Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the benefits of a primary progressive aphasia (PPA) education and support session for people with PPA (pwPPA) and their caregivers.

Method:

Thirty-eight individuals (20 pwPPA, 18 caregivers) were invited to participate in the study. Twenty-five individuals (12 pwPPA, 13 caregivers) completed questionnaires before and after an education and support group session provided by a speech pathologist and a clinical psychologist. Seven individuals (2 pwPPA, 5 caregivers) participated in follow-up interviews.

Results:

After one attendance, caregivers reported significant improvement in knowledge of PPA, strategies to manage worry and low mood, and opportunities to meet peers. Themes at interview were reduced feelings of isolation, increased feelings of support, increased knowledge of coping strategies, and improved understanding of PPA. Caregivers who had attended previous sessions reported increased feelings of well-being and support.

Implications:

Primary progressive aphasia education and support group sessions in the postdiagnostic period constitute a valuable component of comprehensive care for PPA.

Keywords: primary progressive aphasia, dementia, communication, education, support, group intervention

Introduction

Language impairment is the preeminent feature of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and the loss of communicative ability impacts personal relationships, social participation, and well-being for people with PPA (pwPPA) and their caregivers. 1,2 The insidious deterioration of language in PPA gives rise to complex problems. With gradual loss of communication, pwPPA lose independence in communicative activities of daily living. 3 As PPA is frequently a young-onset dementia, it can be associated with financial stress and relinquishment of life goals. 4,5 Although increasingly presenting to health-care services, 6 PPA remains a rare condition, 7 which is underserviced and underresourced. 8 Consequently, pwPPA and their caregivers have difficulty accessing information and support from health-care professionals and peers.

Understanding the nature of PPA and the underlying disease process is one of the first difficulties for pwPPA and their caregivers. Even when information is provided, individuals may be informed of the diagnosis with unfamiliar, complex terminology. For example, they may be informed of the PPA variant. Three PPA variants, each a unique speech-language syndrome reflecting the topography of damage to the brain, are currently described; semantic variant PPA (svPPA), nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA (nfvPPA), and logopenic variant PPA (lvPPA). 9 People with PPA and their caregivers may also be informed of the neurodegenerative disease likely to be associated with the clinical presentation, typically frontotemporal lobar degeneration or Alzheimer’s disease. As up to 40% of PPA cases may not readily be able to be categorized to 1 of the 3 variants, 10 some pwPPA and their caregivers may be required to grapple with complex terminology and uncertainty about more than 1 variant and pathology type. For pwPPA and their caregivers, at the time of receiving a devastating diagnosis and prognosis, often at a single consultation, the unfamiliar nomenclature, the heterogeneity of the variants, and the difficulties with variant diagnosis can be barriers to understanding PPA. The intervention evaluated in this study aimed to help pwPPA and their caregivers understand this complex syndrome, provide information on managing worry and low mood, and access peer support.

Although dementia education and support groups are designed to assist individuals and their caregivers with the challenges of living with dementia, the unique burden resulting from impaired communication in PPA may not be addressed by existing services. 11 Typically, in Australia, education and support groups provided for people with dementia and their families focus on the stresses that arise from the cognitive and memory impairments typical of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. 12 Research on poststroke aphasia shows that people with aphasia and their caregivers report satisfaction with education and support groups, particularly as they enhance social networks and community access. 13 These services, however, are not suitable for individuals with PPA as the trajectory of the poststroke and progressive aphasia syndromes differ so radically, and goals of restoration of language function are not appropriate for pwPPA. 8,14 Instead, PPA-specific education and support programs are required. 4,8,11 Caregivers of individuals with frontotemporal dementia benefitted from support groups, which addressed their specific needs with participants reporting improved knowledge and understanding of the disease, and valuing mutual support and sharing of coping strategies. 15

