Abstract

Complex multilayer film structures were fabricated through a custom-built angular DC magnetron co-sputtering system. In this system, separate Cu, Al, and brass (Cu + Zn) targets were mounted on three magnetron guns, working in conjunction with a rotating substrate. This study aimed to compare the properties of films with intricate structures, which were sputtered onto glass slides and polypropylene substrates. The sputtering process was optimized using a Box–Behnken design, considering three variable operating conditions: substrate rotation speed, sputtering time, and sputtering voltage. The Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) results for film thickness and roughness, sputtered with three different materials onto glass slides and polypropylene (PP) substrates, indicated that all three independent variables significantly influenced the optimum response, with P-values less than 0.05 (<α = 0.05). The optimal conditions for maximizing the thickness and roughness of the sputtered film on PP substrates differed from those obtained for the thin-film properties of the sputtered film on glass slide substrates. Top-view images of the surface morphology revealed a dense and granular structure for the film deposited on the glass slide, whereas some grooves between the grains and fractures were observed in the film on the PP substrate.

Additionally, it was evident that these sputtered multilayer films exhibited a complex structure, as reflected in the uniform and homogeneous distribution of Cu, Al, and Zn atoms on both glass slides and PP substrates.

Keywords: Magnetron sputtering, Angular sputtering, Co-sputtering, Multilayer sputtering

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Magnetron sputtering is a physical vapor deposition process [1,2] widely used in various target-substrate configurations, typically categorized as planar and angular systems. In planar systems [3,4], the target surface is arranged parallel to the substrate surface, either horizontally or vertically, while angular systems [5,6] employ a tilted target surface-configured target substrate, oriented in a top-down [7] or bottom-up [8,9] vertical direction. In both laboratory and industrial applications, planar and angular systems often utilize multiple cooperative magnetron targets, each equipped with two or more magnetron guns, to produce multilayer thin films. These sputtering techniques find diverse applications in the coating of solar cells [10], semiconductors [11], sensors [12], optoelectronic devices [13], and cutting tools [14]. In simpler methods like “co-sputtering” or “co-layering,” all targets in the sputtering system consist of the same pure materials and are mounted onto multiple magnetron guns. By repeating the sputtering process with more than one layer, a multilayer film is formed. Conversely, when each target comprises different pure materials and is separately mounted on each magnetron gun, a multilayer film is produced through simultaneous sputtering. This film exhibits a complex structure and may also be a multi-component or alloy film [15]. While it is possible to create an alloy or compound target [16,17] for producing alloy films or complex structural films with single or multiple targets in planar or angular sputtering systems, the production of homogeneous alloy targets is often more challenging than the film production itself. Hence, the advantage of an angular co-sputtering system with three tilted magnetron guns lies in its use of different pure materials, mounted separately on each gun. Consequently, complex structural films are fabricated by combining atoms from various pure materials without the need for alloy targets. The resulting composite sputtered film inherits the specific properties of each material or a combination of properties from two or more components [18].

An angular co-sputtering process, when combined with a rotating substrate, leads to an orderly arrangement of atoms in the deposited film. Such films exhibit excellent coalescence, strong compatibility with the substrate, high density, low porosity, and remarkable homogeneity [19].

In the automotive industry, there is a growing interest in applying magnetron sputtering to coat plastic components with alloys. This interest stems from the widespread use of various polymers, including plastics and elastomers, to replace traditional metallic vehicle parts [[20], [21], [22]]. Among these, polypropylene (PP) is the most commonly used plastic for both interior and exterior automotive components [20]. Although modern plastics come in a wide range of colors and surface finishes, there is still a need for aesthetic painting in some cases. Painting serves purposes such as color matching with the vehicle body, enhancing gloss or color brilliance, simplifying manufacturing, concealing part imperfections, and eliminating manufacturing defects [23]. Consequently, multilayer coatings on plastic surfaces present a viable solution for preparing plastic surfaces suitable for colored paint.

This study aims to compare the properties of films with complex structures using a custom-built angular DC magnetron co-sputtering system. The films were deposited onto glass slides and polypropylene (PP) substrates and optimized based on the Box–Behnken design (BBD), which employs response surface methodology.

2. Experimental

2.1. Preparation of the coatings

Complex multilayer thin films were deposited onto glass slides and polypropylene (PP) substrates at room temperature (30 °C–35 °C) using a custom-built angular DC magnetron co-sputtering system. This specialized system featured copper, aluminum, and brass (Cu + Zn) target materials [24,25]. The configuration of this system is designed as a top-down system, comprising three magnetron guns inclined at a 30° angle relative to the substrate holder orientation. The target materials are cylindrical, with diameters of 4.4 cm and thicknesses of 0.5 cm. The cathode pole was connected in parallel to the electrical circuits of the three magnetron guns, ensuring equal discharge power on each magnetron gun. The positive pole was directly linked to the anode ring of the rotary substrate holder beneath the substrate table, using a high-voltage cable routed through a feedthrough device. The distance between the target and substrate was precisely 1.07 cm, measured vertically from the lowest point of the gun to the upper substrate surface (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Custom-built angular DC magnetron co-sputtering system.

The chamber was initially evacuated using a two-stage rotary pump, reaching a base pressure of approximately 20 mTorr within a 30-min timeframe. This step was essential to ensure the deposition of a high-purity film. Subsequently, argon gas was introduced into the vacuum chamber at a controlled flow rate of 30 sccm, facilitated by a mass flow controller. This introduction raised the working pressure inside the chamber to approximately 200 mTorr, a process that took only 3 min.

2.2. Experimental design

The chamber was initially evacuated using a two-stage rotary pump, achieving a base pressure of approximately 20 mTorr over the course of 30 min. This step was crucial to guarantee the deposition of a high-purity film. Following this evacuation, argon gas was introduced into the vacuum chamber through a mass flow controller at a controlled flow rate of 30 sccm. This introduction rapidly increased the working pressure inside the chamber to approximately 200 mTorr, a process that was completed in just 3 min.

The Box-Behnken design (BBD) is particularly effective for experiments involving three factors and three levels (Table 1), and in this study, the BBD was employed to plan 15 runs of the experiment for data collection. The thickness and roughness of the thin films were quantified using atomic force microscopy (AFM). Subsequently, the acquired data, representing the response variables associated with the three factors, underwent statistical analysis to ascertain the impact of each factor with a 95 % confidence level (α = 0.05). To determine the optimal settings for each parameter, a second-order polynomial model was employed. This model was fitted to establish the relationship between the factors and the response variables. Additionally, a desirability function (D) was utilized, assigning values between 0 and 1 to the potential outcomes of each response. A D value of 0 indicated a completely undesirable response, while a D value of 1 indicated a highly desirable or ideal response.

Table 1.

Sputtering parameters.

| Parameter (unit) | Symbol | Level of parameters |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Intermediate | High | ||

| Substrate rotation speed (rpm) | S | 10 | 30 | 50 |

| Sputtering time (min) | T | 6 | 8 | 10 |

| Sputtering voltage (V) | V | 150 | 175 | 200 |

Furthermore, the structural characterization of the films and their chemical compositions were thoroughly examined through scanning electron microscopy (SEM), specifically utilizing the JSM-IT800 model, in conjunction with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS).

3. Results

3.1. Film thickness and surface roughness

In the Box-Behnken Design (BBD) experiments, a total of 15 results were observed and employed to establish the model through least squares analysis. The response variables in focus were the thickness and roughness of the thin film, which were influenced by the three factors. These factors were incorporated into a second-order polynomial equation derived from the experimental data, employing quadratic regression models. For reference, Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the properties of the sputtered thin films, highlighting the outcomes associated with the three target materials and the three variables under investigation.

Table 2.

Results of thin film properties sputtered by three target materials onto glass slide and PP substrates.

| Standard Order | Variables (Coded) | Voltage | Current | Power | Thin Film Properties on Glass Slide | Thin Film Properties on PP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run | S | T | V | (V) | (mA) | (W) | Thickness (nm) | Roughness (nm) | Thickness (nm) | Roughness (nm) |

| 1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 312 | 65 | 20.28 | 41.92 | 46.18 | 87.10 | 58.12 |

| 2 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 304 | 65 | 19.76 | 32.89 | 36.43 | 79.60 | 66.15 |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 314 | 65 | 20.41 | 49.98 | 52.88 | 104.96 | 69.77 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 306 | 65 | 19.89 | 38.04 | 39.35 | 82.70 | 58.17 |

| 5 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 307 | 55 | 16.89 | 46.04 | 51.35 | 105.60 | 59.34 |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 287 | 55 | 15.79 | 35.66 | 38.06 | 82.60 | 66.30 |

| 7 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 327 | 75 | 24.53 | 48.82 | 53.23 | 108.00 | 71.97 |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 340 | 75 | 25.50 | 36.85 | 40.49 | 90.20 | 61.65 |

| 9 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 314 | 55 | 17.27 | 32.10 | 35.09 | 95.10 | 54.40 |

| 10 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 316 | 55 | 17.38 | 40.52 | 38.63 | 85.50 | 71.48 |

| 11 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 348 | 75 | 26.10 | 41.44 | 42.63 | 71.90 | 64.31 |

| 12 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 348 | 75 | 26.10 | 43.84 | 44.72 | 102.50 | 58.05 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 339 | 65 | 22.04 | 43.41 | 48.49 | 103.30 | 68.80 |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 339 | 65 | 22.04 | 44.65 | 47.00 | 102.20 | 67.94 |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 338 | 65 | 21.97 | 42.28 | 49.35 | 102.04 | 64.92 |

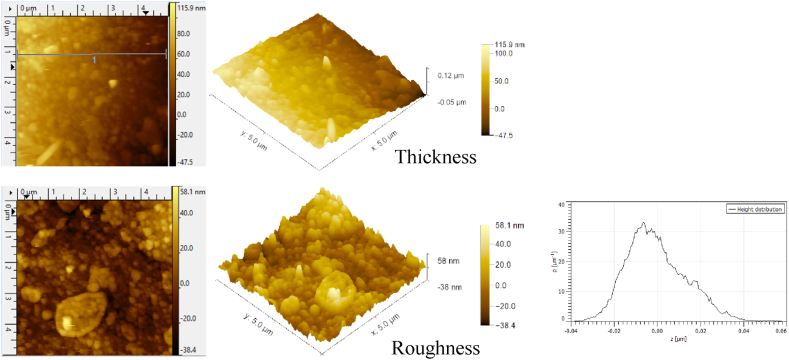

The thickness and roughness of the sputtered films were measured using AFM (Atomic Force Microscopy) equipment, specifically the XE70 model from Park System in South Korea. A visual representation of the AFM setup and measurement process is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

AFM images of thickness and roughness of sputtered films on PP substrate.

3.2. Optimization of the sputtered film thickness on glass slide and PP substrates

The results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) aimed at determining the statistical significance of the sputtered film's thickness on glass slide and PP substrates are presented in Table 3, Table 4, respectively. These tables offer insights into the linear, quadratic, and interaction effects of the parameters, shedding light on their significance in influencing the film thickness on each type of substrate.

Table 3.

Analysis of variance of thickness film sputtered by three target materials onto glass slide substrate.

| Source | DF | Adj. SS | Adj. MS | F-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 9 | 382.787 | 42.532 | 16.13 | 0.003 |

| Linear | 3 | 341.330 | 113.777 | 43.15 | 0.001 |

| speed (S) | 1 | 234.608 | 234.608 | 88.97 | 0.000 |

| TIME (T) | 1 | 72.100 | 72.100 | 27.34 | 0.003 |

| VOLTAGE (V) | 1 | 34.622 | 34.622 | 13.13 | 0.015 |

| Square | 3 | 29.615 | 9.872 | 3.74 | 0.095 |

| speed*speed | 1 | 0.124 | 0.124 | 0.05 | 0.837 |

| time*time | 1 | 24.032 | 24.032 | 9.11 | 0.029 |

| voltage*voltage | 1 | 7.426 | 7.426 | 2.82 | 0.154 |

| 2-Way Interaction | 3 | 11.841 | 3.947 | 1.50 | 0.323 |

| speed*time | 1 | 2.117 | 2.117 | 0.80 | 0.411 |

| speed*voltage | 1 | 0.634 | 0.634 | 0.24 | 0.645 |

| time*voltage | 1 | 9.091 | 9.091 | 3.45 | 0.122 |

| Source | DF | Adj. SS | Adj. MS | F-Value | P-Value |

| Error | 5 | 13.184 | 2.637 | ||

| Lack-of-Fit | 3 | 10.361 | 3.454 | 2.45 | 0.303 |

| Pure Error | 2 | 2.823 | 1.411 | ||

| Total | 14 | 395.971 | |||

| Model Summary | |||||

| S | R-sq. | R-sq. (adj.) | R-sq. (pred.) | ||

| 1.62384 | 96.67 % | 90.68 % | 56.53 % |

Table 4.

Analysis of variance of thickness film sputtered by three target materials onto PP substrate.

| Source | DF | Adj. SS | Adj. MS | F-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 9 | 1778.26 | 197.584 | 20.17 | 0.002 |

| Linear | 3 | 844.22 | 281.408 | 28.73 | 0.001 |

| speed (S) | 1 | 622.34 | 622.339 | 63.53 | 0.001 |

| time (T) | 1 | 220.08 | 220.080 | 22.47 | 0.005 |

| voltage (V) | 1 | 1.80 | 1.805 | 0.18 | 0.686 |

| Square | 3 | 468.80 | 156.267 | 15.95 | 0.005 |

| speed*speed | 1 | 34.05 | 34.048 | 3.48 | 0.121 |

| time*time | 1 | 437.61 | 437.611 | 44.67 | 0.001 |

| voltage*voltage | 1 | 30.55 | 30.555 | 3.12 | 0.138 |

| 2-Way Interaction | 3 | 465.23 | 155.078 | 15.83 | 0.006 |

| speed*time | 1 | 54.46 | 54.464 | 5.56 | 0.065 |

| speed*voltage | 1 | 6.76 | 6.760 | 0.69 | 0.444 |

| time*voltage | 1 | 404.01 | 404.010 | 41.24 | 0.001 |

| Error | 5 | 48.98 | 9.796 | ||

| Lack-of-Fit | 3 | 48.04 | 16.013 | 34.03 | 0.029 |

| Pure Error | 2 | 0.94 | 0.471 | ||

| Total | 14 | 1827.24 | |||

| Model Summary | |||||

| S | R-sq. | R-sq. (adj.) | R-sq. (pred.) | ||

| 3.12990 | 97.32 % | 92.49 % | 57.82 % |

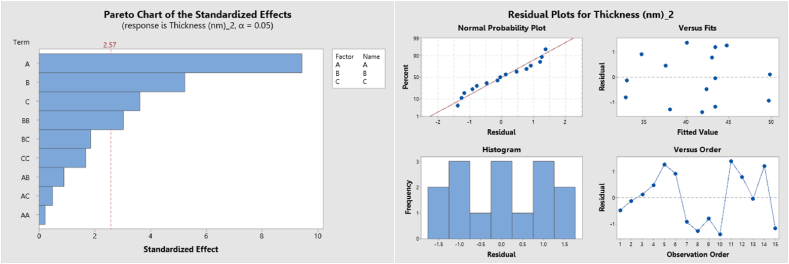

In Table 3, the P-values indicate statistical significance, with values less than 0.05. These P-values were used to assess the significance of each factor and the interactions between factors. Notably, the substrate rotation speed, sputtering time, sputtering voltage, and the coefficient of the quadratic sputtering time emerged as the most significant factors when it comes to determining the statistical significance of the sputtered film thickness on glass slide substrates. For further visual representation and understanding, you can refer to the Pareto chart in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Pareto chart and residual plots for the thickness of the sputtered film onto glass slide substrate.

The validity of the quadratic model for predicting the optimal thickness of the sputtered film on glass slide substrates was assessed by examining the linearity of fit through residual plots. In Fig. 3, the normal-probability plot reveals that the majority of data points cluster closely around the linear line. This clustering indicates that the error terms are approximately normally distributed. For evaluating the overall model fit, the coefficient of regression (R2) was calculated to be 96.67 %, indicating a high level of agreement between the quadratic model and the experimental data. Additionally, the adjusted R2, which accounts for the number of predictors in the model, was 90.68 %. This adjusted R2 value further underscores the satisfactory agreement of the quadratic models with the experimental data. To predict the optimal point, a second-order polynomial model was applied to establish the relationship between the independent variables. This relationship is expressed in Equation (1).

| Thickness = −136.5 + 0.042S–17.53T + 1.142V–0.00046S*S – 0.638T*T – 0.00227V*V - 0.0182S*T - 0.0008S*V - 0.0302 T*V | (1) |

In Table 4, the P-values indicate statistical significance, with values less than 0.05. These P-values were used to assess the significance of each factor and their interactions. It's noteworthy that the substrate rotation speed, sputtering time, coefficient of the quadratic sputtering time, and the interaction between time and voltage are identified as the most significant factors when determining the statistical significance of the sputtered film thickness on PP substrates. Additionally, the sputtering voltage itself is also deemed a significant factor. For a visual representation and a deeper understanding of these findings, please refer to the Pareto chart presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Pareto chart and residual plots for the thickness of the sputtered film onto PP substrate.

The validity of the quadratic model for predicting the optimal thickness of the sputtered film on PP substrates was confirmed by evaluating the linearity of residual plots. In Fig. 4, the normal-probability plot demonstrates that the majority of data points cluster closely around the linear line, indicating that the error terms follow a roughly normal distribution. Furthermore, the coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated to be 97.32 %, indicating a high level of agreement between the quadratic model and the experimental data. The adjusted R2, which adjusts for the number of predictors in the model, was found to be 92.49 %. This adjusted R2 value underscores the satisfactory agreement of the quadratic model with the experimental data. To predict the optimal point, the regression equation is expressed as Equation (2). This equation allows for the determination of the optimal parameters for achieving the desired thickness of the sputtered film on PP substrates.

| Thickness = 42.4 + 0.298S + 13.76T - 0.056V - 0.00759S*S - 2.722T*T - 0.00460V*V - 0.0922S*T + 0.00260S*V + 0.2010T*V | (2) |

In the multiple response prediction plots presented in Fig. 5, the analysis for the optimum thickness of the sputtered film, using three target materials on three magnetron guns and depositing onto a glass slide substrate, resulted in a maximum thickness of 50.2134 nm. At this point, the desirability (D) value reached 1. The optimal parameter settings for achieving this maximum thickness were 10 rpm (−1) for substrate rotation speed, 8.505 min (0.2727) for sputtering time, and 189.39 V (0.5556) for sputtering voltage. On the other hand, when the same three target materials were used on three magnetron guns for depositing onto a PP substrate, the analysis yielded a maximum thickness of 108.0968 nm. At this point, the desirability (D) value reached 0.9599. The optimal parameter settings for achieving this thickness were 10 rpm (−1) for substrate rotation speed, 9.798 min (0.8990) for sputtering time, and 176.768 V (0.0707) for sputtering voltage. These findings highlight the different optimal parameter settings required to achieve the desired thickness on glass slide substrates compared to PP substrates, as well as the variations in the resulting film thickness.

Fig. 5.

Multiple response prediction plots for maximum thickness and roughness films sputtered by three target materials onto different substrate materials.

3.3. Optimization of the sputtered film roughness on glass slide and PP substrates

The results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) aimed at determining the statistical significance of the sputtered film's roughness on glass slide and PP substrates are summarized in Table 5, Table 6, respectively. These tables provide insights into the linear, quadratic, and interaction effects of the parameters, helping to understand their significance in influencing the film's roughness on each type of substrate.

Table 5.

Analysis of variance of roughness film sputtered by three target materials onto glass slide substrate.

| Source | DF | Adj. SS | Adj. MS | F-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 9 | 500.046 | 55.561 | 16.74 | 0.003 |

| Linear | 3 | 373.113 | 124.371 | 37.47 | 0.001 |

| speed (S) | 1 | 303.838 | 303.838 | 91.53 | 0.000 |

| TIME (T) | 1 | 29.047 | 29.047 | 8.75 | 0.032 |

| VOLTAGE (V) | 1 | 40.227 | 40.227 | 12.12 | 0.018 |

| Square | 3 | 122.784 | 40.928 | 12.33 | 0.010 |

| speed*speed | 1 | 0.820 | 0.820 | 0.25 | 0.640 |

| time*time | 1 | 93.944 | 93.944 | 28.30 | 0.003 |

| voltage*voltage | 1 | 32.582 | 32.582 | 9.82 | 0.026 |

| 2-Way Interaction | 3 | 4.150 | 1.383 | 0.42 | 0.749 |

| speed*time | 1 | 3.553 | 3.553 | 1.07 | 0.348 |

| speed*voltage | 1 | 0.073 | 0.073 | 0.02 | 0.888 |

| time*voltage | 1 | 0.524 | 0.524 | 0.16 | 0.708 |

| Error | 5 | 16.598 | 3.320 | ||

| Lack-of-Fit | 3 | 13.774 | 4.591 | 3.25 | 0.244 |

| Pure Error | 2 | 2.823 | 1.412 | ||

| Total | 14 | 516.644 | |||

| Model Summary | |||||

| S | R-sq. | R-sq. (adj.) | R-sq. (pred.) | ||

| 1.82195 | 96.79 % | 91.00 % | 56.11 % |

Table 6.

Analysis of variance of roughness film sputtered by three target materials onto PP substrate.

| Source | DF | Adj. SS | Adj. MS | F-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 9 | 394.324 | 43.814 | 7.02 | 0.023 |

| Linear | 3 | 34.772 | 11.591 | 1.86 | 0.254 |

| speed (S) | 1 | 6.024 | 6.024 | 0.96 | 0.371 |

| time (T) | 1 | 26.263 | 26.263 | 4.21 | 0.096 |

| voltage (V) | 1 | 2.484 | 2.484 | 0.40 | 0.556 |

| Square | 3 | 52.380 | 17.460 | 2.80 | 0.148 |

| speed*speed | 1 | 1.849 | 1.849 | 0.30 | 0.610 |

| time*time | 1 | 44.322 | 44.322 | 7.10 | 0.045 |

| voltage*voltage | 1 | 10.668 | 10.668 | 1.71 | 0.248 |

| 2-Way Interaction | 3 | 307.173 | 102.391 | 16.40 | 0.005 |

| speed*time | 1 | 96.386 | 96.386 | 15.44 | 0.011 |

| speed*voltage | 1 | 74.605 | 74.605 | 11.95 | 0.018 |

| time*voltage | 1 | 136.182 | 136.182 | 21.81 | 0.005 |

| Error | 5 | 31.223 | 6.245 | ||

| Lack-of-Fit | 3 | 22.926 | 7.642 | 1.84 | 0.371 |

| Pure Error | 2 | 8.297 | 4.148 | ||

| Total | 14 | 425.547 | |||

| Model Summary | |||||

| S | R-sq. | R-sq. (adj.) | R-sq. (pred.) | ||

| 2.49891 | 92.66 % | 79.46 % | 9.41 % |

In Table 5, the P-values indicate statistical significance, with values less than 0.05. These P-values were utilized to assess the significance of each factor and their interactions. Notably, the substrate rotation speed, sputtering time, sputtering voltage, and the coefficient of the quadratic of time and voltage emerged as the most significant factors when determining the statistical significance of the sputtered film's roughness on glass slide substrates. For a visual representation and deeper understanding, you can refer to the Pareto chart presented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Pareto chart and residual plots for the roughness of the sputtered film onto glass slide substrate.

The validity of the quadratic model for predicting the optimal roughness of the sputtered film on glass slide substrates was confirmed by assessing the linearity of residual plots. As depicted in Fig. 5, the normal-probability plot illustrates that the majority of data points cluster closely around the linear line, indicating that the error terms are approximately normally distributed. Moreover, the coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated to be 96.79 %, signifying a high level of agreement between the quadratic model and the experimental data. The adjusted R2, which accounts for the number of predictors in the model, was determined to be 91.00 %. This adjusted R2 value reinforces the satisfactory agreement of the quadratic model with the experimental data. To predict the optimal point, the regression equation is expressed as Equation (3). This equation enables the determination of the optimal parameter settings for achieving the desired roughness of the sputtered film on glass slide substrates.

| Roughness = −205.4 - 0.238S + 23.10T + 1.803V + 0.00118S*S - 1.261T*T - 0.00475V*V - 0.0236S*T + 0.00027S*V - 0.0072 T*V | (3) |

In Table 6, the P-values indicate statistical significance, with values less than 0.05. These P-values were employed to assess the significance of each factor, and the Pareto chart in Fig. 7 visually represents these findings. The analysis reveals that, when determining the statistical significance of the roughness of the sputtered film on PP substrates, the coefficient of the quadratic sputtering time and the interactions between factors are the most significant factors. Specifically, three main factors stand out: substrate rotation speed, sputtering time, and sputtering voltage. These factors play a crucial role in influencing the roughness of the sputtered film on PP substrates.

Fig. 7.

Pareto chart and residual plots for the roughness of the sputtered film onto PP substrate.

The validity of the quadratic model for predicting the optimal roughness of the sputtered film on PP substrates was confirmed by assessing the linearity of residual plots. As depicted in Fig. 6, the normal-probability plot illustrates that most data points cluster closely around the linear line, indicating that the error terms are approximately normally distributed. Furthermore, the coefficient of determination (R^2) was calculated to be 92.66 %, indicating a substantial level of agreement between the quadratic model and the experimental data. The adjusted R^2, which considers the number of predictors in the model, was determined to be 79.46 %. While slightly lower than the R^2, this adjusted R^2 value still suggests a satisfactory agreement of the quadratic model with the experimental data. To predict the optimal point, the regression equation is expressed as Equation (4). This equation enables the determination of the optimal parameter settings for achieving the desired roughness of the sputtered film on PP substrates.

| Roughness = -321.1 + 2.556S + 38.87T + 2.167V- 0.00177S*S - 0.866T*T - 0.00272V*V - 0.1227S*T - 0.00864S*V - 0.1167T*V | (4) |

The multiple response prediction plots, as shown in Fig. 7, illustrate the analysis for the optimum roughness of the sputtered film using three target materials on three magnetron guns and depositing onto different substrates. For glass slide substrates, the analysis resulted in a maximum roughness of 55.5167 nm, with a desirability (D) value of 1. These optimal roughness conditions were achieved with the following parameter settings: 10 rpm (−1) for substrate rotation speed, 8.505 min (0.2727) for sputtering time, and 189.39 V (0.5556) for sputtering voltage. In contrast, when using the same three target materials on three magnetron guns and depositing onto PP substrates, the analysis yielded a maximum roughness of 70.5882 nm, with a desirability (D) value of 0.9599. The optimal roughness conditions for PP substrates were achieved with the following parameter settings: 10 rpm (−1) for substrate rotation speed, 9.798 min (0.8990) for sputtering time, and 176.768 V (0.0707) for sputtering voltage. These findings highlight the different optimal parameter settings required to achieve the desired roughness on glass slide substrates compared to PP substrates, as well as the variations in the resulting film roughness.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison between thin film properties on glass slide and PP substrates

The results of predicting the optimal conditions for maximizing the thickness of thin-film deposition revealed that the film sputtered onto a PP substrate achieved a thickness of 108.0968 nm. This is greater than the film thickness of 50.2134 nm obtained from films sputtered onto a glass slide substrate. Furthermore, the results for predicting the optimal conditions to maximize the roughness of thin-film deposition indicated that the film sputtered onto a PP substrate achieved a roughness of 70.5882 nm, which is greater than the film roughness of 55.5167 nm obtained from films sputtered onto a glass-slide substrate.

It's important to note that these results were obtained under the same substrate rotation speed of 10 rpm, with similar sputtering times but different sputtering voltages. This indicates that the choice of substrate material and its interaction with the sputtering process significantly impacts the resulting film thickness and roughness. In the surface morphology comparison, Fig. 8 presents SEM plane-view images of the Au-coated before sputtering and the target films sputtered onto glass slide (Fig. 8a and b) and PP substrates (Fig. 8c and d), respectively. The films deposited onto PP substrates exhibited grooves between the grains and some fractures on the surface, while these features were not observed in the films deposited on glass. These findings are consistent with previous research [26]that studied thin copper films deposited on a polymer surface and observed grooves between grains and surface fractures. These grooves can affect the accuracy of nanoscale film thickness and roughness measurements.

Fig. 8.

Surface morphology of nanostructured thin films measured by SEM. (a) Au-sputtered surface on glass slide; (b) three target materials-sputtered surface on glass slide; (c) Au-sputtered surface on PP substrate; (d) three target materials-sputtered surface on PP substrate.

The multiple response prediction plots for the maximum thickness and roughness of films sputtered using three target materials on glass slide and PP substrates demonstrate a consistent pattern. Specifically, reducing the substrate rotation speed leads to an increase in the thickness and roughness of the sputtered films on both substrates. This observation aligns with the findings [27] that reported a correlation between substrate rotation speed and film thickness. The study was noted that a lower speed of 1.5 rpm resulted in a film thickness of 12 nm, whereas a higher speed of 5 rpm led to a reduced thickness of only 3.2 nm. Regarding sputtering time and sputtering voltage, an increase in the values of these factors generally leads to an increase in the thickness and roughness of the sputtered films on both substrates. Conversely, when both sputtering time and sputtering voltage are increased, this results in a decrease in thickness and roughness. These trends are in line with the principles of plasma sputtering. Increased energy and longer sputtering times can lead to significant heating of the target material [28]. Additionally, when ions penetrate deeper into the solid target, the sputtering yield tends to decrease significantly [29]. These findings underscore the complex interplay of various factors in the sputtering process and how they influence film thickness and roughness on different substrates.

4.2. Structures and surface morphology

The surface morphology of the complex structured film deposited using the three target materials on a glass slide substrate (Fig. 9) and PP substrate (Fig. 10) was assessed using SEM-EDS analysis. In the plane-view images, a dense and granular structure was evident on the surface, with a distribution of Cu, Al, and Zn across the substrate. Notably, the film on the glass slide substrate exhibited a granular surface with larger grain sizes compared to the film on the PP substrate. Despite these differences, the measured roughness values were in the nanometer range for various film coatings, indicating a relatively smooth morphology. This observation aligns with the previous research [30].

Fig. 9.

SEM-EDS elemental maps of the sputtered film onto glass slide substrate.

Fig. 10.

SEM-EDS elemental maps of the sputtered film onto PP substrate.

However, it's important to note that the impurity of the multilayer film in this research was also evaluated using SEM-EDS analysis. Fig. 9, Fig. 10 revealed the presence of other elements aside from the multilayer film elements, constituting 71.47 wt% and 63.82 wt%, respectively. This contamination likely originated from the base pressure, as the 20 mTorr base pressure falls within the low vacuum range. While plasma sputtering can occur at this stage, it's possible for outgassing and other elements to remain in the chamber. Achieving a higher vacuum process can result in a purer film. Furthermore, heat treatment is a versatile technique that can influence various mechanical properties [31,32]. It offers control over factors such as uniformity, homogeneity, porosity, and crystalline structure, thereby enhancing the material's characteristics.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of variance results for film thickness and roughness, obtained through sputtering using three magnetron guns equipped with Cu, Al, and brass (Cu + Zn) targets and applied to both glass slide and PP substrates, highlighted the significance of certain factors in determining the optimal response. Specifically, substrate rotation speed, sputtering time, and sputtering voltage were found to be significant factors, as indicated by their P-values, all of which were less than 0.05 (α = 0.05). Interestingly, the optimal conditions for maximizing film thickness and roughness on PP substrates were found to be higher than those obtained for films deposited on glass slide substrates. The structural characterization of the films and chemical compositions were analyzed through SEM-EDS, which revealed the presence of the three materials (Cu, Al, and Zn) evenly distributed over the substrate surface. These results collectively demonstrate the effectiveness of an angular DC magnetron co-sputtering system with a rotated substrate in preparing multilayer films with complex structures, especially on plastic parts. This technology holds promising applications in the plastic industry, particularly in the automotive sector. This experimental study provides valuable insights for fabricating multilayer thin films and designing their thickness and roughness. Furthermore, it offers the potential for controlling the properties of parts based on predictive equations, contributing to advancements in materials science and industrial processes.

Ethics declarations

All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Preecha Changyom: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Komgrit Leksakul: Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Conceptualization. Dheerawan Boonyawan: Validation, Supervision, Resources. Pongsawat Premphet: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation. Norrapon Vichiansan: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Chiang Mai University, Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI), National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) (NRIIS Project Number 4708696).

References

- 1.Kelly P.J., Arnell R.D. Magnetron sputtering: a review of recent developments and applications. Vacuum. 2000;56:159–172. doi: 10.1016/S0042-207X(99)00189-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gudmundsson J.T. Physics and technology of magnetron sputtering discharges. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2020;29 doi: 10.1088/1361-6595/abb7bd. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruchhaus R., Pitzer D., Primig R., Wersing W., Xu Y. Deposition of self-polarized PZT films by planar multi-target sputtering, Integr. Ferroelectrics. 1997;14:141–149. doi: 10.1080/10584589708019986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dzhumaliev A.S., Nikulin Y.V., Filimonov Yu A. Surface roughness and magnetic properties of Co/SiO2/Si(100) polycrystalline films deposited via DC magnetron sputtering. J. Commun. Technol. EL.+. 2009;54:331–335. doi: 10.1134/S1064226909030115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mo K.X., Chen D.H., He Z.H., Chen M. Structure and magnetic properties of Fe films with pyramid-like nanostructures deposited by oblique target direct current magnetron sputtering. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2013;24:4068–4074. doi: 10.1007/s10854-013-1362-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhivya P., Prasad A.K., Sridharan M. Nanostructured perovskite CdTiO3 films for methane sensing. Sensor. Actuator. B. 2016;222:987–993. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2015.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang L.C., Chang C.Y., You Y.W. Ta–Zr–N thin films fabricated through HIPIMS/RFMS co-sputtering. Coatings. 2017;7:189. doi: 10.3390/coatings7110189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adamiak B., Dora J., Kaczmarek D., Domaradzki J., Wojcieszak D., Mazur M. IEEE; Wernigerode, Germany: 2009. Magnetron Sputtering System with Multi-Targets for Multilayers Deposition, Proc; pp. 7–9. 25-27 June 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godinho V., et al. On the formation of the porous structure in nanostructured a-Si coatings deposited by dc magnetron sputtering at oblique angles. Nanotechnology. 2014;25 doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/25/35/355705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joung Y.H., Kang H.I., Kim J.H., Lee H.S., Lee J., Choi W.S. SiC formation for a solar cell passivation layer using an RF magnetron co-sputtering system. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2012;7:22. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-7-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai X.M., et al. The n-type conduction of indium-doped Cu2O thin films fabricated by direct current magnetron co-sputtering. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015;107 doi: 10.1063/1.4928527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammadi O.A., Naji N.E. Characterization of polycrystalline nickel cobaltite nanostructures prepared by DC plasma magnetron co-sputtering for gas sensing applications. Photonic Sens. 2018;8:43–47. doi: 10.1007/s13320-017-0460-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valluzzi M.G., Valluzzi L.G., Meyer M., Hernández-Fenollosa M.A., Damonte L.C. Optical and electrical properties of TiO2/Co/TiO2 multilayer films grown by DC magnetron sputtering. Adv. Condens. Matter Phys. 2018;2018:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2018/1257543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia Gonzalez L., Hernandez Torres J., Romo Ma G.G., et al. Ti/TiSiNO multilayers fabricated by co-sputtering. JMEPEG. 2013;22:2377–2381. doi: 10.1007/s11665-013-0523-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchette F., Billard A. Special issue “magnetron sputtering deposited thin films and its applications”. Coatings. 2020;10:1072. doi: 10.3390/coatings10111072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu C.M., Tzou W.C., Yang C.F., Liou Y.J. Investigation of the high mobility IGZO thin films by using co-sputtering method. Materials. 2015;8:2769–2781. doi: 10.3390/ma8052769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang H.W., Huang P.K., Davison A., Yeh J.W., Tsau C.H., Yang C.C. Nitride films deposited from an equimolar Al–Cr–Mo–Si–Ti alloy target by reactive direct current magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Films. 2008;516:6402–6408. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2008.01.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinhoff M.K., et al. Ag surface and bulk segregations in sputtered ZrCuAlNi metallic glass thin films. Materials. 2022;15:1635. doi: 10.3390/ma15051635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayaraman V.K., Kuwabara Y.M., Álvarez A.M., Amador MdllO. Importance of substrate rotation speed on the growth of homogeneous ZnO thin films by reactive sputtering. Mater. Lett. 2016;169:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2016.01.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szeteiová K. Automotive materials plastics in automotive markets today. Mater. Sci. 2010:27–33. api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:15991796. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michael F., et al. Proceedings of 20th International Technical Conference on Ther. Enhanced Safety of Vehicles (ESV); Lyon, France: 2007. Enhancing future automotive safety with plastics.https://www-esv.nhtsa.dot.gov/Proceedings/20/07-0451-W.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strumberger N., Gospocic A., Hvu M., Bartulic C. Polymeric materials in automobiles. Promet Traffic Traffico. 2005;17:149–160. doi: 10.7307/ptt.v17i3.630. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Standox GmbH, How to refinish plastics; Standox GmbH, p. 11152147 GB 1007 2750. https://stage.standox.com/content/dam/standox-shared/Standothek/THK_PlasticPaint_GB.pdf.

- 24.Changyom P., Leksakul K., Boonyawan D., Dechthummarong C. Design and manufacturing of angular DC magnetron co- sputtering system to provide multilayer films. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2022;49:446–455. doi: 10.12982/CMJS.2022.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Changyom P., Leksakul K., Charoenchai N., Boonyawan D. Designed and produced the rotary substrate holder and its optimized in angular DC magnetron co-sputtering system. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2022;49:1–11. doi: 10.12982/CMJS.2022.106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyagi V., Ranjan M., Rane R., Vaghela N., Barhai P.K., Acharya V., Mukherjee S. Deposition and characterization of copper thin films on a polymer surface by using a dc cylindrical magnetron sputtering technique. Phys. Status Solidi. 2008;5:960–963. doi: 10.1002/pssc.200778326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang J.F., Huang C.H., Lin C.Y., Yang F.C., Chang C.L. Effects of substrate rotation speed on structure and adhesion properties of CrN/CrAlSiN multilayer coatings prepared using high-power impulse magnetron sputtering. Coatings. 2020;10:742. doi: 10.3390/coatings10080742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waite M.M., Shah S.I., Glocker D.A. vol. 15. SVC Bulletin; Albuquerque, NM, USA: 2010. pp. 42–50.https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=UhdVlkQAAAAJ&citation_for_view=UhdVlkQAAAAJ:hqOjcs7Dif8C (Sputtering Sources). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammadi O. 2015. Fundamentals of Plasma Sputtering. research-gate.net/publication/283490139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y.I., Liu K.T., Wu F.B., Duh J.G. Mo–Ru coatings on tungsten carbide by direct current magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Films. 2006;515:2207–2212. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2006.03.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medeiros E., Brandes R., Al-Qureshi H.A., Recouvreux D. Surface energy modification for coating adhesion improvement on polypropylene. Int. J. Surf. Sci. Eng. 2018;12:277–292. doi: 10.1504/IJSURFSE.2018.096139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balciunaite E., Petrasauskiene N., Alaburdaite R., Jakubauskas G., Paluckiene E. Formation and properties of mixed copper sulfide (CuxS) layers on polypropylene. Surface. Interfac. 2020;21 doi: 10.1016/j.surfin.2020.100801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.