Abstract

Introduction: Violence in the intensive care unit (ICU) is poorly characterised and its incidence is largely extrapolated from studies in the emergency department. Policy requirements vary between jurisdictions and have not been formally evaluated.

Methods: A multisite, single-time point observational study was conducted across Australasian ICUs which focused on the incidence of violence in the previous 24 hours, the characteristics of patients displaying violent behaviour, the perceived contributors, and the management strategies implemented. Unit policies were surveyed across a range of domains relevant to violence management.

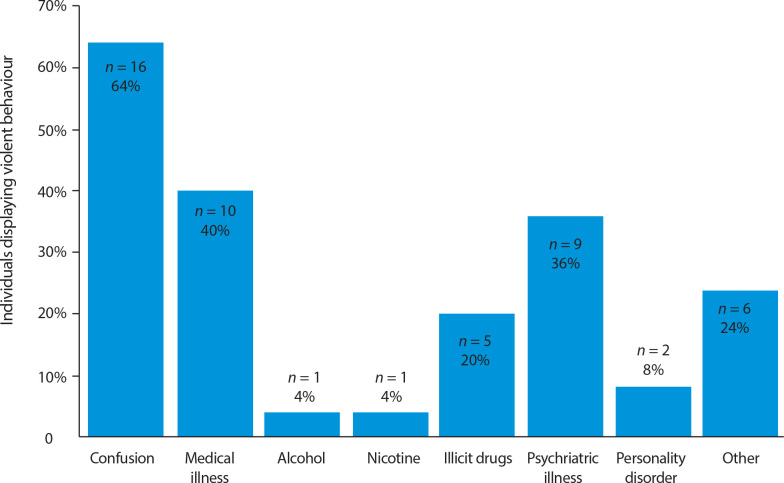

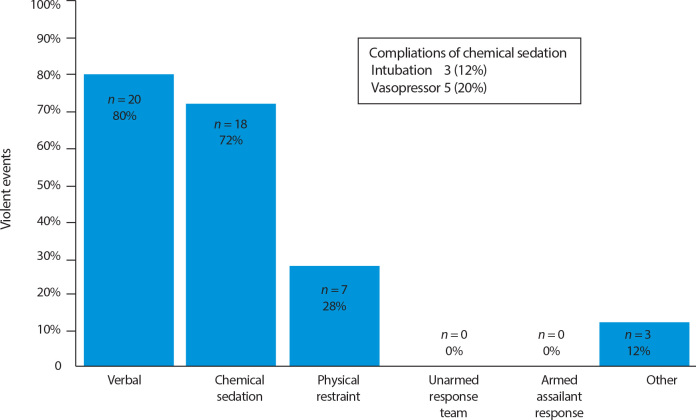

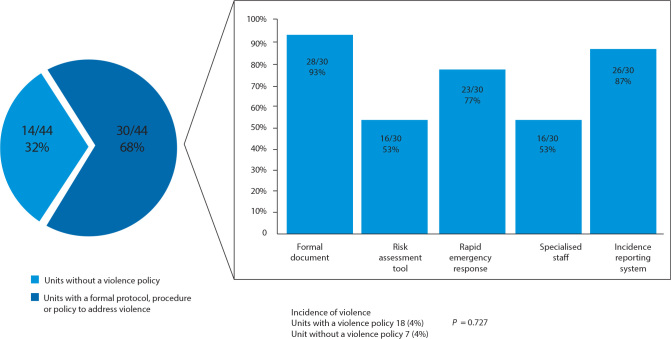

Results: Data were available for 627 patients admitted to 44 ICUs on one of 2 days in June 2019. Four per cent (25/627) displayed at least one episode of violent behaviour in the previous 24 hours. Violent behaviour was more likely in individuals after a greater length of stay in hospital (incidence, 2%, 4% and 7% for day 0-2, 3-7 and > 7 days respectively; P = 0.01) and in the ICU (2%, 4% and 9% for day 0-2, 3-7 and > 7 of ICU stay respectively; P < 0.01). The most common perceived contributors to violence were confusion (64%), physical illness (40%), and psychiatric illness (34%). Management with chemical sedation (72%) and physical restraint (28%) was commonly required. Clinicians assessed an additional 53 patients (53/627, 9%) as at risk of displaying violence in the next 24 hours. Of the 44 participating ICUs, 30 (68%) had a documented violence procedure.

