Significance

Symmetry-breaking charge separation (SB-CS) is of particular interest in solar energy conversion because photodriven charge separation occurs with minimal loss of the photon energy. While previous research has identified pairs of molecules that undergo SB-CS, as well as characterized their intrinsic properties and the environmental factors that affect the process, little effort has focused on how to transfer the photogenerated charges to adjacent molecules to store or utilize the energy. Here, we have synthesized and studied a molecular system that demonstrates photoinduced SB-CS, followed by migration of both the electron and the hole to different secondary charge acceptors resulting in long-lived charge separation. This strategy has the potential to increase the efficiency of molecular systems for artificial photosynthesis and photovoltaics.

Keywords: artificial photosynthesis, radical ion pair, symmetry-breaking charge transfer, perylenediimide

Abstract

Understanding how to utilize symmetry-breaking charge separation (SB-CS) offers a path toward increasingly efficient light-harvesting technologies. This process plays a central role in the first step of photosynthesis, in which the dimeric “special pair” of the photosynthetic reaction center enters a coherent SB-CS state after photoexcitation. Previous research on SB-CS in both biological and synthetic chromophore dimers has focused on increasing the efficiency of light-driven processes. In a chromophore dimer undergoing SB-CS, the energy of the radical ion pair product is nearly isoenergetic with that of the lowest excited singlet (S1) state of the dimer. This means that very little energy is lost from the absorbed photon. In principle, the relatively high energy electron and hole generated by SB-CS within the chromophore dimer can each be transferred to adjacent charge acceptors to extend the lifetime of the electron–hole pair, which can increase the efficiency of solar energy conversion. To investigate this possibility, we have designed a bis-perylenediimide cyclophane (mPDI2) covalently linked to a secondary electron donor, peri-xanthenoxanthene (PXX) and a secondary electron acceptor, partially fluorinated naphthalenediimide (FNDI). Upon selective photoexcitation of mPDI2, transient absorption spectroscopy shows that mPDI2 undergoes SB-CS, followed by two secondary charge transfer reactions to generate a PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•− radical ion pair having a nearly 3 µs lifetime. This strategy has the potential to increase the efficiency of molecular systems for artificial photosynthesis and photovoltaics.

Photoinduced symmetry-breaking charge separation (SB-CS) plays a central role in many light-harvesting strategies, with perhaps the most well-known example being bacterial photosynthesis (1). In the photosynthetic reaction center protein complex, light-driven SB-CS occurs in the bacteriochlorophyll dimer known as the “special pair.” This charge transfer state initiates a sequence of energetically downhill electron transfer events that each further stabilize the radical ion pair as the distance between the charges increases (2, 3). The quantum yield of electron transfer is near unity because the initial charge transfer events are very fast, occurring from ~10−12 s to 10−10 s, compared to the ~10−9 s bacteriochlorophyll-excited singlet-state (S1) lifetime (1, 4). All photosynthetic reaction centers, from both plants and bacteria, follow a similar photoinitiated multistep electron transfer strategy that uses sunlight to generate energetic, long-lived radical ion pairs (5–7). The stored energy in these radical ion pairs drives subsequent slower redox chemistry that is essential to biochemical pathways (8, 9).

Being able to preserve more of the photon energy by eliminating the free energy losses incurred by multiple electron transfer steps down a redox gradient would be highly advantageous for both artificial photosynthesis and molecular photovoltaics (10–12). In most electron donor–acceptor systems, the free energy change between the S1 state of the donor or acceptor and the charge-separated (CS) state is at least −0.3 eV to ensure rapid electron transfer. However, if SB-CS occurs, the energies of S1 and the SB-CS state are comparable, resulting in an energy loss upon population of the CS state that is often 0.1 eV or less (13, 14). Incorporating materials that undergo SB-CS into a photovoltaic device has been demonstrated to markedly enhance its open-circuit voltage by increasing the charge transfer rate between the donor and acceptor layers (15). A key challenge for utilizing SB-CS to enhance solar energy conversion is finding ways to further separate and stabilize the charges produced by SB-CS by transferring them to adjacent molecules before charge recombination of the SB-CS state occurs. This is difficult because the two chromophores that interact to create the SB-CS state are strongly coupled electronically. Kinetically outcompeting charge recombination of the SB-CS state requires a delicate balance of free energy changes and electronic coupling as prescribed by electron transfer theory (16).

Some of the most well-documented SB-CS compounds are the 9,9′-bianthryl derivatives that use this strategy (17, 18), which generally have optical absorption bands in the near ultraviolet spectrum. However, the scope of SB-CS chromophores has now expanded to include many compounds that can absorb visible light, such as cyanine derivatives (19, 20), dipyridyl molecules (21), and (bis)-dipyrrin complexes (22, 23). More recently, innovative structures have demonstrated SB-CS using different chromophore dimer conformations (24), such as cofacial dimers (25, 26), cyclophanes (27–30), slip-stacked dimers (31), and supramolecular aggregates (32, 33). In particular, rylene diimides have proven to be useful in many such structures as a result of their photochemical stability, high extinction coefficients in the visible and near-infrared spectrum, and ease of synthetic modification (34). The large arene cores of rylenes make them especially effective in applications that require significant cofacial π–π interactions between chromophores. Perylene-(3,4:9,10)-bis(dicarboximide) (perylenediimide, PDI) in particular has been shown to undergo SB-CS from a variety of inter-chromophore geometries, in both polar and nonpolar media (31, 35–38) as well as in the solid state (39).

Research in the field of SB-CS has thus far focused largely on characterizing this process, and as yet no system has demonstrated subsequent charge transfer of both the hole and electron away from the chromophore dimer to a secondary donor and acceptor. In this work, we describe the preparation and characterization of a cyclophane in which two PDIs are linked using two meta-bis(aminomethyl)benzenes (mPDI2). The mPDI2 cyclophane is asymmetrically substituted with a peri-xanthenoxanthene (PXX) electron donor and a partially fluorinated naphthalene-(1,4:5,8)-bis (dicarboximide) (FNDI) electron acceptor to give PXX-mPDI2-NDI (1). The PXX donor was used because it is about 0.5 eV easier to oxidize than the PDI within mPDI2 and the resulting radical cation, PXX•+, has a distinctive optical absorption near 900 nm (40). Similarly, FNDI was chosen as the acceptor because it is about 0.3 eV easier to reduce than the PDI within mPDI2 and the resulting radical anion, FNDI•−, has a sharp electronic absorption at 480 nm (41). Because of these radical ion spectral features, transient absorption spectroscopy readily shows that selective photoexcitation of mPDI2 results in SB-CS within the cyclophane followed by ultrafast oxidation of PXX and reduction of FNDI to give the PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•− radical ion pair. Symmetrically substituted model compounds PXX-mPDI2-PXX (2) and FNDI-mPDI2-FNDI (3) (Fig. 1) were used to determine the electron transfer rates from PXX to the SB-CS state of mPDI2 and from that state to FNDI, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Molecular structures of substituted PDI cyclophanes 1–3.

Results

Steady-State Spectra.

The steady-state absorption spectra for 1–3 are found in Fig. 2. The mPDI2 cyclophane exhibits maxima at 443 nm, 536 nm, and 572 nm, with a molar extinction coefficient ε = 44,900 M−1cm−1 at 572 nm. The strong electronic coupling between the H-aggregated PDIs in mPDI2 leads to enhancement of the 536 nm band compared to that in monomeric PDI (35). In compound 2, the more intense PXX absorption bands at 420 nm and 448 nm overlap with the 443 nm PDI band. Less-intense PXX bands at 328 nm and 396 nm can also be seen. In the spectrum of compound 3, the FNDI absorption bands are evident at 339 nm, 357 nm, and 376 nm. All of these bands, with the exception of the obscured 443 nm PDI band, appear in the spectrum of 1, with contributions from PXX and FNDI appearing at half the intensity seen in 2 and 3, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Steady-state UV-vis spectra for 1–3 in CH2Cl2.

Energetics.

