Abstract

Background

Diarrheal illness is the second-most common cause of death in under-five children. Worldwide, it results in about 1.7 billion illnesses and 525,000 deaths among under-five children annually. It is the leading cause of malnutrition among under-five children. Different people use medicinal plants to treat diarrhea. The present study aimed to review the medicinal plants used to treat diarrhea by the people in the Amhara region and to diagnose whether the antidiarrheal activities of the medicinal plants have been confirmed by studies using animal models.

Methods

The author searched 21 articles from worldwide databases up to December 2022 using Boolean operators (“AND” and “OR”) and the terms “ethnobotanical studies,” “ethnobiology,” “traditional medicine,” “ethnobotanical knowledge,” and “Amhara region.”

Results

From the 21 studies reviewed, 50 plant species grouped into 28 families were reported to treat diarrhea by the people in the Amhara region. The top most used families were Lamiaceae (12%), Fabaceae (8%), Asteraceae, Cucurbitaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Poaceae (6% each). The modes of administration of the plant parts were orally 98.88% and topically 1.12%. The different extracts of 18 (or 36%) of the medicinal plants traditionally used to treat diarrhea by the people in the Amhara region have been proven experimentally in animal models.

Conclusions

The people in the Amhara region use different medicinal plants to treat diarrhea. Most of them take the medicinal plants orally. The traditional claim that 60% of medicinal plants are antidiarrheal has been confirmed in in vitro studies.

1. Background

Diarrhea is the second leading cause of under-five mortality in the world [1]. In 2019 alone, diarrheal diseases resulted in 6.58 billion incident cases, 99 million prevalent cases, 1.53 million deaths, and 80.9 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [2]. Among under-five children, diarrheal diseases resulted in 45.5 million DALYs and 370,000 deaths in 2019 [1, 2]. There are three clinical types of diarrhea, namely, acute watery diarrhea, which may last several hours or days and includes cholera; acute bloody diarrhea, also called dysentery; and persistent diarrhea, lasting 14 days or longer [1].

The Amhara region in Ethiopia experiences varying rates of diarrhea prevalence among under-five children, as indicated by several studies. A systematic review and meta-analysis published in PLOS ONE found that the overall prevalence of diarrhea in the region was 21%, which closely aligns with the national prevalence of 22% [3]. However, individual studies conducted in specific areas within the Amhara region showed different prevalence rates. For example, studies in Bahir Dar city reported a prevalence of 14.5% [4], while Farta district showed a higher prevalence of 29.9% among under-five children [5]. Other areas such as Jawi district, Debre Berhan town, Woldia town, Bahir Dar Zuria district, the rural area of the North Gondar zone, and flood-prone villages of the Fogera and Libo Kemkem districts also exhibited varying prevalence rates ranging from 15.5% to 29.0% [6–10]. Interestingly, a report suggested that there was no significant variation in prevalence between high and low hotspot districts in the region [11]. By integrating the wisdom and methodologies of traditional and modern medicine, a comprehensive and holistic healthcare approach can be established to prevent and treat diarrheal diseases in the Amhara region. This collaborative approach has the potential to improve the overall effectiveness of the healthcare system and advance the well-being of the local population.

Herbal medicines are believed to be effective in curing diarrhea, and for many years, plants and plant extracts have been used to treat various gastrointestinal ailments, including diarrhea [12, 13]. However, herbal medicines used in the treatment of diarrhea in African rural communities are unlikely to be replaced soon by modern medicines [14].

Nowadays, the integration of herbal medicine into modern medical practices is highly advocated [15]. Furthermore, herbal medicines have active components that serve as prototype leader compounds for the development of new drugs [16]. Documenting herbal medicines is thus documenting future drugs. Its ecological and cultural diversity make Ethiopia a rich source of herbal medicine [17]. However, due to environmental degradation, deforestation, a lack of recordkeeping, and potential acculturation, the plants and related indigenous knowledge in the nation are steadily diminishing [18]. Therefore, documentation of traditional knowledge regarding the usage of medicinal herbs is crucial to ensure its use by both present and future generations [19]. Hence, the present study aims to document medicinal plants from the Amhara region of Ethiopia that is traditionally used to treat diarrhea.

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Purpose

Documentation of medicinal plants of antidiarrheal importance is essential for local knowledge conservation, formulating antidiarrheal drugs from plant extracts, and the isolation of interesting compounds to synthesize future effective antidiarrheal drugs.

2.2. Search Strategy

The author searched articles from PubMed/Medline, Science Direct, Web of Science, and Google Scholar up to December 2022 by using Boolean operators (“AND” and “OR”) and the terms “diarrhea,” “dysentery,” “ethnobotanical studies,” “ethnobiology,” “traditional medicine,” “ethnobotanical knowledge,” and “Amhara region.”

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

The present study included articles written in English and published until December 2022 dealing with the documentation of indigenous knowledge and articles that possess the scientific names, family names, local names, plant parts used, routes of administration, the way of using plants, and the modes of preparation.

2.4. Quantitative Analysis of Ethnobotanical Data

Since the study is a review study, the author faced problems searching for data to compute many of the quantitative parameters. Accordingly, only relative frequency of citation (RFC) and family use value (FUV) are found to be applicable to this study. They were calculated using the following formulae:

| (1) |

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Relevant Articles

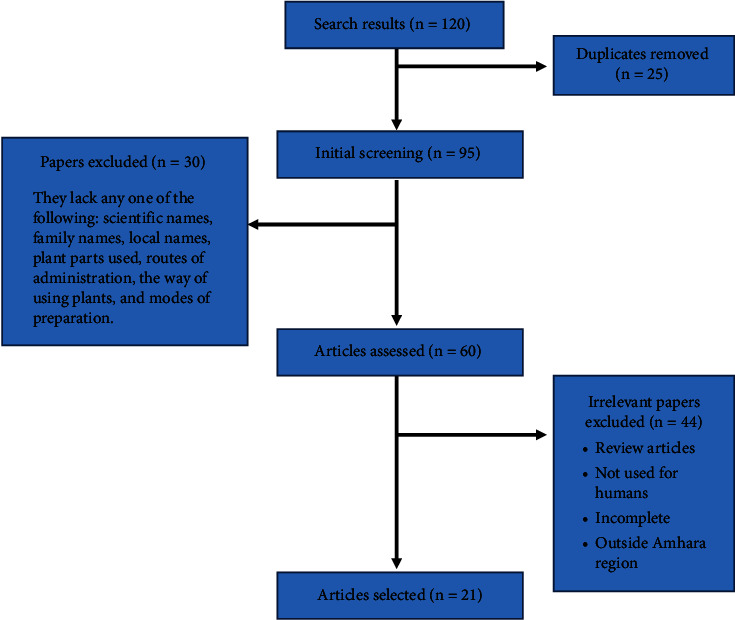

A literature search by the authors turned up a total of 120 published papers. 21 articles were chosen for this review after removing duplicates and irrelevant articles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the screening process for this review.

3.2. List of Identified Plants Used to Treat Diarrhea in the Study Area

From the 21 studies eligible for this study, 50 plant species were reported to treat diarrhea (Table 1). They are Acacia abyssinica [32], Acacia etbaica Schweinf [31], Aloe spp. [21], Anogeissus leiocarpa (A. Rich) Guill. and Perr [23], Artemisia abyssinica [24–26], Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile [21], Calpurnia aurea (Ait). Benth [20, 22, 29, 30, 32, 35, 36], Carica papaya L. [28], Carissa spinarum L. [26, 29, 30], Clutia abyssinica Jaub. and Spach. [22], Clutia lanceolata Forssk. [20], Coffea arabica L. [20, 29–31, 39], Cordia africana [27], Croton macrostachyus De [34], Cucumis ficifolius [31, 32], Eragrostis tef. (Zucc.) Trotter [33], Ficus thonningii Blume [34], Ficus vasta Forssk [35, 36], Heteromorpha arborescens (Spreng). Cham. and Schitdi. [22], Hordeum vulgare L. [31, 32], Justicia schimperiana (Hochst. ex Nees) T. Anders. [20], Leonotis ocymifolia [28, 35, 36]. Lepidium sativum L. [26, 28–30], Linum usitatissimum L. [22, 24], Malva parviflora L. [21], Mentha piperita L. [21, 25], Momordica foetida Schumach [20], Myrtus communis L. [34], Ocimum lamiifolium L. [29, 30], Gossypium barbadense L. [37], Plectranthus lactiflorus (Vatke) Agnew [26], Prunus persica (L.) Batsch [20], Punica granatum [32], Rumex abyssinicus [27], Rumex nepalensis (Spreng) [38], Ruta chalepensis L. [24, 29, 30], Salvia nilotica Jacq. [22], Satureja punctata R. Br. [22], Senna didymobotrya (Fresen) [31], Solanecio gigas (Vatke) C. jeffrey [22], Solanum nigrum L. [20], Sorghum bicolor (Moench) [22], Stephania abyssinica (Dillon and A. Rich.) Walp. [38], Syzygium guineense (Willd.) DC. [23], Verbascum sinaiticum Benth [20, 34, 38], Verbena officinalis L. [22, 26, 28–30, 40], Vernonia adoensis Sch.Bip.exWalp. [23], Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal [29, 30, 38, 40], Zehneria scabra (Linn. f.) Sond [20, 33], and Ziziphus spina-christi (L.) Desf [22].

Table 1.

List of plants identified and reported to be used to treat diarrhea in the study area.

| Family | Scientific name | Local name (Amh) | Plant parts used | Route of administration | Plant condition | Mode of preparation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae, just to have the column homogenized | Justicia schimperiana (Hochst. ex Nees) T.Anders | Smiza/Sensel | L | Oral | Dry | Smash, mix with water then drink the juice | [20] |

|

| |||||||

| Aloaceae | Aloe spp. | Eret | R | Oral | Fresh | Cutting is done to harvest the jelly juice | [21] |

|

| |||||||

| Apiaceae | Heteromorpha arborescens (Spreng). Cham. and Schitdi. | Yejib mirkuz | L | Oral | Fresh | Crush | [22] |

|

| |||||||

| Asteraceae | Vernonia adoensis Sch.Bip.exWalp | Etse mossie/mererug | R | Oral | Dry | Crashing the root and drinking the decoction | [23] |

| Artemisia abyssinica | Chikugn | R and L | Oral | Dry | Crush and mix with water, then drink | [24] | |

| Artemisia abyssinica | Chikugn | L | Oral | Dry | The dried leaf is ground, mixed with water, and drunk | [25] | |

| Artemisia abyssinica | Chikugn | R and L | Oral | Fresh | The fresh root and leaves are crushed, mixed with water, and then drunk | [26] | |

| Solanecio gigas (Vatke) C. jeffrey | yeshikoko gomen | L | Oral | Fresh | Crush | [22] | |

|

| |||||||

| Boraginaceae | Cordia africana | Wanza | Rb | Oral | Dry | Taking the maceration orally once daily until healed | [27] |

|

| |||||||

| Brassicaceae | Lepidium sativum L. | Feto | S | Oral | Dry | Seeds are ground into a paste-like food and then eaten or mixed with butter and water and then drunk | [28] |

| Lepidium sativum L. | Feto | S | Oral | Dry | The dry seeds are pounded, powdered, and mixed with water, and the solution has to be taken orally | [29] | |

| Lepidium sativum L. | Feto | S | Oral | Dry | The seeds are crushed and mixed with milk, and then, the mixture is drunk | [26] | |

| Lepidium sativum L. | Feto | S | Oral | Dry | The dry seeds are pounded, powdered, and mixed with water, and the solution is taken orally | [30] | |

|

| |||||||

| Caricaceae | Carica papaya L. | Papaya | S | Oral | Fresh | Ingest a few seeds with “Injera” for three days | [28] |

| Carissa spinarum L. | Agam | R | Oral | Dry | The dry root is pounded, powdered, salt is added, and it is made into a solution and drunk | [29] | |

| Carissa spinarum L. | Agam | L | Oral | Dry | The leaf is powdered, mixed with Coffea arabica L., and drunk | [26] | |

| Carissa spinarum L. | Agam | R | Oral | Dry | The dry root is pounded, powdered, salt is added, and it is made into a solution, which is then drunk | [30] | |

|

| |||||||

| Combretaceae | Anogeissus leiocarpa (A. Rich) Guill. and Perr | Kekera | Sb | Oral | Drinking the stem bark decoction | [23] | |

|

| |||||||

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucumis ficifolius | Yemidir embuay | R | Oral | Fresh | The root is crushed and mixed with water before being allowed to drink | [31] |

| Zehneria scabra (Linn. f.) Sond | Hareg eresa | L | Oral | Dry | Crush, chew, and then swallow juice | [20] | |

| Momordica foetida Schumach | Yekura hareg/Kuramechat | L | Oral | Fresh | Pound, squeeze, and then drink | [20] | |

| Cucumis ficifolius | Yemidir embuay | R | Oral | Fresh | The crushed fruits are mixed with water, and then about one liter is drunk | [32] | |

| Zehneria scabra (Linn. f.) Sond | Hareg eresa | L | Oral | Dry | Leaves are crushed and mixed with some fresh water, and then one cup of it is drunk | [33] | |

|

| |||||||

| Euphorbiaceae | Clutia lanceolata Forssk | Fiyele fej | R | Dermal | Dry | It is crushed and then tied on the neck region | [20] |

| Croton macrostachyus De | Bisana | L | Oral | Dry | Leaf powder mixed with water is taken orally | [34] | |

| Clutia abyssinica Jaub. and spach | Fiyele fej | L | Oral | Fresh | Crush | [22] | |

|

| |||||||

| Fabaceae | Acacia etbaica Schweinf | Girar | R | Oral | Dry | One cup of powdered dried root with water is taken | [31] |

| Senna didymobotrya (Fresen.) | Yeferenj digita | S | Oral | Dry/fresh | The seed is crushed and roasted, and then it is drunk with coffee | [31] | |

| Calpurnia aurea (Ait). Benth | Digita | L | Oral | Fresh | Fresh leaf soaked in water is given orally | [35] | |

| Calpurnia aurea (Ait). Benth | Digita | S | Oral | Dry | Grind and eat after pounding with honey | [20] | |

| Calpurnia aurea (Ait). Benth | Digita | L | Oral | Fresh | The fresh leaf is crushed, soaked in water for 2-3 hours, and decanted, and one glass is administered orally | [29] | |

| Calpurnia aurea (Ait). Benth | Digita | L | Oral | Fresh | The fresh leaf is crushed, soaked in water for 2-3 hours, and decanted, and one glass is administered orally | [36] | |

| Acacia abyssinica | Girar | R | Oral | Dry | The dried root is powdered and mixed with water, and one cup is drunk | [32] | |

| Calpurnia aurea (Ait). Benth | Digita | Fr | Oral | Dry | One dried and powdered pod of fruits is mixed with honey and taken before breakfast until you get relief | [32] | |

| Calpurnia aurea (Ait). Benth | Digita | L | Oral | Fresh | The fresh leaf is crushed, soaked in water for 2-3 hours, and decanted, and then one glass is administered orally | [30] | |

| Calpurnia aurea (Ait). Benth | Digita | L | Oral | Fresh | Crush and boil | [22] | |

|

| |||||||

| Lamiaceae | Leonotis ocymifolia | Yeferes zeng | L and Fr | Oral | Dry | Powder of dried fruit and leaf is mixed with honey and then given | [28] |

| Leonotis ocymifolia | Yeferes zeng | L and Fr | Oral | Dry | Dried leaf and fruit powder mixed with honey is given orally | [35] | |

| Ocimum lamiifolium L. | Damakesi | L | Oral | Fresh | Fresh leaf is boiled with tea and one cup of tea is drunk | [29] | |

| Leonotis ocymifolia | Feres zeng | L and Fr | Oral | Dry | The dried leaf and fruits are crushed, powdered, and mixed with honey, and one glass is taken orally | [36] | |

| Mentha piperita L. | Nana | L and S | Oral | Dry | Pound after mixing it with Nigella sativa and A. sativum | [21] | |

| Mentha piperita L. | Nana | L | Oral | Fresh | Pound the leaf, mix it with A. sativum and R. chalepensis, and then drink the mixture | [25] | |

| Plectranthus lactiflorus (Vatke) Agnew | Dibrk | L | Oral | Dry | The roots and leaves of P. lactiflorus are mixed with water, and the filtrate is drunk | [26] | |

| Ocimum lamiifolium L. | Damakesi | L | Oral | Fresh | The fresh leaves are boiled with tea, and then one cup of the mixture is drunk | [30] | |

| Salvia nilotica Jacq | Hulegeb | R | Oral | Fresh | Crush | [22] | |

| Satureja punctata R.Br | Etse-meaza/lomi kesie | R | Oral | Fresh | Use the unprocessed plant | [22] | |

|

| |||||||

| Linaceae | Linum usitatissimum L | Telba | S | Oral | Dry | The powder is boiled, and then it is drunk like soup | [24] |

| Linum usitatissimum L | Telba | S | Oral | Dry | Powder | [22] | |

|

| |||||||

| Malvaceae | Gossypium barbadense L | Tite | L | Oral | Dry | Powdered and mixed with water | [37] |

| Malva parviflora L. | Zebenya | L | Oral | Fresh | Pound | [21] | |

|

| |||||||

| Menispermaceae | Stephania abyssinica (Dillon and A. Rich.) Walp | Yedimet Ain | R | Oral | Dry | Chewing | [38] |

|

| |||||||

| Moraceae | Ficus vasta Forssk | Warka | S | Oral | Bark | Dried stem bark powder with salt is given orally for cattle | [35] |

| Ficus thonningii Blume | Chibha | R | Oral | Dry | The root is chewed | [34] | |

| Ficus vasta Forssk | Warka | Sb | Oral | Dry | The bark is crushed, powdered, mixed with salt, and given to eat | [36] | |

|

| |||||||

| Myrtaceae | Syzygium guineense [willd.] DC | Dokima | Sb/Rb | Oral | Dry | Mix the powder with honey/water and then drinking | [23] |

| Myrtus communis L. | Ades | L | Oral | Fresh | The juice of the leaf is taken orally in the morning | [34] | |

|

| |||||||

| Poaceae | Hordeum vulgare L. | Gebis | S | Oral | Dry | Seeds are immersed in water and allowed to germinate before being dried, roasted, and pulverized. The powder is then heated in water and drunk till the pain subsides | [31] |

| Hordeum vulgare L. | Tikur gebis | S | Oral | Dry | The seeds are soaked in water and made to germinate, dried, roasted, and powdered. Then the powder is boiled in water and drunk until relief is obtained | [32] | |

| Eragrostis tef. (Zucc.)Trotter | Nech teff | S | Oral | Dry | The floor porridge is eaten three times | [33] | |

| Sorghum bicolor (Moench) | Zengada | S | Oral | Dry | Powder | [22] | |

|

| |||||||

| Polygonaceae | Rumex nepalensis Spreng | Yewusha milas | R | Oral | Dry | Crushing | [38] |

| Rumex abyssinicus | Mekimeko | R | Oral | Dry | Orally take maceration once daily until the healing process is complete | [27] | |

