Abstract

Objective

In Morocco, there was a lack of data related to the epidemiology of epilepsy. This data serves as a useful basis for the development of any national intervention or action program against epilepsy in Morocco. Through this study, we aimed to estimate the active and lifetime prevalence of epilepsy in Morocco.

Methods

We collected data from eight out of 12 Moroccan regions in two steps: In the screening step, we first used a nationwide telephone diagnosis questionnaire and in the second stage, a team of physicians under the direction of an epileptologist conducted a confirmative survey for suspected cases. We fixed the confidence interval at α = 5% and the precision at 0.02.

Results

Up to 3184 responded positively to our invitation to participate in this study and were able to answer the questions of the first diagnostic questionnaire. In the diagnostic phase, physicians in neurology reinterviewed all 86 suspected cases using a confirmative diagnosis questionnaire, and 63 persons were confirmed as having lifetime epilepsy and 56 with active epilepsy. The mean age (Mean ± SD) of persons with epilepsy was 35.53 years (±21.36). The prevalence of lifetime and active epilepsy were 19.8 (19.6–20.0) and 17.6 (17.5–17.8) per 1000 (95% confidence interval), respectively.

Significance

This is the first study to estimate the active and lifetime prevalence of epilepsy in Morocco according to the international recommendations of the ILAE. The prevalence of lifetime and active epilepsy were 19.8 (15–24.6) and 17.6 (13.3–22.8) per 1000, respectively. We included both children and elderly subjects. The rates of active and lifetime population epilepsy prevalence in Morocco ranged between Asian and sub‐Saharan Africa low‐ and middle‐income countries.

1. INTRODUCTION

Key points.

We performed a telephonic national survey of the prevalence of lifetime and active epilepsy in Morocco according to the ILAE recommendations.

The prevalence of lifetime and active epilepsy in Morocco were respectively 19.8 (19.6 – 20.0) and 17.6 (17.5‐17.8) per 1000 (95 % CI).

The rates of active and lifetime Epilepsy prevalence in Morocco ranged between Asian and sub‐Saharan Africa low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Epilepsy is one of the most common brain diseases responsible for a significant burden worldwide. 1 It affects approximately 70 million people of all ages, 80% of whom are from low–middle‐income countries. 2 It is an important cause of disability and mortality 3 ; for 328 causes worldwide, between 1990 and 2016 in 195 countries, epilepsy was placed among the top 30 causes of years lived with disability. 4

Low–middle‐income countries reported an active prevalence of over 10 per 1000 persons, compared to high‐income countries. 5 The reported data on the prevalence and incidence were characterized by significant heterogeneity. The heterogeneity was attributed to socioeconomic, medical, and cultural factors. 6

In Morocco, data on epidemiology of epilepsy are lacking. The conduct of this research in the Moroccan context is relevant because epilepsy constitutes a major public health problem by its neurobiological, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences. 7 Through this study, we aimed to estimate the prevalence of active and lifetime epilepsy in Morocco. Moreover, we studied epilepsy prevalence according to sociodemographic parameters.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Targeted population

2.1.1. Inclusion criteria

This study estimated the prevalence of epilepsy in the Moroccan population. According to the Haut Commissariat au Plan, the population was estimated at 36896313, in 2023 (Institutional website of the High Commission for Planning of the Kingdom of Morocco, s. d.). This study was conducted on Moroccan people of all ages and sexes. 8

2.1.2. Exclusion criteria

We excluded people who refused to participate, and closed institutions (All phone numbers attributed to private and public officers [hospitals, schools, companies, ministries…]) from this study. In addition, people who cannot be reached, foreigners, and people unable to answer the questions were excluded from this study.

2.2. Sampling process

The sample size was calculated using sample size calculation formula for cross‐sectional surveys for qualitative variable. 9

Z1 a/2 = Is standard normal variate type 1 error at 5% (P < 0.05). As in majority of studies, p values are considered significant below 0.05, hence, Z1 a/2 = 1.96 is used in formula.

p = Expected proportion in population based on previous studies or pilot studies (P = 0.1).

d = Absolute error or precision =0.4%.

