Abstract

Emerging adults are at an increased risk for trauma exposure, both interpersonal and non-interpersonal, which often occurs within a social context. How an individual interacts with this context may heighten or buffer against their risk for trauma. Social goal orientation represents individual differences that characterize how an individual navigates their social environment. These orientations fall along the two interacting dimensions, Agency and Communion. In a community sample (N=274; 55% female, average age = 18.9) of young adults, we sought to examine the role that these two types of social goals, both uniquely and in interaction with one another, may play in interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma risk. Because men and women are at differential risk for trauma, we also examined the impact of gender on these associations. Findings revealed that social goal orientations are linked to trauma exposure in ways that differ depending on the type of trauma, interpersonal or non-interpersonal. Moreover, these processes differed for men and women. Whereas a high Communal Orientation was associated with decreased exposure to all trauma, for both women and men, Agentic Orientation was associated with an increased number of interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma. For men, agency and communion interacted, suggesting that the extent to which an agentic orientation may be risky or protective for interpersonal trauma depends strongly on communal orientation. These findings provided initial evidence for the role social goal orientation may play as a risk or protective factor for trauma exposure.

Introduction

Emerging adulthood (ages 18–25; Arnett, 2000), is a period marked by heightened vulnerability for trauma exposure and its many associated deleterious outcomes (Breslau et al., 1999; Kessler, 2000; Ogle et al., 2013; Singer et al., 1995). Trauma is a heterogeneous phenomenon. Within this heterogeneity, two types of trauma categories that are composed of individual traumatic events have been identified as particularly important, interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma. Interpersonal traumas involve other people (e.g., child abuse, partner violence); whereas non-interpersonal traumas have not been perpetrated by another (e.g., natural disaster, car accidents) (Thege et al., 2017; Kessler et al., 1994; Kessler et al., 2005). Each type of trauma shows unique associations with harmful outcomes. Interpersonal trauma in particular being linked to more severe psychological outcomes, including higher rates of PTSD, higher levels of emotion dysregulation, greater interpersonal difficulties (Allistic et al., 2014; Breslau et al., 1999; Dorahy et al., 2009; Fischer et al., 2016; Kolk et al., 2005). Importantly, these two types of trauma may also be predicted by distinct risk factors (Stein et al, 2002; Kendler et al., 1993). An understanding of how and for whom these factors confer risk for or even protection against trauma can inform intervention efforts.

The Social Context of Trauma Risk.

Trauma often occurs with and around other people. This is true not only for interpersonal trauma, which by definition involves another person, but also for non-interpersonal trauma, as a substantial portion of these events – particularly those in young adulthood - occur in a social context (Breslau, 1999; McLaughlin et al., 2013). How a person navigates their social environment may play a critical role in whether someone is exposed to trauma, and in the kinds of trauma they are most likely to experience (Breslau, 1999; Koenen et al., 2007; Milan et al., 2013; Gil, 2015). At present, the role of these social-interpersonal factors in trauma risk is poorly understood.

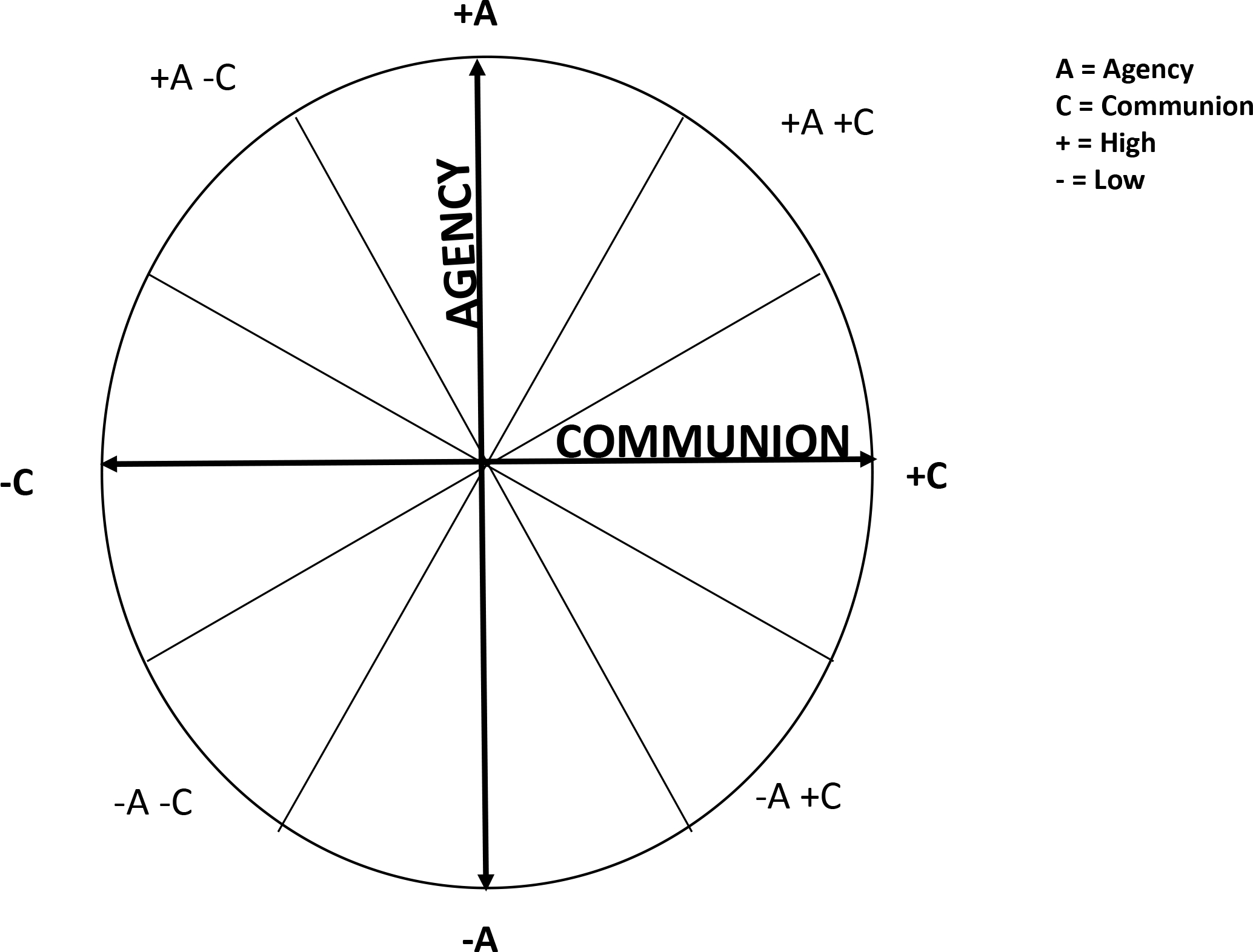

Social goal orientation theory offers a framework for considering trauma risk (Locke, 2000). According to this theory, social goal orientation is an individual-difference variable that characterizes how individuals approach interactions with other people. Conceptualized as a circumplex (see Figure 1), these goal orientations fall along the orthogonal, interacting dimensions of (1) Agency (an orientation toward power, dominance, and mastery in social interactions) and (2) Communion (orientation toward intimacy, union, and solidarity in social interactions) (Locke, 2003; Wright et al., 2012). Each orientation may be associated with trauma risk in its own way. One possibility is that those with a strong Agentic orientation may be prone to conflict, or to engaging in risk behavior in order to establish dominance over or status with others (i.e., drinking heavily or hazardous driving) which would increase their risk for a number of non-interpersonal trauma events. In contrast, a strong Communal orientation may lead someone to be drawn into risky social contexts, and be more vulnerable to peer influences that may compel engagement in risk behaviors (e.g., risk-taking; sexual risk; Allen et al., 2014; Trucco et al., 2011; Read et al., Manuscript in Preparation). These domains could also be protective. High Agentic Orientation may lead individuals to be better equipped to assert their own self-interests and to execute self-protection, whereas those higher in Communal Orientation may make use of stronger social connections to protect against harm (e.g., Coker et al., 2002; Bernard et al., 2019). Implications for prevention would be different depending on the specific interpersonal orientations. Yet whether and how these orientations may confer risk or protection for trauma has not been examined.

Figure 1. Conceptual depiction of the social goals circumplex, with the agentic and communal vectors interacting.

Balancing Agency and Communion.

A critical feature of the social goal orientation model is that it considers the domains of both agency and communion both uniquely and together, as they interact with one another (reference Figure 1). This is relevant to trauma risk, as research suggests that a balance of these two orientations is protective (Allen, 2014). Individuals high on both agentic and communal goals can advocate for their needs while still maintaining important social connections. In contrast, an imbalance of these goals - the combination of high communion and low agency in particular - has been linked to risk behavior (Ojanen et al. 2012; Ojanen and Findley-Van Nostrand 2014). This is because low agentic orientation, in the context of strong communal orientation, may lead someone not only to be drawn into risky contexts, but less likely to assert personal needs and protections within these contexts (Allen & Loeb, 2015).

Social Goal Orientation and Differential Trauma Risk.

Another unanswered question in the literature is whether social goal orientation might be linked to susceptibility for particular types of traumatic events. For example, one possibility is that individuals with strong orientations toward agency, but not toward communion, may eschew social norms, and engage in high risk behaviors that increase the likelihood of non-interpersonal trauma (e.g., accidents). Alternatively, strong orientation toward communion but not agency may bring risk for interpersonal traumas, as concerns for maintaining relationship and connection may override perceptions about personal safety (Yeater, 2010; Livingston et al., 2007). No studies have examined whether social goal orientation is linked to specific trauma types. We explored this possibility in the present study.

Gender, Interpersonal Goal Orientation, and Trauma Risk.

There are gender differences in trauma exposure, with men at an increased risk for both initial trauma and for re-exposure (Kessler et al., 1995; Kilpatrick et al., 2013; Tolin & Foa, 2006; Street & Dardis, 2017). Further, there are differences in the specific types of traumatic events that men and women experience (Street & Dardis 2017; Gehrke & Violanti, 2006). Whereas women are more likely to be exposed to sexual assault, men are more likely to be exposed to other interpersonal traumas (e.g., physical assault, combat, or threats of violence; Freedman et al, 2002; Breslau et al., 1999) and also to non-interpersonal traumas, such as motor vehicle accidents or natural disasters (Kessler, 1995).

Social goal orientation may help to understand these gender differences. Though there is substantial individual variation, men often tend or are socialized toward characteristics consistent with an agentic orientation (e.g., aggression, dominance; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Donaldson 1993; Maccoby, 1990). In contrast, women tend to be or are encouraged to be more agreeable, and other-oriented (Lindsey, 2015; Maccoby, 1990) which may be reflected in a stronger communal orientation. Relatedly, data suggest that though women may value agency, they place more emphasis on maintaining group cohesion even as they pursue agentic interests. Thus, the expression of social values may be different for men and women (Maccoby, 1990). This in turn would have implications for trauma risk. Yet the question of whether there are gender differences in social goal orientations, and how this may affect trauma risk has not been studied.

The Present Study

Social goal orientation is a theoretical formulation that characterizes how individuals engage with their social environments. Though this formulation can be used to shed light on who is at greatest risk for different types of trauma exposure, and how risk processes may differ between men and women, no studies have conducted such examinations. Addressing these questions would be valuable for trauma prevention efforts. Accordingly, this was the objective of this study. To accomplish this, we first examined the unique prediction of interpersonal vs. non-interpersonal trauma by social goal orientation across genders, and then tested whether social goal orientation effects on trauma exposure varied by gender. Based on work from the social development literature (Allen, 2014), we hypothesized that a balance of agentic and communal orientations would be protective. Specifically, we hypothesized that those showing a strong balance of Agentic and Communal goal orientations would report lower interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma. We based this on prior literature which has shown that this goal orientation to be protective against risky behavior more broadly. Research on social goal orientation in relation to trauma has been scarce, and thus we forwarded no specific predictions regarding how combinations of agency and communion might be particularly risky. Lastly, based on prior literature regarding gender socialization (Lindsey, 2015; Maccoby, 1990) we posited an interaction between social goal orientation and gender, and thus we sought to test this in our analyses. However, this test was exploratory, as previous work has not examined how gender might impact social goal orientation.

Methods

Participants.

The current study used a sample from a larger longitudinal study examining risk factors associated with the initiation and escalation of substance use (Colder et al., 2018; Meisel & Colder, 2017; Trucco et al., 2014). A community sample of 387 families (1 caregiver, 1 child) was recruited in (Erie County, New York), using random-digit dialing (RDD) with both listed and unlisted telephone numbers. Telephone recruiters contacted families and provided a description of the study, eligibility requirements, and compensation procedures. The main inclusion criterion for family recruitment was having a child of the age 11 or 12 years old. Parents or guardians provided consent while adolescents provided assent to partake in the study. Exclusion criteria included non-English speaking, and mental or physical disability that would prevent the completion of lab-based tasks that were part of the larger study objectives. The participation rate for the study was 52.4%, which is well within the acceptable range of population-based studies (Galea & Tracy, 2007). The longitudinal project included 9 annual waves of data collection. Retention across the nine years was excellent, ranging from 90%–96%.

The current study used data (N=274) from the eighth wave of the longitudinal project, as participants were entering young adulthood. The average age was 18.9. The sample consisted of an even split on gender (55% female) and included a majority of white, non-Hispanic individuals (83.1%), as well as, African American (9.1%), Hispanic (2.1%), and Asian (1.0%) individuals. The median family income was $70,000 and ranged from $1,500 to $500,000.

Procedures.

Annual assessments were completed at project research offices. After informed consent and assent procedures, young adults completed assessments, which consisted of both laboratory tasks as well as questionnaires assessing a wide range of family, peer, and individual level risk and protective factors for trauma, alcohol use, and social goals. Assessments took approximately 2.5 to 3 hours. Participants were compensated $135 for their participation. Because by Wave 8 some of the young adult participants had moved out of the area, procedures were available for online completion at home instead of in the research office. However, the majority of the sample (>80%) completed the study in the project research offices. All procedures were approved by the University at Buffalo’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures.

Social goal orientation.

The Circumplex Scales of Interpersonal Values (CSIV; Locke, 2000) was administered and is adapted from the IGI-CR (The Interpersonal Goals Inventory for Children Revised (Trucco et al., 2013). The measure includes 8 scales and 31 items representing the Interpersonal Goals Circumplex. All 31 items contain the prompt, “When with your peers, in general how important is it to you that…?” Response options included a 5-point scale from 0 (not at all important to me) to 4 (extremely important to me). The CSIV is comprised of 8 octants containing 4 items each, and together these octants represent all parts of the agency-communion circumplex. Vector scores were computed from the 8 octants to represent agentic and communal goals using formulas commonly used by social goals researchers (Locke 2003; Ojanen et al. 2005). High scores on the agentic vector correspond to valuing and appearing dominant and independent. High scores on the communal vector correspond to valuing solidarity and belongingness. Good internal reliability was determined for both the agency vector (α = 0.83) and communion vector (α = 0.81). The range of the agency vector was −3.19 – 8.23 and the range of the communion vector was −6.54 – 8.27.

Trauma.

The Trauma History Screen (THS; Carlson et al., 2011) asks participants about lifetime exposure to a variety of interpersonal and non-interpersonal traumatic events with 14 items, beginning with the prompt “Please select the response that best describes whether this happened to you.” The response options include (0) did not ever happen, (1) happened 1 time, (2) happened 2 times, (3) happened 3 or more times. An item was considered as an interpersonal trauma item if the event was directly and, presumably, purposely perpetrated by another individual (e.g., physical assault), and as a non-interpersonal trauma item if the event was not perpetrated by another (e.g., natural disaster). The interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma variables were formed by creating a sum of the response options (0–3) for each trauma event in the specified category, interpersonal (potential range 0–9) or non-interpersonal (potential range 0–18). Thus, these variables reflected degree or “dose” of each type of trauma exposure. Of the 14 items, five were removed for the following possible reasons: only one individual endorsed experiencing the event (1 item), the item was not specific enough to determine if it was potentially traumatic (2 items), or a question that specifically asked about childhood since the focus was on emerging adulthood (2 items) (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Trauma History Screen items and endorsements.

| Trauma History Screen | ||

| Interpersonal Items | Frequency | Percent of Sample |

|

| ||

| Hit or kicked as an adult | 17 | 6.25 |

| Forced sexual contact as an adult | 10 | 3.64 |

| Attacked with a gun, knife or weapon | 13 | 4.72 |

|

| ||

| Non-Interpersonal Items | Frequency | Percent of Sample |

|

| ||

| Car, boat, train, airplane accident | 42 | 15.16 |

| A really bad accident at work or home | 30 | 10.83 |

| Natural disaster | 15 | 5.41 |

| Sudden death of a loved one | 128 | 46.55 |

| Seeing someone die suddenly or bed badly hurt or killed | 59 | 21.46 |

| Sudden move or loss of home and possessions | 27 | 9.85 |

Data Analysis.

Data were examined for distributional properties (see Table 2). To examine the association of social goal orientation with trauma exposure (interpersonal/non-interpersonal) across genders, a multiple group path analysis was conducted using MPlus Version 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2014). This analytic approach was employed in order to simultaneously estimate and compare regression coefficients for male and female groups of participants (Kline, 2016). Assessing equivalence across the groups involved testing sets of parameters in an increasingly restrictive manner through hierarchical ordering of nested models, where each model constrains more parameters than the preceding model (Arbuckle, 2012). To demonstrate if groups are equivalent, we compared three nested models (i.e., unconstrained, path coefficients constrained to equal, covariances constrained to be equal). These analyses are hierarchical; if a previous constraint resulted in a fit decrement, subsequent, more restrictive models of equivalence were not tested.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, by gender (male N = 123, female N = 151).

| Overall Sample (N = 274) | Male Sample (N = 123) | Female Sample (N = 151) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Agency | 0.27 | 1.53 | 0.54 | 1.53 | 0.04 | 1.50 |

| Communion | 3.24 | 2.16 | 2.66 | 1.89 | 3.72 | 2.24 |

| Overall Trauma | 1.84 | 2.44 | 2.05 | 3.01 | 1.68 | 1.81 |

| Interpersonal Trauma | 0.22 | 0.79 | 0.38 | 1.10 | 0.09 | 0.35 |

| Non-Interpersonal Trauma | 1.62 | 1.97 | 1.67 | 2.21 | 1.59 | 1.74 |

We tested two path models. The first specified the continuous vectors of Agency, Communion, and the interaction of Agency and Communion as predictors of the interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma in the full sample (Diagram 1). In the second analysis, we applied multiple group analysis to explore the influence of gender (see Diagram 2). All independent variables were centered for the analyses. If an interaction effect was significant, we explored the simple slopes by determining the effects on trauma one standard deviation above and below the mean for agency and communion (Aiken & West, 1991). In addition, to the simple slopes we also characterized the interaction effect using the Johnson-Neyman technique (Bauer & Curran, 2005, p. 374; Hayes & Matthes, 2009, p. 924). This technique mathematically derives “regions of significance” for the conditional effect of the interaction. This depicts the values within the range of the moderator for which the association between the independent variable and dependent variable are statistically different from zero. This is an improvement on the “pick-a-point” approach suggested by Aiken and West (1991, p. 16) and commonly used for probing interactions, as that approach can be less precise, particularly in skewed data sets.

Diagram 1. Path analysis of total sample predicting interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma.

Note. Only significant paths shown.

Diagram 2. Path analysis utilizing the multiple group analysis to understand the association for males and females separately.

Note. Only significant paths shown with the solid line representing the male analysis and the dotted line representing the female analysis.

The majority of variables were normally distributed, but there was evidence for non-normality for the trauma variables (Skewness > 2.0, Kurtosis >3.0) (see Reference Table 2 for descriptive statistics and Table 3 for correlations). Therefore, maximum likelihood robust estimator (MLR) was used.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix for males and females.

| Male Sample | |||||

| Variable | Agency | Communion | Interpersonal Trauma | Non-Interpersonal Trauma | Total Trauma |

|

| |||||

| Agency | 1.00 | ||||

| Communion | 0.04 | 1.00 | |||

| Interpersonal Trauma | 0.275 | −0.20 | 1.00 | ||

| Non-interpersonal Trauma | 0.214 | −0.26 | 0.65 | 1.00 | |

| Trauma | 0.26 | −0.26 | -- | -- | 1.00 |

|

| |||||

| Female Sample | |||||

| Variable | Agency | Communion | Interpersonal Trauma | Non-Interpersonal Trauma | Total Trauma |

|

| |||||

| Agency | 1.00 | ||||

| Communion | 0.37 | 1.00 | |||

| Interpersonal Trauma | 0.10 | −0.25 | 1.00 | ||

| Non-interpersonal Trauma | 0.10 | −0.26 | 0.08 | 1.00 | |

| Trauma | 0.12 | −0.30 | -- | -- | 1.00 |

Results

Descriptives.

The average number of potentially traumatic events experienced by those in our sample was 1.84. Non-interpersonal trauma was reported by 172 (62.1%) of participants in the sample, and interpersonal trauma was reported by 40 (approximately 12%). The number of non-interpersonal traumas ranged from 0–13 (M=1.67, SD = 1.97), while participants experienced between 0–6 interpersonal traumas (M= 0.22, SD = 0.79). Consistent with prior research (Kessler et al., 1995; Kilpatrick et al., 2013; Tolin & Foa, 2006), men reported more interpersonal trauma exposure (t (270) = 3.15, p = .002). As expected (Locke, 2000), men reported higher levels of Agentic values (t (272) = 2.71, p = .007) while women reported higher levels of Communal values (t (272) = −4.17, p = .001).

Combined (male, female) sample.

Our first model examined how Agency, Communion, and the interaction of agency and communion were associated with interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma for the combined sample (e.g., men and women). In this just-identified model, Agency showed a positive effect (β = 0.20, p =.03) while Communal orientation showed a negative effect (β = −0.14, p = .005) with interpersonal trauma. The interaction was not statistically significant for interpersonal trauma (β = −0.15, p = .06). When non-interpersonal trauma was the outcome, we again observed a negative direct effect for Communion (β = −0.21, p = .001), but we observed no significant effects for Agency (β = 0.11, p = .07) and no interaction effect (β = −0.09, p = .21).

Multiple group analysis.

The unconstrained model was just-identified and produced a model chi-square of 0. Constraining path coefficients to be equal for men and women yielded a significant increment in the model fit (Δ χ2 (10) = 40.89, p < .01), suggesting sex differences. Examination of modification indices in the constrained model suggested differences in path coefficients for Agency, Communion and the interaction of the two goal orientations in predicting both interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma. Hence, we examined the unconstrained model and did not explore constraining covariances.

Prediction of Trauma Exposure: Men

Interpersonal Trauma.

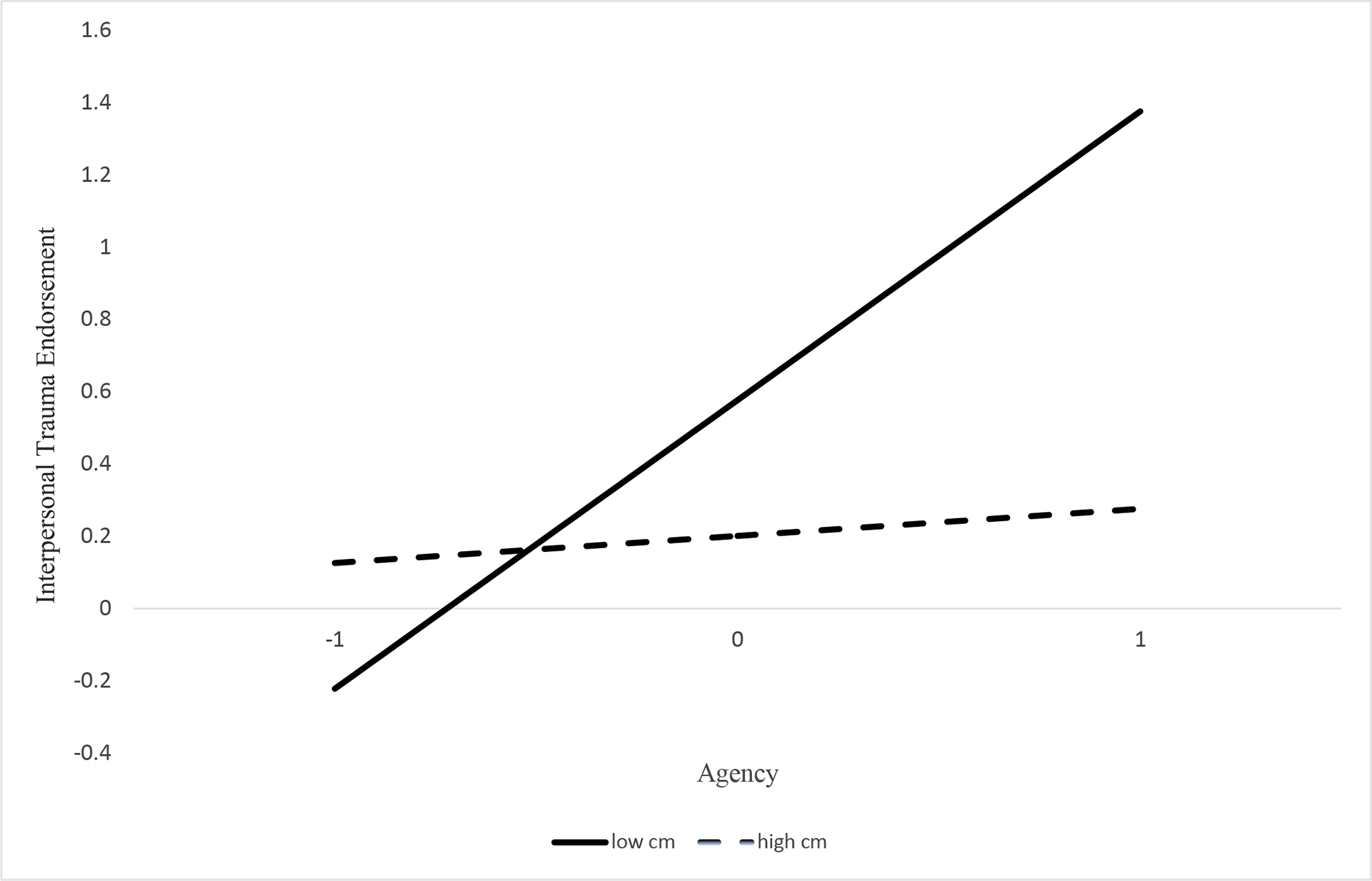

We observed a significant effect for Agentic Orientation on interpersonal trauma; a higher level of Agentic Orientation was related to greater exposure (β = 0.30, p = .006). The effect of Communal Orientation was not significant (β = −0.11, p = .11). Findings also revealed a significant Agency X Communion interaction for men (β = −0.32, p = .003). Simple slope analysis (see Figure 2) showed that Agency was positively related to interpersonal trauma at low (β = 0.80, p = .01) but not high (p = .47) levels of communal social goals. A higher exposure to interpersonal trauma events was observed at high levels of Agentic orientation and low levels of Communal orientation. Our data suggest that when Agentic goals are not balanced by Communal goals, men are more likely to experience trauma. Put another way, Communal goal orientation appears to act as a buffer of the effects of Agentic orientation on interpersonal trauma for men. As can be seen in the Johnson-Neyman plot analysis in Figure 3, the relationship between interpersonal trauma and Agentic orientation is strongest when Communal orientation is low and remains significant until Communal orientation is slightly above average at which point higher Communal orientation ceases to significantly influence risk.

Figure 2. Simple Slope Analysis of the Regression of Social Goals on Interpersonal Trauma in the Male Sample.

Note. Graph depicting simple slope analysis of the interaction of agency and communion in the male sample predicting interpersonal trauma. High communion and high agency are 1 standard deviation above the mean and low communion and low agency is 1 standard deviation below the mean. Agency and Communion are standardized for this analysis.

Figure 3. Johnson-Neyman Plot.

Note. Johnson-Neyman Plot depicting the regions of significance for the effect of communion on the relationship of agency to interpersonal trauma for men. The effect of communion as a moderator becomes non-significant after levels of communion are slightly above average.

Non-Interpersonal Trauma.

There was a main effect for Communion (β = −0.21, p = 0.003), such that low levels of Communion were associated with non-interpersonal trauma. The main effect for Agentic orientation also was significant, but positive. That is, strong Agentic orientation was associated with greater exposure to non-interpersonal traumas (β = 0.23, p = .005). There was no significant interaction for exposure to non-interpersonal trauma (β = −0.20, p = .06).

Prediction of Trauma Exposure: Women

Social goals showed the same pattern of association across interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma for woman. That is, there was a first-order effect of Communion. Low levels of Communal orientation were associated with high levels of both interpersonal (β = −0.23, p = .001) and non-interpersonal trauma (β = −0.27, p = .002). There was no statistically significant effect of Agency for female participants for either of the trauma types (β = 0.01, p = .91; β = 0.003, p = .97). Additionally, the interactive effect for Agency and Communion was non-significant for both interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma exposure (β = −0.06, p = .49; β = 0.02, p = .82, respectively).

Discussion

Individual-level social goal orientations guide how a person navigates their social environment, and this has the potential to make social goals highly relevant to trauma exposure. Yet, to our knowledge, no studies have sought to understand how such orientations may relate to trauma risk. This study represents the first effort to delineate these pathways, and to examine the role that gender plays in these associations. We tested these associations in a sample of young adults, a population at higher risk for trauma. Our findings demonstrate that social goal orientations are linked to trauma exposure in ways that vary, depending on the type of trauma, interpersonal or non-interpersonal. Moreover, the processes by which social goals are associated with trauma exposure can be distinct for men and women. Though temporal ordering cannot be determined from this cross-sectional design, from the patterns of association that we observed we might imagine that a high communal orientation was protective for both men and women, regardless of trauma type. In contrast, agentic orientation was associated with more exposure to both types of trauma, but this was only for men, and communal goal orientation moderated this association. We elaborate on these findings below.

Social Goal Orientations and Trauma Risk

Communion.

For both men and women in our sample, a communal orientation was associated with lower trauma exposure. Prior work has shown communal orientation to be linked to engagement in prosocial behaviors and as such, those with stronger communal orientations may develop stronger support from and connection to others (Ojanen et al., 2012; Bernard et al, 2019). One possibility is such interpersonal connections may buffer against trauma by providing a network of others who will intervene to prevent trauma from occurring, or who will keep a watchful eye to alert someone to risk (e.g., Banyard, 2008; Bennett & Banyard, 2014). Also, those with a stronger communal orientation may be more likely to use interpersonal resources to avoid harm (e.g., resolving conflict rather than fighting, seeking a ride from someone rather than driving while intoxicated, etc.). In any event, our data suggest that the buffering effect of communal orientation is true for both interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma exposure. Further, though much has been made about gender differences in propensity for social connection and social support (Lindsey, 2015; Maccoby, 1990; Donaldson, 1993), the fact that we observed effects for communal orientation in both women and (through moderation) men suggests that the protective potency of connectedness and closeness is not limited to one gender or another.

Agency.

In contrast to our findings regarding communal social goal orientation, the association between agentic goal orientation and trauma exposure was more dependent on gender. For men in our sample, agentic orientation was associated with more exposure to both types of trauma, whereas agentic orientation did not play such a role for women. As with communion, there was no unique effect for type of trauma. Agency often is viewed as a desirable characteristic (Cheng et al., 2013; Diener et al., 1999). Yet, some data have linked agency to hazardous outcomes (Trucco et al., 2011; Markey et al., 2005), including both physical and relational aggression (Ojanen et al., 2012), as well as increased substance use (Meisel & Colder, 2017), all of which can increase risk for trauma exposure. Our findings add to this literature, and underscore that agentic orientation –at least for men – is associated with greater trauma exposure, especially when not buffered by a high communal orientation. While it is notable that agency was only found to have a negative impact for men in our sample, it is plausible that men and women express agentic values differently. For example, for men, agency might be expressed in a way that looks like aggression, and it is this presentation that is more likely to be associated with trauma experiences. The delineation of the specific processes by which agency confers risk will be an important next step for future investigations.

Communion by Agency Interactions

We posited that agency and communion would interact to be protective based on work from the field of social development suggesting that balance between these orientations is important for positive adjustment. That is, balancing the interests of both self (agency) and others (communion) in interpersonal contexts is adaptive. We modeled this balance by examining the interaction of these two domains. Interestingly, whereas we observed no significant interaction between agentic and communal values for the women in our sample, we did see this for men. Notably, this interaction was specific to interpersonal trauma exposure, whereby a more communal orientation appeared to buffer the effect of agency. In contrast, men with a high agentic orientation and low communal orientation had the highest exposure to interpersonal trauma. Moreover, our application of the Johnson-Neyman technique revealed that the degree of communal orientation is critical for determining how or when agentic orientation is associated with interpersonal trauma. Specifically, we showed that communal orientation is related in important ways to trauma, such that at low levels it’s associated with risk and at moderate levels may modulate risk. When the level of communal orientation is too high, the effect disappeared. Thus, there seems to be a threshold in our data for when communal orientation is protective or beneficial. These findings are consistent with previous data from Allen (2014), demonstrating that a balanced orientation between agency and communion might help to avoid harmful outcomes. In light of the heightened severity of consequences associated with interpersonal trauma exposure compared to other forms of trauma, this interaction that we observed for men is of potential clinical significance. We turn to some of the clinical implications of our findings next.

Clinical Implications.

Our study highlights the utility of fostering communal values for both men and women, as these values appear to buffer against trauma risk. These data suggest that interventions that focus not just on individuals, but on communities (e.g., “bystander” interventions, or group norms-based interventions; Carey et al., 2012; Coker et al., 2016; Cronce & Larimer, 2011; Neighbors et al., 2015; Palm-Reed et al., 2015; Teeters et al., 2015) to foster a shared sense of care and protection are a promising avenue. Of particular note were our findings that low communal orientation – in the context of high Agency, is perhaps especially hazardous for men. This suggests that interventions may also want to take levels of agency into account – at least for interventions targeted to men.

As noted, interpersonal trauma exposure is linked to particularly detrimental outcomes (Allistic et al., 2014; Breslau et al., 1999; Dorahy et al., 2009; Fischer et al., 2016; Kolk et al., 2005), and as a category is most common in men, with the exception of sexual victimization (Freedman et al, 2002; Breslau et al., 1999). Our findings indicate a risk profile that may be implicated in this trauma type, the combination of low communal orientation, in combination with high agency. Future interventions that aim to address this profile on the individual level will want to focus on encouraging communal values (e.g., developing social skills, cultivating social support, and learning how to utilize support offered by others), perhaps especially for those men identified as having strong Agentic orientations.

Limitations and Future Directions

Foremost among the limitations of this study is the cross-sectional design that cannot address questions of directionality or temporal ordering among variables of interest. Social goal orientation is typically considered to be a more stable facet of interpersonal functioning, first emerging in childhood. Therefore, this orientation would be expected to precede traumatic events occurring in young adulthood. Still, it is possible that trauma exposure instead influenced social goal orientations. For example, exposure to traumatic experiences may result in distrust for others and a decrease in communal values. Longitudinal work is needed to better capture how social goal orientation and trauma may unfold in relation to one another over time. Second, we did not assess trauma contexts - in particular, whether they were social in nature. Studies that consider socio-contextual and other peritraumatic characteristics of traumatic events will help to shed further light on these associations. Our findings did not provide evidence that agentic values confer risk for women in our sample. Low endorsement of interpersonal trauma exposure, particularly by the women in this sample, may have limited our ability to predict this outcome. Examining social goals within samples at high risk for trauma may help clarify this issue. Finally, the interpretation of our findings is predicated on the notion that social goal orientations will influence behavioral outcomes. Yet, the mechanisms that facilitate values into behaviors is still unknown (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977; Bem, 1972; Locke, 2000). A direction for future research will be to seek to understand what it is about social goals that leads to risk and protection (e.g., social support, aggressive behavior, etc.).

Despite these limitations, the current study offers novel and valuable information about how social goal orientation may contribute to trauma vulnerability, and gender differences in these risk paths. Findings can be used to inform interventions so that they may be geared toward the cultivation balanced agentic and communal orientations, and to teaching specific skills around the implementation of those orientations when navigating risky contexts.

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, & Fishbein M (1977). Attitude–behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Allen JP, Chango J, & Szwedo D (2014). The adolescent relational dialectic and the peer roots of adult social functioning. Child Development, 85(1), 192–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, & Loeb EL (2015). The autonomy-connection challenge in adolescent–peer relationships. Child Development Perspectives, 9(2), 101–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allistic E, Zalta AK, van Wesel F, Larsen SE, Hafstad GS, Hassanpour K, & Smid GE (2014). Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(5), 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle J (2012). AMOS 21 reference guide. Amos Development Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL (2008). Measurement and correlates of prosocial bystander behavior: The case of interpersonal violence. Violence and Victims, 23(1), 83–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ & Curran PJ (2005) Probing Interactions in Fixed and Multilevel Regression: Inferential and Graphical Techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40(3), 373–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem D (1972). Self-perception theory. In Berkowitz L (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology. New York: Academic, 6, 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, Banyard VL, & Garnhart L (2014). To act or not to act, that is the question? Barriers and facilitators of bystander intervention. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(3), 476–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard NK, Yalch MM, Lannert BK, & Levendosky AA (2019). Interpersonal style and PTSD symptoms in female victims of dating violence. Violence and Victims. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC, Peterson EL, Lucia VC. (1999). Psychological Medicine. 29(4):813–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice; (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EB, Smith SR, Palmieri PA, et al. Development and validation of a brief self-report measure of trauma exposure: The Trauma History Screen. (2011). Psychological Assessment. 23(2);463–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Elliott JC, Garey L, & Carey MP (2012). Face-to-face versus computer-delivered alcohol interventions for college drinkers: A meta-analytic review, 1998 to 2010. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 690 –703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JT, Tracy JL, Foulsham T, Kingstone A, Henrich J. (2013). Two ways to the top: Evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 104, 103–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Bush HM, Fisher BS, Swan SC, Williams CM, Clear ER, & DeGue S (2016). Multi-college bystander intervention evaluation for violence prevention. American journal of preventive medicine, 50(3), 295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, & Davis KE (2002). Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 11(5), 465–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Frndak S, Lengua LJ, Read JP, Hawk LW, & Wieczorek WF (2018). Internalizing and externalizing problem behavior: A test of a latent variable interaction predicting a two-part growth model of adolescent substance use. Journal Of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(2), 319–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW, & Messerschmidt JW (2005). Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859. [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, & Larimer ME (2011). Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Research & Health, 34, 210 –221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, & Smith HL (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson M (1993) What Is Hegemonic Masculinity?, Theory and Society, Special Issue: Masculinities, 22(5), 643–657. [Google Scholar]

- Dorahy MJ, Corry M, Shannon M, MacSherry A, Hamilton G, McRobert G, & Hanna D (2009). Complex PTSD, interpersonal trauma and relational consequences: Findings from a treatment-receiving Northern Irish sample. Journal Of Affective Disorders, 112(1–3), 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Dölitzsch C, Schmeck K, Fegert JM, & Schmid M (2016). Interpersonal trauma and associated psychopathology in girls and boys living in residential care. Children and Youth Services Review, 67, 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman SA, Gluck N, Tuval-Mashiach R et al. (2002). Gender Differences in Responses to Traumatic Events: A Prospective Study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15(5), 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea Sandro & Tracy Melissa. (2007). Participation Rates in Epidemiologic Studies. Annals of epidemiology. 17. 643–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke A, & Violanti JM (2006). Gender differences and posttraumatic stress disorder: The role of trauma type and frequency of exposure. Traumatology, 12(3), 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Gil S (2015). Personality and trauma-related risk factors for traumatic exposure and for posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS): A three-year prospective study. Personality And Individual Differences, 831–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Matthes J Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 924–936 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. (1993). A twin study of recent life events and difficulties. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 50, 589–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder: The burden to the individual and to society. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(Suppl 5), 4–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, & Nelson CB (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52(12), 1048–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62 (6), 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, & Friedman MJ (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD pre- valence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(5), 537–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 4th ed. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Moffitt TE, Poulton R, Martin J, & Caspi A (2007). Early childhood factors associated with the development of post-traumatic stress disorder: results from a longitudinal birth cohort. Psychological medicine, 37(2), 181–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey LL (2011). Gender roles: A sociological perspective (5th ed.). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JA, Hequembourg A, Testa M, & VanZile-Tamsen C (2007). Unique Aspects of Adolescent Sexual Victimization Experiences. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(4), 331–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke K (2003). Status and solidarity in social comparison: Agentic and communal values and vertical and horizontal directions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 619–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke K (2000). Circumplex scales of interpersonal values: Reliability, validity, and applicability to interpersonal problems and personality disorders. Journal of Personality Assessment. 75(2):249–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE (1990). Gender and relationships. A developmental account. The American psychologist, 45(4), 513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markey PM, Markey CN, & Tinsley B (2005). Applying the interpersonal circumplex to children’s behavior: Parent-child interactions and behaviors. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 549–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Hill ED, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2013). Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(8), 815–830.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel SN, & Colder CR (2017). Social goals impact adolescent substance use through influencing adolescents’ connectedness to their schools. Journal Of Youth And Adolescence, 46(9), 2015–2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan S, Zona K, Acker J, & Turcios-Cotto V (2013). Prospective risk factors for adolescent PTSD: sources of differential exposure and differential vulnerability. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 41(2), 339–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (2014). Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition. Muthén & Muthén [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Rodriguez LM, Rinker DV, Gonzales RG, Agana M, Tackett JL, & Foster DW (2015). Efficacy of personalized normative feedback as a brief intervention for college student gambling: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 500–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle CM, Rubin DC, & Siegler IC (2013). The impact of the developmental timing of trauma exposure on PTSD symptoms and psychosocial functioning among older adults. Developmental Psychology, 49(11), 2191–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojanen T, & Findley-Van Nostrand D (2014). Social goals, aggression, peer preference, and popularity: Longitudinal links during middle school. Developmental Psychology, 50(8), 2134–2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojanen T, Grönroos M, & Salmivalli C (2005). An Interpersonal Circumplex Model of Children’s Social Goals: Links With Peer-Reported Behavior and Sociometric Status. Developmental Psychology, 41(5), 699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojanen Tiina & Findley-Van Nostrand, Danielle & Fuller Sarah. (2012). Physical and Relational Aggression in Early Adolescence: Associations with Narcissism, Temperament, and Social Goals. Aggressive behavior. 38. 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm Reed KM, Hines DA, Armstrong JL, & Cameron AY (2015). Experimental evaluation of a bystander prevention program for sexual assault and dating violence. Psychology of Violence, 5(1), 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus AL, Lukowitsky MR, Wright AG, & Eichler WC (2009). The interpersonal nexus of persons, situations, and psychopathology. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(2), 264–265. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Colder C (2018). Daily Activities and Young Adult Experiences Survey Project. R01 AA026105. [Google Scholar]

- Singer MI, Anglin TM, Song LY, Lunghofer L. Adolescents’ Exposure to Violence and Associated Symptoms of Psychological Trauma. JAMA. 1995;273(6):477–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street AE, & Dardis CM (2018). Using a social construction of gender lens to understand gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 66, 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeters JB, Borsari B, Martens MP, & Murphy JG (2015). Brief motivational interventions are associated with reductions in alcohol-impaired driving among college drinkers. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 76(5), 700–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thege BK, Horwood L, Slater L, Tan MC, Hodgins DC, & Wild TC (2017). Relationship between interpersonal trauma exposure and addictive behaviors: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, & Foa EB (2006). Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 132(6), 959–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Colder CR, Wieczorek WF, Lengua LJ, & Hawk LJ (2014). Early adolescent alcohol use in context: How neighborhoods, parents, and peers impact youth. Development And Psychopathology, 26(2), 425–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Colder CR, & Wieczorek WF (2011). Vulnerability to peer influence: a moderated mediation study of early adolescent alcohol use initiation. Addictive behaviors, 36(7), 729–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Wright AG, & Colder CR (2013). A revised interpersonal circumplex inventory of children’s social goals. Assessment, 20(1), 98–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk BA, Roth S, Pelcovitz D, Sunday S, & Spinazzola J (2005). Disorders of Extreme Stress: The Empirical Foundation of a Complex Adaptation to Trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AG, Pincus AL, & Lenzenweger MF (2012). Interpersonal development, stability, and change in early adulthood. Journal of Personality, 80(5), 1339–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeater EA, Treat TA, Viken RJ, & McFall RM (2010). Cognitive processes underlying women’s risk judgments: Associations with sexual victimization history and rape myth acceptance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(3), 375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]