|

| |||||||

| Punicaceae | Punica granatum | Roman | Fb | Oral | Fresh | The flesh of the fruit bark is eaten continuously against heavy diarrhea | [32] |

|

| |||||||

| Rhamnaceae | Ziziphus spina-christi (L.) Desf | Geba | Sb | Oral | Fresh | Use the unprocessed plant | [22] |

|

| |||||||

| Rosaceae | Prunus persica (L.) Batsch | Kega | L | Oral | Dry | Crush, immerse in water then give | [20] |

|

| |||||||

| Rubiaceae | Coffea arabica L. | Buna | S | Oral | Dry | The powder is mixed with honey and eaten | [31] |

| Coffea arabica L. | Buna | Fr | Oral | Dry | Grind and eat with honey | [20] | |

| Coffea arabica L. | Buna | S | Oral | Dry | The dry seed is roasted, powdered, mixed with honey, and one or two spoons are taken in the morning for three days | [29] | |

| Coffea arabica L. | Buna | S | Oral | Dry | Roast the powder and take it with honey on an empty stomach | [39] | |

| Coffea arabica L. | Buna | S | Oral | Dry | The dry seed is roasted, powdered, mixed with honey, and one or two spoons are taken in the morning for three days | [30] | |

|

| |||||||

| Rutaceae | Ruta chalepensis L | Tena Adam | L | Oral | Fresh | The fresh leaf, together with salt (concoction), is chewed | [29] |

| Ruta chalepensis L | Tena Adam | S | Oral | Dry | The pounded seed will be mixed with coffee, then drunk | [24] | |

| Ruta chalepensis L. | Tena Adam | L | Oral | Fresh | Chewing the fresh leaf together with salt (concoction) | [30] | |

|

| |||||||

| Scrophulariaceae | Verbascum sinaiticum Benth | qetetina/Daba Keded | R | Oral | Dry | Crush and drink with water | [20] |

| Verbascum sinaiticum Benth | qetetina/Daba Keded | R, L, and S | Oral | Dry | Crushing | [38] | |

| Verbascum sinaiticum Benth | qetetina/Daba Keded | R | Oral | Fresh | The juice of the root is taken orally | [34] | |

|

| |||||||

| Solanaceae | Solanum nigrum L. | Awut | L | Oral | Dry | Leaves are crushed and chewed, and then the juice is swallowed | [20] |

| Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal | Giziewa | L | Oral | Fresh/Dry | Squeezing, crushing | [29, 38] | |

| Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal | Giziewa | L | Oral | Dried or fresh | Mix the powder of 3 leaves with water and drink | [40] | |

| Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal | Giziewa | L | Oral | Fresh | The fresh leaves are crushed, squeezed, mixed with water, and then drunk | [30] | |

|

| |||||||

| Verbenaceae | Verbena officinalis-L | Atuch | R | Oral | Fresh | Sap of the fresh root is chewed and swallowed for three days | [28] |

| Verbena officinalis-L | Atuch | L | Oral | Fresh | The fresh leaves are crushed, mixed with water, and given orally | [29] | |

| Verbena officinalis-L | Atuch | R & S | Oral | Fresh | Pound the leaf, stem, and root, mix them with water, and then drink | [26] | |

| Verbena officinalis-L | Atuch | R | Oral | Fresh | Extract the root powder with water, filter it, and take the filtrate on an empty stomach | [40] | |

| Verbena officinalis-L | Atuch | L | Oral | Fresh | The fresh leaves are crushed, mixed with water, and given orally | [30] | |

| Verbena officinalis-L | Atuch | R | Oral | Fresh | Crush | [22] | |

|

| |||||||

| Zygophyllaceae | Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile (Zygophyllaceae) | Bedena | L | Oral | Fresh | Crush to collect juice | [21] |

Note. Plant parts used (Fb = fruit bark, Fr = fruit, L = Leaf, R = root, Rb = root bark, S = seed, and Sb = stem bark).

The medicinal plants used by the population in the Amhara region for the treatment of diarrhea are grouped into 28 families and 50 species, as indicated in Table 1. The Lamiaceae family was represented by six (12%) species and the Fabaceae family by four (8%) species. Asteraceae, Cucurbitaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Poaceae were represented by three (6%) species each. Caricaceae, Malvaceae, Moraceae, Myrtaceae, Polygonaceae, and Solanaceae were represented by two (4%) species each. Apiaceae, Acanthaceae, Aloaceae, Boraginaceae, Brassicaceae, Combretaceae, Linaceae, Menispermaceae, Punicaceae, Rhamnaceae, Rosaceae, Rubiaceae, Rutaceae, Scrophulariaceae, Verbenaceae, and Zygophyllaceae were represented by a single (2%) species each. Only two modes of administration of the plant parts were used to treat diarrhea. Almost all (98.88%) were applied orally, and only 1.12% dermally (topically).

3.3. Quantitative Analyses of Ethnobotanical Data

3.3.1. Relative Frequency of Citations (RFC)

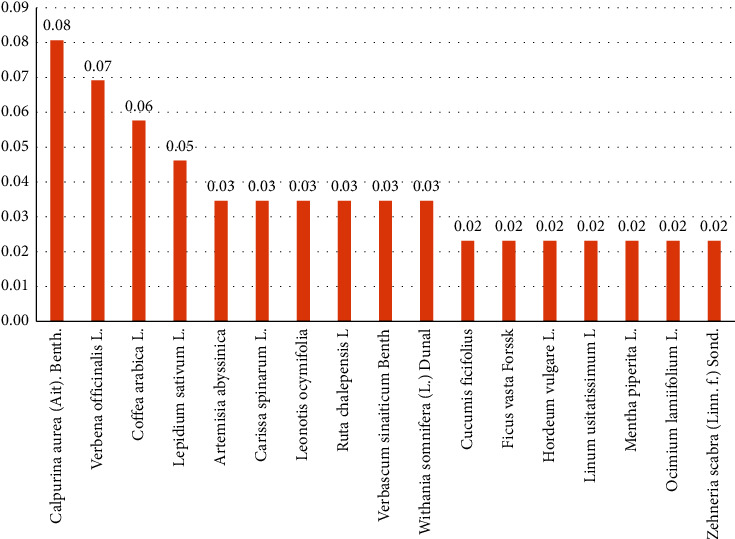

The relative frequency of citations (RFC) ranged from 0.01 to 0.08. The top four cited medicinal plants for their antidiarrheal activities were Calpurnia aurea (Ait). Benth., Verbena officinalis L., Coffea arabica L., and Lepidium sativum L., with RFC values of 0.08, 0.07, 0.06, and 0.05, respectively. Artemisia abyssinica, Carissa spinarum L., Leonotis ocymifolia, Ruta chalepensis L., Verbascum sinaiticum Benth, and Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal all had the same RFC value of 0.03. Furthermore, 14% and 66% of the species had RFC values of 0.02 and 0.01, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative frequency of citations (RFC) of 17 of the 50 species.

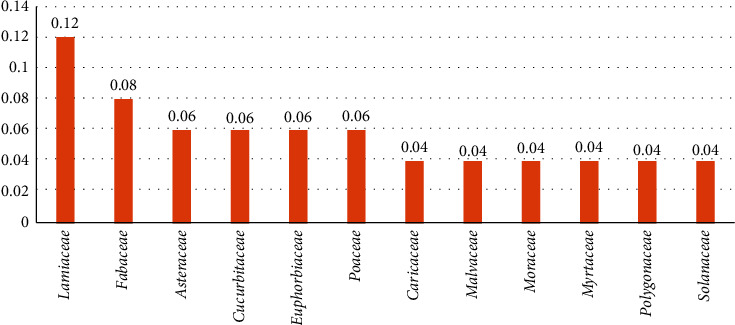

3.3.2. Family Use Value (FUV)

The family use value (FUV) for the 28 families ranged from 0.01 to 0.12. Lamiaceae was the most frequently used plant family to treat diarrhea (FUV = 0.12), followed by Fabaceae (FUV = 0.08), and Asteraceae, Cucurbitaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Poaceae, all with an FUV of 0.06. Additionally, 21.4% and 57.1% of the families had FUVs of 0.04 and 0.02, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Family use values of 12 of the 28 families.

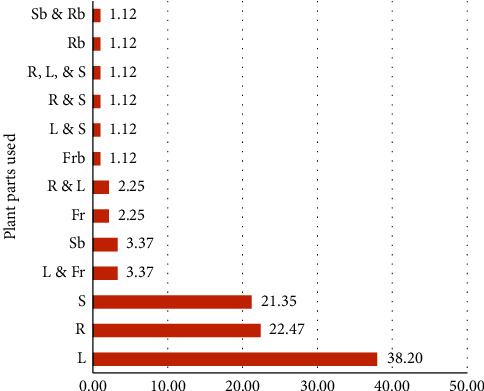

3.4. Plant Parts Used to Treat Diarrhea

The top five plant parts used to treat diarrhea were leaves (38.2%), roots (22.47%), stems (21.35%), leaves and fruits (3.37%), and stem bark (3.37%) (Figure 4). It was followed by fruit (2.25%), root (2.25%), and leaf (2.25%), with the remaining plant parts and combinations of plant parts contributing 1.12% each to the treatment of diarrhea.

Figure 4.

Plant parts used for the treatment of diarrhea. Note: plant parts used (Fb = fruit bark, Fr = fruit, L = Leaf, R = root, Rb = root bark, S = seed, and Sb = stem bark).

3.5. Gap Analysis of Whether the Traditional Claims Are Tested by In Vitro Trials

No in vitro trials have been conducted for Acacia etbaica, Acacia abyssinica, Aloe spp., Anogeissus leiocarpa, Artemisia abyssinica, Balanites aegyptiaca, Carissa spinarum, Cucumis ficifolius, Eragrostis tef, Ficus vasta, Heteromorpha arborescens, Hordeum vulgare, Justicia schimperiana, Linum usitatissimum, Malva parviflora, Mentha piperita, Momordica foetida, Gossypium barbadense, Prunus persica, Satureja punctate, Senna didymobotrya, Solanecio gigas, Solanum nigrum, Verbascum sinaiticum, Verbena officinalis, and Vernonia adoensis (Table 2). Therefore, future research studies can test their effectiveness against castor oil-induced diarrhea in animal models.

Table 2.

In vivo trials of medicinal plants to confirm the traditional claim of their utilization in treating diarrhea.

| Medicinal plant | Plant parts used | Extraction method | The effects obtained | Chemical composition | Proposed mechanism of action | References for trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calpurnia aurea | Leaves | Maceration in 80% methanol | Reduced the time of diarrhea onset, defecation frequency, and fecal weight | Alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, terpenoids, and saponins | Antimicrobial activity | [41] |

| Clutia abyssinica | Roots | Cold maceration in 80% methanol | Prolonged the onset of diarrhea, and significantly reduced the number of wet and total stools at doses of 200 and 400 mg/kg | Tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, phenols, terpenoids, anthraquinones, and glycosides | Antisecretory effect, anti-inflammatory activity, and inhibition of peristaltic movements | [42] |

| Coffea arabica | Seeds | Cold maceration in 80% methanol | At a dosage of 400 mg/kg, there was a significant prolongation of the onset of diarrhea and a decrease in the total number of feces | Alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, tannins, saponins, steroids, anthraquinones, glycosides, and terpenoids | Anti-inflammatory activity, increased sympathetic nerve activity, antioxidant activity, increase of the intestinal absorption of water and electrolytes | [43] |

| Cordia africana | Bark | Maceration in 80% methanol | Reduction in castor oil-induced diarrhea and intestinal fluid accumulation in a dose-dependent manner | Phenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, and saponins | Increase in water and electrolyte absorption or decrease the secretion of fluid and electrolytes, blocking the prostaglandin receptors | [44] |

| Croton macrostachyus | Leaves | Soxhlet extraction with chloroform and methanol | Delayed onset of diarrhea, reduced stool frequency, and lighter feces | Alkaloids, steroids, and terpenoids in the chloroform fraction; alkaloids, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, and cardiac glycosides in methanol fraction; and saponins, tannins, and alkaloids in aqueous fraction | Inhibition of intestinal motility and hydro-electrolytic secretion, inhibition of the intestinal secretory response induced by prostaglandins E2, promotion of fluid and electrolyte absorption | [45] |

| Ficus thonningii | Leaves | Aqueous methanolic extraction | An initial increase in purgation was observed by the 2nd hour of the test, followed by a subsequent period of constipation | Tannins, flavonoids, saponins, and anthraquinone glycosides | A dose-related reduction in intestinal motility | [46] |

| Leonotis ocymifolia | Leaves and fruits | Cold maceration in 80% methanol | Reduced diarrhea frequency, delayed onset of diarrhea, and decreased number of defecation occurrences | Alkaloids, tannins, flavonoids, and saponins | The antisecretory effect, antimotility effect, and reduction of intestinal transit | [47] |

| Lepidium sativum | Seeds | Maceration in 70% methanol | The doses of 100 and 300 mg/kg exhibited a significant antidiarrheal effect | Alkaloids, saponins, and anthraquinones | Reversing the CCh and high K + -induced contractions, dual blockade of muscarinic receptors, and Ca++ channels | [48] |

| Myrtus communis | Leaves | Maceration in 80% methanol | Significant delays of the onset of diarrhea and decreases of the frequency and weight of fecal outputs, at 200 and 400 mg/kg extract. A significant effect on the frequency and weight of wet feces, as well as the total fecal output, at 100 mg/kg of the extract | Terpenoids, flavonoids, tannins, glycosides, and saponins | Anti-inflammatory activity, suppression of the biosynthesis of eicosanoids, reduction of gastrointestinal motility | [49] |

| Ocimum lamiifolium | Leaves | Maceration in 80% methanol | The intervention resulted in a reduction in the onset of diarrhea, the number of wet feces, the weight of fresh feces, and the fluid content of feces, as well as reductions in both the volume and weight of intestinal content | Alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, tannins, saponins, steroids, glycosides, anthraquinones, terpenoids | Anti-inflammatory activity, antioxidant activities, inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, reduction of intestinal secretion, decrease in the synthesis of nitric oxide, and inhibition of intracellular Ca2+ inward current | [50] |

| Punica granatum | Peels | Aqueous extract (decoction) | Reduction in diarrhea, inhibition of wet or unformed feces production, and suppression of gastrointestinal propulsive action | Tannins, alkaloids, and flavonoids | Inhibition of intestinal motility and accumulation of intestinal fluid | [51] |

| Ruta chalepensis | Leaves | Maceration in 80% methanol | Prolonged the onset time of diarrhea and decreased the stooling frequency at 200 mg/kg and 400 mg/kg. Additionally, there was a reduction in the percentage of mean fecal output | Alkaloids, tannins, saponins, flavonoids, cardiac glycosides, terpenoids, and steroids | Inhibition of the production of prostaglandin E2 and an antispasmodic effect | [52] |

| Sorghum bicolor | Seeds | Maceration in 80% methanol | Observation of reduced intestinal fluid weight (in grams) and delayed charcoal meal propulsion through the gastrointestinal tract | Phenols, flavonoids, tannins, terpenoids, and steroids | Inhibition of motility and secretion of the gastrointestinal tract | [53] |

| Stephania abyssinica | Leaves and roots | Methanol and aqueous extract | Exhibiting an inhibitory effect on both gastrointestinal propulsion and fluid secretion, as well as demonstrating antispasmodic activity | Isoqiunol alkaloids | Decrease of hypermotility, inhibition of prostaglandin biosynthesis, anticholinergic effect, and histamine decrease | [54] |

| Syzygium guineense | Leaves | Maceration in 80% ethanol | Inhibition of intestinal propulsion, reduction in the number of watery stools, reduction of intraintestinal fluid volume, and passage of watery stool | Pentacyclic triterpenes and luteolin | Inhibition of acetylcholine-mediated intestinal smooth muscle contraction; stimulation of dopamine D2 receptor; and degradation of acetylcholinesterase | [55] |

| Withania somnifera | Leaves | Maceration in 80% methanol | Delayed the diarrhea onset at 200 and 400 mg/kg; reduced defecation of diarrheal stools (number of wet stools), total stools (wet and dry), and weight of fresh stools; decreased intraluminal fluid accumulation and charcoal meal movement | Flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, steroids, phenols, terpenoids, and saponins | Antisecretory action, enhancing of absorption, and/or anti-motility action, anti-inflammatory activity, antispasmodic activity, calcium antagonism action | [56] |

| Zehneria scabra | Leaves | Maceration in 80% methanol | Reduced the mean stool score, wet feces, defecations, stool fluid content, intestinal motility, and weight of intestinal content | Tannins, saponins, anthraquinones, O-anthraquinones, and phenols | Inhibition of secretion, reducing intraluminal fluid accumulation, or enhancing water absorption but not delaying motility | [57] |

| Ziziphus spina-christi | Stem bark | Soxhlet extraction with methanol | Copious diarrhea was inhibited, intraluminal accumulation of fluid volume was reduced, and intestinal transit of charcoal meal decreased | Glycosides, resins, saponins, and tannins | Tannins inhibit electrolyte permeability and prostaglandin release and display antimicrobial activity. They also reduce secretion and enhance intestinal mucus resistance through protein tannate formation | [58] |

However, different extracts of 18 medicinal plants traditionally used to treat diarrhea by the people in Amhara region (36%) have been proved experimentally in animal models. They are Calpurnia aurea [41], Clutia abyssinica [42], Coffea arabica [43], Cordia africana [44], Croton macrostachyus [45], Ficus thonningii [46], Leonotis ocymifolia [47], Lepidium sativum [48], Myrtus communis [49], Ocimum lamiifolium [50], Punica granatum [51], Ruta chalepensis [52], Sorghum bicolor [53], Stephania abyssinica [54], Syzygium guineense [55], Withania somnifera [56], Zehneria scabra [57], and Ziziphus spina-christi [58] (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Traditionally, the people in the Amhara region use different plants to treat diarrhea. In the following paragraphs, the plants used to treat diarrhea, their active components, their mechanisms of action, and, if confirmed, in vivo trials are discussed.

Acacia etbaica Schweinf and Acacia abyssinica may contain a variety of secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, anthraquinones, triterpenes, and glycosides, as shown in Acacia etbaica [59]. Acacia nilotica Willd's bark methanol extract demonstrated in vivo antidiarrheal activity against castor oil and magnesium sulfate-induced diarrhea, as well as barium chloride-induced peristalsis, using Swiss albino mice. It also exhibited in vitro antimicrobial activity against common diarrhea-causing microorganisms [60]. Similar effects could be attributed to Acacia etbaica and Acacia abyssinica extracts. The antidiarrheal activity of Acacia etbaica and Acacia abyssinica is likely attributed to their ability to modulate intestinal motility, preserve intestinal mucosal integrity, promote fluid absorption, activate antioxidant pathways, exert anti-inflammatory effects, demonstrate antimicrobial activity against diarrheal pathogens, suppress intestinal secretion, and modulate gut microflora.

Aloe spp. contains aloe emodin, aloin, aloesin, emodin, and acemannan as major active compounds [61]. Its antidiarrheal activity may be due to the anti-inflammatory, intestinal motility modulatory, antimicrobial, intestinal mucosal protection, and ion transport regulatory activities of its active components.

Anogeissus leiocarpa (A. Rich) Guill and Perr's bark decoction is drunk to treat diarrhea [23]. Its aqueous leaf extract significantly inhibited castor oil-induced diarrhea in rats through the inhibition of intestinal transit and reduction of the volume of the intestinal content [62]. This effect may be attributed to the activities of its components such as alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins, tannins, phenols, and glycosides [63], which act as its active constituents.

The dry or fresh leaves and roots of Artemisia abyssinica are ground, mixed with water, and drunk [25, 26] to treat diarrhea, and the active components of the genus, including 1,8-cineole, β-pinene, thujone, artemisia ketone, camphor, caryophyllene, camphene, and germacrene D [64], may contribute to its antidiarrheal activity.

The fresh leaves of Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile are crushed, and the juice is swallowed to treat diarrhea [21]. The antidiarrheal activities of this plant may be attributed to its phytochemicals such as saponins, coumarins, triterpenes, tannins, and steroids [65].

The leaves, seeds, and fruits of Calpurnia aurea (Ait) Benth (Fabaceae) are applied to treat diarrhea. The antidiarrheal activity of the 80% methanol extract of this plant has been proven by its effect on castor oil-induced diarrhea in mice, which significantly reduced the time of onset of diarrhea, the frequency of defecation (total number of fecal output), and the weight of feces. The extract also showed good antimicrobial activity against all tested organisms [41]. The antidiarrheal activities of this plant may be attributed to its secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, tannins, flavonoids, saponins, steroids, and phlobatannins [66].

The roots and leaves of Carissa spinarum L. (Apocynaceae) are utilized for managing diarrhea. Its potential antidiarrheal properties may be attributed to its bioactive constituents, such as acids, glycosides, terpenoids, alkaloids, tannins, and saponins [67]. The juice of the fresh leaves of Clutia abyssinica Jaub and Spach is taken orally as a remedy for diarrhea. This practice is supported by an in vivo study, where its hydromethanolic root extract significantly delayed the onset of diarrhea and reduced the number of wet and total stools in a castor oil-induced diarrheal model [42]. Conversely, the crushed roots of Clutia lanceolata Forssk (Euphorbiaceae) are applied to the neck to treat diarrhea [20]. The antidiarrheal activities of this plant may be attributed to its secondary metabolites, including 5-methylcoumarins, diterpenes with a secolabdane skeleton, essential oils, alkaloids, anthraquinones, cardiac glycosides, flavonoids, phenolics, saponins, steroids, tannins, and terpenoids [68].

The dried seeds and fruits of Coffea arabica L. are used in coffee preparations mixed with honey, which is taken orally to treat diarrhea. The antidiarrheal activity of C. arabica was confirmed by an in vivo study against castor oil-induced diarrhea in Swiss albino mice [43]. Coffee's antidiarrheal effects are likely attributed to its bioactive constituents, such as chlorogenic acids and catechins [69].

The dried root bark of Cordia africana (Boraginaceae) is macerated and taken orally once daily to treat diarrhea. This practice has been supported by an in vivo study, where C. africana prevented castor oil-induced diarrhea and regulated intestinal motility [44]. This effect may be due to the individual, additive, or synergistic activities of its active components, such as flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, terpenoids, saponins, steroids, anthraquinones, carbohydrates, and proteins [70].

The dry leaves of Croton macrostachyus De. (Euphorbiaceae) are powdered, mixed with water, and taken orally to treat diarrhea [34]. In the castor oil-induced model, the chloroform and methanol fractions of this plant significantly delayed diarrheal onset and decreased stool frequency and weight of feces [45]. Its activity may be due to individuals or combinations of its active components, such as flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, saponins, terpenoids, and phenols [71].

The fresh root juice of Cucumis ficifolius (Cucurbitaceae) is taken orally to treat diarrhea. The Cucurbitaceae family is rich in terpenoids, glycosides, alkaloids, saponins, tannins, and steroids [72]. The antidiarrheal activities of this plant may be attributed to the mentioned secondary metabolites.

Porridge made from the seeds of Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) is eaten three times a day to treat diarrhea. The antidiarrheal activity of E. tef may be attributed to its polyphenols, including the phenolic acids p-coumaric, ferulic, protocatechuic, gentisic, vanillic, syringic, caffeic, cinnamic, and p-hydroxybenzoic, and the flavonoids apigenin, luteolin, and quercetin [73].

Chewing the dry roots of Ficus thonningii Blume is practiced to treat diarrhea. The antidiarrheal activity of this plant may be due to its phytochemicals such as tannins, flavonoids, saponins, and anthraquinone glycosides [46].

Heteromorpha arborescens (Spreng.) is utilized to treat diarrhea which may be due to its active components such as phenols, proanthocyanidins, flavonoids, alkaloids, and saponins [74]. Justicia schimperiana (Hochst. ex Nees) T. Anders is used for the treatment of diarrhea that may be due to its active components, such as flavonoids, alkaloids, glycosides, phenols, saponins, steroids, and terpenoids [75].

The traditional application of Leonotis ocymifolia for diarrhea treatment is supplemented by a study conducted in Ethiopia. According to this study, 80% methanol leaf and fruit extracts of L. ocymifolia reduced the frequency of wet stools, the watery content of diarrhea, and delayed the onset of diarrhea [47]. Its antidiarrheal activity may be attributed to its chemical constituents, such as phenolics, flavonoids, and alkaloids [76]. Linum usitatissimum L. has traditionally been used to treat diarrhea, and this may be due to its components such as methyl linolenate, methyl linoleate, α-linolenic acid, α-terpinene, terpinen-4-ol, 4-cymene, and α-pinene [77].

The leaves of Malva parviflora L. are used to treat diarrhea which may be due to its active components such as sterols, hydroxycinnamic, anthocyanins, and ferulic acid [78]. The fresh leaves of Momordica foetida Schumach are used to treat diarrhea. Its antidiarrheal activity may be associated with its active components, such as methyldecanoate, methyl dodecanoate, methyl tetradecanoate, methyl hexadecanoate, ethyl hexadecanoate, methyl-9-octadecenoate, methyl-8,11-octadecadienoate, methyl-9,12,15-octadecatrienoate, bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, and methyl-18-methylnonadecanoate [79].

Similarly, the leaves of Myrtus communis L. [34] are utilized for the treatment of diarrhea. The traditional claim was confirmed by a study where the 80% methanol extract, as well as the chloroform (CF) and methanol (MF) fractions, of this plant significantly prolonged the onset of diarrhea, reduced the frequency of bowel movements, and decreased fecal output weight [49]. These antidiarrheal properties can be attributed to the presence of active components, including polyphenols, myrtucommulone, semimyrtucommulone, 1,8-cineole, α-pinene, myrtenyl acetate, limonene, linalool, and α-terpinolene [80].

The fresh leaves of Ocimum lamiifolium L. are used to manage diarrhea by boiling them with tea and consuming a cup of the prepared infusion. This was corroborated by an in vivo study in which the 80% methanol extract and fractions of this plant demonstrated a substantial impact on the fluid content of feces across all tested doses. Additionally, the n-butanol and distilled water fractions exhibited significant effects on the onset of diarrhea, whereas the n-hexane fraction displayed noteworthy effects on the number of wet feces, onset of diarrhea, and fluid content of feces at all tested doses [50]. The antidiarrheal activities of this plant may be attributed to its phytocomponents, such as tricyclene, bornyl acetate, α-pinene, α-terpinene, isoledene, and β-pinene.

The roots and leaves of Plectranthus lactiflorus (Vatke) Agnew are mixed with water, and the filtrate is consumed to treat diarrhea. The antidiarrheal activities of this plant may be attributed to its active components such as carvacrol, γ-terpinene, caryophyllene, p-cymene, trans-α-bergamotene, and thymoquinone [81]. The flesh fruit bark of Punica granatum is consumed to combat severe diarrhea [32]. Its aqueous extract displayed antidiarrheal activities against castor oil-induced diarrhea in rats [51] which may be due to its chemical components, such as hydrolyzable tannins (punicalin, punicalagin, ellagic acid, and gallic acid) and flavonoids (anthocyanins and catechins) [82].

The crushed dry roots of Rumex nepalensis (Spreng) are taken orally to treat diarrhea [38]. In an in vivo study, its hydromethanolic extract markedly delayed the onset of diarrhea and reduced the weight of wet and total feces at the test doses in a castor oil-induced diarrheal model [83]. The possible antidiarrheal activities of this plant may be related to its active components such as anthraquinones, naphthalenes, stilbenoids, flavonoids, terpenoids, phenols, and their derivatives [84].

The fresh leaves of Ruta chalepensis L. together with salt are chewed to treat diarrhea. Its hydromethanol (80% ME) extract prolonged the onset of diarrhea in mice and significantly reduced the frequency of stooling and weight of feces in a castor oil-induced diarrheal model [52]. The antidiarrheal activity of this medicinal plant may be ascribed to its chemical constituents such as 2-undecanone, piperonyl piperazine, 2-decalone, 2-dodecanone, decipidone, and 2-tridecanone [85]. The fresh roots of Salvia nilotica Jacq. are crushed and taken orally to treat diarrhea. The hydroalcoholic extract of another Salvia species (S. schimperi) exerted significant and dose-related antidiarrheal activity [86]. The antidiarrheal activity of this plant may be related to its constituents, including β-phellandrene, δ-3-carene, and caryophyllene oxide, which may have antidiarrheal properties [87].

The seed of Senna didymobotrya (Fresen.) is crushed, roasted, and drunk with coffee as a treatment for diarrhea. The antidiarrheal activity of this plant has not yet been tested. Its potential antidiarrheal activities may be associated with its phytocomponents, such as steroids, terpenoids, anthraquinones, tannins, saponins, glycosides, flavonoids, alkaloids, and phenols [88]. Traditionally, the leaves of Solanecio gigas (Vatke) C. Jeffrey are crushed and taken orally to treat diarrhea. Its antidiarrheal activity may be related to its active components such as methylene chloride, sabinene, 1-nonene, terpinen-4-ol, camphene, γ-terpinene, α-phellandrene, β-myrcene, 1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-carboxamide, 4,4′-azobis-2,2′-dioxide, α-terpinene, 1-octanamine, N-methyl, and ρ-cymene [89].

The dried leaves of Solanum nigrum L. are crushed and chewed, and the juice is swallowed to treat diarrhea. The methanol extracts of the roots and leaves of another Solanum species (S. asterophorum Mart) significantly and dose-relatedly inhibited the frequency of both solid and liquid stools in mice [90]. Its components, such as steroidal saponins, steroidal alkaloids, flavonoids, coumarin, lignin, organic acids, volatile oils, and polysaccharides [91], may contribute to the antidiarrheal activity of S. asterophorum.

Traditionally, the seed powder of Sorghum bicolor (Moench) is taken orally to treat diarrhea. An in vivo evaluation of the 80% methanol crude extract of the seeds of this plant in mice demonstrated inhibitory activity against castor oil-induced diarrhea, castor oil-induced enteropooling, and castor oil-induced gastrointestinal transit [53]. The antidiarrheal activity of this plant may be linked to its active constituents such as proteins, lipids, ash, calcium, copper, iron, zinc, gallic acid, and ferulic acids [92].

The dry roots of Stephania abyssinica (Dillon and A. Rich) Walp are chewed to treat diarrhea. The traditional claim was also evaluated in an in vivo study in mice using castor oil-induced diarrhea, which significantly prolonged the time of diarrheal induction, increased diarrhea-free time, reduced the frequency of diarrhea episodes, decreased the weight of stool, and decreased the general diarrheal score in a dose-dependent way [54]. The antidiarrheal activities of S. abyssinica could be attributed to the active components, including alkaloids, flavonoids, lignans, steroids, terpenoids, and coumarins [93].

Syzygium guineense (Willd.) DC's root or stem bark is dried, powdered, mixed with honey, and drunk orally as a treatment for diarrhea [23]. Its antidiarrheal activity may be attributed to its constituents, such as caryophyllene oxide, d-cadinene, viridiflora, epi-a-cadinol, a-cadinol, cis-calamenen-10-ol, citronellyl pentanoate, b-caryophyllene, and a-humulene [94].

The dry root of Verbascum sinaiticum Benth and Verbena officinalis L. is crushed and drunk with water to halt diarrhea. The traditional claim for the antidiarrheal activity of this plant has not yet been tested. The antidiarrheal activities of this plant may be attributed to its active compounds, such as sterols, saponins, flavonoids, phenylethanoids, and iridoid glycosides [95]. To treat diarrhea, the root decoction of Vernonia adoensis Sch.Bip.exWalp is taken orally [23]. Its active components phenols, saponins, flavonoids, glycosides, and tannins [96] may contribute to the antidiarrheal activities of this plant.

Fresh/dry leaves of Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal are crushed or squeezed and taken orally to treat diarrhea [29, 38]. In Swiss albino mice, an 80% methanol extract and solvent fractions of the leaves of this plant have been found to significantly delay the onset of diarrhea, decrease the number and weight of stools, reduce the volume and weight of intestinal contents, and decrease the motility of charcoal meal [56]. The antidiarrheal activity of this plant may be attributed to its active compounds, such as withanolides, condensed tannins, flavonoids, glycosides, free amino acids, alkaloids, steroids, volatile oils, and reducing sugars [97].

The dry leaves of Zehneria scabra (Linn. f.) Sond are crushed and chewed, and the juice is swallowed to stop diarrhea. The 80% methanolic leaf extract of this plant in mice resulted in a significant reduction in mean stool score, stool frequency, and fecal fluid content [57]. Its antidiarrheal activity may be due to its chemical composition, such as 3,10-dihydroxy-5,6-epoxy-β-ionol; 3,10-dihydroxy-5,6-epoxy-β-ionyl-10-O-β-D-glucopyranoside; cucumegastigmane I; corchoionoside C; indole-3-carboxylic acid; methyl indole-3-carboxylate; and benzyl-O-β-D-glucopyranoside [98]. The fresh stem bark of Ziziphus spina-christi (L.) Desf is taken orally as a treatment for diarrhea. Its antidiarrheal activities may be attributed to its active components such as alkaloids, sterols (β-sitosterol), flavonoids, triterpenoids, sapogenins, and saponins [99].

Plant secondary metabolites play their antidiarrheal roles using various mechanisms. For example, plants containing alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins, glycosides, and terpenoids modulate intestinal motility [100–104]; tannins and saponins preserve intestinal mucosal integrity [105, 106]; alkaloids, flavonoids, coumarins, glycosides, and terpenoids promote fluid absorption [101, 107, 108], flavonoids activate antioxidant pathways [109]; flavonoids, coumarins, glycosides, and terpenoids exert anti-inflammatory effects [110–114]; flavonoids, saponins, glycosides, and terpenoids demonstrate antimicrobial activity against diarrheal pathogens [115–118], tannins, saponins, and terpenoids suppress intestinal secretions [105, 119]; and terpenoids modulate gut microflora [108].

Acacia etbaica, Acacia abyssinica, Anogeissus leiocarpa, Calpurnia aurea, Carissa spinarum, Clutia lanceolata, Cordia Africana, Croton macrostachyus, Cucumis ficifolius, Heteromorpha arborescens, Justicia schimperiana, Leonotis ocymifolia, Senna didymobotrya, Solanum nigrum, Stephania abyssinica, Withania somnifera, and Ziziphus spina-christi have alkaloids as their active components. Therefore, they may modulate intestinal motility and promote fluid absorption. Alkaloids interact with opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal system, reducing bowel movement frequency [100, 120].

Acacia etbaica, Acacia abyssinica, Anogeissus leiocarpa, Calpurnia aurea, Clutia lanceolata, Cordia Africana, Croton macrostachyus, Eragrostis tef, Ficus thonningii, Heteromorpha arborescens, Justicia schimperiana, Leonotis ocymifolia, Punica granatum, Rumex nepalensis, Senna didymobotrya, Solanum nigrum, Stephania abyssinica, Verbascum sinaiticum, Vernonia adoensis, Withania somnifera, and Ziziphus spina-christi possess flavonoids. Consequently, their antidiarrheal activities may be achieved through the modulation of intestinal motility, promotion of fluid absorption, activation of antioxidant pathways, exertion of anti-inflammatory effects, and antimicrobial activity against diarrheal pathogens.

Acacia etbaica, Acacia abyssinica, Anogeissus leiocarpa, Balanites aegyptiaca, Calpurnia aurea, Carissa spinarum, Clutia lanceolata, Cordia Africana, Croton macrostachyus, Cucumis ficifolius, Ficus thonningii, Heteromorpha arborescens, Justicia schimperiana, Senna didymobotrya, Solanum nigrum, Verbascum sinaiticum, and Ziziphus spina-christi contain saponins. As a result, these plants may treat diarrhea by modulating intestinal motility, preserving intestinal mucosal integrity and antimicrobial activity against diarrheal pathogens, and suppressing intestinal secretions.

Acacia etbaica, Acacia abyssinica, Anogeissus leiocarpa, Carissa spinarum, Clutia lanceolata, Cucumis ficifolius, Ficus thonningii, Justicia schimperiana, Senna didymobotrya, Verbascum sinaiticum, Vernonia adoensis, and Withania somnifera have glycosides as their active components. Therefore, they may modulate intestinal motility, promote fluid absorption, exert anti-inflammatory effects, and exert antimicrobial activity against diarrheal pathogens.

Carissa spinarum, Clutia lanceolata, Cordia Africana, Croton macrostachyus, Cucumis ficifolius, Justicia schimperiana, Rumex nepalensis, Senna didymobotrya, Stephania abyssinica, and Ziziphus spina-christi own terpenoids in their active components. Thus, their antidiarrheal activities may be achieved through the following mechanisms: modulation of intestinal motility, promotion of fluid absorption, exertion of anti-inflammatory effects, antimicrobial activity against diarrheal pathogens, suppression of intestinal secretions, and modulation of gut microflora.

Acacia etbaica, Acacia abyssinica, Anogeissus leiocarpa, Balanites aegyptiaca, Calpurnia aurea, Carissa spinarum, Clutia lanceolata, Cordia Africana, Croton macrostachyus, Cucumis ficifolius, Ficus thonningii, Punica granatum, Senna didymobotrya, Vernonia adoensis, and Withania somnifera contain tannins in their active components. Subsequently, they treat diarrhea by preserving intestinal mucosal integrity. Tannins are known for their astringent properties, which allow them to bind and precipitate proteins. This astringency can potentially result in the reduction of inflammation and mucosal irritation. The astringent properties of tannins have been suggested as a possible mechanism underlying their antidiarrheal effects. By decreasing intestinal secretions and promoting the tightening of the intestinal mucosa, tannins may contribute to the alleviation of diarrhea [105, 121].

Balanites aegyptiaca, Clutia lanceolata, and Stephania abyssinica have coumarins as their active components. Hence, they promote fluid absorption and exert anti-inflammatory effects to halt diarrhea. Germacrene D of Artemisia abyssinica exhibits antimicrobial effects against diarrhea-causing pathogens [109].

The antidiarrheal activity of the chemical components of Aloe spp. includes polysaccharides, glycoproteins, and anthraquinones, exhibits anti-inflammatory effects [122], modulates intestinal motility [123], possesses antimicrobial activity [124], protects the intestinal mucosa [125], and regulates ion transport [126].

Essential oils in medicinal plants exhibit antimicrobial properties, targeting pathogens involved in diarrhea, while their anti-inflammatory effects can reduce gut inflammation. Furthermore, essential oils with antispasmodic activity relax smooth muscles, thereby reducing bowel spasms and the frequency of bowel movements. Some essential oils enhance fluid absorption, resulting in firmer stools and decreased diarrhea. Additionally, essential oils may have a modulating effect on the gut microbiota [127–131].

Coffee is rich in various polyphenols, such as chlorogenic acids and catechins, which possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [69]. These polyphenols demonstrate notable antidiarrheal properties through diverse mechanisms. One significant mechanism involves their antimicrobial activity [132], as well as their anti-inflammatory effects within the gastrointestinal tract, which help attenuate gut inflammation, a contributing factor to the occurrence of diarrhea. Additionally, polyphenols can modulate intestinal motility [133].

Phenols in Croton macrostachyus, Eragrostis tef, Heteromorpha arborescens, and Leonotis ocymifolia possess antimicrobial properties and can alleviate inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract, which is a contributing factor to diarrhea. They also influence intestinal motility, help mitigate toxin-induced diarrhea, and contribute to restoring the balance of fluid and electrolytes by enhancing their absorption [69, 132–135].

Certain steroids, including glucocorticoids in Justicia schimperiana, have been demonstrated to possess anti-inflammatory properties [136]. These properties can be advantageous in the management of conditions associated with diarrhea, such as inflammatory bowel disease. By mitigating inflammation within the gastrointestinal tract, steroids contribute to the modulation of diarrhea symptoms.

Methyl linolenate and methyl linoleate of Linum usitatissimum may exert their antidiarrheal action by reducing inflammation [137] in the gastrointestinal tract. Additionally, they could modulate intestinal motility [138], promoting normal bowel movements and reducing excessive stool frequency. Hydroxycinnamic acids (caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid) in Malva parviflora exhibit pronounced anti-inflammatory properties [139], thereby ameliorating gastrointestinal inflammation commonly associated with diarrhea.

Unsaturated fatty acid methyl esters (methyl-9-octadecenoate, methyl-8,11-octadecadienoate, and methyl-9,12,15-octadecatrienoate) in Momordica foetida Schumach have shown potential anti-inflammatory effects and the ability to modulate inflammatory pathways [140, 141]. These compounds thereby have the potential to ameliorate gastrointestinal inflammation commonly associated with diarrhea. Additionally, they may possess antioxidant properties [142], which can safeguard the gastrointestinal mucosa, mitigate oxidative stress, and modulate immune responses. These combined effects have the potential to contribute to the management of diarrhea.

1,8-cineole, α-pinene, myrtenyl acetate, limonene, linalool, and α-terpinolene represent volatile compounds of Myrtus communis [143]; tricyclene, bornyl acetate, α-pinene, α-terpinene, isoledene, and β-pinene in Ocimum lamiifolium [144]; carvacrol, γ-terpinene, caryophyllene, p-cymene, trans-α-bergamotene, and thymoquinone in Plectranthus lactiflorus [81] demonstrate discernible antimicrobial properties [145–149], effectively impeding the proliferation of diarrhea-causing pathogens.

Hydrolyzable tannins in Punica granatum (punicalin, punicalagin, ellagic acid, and gallic acid) and flavonoids (anthocyanins and catechins) have shown antimicrobial properties, potentially aiding in the elimination of bacteria, viruses, or parasites that can cause diarrhea [150, 151]. Additionally, their anti-inflammatory effects [152–154] may help alleviate inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract, which can be a contributing factor to diarrhea. Furthermore, their antioxidant activity [152, 155] could play a role by protecting the gastrointestinal mucosa from oxidative damage and helping to prevent or manage diarrhea.

Anthraquinones in Rumex nepalensis exert their antidiarrheal effects predominantly through the inhibition of intestinal motility [156], thereby reducing the frequency and intensity of bowel movements associated with diarrhea.

Phytochemicals in Ruta chalepensis such as 2-undecanone, piperonyl piperazine, 2-decalone, 2-dodecanone, decipidone, and 2-tridecanone [85] may exhibit notable antimicrobial properties, thereby exerting inhibitory effects against diarrhea-causing pathogens, encompassing bacteria, viruses, or parasites. Moreover, these compounds could modulate intestinal motility, potentially ameliorating hypermotility and reducing the frequency of bowel movements associated with diarrhea. Additionally, the presence of antispasmodic properties among these compounds might contribute to the attenuation of intestinal spasms, thereby alleviating abdominal cramping and ameliorating diarrhea-related symptoms. Furthermore, their anti-inflammatory properties could potentially play a role in mitigating inflammation within the gastrointestinal tract, consequently aiding in the management of diarrhea. Lastly, the possibility of interference with ion transport in the intestines by these compounds may influence fluid balance regulation, thus affording relief from diarrhea symptoms.

Active components of Salvia nilotica such as β-phellandrene, δ-3-carene, and caryophyllene may exhibit antimicrobial properties [157–159], potentially inhibiting the growth and proliferation of diarrhea-causing pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, or parasites.

Lignin in Solanum nigrum possesses insoluble fiber characteristics, thereby enhancing stool bulk and viscosity, which in turn promotes regular bowel movements and potentially reduces the incidence of loose stools [160]. The increased fecal bulk facilitates the expulsion of toxins and pathogens from the intestines. Moreover, lignin acts as a prebiotic [161], providing nourishment to beneficial gut bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including butyrate. These SCFAs are pivotal in maintaining intestinal integrity and mitigating intestinal inflammation. Furthermore, lignin exhibits antioxidant properties [162], enabling it to scavenge harmful free radicals, potentially ameliorating oxidative stress in the gastrointestinal tract, and safeguarding the integrity of the intestinal mucosa.

Zinc in Sorghum bicolor exhibits diverse mechanisms in its potential antidiarrheal activities. It plays a vital role in preserving the integrity of the intestinal barrier by facilitating the repair of damaged intestinal epithelial cells [163] and reinforcing tight junctions, thus preventing the escape of water and electrolytes into the intestinal lumen and consequently reducing the severity and duration of diarrhea. Additionally, zinc regulates ion transport across the intestinal epithelium, curbing excessive fluid secretion by modulating the activity of specific ion channels and transporters involved in fluid secretion [164]. This restoration of ion transport balance normalizes fluid absorption and diminishes stool volume during diarrhea. Furthermore, zinc exerts immunomodulatory effects which are frequently elevated during diarrheal episodes [92]. Through the mitigation of the inflammatory response [165], zinc contributes to the resolution of diarrhea. Additionally, zinc exhibits direct antimicrobial properties [166], particularly against enteropathogens such as Escherichia coli, rotavirus, and Giardia lamblia, effectively inhibiting their proliferation and growth. Thus, zinc aids in the management of infection and alleviation of diarrhea symptoms.

Caryophyllene oxide in Syzygium guineense exerts potential antidiarrheal activity through various mechanisms. Its anti-inflammatory properties [167] reduce gastrointestinal tract inflammation, thereby alleviating diarrhea symptoms. Caryophyllene oxide also exhibits antimicrobial effects [159] against specific bacteria and parasites, aiding in infection control and diarrhea resolution. Additionally, its antioxidant properties [168] counteract harmful free radicals, mitigating oxidative stress and safeguarding intestinal cells, thus contributing to diarrhea management.

Withanolides in Withania somnifera are recognized for their anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties [169], which have the potential to mitigate inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract and modulate immune responses implicated in the pathogenesis of diarrhea.

5. Conclusion

Many plants from the Amhara region in Ethiopia exhibited potential antidiarrheal activities, which can be attributed to their diverse secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, terpenoids, glycosides, and phenolics. Among the top ten cited plants, Calpurnia aurea contains alkaloids that interact with opioid receptors, reducing bowel movement frequency. Verbena officinalis contains flavonoids that modulate intestinal motility, promote fluid absorption, activate antioxidant pathways, exert anti-inflammatory effects, and exhibit antimicrobial activity against diarrheal pathogens. Coffea arabica is rich in polyphenols (chlorogenic acids and catechins) with antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, which modulate intestinal motility and attenuate gut inflammation. Lepidium sativum contains terpenoids that modulate intestinal motility, promote fluid absorption, exert anti-inflammatory effects, exhibit antimicrobial activity against diarrheal pathogens, suppress intestinal secretions, and modulate gut microflora. Artemisia abyssinica's germacrene D exhibits antimicrobial effects against diarrhea-causing pathogens. Carissa spinarum contains alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, and terpenoids, which may modulate intestinal motility and promote fluid absorption. Leonotis ocymifolia contains terpenoids that modulate intestinal motility, promote fluid absorption, exert anti-inflammatory effects, and possess antimicrobial activity against diarrheal pathogens. Ruta chalepensis contains 2-undecanone, piperonyl piperazine, and other compounds with antimicrobial properties, antispasmodic effects, anti-inflammatory properties, and potential interference with ion transport in the intestines. Verbascum sinaiticum contains flavonoids, saponins, glycosides, and terpenoids, which may modulate intestinal motility, promote fluid absorption, exert anti-inflammatory effects, and exhibit antimicrobial activity against diarrheal pathogens. Withania somnifera's withanolides exhibit anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, mitigating inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract and modulating immune responses involved in diarrhea.

Abbreviations

- CF:

Chloroform fraction

- DALYs:

Disability-adjusted life years

- ME:

Methanol

- MF:

Methanol fraction.

Data Availability

This published article contains all the data that were generated or analyzed during the course of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

DD collected, analyzed, and interpreted data and prepared the manuscript.

References

- 1.Who. Diarrhoea. 2019. https://www.who.int/health-topics/diarrhoea#tab=tab_1 .

- 2.The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Diarrheal diseases—level 3 cause. 2019. https://www.healthdata.org/results/gbd_summaries/2019/diarrheal-diseases-level-3-cause .

- 3.Alebel A., Tesema C., Temesgen B., Gebrie A., Petrucka P., Kibret G. D. Prevalence and determinants of diarrhea among under-five children in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One . 2018;13(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199684.e0199684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dagnew A. B., Tewabe T., Miskir Y., et al. Prevalence of diarrhea and associated factors among under-five children in Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016: a cross-sectional study. Bone Marrow Concentrate Infectious Diseases . 2019;19:417–7. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4030-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tafere Y., Abebe Abate B., Demelash Enyew H., Belete Mekonnen A. Diarrheal diseases in under-five children and associated factors among Farta district rural community, Amhara regional state, north central Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Journal of Environmental and Public Health . 2020;2020:7. doi: 10.1155/2020/6027079.6027079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birhan T. A., Bitew B. D., Dagne H., et al. Prevalence of diarrheal disease and associated factors among under-five children in flood-prone settlements of Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional community-based study. Frontiers in Pediatrics . 2023;11 doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1056129.1056129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shine S., Muhamud S., Adanew S., Demelash A., Abate M. Prevalence and associated factors of diarrhea among under-five children in Debre Berhan town, Ethiopia 2018: a cross sectional study. Bone Marrow Concentrate Infectious Diseases . 2020;20:174–176. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-4905-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Getahun W., Adane M. Prevalence of acute diarrhea and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) associated factors among children under five in Woldia Town, Amhara Region, northeastern Ethiopia. Bone Marrow Concentrate Pediatrics . 2021;21(1):227–315. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02668-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asnakew D. T., Teklu M. G., Woreta S. A. Prevalence of diarrhea among under-five children in health extension model households in Bahir Dar Zuria district, north-western Ethiopia. Edorium Journal of Public Health . 2017;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Getachew A., Tadie A., Hiwot M. G., et al. Environmental factors of diarrhea prevalence among under five children in rural area of North Gondar zone, Ethiopia. The Italian journal of pediatrics . 2018;44(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13052-018-0540-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azage M., Kumie A., Worku A., Bagtzoglou A. C. Childhood diarrhea in high and low hotspot districts of Amhara Region, northwest Ethiopia: a multilevel modeling. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition . 2016;35:13–14. doi: 10.1186/s41043-016-0052-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akram M., Daniyal M., Ali A., et al. Perspective of Recent Advances in Acute Diarrhea . London,UK: Intechopen; 2020. Current knowledge and therapeutic strategies of herbal medicine for acute diarrhea. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubreuil J. D. Antibacterial and antidiarrheal activities of plant products against enterotoxinogenic Escherichia coli. Toxins . 2013;5(11):2009–2041. doi: 10.3390/toxins5112009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Njume C., Goduka N. I. Treatment of diarrhoea in rural African communities: an overview of measures to maximise the medicinal potentials of indigenous plants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2012;9(11):3911–3933. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9113911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fong H. H. Integration of herbal medicine into modern medical practices: issues and prospects. Integrative Cancer Therapies . 2002;1(3):287–293. doi: 10.1177/153473540200100313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark A. M. Natural products as a resource for new drugs. Pharmaceutical Research . 1996;13(8):1133–1144. doi: 10.1023/a:1016091631721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tegen D., Dessie K., Damtie D. Candidate anti-COVID-19 medicinal plants from Ethiopia: a review of plants traditionally used to treat viral diseases. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2021;2021:20. doi: 10.1155/2021/6622410.6622410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giday M., Asfaw Z., Woldu Z., Teklehaymanot T. Medicinal plant knowledge of the Bench ethnic group of Ethiopia: an ethnobotanical investigation. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2009;5(1):34–10. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boadu A. A., Asase A. Documentation of herbal medicines used for the treatment and management of human diseases by some communities in southern Ghana. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2017;2017:12. doi: 10.1155/2017/3043061.3043061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chekole G., Asfaw Z., Kelbessa E. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the environs of Tara-gedam and Amba remnant forests of Libo Kemkem District, northwest Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2015;11:4–38. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-11-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osman A., Sbhatu D. B., Giday M. Medicinal plants used to manage human and livestock ailments in raya kobo district of Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2020;2020:19. doi: 10.1155/2020/1329170.1329170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asfaw A., Lulekal E., Bekele T., Debella A., Abebe A., Degu S. Ethnobotanical Investigation on Medicinal Plants Traditionally Used against Human Ailments in Ensaro District, north Shewa Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia . London, UK: Europe PMC; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mekuanent T., Zebene A., Solomon Z. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Chilga district, Northwestern Ethiopia. Journal of Natural Remedies . 2015;15(2):88–112. doi: 10.18311/jnr/2015/476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haile A. A. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by local people of mojana wadera woreda, north shewa zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Asian Journal of Ethnobiology . 2022;5(1) doi: 10.13057/asianjethnobiol/y050104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazengia E., Beyene T., Tsegay B. A. Diversity of medicinal plants used to treat human ailments in rural Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Archives . 2019;3 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Megersa M., Tamrat N. Medicinal plants used to treat human and livestock ailments in basona werana district, north shewa zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2022;2022:18. doi: 10.1155/2022/5242033.5242033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aragaw T. J., Afework D. T., Getahun K. A. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and utilization of traditional medicine among the communities of Debre Tabor Town, Amhara Regional State, North Central Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2020;2020:10. doi: 10.1155/2020/6565131.6565131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amsalu N., Bezie Y., Fentahun M., Alemayehu A., Amsalu G. Use and conservation of medicinal plants by indigenous people of Gozamin Wereda, East Gojjam Zone of Amhara region, Ethiopia: an ethnobotanical approach. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2018;2018:23. doi: 10.1155/2018/2973513.2973513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mekonnen A. B., Mohammed A. S., Tefera A. K. Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants used to treat human and animal diseases in sedie muja district, south gondar, Ethiopia. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2022;2022:22. doi: 10.1155/2022/7328613.7328613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abeba K. Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants used to treat human and animal diseases in sedie muja woreda, south gondar, Ethiopia. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2022;2022:22. doi: 10.1155/2022/7328613.7328613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yimam M., Yimer S. M., Beressa T. B. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in artuma fursi district, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Tropical Medicine and Health . 2022;50(1):85–23. doi: 10.1186/s41182-022-00438-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nigussie A. An Ethno Botanical Study of Medicinal Plants in Farta Wereda,South Gonder Zone of Amhara Region Ethiopia . Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wubetu M., Abula T., Dejenu G. Ethnopharmacologic survey of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases by traditional medical practitioners in Dega Damot district, Amhara, Northwestern Ethiopia. Bone Marrow Concentrate Research Notes . 2017;10(1):157–213. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2482-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teklehaymanot T., Giday M. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by people in Zegie Peninsula, Northwestern Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine . 2007;3(1):12–11. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enyew A., Asfaw Z., Kelbessa E., Nagappan R. Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants in and around Fiche District, Central Ethiopia. Current Research Journal of Biological Sciences . 2014;6(4):154–167. doi: 10.19026/crjbs.6.5515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gebeyehu G. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University; 2011. An ethnobotanical study of traditional use of medicinal plants and their conservation status in Mecha Wereda, West Gojam Zone of Amhara Region, Ethiopia. MScThesis. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alemayehu G., Asfaw Z., Kelbessa E. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by local communities of minjar-shenkora district, north shewa zone of Amhara region, Ethiopia. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies . 2015;3(6):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alemneh D. Ethnobotanical study of plants used for human ailments in Yilmana densa and Quarit districts of west Gojjam Zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. BioMed Research International . 2021;2021:18. doi: 10.1155/2021/6615666.6615666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birhanu Z. Traditional use of medicinal plants by the ethnic groups of Gondar Zuria District, North-Western Ethiopia. Journal of Natural Remedies . 2013;13:46–53. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Birhanu Z., Endale A., Shewamene Z. An ethnomedicinal investigation of plants used by traditional healers of Gondar town, North-Western Ethiopia. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies . 2015;3(2):36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Umer S., Tekewe A., Kebede N. Antidiarrhoeal and antimicrobial activity of Calpurnia aurea leaf extract. Bone Marrow Concentrate Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2013;13:21–25. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zayede D., Mulaw T., Kahaliw W. Antidiarrheal activity of hydromethanolic root extract and solvent fractions of clutia abyssinica jaub. and spach.(Euphorbiaceae) in mice. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2020;2020:9. doi: 10.1155/2020/5416749.5416749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alemu M. A., Birhanu Wubneh Z., Adugna Ayanaw M. Antidiarrheal effect of 80% methanol extract and fractions of the roasted seed of coffea arabica linn (rubiaceae) in Swiss albino mice. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2022;2022:12. doi: 10.1155/2022/9914936.9914936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asrie A. B., Abdelwuhab M., Shewamene Z., Gelayee D. A., Adinew G. M., Birru E. M. Antidiarrheal activity of methanolic extract of the root bark of Cordia africana. Journal of Experimental Pharmacology . 2016;8:53–59. doi: 10.2147/jep.s116155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Degu A., Engidawork E., Shibeshi W. Evaluation of the anti-diarrheal activity of the leaf extract of Croton macrostachyus Hocsht. ex Del.(Euphorbiaceae) in mice model. Bone Marrow Concentrate Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2016;16:379–411. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1357-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]