Conclusion: Violence in the ICU was common and frequently required intervention. In this study, one-third of ICUs did not have formal violence procedures, and in those with violence procedures, considerable variation was observed.

Workplace violence in the intensive care unit (ICU) has implications for the provision of quality care and staff wellbeing.1 The World Health Organization recognises violence in health care as a priority, defining it as "Incidents where staff are abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances related to their work ... involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well-being or health”.2

While workplace violence likely occurs at a higher rate in the ICU than in other areas of health care,3 the evidence to support this is largely limited to retrospective, survey-based data or single-centre observational studies. These studies are limited by significant recall and sampling bias,4 but suggest that nurses are at higher risk of both verbal and physical violence than medical staff,5 with verbal violence occurring more often than physical assaults. Persons at risk of displaying violent behaviour in hospital have been found to be more likely to be young, male, and associated with presentations related to brain injury, trauma or substance intoxication.6 Almost half of all ICU staff reported being subject to verbal or physical assault in the past.5 The predictive factors of violent behaviour and the efficacy of preventive strategies remain unknown.

In Australia and New Zealand, guidelines for management of episodes of aggression or violence vary widely. In Australia, federal government regulations stipulate the presence of a response plan with adequately trained staff.7 This directive is further supplemented by state-based guidelines, which differ in terminology, personnel, training requirements and reporting.8, 9, 10, 11 In New Zealand, no nationwide guidelines are available, with response plans determined by local District Health Boards. Currently, data on the implementation and efficacy of such programs in an intensive care context are scarce.

We determined there was a need to provide reliable observational data to guide further study, procedure development, and reporting of violent events. Accordingly, we designed and conducted a multisite, single-time point prevalence study as part of the Point Prevalence Program (PPP) within the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group (ANZICS CTG) to estimate the incidence and nature of violent events occurring in the ICU.

Methods

This study was performed as a multisite, single-time point observational prevalence study. It was conducted within the annual ANZICS CTG PPP, run by the George Institute for Global Health.12 All adult ICUs across Australia and New Zealand were invited to participate in the ANZICS CTG PPP. Human Ethics Research Committees and/or relevant institutional approval for waiver of consent was obtained for all participating sites. Most sites were approved as low risk through the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney (Ref. No. HREC/18/RPAH/732; ERM Ref. ID 51827), with the remainder approved under local ethics committee permissions.

Data collection was performed by site-specific data collectors on one of two alternate study days in June 2019, with the preferred date elected by the participating site to facilitate convenience. All adult patients admitted in the ICU at 10 am on the elected study day were included in data analysis. Demographic and admission data were obtained from patient records, while clinical perceptions of contributing factors to violence and future violence risk were collected via a questionnaire completed by the bedside nurse on the study day (Online Appendix, section 2). Data were collated using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted through the George Institute for Global Health,13 with patient de-identification occurring before release from each site.

Data were collected regarding the occurrence and nature of violent behaviour in the preceding 24 hours and any identified contributory factors. Management strategies were recorded, and the bedside nurse was surveyed as to their perceived threat of future violence. In addition, questions were included for each site detailing the nature of procedures in place to manage aggression. Comparisons between patients were made among pre-specified cohorts, while unit procedure prevalence was compared among types of units. The statistical analysis was performed using JASP (University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Categorical outcomes were compared using a χ2 test, and the Mann-Whitney U test and Student t test were used for continuous data. A threshold of 0.05 was used to denote statistical significance.