Three recent studies describe PPA-specific education and support groups. 11,14,16 Jokel and colleagues 16 developed a structured group intervention program exclusively for pwPPA and their caregivers, prompted by clinical need. The program provided ten 2-hour weekly sessions, which included language activities, learning communication strategies, counseling, and education. The authors collected data before and after the program using outcome measures such as American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Quality of Communication Life Scale, 17 spousal questionnaires, and qualitative feedback. The 10 participants (5 pwPPA and 5 spouses) in the treatment group demonstrated improvements in quality of communication and coping strategies. 16 Morhardt et al 11 used a field note analysis approach to evaluate a tailored psychoeducational support program and concluded it was beneficial for the 9 pwPPA and 8 caregivers who participated in the formal intervention group. In their intervention phase, ten 90-minute bimonthly sessions were provided, which enabled participants to engage socially and share experience with peers and were found to increase feelings of confidence and empowerment. Although participants in this study demonstrated a preference for support rather than education, when reporting on education they received, they demonstrated their preference for practical education on strategies to enhance communicative ability. Mooney et al 14 reported a combined approach that provided education, support, and training in the implementation of multimodal compensatory strategies to 5 individuals with PPA and their 5 caregivers. This program consisted of 12 1-hour biweekly sessions. The authors concluded this model was feasible and valued by pwPPA and their caregivers and resulted in positive outcomes for the participants.

The PPA education and support group programs described in the literature to date are resource intensive. 11,14,16 Although providing evidence of effectiveness, the delivery of such extensive programs may not be feasible for public health facilities with scarce health resources. As well, families living in regional or rural areas may have great difficulty committing to multiweek programs in a major metropolitan city. This study evaluated our ongoing, less extensive PPA-specific education program as part of a quality improvement initiative conducted at a dedicated PPA speech pathology clinic, in order to identify an effective service delivery model for this publicly funded, outpatient clinic providing care to people from across the Australian state of New South Wales (population 7.5 million, 809 000 square km). It is currently, to our knowledge, the only specific PPA education and support program provided in this state and referrals are accepted from across the state. Our goal in carrying out this research, within provision of clinical services, is to provide evidence to drive improvement and expansion of limited existing clinical services for pwPPA and their families and caregivers. The aim of this study is to evaluate the benefits of a 3-hour PPA-specific group education and support session for pwPPA and their caregivers.

Methods

This study was approved as a clinical quality improvement initiative by the Human Research Ethics Committee of South Eastern Sydney Local Health District, New South Wales.

Participants

People with PPA in this study were referred to a hospital outpatient specialist PPA clinic in Sydney by the Frontotemporal Dementia Research Group in Sydney, or by individual neurologists, geriatricians, and local medical officers. Caregivers of pwPPA attending were all the primary communication partners of the pwPPA, including spouses, life partners, and adult children. As part of their clinical care, pwPPA and their caregivers were invited to a PPA-specific group education and support session held between 1 and 12 weeks following their presentation to the PPA clinic. The session was held on 4 occasions, and, in total, 38 people (20 pwPPA and 18 caregivers) were invited to attend a session, and all participants were invited to participate in our study evaluating the session they attended. Twenty-five participants (12 pwPPA, 13 caregivers of pwPPA) consented to participate verbally and by anonymously completing and returning the evaluation questionnaire.

A number of participants had previously attended a PPA-specific education and support session, with the same goals but some differences in content to the session described in Table 1, on 1 or 2 occasions before this study commenced. These participants only completed one survey, at the most recent attendance during the data collection period. These participants’ responses are described and analyzed separately from the responses of those who were attending their first session.

Table 1.

Overview of PPA-Specific Group Education and Support Session.

| Components of the PPA-specific group education and support session |

|---|

| Disease education presented by the speech

pathologist This 45-minute presentation included information on dementia syndromes, PPA and the 3 variants of PPA, the neuroanatomical bases of PPA and causative neurodegenerative conditions, aspects of language processing and cognition, and recent relevant research findings. |

| Psychoeducational and practical strategies for managing

stress, worry, and low mood presented by the clinical

psychologist The 1-hour presentation aimed to educate participants, both pwPPA and carers, on understanding anxiety and depression within the context of adjustment to a new diagnosis of degenerative disease, progressive loss of function, and changed relationship roles. Psychoeducation aimed to provide participants with the awareness and recognition of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms of anxiety and depression, and an understanding that these can occur for pwPPA and/or carers. The majority of the session focused on providing participants with practical strategies to manage anxiety and depression, using examples relevant to pwPPA, such as returning to a regular meal out with friends (social activity) while considering environmental variables that may affect communication (such as restaurant noise levels, time of day). Caregiver stress was also addressed, including the need to ensure optimal self-care. Participants were provided with a copy of the presentation slides as a resource, which included information on how to seek further psychological support. The clinical psychologist also participated in individual and group discussion with participants following her presentation. |