The S1 energy of mPDI2 determined from the energy average of its optical absorption and emission spectra is 2.10 eV, while the energy of the mPDI2 SB-CS state relative to its ground state, determined previously using equilibrium kinetics (35), is ΔGSB-CS = 2.03 eV in CH2Cl2. Given that the electron transfer measurements for charge transfer from the mPDI2 SB-CS state separation to PXX and FNDI in 1–3 are carried out in the moderately polar solvent CH2Cl2, and the distances over which the charges are transferred are long relative to the size of the ions, solvent, and coulombic corrections to estimating the energies of the ionic intermediates are negligible (42), so that the ion-pair energies can be estimated using the sums of the relevant one-electron redox potentials.

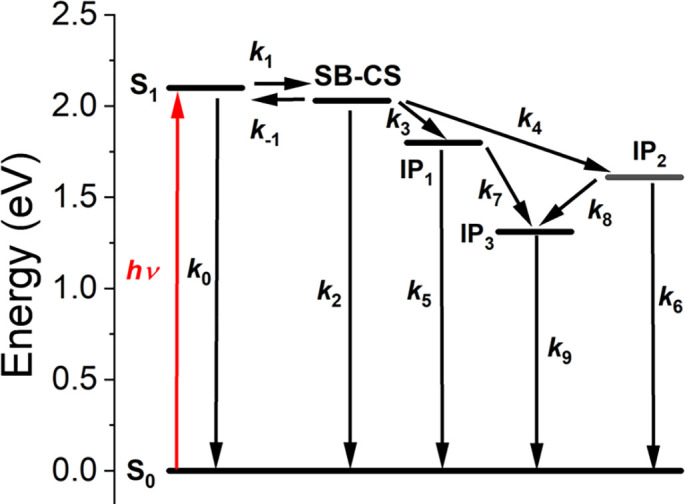

As reported previously, mPDI2 undergoes one-electron oxidation at 1.30 V vs. the saturated calomel electrode (SCE) and reduction at −0.81 V vs. SCE (35). Cyclic voltammetry was used to determine the one-electron redox potentials of the PXX donor and FNDI acceptor in CH2Cl2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), where PXX is oxidized at 0.80 V vs. SCE (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) and FNDI is reduced at −0.50 V vs. SCE (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Thus, the energy of FNDI-mPDI2•+-FNDI•− is ΔGIP1 = 1.80 eV and that of PXX•+-mPDI2•−-PXX is ΔGIP2 = 1.61 eV, while the energy of the fully charge-separated system PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•− is ΔGIP3 = 1.30 eV. The energetic parameters for 1–3 are summarized in SI Appendix, Table S1 and the energies of the relevant electronic states are given in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Kinetic scheme of the electron transfer pathways for 1. IP1 = PXX-mPDI2•+-FNDI•−, IP2 = PXX•+-mPDI2•−-FNDI, and IP3 = PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•−.

Transient Absorption (TA) Spectroscopy.

The kinetics of SB-CS and the subsequent electron transfers to the appended PXX donor and FNDI acceptor in 1–3 were investigated using TA spectroscopy (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S7). Transient spectra at selected times are given in Fig. 4 A, C, and E, while the species-associated spectra obtained by using the kinetic model depicted in Fig. 3 and global analysis of the data are given in Fig. 4 B, D, and F. The rate constants for the charge transfer reactions are given in SI Appendix, Table S2 and the details of the kinetic analysis are given in SI Appendix. All mPDI2 cyclophanes exhibit an instrument-limited ground state bleach (GSB) at 500 to 600 nm followed by the appearance of new absorption bands at 620 nm and 788 nm, assigned to the formation of PDI•+ and PDI•−, respectively (35). In compound 2 (Fig. 4 C and D), the decay of the 620 nm PDI•+ absorption band is accompanied by two GSBs at 419 nm and 445 nm corresponding to the loss of PXX. The 525 and 935 nm PXX•+ absorptions (40) are obscured by the PDI GSB and the formation of PDI•−, respectively. However, the appearance of the PXX GSBs coupled with the disappearance of the PDI•+ band indicate that hole transfer from the SB- CS state to PXX occurs giving PXX•+-mPDI2•−-PXX. In compound 3 (Fig. 4 E and F), the decay of the PDI•− SB-CS band at 788 nm results in the appearance of new FNDI GSBs at 356 nm and 375 nm. The characteristic absorption band of FNDI•− appears at 480 nm (41), even though, as in 2, much of the transient absorption from FNDI•− is obscured by the large PDI GSB. These spectral changes show that electron transfer from the SB-CS state to FNDI gives FNDI-mPDI2•+-FNDI•−.

Fig. 4.

TA spectra and their species-associated spectra for 1 (A, B), 2 (C, D), and 3 (E, F).The mPDI2 cyclophane was selectively photoexcited using a 570 nm, 100 fs laser pulse. All spectra were collected in CH2Cl2 at 295 K. IP1 = PXX-mPDI2•+-FNDI•−, IP2 = PXX•+-mPDI2•−-FNDI, and IP3 = PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•−.

In compound 1 (Fig. 4 A and B), the transient absorption features at 525 and 935 nm characteristic PXX•+ (40) and those at 480 and 600 nm indicative of FNDI•− (41) as well as the GSBs of PXX and FNDI are visible. The enhanced spectral resolution for 1 derives from the fact that the mPDI2 cyclophane ground state is fully regenerated upon formation of the PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•− radical ion pair, thus eliminating the large PDI GSB observed in 2 and 3. For clarity, only the S1, SB-CS, and PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•− (IP3) states are shown in Fig. 4B. The species-associated spectra of the intermediate species PXX-mPDI2•+-FNDI•− and PXX•+-mPDI2•−-FNDI in 1 are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S5; these spectra are very similar to those of PXX•+-mPDI2•−-PXX and FNDI-mPDI2•+-FNDI•− in 2 and 3, respectively. Since these ion pairs have comparable lifetimes, the presence of all four radical ions results in complex spectra. Formation of the terminal PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•− radical ion pair is accompanied by a very small yield of PDI triplet formed upon charge recombination that is ignored in this analysis.

Discussion

The secondary PXX electron donor and FNDI acceptor were chosen in this study for three main reasons. First, they have redox potentials that result in negative free energies for transferring the charges from both PDI radical ions constituting the SB-CS state of mPDI2. Second, both PXX and FNDI have absorbance maxima that do not interfere with photoexcitation of PDI. Third, the optical spectra of PXX•+ and FNDI•− have large extinction coefficients at distinct wavelengths that make them readily detectable by TA spectroscopy. The TA spectra and much longer lifetime of the PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•− state in compound 1 show that the charges generated by SB-CS can readily be transferred to adjacent donors and acceptors. Compared to the center-to-center radical ion pair distances of 20.0 and 14.2 Å in model compounds 2 and 3, the PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•− radical ion pair distance in 1 is 33.8 Å, which significantly reduces the electronic coupling matrix element for the charge recombination reaction and leads to its long lifetime (16).

The kinetic model used to describe the charge transfer dynamics of 1 is depicted in Fig. 3. Upon photoexcitation of the mPDI2 cyclophane, the S1 state and SB-CS state enter an equilibrium (k1 and k-1) due to their nearly degenerate energy levels. From this equilibrium, both S1 and the SB-CS state can relax to the ground state S0 with k0 and k2, respectively, while the SB-CS state can transfer an electron to FNDI with k3 and accept an electron from PXX with k4. In the case of reference molecules 2 and 3, PXX•+-mPDI2•−-PXX (IP1) and FNDI-mPDI2•+-FNDI•− (IP2) decay to their ground states with k5 and k6, respectively, while in 1 these radical ion pairs undergo further competitive charge separation to yield PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•− (IP3) with k7 and k8, respectively, followed by charge recombination to S0 and a minor PDI triplet component with k9.

Time-resolved fluorescence (TRF) studies of 1–3 (SI Appendix, Figs. S8–S11) show biexponential fluorescence decays that confirm the presence of the equilibrium between the S1 and SB-CS states of the mPDI2 cyclophane as observed and modeled previously (35). Fitting the TRF data for 1 to this model confirms a single emissive species (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). The rate constants obtained previously for mPDI2 without PXX and FNDI attached [k1 = (23.5 ps)−1, k−1 = (443 ps)−1, and k2 = (7.36 ns)−1] are used in modeling the electron transfer dynamics of 1–3 using the scheme shown in Fig. 3. Following SB-CS, the formation rate of PXX•+-mPDI2•−-PXX in 2 is k4 = (1.33 ns)−1, while the decay of this radical ion pair is k6 = (1.04 ns)−1. Because there are two degenerate hole acceptors in 2, the extracted charge separation rate was divided by two to obtain the intrinsic rate constant. A similar statistical situation pertains to the formation rate of FNDI-mPDI2•+-FNDI•− in 3, where k3 = (491 ps)−1, which then decays with k5 = (686 ps)−1.

Electron transfer theory predicts that the reaction rate depends on both the free energy change and the electronic coupling matrix element between the two reactants (16). The free energy change for production of FNDI-mPDI2•+-FNDI•− in 3 is smaller than that for the formation of PXX•+-mPDI2•−-PXX in 2; however, PXX and mPDI2 are linked via an intervening xylyl group that decreases their electronic coupling, while mPDI2 is linked to FNDI directly. Thus, the faster rate of FNDI reduction in 3 (k3) compared to PXX oxidation in 2 (k4) is likely caused by the increased electronic coupling in 3 overcoming the small advantage in free energy change in 2.

In compound 1, the total, model-derived charge separation rate constant from the SB-CS state is k3 + k4 = (323 ps)−1, which is similar to the sum of the charge separation constants from 2 and 3: (358 ps)-1. This is consistent with the idea that in 1, charge transfer to both PXX and FNDI occurs simultaneously and nearly independent of one another, with the electron transfer pathway to FNDI kinetically favored. After the first charge transfer disrupts the equilibrium between S1 and the SB-CS state of mPDI2, the formation of PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•− occurs with k7 = (1.00 ± 0.02 ns)−1 and k8 = (1.36 ± 0.11 ns)−1, which results in a total formation rate of k7 + k8 = (576 ± 130 ps)−1. The terminal radical ion pair then decays primarily to S0 along with a very minor amount of PDI triplet in k9 = (2.87 μs)−1. This triplet decays with a rate of k ~(100 µs)−1 in deaerated solution.

The quantum yields of charge separation were determined from the transient spectra obtained at times for which the species of interest is at its maximum concentration and at wavelengths for which there is minimal overlap of the transient absorptions of the species. Using the extinction coefficients of both the ground states and the radical ions, the GSBs are used as internal standards and the quantum yields are calculated using the ratio method outlined in SI Appendix. The observed quantum yields of PXX•+-mPDI2•−-PXX in 2 and FNDI-mPDI2•+-FNDI•− in 3 are 0.56 ± 0.07 and 0.64 ± 0.06, respectively, while that of PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•− in 1 is 0.37 ± 0.07.

Conclusions

While neither charge in PXX•+-mPDI2-FNDI•− moves very far from its point of origin in the mPDI2 SB-CS state, the combined migration distances significantly reduce the electronic coupling between the two radical ions constituting the pair leading to a nearly 3 μs lifetime and a 0.37 quantum yield of formation. There is, of course, room to improve the ion pair lifetime by extending the chain of electron transfers or finding other ways to inhibit charge recombination. Further optimization of the free energy changes for the secondary electron transfers will increase both the yield and energy of the terminal ion pair state, making such a design suitable for energy-demanding photochemical processes. Nonetheless, this study demonstrates the potential of SB-CS to drive secondary charge separation reactions using modest free energy changes to generate long-lived radical ion pairs that preserve a significant fraction of the photon energy.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis.

A dibrominated PDI cyclophane was synthesized via stepwise cyclization of 1,6,7,12-tetrakis(4-t-butylphenoxy)perylene-(3,4:9,10)tetracarboxydianhydride (43, 44) and 5-bromo-1,3-bis(aminomethyl)benzene (45), which were prepared as previously reported. The PXX boronic ester was prepared as described previously (40), and the FNDI boronic ester was prepared from the FNDI precursor (46) using an iridium-catalyzed direct core borylation (47). Compounds 1–4 were synthesized by Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling of the corresponding boronic esters with the dibromo-PDI cyclophane. Synthetic procedures and molecular characterization details are described in SI Appendix.

Electrochemistry.

The reduction potentials of the PXX and FNDI chromophores were determined on a CH Instruments 660A electrochemical workstation using a 2 mM solution of analyte with 100 mM tetra-n-butylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6) as the supporting electrolyte. Measurements were made using a 1.0-mm diameter glassy carbon working electrode, a platinum wire auxiliary electrode, and a silver wire reference in CH2Cl2 continuously purged with argon. The ferrocene/ferrocenium couple was used as an internal standard, and potentials are reported vs. SCE.

Steady-State Spectra.

UV-vis-NIR (λ = 250 to 1,100 nm) steady-state absorption spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu UV-1800 spectrometer. Steady-state emission spectra were collected on a Horiba Nanolog fluorometer set to a right-angle detection mode. All measurements were performed in CH2Cl2 at 295 K.

Transient Absorption Spectroscopy.

Femtosecond transient absorption (fsTA) and nanosecond transient absorption (nsTA) experiments were conducted in CH2Cl2 using a commercial Ti:sapphire laser system (Tsunami oscillator/Spitfire amplifier, Spectra-Physics) as described previously (48). The 570 nm pump pulses were generated using a laboratory-constructed collinear optical parametric amplifier and attenuated to 1 μJ/pulse. Pump pulses underwent randomized polarization (DPU-25-A, Thorlabs Inc.) to suppress the contribution of orientational dynamics. TA spectra were detected using a customized Helios/EOS spectrometer and Helios software (Ultrafast Systems, LLC). The optical density of each sample was 0.4 to 0.6 at 590 nm in a 2-mm cuvette. Samples were sparged with nitrogen for 15 min prior to measurements. The spectroscopic datasets were corrected for group delay dispersion and scattered light using Surface Xplorer (Ultrafast Systems, LLC) prior to kinetic analysis. The kinetic analysis was performed using MATLAB as described previously (28).

Time-Resolved Fluorescence Spectroscopy.

Picosecond time-resolved fluorescence data were collected using a commercial direct-diode-pumped 100 kHz amplifier (Spirit 1040-HE, Spectra Physics), producing a fundamental beam of 1,040 nm (350 fs, 12 W) which was attenuated and used to pump a noncollinear optical parametric amplifier (Spirit-NOPA, Spectra Physics) capable of delivering tunable, high-repetition-rate pulses with pulse durations as short as sub-20 fs. The samples were excited with 570 nm, ~1 nJ laser pulses. Fluorescence was detected using a Hamamatsu C4780 Streakscope as described previously (49). Samples with an optical density of ~0.1 at the excitation wavelength were prepared in 2 mm quartz cuvettes. All data were acquired in single-photon-counting mode using the Hamamatsu HPD-TA software. The temporal resolution, given by the instrument response function, was approximately 3% of the sweep window, with the shortest time resolution being ~30 ps. The data were fit globally using a sequential three-state model and also separately using the equilibrium model discussed in the text.

Computational Details.

Molecular structure calculations were performed using Avogadro 1.2.0 with the MMFF94 force field (50).

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Award DE-FG02-99ER14999. This work made use of the Integrated Molecular Structure Education and Research Center at Northwestern University, which has received support from the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental Resource (NSF ECCS-1542205), the State of Illinois, and the International Institute for Nanotechnology.

Author contributions

M.R.W. designed research; J.M.B., A.F.C., P.J.B., Y.H., and R.M.Y. performed research; J.M.B., P.J.B., R.M.Y., and M.R.W. analyzed data; and J.M.B., R.M.Y., and M.R.W. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

J.K.M. is a co-author with M.R.W. and 14 other co-authors of a review article on an unrelated subject [Nat. Rev. Chem. 4, 490–504 (2020)].

Footnotes

Reviewers: D.K., Yonsei University; and J.K.M., Michigan State University.

Contributor Information

Ryan M. Young, Email: ryan.young@northwestern.edu.

Michael R. Wasielewski, Email: m-wasielewski@northwestern.edu.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are found in SI Appendix. Additional information is available from https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.wpzgmsbtz (51) and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Blankenship R. E., Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis (John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romero E., et al. , Quantum coherence in photosynthesis for efficient solar-energy conversion. Nat. Phys. 10, 676–682 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savikhin S., Jankowiak R., “Mechanism of primary charge separation in photosynthetic reaction centers” in The Biophysics of Photosynthesis, Golbeck J., van der Est A., Eds. (Springer, New York, NY, 2014), pp. 193–240. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saer R. G., Blankenship R. E., Light harvesting in phototrophic bacteria: Structure and function. Biochem. J. 474, 2107–2131 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zinth W., Wachtveitl J., The first picoseconds in bacterial photosynthesis—ultrafast electron transfer for the efficient conversion of light energy. ChemPhysChem 6, 871–880 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klauss A., Haumann M., Dau H., Alternating electron and proton transfer steps in photosynthetic water oxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16035–16040 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lubitz W., Chrysina M., Cox N., Water oxidation in photosystem II. Photosynth. Res. 142, 105–125 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang M., Damjanović A., Vaswani H. M., Fleming G. R., Energy transfer in photosystem I of cyanobacteria synechococcus elongatus: Model study with structure-based semi-empirical hamiltonian and experimental spectral density. Biophys. J. 85, 140–158 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marais A., Sinayskiy I., Petruccione F., van Grondelle R., A quantum protective mechanism in photosynthesis. Sci. Rep. 5, 8720 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amoruso G., et al. , High-efficiency excitation energy transfer in biohybrid quantum dot–bacterial reaction center nanoconjugates. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 5448–5455 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ennist N. M., Stayrook S. E., Dutton P. L., Moser C. C., Rational design of photosynthetic reaction center protein maquettes. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 997295 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sebastian E., Hariharan M., Symmetry-breaking charge separation in molecular constructs for efficient light energy conversion. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 696–711 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rettig W., Charge separation in excited states of decoupled systems—tict compounds and implications regarding the development of new laser dyes and the primary process of vision and photosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 25, 971–988 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young R. M., Wasielewski M. R., Mixed electronic states in molecular dimers: Connecting singlet fission, excimer formation, and symmetry-breaking charge transfer. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1957–1968 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartynski A. N., et al. , Symmetry-breaking charge transfer in a zinc chlorodipyrrin acceptor for high open circuit voltage organic photovoltaics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 5397–5405 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcus R. A., Sutin N., Electron transfers in chemistry and biology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 811, 265–322 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grozema F. C., et al. , QM/MM study of the role of the solvent in the formation of the charge separated excited state in 9,9‘-bianthryl. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 11019–11028 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asami N., et al. , Two different charge transfer states of photoexcited 9,9′-bianthryl in polar and nonpolar solvents characterized by nanosecond time-resolved near-IR spectroscopy in the 4500–10 500 cm-1 region. J. Phys. Chem. A 114, 6351–6355 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whited M. T., et al. , Symmetry-breaking intramolecular charge transfer in excited state of meso-linked bodipy dyads. Chem. Commun. 48, 284–286 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy P., Bressan G., Gretton J., Cammidge A. N., Meech S. R., Ultrafast excimer formation and solvent controlled symmetry breaking charge separation in the excitonically coupled subphthalocyanine dimer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 10568–10572 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golden J. H., et al. , Symmetry-breaking charge transfer in boron dipyridylmethene (dipyr) dimers. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 1, 1083–1095 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trinh C., et al. , Symmetry-breaking charge transfer of visible light absorbing systems: Zinc dipyrrins. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 21834–21845 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sazanovich I. V., et al. , Structural control of the excited-state dynamics of bis(dipyrrinato)zinc complexes: Self-assembling chromophores for light-harvesting architectures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 2664–2665 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vauthey E., Photoinduced symmetry-breaking charge separation. ChemPhysChem 13, 2001–2011 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markovic V., Villamaina D., Barabanov I., Lawson Daku L. M., Vauthey E., Photoinduced symmetry-breaking charge separation: The direction of the charge transfer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7596–7598 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aster A., et al. , Tuning symmetry breaking charge separation in perylene bichromophores by conformational control. Chem. Sci. 10, 10629–10639 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y., et al. , Ultrafast photoinduced symmetry-breaking charge separation and electron sharing in perylenediimide molecular triangles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 13236–13239 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spenst P., Young R. M., Wasielewski M. R., Würthner F., Guest and solvent modulated photo-driven charge separation and triplet generation in a perylene bisimide cyclophane. Chem. Sci. 7, 5428–5434 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schultz J. D., et al. , Steric interactions impact vibronic and vibrational coherences in perylenediimide cyclophanes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 7498–7504 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim W., et al. , Solvent-modulated charge-transfer resonance enhancement in the excimer state of a bay-substituted perylene bisimide cyclophane. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 1919–1927 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin C., Kim T., Schultz J. D., Young R. M., Wasielewski M. R., Accelerating symmetry-breaking charge separation in a perylenediimide trimer through a vibronically coherent dimer intermediate. Nat. Chem. 14, 786–793 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Powers-Riggs N. E., Zuo X., Young R. M., Wasielewski M. R., Symmetry-breaking charge separation in a nanoscale terrylenediimide guanine-quadruplex assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 17512–17516 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim W., et al. , Tracking structural evolution during symmetry-breaking charge separation in quadrupolar perylene bisimide with time-resolved impulsive stimulated raman spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 8571–8578 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Würthner F., et al. , Perylene bisimide dye assemblies as archetype functional supramolecular materials. Chem. Rev. 116, 962–1052 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coleman A. F., et al. , Reversible symmetry-breaking charge separation in a series of perylenediimide cyclophanes. J. Phys. Chem. C 124, 10408–10419 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alzola J. M., et al. , Symmetry-breaking charge separation in phenylene-bridged perylenediimide dimers. J. Phys. Chem. A 125, 7633–7643 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang K., et al. , Achieving symmetry-breaking charge separation in perylenediimide trimers: The effect of bridge resonance. J. Phys. Chem. B 126, 3758–3767 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim T., Lin C., Schultz J. D., Young R. M., Wasielewski M. R., π-Stacking-dependent vibronic couplings drive excited-state dynamics in perylenediimide assemblies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 11386–11396 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramirez C. E., et al. , Symmetry-breaking charge separation in the solid state: Tetra(phenoxy)perylenediimide polycrystalline films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 18243–18250 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christensen J. A., Zhang J., Zhou J., Nelson J. N., Wasielewski M. R., Near-infrared excitation of the peri-xanthenoxanthene radical cation drives energy-demanding hole transfer reactions. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 23364–23370 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gosztola D., Niemczyk M. P., Svec W., Lukas A. S., Wasielewski M. R., Excited doublet states of electrochemically generated aromatic imide and diimide radical anions. J. Phys. Chem. A 104, 6545–6551 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weller A., Photoinduced electron transfer in solution: Exciplex and radical ion pair formation free enthalpies and their solvent dependence. Z. Phys. Chem. 133, 93–99 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y., et al. , Highly soluble perylene tetracarboxylic diimides and tetrathiafulvalene–perylene tetracarboxylic diimide–tetrathiafulvalene triads. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chemistry 200, 334–345 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Würthner F., Thalacker C., Sautter A., Hierarchical organization of functional perylene chromophores to mesoscopic superstructures by hydrogen bonding and π–π interactions. Adv. Mater. 11, 754–758 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacNevin C. J., Pitner J. B., Chen C.-Y., “Narrow emission dyes, compositions comprising same, and methods for making and using same.” WO2020236828 A1 W. I. P. Organization (Nirvana Sciences Inc.) (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan Z., et al. , Core-fluorinated naphthalene diimides: Synthesis, characterization, and application in n-type organic field-effect transistors. Org. Lett. 18, 456–459 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lyall C. L., Shotton C. C., Pérez-Salvia M., Pantoş G. D., Lewis S. E., Direct core functionalisation of naphthalenediimides by iridium catalysed C-H borylation. Chem. Commun. 50, 13837–13840 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Young R. M., et al. , Ultrafast conformational dynamics of electron transfer in exbox4+⊂perylene. J. Phys. Chem. A 117, 12438–12448 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen M., et al. , Singlet fission in covalent terrylenediimide dimers: Probing the nature of the multiexciton state using femtosecond mid-infrared spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9184–9192 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hanwell M. D., et al. , Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform. 4, 17 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bradley J. M., et al. , Time-resolved spectroscopic data for pnas.231357512. Dryad. 10.5061/dryad.wpzgmsbtz. Deposited 7 November 2023. [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are found in SI Appendix. Additional information is available from https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.wpzgmsbtz (51) and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.