N = 2611 and sample size has been increased by 20% = 3184.

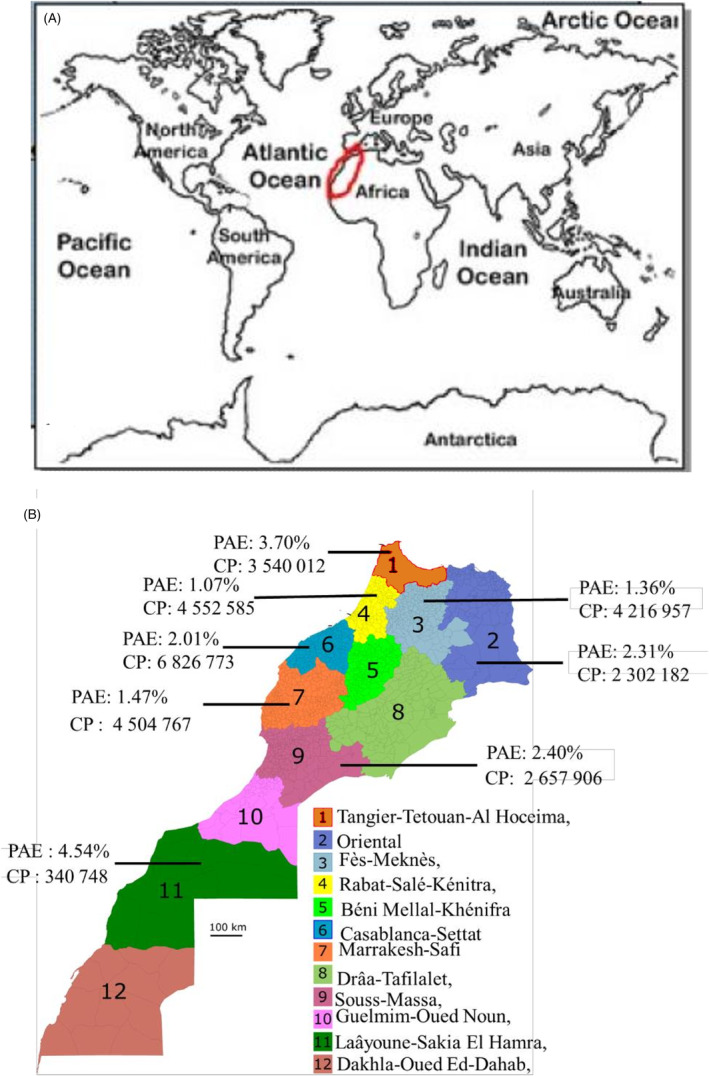

The random selection of individuals' landline telephone numbers was based on a nationally representative sample determined by the epidemiologist. Data were taken from eight representative regions among 12 regions between June 2021 and December 2022 (23.9% in Casablanca‐Settat, 12.3% in Tanger‐Tétouan‐ Al Hoceima, 7.9% in Oriental, 14.2% in Fès‐ Meknès, 15.6% in Rabat‐Salé‐Kénitra, 15.4% in Marrakech‐Safi, 9.4% in Souss‐Massa, and 1.3% in Laâyoune‐Sakia El Hamra). Twelve regions make up Morocco, and those areas are further divided into 75 provinces according to Decree No. 2.15.10 of February 20, 2015. Each of these regions has interesting geographical and historical characteristics.

