Abstract

The vaginal microbiome includes diverse microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus [L.] spp. that protect against infections, modulate inflammation, and regulate vaginal homeostasis. Because it is challenging to incorporate vaginal microbiota into in vitro models, including organ-on-a-chip systems, we assessed microbial metabolites as reliable proxies in addition to traditional vaginal epithelial cultures (VECs). Human immortalized VECs cultured on transwells with an air-liquid interface generated stratified cell layers colonized by transplanted healthy microbiomes (L. jensenii- or L. crispatus-dominant) or a community representing bacterial vaginosis (BV). After 48-hours, a qPCR array confirmed the expected donor community profiles. Pooled apical and basal supernatants were subjected to metabolomic analysis (untargeted mass spectrometry) followed by ingenuity pathways analysis (IPA). To determine the bacterial metabolites’ ability to recreate the vaginal microenvironment in vitro, pooled bacteria-free metabolites were added to traditional VEC cultures. Cell morphology, viability, and cytokine production were assessed. IPA analysis of metabolites from colonized samples contained fatty acids, nucleic acids, and sugar acids that were associated with signaling networks that contribute to secondary metabolism, anti-fungal, and anti-inflammatory functions indicative of a healthy vaginal microbiome compared to sterile VEC transwell metabolites. Pooled metabolites did not affect cell morphology or induce cell death (~5.5%) of VEC cultures (n=3) after 72-hours. However, metabolites created an anti-inflammatory milieu by increasing IL-10 production (p=0.06, T-test) and significantly suppressing pro-inflammatory IL-6 (p=0.0001), IL-8 (p=0.009), and TNFα (p=0.0007) compared to naïve VEC cultures. BV VEC conditioned-medium did not affect cell morphology nor viability; however, it induced a pro-inflammatory environment by elevating levels of IL-6 (p=0.023), IL-8 (p=0.031), and TNFα (p=0.021) when compared to L.-dominate microbiome-conditioned medium. VEC transwells provide a suitable ex vivo system to support the production of bacterial metabolites consistent with the vaginal milieu allowing subsequent in vitro studies with enhanced accuracy and utility.

Introduction

The vaginal microbiota forms a complex host-bacterial network that works together to maintain the delicate physiological environment of the vagina by regulating pH and immune status1,2. The composition and behavior of the vaginal microbes can vary depending on factors such as age, race, ethnicity, sexual activity, menstrual cycle, and even the use of contraceptives1,3,4. In women of childbearing age, a healthy vagina is characterized by a Lactobacillus (L.) dominant environment, most often showing a high abundance of L. crispatus, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii5. However, each plays a different physiologic role in maintaining homeostasis and differs in susceptibility to dysbiosis. For example, L. crispatus dominant environments are stable and do not quickly sift to dysbiosis compared to non-L.crispatus dominant environments6,7. While L. iners dominant environments have reduced protection from pathogenic bacteria do to its ability to only produce L-lactis acid, causing it to be detected more frequently in women with bacteria vaginosis8. Caucasian women of European descent and Asian women are more likely to carry L. crispatus, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii, however, women of African or Hispanic origin are likely to have a vaginal community dominated by L. iners6 or in general, L. non-dominate communities under physiologic conditions. These differences highlight the complexity and diversity in host-microbe-environment interactions that are necessary for maintaining healthy reproductive status and pregnancy maintenance.

Normally, these species of bacteria play an important role in maintaining the acidic environment of the vagina by production of lactic acid through metabolism of VEC supplied carbon compounds. This acidic environment minimizes the overgrowth of harmful bacteria, including those seen in bacterial vaginosis (BV). The causes of BV have been linked to a disruption of the L.-dominant environment and an increase of other anaerobic bacteria and pro-inflammatory markers leading to vaginal dysbiosis2. In fact, approximately 30% of women of reproductive age experience BV, and pregnant women are more likely to be affected by BV as compared to non-pregnant women9. This is likely due to hormonal differences that regulate estrogen production and glycogen metabolism during pregnancy that promote a less-diverse environment with reduced Lactobacilli abundance10. BV or vaginal dysbiosis during pregnancy has been linked to several complications such as ascending bacterial infections, preterm birth, preterm premature rupture of membranes, and lower birth weight11. Interestingly, African and Hispanic women on average have a higher prevalence of Gardnerella, Atopobium, and Corynebacterium among other obligate and facultative bacterium that normally maintain a higher pH than Lactobacilli without clinical presentation of BV12. This suggests that the population of the bacterium may not be the sole factor in identifying or inducing vaginal dysbiosis.

The vaginal microbiome interacts with the uterine epithelia, mucosa, and resident immune cells in order to maintain homeostasis during pregnancy both directly and through metabolites spread through genital tract fluids12–14. Specifically, metabolites produced by L.-dominate microbiomes function to maintain vaginal pH (i.e., lactic acid) and antimicrobial (i.e., hydrogen peroxide) or anti-inflammatory states (i.e., short chain fatty acids such as acetate, propionic acid, and butyrate) that play important roles in regulating the lower reproductive tract immune system15,16. Recently, with the use of metabolic fingerprinting, specific metabolites from vaginal fluid have been utilized to identify the healthy vs. pathologic state of the cervix (i.e., invasive cervical cancer is associated with 3-hydroxybutyrate, eicosanoid, and oleate)17. Such results justify additional studies to validate the biological relevance of vaginal metabolites and their potential use as biomarkers.

Given the importance and delicate balance of the vaginal microbiome and the genital tract mucosa, it is critical to develop advanced in vitro methods of incorporating these components into traditional cell culture systems. However, there are several limitations hindering the scientific community from incorporating vaginal microbiomes directly into in vitro models including: clinical challenges and limitations in collecting and preserving microbiome samples from diverse population groups18,19, in vitro changes in culture-multi-species microbiome colonies20, lack of glycogen/mucin backbone molecules to support microbial colonization21, and recreating cell-microbe interactions without inducing pathologic overgrowth20. Therefore, to provide an in vitro proxy for the proper cell-multi-species microbe interactions found in the vaginal tract, metabolites were assessed as a surrogate to determine their sufficiency in modeling the in vivo environment.

To recreate functionally and biologically relevant human vaginal epithelial cell (VEC) cultures in vitro, we established and assessed a methodology for culturing and generating vaginal microbiome metabolites that can accurately biomimic a L.-dominant environment. The objective of this study was to examine the utilization of microbial metabolites as a reliable proxy for the vaginal microbiome in traditional VEC culture and to assess its future utility in organ-on-chip (OOC) platforms. This was accomplished in three phases: 1) production of VEC+microbiome metabolites utilizing an established ex vivo VEC transwell setup14,22, 2) characterization of VEC+microbiome metabolites, and 3) functional assessment of VEC+microbiome metabolites in traditional 2D VEC culture. These studies revealed that VEC+microbiome metabolites can be generated and are sufficient to create a homeostatic L.-dominant environment within in vitro 2D VEC cultures that biomimics responses seen in vivo.