| Practical strategies for maximizing communication presented

by the speech pathologist This 45-minute presentation focused on practical strategies to maximize communication. As well as education strategies to enhance communication, participants were provided with practical examples of resources such as “in case of emergency” cards, communication books, life story books, “starting a conversation” script cards, and café cards. Strategies to minimize barriers to communication, such as modifying the physical environment and providing facilitators such as appropriate technology, including appropriate apps for tablets and smartphones, were presented. Written educational materials and links to relevant websites that could be shared with nonattending family members and friends were also provided. |

| Peer support Interaction and discussion during group sessions was encouraged and a midsession break of 30 minutes, with tea and coffee, was included to encourage interaction among participants. |

Abbreviations: PPA, primary progressive aphasia; pwPPA, people with primary progressive aphasia.

Procedure

Intervention

People with PPA and their caregivers attended a PPA-specific group education and support session conducted collaboratively by a speech pathologist (C.T.R.) and a clinical psychologist (L.A.). Attendance was by choice, subsequent to receiving a written invitation. All those invited to attend the education and support sessions were members of a dyad with 1 person with PPA receiving care from the Uniting War Memorial Hospital PPA Clinic providing the session. For those who declined, reasons given for nonattendance included overseas travel, other appointments, leisure and sporting activities, or the caregiver’s work schedule. The session had a duration of 3 hours, with a midsession break providing opportunity for less formal discussion. The aims of the session were to provide (1) disease education, (2) psychoeducational and practical strategies for managing negative feelings associated with the diagnosis, (3) practical strategies to enhance successful communication, and (4) opportunities for peer support. The group session was presented by a speech pathologist with 12 years’ experience with adults with PPA (C.T.R.) and a clinical psychologist experienced in working with adults with neurodegenerative disease and communication disorders (L.A.) and contained 4 components, as summarized in Table 1.

Evaluation

Participants anonymously completed pre- and postintervention evaluations. The pre- and postevaluation questionnaires were bound in one booklet and were provided in aphasia friendly format with a large font size and extra blank space for all participants. 18 The booklet had 2 parts; the first part to be completed before commencement of the formal session and the second part to be completed at the conclusion of the formal session. The first question asked participants to respond, with “yes” or “no” to the statements: “I am living with PPA” and “I am the partner or caregiver of someone living with PPA.” The next question asked participants to respond, with “yes” or “no” to the statement: “This is my first attendance at a War Memorial Hospital PPA education and support session.” Participants were then asked to rate their response to 6 statements on 5-point Likert scales. The statements were designed to probe the success of the program achieving its aims. The same 6 statements were repeated immediately following the group session (see Online Appendix A). Both pre- and postevaluation forms also asked both pwPPA and their caregivers to add any additional comments they might have.

Follow-up interviews were conducted with a smaller cohort of pwPPA and caregivers who had attended the education and support session. This subgroup was a convenience sample comprised of those 7 participants who either attended the clinic or were available for telephone interview in the week chosen to conduct the follow-up. Seven individuals participated and 6 standard questions were asked during all interviews (see Online Appendix B). The content of the interviews was captured with field notes.

Data analysis

Responses to completed pre- and postintervention evaluations were analyzed with nonparametric statistics. The change in scores for each group on each scale served as the primary outcome measure of the intervention. As scores were rankable and from 2 related conditions, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to test for significance of the difference between the Likert scale rating at each time point, for each group. Comments that were provided on the evaluations were extracted and collated.

The field notes from the interviews with 7 participants were examined to identify themes. 19 The first and second authors familiarized themselves with the notes and developed a thematic framework with reference to the responses and comments provided in the evaluations. This thematic framework was applied to the transcribed comments and coded accordingly. After charting the coded data, themes were mapped and agreed upon by the first and second authors. The thematic framework was reviewed by a speech pathologist working in the clinic where the groups were conducted, but who had not been present at any of the sessions, and inconsistencies were identified, discussed, and resolved.

