Abstract

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are not terminally differentiated but can acquire effector properties. Here we report an increased expression of Human Endogenous Retrovirus 1 (HERV1-env) proteins in Tregs of patients with de novo autoimmune hepatitis and autoimmune hepatitis which induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. HERV1-env-triggered ER stress activates all three branches (IRE1, ATF6, and PERK) of the with Unfolded Protein Response (UPR). Our co-immunoprecipitation studies show an interaction between HERV1-env proteins and the ATF6 branch of the UPR. The activated form of ATF6α activates the expression of RORC and STAT3 by binding to promoter sequences and induces IL-17A production. Silencing of HERV1-env results in recovery of Treg suppressive function. These findings identify ER stress and UPR activation as key factors driving Treg plasticity. (Species: human).

Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic necroinflammatory liver disease of unknown etiology featuring interface hepatitis by T cells, macrophages, and plasma cells that invade the periportal parenchyma (1, 2). The incidence and prevalence of AIH is 0.4 and 3.0 cases per 100,000 children respectively (3), and ~17 per 100,000 population in adults (4–9). Characteristic features of AIH include elevation of liver enzymes, detectable autoantibodies, elevation of serum immunoglobulin G levels, and interface hepatitis with plasma cell infiltration in liver histology (10). The trigger that activates the innate and adaptive immune response leading to tissue injury in AIH remains unknown (11). Putative mechanisms posited for autoimmune liver injury include presentation of self-antigens to naive CD4+ and CD8+ effector T cells (12–14). Depending on the prevailing cytokine milieu, differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into Th1 cells occurs and leads to production of IL-2 and IFN-γ and concomitant activation of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes that produce IFN-γ and TNF. Exposure of hepatocytes to IFN-γ results in upregulation of MHC class I molecule and aberrant expression of MHC class II molecules, leading to further T cell activation and perpetuation of liver damage (12–14). IFN-γ also induces monocyte differentiation, promotes macrophage activation, and contributes to increased NK cell activity (15, 16). Differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into Th2 cells leads to secretion of cytokines essential for B cell maturation to plasma cells that secrete autoantibodies. Autoantibodies can induce damage through antibody-mediated cellular cytotoxicity and complement activation (17). Although Th17 cells have been reported in AIH, their role in the pathogenesis of AIH is under investigation (18). Additionally, a possible role of T follicular helper cells in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease is increasingly being reported (19–21). Other cell types implicated in AIH pathogenesis include γδT cells present in the liver and responsible for granzyme B and IFN-γ secretion (22), and macrophages (23). Loss of self-tolerance has also been implicated in AIH. Thus, defective immunoreguation in AIH results not only from reduced number and function of regulatory T cells (Tregs), but also from increased conversion of Tregs into effector cells (24–26). Current therapies in AIH interrupt the adaptive immune process globally but have a non-specific target (27); moreover, 10% - 40% of patients have to discontinue therapy due to side effects (27). This highlights the need for improved understanding of disease pathogenesis as this may allow immune-targeted treatments with greater efficacy and fewer associated adverse effects.

The term de novo autoimmune hepatitis (dnAIH) in the context of liver transplantation was first used in 1998 to describe a distinct form of graft dysfunction in pediatric liver transplant recipients that clinically and histologically resembled autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) but occurred in children who were transplanted for indications other than AIH (28). Thus, the classic features of AIH with elevation of liver enzymes, detectable autoantibodies, elevation of serum immunoglobulin G levels, and interface hepatitis with plasma cell infiltration in liver histology is observed in patients with dnAIH. The frequency of dnAIH has been estimated at 1.7% - 11% (28–38). It can be an aggressive disease in children as chronic rejection, cirrhosis, portal hypertension and subsequent graft loss and a need for re-transplantation occurred in long-term follow-up despite standard treatment (30, 34, 36, 38). The pathogenesis of post liver transplantation de novo autoimmunity, and in particular dnAIH remains to be elucidated. The pathogenic mechanisms responsible for AIH development before liver transplantation are probably similar to those that promote dnAIH, but the introduction of a donor graft with different antigen presenting cells and immune reactive cells may alter the recipients’ immune response (39). Further studies are therefore needed to determine if the dnAIH form of graft dysfunction represents an autoimmune or an alloimmune reaction. A better understanding of the immunological pathogenic mechanisms will further improve the diagnosis, management and patient outcomes of this challenging disorder.

Multiple human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) are distributed throughout the genome as DNA fossils from prior germline infection (40). Although they form ~8% of the human genome, HERVs usually lack function and expression because of restrictive epigenetic modifications or genetic mutations. However, HERVs may be expressed in pathological processes such as autoimmune diseases, cancers, and some viral infections activate HERV expression. Notably infection with cytomegalovirus (41), Epstein-Barr virus infection (42–44), Herpes Simplex (45, 46), Human Herpesvirus 6A (47), and Human Herpesvirus 6B (48) all activate HERV expression. These observations have led to the hypothesis that HERV may trigger autoimmune diseases through various effects of HERV-mediated superantigen expression and immune dysregulation (40, 49), however the exact role of HERV in triggering autoimmunity remains unclear.

Intracellular pathogens, particularly viruses can frequently hijack organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to facilitate survival and replication (50). Cellular defense mechanisms have consequently evolved to detect biological perturbations frequently associated with infection, such as a rapid increase in glycoprotein production, activating the unfolded protein response (UPR) (51). The unfolded protein response is a comprehensive, three-pronged system that corrects pathological protein misfolding and aggregation in the endoplasmic reticulum (50). To combat excessive accumulation of misfolded proteins, multicellular organisms mount a coordinated response driven primarily by three ER-localized transmembrane proteins: the dual kinase/endoribonuclease inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α/Ern1), the kinase PKR-like ER resident kinase (PERK/Eif2ak3), and activating transcription factor 6α (ATF6α/Atf6) (50). Virus-mediated UPR activation varies by strain. For instance, the African Swine fever virus and lymphochoriomeningitis virus (LCMV) solely activate the ATF6α branch (52, 53), whereas Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and herpes simplex virus 1 impact on all 3 UPR branches (54). Unremitting UPR activation may directly contribute to failures in immunological tolerance observed in inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis by dangerously lowering the threshold for proinflammatory signaling and cell death (50).

The objective of this study was to assess the role of HERV in altering the immune response and Treg function in autoimmune liver disease using blood and liver tissue obtained from children with dnAIH and AIH compared to children with normal graft function and healthy children. We observed increased protein levels of HERV1-env and HERV1-env antigenemia in Tregs and plasma, respectively, of patients with AIH and dnAIH (55). We therefore hypothesized that loss of immunological tolerance in dnAIH and AIH is initiated by HERV1-mediated UPR activation (56). Due to their role in maintaining tolerance to self-antigens and curbing autoimmunity, we chose to focus on regulatory T cells in this study. Here we show that HERV1-env, through its interaction with ATF6, induces Th17-Tregs and loss of Treg suppressor function. We also show that HERV1-env-expressing Tregs exhibit an enhanced expression of PD1 and LAG3. Thus, unremitting UPR activation induced by HERV1-env contributes to loss of immunological tolerance in autoimmune liver disease.

Methods

Biological samples and experimental outline.

This was a cross sectional study involving pediatric liver transplant recipients with a diagnosis of de novo autoimmune hepatitis (n=15) and pediatric liver transplant recipients without a diagnosis of de novo autoimmune hepatitis that had normal allograft function at the time of enrollment and blood draw. These latter subjects served as the liver transplant control group (LTC) (n=24). Other study cohorts included pediatric liver transplant recipients with acute cellular rejection (n=15) and healthy children who had no underlying immune mediated disorders and were not on any immunomodulatory agents. This latter group served as the healthy control group (HC) (n=17); Lastly, non-transplanted children with a diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis were also included (n=10). The transplanted subjects were enrolled as they attended their routine post-transplant clinics, the non-transplanted children with autoimmune hepatitis were enrolled as they attended their routine pediatric hepatology clinics, and the healthy non-transplanted subjects were enrolled using flyers posted in New Haven as well as from the help us discover database, a database of healthy children registered as research controls maintained by the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation (YCCI). The definition of de novo autoimmune hepatitis was as previously described: a liver transplant recipient without a history of autoimmune liver disease presenting with unknown etiology of late graft dysfunction. Late graft dysfunction characterized by elevated aminotransferases, and graft dysfunction not due to any of the following causes: acute and chronic rejection, hepatitis B and C infection, Epstein Barr virus and Cytomegalovirus infections, vascular problems, biliary complication, drug toxicity, sepsis, recurrence of primary disease, or post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease; elevated serum immunoglobulin G, positive autoantibody titers: ANA, ASMA, anti-LKM; characteristic biopsy findings of dense lymphocytic portal tract infiltrate with plasma cells, and interface hepatitis] (38). The definition of autoimmune hepatitis was as previously described (57, 58). The definition of acute cellular rejection was as previously described (59, 60).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria were established prospectively. The inclusion criteria for the liver transplant control group were: age ≤ 20-years, serum aminotransferases and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase ≤ ULN at blood draw, no past diagnosis of de novo autoimmune hepatitis, no biliary or vascular complication at time of blood draw, no past or present history of chronic rejection, and no recent acute rejection (> 1-year). The exclusion criteria included: age ≥ 21-years, biliary/vascular complication at time of blood draw, serum aminotransferases and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase > ULN at blood draw, recent acute rejection (≤ 1-year), and history of chronic rejection. We enrolled patients aged 0 through 20-years from January 2017 to December 2019. The rule for stopping patient enrollment and sample collection was determined by the dates as stated above. At enrollment, 30 ml of peripheral blood was obtained from each participant, and every three months over the duration of the study. If the study participant underwent a clinically indicated liver biopsy, liver tissue was obtained for isolation of RNA from formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue (FFPE). For the transplanted subjects with acute rejection, 30 ml of peripheral blood was obtained once a biopsy proven diagnosis of acute rejection was made, prior to commencement of treatment. Each experiment had two technical replicates with substantiation of the results. Informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians and assent was obtained as necessary per institutional review board guidelines.

Sample size: no sample size calculation was performed however we believe the sample size is adequate to measure the effect size given the highly significant differences demonstrated between the study groups.

Randomization: as these were in vitro experiments, randomization was not performed.

Blinding: lab personnel were blinded to the diagnostic category of the enrolled subjects for all experiments and data analyses in which subjects from the various diagnostic groups were used.

Replication: biological replicates were used in all experiments. Additionally, each experiment had two technical replicates.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yale University.

Cell isolation and FACS sorting of regulatory T cell, Th1, and Th17 populations.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from whole blood obtained from study participants by Ficoll Hypaque gradient centrifugation, for cell isolation and FACS sorting as previously described (61, 62). Tregs were defined as CD4+CD25hiCD127−. Th1 cells were defined as CD4+CXCR3+CCR4−CCR6− and Th17 cells defined as CD4+CXCR3−CCR4−CCR6+.

Treg stimulation and intracellular staining.

Tregs (50,000 cells) were stimulated with phobol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) at 50ng/ml and ionomycin (250ng/ml) and intracellular staining of cytokines and FOXP3 was performed as previously described (61).

Apoptosis / exhaustion experiments.

FACS-sorted memory Tregs from patients with dnAIH, AIH, and LTC were resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 1 X 106 cells/ml and subjected to culture in the presence of rIL-2, over 24–48-hours. Tregs were then washed twice with cold PBS and re-suspended in 1X binding buffer (BD Pharmingen, #556547) at a concentration of 1 X 106 cells/ml. 100 μl (1 X 105 cells) of re-suspended cells were transferred to a 5 ml V bottom tube, 5 μl of Annexin V and 1 μl of Sytox Blue (Thermo Fisher Scientific #S34857) [or 5 μl of Propidium Iodide (BD Pharmingen, # 556547)], and 1 μl each of anti-human LAG3 (Biolegend #369309), and PD1 antibody (Biolegend #367427) were added and incubated in the dark for 15-minutes at room temperature. Following incubation, 400 μl of 1X binding buffer were added and samples were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Suppression assays.

FACS sorted Tregs were first transduced with either scramble control particle or shRNA-HERV1-env particle, in the presence of rIL-2 for 24-hours, washed with media. Transduced Tregs were co-cultured with Cell Trace V450-labeled effector (responder) CD4+CD25−CD127+ T cells at Treg: responder ratio of 0:1, 0.5:1, 1:1 (i.e. 0 Tregs: 50,000 responders, 25,000 Tregs: 50,000 responders, 50,000 Tregs: 50,000 responders), and proliferation of viable responder T cells measured as previously described (61).

RNA Seq Quality Control.

Total RNA quality was determined by estimating the A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios by nanodrop. RNA integrity was determined by running an Agilent Bioanalyzer gel, which measured the percentage of RNA fragments greater than 200nt for each sample (also called DV200). RNA Seq Library Prep: Following the Illumina TruSeq RNA Exome protocol (Cat. No. RS-301-2001), samples were binned based on DV200 scores. High quality samples had a DV200 > 70%, medium quality samples had a DV200 of 50–70%, low quality samples had a DV200 of 30–50%, and samples with a DV200 < 30% were not used. The RNA was fragmented using divalent cations under elevated temperature at various time periods based on DV200. cDNA was generated from the cleaved RNA fragments using random priming during first and second strand synthesis. Then, sequencing adapters were ligated to the resulting double-stranded cDNA fragments. The coding regions of the transcriptome were captured from this library using sequence-specific probes to create the final library. Indexed libraries that meet appropriate cut-offs for both were quantified by qRT-PCR using a commercially available kit (KAPA Biosystems) and insert size distribution determined with the Perkin Elmer LabChip GX or Agilent Bioanalyzer. Samples with a yield of ≥0.5 ng/ul were used for sequencing.

Flow Cell Preparation and Sequencing.

Sample concentrations were normalized to 10 nM and loaded onto Illumina Rapid or High-output flow cells at a concentration that yielded 150–250 million passing filter clusters per lane. Samples were sequenced using 75bp paired-end sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 according to Illumina protocols. The 6bp index was read during an additional sequencing read that automatically followed the completion of read 1. Data generated during sequencing runs were simultaneously transferred to the YCGA high-performance computing cluster. A positive control (prepared bacteriophage Phi X library) provided by Illumina was spiked into every lane at a concentration of 0.3% to monitor sequencing quality in real time. Data Analysis and Storage: Signal intensities were converted to individual base calls during a run using the system’s Real Time Analysis (RTA) software. Base calls were transferred from the machine’s dedicated personal computer to the Yale High Performance Computing cluster via a 1 Gigabit network mount for downstream analysis. Primary analysis - sample de-multiplexing and alignment to the human genome - was performed using Illumina’s CASAVA 1.8.2 software suite. The data were returned to the user if the sample error rates was less than 2% and the distribution of reads per sample in a lane was within reasonable tolerance. Data were retained on the cluster for at least 6 months, and then transferred to a tape backup system.

RNA-Seq analysis.

The RNA-seq sequencing reads were first trimmed for quality, trimming to the last base with quality >= 20 and dropping any read pair where either of the trimmed reads was shorter than 45 bp. For messenger RNA analysis, the trimmed reads were aligned to the hg19 reference genome by TopHat2 (63–65) using the UCSC RefSeq GTF file for gene/transcript annotations. Transcript abundance calculation and differential gene expression analysis was performed using cuffdiff (66), identifying significantly differentially expressed genes between each pair of conditions. Those genes were given to the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (QIAGEN Inc., https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuitypathway-analysis) for pathway enrichment analysis.

For HERV RNA analysis, the trimmed reads were aligned to the hg38 reference genome by TopHat2, using the gEVE GTF file of 33,966 human HERV locations (67). Transcript abundance calculation and differential gene expression analysis was performed using cuffdiff, again identifying significant HERV expression differences between conditions.

Quantification of mRNA expression levels by RT-PCR.

RNA was isolated using Qiagen RNeasy Micro Kit (QIAGEN), following manufacturer’s guidelines, and converted to cDNA by reverse transcription (RT) as previously described (61, 62). For gene expression assays, Fast SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems #4309155) was used and the reactions were set up following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Values are presented as the variations in cycle threshold values normalized to the 18S ribosomal RNA gene or β-actin for each sample by using following formula: Relative RNA expression = (2−dCt)×1000. (Supp. Table 1 for primers used).

Isolation of RNA from Formalin Fixed Paraffin Embedded (FFPE) tissue: RNA was isolated from 1 – 3 FFPE curls using Beckman Coulter FormaPure Total kit (Part #: C16675), following the RNA isolation only method. RNA was eluted in 40μl Nuclease free water. Spectramax Nanodrop and Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100’s DV200 score assessed RNA quality and quantity.

Western Blotting.

Protein was harvested using MPER solution with PhosSTOP according to manufacturer’s instructions, and concentrations were measured using the Bradford method as previously described (62).

ELISA.

The protein concentration of ENV, HERV1_I was measured by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), using recombinant protein of ENV, HERV1_I (RKNKRNVFTQISTVENISTNIKKDIEIGSWKDKEWLPERIIKYYGPATWAQDRSWGYHTPIYMLNQIIRLQAVLEIIVNETA; Thermofisher custom design). Frozen plasma samples were thawed completely and centrifuged for 5 minutes prior to addition to the assay. Samples were run in triplicates. Briefly, each well was coated with 50μl of ENV, HERV1_I antibody (15μg/ml). Blocking of each well was then done using 150μl of blocking buffer (1%BSA, 1% sucrose in 1X PBS). 200μl of plasma from each study subject was then added and incubated for 2-hours. The second antibody of biotin labeled anti-HERV1_I was added to bind with the protein using the biotin protein labeling kit from Roche (# 11418165001). Substrate with 1:10000 HRP-Strepavidin (Invitrogen # 43-4323) was then added to the well and the plate read at 450/595 nm.

ChIP Analysis.

FACS sorted regulatory T cells obtained from PBMC’s were stimulated for 4 hours with a cocktail of PMA and ionomycin (00-4970-93, Invitrogen). The cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde, washed and lysed in the presence of protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Chromatin fragments were prepared by MNase digestion prior to immunoprecipitation using the Pierce Agarose ChIP Kit (26156, ThermoFisher Scientific) and the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, chromatin aliquots were incubated with 5 µg anti-ATF6α antibody, negative control IgG, or positive control anti-RNA Polymerase II Antibody and incubated overnight at 4°C under constant agitation. The next day, 20 μl of Protein A/G plus Agarose was added to each aliquot and incubated under constant agitation for 1 hour. After extensive washing, the DNA-protein-antibody complexes were eluted from the agarose beads with 150 μl of provided IP Elution Buffer (1X). All samples, including a total input, were incubated for 40 minutes at 65°C with shaking to revert cross-linking. After treatment with NaCl and Proteinase K, the immunoprecipitated DNA was recovered using a DNA Clean-Up column. The following ChIP-grade antibodies were used: anti-ATF6 (sc-166659, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–RNA Polymerase II Antibody (1862243, ThermoFisher Scientific), and negative control mouse IgG (10400C, ThermoFisher Scientific). Immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified for RORC and STAT3 promoter binding by qPCR (3 minutes at 95°C, 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds followed by 60°C for 1 minute) using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System and the iQ SYBR Green SuperMix (170-8880, Bio-Rad). Promoter binding sites that were upstream were identified. A melting curve analysis was performed to discriminate between specific and nonspecific PCR products. The relative amount of RORC and STAT3 promoter DNA was determined using the following primers: RORC forward

5’ -AGAACACCATCTCCAGCCTCA −3’; RORC reverse

5′- GAAGTCCTTAAATCCCAGCCAC −3′ and STAT3 forward

5-’ GCTCTCAACCTCGCCACC-3’; STAT3 reverse 5′-CGGAATGTCCTGCTGAAAAC −3′. Data were normalized by input control DNA and expressed with respect to those of control IgG (used as calibrator).

Co-Immunoprecipitation.

FACS sorted regulatory T cells obtained from PBMC’s, were stimulated for 4 hours with a cocktail of PMA and ionomycin (00-4970-93, Invitrogen). Cells were lysed in Pierce IP Lysis Buffer (87787, ThermoFisher Scientific) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors following the manufacturer’s protocol. Lysates were centrifuged and incubated with Protein G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (17-0618-01, GE Healthcare) and anti-ATF6 (sc-22799, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-HERV1 (sc-365885, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), negative control mouse IgG (10400C, ThermoFisher Scientific) or negative control rabbit IgG (1862244, ThermoFisher Scientific) overnight at 4°C shaking. The beads were washed with cold PBS 4 times and eluted with β-mercaptoethanol containing SDS sample buffer by boiling for 10 min. Protein samples were then loaded and subjected to Western Blot. The following antibodies were used: anti-ATF6 (sc-22799, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-HERV1 (sc-365885, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-GAPDH (sc-25778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Transduction.

Lentiviral particles expressing shRNA and overexpression particle were obtained from Origene (Rockville, MD) for env,HERV1_I. FACS sorted CD4+CD25hiCD127lo Tregs were subjected to transduction of non-adherent primary cells following the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, 5 X 104 Tregs were transduced with viral particles containing a vector expressing specific shRNA or a vector expressing unspecific shRNA. Transduction was carried out at a multiplicity of infection of 5 by centrifugation at 2250 rpm for 30-minutes at room temperature in the presence of 3 μg/ml polybrene (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Cells were subsequently cultured in Xvivo 15 media with anti-CD3, anti-CD28, both at 1 μg/ml, and IL-2 (50 U/ml), for 48-hours at 37°C, with 5% CO2. Cells were subsequently gently re-suspended, and RNA and protein harvested for qRT-PCR and Western Blot respectively.

Statistical analysis.

Patient characteristics were summarized using median and range for continuous variables, and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test was conducted to test group differences for continuous variables. Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact Test was conducted to test for associations between patient groups and categorical variables. Patients’ test results between scramble control and shRNA-HERV1-env, or control and over-expression samples were tested using Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test. Two-sided p value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Analysis carried out using SAS 9.4.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Demographics.

The clinical characteristics of patients with de novo autoimmune hepatitis (dnAIH), autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), and control populations are presented in Table 1. The duration from transplant and age at time of blood collection was not significantly different between the patients with de novo autoimmune hepatitis (dnAIH) and patients with normal graft function (LTC). Likewise, the age at time of blood collection was not significantly different between the patients with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and healthy children (HC). The male: female ratio for each cohort is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| dnAIH (n = 15) |

LTC (n = 24) |

AR (n = 15) |

AIH (n = 10) |

HC (n = 17) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender

M:F |

5:10 | 17:7 | 5:10 | 2:8 | 8:9 |

*0.029 $0.81 ^0.27 |

|

Age at blood draw (months)

Median (Range) |

178.8 (30.6 – 299.3) |

159.1 (58.6 – 215.4) |

22.8 (11.4 – 43.4) |

131.1 (78.6 – 195.0) |

117.0 (66.7 – 207.2) |

*0.47 ^0.5 $0.006 |

|

Duration from transplant at blood draw (months)

Median (Range) |

110.7 (21.1 – 226.4) |

131.3 (41.2 – 195.1) |

4.0 (1.2 – 36.2) |

n/a | n/a |

*0.43 $0.004 |

|

Age at transplant (months)

Median (Range) |

23.0 (7.0 – 209.8) |

11.9 (4.3 – 185.1) |

11.3 (6.5 – 195.0) |

n/a | n/a |

*0.15 $0.41 |

|

FK level at time of blood draw (ng/ml)

Median (Range) |

5.2 (3.8 – 11.6) |

2.5 (1.1 – 4.5) |

4.5 (0.6 – 8.7) |

n/a | n/a |

*<0.001 $0.67 |

|

Pre-transplant diagnosis

Biliary Atresia Malignancy Metabolic Other |

8 0 0 7 |

16 2 4 2 |

10 0 4 1 |

n/a | n/a |

*0.017 $0.014 |

dnAIH: de novo Autoimmune Hepatitis

LTC: liver transplanted control

AR: acute rejection

AIH: Autoimmune Hepatitis

HC: healthy children

dnAIH vs. LTC comparison

dnAIH vs. AR comparison

AIH vs. HC comparison

Increased HERV1-env expression in autoimmune liver disease Tregs, liver, and plasma.

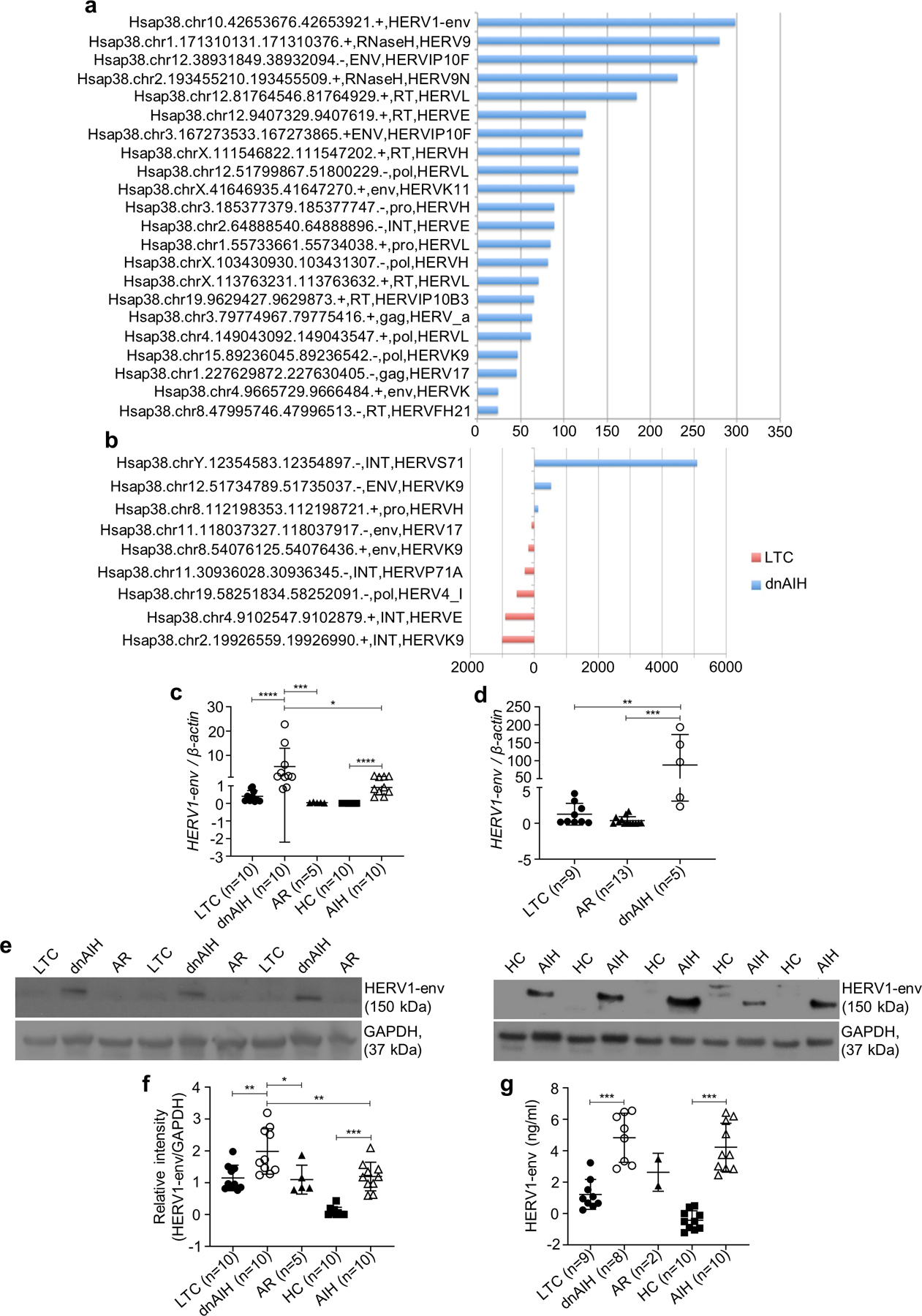

To evaluate the presence of and characterize the HERV loci in patients with autoimmune liver disease, we subjected FACS sorted Tregs from the blood, and formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) liver tissue, of patients with dnAIH and AIH to RNA-Sequencing (RNA-seq), confirmatory qRT-PCR and Western Blot. Plasma of patients with dnAIH and AIH was subjected to ELISA. RNA-Seq results showed an increased expression of HERV in Tregs of patients with dnAIH as compared to patients with normal liver graft function (Fig.1a). Furthermore, there were significant differences in the expression of HERV in the liver between these two groups of patients (Fig. 1b). The RNA-seq result was confirmed by qRT-PCR of both Tregs and liver (Figs. 1c–d). Based on the RNA data, we examined whether the increased expression of HERV1-env was leading to protein. Tregs of patients with dnAIH and AIH were therefore subjected to Western Blot. We observed increased HERV1-env levels in Tregs of patients with dnAIH and AIH compared to patients with normal liver graft function, and healthy children (Figs.1e–f). We also detected HERV1-env antigenemia in plasma of patients with dnAIH and AIH (Fig. 1g).

Fig. 1.

Up-regulation of human endogenous retrovirus in patients with autoimmune liver disease. RNA-Sequencing depicting up-regulation of HERV in peripheral blood memory Tregs (a) and liver (b) of patients with dnAIH (n=6) compared to patients with normal graft function (n=9). HERV expression FPKM values in Tregs (a) and liver (b) of patients with dnAIH, for HERV locations found to be significantly differentially expressed between patients with dnAIH vs. patients with normal graft function by a TopHat/CuffDiff analysis (using the gEVE database of human ERV elements(67)). At all locations, differentially expressed between the dnAIH and patients with normal graft function (LTC) sets of samples, no expression was found in the LTC sample, so N-fold were –inf or inf in all cases. Significant HERV1-env expression in peripheral blood memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH vs. patients with normal graft function (LTC) and patients with acute rejection is confirmed by qRT-PCR and shown in c. Significant HERV1-env expression in peripheral blood memory Tregs of patients with AIH vs. healthy children (HC) is shown in c. Significant HERV1-env expression in the liver of patients with dnAIH vs. patients with normal graft function (LTC) and patients with acute rejection is confirmed by qRT-PCR and shown in d. Significantly increased HERV1-env levels in peripheral blood memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH vs. patients with normal graft function (LTC), and patients with acute rejection; and of patients with AIH vs. healthy children (HC) is shown in (e, f). Significant HERV1-env antigenemia in patients with dnAIH vs. patients with normal graft function (LTC); and in patients with AIH vs. healthy children (HC) is shown in g. GAPDH used as an internal loading control in Western Blot experiments. PCR results are normalized to housekeeping gene, β-actin. Results are shown as individual dot plots with a line at median (c, d, f, g). ****p<0.0001 ***p<0.001 **p<0.01 *p<0.05.

Importantly, there was an absence of a similar increase of HERV1-env in patients with acute rejection. Together, these results show that HERV expression is increased in the liver, Tregs, and plasma of patients with dnAIH and AIH, and this increase is not a result of ongoing inflammation as we were unable to observe a similar increase of HERVs in patients with acute rejection – a disease process well known to be associated with inflammation both histologically and biochemically (68). Furthermore, CD69+ and CD69+HLA-DR+ expression was not different in Tregs of patients with AIH vs. healthy controls (data not shown), suggesting that HERV up-regulation in Tregs of patients with dnAIH and AIH is not a consequence of inflammation in the liver microenvironment.

HERV1-env induces ER stress and UPR activation.

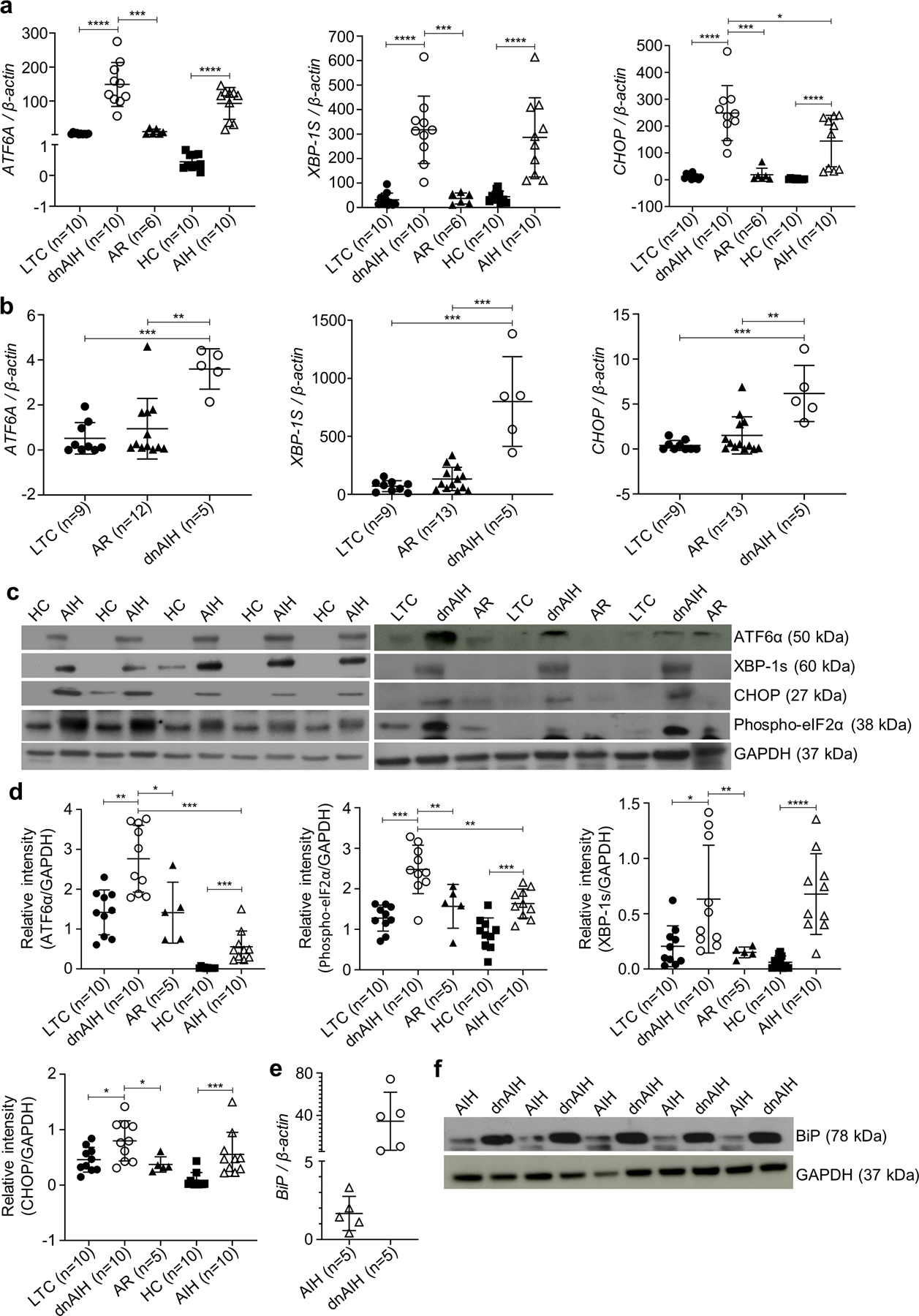

Our RNA-Seq results showed enrichment of ATF6 gene in peripheral blood memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH compared to patients with normal graft function (Supp Fig.1a). We examined FACS sorted memory Tregs from blood, and formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) liver tissue of patients with dnAIH and AIH for evidence of ER stress and UPR activation. Our results showed increased ATF6α, spliced X box protein (XBP1s), phosphorylated translation initiation factor (eIF2αp), and CHOP in Tregs and liver of patients with dnAIH and AIH compared to patients with normal graft function, and healthy children (Figs.2a–d). Under homeostatic conditions, the luminal domains of each of the ER-localized, transmembrane proteins are physically bound and held inactive by the chaperone protein, BiP (69, 70). However, BiP has a higher affinity for misfolded proteins than for UPR mediators, thus accumulation of misfolded substrates titrates away this steady-state inhibition. Release from BiP leads to activation of all three UPR branches (50). The activation of UPR branches leads to production of transcription factors, which up-regulate ER chaperones including BiP. Our results showed upregulation of BiP in patients with dnAIH and AIH (more so in patients with dnAIH than patients with AIH (Figs.2e–f). Together, these results confirm that ER stress and UPR activation occurs in autoimmune liver disease.

Fig. 2.

Effect of stressed memory Tregs and liver. Activation of unfolded protein response mediators in peripheral blood memory Tregs and liver of patients with autoimmune liver disease. Significant UPR activation (as evidenced by ATF6A, XBP-1S, and CHOP up-regulation) in peripheral blood memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH vs. patients with normal graft function (LTC) and patients with acute rejection is confirmed by qRT-PCR and shown in a. Similarly, significant UPR activation in peripheral blood memory Tregs of patients with AIH vs. healthy children (HC) also confirmed by qRT-PCR is shown in a. Significant UPR activation in liver of patients with dnAIH vs. patients with normal graft function (LTC) and patients with acute rejection is confirmed by qRT-PCR and shown in b. In separate experiments, protein was extracted from peripheral blood memory Tregs and used to study the three major UPR branches. Significantly increased levels of UPR mediators, specifically cleavage of ATF6α, phosphorylation of phospho-eIF2α, splicing of xbp1, and CHOP, in peripheral blood memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH vs. patients with normal graft function (LTC) and patients with acute rejection (AR); and of patients with AIH vs. healthy children (HC) is shown in (c, d). Representative blot of 3 separate experiments is shown (c). Dissociation of BiP from the ER localized, transmembrane proteins is shown in (e, f), further confirming ER stress with UPR activation in patients with autoimmune liver disease. GAPDH used as an internal loading control in Western Blot experiments. PCR results are normalized to housekeeping gene, β-actin. Results are shown as individual dot plots with a line at median (a, b, d, e). ****p<0.0001 ***p<0.001 **p<0.01 *p<0.05.

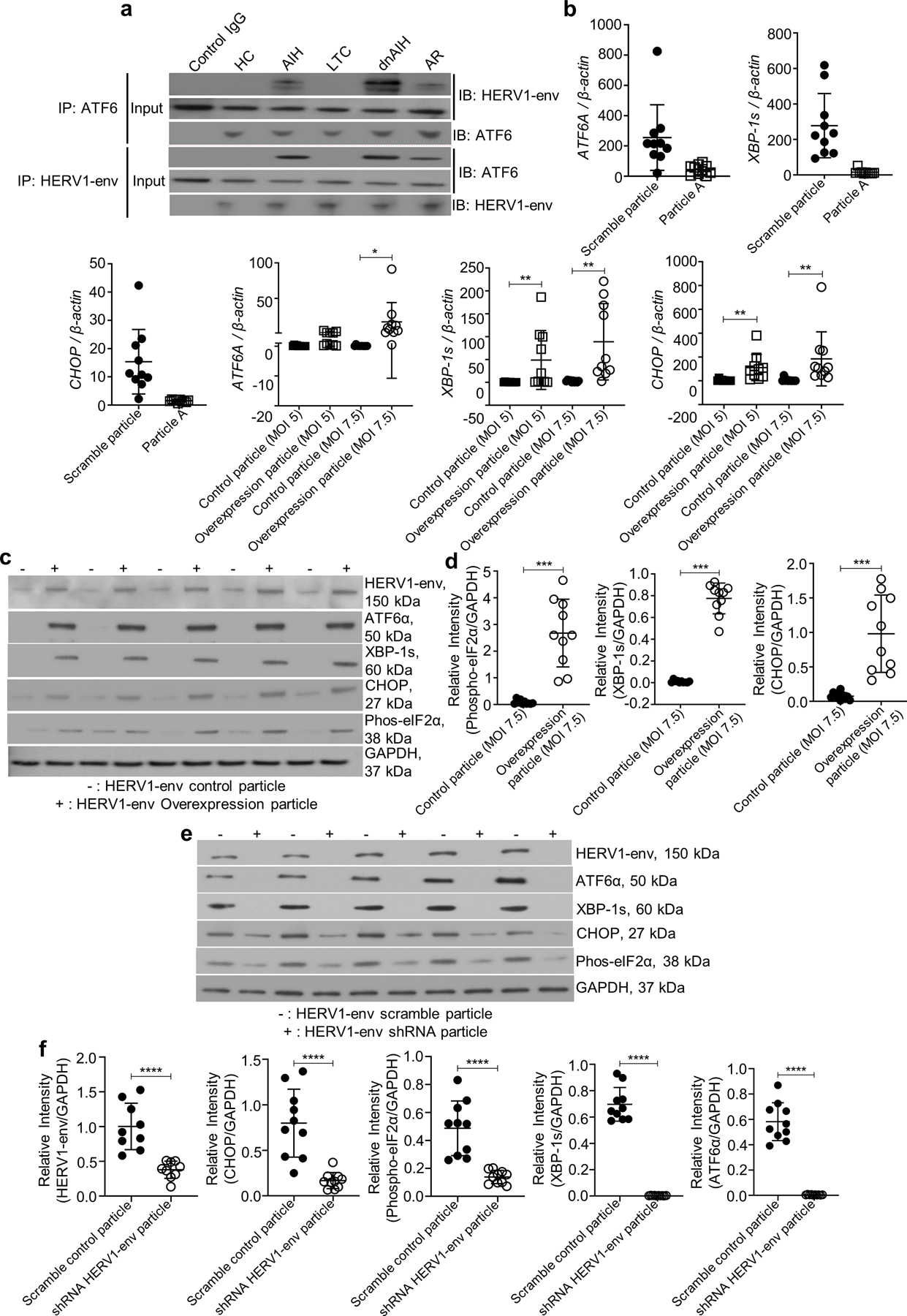

Previous studies have shown that activation of ATF6 can be triggered by over expression of a membrane protein (71), thus we asked whether ATF6 can be activated by HERV1-env. To test this, we first examined the interaction between HERV1-env and ATF6 in FACS-sorted memory Tregs (from blood of patients with dnAIH and AIH) using Co-ImmunoPrecipitation. Our results showed a protein interaction between ATF6 and HERV1-env (Fig.3a) in patients with dnAIH and AIH, and absence of a similar interaction in patients with normal graft function and healthy children, suggesting that ATF6 activation, and hence ER stress and UPR activation, is triggered by the envelope protein of HERV1. To confirm that the envelope protein of HERV1 is inducing ER stress, we used a targeted approach and overexpressed HERV1-env on FACS-sorted memory Tregs of healthy children with a lentiviral transduction system. We also silenced HERV1-env on FACS-sorted memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH by shRNA. The transduction efficiency of the overexpression and silencing experiments was determined at both mRNA (Supp. Fig. 1b) and protein level (Supp. Fig.1c) achieving > 50% knockdown of HERV1-env with shRNA-HERV1-env. Silencing of HERV1-env down-regulated ATF6A expression and UPR activation. HERV1-env overexpression up-regulated ATF6A expression and UPR activation (Figs.3b–f).

Fig. 3.

HERV1-env activates memory Treg ATF6α to induce UPR activation. a HERV1-env has a stronger interaction with ATF6α (and vice versa) in peripheral blood memory Tregs from patients with dnAIH and AIH, compared to memory Tregs of patients with normal graft function (LTC), patients with acute rejection (AR), and healthy children (HC). b illustrates the effect of HERV1-env silencing and overexpression in peripheral blood memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH (n=10) and healthy children (n=10) respectively at the mRNA level. Down regulation of ATF6A, and the mediators of UPR activation occurs in memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH following HERV1-env silencing and is shown in b. Up regulation of ATF6A, and the mediators of UPR activation occurs in memory Tregs of healthy children following lentiviral transduction of HERV1-env (MOI 7.5) and is shown in b. (c,d) illustrates the effect of HERV1-env overexpression in peripheral blood memory Tregs of healthy children at the protein level. Increased levels of ATF6α, and the mediators of UPR activation occur following lentiviral transduction of HERV1-env (MOI 7.5) and are shown in (c, d). (e, f) illustrates the effect of HERV1-env silencing in memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH at the protein level. Decreased levels of ATF6α, and the mediators of UPR activation occurs following HERV1-env silencing in memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH and is shown in (e, f). Representative immunoblot of 3 separate experiments is shown. GAPDH was used as an internal loading control for Western Blot experiments. PCR results are normalized to housekeeping gene, β-actin. Results are shown as individual dot plots with a line at median. ****p<0.0001 ***p<0.001 **p<0.01 *p<0.05.

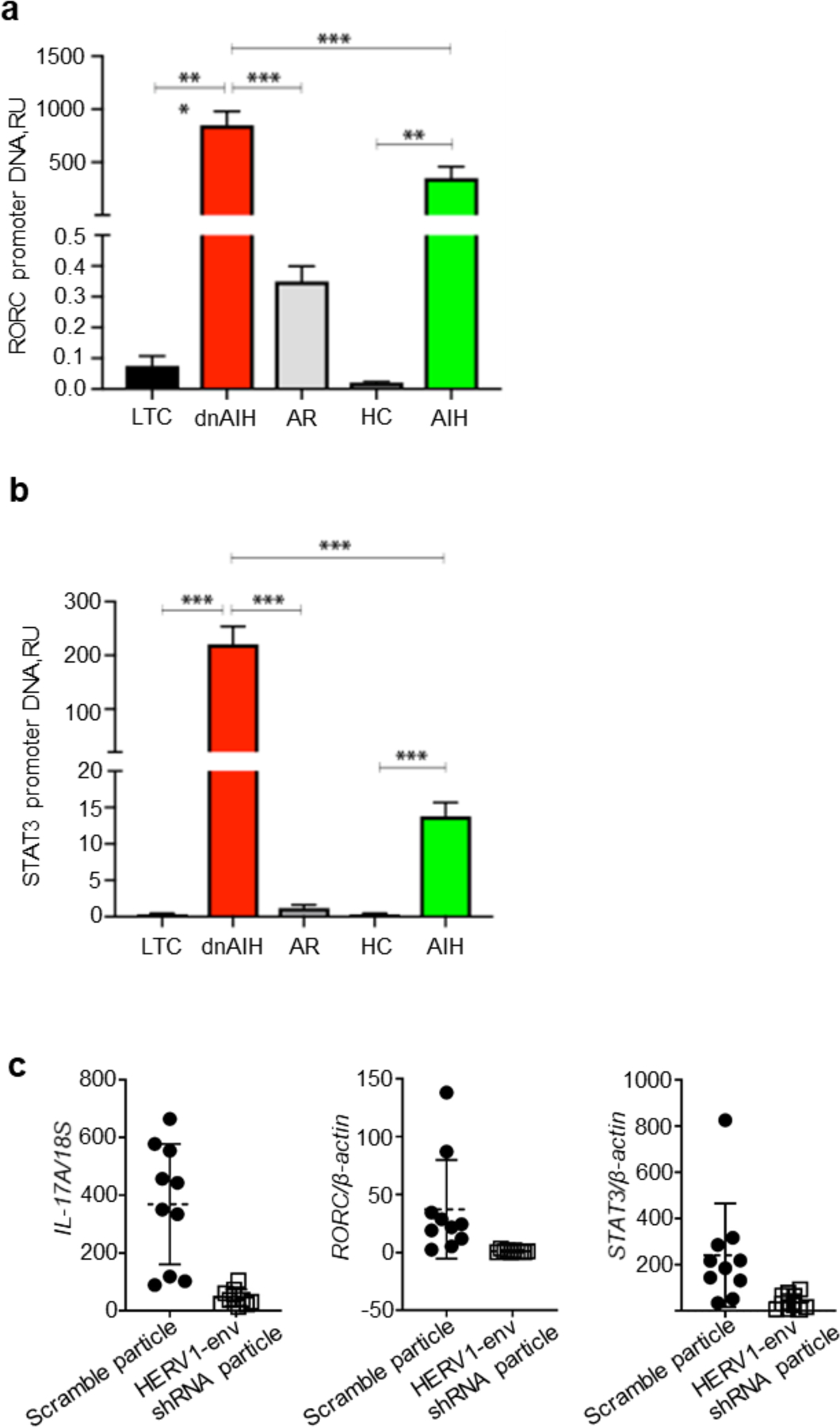

STAT3 and RORC are transcriptional targets of ATF6A and our RNA-seq analysis showed that they were significantly enriched in memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH (Supp Figs. 1d–e). Since STAT3 and RORC are transcription factors required for differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells to Th17 cells (72, 73), we asked whether ATF6 binds to STAT3 and RORC. To address this question, FACS sorted memory Tregs from patients with dnAIH and AIH were subjected to ChIP DNA qPCR. qPCR of ChIP DNA suggests strong binding of ATF6 to the transcription promoter regions of both RORC and STAT3 in patients with dnAIH and AIH (Figs.4a–b). Silencing of HERV1-env in memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH down-regulated IL-17A mRNA (Fig.4c). RORC and STAT3 mRNA were similarly down regulated. Together, these results suggest ATF6, by binding to the transcription promoter regions of known Th17 transcription factors, may drive Treg differentiation to Th17-like Tregs in patients with autoimmune liver disease.

Fig. 4.

Effect of memory Treg ER stress on adaptive immunity. ATF6 drives IL-17A transcription in peripheral blood memory Tregs. a-b. ChIP DNA qPCR confirms strong upstream binding of ATF6 to the transcription promoter regions of RORC and STAT3 in patients with dnAIH and AIH and is shown in a, b. Silencing of HERV1-env (which down-regulates ATF6α) abrogates IL-17A transcription in memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH (n=10) and is shown in c. PCR result is normalized to the housekeeping gene, 18S. Results are shown as individual dot plots with a line at median. ***p<0.001 **p<0.01 *p<0.05.

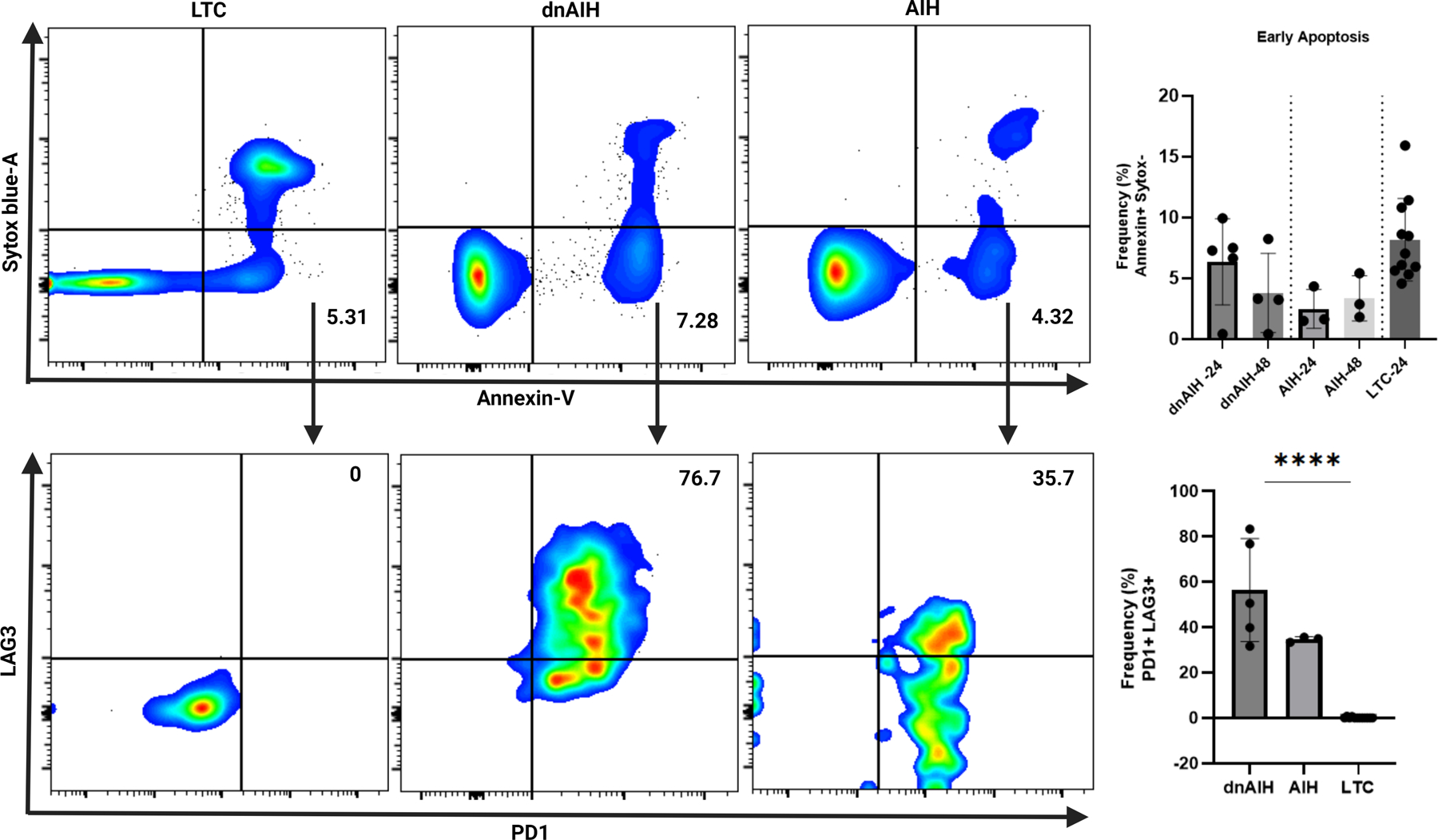

Unremitting UPR activation induces enhanced expression of PD1 and LAG3.

The two responses to ER stress are adaptation or apoptosis (50). To examine the effect of HERV1-env on viability of Tregs, FACS-sorted memory Tregs from patients with dnAIH, AIH, and LTC were subjected to culture, in the presence of rIL-2, for 24 and 48-hours. While memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH, AIH, and LTC patients similarly underwent early apoptosis, (ie. increased Annexin V uptake, without Sytox Blue uptake, Fig.5 upper panel), dnAIH and AIH Tregs undergoing early apoptosis displayed enhanced expression of PD1 and LAG3 when compared to LTC Tregs undergoing early apoptosis (Fig.5 lower panel). Gating strategy shown in Supp. Fig. 2a. HERV1-env silencing on Tregs of patients with dnAIH and AIH did not decrease the frequency of Treg cells undergoing early apoptosis and though Treg cell number showed a minimal increase, it did not achieve statistical significance (Supp. Fig. 2b). Together, these results indirectly suggest a possible relationship between HERV1-env and expression of immune checkpoints.

Fig. 5.

Memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH and AIH undergoing early apoptosis display enhanced expression of PD1 and LAG3. Peripheral blood memory Tregs from patients with dnAIH, AIH, and liver transplanted controls (LTC) cultured in the presence of rIL-2 for 24 and 48-hours. Cell viability monitored using Sytox Blue and Annexin V. Upper panel: Frequency of Tregs undergoing early apoptosis (ie. % Annexin V+ Sytox Blue− cells on FACS analysis) is similar between the 3 patient groups (LTC: 5.31%; dnAIH: 7.28%; AIH: 4.32%). Summary data shown for 24 and 48-hours. Results are shown as individual dot plots. Lower panel: dnAIH and AIH Tregs undergoing early apoptosis display enhanced PD1+LAG3+ expression on FACS analysis compared to LTC Tregs (LTC: 0%; dnAIH: 76.7%; AIH: 35.7%), suggesting a relationship between HERV1-env and expression of immune checkpoints. Summary data shown for 24-hours. Results are shown as individual dot plots. (dnAIH n=5; AIH n=3; LTC n=10). ****p<0.0001.

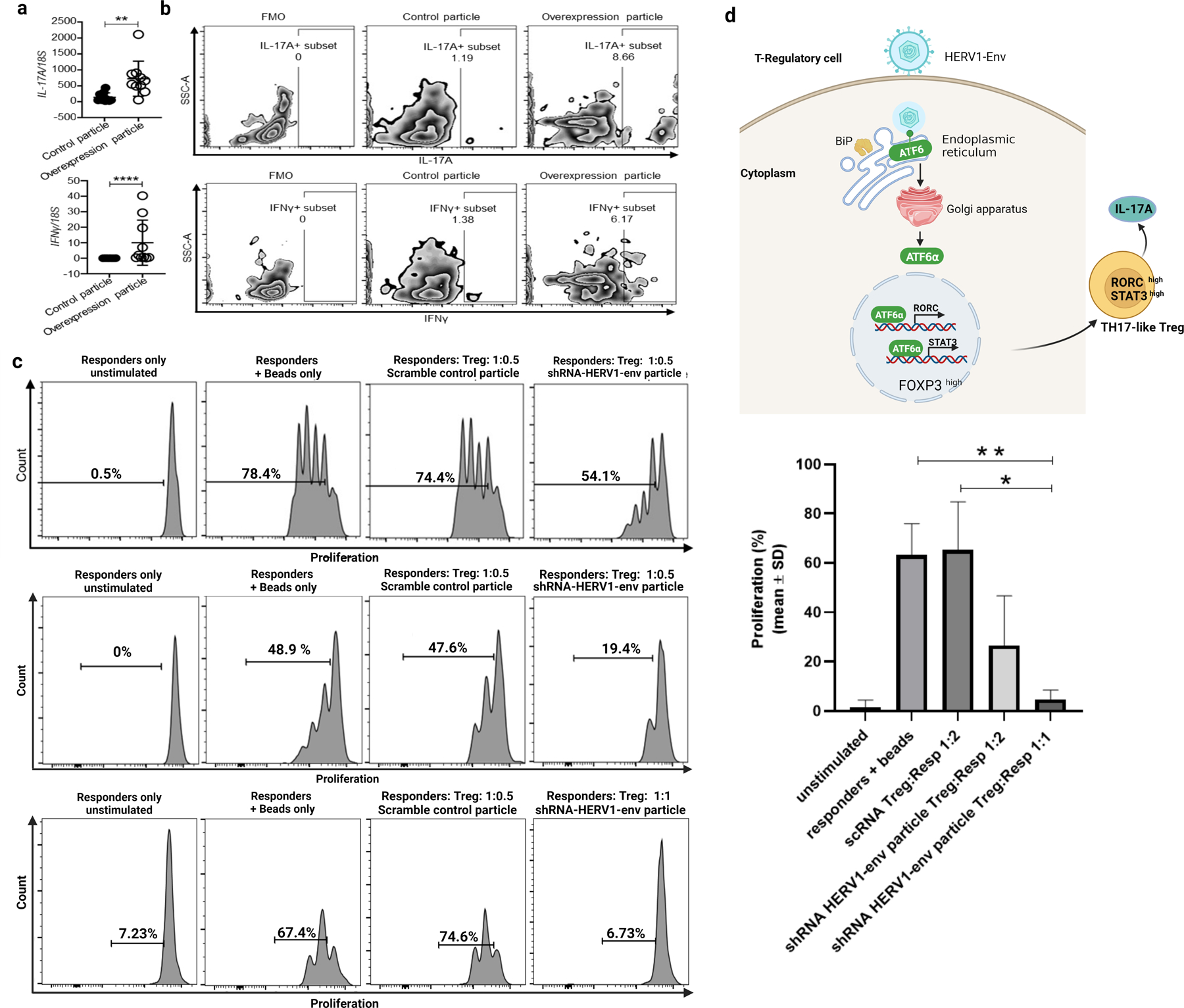

Silencing of HERV1-env leads to recovery of Treg suppressive function.

Tregs are not a terminally differentiated population but show some degree of plasticity, and can under specific environmental conditions acquire the phenotype of effector T cells (74). Knowing that a subset of human Tregs produce IFN-γ (75) or IL-17 (61) and thus share features of Th1 and Th17 effector cells, specifically, given our published observation of IL-17A and IFN-γ expression and production from Tregs of patients with dnAIH (61), we examined whether HERV1-env contributes to loss of immune tolerance by lowering the threshold for proinflammatory signaling in Tregs. FACS-sorted memory Tregs from healthy children were transduced with HERV1-env overexpression construct and IFN-γ and IL-17A gene and protein expression were measured by qRT-PCR and FACS respectively following stimulation with PMA/ionomycin. Successful transduction was confirmed by qRT-PCR and Western Blot (Supp. Figs. 1b–c). HERV1-env expressing Tregs have increased IFN-γ and IL-17A expression as compared to control particle (Fig.6a) and this was confirmed at protein level for IL-17A and IFN-γ (Fig.6b). (Gating Strategy shown in Supp. Fig. 2c). Importantly, these HERV1-env transduced Tregs maintained Foxp3 expression (data not shown). Moreover, HERV1-env transduced Tregs were indeed shown to demonstrate UPR activation (Figs.3b–d) similar to the observation in Tregs of patients with dnAIH and AIH (Figs. 2a, c–f).

Fig. 6.

Alteration of proinflammatory signaling and function in memory Tregs. a Up-regulation of IL-17A and IFN-γ mRNA in memory Tregs of healthy children (n=10) following HERV1-env lentiviral transduction. b Increased IL-17A and IFN-γ production from memory Tregs of healthy children following HERV1-env lentiviral transduction. (IL-17A: control particle 1.19%; overexpression particle 8.66%.). (IFN-γ: control particle 1.38%; overexpression particle 6.17%). PCR result is normalized to the housekeeping gene, 18S. Results are shown as individual dot plots with a line at median. c Tregs from dnAIH patients (transduced with either scramble control particle or shRNA-HERV1-env particle) were co-cultured in a 1:1 and 1:0.5 ratio with Cell Trace V450-labeled effector (responder) CD4+CD25−CD127+ T cells and proliferation of viable responder T cells measured. The stimulus used was Dynabeads anti-CD3, anti-CD28 beads. Three representative histograms are shown: (top panel): scramble control particle Treg: responder cells ratio 0.5:1. 74.4%; shRNA-HERV1-env particle Treg: responder cells ratio 0.5:1. 54.1%. (Middle panel): Scramble control particle Treg: responder cells ratio 0.5:1. 47.6%; shRNA-HERV1-env particle Treg: responder cells ratio 0.5:1. 19.4%. (Lower panel): Scramble control particle Treg: responder cells ratio 0.5:1. 67%; shRNA-HERV1-env particle Treg: responder cells ratio 1:1. 6.73%; Summary data for suppression assay shown (n=7). ****p<0.0001 **p<0.01 *p<0.05. d Schematic representation showing HERV1-env induced UPR activation leading to differentiation of memory Tregs to pro-inflammatory cytokine producing Tregs.

Silencing of HERV1-env on Tregs of patients with dnAIH, led to recovery of suppressive function of Tregs (Fig.6c). Together, this data suggests HERV1-env, by inducing unremitting UPR activation may contribute to failures in immunological tolerance by lowering the threshold for proinflammatory signaling in Tregs (Fig. 6d).

Lastly, given participation of Th1 and Th17 cells in liver injury in both AIH and dnAIH, we questioned if HERV1-env up-regulation and UPR activation is specific to Tregs. To address this, FACS sorted Th1 and Th17 cells from blood of children with dnAIH, AIH, acute rejection, liver transplanted children without dnAIH, and healthy children were subjected to qRT-PCR for HERV1-env expression and downstream mediators of UPR activation. Compared to HERV1-env expression in Tregs of patients with dnAIH, Th1 and Th17 cells of patients with dnAIH and AIH do not demonstrate significant HERV1-env expression (Supp. Fig. 3a), neither did they demonstrate significant ATF6A, CHOP, or XBP-1s (Supp. Fig. 3b) expression supporting HERV1 up-regulation being specific to Tregs in autoimmune liver disease.

Discussion

Here we confirm the previously reported involvement of HERVs in the pathogenesis of several autoimmune diseases (76–86), and extend it to the autoimmune liver diseases, dnAIH and AIH. Our data further suggest that ER stress occurs in Tregs and livers of patients with dnAIH and AIH. Here we show that memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH produce IL-17A and IFN-γ under ER stress induced by HERV1-env reactivation. Thus, HERV1-env-induced ER stress, mediated through ATF6α, drives Tregs to differentiate and acquire a Th1-like and Th17-like effector phenotype. Furthermore, silencing of HERV1-env in Tregs led to recovery of suppressive function of Tregs. Our data thus demonstrates another mechanism by which Tregs demonstrate plasticity and acquire effector-like properties.

We have previously shown that peripheral blood memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH produce IFN-γ and IL-17 (61). While the production of IFN-γ is driven in part by inflammsome activation of CD14+ monocytes (62), it does not explain the production of IL-17. Th17 cells contribute to autoimmunity by producing proinflammatory cytokines (including but not limited to IL-17) and inducing hepatocytes to secrete IL-6 (18), which further enhances Th17 cell activation. Our current work suggests that ATF6α by binding to the transcription promoter regions of RORC and STAT3 in peripheral blood memory Tregs drives differentiation of these Tregs to a Th17-like phenotype; Importantly, HERV1-env silencing down regulates ATF6A, and IL-17A expression and production. Similarly, HERV1-env overexpression drives differentiation of Tregs to Th1-like Tregs that produce IFN-γ. Exposure of hepatocytes to IFN-γ results in upregulation of MHC class I molecules and aberrant expression of MHC class II molecules, leading to further T cell activation and perpetuation of liver damage (13, 14); Moreover, IFN-γ also induces monocyte differentiation, promotes macrophage and immature dendritic cell activation (15), and contributes to increased natural killer cell activity (16). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of ATF6α driving Tregs to acquire a pro-inflammatory phenotype.

The development of autoimmune disease is enhanced by breakdown of self-tolerance mechanisms. Some published data indicate a functional defect in Tregs in AIH (87–89). Defective immune regulation in AIH also results from increased conversion of Tregs into effector cells (25). Our observation that upon silencing of HERV1-env, Treg suppressive function is restored is important as it confirms that unremitting UPR activation may alter tolerance thresholds by promoting excessive proinflammatory signaling or stress-mediated exposure of novel immunogenic or misfolded autoantigens (90). Unraveling how ER stress alters the threshold for proinflammatory signaling may help explain how genetic susceptibilities in patients with autoimmune disease, collaborate with environmental stimuli to corrupt homeostatic tolerance mechanisms (50).

Env-HERV1 expressing memory Tregs of patients with dnAIH and AIH also exhibited enhanced expression of PD1 and LAG3. Ma et al have reported on ER stress induced by cholesterol through XBP1, resulting in PD1 expression and exhaustion in CD8 tumor infiltrating T cells (91). Our results show activation of the three major UPR branches including XBP1 in dnAIH and AIH; moreover, env-HERV1 overexpression upregulated XBP1s while env-HERV1 knockdown downregulated XBP1s. It is thus possible that env-HERV1 induces XBP1 expression which then regulates the expression of PD-1 on memory Tregs. This would have to be further investigated and exceeds the scope of this paper.

While Epstein Barr Virus has been reported to activate HERVs (42–44), the amount of EBV DNA was not increased in plasma of these patients suggesting to us that EBV was not an issue here. Interestingly, while a similar level of env-HERV1 antigenemia was observed in subjects with dnAIH and AIH (Fig. 1G), env-HERV1 expression/level in Tregs was higher in subjects with dnAIH than those with AIH (Figs. 1C, 1F). One could argue that if env-HERV1 activation is a result of an exogenous viral infection, then the effects of such a viral infection may be enhanced in subjects on immunosuppression though this would not explain the higher env-HERV1 expression/level in Tregs of subjects with dnAIH compared to AIH.

A critical question that arises is why env-HERV1 expression and the subsequent ATF6 interaction, UPR activation, and all the downstream molecular and functional consequences are restricted to Tregs and exclude conventional T cells; we have documented the absence of env-HERV1 expression in Th1 and Th17 cells from patients with AIH and dnAIH (Supp. Fig. 3a) and shown diminished UPR responses in Th1 and Th17 cells (Supp. Fig. 3b). While the trigger(s) of HERV expression in AIH and dnAIH are not known, others have reported activation of HERV may lead to differential responses in Tregs versus conventional T cells during chronic viral herpes virus infection (92).

Lastly, in genetically modified models and immunodeficiency syndromes linked with autoimmune disease, loss of Treg homeostasis may result in prolonged inflammatory responses (93); while env-HERV1 induced UPR activation may well contribute to both neoantigen formation and apoptosis in Tregs, this was not studied in our present submission.

Taken together, our results shed light on the events that trigger proinflammatory cytokine production by memory Tregs and uncover HERV1-env induced ER stress as a central player in the initiation of this process. Upon ER stress, ATF6α through its binding affinity to Th17 transcription factors induces IL-17A up-regulation and production from Tregs; coupled with loss of Treg suppressor function. Furthermore, env-HERV1 expressing Tregs undergo apoptosis and exhibit enhanced expression of PD1 and LAG3. These results highlight the key role of HERV1-env in contributing to autoimmunity and identify its envelope protein as a target to treat dnAIH and AIH by acting at the early steps in the differentiation and destruction of Tregs.

Limitations of study

While our findings demonstrate that HERV1-env induced Treg dysfunction, this work does have some limitations. ER stress was induced by HERV1-env but what triggers HERV1-env activation is unclear. HERV1-env-expressing Tregs had upregulated immune checkpoint expression but how HERV1-env induces enhanced PD1 and LAG3 expression is unclear. The detailed transcriptional program of XBP-1 related to Treg exhaustion in autoimmune liver disease should be investigated but is beyond the scope of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

The liver microenvironment in AIH and dnAIH is enriched with HERV1-env.

HERV1-env induced loss of Treg suppressor function in dnAIH.

Our results reveal a novel mechanism by which HERV1-env induces Treg dysfunction.

Footnotes

UDECTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000142 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health.

UDENational Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30KD034989.

References

- 1.Manns MP, Lohse AW, and Vergani D. 2015. Autoimmune hepatitis--Update 2015. J Hepatol 62: S100–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golbabapour S, Bagheri-Lankarani K, Ghavami S, and Geramizadeh B. 2019. Autoimmune Hepatitis and Stellate Cells; an Insight into the Role of Autophagy. Curr Med Chem [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Deneau M, Jensen MK, Holmen J, Williams MS, Book LS, and Guthery SL. 2013. Primary sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and overlap in Utah children: epidemiology and natural history. Hepatology 58: 1392–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boberg KM, Aadland E, Jahnsen J, Raknerud N, Stiris M, and Bell H. 1998. Incidence and prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis in a Norwegian population. Scand J Gastroenterol 33: 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delgado JS, Vodonos A, Malnick S, Kriger O, Wilkof-Segev R, Delgado B, Novack V, Rosenthal A, Menachem Y, Melzer E, and Fich A. 2013. Autoimmune hepatitis in southern Israel: a 15-year multicenter study. J Dig Dis 14: 611–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feld JJ, and Heathcote EJ. 2003. Epidemiology of autoimmune liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 18: 1118–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ngu JH, Bechly K, Chapman BA, Burt MJ, Barclay ML, Gearry RB, and Stedman CA. 2010. Population-based epidemiology study of autoimmune hepatitis: a disease of older women? J Gastroenterol Hepatol 25: 1681–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Gerven NM, Verwer BJ, Witte BI, van Erpecum KJ, van Buuren HR, Maijers I, Visscher AP, Verschuren EC, van Hoek B, Coenraad MJ, Beuers UH, de Man RA, Drenth JP, den Ouden JW, Verdonk RC, Koek GH, Brouwer JT, Guichelaar MM, Vrolijk JM, Mulder CJ, van Nieuwkerk CM, Bouma G, and S. g. Dutch Autoimmune hepatitis. 2014. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of autoimmune hepatitis in the Netherlands. Scand J Gastroenterol 49: 1245–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werner M, Prytz H, Ohlsson B, Almer S, Bjornsson E, Bergquist A, Wallerstedt S, Sandberg-Gertzen H, Hultcrantz R, Sangfelt P, Weiland O, and Danielsson A. 2008. Epidemiology and the initial presentation of autoimmune hepatitis in Sweden: a nationwide study. Scand J Gastroenterol 43: 1232–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harada K, Hiep NC, and Ohira H. 2017. Challenges and difficulties in pathological diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatol Res 47: 963–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyson JK, De Martin E, Dalekos GN, Drenth JPH, Herkel J, Hubscher SG, Kelly D, Lenzi M, Milkiewicz P, Oo YH, Heneghan MA, Lohse AW, and Consortium I. 2019. Review article: unanswered clinical and research questions in autoimmune hepatitis-conclusions of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Research Workshop. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 49: 528–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ichiki Y, Aoki CA, Bowlus CL, Shimoda S, Ishibashi H, and Gershwin ME. 2005. T cell immunity in autoimmune hepatitis. Autoimmun Rev 4: 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lobo-Yeo A, Senaldi G, Portmann B, Mowat AP, Mieli-Vergani G, and Vergani D. 1990. Class I and class II major histocompatibility complex antigen expression on hepatocytes: a study in children with liver disease. Hepatology 12: 224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senaldi G, Lobo-Yeo A, Mowat AP, Mieli-Vergani G, and Vergani D. 1991. Class I and class II major histocompatibility complex antigens on hepatocytes: importance of the method of detection and expression in histologically normal and diseased livers. J Clin Pathol 44: 107–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delneste Y, Charbonnier P, Herbault N, Magistrelli G, Caron G, Bonnefoy JY, and Jeannin P. 2003. Interferon-gamma switches monocyte differentiation from dendritic cells to macrophages. Blood 101: 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, and Hume DA. 2004. Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol 75: 163–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liberal R, Krawitt EL, Vierling JM, Manns MP, Mieli-Vergani G, and Vergani D. 2016. Cutting edge issues in autoimmune hepatitis. J Autoimmun 75: 6–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao L, Tang Y, You Z, Wang Q, Liang S, Han X, Qiu D, Wei J, Liu Y, Shen L, Chen X, Peng Y, Li Z, and Ma X. 2011. Interleukin-17 contributes to the pathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis through inducing hepatic interleukin-6 expression. PLoS One 6: e18909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma CS, and Deenick EK. 2014. Human T follicular helper (Tfh) cells and disease. Immunol Cell Biol 92: 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abe K, Takahashi A, Imaizumi H, Hayashi M, Okai K, Kanno Y, Watanabe H, and Ohira H. 2016. Interleukin-21 plays a critical role in the pathogenesis and severity of type I autoimmune hepatitis. Springerplus 5: 777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura N, Yamagiwa S, Sugano T, Setsu T, Tominaga K, Kamimura H, Takamura M, and Terai S. 2018. Possible involvement of chemokine C-C receptor 7(−) programmed cell death-1(+) follicular helper T-cell subset in the pathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 33: 298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wen L, Peakman M, Mieli-Vergani G, and Vergani D. 1992. Elevation of activated gamma delta T cell receptor bearing T lymphocytes in patients with autoimmune chronic liver disease. Clin Exp Immunol 89: 78–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gronbaek H, Kreutzfeldt M, Kazankov K, Jessen N, Sandahl T, Hamilton-Dutoit S, Vilstrup H, and J. M. H. 2016. Single-centre experience of the macrophage activation marker soluble (s)CD163 - associations with disease activity and treatment response in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 44: 1062–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liberal R, Grant CR, Holder BS, Cardone J, Martinez-Llordella M, Ma Y, Heneghan MA, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, and Longhi MS. 2015. In autoimmune hepatitis type 1 or the autoimmune hepatitis-sclerosing cholangitis variant defective regulatory T-cell responsiveness to IL-2 results in low IL-10 production and impaired suppression. Hepatology 62: 863–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant CR, Liberal R, Holder BS, Cardone J, Ma Y, Robson SC, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, and Longhi MS. 2014. Dysfunctional CD39(POS) regulatory T cells and aberrant control of T-helper type 17 cells in autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 59: 1007–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Czaja AJ, Manns MP, Krawitt EL, Vierling JM, Lohse AW, and Montano-Loza AJ. 2018. Autoimmune hepatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 4: 18017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG, and Williams R. 1995. Azathioprine for long-term maintenance of remission in autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med 333: 958–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerkar N, Hadzic N, Davies ET, Portmann B, Donaldson PT, Rela M, Heaton ND, Vergani D, and Mieli-Vergani G. 1998. De-novo autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation. Lancet 351: 409–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernandez HM, Kovarik P, Whitington PF, and Alonso EM. 2001. Autoimmune hepatitis as a late complication of liver transplantation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 32: 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta P, Hart J, Millis JM, Cronin D, and Brady L. 2001. De novo hepatitis with autoimmune antibodies and atypical histology: a rare cause of late graft dysfunction after pediatric liver transplantation. Transplantation 71: 664–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andries S, Casamayou L, Sempoux C, Burlet M, Reding R, Bernard Otte J, Buts JP, and Sokal E. 2001. Posttransplant immune hepatitis in pediatric liver transplant recipients: incidence and maintenance therapy with azathioprine. Transplantation 72: 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spada M, Bertani A, Sonzogni A, Petz W, Riva S, Torre G, Melzi ML, Alberti D, Colledan M, Segalin A, Lucianetti A, and Gridelli B. 2001. A cause of late graft dysfunction after liver transplantation in children: de-novo autoimmune hepatitis. Transplant Proc 33: 1747–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petz W, Sonzogni A, Bertani A, Spada M, Lucianetti A, Colledan M, and Gridelli B. 2002. A cause of late graft dysfunction after pediatric liver transplantation: de novo autoimmune hepatitis. Transplant Proc 34: 1958–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyagawa-Hayashino A, Haga H, Egawa H, Hayashino Y, Sakurai T, Minamiguchi S, Tanaka K, and Manabe T. 2004. Outcome and risk factors of de novo autoimmune hepatitis in living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation 78: 128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibelli NE, Tannuri U, Mello ES, Cancado ER, Santos MM, Ayoub AA, Maksoud-Filho JG, Velhote MC, Silva MM, Pinho-Apezzato ML, and Maksoud JG. 2006. Successful treatment of de novo autoimmune hepatitis and cirrhosis after pediatric liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant 10: 371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venick RS, McDiarmid SV, Farmer DG, Gornbein J, Martin MG, Vargas JH, Ament ME, and Busuttil RW. 2007. Rejection and steroid dependence: unique risk factors in the development of pediatric posttransplant de novo autoimmune hepatitis. Am J Transplant 7: 955–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho JM, Kim KM, Oh SH, Lee YJ, Rhee KW, and Yu E. 2011. De novo autoimmune hepatitis in Korean children after liver transplantation: a single institution’s experience. Transplant Proc 43: 2394–2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ekong UD, McKiernan P, Martinez M, Lobritto S, Kelly D, Ng VL, Alonso EM, and Avitzur Y. 2017. Long-term outcomes of de novo autoimmune hepatitis in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Stirnimann G, Ebadi M, Czaja AJ, and Montano-Loza AJ. 2019. Recurrent and De Novo Autoimmune Hepatitis. Liver Transpl 25: 152–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Groger V, and Cynis H. 2018. Human Endogenous Retroviruses and Their Putative Role in the Development of Autoimmune Disorders Such as Multiple Sclerosis. Front Microbiol 9: 265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Assinger A, Yaiw KC, Gottesdorfer I, Leib-Mosch C, and Soderberg-Naucler C. 2013. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) induces human endogenous retrovirus (HERV) transcription. Retrovirology 10: 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsiao FC, Lin M, Tai A, Chen G, and Huber BT. 2006. Cutting edge: Epstein-Barr virus transactivates the HERV-K18 superantigen by docking to the human complement receptor 2 (CD21) on primary B cells. Journal of immunology 177: 2056–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sutkowski N, Chen G, Calderon G, and Huber BT. 2004. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein LMP-2A is sufficient for transactivation of the human endogenous retrovirus HERV-K18 superantigen. J Virol 78: 7852–7860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutkowski N, Conrad B, Thorley-Lawson DA, and Huber BT. 2001. Epstein-Barr virus transactivates the human endogenous retrovirus HERV-K18 that encodes a superantigen. Immunity 15: 579–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruprecht K, Obojes K, Wengel V, Gronen F, Kim KS, Perron H, Schneider-Schaulies J, and Rieckmann P. 2006. Regulation of human endogenous retrovirus W protein expression by herpes simplex virus type 1: implications for multiple sclerosis. J Neurovirol 12: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwun HJ, Han HJ, Lee WJ, Kim HS, and Jang KL. 2002. Transactivation of the human endogenous retrovirus K long terminal repeat by herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate early protein 0. Virus Res 86: 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tai AK, Luka J, Ablashi D, and Huber BT. 2009. HHV-6A infection induces expression of HERV-K18-encoded superantigen. J Clin Virol 46: 47–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turcanova VL, Bundgaard B, and Hollsberg P. 2009. Human herpesvirus-6B induces expression of the human endogenous retrovirus K18-encoded superantigen. J Clin Virol 46: 15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grandi N, and Tramontano E. 2018. HERV Envelope Proteins: Physiological Role and Pathogenic Potential in Cancer and Autoimmunity. Front Microbiol 9: 462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bettigole SE, and Glimcher LH. 2015. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 33: 107–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liberman E, Fong YL, Selby MJ, Choo QL, Cousens L, Houghton M, and Yen TS. 1999. Activation of the grp78 and grp94 promoters by hepatitis C virus E2 envelope protein. J Virol 73: 3718–3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Galindo I, Hernaez B, Munoz-Moreno R, Cuesta-Geijo MA, Dalmau-Mena I, and Alonso C. 2012. The ATF6 branch of unfolded protein response and apoptosis are activated to promote African swine fever virus infection. Cell Death Dis 3: e341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pasqual G, Burri DJ, Pasquato A, de la Torre JC, and Kunz S. 2011. Role of the host cell’s unfolded protein response in arenavirus infection. J Virol 85: 1662–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnston BP, and McCormick C. 2019. Herpesviruses and the Unfolded Protein Response. Viruses 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yao JL, Arterbery A, Avitzur A, Lobritto Y, Martinez S, Ekong M, U. 2019. Treg Plasticity is Induced by ENV,HERV1_I and UPR Activationin De Novo Autoimmune Hepatitis. In Am J Transplant

- 56.Li Y, Xia Y, Cheng X, Kleiner DE, Hewitt SM, Sproch J, Li T, Zhuang H, and Liang TJ. 2019. Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Activates Unfolded Protein Response in Forming Ground Glass Hepatocytes of Chronic Hepatitis B. Viruses 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Pares A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Boberg KM, Hofer H, Bianchi FB, Shibata M, Schramm C, Eisenmann de Torres B, Galle PR, McFarlane I, Dienes HP, Lohse AW, and International Autoimmune Hepatitis G. 2008. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 48: 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mieli-Vergani G, Heller S, Jara P, Vergani D, Chang MH, Fujisawa T, Gonzalez-Peralta RP, Kelly D, Mohan N, Shah U, and Murray KF. 2009. Autoimmune hepatitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 49: 158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.1997. Banff schema for grading liver allograft rejection: an international consensus document. Hepatology 25: 658–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Demetris AJ, Bellamy C, Hubscher SG, O’Leary J, Randhawa PS, Feng S, Neil D, Colvin RB, McCaughan G, Fung JJ, Del Bello A, Reinholt FP, Haga H, Adeyi O, Czaja AJ, Schiano T, Fiel MI, Smith ML, Sebagh M, Tanigawa RY, Yilmaz F, Alexander G, Baiocchi L, Balasubramanian M, Batal I, Bhan AK, Bucuvalas J, Cerski CT, Charlotte F, de Vera ME, ElMonayeri M, Fontes P, Furth EE, Gouw AS, Hafezi-Bakhtiari S, Hart J, Honsova E, Ismail W, Itoh T, Jhala NC, Khettry U, Klintmalm GB, Knechtle S, Koshiba T, Kozlowski T, Lassman CR, Lerut J, Levitsky J, Licini L, Liotta R, Mazariegos G, Minervini MI, Misdraji J, Mohanakumar T, Molne J, Nasser I, Neuberger J, O’Neil M, Pappo O, Petrovic L, Ruiz P, Sagol O, Sanchez Fueyo A, Sasatomi E, Shaked A, Shiller M, Shimizu T, Sis B, Sonzogni A, Stevenson HL, Thung SN, Tisone G, Tsamandas AC, Wernerson A, Wu T, Zeevi A, and Zen Y. 2016. 2016 Comprehensive Update of the Banff Working Group on Liver Allograft Pathology: Introduction of Antibody-Mediated Rejection. Am J Transplant [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Arterbery A O-AA, Avitzur Y, Ciarleglio M, Deng Y, Lobritto S, Martinez M, Hafler D, Kleinewietfeld M, Ekong UD. 2016. Production of Proinflammatory Cytokines by Monocytes in Liver-Transplanted Recipients with De Novo Autoimmune Hepatitis Is Enhanced and Induces TH1-like Regulatory T Cells. Journal of immunology 196: 4040–4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arterbery AS, Yao J, Ling A, Avitzur Y, Martinez M, Lobritto S, Deng Y, Geliang G, Mehta S, Wang G, Knight J, and Ekong UD. 2018. Inflammasome Priming Mediated via Toll-Like Receptors 2 and 4, Induces Th1-Like Regulatory T Cells in De Novo Autoimmune Hepatitis. Front Immunol 9: 1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trapnell C, Pachter L, and Salzberg SL 2009. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq Oxford. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, and Pachter L. 2012. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc 7: 562–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trapnell C, Pachter L, and Salzberg SL. 2009. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 25: 1105–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trapnell C, Hendrickson DG, Sauvageau M, Goff L, Rinn JL, and Pachter L. 2013. Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat Biotechnol 31: 46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakagawa S, and Takahashi MU. 2016. gEVE: a genome-based endogenous viral element database provides comprehensive viral protein-coding sequences in mammalian genomes. Database (Oxford) 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Demetris A, Adams D, Bellamy C, Blakolmer K, Clouston A, Dhillon AP, Fung J, Gouw A, Gustafsson B, Haga H, Harrison D, Hart J, Hubscher S, Jaffe R, Khettry U, Lassman C, Lewin K, Martinez O, Nakazawa Y, Neil D, Pappo O, Parizhskaya M, Randhawa P, Rasoul-Rockenschaub S, Reinholt F, Reynes M, Robert M, Tsamandas A, Wanless I, Wiesner R, Wernerson A, Wrba F, Wyatt J, and Yamabe H. 2000. Update of the International Banff Schema for Liver Allograft Rejection: working recommendations for the histopathologic staging and reporting of chronic rejection. An International Panel. Hepatology 31: 792–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ye J, Rawson RB, Komuro R, Chen X, Dave UP, Prywes R, Brown MS, and Goldstein JL. 2000. ER stress induces cleavage of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs. Mol Cell 6: 1355–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Hendershot LM, Harding HP, and Ron D. 2000. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat Cell Biol 2: 326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maiuolo J, Bulotta S, Verderio C, Benfante R, and Borgese N. 2011. Selective activation of the transcription factor ATF6 mediates endoplasmic reticulum proliferation triggered by a membrane protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 7832–7837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang XO, Panopoulos AD, Nurieva R, Chang SH, Wang D, Watowich SS, and Dong C. 2007. STAT3 regulates cytokine-mediated generation of inflammatory helper T cells. J Biol Chem 282: 9358–9363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang XO, Pappu BP, Nurieva R, Akimzhanov A, Kang HS, Chung Y, Ma L, Shah B, Panopoulos AD, Schluns KS, Watowich SS, Tian Q, Jetten AM, and Dong C. 2008. T helper 17 lineage differentiation is programmed by orphan nuclear receptors ROR alpha and ROR gamma. Immunity 28: 29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kitz A, and Dominguez-Villar M. 2017. Molecular mechanisms underlying Th1-like Treg generation and function. Cell Mol Life Sci 74: 4059–4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dominguez-Villar M, Baecher-Allan CM, and Hafler DA. 2011. Identification of T helper type 1-like, Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in human autoimmune disease. Nat Med 17: 673–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tugnet N, Rylance P, Roden D, Trela M, and Nelson P. 2013. Human Endogenous Retroviruses (HERVs) and Autoimmune Rheumatic Disease: Is There a Link? Open Rheumatol J 7: 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rucheton M, Graafland H, Fanton H, Ursule L, Ferrier P, and Larsen CJ. 1985. Presence of circulating antibodies against gag-gene MuLV proteins in patients with autoimmune connective tissue disorders. Virology 144: 468–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Laska MJ, Brudek T, Nissen KK, Christensen T, Moller-Larsen A, Petersen T, and Nexo BA. 2012. Expression of HERV-Fc1, a human endogenous retrovirus, is increased in patients with active multiple sclerosis. J Virol 86: 3713–3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Curtin F, Bernard C, Levet S, Perron H, Porchet H, Medina J, Malpass S, Lloyd D, Simpson R, and investigators R-TD. 2018. A new therapeutic approach for type 1 diabetes: Rationale for GNbAC1, an anti-HERV-W-Env monoclonal antibody. Diabetes Obes Metab 20: 2075–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Perron H, Germi R, Bernard C, Garcia-Montojo M, Deluen C, Farinelli L, Faucard R, Veas F, Stefas I, Fabriek BO, Van-Horssen J, Van-der-Valk P, Gerdil C, Mancuso R, Saresella M, Clerici M, Marcel S, Creange A, Cavaretta R, Caputo D, Arru G, Morand P, Lang AB, Sotgiu S, Ruprecht K, Rieckmann P, Villoslada P, Chofflon M, Boucraut J, Pelletier J, and Hartung HP. 2012. Human endogenous retrovirus type W envelope expression in blood and brain cells provides new insights into multiple sclerosis disease. Mult Scler 18: 1721–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Faucard R, Madeira A, Gehin N, Authier FJ, Panaite PA, Lesage C, Burgelin I, Bertel M, Bernard C, Curtin F, Lang AB, Steck AJ, Perron H, Kuntzer T, and Creange A. 2016. Human Endogenous Retrovirus and Neuroinflammation in Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy. EBioMedicine 6: 190–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Feschotte C, and Gilbert C. 2012. Endogenous viruses: insights into viral evolution and impact on host biology. Nat Rev Genet 13: 283–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Volkman HE, and Stetson DB. 2014. The enemy within: endogenous retroelements and autoimmune disease. Nature immunology 15: 415–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dolei A 2006. Endogenous retroviruses and human disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2: 149–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kremer D, Schichel T, Forster M, Tzekova N, Bernard C, van der Valk P, van Horssen J, Hartung HP, Perron H, and Kury P. 2013. Human endogenous retrovirus type W envelope protein inhibits oligodendroglial precursor cell differentiation. Ann Neurol 74: 721–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van Horssen J, van der Pol S, Nijland P, Amor S, and Perron H. 2016. Human endogenous retrovirus W in brain lesions: Rationale for targeted therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 8: 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Longhi MS, Ma Y, Mieli-Vergani G, and Vergani D. 2012. Regulatory T cells in autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 57: 932–933; author reply 933–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ferri S, Longhi MS, De Molo C, Lalanne C, Muratori P, Granito A, Hussain MJ, Ma Y, Lenzi M, Mieli-Vergani G, Bianchi FB, Vergani D, and Muratori L. 2010. A multifaceted imbalance of T cells with regulatory function characterizes type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 52: 999–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Longhi MS, Ma Y, Mitry RR, Bogdanos DP, Heneghan M, Cheeseman P, Mieli-Vergani G, and Vergani D. 2005. Effect of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cells on CD8 T-cell function in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. J Autoimmun 25: 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Todd DJ, Lee AH, and Glimcher LH. 2008. The endoplasmic reticulum stress response in immunity and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol 8: 663–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ma X, Bi E, Lu Y, Su P, Huang C, Liu L, Wang Q, Yang M, Kalady MF, Qian J, Zhang A, Gupte AA, Hamilton DJ, Zheng C, and Yi Q. 2019. Cholesterol Induces CD8(+) T Cell Exhaustion in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Metab 30: 143–156 e145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Punkosdy GA, Blain M, Glass DD, Lozano MM, O’Mara L, Dudley JP, Ahmed R, and Shevach EM. 2011. Regulatory T-cell expansion during chronic viral infection is dependent on endogenous retroviral superantigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 3677–3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Marre ML, and Piganelli JD. 2017. Environmental Factors Contribute to beta Cell Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Neo-Antigen Formation in Type 1 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 8: 262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.