Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a formidable disease due to its complex pathogenesis. Macrophages, as a major immune cell population in IBD, are crucial for gut homeostasis. However, it is still unveiled how macrophages modulate IBD. Here, we found that LIM domain only 7 (LMO7) was downregulated in pro-inflammatory macrophages, and that LMO7 directly degraded 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) through K48-mediated ubiquitination in macrophages. As an enzyme that regulates glycolysis, PFKFB3 degradation led to the glycolytic process inhibition in macrophages, which in turn inhibited macrophage activation and ultimately attenuated murine colitis. Moreover, we demonstrated that PFKFB3 was required for histone demethylase Jumonji domain-containing protein 3 (JMJD3) expression, thereby inhibiting the protein level of trimethylation of histone H3 on lysine 27 (H3K27me3). Overall, our results indicated the LMO7/PFKFB3/JMJD3 axis is essential for modulating macrophage function and IBD pathogenesis. Targeting LMO7 or macrophage metabolism could potentially be an effective strategy for treating inflammatory diseases.

Key words: Inflammatory bowel disease, Macrophage, LMO7, Ubiquitination, PFKFB3, JMJD3

Graphical abstract

Infection-triggered LMO7 degrades PFKFB3 through K48-mediated ubiquitination, which leads to the glycolytic process inhibition in macrophages, thus suppressing the expression of JMJD3, and finally regulating the macrophage polarization.

1. Introduction

The mucosal immune system, especially the intestine, as the first line of defense against potential pathogens and commensal microorganism invasion, needs to deal with the large number of commensal bacteria that have co-evolved with vertebrates1. However, inappropriate immune responses against these substances are now believed to be the cause of several common diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), affecting millions of people worldwide2. However, because the pathogenesis of IBD is poorly understood, there are currently no proven effective treatments. Macrophages, as the “gatekeepers” of intestinal homeostasis, play an important role in maintaining intestinal tissue homeostasis3. However, uncontrolled inflammation of macrophages contributes wildly to promoting IBD pathogenesis.

Heterogeneity is a major characteristic of macrophages4. After different challenges, macrophages can be polarized into the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype and anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype in vitro5. Over-activated pro-inflammatory macrophages secrete excessive amounts of cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, and TNF-α, to promote the differentiation and activation of Th1 and Th17 cells, which are critical in promoting intestinal inflammation and tissue damage. Recent studies have suggested that macrophage polarization is linked to intracellular metabolic reprogramming. An upregulated rate of aerobic glycolysis supports the pro-inflammatory properties of macrophages activated by pathogens6. 6-Phosphofructose-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), a key regulator of glycolysis in macrophages, was upregulated in macrophages after LPS stimulation, contributing to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. It has been widely recognized that PFKFB3 in macrophages promotes various inflammatory diseases such as endotoxemia and atherosclerosis7, 8, 9. However, the regulatory mechanisms of PFKFB3 in macrophages remain unclear.

Moreover, epigenetic modifications of gene expression are also critical factors in macrophage phenotype10. For example, a histone demethylase called Jumonji domain–containing protein D3 (JMJD3), mediates the demethylation of lysine residues on histones in a sequence-specific manner. Demethylation of trimethylation of histone H3 on lysine 27 (H3K27me3) by JMJD3 could significantly eliminate the inhibitory function of H3K27 trimethylation, thereby promoting gene expression11. Furthermore, JMJD3 could modulate macrophage polarization, as incubating LPS-stimulated macrophages with a JMJD3 inhibitor results in downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines12. Despite the significance of histone modification in macrophage functions, the upstream mechanism of regulating JMJD3 in macrophages in vivo and in vitro is poorly understood.

The protein LIM domain only 7 (LMO7) is encoded by the Lmo7 gene and has several important protein–protein interaction domains such as calponin homology (CH) domain, PDZ domain, F-Box domain, and LIM domain. LMO7 has been reported to be expressed in a variety of tissues and cells13. According to preliminary studies, LMO7 is localized at adhesions junction to maintain epithelial architecture, and it has also been linked to Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD) by regulating transcription of emerin14,15. Recent research suggests LMO7 in vascular smooth muscle cells can interact with c-FOS and c-JUN to promote their ubiquitination and degradation, inhibiting TGF-β signaling and potentially serving as a novel target for regulating fibrotic responses16. However, little is known about whether LMO7 regulates macrophage polarization and metabolism.

Herein, we provided evidence that LMO7 in macrophages protects against DSS-induced colitis. We found that the sensitivity to DSS-induced inflammation in myeloid-specific LMO7 deficiency mice leads to an increase in the number of pro-inflammatory macrophages, which aggravates colonic inflammation and damage. Furthermore, as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, we demonstrated that LMO7 can bind to PFKFB3 and induce its ubiquitination and degradation, thereby inhibiting glycolysis in macrophages and limiting TLR4-mediated pro-inflammatory response through negative feedback regulation. PFKFB3 facilitates JMJD3 expression by promoting glycolysis, which in turn elevates the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines. These findings indicated that LMO7 is a negative molecule in macrophage-related pro-inflammatory response and a potential drug target for treating inflammatory diseases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

Lmo7fl/fl mice were constructed by Cyagen (Suzhou, China) using CRISPR/Cas9 techniques. LysMCreLmo7fl/fl mice were generated by breeding Lysozyme M-Cre mice (Jackson Laboratory) with Lmo7fl/fl mice. Cx3cr1CreLmo7fl/fl mice were generated by breeding Cx3cr1-Cre mice (Jackson Laboratory) with Lmo7fl/fl mice. All mice used in experiments were 6–8 weeks-old male mice. Mice were bred and housed under a 12 h/12 h light–dark cycle in specific pathogen-free conditions at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. All mouse experiments were performed following protocols in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The identification method is shown in Supporting Information Table S1.

2.2. Reagents

DSS was purchased from MP Biomedicals. Triton X-100 (X100), BSA (SRE0098), protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340), LMO7 antibody (HPA050184), Trizol (93289), collagenase D (11088866001), DNase I (10104159001), MG-132 (C2211), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli (sero-type 0111:B4) were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich. H&E staining kit (C0105S), DAPI (C1005), RIPA buffer (P0013B), ATP activity kit (S0027), BCA protein assay kit (P0012), and the Nitric Oxide Assay Kit (S0021S) were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology. Antibodies for phospho-NF-κB p65 (3033), NF-κB p65 (8242), phospho-SAPK/JNK (9255), SAPK/JNK (9252), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (4370), p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (4695), phospho-p38 MAPK (4511), p38 MAPK (8690), β-actin (8457S), IκBα (4812), PFKFB3 (D7H4Q), Flag-Tag (14793S), HA-Tag (3724S), Myc-Tag (2272S and 2276S), JMJD3 (#3457) and H3K27me3 (C36B11), were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. DMEM medium (11965092), RPMI-1640 medium (11875093), and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, 10099) were obtained from Gibco company. 1% penicillin–streptomycin (60162 ES) and PEI transfection reagent (40816E) were purchased from Yeasen Biotech. Recombinant mouse M-CSF (576404), FITC-conjugated anti-Gr1 (108405), Zombie UV Fixable Viability Kit (423108), PerCP/Cy5.5-CD45 (103129), APC-CD11b (101211), PE/Cy7-F4/80 (123113), PE-CD80 (104708), PE-CD86 (159203) and PE-MHC-II (107607) antibodies were bought from BioLegend. The KOD-Plus-Mutagenesis Kit (SMK-101), the qPCR RT Master Mix (ALU-101), and the SYBR Green Real-time PCR Master Mix (ATP-111) were bought from TOYOBO. The Favorprep plasmid Extraction Mini kits (FAPDE100) were purchased from Solomonbio. The Protein G Agarose beads (P7700) were obtained from Millipore. The nitrocellulose membranes (10600002) were purchased from GE Healthcare BioScience. The ECL detection kits (A38555) were bought from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The MPO activity kits (A044-1-1) were obtained from Jiancheng Biotech. The Pyruvic acid detection kit (D799449) and the Lactic acid content detection kit (D799099) were purchased from Sangon Biotech. An anti-mouse CD16/32 antibody (553141) was bought from BD Bioscience. The IL-1β ELISA kit (PMLB00C), IL-6 ELISA kit (PM6000B), and TNF-α ELISA kit (PMTA00B) were obtained from R&D Systems. The Alexa Flour 488-conjugated anti-rabbit second antibody (SA00006-1) was purchased from proteintech. The Alexa Flour 594-conjugated anti-mouse second antibody (115-585-003) was obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch.

