Abstract

The impact of industrial chemical components of ambient fine particles (e.g. PM2.5) on cardiovascular health has been poorly explored. Our study reports for the first time the associations between human exposure to complex plastic additive (PA) components of PM2.5 and prolongation of heart rate–corrected QT (QTC) interval by employing a screening-to-validation strategy based on a cohort of 373 participants (136 in the screening set and 237 in the validation set) recruited from 7 communities across China. The high-throughput airborne exposome framework revealed ubiquitous occurrences of 95 of 224 target PAs in PM2.5, totaling from 66.3 to 555 ng m−3 across the study locations. Joint effects were identified for 9 of the 13 groups of PAs with positive associations with QTC interval. Independent effect analysis also identified and validated tris(2-chloroisopropyl) phosphate, di-n-butyl/diisobutyl adipate, and 3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxybenzaldehyde as the key exposure markers for QTC interval prolongation and changes of selected cardiovascular biomarkers. Our findings highlight the important contributions of airborne industrial chemicals to the risks of cardiovascular diseases and underline the critical need for further research on the underlying mechanisms, toxic modes of action, and human exposure risks.

Keywords: ambient fine particles, plastic additives, QTC interval, exposure markers

Significance Statement.

Air pollution constitutes an important risk factor in the etiology of cardiovascular diseases. While exposure to ambient fine particles (e.g. PM2.5) has been well reported to impact cardiovascular health, the role of industrial chemical components of PM2.5 in health effects has been poorly evaluated. Our work reveals the occurrences of a complexity of plastic additive chemicals in airborne fine particles, demonstrating ubiquitous human exposure risks. The screening-to-validation strategy demonstrates that human exposure to complex plastic additive components of PM2.5 is closely associated with the prolongation of heart rate–corrected QT interval. Our findings highlight the importance of airborne industrial chemicals to cardiovascular disease risks.

Introduction

Human exposure to ambient fine particles, such as PM2.5 (particles < 2.5 µm in aerodynamic equivalent diameter), has been reported with close associations with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (1–3). The Harvard Six Cities Study and related studies reported that each increase in PM2.5 by 10 µg m−3 was associated with an adjusted increased risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality of 14 and 26%, respectively (4–6). In particular, the associations between mass concentrations of PM2.5 exposure and the prolongation of QT (the time between the initial deflection of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave) interval, an important marker of ventricular repolarization and a risk factor for cardiac arrhythmia and sudden health, have been well documented in populations of different ages (7, 8).

Other than the mass concentration, myriad chemical components of PM2.5 may represent additional health risks, but the potential effects have been poorly explored in general (9, 10). Indeed, global studies have reported a large variety of plastic additive (PA) chemicals in the atmospheric environment, even in the polar regions (11–13). PAs represent a vast variety of industrial chemicals, functioning as plasticizers, antioxidants, stabilizers, flame retardants, lubricants, or pigments in various types of commercial goods (14, 15). As the additives are not chemically bound with their host products, a portion may migrate from in-use or discarded goods into the environment (14, 16). Some of the volatile or semivolatile PAs may be associated with ambient fine particles, resulting in a high complexity of chemical components of PM2.5 and long-range transport to global environments (11, 17). Many of the PAs have been documented with various toxicological effects. For example, exposure to selected phthalate esters (PAEs), a group of ubiquitous plasticizers, could be associated with increased blood pressure in humans or induce cardiac disorders in mice (18–20). Organophosphate esters (OPEs), a group of plasticizers and flame retardants, could increase the risk of hypertension and atherosclerosis (21, 22). However, there is a lack of clear documentation on whether airborne particle–containing PAs, either as complex mixtures or as individual components, could increase the risks of cardiovascular diseases.

Whether the complex PA components of PM2.5 acting alone or together represent additional cardiovascular risks constitutes an important public health question. To address this question, a high-throughput airborne exposome framework was developed in this study to quantitatively characterize PA components of PM2.5, and a population-based screening-to-validation strategy was employed to explore both the joint effects from the mixtures of PA components and the independent effects from individual PAs on heart rate–corrected QT (QTC) interval and selected cardiovascular biomarkers (Fig. 1). A total of 224 PAs were quantitatively measured in PM2.5 samples collected from 7 communities across China (Fig. 2), where a total of 373 participants aged between 40 and 88 were recruited through the Sub-Clinical Outcomes of Polluted Air in China (SCOPA-China) cohort (Tables S1 and S2). Key PAs would be identified as the exposure markers for the population health effect through the screening-to-validation strategy. Our work demonstrated for the first time the population-based link between exposure to PA components of PM2.5 and prolongation of QTC interval. The findings highlighted the possible contributions of airborne industrial chemicals to cardiovascular disease burdens and underlined the critical need for further research on the underlying mechanisms, toxic modes of action, and human exposure risks.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study design.

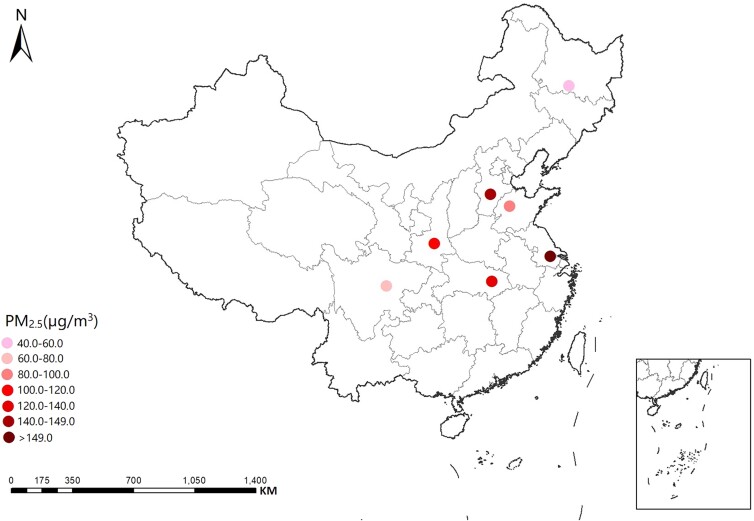

Fig. 2.

Study sites of the SCOPA-China cohort. The sites indicate seven communities located in Shijiazhuang (Hebei Province), Harbin (Heilongjiang Province), Wuhan (Hubei Province), Wuxi (Jiangsu Province), Jinan (Shandong Province), Xi’an (Shanxi Province), and Chengdu (Sichuan Province), respectively. The PM2.5 concentrations at each site are also shown.

Results

Airborne exposome characterization

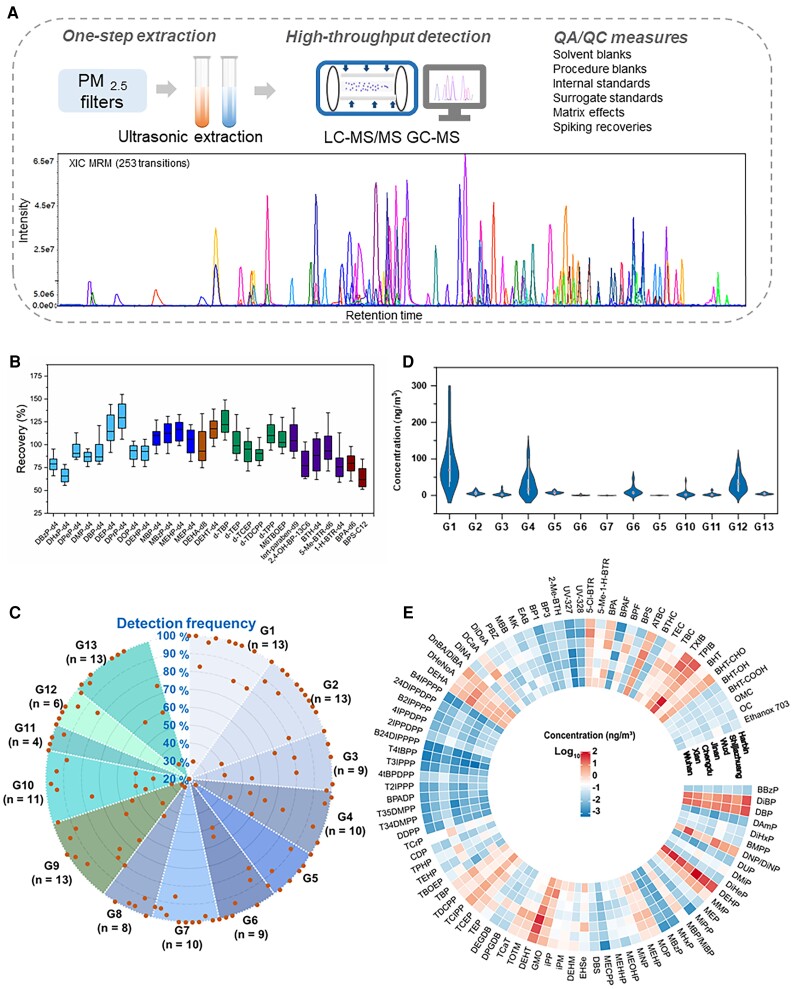

Our target analytes included a total of 224 PAs that have been documented with broad industrial applications (Table S3). We developed a very efficient and high-throughput airborne exposome framework, including a one-step extraction strategy combined with a highly integrated mass spectrometry platform, to quantitatively determine the target PAs (Table S4). Data quality was ensured through a number of quality assurance and control practices (Fig. 3 and Table S5). Through the exposomic determination, 95 of the target PAs exhibited detection frequencies of >80% in our PM2.5 samples (Table S5), with the combined concentrations (referred to as ΣPAs) ranging from 66.3 to 555 ng m−3 across the 7 study sites. The concentrations varied greatly among individuals or different groups of chemicals (Fig. 3 and Table S6). The top five most abundant PAs, namely, di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP; median 28.8 ng m−3), di(2-ethylhexyl) terephthalate (DEHT; 16.5 ng m−3), dibutyl phthalate (15.3 ng m−3), diisobutyl phthalate (11.1 ng m−3), and 2,2,4-trimethyl-1,3-pentanediol-monoiso/butyrate (TPIB; 9.1 ng m−3), constituted 64% of the ΣPAs in the concentrations. By groups, PAEs (G1, median: 69.6 ng m−3) exhibited the highest levels measured in PM2.5, followed by butyrate and citrate esters (BEs and CEs; G12, 32.2 ng m−3), other plasticizers (G4, 17.0 ng m−3), alkyl-OPEs (G5, 8.05 ng m−3), adipate esters (AEs; G8, 7.81 ng m−3), phthalate mono-esters (mono-PAEs; G2, 5.45 ng m−3), synthetic antioxidants (SAOs; G13, 4.38 ng m−3), benzothiazoles and benzotriazoles (BTHs and BTRs; G10, 2.34 ng m−3), fatty acid ester (FAE) plasticizers (G3, 2.29 ng m−3), bisphenols (BPs; G11, 1.52 ng m−3), aryl-OPEs (G6, 0.54 ng m−3), benzophenones and benzoates (BZPs and BZAs; G9, 0.34 ng m−3), and isopropylated and tert-butylated triarylphosphate esters (ITPs and TBPPs; G7, 0.16 ng m−3). Our data demonstrate a high complexity of PAs with ubiquitous distributions in airborne particles.

Fig. 3.