The Laâyoune‐Sakia El Hamra is a Sahara region situated in the southern half of Morocco. According to statistics from 2014, Laâyoune‐Sakia El Hamra has a 140 018 km2 area and 367 758 residents. Laayoune is the capital of the region. Souss‐Massa region, a strip in the middle of the nation, covers a surface area of 51 642 km2 and recorded a population of 2 676 847. The capital of the region is Agadir. The Oriental region is in the northeastern corner of the nation. The Oriental region has a population of 2 314 346 and covers an area of 90 127 km2. Oujda deserves as the regional capital. The Tanger‐Tetouan‐Al Hoceima region is situated in the far north of the nation. It faces the Strait of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean Sea. About 3 556 729 people live on a surface of 15 090 km2. The city of Tangier is the regional capital. The Fès‐Meknès region is situated in northern inland Morocco. According to statistics from 2014, Fès‐Meknès has a surface area of 40 075 and a population of 4 236 892. Fez, the historic city deserves to be the region's capital.

The Rabat‐Salé‐Kénitra region is situated in the northwest. It faces the Atlantic Ocean. According to statistics from 2014, Rabat‐Salé‐Kénitra covers an area of 18 194 km2 and recorded a population of 4 580 866. Rabat is the regional capital and the administrative capital of Morocco. Casablanca‐Settat region, the greatest economic region is situated in the nation's northwest. A total of 686 1739 people live in the 20 166 km2, according to population statistics from 2014. Casablanca deserves as the regional capital. Marrakesh‐Safi is situated in the northwestern. A total of 4 520 569 people live in the 39 167 km2, according to population statistics from 2014. Marrakesh, the famous Moroccan touristic city deserves as the regional capital.

2.3. Procedure and data collection

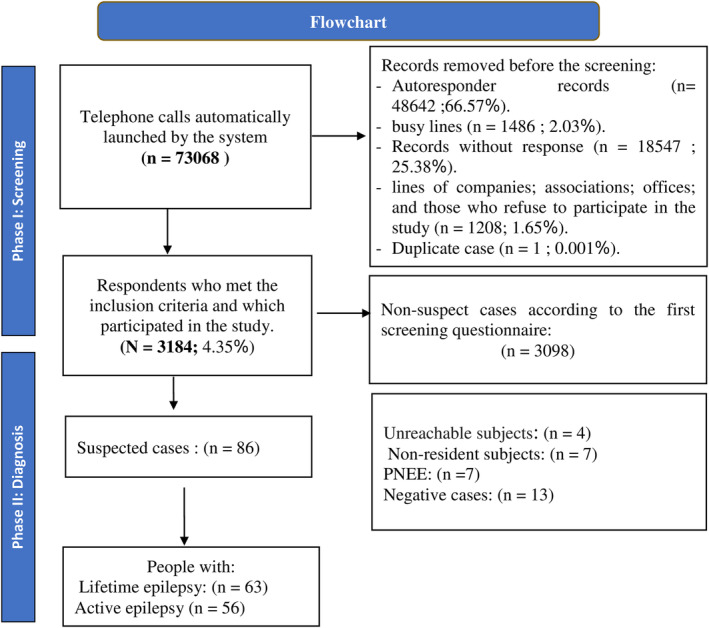

The flowchart in the Figure 1 summarizes all steps followed to collect data:

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart demonstrating the study process and steps. PNES, psychogenic nonepileptic events.

2.3.1. Screening step

The national languages for Morocco are Arabic and Tamazight. Call Center Nidae Almakfoufine Fez, a professional and recognized call center, conducted a nationwide telephone survey using a validated screening questionnaire consisting of nine questions. 1 This step allowed us to select cases likely to have epilepsy. The rate of response reached 72.5%. Moreover, the participants' sociodemographic useful information and the phone numbers of the suspected cases were collected to contact them during the second phase of the investigation.

2.3.2. Confirmation step

This step was conducted in two stages. During the first stage, a second telephone survey 10 for suspected cases was conducted by a team of physicians under the direction of an epileptologist. At this step, we aimed to perform the diagnosis of epilepsy. The second stage of this step concerned suspected people with epilepsy whose interrogation did not allow the confirmation of the disease because of a lack in their medical records. These cases were referred to a neurologist practicing in their region of residence. These cases benefited from neurological examinations (CT scan, MRI, and EEG). Suspected patients were oriented to referral neurologists. To perform “psychogenic non epileptic events (PNEE)” diagnosis, clinician reviewed the video recording or in person, showing typical signs of PNEE. Patients had no epileptiform activity on routine EEG.

2.4. Ethical considerations

The investigators who made the calls were the ones who obtained the verbal consent for the phone survey and the follow‐up diagnostic phone call. This study has been registered as thesis project and then it was approved by the Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah University Doctoral Studies Center. The study did not present any potential risk to the participants. The respect for participants' self‐determination was guaranteed. The investigators obtained informed consent from each participant before taking part in the study. They offered a full explanation to participants about the study objectives, its progress, the risks involved, and the free choice to participate and withdraw at any time. Similarly, information collected during all phases of the study was stored confidentially in a database accessible only to the study team members.

2.5. Statistical analysis

This was a population‐based study in Morocco. We fixed the confidence interval and the precision at <0.05 and 2% to calculate the active and lifetime epilepsy prevalence. We initially selected six variables for the analysis: age, sex, occupation, level of education, and finally the area (urban/rural). This list was largely inspired by the recommendations established in the international literature on this topic of the potential risk factors at the origin of epilepsy.

Conventional univariate binary logistic regression with proportional or nonproportional odds was used to examine the association degree of the two dimensions of epileptic (absence/presence) on each explanatory variable studied. We have thus adopted the parsimonious regression model, with the hope of obtaining a model that is both more efficient and more adjusted. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from the best‐fitted model. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical software used for analyses: The data analysis was carried out with the software R version 3.6.1.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

Table 1 summarized the sociodemographic characteristics of the whole sample respondents and confirmed cases. The total number of participants who participated in this study was 3184. The outcome of referrals was performed by recorded neurologists. The participants' mean age was 44.43 ± 16.82 years and the mean age of the total number of people with epilepsy was 35.53 ± 21.36 years.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of total respondents (N = 3184) and persons with epilepsy (n = 63).

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Whole sample N = 3184 | Persons with epilepsy N = 63 | P a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Number (%) | Total | Number (%) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 3084 | 910 (29.5) | 62 | 36 (58.1) | <0.001 |

| Female | 2174 (70.5) | 26 (41.9) | |||

| Age groups (years) | |||||

| <18 | 2323 | 74 (3.2) | 60 | 15 (25) | <0.001 |

| ≥18 | 2249 (96.8) | 45 (75) | |||

| Residence | |||||

| Urban | 2639 | 2355 (89.2) | 63 | 52 (82.5) | 0.82 |

| Rural | 284 (10.8) | 11 (17.5) | |||

| Profession of adults | |||||

| Farmer | 3145 | 2 (0.1) | 63 | 0 (0) | – |

| Trader | 39 (1.2) | 1 (1.6) | |||

| Student | 234 (7.4) | 6 (9.5) | |||

| Officials and employees | 396 (12.6) | 5 (7.9) | |||

| Farmer | 224 (7.1) | 2 (3.2) | |||

| Liberal profession | 74 (2.4) | 2 (3.2) | |||

| Retirement | 283 (9.0) | 6 (9.5) | |||

| Unemployed | 1112 (35.4) | 25 (39.7) | |||

| Others | 781 (24.8) | 16 (25.4) | |||

| The educational level of adults | |||||

| Illiterate | 3184 | 225 (7.1) | 63 | 7 (11.1) | – |

| Primary | 294 (9.3) | 11 (17.5) | |||

| Secondary | 730 (23.2) | 19 (30.2) | |||

| University | 986 (31.3) | 11 (17.5) | |||

| Other | 913 (29.0) | 15 (23.8) | |||

Note: Bold P values indicate a signinificant difference between compared groups.

P: Comparison between people with epilepsy group and whole participants' group according to sociodemographic parameters by Chi‐square test (P significant <0.01).

3.2. Screening tools and validation diagnosis

From a database of telephone directories, we launched automatic telephone calls with randomly selected numbers. A total of 3184 respondents participated in this study and answered the screening questionnaire. 1 The sensitivity and specificity of the screening test used in the first step of the pilot study were 100% and 77%, respectively, in our population.

In the diagnostic phase, neurologists reinterviewed all 86 suspected cases using a second confirmative diagnosis questionnaire. 10 They performed lifetime epilepsy diagnosis in 63 persons and active epilepsy in 56 participants. Forty‐nine cases had EEG and MRI, and they were on antiseizure medications. The cases whose diagnosis was uncertain were referred to neurologists practicing in their region of residence. They confirmed or rejected the diagnosis.

3.3. Prevalence of active and lifetime epilepsy

Out of the 3184 households surveyed, 56 were diagnosed with active epilepsy and 63 with lifetime epilepsy. Then the prevalence of active and lifetime epilepsy was 17.6 (95% CI; 13.3–22.8) per 1000 and 19.8 (95% CI; 15–24.6) per 1000, respectively. Table 2 shows the prevalence of active and lifetime epilepsy, and types of epilepsy according to gender, age, and residence. Figure 2 discloses the prevalence of active and lifetime epilepsy in all Moroccan regions covered by the study. We calculated the active epilepsy prevalence by age class and sex. We found an OR of 0.31 (0.17–0.55; P < 0.001) among people aged 30–60 years, and an OR of 0.37 (0.18–0.74; P = 0.007) for people older than 60 years in comparison to the class age reference (0–30 years). The risk to have epilepsy in men was threefold higher than in women with an OR of 3.1 (1.82–5.34; P < 0.001).

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of active, lifetime epilepsy, and types of epilepsy according to gender, age, and residence.

| All N = 63 | Gender | Age groups (years) | Residence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female n = 26 | Male n = 32 | <18 n = 15 | ≥18 n = 45 | Urban n = 46 | Rurale n = 5 | ||

| Lifetime epilepsy | 7 (11.1%) | 2 (7.7%) | 4 (12.5%) | 1 (6.7%) | 5 (11.1%) | 7 (15.2%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Active epilepsy | 56 (88.9%) | 24 (92.3%) | 28 (87.5%) | 14 (93.3%) | 40 (88.9%) | 39 (84.8%) | 5 (100%) |

| Generalized epilepsy | 45 (71.4%) | 22 (84.6%) | 19 (59.4%) | 11 (73.3%) | 31 (68.9%) | 31 (67.4%) | 5 (100%) |

| Focal epilepsy | 16 (25.4%) | 3 (11.5%) | 12 (37.5%) | 2 (13.3%) | 14 (31.1%) | 13 (28.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Focal and generalized epilepsy | 2 (3.2%) | 1 (3.8%) | 1 (3.1%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) |

FIGURE 2.

(a) Geographical situation of Morocco and (b) the relevant active epilepsy prevalence according to Moroccan regions in 2022. CP, Civic population; PAE, Prevalence of Active Epilepsy.

3.4. Cares and traditional practice

Among the 63 persons with epilepsy, 34 have resorted to traditional practices to cure their epilepsy which confirmed a great unawareness of the disease in our population. Up to 93.65% were under antiepileptic drugs and 84.12% were regular in taking their medication, in favor of high treatment adherence. In addition, 26.98% were under two or more antiepileptic drugs. That confirmed existing data on the prevalence of drug‐resistant epilepsy.

4. DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, no relevant population‐based studies following International League against Epilepsy (ILAE) recommendations in epilepsy have been completed in Morocco. 11 This is the first study to estimate the active and lifetime prevalence of epilepsy in Morocco according to the international recommendations of the ILAE. We collected data from 3184 participants from eight out of 12 Moroccan regions using a nationwide telephone diagnosis questionnaire. The prevalence of lifetime and active epilepsy were 19.8 (15–24.6) and 17.6 (13.3–22.8) per 1000, respectively. We included both children and elderly subjects. The estimates in prevalence were similar between almost studied regions. The highest prevalence was shown in the Laayoune Region, a Moroccan Sahara area with lower population density, and the lowest prevalence was found in the Rabat region characterized by higher urban population density. Itri et al. 12 published prevalence data of epilepsy (11 per 1000 people) restricted among children in Casablanca city. 12 Studies including children and adult populations showed higher prevalence than pediatric studies. 13 , 14 , 15 Since 1998, no other studies on epilepsy prevalence in Morocco have been done.

In the Standards for epidemiologic studies and Surveillance of Epilepsy performed by the ILAE epidemiology commission, surveys conducted by telephone were encouraged but the validity and clinical detail from self‐reports and proxy reports must be considered. 11 The household telephone availability in Morocco allows us to conduct these surveys by telephone in a representative sample of households. In the telephonic surveys, the response rate was higher than “door to door” studies. 16 Indeed, our study showed a response rate of 72.5% higher than that observed in the Epiberia study. 17

Active epilepsy in our study was similar to that in low–middle‐income countries, with over 10 per 1000 persons, compared to high‐income countries. 5 It was greater than the prevalence in Northern Mediterranean countries like Spain with 5.6 per 1000 (95% CI: 2.8–10.6) in the Epiberia study, 17 and in a French population with 5.4 per 1000 (95% CI, 4.7–6.0). 18 The active prevalence reached 4.61 (95% CI, 4.34–4.90) in the United States, and 5.15 (95% CI, 5.05–5.25) in the United Kingdom. 5

Few studies on epilepsy prevalence were performed in Southern Mediterranean countries. The active prevalence rate of epilepsy was 2.12/1000 in Upper Egypt, while the lifetime prevalence was 12.46/1000. 19 Our active epilepsy prevalence estimates were less than that found in other African countries, like Ethiopia with 29.46 per 1000 persons (95% CI 21.16–41.03), 20 and Cameroon with 104.97 per 1000 persons (95% CI 68.60–160.63). 21

Although nearly 80% of people with epilepsy live in low‐ and middle‐income countries with limited resources, generalizing the statement of “prevalence is similar in LMICs,” is not entirely true. If we make a comparison of the prevalence of epilepsy based on region, for example, Latin America, Asia, and sub‐Saharan Africa, the prevalence varies throughout each region. For example, Asian LMICs has lower lifetime, and active epilepsy prevalence are slightly lower. 22 The prevalence estimates in Morocco ranged between northern Mediterranean and sub‐Saharan Africa.

In a meta‐analysis, Bell et al. 23 found that the range of estimated prevalence of epilepsy may be broadly similar throughout the world, but the comparison was limited by the scarcity of door‐to‐door studies and by variations in the definitions of active epilepsy. 23 The author argues that any discrepancies between incidence and prevalence are primarily caused by the higher premature death rate among people with epilepsy in low‐income countries. 23

The clinical characteristics of patients in our study were like other surveys. We found significant differences in prevalence according to age and sex. Epilepsy predominates among younger people (<30 years) than older people (>30 years) and, among males than females. Early childhood and infancy had substantially higher age‐specific prevalence estimates of epilepsy, which rapidly declined with age. Moreover, rural areas and limited sample sizes were also linked to higher prevalence estimates. 24 Males and rural areas had greater prevalence rates in a Chinese study in 2012. 25

In our population, symptomatic and structural epilepsies were predominant, although generalized seizures predominate over focal seizures. Similarly, a higher proportion of generalized seizures was reported in other prevalence studies (Pi et al., 2012). 19 Indeed, the prevalence of focal epilepsy ranged from 20% to 66% of incident epilepsies. Several prevalence and incidence studies report a preponderance of seizures of unknown cause. 6

Our study disclosed some limitations. First, the survey was not a door‐to‐door study. Second, rural areas were underrepresented in our study because of the difficulty in the access of landline phones. Finally, the sample size was limited.

5. CONCLUSION

We performed a telephonic national survey of the general population according to the international recommendations of the ILAE. We included both children and elderly subjects. The rates of active and lifetime epilepsy prevalence in Morocco ranged between Asian and sub‐Saharan Africa low‐ and middle‐income countries.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Souirti Zouhayr and Janati Idrissi Abdelkrim: Principal investigators, questionnaires translation, writing—original draft, original drafting, validation, formal analysis, project administration, conceptualization, methodology, data collection, practical design, interpretation of the data, writing, final article approval, and article submission processing. Hmidani, Mohammed; Questionnaires translation, writing—original draft, original drafting, validation, formal analysis, project administration, conceptualization, methodology, data collection, practical design, interpretation of the data, and writing. Lamkadddem Abdelaziz; Questionnaires translation, writing—original draft, original drafting, validation, formal analysis, project administration, conceptualization, methodology, data collection, and practical design. Khabbach, Kawtar, Belakhdar Salma, Charkani Doae, Lahmadi Nabila, El Akramine Maroua, Erriouiche Samira, Berrada, Asmae and Ahniba Asmae: Questionnaires translation, original drafting, validation, conceptualization, methodology, data collection, and practical design. Omari Mohammed, El Fakir Samira, Tachfouti Nabi, Benmansour Youssef, and Filali Zegzouti Younes: Statistical analysis, sampling, conceptualization, and methodology. Rafai Mohammed Abdoh, Chahid Imane, Meriam Bentahar, Jilla Mariam, Ghaname Aayad, Kissani Najib, Lakhdar Abdelhakim, Belfkih Rachid, and Aggouri Mohamed: Validation, conceptualization, methodology, and data collection. Ouazzani Reda and Chahidi Abderrahmane: Validation, conceptualization, methodology, data collection, project administration, conceptualization, final article approval, and article submission processing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Neither of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was funded by the Moroccan Society of Neurophysiology “SMNPH.”

ETHICAL APPROVAL

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Initial verbal consent is a necessary condition for participating in this research and answering the questions that comprise it. All participants in this telephone interview were informed that their participation in this research is voluntary and that they can stop at any time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all participants for the survey we conducted that allowed us to originate the results reported in this article.

Souirti Z, Hmidani M, Lamkadddem A, Khabbach K, Belakhdar S, Charkani D, et al. Prevalence of epilepsy in Morocco: A population‐based study. Epilepsia Open. 2023;8:1340–1349. 10.1002/epi4.12802

REFERENCES

- 1. Tallawy HNE, Farghaly WM, Rageh TA, Saleh AO, Mestekawy TA, Darwish MM, et al. Construction of standardized Arabic questionnaires for screening neurological disorders (dementia, stroke, epilepsy, movement disorders, muscle, and neuromuscular junction disorders). Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2245–2253. 10.2147/NDT.S109328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Epilepsy. (2023) . Consulté 19 février 2023, à l'adresse . 2023. https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/epilepsy

- 3. Beghi E. The Epidemiology of epilepsy. Neuroepidemiology. 2020;54(2):185–191. 10.1159/000503831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd‐Allah F, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–1259. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fiest KM, Sauro KM, Wiebe S, Patten SB, Kwon C‐S, Dykeman J, et al. Prevalence and incidence of epilepsy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of international studies. Neurology. 2017;88(3):296–303. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Banerjee PN, Filippi D, Hauser WA. The descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy‐a review. Epilepsy Res. 2009;85(1):31–45. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fisher RS, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, et al. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the international league against epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia. 2005;46(4):470–472. 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Site institutionnel du Haut‐Commissariat au Plan du Royaume du Maroc. (s. d.) . Site institutionnel du Haut‐Commissariat au Plan du Royaume du Maroc. Consulté 20 février à l'adresse. 2023. https://www.hcp.ma

- 9. Charan J, Biswas T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35(2):121–126. 10.4103/0253-7176.116232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Preux PM. Questionnaire in a study of epilepsy in tropical countries. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2000;93(4):276–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thurman DJ, Beghi E, Begley CE, Berg AT, Buchhalter JR, Ding D, et al. Standards for epidemiologic studies and surveillance of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011;52(s7):2–26. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03121.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Itri M, Hadj KH. Enquéte épidémiologique sur les épilepsies de l'enfant. Les Cahiers du Médecin. 1998;1(9):36–38. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mohammad QD, Saha NC, Alam MB, Hoque SA, Islam A, Chowdhury RN, et al. Prevalence of epilepsy in Bangladesh: results from a national household survey. Epilepsia Open. 2020;5:526–536. 10.1002/epi4.12430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Farghaly W, Abd Elhamed MA, Hassan E, et al. Prevalence of childhood and adolescence epilepsy in upper Egypt (desert areas). Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2018;54:34. 10.1186/s41983-018-0032-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aaberg KM, Gunnes N, Bakken IJ, Søraas CL, Berntsen A, Magnus P, et al. Incidence and prevalence of childhood epilepsy: a Nationwide cohort study. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):e20163908. 10.1542/peds.2016-3908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rodriguez HP, von Glahn T, Rogers WH, Chang H, Fanjiang G, Safran DG. Evaluating patients' experiences with individual physicians: a randomized trial of mail, internet, and interactive voice response telephone administration of surveys. Med Care. 2006;44(2):167–174. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196961.00933.8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Serrano‐Castro PJ, Mauri‐Llerda JA, Hernández‐Ramos FJ, Sánchez‐Alvarez JC, Parejo‐Carbonell B, Quiroga‐Subirana P, et al. Adult prevalence of epilepsy in Spain: EPIBERIA, a population‐based study. Scientific World Journal. 2015;2015:602710. 10.1155/2015/602710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Loiseau J, Loiseau P, Guyot M, Duche B, Dartigues J‐F, Aublet B. Survey of seizure disorders in the French southwest. I Incidence of Epileptic Syndromes. Epilepsia. 1990;31(4):391–396. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1990.tb05493.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fawi G, Khedr EM, El‐Fetoh NA, Thabit MN, Abbass MA, Zaki AF. Community‐based epidemiological study of epilepsy in the Qena governorate in upper Egypt, a door‐to‐door survey. Epilepsy Res. 2015;113:68–75. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Almu S, Tadesse Z, Cooper P, Hackett R. The prevalence of epilepsy in the Zay society, Ethiopia—an area of high prevalence. Seizure. 2006;15(3):211–213. 10.1016/j.seizure.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prischich F, de Rinaldis M, Bruno F, Egeo G, Santori C, Zappaterreno A, et al. High prevalence of epilepsy in a village in the Littoral Province of Cameroon. Epilepsy Res. 2008;82(2):200–210. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Trinka E, Kwan P, Lee B, Dash A. Epilepsy in Asia: disease burden, management barriers, and challenges. Epilepsia. 2019;60(S1):7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bell GS, Neligan A, Sander JW. An unknown quantity—the worldwide prevalence of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55(7):958–962. 10.1111/epi.12605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ngugi AK, Bottomley C, Kleinschmidt I, Sander JW, Newton CR. Estimation of the burden of active and lifetime epilepsy: a meta‐analytic approach: estimation of the burden of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2010;51(5):883–890. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02481.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pi X, Cui L, Liu A, Zhang J, Ma Y, Liu B, et al. Investigation of prevalence, clinical characteristics and management of epilepsy in Yueyang city of China by a door‐to‐door survey. Epilepsy Res. 2012;101(1–2):129–134. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2012.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]