Results

The overall response rate to the evaluations was 66% (25/38), with 60% (12/20) of pwPPA and 72% (13/18) of caregivers completing both the pre- and postintervention evaluations. Completed questionnaires were received from 4 pwPPA and 7 caregivers who were attending a PPA-specific education and support session for the first time and from 8 pwPPA and 6 caregivers who had attended a previous session.

Pre- and Postintervention Evaluations

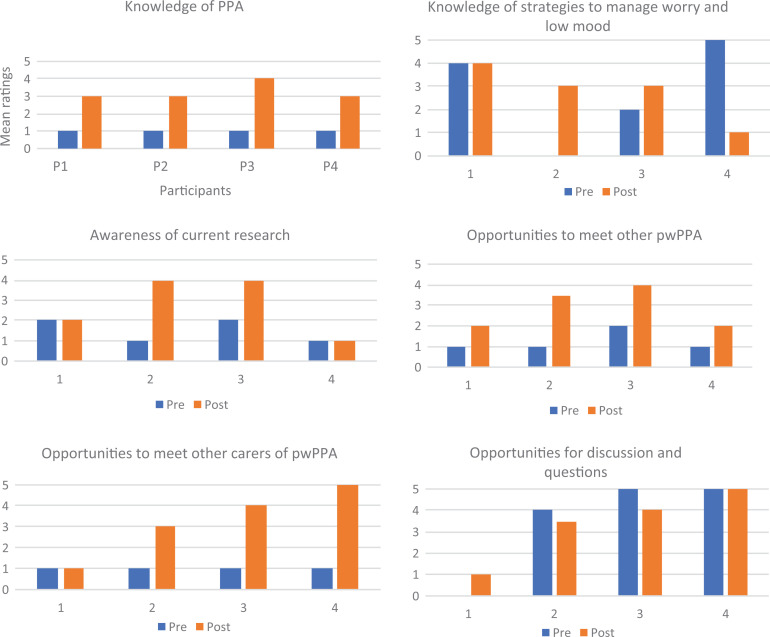

Results from Likert scale ratings are summarized in Table 2. The group of pwPPA who had attended just 1 session was too small for reliable statistical analysis (n = 4). The pre- and postintervention raw scores on Likert scales for each individual’s response to the statements are instead shown in Figure 1. Visual analysis suggests positive benefits to these individuals on some measures: All 4 pwPPA increased their rating of knowledge of PPA and opportunity to meet other pw PPA. Three of the 4 increased their rating of opportunities to meet other caregivers of pwPPA. Two particpants, P2 and P3 increased their rating of their own awareness of current research in PPA. There was no obvious pattern in the ratings for the remaining 2 statements: knowledge of strategies to manage worry and low mood and opportunities for discussion and questions.

Table 2.

Mean and Standard Deviation of Pre- and Postintervention Ratings for Participant Groups on a 5-Point Likert Scale (From 1, “Very little” or “Disagree,” to 5, “Quite a Lot/All I Need” or “Agree”).a

| pwPPA 1 Session, n = 4b | pwPPA >1 Session, n = 8 | Caregiver 1 Session, n = 7 | Caregiver >1 Session, n = 6 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | |||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| How much I know about PPA | 1.00b | (0.00) | 3.25 | (0.50) | 3.69 | (1.07) | 4.06 | (0.78) | 1.64 | (0.85) | 3.50c | (0.50) | 3.17 | (1.33) | 4.17d | (0.41) |

| How much I know about managing worry and low mood | 2.75b | (2.22) | 2.75b | (1.26) | 3.81 | (0.46) | 4.13c | (0.58) | 2.00 | (1.00) | 3.71c | (0.95) | 2.50 | (0.84) | 3.83d | (0.75) |

| How much I know about current research in PPA | 1.50b | (0.58) | 2.75b | (1.50) | 3.56 | (1.02) | 3.88 | (0.79) | 2.36 | (1.38) | 3.64c | (1.55) | 3.67 | (1.37) | 4.00 | (0.89) |

| I have met other pwPPA | 1.25b | (0.50) | 2.88b | (1.03) | 4.38 | (0.58) | 4.25 | (0.76) | 1.71 | (1.50) | 4.14c | (1.21) | 4.17 | (1.1) | 4.50 | (0.84) |

| I have met other carers of pwPPA | 1.00b | (0.00) | 3.25b | (1.71) | 4.38 | (0.79) | 4.50 | (0.80) | 1.57 | (1.51) | 4.07c | (1.43) | 4.17 | (1.17) | 4.33 | (0.82) |

| I have opportunities to ask questions | 3.50b | (2.38) | 3.38b | (1.70) | 4.63 | (0.44) | 4.44 | (0.73) | 2.57 | (1.72) | 4.00 | (1.29) | 3.75 | (1.41) | 4.33 | (0.82) |

Abbreviations: M, mean; PPA, primary progressive aphasia; pwPPA, people with primary progressive aphasia; SD, standard deviation.

a Shaded areas indicate significant difference in mean scores.

b No statistical analysis conducted because of small n.

c Wilcoxon signed-rank test: P < .01 (1 tailed).

d Wilcoxon signed-rank test: P < .025 (1 tailed).

Figure 1.

Pre- and postintervention raw scores for people with primary progressive aphasia who attended 1 session only.

For the group of pwPPA for whom the intervention was their second or subsequent group session and who completed evaluations before and after their second (or later) session (n = 8), there was very little change in mean ratings, except for significant improvement in their rating of knowledge of strategies to manage worry and low mood (w = 0, P < .01, 1 tailed; see Table 2).

For the group of caregivers of pwPPA for whom the intervention session was the first session attended, there was a significant improvement in their ratings of knowledge of PPA (w = 0, P < .01, 1 tailed), knowledge of strategies to manage worry and low mood (w = 0, P < .01, 1 tailed), and opportunities to meet other pwPPA (w = 0, P < .01, 1 tailed), and caregivers (w = 0, P < .01, 1 tailed; see Table 2).

For the group of caregivers of pwPPA for whom the intervention session was a second or subsequent session, there was a significant improvement in their rating of knowledge of PPA and knowledge of strategies to manage worry and low mood (w = 0, P < .025, 1 tailed; see Table 2).

Themes Identified in Interviews

A subset of the participants agreed to follow-up interviews. These data were identifiable. The 7 individuals who participated in the follow-up interviews were all female, with a mean age of 67.7 years (range: 64-71 years) and with the mean time since the person with PPA’s onset of symptoms of 30 months (range: 18-60 months). Five respondents were caregivers (3 of people with lvPPA, 2 of people with nfvPPA) and 2 were people with lvPPA. Prominent themes identified from analysis of the interviews and content of the interviews that typify the themes were:

-

1. Reduced feelings of isolation and increased feelings of well-being and support.

“I think I have found being with other people, carers, and researchers and pwPPA…I feel it’s very beneficial.….” (caregiver)

“You get an opportunity to see other [sic] the same as you. That’s quite rare.” (person with PPA)

-

2. Improved understanding of PPA.

“I gain a better understanding every time.” (caregiver)

“Even this third time, I feel we’re still learning.” (caregiver)

“That tells me everything that I’ve not known properly” (pointing to a diagram of types of dementia). (person with PPA)

“We’ve been to ‘Living with Dementia’ (note 1) and ‘iREAP’ (note 2), but this came from a different angle, more specific. It addressed our problems.” (caregiver)

-

3. Increased knowledge of coping strategies from sharing with peers.

“Seeing how other carers are coping and what they say and what they do…strategies…get tips.” (person with PPA)

“I find out so much from other people.” (person with PPA)

“Gathering information about opportunities for new ideas that might improve your speech.” (person with PPA)

-

4. Providing advice and support to peers.

“I feel sorry if they can’t cope where I’ve got quite a good idea.” (person with PPA)

“Give information about yourself and I think that’s really helpful.” (person with PPA)

Discussion

The aim of this research is to evaluate the benefits of a group session that provided PPA-specific education and support for pwPPA and their caregivers. The results suggest that pwPPA and their caregivers benefit from a group education and support session, whether attending for the first time or having attended previously. This adds to emerging evidence that education and support groups should be integral to comprehensive care of this clinical population.11,14,16

The notable finding of our study is that caregivers of pwPPA report benefits from a single attendance at a group education and support session. Although the service delivery models currently described in the literature have involved extensive programs spread over multiple attendances with a consistent group, 11,14,16 our data indicating the benefit from attendance at even a single PPA-specific session is important, where that service delivery model cannot be provided. This may be the case in the public hospital sector where speech pathology and psychology services for dementia care often receive a low priority and resources are limited. Moreover, even when multiattendance education and support sessions are available, there can be considerable barriers to access for families living in regional and rural areas. Additional responsibilities that the caregiver may be required to assume can also pose a barrier to attendance. The model of service delivery described in this study offered a single session to those with a recent diagnosis but also allowed individuals to attend more than once if they so wanted and those who did found it helpful.

For those with dementia and their families and caregivers, postdiagnostic counseling services are currently inadequate. 20,21 There are personal stories from those living with PPA that also attest to the devastation of being left with the diagnostic label and minimal information or support. 22 There is also a clear need for ongoing education and support, and contact with health professionals but this area, in our experience, is poorly resourced. We do not advocate that one session will be sufficient to support individuals and families through the PPA journey, but this study does provide an indication that all people with a recent diagnosis of PPA should be provided with, and are likely to benefit from, the opportunity to access education and support from peers and health professionals in the initial period postdiagnosis.

Benefits of Speech Pathology Education and Support

All participants in this study accessed PPA-specific education and support as a result of their speech pathology care management plan. The PPA-specific education and support enabled improved understanding of their complex syndrome and disease process. They reported reduced feelings of isolation due to the opportunity provided to meet and share with peers. In addition, we believe that, by addressing psychological issues in the session, speech pathology “opened the gate” for these participants to access clinical psychology.

Benefits of Clinical Psychology Education and Support

Our findings suggest that the component provided by the clinical psychologist, which aimed to empower individuals to manage the worry and low mood associated with PPA, was highly valued by both pwPPA and their caregivers. This is consistent with earlier findings that pwPPA and their caregivers highly value practical strategies to assist living with PPA. 11 In addition, the participants gained awareness of the scope and availability of psychology services. It is plausible that the attendance at the session may have led to early intervention with a preventive effect. Future studies could investigate this further.

Benefits of Peer Support

Caregivers for whom the intervention session was not their first suggested in their comments that they continued to feel well supported by the access to peers and health professionals provided by group sessions. It is recognized that those with rare dementia syndromes benefit from the support of peers. 15,23 Notable in our study were the comments of pwPPA regarding the positive opportunity afforded by the group session to be active providers of information and support to their peers. This altruistic theme was unique to the interview responses of the pwPPA, not seen in the responses of the caregivers.

Changes to Service Delivery Resulting From Evaluation

The finding that attending even a single PPA-specific group session may be beneficial to pwPPA and their caregivers has prompted a change in our clinical practice: the introduction of a recommendation that all pwPPA and their caregivers have access to a minimum of one PPA-specific group education and support session.

Further, based on the current findings highlighting the value of peer support, we have also changed our practice by also offering impairment-focused (lexical retrieval) treatment in a small group, rather than individual, context. Caregivers of pwPPA report that home-based treatment can be lonely and socially isolating and therefore maintaining adherence can be difficult. 24 The value of group treatment delivery, over and above education and support, requires further investigation. It is promising that 3 of 5 pwPPA in the active language treatment group in Jokel’s program demonstrated changes on the Quality of Communication Life Scale 17 postintervention, indicating improved communication confidence. 16

Assessing What PwPPA Want

Morhardt and colleagues 11 found that talk-based evaluations were challenging for individuals with communication impairment. We found that a written evaluation form, although provided in an aphasia-friendly format, was a greater barrier to pwPPA expressing their opinion than interviews: The individual face-to-face interview was more effective, providing more information for the 2 individuals with PPA, than the written evaluation in this study. The response rate of pwPPA for the written evaluation was lower than the caregivers and many requested individual support to complete the questionnaires. In addition, many of the comments provided by pwPPA were inconsistent with their responses to the Likert scales. For example, one person with PPA did not change her ratings on the pre- and postevaluations but wrote in her comment, “the information provided was great. I’m glad I came.” Another corrected the wording of the statements to reflect her opinion and did not use the Likert scales at all. This inconsistency between responses by pwPPA on the Likert scale and the interview may have been reduced by improved internal validity of the tools. The inconsistent responses may also be associated with the cognitive and linguistic profiles of some participants with PPA and their impaired ability to respond to written text compared with a spoken interview; the task may be too challenging. Be that as it may, the few comments the pwPPA provided on the written evaluations and those made by the 2 pwPPA who participated in the follow-up interviews were positive. Our sample size of pwPPA was small and limited our ability to draw conclusions. The cohort of 12 pwPPA who completed the written evaluations represented only 60% of the larger cohort of 20 pwPPA invited to participate in the study, and this further reduces the robustness of any conclusions. Thus, the challenge remains of how best to establish what pwPPA want in a comprehensive PPA service.

Additional Considerations

Greater insights could have been gained with participants’ disease and demographic characteristics linked to their responses. However, our data were anonymous in order to reduce the risk of subject expectation bias. 25 The self-selected participant group was recruited from a publicly funded PPA clinic and was typical of the clinical caseload, thus increasing the ecological validity of our study. The participant group reflected the heterogeneity of the PPA population with a diversity of type and severity of language impairment. As all data were anonymous, we are also unable to comment on the possibility that selection bias may have occurred. It may be that those who attended were highly motivated and thus more likely to respond positively to the survey.

We present valuable insights from the lived experience of pwPPA and caregivers of pwPPA. However, we acknowledge the limitation that the participants in the interview component of the study were either people with lvPPA or caregivers of people with lvPPA and nfvPPA. We, therefore, cannot claim that these insights are pertinent to all pwPPA and caregivers of pwPPA and further research with a larger more diverse sample could provide additional insights.

In this study, resources did not allow for 2 separate groups: one for pwPPA and one for caregivers/family members and we acknowledge this is not ideal. Although the aforementioned was the procedure for the Jokel’s study, participants in that study, pwPPA and caregivers, collaboratively determined that pwPPA and caregivers either combined or alone would be their preferred option for a future program (Jokel et al, 2017). Finally, a waitlist control group would strengthen conclusions about the benefits of access to education and group support (Jokel et al, 2017); however, in our context, this would delay delivery of care to some individuals and compete with our aim of providing education and support at the earliest opportunity.

Conclusion

This study adds further evidence that PPA-specific group education and support is beneficial for pwPPA and their caregivers. We demonstrate that attendance at a single session in the early months postdiagnosis may be beneficial for pwPPA and their caregivers and can be a cost-effective, valuable component of comprehensive ongoing care for this expanding clinical caseload. The inclusion of education regarding practical strategies to manage worry and low mood associated with a PPA diagnosis appeared to be particularly valued by caregivers and pwPPA. Furthermore, pwPPA appeared to benefit from the positive opportunity afforded by a group session, to be active providers of information and support to their peers.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, Appendices for Primary Progressive Aphasia Education and Support Groups: A Clinical Evaluation by Cathleen Taylor-Rubin, Lisa Azizi, Karen Croot and Lyndsey Nickels in American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their generous assistance with this study. The authors are also grateful to Alexis McMahon, speech pathologist, St Vincents Hospital, for her assistance with analysis of interviews.

Notes

An education and support program conducted by Dementia Australia.

An outpatient integrated rehabilitation care program conducted by War Memorial Hospital, Sydney.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Lyndsey Nickels was funded by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT120100102).