Concentrations of PAs by groups or individuals. A) A simplified flowchart showing the analytical procedures for the airborne exposome framework. B) Recovery data of isotopically labeled surrogate standards used for the analytical approach. C) A radar chart showing the detection frequency distributions of 127 PAs by groups (G1–G13) with a detection frequency >20% in PM2.5. D) A violin plot presenting the concentrations of PA components of PM2.5 by groups of chemicals. The data represent the combined concentrations of chemicals from each group. The box, center line, and vertical line at both ends represent the interquartile range, medium, and maximum and minimum of the data, respectively. The curved areas represent the distributions of concentration data. E) A circular heat map presenting the concentrations of individual PAs components of PM2.5. The data represent the median concentrations of individual chemicals at each study site (i.e. Wuhan, Xi’an, Chengdu, Jinan, Wuxi, Shijiazhuang, or Harbin; Fig. 2). Only chemicals with a detection frequency >80% are included. The full names of individual chemicals in the heat map are summarized in Table S2. G1: PAEs; G2: mono-PAEs; G3: FAE plasticizers; G4: other plasticizers; G5: alkyl-OPEs; G6: aryl-OPEs; G7: ITPs and TBPPs; G8: AEs; G9: BZPs and BZAs; G10: BTHs and BTRs; G11: BPs; G12: BEs and CEs; G13: SAOs.

Joint effects of PA mixtures on QTC interval

The joint effects of exposure to each group of PAs on QTC interval (estimates and 95% credible intervals, CIs) are summarized in Fig. 4. The graph represents the estimated change in the QTC interval associated with a simultaneous change in the exposure levels of each component of the group from a particular threshold (25th to 75th percentile) when compared with when the components were each at the median value (50th percentile). Among the 13 groups of PAs, PAEs (G1), FAE plasticizers (G3), alkyl-OPEs (G5), aryl-OPEs (G6), AEs (G8), BZPs and BZAs (G9), BTHs and BTRs (G10), BPs (G11), BEs and CEs (G12), and SAOs (G13), all exhibited positive associations with the QTC interval in the screening set. For example, the QTC interval increased significantly when the exposure of the G3 group was at the 60th, 70th, or 75th percentile when compared with when the exposure was at the 50th percentile. Similarly, there was a significant increase in the QTC interval when the exposure of the G5 group was at the 55th or 60th percentile when compared with when the exposure was at the 50th percentile, while the changes in the G10 and G13 exposure levels from the 50th percentile to the 55th percentile were both significantly associated with the increase in the QTC interval.

Fig. 4.

Joint effects of each group of PA components in PM2.5 on QTC interval. The results were retrieved from the determination by the BKMR model with the data from the screening set. The full group names of the PAs are summarized in Fig. 3. The x-axis represents the percentile of the exposure levels of each group of chemicals (ranging from the 25th to the 75th percentile), and the y-axis represents the estimated change in the QTC interval associated with a change in the exposure from a certain percentile when compared with when the exposure was at the median value (50th percentile).

Independent effects and key PAs

In addition to the joint effects explored above, the independent effects of individual PAs on QTC interval were further determined. In the screening set, the univariate exposure–response function (and 95% CIs) indicated that the increased exposure to 8 of the 95 PAs in PM2.5 was significantly associated with the prolongation of the QTC interval (Fig. 5A). These key PAs included tris(2-chloroisopropyl) phosphate (TCIPP), di-n-butyl adipate/diisobutyl adipate (DnBA/DiBA), 3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (BHT-CHO), TPIB, 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzophenone (BP3), isopropyl palmitate (IPP), and 2-(2H-benzotriazol-2-yl)-4,6-di-tert-pentylphenol (UV-328). They belong to the PA groups of G3, G5, G8, G9, G10, G12, and G13, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Independent effects of key PA components on QTC interval. A and C) Univariate exposure–response functions and 95% CIs for individual key PAs, determined by the BKMR model in the screening set and validation set, respectively. The x-axis represents the exposure level of a single chemical after intragroup centralization, and the y-axis represents the estimated change in the QTC interval associated with a change in a single chemical, when all of the other chemicals of the same group are fixed at the 50th percentile. B and D) Estimated change in the QTC interval associated with a change in a single chemical from its 25th percentile to the 75th percentile, determined by the BKMR model in the screening set and validation set, respectively, where all of the other chemicals of the same group are fixed at a particular threshold (25th, 50th, or 75th percentile).

To further explore the contribution of key individual PAs to the joint effects, Fig. 5B summarizes the estimated change in the QTC interval associated with a change in a key PA from its 25th percentile to the 75th percentile, where all of the other chemicals of the same group were fixed at a particular threshold (25th, 50th, or 75th percentile). For instance, the changes in the QTC interval were estimated to be 5.26 ms (95% CI: 0.36–10.16), 2.11 ms (95% CI: 0.03–4.18), 3.08 ms (95% CI: 0.25–5.92), 5.26 ms (95% CI: 0.53–9.98), 10.55 ms (95% CI: 4.20–16.90), 3.97 ms (95% CI: 0.26–7.70), and 6.64 ms (95% CI: 2.91–10.37), associated with a change in the exposure to TCIPP, DnBA/DiBA, BHT-CHO, TPIB, BP3, IPP, and UV-328 from their 25th percentile to the 75th percentile, respectively, when all of the other chemicals within each corresponding group were fixed at the 50th percentile. The effects of the key PAs on the QTC interval did not change much when the remaining chemicals had concentrations fixed at the 75th, 50th, or 25th percentile. In short, the concentrations of the remaining chemicals in each group of PAs produced little influence on the independent effects by the key PAs.

Positive associations (although not statistically significant) between the above key PAs and most of the selected cardiovascular markers were also observed (Fig. S1). Eight cardiovascular markers, namely, α2-macroglobulin (A2M), adipsin, C-reactive protein (CRP), fetuin A, haptoglobin, platelet factor-4 (PF4), serum amyloid P (SAP), and von Willebrand factor (vWF), were positively associated with DnBA/DiBA, when the exposure from other chemicals within the same group was fixed at the 25th, 50th, or 75th percentile. Similarly, eight cardiovascular markers (i.e. A2M, adipsin, fetuin A, haptoglobin, L-selectin, PF4, SAP, and vWF) were positively associated with BHT-CHO, eight markers (i.e. A2M, adipsin, CRP, fetuin A, haptoglobin, PF4, SAP, and vWF) with TPIB and seven markers (i.e. A2M, adipsin, fetuin A, L-selectin, PF4, SAP, and vWF) with BP3. In addition, TCIPP was positively associated with haptoglobin, SAP, and vWF, while IPP was associated with A2M and fibrinogen. UV-328 was the only key PA not associated with any of the cardiovascular markers.

Validation and identification of exposure markers

Both the joint effects of different groups of PAs and the independent effects of the key individual PAs on the QTC interval were verified through the validation set. Among the 10 groups of PAs showing positive associations with the QTC interval in the screening set, the positive trends remained in the validation set except for G10 (Fig. S2). Among the eight key PAs identified with significant associations with the prolongation of the QTC interval during the screening phase, the significant associations remained for TCIPP, DnBA/DiBA, and BHT-CHO in the validation set. The changes in the QTC interval were estimated to be 7.83 ms (95% CI: 1.09–14.59), 4.70 ms (95% CI: 0.22–9.19), and 2.99 ms (95% CI: 0.46–5.52), in association with a change in TCIPP, DnBA/DiBA, and BHT-CHO from their 25th percentile to the 75th percentile, respectively, when all of the other chemicals within each group were fixed at the 50th percentile (Fig. 5D). The other four chemicals (i.e. TPIB, BP3, IPP, and UV-328) also exhibited positive trends with the QTC interval in the validation set, although the associations were no longer statistically significant. Therefore, both the joint effects by the mixtures of PAs and the independent effects by key individual PAs exhibited overall consistent patterns between the screening and the validation sets, indicating that our findings on the associations between exposure to the PA components of PM2.5 and prolongation of the QTC interval are reproducible.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated the impact of PA components of PM2.5 on the prolongation of the QTC interval (Fig. 6). The airborne exposome analysis revealed ubiquitous occurrences of complex PAs in ambient environments, likely resulting from large-scale and long-term industrial applications. Joint effects from multiple mixtures of additive chemicals and independent effects from selected PAs on QTC interval were identified and validated. Among the eight key PAs (i.e. TCIPP, DnBA/DiBA, BHT-CHO, TPIB, BP3, IPP, and UV-328) associated with QTC interval prolongation and the possible adverse changes of cardiovascular biomarkers, TCIPP, DnBA/DiBA, and BHT-CHO were finally screened out as potential exposure markers for the population health effect (Fig. 6). In contrast, in our study, the PM2.5 concentrations did not exhibit a significant association with the QTC interval in both the screening and the validation sets (Fig. S3).

Fig. 6.

Summary of the main findings.

The contributions of PA components of PM2.5 to human health risks in general and cardiovascular diseases in particular have not been sufficiently explored. The growing body of evidence from animal or epidemiological investigations has suggested that selected PAs could potentially increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases (23, 24). For example, exposure to selected PAEs and BP A was associated with major cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. hypertension, hyperlipemia, and myocardial infarction), as well as the risk of atherosclerosis and overt cardiovascular disease (24–26). Exposure to selected OPEs in vivo could induce cardiotoxicity and inhibit the cholesterol efflux in macrophages, resulting in the formation of foam cells and eventually leading to atherosclerosis (21). Epidemiological studies also reported the link between OPE exposure and hypertension and cardiotoxicity (21, 22). Indeed, our results indicated that 9 of the 13 groups of PAs exhibited positive trends with the QTC interval in both the screening and the validation sets. As these chemicals are almost concurrently present in the ambient environment, their joint effects on cardiovascular health merit special concerns.

Our work strengthened the argument that exposure to airborne industrial chemicals could increase cardiovascular risks, as the prolongation of the QTC interval is linked to a risk of developing potentially life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias (27–29). In particular, TCIPP, BHT-CHO, and DnBA/DiBA, ranked as the 7th, 9th, and 10th most abundant PAs detected in PM2.5, respectively, can be used as exposure markers for the association with QTC interval prolongation. These key PAs are representative of several important groups of PAs with broad industrial applications. For example, TCIPP represents one of the extensively used OPEs worldwide, mainly functioning as a flame retardant, adhesive agent, and plasticizer (30–32). DnBA and DiBA belong to the group of AEs and are widely used as plasticizers in personal care products (33, 34). BHT-CHO is one of the major transformation products of BHT, which as a SAO, finds broad applications in personal care products, cleaning products, and foodstuffs (35, 36). Large-scale applications of the key PAs have subsequently resulted in ubiquitous human exposure. Indeed, TCIPP, BHT-CHO, and BP3 have been detected in human blood or urine worldwide (35, 37–39). Human data remain limited for DnBA/DiBA, TPIB, IPP, and UV-328, most likely due to the lack of suitable biomonitoring markers, but these chemicals have already been demonstrated with widespread distributions in indoor and outdoor environments (11, 40, 41). Exposure to these key PAs could result in a prolongation of the QTC interval generally within 10 ms in association with a change in the exposure from their 25th percentile to the 75th percentile. Such changes are not likely to induce polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in the clinical situation as long as the overall QTC interval remains small (42). However, the coexistence of airborne exposure and other stressors (e.g. electrolyte disturbance or medication) could accentuate the lengthening of the QTC interval. In short, these key PAs may allow us to efficiently assess the impacts of airborne exposure to PAs on QTC interval and related cardiovascular diseases such as ventricular arrhythmia.

To date, there is a lack of information on the cause–effect relationships between exposure to the PA components of PM2.5 and the QTC interval. We assumed that the exposure could disrupt selected cardiovascular biomarkers and prolongate the QTC interval via a few possible pathways, including, but not limited to, disruption of cardiac potassium or sodium ion channels, induction of oxidative stress, and activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). Cardiac potassium ion channels are critical to maintaining the resting membrane potential and repolarization of the action potential in excitable cardiac myocytes (43). Some chemicals such as arsenic, PAHs, quinidine, and antibiotics have been reported to induce potassium current changes through blockade of the potassium channel, alterations of ion selectivity, or disruption of potassium channel gene expressions (e.g. hERG, human ether-a-go-go-related gene, or KCNJ2, potassium voltage–gated channel subfamily J member 2) (44, 45). Interferences of selected biomarkers such as CRP have also been reported to affect the QTC interval through the mediation of the K+ channel interaction protein 2 (46). Direct effects on the electrophysiological properties of the heart, including the inhibition of sodium or potassium ion channels, have also been reported for selected PAs such as BP A, DEHP, and its metabolite mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate, which subsequently causes a modulation of cardiac repolarization (47, 48). Oxidative stress is essentially involved in eliciting specific cardiac endpoints and modulating the risk of cardiovascular disease and metabolic disruptions following exposure to air pollution (49, 50). Previous studies have suggested that acute exposure to air pollution could promote cardiac arrhythmia, including a prolongation of the QTC interval, through the mediation of oxidative stress (51, 52). Disruptions of several cardiovascular biomarkers such as adipsin, CRP, haptoglobin and fibrinogen have also been reported to be closely associated with oxidative stresses (53–55). Available studies have reported that exposure to TCIPP, BHT-CHO, BP3, UV-328, or di(2-ethylhexyl) adipate (structurally similar to DnBA) could increase reactive oxygen species generation and induce excessive oxidative stress (56–58), which would further impair endothelial-dependent vascular homeostasis (59). In addition, CaMKII activation has been reported to induce arrhythmias in structural diseases by modulation of several ion channels and transporters (60, 61). Exposure to high-level air pollution could induce arrhythmia in healthy mice via CaMKII activation as one of the possible mechanisms (59). Overall, future efforts are greatly needed to identify the underlying mechanisms through which airborne PAs would induce QTC interval prolongation independently or as mixtures.

Our study presented several advantages. First, the study screened for a large complexity of PA components of PM2.5 and explored the associations with prolongation of the QTC interval via a screening-to-validation strategy, ensuring that the findings and conclusions are solid. Second, our study employed a statistical method to assess both the joint effects of PA mixtures and the independent effects of individual chemical components of PM2.5. The study also considered potential nonlinear dose responses and interactions, although no significant outcomes were identified. Third, the study included multiple important cardiovascular biomarkers in the association analysis, which helps explore the potential mechanisms driving the influence of PA components of PM2.5 on QTC interval and lays solid ground for further verification through experimental studies.

However, some limitations also existed in our study. First, the study conducted mediation analysis in the setting of a cross-sectional study design, which would be insufficient to capture the causal relationship between PAs in PM2.5 and QTC interval. This limitation was partially counteracted by our validation strategy, which increased the weight of evidence. Second, there were significant differences in smoking and drinking status between the screening and the validation datasets, which might confound the analysis. However, the alcohol consumption and smoking habits as well as other basic information of participants were controlled during statistical analysis to exclude possible confounding effects. Third, a larger number of research participants than our current sample size would help reach more meaningful findings among the cardiovascular biomarkers measured, which will subsequently facilitate the exploration of potential mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Study design

As summarized in the flowchart of the study design (Fig. 1), a total of 373 participants were recruited from 7 communities through the SCOPA-China cohort (Table S1). A questionnaire survey, a physical examination, and biological sample collection were conducted for each participant. We measured 10 cardiovascular biomarkers in 136 participants, who constituted the screening set. The remaining 237 participants without cardiovascular biomarkers measured were included in the validation set in order to validate the associations between airborne exposure and QTC interval prolongation and identify exposure markers for the population health effect (62). The average ages (±SD) of the screening and validation participants were 64.7 ± 12.9 and 63.4 ± 12.9 years old, respectively (Table S2). The screening and validation sets showed an average (±SD) body mass index (BMI) of 25.3 ± 4.0 and 25.6 ± 4.0 kg m−2 and an annual household income of (6.2 ± 5.7) × 104 and (6.1 ± 6.9) × 104 Chinese Yuan (CNY), respectively. The screening and validation sets exhibited no statistical differences in the average age, BMI, or annual income, as well as in the QTC interval (i.e. 420.6 ± 30.2 vs. 423.1 ± 42.0 ms). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Environmental Health and Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (201511, 201816). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Electrocardiogram examination and cardiovascular biomarkers

An electrocardiogram (ECG) examination was conducted for all participants by trained medical staff. Briefly, the ECG was recorded for 5–10 min with a two-channel (12-lead) ECG monitor using a sampling rate of 256 Hz per channel. The QT interval was measured from each QRS onset to the end of the T wave for normal or supraventricular beats and corrected using Bazett's formula (62), and the data were automatically provided by the ECG moniter. The mean of the QTC readings for the length of the recording was assigned to the corresponding participant's visit and expressed in milliseconds. If abnormal measurements (e.g. artifacts, U waves, bifid T waves, flat T waves, and arrhythmias) were encountered, the staff was instructed to perform repeated measurements after the participants took a brief rest. If abnormal measurements remained after repeated measurements, the data of the participants would be excluded from subsequent analysis.

Peripheral serum was collected from each participant. The participants were asked not to eat for 8 h prior to blood sampling. Serum samples were stored at −80°C prior to chemical analysis. For the participants in the screening set, 10 cardiovascular biomarkers were measured in serum by using the MILLIPLEX MAP Human Cardiovascular Disease (Acute Phase) Magnetic Bead Panel 3-Cardiovascular Disease Multiplex Assay kit (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The biomarkers included A2M, adipsin, CRP, fetuin A, fibrinogen, L-selectin, SAP, haptoglobin, PF4, and vWF (Table S7).

PM2.5 sampling

PM2.5 sampling was conducted at each community with a moderate-volume sampler (TH-150C Intelligent PM2.5 sampler, Wuhan Tianhong Instrument Company, China) under the following conditions: (i) the sampling was conducted on the day of physical examination for each participant; (ii) the sampler was placed about 1.2 m above the rooftop to minimize the impact of dust suspension from the roof; (iii) there should be no major industrial sources within 5 km of the sampler; and (iv) each sampler was set up within 1–25 km radius among the recruited participants in each community. Before sampling, we set the zero point of the sampler and collected PM2.5 on a 90-mm diameter quartz filter (PALL, USA) at a flow rate of 100 L min−1. Prior to and after the sampling, the filters were balanced for at least 24 h in an environmental chamber and then weighted (XS105DU, Mettler Toledo Company, Switzerland). The collection of each PM2.5 sample took place for approximately 24 h and the sampling usually lasted for a total of 3–5 consecutive days at each location. For each participant, the concentrations of PA components in the 24-h sampling of PM2.5 collected during the day of physical examination were designated as his or her exposure levels.

Exposomic characterization of PA components of PM2.5

A one-step extraction strategy was employed to extract target analytes from air filter. Each filter was cut into pieces and then placed into a 15-mL glass tube. After spiking with surrogate standards, the samples were extracted with 3 mL of acetonitrile in an ultrasonication bath for 15 min, followed with a mixture of hexane and dichloromethane (3 mL; v/v = 1:1) for 15 min. The supernatants were combined after centrifugation. The extraction was repeated twice and the combined extract was concentrated and then filtered (0.22 μm, VWR International). The final extract was concentrated, reconstituted with methanol, and then spiked with internal standards.

A highly integrated mass spectrometry platform was developed to quantitatively determine a total of 222 PAs based on an ultraperformance liquid chromatography coupled to a 5500 triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (AB Sciex, Toronto, Canada). DEHP and DEHT were determined on a gas chromatography coupled with 5977A single quadrupole mass (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). A total of 32 isotopically labeled chemicals were used as surrogate or internal standards. The detailed information on target analytes and instrumental analyses is summarized in Tables S3 and S4. Three chemicals coeluted with their corresponding isomers, and their concentrations were reported as a combination of coeluted ones (e.g. DnBA/DiBA represents the total concentration of DnBA and its isomer DiBA).

The limit of quantification (LOQ) of an analyte was defined as its response 10 times the standard deviation of the noise. For the chemicals detectable in blanks, their LOQs were determined as the average contamination in blanks plus 10 times the standard deviation of contamination (11). Several quality assurance and control procedures were conducted (see details in Table S5). Any analyte with >20% of concentration measurements below the LOQ was excluded from further exposure matching. PAs included in the statistical analysis were divided into 13 groups based on their molecular structures or application purposes (details given in Table S6).

Covariate collection

The face-to-face questionnaire interview with the participants was conducted by our trained investigators. If there was any omission or logical error, the investigator would immediately supplement the data and provide feedback. The contents of the questionnaire were controlled as covariates, mainly including the basic information: sex (male, female, categorical) and age (continuous); lifestyles: smoking (never smoking, past smoking, and current smoking, categorical) and alcohol consumption (current drinking: participants who drank more than once a month on average during the last 12 months, never drinking: other participants besides current drinking, categorical); and the socioeconomic factor: annual household income (continuous). During physical examinations, height and weight data were collected from each participant. The BMI (kg m−2) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters, and controlled as a continuous variable. The daily average temperature and relative humidity data were collected from the nearest monitoring station of each community via the China Meteorological Administration data sharing service (http://data.cma.cn), and controlled as continuous variables.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD, while the categorical variables were presented as numbers (percentage). To determine whether there is a significant difference between the descriptive statistics of the screening and validation sets, we used χ2 tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon tests for nonnormally distributed continuous variables. The identification of key exposure markers from the complexity of PA components of PM2.5 included the three following steps.

Step 1: determine joint and independent effects and identify key PAs

The mixed exposure model Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) was used to establish the associations of 13 groups of PAs with the QTC interval in the screening set. The BKMR model allows for identifying independent effects from individual exposure in addition to the joint effects from exposure to a mixture of chemicals by using a kernel function (63, 64). The exposure levels in each group were centralized, i.e. subtracting the mean of the concentration matrix and dividing it by the standard deviation of the concentration matrix for each group. We created the BKMR models based on the following equation for each of the 13 groups of PAs:

| (1) |

where Yi is the QTC interval; h () is the exposure–response function, which incorporates both nonlinear relationships and interactions among exposures, with the concentrations of PAs treated as Z to fit the model; zi is a vector of covariates, including sex, age, BMI, income, smoking, drinking, temperature, and relative humidity; ei is a random error term. We used a Gaussian link function with BKMR in consideration of the current continuous outcome and implemented a hierarchical variable selection method with 50,000 iterations using a Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm. Key PAs could be screened out when the overall effect of the group of chemicals containing the key PAs exhibited a positive association trend with QTC, while these individual chemicals were also significantly associated with the prolongation of the QTC interval.

Step 2: establish the associations between key PAs and cardiovascular biomarkers

The BKMR model was used to further analyze the associations between the key individual PAs significantly associated with the QTC interval (identified in step 1) and 10 cardiovascular biomarkers. The same covariates were adjusted, and the same number of iterations were applied to the BKMR model.

Step 3: validate the key PAs as exposure markers for the population health effect

To verify the results of the screening set, we used the validation set to establish the BKMR model (Eq. 1) between the QTC interval and the identified key PAs. If the key PAs remained with significant associations with the prolongation of the QTC interval in the validation set, the result of the screening phase was considered to pass the verification test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the volunteers participating in the study.

Contributor Information

Xiaotu Liu, School of Environment and Guangdong Key Laboratory of Environmental Pollution and Health, Jinan University, Guangzhou 511443, China.

Yanwen Wang, China CDC Key Laboratory of Environment and Population Health, National Institute of Environmental Health, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing 100021, China.

Jianlong Fang, China CDC Key Laboratory of Environment and Population Health, National Institute of Environmental Health, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing 100021, China.

Renjie Chen, School of Public Health, Key Lab of Public Health Safety of the Ministry of Education and NHC Key Lab of Health Technology Assessment, Shanghai Institute of Infectious Disease and Biosecurity, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Yue Sun, China CDC Key Laboratory of Environment and Population Health, National Institute of Environmental Health, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing 100021, China.

