a diagnostic tool in epileptic disorders. Epilepsia. 2012;53:1387–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McTague A, Howell KB, Cross JH, Kurian M, Scheffer I. The genetic landscape of the epileptic encephalopathies of infancy and childhood. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:304–316. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00250-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Madaan P, Negi S, Sharma R, Kaur A, Sahu JK. X‐linked ALG13 gene variant as a cause of epileptic encephalopathy in girls. Indian J Pediatr. 2019;86(11):1072–1073. 10.1007/s12098-019-03059-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Michaud JL, Lachance M, Hamdan FF, Carmant L, Lortie A, Diadori P, et al. The genetic landscape of infantile spasms. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(18):4846–4858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krey I, Krois‐Neudenberger J, Hentschel J, Syrbe S, Polster T, Hanker B, et al. Genotype‐phenotype correlation on 45 individuals with West syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2020;25:134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yuskaitis CJ, Ruzhnikov MRZ, Howell KB, Allen IE, Kapur K, Dlugos DJ, et al. Infantile spasms of unknown cause: predictors of outcome and genotype‐phenotype correlation. Pediatr Neurol. 2018;87:48–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mitta N, Menon RN, McTague A, Radhakrishnan A, Sundaram S, Cherian A, et al. Genotype‐phenotype correlates of infantile‐onset developmental & epileptic encephalopathy syndromes in South India: a single Centre experience. Epilepsy Res. 2020;166:106398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Surana P, Symonds JD, Srivastava P, Geetha TS, Jain R, Vedant R, et al. Infantile spasms: etiology, lead time and treatment response in a resource limited setting. Epilepsy Behav Rep. 2020;14:100397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heyne HO, Singh T, Stamberger H, Abou Jamra R, Caglayan H, Craiu D, et al. De novo variants in neurodevelopmental disorders with epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2018;50(7):1048–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wanigasinghe J, Sahu JK, Madaan P, Fatema K, Linn K, Chand P, et al. Classifying etiology of infantile spasms syndrome in resource‐limited settings: a study from the south Asian region. Epilepsia Open. 2021;6(4):736–747. 10.1002/epi4.12548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Madaan P, Chand P, Linn K, Wanigasinghe J, Lhamu Mynak M, Poudel P, et al. Management practices for West syndrome in South Asia: a survey study and meta‐analysis. Epilepsia Open. 2020;5(3):461–474. 10.1002/epi4.12419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier‐Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yoganathan S, Arunachal G, Gowda VK, Vinayan KP, Thomas M, Whitney R, et al. NTRK2‐related developmental and epileptic encephalopathy: report of 5 new cases. Seizure. 2021;92:52–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gowda VK, Amoghimath R, Battina M, Shivappa SK, Benakappa N. Case series of early SCN1A‐related developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2021;16:212–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Madaan P, Kaushal Y, Srivastava P, Crow YJ, Livingston JH, Ahuja C, et al. Delineating the epilepsy phenotype of NRROS‐related microgliopathy: a case report and literature review. Seizure. 2022;100:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johannesen KM, Gardella E, Gjerulfsen CE, Bayat A, Rouhl RPW, Reijnders M, et al. PURA‐related developmental and epileptic encephalopathy: phenotypic and genotypic spectrum. Neurol Genet. 2021;7(6):e613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Nastou KC, Lyon D, Kirsch R, Pyysalo S, et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user‐uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D605–D612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anbarasu A, Sahu JK, Sankhyan N, Singhi P. Magnitude, determinants and impact of treatment lag in West syndrome: a prospective observational study. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2023. 10.4103/jpn.JPN_101_21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bartolini E. Inherited developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. Neurol Int. 2021;13(4):555–568. 10.3390/neurolint13040055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aramanadka R, Sahu JK, Madaan P, Sankhyan N, Malhi P, Singhi P. Epilepsy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in a cohort of West syndrome beyond two years of age. Indian J Pediatr. 2022;89(8):765–770. 10.1007/s12098-021-03918-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Devi N, Madaan P, Kandoth N, Bansal D, Sahu JK. Efficacy and safety of dietary therapies for childhood drug‐resistant epilepsy: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177(3):258–266. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.5648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vendrame M, Guilhoto LMFF, Loddenkemper T, Gregas M, Bourgeois BF, Kothare SV. Outcomes of epileptic spasms in patients aged less than 3 years: single‐center United States experience. Pediatr Neurol. 2012;46:276–280. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Widjaja E, Go C, McCoy B, Snead OC. Neurodevelopmental outcome of infantile spasms: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Epilepsy Res. 2015;109:155–162. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2014.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Riikonen R. Infantile Spasms: Outcome in clinical studies. Pediatr Neurol. 2020;108:54–64. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2020.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Harini C, Nagarajan E, Bergin AM, Pearl P, Loddenkemper T, Takeoka M, et al. Mortality in infantile spasms: a hospital‐based study. Epilepsia. 2020;61:702–713. 10.1111/epi.16468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sillanpää M, Riikonen R, Saarinen MM, Schmidt D. Long‐term mortality of patients with West syndrome. Epilepsia Open. 2016;1:61–66. 10.1002/epi4.12008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bhanudeep S, Madaan P, Sankhyan N, Saini L, Malhi P, Suthar R, et al. Long‐term epilepsy control, motor function, cognition, sleep and quality of life in children with West syndrome. Epilepsy Res. 2021;173:106629. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2021.106629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Symonds J, McTague A. Epilepsy and developmental disorders: next generation sequencing in the clinic. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2020;24:15–23. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2019.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1–S2

Data Availability Statement

All‐important data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and uploaded as supplementary information.