ORCID iD: Cathleen Taylor-Rubin  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4236-7401

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4236-7401

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Cartwright J, Elliott KAE. Promoting strategic television viewing in the context of progressive language impairment. Aphasiology. 2009;23(2):266–285. doi:10.1080/02687030801942932. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Medina J, Weintraub S. Depression in primary progressive aphasia. J Geriatr Psych Neur. 2007;20(3):153–160. doi:10.1177/0891988707303603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Le Rhun E, Richard F, Pasquier F. Natural history of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2005;65(6):887–891. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000175982.57472.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nickels L, Croot K. Understanding and living with primary progressive aphasia: current progress and challenges for the future. Aphasiology. 2014;28(8-9):885–889. doi:10.1080/02687038.2014.933521. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaiser S, Panegyres PK. The psychosocial impact of young onset dementia on spouses. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis Other Demen. 2007;21(6):398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taylor C, Kingma R, Croot K, Nickels L. Speech pathology services for primary progressive aphasia: exploring an emerging area of practice. Aphasiology. 2009;23(2):161–174. doi:10.1080/02687030801943039. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Knopman DS, Roberts RO. Estimating the number of persons with frontotemporal lobar degeneration in the US population. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;45(3):330–335.doi:10.1007/s12031-011-9538-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Volkmer A, Spector A, Beeke S, Warren JD. Speech and language therapy for primary progressive aphasia: referral patterns and barriers to service provision across the U.K. Dementia. 2018. doi:10.1177/1471301218797240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006–1014. doi:10.1212/wnl.0b013e31821103e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sajadi SA, Patterson K, Arnold RJ, Watson PC, Nestor PJ. Primary progressive aphasia: a tale of two syndromes and the rest. Neurology. 2012;78(21):1670–1677. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182574f79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morhardt D, O’Hara M, Zachrich K, Wieneke C, Rogalski E. Development of a psycho-educational support program for individuals with primary progressive aphasia and their care-partners. Dementia (London). 2017;00(00):1–18. doi:147130121769967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Living with Dementia Program. Dementia Australia website. https://www.dementia.org.au/support/…and-programs/…/living-with-dementia-program. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- 13. Lanyon L, Rose M, Worrall L. The efficacy of outpatient and community-based aphasia group interventions: a systematic review. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2013;15(4):359–374. doi:10.3109/17549507.2012.752865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mooney A, Beale N, Fried-Oken M. Group communication treatment for individuals with PPA and their partners. Semin Speech Lang. 2018;39(3):257–269, doi:10.1055/s-0038-1660784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Diehl J, Mayer T, Förstl H, Kurz A. A support group for caregivers of patients with frontotemporal dementia. Dementia-London. 2003;2(2):151–161. doi:10.1177/1471301203002002002. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jokel R, Meltzer J, D R J, et al. Group intervention for individuals with primary progressive aphasia and their spouses: who comes first? J Commun Disord. 2017;66:51–64. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paul DR, Frattali CM, Holland AL, Thompson CK, Caperton CJ. Quality of Communication Life Scale (ASHA QCL). Rockville, MD: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Worrall L, Rose T, Howe T, et al. Access to written information for people with aphasia. Aphasiology. 2005;19(10-11):923–929. doi:10.1080/02687030544000137. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320(7227):114–116. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. http://simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/docview/1777606314?accountid=12219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tagor A. Post-diagnostic support services should be included in new dementia targets. BMJ. 2013;347:15509. doi:10.1136/nmj.15509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Swaffer K. Dementia and prescribed disengagement. Dementia. 2015;14(1):3–6. doi:10.1177/14713012114548136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rutherford S. Our journey with primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology. 2014;28(8-9):900–908. doi:10.1080/02687038.2014.930812. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walton J, Ryan N, Crutch S, Rohrer J, Fox N. The importance of dementia support groups. BMJ. 2015;351:h3875. doi:10.1136/bmj.h3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Taylor-Rubin C, Croot K, Nickels L. Adherence to lexical retrieval treatment in primary progressive aphasia and implications for candidacy. Aphasiology. 2019;33(10):1182–1201. doi:10.1080/02687038.2019.1621031. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williams JB, Popp D, Kobak KA, Detke MJ. P-640- The power of expectation bias. European Psychiatry. 2012;27(1). doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(12)74807-1. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, Appendices for Primary Progressive Aphasia Education and Support Groups: A Clinical Evaluation by Cathleen Taylor-Rubin, Lisa Azizi, Karen Croot and Lyndsey Nickels in American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias