Abstract

Tourette Syndrome (TS) is a disorder in which the patient has a history of multiple motor and vocal tics. Depression and anxiety are common in these patients. The results of the studies show different prevalence of these disorders in patients with TS. So, the objective of the present study was to liken the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS by systematic review and meta-analysis. The present study was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines during 1997–2022. The articles were obtained from Scopus, Embase, PubMed, Web of Science (WoS) and Google Scholar databases. I2 was used to investigate heterogeneity between studies. Data were analyzed by comprehensive meta-analysis software (Version 2). Finally, 12 articles with a sample size of n = 3812 were included in the study. As a result of combining the results of the studies, the total estimate of the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS was 36.4% (95% confidence interval: 21.1–54.9%) and 53.5% (95% confidence interval: 39.9–66.6%), respectively. The results of meta-regression showed that by increasing mean age (9–31.5 years), the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS increased significantly (P<0.001). The results of the present study showed that the prevalence of depression and anxiety was high in patients with TS. Therefore, it is suggested that health officials and policy makers design measures to prevent and control these disorders.

Keywords: Prevalence, Depression, Anxiety, Tourette syndrome, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Disorders of early life remaining throughout life are called neurodevelopmental disorders [1]. These disorders usually appear early in a child's development, often before they reach school age. Defects associated with these disorders include personal, social, educational, or occupational dysfunction. These disorders may show significant changes over time [1, 2]. Childhood and adolescence disorders can delay and / or even hinder children’s social development [3].

Tic disorders are a group of neurodevelopmental disorders that commonly begin in childhood and adolescence and may be constant or alternatively severe over time [1, 3]. Tics are repetitive, involuntary, inharmonic and sudden movements or sounds that can involve distinct muscle groups and often appear between the ages of 4 and 6. These disorders are divided into TS, chronic motor or vocal tics, and transient tics [4]. The prevalence of tic disorders is higher in children than adults. Thus, about 5–30 out of ten thousand children and only 1–2 out of ten thousand adults have this disorder [5].

Diagnostic criteria for Tourette syndrome based on DSM-5 include (1) multiple motor tics and one or more vocal tics sometimes present during the disease (though not necessarily simultaneously), (2) the frequency of tics may increase and reduce, but continue for more than a year since the beginning of the first tick, (3) before 18 years old, (4) this disorder is not caused by the effects of drugs (such as cocaine) or other physical diseases such as Huntington's disease, inflammation of the brain after the virus, and etc. [4]. The meta-analysis of TS in China reported the prevalence in children as 1.7% [6], 0.52% in USA [7] and 0.11% in Polish in adults [8]. The prevalence of TS in boys is 3 times higher than in girls [5].

Anxiety and depression are among the most important issues studied by psychologists, psychiatrists and behavioural scientists around the world [9]. Among physical and mental diseases, depression is the number one problem in the world. Depression is one of the most important mood disorders that is associated with low mood, loss of interest, guilt and worthlessness, sleep and appetite disorders, reduced energy and poor concentration. Depression and anxiety are the most common psychiatric disorders with a prevalence of 10–20% in the general population [10]. Approximately 15% of the total population experience a period of major depression at some point in their lives [11]. Anxiety is an unpleasant and unknown state that affects a person and is accompanied by symptoms such as fatigue, restless and heartbeat. The genetic, hereditary, environmental, psychological, social and biological factors are involved in the etiology of anxiety [12]. A person who is constantly exposed to anxiety loses his self-confidence and feels depressed while feeling humiliated, which in turn will fuel the vicious cycle of job stress and efficiency. Continuation of this cycle can gradually erode the mental and physical abilities of individuals and after a while lead to unstable nervous disorders [13].

Several preliminary studies have been conducted on the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS in different parts of the world, but these studies have investigated the prevalence in a small environment with a smaller sample size. The results of studies showed different prevalence of these disorders in different populations. Also, none of these studies have investigated the effect of potential factors such as age and prevalence over time. So, the objective of the present study was to standardize the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS by systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

The present systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to PRISMA 2020 guidelines [14] during 1997–2022. The articles entered the meta-analysis were obtained from Scopus, Embase, PubMed, Web of Science (WoS) and Google Scholar databases. Keywords used in the search included "Prevalence", "Epidemiology", "Prevalent*", "Tourette syndrome", "Depression", "Depressive "Disorder", "Depress*", "Anxiety*", and "Anxieties" and in combination using (or) and (and) operators. Keywords were validated using MeSh for PubMed and Emtree for Embase. The study search did not consider any time or language restrictions to retrieve all possible related articles by January 2022. Finally, Google Scholar and the references of all articles entered the meta-analysis were manually searched. For example, PubMed search strategy was defined as follows:

(((((((((Epidemiology[MeSH Terms]) OR (Prevalence[MeSH Terms])) OR (Epidemiology[Title/Abstract])) OR (Prevalance[Title/Abstract])) OR (Prevalence[Title/Abstract])) OR (Prevalent*[Title/Abstract])) OR ("Prevalences"[Title/Abstract])) OR ("Prevalence s"[Title/Abstract])) AND ((("Tourette's syndrome"[Title/Abstract]) OR ("Tourette syndrome"[Title/Abstract])) OR ("Tourette syndrome"[MeSH Terms]))) AND ((((Depression[MeSH Terms]) OR ("Depressive Disorder"[MeSH Terms])) OR (Depress*[Title/Abstract])) OR (((Anxiety[MeSH Terms]) OR (Anxiety*[Title/Abstract])) OR (Anxieties[Title/Abstract]))).

In order to reduce publication bias and error, all stages of searching in different databases, review, selection, data extraction and quality evaluation of articles were performed by two researchers, and in case of disagreement, first with discussion, then review and finally according to the opinion of the third person, an agreement was reached.

Inclusion criteria

Original Research Articles

Observational articles (cross-sectional study, case study and cohort study)

Access to the full text of the article

Studies that reported the percentage or frequency of prevalence of depression or anxiety in patients with TS.

Exclusion criteria

Studies unrelated to the objective of the study

Interventional studies (clinical trial study, field trial study and social trial study), qualitative studies, case series, case reports, letter to editor, articles presented at conferences, reviews, systematic review and meta-analysis, dissertations and animal studies

The full text of the article is not available

Repeated and overlapping studies in different databases

Selection process of studies

After determining the search strategy for each database, all articles obtained from different databases were entered EndNote X8 software. First, all repeated and overlapping studies in different databases were excluded. The names of the authors, institutes and journals of all studies were then excluded. At the next stage, the title and abstract of the studies were reviewed and unrelated studies were excluded. Then, full text of the remaining articles were thoroughly reviewed according to inclusion and exclusion criteria and irrelevant studies were excluded. Finally, articles that met all inclusion criteria entered the qualitative evaluation.

Qualitative evaluation of studies

Qualitative evaluation of studies was performed using Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist, which is a standard and well-known checklist for qualitative evaluation of prevalence studies [15]. This checklist has 9 different questions about: (1) sample frame, (2) participants, (3) sample size, (4) study subject and setting described in detail), (5) data analysis, (6) valid methods for identifying conditions, (7) measure the situation, (8) statistical analysis and (9) adequate response rate. For scoring, "Yes" was awarded if mentioned, "No" was awarded if not mentioned, and "NA" was awarded if not reported. The minimum and maximum scores based on the number of "Yes" were 0 and 9, respectively. The results of qualitative evaluation of studies based on JBI checklist items are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Qualitative evaluation of studies based on JBI checklist items

| First author, year (reference) | Sample frame | Participants | Sample size | Study subjects | Data analysis | Methods | Measure the situation | Statistical analysis | Response rate adequate | Quality score (Number “Yes”) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSc, 1998 [16] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | NA | NA | Yes | No | 5 |

| Robertson, 2006 [17] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | NA | NA | Yes | No | 5 |

| Berthier, 1998 [18] | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 6 |

| Robertson, 1997 [19] | No | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| Gharatya, 2014 [20] | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 6 |

| Whitney, 2019 [21] | No | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | No | 5 |

| Robertson, 2015 [22] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 7 |

| Rizzo, 2017 [23] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Robertson, 2002 [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | NA | NA | Yes | No | 5 |

| Baglioni, 2014 [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | NA | NA | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Solís-García, 2021 [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Wodrich, 1997 [27] | No | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 6 |