Results

Generation of vaginal microbiome metabolites from healthy and dysbiotic states

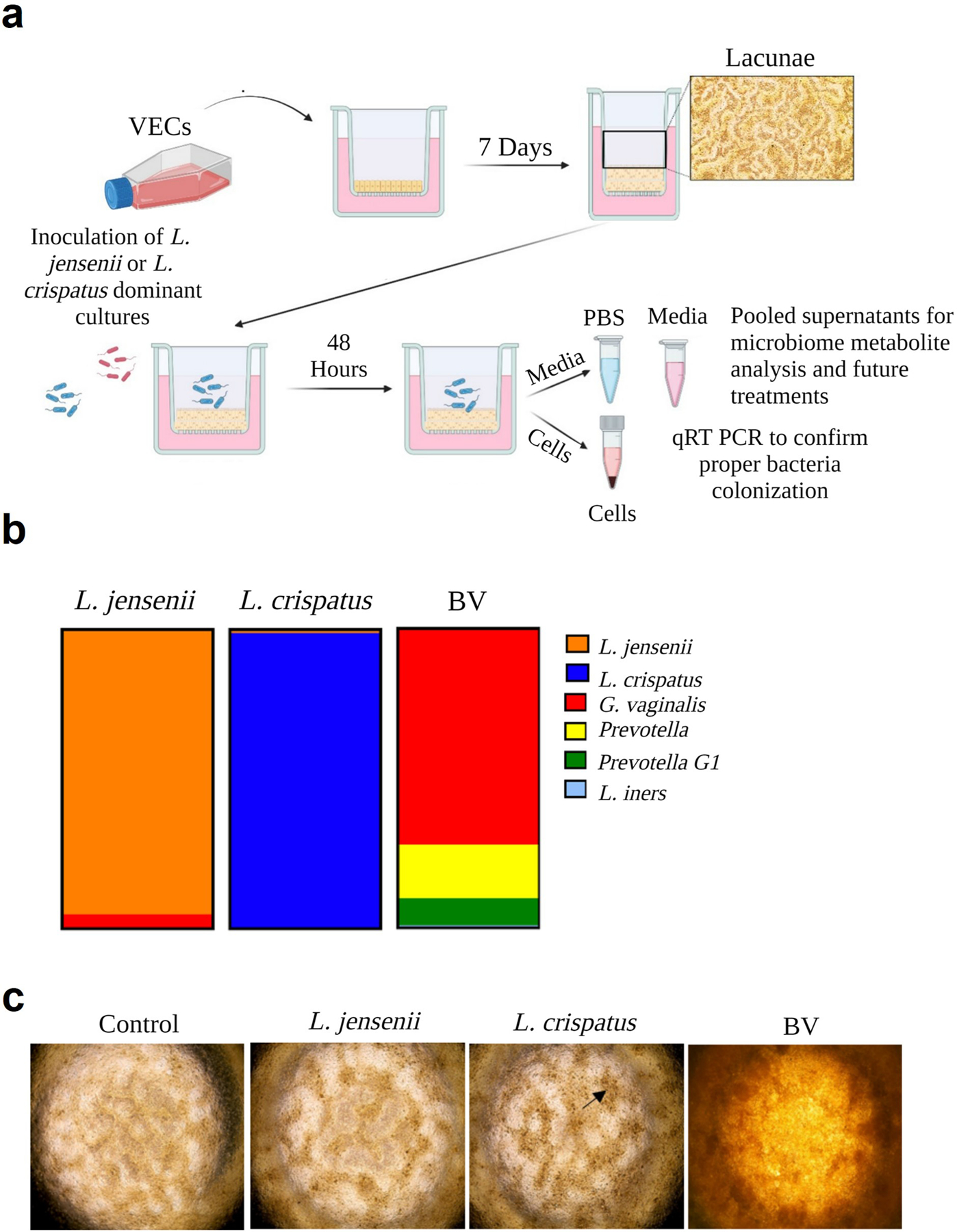

To generate functionally relevant vaginal microbiome-cell-derived metabolites for further in vitro analysis, an established ex vivo multi-layered VEC transwell platform was utilized12. This system has been previously shown to support the colonization of a variety of diverse vaginal microbiota communities14. VECs cultured at an air-liquid interface on transwell inserts for 7 days, formed stratified epithelial layers and surface structures consistent with lacunae (Figure 1a). Subsequently, three previously characterized, and cultured vaginal microbiome samples (i.e., L. jensenii-dominated, L. crispatus-dominated, or bacterial vaginosis [BV] characterized by colonization of over 15 bacterial spp. [Supplemental Table S1]) were transplanted onto the apical air-interface surface and allowed to colonize for 48-hours (Figure 1a–b). Bacterial growth was observed by phase microscopy as dense brown patches on top of lacunae (black arrow). Overgrowth of the BV community along with a pungent smell was observed in parallel VEC cultures (Figure 1c). Additionally, extensive overgrowth of the BV community prevented full focus of light cast by phase contrast microscopy turning the representative image a dark orange color. Using qPCR array analysis, the community profiles were confirmed to be consistent with the donated sample (Figure 1b; Supplemental Table S1). Next, we determined if the ex vivo VEC system also produced functionally active and biologically relevant metabolites biomimicking L. jensenii-, L. crispatus-dominant or BV vaginal environments.

Figure 1. Generation of vaginal microbiome metabolites from healthy and dysbiosis states.

a) Human immortalized vaginal epithelial cells (VEC) were cultured in KSFM medium on transwell inserts for seven days to generate stratified epithelial cultures. Medium was changed every 48-hours for 7 days to allow for the formation of Lacunae. The three vaginal microbiome samples from previously collected specimens were added to the VEC transwells to colonize for 48-hours. (right). b) Previously collected vaginal microbiome swab samples—L. jensenii, L. crispatus, and bacterial vaginosis (BV) dominant samples were selected for seeding into the VEC ex vivo transwells. These samples were cultured, cryopreserved, and subsequently revived for the purpose of this project. c) Phase contrast microscopy showed colonization on top of lacunae (black arrow) (2x images), and proper colonization of the microbiome was confirmed through qPCR analysis.

Characterization of cell and microbiome metabolites

To decipher the functional properties and characterize VEC+microbiome metabolites generated from the ex vivo VEC transwell system, the apical (PBS lavage) and basal media from L.-dominate microbiome ex vivo VEC cultures was pooled, filtered, and compared to sterile ex vivo VEC culture supernatants. We utilized untargeted mass spectrometry and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) to identify the up and downregulated compounds (i.e., Log2 Fold Change) and their potential signaling pathways. This comprehensive approach facilitated a deep dive into the nuances of microbiome metabolites, enabling us to explore whether their functions echo those typically observed in a healthy vaginal microbiome1,15,20,23,24.

