Significance

The repertoire of T cell receptors (TCRs) is determined during early T cell development in the thymus; however, it is not well understood whether the repertoire of effector T cells in mouse models of autoimmunity is the same or different from the repertoire in healthy mice, and the tissue of repertoire selection. Our study shows that antigen-presenting cells in the periphery of lupus mice have an altered capacity to process antigen and activate T follicular helper cells (Tfh) generating a Tfh TCR repertoire with greater clonal diversity and leading to enhanced risk of autoantibody production. This study demonstrates the importance of APCs in maintaining peripheral tolerance and suggests they may be an important therapeutic target in SLE.

Keywords: T cell tolerance, repertoire, peripheral tolerance, dendritic cells, SLE

Abstract

Many autoimmune diseases are characterized by the activation of autoreactive T cells. The T cell repertoire is established in the thymus; it remains uncertain whether the presence of disease-associated autoreactive T cells reflects abnormal T cell selection in the thymus or aberrant T cell activation in the periphery. Here, we describe T cell selection, activation, and T cell repertoire diversity in female mice deficient for B lymphocyte–induced maturation protein (BLIMP)-1 in dendritic cells (DCs) (Prdm1 CKO). These mice exhibit a lupus-like phenotype with an expanded population of T follicular helper (Tfh) cells having a more diverse T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire than wild-type mice and, in turn, develop a lupus-like pathology. To understand the origin of the aberrant Tfh population, we analyzed the TCR repertoire of thymocytes and naive CD4 T cells from Prdm1 CKO mice. We show that early development and selection of T cells in the thymus are not affected. Importantly, however, we observed increased TCR signal strength and increased proliferation of naive T cells cultured in vitro with antigen and BLIMP1-deficient DCs compared to control DCs. Moreover, there was increased diversity in the TCR repertoire in naive CD4+ T cells stimulated in vitro with BLIMP1-deficient DCs. Collectively, our data indicate that lowering the threshold for peripheral T cell activation without altering thymic selection and naive T cell TCR repertoire leads to an expanded repertoire of antigen-activated T cells and impairs peripheral T cell tolerance.

Studies in mouse models have shown that both central and peripheral mechanisms shape self-tolerance. The generation of the T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire during thymocyte development is critical for producing a diverse T cell population that is equipped to cope with infectious agents throughout life. While the diversity of the TCR repertoire is important for affording protection against pathogens, the process of TCR formation inevitably generates a certain number of T cells that recognize self-antigens, many of which are negatively selected in the thymus (reviewed in ref. 1) as well as in the periphery (2). Medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) play a key role in negative selection in the thymus. There are two subgroups of mTECs, mTEChi and mTEClo, which are identified by their relative expression of MHCII/CD80 and the autoimmune regulator (Aire). A subset of mTEChi cells exhibit high expression of Aire that results in expression of numerous tissue-specific antigens (TSAs), whose presentation drives both deletion of autoreactive T cells and the agonistic selection of self-reactive regulatory T cells (3–8). Mechanisms to remove these autoreactive T cells have been identified, and dysfunction of these mechanisms has been shown to lead to severe autoimmune disease in mice and in humans (3, 9, 10).

A PRDM1 mutation reducing the expression of B lymphocyte–induced maturation protein-1 (BLIMP1) in dendritic cells (DCs) is a risk factor for SLE (11). We have shown that deletion of BLIMP1 in DCs in mice (Prdm1 CKO mice) leads to a spontaneous lupus-like phenotype in female but not in male mice (12). Along with an expansion of splenic T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, the TCR repertoire of Tfh cells from female Prdm1 CKO mice is distinct from, and more diverse than, the repertoire of Tfh from female control mice (13). The difference in the TCR repertoire of Tfh cells can reflect either a difference in thymic selection of naive CD4+ T or altered activation by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the periphery.

Here, we report that neither the early development of T cells in the thymus nor the TCR repertoire in CD4 single positive (SP) thymocytes is affected in Prdm1 CKO mice. Furthermore, naive CD4+ T cells in the periphery in Prdm1 CKO mice do not exhibit an altered TCR repertoire. However, antigen presentation by BLIMP1-deficient DCs resulted in enhanced TCR signaling and increased T cell proliferation in naive CD4+ T cells resulting in a more polyclonal response with increased TCR diversity following in vitro stimulation. These data suggest that ablation of BLIMP1 in DCs does not alter thymic selection but instead influences naive T cell activation and affects TCR diversity after activation in the periphery. Our data highlight the importance of BLIMP1 in DCs in shaping peripheral tolerance.

Results

Characterization of Thymic DCs in Prdm1 CKO Mice.

While DCs represent a minor population of thymic cells, they have an important, nonredundant role in thymocyte selection (14–16). We, therefore, characterized DCs in the thymus in female Prdm1 CKO mice. DCs were identified as CD11chi MHCIIhi and were further classified as migratory cDC2s (SIRPα+CD8loCD11b+) or resident cDC1s (SIRPα-CD8+CD11b−) (17). DCs were isolated from the CD64- population to exclude thymic macrophages. The percentage of each subset was comparable between control and Prdm1 CKO mice (Fig. 1A). Prdm1 expression was significantly lower in thymic DCs from Prdm1 CKO mice. The expression level of Ctss, encoding CTSS which has a key role in antigen processing in DCs, was higher in thymic DCs from Prdm1 CKO mice compared to control mice, as we previously observed for splenic DCs (13). There was comparable expression of interferon regulatory factor 4 (Irf4) and cathepsin l (Ctsl) in thymic DCs of control and Prdm1 CKO mice; these molecules are also involved in antigen processing but are not direct targets of BLIMP1. We next measured the expression of the autoimmune regulator (Aire), which is a critical transcription factor during thymic selection and highly expressed in mTEChi cells. Expression of Aire was low in thymic DCs from either strain, and no difference was detected between strains (Fig. 1B). MHCII expression was similar, but IL-6 and IL-1β mRNA and protein secretion was increased following stimulation with LPS in BLIMP1-deficient thymic DCs compared to control DCs (Fig. 1 C and D), which is consistent with our previous observations (12).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of thymic DCs in Prdm1 CKO mice. (A) The thymus was isolated from 6- to 8-wk-old female control or Prdm1 CKO mice. DCs (FVD-CD45+CD64-CD11chiMHCIIhi) and DC subsets, migratory DCs (SIRP1αhiCD8α−), and resident DCs (SIRP1α-CD8α+) were identified. The percentage of total DCs and their subsets were quantified and plotted. (B) DCs were isolated from the thymus, and gene expression was measured by qPCR. Relative expression was calculated by normalization to the level of the housekeeping gene, Polr2a. The bar represents the mean. Each dot represents an individual mouse (n = 3). (C) Thymic DCs were isolated from control and Prdm1 CKO female mice and cultured ± LPS (1 µg/mL) overnight. Expression of cytokines was measured by qPCR, and the relative expression was calculated by normalization to the housekeeping gene, Polr2a. Cytokines in the supernatant was measured by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Each dot represents an individual mouse, and the bar represents the mean (n = 4). (D) MHCII expression in thymic DCs was measured by flow cytometry, and the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of MHCII was plotted. The open circle indicates control mice, and the closed circle indicates Prdm1 CKO mice. The bar represents the mean, and each dot represents an individual mouse (n = 3).