Shuqin Tang, School of Environment and Guangdong Key Laboratory of Environmental Pollution and Health, Jinan University, Guangzhou 511443, China.

Minghao Wang, China CDC Key Laboratory of Environment and Population Health, National Institute of Environmental Health, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing 100021, China.

Haidong Kan, School of Public Health, Key Lab of Public Health Safety of the Ministry of Education and NHC Key Lab of Health Technology Assessment, Shanghai Institute of Infectious Disease and Biosecurity, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Tiantian Li, China CDC Key Laboratory of Environment and Population Health, National Institute of Environmental Health, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing 100021, China.

Da Chen, School of Environment and Guangdong Key Laboratory of Environmental Pollution and Health, Jinan University, Guangzhou 511443, China.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at PNAS Nexus online.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92143202, 41977373, 92043301, 41907368, and 42177404) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (21620105).

Author Contributions

D.C., T.L., and H.K. designed the research. X.L. and Y.W. carried out the formal analysis. X.L., Y.W., J.F., R.C., Y.S., S.T., and M.W. contributed to data collection. X.L., Y.W., J.F., R.C., Y.S., S.T., M.W., and H.K. contributed to data curation. D.C., T.L., X.L., Y.W., Y.S., and S.T. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. D.C. and T.L. directed and supervised the study. X.L. and Y.W. contributed equally to this work.

Data Availability

All data are available in the main text or the Supplementary material.

References

- 1. Cohen AJ, et al. 2017. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the global burden of diseases study 2015. Lancet. 389(10082):1907–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brook RD, et al. 2004. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the expert panel on population and prevention science of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 109(21):2655–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nel A. 2005. Air pollution-related illness: effects of particles. Science. 308(5723):804–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lepeule J, Laden F, Dockery D, Schwartz J. 2012. Chronic exposure to fine particles and mortality: an extended follow-up of the Harvard six cities study from 1974 to 2009. Environ Health Perspect. 120(7):965–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laden F, Schwartz J, Speizer FE, Dockery DW. 2006. Reduction in fine particulate air pollution and mortality: extended follow-up of the Harvard six cities study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 173(6):667–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pope AC, et al. 2004. Cardiovascular mortality and long-term exposure to particulate air pollution: epidemiological evidence of general pathophysiological pathways of disease. Circulation. 109(1):71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keating MT, Sanguinetti MC. 2001. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias. Cell. 104:569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Henneberger A, et al. 2005. Repolarization changes induced by air pollution in ischemic heart disease patients. Environ Health Perspect. 113(4):440–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weber R. 2020. A map of potentially harmful aerosols in Europe. Nature. 587:369–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bhatnagar A. 2006. Environmental cardiology: studying mechanistic links between pollution and heart disease. Circ Res. 99(7):692–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu X, et al. 2021. Plastic additives in ambient fine particulate matter in the Pearl River Delta, China: high-throughput characterization and health implications. Environ Sci Technol. 55(8):4474–4482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu Q, et al. 2021. Uncovering global-scale risks from commercial chemicals in air. Nature. 600(7889):456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li J, et al. 2017. Organophosphate esters in air, snow, and seawater in the North Atlantic and the Arctic. Environ Sci Technol. 51(12):6887–6896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hahladakis JN, Velis CA, Weber R, Iacovidou E, Purnell P. 2018. An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. J Hazard Mater. 344:179–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kelley KE, Hernandez-Diaz S, Chaplin EL, Hauser R, Mitchell AA. 2012. Identification of phthalates in medications and dietary supplement formulations in the United States and Canada. Environ Health Perspect. 120(3):379–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Howdeshell KL, et al. 2003. Bisphenol A is released from used polycarbonate animal cages into water at room temperature. Environ Health Perspect. 111(9):1180–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang T, et al. 2018. Semivolatile organic compounds (SOCs) in fine particulate matter (PM2.5) during clear, fog, and haze episodes in winter in Beijing, China. Environ Sci Technol. 52(9):5199–5207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Posnack NG, Swift LM, Kay MW, Lee NH, Sarvazyan N. 2012. Phthalate exposure changes the metabolic profile of cardiac muscle cells. Environ Health Perspect. 120(9):1243–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rajagopalan S, Landrigan PJ. 2021. Pollution and the heart. N Engl J Med. 385(20):1881–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu H, et al. 2021. Maternal phthalates exposure and blood pressure during and after pregnancy in the PROGRESS study. Environ Health Perspect. 129(12):127007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu W, Gao P, Wang L, Hu J. 2023. Endocrine disrupting toxicity of aryl organophosphate esters and mode of action. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 53:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li Y, et al. 2020. Presence of organophosphate esters in plasma of patients with hypertension in Hubei Province, China. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 27(19):24059–24069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kahn LG, Philippat C, Nakayama SF, Slama R, Trasande L. 2020. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: implications for human health. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 8(8):703–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Valvi D, et al. 2015. Prenatal phthalate exposure and childhood growth and blood pressure: evidence from the Spanish INMA-Sabadell birth cohort study. Environ Health Perspect. 123(10):1022–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zheng Y, et al. 2020. Di-(2-ethyl hexyl) phthalate induces necroptosis in chicken cardiomyocytes by triggering calcium overload. J Hazard Mater. 387:121696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sol CM, et al. 2020. Fetal phthalates and bisphenols and childhood lipid and glucose metabolism. A population-based prospective cohort study. Environ Int. 144:106063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Owens RC, Pharm D. 2001. Risk assessment for antimicrobial agent-induced QTC interval prolongation and torsades de pointes. Pharmacotherapy. 21(3):301–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roden DM, et al. 1996. Multiple mechanisms in the long-QT syndrome: current knowledge, gaps, and future directions. Circulation. 94(8):1996–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Splawski I, et al. 2002. Variant of SCN5A sodium channel implicated in risk of cardiac arrhythmia. Science. 297(5585):1333–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vojta S, Melymuk L, Klánová J. 2017. Changes in flame retardant and legacy contaminant concentrations in indoor air during building construction, furnishing, and use. Environ Sci Technol. 51(20):11891–11899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu Q, et al. 2019. Uptake kinetics, accumulation, and long-distance transport of organophosphate esters in plants: impacts of chemical and plant properties. Environ Sci Technol. 53(9):4940–4947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang T, et al. 2018. Organophosphorus esters (OPEs) in PM2.5 in urban and e-waste recycling regions in southern China: concentrations, sources, and emissions. Environ Res. 167:437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tang S, et al. 2021. A cocktail of industrial chemicals in lipstick and nail polish: profiles and health implications. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 8(9):760–765. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vimalkumar K, Zhu H, Kannan K. 2022. Widespread occurrence of phthalate and non-phthalate plasticizers in single-use facemasks collected in the United States. Environ Int. 158:106967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu R, Mabury SA. 2020. Synthetic phenolic antioxidants: a review of environmental occurrence, fate, human exposure, and toxicity. Environ Sci Technol. 54(19):11706–11719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nieva-Echevarria B, Manzanos MJ, Goicoechea E, Guillen MD. 2015. 2,6-Di-tert-butyl-hydroxytoluene and its metabolites in foods. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 14(1):67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang L, Kannan K. 2013. Characteristic profiles of benzonphenone-3 and its derivatives in urine of children and adults from the United States and China. Environ Sci Technol. 47(21):12532–12538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wolff MS, et al. 2007. Pilot study of urinary biomarkers of phytoestrogens, phthalates, and phenols in girls. Environ Health Perspect. 115(1):116–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhao F, et al. 2016. Levels of blood organophosphorus flame retardants and association with changes in human sphingolipid homeostasis. Environ Sci Technol. 50(16):8896–8903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Takeuchi S, et al. 2014. Detection of 34 plasticizers and 25 flame retardants in indoor air from houses in Sapporo, Japan. Sci Total Environ. 491–492:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maceira A, Borrull F, Marce RM. 2019. Occurrence of plastic additives in outdoor air particulate matters from two industrial parks of Tarragona, Spain: human inhalation intake risk assessment. J Hazard Mater. 373:649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lester RM, Paglialunga S, Johnson IA. 2019. QT assessment in early drug development: the long and the short of it. Int J Mol Sci. 20:1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sanguinetti MC, Tristani-Firouzi M. 2006. hERG potassium channels and cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 440(7083):463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mumford JL, et al. 2007. Chronic arsenic exposure and cardiac repolarization abnormalities with QT interval prolongation in a population-based study. Environ Health Perspect. 115(5):690–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Moon KA, et al. 2018. Association of low-moderate urine arsenic and QT interval: cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from the Strong Heart Study. Environ Pollut. 240:894–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xie Y, et al. 2015. Effects of C-reactive protein on K+ channel interaction protein 2 in cardiomyocytes. Am J Transl Res. 7(5):922–931. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ramadan M, Cooper B, Posnack NG. 2020. Bisphenols and phthalates: plastic chemical exposures can contribute to adverse cardiovascular health outcomes. Birth Defects Res. 112:1362–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jaimes R, et al. 2019. Plasticizer interaction with the heart. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 12:e007294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Al-Kindi SG, Brook RD, Biswal S, Rajagopalan S. 2020. Environmental determinants of cardiovascular disease: lessons learned from air pollution. Nat Rev Cardiol. 17(10):656–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Daellenbach KR, et al. 2020. Sources of particulate-matter air pollution and its oxidative potential in Europe. Nature. 587(7834):414–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gurgueira SA, Lawrence J, Coull B, Murthy GGK, González-Flecha B. 2002. Rapid increases in the steady-state concentration of reactive oxygen species in the lungs and heart after particulate air pollution inhalation. Environ Health Perspect. 110(8):749–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Baja ES, et al. 2010. Traffic-related air pollution and QT interval: modification by diabetes, obesity, and oxidative stress gene polymorphisms in the normative aging study. Environ Health Perspect. 118(6):840–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Laurikka A, et al. 2014. Adipocytokine resistin correlates with oxidative stress and myocardial injury in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardio-Thorac. 46(4):729–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Abramson JL, et al. 2005. Association between novel oxidative stress markers and C-reactive protein among adults without clinical coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 178(1):115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Asleh R, Guetta J, Kalet-Litman S, Miller-Lotan R, Levy AP. 2005. Haptoglobin genotype- and diabetes-dependent differences in iron-mediated oxidative stress in vitro and in vivo. Circ Res. 96(4):435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cristale J, et al. 2017. Role of oxygen and DOM in sunlight induced photodegradation of organophosphorous flame retardants in river water. J Hazard Mater. 323(Pt A):242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mao F, He Y, Gin KY-H. 2020. Antioxidant responses in cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa caused by two commonly used UV filters, benzophenone-1 and benzophenone-3, at environmentally relevant concentrations. J Hazard Mater. 396:122587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Xu X, et al. 2021. Synthetic phenolic antioxidants: metabolism, hazards and mechanism of action. Food Chem. 353:129488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Park H, et al. 2021. High level of real urban air pollution promotes cardiac arrhythmia in healthy mice. Korean Circ J. 51(2):157–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Erickson JR, et al. 2008. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell. 133(3):462–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chang J-Y, Nakahata Y, Hayano Y, Yasuda R. 2019. Mechanisms of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II activation in single dendritic spines. Nat Commun. 10(1):2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bednar MM, Harrigan EP, Anziano RJ, Camm AJ, Ruskin JN. 2001. The QT interval. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 43(5):1–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bobb JF, Claus Henn B, Valeri L, Coull BA. 2018. Statistical software for analyzing the health effects of multiple concurrent exposures via Bayesian kernel machine regression. Environ Health. 17(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bobb JF, et al. 2015. Bayesian kernel machine regression for estimating the health effects of multi-pollutant mixtures. Biostatistics. 16(3):493–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the Supplementary material.