Abstract

A male, 32 years of age, presented with dysuria and abdominal pain, but no gross hematuria. He emigrated three years earlier from Somalia, East Africa, and was currently employed as a poultry processor in a rural Wisconsin community. The patient denied any trauma, sexual activity, or family history of significant illness. Abdominal and genitourinary exams were normal with negative tests for gonococcus and chlamydia. Urinalysis demonstrated microhematuria. A urogram and retrograde pyelogram revealed a mildly dilated right ureter down to the ureterovesical junction. Cystoscopy showed punctate white lesions on the bladder urothelium. Ureteroscopy was used to biopsy abnormal tissue in the distal ureter and bladder. Biopsy tissue demonstrated deposits of Schistosoma haematobium eggs. No ova were seen in collected urine specimens. The patient was successfully treated with praziquantel and will be monitored for sequelae of the disease.

Schistosomiasis (Bilharziasis) can be expected to be seen with increasing frequency in the United States with the continuing influx of immigrants and refugees, as well as the return of travelers and soldiers from endemic areas. While no intermediate snail host exists for the transmission of Schistosoma sp. in the United States, the continued importation of exotic animals including snails from Africa, as well as the ability of schistosomes to shift host species warrants concern. Additionally, increasing disease associated with non-human bird schistosomes of the same genus seen in the midwestern United States is occurring throughout Europe. One should be aware that praziquantel may not always be available or effective in the treatment of schistosomiasis. It behooves the practicing clinician to remain updated on the status of this widespread zoonosis.

Keywords: Schistosomiasis; Ureteral obstruction; Emigration and Immigration; Praziquantel; Zoonoses; Communicable diseases, emerging; Health services accessibility

INTRODUCTION

The population demographics of the United States are changing. As an example, the population of political refugees within Wisconsin has risen from 30,000 in 1990 to more than 60,000 in 2002 and continues to increase.1 Most of these refugees originate from Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, and Africa.

We present the case of a ureteral obstruction in a Somalian refugee caused by a disease entity not commonly seen in the American Midwest. The case serves to emphasize the importance of knowledge of tropical medicine, even in the northern tier of the United States.

CASE REPORT

A male, 32 years of age, presented with dysuria and abdominal pain. He had no other gastrointestinal symptoms. There had been no gross hematuria. The patient denied any trauma or sexual activity. The patient had been treated at another clinic with Rocephin® and oral antibiotics. Review of symptoms was negative for any ophthalmic or rheumatologic complaints. Family history was negative for any significant illnesses. The patient was a non-smoker and had been working at a poultry processing plant since emigrating from Somalia 3 years ago. Physical exam revealed a healthy male. Abdominal and genitourinary exam were normal.

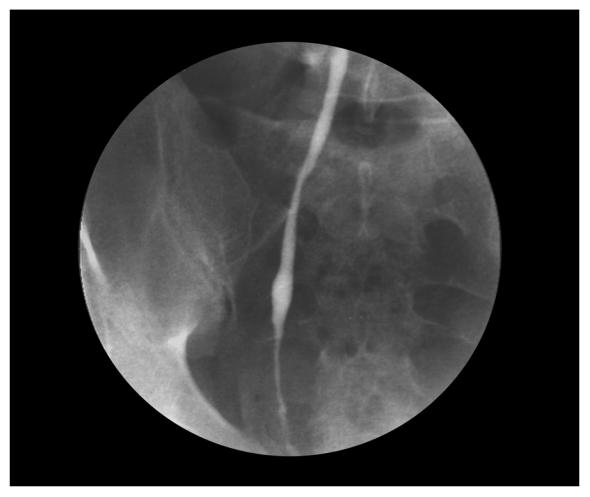

Urinalysis demonstrated 6 to 10 WBCs, trace leukocyte esterase, microhematuria, and negative nitrates. A urine culture was negative. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was negative for gonococcus and chlamydia. Because of the microscopic hematuria, an intravenous urogram was obtained. Pertinent findings include a mildly dilated right ureter down to the ureterovesical junction (figure 1). A cystoscopic examination showed that the bladder urothelium was dotted with punctate white lesions. A retrograde pyelogram demonstrated irregularity in the distal 2 cm of the right ureter (figure 2). Ureteroscopy showed irregular, heaped-up tissue in the distal ureter. This tissue, as well as the abnormal tissue in the bladder, was biopsied. Pathologic examination of the biopsy tissue showed classic bilharzial ova (figure 3). Collected urine was not found to have any ova.

Figure 1.

An intravenous urogram displays a mildly dilated right ureter (arrow) down to the ureterovesical junction.

Figure 2.

Retrograde pyelogram demonstrating irregularity in the distal 2 cm of the right ureter.

Figure 3.

Histopathology of the abnormal urinary tract tissue obtained on ureteroscopy reveals Schistosoma haematobium eggs with their characteristic terminal spine (arrow).

The patient was treated with praziquantel 20 mg/kg every 6 hours for 1 day. He vomited with the first course of praziquantel, losing some of the dose, so the course was repeated. Approximately one month later symptoms of right lower quadrant and flank pain had returned with sweating, urinary frequency, and occasional urgency, likely the result of infection and/or recurrence of ureteral stenosis that will require further management after assessment by intravenous urogram. He is also being monitored for sequelae of this disease.

A follow-up intravenous pyelogram was performed six months after initial presentation and treatment. No evidence of obstruction or filling defect was noted.

DISCUSSION

Incidence

Schistosoma sp. infect 250 million people worldwide.2 Schistosomiasis (also called Bilharziasis after the German tropical disease specialist, Theodore M. Bilharz, 1829–1862) is second only to malaria in parasitic disease morbidity. Approximately 500 to 600 million people in tropical and subtropical countries are at risk, and of those infected, 120 million are symptomatic with 20 million having severe manifestations.3 Schistosomiasis is endemic in many countries, not only in sub-Saharan Africa, but the far East, South and Central America, and the Caribbean.

Endemic distribution

Ten species of schistosomes can infect humans, but a vast majority of infections are caused by Schistosoma mansoni, S. japonicum, and S. haematobium.4 Of all people suffering from schistosomiasis, 85% live in sub-Saharan Africa where S. mansoni, S. haematobium, and S. intercalatum are endemic.5,6 S. mansoni, S. intercalatum, and S. japonicum largely cause hepatobiliary and gastrointestinal symptoms, while S. haematobium causes urogenital symptoms.

Bilharziasis is endemic throughout Africa, but its distribution is focal and constantly shifting as open irrigation canals spread.7–9 The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is funding a 4-year schistosomiasis control initiative in Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger during which 15 million people will be treated.10

As recently as 2000, an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine stated that schistosomiasis, particularly S. haematobium, is not thought to occur in Somalia.11 However, review of the tropical medicine literature reveals that S. haematobium is endemic to Somalia and presents a long-standing health problem there.9,12–19

Shifting demographics

In the United States, it is estimated that at least 400,000 individuals are infected. Most of these are immigrants, but travelers including military, expatriates, and civilian contractors have been infected as well.20–31 Southern Iraq is an area endemic for S. haematobium, and it may be expected that returning military personnel, while stationed there, may have contracted infections upon exposure to fresh water.27,32–35

Within the past decade, the United States has seen a large influx of refugees from Somalia as a consequence of continuing civil war.36,37 Minneapolis, Minnesota, is believed to have the largest Somali immigrant population in the United States with between 6,000 and 30,000 people from that nation, most of whom arrived within the last 12 years.38 Initially placed by religious aid agencies, Minnesota's draw has been through available jobs and low housing costs. In Somali refugee camps worldwide, the word “Minneapolis” has come to symbolize a shot at the American dream. Somalis who first located elsewhere in the United States moved to the state because of the growing community there, the decent cost of living, and good job opportunities.

Lately, the slowing economy and housing shortages are driving some of these refugees to Columbus, Ohio, which is believed to have the second largest Somali immigrant population in the country, estimated at 15,000. In Milwaukee, there is a Somalian community of between 250 and 500 people. In Barron, Wisconsin, population of 3,000, more than 300 Somalian immigrants have settled to work year-round at a turkey processing plant.39,40 Further increases in this population can be expected as the United States opens its borders to close relatives of those already here.41 Along with the influx of people, the manifestation of diseases endemic to that part of the world can be expected to be seen in the United States.

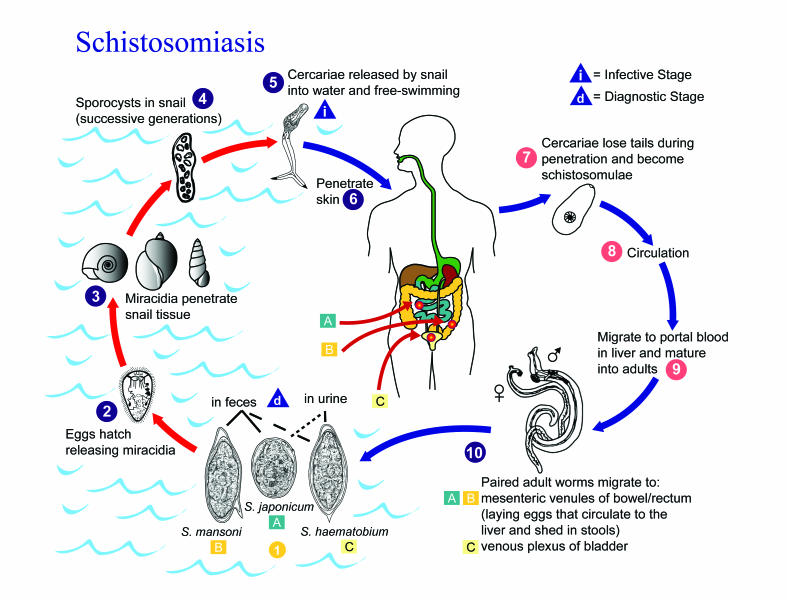

Life cycle

The life cycle and pathophysiology of S. haematobium has been reviewed extensively in the literature.42 Briefly, when eggs are excreted into fresh water, they hatch to release motile, ciliated miracidia (embryos) that penetrate aquatic bulinid snails, the intermediate host. Cercaria (larvae) emerge from the snails and penetrate the skin of humans in contact with the water (figure 4). The cercariae migrate to the lungs and liver, and after 6 weeks, the mature worms mate and migrate into the pelvic veins to begin oviposition. The eggs penetrate small, thin-walled vessels in the genitourinary system. During the active phase viable adult worms deposit eggs that induce a granulomatous response with the formation of polypoid lesions. During this phase eggs are excreted. An inactive phase follows the death of the adult worms.21 No viable eggs are present in the urine, and large numbers of calcified eggs are present in the wall of the bladder and other affected tissues. As fibrosis progresses, polypoid patches flatten into finely granular patches.43

Figure 4.

Eggs are eliminated with feces or urine 1. Under optimal conditions the eggs hatch and release miracidia 2, which swim and penetrate specific snail intermediate hosts 3. The stages in the snail include 2 generations of sporocysts 4 and the production of cercariae 5. Upon release from the snail, the infective cercariae swim, penetrate the skin of the human host 6, and shed their forked tail, becoming schistosomulae 7. The schistosomulae migrate through several tissues and stages to their residence in the veins (8, 9). Adult worms in humans reside in the mesenteric venules in various locations, which at times seem to be specific for each species 10. For instance, S. japonicum is more frequently found in the superior mesenteric veins draining the small intestine A, and S. mansoni occurs more often in the superior mesenteric veins draining the large intestine B. However, both species can occupy either location, and they are capable of moving between sites, so it is not possible to state unequivocally that one species only occurs in one location. S. haematobium most often occurs in the venous plexus of bladder C, but it can also be found in the rectal venules. The females (size 7 to 20 mm; males slightly smaller) deposit eggs in the small venules of the portal and perivesical systems. The eggs are moved progressively toward the lumen of the intestine (S. mansoni and S. japonicum) and of the bladder and ureters (S. haematobium), and are eliminated with feces or urine, respectively 1. Pathology of S. mansoni and S. japonicum schistosomiasis includes: Katayama fever, hepatic perisinusoidal egg granulomas, Symmers' pipe stem periportal fibrosis, portal hypertension, and occasional embolic egg granulomas in the brain or spinal cord. Pathology of S. haematobium schistosomiasis includes: hematuria, scarring, calcification, squamous cell carcinoma, and occasional embolic egg granulomas in brain or spinal cord.

Human contact with water is thus necessary for infection by schistosomes. Various animals, such as dogs, cats, rodents, pigs, horse and goats, serve as reservoirs for S. japonicum, and dogs for S. mekongi.

Geographic Distribution:

Schistosoma mansoni is found in parts of South America and the Caribbean, Africa, and the Middle East; S. haematobium in Africa and the Middle East; and S. japonicum in the Far East. Schistosoma mekongi and S. intercalatum are found focally in Southeast Asia and central West Africa, respectively.

(Figure provided by Alexander J. da Silva and Melanie Moser for copyright-free dissemination through the Public Health Image Library of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Legend obtained through the Division of Parasitic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Symptomatic effects

A very vivid description of the symptomatic effects of S. haematobium infection was provided in an early case report. In 1944, Dr. Claude H. Barlow infected himself with schistosomiasis in order to bring viable eggs to Johns Hopkins University for study. He reported the consequences of his voluntary infection with S. haematobium in 1949.44 His intense suffering is well described. In the early stages of infection, cough, headache, loss of appetite, various aches and pains, and often difficulty in breathing followed the initial skin irritation. In more advanced infection, nausea was common, accompanied by hematuria and in some cases renal obstruction.

Clinical findings of hematuria, leukocyturia, urinary tract complaints, tender abdomen, and supra-pubic tenderness are associated with S. haematobium infections,45 but the clinical outcome of infection is variable, ranging from mild symptoms to chronic iron deficiency and anemia, to scarring and deformity of the ureters and bladder, to chronic bacterial superinfection, to severe damage of urinary tract organs, and ultimately to renal failure.46–50

Duration of infection

After maturing, schistosome worm pairs live in their definitive host venous system and engage in egg-laying for many years, even decades.51,52 This means that patients may present with symptoms years after having immigrated from or visited endemic regions.21 The eggs, rather than the adult worms, play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of schistosome infection.

Ureteral involvement

Obstructive uropathy is the most common and dangerous complication of S. haematobium infection of the interstitial and juxtavesicular portions of the ureter.21,24,53–56 Chronic renal failure and immune-complex-mediated glomerulonephritis may result.57–59 The urinary collecting system, the ureters, bladder, seminal vesicles, prostate gland, urethra, vas deferens, and testes may become involved.60,61

In the ureter, mostly the lower portion is affected because of the blood supply anatomy. Eggs are found in all layers of the ureter, and cause mural fibrosis, loss of the muscle layer, and fibrosis. Stricture may occur.

Acute symptoms may include renal colic with pyelonephritis and hydronephrosis.62 Long-standing obstruction may present with silent obstruction or anuria. Most cases of ureteral involvement also have bladder involvement.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of urinary tract schistosomiasis is based on history and clinical suspicion followed by laboratory studies. These may include the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), serum antigens, and demonstration of ova in the urine. Many cases are diagnosed by endoscopy and biopsy.

Traditionally for S. haematobium, microscopic examination of urine and seminal fluids reveal eggs with characteristic species-specific morphology.11,44,63,64 For best results, urine collections should be made between 10:00 am and 2:00 pm to ensure maximum yield.65 Another way to increase yield of eggs in the urine is to have the patient go for a short run or walk just before the urine is passed to facilitate the shedding of the eggs from the bladder mucosa.29 Samples may be centrifuged or filtered on membranes to enhance the chances of finding eggs.66–68

Detection of eggs in stool samples is typically used in the diagnosis of S. mansoni,69 but S. haematobium eggs may also occasionally be found in the stool. Egg production can be low and sporadic so the risk of missing the diagnosis by egg detection alone is high.45

Ultrasonography has been used as a diagnostic technique for assessment of urinary tract morbidity.49,50,70–73 Bladder pathology can include thickening, the presence of polyps, or the existence of masses protruding into the lumen. Kidney dilation may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. Urograms can reveal filling defects.22

Cystoscopic examination generally reveals masses and/or punctuate white calcifications without ulceration or necrosis. Similar lesions are seen in the uterus upon pelviscopic examination when the reproductive tract is involved.21 Urinary eosinophil cationic protein has been shown to correlate well with the extent of bladder pathology in S. haematobium infections.74

Immunodiagnostic assays have been developed to detect circulating antibodies to semi-purified or fractionated antigens75–81 and parasite circulating antigens in different host body fluids.82–88 Falcon assay screening test (FAST)-ELISA and immunoblot assays for specific antibodies to S. mansoni and S. haematobium adult worm microsomal antigens are highly specific for both species.89,90 However, positive results in antibody assays do not necessarily correlate with the worm burden, as measured by egg output. Also, it is not possible to distinguish previous exposure from current infections or reinfections.45,91–93 A PCR method has been developed as a highly sensitive and specific technique to detect Schistosoma sp. DNA.94

Medical treatment

Until the late 1970s, fouadin, a trivalent antimony preparation, and potassium antimony tartrate were the only treatments available, and the cure involved suffering more intense than that caused by the disease.44 Metrifonate (Trichlorfon: CASRN: 52-68-6) has been used for the treatment of S. haematobium,15,16,95 but it has some severe human neurological side effects.96

Currently, medical management of bilharziasis relies on praziquantel, sometimes in combination with oxamniquine. Praziquantel (Biltricide®, Bayer AG, Germany) a heterocyclic prazino-isoquinoline, is highly effective against all species of schistosomes pathogenic to humans.97,98 However, since its first use, praziquantel treatment has been noted not to be 100% effective in eliminating S. haematobium infection.99 In adult schistosomes, praziquantel induces vesication, vacuolization, and disintegration of the tegument.100–104 It also causes mature schistosome eggs to hatch.105,106 Immature eggs remain unaffected and continue to develop to maturity.107 In longitudinal studies, bladder wall pathology and hydronephrosis have been found to regress upon treatment, especially in active phases of the infection.24,108,109 However, if chronic stricture of the ureters has occurred, no significant reduction of the renal collecting system may result.110 In such a case, surgical intervention including mechanical dilation, resection, re-implantation, formation of an ileal ureter, and even nephroureterectomy may be required.24

Drug availability

It behooves the medical community to keep the continuing needs for such drugs in their collective consciousness. Not long ago, Bayer Corporation Pharmaceutical Division had decided to withdraw praziquantel from the United States market for lack of sales. A campaign of letters, faxed messages, and telephone calls from members of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, the International Society of Travel Medicine, and the Infectious Disease Society of America served to increase the corporate awareness of the unique role for this drug in the treatment of immigrants, refugees, and returned travelers.111 As a consequence, Bayer reversed its earlier discontinuation decision, and therefore praziquantel was available for treatment of the present case. With the vagaries of the current climate of global drug import, export and reimport, it is difficult to predict, however, whether this will always be the case.112–114

Drug resistance

Another concern with respect to the future of praziquantel treatment is the ever-present worry over the emergence of drug resistance.115 Praziquantel has been in use for almost 25 years, during which time it has been the drug of choice for many human and veterinary parasitic infections worldwide.116–118 The European Commission has established an International Initiative on Praziquantel Use to review reports of low efficacy in clinical trials in Senegal and Egypt, and reports of resistant S. mansoni strains isolated in the laboratory.115,119–129 While investigations suggest that no emergence of praziquantel resistance in S. haematobium has yet occurred, mathematical models predict that such resistance can be expected to occur as soon as 2010.130 As a consequence new drugs are being actively investigated.131,132

Adverse reactions

In healthy, uninfected humans, clinical trials showed no clinically relevant drug-related changes.133,134 However, in humans infected with S. mansoni or S. japonicum, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, diarrhea, and bloody stools have been reported.135–138 These symptoms occur immediately after treatment and are correlated with the intensity of infection, suggesting an anaphylactic response due to parasite and egg antigens released in response to praziquantel.

In S. japonicum-infected mice, intestinal mast cells infiltrate into the intestine. When praziquantel is administered by injection, mature eggs hatch and the mast cells are activated to release histamine and other biogenic amines. This mast cell response plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of post-praziquantel anaphylactic signs. Additionally, antigenic components from the hatched eggs, rather than from adult worms play a major role as allergens in the pathogenesis of adverse effects in praziquantel-treated mice.139

Severe symptoms occur more frequently in patients given high dosages of praziquantel than in those given relatively low, divided dosages.137 Thus, while single doses are more convenient, treatment with two or more praziquantel administrations, each at a low dosage, may reduce antigen release, and has been suggested as a way to minimize the occurrence of severe adverse effects.139

Vaccines

No effective vaccine is yet available against any of the Schistosoma species. However, this may soon change. The Schistosoma Genome Project, created in 1992, has begun to yield comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanism involved in schistosome nutrition and metabolism, host-dependent development and maturation, immune evasion, and invertebrate evolution.2,140 New potential vaccine candidates and drug targets are emerging.141–146

Co-infection

It is also important to be aware that persons infected with S. haematobium can be simultaneously infected with S. mansoni and other geohelminths.50,147–149 Evidence also suggests that the type 2 immunological response (interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-5) induced by S. haematobium may weaken the type 1 response (interferon-γ) making individuals more susceptible to mycobacterial infections.150

Other potential sequelae

Secondary bacterial infection is common in schistosomiasis.151 S. haematobium infections can not only affect the urinary tract, but also other organs of the pelvic floor, especially the reproductive organs, including the prostate and scrotum,44 and the uterus and fallopian tubes, which can lead to infertility.21,152–155 The vulva, vagina, and cervix are affected more commonly than the internal pelvic organs.156 Genital schistosomiasis may increase the risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection.157 S. haematobium can also rarely infect the pericardium, central nervous system, synovium, adrenal gland, thyroid gland and other organs.24,54,158 S. haematobium infection has been associated with squamous cell carcinoma, the only form of bladder cancer with a parasitologic etiology.159–163

Potential threats to public health in the United States The intermediate host for S. haematobium is the aquatic snail Bulinus abyssinicus. Human transmission of S. haematobium to countries where other susceptible bulinid snails occur is of concern.164 B. abyssinicus is not present in the United States. Studies have long been undertaken to determine the potential of snails endemic to the United States to transmit schistosomes, and none have thus far proven capable of serving as a vector.44,165,166 However, it is evident that snail host shifts have played a role in the Schistosoma evolution, so the possibility of an emerging competent schistosome/snail host combination in the United States, while negligible, is present.167

There is a North American schistosome of which one should be aware, however, and that is the bird schistosome (Trichobilharzia ocellata = T. szidati) that causes cercarial dermatitis (swimmer's itch).168–170 This causes initial symptoms very similar to Schistosoma sp. infections when the worm enters the skin. Thus far it is found primarily in the upper Midwest, but has also been found in other regions of the United States.171 The transmission of human zoonoses via migratory birds is a growing concern in this area.172

The related schistosomes, T. franki and T. regent, are now also spreading via bird vectors throughout Europe and are becoming an emerging zoonoses there.173–175 In some cases, it causes fever, respiratory and digestive allergic symptoms. Great concern is being expressed over the possibility of central nervous system involvement as well.176–179 Rodents are being found to be capable intermediate hosts and might be expected to be capable hosts of T. ocellata (T. szidati) in the United States as well.

Another concern is not only the importation of the schistosome from immigrants and travelers, but also the importation of African snails into the country. Recent events have vividly demonstrated that the importation of African plants and animals into this country have caused public health and agricultural concerns in the Midwest, as exemplified by the monkeypox outbreak resulting from the importation of the Giant Gambian Rat in 2003 and giant African snails in 2004.180–182

Helminthic infections, dengue, leishmaniasis, African trypanosomiasis, malaria, diarrheal diseases, and tuberculosis are reemerging in Africa due to inadequate intervention and control strategies.183 All of these need to be considered as potential diseases in African immigrants and travelers.

Another large immigrant population in Wisconsin are the Hmong from Laos.184,185 Nearly 20,000 Hmong immigrated to Wisconsin in the 1970s.186 A schistosome similar to S. japonicum, but endemic to a defined area of the Mekong River in Laos and Cambodia is S. mekongi, and it has been reported among the Hmong.187,188 It is characteristically associated with hepatosplenic disease, but has also been reported to involve the brain.189

CONCLUSION

While the Centers for Disease Control is developing a strategy for better health assessments of refugees from areas rife with endemic parasitic diseases of public health significance, the chronic nature of schistosomiasis makes it difficult to catch and treat all cases.19 This means that all practitioners, but especially those in communities with large and growing immigrant populations, need to increase awareness of these diseases. Bilharziasis, although a common disease, is rarely seen in Wisconsin. The diagnosis is straight forward, if suspected, and effective, safe treatment exists at the present time.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation for providing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript through the services of Graig Eldred, Linda Weis, and Alice Stargardt.

References

- 1.Williams S. Program to aid entrepreneurial political refugees expanding. [June 1, 2004];Milwaukee Journal Sentinal Online. 2002 Sep 29; Available at: http://www.jsonline.com/news/state/sep02/83967.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu W, Brindley PJ, McManus DP, Feng Z, Han ZG. Schistosome transcriptomes: new insights into the parasite and schistosomiasis. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kogulan P, Lucey DR. Schistosomiasis. [May 11, 2004];eMedicine. 2002 Available at: http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic2071.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neafie RC, Marty AM. Unusual infections in humans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:34–56. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chitsulo L, Engels D, Montresor A, Savioli L. The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Acta Trop. 2000;77:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(00)00122-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lengeler C, Utzinger J, Tanner M. Questionnaires for rapid screening of schistosomiasis in sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:235–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiff CJ. The impact of agricultural development on aquatic systems and its effect on the epidemiology of schistosomes in Rhodesia. In: Farver MT, Milton JP, editors. The careless technology - ecology and international development. Garden City, NY: The Natural History Press; 1972. pp. 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Schalie H. World Health Organization Project Egypt 10: A case history of a schistosomiasis control project. In: Farver MT, Milton JP, editors. The careless technology - ecology and international development. Garden City, NY: The Natural History Press; 1972. pp. 116–136. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arfaa F. Studies on schistosomiasis in Somalia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1975;24:280–283. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1975.24.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pincock S. Schistosomiasis initiative extended to five more countries. BMJ. 2003;327:1307. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7427.1307-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan BS, Meyers K. Images in clinical medicine. Schistosoma haematobium. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1085. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010123431505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schistosomiasis investigation in Somalia. Chin Med J (Engl) 1980;93:637–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koura M, Upatham ES, Awad AH, Ahmed MD. Prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium in the Koryole and Merca Districts of the Somali Democratic Republic. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1981;75:53–61. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1981.11687408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upatham ES, Koura M, Ahmed MD, Awad AH. Studies on the transmission of Schistosoma haematobium and the bionomics of Bulinus (Ph.) abyssinicus in the Somali Democratic Republic. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1981;75:63–69. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1981.11687409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aden Abdi Y, Gustafsson LL. Field trial of the efficacy of a simplified and standard metrifonate treatments of Schistosoma haematobium. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;37:371–374. doi: 10.1007/BF00558502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aden Abdi Y, Gustafsson LL. Poor patient compliance reduces the efficacy of metrifonate treatment of Schistosoma haematobium in Somalia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;36:161–164. doi: 10.1007/BF00609189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagi H, Huldt G, Loftenius A, Schroder H. Antibody responses in schistosomiasis haematobium in Somalia. Relation to age and infection intensity. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1990;84:171–179. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1990.11812451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birrie H, Berhe N, Tedla S, Gemeda N. Schistosoma haematobium infection among Ethiopian prisoners of war (1977–1988) returning from Somalia. Ethiop Med J. 1993;31:259–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller JM, Boyd HA, Ostrowski SR, Cookson ST, Parise ME, Gonzaga PS, Addiss DG, Wilson M, Nguyen-Dinh P, Wahlquist SP, Weld LH, Wainwright RB, Gushulak BD, Cetron MS. Malaria, intestinal parasites, and schistosomiasis among Barawan Somali refugees resettling to the United States: a strategy to reduce morbidity and decrease the risk of imported infections. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:115–121. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bock B, Neal PM. Urinary schistosomiasis in Nebraska. Nebr Med J. 1995;80:264–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 1-1994. A 27-year-old woman with secondary infertility and a bladder mass. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:51–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401063300110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 31-2000. A 32-year-old man with a lesion of the urinary bladder. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1105–1111. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010123431508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganem JP, Marroum MC. Schistosomiasis of the urinary bladder in an African immigrant to North Carolina. South Med J. 1998;91:580–583. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199806000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith JH, Christie JD. The pathobiology of Schistosoma haematobium infection in humans. Hum Pathol. 1986;17:333–345. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(86)80456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clements MH, Oko T. Cytologic diagnosis of schistosomiasis in routine urinary specimens. A case report. Acta Cytol. 1983;27:277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Visser LG, Polderman AM, Stuiver PC. Outbreak of schistosomiasis among travelers returning from Mali, West Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:280–285. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jelinek T, Nothdurft HD, Loscher T. Schistosomiasis in travelers and expatriates. J Travel Med. 1996;3:160–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.1996.tb00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newman RD, Schwartz MA. Hematuria in two school-age refugee brothers from Africa. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15:335–337. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199910000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colucci P, Fogazzi GB. The Sudanese immigrant with recurrent gross haematuria—diagnosis at a glance by examination of the urine sediment. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:2247–2249. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.9.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz E, Rozenman J, Perelman M. Pulmonary manifestations of early schistosome infection among nonimmune travelers. Am J Med. 2000;109:718–722. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lischer GH, Sweat D. 16-year-old boy with gross hematuria. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:475–478. doi: 10.4065/77.5.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Youssef AR, Cannon JM, Al Juburi AZ, Cockett AT. Schistosomiasis in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Iraq. Urology. 1998;51((5A Suppl)):170–174. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yacoub A, Southgate BA. The epidemiology of schistosomiasis in the later stages of a control programme based on chemotherapy: the Basrah study. 1. Descriptive epidemiology and parasitological results. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81:449–459. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(87)90165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yacoub A, Southgate BA, Lillywhite JE. The epidemiology of schistosomiasis in the later stages of a control programme based on chemotherapy: the Basrah study. 2. The serological profile and the validity of the ELISA in seroepidemiological studies. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81:460–467. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(87)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Southgate BA, Yacoub A. The epidemiology of schistosomiasis in the later stages of a control programme based on chemotherapy: the Basrah study. 3. Antibody distributions and the use of age catalytic models and log-probit analysis in seroepidemiology. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81:468–475. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(87)90168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Department of State, author. Somalia Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1998. [May 28, 2004];Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, February 26, 1999. Available at: http://www.state.gov/www/global/human_rights/1998_hrp_re port/somalia.html. [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, author. [May 28, 2004];The world fact book - Somalia. 2003 Dec 18; Updated. Available at: http://www.odci.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/so.html.

- 38.Toosi N. Fear tinges hope for Somalis in U.S. In Minnesota enclave, U.S. intervention weighed. [June 1, 2004];Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Online. 2002 Jan 13; Available at: http://www.jsonline.com/news/metro/jan02/12510.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kepler K. Many reach out to help immigrants, migrants. [June 1, 2004];Catholic Herald. Available at: http://www.catholicherald.org/archives/articles/migrantministry.html. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner MJ. Rural Barron leads diversity effort. [June 1, 2004];Wisconsin Public Radio. 2002 Nov 28; Available at: http://www.wpr.org/news/archives/0211.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 41.U.S. Department of State, author. Revised family reunification program for FY 2004. [May 28, 20041];U.S. Refugee Admissions Program News. 2003 1 Available at: http://www.state.gov/g/prm/rls/other/27435.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross AG, Bartley PB, Sleigh AC, Olds GR, Li Y, Williams GM, McManus DP. Schistosomiasis. Engl J Med. 2002;346:1212–1220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zahran MM, Kamel M, Mooro H, Issa A. Bilharziasis of urinary bladder and ureter: comparative histopathologic study. Urology. 1976;8:73–79. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(76)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barlow CH, Meleney HE. A voluntary infection with Schistosoma haematobium. Am J Trop Med. 1949;29:79–87. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1949.s1-29.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Sherbiny MM, Osman AM, Hancock K, Deelder AM, Tsang VC. Application of immunodiagnostic assays: detection of antibodies and circulating antigens in human schistosomiasis and correlation with clinical findings. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:960–966. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.King CH, Muchiri EM, Mungai P, Ouma JH, Kadzo H, Magak P, Koech DK. Randomized comparison of low-dose versus standard-dose praziquantel therapy in treatment of urinary tract morbidity due to Schistosoma haematobium infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:725–730. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stephenson S, Latham MC, Kurz KM, Miller D, Kinoti SN, Oduori ML. Urinary iron loss and physical fitness of Kenyan children with urinary schistosomiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985;34:322–330. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1985.34.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stephenson LS, Latham MC, Kurz KM, Kinoti SN, Oduori ML, Crompton DW. Relationships of Schistosoma hematobium, hookworm and malarial infections and metrifonate treatment to hemoglobin level in Kenyan school children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985;34:519–528. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1985.34.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brouwer KC, Ndhlovu PD, Wagatsuma Y, Munatsi A, Shiff CJ. Epidemiological assessment of Schistosoma haematobium-induced kidney and bladder pathology in rural Zimbabwe. Acta Trop. 2003;85:339–347. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brouwer KC, Ndhlovu PD, Wagatsuma Y, Munatsi A, Shiff CJ. Urinary tract pathology attributed to Schistosoma haematobium: does parasite genetics play a role? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:456–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilkins HA, Goll PH, Marshall TF, Moore PJ. Dynamics of Schistosoma haematobium infection in a Gambian community. III. Acquisition and loss of infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1984;78:227–232. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(84)90283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Behrman AJ. Schistosomiasis. [May 11, 2004];eMedicine. 2002 Jan 28; Available at: http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic857.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warren KS. The relevance of schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:203–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198007243030408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mahmoud AA. Schistosomiasis. Engl J Med. 1977;297:1329–1331. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197712152972405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Christie JD, Crouse D, Smith JH, Pineda J, Ishak EA, Kamel IA. Patterns of Schistosoma haematobium egg distribution in the human lower urinary tract. II. Obstructive uropathy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986;35:752–758. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.El-Nahas AR, Shoma AM, El-Baz M. Bilharzial pyelitis: a rare cause of secondary ureteropelvic junction obstruction. J Urol. 2003;170:1946–1947. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000084161.39457.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beaufils H, Lebon P, Auriol M, Danis M. Glomerular lesions in patients with Schistosoma haematobium infection. Trop Geogr Med. 1978;30:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greenham R, Cameron AH. Schistosoma haematobium and the nephrotic syndrome. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1980;74:609–613. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(80)90150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sobh MA, Moustafa FE, Ramzy RM, Deelder AM, Ghoneim MA. Schistosoma haematobium-induced glomerular disease: an experimental study in the golden hamster. Nephron. 1991;57:216–224. doi: 10.1159/000186254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Obel N, Black FT. Microscopic examination of sperm as the diagnostic clue in a case of Schistosoma haematobium infection. Scand J Infect Dis. 1994;26:117–118. doi: 10.3109/00365549409008602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ghoneim MA. Bilharziasis of the genitourinary tract. BJU Int. 2002;89:22–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.138.138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Houba V. Experimental renal disease due to schistosomiasis. Kidney Int. 1979;16:30–43. doi: 10.1038/ki.1979.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patil KP, Ibrahim AI, Shetty SD, el Tahir MI, Anandan N. Specific investigations in chronic urinary bilharziasis. Urology. 1992;40:117–119. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(92)90507-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elston DM. What's eating you? Schistosoma haematobium. Cutis. 2004;73:233–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weber MD, Blair DM, Clark VV. The pattern of schistosome egg distribution in a micturition flow. Cent Afr J Med. 1967;13:75–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peters PA, Mahmoud AA, Warren KS, Ouma JH, Siongok TK. Field studies of a rapid, accurate means of quantifying Schistosoma haematobium eggs in urine samples. Bull World Health Organ. 1976;54:159–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feldmeier H, Doehring E, Daffalla AA. Simultaneous use of a sensitive filtration technique and reagent strips in urinary schistosomiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1982;76:416–421. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(82)90204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gyorkos TW, Ramsan M, Foum A, Khamis IS. Efficacy of new low-cost filtration device for recovering Schistosoma haematobium eggs from urine. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2681–2682. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2681-2682.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Engels D, Sinzinkayo E, Gryseels B. Day-to-day egg count fluctuation in Schistosoma mansoni infection and its operational implications. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:319–324. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cerri GG, Alves VA, Magalhaes A. Hepatosplenic schistosomiasis mansoni: ultrasound manifestations. Radiology. 1984;153:777–780. doi: 10.1148/radiology.153.3.6387793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Degremont A, Burki A, Burnier E, Schweizer W, Meudt R, Tanner M. Value of ultrasonography in investigating morbidity due to Schistosoma haematobium infection. Lancet. 1985;1:662–665. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.WHO/TDR, author. Ultrasound in schistosomiasis. A practical guide to the standardized use of ultrasonography for the assessment of schistosomiasis-related morbidity; Second International Workshop; October 22–26, 1996; Niamey, Niger. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garba A, Campagne G, Tassie JM, Barkire A, Vera C, Sellin B, Chippaux JP. Long-term impact of a mass treatment by praziquantel on morbidity due to Schistosoma haematobium in two hyperendemic villages of Niger. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2004;97:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reimert CM, Mshinda HM, Hatz CF, Kombe Y, Nkulila T, Poulsen LK, Christensen NO, Vennervald BJ. Quantitative assessment of eosinophiluria in Schistosoma haematobium infections: a new marker of infection and bladder morbidity. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:19–28. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mott KE, Dixon H. Collaborative study on antigens for immunodiagnosis of schistosomiasis. Bull World Health Organ. 1982;60:729–753. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsang VC, Peralta JM, Simons AR. Enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot techniques (EITB) for studying the specificities of antigens and antibodies separated by gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 1983;92:377–391. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)92032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tsang VC, Tsang KR, Hancock K, Kelly MA, Wilson BC, Maddison SE. Schistosoma mansoni adult microsomal antigens, a serologic reagent. I. Systematic fractionation, quantitation, and characterization of antigenic components. J Immunol. 1983;130:1359–1365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mott KE, Dixon H, Carter CE, Garcia E, Ishii A, Matsuda H, Mitchell G, Owhashi M, Tanaka H, Tsang VC. Collaborative study on antigens for immunodiagnosis of Schistosoma japonicum infection. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65:233–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tsang VC, Wilkins PP. Immunodiagnosis of schistosomiasis. Screen with FAST-ELISA and confirm with immunoblot. Clin Lab Med. 1991;11:1029–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhu Y, He W, Liang Y, Xu M, Yu C, Hua W, Chao G. Development of a rapid, simple dipstick dye immunoassay for schistosomiasis diagnosis. J Immunol Methods. 2002;266:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xiang X, Tianping W, Zhigang T. Development of a rapid, sensitive, dye immunoassay for schistosomiasis diagnosis: a colloidal dye immunofiltration assay. J Immunol Methods. 2003;280:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deelder AM, De Jonge N, Boerman OC, Fillie YE, Hilberath GW, Rotmans JP, Gerritse MJ, Schut DW. Sensitive determination of circulating anodic antigen in Schistosoma mansoni infected individuals by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using monoclonal antibodies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:268–272. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.De Jonge N, Fillie YE, Hilberath GW, Krijger FW, Lengeler C, de Savigny DH, van Vliet NG, Deelder AM. Presence of the schistosome circulating anodic antigen (CAA) in urine of patients with Schistosoma mansoni or S. haematobium infections. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;41:563–569. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.41.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.de Jonge N, Kremsner PG, Krijger FW, Schommer G, Fillie YE, Kornelis D, van Zeyl RJ, van Dam GJ, Feldmeier H, Deelder AM. Detection of the schistosome circulating cathodic antigen by enzyme immunoassay using biotinylated monoclonal antibodies. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:815–818. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90094-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.van Etten L, Folman CC, Eggelte TA, Kremsner PG, Deelder AM. Rapid diagnosis of schistosomiasis by antigen detection in urine with a reagent strip. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2404–2406. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2404-2406.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nibbeling HA, Kahama AI, Van Zeyl RJ, Deelder AM. Use of monoclonal antibodies prepared against Schistosoma mansoni hatching fluid antigens for demonstration of Schistosoma haematobium circulating egg antigens in urine. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:543–550. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kahama AI, Odek AE, Kihara RW, Vennervald BJ, Kombe Y, Nkulila T, Hatz CF, Ouma JH, Deelder AM. Urine circulating soluble egg antigen in relation to egg counts, hematuria, and urinary tract pathology before and after treatment in children infected with Schistosoma haematobium in Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:215–219. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Osada Y, Anyan WK, Boamah D, Otchere J, Quartey J, Asigbee JR, Bosompem KM, Kojima S, Ohta N. The antibody responses to adult-worm antigens of Schistosoma haematobium, among infected and resistant individuals from an endemic community in southern Ghana. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003;97:817–826. doi: 10.1179/000349803225002633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Attallah AM, Ismail H, El Masry SA, Rizk H, Handousa A, El Bendary M, Tabll A, Ezzat F. Rapid detection of a Schistosoma mansoni circulating antigen excreted in urine of infected individuals by using a monoclonal antibody. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:354–357. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.354-357.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Van Gool T, Vetter H, Vervoort T, Doenhoff MJ, Wetsteyn J, Overbosch D. Serodiagnosis of imported schistosomiasis by a combination of a commercial indirect hemagglutination test with Schistosoma mansoni adult worm antigens and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with S. mansoni egg antigens. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3432–3447. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3432-3437.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Doenhoff MJ, Dunne DW, Lillywhite JE. Serology of Schistosoma mansoni infections after chemotherapy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:237–238. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90658-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maddison SE. The present status of serodiagnosis and seroepidemiology of schistosomiasis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1987;7:93–105. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(87)90026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Doenhoff MJ, Chiodini PL, Hamilton JV. Specific and sensitive diagnosis of schistosome infection: can it be done with antibodies? Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rabello A, Pontes LA, Dias-Neto E. Recent advances in the diagnosis of Schistosoma infection: the detection of parasite DNA. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:171–172. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000900033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Feldmeier H, Chitsulo L. Therapeutic and operational profiles of metrifonate and praziquantel in Schistosoma haematobium infection. Arzneimittelforschung. 1999;49:557–565. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1300462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.ToxNet, author. Trichorfon. [June 8, 2004];CASRN: 52-68-6. Available at: http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgibin/sis/search/r?dbs+hsdb:@term+@rn+52-68-6.

- 97.Webbe G, James C. A comparison of the susceptibility to praziquantel of Schistosoma haematobium, S. japonicum, S. mansoni, S. intercalatum and S. mattheei in hamsters. Z Parasitenkd. 1977;52:169–177. doi: 10.1007/BF00389901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pearson RD, Guerrant RL. Praziquantel: a major advance in anthelminthic therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:195–198. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-2-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Davis A, Biles JE, Ulrich AM. Initial experiences with praziquantel in the treatment of human infections due to Schistosoma haematobium. Bull World Health Organ. 1979;57:773–779. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Becker B, Mehlhorn H, Andrews P, Thomas H, Eckert J. Light and electron microscopic studies on the effect of praziquantel on Schistosoma mansoni, Dicrocoelium dendriticum, and Fasciola hepatica (Trematoda) in vitro. Z Parasitenkd. 1980;63:113–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00927527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mehlhorn H, Becker B, Andrews P, Thomas H, Frenkel JK. In vivo and in vitro experiments on the effects of praziquantel on Schistosoma mansoni. A light and electron microscopic study. Arzneimittelforschung. 1981;31:544–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shaw MK, Erasmus DA. Schistosoma mansoni: the effects of a subcurative dose of praziquantel on the ultrastructure of worms in vivo. Z Parasitenkd. 1983;69:73–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00934012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shaw MK, Erasmus DA. Schistosoma mansoni: dose-related tegumental surface changes after in vivo treatment with praziquantel. Z Parasitenkd. 1983;69:643–653. doi: 10.1007/BF00926674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Irie Y, Utsunomiya H, Tanaka M, Ohmae H, Nara T, Yasuraoka K. Schistosoma japonicum and S. mansoni: ultrastructural damage in the tegument and reproductive organs after treatment with levo- and dextro-praziquantel. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;41:204–211. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.41.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Matsuda H, Tanaka H, Nogami S, Muto M. Mechanism of action of praziquantel on the eggs of Schistosoma japonicum. Jpn J Exp Med. 1983;53:271–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Giboda M, Smith JM. Schistosoma mansoni eggs as a target for praziquantel: efficacy of oral application in mice. J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;97:98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Richards F, Jr, Sullivan J, Ruiz-Tiben E, Eberhard M, Bishop H. Effect of praziquantel on the eggs of Schistosoma mansoni, with a note on the implications for managing central nervous system schistosomiasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1989;83:465–472. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1989.11812373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Subramanian AK, Mungai P, Ouma JH, Magak P, King CH, Mahmoud AA, King CL. Long-term suppression of adult bladder morbidity and severe hydronephrosis following selective population chemotherapy for Schistosoma haematobium. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:476–481. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wagatsuma Y, Aryeetey ME, Sack DA, Morrow RH, Hatz C, Kojima S. Resolution and resurgence of Schistosoma haematobium-induced pathology after community-based chemotherapy in Ghana, as detected by ultrasound. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1515–1522. doi: 10.1086/314786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Doehring E, Reider F, Schmidt-Ehry G, Ehrich JH. Reduction of pathological findings in urine and bladder lesions in infection with Schistosoma haematobium after treatment with praziquantel. Infect Dis. 1985;152:807–810. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Appleby J. Hospitals, patients run short of key drugs. [June 4, 2004];USA Today. 2001 Jul 11; Available at: http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2001-07-11-drugs-usat.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dickson M. International pharmaceutical expenditure differentials: why? Manag Care. 2004;13:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Barton JH. TRIPS and the global pharmaceutical market. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:146–154. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Reich MR, Govindaraj R, Dumbaugh K, Yang B, Brinkmann A, El-Saharty S. International strategies for tropical disease treatments. Experiences with praziquantel. World Health Organization Publication WHO/DAP/CTD/98.5, 1998. (available at http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/hcpds/books/reich/praziquantel_report.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lawn SD, Lucas SB, Chiodini PL. Case report: Schistosoma mansoni infection: failure of standard treatment with praziquantel in a returned traveler. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97:100–101. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(03)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Drugs for parasitic infections. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1998;40:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.USP Drug Information. I. Rockville MD: United States Pharmacopeial Convention; 1998. Praziquantel; pp. 2395–2397. [Google Scholar]

- 118.King CH, Mahmoud AA. Drugs five years later: praziquantel. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:290–296. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-4-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Guisse F, Polman K, Stelma FF, Mbaye A, Talla I, Niang M, Deelder AM, Ndir O, Gryseels B. Therapeutic evaluation of two different dose regimens of praziquantel in a recent Schistosoma mansoni focus in Northern Senegal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:511–514. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Stelma FF, Sall S, Daff B, Sow S, Niang M, Gryseels B. Oxamniquine cures Schistosoma mansoni infection in a focus in which cure rates with praziquantel are unusually low. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:304–307. doi: 10.1086/517273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stelma FF, Talla I, Sow S, Kongs A, Niang M, Polman K, Deelder AM, Gryseels B. Efficacy and side effects of praziquantel in an epidemic focus of Schistosoma mansoni. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:167–170. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Picquet M, Vercruysse J, Shaw DJ, Diop M, Ly A. Efficacy of praziquantel against Schistosoma mansoni in northern Senegal. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:90–93. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)90971-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bennett JL, Day T, Liang FT, Ismail M, Farghaly A. The development of resistance to anthelmintics: a perspective with an emphasis on the antischistosomal drug praziquantel. Exp Parasitol. 1997;87:260–267. doi: 10.1006/expr.1997.4229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Fallon PG, Mubarak JS, Fookes RE, Niang M, Butterworth AE, Sturrock RF, Doenhoff MJ. Schistosoma mansoni: maturation rate and drug susceptibility of different geographic isolates. Exp Parasitol. 1997;86:29–36. doi: 10.1006/expr.1997.4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pereira C, Fallon PG, Cornette J, Capron A, Doenhoff MJ, Pierce RJ. Alterations in cytochrome-c oxidase expression between praziquantel-resistant and susceptible strains of Schistosoma mansoni. Parasitology. 1998;117:63–73. doi: 10.1017/s003118209800273x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cunha VM, Noel F. (Ca(2+)-Mg2+)ATPase in Schistosoma mansoni: evidence for heterogeneity and resistance to praziquantel. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1998;93:181–182. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761998000700029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Doenhoff MJ, Kusel JR, Coles GC, Cioli D. Resistance of Schistosoma mansoni to praziquantel: is there a problem? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96:465–469. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Cioli D, Pica-Mattoccia L. Praziquantel. Parasitol Res. 2003;90:S3–S9. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0751-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ismail M, Botros S, Metwally A, William S, Farghally A, Tao LF, Day TA, Bennett JL. Resistance to praziquantel: direct evidence from Schistosoma mansoni isolated from Egyptian villagers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:932–935. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.King CH, Muchiri EM, Ouma JH. Evidence against rapid emergence of praziquantel resistance in Schistosoma haematobium, Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:585–594. doi: 10.3201/eid0606.000606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Fenwick A, Savioli L, Engels D, Robert Bergquis N, Todd MH. Drugs for the control of parasitic diseases: current status and development in schistosomiasis. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Guirguis FR. Efficacy of praziquantel and Ro 15-5458, a 9-acridanone-hydrazone derivative, against Schistosoma haematobium. Arzneimittelforschung. 2003;53:57–61. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1297071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Frohberg H, Schulze Schencking M. Toxicological profile of praziquantel, a new drug against cestode and schistosome infections, as compared to some other schistosomicides. Arzneimittelforschung. 1981;31:555–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Frohberg H. Results of toxicological studies on praziquantel. Arzneimittelforschung. 1984;34:1137–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Polderman AM, Gryseels B, Gerold JL, Mpamila K, Manshande JP. Side effects of praziquantel in the treatment of Schistosoma mansoni in Maniema, Zaire. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1984;78:752–754. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(84)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Chen MG, Fu S, Hua XJ, Wu HM. A retrospective survey on side effects of praziquantel among 25,693 cases of schistosomiasis japonica. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1983;14:495–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Nosenas JS, Santos AT, Jr, Blas BL, Tormis LC, Portillo GP, Poliquit OS, Papasin MC, Flores GS. Experiences with praziquantel against Schistosoma japonicum infection in the Philippines. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1984;15:489–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Watt G, Baldovino PC, Castro JT, Fernando MT, Ranoa CP. Bloody diarrhoea after praziquantel therapy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80:345–346. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(86)90053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Matsumoto J. Adverse effects of praziquantel treatment of Schistosoma japonicum infection: involvement of host anaphylactic reactions induced by parasite antigen release. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:461–471. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00368-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Franco GR, Valadao AF, Azevedo V, Rabelo EM. The Schistosoma gene discovery program: state of the art. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:453–463. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(00)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ellis JT, Morrison DA, Reichel MP. Genomics and its impact on parasitology and the potential for development of new parasite control methods. DNA Cell Biol. 2003;22:395–403. doi: 10.1089/104454903767650667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Capron A, Capron M, Riveau G. Vaccine development against schistosomiasis from concepts to clinical trials. Br Med Bull. 2002;62:139–148. doi: 10.1093/bmb/62.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Nascimento E, Leao IC, Pereira VR, Gomes YM, Chikhlikar P, August T, Marques E, Lucena-Silva N. Protective immunity of single and multi-antigen DNA vaccines against schistosomiasis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:105–109. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000900021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Tendler M, Brito CA, Vilar MM, Serra-Freire N, Diogo CM, Almeida MS, Delbem AC, Da Silva JF, Savino W, Garratt RC, Katz N, Simpson AS. A Schistosoma mansoni fatty acid-binding protein, Sm14, is the potential basis of a dual-purpose anti-helminth vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:269–273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Pearce EJ. Progress towards a vaccine for schistosomiasis. Acta Trop. 2003;86:309–313. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(03)00062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Shalaby KA, Yin L, Thakur A, Christen L, Niles EG, LoVerde PT. Protection against Schistosoma mansoni utilizing DNA vaccination with genes encoding Cu/Zn cytosolic superoxide dismutase, signal peptide-containing superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase enzymes. Vaccine. 2003;22:130–136. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Keiser J, N'Goran EK, Traore M, Lohourignon KL, Singer BH, Lengeler C, Tanner M, Utzinger J. Polyparasitism with Schistosoma mansoni, geohelminths, and intestinal protozoa in rural Cote d'Ivoire. J Parasitol. 2002;88:461–466. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2002)088[0461:PWSMGA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Cunin P, Tchuem Tchuente LA, Poste B, Djibrilla K, Martin PM. Interactions between Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni in humans in north Cameroon. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:1110–1117. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-2276.2003.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Utzinger J, Keiser J. Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis: common drugs for treatment and control. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:263–285. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Scott JT, Johnson RC, Aguiar J, Debacker M, Kestens L, Guedenon A, Gryseels B, Portaels F. Schistosoma haematobium infection and Buruli ulcer. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:551–552. doi: 10.3201/eid1003.020514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Bretagne S, Rey JL, Sellin B, Mouchet F, Roussin S. Schistosoma haematobium bilharziosis and urinary infections. Study of their relationship in 2 villages of Niger. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1985;78:79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.El-Mahgoub S. Pelvic schistosomiasis and infertility. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1982;20:201–206. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(82)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Bullough CH. Infertility and bilharziasis of the female genital tract. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1976;83:819–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1976.tb00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Harouny A, Pedersen H. Pelveo-peritoneal schistosomiasis as a cause of primary infertility. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1988;27:467–469. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(88)90132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Poggensee G, Kiwelu I, Saria M, Richter J, Krantz I, Feldmeier H. Schistosomiasis of the lower reproductive tract without egg excretion in urine. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:782–783. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Williams AO. Pathology of schistosomiasis of the uterine cervix due to S. haematobium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;98:784–791. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(67)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Poggensee G, Feldmeier H. Female genital schistosomiasis: facts and hypotheses. Acta Trop. 2001;79:193–210. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(01)00086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Magalhaes-Santos IF, Lemaire DC, Andrade-Filho AS, Queiroz AC, Carvalho OM, Carmo TM, Siqueira IC, Andrade DM, Rego MF, Guedes AP, Reis MG. Antibodies to Schistosoma mansoni in human cerebrospinal fluid. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:294–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Schwartz DA. Helminths in the induction of cancer II. Schistosoma haematobium and bladder cancer. Trop Geogr Med. 1981;33:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Mostafa MH, Sheweita SA, O'Connor PJ. Relationship between schistosomiasis and bladder cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:97–111. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Vizcaino AP, Parkin DM, Boffetta P, Skinner ME. Bladder cancer: epidemiology and risk factors in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Cancer Causes Control. 1994;5:517–522. doi: 10.1007/BF01831379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Thomas JE, Bassett MT, Sigola LB, Taylor P. Relationship between bladder cancer incidence, Schistosoma haematobium infection, and geographical region in Zimbabwe. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:551–553. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90036-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Hodder SL, Mahmoud AA, Sorenson K, Weinert DM, Stein RL, Ouma JH, Koech D, King CH. Predisposition to urinary tract epithelial metaplasia in Schistosoma haematobium infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:133–138. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.63.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Birrie H, Balcha F, Bizuneh A, Bero G. Susceptibility of Ethiopian bulinid snails to Schistosoma haematobium from Somalia. East Afr Med J. 1996;73:76–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Stunkard HW. Possible snail hosts of human schistosomes in the United States. J Parasitol. 1946;32:539–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Lucey DR, Maguire JH. Schistosomiasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1993;7:635–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Loker ES, Morgan JAT, DeJong RJ, Mkoji GM. Snails and schistosomes: some perspectives from molecular phylogenetics. Abstract; American Malacological Society, 69th Annual Meeting; June 25–29, 2003; Ann Arbor, Michigan. [June 10, 2004]. Available at: http://erato.acnatsci.org/ams/meetings/archives/2003/2003_ab s.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 168.Haas W, van de Roemer A. Invasion of the vertebrate skin by cercariae of Trichobilharzia ocellata: penetration processes and stimulating host signals. Parasitol Res. 1998;84:787–795. doi: 10.1007/s004360050489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Graczyk TK, Shiff CJ. Recovery of avian schistosome cercariae from water using penetration stimulant matrix with an unsaturated fatty acid. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:174–177. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.63.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Lockyer AE, Olson PD, Ostergaard P, Rollinson D, Johnston DA, Attwood SW, Southgate VR, Horak P, Snyder SD, Le TH, Agatsuma T, McManus DP, Carmichael AC, Naem S, Littlewood DT. The phylogeny of the Schistosomatidae based on three genes with emphasis on the interrelationships of Schistosoma Weinland, 1858. Parasitology. 2003;126:203–224. doi: 10.1017/s0031182002002792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Loken BR, Spencer CN, Granath WO., Jr Prevalence and transmission of cercariae causing schistosome dermatitis in Flathead Lake, Montana. J Parasitol. 1995;81:646–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Reed KD, Meece JK, Henkel JS, Shukla SK. Birds, migration and emerging zoonoses: West Nile virus, Lyme disease, influenza A and enteropathogens. Clinical Medicine & Research. 2003;1:5–12. doi: 10.3121/cmr.1.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Muller V, Kimmig P, Frank W. The effect of praziquantel on Trichobilharzia (Digenea, Schistosomatidae), a cause of swimmer's dermatitis in humans. Appl Parasitol. 1993;34:187–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Horak P, Kolarova L, Dvorak J. Trichobilharzia regenti n. sp. (Schistosomatidae, Bilharziellinae), a new nasal schistosome from Europe. Parasite. 1998;5:349–357. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1998054349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Bayssade-Dufour Ch, Vuong PN, Rene M, Martin-Loehr C, Martins C. Visceral lesions in mammals and birds exposed to agents of human cercarial dermatitis. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2002;95:229–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Horak P, Dvorak J, Kolarova L, Trefil L. Trichobilharzia regenti, a pathogen of the avian and mammalian central nervous systems. Parasitology. 1999;119:577–581. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099005132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Horak P, Kolarova L. Bird schistosomes: do they die in mammalian skin? Trends Parasitol. 2001;17:66–69. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(00)01770-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Hradkova K, Horak P. Neurotropic behaviour of Trichobilharzia regenti in ducks and mice. J Helminthol. 2002;76:137–141. doi: 10.1079/JOH2002113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Kolarova L, Horak P, Cada F. Histopathology of CNS and nasal infections caused by Trichobilharzia regenti in vertebrates. Parasitol Res. 2001;87:644–650. doi: 10.1007/s004360100431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Reed KD, Melski JW, Graham MB, Regnery RL, Sotir MJ, Wegner MV, Kazmierczak JJ, Stratman EJ, Li Y, Fairley JA, Swain GR, Olson VA, Sargent EK, Kehl SC, Frace MA, Kline R, Foldy SL, Davis JP, Damon IK. The detection of monkeypox in humans in the Western Hemisphere. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:342–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.U.S. Department of Agriculture, author. Pest Alert. Safeguarding, intervention, and trade compliance officers confiscate giant African snails in Wisconsin. 2004 Jan; APHIS 81-35-008. [Google Scholar]

- 182.MSNBC, author. [July 7, 2004];Officials seize giant snails from schools. 2004 Apr 26; Available at: http://msnbc.msn.com/id/4839564/

- 183.Hotez PJ, Remme JH, Buss P, Alleyne G, Morel C, Breman JG. Combating tropical infectious diseases: report of the Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries Project. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:871–888. doi: 10.1086/382077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Beck R. The ordeal of immigration in Wausau. [June 11, 2004];The Atlantic Monthly. 1994 Apr; Available at: http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/immigrat/beckf.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 185.Barrett B, Shadick K, Schilling R, Spencer L, del Rosario S, Moua K, Vang M. Hmong/medicine interactions: improving cross-cultural health care. Fam Med. 1998;30:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Inui M. Assimilation and repatriation conflicts of the Hmong refugees in a Wisconsin community: a qualitative study of five local groups. Migration World Magazine. 1998;26:26–28. [Google Scholar]

- 187.Westermeyer J. Schistosomiasis in Hmong people. JAMA. 1978;240:2152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Ohmae H, Sinuon M, Kirinoki M, Matsumoto J, Chigusa Y, Socheat D, Matsuda H. Schistosomiasis mekongi: from discovery to control. Parasitol Int. 2004;53:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Houston S, Kowalewska-Grochowska K, Naik S, McKean J, Johnson ES, Warren K. First report of Schistosoma mekongi infection with brain involvement. in Infect Dis. 2004;38:e1–e6. doi: 10.1086/379826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]