Because it has been shown that a BLIMP1-expressing subset of mTEChi cells exists and that the loss of BLIMP1 expression in the mTEChi population leads to autoimmunity in mice (18), we asked whether the knockout of Prdm1 by CD11c-CRE is DC-specific or whether it occurs in mTEChi cells as well. mTEChi cells were identified by the expression of epithelial cellular adhesion molecule 1 (EpCAM1)/CD86/MHCII and Ly51lo (Fig. 2A). The loss of BLIMP1 expression in Prdm1 CKO mice is controlled by CD11c-CRE. We did not detect CD11c expression in mTEChi cells (Fig. 2B) and consistent with this observation, there was no difference in Blimp1 expression in mTEChi cells of control and Prdm1 CKO mice as expected (Fig. 2C). We also measured Aire expression in mTEChi cells, and no difference was detected between control and Prdm1 CKO mice (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Thymic mTEChi cells express an equal amount of antigen presentation machinery in Prdm1 CKO mice. (A) A representative flow image of the sorting strategy of mTEChi (SSChi CD45-PECAM1hiLy51-MHCIIhiCD86hi) or mTEClo (SSChi CD45-EpCAM1hiLy51-MHCIIloCD86lo) thymic stromal cells. (B) A representative flow image of CD11c expression in mTEChi and thymic DCs. (C) Expression of Prdm1, Aire, and Ctss in purified mTEChi cells was measured by qPCR. A relative expression of Prdm1 and Aire was calculated by normalization to the level of the housekeeping gene, Polr2a. The bar represents the mean, and each dot represents an individual mouse (n = 4).

Normal Development of T Cells in the Thymus of Prdm1 CKO Mice.

First, we assessed thymic T cell subsets in Prdm1 CKO mice. There were no significant changes in the percent of double-negative (DN; CD4−CD8−), double-positive (DP; CD4+CD8+), SP CD4+ T and CD8+ thymocytes between control and Prdm1 CKO female mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). We compared the early development of DN thymocytes and observed no alterations (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). We also investigated the maturation of thymocytes and found comparable frequencies in the thymocytes expressing the maturation markers, CD69 and CD24, between Prdm1 CKO and control female mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C).

Natural regulatory T cells (nTreg) are differentiated from CD4+ SP thymocytes after antigenic stimulation, and DCs can induce nTreg differentiation in the thymus (19). We, therefore, assessed the frequency of total FOXP3+ nTregs and their subsets (PD1+/GITRhi Treg and PD1+/GITRlo Treg). No difference was found between control and Prdm1 CKO female mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Collectively, these data suggest that the early development of T cells including CD4+ nTregs in the thymus is not affected in Prdm1 CKO mice.

Repertoires of CD4 SP Thymic T and Splenic Naive CD4+ T Cells Are Not Altered in Prdm1 CKO Mice.

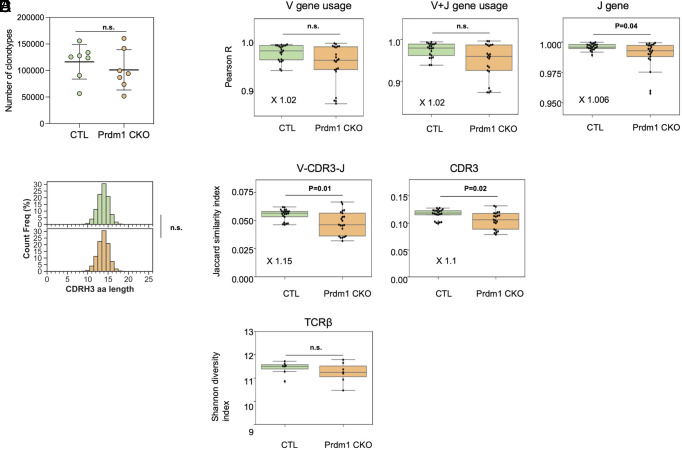

To address the potential role of BLIMP1-deficient DCs in shaping the TCR repertoire of CD4+ SP thymocytes emigrating to the periphery, we performed high-throughput TCR sequencing to determine TCRβ repertoire diversity of CD4 SP thymocytes. TCRβ clonotypes were identified by clustering the sequencing reads based on the same Vβ and Jβ gene usages, as well as the identical complementarity-determining region 3 (CDRβ3). We obtained similar numbers of TCR clonotypes in 6- to 8-wk-old control (116,275 ± 32,575, n = 7) and Prdm1 CKO female mice (101,098 ± 37,909, n = 7) (P = 0.52, Mann-Whitney U test; Fig. 3A). Lengths of CDR3 were the same in control (13.80 ± 0.028) and Prdm1 CKO female mice (13.80 ± 0.039) (Fig. 3B). No differences in the Pearson correlation coefficients for V gene usage or for J gene usage were detected, and only a very slight difference (3%) in the V + J gene usage was observed (Fig. 3C). At the amino acid level, we observed a very slight increase in the similarity between the TCRβ (V + CDR3+J, Fig. 3D) sequences among control mice relative to Prdm1 CKO female mice, and a comparable effect was observed when we examined the similarity of CDR3 repertoires. Most importantly, there was no difference in the Shannon diversity index of the TCRβ repertoire between control and Prdm1 CKO female mice, indicating that the clonal diversity of the TCRβ repertoire in CD4 SP thymic emigrants is not affected by the loss of BLIMP1 in thymic DCs (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Repertoire analysis of CD4+ SP thymocytes. CD4 SP thymocytes were isolated from 6- to 8-wk-old control (n = 7) or Prdm1 CKO female mice (n = 7). TCRβ amplicons of thymocytes in control and Prdm1 CKO mice were sequenced and analyzed by bioinformatic tools described in the Materials and Methods. (A) The number of TCRβ clonotypes sequenced in the TCRβ repertoires was compared between control mice and Prdm1 CKO mice. (B) CDR3β amino acid (aa) lengths of each clonotype were calculated for each mouse, and the cumulative CDR3β length counts were plotted in the upper and bottom histograms for control (n = 6) mice and Prdm1 CKO mice (n = 6), respectively. The sum area under the histogram is equal to 100 for both panels. For statistical significance, the parametric unpaired t test was used. (C) Vβ, Vβ+ Jβ, and Jβ gene usages of thymocytes were compared between control and Prdm1 CKO mice. Each dot represents a Pearson correlation coefficient which measures the degrees to which Vβ, Jβ, or Vβ + Jβ gene usages are associated between the two sets of mice. TCRβ repertoire (D) similarity and (E) diversity were compared between control and Prdm1 CKO mice, as calculated by the Jaccard similarity index and Shannon diversity index, respectively. The Jaccard index was computed twice for i) the sharing of identical CDR3β and ii) the sharing of identical Vβ +CDR3β +Jβ. The whole Vβ +CDR3β +Jβ sequences were considered when it comes to the measurement of the Shannon diversity index.