2.3. Animal models

For the DSS-induced colitis model, mice were randomly divided into different groups. Each mouse received 7 days of 3% DSS (36–50 kD; MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) treatment in the drinking water. The control group animals were administered distilled water. The mice were monitored daily for survival and body weight. On Day 7, mice were anesthetized and sacrificed for colon tissue harvesting. The harvested colon tissues were collected for further immunological and histological analysis.

2.4. Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

For histological analysis, Paraformaldehyde (4%, 48 h)-fixed colonic tissues were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Fixed tissues were cut into 5-μm-thick sections using a slicer and dewaxed. The sections were stained with H&E (C0105S, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and observed under a light microscope.

2.5. Immunofluorescence staining

For cell immunofluorescence staining, cells were fixed in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 (X100, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Subsequently, cells were blocked with 1% BSA (SRE0098, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, after which the secondary antibodies, Alexa Flour 488-conjugated anti-rabbit (SA00006-1, proteintech, Chicago, USA) and Alexa Flour 594-conjugated anti-mouse (115-585-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch, Pennsylvania, USA) were applied. The cell nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, C1005, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Images were captured (63 × objective) using the Leica Microsystems CMS GmbH Am Friedensplatz confocal laser scanning microscope (TSC SP8; Leica, Wetzler, Hesse, Germany).

2.6. Cell preparation and culture

BMDMs were prepared from WT or knockout mice with C57BL/6 background, as described previously. Bone marrow cells were isolated from femurs and tibias of mice. Cells were differentiated in DMEM medium (11965092, Gibco, MA, USA) added with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, 10099, Gibco, MA, USA), 1% penicillin–streptomycin (60162 ES, Yeasen Biotech, Shanghai, China), and 10 ng/mL recombinant mouse M-CSF (576404, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) for 5–7 days. Subsequently, cells were collected and seeded into plates. M-CSF was added to maintain the macrophage phenotype, followed by stimulation with various treatments for further assays. The human cervical carcinoma cell line HeLa (CCL-2), human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T (CRL-11268) cell line and human monocytic THP-1 cells (TIB-202) were purchased from ATCC and cultured in DMEM or RPMI-1640 medium (11875093, Gibco, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin. All cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

2.7. Plasmid construction and cell transfection

The cDNAs for PFKFB1, PFKFB3, ENO1, PKM2, PFKL, PFKP, PFKM, LDHA, HK2, and JMJD3 were obtained using standard PCR techniques with THP-1 cells. All cDNAs were subsequently inserted into mammalian expression vectors as indicated here. Plasmids encoding Ub were provided by Prof. Baoxue Ge (Tongji University, Shanghai). Truncated mutant vectors LMO7-LIM, LMO7-F-box, LMO7-PDZ, PFKFB3△6PF2K, PFKFB3△Phos, PFKFB3△NLS, PFKFB3 (K276R), PFKFB3 (K277R), PFKFB3 (K284R), PFKFB3 (K292R), PFKFB3 (K302R), PFKFB3 (K319R), PFKFB3 (K352R), PFKFB3 (K402R), PFKFB3 (K411R), PFKFB3 (K419R), Ub-K6, Ub-K11, Ub-K27, Ub-K29, Ub-K33, Ub-K48, Ub-K63 and Ub-K48R were constructed using the KOD-Plus-Mutagenesis Kit (SMK-101, TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions, using the UB-K0 plasmid. Plasmids encoding all plasmid DNAs for transfection were prepared using Favorprep plasmid Extraction Mini kits (Solomonbio, Shanghai, China). All the sequences were verified by HuaGene Company (Shanghai, China). The primers and probes are shown in Supporting Information Table S3.

HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with PEI transfection reagent (40816 ES, Yeasen Biotech, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions using plasmid.

2.8. Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

Assays were conducted as previously reported17. Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA) (P0013B, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Then cell lysates were centrifuged at 4 °C, and the supernatants were collected as extracted protein. These extracts were incubated with the Protein G Agarose beads (P7700, Millipore, Boston, MA, USA) for 1 h to remove nonspecific binding protein. Afterward, protein extracts were incubated overnight with protein A/G agarose beads along with the antibody, in constant rotation at 4 °C. The immune complex was then washed and subjected to immunoblot analysis. For Western blot, protein sample concentrations were quantified with bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (P0012, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). And then the proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare BioScience, Pittsburgh, USA). Primary antibodies, including phospho-NF-κB p65 (3033), NF-κB p65 (8242), phospho-SAPK/JNK (9255), SAPK/JNK (9252), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (4370), p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (4695), phospho-p38 MAPK (4511), p38 MAPK (8690), β-actin (8457S), IκBα (4812), PFKFB3 (D7H4Q), Flag-Tag (14793S), HA-Tag (3724S), Myc-Tag (2272S and 2276S), JMJD3 (#3457) and H3K27me3 (C36B11), were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology). The LMO7 antibody (HPA050184) was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). After incubation with primary and secondary antibodies, chemiluminescence of blots was developed using an ECL detection kit (A38555, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and detected by the ChemiDoc XRS+ from Bio-Rad. Band intensity was quantified by a densitometric analysis using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

2.9. Real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) assay

Total RNA samples from colon tissues or cells were extracted using Trizol (93289, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Single-strand cDNA was produced using qPCR RT Master Mix (ALU-101, TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) according to the protocol of the manufacturer and was used in subsequent real-time qPCR reactions. RT-qPCR was carried out to determine specific gene expression using the SYBR Green Real-time PCR Master Mix (ATP-111, TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) on StepOne Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) by the manufacturer. The quantification of target genes was identified by comparing Ct values of each sample normalized with Ct value of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and reaction specificity was verified by melting curve analysis. The gene expression levels were measured using the comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method (ΔΔCt) as described previously. The primer sequences are presented in Supporting Information Table S2.

2.10. Myeloperoxidase activity (MPO) assay

An MPO activity kit (A044-1-1, Jiancheng Biotech, Nanjing, China) was used for MPO activity determination. Colon tissues were washed, and homogenized in cooled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, w/w 1:19). The total protein was determined with a BCA assay kit (P0012, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Then, the MPO activity was determined following the instruction of the kit. The absorbance of the resulting mixture was measured at 460 nm with a microplate reader (BioTek, Vermont, USA).

2.11. ATP assay

The ATP activity kit (S0027, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used to determine the ATP activity of BMDMs challenged with or without LPS for 4 h. BMDMs were lysed at a concentration of 200 μL of lysis solution per 106 cells and the supernatant were collected for further analysis. Samples or standards were added into 100 μL ATP assay solution. After 5 min reaction, the absorbance of the resulting mixture was measured at 460 nm with a microplate reader (BioTek, Vermont, USA).

2.12. Pyruvic acid detection assay

The Pyruvic acid detection kit (D799449, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) was used to determine the pyruvic acid concentration of BMDMs challenged with or without LPS for 4 h. According to the instructions of the manufacturer, BMDM cells were ultrasonic crushed and centrifuged at 12,000×g for 10 min, and then the supernatant was collected for further analysis. After adding the sample, reagent I, and reagent II in turn, the absorbance of the resulting mixture was measured at 520 nm with a microplate reader (BioTek, Vermont, USA). The pyruvic acid concentration was determined using the standard curve.

2.13. Lactic acid content assay

The Lactic acid content detection kit (D799099, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) was used to determine the Lactic acid concentration of BMDMs challenged with or without LPS for 4 h. The reagent I was added to the cells and the cells were ultrasonically crushed. Then the mixture was centrifuged at 4 °C 12,000×g for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected for analysis. Then the samples were detected according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The absorbance of the resulting mixture was measured at 570 nm with a microplate reader (BioTek, Vermont, USA). The lactic acid concentration was determined using the standard curve.

2.14. Flow cytometry assay

Cells collected from LPS-stimulated BMDMs were firstly incubated with an anti-mouse CD16/32 antibody (553141, BD Bioscience, Franklin Lake, NJ, USA) for Fc blocking and then stained with PE-CD80 (104708), PE-CD86 (159203) or PE-MHC II (107607) (All were purchased from BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). In all the assays, cells were first gated by forward scatter with side scatter to exclude debris, and then the fluorescence intensity of these markers was detected.

To analyze or sort cells from tissues, tissues were perfused with sterile PBS, after which they were excised and digested using collagenase D (1.0 mg/mL) and DNase I (50 U/mL) (11088866001, 10104159001, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) through Miltenyi Biotec gentleMACS Octo Dissociator with Heaters (Miltenyi Biotec, Cologne, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), following the 37C-m-LPDK-1 program for colon tissues. Digested mice tissues were passed through 70-μm cell strainers to obtain a single-cell suspension. After lysis of RBCs, cells were stained with indicated combinations of antibodies. Dead cells were excluded by staining with Zombie UV Fixable Viability Kit (423108; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Each cell lineage was identified as follows: macrophages, CD45+CD11b+F4/80+; neutrophils, CD45+Gr1+. The FITC-Gr1 (108405), PerCP/Cy5.5-CD45 (103129), APC-CD11b (101211), and PE/Cy7-F4/80 (123113) antibodies were bought from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA).

All the cells mentioned above were studied on a flow cytometer (LSRFortessa TM X-20, BD Biosciences), and the data were analyzed with the FlowJo_V10 software (Treestar, Ashland OR, USA).

2.15. ELISA

As for the detection of selected protein concentrations in BMDMs supernatant, Lmo7+/+ and Lmo7−/− BMDMs were stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS for 12 h. Then the supernatant of these macrophages was collected, and the concentrations of IL-1β (PMLB00C, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), IL-6 (PM6000B, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and TNF-α (PMTA00B, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) were measured by ELISA kits, according to the manufacturer's protocols.

2.16. Determination of NO production

BMDMs were seeded in 12-well plates at 5 × 105 per well and incubated overnight. Cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. Supernatants were collected and the release levels of NO by BMDMs were measured by the Nitric Oxide Assay Kit (S0021S, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), as previously described.

2.17. Seahorse assay

An XF96 extracellular flux analyzer (Agilent Seahorse XFe96, Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used to determine the effects on glycolysis of Lmo7+/+ and Lmo7−/− BMDMs with or without LPS stimulation according to the instructions. Cells were seeded in an XF96 cell culture plate at 90,000 cells/well. The probe plate was hydrated with sterile water one day in advance. Right before the assays, cells were changed from a culture medium to an assay medium and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The glucose, oligomycin, and 2-DG were added into the probe plate following the manufacturer's protocols. After baseline measurements, chemicals prepared in the probe plate were sequentially injected into each well and subjected to the measurement of ECAR. Glycolysis and glycolysis capacity of Lmo7+/+ and Lmo7−/− BMDMs were reported as mpH/min and normalized to protein concentration.

2.18. RNA-sequencing analysis

RNA was extracted using the TRIzol Reagent. The RNA integrity was assessed using Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. A total of 4 high-quality samples were submitted for library preparation and sequencing. Illumina HiSeq2000 was used to generate RNA-sequencing data for all the samples. Sequencing results produced 66–70 million raw reads per sample. After elimination of the adapter sequences and the removal of poor-quality nucleotides, the samples were mapped using HISAT2 against the Genome Reference Consortium Mouse Build 39. Gene expression levels were normalized to Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped fragments (FPKM) for following analysis. Differentially expressed genes were identified with edgeR (R version 4.2.3) using a fold change expression cutoff ≥1 and false discovery rate adjusted P-value ≤0.05. ClusterProfiler package was used to carry out GO enrichment analysis and the dotplot was drawn by ggplot2 package. Data from GSE2713118, GSE336519, and GSE5499220 were analyzed by GEO2R, and the overlapped down-regulated genes were shown by the Venn diagram. Pearson's correlation analysis was performed on genes by ggstatsplot package with the results being visualized via ggplot2 package.

2.19. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of the data were conducted with GraphPad Prism software (ver. 8.3; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). One- or two-way ANOVA, Mann–Whitney test, or Student's t-test was used to compare differences between two groups as necessary. All experiment results were presented as the mean ± SD (n ≥ 3). Statistical significance was defined as ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. LMO7 is downregulated in pro-inflammatory macrophages

Microbial infection is a causative factor of several diseases, such as IBD and pneumonia, which triggers a serious inflammatory response and tissue damage. As important effector cells, macrophages play an important role in the development of these diseases. To better identify the functional signaling pathways and key genes in inflammatory macrophages, we first performed the analysis of differentially expressed genes in inflammatory diseases from the GEO database. Four genes (LMO7, CD160, ADGRG1, GZMA), especially for LMO7, were identified as down-regulated genes (Fig. 1A). While previous studies on LMO7 mainly focused on its role in non-immune cells, where it plays a cytoskeletal role, its function in macrophages remained unclear. In order to analyze the functions of LMO7 in macrophages, we examined the distribution of LMO7 in mouse BMDMs and found it is mainly distributed in the cytoplasm, which differs from its cytoskeleton localization in Hela cells (Fig. 1B). This finding predicts that LMO7 may have a unique function in macrophages.

Figure 1.

LMO7 is downregulated on infections and inhibits inflammatory responses in macrophages. (A) Venn diagram of the overlap of down-regulated genes in H1N1 influenza, tuberculosis, and inflammatory bowel disease. (B) Confocal microscopy imaging of BMDMs and HeLa cells expressing LMO7 (red) with antibodies to the appropriate protein, along with DAPI, respectively. Merge, LMO7 + DAPI. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of Lmo7 mRNA levels in Lmo7+/+ BMDMs under E. coli (MOI = 4) stimulation at various time points. (D) Immunoblot analysis of LMO7 in whole cell lysates of Lmo7+/+ BMDMs stimulated with E. coli (MOI = 4) at various time points. (E) Heatmap summarizing the expression of selected signature genes in BMDMs treated with E. coli (MOI = 4) for 6 h compared to the control using qRT-PCR. (F) Flow cytometry of EdU in BMDMs with or without E. coli stimulation. (G) The number of macrophages after stimulating bone marrow cells with M-CSF (10 ng/mL) for 6 days. (H) Flow cytometry of phagocytic macrophages with or without E. coli-GFP incubation. Data shown are presented as mean ± SD from one representative of three independent experiments (B–H). ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

To investigate whether LMO7 could regulate macrophage functions, we stimulated BMDMs with E. coli. It was found that both the transcript and the protein expression levels of LMO7 were decreased significantly (Fig. 1C‒D), which was consistent with our findings from database analysis. Furthermore, we found that in Lmo7-deleted macrophages compared to wild-type macrophages, the mRNA levels of multiple pro-inflammatory factor expressions, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, TNF-α and NOS2, were elevated after E. coli stimulation for 6 h (Fig. 1E). However, the LMO7 deficiency did not affect the growth of macrophages and their phagocytosis function on E. coli (Fig. 1F‒H). Taken together, these data suggest that LMO7 is significantly reduced in pro-inflammatory macrophages and it regulates the expression of pro-inflammatory factors in macrophages.

3.2. LMO7 inhibits pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization in vitro

LPS, a Gram-negative cell wall component, is a typical stimulus for studying microbial infections. Upon stimulation with LPS, LMO7 expression was gradually decreased with increasing stimulation time, both at the mRNA level and protein level (Fig. 2A‒B). Next, we analyzed the differences between Lmo7−/− BMDMs and Lmo7+/+ BMDMs. After 6 h LPS stimulation, the mRNA levels of M1-type cytokines and chemokines were upregulated in Lmo7−/− BMDMs, and the M1-type polarization surface markers CD80 and CD86 were also slightly increased. However, no significant changes were observed in macrophage phagocytosis receptors MACRO and SIRPα, and these changes were not due to alterations in TLR4 expression (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and NO in the supernatant of Lmo7−/− BMDMs were substantially higher than those in Lmo7+/+ BMDMs after stimulation (Fig. 2E‒F), and the same trend was observed towards the elevated levels of cell surface proteins CD80, CD86, and MHC-II (Fig. 2G). Further detection of TLR downstream signals after LPS stimulation showed that the phosphorylation of p38, p65, ERK, and JNK was upregulated in Lmo7−/− BMDMs (Fig. 2H‒I). In addition, we also found that higher levels of M1 pro-inflammatory cytokines and phosphorylation of p38, p65, ERK, and JNK were detected in Lmo7−/− BMDMs stimulated with Poly (I:C) (Supporting Information Fig. S1A‒B).

Figure 2.

LMO7 negatively regulates pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of Lmo7 mRNA levels in Lmo7+/+ BMDMs under LPS (100 ng/mL) stimulation at various time points. (B) Immunoblot analysis of LMO7 in whole cell lysates of Lmo7+/+ or Lmo7−/− BMDMs stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) at various time points. (C) Heatmap summarizing the expression of selected signature genes in BMDMs treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 6 h compared to the control using qRT-PCR. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of selected signature genes in BMDMs under IL-4 (10 ng/mL) or IL-13 (10 ng/mL) stimulation for 6 h. (E) ELISA analysis of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α production in supernatants of BMDMs infected with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 12 h. (F) The NO level was detected in BMDMs treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. (G) Flow cytometry of macrophage surface markers CD80, CD86 and MHC-II expression in BMDMs with LPS (100 ng/mL) stimulation for 12 h. (H) Immunoblot analysis of indicated protein in cell lysates of BMDMs infected with LPS (100 ng/mL). (I) Heatmap summarizing the expression of selected protein in BMDMs treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) compared to the control using immunoblot analysis. Data shown are presented as mean ± SD from one representative of three independent experiments (A–I). ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Subsequently, we stimulated BMDMs with multiple microbial components and found that LMO7 deficiency BMDMs expressed more IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in mRNA levels after being stimulated with other TLR ligands, including Pam3CSK4, dsDNA-EC, Poly (dA:dT) and ODN 1826 (Fig. S1C). However, there was no obvious difference between Lmo7−/− BMDMs and Lmo7+/+ BMDMs at the transcriptional level after stimulation with IL-4 and IL-13 (Fig. 2D). Moreover, the transcription level of LMO7 in BMDMs was significantly downregulated upon stimulation with TLR agonists (Fig. S1D). Together, our results indicate that the loss of LMO7 could promote macrophage M1-polarization in response to E. coli and TLR ligation, but does not have effects on macrophage M2-polarization.

3.3. LMO7 is crucial for metabolic reprogramming by inhibiting PFKFB3

To investigate how LMO7 inhibits macrophage M1-type polarization, we performed a comparative transcriptome analysis using RNA-seq between LPS-stimulated Lmo7−/− and Lmo7+/+ BMDMs. The Gene Ontology (GO) analysis revealed that the metabolic pathway of Lmo7−/− BMDMs was significantly changed compared to Lmo7+/+ BMDMs (Supporting Information Fig. S2A). Because glycolysis is an important metabolic modality affecting the inflammatory phenotype of macrophages, we detected the rate of glycolysis in BMDMs and found that it was increased in Lmo7−/− BMDMs compared to Lmo7+/+ BMDMs both after LPS stimulation and without stimulation (Fig. 3A‒B). This result was verified by measuring the content of ATP, PA, and LA in macrophages, which were important products of macrophage glycolysis. From this experiment, we found that the levels of ATP, PA, and LA in Lmo7−/− BMDMs were increased rapidly compared to Lmo7+/+ BMDMs after LPS stimulation (Fig. 3C). The levels of ATP and PA in Lmo7−/− BMDMs were also elevated after stimulation with other TLR activators (Fig. S2C). These results suggest that after TLR activation, the glycolytic capacity of Lmo7−/− BMDMs is higher than that of Lmo7+/+ BMDMs, which is likely to be an important factor affecting Lmo7-knockout macrophage polarization.

Figure 3.

LMO7 inhibits BMDM glycolysis via suppressing PFKFB3. (A) Lmo7+/+ and Lmo7−/− BMDMs were detected for extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) as an indicator for deduced glycolysis flux and glycolytic capacity. (B) The glycolysis flux and glycolytic capacity of BMDMs treated with or without LPS were analyzed. (C) The ATP, PA, and LA levels were detected in BMDMs treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 4 h. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-PFKFB3 and different amounts of HA-LMO7, along with or without MG132. Cell lysates were used to detect the expression of indicated protein. (E) Immunoblot analysis of PFKFB3 protein expression in cell lysates of BMDMs infected with LPS (100 ng/mL) at various time points. (F) The PA level was detected in BMDMs treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) or LPS + 3PO, respectively. (G) Heatmap summarizing the expression of selected signature genes in BMDMs treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) or LPS + 3PO using qRT-PCR. Data shown are presented as mean ± SD from one representative of three independent experiments (A–G). ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Macrophage glycolysis can be regulated by multiple rate-limiting enzymes21,22, and LMO7 is considered as an E3 Ub ligase and can promote targeted protein degradation. Therefore, we next explored whether LMO7 regulates macrophage glycolysis by changing the expression of these enzymes. After transfecting LMO7 with different glycolysis regulation enzymes into HEK293T cells respectively, LMO7 could specifically inhibit the expression of PFKFB3, but did not affect other rate-limiting enzymes such as HK2, PFKM, ENO1, LDHA, etc. (Fig. 3D and Supporting Information Fig. S2B). The expression of PFKFB3 was higher in Lmo7−/− BMDMs than in Lmo7+/+ BMDMs after 1 h of LPS stimulation (Fig. 3E). These data suggest that LMO7 suppresses macrophage glycolysis by reducing PFKFB3.

3PO, a specific inhibitor of PFKFB3, is widely used to inhibit the glycolytic capacity of cells23. Here we co-incubated Lmo7−/− BMDMs with 3PO and LPS, and found that the levels of both PA and ATP production were restored to be consistent with Lmo7+/+ BMDMs (Fig. 3F and Fig. S2D). This suggested that the higher glycolytic capacity of Lmo7−/− macrophages could be downregulated by 3PO. Moreover, in LPS-treated macrophages, 3PO treatment also normalized the higher expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, TNF-α and NOS2 in Lmo7−/− BMDMs (Fig. 3G). Our results also found that 2-DG, a wild-studied glycolysis inhibitor24, can inhibit the mRNA level of inflammatory cytokines expression in Lmo7−/− BMDMs (Fig. S2E). Taken together, the above results suggest that LMO7 inhibits the glycolytic and pro-inflammatory functions in macrophages by suppressing the PFKFB3 expression.

3.4. LMO7 interacts with PFKFB3 and promotes it K48-linked ubiquitination degradation

Next, we addressed the mechanism by which LMO7 induced inhibition of PFKFB3 expression. In our experiment, we found LMO7 deficiency in macrophages enhanced the PFKFB3 accumulation. Besides, after transfecting LMO7 with PFKFB3 into HEK293T cells, a ubiquitin–proteasome inhibitor MG132, was added into the supernatant of these cells, which inhibited the regulation function of LMO7 (Fig. 3D). This indicates that LMO7 mediates PFKFB3 degradation via the Ub-proteasome system. Next, we examined whether LMO7 could interact with PFKFB3. Our results showed that in HEK293T cell overexpression system, LMO7 was specifically associated with PFKFB3 (Fig. 4A), and this interaction between endogenous LMO7 and PFKFB3 was enhanced upon LPS stimulation in macrophages (Fig. 4B). Moreover, LMO7 and PFKFB3 were shown to be localized together by confocal microscopy assay in LPS activated macrophages (Fig. 4C). Then, to map the specific interaction region of LMO7 with PFKFB3, we generated three LMO7 mutants—LMO7-LIM, LMO7-F-box, LMO7-PDZ—and three PFKFB3 mutants—PFKFB3△6PF2K (6PF2K domain deletion), PFKFB3△Phos (phosphatase domain deletion), and PFKFB3△NLS (NLS domain deletion)—according to their functional motifs15,25. The PFKFB3△6PF2K and PFKFB3△NLS, rather than PFKFB3△Phos, could interact with LMO7 (Fig. 4D). The LMO7-F-box and LMO7-PDZ, but not LMO7-LIM, could associate with PFKFB3 (Fig. 4E). This shows that F-box and PDZ domains in LMO7 and the Phosphatase domain in PFKFB3 are indispensable for their interaction.

Figure 4.

LMO7 interacts with PFKFB3 and promotes the degradation and K48-linked polyubiquitination of PFKFB3. (A) Immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblot (IB) analysis of lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with various combinations (upper lanes) of plasmids encoding Flag-PFKFB3 and HA-LMO7. WCL, whole-cell lysate. (B) Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis of BMDMs stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL). (C) Confocal microscopy imaging of BMDMs stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) and labeled with antibodies for PFKFB3 (green), LMO7 (red), and DAPI, respectively. Merge, LMO7 + PFKFB3 + DAPI. Scale bar: 10 μm. (D) Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis of lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with HA-LMO7, plus Flag-PFKFB3 or Flag-PFKFB3 mutants (PFKFB3Δ6PF2K, PFKFB3ΔPhos, or PFKFB3ΔNLS). (E) Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis of HEK293T cells transfected with Flag-PFKFB3, plus HA-LMO7, or HA-LMO7 mutants (LMO7-LIM, LMO7-F-box, or LMO7-PDZ). (F) HEK293T cells were transfected with Myc-LMO7 and Flag-PFKFB3, along with HA-UB or its mutants (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation by the anti-Flag Ab, and then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (G) Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis of ubiquitination of LMO7 in HEK293T cells co-transfected with Myc-LMO7, HA-UB, along with Flag-PFKFB3, Flag-PFKFB3Δ6PF2K, Flag-PFKFB3ΔPhos, or Flag-PFKFB3ΔNLS. (H) HEK293T cells were transfected with Myc-LMO7 and Flag-PFKFB3, along with HA-UB or its mutant K48R. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation by the anti-Flag Ab, and then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (I) Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis of ubiquitination of PFKFB3 in BMDMs stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 2 h. (J) Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis of ubiquitination of PFKFB3 in HEK293T cells co-transfected with Flag-PFKFB3, Myc-UB, along with HA-LMO7, HA-LMO7-LIM, HA-LMO7-F-box, or HA-LMO7-PDZ. (K) Flag-PFKFB3 or its mutants (K276R, K277R, K284R, K292R, K302R, K319R, K352R, K402R, K411R, and K419R) were individually transfected into HEK293T cells, along with Myc-LMO7 and HA-UB. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation by the anti-Flag Ab, and then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (L) Immunoblot analysis of HEK293T cells transfected with Flag-PFKFB3 (K402R) with different amounts of HA-LMO7. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments (A–L).

Considering that LMO7 degrades PFKFB3 through proteasome pathway. We co-transfected the PFKFB3 plasmid, UB plasmid, and LMO7 plasmid into HEK293T cells. Overexpression of LMO7 or LMO7-F-box could significantly induce the PFKFB3 ubiquitination, while the LMO7-LIM and LMO7-PDZ did not have the same function (Fig. 4J). This indicates that F-box domain in LMO7 is essential in promoting ubiquitination of PFKFB3. Besides, we detected the LMO7-mediated ubiquitination of PFKFB3 in BMDMs and found it was markedly increased in Lmo7+/+ BMDMs after LPS stimulation, but the same trend was not observed in Lmo7−/− BMDMs (Fig. 4I). This indicates that LMO7 is important in PFKFB3 ubiquitination. To further investigate which polyubiquitin linkage on PFKFB3 was regulated by LMO7, plasmids for WT UB and its mutants (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63, with only one of the seven lysine residues retained as lysine, and the other six replaced with arginine), PFKFB3 and LMO7 were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. The results demonstrated that LMO7 markedly promoted the PFKFB3 K48-linked polyubiquitination (Fig. 4F). Consistently, transfecting the UB mutants K48R (substitution of the lysine residue at position 48 with arginine) plasmid into this system could not ubiquitinate the PFKFB3 (Fig. 4H). These data indicate LMO7 mediates K48-linked polyubiquitination of PFKFB3.

Finally, to assess the specific sites of LMO7-mediated ubiquitination in PFKFB3, plasmids of UB, LMO7, and three mutants for PFKFB3 were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. It was found that the Phosphatase domain in PFKFB3 plays a role in LMO7-mediated ubiquitination (Fig. 4G). Then all lysine sites in Phosphatase domain were substituted with arginine to create single-site mutants of PFKFB3 (PFKFB3 K276R, K277R, K284R, K292R, K302R, K319R, K352R, K402R, K411R, and K419R), which were transfected with LMO7 plasmid and UB plasmid into HEK293T cells. Our results showed that the LMO7-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of PFKFB3 were impaired by the K402R mutation (Fig. 4K‒L). This finding suggests Lys402 is required for LMO7-induced PFKFB3 ubiquitination, which is essential for LMO7 in regulating macrophage glycolysis and murine colitis.

3.5. LMO7-PFKFB3 signaling facilitates epigenetic regulation through JMJD3

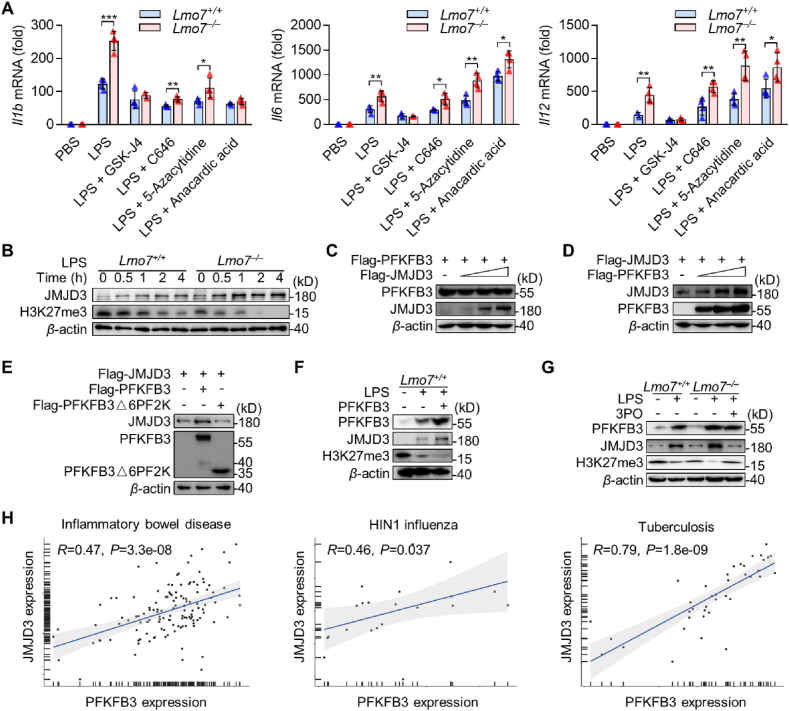

Since we have observed differences in transcript levels of NF-κB-mediated inflammatory cytokines between Lmo7−/− and Lmo7+/+ macrophages after stimulation with LPS (Fig. 2C), we hypothesized that Lmo7−/− macrophage epigenetics might be altered. Therefore, LPS-stimulated BMDMs were treated with GSK-J4 (H3K27 histone demethylase inhibitor), C646 (p300/CBP inhibitor), 5-azacytidine (DNA methyltransferase inhibitor), and anacardic acid (histone acetyltransferases inhibitor), separately26, 27, 28, 29. We found that the specific inhibitor of JMJD3, GSK-J4, significantly decreased mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12 in Lmo7−/− BMDMs to the same levels as Lmo7+/+ BMDMs (Fig. 5A). Then the JMJD3 expression level was detected in macrophages after LPS stimulation. Consistent with speculation, JMJD3 was significantly upregulated before or after LPS stimulation in Lmo7−/− BMDMs, and the levels of H3K27me3 were significantly lower in Lmo7−/− BMDMs than in Lmo7+/+ BMDMs after LPS stimulation (Fig. 5B), which was beneficial for the transcriptional expression of inflammatory mediators.

Figure 5.

PFKFB3 aggravates macrophage inflammation through promoting JMJD3 expression. (A) qRT-PCR analysis Il1b, Il6 and Il12 mRNA levels in Lmo7+/+ or Lmo7−/− BMDMs under LPS with or without multiple epigenetic-related enzyme inhibitors stimulation for 6 h. (B) Immunoblot analysis of JMJD3 and H3K27me3 protein expression in cell lysates of BMDMs infected with LPS at various time points. (C) Immunoblot analysis of HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-PFKFB3 and increased volumes of Flag-JMJD3. (D) Immunoblot analysis of HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-JMJD3 and increased volumes of Flag-PFKFB3. (E) Immunoblot analysis of HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-JMJD3, Flag-PFKFB3, or its mutant Flag-PFKFB3△6PF2K. (F) Immunoblot analysis of PFKFB3, JMJD3, and H3K27me3 expression in BMDMs which overexpressed PFKFB3 and had been infected with LPS, or in BMDMs without any challenge. (G) Immunoblot analysis of PFKFB3, JMJD3, and H3K27me3 expression in BMDMs infected with LPS or LPS + 3PO. (H) Correlation between level of JMJD3 expression and PFKFB3 expression in Inflammatory bowel disease (GSE3365), H1N1 influenza (GSE27131), and Tuberculosis (GSE54992). Statistical analyses were calculated using Spearman's correlation. Data shown are presented as mean ± SD from one representative of three independent experiments (A–G). ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

We have demonstrated that the expression of both JMJD3 and PFKFB3 was higher in Lmo7−/− BMDMs compared with Lmo7+/+ BMDMs after LPS stimulation, and LMO7 could degrade PFKFB3. However, there is no evidence that LMO7 can directly regulate JMJD3, so we explored whether there was a connection between JMJD3 and PFKFB3. After co-transfecting JMJD3 and PFKFB3 into HEK293T cells, the expression of PFKFB3 was not affected as the expression of JMJD3 increased (Fig. 5C). By contrast, PFKFB3 could promote the expression of JMJD3 via 6PF2K domain in PFKFB3 (Fig. 5D‒E). We also observed the same phenomenon in macrophages, and the expression of JMJD3 was significantly decreased after the addition of 3PO, while the level of PFKFB3 was not affected (Fig. 5F‒G). Additionally, GSK-J4 suppressed the transcriptional upregulation of pro-inflammatory factors in macrophages induced by PFKFB3 overexpression (Fig. S2F).

To further investigate whether PFKFB3 regulates JMJD3 in humans, we searched for dataset in the database that included the sequencing of human inflammatory bowel disease, H1N1 influenza, and Tuberculosis. A positive correlation was found between JMJD3 and PFKFB3 expression in all these human diseases (Fig. 5H). In summary, we confirmed that PFKFB3 promotes JMJD3 expression by elevating the rate of cellular glycolysis, and 3PO was able to inhibit this function. It explains that how LMO7 inhibits JMJD3 expression through PFKFB3, which in turn suppresses macrophage pro-inflammatory capacity.

3.6. Myeloid-specific LMO7 deficiency promotes DSS-induced colitis

Gut microbial dysbiosis is an important causative factor of IBD30. The analysis of human IBD revealed that the gene level of LMO7 was significantly downregulated, which was consistent with our finding in intestinal macrophages of the DSS-induced mouse IBD model (Supporting Information Fig. S4A‒B). To investigate whether LMO7 could regulate intestinal inflammation through macrophages, we generated myeloid-specific LMO7-deficient mice (referred to as LysMcreLmo7fl/fl) (Supporting Information Fig. S3). Survival assays showed that the morbidity level was upregulated in LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice compared to Lmo7fl/fl mice after being 7 days of 3% DSS challenged. DSS induced 90% mortality in LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice after 15 days, whereas only 50% mortality in Lmo7fl/fl mice (Fig. 6A). Compared to Lmo7fl/fl mice, LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice were highly susceptible to DSS, exhibiting increased body weight loss, higher disease activity index and shorter colon length (Fig. 6B‒E). The MPO activity, an important indicator of tissue inflammatory damage and neutrophil infiltration31, was greatly increased in the colon tissue of LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice compared to Lmo7fl/fl mice after DSS treatment for 7 days (Fig. 6F). Besides, the histopathology displayed that LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice also had more severe intestinal damage, significantly reduced crypt numbers, and increased inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 6H‒I). Moreover, the expression of antimicrobial peptides in LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice colon tissues were markedly reduced (Fig. S4C).

Figure 6.

LMO7 deficiency in macrophages aggravates DSS colitis. (A) Survival rate, (B) body gain ratio, (C) and disease activity index of Lmo7fl/fl and LysMCreLmo7fl/fl mice after modeling with 3% DSS. (D–E) Photos and statistical plots of the length of mice colon tissues. (F) MPO content in mice colon tissues. (G) Heatmap summarizing the expression of selected signature genes in mice colon tissues using qRT-PCR. (H) H&E staining of mice colon tissues. Scale bars: 200 μm. (I) Crypt number of each mouse colonic section according to H&E staining results. (J) Flow cytometry analysis of macrophages (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+) and neutrophils (CD45+Gr1+) in mice colon tissues. Each symbol represents an individual mouse (E‒F, and I‒J). Data shown are presented as mean ± SD from one representative of three independent experiments. ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

To test the effects of LMO7 on macrophages and neutrophils dynamics in DSS-induced colitis model, we detected colonic infiltrating neutrophils and macrophages after DSS induction. Increased macrophages and neutrophils were detected on Day 7 after modeling, and the intestinal neutrophil and macrophage infiltrations were both increased in LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice compared to Lmo7fl/fl mice (Fig. 6J). Further analysis indicated that the mRNA levels of colon pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were markedly increased in LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice on Day 7, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, TNF-α, NOS2, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5 and CXCL9, which were mainly secreted by macrophages to accelerate intestinal inflammation. Moreover, the CD80 and CD86 expressions on the surface of pro-inflammatory macrophages were promoted (Fig. 6G). The higher expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and M1-type surface markers indicated a more pro-inflammatory phenotype of macrophages in LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice in vivo, which was consistent with our findings in vitro (Fig. 2C). These results indicated that LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice were more sensitive to DSS-induced colitis, together with increased intestinal inflammation and tissue damage. In addition, macrophage-specific Lmo7 knockout mice exhibited heightened susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis (Supporting Information Fig. S5).

3.7. PFKFB3 and JMJD3 are critical for IBD pathogenesis in myeloid-specific LMO7-deficient mice

Previous results have shown that myeloid-specific LMO7-deficient mice were more sensitive to DSS-induced colitis (Fig. 6). Given the elevated expression of PFKFB3 and JMJD3 in Lmo7−/− BMDMs (Fig. 3E), which promotes macrophage inflammation, we examined PFKFB3 and JMJD3 in colon tissues of mice with colitis. We found that the PFKFB3 and JMJD3 expressions were increased in intestinal tissues of mice with colitis. The expression of PFKFB3 and JMJD3 was higher in LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice than in Lmo7fl/fl mice before and after modeling. Consistent with this, LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice colons exhibited a dramatic reduction in H3K27me3 expression compared with controls before and after operation (Figs. 7A and 8).

Figure 7.

Inhibition of JMJD3 and PFKFB3 effectively alleviates intestinal inflammation in myeloid-specific LMO7 deficiency mice. (A) Immunoblot analysis of PFKFB3, JMJD3, and H3K27me3 protein expression in mice colon tissues. (B) Body gain ratio, (C) disease activity index, (D) and colon length of Lmo7fl/fl and LysMCreLmo7fl/fl mice after modeling with 3% DSS, 3% DSS+3PO or 3% DSS + GSK-J4, respectively. (E) Crypt number of each mouse colonic section according to H&E staining results. (F) H&E staining of mice colon tissues. Scale bars: 200 μm. (G) The proportion of macrophages in colon tissues of mice. (H) PA content of mice serum. (I) Immunoblot analysis of PFKFB3, JMJD3, and H3K27me3 protein expression in mice colon tissues. Each symbol represents an individual mouse (B‒E, and G‒H). Data shown are presented as mean ± SD from one representative of three independent experiments. ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Figure 8.

An abridged general view of the role of LMO7 in macrophage. LMO7 is downregulated in pro-inflammatory macrophages after LPS stimulation, and it degrades PFKFB3 through K48-mediated ubiquitination. The degradation of PFKFB3 leads to the glycolytic process inhibition in macrophages, thus suppressing the expression of JMJD3, thereby promoting H3K27me3 and further regulating macrophage polarization.

Next, we treated mice with 3PO and GSK-J4 respectively, and found both 3PO and GSK-J4 treatment resulted in weight recovery, decreased disease activity index, and increased colon length in LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice, which were not significantly different from the Lmo7fl/fl mice (Fig. 7B‒D). According to the H&E staining, less tissue damage and fewer inflammatory cell infiltration were observed in LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice colon tissues after 3PO or GSK-J4 treatment, and the number of crypts were restored to a level higher than LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice (Fig. 7E‒F). The results of flow cytometry analysis revealed that both 3PO and GSK-J4 attenuated macrophage infiltration in colon tissues of LysMcreLmo7fl/fl colitis mice (Fig. 7G). Besides, PA levels in mouse serum were also significantly decreased in LysMcreLmo7fl/fl mice after 3PO treatment (Fig. 7H). In LysMcreLmo7fl/fl colitis mice treated with 3PO, the expression of PFKFB3 and JMJD3 was significantly decreased, along with the H3K27me3 was increased (Fig. 7I). This was consistent with our finding in macrophages after both LPS and 3PO stimulation, indicating that PFKFB3 promoted JMJD3 expression both in vivo and in vitro. However, only 3PO exhibited a modest improvement in colitis in Lmo7fl/fl mice, and GSK-J4 did not show any significant effect (Supporting Information Fig. S6). These findings suggest that inhibition of PFKFB3 or JMJD3 can alleviate intestinal inflammation through inhibiting macrophage pro-inflammatory function.

4. Discussion

Excessive activation of the immune response by exogenous microorganisms is an important cause of many inflammatory diseases, especially IBD. Macrophages are crucial for gut homeostasis, and fine controlling of its activation is important to prevent inflammation. In this study, we discovered that inflammatory macrophages promote intestinal inflammation, which is also consistent with previous research. LMO7, a protein widely expressed in vivo, has previously been linked to cell structure13. Here we demonstrated that LMO7 is an important molecule which regulates macrophage polarization and suppresses intestinal inflammation in DSS-induced IBD model. Specific deficiency of LMO7 in macrophages exacerbated colitis, suggesting that intestinal inflammation is regulated by LMO7 through macrophages. In addition, we also found that LMO7 has an inhibitory effect on inflammation in mice with acute lung injury (unpublished), suggesting that this phenomenon may be applicable to a variety of inflammatory diseases.

As key immune cells in the inflammatory response, macrophages exhibit different inflammatory phenotypes in response to stimuli. The more classical are LPS-induced M1-type macrophages and IL-4 and IL-13-induced M2-type macrophages. We discovered that LMO7 inhibited macrophage M1-type polarization after activation of TLR, while LMO7 appeared to have no effect on IL-4 and IL-13-induced macrophage M2-type polarization. In addition, we also found that LMO7 was downregulated in macrophages after TLR activation, which may be a feedback regulation by macrophages to promote a greater inflammatory response. The mechanism of why LMO7 specifically responds to TLR activation and its subsequent downregulation still needs to be further explored. In our system, we focus on the mechanism of how LMO7 inhibits the macrophage inflammatory response.

The function of macrophages can be predetermined by macrophage glycolysis, and the pro-inflammatory stimuli activate macrophages, leading to a shift in macrophage metabolism towards glycolysis rather than oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS)32,33. PFKFB3 promotes glycolysis by increasing the activity of 6-phosphofructose-1-kinase (PFK1), which leads to macrophage inflammation and tissue injury. However, the mechanisms that how PFKFB3 is regulated and how PFKFB3 alters macrophage function have not been fully understood. We investigated that LMO7 interacted with PFKFB3 to promote its degradation through K48-related ubiquitination, in which the 402 lysine residue on PFKFB3 is critical. This process can inhibit macrophage glycolysis, thereby effectively preventing excessive inflammatory responses of macrophages and protecting tissues from inflammatory damage.

Furthermore, we confirmed for the first time that PFKFB3 had a role in regulating JMJD3 through increasing glycolysis. This function can be eliminated by removing the functional domain of PFKFB3 or by blocking it with 3PO. We also observed a similar correlation between PFKFB3 and JMJD3 in human inflammatory diseases in databases. This mechanism interconnects macrophage glycolysis with epigenetics, which is important for understanding macrophage inflammatory responses. However, the exact mechanism of it needs to be further explored. Moreover, PFKFB3 is an important pro-tumor protein and a target for cancer therapy34. It would be meaningful to explore how PFKFB3 affects tumor cell epigenetics, which may provide new ideas for tumor therapy.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this work highlights the significance of the LMO7/PFKFB3/JMJD3 axis in understanding the inflammatory response of macrophages. Specifically, macrophages elevate the glycolytic rate after TLR activation and can be converted into an inflammatory phenotype, and LMO7 inhibits this process by binding to PFKFB3 to promote its ubiquitinated degradation. It could in turn suppress the expression of JMJD3 and reduce the excessive inflammatory response of macrophages, which is essential to protect the organism from excessive immune responses induced by microbe.

Author contributions

Shixin Duan: Designed, performed, and interpreted experimental data and wrote the paper. Xinyi Lou, Shiyi Chen, Hongchao Jiang, Dongxin Chen, Rui Yin, Mengkai Li, Yuseng Gou, Wenjuan Zhao, Lei Sun: Performed and interpreted experimental data. Shixin Duan and Feng Qian: Conceived the study and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82373875, 82173821, 81973329, 82273934, 82073858, 82104186).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2023.09.012.

Contributor Information

Lei Sun, Email: sunlei_vicky@sjtu.edu.cn.

Feng Qian, Email: fengqian@sjtu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Du G., Qin M., Sun X. Recent progress in application of nanovaccines for enhancing mucosal immune responses. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13:2334–2345. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisgaard T.H., Allin K.H., Keefer L., Ananthakrishnan A.N., Jess T. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19:717–726. doi: 10.1038/s41575-022-00634-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hegarty L.M., Jones G.R., Bain C.C. Macrophages in intestinal homeostasis and inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:538–553. doi: 10.1038/s41575-023-00769-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delfini M., Stakenborg N., Viola M.F., Boeckxstaens G. Macrophages in the gut: masters in multitasking. Immunity. 2022;55:1530–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora S., Dev K., Agarwal B., Das P., Syed M.A. Macrophages: their role, activation and polarization in pulmonary diseases. Immunobiology. 2018;223:383–396. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly B., O'Neill L.A. Metabolic reprogramming in macrophages and dendritic cells in innate immunity. Cell Res. 2015;25:771–784. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L., Cao Y., Gorshkov B., Zhou Y., Yang Q., Xu J., et al. Ablation of endothelial Pfkfb3 protects mice from acute lung injury in LPS-induced endotoxemia. Pharmacol Res. 2019;146 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tawakol A., Singh P., Mojena M., Pimentel-Santillana M., Emami H., MacNabb M., et al. HIF-1alpha and PFKFB3 mediate a tight relationship between proinflammatory activation and anerobic metabolism in atherosclerotic macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1463–1471. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo S., Li A., Fu X., Li Z., Cao K., Song M., et al. Gene-dosage effect of Pfkfb3 on monocyte/macrophage biology in atherosclerosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2022;179:4974–4991. doi: 10.1111/bph.15926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Q., Cao X. Epigenetic regulation of the innate immune response to infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:417–432. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis F.M., Tsoi L.C., Melvin W.J., denDekker A., Wasikowski R., Joshi A.D., et al. Inhibition of macrophage histone demethylase JMJD3 protects against abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Exp Med. 2021;218 doi: 10.1084/jem.20201839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satoh T., Takeuchi O., Vandenbon A., Yasuda K., Tanaka Y., Kumagai Y., et al. The Jmjd3-Irf4 axis regulates M2 macrophage polarization and host responses against helminth infection. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:936–944. doi: 10.1038/ni.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du T.T., Dewey J.B., Wagner E.L., Cui R., Heo J., Park J.J., et al. LMO7 deficiency reveals the significance of the cuticular plate for hearing function. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1117. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ooshio T., Irie K., Morimoto K., Fukuhara A., Imai T., Takai Y. Involvement of LMO7 in the association of two cell‒cell adhesion molecules, nectin and E-cadherin, through afadin and alpha-actinin in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31365–31373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401957200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holaska J.M., Rais-Bahrami S., Wilson K.L. Lmo7 is an emerin-binding protein that regulates the transcription of emerin and many other muscle-relevant genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:3459–3472. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie Y., Ostriker A.C., Jin Y., Hu H., Sizer A.J., Peng G., et al. LMO7 is a negative feedback regulator of transforming growth factor beta signaling and fibrosis. Circulation. 2019;139:679–693. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang Q., Cai W., Zhao Y., Xu H., Tang H., Chen D., et al. Lycorine ameliorates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis. Pharmacol Res. 2020;158 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berdal J.E., Mollnes T.E., Waehre T., Olstad O.K., Halvorsen B., Ueland T., et al. Excessive innate immune response and mutant D222G/N in severe A (H1N1) pandemic influenza. J Infect. 2011;63:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burczynski M.E., Peterson R.L., Twine N.C., Zuberek K.A., Brodeur B.J., Casciotti L., et al. Molecular classification of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis patients using transcriptional profiles in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:51–61. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai Y., Yang Q., Tang Y., Zhang M., Liu H., Zhang G., et al. Increased complement C1q level marks active disease in human tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bommer G.T., Van Schaftingen E., Veiga-da-Cunha M. Metabolite repair enzymes control metabolic damage in glycolysis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2020;45:228–243. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo X., Li H., Xu H., Woo S., Dong H., Lu F., et al. Glycolysis in the control of blood glucose homeostasis. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2012;2:358–367. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyu Z.S., Tang S.Q., Xing T., Zhou Y., Lv M., Fu H.X., et al. The glycolytic enzyme PFKFB3 determines bone marrow endothelial progenitor cell damage after chemotherapy and irradiation. Haematologica. 2022;107:2365–2380. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2021.279756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng J., Zhang R., Xu Z., Ke Y., Sun R., Yang H., et al. Early glycolytic reprogramming controls microglial inflammatory activation. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:129. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02187-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartrons R., Rodríguez-García A., Simon-Molas H., Castaño E., Manzano A., Navarro-Sabaté À., et al. The potential utility of PFKFB3 as a therapeutic target. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2018;22:659–674. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2018.1498082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hao Y., Ren Z., Yu L., Zhu G., Zhang P., Zhu J., et al. p300 arrests intervertebral disc degeneration by regulating the FOXO3/Sirt1/Wnt/beta-catenin axis. Aging Cell. 2022;21 doi: 10.1111/acel.13677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abu-Hanna J., Patel J.A., Anastasakis E., Cohen R., Clapp L.H., Loizidou M., et al. Therapeutic potential of inhibiting histone 3 lysine 27 demethylases: a review of the literature. Clin Epigenet. 2022;14:98. doi: 10.1186/s13148-022-01305-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao X.Y., Zhang X.L. DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-AZA-DC regulates TGFbeta1-mediated alteration of neuroglial cell functions after oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/9259465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29.Li S., Peng B., Luo X., Sun H., Peng C. Anacardic acid attenuates pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy through inhibiting histone acetylases. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:2744–2752. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni J., Wu G.D., Albenberg L., Tomov V.T. Gut microbiota and IBD: causation or correlation? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Y., He H., Ding Y., Liu S., Zhang D., Wang J., et al. MK2 mediates macrophage activation and acute lung injury by regulating let-7e miRNA. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2018;315:L371–L381. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00019.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzalez M.A., Lu D.R., Yousefi M., Kroll A., Lo C.H., Briseno C.G., et al. Phagocytosis increases an oxidative metabolic and immune suppressive signature in tumor macrophages. J Exp Med. 2023;220 doi: 10.1084/jem.20221472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhong W.J., Liu T., Yang H.H., Duan J.X., Yang J.T., Guan X.X., et al. TREM-1 governs NLRP3 inflammasome activation of macrophages by firing up glycolysis in acute lung injury. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:242–257. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.77304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y., Qu C., Liu T., Wang C. PFKFB3 inhibitors as potential anticancer agents: mechanisms of action, current developments, and structure‒activity relationships. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;203 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.