Abstract

The Oncology Grand Rounds series is designed to place original reports published in the Journal into clinical context. A case presentation is followed by a description of diagnostic and management challenges, a review of the relevant literature, and a summary of the authors' suggested management approaches. The goal of this series is to help readers better understand how to apply the results of key studies, including those published in Journal of Clinical Oncology, to patients seen in their own clinical practice.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States with more than half of the patients diagnosed being older than 65 years, and an expected further increase in older adults (OA) diagnosed with this cancer in the coming years as the population ages. Prospective data guiding the management of older patients with metastatic CRC (mCRC) have been limited and treatment decisions for these patients are often guided by chronologic age, crude evaluation of performance status, and extrapolation from trials conducted in younger individuals. Recent evidence from randomized clinical trials specifically designed for OA supports treatment deintensification and dose modification to increase tolerability without compromising efficacy in older, frailer patients with mCRC. Additional studies support the incorporation of geriatric assessment (GA)–driven care to further improve the outcomes of OA with mCRC. Although the use of GA has not been validated in guiding specific treatment selection or modification for OA with mCRC, it provides a comprehensive and objective evaluation of a patient's functional status, comorbidities, risk of potential toxicities, effect on the quality of life, goals of care, and assists with personalizing therapy. With the increase in the number of OA we care for in our practices, it is time to stop extrapolating and define an evidence-based approach for this population that is based on data from prospective elderly specific clinical trials.

Recent evidence supports treatment deintensification and dose modification to increase tolerability for older adults with metastatic colorectal cancer. This manuscript reviews published data of prospective elderly-specific clinical trials, including the recent PANDA study, allowing us to define an evidence-based approach to the care of this patient population.

CASE PRESENTATION

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and osteoarthritis presented with anemia, unintentional weight loss, and a change in bowel movements. On examination, she was alert and oriented with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 1 and mild abdominal discomfort. Laboratory testing revealed iron deficiency anemia and subsequent colonoscopy demonstrated a partially obstructing mass in the sigmoid colon. Biopsy of the mass confirmed adenocarcinoma. Cross-sectional imaging demonstrated liver lesions consistent with metastatic disease, and peritoneal carcinomatosis. Molecular profiling using next-generation DNA sequencing revealed a microsatellite-stable, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative tumor without mutations in KRAS, NRAS, or BRAF.

Her G8 geriatric screening tool score was 11 and a comprehensive geriatric assessment (GA) was subsequently performed. Her Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) combined score was 6, suggesting a low-intermediate risk of toxicity. The Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) chemotherapy toxicity tool predicted intermediate risk for treatment-related toxicity (score 8; 52% risk; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Validated GA Screening Tools

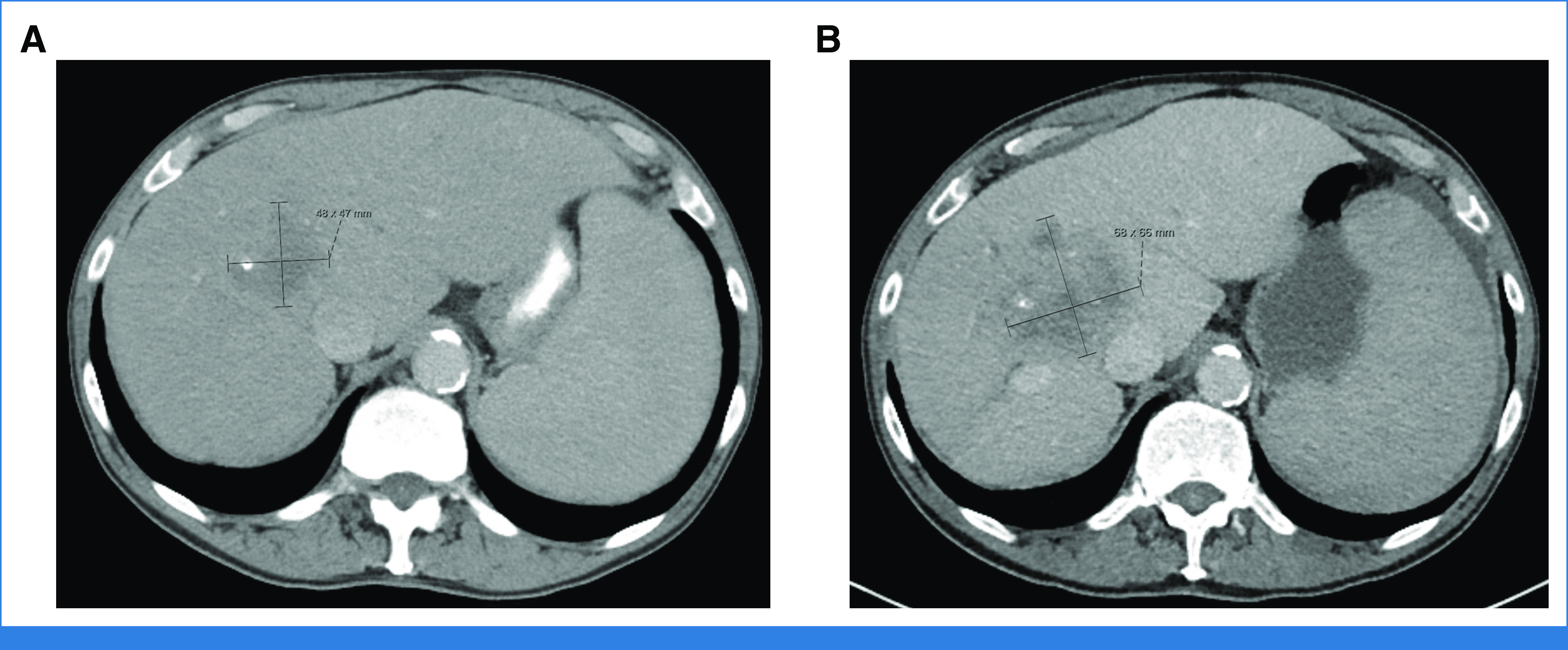

Considering her GA screening tool scores, she was initiated on infusional fluorouracil with leucovorin (5-FU/LV) and bevacizumab. She tolerated treatment well with only mild fatigue (Fig 1).

FIG 1.

Patient imaging. (A) Pretreatment, metastatic liver lesion measuring 4.8 × 4.7 cm. (B) Restaging imaging after 12 cycles of treatment, liver lesion measuring 6.8 × 6.6 cm.

CLINICAL CHALLENGES IN TREATMENT

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer death and the third most common cancer in the United States with most patients diagnosed between age 65 and 84 years.1 As the population ages, a further increase in the number of older adults (OA) diagnosed with CRC is expected.2 However, the optimal management of CRC in this fast-growing population remains unclear. The challenges associated with the care of OA with cancer span across multiple domains that are affected by aging, including comorbidities, impaired functional status and cognition, diminished organ function, and socioeconomic concerns. Despite these challenges, oncologists usually develop treatment plans for their older patients that stem from clinical experience and studies conducted in younger patients. Chronologic age and ECOG PS are commonly used for assessing the appropriateness of treatment in OA with cancer, yet the subjective nature of PS assessment with considerable interobserver variability results in inadequate prediction of treatment tolerance and outcomes in this vulnerable patient population.3 Similarly, chronologic age is a poor predictor of patient outcomes, with significant differences in fitness among patient of similar age warranting very different treatment approaches. As such, a more comprehensive evaluation with geriatric screening tools and assessments is required to understand the overall health status of an OA with metastatic CRC (mCRC) and their risk of a proposed therapy. This is important among OA who often value quality of life (QoL) over longevity, especially if treatment-related toxicities carry a risk of impaired functional status or cognition.4

The challenge in caring for OA with CRC is further complicated by limited prospective data to guide their management and by their under-representation in clinical trials. Although patients older than 70 years represent approximately 40% of the overall population with cancer, a recent analysis showed that only 24% of participants of studies registered by the US Federal Drug Administration and <10% of participants in National Cancer Institute (NCI) studies were in that age category.5 A recent NCI-sponsored Trial Design Working Group called for the urgent need to enhance accrual of OA to cancer clinical trials, address barriers associated with this goal, and promote elderly-specific research to guide the care of this patient population.6 Over the past decade, multiple elderly-specific mCRC clinical trials have been reported and have helped guide the care of our aging patients. The PANDA study publication accompanying this article further adds to this growing body of evidence, which can be immediately incorporated into our routine clinical practice. These data allow us to enter an evidence-based era of caring for our vulnerable OA with mCRC.

SUMMARY OF RELEVANT LITERATURE

Systemic Therapy in Older Adults With mCRC

Palliative treatment of mCRC is based on the use of 5-FU/LV-based doublet chemotherapy combined with a targeted biologic agent. This approach may be challenging for OA, given the risk for higher rates of adverse events (AEs) and decreased tolerability of multiagent chemotherapy (Table 2). Retrospective analyses evaluating the safety and efficacy of doublet chemotherapy with 5-FU/LV plus oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) found similar efficacy outcomes (eg, overall response rate [ORR], progression-free survival [PFS], and overall survival [OS]) in OA with mCRC compared with younger patients with mCRC.7,8 However, safety data were mixed with some studies reporting comparable toxicity and others demonstrating a higher risk of grade ≥three AEs (particularly hematologic) in the older cohort.

TABLE 2.

Elderly-Specific Clinical Trials

MRC FOCUS2 was the first large prospective randomized trial to evaluate dose-reduced single (5-FU/LV or capecitabine) versus dose-reduced doublet chemotherapy (FOLFOX or capecitabine plus oxaliplatin) in frail and elderly patients with untreated mCRC.9 Dose-reduced oxaliplatin-containing regimens improved ORR (13% v 35%; P < .0001) without excess toxicity compared with 5-FU/LV or capecitabine alone. However, this did not translate to improved survival, making the use of dose-reduced oxaliplatin in frail and elderly patients less compelling. Regarding single-agent therapy, this study also supports the use of 5-FU/LV over capecitabine as it was associated with fewer AEs, improved QoL, and similar survival outcomes. Notably, this study met its accrual target early, signaling the need and demand for prospective elderly-specific trials, as well as the feasibility of conducting large-scale studies in this patient population.

Prospective data also support the use of 5-FU/LV plus irinotecan (FOLFIRI) in older patients with mCRC, demonstrating similar tolerability and efficacy as seen in studies with younger patients. In a pooled analysis of four large phase III trials comparing first-line FOLFIRI to 5-FU/LV alone, the addition of irinotecan improved ORR (50.5% v 30.3%; P < .0001) and PFS (hazard ratio [HR], 0.75 [95% CI, 0.75 to 0.92]; P = .0003) without added toxicity among patients age 70 years and older who were enrolled on these trials.10 However, only a trend toward OS benefit with FOLFIRI was seen in the older cohort (HR, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.72 to 1.05]; P = .15). This regimen was also tested prospectively in the FFCD 2001-02 trial, which enrolled patients age 75 years and older with mCRC, and demonstrated a significant improvement in ORR (27.4% v 21.1%; P = .001) with first-line FOLFIRI compared with 5-FU/LV alone.11 However, the rate of grade 3 or higher toxicity was increased by >20% (76.3% v 52.2%) with the addition of irinotecan and there was no statistically significant survival benefit seen with multiagent chemotherapy (PFS, 7.3 v 5.2 months; HR, 0.84 [95% CI, 0.66 to 1.07]; P = .15; OS, 13.3 v 14.2 months; HR, 0.96 [95% CI, 0.75 to 1.24]). An ancillary study using geriatric screening tools found that impaired ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living, and cognitive decline assessed by a Mini-Mental State Examination, were predictive of grade 3-4 treatment-related AEs and hospitalization among elderly patients enrolled on FFCD 2001-02.12

Biologic and Targeted Agents

Standard management of mCRC now includes the combination of chemotherapy with targeted biologic agents on the basis of biomarker testing. RAS and BRAF mutational status is used to guide the choice of targeted therapy with either epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors (eg, cetuximab and panitumumab), or a vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor, bevacizumab. Patients with RAS or BRAF wild-type (WT) tumors benefit from the addition of an EGFR inhibitor to chemotherapy, while those with RAS-mutated tumors benefit from the addition of bevacizumab.

The use of targeted biologic agents in the older population was first evaluated in the phase III AVEX trial, which randomly assigned 280 patients with untreated mCRC age 70 years and older deemed frail/ineligible for doublet chemotherapy to capecitabine with or without bevacizumab regardless of RAS status.13 The addition of bevacizumab was associated with superior PFS (9.1 v 5.1 months; P < .0001), a trend toward OS benefit (20.7 v 16.8 months; P = .18), and higher treatment-related toxicity (40% v 22%). JCOG1018 RESPECT, a randomized phase III elderly-specific trial, compared first-line capecitabine or 5-FU/LV plus bevacizumab with or without oxaliplatin in patients age 70 years and older with mCRC regardless of RAS mutational status. Notably, 95% of patients enrolled on this trial were older than 75 years.14 Preliminary results revealed an improved ORR (47.7% v 29.5%) with oxaliplatin without a significant survival benefit (median OS [mOS], 19.7 v 21 months; HR, 1.058). The addition of oxaliplatin was also associated with increased toxicity (grade 3 or higher hematologic toxicity: 24% v 15%) and decreased QoL. These prospective elderly-specific trials provide evidence-based data to support the use of 5-FU/LV and bevacizumab for frontline therapy in vulnerable or frail OA with mCRC regardless of RAS mutational status.

Recently, results of the randomized elderly-specific phase III SOLSTICE trial were presented with approximately 45% of enrolled patients in both arms older than 75 years. The study evaluated bevacizumab plus capecitabine or trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD), an approved third-line agent, in patients with untreated mCRC who were deemed ineligible for doublet or triplet chemotherapy.15,16 No significant difference in median PFS (mPFS; 9.3 v 9.4 months) or mOS (18.59 v 19.74; HR, 1.06) was found between treatment arms and no new safety signals were identified, indicating that FTD plus bevacizumab is another treatment option in older and/or frail patients regardless of RAS status.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the efficacy of EGFR inhibitors (cetuximab or panitumumab) for the treatment of RAS WT tumors. Age-focused subgroup analyses (<70 v >70 years) of the phase II Valentino trial, which studied the use of maintenance therapy among patients with RAS WT mCRC of panitumumab alone or in combination with 5-FU/LV after induction therapy, did not demonstrate a significant difference in ORR, survival, toxicity, or QoL.17 The benefit of adding anti-EGFR therapy to doublet chemotherapy was evaluated retrospectively in a large pooled analysis of seven randomized trials with a total of nearly 2,000 patients. Although safety and efficacy were found to be similar among fit OA enrolled on these trials and their younger counterparts, the addition of an anti-EGFR agent did not significantly improve PFS or OS among older patients compared with doublet chemotherapy alone (OS, 24.7 v 17.6 months; HR, 0.77; P = .092; PFS, 9.1 v 8.7 months; HR, 0.85; P = .287).18 The most effective and safest approach to incorporate anti-EGFR therapy to the treatment of OA and specifically vulnerable patients with RAS WT mCRC remains unknown.

In this issue, Lonardi et al19 present final results from the PANDA study, a multicenter, randomized phase II trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of panitumumab with modified FOLFOX (arm A, n = 91) versus modified 5-FU/LV (arm B, n = 92) in OA with untreated RAS/BRAF WT mCRC. Patients age 70-75 years with an ECOG PS ≤ 2 or patients older than 75 years with an ECOG PS ≤ 1 were eligible; approximately 60% of patients were older than 75 years. Patients received up to 12 cycles of chemotherapy with panitumumab, followed by panitumumab maintenance. PFS was the primary end point in this noncomparative pick-the-winner trial design, and ORR, R0 resections, and OS were secondary end points. The study met its primary end point with a mPFS of 9.6 (arm A) versus 9.0 months (arm B). Additionally, there was an improved ORR with oxaliplatin (69% arm A v 52% arm B; P = .0182) without a significant difference in mOS (23.5 v 22.0 months; HR, 1.00; P = .805). Unplanned post hoc comparison between study arms to measure survival did not demonstrate a significant difference in PFS (HR, 1.08; P = .611). Subgroup analysis demonstrated that patients >75 years old had improved OS with arm B and those age 70-75 years old had improved OS with arm A. There were no new safety signals and, as expected, the oxaliplatin-containing arm had increased rates of hematologic, gastrointestinal, and neurologic toxicity.

Data from the PANDA trial also demonstrated that patients with right-sided tumors receiving 5-FU/LV plus panitumumab had very poor outcomes, particularly in terms of PFS. This finding is in line with results from the phase III PARADIGM trial, which randomly assigned patients to modified FOLFOX plus panitumumab or bevacizumab. Although this was not an elderly-specific trial, approximately 60% of patients who were eligible for this study were age 65-79 years with an ECOG PS of 0-1.20 The study demonstrated improved OS with panitumumab over bevacizumab in patients with left-sided tumors (37.9 v 34.3 months; HR, 0.82; P = .03), as well as in the overall population (36.2 v 31.3 months; HR, 0.84; P = .03). Subgroup analysis of right-sided tumors failed to demonstrate a difference in survival between panitumumab and bevacizumab (mOS, 20.2 v 23.2 months; HR, 1.09), suggesting the survival benefit in the overall population was driven by patients with left-sided tumors.

Geriatric Assessment

The aging process results in biologic changes to multiple domains that directly affect patients' fitness and the ability to tolerate anticancer therapy. Therefore, GAs are necessary to thoroughly evaluate these domains and assist in optimizing a patient's health, treatment tolerance, and outcomes. The GA tools provide a multidisciplinary assessment of comorbidities, functional and nutritional status, cognition, and psychosocial well-being. These assessments are useful in determining a patient's appropriateness for treatment and risk of associated toxicities and in identifying modifiable factors that might be missed during routine clinical evaluation. The GAIN and GAP70+ trials validated the benefit of GA-guided oncologic care for OA with cancer, demonstrating improved treatment tolerance with a 10%-20% decrease in the rate of grade 3 or higher treatment-related toxicities with multidisciplinary GA-driven interventions.21,22

Despite the robust evidence to support GA-guided care for OA with cancer, this approach is infrequently used in practice because of limited time and staffing.23 GA screening tools and chemotherapy toxicity prediction models have been developed and validated to simplify and expedite evaluations of OA. For instance, the G8 screening tool identifies patients who require and may benefit from a more comprehensive GA, while the CRASH and CARG Chemotherapy toxicity tools predict the risk of treatment-related toxicity3,24,25 (Table 1). These tools have been shown to predict outcomes and prognosis, as well as chemotherapy tolerance, for the general population of OA with cancer. However, they do not replace the full GA, which remains the gold standard for a comprehensive evaluation of OA with cancer.26,27

Prospective elderly-specific trials are gradually incorporating GA into their design and are thus shaping the evolving landscape of treating OA with cancer. The phase II PANDA trial included a baseline G8 screening tool as a stratification factor in analyzing treatment tolerance and outcomes.19 Unplanned post hoc analyses did not demonstrate a difference in toxicity, PFS, ORR, or OS between treatment arms on the basis of age or G8 screening scores. Approximately 69% of patients had a G8 screening score ≤14, indicating that most patients were frail. When all patients were analyzed regardless of treatment arm, patients with G8 scores >14 had improved survival compared with those with scores ≤14 (mPFS, 10.9 v 9.2 months; HR, 0.72; P < .001; mOS, 32.8 v 18.7 months; HR, 0.54; P < .001), suggesting a prognostic value to this screening tool. This is in line with previous publications demonstrating the prognostic value associated with G8.28 The phase III GERICO trial used the G8 screening tool to identify vulnerable patients with stage II-IV CRC age 70 years and older, who were then randomly assigned to geriatric interventions (eg, polypharmacy management, physical and/or nutritional interventions) or routine care.29 GA-based care increased the number of vulnerable OA who completed planned treatment (45% v 28%) and were associated with a lower likelihood of dose reductions compared with the standard-of-care arm.

The CRASH tool was also included in the baseline assessment of patients on the PANDA study as a toxicity prediction tool. CRASH scores were well balanced between groups with most patients (approximately 80%) falling in the medium-low or medium-high risk groups. In an unplanned post hoc analysis, no significant correlation was found between the CRASH score and survival. Interestingly, this score was not found to be predictive of treatment-related toxicities in either treatment arm. As this scale was developed in the general OA cancer population, it may lack disease-specific features that contribute to and predict treatment tolerance. Recently, a breast cancer–specific scale has been developed for prediction of chemotherapy risk for OA with early-stage disease.30 As we refine the evaluation, approach to care, and outcomes of OA with cancer, we hope to develop additional disease-specific assessments for OA accounting for patient- and disease-related factors in predicting risk/benefit ratio of proposed treatments.

OUR APPROACH TO MANAGEMENT

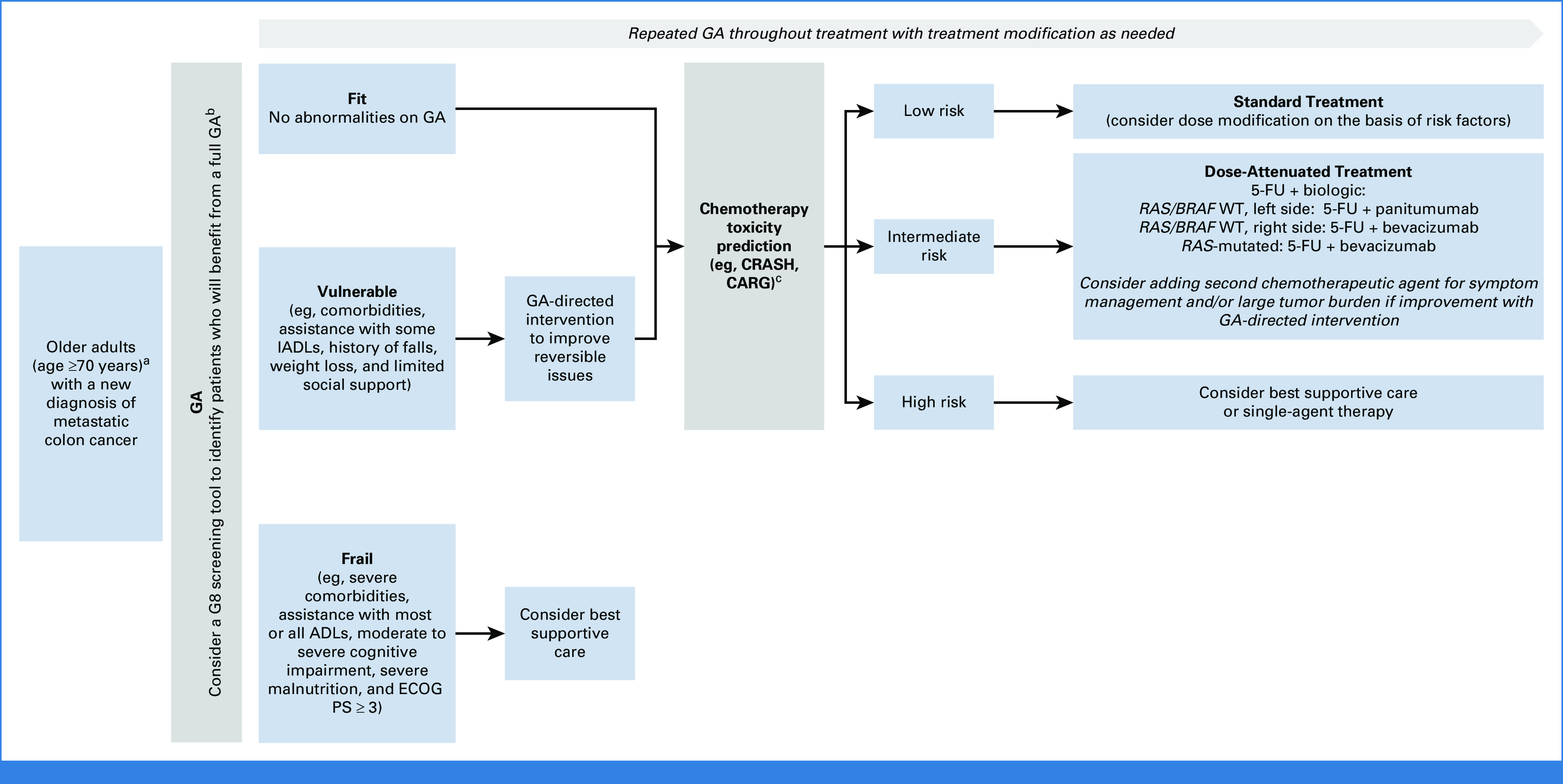

Because of the aging population, the number of OA with CRC seen in our clinics will continue to rise in the coming years. As such, we strongly support incorporating GA into the initial evaluation and using it to guide treatment formulation and inform shared decision making with the patient. The use of geriatric screening tools (eg, G8, CARG, and CRASH) can identify patients who would benefit from a more comprehensive evaluation and provide data to guide treatment approaches. These quick screening tools require minimal resources and can easily be incorporated into a busy practice's patient evaluation process (Fig 2).

FIG 2.

Suggested algorithm for treating older patients with metastatic colorectal cancer on the basis of geriatric assessment and molecular biomarkers. aAll patients who are being considered for treatment require molecular profiling of their tumor to determine RAS/BRAF status, as well as MMR testing. bComprehensive list of GA tools is available in published guidelines by the NCCN, ASCO.24,25 cCancer and CARG Toxicity Tool,3 CRASH.23 5-FU, fluorouracil; ADL, activities of daily living; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; CARG, Aging Research Group Chemotherapy; CRASH, Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; GA, geriatric assessment; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MMR, mismatch repair; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; WT, wild-type.

On the basis of available data, most approved therapies for mCRC have demonstrable clinical benefit without additional toxicity in fit OA compared with their younger counterparts. We generally reserve the addition of oxaliplatin or irinotecan for fit OA on the basis of GA and those who have a large tumor burden and/or symptomatic disease, understanding that this intensified treatment may carry improved response rates without a clear survival benefit. When using these regimens for OA, a stop-and-go strategy is appropriate as treatment breaks allow time for recovery from chemotherapy, limit cumulative toxicity, and improve QoL.31

Doublet chemotherapy is more challenging in vulnerable or frail patients for whom we recommend combining fluoropyrimidines with targeted therapy. This approach is supported by the AVEX and SOLSTICE studies demonstrating benefit for the combination of capecitabine or FTD and bevacizumab, respectively. It is now further supported by the PANDA data showing benefit for the addition of an EGFR inhibitor to chemotherapy in the first-line setting for OA with RAS/BRAF WT mCRC. The investigators of the PANDA study should be commended for conducting the first biomarker-driven elderly-specific trial in mCRC and truly personalizing therapy to the patient and the biology of the tumor. This study provides support for personalized treatment of OA with RAS WT mCRC in the front-line setting with fluoropyrimidines plus panitumumab for left-sided tumor or bevacizumab for right-sided cancers. Ultimately, patients' goals of care, geriatric abnormalities in function, cognition and social support, comorbid conditions, and risk of treatment-related toxicities are critical factors that influence the treatment approach for each individual patient.

CLINICAL DISCUSSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Our patient was initially treated based on data from the AVEX trial, which provided the strongest level of evidence for 5-FU/LV and bevacizumab regardless of molecular profiling results. At the time of disease progression, her overall functional, nutritional, and cognitive status remained stable. On the basis of preliminary data from the PANDA trial that were available at that time, she was transitioned to 5-FU/LV plus panitumumab with stable disease after six cycles. Her skin toxicity has been controlled with topical steroids and oral antibiotics.

The landmark studies discussed above provide insight and guidance into the risks and benefits of these therapies for OA with mCRC, as well as the role of treatment deintensification and dose attenuation to improve tolerability. They provide more comprehensive and clinically applicable information than unplanned post hoc analyses of large studies that enroll patients of all ages. The inclusion of frail and vulnerable real-world patients who are not candidates for our standard doublet chemotherapy in these studies provides optimal data to guide clinicians in the care of this patient population. Although more recent trials have included some GAs and definitions of frailty, additional studies are needed to clearly define these frailty criteria and validate their use for treatment selection in the care of OA with mCRC. Future prospective elderly-specific trials should aim to elucidate which GA tool(s) can most accurately guide treatment selection, dose modifications, and predict toxicity in patients with this cancer. Obtaining concurrent QoL and full GA data in these studies will also be critical in personalizing treatments for OA through more informed shared decision making.

Efrat Dotan

Honoraria: Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Helsinn Therapeutics, Incyte, Taiho Pharmaceutical, G1 Therapeutics

Research Funding: Incyte (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Relay Therapeutics (Inst), Zymeworks (Inst), NGM Biopharmaceuticals (Inst), Ipsen (Inst), Gilead Sciences (Inst), Lutris (Inst), Theradex (Inst), Kinnate Biopharma (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

See accompanying Article, p. 5263

SUPPORT

Supported by cancer center grant (3 P30 CA006927) (Comprehensive Cancer Center Program at Fox Chase).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: All authors

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Evidence-Based Care of Older Adults With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Insights From Landmark Clinical Trials

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Efrat Dotan

Honoraria: Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Helsinn Therapeutics, Incyte, Taiho Pharmaceutical, G1 Therapeutics

Research Funding: Incyte (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Relay Therapeutics (Inst), Zymeworks (Inst), NGM Biopharmaceuticals (Inst), Ipsen (Inst), Gilead Sciences (Inst), Lutris (Inst), Theradex (Inst), Kinnate Biopharma (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. : Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 72:7-33, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. : Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 70:145-164, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. : Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 29:3457-3465, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, et al. : Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med 346:1061-1066, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sedrak MS, Freedman RA, Cohen HJ, et al. : Older adult participation in cancer clinical trials: A systematic review of barriers and interventions. CA Cancer J Clin 71:78-92, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Germain SD, Mohile SG: Preface: Engaging older adults in cancer clinical trials conducted in the National Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Network: Opportunities to enhance accrual. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2022:107-110, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folprecht G, Cunningham D, Ross P, et al. : Efficacy of 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy in elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A pooled analysis of clinical trials. Ann Oncol 15:1330-1338, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg RM, Tabah-Fisch I, Bleiberg H, et al. : Pooled analysis of safety and efficacy of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin administered bimonthly in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:4085-4091, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seymour MT, Thompson LC, Wasan HS, et al. : Chemotherapy options in elderly and frail patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (MRC FOCUS2): An open-label, randomised factorial trial. Lancet 377:1749-1759, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folprecht G, Seymour MT, Saltz L, et al. : Irinotecan/fluorouracil combination in first-line therapy of older and younger patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: Combined analysis of 2,691 patients in randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 26:1443-1451, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aparicio T, Lavau-Denes S, Phelip JM, et al. : Randomized phase III trial in elderly patients comparing LV5FU2 with or without irinotecan for first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (FFCD 2001-02). Ann Oncol 27:121-127, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aparicio T, Jouve J-L, Teillet L, et al. : Geriatric factors predict chemotherapy feasibility: Ancillary results of FFCD 2001-02 phase III study in first-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer in elderly patients. J Clin Oncol 31:1464-1470, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham D, Lang I, Marcuello E, et al. : Bevacizumab plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in elderly patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer (AVEX): An open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 14:1077-1085, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamaguchi T, Takashima A, Mizusawa J, et al. : A randomized phase III trial of mFOLFOX7 or CapeOX plus bevacizumab versus 5-FU/l-LV or capecitabine plus bevacizumab as initial therapy in elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: JCOG1018 study (RESPECT). J Clin Oncol 40:10, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andre T, Falcone A, Shparyk Y, et al. : Trifluridine-tipiracil plus bevacizumab versus capecitabine plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer ineligible for intensive therapy (SOLSTICE): A randomised, open-label phase 3 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 8:133-144, 2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falcone A, Shparyk YV, Moiseenko FV, et al. : Overall survival results for trifluridine/tipiracil plus bevacizumab vs capecitabine plus bevacizumab: Results from the phase 3 SOLSTICE study. J Clin Oncol 41:3512, 2023. 37071834 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raimondi A, Fucà G, Leone AG, et al. : Impact of age and gender on the efficacy and safety of upfront therapy with panitumumab plus FOLFOX followed by panitumumab-based maintenance: A pre-specified subgroup analysis of the VALENTINO study. ESMO Open 6:100246, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papamichael D, Lopes GS, Olswold CL, et al. : Efficacy of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor agents in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer ≥ 70 years. Eur J Cancer 163:1-15, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lonardi S, Rasola C, Lobefaro R, et al. : Inital panitumumab plus fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin or plus fluorouracil and leucovorin in elderly patients with RAS and BRAF wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: The PANDA trial by GONO foundation. J Clin Oncol 41:5263-5273, 2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe J, Muro K, Shitara K, et al. : Panitumumab vs bevacizumab added to standard first-line chemotherapy and overall survival among patients with RAS wild-type, left-sided metastatic colorectal cancer. JAMA 329:1271, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li D, Sun CL, Kim H, et al. : Geriatric assessment-driven intervention (GAIN) on chemotherapy-related toxic effects in older adults with cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 7:e214158, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohile SG, Mohamed MR, Xu H, et al. : Evaluation of geriatric assessment and management on the toxic effects of cancer treatment (GAP70+): A cluster-randomised study. Lancet 398:1894-1904, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dale W, Williams GR, MacKenzie AR, et al. : How is geriatric assessment used in clinical practice for older adults with cancer? A survey of cancer providers by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. JCO Oncol Pract 17:336-344, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellera CA, Rainfray M, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, et al. : Screening older cancer patients: First evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann Oncol 23:2166-2172, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Extermann M, Boler I, Reich RR, et al. : Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: The Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score. Cancer 118:3377-3386, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dotan E, Walter LC, Beechinor R, et al. : NCCN Guidelines® insights: Older adult oncology, version 1.2023. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw, 2023 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. : Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol 36:2326-2347, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez-Tapia C, Paillaud E, Liuu E, et al. : Prognostic value of the G8 and modified-G8 screening tools for multidimensional health problems in older patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer 83:211-219, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lund CM, Vistisen KK, Olsen AP, et al. : The effect of geriatric intervention in frail older patients receiving chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: A randomised trial (GERICO). Br J Cancer 124:1949-1958, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magnuson A, Sedrak MS, Gross CP, et al. : Development and validation of a risk tool for predicting severe toxicity in older adults receiving chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 39:608-618, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tournigand C, Cervantes A, Figer A, et al. : OPTIMOX1: A randomized study of FOLFOX4 or FOLFOX7 with oxaliplatin in a stop-and-go fashion in advanced colorectal cancer—A GERCOR study. J Clin Oncol 24:394-400, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]