We next investigated the repertoire of peripheral naive CD4+ T cells (CD44-CD62Lhi) in the spleen. Similarly, we detected a comparable number of clonotypes from 8-wk-old control (150,697 ± 40,092; n = 5) and Prdm1 CKO female mice (167,252 ± 19,929; n = 4, P = 0.54, Mann–Whitney U test; See SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Furthermore, we found no significant differences in the usage of V, J, or V + J genes nor in the clonotypic diversity of the TCR repertoire (i.e., Shannon diversity index; See SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B–D).

To confirm the lack of difference in the TCR repertoire of the thymocytes and naive T cell populations by using a functional approach, congenic CD45.1 control mice were sublethally irradiated to generate a lymphopenic environment. Naive CD4+ T cells from the spleen and CD4 SP thymocytes were isolated from age-matched (6- to 8-wk-old) female control and Prdm1 CKO mice and labeled with tracers, CellTrace violet and CellTrace Far Red, respectively. Equal numbers of splenic naive CD4+ T cells and CD4 SP thymocytes were transferred into each recipient, and proliferation of transferred cells was measured 5 d later. There was no difference in total number of splenocytes, CD4+ T cells and number of transferred CD4+ T cells (CD45.2+) in the recipient mice (Fig. 4A). While we found both splenic naive CD4+ T cells and thymocytes in the spleens of recipient mice, fewer thymocytes were detected compared to naive CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4A). There was strong proliferation in both thymocytes and splenic naive CD4+ T cells (> 95% are CellTrace low), but no significant difference was observed in the frequency of thymocytes or naive T cells derived from control or Prdm1 CKO mice (Fig. 4 B and C). These in vivo data confirm the lack of difference in autoreactivity in the TCR repertoire of the two strains.

Fig. 4.

In vivo proliferative responses of naive T cells and thymocytes in a lymphopenic host. (A) Number of splenocytes, total CD4+ T cells, donor T cells of recipient mice after 5-d adoptive transfer of T cells from control or Prdm1 CKO mice, (B) Representative flow images of total CD4+ T cells, transferred T cells, and CellTrace profiles of donor T cells with gating strategy. (B) Profile of total CD4+ T cells and transferred CD4+ T cells. (C) Cell proliferation was analyzed by calculation of the expansion index (for splenic naive CD4+ T cells; on the left) or MFI (for CD4 SP thymocytes; on the right). Each dot represents an individual mouse, and the bar represents the mean (n = 3).

Naive CD4+ T Cells but Not Thymocytes Exhibit a Differential Response to BLIMP1-Deficient DCs.

T cell activation is determined by TCR signal strength and the cytokine milieu (reviewed in ref. 20). We hypothesized that alterations in antigen presentation by BLIMP1-deficient DCs could affect TCR signaling in naive CD4+ T cells. To test this hypothesis, we compared the TCR signaling strength following antigen encounter in vitro, by monitoring the expression of nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1 (NR4A1) (also termed Nur77). Nur77 serves as a TCR signaling reporter. It does not respond to inflammatory stimuli, in contrast to widely used, conventional activation markers, such as CD69 or NFAT, which are known to be induced not only by TCR engagement but also by cytokines (21). With the Nur77-green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter system, an increase in fluorescence in Nur77-GFP expressing T cells is positively correlated with the strength of TCR signaling (22). To assess cognate-antigen dependent T cell activation, we used T cells from OTII transgenic mice.

We first assessed TCR signaling in thymocytes. CD4 SP thymocytes were isolated from control OTII Nur77-GFP mice and cocultured with thymic DCs from control or Prdm1 CKO female mice. There was a small induction of Nur77 expression by thymic DCs, but no difference in percentage of Nur77hi thymocytes or MFI of Nur77 was detected when DCs were obtained from Prdm1 CKO or control mice (Fig. 5A). We repeated the experiment with splenic DCs, and again, thymocytes responded little to TCR stimulation; BLIMP1 expression in splenic DCs did not affect the frequency of activated T cells (Fig. 5B). We also measured Nur77 induction in thymocytes in vivo. There was an increase in Nur77-positivity in CD4 or CD8 SP thymocytes compared to DP or DN thymocytes, but no difference in the percentage of Nur77-positive thymocytes was observed between control and Prdm1 CKO mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). We also compared Nur77 expression in Tregs and CD44+ activated CD4 SP thymocytes, and again, no difference was observed between strains (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Both BLIMP1-deficient and control DCs induced similar activation of CD4 SP thymocytes, consistent with the similar CD4 SP thymocyte and naive CD4+ T cell repertoire in both mouse strains.

Fig. 5.

Increased induction of Nur77-positive activated T cells from splenic naive CD4+ T cells but not thymocytes by stimulation with BLIMP1-deficient DCs in vitro. DCs were isolated from the thymus (for A) or from the spleen (for B) of control mice (designated as C in the graph) or Prdm1 CKO mice (designated as K in the graph) and cultured with OVA protein for 6 h before the cu-culture with T cells. CD4 SP thymocytes were isolated from OTII Nur77-GFP mice and cultured with the OVA-presenting DCs. Nur77 induction was measured in live T cells by flow cytometry, and the percentage of Nur77-GFP-positive and MFI of the Nur77-positive T cells was analyzed. Baseline of Nur77 was decided by the level of Nur77 of T alone without the DC condition (blue line). Each dot represents an individual mouse, and the bar represents the mean (n = 3). For C and D, DCs were isolated from the spleen (for C) or thymus (for D) of control or Prdm1 CKO female mice and cultured with OVA protein for 6 h before the coculture with T cells. Naive CD4+ T cells were isolated from OTII Nur77-GFP mice and added to the OVA-treated DCs. Nur77 induction was measured in live T cells by flow cytometry, and the percentage of Nur77-positive and the MFI of the Nur77-positive T cells was analyzed and plotted. The baseline level of Nur77 was determined based on the level of Nur77 of T alone without DC stimulation (blue line). Each dot represents an individual mouse, and the bar represents the mean (n = 4).

We next assessed the activation of naive CD4+ T cells in OTII Nur77-GFP mice. When isolated DCs were pulsed with OVA protein and incubated with naive CD4+ T cells isolated from spleens of OTII Nur77-GFP mice, there was a significantly increased frequency of Nur77-GFP-positive T cells relative to stimulation with control DCs (Fig. 5C). We then repeated the in vitro T cell activation experiment with OTII Nur77-GFP splenic naive T cells cocultured with thymic control DCs or thymic BLIMP1–deficient DCs. Splenic CD4+ T cells incubated with thymic BLIMP1–deficient DCs and stimulated with OVA protein showed a significantly increased frequency of Nur77-positive T cells compared to T cells incubated with control thymic DCs and stimulated under identical conditions (Fig. 5D). Thus, BLIMP1-deficient DCs from both spleen and thymus can induce stronger activation of splenic naive CD4+ T cells, whereas the absence of BLIMP1 in DCs does not affect the stimulation of thymocytes.

CTSS Activity Is Required for Increased T Cell Activation by BLIMP1-Deficient DCs in the Periphery.

Increased TCR signaling in naive CD4+ T cells might reflect enhanced TCR engagement by peptide-MHCII on BLIMP1-deficient DCs. The pool of antigenic peptides presented on MHCII in BLIMP1-deficient DCs is enhanced by increased expression of CTSS whose transcription is repressed by BLIMP1 (13). Therefore, we examined whether increased CTSS activity affects T cell activation. Splenic DCs were treated with either a CTSS inhibitor or with vehicle and then cultured with naive CD4+ T cells. Interestingly, there was a diminished fraction of T cells expressing Nur77-GFP in cultures with CTSS inhibitor–treated BLIMP1-deficient DCs (~40%, P = 0.01), leading to TCR activation that was comparable to the level observed with control DCs (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the reduction in the expression of Nur77 was minimal in CTSS inhibitor–treated control DCs (less than 10% reduction compared to untreated DCs) (Fig. 6B). We also measured MHCII expression on DCs. As reported previously (13), BLIMP1-deficient DCs express a twofold higher level of MHCII compared to control DCs; this difference was not affected by CTSS inhibition (Fig. 6C). Of note, there was no alteration in the expression costimulatory molecules between BLIMP1-deficient and control DCs or in BLIMP1-deficient DCs after exposure to a CTSS inhibitor (12).

Fig. 6.

Increased CTSS activity in BLIMP-deficient DCs is required for the enhanced TCR signaling in naive CD4+ T cells. (A) DCs were isolated from spleens of control mice or Prdm1 CKO mice and cultured with OVA protein for 6 h with or without a CTSS inhibitor (1 nM). Naive CD4+ T cells were isolated from OTII Nur77 GFP mice and added to the OVA-treated DCs for 4 h, and the Nur77-GFP induction was measured by flow cytometry. Baseline of Nur77 was decided by the level of Nur77 of T alone without the DC condition (blue line). (B) Percent of inhibition of Nur77 induction by CTSS-inhibitor treatment was calculated. (C) Purified DCs from control mice or Prdm1 CKO mice were cultured for 6 h with or without CTSS-inhibitor (1 nM), and MHCII expression on DCs was measured by flow cytometry. Each dot represents an individual mouse, and the bar represents the mean (n = 3).

BLIMP1-Deficient DCs Induce Increased Proliferation and Activation of Naive CD4+ T Cells Even at Low Doses of Antigen.

We next examined the effect of BLIMP1-deficient and control DCs on the proliferation of in vitro activated naive CD4+ T cells in C57BL/6 mice. After coculture, the frequency of activated T cells and their proliferation status were assessed. Stimulation of T cells with anti-CD3/28 was used as a technical positive control, and there was strong activation, as expected. We could identify ~1% Nur77-GFP+ CD4+ T cells in cultures of T cells alone; 5.5% Nur77-GFP+ T cells in cultures with control splenic DCs and 8.3% in cultures with BLIMP1-deficient splenic DCs (Fig. 7A). BLIMP1-deficient DCs induced stronger naive CD4+ T cell proliferation than control DCs (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Naive T cells stimulated with BLIMP1-deficient DCs exhibit increased T cell proliferation and activation, resulting in higher TCR clonality and differential gene expression. (A–D) DCs were prepared from spleens of control or Prdm1 CKO female mice and splenic naive CD4+ T cells were isolated from B6.Nur77-GFP mice (for A and C) or OTII.Nur77-GFP mice (for B and D). After 2 d of coculture under Tfh differentiation condition, Nur77hi T cells were identified, and proliferating T cells were quantified from live Nur77-GFP+ T cells as indicated in the flow image (for A and B). Different doses of OVA proteins were added to DC culture as indicated in the figure. After the culture, cell trace violet dilution was measured in Nur77-GFP+ CD4+ T cells (for C) or in total CD4+ OTII T cells (for D). Unstimulated control was made with T cells with no DCs. Each dot represents an individual mouse, and the bar indicates the mean, and the line indicates SEM (n = 5). (E–G) Naive CD4+ T cells were isolated from B6.Nur77-GFP mice and were cocultured with OVA protein ingested control or BLIMP1-deficient DCs for 2 d under Tfh differentiation condition. Nur77+ T cells were isolated after the culture and proceed to scRNA-seq. (E) Comparison of the number of TCR clonotypes detected in T cells following stimulation with control or BLIMP1-deficient DCs. TCR clonotypes were identified by clustering the TCR reads using a hamming distance threshold of ≤0.05 in the CDRβ3 amino acid sequences. (F) The Shannon diversity index of paired TCRα:β repertoires was computed for each replicate. The mean ± SD is shown in (E) and (F), and each dot represents n = 4 replicates for each DC group. (G) The volcano plot highlights the DEGs upregulated in T cells stimulated with BLIMP1-deficient DCs relative to control DCs. The fold change in the X axis represents the ratio of the expression level of a given gene in KO DC-stimulated T cells to control DC-stimulated cells. The fold change values are presented on a log2 scale. The Y axis displays the negative log10 of the adjusted P-value calculated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test followed by Bonferroni correction. The orange dot represents the genes that pass the following threshold: |log2 fold change| > 0.1, and −(log10 adj P value) > 20.

We hypothesized that ablation of BLIMP1 could potentially lower the threshold for activation of naive CD4+ T cells, thereby recruiting T cells with an expanded repertoire of TCRs. Increased responsiveness to antigen is consistent with our earlier findings showing an increased diversity of the TCR repertoire in Tfh cells isolated from Prdm1 CKO female mice compared to control mice (13). To investigate the impact of Blimp1 deficiency on the activation threshold of T cells, we pulsed varying concentrations of OVA antigens to control or Blimp1-deficient DCs and then cocultured the OVA-pulsed DCs with naive CD4+ T cells under Tfh differentiation conditions (12). Interestingly, BLIMP1-deficient DCs induced robust proliferation of Nur77+ T cells in response to both high (10 µg OVA) and low (1 µg OVA) antigen doses, whereas control DCs exhibited a threefold reduction in proliferation of T cells exposed to a low dose of antigen dose (Fig. 7C). We further validated these results using naive CD4+ T cells isolated from OTII mice that constitutively express OVA-reactive TCRs. Our results confirmed that OTII T cells stimulated with control DCs did not proliferate at a low dose of antigen, and even with a high antigen dose, their proliferation was fourfold lower than that of OTII T cells stimulated with BLIMP1-deficient DCs (Fig. 7D). Of note, BLIMP1-deficient DCs robustly induced proliferation of OTII T cells at both antigenic doses. Collectively, these data indicate the capability of Blimp1-deficient DCs to activate peripheral T cells at antigen concentrations lower than those required for activation by control DCs.

Impact of BLIMP1 Deficiency in DCs on TCR Clonality and Transcriptomic Profiles of CD4+ Naive T Cells under Tfh Differentiation Condition.

We next compared the paired TCRα:β repertoire and the transcriptomic profiles of T cells stimulated with BLIMP1-deficient and control DCs. To skew splenic naive CD4+ T cells to Tfh differentiation, cells were stimulated with DCs with a cocktail containing IL-6 and IL-21 plus anti-IFNγ, anti-IL-4, and anti-TGFβ antibodies that is known to polarize T cells toward a Tfh-like transcriptional profile (12). After 2 d of coculture, each replicate sample was multiplexed, and live CD4+ T cells were isolated. Following single-cell TCR amplicon sequencing, TCRα:β clonotypes were defined by clustering the TCR reads using a Hamming distance threshold of ≤0.05 within the CDRβ3 nucleotide sequences. The analysis of the paired TCRα:β repertoires revealed that stimulation with BLIMP1-deficient DCs resulted in a significantly higher number of TCR clonotypes (673 ± 44) compared to stimulation with control DCs (584 ± 41) (Fig. 7E). The small number of TCR α:β clonotypes obtained in this experiment restricts the ability to discern physiologically relevant differences in repertoire diversity between the two groups (23); nonetheless, we did note that the Shannon diversity was increased in cells stimulated with BLIMP1-deficient DCs compared to control DCs, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 7F).

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis identified 6,500 T cells and 7,219 T cells from the control DC- and BLIMP1-deficient DC-stimulated controls, respectively, with an average of 1,765 ± 522 genes per cell (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A–C). Analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) revealed a set of upregulated DEGs in T cells stimulated with DCs lacking BLIMP1 relative to those stimulated with control DCs (Fig. 7G and SI Appendix, Fig. S5D). Several upregulated DEGs are involved in TCR signaling, including Jun, Junb, Zfp36, Nfkbia, Dusp1, Gadd45g (24), and Ltb (25). For instance, c-Jun, a major component of the AP-1 dimeric transcription factor, was significantly upregulated in T cells stimulated with BLIMP1-deficient DCs compared to control DCs (adjusted P-value, 4.5E−80). The increase of Jun transcription was accompanied by upregulation of Dusp1, consistent with the established role of DUSP1 activity in dephosphorylating the c-Jun N-terminal kinase required for the activation of c-Jun (adjusted P-value, 1.5E−31). In summary, our data suggest that lack of BLIMP1 in DCs lowers the threshold for activation of peripheral T cells, resulting in increased TCR clonality and subtle but statistically significant changes in the differential expression of genes involved in TCR signaling.

Discussion

The early development of T cells in the thymus determines the TCR repertoire available to cope with a diverse and unpredictable array of pathogens while avoiding autoreactivity. This process encompasses multiple stages of maturation including positive selection of T cells expressing functional TCRs (1) and negative selection of self-reactive T cells (4, 16). Recognition of self-antigenic peptide-MHC complexes is a key determinant for both positive and negative selection. Failure or alteration of negative selection of autoreactive T cells or lack of proper generation of the Treg compartment can result in autoimmune diseases. The mTEChi cells are specialized antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the thymus which express a broad spectrum of extra-thymic tissue antigens due to the transcriptional regulators, AIRE and forebrain embryonic zinc finger-like protein 2 (FEZF2). AIRE and FEZF2 regulate distinct sets of TSAs which enables mTEChi cells to present a broader range of self-antigens (26). Roberts and colleagues found that BLIMP1 is expressed in a subset of mTEChi cells and that the absence of BLIMP1 expression in mTEChi cells leads to autoantibody production in mice (18), suggesting a critical role of BLIMP1 in mTEChi cells for self-tolerance. We found that mTEChi cells do not express CD11c which is the driver of CRE in Prdm1 CKO mice, and, therefore, as expected, in our experiments, there was no difference in BLIMP1 expression in mTEChi cells between control and Prdm1 CKO mice, excluding the involvement of mTEChi cells in our mouse model.

Thymic DCs have been shown to participate in presenting TSAs to developing T cells by several mechanisms. DCs may directly present TSAs as a result of expression of Aire (27, 28), but this is controversial due to the low expression of Aire in these cells. We also detected a low level of Aire in thymic DCs, and an equivalent level of Aire transcript was present in control and BLIMP1-deficient thymic DCs. Thymic XCR1+ resident DCs phagocytose cell debris and cross-present TSAs (29, 30). We did not find a difference in numbers of either resident DCs or migratory DCs between control and Prdm1 CKO female mice. However, the level of Ctss was higher in BLIMP1-deficient thymic DCs. It is possible that this causes BLIMP1-deficient thymic DCs to present a different pool of antigenic peptides, which might exert a differential effect on TCR repertoire without impacting the overall TCR diversity of mature CD4 thymocytes.

The number and development of thymocytes (for both total T cells and Tregs) did not differ between Prdm1 CKO and control mice. Although there was a significant but small difference in V gene usage and CDR3 in CD4 SP thymocytes (Fig. 3 B and C), the overall diversity of thymic T cell repertoire was indistinguishable. It should be noted, however, that we performed the repertoire analysis on the entire CD4 SP population including nTregs and activated T cells because we observed no differences within the thymocyte subsets between control and Prdm1 CKO mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) and comparable TCR activation measured by Nur77 induction in nTregs in both strains in vivo (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). It, therefore, is possible that the repertoire of activated thymocytes (nTregs or CD44+TCR+ CD4 SP) differs between Prdm1 CKO and control mice, and this requires further investigation. The lack of change in the repertoire of early T cells (thymocytes and naive CD4+ T cells) between lupus-prone Prdm1 CKO and control mice supports previous studies in which lupus development could be ameliorated by the sustained depletion of CD4 T cells (31) but not by early thymectomy (32). We found that thymocyte stimulation by DCs was not affected by BLIMP1 (Fig. 4 A and B). In contrast, greater peripheral naive CD4+ T cell proliferation and activation were observed with BLIMP1-deficient DCs compared to control DCs. The fraction of splenic naive CD4+ T cells showing a strong TCR signal following stimulation by BLIMP1-deficient DCs presenting OVA peptides was substantially higher compared to the fraction observed following stimulation by control DCs (Fig. 4 C and D). The increased Nur77 expression on stimulation with BLIMP1-deficient DCs indicates more effective TCR-mediated activation as cytokine signaling does not induce Nur77 expression (22). We show that this phenomenon is CTSS-dependent as it was abolished when the BLIMP1-deficient DCs were treated with a selective CTSS inhibitor. This finding supports the important role of antigen processing/ presentation in TCR stimulation since CTSS regulates both antigen processing and peptide loading to MHCII. Of note, there was no alteration of costimulatory molecules or expression level of MHC II in BLIMP1-deficient DCs after exposure to a CTSS inhibitor (12).

A low threshold for TCR activation influences the repertoire of antigen experienced activated CD4+ T cells in the periphery of Prdm1 CKO mice. It is known that T cell alterations exist which decrease the threshold for activation in SLE patients (reviewed in ref. 33). SLE T cells display increased basal intracellular Ca++ levels, hyperphosphorylation of Syk and CD3 epsilon chain, decreased levels of TCR zeta chain, and increased FcepsilonRIgamma chain (34–36). We did not observe differences in the levels of TCRβ or CD3 in naive CD4 T cells from control or Prdm1 CKO mice. In our study, the increased TCR signaling is not T cell intrinsic but rather is due to differences in activation by BLIMP1-deficient DCs which exhibit increased MHC II expression and differential processing of antigen. We previously reported an increased diversity in the TCR repertoire of Tfh cells in Prdm1 CKO mice, which we demonstrated to be associated with the upregulation of CTSS in these mice. Here, we show that the difference in the repertoire in T cells from Prdm1 CKO mice cultured under Tfh polarizing conditions is not due to changes in thymic selection, nor is it related to differences in the naive T cell repertoire in the periphery. Instead, our findings show that the deficiency of BLIMP1 in DCs lowers the activation threshold required for peripheral T cell activation. This finding is partially a consequence of the upregulation of CTSS in BLIMP1-deficient DCs, resulting in an increased presence of CLIP-loaded MHC II. This may lead to an enhanced presentation of peptide-loaded MHC II to T cells, including when the antigen concentration falls below the level required for control DCs to effectively stimulate T cells. Prdm1 CKO mice have an increased percentage of splenic memory T cells (CD44+CD62L−) (13), supporting our observation of increased peripheral T cell activation. Consistent with our previous observation of an increased number of Tfh cells in Prdm1 CKO mice (13), here, we show a heightened activation of T cells upon stimulation with BLIMP1-deficient DCs that were loaded with OVA antigen. Hyperresponsiveness to antigen resulted in increased T cell proliferation, an increased number of TCRαβ clonotypes in activated T cells, a trend toward greater diversity in the TCR repertoire of Nur77+ T cells, and upregulation of differentially expressed genes involved in the TCR signaling pathway. These data explain the more diverse repertoire of antigen-activated T cells in Prdm1 CKO mice.

Overall, our study demonstrates that BLIMP1 expression in DCs does not regulate T cell selection in thymocytes or naive CD4+ T cells emigrated from the thymus but regulates the threshold of T cell activation in the periphery and thus leads to an SLE-like phenotype. This is translationally important since more therapeutic opportunities, focused on APC–T cell interactions, are available when T cell activation rather than T cell selection leads to development of autoimmune disease.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

All the experiment was performed with 6- to 8-wk-old female mice unless gender or age was specified.

Prdm1 CKO mice (Prdm1fl/flCd11c-Cre+) and control mice (littermate control Prdm1fl/flCd11c-Cre−) on a C57BL/6 background are bred and maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research. OTII mice (stock number: 004194, B6.Cg-Tg (TcraTcrb) 425Cbn/J), Nur77-GFP mice (stock number: 016617, C57BL/6-Tg(Nr4a1-EGFP/cre)820Khog/J), and B6 CD45.1 mice (stock number: 002014, B6. SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ were purchased from Jackson laboratory. OTII mice and Nur77-GFP mice were cross-bred 2 generations to obtain OTII mice carrying Nur77-GFP (OTII Nur77-GFP). Hemizygote breeders of OTII Nur77-GFP were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research. Nur77-RFP mice were kindly provided from Dr. A. Rudensky (MSKCC, NY) and cross-bred to obtain Prdm1 CKO mice carrying Nur77-RFP (Prdm1 CKO.Nur77-RFP).

Sample size to achieve adequate power was chosen based on our previous studies with similar methods. We randomized the female or male mice from different cages and different time points to exclude cage or batch variation. Experiments and data analysis were performed without aforementioned genotype or treatment information.

Thymic DC, Thymocytes, and mTEC Isolation.

Thymic cell isolation was performed as described in the previous report (18). In brief, thymus lobes were washed with ice-cold HBSS, cut into 1 mm3 pieces and digested with RPMI medium supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 0.32 Wunsch U/mL Liberase/Thermolysin (Roche) and 50 KU/mL DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C for 40 min with gentle shaking. Enzymatic treatment was repeated for additional 20 min if needed, followed by incubation with 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) on ice for 10 min. Tissue fragments were mechanically dissociated by gentle pipetting. Cell suspensions were washed in ice-cold Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSs) containing 2% FCS and 2 mM EDTA to prevent aggregate formation. Each cell type was identified by lineage-specific markers by flow cytometry and isolated by FACAria for downstream procedures.

Flow Cytometry and Antibodies.

For flow cytometry analysis, single-cell suspension of cells was stained with the following antibodies: Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 506 (live/dead exclusion, eBioscience), anti-MHCII (M5/114.15.2), anti-CD62L (MEL-14), anti-CD64 (X54-5/7.1), anti-CD45 (30-F11), anti-CD8 (53-6.7), anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-CD11c (N418), anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-EpCAM1 (G8.8), anti-CD25 (PC61.5), anti-FOXP3 (FJK-16 s), anti-GITR (DTA-1), anti-PD1 (J43), anti-CD45.1 (A20), anti-CD45.2 (104), and anti-Ly51 (6C3).

For surface staining, cells were washed with staining buffer (HBSS containing 2% FCS and 1 mM EDTA), blocked with Fc blocker (2.4G2), and incubated with antibody cocktails for 20 min on ice protected from the exposure to direct sun. After the incubation, cells were washed with ice-cold staining buffer three times. For intracellular staining of FOXP3, cells were fixed and permeabilized using the Foxp3 fixation and permeabilization concentrate and diluent set (eBiosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

RNA Purification and qPCR.

