Abstract

Background

We conducted a study to evaluate the risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) and atrial flutter (AFL) in periodontal disease (PD) patients.

Methods

Cohort studies that evaluate the risk of AF or AFL in PD patients were included. The risk was expressed in the pooled odd ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

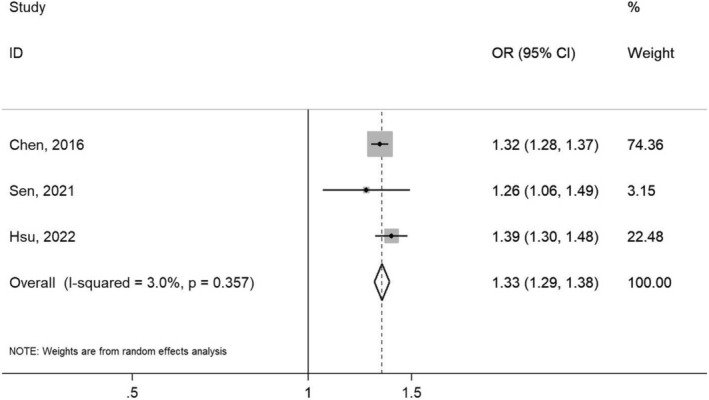

A total of four cohort studies were included. We found that patients with PD have a significantly higher risk of AF/AFL compared to those without PD with the pooled OR of 1.33 (95% CI 1.29–1.38; p = 0.357, I 2 = 3.0%).

Conclusions

PD increases the risk of AF and AFL.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, cardiovascular disease, periodontal disease

1. INTRODUCTION

Periodontal disease (PD) is a chronic inflammatory disease caused by the accumulation of dental plaque that triggers an immune response. 1 Studies have found that individuals with PD are at a higher risk of developing cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Recent evidence suggested the possibility of an association between PD and atrial fibrillation (AF). 2 AF and atrial flutter (AFL) have a significant impact on morbidity and mortality and can lead to various complications such as stroke, systemic thromboembolism, dementia, heart failure, and myocardial infarction. These complications not only affect the quality of life but also increase healthcare costs. 3 In this systematic review and meta‐analysis, we aim to evaluate the relationship between PD and AF/AFL.

2. METHODS

A literature search was performed in the MEDLINE, EMBASE, and SCOPUS, using the search terms “periodontal” and “atrial fibrillation,” “periodontitis” and “atrial fibrillation,” and “periodontal” and “atrial flutter”. Studies were included if they were human studies, cohort or case–control studies, and required to report the association between AF or AFL and PD or report the incidence of AF or AFL comparing patients who had PD and patients who did not have PD. AF or AFL was identified from the diagnosis codes or death certificates using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) codes or by a standard 12‐lead ECG. PD was defined differently among the four studies that were included. It was defined by ICD‐9‐CM code together with receiving antibiotic therapy or periodontal treatment in one study. Another study defined PD by diagnosis code and subgingival curettage treatment code. Another study defined PD if meeting the World Health Organization Community Periodontal Index greater than or equal to code 3 of periodontitis diagnosis. The last study defined PD according to the Periodontal Profile Class.

The risk of AF or AFL in PD was expressed in the pooled odd ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). All statistical analyses in this meta‐analysis were performed using STATA 14.2 software.

3. RESULTS

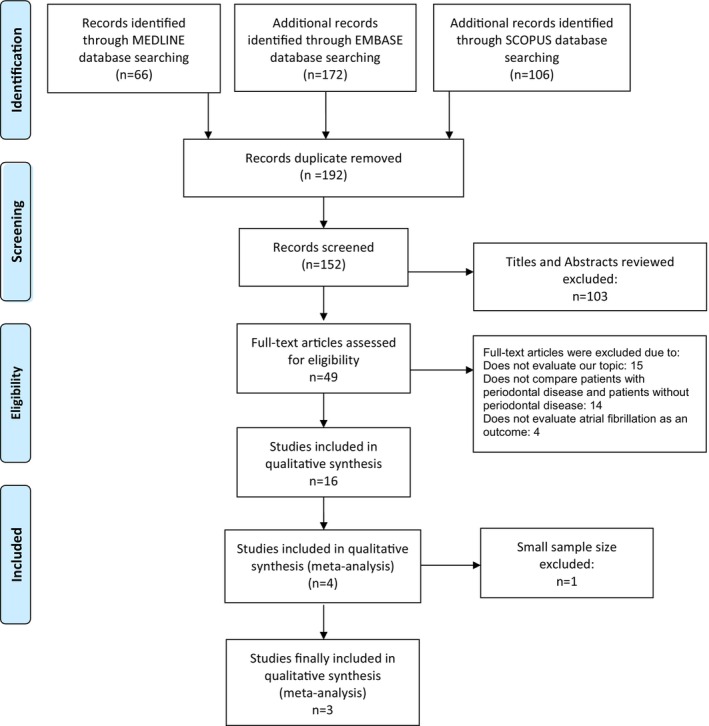

Our search strategy yielded 344 results. A total of 4 cohort studies met the inclusion criteria. 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 However, one study 6 was further excluded because of a small sample size resulting in a larger confidence interval. A final of 3 studies 2 , 4 , 5 including 1 358 568 patients (680 549 with PD and 677 974 without PD) were included in the study. Figure 1 outlines our search methodology and selection process; the baseline characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. We found that the patients who had PD had a 33% increased risk of having AF or AFL compared to patients who did not have PD (pooled OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.29–1.38; p = .357, I 2 = 3.0%) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Prisma flow diagram demonstrates search methodology and selection process. For more information, visit www.prisma‐statement.org.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of studies in the meta‐analysis that investigate the association between periodontal disease and atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter.

| First author/year | Country | Study design | Patients (n) | Study population/inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Periodontal disease diagnosis | Atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Periodontal disease | Nonperiodontal disease | |||||||

| Chen/2016 | Taiwan | A retrospective cohort | 393 745 | 393 745 | Participants from The Taiwanese National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) included patients with PD and non‐PD that were individually matched with a 1:1 ratio based on gender and individual age | Previous diagnoses of AF or AFL | A diagnosis code (ICD9‐CM Codes 523.3–5) | A diagnosis code (ICD9‐CM Codes 427.31–2) |

| Hsu/2022 | Taiwan | A retrospective cohort | 282 560 | 282 560 | Participants from The Taiwanese National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) included patients with periodontitis and nonperiodontitis that were individually matched with a 1:1 ratio based on age, urbanization level, income, and index day | Prior stroke | A diagnosis code 523.X with subgingival curettage treatment code (91006–91 008) | N/A |

| Sen/2021 | United States | A prospective cohort | 4289 | 1669 | Participants from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study | Prior AF, participants with medical contraindications to a dental exam, those with dental implants only, not African American or white (because of limited sample size of other races) | The periodontal profile class (PPC); periodontal health (PPC‐A), mild PD (PPC‐B and C), moderate PD (PPC‐D and E), and severe PD (PPCF and G) | A standard 12‐lead ECG, hospitalization, and death certificates using ICD‐9‐CM codes 427.31 or 427.32 |

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of the included studies that evaluate the risk of developing atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter between patients with and without periodontal disease.

4. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta‐analysis to assess the risk of AF and AFL associated with PD. We found that PD is associated with an increased 1.3‐fold risk of AF and AFL.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the potential link between PD and CVD with systemic inflammation being one of the most important. 7 Multiple studies demonstrated that patients who have higher levels of c‐reactive protein (CRP) have a greater risk of acute myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events. 8 Inflammation is a key pathophysiologic factor of AF. Chronic inflammation in the atrial leads to fibrosis and dilatation, which can disrupt the normal electrical activity of the heart and increase risk of AF. This process is referred to as atrial remodeling. 9 The high incidence of AF in a state of the inflammatory process such as postcardiac surgery also suggested the link between inflammation and AF. 10 Studies have reported an association between inflammatory markers, such as CRP and interleukin‐6 (IL‐6), and AF. 9 Furthermore, Im et al. found that AF patients with periodontitis had a higher risk of major cardiac events compared to those without periodontitis. The study also found that patients with periodontitis had a higher prevalence of other arrhythmias, including atrial premature beat, atrial tachycardia, and ventricular tachycardia. 6 Not only we found an elevation of inflammatory markers in AF, but an elevation of CRP and IL‐6 is also seen in PD as well, 2 and there is a reduction of inflammatory markers including CRP, IL‐6, and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha after dental treatment. 11 This may be a reasonable presumption based on the evidence available that decreasing systemic inflammation through dental treatment could potentially lower the risk of developing AF and improve prognosis in patients who have established AF diagnosis.

Not only inflammation, but platelet and coagulation cascade activations also play a role in the development of AF and lead to consequent AF thrombotic complications. 9 The study in 76 AF patients suggests that periodontitis is not only positively correlated with LAA fibrosis but also with the presence of atrial thrombi, further highlighting the potential link between poor dental health and cardiovascular event. 12

The current 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with AF emphasizes addressing the risk factors as one of the treatment approaches for AF. 13 Weight reduction resulted in a reduction in AF burden with the explanation that obesity is associated with a systemic proinflammatory state and diastolic dysfunction. 14 Thus, reducing systemic inflammatory conditions by promoting oral hygiene care could be another easy way to reduce the risk of developing AF.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our study suggested that PD is associated with an increased risk of AF/AFL. Thus, better oral health might be an easily modifiable risk factor to reduce the risk of developing AF/AFL. However, more research is needed to clarify the relationship to identify the most effective strategy for preventing and managing both conditions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT, PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT, AND CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

Not applicable.

Leelaviwat N, Kewcharoen J, Poomprakobsri K, Trongtorsak A, Del Rio‐Pertuz G, Abdelnabi M, et al. Periodontal disease and risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter: A systematic review and meta‐analysis . J Arrhythmia. 2023;39:992–996. 10.1002/joa3.12921

REFERENCES

- 1. Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sen S, Redd K, Trivedi T, Moss K, Alonso A, Soliman EZ, et al. Periodontal disease, atrial fibrillation and stroke. Am Heart J. 2021;235:36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Staerk L, Sherer JA, Ko D, Benjamin EJ, Helm RH. Atrial fibrillation: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical outcomes. Circ Res. 2017;120(9):1501–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen DY, Lin CH, Chen YM, Chen HH. Risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter associated with periodontitis: a nationwide, population‐based, cohort study. PloS One. 2016;11(10):e0165601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hsu PW, Shen YW, Syam S, Liang WM, Wu TN, Hsu JT, et al. Patients with periodontitis are at a higher risk of stroke: a Taiwanese cohort study. J Chin Med Assoc. 2022;85(10):1006–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Im SI, Heo J, Kim BJ, Cho KI, Kim HS, Heo JH, et al. Impact of periodontitis as representative of chronic inflammation on long‐term clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation. Open Heart. 2018;5(1):e000708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Demmer RT, Desvarieux M. Periodontal infections and cardiovascular disease: the heart of the matter. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(Suppl):14S–20S. quiz 38S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fischer RG, Lira Junior R, Retamal‐Valdes B, Figueiredo LC, Malheiros Z, Stewart B, et al. Periodontal disease and its impact on general health in Latin America. Section V: treatment of periodontitis. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34(supp1 1):e026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carrizales‐Sepúlveda EF, Ordaz‐Farías A, Vera‐Pineda R, Flores‐Ramírez R. Periodontal disease, systemic inflammation and the risk of cardiovascular disease. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27(11):1327–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bruins P, Velthuis H, Yazdanbakhsh AP, Jansen PGM, van Hardevelt FWJ, de Beaumont EMFH, et al. Activation of the complement system during and after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery: postsurgery activation involves C‐reactive protein and is associated with postoperative arrhythmia. Circulation. 1997;96(10):3542–3548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sun WL, Chen LL, Zhang SZ, Ren YZ, Qin GM. Changes of adiponectin and inflammatory cytokines after periodontal intervention in type 2 diabetes patients with periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol. 2010;55(12):970–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goette A. Is periodontitis a modifiable risk factor for atrial fibrillation substrate? JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2023;9(1):54–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. January CT et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(8):e66–e93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abed HS, Wittert GA, Leong DP, Shirazi MG, Bahrami B, Middeldorp ME, et al. Effect of weight reduction and cardiometabolic risk factor management on symptom burden and severity in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(19):2050–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]