Data extraction

Data were extracted using a pre-prepared checklist. The various items on this checklist included name of the corresponding author, year of publication of the article, sample size (total, male and female), country, diagnostic tools for depression and anxiety, prevalence, age of patients and population studied.

Statistical analysis

The index studied in this study was the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS, which was used to combine the results of different studies on the frequency in each study. Heterogeneity between studies was investigated by I2 and due to the high heterogeneity between the results of studies included in the meta-analysis (I2˃ 75%), the random effects model was used. Funnel Plot and Egger’s regression intercept were used to investigate publication bias. Meta-regression was also used to investigate the relationship between the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS with sample size, year of publication and mean age of patients. Subgroup analysis was performed according to the study population. Data analysis was performed by Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (Version 2) and P value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Stages of articles entry in meta-analysis

A total of 496 studies were found in the initial search using the search strategies identified for the various databases. 2 studies were added through manual search. 224 studies were repeated in different databases and excluded. 274 studies were reviewed by title and abstract, of which 239 studies were excluded due to irrelevance. Full-text of remaining 35 studies was reviewed, of which 23 studies were excluded due to not meeting all inclusion criteria. Finally, the remaining 12 articles entered the qualitative evaluation and none of the studies based on JBI checklist were of poor quality. The stages of PRISMA 2020 flow chart are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for article selection

General information of the articles

The total sample size of the studies was n = 3812. The highest and lowest sample sizes were related to the 2019 study in the USA [21] with n = 1428 and the 2021 study in Spain [26] with n = 22, respectively. Two-thirds of the studies have been conducted on children or adolescents. The oldest and newest studies were in 1997 and 2021, respectively. 50% of the studies have been conducted in the UK. Also, the studied studies reported the prevalence of depression between 8.7% and 73% and the prevalence of anxiety between 31.4% and 80%. The data of the articles entered systematic review and meta-analysis are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Specifications and data of articles entered for systematic review and meta-analysis

| First author, year, (reference) | Country | Sample size (n) | Age (year) | Diagnostic tool | Prevalence (%) | Population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | Depression | Anxiety | Depression | Anxiety | ||||

| BSc, 1998 [16] | UK | 30 | 17 | 13 | 9.0 | BCDI | - | 29.0 | - | Children |

| Robertson, 2006 [17] | UK | 918 | - | - | 9.0 | DSM-IV-TR | - | 13.0 | - | Children |

| Berthier, 1998 [18] | Spain | 30 | 13 | 17 | 31.5 ± 11.0 | HDRS | TBSA | 53.0 | 73.0 | Adult |

| Robertson, 1997 [19] | UK | 39 | 31 | 8 | 26.2 (11–55) | BDI | Spielberger | 12.3 | 44.6 | Adult |

| Gharatya, 2014 [20] | UK | 524 | - | - | 26.9 | BDI | Spielberger | 75.0 | 80.0 | Adult |

| Whitney, 2019 [21] | USA | 1428 | - | - | 11.5 | BDI | Spielberger | 15.3 | 37.9 | Children and Adolescents |

| Robertson, 2015 [22] | UK | 578 | 422 | 156 | 25.4 ± 14.3 | DSM | DSM | 49.0 | 43.0 | Adult |

| Rizzo, 2017 [23] | Italy | 98 | 81 | 17 | 12.2 ± 0.7 | CDI | MASC | 66.7 | 44.8 | Children and Adolescents |

| Robertson, 2002 [24] | UK | 57 | 45 | 12 | 10.7 ± 3.0 | DSM-III-R | - | 8.7 | - | Children and Adolescents |

| Baglioni, 2014 [25] | Italy | 55 | 40 | 15 | 17.6 | DSM-IV-TR | DSM-IV-TR | 27.44 | 31.4 | Children and Adolescents |

| Solís-García, 2021 [26] | Spain | 22 | 19 | 3 | 11.0 | DSM-5 | DSM-5 | 50.0 | 72.7 | Children and Adolescents |

| Wodrich, 1997 [27] | USA | 33 | 25 | 8 | 9.4 ± 2.3 | DSM-III-R | DSM-III-R | 73.0 | 55.0 | Children and Adolescents |

Meta-analysis of the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS

The results of I2 test for the global prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS indicated a significant heterogeneity between studies (depression = 98.63 and anxiety = 96.91). So, random effect model was used for data analysis (Table 3). According to funnel plot (Figs. 2 and 3) and the results of Egger’s regression intercept, there was no publication bias among the studies at the level of 0.1 (depression = 0.685 and anxiety = 0.410). As a result of combining the results of all studies, the prevalence of depression in patients with TS; 36.4% (95% confidence interval: 21.1–54.9%) and prevalence of anxiety in patients with TS; 53.5% (95% confidence interval: 39.9–66.6%) was estimated by random effect model (Figs. 4 and 5) (black square percentage and the length of the line on which the 95% confidence interval is located in each study, the rhomb represents the total estimate of the prevalence). The results of sensitivity analysis showed that by excluding each of the studies, the final estimate of the prevalence percentage does not change significantly (Figs. 6 and 7).

Table 3.

Report the results of fixed and random effects model on meta-analysis

| Disorder | Model | Number studies | Point estimate | Lower limit | Upper limit | Z-value | P-value | Q-value | df (Q) | P-value | I2 | Tau squared | Standard error | Variance | Tau |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Fixed | 12 | 0.330 | 0.312 | 0.348 | -17.36 | 0.000 | 808.173 | 11 | 0.000 | 98.639 | 1.692 | 1.189 | 1.414 | 1.301 |

| Random | 12 | 0.364 | 0.211 | 0.549 | -1.44 | 0.148 | |||||||||

| Anxiety | Fixed | 9 | 0.462 | 0.442 | 0.481 | -3.821 | 0.000 | 259.627 | 8 | 0.000 | 96.919 | 0.629 | 0.547 | 0.299 | 0.793 |

| Random | 9 | 0.535 | 0.399 | 0.666 | 0.504 | 0.615 |

Fig. 2.

Results of funnel plot for estimating the total prevalence of depression

Fig. 3.

Results of funnel plot for estimating the total prevalence of anxiety

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for estimating the total prevalence of depression

Fig. 5.

Forest plot for estimating the total prevalence of anxiety

Fig. 6.

Sensitivity analysis for estimating the total prevalence of depression

Fig. 7.

Sensitivity analysis chart for estimating the total prevalence of anxiety

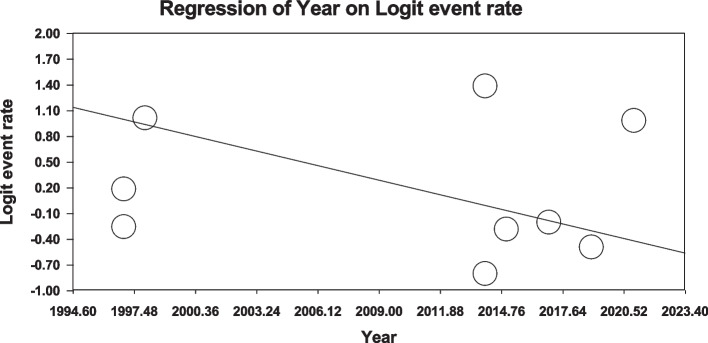

Meta-regression of prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS

Using meta-regression, the relationship between potential factors such as sample size (Figs. 8 and 9), year of study (Figs. 10 and 11) and mean age of patients (Figs. 12 and 13) and the total estimate of the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS was investigated. The results showed that by increasing sample size, the prevalence of depression (Fig. 8) and anxiety (Fig. 9) reduced significantly (P<0.001). By increasing year of study, the prevalence of anxiety (Fig. 11) reduced significantly (P<0.001), but the relationship between year of study and prevalence of depression (Fig. 10) was not significant (P˃0.05). By increasing mean age (9–31.5 years) of patients, the prevalence of depression (Fig. 12) and anxiety (Fig. 13) increased significantly (P<0.001).

Fig. 8.

Meta-regression of the relationship between sample size and prevalence depression

Fig. 9.

Meta-regression of the relationship between sample size and prevalence anxiety

Fig. 10.

Meta-regression between years of study and prevalence depression

Fig. 11.

Meta-regression between years of study and prevalence anxiety

Fig. 12.

Meta-regression between the mean age of patients and prevalence depression

Fig. 13.

Meta-regression of the relationship between the mean age of patients and prevalence anxiety

Subgroup analysis

Due to the high heterogeneity among the studies, subgroup analysis by population was reported in Table 4. The highest prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS in the adult population was estimated to be 47.9% (95% confidence interval: 27.6–68.9%) and 61.3% (95% confidence interval: 34.7–82.5%), respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of depression and anxiety

| Subgroups | Number studies | Point estimate | Lower limit | Upper limit | Z-value | P-value | P-value between | I2 | Standard error | Variance | Tau | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Adult | 4 | 0.479 | 0.276 | 0.689 | -0.186 | 0.852 | 0.141 | 96.99 | 0.907 | 0.823 | 0.849 |

| Children | 2 | 0.191 | 0.078 | 0.397 | -2.761 | 0.006 | 84.92 | 0.790 | 0.624 | 0.689 | ||

| Children and Adolescents | 6 | 0.363 | 0.156 | 0.639 | -0.971 | 0.331 | 96.98 | 1.728 | 2.988 | 1.373 | ||

| Anxiety | Adult | 4 | 0.613 | 0.347 | 0.825 | 0.824 | 0.410 | 0.260 | 98.03 | 1.171 | 1.401 | 1.082 |

| Children and Adolescents | 5 | 0.448 | 0.353 | 0.547 | -1.030 | 0.303 | 74.67 | 0.133 | 0.154 | 0.364 | ||

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis was performed to determine the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS. Finally, after combining the data obtained from 12 articles entered the meta-analysis, the prevalence of depression and anxiety was 36.4% and 53.5% in these patients, respectively. The highest prevalence of depression and anxiety was reported by Gharatya et al. (75% and 80%, respectively) [20]. The lowest prevalence of depression was reported by Robertson et al. (8.7%) [24] and the lowest prevalence of anxiety was reported by Baglioni et al. (31.4%) [25]. The highest quality assessment score [8] based on JBI checklist was related to a 2017 study in Italy [23], which reported a 66.7% prevalence of depression and a 44.8% prevalence of anxiety in patients with TS.

To the best of our knowledge, no systematic review or meta-analysis has been performed to estimate the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS. According to a meta-analysis by Kisely et al., the prevalence of depression and anxiety was 12.5% and 3.4% in the general population, respectively [28]. Also, Salari et al. reported the prevalence of anxiety and depression 29.6% and 33.7% in the general population during Covid-19 pandemic, respectively [29]. Comparison of the results of the above meta-analyzes with the present study showed that the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS was higher than the general population, which requires special attention of health officials and policy makers.

There is evidence of dopamine involvement in tic disorders, based on the fact that dopamine antagonist drugs such as haloperidol suppress tics and factors that increase central dopaminergic activity, such as Ritalin, exacerbate tics. The relationship between tics and dopamine is not a simple one and has not yet been fully known [30]. There is also evidence of dysfunction of the cerebral cortex circuits involved in motor functions. Studies using magnetic resonance imaging have shown natural asymmetry of the tail nuclei in those with these disorders [31]. Environmental and social factors also play a role in the development of this syndrome, such as smoking and high levels of stress during pregnancy, prematurity and low birth weight, psychiatric disorders, streptococcal infections and other psychological stresses. Therefore, therapeutic approaches to tic disorders can be divided into three main groups: medication, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and behavioral therapy [32].

The onset of Tourette syndrome is usually between 4 and 6 years old. The highest severity occurs between the ages of 10 and 12. So that in adolescence its intensity reduces. Many adults with Tourette syndrome experience reduced symptoms [4]. However, the results of subgroup analysis of the present study showed that the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS in the adult population was higher than other populations studied. Also, the results of meta-regression showed that by increasing mean age (9–31.5 years), the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS increased significantly. The reasons for the higher prevalence of depression and anxiety with age can be the influence of social environment, university and work, pubertal stress, substance abuse, negative thinking patterns, differences in the brain (adolescents' brain is structurally different from adults' brain), changes in the brain circuits of adolescents play a role in the risk-reward response, and increase stress levels. The adolescents with anxiety and depression have different neurotransmitters, including dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine in their brains affecting mood and behavior) and etc.

The high prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS in different populations, especially in young people, indicates the need for investigation and follow-up for these disorders in these patients. Due to the complications and problems that depression and anxiety cause in these patients and its significant effect on various aspects of life, there is a need for special attention by the authorities. In order to reduce the prevalence of depression and anxiety, one should become aware of this issue, find the appropriate solution, implement these solutions, and follow up the results of the actions. This policy is effective when implemented at the individual, group and organizational levels.

Due to the small number of studies included in the meta-analysis in the systematic review and meta-analysis of the present study and most of the articles were presented in continental Europe, it was not possible to analyze subgroups according to the continent and social environment studied. Due to the influence of culture and social environment on the prevalence of depression and anxiety, it is suggested to conduct further studies with larger sample sizes in different parts of the world, continents and cultures to determine the prevalence of these disorders more accurately in different populations and cultures.

High heterogeneity between studies (90%>) led to perform a subgroup analysis according to the study population, which reduced a small amount of heterogeneity between studies, but still heterogeneity in all subgroups is high, which may be due to demographic information, sample size and study methodology. Other limitations included the lack of uniform reporting of articles, the same method, the random selection of some samples, the small sample size of some articles, the small number of studies in some subgroups for subgroup analysis and the lack of access to the full text of articles presented at the conference.

Conclusion

The results of the present systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with TS was high. Therefore, it is suggested that health officials and policy makers design measures to prevent and control these disorders.

Acknowledgements

This study is the result of research project No. 50001018 approved by the Student Research Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. We would like to thank the esteemed officials of that center for accepting the financial expenses of this study.

Abbreviations

- TS

Tourette Syndrome

- WoS

Web of Science

- MeSH

Medical Subject Headings

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- BCDI

Birleson Child Ikpression Invcntory

- HDRS

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

- TBSA

Tyrer’s Brief Scale for Anxiety

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory

- CDI

Child Depression Inventory

- MASC

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Authors’ contributions

M.K. and P.A. contributed to the design, M.K. and S.T. participated in most of the study steps. M.K. and P.A. prepared the manuscript. P.A. and M.K. assisted in designing the study, and helped in the, interpretation of the study. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Funding

By Deputy for Research and Technology, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (IR) (50001018). This deputy has no role in the study process.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets are available through the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent to participate Ethics approval was received from the ethics committee of deputy of research and technology, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (IR.KUMS.REC.1400.790). All the methods of the present study have been carried out in accordance with the ethical standards set out in the Helsinki Declaration. This study did not include human samples and did not require informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Thapar A, Cooper M, Rutter M. Neurodevelopmental disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(4):339–46. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30376-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thapar A, Rutter M. Neurodevelopmental disorders. Rutters Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;1:31–40. doi: 10.1002/9781118381953.ch3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, Marceau K. Disorders of childhood and adolescence: gender and psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:275–303. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edition F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Am Psychiatric Assoc. 2013;21:591–643. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knight T, Steeves T, Day L, Lowerison M, Jette N, Pringsheim T. Prevalence of tic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Neurol. 2012;47(2):77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang C, Zhang L, Zhu P, Zhu C, Guo Q. The prevalence of tic disorders for children in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2016;95(30):e4354. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scharf JM, Miller LL, Gauvin CA, Alabiso J, Mathews CA, Ben-Shlomo Y. Population prevalence of Tourette syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2015;30(2):221–228. doi: 10.1002/mds.26089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine JL, Szejko N, Bloch MH. Meta-analysis: adulthood prevalence of Tourette syndrome. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;95:109675. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, Yang N. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e923549–e923551. doi: 10.12659/MSM.923549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chew NW, Lee GK, Tan BY, Jing M, Goh Y, Ngiam NJ, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C, Yang L, Liu S, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, et al. Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:306. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahnaz A, Meinour L, Soghrat F, Mariam N. The effect of counseling on anxiety after traumatic childbirth in nulliparous women; a single blind randomized clinical trial. 2010.

- 13.Liu C-Y, Yang Y-Z, Zhang X-M, Xu X, Dou Q-L, Zhang W-W, et al. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:98. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–153. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mason A, Banerjee S, Eapen V, Zeitlin H, Robertson MM, et al. The prevalence of Tourette syndrome in a mainstream school population. Devel Med Child Neurol. 1998;40(5):292–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1998.tb15379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robertson MM. Mood disorders and Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome: an update on prevalence, etiology, comorbidity, clinical associations, and implications. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(3):349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berthier ML, Kulisevsky J, Campos VM. Bipolar disorder in adult patients with Tourette’s syndrome: a clinical study. Biol Psychiat. 1998;43(5):364–370. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson MM, Banerjee S, Fox-Hiley PJ, Tannock C. Personality disorder and psychopathology in Tourette’s syndrome: a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171(3):283–286. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gharatya A, Stern J, Man C, Williams D, Simmons H, Robertson M. Suicidality in patients with tourette's syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(8):e3–e. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308883.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitney DG, Shapiro DN, Warschausky SA, Hurvitz EA, Peterson MD. The contribution of neurologic disorders to the national prevalence of depression and anxiety problems among children and adolescents. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;29:81–4. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertson MM, Cavanna AE, Eapen V. Gilles de la Tourette syndrome and disruptive behavior disorders: prevalence, associations, and explanation of the relationships. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;27(1):33–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13050112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rizzo R, Gulisano M, Martino D, Robertson MM. Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, depression, depressive illness, and correlates in a child and adolescent population. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(3):243–249. doi: 10.1089/cap.2016.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson MM, Banerjee S, Eapen V, Fox-Hiley P. Obsessive compulsive behaviour and depressive symptoms in young people with Tourette syndrome. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;11(6):261–265. doi: 10.1007/s00787-002-0301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baglioni V, Stornelli M, Molica G, Chiarotti F, Cardona F. Prevalence of anxiety disturbs in patients with Tourette syndrome and tic disturb. Riv Psichiatr. 2014;49(5):243–250. doi: 10.1708/1668.18268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solís-García G, Jové-Blanco A, Chacón-Pascual A, Vázquez-López M, Castro-De Castro P, Carballo J, et al. Quality of life and psychiatric comorbidities in pediatric patients with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Rev Neurol. 2021;73(10):339–344. doi: 10.33588/rn.7310.2021046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wodrich DL, Benjamin E, Lachar D. Tourette's syndrome and psychopathology in a child psychiatry setting. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(11):1618–1624. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(09)66574-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kisely S, Alichniewicz KK, Black EB, Siskind D, Spurling G, Toombs M. The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in indigenous people of the Americas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:137–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health. 2020;16(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadock BJ. Kaplan & Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 2007.

- 31.Murphy TK, Lewin AB, Storch EA, Stock S. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with tic disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(12):1341–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ludolph AG, Roessner V, Münchau A, Müller-Vahl K. Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders in childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(48):821. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets are available through the corresponding author upon reasonable request.