Results

Forty-four individual ICU sites participated in this study, with data from 627 patients available for analysis. The demographic characteristics of the patient cohort are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cohort demographic characteristics

| Values | |

|---|---|

| Participants | 627 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 58.8 (17.0) |

| Sex, male | 377 (60%) |

| APACHE II score, mean (SD) | 16.5 (7.1) |

| Day of ICU stay, median (IQR) | 4.5 (1.4–9.9) |

| Admission source | |

| Emergency department | 199 (31.7%) |

| Operating theatre (elective case) | 131 (20.9%) |

| Hospital ward | 126 (20.1%) |

| Operating theatre (emergency case) | 93 (14.8%) |

| Transfer from external hospital ward | 39 (6.2%) |

| Transfer from external ICU | 39 (6.2%) |

| Reason for ICU admission⁎ | |

| Postoperative | 232 (37.0%) |

| Respiratory | 109 (17.4%) |

| Cardiovascular | 62 (9.9%) |

| Neurological | 58 (9.3%) |

| Sepsis | 58 (9.3%) |

| Trauma | 35 (5.6%) |

| Metabolic | 34 (5.4%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 24 (3.8%) |

| Renal | 9 (1.4%) |

| Other | 12 (1.9%) |

APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation.

Patients may have multiple admission diagnoses.

Violent behaviour

Four per cent (25/627) of patients displayed violent behaviour in the 24 hours studied. Of the 25 episodes of violent behaviour, 60% (15/25) involved verbal abuse, 76% (19/25) physical abuse, and 36% (9/25) showed both verbal and physical abuse (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Violence incidence

| Values | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients demonstrating violence | 25/627 (4%) | |

| Perceived risk of future violence | 53/627 (9%) | |

| Nature of violence | ||

| Verbal | 1 5/25 (60%) | |

| Physical | 19/25 (76%) | |

| Both verbal and physical | 9/25 (36%) | |

| Other | 3/25 (12%) | |

| Unit reporting violent events | ||

| Tertiary ICU | 20/469 (4%) | |

| Non-tertiary | 5/158 (3%) | 0.53⁎ |

| Country | ||

| Australia | 23/537 (5%) | |

| New Zealand | 2/90 (2%) | 0.35⁎ |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 17/377 (5%) | |

| Female | 8/250 (3%) | 0.40⁎ |

| Age group, years | ||

| 18-34 | 6/79 (8%) | |

| 35-64 | 12/284 (4%) | |

| > 65 | 7/269 (3%) | 0.11⁎ |

| Day of Hospital admission | ||

| 0-2 | 4/232 (8%) | |

| 3-7 | 7/198 (4%) | |

| > 8 | 14/197 (7%) | 0.01⁎ |

| Day of ICU admission | ||

| 0-2 | 8/339 (2%) | |

| 3-7 | 6/171 (4%) | |

| > 8 | 11/106 (9%) | <0.01⁎ |

| APACHE II score, mean (SD) | ||

| Patients displaying violence | 16.1 (7.0) | |

| Patients not displaying violence | 16.9 (7.1) | 0.90† |

| Hospital mortality up to 28 days | ||

| Patients displaying violence | 3/25 (14%) | |

| Patients not displaying violence | 78/602 (15%) | 0.88* |

APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; ICU = intensive care unit; SD = standard deviation.

χ2 test for independence.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of patients at perceived risk of or displaying violent behaviour

| Perceived risk⁎ | Patients displaying violence | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 28 | 25 | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 44.0 (18.1) | 53.5 (18.9) | 0.07† |

| Sex, male | 21 (70%) | 17 (68%) | 0.29‡ |

| Day of hospital stay, median (IQR) | 5.4 (2.4-8.4) | 9.1 (5.3-17.8) | 0.08§ |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 91.3 (26.7) | 76.9 (20.4) | 0.04† |

| APACHE II score, mean (SD) | 14.9 (7.0) | 16.1 (5.1) | 0.46† |

APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation.

Excluding demonstrated violence.

Student t test.

χ2 test for independence.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Most patients exhibiting violent behaviour were located in larger ICUs (20/25, 80%), were in Australia (23/25, 92%), and were male (17/25, 68%), but no difference was observed in the incidence of violence following adjustment for the number of admissions (Table 2 and Table 3). Patients displaying these behaviours were more likely to have been in hospital more than one week (4, 7 and 14 events; incidence, 2%, 4% and 7% for 0-2 days, 3-7 days and > 7 days respectively; P = 0.01) or in the ICU more than one week (8, 6 and 11 events; incidence, 2%, 4% and 9% for 0-2, 3-7 and > 7 days; P < 0.01). No difference in the incidence rates of patients displaying violence was observed between age cohorts following adjustment for admission rate (8%, 4% and 3% for 18-34, 35-65 and > 65 years respectively; P = 0.11); while those who did and did not display violent behaviour had similar Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores on the day of evaluation (16.1 v 16.9; P = 0.90), and showed no difference in 28-day in-hospital mortality (14% v 15%; P = 0.88).

Confusion was the most commonly perceived contributor to violent behaviour (16/25, 64%; Figure 1). Physical and psychiatric illness were perceived by bedside staff as a factor in ten out of 25 (40%) and nine out of 25 (34%) patients respectively, and illicit drugs use (either known or suspected) were documented as a contributor in five (20%) patients. Additional contributors noted in "other" include communication difficulties, pain, and medication side effects.

Figure 1.

Factors perceived to contribute to violence*

Fifty-three out of 627 patients (9%) were assessed by clinical staff as at risk of displaying future violent behaviour. Individuals considered a risk of future violence (excluding those previously exhibiting violent behaviour) were significantly heavier than those actually displaying violent behaviour (mean weight, 91.3 kg [SD, 26.7] v 76.9 kg [SD, 20.4]; P = 0.04). These cohorts did not differ according to age, sex, length of hospital stay or APACHE II score (Table 2 and Table 3).

Management of violence

In the event of violence, management strategies used during the study day included verbal de-escalation (20/25, 80%), chemical sedation (18/25, 72%), and mechanical restraint (7/25, 28%) (Figure 2). No activation of armed or unarmed response teams during the study day were reported. Additional strategies reported in "other" included cessation of causative medication or administration of analgesia. Five patients (20%) required vasopressor support due to complications of chemical restraint used for behavioural management, and three (12%) required endotracheal intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation. Of the 25 patients exhibiting these behaviours during the study period, 20 (80%) were assessed by clinical staff as an ongoing risk of further violent behaviour.

Figure 2.

Management implemented for violence*

Relevant procedures

Of the 44 participating units, 14 (32%) had no documented protocol, procedure or guideline relating to the assessment or management of violence risk (Figure 3). Among the 30 units with a protocol, the majority had a formal document (28/30, 93%), an incident-reporting system (26/30, 87%), and a rapid emergency response (23/30, 77%). A risk assessment tool and specialised staff were each available in about half of units with a protocol (16/30, 53%). Twelve units (12/30, 40%) had procedures across all surveyed domains. No difference between availability of documented procedures was observed between tertiary and non-tertiary units (75% v 63%; P = 0.10), public or private funding models (69% v 60%; P = 0.50), or by country (69% v 63%; P = 0.53; Online Appendix, table 1).

Figure 3.

Violence policy by unit*

Discussion

Key findings

This is the first study to describe the number of patients displaying violent behaviour in Australian and New Zealand ICUs. Each year there are over 180 000 admissions and more than 510 000 bed-days used across Australian and New Zealand ICUs.14,15 A daily prevalence rate of 4% of admissions would extrapolate to more than 20 000 patients displaying violent behaviour in Australian and New Zealand ICUs annually. It is of high concern that physical violence was directed towards ICU staff by 60% of the persons identified in this cohort, suggesting potentially over 12 000 episodes per year.

We present the first assessment of the frequency and nature of management strategies implemented in Australian and New Zealand ICUs in response to violent behaviour exhibited by patients. Unsurprisingly, chemical sedation is administered in most cases and mechanical restraint is used frequently. Notably, there was no reported use of specialist teams or strategies. Complications of chemical sedation for violent behaviour were significant and common, and over 10% of patients required endotracheal intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation as a complication of this management.

Relationship to previous research

The nature of violence events is better described in the emergency department (ED) context, where the barriers to establishing the true prevalence of such incidents have been reported. Retrospective analysis is prone to recall and sampling bias, especially when using voluntary convenience sampling.16 Violence in a health care setting is unusual in that it occurs in the context of care, and in the absence of an associated power status with the aggressor. Both these factors make the victim more likely to excuse violent behaviour on compassionate grounds.4 Reporting of violent episodes may be further impaired by system barriers such as time pressure, extended reporting processes, negative perceptions of utility, and the stigma of victimhood.4 In addition, the prevalence of violence is known to vary with the number of patients in the hospital catchment, the casemix of presentations, and societal and cultural factors.17

In contrast to previous results in the ED setting, our data showed a lower burden of violent behaviour related to substance intoxication or withdrawal.6 Confusion and physical illness may be under-recognised and important contributors to violence in the ICU, and potentially related to the increased risk of violent behaviour we observed with longer hospital and ICU admission. Our findings also suggest that there is a broader patient population at risk of displaying violent behaviour in the ICU compared with the ED, where violent patients are generally younger and male.6 Patients with a higher mass were perceived by clinicians to be a higher risk of violence, which suggests a contributory perception bias.

Despite the high prevalence of violence and aggression reported, formal procedures regarding violence varied greatly. This was consistent across unit size, country, and funding model. A significant number of ICUs have no procedures in this domain at all. Given the frequency of events reported in our study, it is likely that this represents a large health care burden in Australasian ICUs. Further studies would be required to explore the monetary cost, toll on staff wellbeing, and impact on longer term patient outcomes. Our study also did not capture episodes of violence from non-patient persons in the clinical environment, such as visitors and staff.

Strengths and limitations

We report the first study to our knowledge of the prevalence of violence in the ICU. The nature of the defined time-point retrospective data collection also allowed minimisation of the influence of recall bias and more accurate characterisation of the nature of events. The population sampled was multicentre and representative of the wider ICU population in Australasia,15 and resembles cohorts in previously conducted ANZICS CTG PPP studies.18, 19

Investigation of the relative prevalence and nature of policies regarding violence in critical care may guide future policy directions for intensive care societies, government, and local health boards to ensure staff safety in this complex domain.

The principal limitation of a study of this nature is the small absolute number of persons displaying violent behaviour. This leaves the study underpowered to perform comprehensive analysis to determine any associations between patient characteristics, risk of displaying violent behaviour, potential variations across different regions, funding types or underlying disease pathologies. We did not assess the absolute number of episodes of violent behaviour, their severity, the efficacy of their management, nor their effect on staff safety, stress or job satisfaction.

Our study was conducted mid-week and in the southern hemisphere winter, preventing assessment of variation that might be seen according to the day of the week or timing during the year. Perceived contributors are dependent on knowledge of a patient's history and presentation, which may be incomplete or prone to assumptions in the context of behavioural disturbance. We did not seek information on any known history of violent behaviour. Culturally and linguistically diverse social backgrounds were also not explored, nor did we seek information on whether a language other than English was spoken or an interpreter was used for verbal de-escalation and management. Only behaviours in the ICU were recorded, preventing evaluation of violent events across other hospital contexts and of the persistence of behaviour before admission or after discharge.

A study of this size and design cannot determine causative factors contributing to violent behaviour. Of note, a need still remains to identify predictive factors for violence during hospital admission. Similarly, the effect of violence on outcome data and the effect of documented policies on the incidence of violence are prone to many confounders. However, knowledge of the event rate, nature and risk factors for displaying violent behaviour in the ICU allows better targeting of resources and further investigation.

Conclusion

Violent behaviour among ICU patients is common and likely represents a significant burden to health care delivery in Australian and New Zealand ICUs. Procedures addressing violent behaviour are highly variable. The results of this study support the need for prospective research to clarify factors associated with violent behaviour in ICU patients, potential risk-modifying interventions, and the optimal management of violent behaviour, as well as to inform future guidance.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they do not have any potential conflict of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Adrian Tam for advice and assistance in the formulation of this study. Details of participating sites and investigators can be found in the Online Appendix, section 1.

Footnotes

Factors identified by the bedside nurse as potential contributors to episodes of violent behaviour. Multiple factors may be identified in a single patient

Management implemented in response to violent behaviour in the previous 24 hours, including rates of complications of chemical restraint.

Presence of violence policy by unit. The insert shows the types of policies present in units that have a formal policy, procedure or protocol to address violence. The subset shows the overall incidence of violence in units with and without a documented policy.

Supplementary Information

References

- 1.McDermid F., Mannix Judy, Peters K. Factors contributing to high turnover rates of emergency nurses: A review of the literature. Aust Crit Care. 2020;33:390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2002. Framework guidelines for addressing workplace violence in the health sector.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42617 (viewed July 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerberich S. An epidemiological study of the magnitude and consequences of work related violence: the Minnesota Nurses' Study. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:495–503. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.007294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy M. Violence in emergency departments: under reported, unconstrained, and unconscionable. Med J Aust. 2005;183:362–365. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb07084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiltz B., Gleich S., Ouellette Y. Prevalence of violence experienced by ICU providers: a national survey. Crit Care Med. 2019;48:29. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pol A., Carter M., Bouchoucha S. Violence and aggression in the intensive care unit: what is the impact of Australian National Emergency Access Target? Aust Crit Care. 2019;32:502–508. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian Standards . Planning for emergencies — health care facilities [AS 4083-2010] Australian Standards; 2020. Committee HE-026: hospital emergency procedures; pp. 21–22.https://www.standards.org.au/standards-catalogue/sa-snz/other/he-026/as--4083-2010 (viewed July 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health and Human Services . Victorian State Government; Melbourne: 2017. Code grey standards.http://www.health.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/files/collections/policies-and-guidelines/c/code-grey-standards-sep-2017-pdf.pdf (viewed July 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 9.New South Wales Health . NSW Government; Sydney: 2013. Protecting people and property: NSW health policy and standards for security risk management in NSW health agencies.https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/IB2013_024.pdf (viewed Dec 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Government of Western Australia Department of HealthEmergency management policy. 2017 https://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/About-us/Policy-frameworks/Public-Health/Mandatory-requirements/Disaster-Preparedness-and-Management/Emergency-Management-Policy (viewed July 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Queensland Health . Queensland Government; Brisbane: 2016. Occupational violence prevention in Queensland Health's hospital and health services.https://www.publications.qld.gov.au/dataset/queensland-health-reviews-and-investigations/resource/07bd0a3f-3cdd-4431-8e00-ba46caaab3db (viewed July 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson K., Hammond N., Eastwood G., et al. The Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group point prevalence program, 2009-2016. Crit Care Resusc. 2017;19:88–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris P., Taylor R., Thielke R., et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) — a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Centre for Outcome and Resource Evaluation 2018 report. ANZICS; Melbourne: 2018. https://www.anzics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2018-ANZICS-CORE-Report.pdf (viewed July 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Centre for Outcome and Resource Evaluation 2019 report. ANZICS; Melbourne: 2019. https://www.anzics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2019-CORE-Report.pdf (viewed July 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikathil S., Olaussen A., Gocentas R.A., et al. Review article: workplace violence in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta analysis. Emerg Med Australas. 2017;29:265–275. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavoie F.W., Carter G.L., Danzl D.F., Berg R.L. Emergency department violence in United States teaching hospitals. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:1227–1233. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(88)80076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammond N.E., Taylor C., Saxena M., et al. Resuscitation fluid use in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units between 2007 and 2013. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1611–1619. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3878-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parke R., Eastwood G., McGuinness S. Oxygen therapy in non-intubated adult intensive care patients: a point prevalence study. Crit Care Resusc. 2013;14:287–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials