Abstract

The XylR protein controls expression from the Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid upper pathway operon promoter (Pu) in response to aromatic effectors. XylR-dependent stimulation of transcription from a Pu::lacZ fusion shows different induction kinetics with different effectors. With toluene, activation followed a hyperbolic curve with an apparent K of 0.95 mM and a maximum β-galactosidase activity of 2,550 Miller units. With o-nitrotoluene, in contrast, activation followed a sigmoidal curve with an apparent K of 0.55 mM and a Hill coefficient of 2.65. m-Nitrotoluene kept the XylR regulator in an inactive transcriptional form. Therefore, upon binding of an effector, the substituent on the aromatic ring leads to productive or unproductive XylR forms. The different transcriptional states of the XylR regulator are substantiated by XylR mutants. XylRE172K is a mutant regulator that is able to stimulate transcription from the Pu promoter in the presence of m-nitrotoluene; however, its response to m-aminotoluene was negligible, in contrast with the wild-type regulator. These results illustrate the importance of the electrostatic interactions in effector recognition and in the stabilization of productive and unproductive forms by the regulator upon aromatic binding. XylRD135N and XylRD135Q are mutant regulators that are able to stimulate transcription from Pu in the absence of effectors, whereas substitution of Glu for Asp135 in XylRD135E resulted in a mutant whose ability to recognize effectors was severely impaired. Therefore, the conformation of mutant XylRD135Q as well as XylRD135N seemed to mimic that of the wild-type regulator when effector binding occurred, whereas mutant XylRD135E seemed to be blocked in a conformation similar to that of wild-type XylR and XylRE172K upon binding to an inhibitor molecule such as m-nitrotoluene or m-aminotoluene.

The TOL plasmid pWW0 of Pseudomonas putida encodes the enzymes for the metabolism of toluene and related hydrocarbons (36). The main regulator in the transcriptional control of the catabolic pathways is the XylR protein (reviewed in reference 31). The xylR gene is expressed constitutively from two tandem promoters (16, 20), but the regulator only induces expression from the target promoters in response to a wide variety of effectors (1). Activated XylR protein stimulates transcription from the Pu promoter for the upper operon, which encodes the enzymes for the oxidation of the aromatic hydrocarbons to the corresponding benzoates, and from the xylS Ps1 promoter, the regulator of the meta-cleavage pathway responsible for the further metabolism of aromatic carboxylic acid derivatives (12, 16, 21, 32). The Pu and Ps1 promoters belong to the ς54 class.

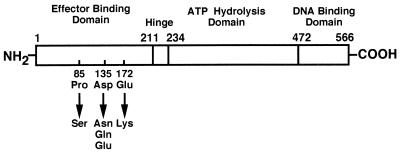

The XylR protein belongs to the NtrC family of transcriptional regulators (17, 25). These regulators exhibit four domains, three of which are highly conserved among members of the family (Fig. 1). The nonhomologous N-terminal domains have been implicated in signal reception, either via a sensory protein, as in the NtrB-NtrC pair (18, 24), or via interaction with a chemical signal, as in FhlR, DmpR, and XylR (31, 34). This has been genetically confirmed for the last two regulators, in which mutations in the N-terminal region altered effector recognition (6, 26). The central domains of these regulators contain an ATP binding domain, and ATPase activity is a sine qua non for transcriptional activity (34). At the C-terminal domain these regulators exhibit a typical helix-turn-helix DNA binding domain.

FIG. 1.

Domains of the XylR regulator and locations of point mutations. The organization of the XylR domains is according to Inouye et al. (17). The mutations located at the N-terminal end of this regulator are shown.

A surprising feature of the XylR regulator is that it recognizes a wide variety of effectors, namely, an aromatic benzene ring with certain mono-, di-, and trisubstituents. Toluene and benzyl alcohol are examples of monosubstituted benzene rings recognized by XylR. o-, m-, and p-xylene, o- and p-nitrotoluene, and m-methylbenzyl alcohol are examples of disubstituted aromatic rings recognized by XylR. 2,3-Dichlorotoluene is an example of a trisubstituted ring recognized by this regulator (1, 7).

Removal of the first 210 amino acids of the N-terminal domain of XylR results in a mutant regulator that stimulates transcription in the absence of effectors (10). This suggested that the N-terminal domain acts as an intramolecular inhibitor of the transcriptional activity of XylR (10). Because XylR binds persistently to target DNA sequences (2, 8) regardless of the presence of an effector, Pérez-Martín and de Lorenzo suggested that the N-terminal domain prevents either ATP binding or ATPase activity of this regulator (27–30).

We report that in vivo XylR-dependent transcription stimulation from the Pu promoter shows an effector dose-dependent response that gives rise to different induction kinetics with different effectors. The nature of the substituent on the aromatic ring of the effector is critical to bring XylR to a productive or an unproductive transcriptional state. These observations are being substantiated by mutant regulators with altered effector specificity (XylRE172K) or blocked in transcriptionally active (XylRD135N and XylRD135Q) or inactive (XylRD135E) forms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strain used in this work was Escherichia coli ET8000 [rbs lacZ::IS1 gyrA hutC(Con)] (22). Plasmids used were pTS174 (Cmr xylR, p15 replicon) (15); pAD1 (Cmr, carrying an xylR mutant allele encoding XylRE172K, p15 replicon) (6); pAD6, pAD49, pRS1, and pRS2, which were similar to pAD1 except that the mutant xylR allele encoded, respectively, XylRP85S, XylRD135N, XylRD135E, and XylRD135Q (reference 7 and this study); pRD579 (Apr Pu::lacZ, pR1 replicon) (9); and pERD401 (Apr Pu::lacZ, pBR replicon) (2). Plasmid pTS174ΔHincII was constructed in this study by deleting a HincII restriction fragment of plasmid pTS174. This removed a BglI site from pTS174 and resulted in a plasmid containing unique PstI and BglI sites within the xylR gene, facilitating the cloning of mutated PstI-BglI fragments of xylR. Bacteria were grown at 30°C in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented, when required, with 100 μg of ampicillin per ml and 30 μg of chloramphenicol per ml.

β-Galactosidase assays.

E. coli ET8000(pRD579 Pu::′lacZ) cells also bearing a plasmid encoding wild-type XylR or a mutant XylR protein were grown for 5 h with vigorous shaking in the absence or presence of effectors. β-Galactosidase activity was measured in permeabilized cells as described before (6), and activity was expressed in Miller units (23).

DNA techniques.

DNA manipulations were done according to standard procedures (33). The 5′ mRNA start of the upper operon transcript was determined by primer extension analysis (20). The oligonucleotide 5′-GATGTGCTGCAAGGCGATTAAGTTG-3′ was 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and annealed to 20 μg of total RNA prepared from E. coli ET8000(pERD401) also bearing pTS174.

Site-directed xylR mutagenesis.

XylR mutants were constructed by a PCR technique. The plasmid pTS174 was used as a template for the PCRs with a pair of internal oligonucleotides that carried the desired mutation and two external oligonucleotides. The internal oligonucleotide 5′-CCTTTGAAGTGGAGATCTGCC-3′ and its complementary oligonucleotide were used to replace Asp135 in XylR with Glu (the underlined nucleotide indicates the point mutation introduced to generate the desired substitution at the protein level). The oligonucleotide 5′-CCTTTGAAGTGCAGATCTGCC-3′ and its complementary oligonucleotide were used to replace Asp135 with Gln. As external oligonucleotides we used 5′-AGGCCTTGACGTTGCAAGGT-3′ and 5′-CCCACCCCAGTCTCACCC-3′. Both PCR products were purified and mixed, and the final PCR was carried out with the external oligonucleotides. The PCR products were digested with BglI and PstI and used to replace the wild-type sequence in plasmid pTS174ΔHincII to yield pRS1 (XylRD135E) and pRS2 (XylRD135Q). The single mutation in the mutant xylR alleles was confirmed by dideoxy sequencing.

RESULTS

Dose-dependent stimulation of transcription by XylR and XylRE172K.

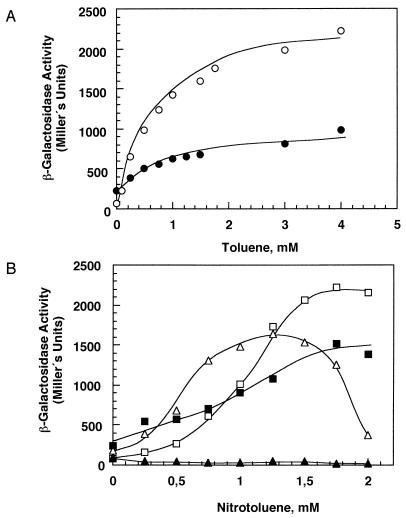

Activation of transcription in systems triggered by a chemical stimulus occurs above a certain threshold concentration of the effector molecule (4). The dose dependence of the activation of transcription from Pu by XylR was assayed in vivo by measuring the β-galactosidase activity resulting from the expression of lacZ in a strain bearing a Pu::′lacZ fusion. XylR-dependent activation of transcription from Pu with toluene followed a hyperbolic curve, with a maximum transcriptional activity of 2,550 ± 100 Miller units and an apparent K (Kapp) of 0.95 ± 0.08 mM (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained when m-aminotoluene was used as an effector for XylR (Kapp, 0.85 ± 0.15 mM; Vmax, 4,400 ± 450 Miller units), whereas m-nitrotoluene was not an effector for XylR (Table 1). However, when activation was assayed with o-nitrotoluene, transcription activation from Pu was observed. The o-nitrotoluene dose-dependent curve was sigmoidal in the range of 20 μM to 1 mM (Fig. 2B). The curve profiles yielded a Kapp of 0.55 ± 0.04 mM and a Hill coefficient of 2.65 ± 0.45. This suggests the existence of cooperative effects in the transcriptional process with o-nitrotoluene as an effector. A remarkable effect was the inhibition of transcription of wild-type XylR by concentrations of o-nitrotoluene above 1.5 mM (Fig. 2B). This inhibition suggests that above certain concentrations, o-nitrotoluene may have more than one binding mode in the binding pocket of XylR, with nonproductive binding resembling the binding of m-nitrotoluene, which acts as an inhibitor of transcription (7). XylRE172K is a mutant with altered effector specificity that was isolated as being able to recognize m-nitrotoluene as an effector (7). The E172→K mutation in XylR did not alter the profile of activation of Pu in response to toluene; it produced a hyperbolic curve similar to that of the wild-type regulator (Fig. 2A). However, the mutation increased the Kapp to 1.42 ± 0.25 mM and decreased the maximum activation to 1,150 ± 75 Miller units. Activation of transcription from Pu by XylRE172K in the presence of o-nitrotoluene followed a sigmoidal curve with an apparent Kapp of 1.12 ± 0.12 mM and a Hill coefficient of 3.62 ± 0.25 (Fig. 2B). This suggests that the E172→K mutation in the signal recognition domain of XylR resulted in an increase in cooperativity in XylR-dependent stimulation of transcription from Pu with o-nitrotoluene.

FIG. 2.

Dose dependence of the activation of transcription from Pu by XylR and XylRE172K in response to toluene and nitrotoluenes. E. coli ET8000(pRD579 Pu::′lacZ) also bearing pTS174 (encoding wild-type XylR) or pAD1 (encoding XylRE172K) was grown for 5 h with vigorous shaking in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of toluene or nitrotoluenes. The β-galactosidase activity was assayed in permeabilized cells as described in Materials and Methods. The data are the averages of at least five independent determinations. The results were fitted to hyperbolic or sigmoidal equations, and the values of Kapp and Hill’s coefficient were deduced from these equations. (A) Dose dependence of the activation of transcription from Pu by toluene. Open symbols, wild-type XylR; closed symbols, XylRE172K. (B) Dose dependence of the activation of transcription from Pu by nitrotoluenes. Triangles, wild-type XylR; squares, XylRE172K; open symbols, o-nitrotoluene; closed symbols, m-nitrotoluene.

TABLE 1.

Effector profiles of the activation of the Pu promoter by XylR and XylRE172Ka

| Effectorb | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)c with regulator:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| XylR (wild type) | XylRE172K | |

| None | 200 | 150 |

| m-MBA | 2,000 | 900 |

| Toluene | 1,980 | 1,000 |

| o-NT | 1,330 | 1,150 |

| m-NT | 130 | 850 |

| p-NT | 1,120 | 800 |

| o-AT | 510 | 350 |

| m-AT | 3,430 | 500 |

| p-AT | 540 | 350 |

E. coli ET8000(pRD579) also bearing pTS174 (encoding wild-type XylR) or pAD1 (encoding XylRE172K) was grown as described in Materials and Methods with the indicated aromatics at 1 mM.

MBA, methylbenzyl alcohol; NT, nitrotoluene; AT, aminotoluene.

Results are averages of at least five independent determinations. Standard deviations were on the order of 10 to 15% of the given values.

m-Nitrotoluene clearly inhibited the basal transcription levels of wild-type XylR (Table 1), whereas XylRE172K showed a sigmoidal profile of activation of transcription from Pu, with a Kapp of 0.91 ± 0.08 mM, a Hill coefficient of 1.46 ± 0.21 and a maximum transcriptional activity of 850 Miller units (Fig. 2B).

We found that m-aminotoluene–XylRE172K stimulation of transcription from Pu yielded low levels of activity compared with the level mediated by the wild-type XylR protein (Table 1). Therefore, a partial charge in the meta position of the aromatic ring may play a role in the activation of transcription from Pu by XylR. To test whether this change affected transcription stimulation by other nitro- and aminotoluenes, we assayed the activation of transcription from Pu by XylR and XylRE172K with p-nitrotoluene and o- and p-aminotoluene. o-Aminotoluene and p-aminotoluene were weak effectors of both wild-type XylR and the mutant XylRE172K; i.e., these effectors increased the basal transcriptional levels by about two- to threefold (Table 1). In contrast, p-nitrotoluene was as effective as m-methylbenzyl alcohol in stimulating transcription from Pu (Table 1).

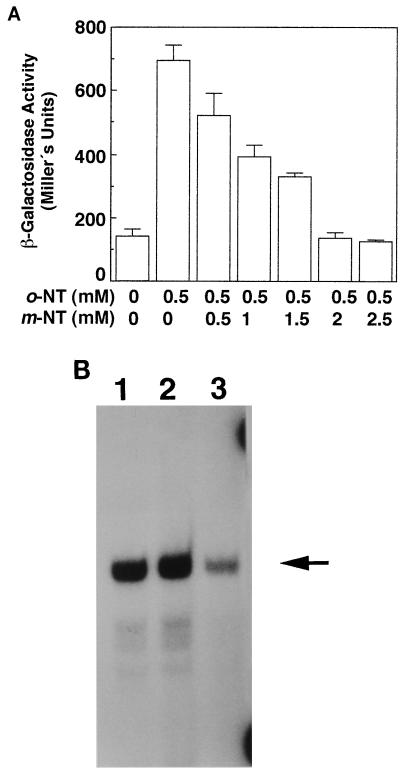

Further evidence for m-nitrotoluene being an inhibitor of transcription stimulation by wild-type XylR, XylRP85S, and XylRE172K.

As mentioned above, m-nitrotoluene is not an effector of XylR (6, 7) (Table 1). Furthermore, we noticed that basal transcription levels from Pu in the presence of this nitroarene were reduced (Table 1). The inhibitory effect of m-nitrotoluene was also confirmed by the fact that this nitroarene decreased o-nitrotoluene-dependent activation of transcription from Pu mediated by the wild-type XylR regulator: for a given o-nitrotoluene concentration, the higher the concentration of m-nitrotoluene, the lower the induction from Pu (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of XylR mediated by m-nitrotoluene. (A) Inhibition of expression from Pu mediated by XylR with o-nitrotoluene and m-nitrotoluene. E. coli ET8000(pRD579, pTS174) was grown for 5 h with vigorous shaking in the presence of 0.5 mM o-nitrotoluene (o-NT) and increasing concentrations of m-nitrotoluene (m-NT) (0 to 2.5 mM). After incubation, β-galactosidase activity was assayed in permeabilized cells as described in Materials and Methods. The data are the averages and standard deviations of at least five independent determinations. (B) mRNA synthesis from Pu mediated by XylRP85S in the absence of an aromatic (lane 1) and in the presence of m-methylbenzyl alcohol (lane 2) or m-nitrotoluene (lane 3). E. coli ET8000(pERD401, pAD6) was grown overnight on Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. Bacterial cells were diluted 1/100 in the same medium, and after 1 h of cell growth, the samples were supplemented with m-methylbenzyl alcohol or m-nitrotoluene to a final concentration of 1 mM. After 30 min, samples were withdrawn for mRNA analysis. The extended products (arrow) were 134 nucleotides long.

XylRP85S is a mutant regulator that is able to stimulate transcription from the Pu promoter in the absence of effector but that is able to increase expression from Pu in response to the presence of wild-type XylR effectors in the culture medium (7). To corroborate the inhibitory character of m-nitrotoluene, the mRNA levels induced by XylRP85S were assayed by primer extension in the absence of effectors and in the presence of m-methylbenzyl alcohol or m-nitrotoluene (Fig. 3B). In these assays, the transcription initiation point from Pu mediated by XylRP85S was the same regardless of the presence of an aromatic in the culture medium, and the results matched those of Inouye et al. (14). It was found that mRNA levels were higher in the absence of aromatics or in the presence of the aromatic alcohol, whereas in the presence of m-nitrotoluene expression from Pu was significantly reduced (Fig. 3B). This corroborates that m-nitrotoluene interferes with the regulatory activity of the XylR protein. In accordance with previous findings (6) and the assays described above, the wild-type-XylR-mediated transcript from Pu was also detected when the cells were grown in the presence of m-methylbenzyl alcohol but not when they were grown in the absence of an effector or in the presence of m-nitrotoluene (not shown).

Importance of the charge and size of the side chain of residue 135 in the constitutive activation of transcription by XylR mutants.

XylRD135N is a mutant regulator that is able to stimulate transcription from Pu and Ps1 in the absence of effectors. To further study the role of position 135 in the stimulation of transcription from Pu, the Asp residue at position 135 in the wild-type protein was replaced with Glu or Gln to test the importance of the charge and size of the side chain at this position.

Plasmids encoding wild-type XylR or the mutant XylR proteins were transformed in ET8000(pRD579), and β-galactosidase activity was measured in the absence of effectors and in the presence of 1 mM toluene, m-methylbenzyl alcohol, and the three isomers of mononitrotoluene (Table 2). The results showed that in the absence of effectors, the mutant XylRD135Q mediated a sixfold-higher basal level of expression from the Pu promoter than the wild-type regulator. Therefore, the substitution of Gln for Asp at position 135 had the same effect as the substitution for Asn in the stimulation of transcription from Pu in the absence of effectors. In contrast, the basal expression levels of mutant XylRD135E were similar to those mediated by the wild-type protein (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Activation of the Pu promoter by XylR, XylRD135N, XylRD135E, and XylRD135Qa

| Effectorb | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)c with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XylR (wild type) | XylRD135Q | XylRD135N | XylRD135E | |

| None | 200 | 1,230 | 2,160 | 90 |

| m-MBA | 2,000 | 2,520 | 2,400 | 230 |

| Toluene | 1,980 | 2,140 | 2,590 | 240 |

| o-NT | 1,330 | 3,190 | 2,460 | 100 |

| m-NT | 130 | 1,130 | 1,060 | 20 |

| p-NT | 1,120 | 2,240 | 1,630 | 40 |

E. coli ET8000(pRD579) also bearing pTS174 (encoding wild-type XylR), pAD49 (encoding XylRD135N), pRS1 (encoding XylRD135E), or pRS2 (encoding XylRD135Q) was grown as described in Materials and Methods with the indicated aromatics at 1 mM.

MBA, methylbenzyl alcohol; NT, nitrotoluene.

Results are averages of at least five independent determinations. Standard deviations were on the order of 10 to 15% of the given values.

When the stimulation of transcription was assayed in the presence of effectors, the high basal level of transcription mediated by XylRD135Q increased between two- and threefold in response to the addition of toluene, m-methylbenzyl alcohol, or o- or p-nitrotoluene. In contrast, m-nitrotoluene had no significant effect on transcription from Pu. Stimulation of transcription in the presence of effectors mediated by the XylRD135E mutant was negligible (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The XylR protein induces expression of the TOL plasmid upper pathway by stimulating transcription from the Pu promoter (11, 16, 32) and is involved through a cascade regulatory system in activation of the meta pathway for the metabolism of alkyl benzoates (31). XylR binds persistently to its target sequences in the Pu and Ps1 promoters (2, 8); conversion from the inactive to the active form of XylR and induction of transcription are regulated by the presence of aromatic compounds in the medium (1). In vitro studies with the highly homologous DmpR regulator have shown that effector binding to DmpR activates an ATPase activity which lies in the central domain (36). Large deletions in the amino-terminal domain of XylR or DmpR resulted in high rates of ATP hydrolysis by the ATPase activity of these regulators, and consequently they stimulated transcription from the corresponding promoters in the absence of effectors (10, 27–29, 35). This mechanism has also been described for other members of the family that are activated by covalent modification (3, 5, 13, 19).

On the basis of these findings, a model for the activation of XylR and the stimulation of transcription by this regulator is emerging: the N-terminal domain of XylR, in the absence of effectors, prevents either ATP binding or the ATPase activity of this regulator, and hence the regulator is maintained in an inactive form from a transcriptional point of view. Upon binding to effector molecules, the N-terminal domain undergoes conformational changes that allow binding of ATP; this in turn induces further conformational changes that lead to XylR multimerization and increase the ATPase activity of the regulator, which in turn stimulates transcription (27–29).

The first steps in this model—interaction between effectors and the regulator and how the conformational change induced upon effector binding is transmitted to the other domains of XylR—are poorly understood. An interesting aspect of XylR activation by effectors is the dose dependence and the type of kinetic induction. Transcription activation from Pu with toluene-activated and m-aminotoluene-activated XylR followed hyperbolic curves, whereas the response to increasing concentrations of o-nitrotoluene followed a sigmoidal curve. Therefore, the binding of different effector molecules may produce distinct conformational changes in the N-terminal domain of XylR that modulate transcription activation. This may result in cooperative interactions of XylR monomers to achieve the active multimeric XylR state (29); alternatively, it may reflect cooperativity for ATP hydrolysis or cooperativity in the interaction with the transcriptional machinery located in the downstream promoter. XylR is not able to activate transcription with m-nitrotoluene (7); moreover, this compound inhibits basal activity of the wild-type protein and significantly decreases the high basal mRNA levels mediated by the constitutive mutant XylRP85S. These facts suggest that m-nitrotoluene interacts with XylR but that the conformational changes in the protein upon binding to the aromatic are counterproductive.

The Glu172→Lys change in the N-terminal domain of XylR reversed this response: mutant XylRE172K induced transcription in the presence of m-nitrotoluene but showed low activity with m-aminotoluene. These results suggest that residue 172 of XylR is probably involved in interactions with effectors, although a more detailed study of substituents on the ring is still needed to define the specificity for interactions with substituents on the aromatic ring. In any case, our results support a model in which interaction of effector molecules with the N-terminal domain of XylR can lead to two different conformational states. One of them is productive; the inhibition that the N-terminal domain exerts over the rest of the regulatory protein is abolished, allowing stimulation of transcription. In the other, an unproductive state, the N-terminal domain is probably locked into a conformation that keeps the N-terminal module in an inhibitory state.

The Asp135 residue in XylR may also be involved in effector recognition and/or conformational changes upon effector binding, as suggested by the finding that a previously isolated XylRD135N mutant induced a high level of transcription in the absence of effectors. Using site-directed mutagenesis, we generated mutants XylRD135E and XylRD135Q. The conservative mutation Asp135→Glu produced a mutant regulator that was unable to recognize effectors. This may be because the regulator was locked into a conformation that prevented either interactions with effectors or transmission of the conformational change produced upon binding of the effector to the other domains of the protein. Substitution of Gln for Asp135 yielded a regulator with high basal activity in the absence of effectors. This activity was still enhanced in the presence of effector molecules that activated the wild-type regulator. These results emphasize the role that the removal of the negative charge of Asp135 plays in locking the XylR protein into a conformation that activates transcription.

In summary, the role of the N-terminal domain in the modulation of XylR activity is demonstrated by (i) the existence of activator and inhibitor molecules of XylR, as well as the change in the character of these molecules caused by point mutations at position 172 of the regulator, and (ii) the point mutations at position 135 that lock the regulator into an active conformation that mimics that produced by effector binding (XylRD135N and XylRD135Q) or by a mutation (XylRD135E) that blocks the protein in a conformation unable to stimulate transcription.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Rafael Salto and Asunción Delgado contributed equally to the experimental work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abril M A, Michán C, Timmis K N, Ramos J L. Regulator and enzyme specificities of the TOL plasmid-encoded upper pathway for degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons and expansion of the substrate range of the pathway. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6782–6790. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6782-6790.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abril M A, Buck M, Ramos J L. Activation of the Pseudomonas TOL plasmid upper pathway operon. Identification of binding sites for the positive regulator XylR and for integration host factor protein. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15832–15838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin S, Lambert J. Purification and in vitro activity of a truncated form of AnfA, the transcriptional activator protein of alternative nitrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18141–18148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bally M, Wilberg E, Kuhni M, Egli T. Growth and regulation of enzyme synthesis in the nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA)-degrading bacterium Chelatobacter heintzii ATCC 29600. Microbiology. 1994;140:1927–1936. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger D, Naberhaus F, Kustu S. The isolated catalytic domain of NifA, a bacterial enhancer-binding protein, activates transcription in vitro: activation is inhibited by NifL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:103–107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delgado A, Ramos J L. Genetic evidence for activation of the positive transcriptional regulator XylR, a member of the NtrC family of regulators, by effector binding. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8059–8062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delgado A, Salto R, Marqués S, Ramos J L. Single amino acids changes in the signal receptor domain of XylR resulted in mutants that stimulate transcription in the absence of effectors. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5144–5150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Metzke M, Timmis K N. An upstream XylR and IHF induced nucleoprotein complex regulates the ς54-dependent Pu promoter of TOL plasmid. EMBO J. 1991;10:1159–1167. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon R. The xylABC promoter from the Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid is activated by nitrogen regulatory genes in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;203:129–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00330393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernández S, de Lorenzo V, Pérez-Martín J. Activator of the transcriptional regulator XylR of Pseudomonas putida by release of repression between functional domains. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franklin F C H, Lehrbach P R, Lurz R, Rueckert B, Bagdasarian M, Timmis K N. Localization and functional analysis of transposon mutations in regulatory genes of the TOL catabolic pathway. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:676–685. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.2.676-685.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallegos M T, Marqués S, Ramos J L. Expression of the TOL plasmid xylS gene in Pseudomonas putida occurs from a ς70-dependent promoter or from ς70- and ς54-dependent tandem promoters according to the aromatic compound used for growth. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2356–2361. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2356-2361.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huala E, Stigter J, Ausubel F M. The central domain of Rhizobium leguminosarum DctD functions independently to activate transcription. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1428–1431. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1428-1431.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inouye S, Ebina Y, Nakazawa A, Nakazawa T. Nucleotide sequence surrounding transcription initiation site of xylABC operon on TOL plasmid of Pseudomonas putida. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1688–1691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.6.1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inouye S, Nakazawa A, Nakazawa T. Molecular cloning of regulatory gene xylR and operator promoter regions of the xylABC and xylDEGF operons of the TOL plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:1192–1199. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.3.1192-1199.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inouye S, Nakazawa A, Nakazawa T. Expression of the regulatory gene xylS on the TOL plasmid is positively controlled by the xylR gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5182–5186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inouye S, Nakazawa A, Nakazawa T. Nucleotide sequence of the regulatory gene xylR of the TOL plasmid from Pseudomonas putida. Gene. 1988;66:301–306. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keener J, Kustu S. Protein kinase and phosphoprotein phosphatase activities of nitrogen regulatory proteins NTRB and NTRC of enteric bacteria: roles of the conserved amino-terminal domain of NTRC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4976–4980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J L, Scholl D, Dixon B T, Hoover T. Constitutive ATP hydrolysis and transcription activation by a stable truncated form of Rhizobium meliloti DctD, a ς54-dependent transcriptional activator. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20401–20409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marqués S, Holtel A, Timmis K N, Ramos J L. Transcriptional induction kinetics from the promoters of the catabolic pathways of TOL plasmid pWW0 of Pseudomonas putida for metabolism of aromatics. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2517–2524. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2517-2524.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marqués S, Ramos J L, Timmis K N. Analysis of the mRNA structure of the Pseudomonas putida TOL meta fission pathway operon around the transcription initiation point, the xylTE and the xylFJ regions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1216:227–236. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNeil D. General method, using Mu-Mud1 dilysogens, to determine the direction of transcription of and generate deletions in the glnA region of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:260–268. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.1.260-268.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ninfa A J, Magasanik B. Covalent modification of the glnG product, NRI, by the glnL product, NRII, regulates the transcription of the glnALG operon in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5909–5913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.North A K, Klose K, Stedman K M, Kustu S. Prokaryotic enhancer-binding proteins reflect eukaryote-like modularity: the puzzle of nitrogen regulatory protein C. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4267–4273. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.14.4267-4273.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavel H, Forsman M, Shingler V. An aromatic effector specificity mutant of the transcriptional regulator DmpR overcomes the growth constraints of Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600 on para-substituted methylphenols. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7550–7557. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7550-7557.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pérez-Martín J, de Lorenzo V. Physical and functional analysis of the prokaryotic enhancer of the ς54-promoters of the TOL plasmid of Pseudomonas putida. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:562–574. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pérez-Martín J, de Lorenzo V. In vitro activities of an N-terminal truncated form of XylR, a ς54-dependent transcriptional activator of Pseudomonas putida. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:575–587. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pérez-Martín J, de Lorenzo V. ATP binding to the ς54-dependent activator XylR triggers a protein multimerization cycle catalyzed by UAS DNA. Cell. 1996;86:331–339. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pérez-Martín J, de Lorenzo V. Identification of the repressor subdomain within the signal reception module of the prokaryotic enhancer-binding protein XylR of Pseudomonas putida. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7899–7902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.7899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramos J L, Marqués S, Timmis K N. Transcriptional control of the Pseudomonas TOL plasmid catabolic operons is achieved through an interplay of host factors and plasmid encoded regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;31:341–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramos J L, Mermod N, Timmis K N. Regulatory circuits controlling transcription of TOL plasmid encoding meta-cleavage pathway for degradation of alkylbenzoates by Pseudomonas. Mol Microbiol. 1987;1:297–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1987.tb01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shingler V. Signal sensing by ς54-dependent regulators: activation and its functional consequences. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1555–1560. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.388920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shingler V, Pavel H. Direct regulation of the ATPase activity of the transcriptional activator DmpR by aromatic compounds. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:505–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17030505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Worsey M J, Williams P A. Metabolism of toluene and xylenes by Pseudomonas putida (arvilla) mt-2: evidence for a new function of the TOL plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1975;124:7–13. doi: 10.1128/jb.124.1.7-13.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]