To molecularly profile these metabolites, IPA was utilized to identify the metabolite categories and functions of the differentially expressed components (Supplemental Table S2). The analysis revealed that the top-upregulated metabolites included fatty acids, nucleic acids, and sugar acids that are functionally associated with anti-microbial, anti-fungal, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties (Table 1). Furthermore, these components were found to be associated with key canonical pathways, such as tRNA turnover, creatine and putrescine biosynthesis, and DNA methylation (Figure 2a). Notably, signaling networks such as AKT/ERK, nitric oxide, and creatine were also implicated from differentially expressed components (Figure 2b; Table 2). Overall, these findings highlight the substantial contribution of these metabolites to various metabolic processes, as well as their potential roles in anti-fungal and anti-inflammatory functions, mirroring the classic features observed in a healthy vaginal microbiome.

Table 1:

Top 10 upregulated compounds compared to sterile VEC media metabolites

| Name | Category | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Propionic acid | Fatty Acid | Antimicrobial/Antifungal |

| (E)-4-Coumaric acid | Phenylpropanoid | Antimicrobial/Anti-inflammatory |

| Gabapentin | Gabapentinoid | Xenobiotic |

| Thymine | Nucleic acid | Cell survival |

| Piperidine | Cyclohexane | Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites |

| D-arabinonic acid | Sugar acid | Cosmetic additive |

| 5-Methoxytryptophol | Tryptopan metabolite | Antioxidant |

| Isofagomine | Imino sugar | Cosmetic additive |

| Palmitic acid | Fatty acid | Block viral entry |

| Cinnamyl alcohol | Aromatic alcohol | Cosmetic additive |

Figure 2. Characterization of cell and microbiome metabolites.

The apical+basal supernatants dominated by L. jensenii + L. crispatus microbiomes were collected, filtered, and analyzed for metabolites through untargeted mass spectrometry analysis. The resulting data were further analyzed using IPA to identify the specific metabolites produced in these samples. a) Compounds were associated with canonical pathways such as tRNA turnover, creatine and putrescine biosynthesis, and DNA methylation (Z-score 0: Not significant [white bars as indicated by IPA]). b) signaling networks (AKT/ERK, nitric oxide, creatine), that contribute to secondary metabolism, anti-fungal, and anti-inflammatory functions of a healthy vaginal microbiome. Green ovals highlight the dominate upstream activators, signalers, and downstream related compounds in each network.

Table 2:

Upstream and downstream regulators of signaling networks

| Name | Network Associated Functions | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Upstream: Palmitic acid | Cellular function and maintenance, Molecular Transport, Carbohydrate metabolism |

| Signalers: AKT & ERK1/2 | ||

| Downstream: Creatine | ||

| 2 | Upstream: SIRT1 | Small Molecule biochemistry, free radical scavenging, cell signaling |

| Signalers: Creb & PPARGC1A | ||

| Downstream: Nitric oxide | ||

| 3 | Upstream: CYP3A4 | Carbohydrate metabolism, drug metabolism, endocrine system development and function |

| Downstream: 2-hydroxynevirapine |

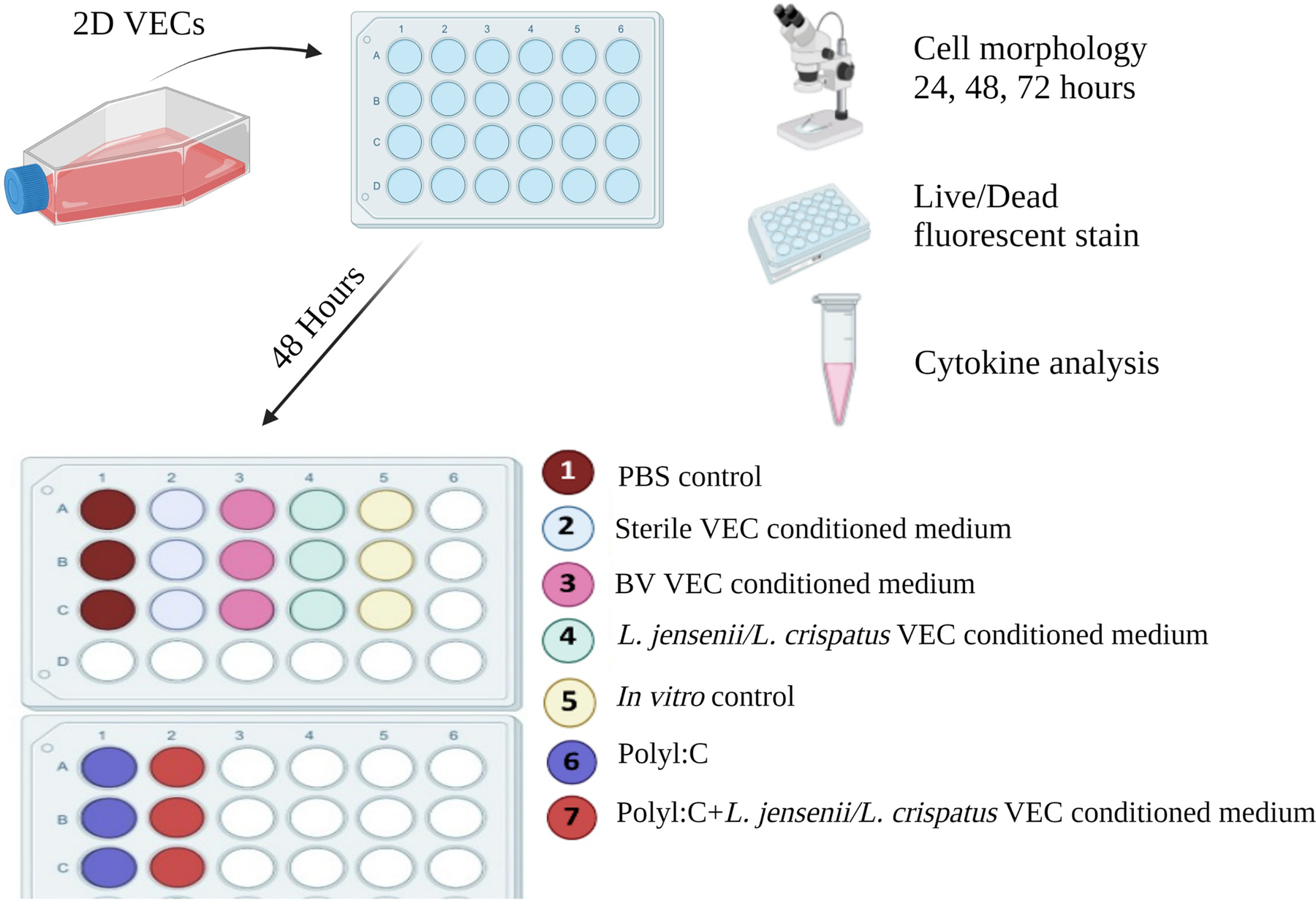

Ex vivo-generated vaginal microbiome metabolites did not induce morphologic changes nor cell death

VEC+microbiome metabolites effects were evaluated in comparison to standard culture conditions. Traditional 2D culture of VECs within a 24-well plate were supplemented at a 1:1 ratio with fresh media to generate a variety of conditions (Figure 3). Control conditions included a PBS control which included VECs, growth KSFM medium, and 4% PBS, an in vitro control which was comprised of VECs and growth KSFM medium, and a positive control which was comprised of Polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (PolyI:C - 0.1mg/ml). Conditioned media removed from the apical and basal sides of ex vivo VECs grown with or without L. jensenii/L. crispatus or BV was used as a metabolite supplement (i.e., sterile VEC conditioned-medium; BV VEC conditioned-medium; L. jensenii/L. crispatus VEC conditioned-medium) (Figure 3). Cell characteristic assessments, including cell morphology and viability, were conducted through 72-hours of exposure.

Figure 3. Experimental workflow assessing VEC+Microbiome induced function.

To determine the effect of microbiome metabolites on 2D VEC cultures, VECs were colonized in a 2D monolayer for 72-hours with various treatments consisting of positive controls (Poly I:C [0.1mg/ml] or BV), experimental controls (VEC medium or PBS), and the experimental treatments at a 1:1 ratio of VEC medium. After 72-hours cells were assessed for morphological changes and cell viability. Medium was collected a processed for pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine analysis.

Brightfield microscopy was used to visualize morphological characteristics of VECs following 24, 48, or 72-hour of culture with the indicated supplements. Microscopic analysis revealed that the addition of L.-dominate VEC-conditioned medium did not elicit discernible alterations in VEC morphology (Figure 4 – lane 4) across the observation period and was indistinguishable from parallel cultures exposed to standard VEC medium (i.e., In vitro control) (Figure 4 – lane 5). Similarly, the BV VEC conditioned-medium and other experimental control supplements failed to cause any gross effects on VEC morphology (Figure 4). In contrast, treatment with PolyI:C (0.1mg/mL), a positive control known to induce epithelial cell death and inflammation25, produced punctate cell morphologies (black box) by 24-hours that increased over the 72-hour period (Figure 4 – lane 6). Co-treatment with L.-dominate VEC-conditioned medium and PolyI:C induced a partial recovery (red box) (Figure 4 – lane 7), suggesting a putative beneficial impact of microbiome-derived metabolites consistent with past reports of outcomes in Lactobacillus-colonized VEC14,22,26.

Figure 4. Functional assessment of VEC+Microbiome metabolites effects on cell morphology.

Brightfield microscopy documented the cell morphology of VECs after they were cultured with various treatments for 72-hours. Microbiome-conditioned medium did not change VEC cell morphology after 72-hours in traditional culture. PolyI:C induced a punctate cell morphology by 24-hours (black box) that increased over 72-hours, microbiome treatment recovered this phenotype (red box). 10x images.

Further microscopic analysis of fluorescent live (Calcein AM [green]) and dead (ethidium homodimer-1 [red]) cell markers was used to quantify VEC+microbiome metabolite-induced cell death. Notably, VECs cultured with L.-dominate VEC-conditioned medium exhibited low levels of cell death (~5.2%) similar to In vitro control conditions (~3%) (Figure 5 – lane 4 vs. 5). Metabolites from the BV VEC conditioned-medium and other experimental controls also showed similar levels of cell death (Figure 5). Conversely, exposure to PolyI:C conditioned medium resulted in significantly higher levels of cell death (~21%) compared to either L.-dominate VEC-conditioned medium (p=0.031) or the control VEC group (p=0.016). Co-treatment with L-dominate VEC-conditioned medium and PolyI:C reduced cell death (12%) compared to PolyI:C alone (21%), though this was not significant (Figure 5 – lane 6 vs. 7). These findings further support that the presence of vaginal microbiome metabolites may have a protective effect on VEC viability and may play a role in mitigating detrimental effects such as TLR agonist-elicited inflammation.

Figure 5. Functional assessment of VEC+Microbiome metabolites effects on cell viability.

VECs cultured with microbiome-conditioned medium after 72-hours showed comparably low levels of cell death (~5.5%) compared to controls (~3%). PolyI:C conditioned medium induced higher levels of cell death (~21%) compared to L. jensenii/L. crispatus conditioned (~5.5%) and control medium (~3%) after 72-hours. PolyI:C +microbiome conditioned medium showed lower levels of cell death (12%) when compared to PolyI:C conditioned medium only (21%). Viability marker – live-Calcein AM – Green. Cell death marker – dead-ethidium homodimer-1- Red. 10x images collected.

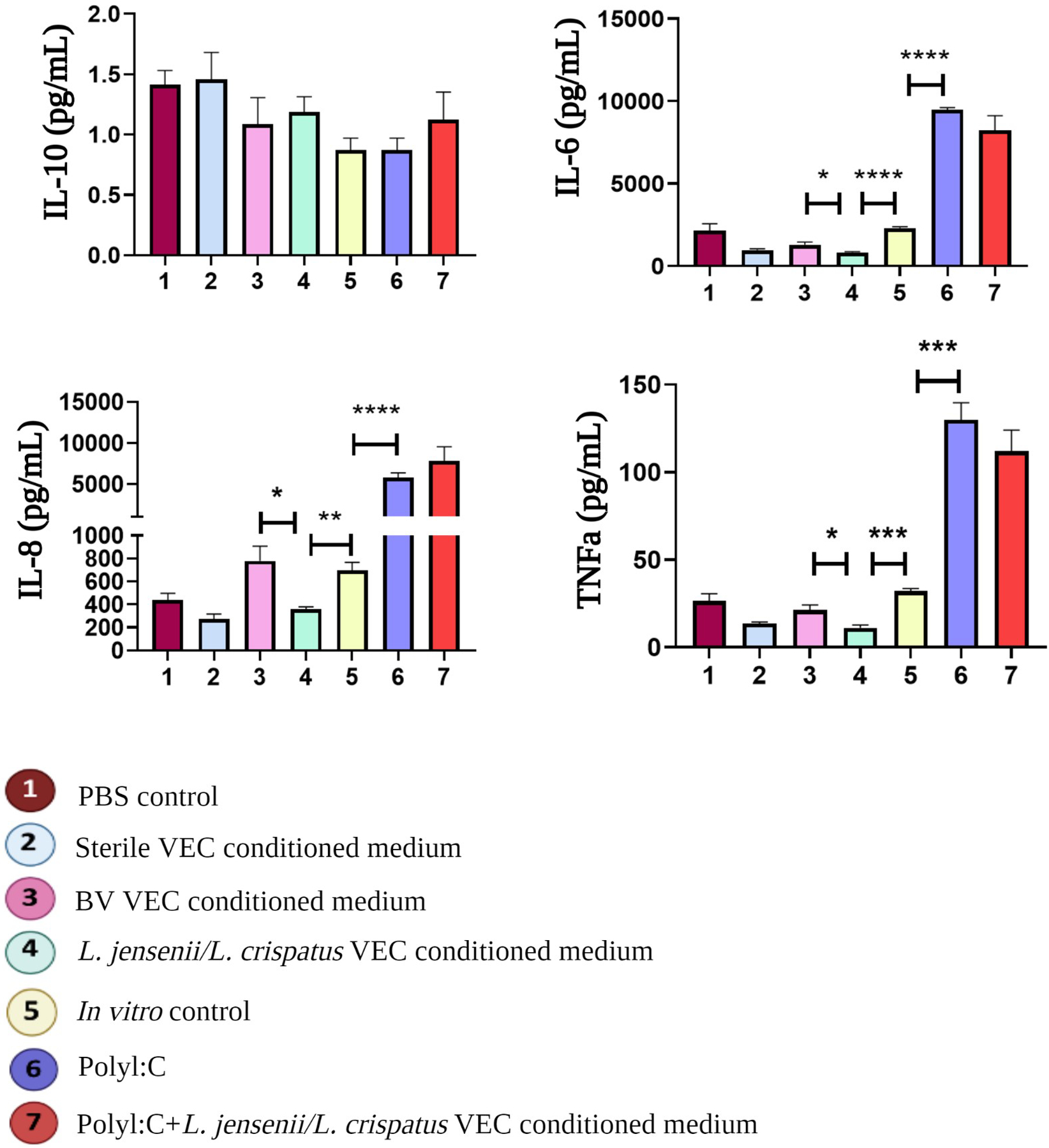

Ex vivo-generated vaginal microbiome metabolites create an anti-inflammatory environment compared to traditional cell culture

To gain a deeper understanding of metabolites role in modulating VEC inflammatory status, medium was collected from (n=3) replicate cultures under each condition after 72-hours of culture and anti-inflammatory interleukin 10 (IL-10) and pro-inflammatory (IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha [TNFα]) cytokine levels were measured (Figure 6). The addition of L.-dominate VEC-conditioned medium induced an anti-inflammatory milieu characterized by a increasing trend in IL-10 (1.19±0.13 vs. 0.87±0.10 pg/mL; p=0.06) and a significant reduction in IL-6 (p<0.0001), IL-8 (p=0.004), and TNFα (p=0.0004) compared to cultures exposed to In vitro control conditions (Figure 6 – lane 4 vs. 5). As expected, BV VEC conditioned-medium induced a pro-inflammatory environment, by elevating levels of IL-6 (p=0.023), IL-8 (p=0.031), and TNFα (p=0.021) when compared to L.-dominate VEC-conditioned medium (Figure 6 – lane 3 vs. 4). PolyI:C also induced a robust pro-inflammatory environment, as evidence by elevated levels of IL-6 (p<0.0001), IL-8 (p=0.0005), and TNFα (p=0.0003) when compared to cultures from the In vitro control (Figure 6 – lane 5 vs. 6). Although not reaching statistical significance, the addition of L.-dominate VEC-conditioned medium induced to PolyI:C treatments exhibited an increasing trend of IL-10 (0.87±0.10 vs. 1.12±0.22 pg/mL) and a decrease trend in IL-6 (9482±124 vs. 8249±872 pg/mL) and TNFα (129.8±9.8 vs. 112±12 pg/mL) (Figure 6 – lane 6 vs. 7). These results highlight the potential beneficial effects of adding metabolites from L.-dominate VEC-conditioned medium into traditional VEC culture to recreate the vaginal tract physiological inflammatory milieu. Again, this is consistent with the past findings when ex vivo VEC cultures were colonized by L.-dominate communities14,22,26.

Figure 6. Cytokine Production of 2D VECs after different treatments.

A cytokine multiplex assay was used to quantify pro-inflammatory (Interleukin [IL]-6, IL-8, Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha [TNFα], and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines. Analysis showed that L. jensenii/L. crispatus metabolites changed the inflammatory milieu by increasing anti-inflammatory IL-10 production and significantly suppressing pro-inflammatory IL-6 (p<0.0001), IL-8 (p=0.004), and TNFα (p=0.0004) when compared to standard culture conditions (lane 4 vs. 5). PolyI:C significantly induced a pro-inflammatory environment noted by high levels of IL-6 (p<0.0001), IL-8 (p=0.0005), and TNFα (p=0.0003) when compared to standard culture conditions (lane 5 vs. 6).

Discussion

Generation of physiologically relevant in vitro vaginal mucosal models is a critical enhancement in women’s health research. Such model systems would provide biologically relevant platforms to understand the human reproductive system, determine mechanistic pathways leading to pathologic onset, and develop and evaluate pre-clinical screening platforms. As current 2D VEC culture systems cannot maintain multi-species vaginal microbiome colonization, here we have completed the first steps to support further development of OOC models of the female genital tract. As an added value, the system we describe provides an alternative approach to modeling cell-cell/cell-microbe interactions through metabolite supplementation. Our findings show that VEC+microbiome metabolites generated from cultures colonized by L.-dominate communities contained fatty acids, nucleic acids, and sugar acids, that are associated with signaling networks contributing to secondary metabolism, anti-fungal, and anti-inflammatory functions indicative of a healthy vaginal microbiome. This profile is consistent with clinical reports of vaginal fluid content1,2,10,15,20,23,27 supporting the utility of the ex vivo/in vitro approach.

The addition of L.-dominate VEC+microbiome metabolites to traditional 2D VEC culture did not affect VECs native cuboidal morphology nor impact cell viability over the 72-hour culture period; however, it did create an anti-inflammatory milieu defined by low pro-inflammatory cytokine levels. Prior studies with ex vivo VEC cultures colonized by selected individual Lactobacilli or communities provided similar outcomes with PolyI:C-induced inflammation mitigation supporting the utility of the metabolites as a surrogate for bacterial colonization22. Using separation techniques, additional mechanistic studies could be performed in this system to identify active fractions and specific metabolites for a variety of biological consequences. Consistent with the current understanding of the relationship between the vaginal mucosa and eubiotic microbiomes, metabolite supplementation in this culture system was beneficial to cell survival and successfully modeled the studied aspects of the vaginal tract microenvironment. Additional studies of the system will be required to fully validate its utility.

In contract, BV+VEC derived metabolites induced pathologic effects and created a pro-inflammatory vaginal milieu associated with the clinical presentations of bacterial vaginosis. We also successfully modeled viral infections using direct treatment of PolyI:C that elicited punctate VEC morphology, cell death and inflammation. Remarkably, when a mixture of L.-dominate VEC+microbiome metabolites and PIC-induced metabolites was added to 2D cultures, these negative effects trended toward mitigation but were not significantly reduced likely due to the supraphysiological effect of PolyI:C that L.-dominate VEC+microbiome metabolites could not overcome. However, these results do highlight the added physiological benefit of VEC+microbiome metabolites supplementation and rationalize their use in traditional 2D culture environments. Similar effects against herpes simplex virus and Zika infections were observed when selected vaginal microbiome communities were cultivated in advance of viral infections in the ex vivo VEC model26 again supporting the utility of the metabolites as surrogates for future OOC development.

An interesting revelation of this study was the presence of ex vivo derived VEC+microbiome metabolites. When compared to sterile ex vivo derived VEC metabolites, L.-dominate VEC+microbiome conditioned supernatants contained some bacterial derivatives (i.e., propionic acid28, palmitic acid29) and others from vaginal cells (i.e., 5-methoxytryptophol30), model the overall vaginal metabolite profile found in vaginal swabs27,31. The vaginal microbiome literature does not document the biologic function of the majority of these compounds, though most could be found in other microbiome related reports (i.e., gut or oral cavity). Surprisingly, sugar acids (i.e., D-arabinonic acid found in food), xenobiotics (i.e., Gabapentin – treatment for vulvodynia and pudenal neuralgia), and aromatic alcohols (i.e., cinnamyl alcohol – cosmetic products) were also identified in our metabolite samples after culture in an ex vivo system. An added potential benefit of the system is the use of clinically collected vaginal swabs to generate personalized vaginal metabolites that can be amplified in advanced ex vivo culture platforms to tailor personalized medical approaches.

Additionally, these data, along with recent findings from vaginal swabs, reveal a longer than expected elimination period for the therapeutic Gabapentin. Gabapentin’s elimination half-life is approximately 6.5 hours through renal excretion with no active metabolites32. Its long-term regional affect within the vaginal tract remains unknown and requires future studies. Regardless, vaginal metabolites have proved their values as in vitro supplements to biomimic the human vaginal-microbiome status, as potential biomarkers for physiology or pathologic states, and useful in studying drug pharmacokinetics.

The innate immune system plays an important role in the female reproductive tract, by providing mechanical and chemical barriers and producing anti-microbial peptides along with pattern recognition receptors33. While the mucosal epithelial cells are involved in the production of chemokines and cytokines, activation of adaptative immunity, and processes such as phacytosis34, a prominent role of L.-dominate microbiome cultures in vivo is its anti-inflammatory effects within the vaginal tract. Here we determine these host-microbiome specific responses are in part induced by metabolites, potentially (E)-4-Coumaric acid35, which is a phenylpropanoid that is known to inhibit TNFα and IL-6 production through suppressing NF-κB pathaways36. In this study, L.-dominate microbiome conditioned medium significantly induced an anti-inflammatory environment and suppressed normal pro-inflammatory cytokine production (i.e., TNFα, IL-8, and IL-6) within traditional VEC cell culture. Confirming the functional activity of the L.-dominate microbiome metabolites, though we can’t say which specific component(s) carried out this cytokine inhibition. Nevertheless, the comparison of standard culture conditions with metabolite treatments is highly promising, indicating that the VEC+microbiome metabolites can effectively reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine production akin to what we see in advanced ex vivo VEC-microbiome co-cultures. Suggesting, this type of baseline metabolite supplementation could be adapted for biological assays to properly determine a stimulant-induced pathologic response in the context of the human vaginal-microbiome environment.

Here for the first time, we examined the utilization of microbial metabolites as a reliable proxy for the vaginal microbiome in traditional VEC culture. These results showed that using the ex vivo VEC system in combination with the 2D culture adds to the overall modelling potential and creates a first step in the development of more complex OOC systems. Unfortunately, direct 2D VEC+microbiome comparisons to our current 2D experiments cannot be conducted due to the lack of produced glycogen/mucin molecules in 2D culture that is a critical food source for bacterial colonization21. Further, the culture medium limits the potential for bacterial colonization and direct cell contact interactions accomplished in the air-liquid interface formats that helps the VEC polarize and stratify14,22,26. To improve reproducibility of these findings large scale cultures of vaginal microbiome metabolites (i.e., generated from one patient or pooled from a common group) would be needed to produce abundant quantities of metabolic supplements for in vitro platforms. Additionally, generation of vaginal microbiome metabolites related to different race of VECs was not assessed in this study, though it should be considered as an extension of this system to represent multiple biodiverse in vitro cultures in the future. The confirmation of the exact role of each metabolic compound supplemented in the VEC culture is still under investigation; however, incorporation of these metabolite supplements into more advanced in vitro models (i.e., 3D printed structures, organoid culture, or OOC platforms) should be investigated to increase the bio-relevance of in vitro systems.

In conclusion, this novel study shows that culture-derived vaginal epithelium and microbiome metabolites can model the in vivo environment and induce functionally relevant cell survival and anti-inflammatory pathways in traditional cell culture. These homeostatic effects are evident in direct host cell-microbe studies37 and could in part be due to indirect metabolite-cell interactions.

Methods

Vaginal epithelial cell and microbiome collection

This study used immortalized vaginal epithelial cells provided by Dr. Richard Pyles38. Original collection of the de-identified surgical tissues or purchased primary cells did not require IRB approval. The collection of the vaginal microbiome was conducted according to a previous study22. Briefly, vaginal swabs were collected from the mid-vaginal wall of healthy women or women clinically diagnosed with BV who had been enrolled and consented under a UTMB IRB-approved study (12–238). Swabs were transported on ice to the research lab where they were aliquoted for cryopreservation, DNA extraction and subsequent analysis by qPCR array22. Bacterial viability of each sample was tested by colonization outcomes in VEC ALI cultures and, in some cases, by inoculation of Mann-Ragosa Sharpe (MRS) broth (BD Falcon) at 37°C for 48-hours to quantify viable titers of Lactobacilli. Aliquots of selected molecularly characterized vaginal communities were stored at −80C for use in these and other studies.

Ex vivo VEC transwell and 2D VEC experiments

Ex vivo system:

Immortalized VEC were plated into transwell inserts as previously described in detail14. Briefly, VEC monolayers were removed with trypsin from culture flasks, counted and then diluted in antibiotic-free Keratinocyte Serum Free Medium (KSFM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) to be added (5×104 cells) to the inner chamber of transwell inserts (Griener Bio-One cups; Monroe, NC, United States), and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2, for 18–24-hours. Apical medium was removed to create an air interface supporting formation of polarized, stratified multilayers that matured for 7 days. Basal medium was replaced every 48-hours (antimicrobial-free KSFM). Three different transplanted microbiomes were included in the experiment design: (1) microbiome dominated by L. crispatus; (2) microbiome dominated by L. jensenii; and (3) bacterial vaginosis (BV) microbiome (dominated by Gardnerella vaginalis and lacking substantial Lactobacilli spp.). At the end of the study, extracted DNAs from each of the VEC/bacterial community co-cultures and from parallel sterile cultures subjected to qPCR array analysis to confirm proper colonization as previously reported14,22,26 (Supplemental Table S1). The basal chamber media was collected, and the apical chamber was with lavaged with 50ul PBS (4% of the overall pooled apical and basal samples).

2D VEC culture:

VEC were maintained in culture flasks with Keratinocyte Serum-Free Growth Medium (KSFM, Gibco). Using trypsin to passage the cells, 50,000 VECs/well were seeded in multiple 24 well-plates until 70% confluency was reached. Then, medium was removed, and the following supplements were added at a 1:1 ratio with fresh VEC media to a standard 2D VEC culture (n=3 per treatment): (1) PBS control with fresh VEC media + 4% PBS; (2) Control group with fresh VEC medium only; (3) Sterile VEC conditioned-medium (apical and basal combined); (4) BV VEC conditioned-medium; (5) Lactobacillus spp. (L. crispatus and L. jensenii combined) VEC conditioned-medium; (6) Poly I:C (0.1mg/mL) as a positive control; and (7) Poly I:C combined with Lactobacillus spp. (L. crispatus and L. jensenii combined) VEC conditioned-medium. The combination of transwell medium was 96% of the medium from the bottom chamber and 4% from the apical chamber that.

Collection of metabolites

PBS was used to lavage the apical chamber and medium was collected from the basal chamber after 48-hours of colonization. Supernatants from the apical and basal chambers were then combined and filtered through a 0.2 μm syringe filter (Thermo Scientific™ Nalgene™ Syringe Prefilter Plus, Waltham, MA, USA) to remove bacteria. The prepared conditioned media were aliquoted to limit freeze thaw effects and frozen at −80C for subsequent analysis and utilization.

Isolation and untargeted mass spec analysis

Sample preparation:

To assess the metabolome of VEC colonized with different microbiomes, combined apical and basal media samples were analyzed by untargeted mass spectrometry. A 50 μl aliquot of each sample (pooled apical and basal media from each condition) was thawed and mixed with 200 μl of ice-cold methanol, vortexed for 5 minutes and then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 12,000 rpm. Using a 0.2 μm membrane (Thermo Scientific™ Nalgene™ Syringe Prefilter Plus, Waltham, MA, USA), the supernatant was filtered and 10 μl was used for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Mass spectrometry protocol – untargeted:

Untargeted liquid chromatography high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry (LC-HRAM) analysis was performed on a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) coupled to a binary pump UHPLC (UltiMate3000, Thermo Scientific). After preparation, samples were maintained at 4 °C before injection. The volume of 10 μL per sample was used for injection. Full MS spectra were obtained at 70 000 resolution (200 m/z) with a scan range of 50–750 m/z. Full MS followed by ddMS2 scans were obtained at 35 000 (MS1) and 17 500 resolutions (MS2) with a 1.5 m/z isolation window and a stepped NCE (20, 40, 60). Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Hypersil Gold 5 μm, 50 mm × 2.1 mm C18 column (Thermo Scientific) maintained at 30 °C using a solvent gradient method. Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid in water. Solvent B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. The gradient method used was 0–1 min (20% B to 60% B), 1–2 min (60% B to 95% B), 2–4 min (95% B), 4–4.1 min (95% B to 20% B), 4.1–5 min (20% B). The flow rate was 0.5 mL min−1. Sample acquisition was performed by Xcalibur (Thermo Scientific). Data analysis was performed with Compound Discoverer 3.1 (Thermo Scientific).

Cell death assay and Microscopy

Cell viability was assessed by Live/Dead cell staining assay according to manufacturer’s protocol (#L3224, Invitrogen, Massachusetts, EUA). Briefly, after 72-hours, the medium was aspirated and the cells were washed with PBS, the staining solution was added (~150ul) and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2. After the staining solution was removed, cell were fixed with 4% Paraformaldehyde for 15 min, and DAPI (NucBlue™ Fixed Cell ReadyProbes™, #R37606, Invitrogen, Massachusetts, EUA) was added for 5 minutes with rocking before removal and replacement with fresh PBS for imaging. Fluorescence micrographs were collected using a Keyence All-in-one Fluorescence BZ-X810 microscope (x4, x10, and x40 magnifications) from three random regions per condition using preset microscope settings. The percentage of live and dead cells were assessed by ImageJ. To check the morphology of the VEC cells under different conditions, images were again captured from three random regions per condition under bright-field microscopy. Settings of brightness and contrast were uniform for all images captured.

Cytokine multiplex analysis

Supernatants from each well of all conditions were collected after 72-hours and analyzed for inflammation by Millipore Multiplex cytokine assay (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, and IL-10 were quantified for each sample in the biological triplicates. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, standard curves were developed with duplicate samples of known quantities of recombinant proteins to allow extrapolation of experimental levels for each target by calculating the standard curve absorbance values by linear regression plot analysis.

Statistics

All data were analyzed using Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). To check the normality of the data the Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted, and Student’s t-test was used to compare the means. P values < 0.05 was considered significant. * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This study was supported by R01HD100729-01S1 (NIH/NICHD) to Dr. Menon. Dr. Richardson is supported by a research career development award (K12HD052023: Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program-BIRCWH; Berenson, PI) from the National Institutes of Health/Office of the Director (OD)/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD). This research was supported by the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch, supported in part by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 TR001439) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability:

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author. Metabolite data is found in the supplemental files.

References

- 1.Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Mar 15 2011;108 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):4680–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X, Lu Y, Chen T, Li R. The Female Vaginal Microbiome in Health and Bacterial Vaginosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:631972. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.631972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis FMT, Bernstein KT, Aral SO. Vaginal Microbiome and Its Relationship to Behavior, Sexual Health, and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Obstet Gynecol. Apr 2017;129(4):643–654. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000001932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehtoranta L, Ala-Jaakkola R, Laitila A, Maukonen J. Healthy Vaginal Microbiota and Influence of Probiotics Across the Female Life Span. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:819958. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.819958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chee WJY, Chew SY, Than LTL. Vaginal microbiota and the potential of Lactobacillus derivatives in maintaining vaginal health. Microb Cell Fact. Nov 7 2020;19(1):203. doi: 10.1186/s12934-020-01464-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verstraelen H, Verhelst R, Claeys G, De Backer E, Temmerman M, Vaneechoutte M. Longitudinal analysis of the vaginal microflora in pregnancy suggests that L. crispatus promotes the stability of the normal vaginal microflora and that L. gasseri and/or L. iners are more conducive to the occurrence of abnormal vaginal microflora. BMC Microbiol. Jun 2 2009;9:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ventolini G, Vieira-Baptista P, De Seta F, Verstraelen H, Lonnee-Hoffmann R, Lev-Sagie A. The Vaginal Microbiome: IV. The Role of Vaginal Microbiome in Reproduction and in Gynecologic Cancers. J Low Genit Tract Dis. Jan 1 2022;26(1):93–98. doi: 10.1097/lgt.0000000000000646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng N, Guo R, Wang J, Zhou W, Ling Z. Contribution of Lactobacillus iners to Vaginal Health and Diseases: A Systematic Review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:792787. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.792787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koumans EH, Sternberg M, Bruce C, et al. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in the United States, 2001–2004; associations with symptoms, sexual behaviors, and reproductive health. Sex Transm Dis. Nov 2007;34(11):864–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318074e565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freitas AC, Chaban B, Bocking A, et al. The vaginal microbiome of pregnant women is less rich and diverse, with lower prevalence of Mollicutes, compared to non-pregnant women. Sci Rep. Aug 23 2017;7(1):9212. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07790-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dos Anjos Borges LG, Pastuschek J, Heimann Y, et al. Vaginal and neonatal microbiota in pregnant women with preterm premature rupture of membranes and consecutive early onset neonatal sepsis. BMC Med. Mar 13 2023;21(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-02805-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deka N, Hassan S, Seghal Kiran G, Selvin J. Insights into the role of vaginal microbiome in women’s health. J Basic Microbiol. Dec 2021;61(12):1071–1084. doi: 10.1002/jobm.202100421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou JZ, Way SS, Chen K. Immunology of Uterine and Vaginal Mucosae: (Trends in Immunology 39, 302–314, 2018). Trends Immunol. Apr 2018;39(4):355. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose WA 2nd, McGowin CL, Spagnuolo RA, Eaves-Pyles TD, Popov VL, Pyles RB. Commensal bacteria modulate innate immune responses of vaginal epithelial cell multilayer cultures. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baldewijns S, Sillen M, Palmans I, Vandecruys P, Van Dijck P, Demuyser L. The Role of Fatty Acid Metabolites in Vaginal Health and Disease: Application to Candidiasis. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:705779. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.705779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Zang Y, Wang C, Fan A, Han C, Xue F. The Interaction Between Microorganisms, Metabolites, and Immune System in the Female Genital Tract Microenvironment. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:609488. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.609488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilhan ZE, Łaniewski P, Thomas N, Roe DJ, Chase DM, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Deciphering the complex interplay between microbiota, HPV, inflammation and cancer through cervicovaginal metabolic profiling. EBioMedicine. Jun 2019;44:675–690. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kero K, Hieta N, Kallonen T, et al. Optimal sampling and analysis methods for clinical diagnostics of vaginal microbiome. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. Feb 2023;42(2):201–208. doi: 10.1007/s10096-022-04545-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma M, Chopra C, Mehta M, et al. An Insight into Vaginal Microbiome Techniques. Life (Basel). Nov 13 2021;11(11)doi: 10.3390/life11111229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang B, Fettweis JM, Brooks JP, Jefferson KK, Buck GA. The changing landscape of the vaginal microbiome. Clin Lab Med. Dec 2014;34(4):747–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahajan G, Doherty E, To T, et al. Vaginal microbiome-host interactions modeled in a human vagina-on-a-chip. Microbiome. Nov 26 2022;10(1):201. doi: 10.1186/s40168-022-01400-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pyles RB, Vincent KL, Baum MM, et al. Cultivated vaginal microbiomes alter HIV-1 infection and antiretroviral efficacy in colonized epithelial multilayer cultures. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e93419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berard AR, Brubaker DK, Birse K, et al. Vaginal epithelial dysfunction is mediated by the microbiome, metabolome, and mTOR signaling. Cell Rep. May 30 2023;42(5):112474. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta P, Singh MP, Goyal K. Diversity of Vaginal Microbiome in Pregnancy: Deciphering the Obscurity. Front Public Health. 2020;8:326. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koizumi Y, Nagase H, Nakajima T, Kawamura M, Ohta K. Toll-like receptor 3 ligand specifically induced bronchial epithelial cell death in caspase dependent manner and functionally upregulated Fas expression. Allergol Int. Sep 2016;65 Suppl:S30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amerson-Brown MH, Miller AL, Maxwell CA, et al. Cultivated Human Vaginal Microbiome Communities Impact Zika and Herpes Simplex Virus Replication in ex vivo Vaginal Mucosal Cultures. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:3340. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ceccarani C, Foschi C, Parolin C, et al. Diversity of vaginal microbiome and metabolome during genital infections. Sci Rep. Oct 1 2019;9(1):14095. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50410-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez-Garcia RA, McCubbin T, Navone L, Stowers C, Nielsen LK, Marcellin E. Microbial Propionic Acid Production. Fermentation. 2017;3(2). doi: 10.3390/fermentation3020021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin M, Zhai R, Xu Z, Wen Z. Production of High-Value Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Using Microbial Cultures. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1995:229–248. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9484-7_15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satué M, Ramis JM, del Mar Arriero M, Monjo M. A new role for 5-methoxytryptophol on bone cells function in vitro. J Cell Biochem. Apr 2015;116(4):551–8. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mirzaei R, Kavyani B, Nabizadeh E, Kadkhoda H, Asghari Ozma M, Abdi M. Microbiota metabolites in the female reproductive system: Focused on the short-chain fatty acids. Heliyon. Mar 2023;9(3):e14562. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chincholkar M Gabapentinoids: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and considerations for clinical practice. Br J Pain. May 2020;14(2):104–114. doi: 10.1177/2049463720912496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheldon IM, Owens SE, Turner ML. Innate immunity and the sensing of infection, damage and danger in the female genital tract. J Reprod Immunol. Feb 2017;119:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amjadi F, Salehi E, Mehdizadeh M, Aflatoonian R. Role of the innate immunity in female reproductive tract. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3:1. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.124626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu H, Liang QH, Xiong XG, et al. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of p-Coumaric Acid, a Natural Compound of Oldenlandia diffusa, on Arthritis Model Rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018:5198594. doi: 10.1155/2018/5198594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin HJ, Choi MS, Ryoo NH, et al. Manganese-mediated up-regulation of HIF-1alpha protein in Hep2 human laryngeal epithelial cells via activation of the family of MAPKs. Toxicol In Vitro. Jun 2010;24(4):1208–14. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roselletti E, Sabbatini S, Perito S, Mencacci A, Vecchiarelli A, Monari C. Apoptosis of vaginal epithelial cells in clinical samples from women with diagnosed bacterial vaginosis. Sci Rep. Feb 6 2020;10(1):1978. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58862-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herbst-Kralovetz MM, Quayle AJ, Ficarra M, et al. Quantification and comparison of toll-like receptor expression and responsiveness in primary and immortalized human female lower genital tract epithelia. Am J Reprod Immunol. Mar 2008;59(3):212–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00566.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author. Metabolite data is found in the supplemental files.