Isolated cells were lysed in Trizol reagent (Life Technologies), and total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In-column DNase treatment was performed in all RNA isolation to prevent genomic DNA contamination. cDNA was generated from total RNA (200 ng) using an iScript synthesis kit (BioRad), and qPCR was performed by real-time PCR analysis. The following primers were purchased from Taqman gene expression assay (Invitrogen): Mm01255859_m1 (CtsS), Mm00516431_m1 (Irf4), Mm00839502_m1 (Polr2a), Mm00515597_m1 (Ctsl), Mm01187285_m1 (Prdm1), Mm03053303_s1 (Prdm1), Mm01149683_m1 (Aire), Mm00725448_s1 (Rplp0).PCR was performed using Light cycler 480 II (Roche). Polr2a and Rplp0 were used as housekeeping genes, and relative expression of each gene was calculated by ΔΔCt.

Library Preparation for TCRβ-Sequencing.

To generate TCRβ amplicon from T cells (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S3), RNA was purified from the TRIzol-lyzed cells (Cat. No. 15596018; Invitrogen) by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Cat. No. 74004; QIAGEN). The purified RNA was used as an input to synthesize cDNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions using SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System (Cat. No. 18091050; Invitrogen). To amplify mouse TCRβ cDNA, PCR was performed on the 50% volume of the first strand cDNA synthesized in a total volume of 350 µL with DreamTaq Hot Start DNA Polymerase (Cat. No. EP1702; Thermo Fisher Scientific), using TRBV primer mix and one TRBC primer with unique sample barcode sequences described in SI Appendix, Table S1 (37). The PCR was carried out under the following conditions: 95 °C for 2 min; 92 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s × 36 cycles; and 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR product was then diluted fivefold using DNA binding buffer (Cat. No. D4004-1-L; Zymo Research), column concentrated (Cat. No. 1003-50 and Cat. No. D4003-2-48; Zymo Research) and eluted into 15 µL of ultrapure water. The resulting ~500 bp TCRβ was gel-purified (Cat. No. 1003-50, Cat. No. D4004-1-100, and Cat. No. D4003-2-48; Zymo Research) and sequenced using Illumina MiSeq 2x300 platform.

Bioinformatic Analysis of Mouse TCRβ Repertoires.

SeqKit was utilized to extract sample barcodes from the raw fastq data of each mouse (38). The list of sample barcodes used in the study are described in SI Appendix, Table S1. The high-quality, paired-end reads were assembled using PEAR and then analyzed using MiXCR for germline gene annotation (39, 40). The annotated reads were then clustered using hierarchical clustering algorithm built in MiXCR with the default setting (40). After the clustering, clonotypes are defined as groups that share the same Vβ and Jβ gene usages with the same CDRβ3 amino acid sequences (Vβ + CDR3β +Jβ). The TCR repertoire feature was analyzed by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients, Jaccard similarity index, and Shannon diversity index. To calculate Pearson correlation coefficients, Vβ, Jβ, or Vβ + Jβ gene usages of the two independent mice either from the control mice groups or from CKO mice groups were subjected to measure the Pearson’s R. Jaccard similarity index for two datasets was calculated by counting the number of shared V +CDR3 +J and CDR3 clonotypes in both sets which were then divided by the size of the union of two datasets.

DC and T Cell Coculture.

CD11b+ DCs (MHCIIhiCD11chi) were isolated from spleens or from the thymus of age-matched female control or Prdm1 CKO mice (6- to 8-wk-old) by FACSAria. DCs were resuspended in complete RPMI media (RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS (HyClone, Lot# AE28209334), 1× penicillin-streptomycin and glutamine) at 5 × 105/mL with recombinant murine GM-CSF (20 ng/mL) and 100 µL (5 × 104 DCs) was plated at 96-well round bottom plate (Thermo fisher scientific). Naive CD4+ T cells (TCRβ+CD4+CD44−CD62L+) were isolated from spleens of 6- to 8-wk-old female control Nur77-GFP mice, OTII Nur77-GFP mice or OTII mice by an EasySep naive CD4+ T cell isolation kit followed by the manufacturer’s protocol (Stem cell technologies). CD4+ single-positive thymocytes (CD45+CD4+CD8−) were isolated from the thymus of 6- to 8-wk-old female OTII Nur77-GFP mice by the FACSAria cell sorter. We obtained the ~95% purity and viability of isolated cells consistently (analyzed by BD LSR Fortessa). The number of live cells was counted by Cellometer Auto2000. For OVA protein-derived antigen presentation, 10 or 1 µg/mL of OVA protein (InvivoGen) was added to DCs and incubated for 6 h before T cell coculture. CTSS inhibitor (1 nM) (Calbiochem-Millipore Sigma) was added during OVA protein incubation. For T cell proliferation, isolated T cells were labeled with 5 µM Cell trace violet (Invitrogen) before coculture with DCs. Proliferation and Nur77-GFP expression were calculated from FVD-negative live cells at the time of analysis. In vitro Tfh differentiation was enabled by addition of the following reagents: 10 µg/mL of each neutralizing antibodies [anti-IL-4 (11B11, Invitrogen), anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2, Invitrogen), and anti-TGFβ (1D11, R&D System)], and recombinant murine IL-6 (30 ng/mL) and IL-21 (50 ng/mL). Both recombinant cytokines were purchased from Peprotech.

In Vivo Proliferation of T Cells by Adoptive Transfer.

Recipient CD45.1 mice were subjected to a sublethal irradiated (6 Gy) of whole body. The next day, splenic naive CD4+ T cells and CD4 SP thymocytes were prepared by sorting using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) from donor mice. Naive CD4+ T cells and CD4 SP thymocytes were labeled with 5 µM of CellTrace violet or 1 µM of CellTrace far-red, respectively, and transferred into recipient mice by retro-orbital injection [total 2 × 106 (naive T: thymocytes = 1:1 ratio) in 0.1 mL saline]. Proliferation of transferred T cells was assessed at day 5.

Statistical Analyses.

Statistical significance was calculated and determined by an unpaired, nonparametric, Mann-Whitney U test or ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. No exclusion of sample was done.

Study Approval.

All the experiments conducted in this study strictly followed the guidance in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the NIH. The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Welfare of The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research (protocol number 2022-022). All the animals were euthanized at the end time point of experiments by CO2 instillation.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Christopher Colon (FIMR) for the help with cell sorting and flow cytometry, and Houman Khalili (FIMR) for the help with library preparation and management of the scRNA/TCR analysis. We thank Dr. Wayne Chaung and Dr. Kaitlin Carroll for their assistance with the adoptive transfer experiment. We also thank the Genome Sequencing and Analysis Facility at the University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin) for performing Illumina sequencing and to Dr. Lauren Ehrlich at UT Austin for constructive discussion in thymic selection. This work was supported by the NIAMS, US NIH R01 AR074565 to S.J.K., B.D., and for G.G. H.T. was supported by UTHealth Innovation for Cancer Prevention Research Training Program Post-Doctoral Fellowship (Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas grant no. RP160015). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas.

Author contributions

G.G., B.D., and S.J.K. designed research; K.L., J.P., H.T., and S.J.K. performed research; K.L., J.P., H.T., G.G., B.D., and S.J.K. analyzed data; and G.G., B.D., and S.J.K. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Reviewers: K.A.H., University of Minnesota Medical School Twin Cities; and G.C.T., Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

PRJNA983397 data have been deposited in PRJNA983398 (PRJNA983503) (41).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Klein L., Kyewski B., Allen P. M., Hogquist K. A., Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: What thymocytes see (and don’t see). Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 377–391 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xing Y., Hogquist K. A., T-cell tolerance: Central and peripheral. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a006957 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson M. S., et al. , Projection of an immunological self shadow within the thymus by the aire protein. Science 298, 1395–1401 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derbinski J., Schulte A., Kyewski B., Klein L., Promiscuous gene expression in medullary thymic epithelial cells mirrors the peripheral self. Nat. Immunol. 2, 1032–1039 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson M. S., et al. , The cellular mechanism of Aire control of T cell tolerance. Immunity 23, 227–239 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taniguchi R. T., et al. , Detection of an autoreactive T-cell population within the polyclonal repertoire that undergoes distinct autoimmune regulator (Aire)-mediated selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7847–7852 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry J. S. A., et al. , Distinct contributions of Aire and antigen-presenting-cell subsets to the generation of self-tolerance in the thymus. Immunity 41, 414–426 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang S., Fujikado N., Kolodin D., Benoist C., Mathis D., Immune tolerance. Regulatory T cells generated early in life play a distinct role in maintaining self-tolerance. Science 348, 589–594 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scarpino S., et al. , Expression of autoimmune regulator gene (AIRE) and T regulatory cells in human thymomas. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 149, 504–512 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scollay R., Bartlett P., Shortman K., T cell development in the adult murine thymus: Changes in the expression of the surface antigens Ly2, L3T4 and B2A2 during development from early precursor cells to emigrants. Immunol. Rev. 82, 79–103 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S. J., Gregersen P. K., Diamond B., Regulation of dendritic cell activation by microRNA let-7c and BLIMP1. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 823–833 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S. J., Zou Y. R., Goldstein J., Reizis B., Diamond B., Tolerogenic function of Blimp-1 in dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 208, 2193–2199 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim S. J., et al. , Increased cathepsin S in Prdm1(-/-) dendritic cells alters the TFH cell repertoire and contributes to lupus. Nat. Immunol. 18, 1016–1024 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brocker T., Survival of mature CD4 T lymphocytes is dependent on major histocompatibility complex class II-expressing dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 186, 1223–1232 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonasio R., et al. , Clonal deletion of thymocytes by circulating dendritic cells homing to the thymus. Nat. Immunol. 7, 1092–1100 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallegos A. M., Bevan M. J., Central tolerance to tissue-specific antigens mediated by direct and indirect antigen presentation. J. Exp. Med. 200, 1039–1049 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadeiba H., Butcher E. C., Thymus-homing dendritic cells in central tolerance. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 1425–1429 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts N. A., et al. , Prdm1 regulates thymic epithelial function to prevent autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 199, 1250–1260 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proietto A. I., et al. , Dendritic cells in the thymus contribute to T-regulatory cell induction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 19869–19874 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhattacharyya N. D., Feng C. G., Regulation of T helper cell fate by TCR signal strength. Front. Immunol. 11, 624 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashouri J. F., Weiss A., Endogenous Nur77 is a specific indicator of antigen receptor signaling in human T and B cells. J. Immunol. 198, 657–668 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moran A. E., et al. , T cell receptor signal strength in Treg and iNKT cell development demonstrated by a novel fluorescent reporter mouse. J. Exp. Med. 208, 1279–1289 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birnbaum K. D., Power in numbers: Single-cell RNA-seq strategies to dissect complex tissues. Annu. Rev. Genet. 52, 203–221 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu B., et al. , GADD45gamma mediates the activation of the p38 and JNK MAP kinase pathways and cytokine production in effector TH1 cells. Immunity 14, 583–590 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mauri D. N., et al. , LIGHT, a new member of the TNF superfamily, and lymphotoxin alpha are ligands for herpesvirus entry mediator. Immunity 8, 21–30 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takaba H., et al. , Fezf2 orchestrates a thymic program of self-antigen expression for immune tolerance. Cell 163, 975–987 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gardner J. M., et al. , Deletional tolerance mediated by extrathymic Aire-expressing cells. Science 321, 843–847 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamano T., et al. , Thymic B cells are licensed to present self antigens for central T cell tolerance induction. Immunity 42, 1048–1061 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hubert F. X., et al. , Aire regulates the transfer of antigen from mTECs to dendritic cells for induction of thymic tolerance. Blood 118, 2462–2472 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lei Y., et al. , Aire-dependent production of XCL1 mediates medullary accumulation of thymic dendritic cells and contributes to regulatory T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 208, 383–394 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Connolly K., Roubinian J. R., Wofsy D., Development of murine lupus in CD4-depleted NZB/NZW mice. Sustained inhibition of residual CD4+ T cells is required to suppress autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 149, 3083–3088 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hang L., Theofilopoulos A. N., Balderas R. S., Francis S. J., Dixon F. J., The effect of thymectomy on lupus-prone mice. J. Immunol. 132, 1809–1813 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crispin J. C., Kyttaris V. C., Juang Y. T., Tsokos G. C., How signaling and gene transcription aberrations dictate the systemic lupus erythematosus T cell phenotype. Trends Immunol. 29, 110–115 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vassilopoulos D., Kovacs B., Tsokos G. C., TCR/CD3 complex-mediated signal transduction pathway in T cells and T cell lines from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 155, 2269–2281 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liossis S. N., Ding X. Z., Dennis G. J., Tsokos G. C., Altered pattern of TCR/CD3-mediated protein-tyrosyl phosphorylation in T cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Deficient expression of the T cell receptor zeta chain. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 1448–1457 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enyedy E. J., et al. , Fc epsilon receptor type I gamma chain replaces the deficient T cell receptor zeta chain in T cells of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 44, 1114–1121 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ndifon W., et al. , Chromatin conformation governs T-cell receptor Jbeta gene segment usage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 15865–15870 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen W., Le S., Li Y., Hu F., SeqKit: A cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for FASTA/Q file manipulation. PLoS One 11, e0163962 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J., Kobert K., Flouri T., Stamatakis A., PEAR: A fast and accurate illumina paired-end reAd mergeR. Bioinformatics 30, 614–620 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolotin D. A., et al. , MiXCR: Software for comprehensive adaptive immunity profiling. Nat. Methods 12, 380–381 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park J., TCRb amplicons of Splenic naive CD4+ T in control and Prdm1 CKO mice. NCBI BioProject. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA9833975. Deposited 13 June 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

PRJNA983397 data have been deposited in PRJNA983398 (PRJNA983503) (41).