Abstract

Transcription of the Escherichia coli genes serA and gltBDF depends on the leucine-responsive regulatory protein, Lrp, and is very much decreased in an lrp mutant. By the use of an Lrp-deficient host and the lrp gene cloned under a plasmid-borne arabinose pBAD promoter, we varied the amount of Lrp present in the cell and showed that both genes were transcribed in proportion to the amount of Lrp synthesized. The affinity of serA for Lrp was four to five times greater than the affinity of gltD. Overproduction of Lrp was lethal to the cell.

The conformation of DNA in the cell results from the interaction of many cytoplasmic factors, including the many DNA-binding proteins which affect its conformation. Some of these, like H-NS and HU, bind with relatively low sequence specificity to many sites and are considered to be structural proteins setting the overall DNA conformation (8). Others, like the lac repressor, bind at one or very few, well-defined sites and are considered to be regulatory proteins. Still others, the global regulatory proteins, bind with high specificity but to many sites, usually regulating expression of a number of genes whose products have a related metabolic function (10).

Leucine-responsive regulatory protein (Lrp), a 19-kDa protein binding cooperatively as a dimer (28), is usually considered to be one of the global regulatory proteins (3, 20, 21). However, it has proved difficult to define a short, clear binding site for Lrp (7). A 15-bp binding sequence has resulted from a Selex search (6), but its biological significance is uncertain, the more so since Lrp protects sites of 80 to 100 bp against DNase I digestion.

Lrp has a strong preference for AT-rich sequences and may even recognize a DNA structure resulting from such sequences. We therefore suggested that Lrp might not be a regulatory protein in the usual sense but might determine DNA conformation. This would be consistent with previous in vitro studies which showed great differences in expression of a variety of seemingly functionally unrelated genes in lrp mutants compared to lrp+ parents.

In this study, we examined the effects of in vivo variation of Lrp concentration and showed that expression of two genes varies with the Lrp concentration, each gene showing its own characteristic affinity. This shows that the expression of various genes can be expected to vary when Lrp concentration varies but does not clearly differentiate between the structural and regulatory roles of Lrp.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plan of experiments.

Expression of chromosomal serA::lacZ and gltD::lacZ fusions was determined by β-galactosidase assay of cells carrying the lrp gene on the arabinose-controlled pBAD22 vector and grown with a variety of arabinose concentrations. The arabinose levels were expressed in Lrp units by comparison with expression of pBAD22lacZ in cells grown in the same circumstances. Host cells carried a Tn10 insertion in lrp and a deletion of the entire ara operon and were thus Lrp deficient and unable to degrade arabinose.

Growth conditions, chemicals, bacterial strains, and plasmids.

The Escherichia coli K-12 strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Minimal medium and growth conditions are as previously described (1, 26). Plasmids were isolated according to Maniatis et al. (18).

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or relevant characteristics | Source or reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| CU1008 | ilvA | L. S. Williams |

| MEW1 | CU1008 Δlac | 14 |

| MEW26 | MEW1 lrp::Tn10 | 14 |

| MEW305 | MEW1 serA::λplacMu | 5 |

| MEW308 | MEW1 Δara714 | 5 |

| MEW309 | MEW26 Δara714 | 5 |

| MEW311 | MEW305 Δara714 | 5 |

| MEW312 | MEW311 lrp::Tn10 | 5 |

| CP8 | MEW1 gltD::lacZ | 15 |

| CP55 | MEW1 leuA::λplacMu | 15, 27 |

| MEW305 | MEW1 serA::lacZ | |

| MEW313 | CP8 lrp:Tn10 Δara | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAD22 | 11 | |

| pBAD18 | 11 | |

| pMEW100 | pBADlrp | 5 |

| pMEW101 | pBAD22lacZ | 5 |

Enzyme assay.

β-Galactosidase activity was assayed in whole cells according to the method of Miller and expressed in Miller units (19).

Construction of arabinose-nonutilizing cells.

Strains were made arabinose deficient in two steps. First a requirement for leucine was transduced to the strain by using phage grown on CP55leu::λplacMu cells (15). Leucine-requiring transductants were then transduced to leucine independence by using phage grown on strain MEW308 (Δara) and screened for the inability to grow with arabinose as a carbon source. This was not straightforward because some stocks of the known Δara strains carry a cryptic mutation resulting in filamentation under some experimental conditions. We therefore first separated the Δara and filamentation mutations, by transducing CP55 to leucine independence and selecting a nonfilamenting Δara strain as donor. We verified that this strain was not inhibited by addition of arabinose to glycerol-grown cultures.

Problems with plasmid maintenance.

The experiments described here were carried out with a variant of pBAD22 carrying the chloramphenicol resistance gene. Analogous experiments, not presented here, with pBAD18 and pBAD22 carrying the β-lactamase gene and with ampicillin to ensure plasmid maintenance were not sufficiently reproducible due to rapid breakdown of ampicillin and loss of plasmid from a large proportion of cells.

Tests of plasmid maintenance.

Approximately 500 cells from several cultures from each experiment were taken at the time of β-galactosidase assay, plated on LB, and replicated on LB and LB with chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml). Experiments presented here showed more than 90% plasmid retention.

RESULTS

Effect of variation in Lrp concentration on expression from serA::lacZ.

Expression of serA is known to be activated by Lrp and decreased in the presence of leucine, so that the SerA activity of an Lrp-deficient mutant is much lower than that of its lrp+ parent. We show here that this is also true for the Δara strains used in this work (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Regulation of expression of chromosomal serA::lacZ and gltD::lacZa

| Strain | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent | lrp mutants | ||

| MEW305 | serA::lacZ | 860 | 220 |

| CP8 | gltD::lacZ | 85 | 15 |

Cells were grown in glycerol minimal medium, subcultured in the same medium, and assayed in mid-exponential phase for β-galactosidase. Values are averages of three determinations.

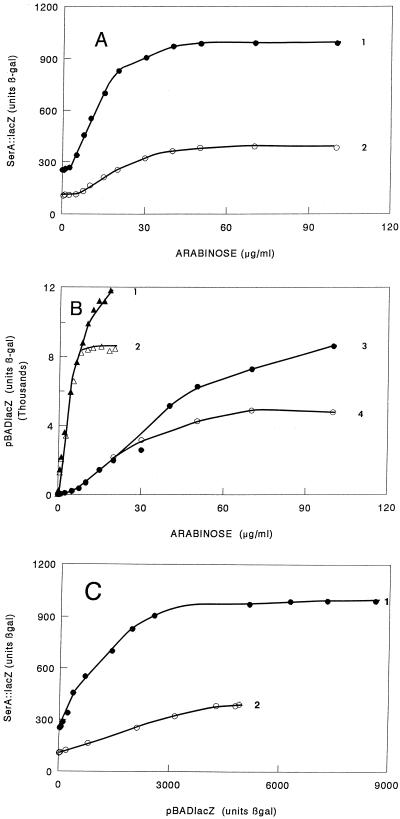

In preliminary experiments, we showed earlier that serA::lacZ expression is proportional to the intracellular Lrp concentration (5). This is examined in much greater detail here, again by using pMEW101, lrp cloned on the pBAD22 vector of Guzman (11). With cells grown in glycerol, β-galactosidase (from serA) was expressed even in the absence of arabinose but increased markedly with arabinose (0 to 30 μg/ml) and was not further increased by arabinose levels up to fourfold higher (Fig. 1A, curve 1). This is consistent with the facts that the lrp mutant is not a serine auxotroph (14) and that the serA gene has two promoters, one of which, P1, is strongly induced by Lrp (16).

FIG. 1.

Influence of Lrp on expression of serA::lacZ. Cells were grown in glycerol minimal medium with the concentrations of arabinose noted and subcultured, and their β-galactosidase activity was assayed in mid-exponential phase. (A) Strain MEW312 (serA::lacZ lrp/pBADlrp) grown with l-serine (•) and with both l-serine and l-leucine (○); (B) strain MEW309 (lrp/pBADlrp::lacZ) grown and assayed as described above in glycerol minimal medium with no addition (▴) and addition of l-leucine (▵), l-serine (•), and l-serine and l-leucine (○). (C) •, data of curve 1 in panel A plotted against data of curve 3 in panel B; ○, data of curve 2 in panel A plotted against data of curve 4 in panel B. For these experiments, l-serine was provided at 500 μg/ml and l-leucine was provided at 200 μg/ml.

We showed that addition of leucine decreased expression at every arabinose concentration from 0 to 100 μg/ml (Fig. 1A, curve 2). This decrease in expression by leucine was seen even in the absence of arabinose, in agreement with the finding that use of serA P2 is decreased by leucine (16).

To express these results as a function of Lrp concentration rather than arabinose concentration, we determined expression of lacZ from pMEW101 (pBAD22lacZ), a construct in which the lacZ gene is fused to the 11th codon of lrp on pBAD22 (5). Cells grown in glycerol minimal medium showed close to 12,000 U of β-galactosidase activity with 10 μg of arabinose/ml (Fig. 1B, curve 1). Addition of l-serine decreased expression from the vector drastically—to 675 U at 10 μg/ml and 7,300 U at 70 μg/ml (Fig. 1B, curve 2). Addition of l-leucine had very little effect at low arabinose concentrations but inhibited strongly at higher arabinose levels (Fig. 1B, curves 3 and 4).

This effect of l-serine on expression from the arabinose promoter is interesting in itself and is so drastic that the curves of Fig. 1A cannot be understood without correction. We therefore replotted the curves of Fig. 1A against the appropriate curves of Fig. 1B and show the results in Fig. 1C. It is clear that serA is induced proportionally with Lrp in a curve that saturates at an Lrp equivalent around 3,000 β-galactosidase units. Leucine inhibited expression at all levels tested—around 50% with no arabinose and over 70% at arabinose concentrations resulting in maximum expression.

Effect of variation in Lrp concentration on expression from gltD::lacZ.

Lrp not only activates transcription of many genes but is indispensable for transcription of several, gcv and gltD included (9, 15), as is confirmed for the strains used here (Table 2). However, nothing is known about the relative sensitivities of Lrp-regulated promoters to Lrp.

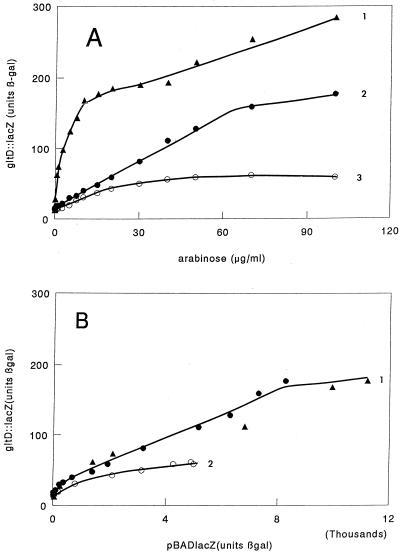

We therefore carried out the same type of experiment as described above on a gene for which Lrp is indispensable, gltD. Expression of chromosomal gltD::lacZ increased similarly in proportion to arabinose from 0 to 20 μg/ml and also, with lower sensitivity, from 40 to 100 μg/ml (Fig. 2A, curve 1). To allow a direct comparison with the results from the serA::lacZ fusion, we repeated this experiment in the presence of l-serine. gltD expression was very much reduced (Fig. 2A, curve 2), as would be expected from the effect of l-serine on the vector. l-Leucine inhibited expression at all arabinose concentrations (Fig. 2A, curve 3).

FIG. 2.

Influence of Lrp on expression of gltD::lacZ. Cells were assayed as for Fig. 1. (A) Strain MEW313 (gltD::lacZ lrp/pBADlrp) grown with l-serine (•), with serine and l-leucine (○), and without addition (▴). (B) Curve 1, data of curves 1 (•) and 3 (▴) in panel A plotted against data of curve 3 in Fig. 1B; curve 2, data of curve 2 in panel A plotted against data of curve 4 in Fig. 1B.

We replotted these curves against the corresponding values for pBADlacZ as was done for the experiments with serA::lacZ (Fig. 2B). It is encouraging that the data for gltD expression with and without l-serine fall on the same curve (Fig. 2B, curve 1) even though some values were obtained from cells grown with l-serine showing much lower expression and some from cells grown in the absence of l-serine.

Leucine has been shown to repress gltD expression in glucose-grown cells (9), an effect which was also demonstrated in in vivo titration studies (2). This was also true in our study, where l-leucine inhibited at all concentrations studied (Fig. 2A, curve B) though relatively little at low arabinose concentrations.

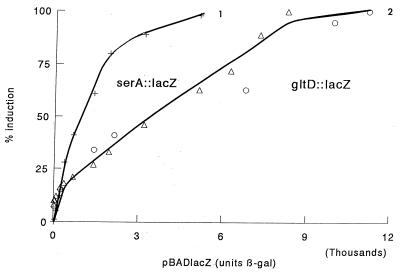

Direct comparison of regulation of serA and gltD.

The maximum expression of serA is much higher (900 U) than that of gltD (150 U) and is reached at a much lower Lrp level. To compare these in what may be a biologically more meaningful way, we expressed the serA::lacZ and gltD::lacZ data as percentages of the maximal induction seen (Fig. 3). This is not completely satisfactory for serA, since the level of expression is a result of increased use of P1 and decreased use of P2. In Fig. 3, curve 1, we plot the data for serA::lacZ with basal activity subtracted. In any case, this figure shows that serA is fully induced at much lower Lrp concentrations than is gltD.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the sensitivities of serA and gltD to Lrp concentration. Data of curve 1 in Fig. 1C and curve 1 in Fig. 2B are plotted as percentages of the maximum value assayed at various pBADlacZ values. Values for serA::lacZ are all plotted with the value at 0 μg of arabinose per ml subtracted.

Toxicity of Lrp to E. coli K-12.

It was reported earlier that Lrp in high concentration inhibits growth of E. coli (2). Taking advantage of the wide range of concentrations available from pBADara, we show that Lrp at high concentration is in fact lethal (Table 3). We grew strain MEW308 (Δara/pBADlrp) in glycerol minimal medium, added arabinose (100 μg/ml), and followed turbidity, viable count, and plasmid retention. The culture increased somewhat in turbidity for about 4 h after arabinose was added. Turbidity remained roughly constant thereafter, but cells died rapidly, as judged by their ability to form colonies on LB. No significant plasmid loss was seen. We have isolated a variety of mutants resistant to Lrp and are currently characterizing them.

TABLE 3.

Toxicity of Lrp to E. coli K-12a

| Time (h) | No arabinose

|

Arabinose

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OD | Colonies (105) on LB | % on LB-CM | OD | Colonies (105) on LB | % on LB-CM | |

| 0 | 0.026 | 14 | 100 | 0.023 | 19 | 95 |

| 2 | 0.028 | 45 | 67 | 0.029 | 31 | 74 |

| 4 | 0.042 | 109 | 91 | 0.037 | 85 | 100 |

| 6 | 0.079 | 137 | 96 | 0.061 | 21 | 48 |

| 8 | 0.136 | 342 | 93 | 0.059 | 10 | 90 |

| 10 | 0.257 | 1,140 | 81 | 0.056 | 8 | 25 |

| 12 | 0.513 | 2,000 | 100 | 0.051 | 4 | 100 |

| 14 | 1.079 | 12,800 | 94 | 0.052 | 2 | 0 |

Strain MEW308 (MEW1 Δara/pBAD22lrp) was grown in glucose minimal medium, subcultured in glycerol minimal medium, and at the start of the experiment (h 0) subcultured with and without arabinose (100 μg/ml) (all in the presence of chloramphenicol [50 μg/ml]). Samples were taken at the times noted, their optical densities were determined at 600 nm, and then they were diluted and plated on LB. LB plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C and then replicated on LB with chloramphenicol (LB-CM).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the effect of changes in Lrp concentration on the expression of gltD and serA, two E. coli genes that require Lrp for transcription. By cloning the lrp gene under the control of the arabinose pBAD promoter, we made Lrp concentration dependent on the quantity of arabinose provided, using lacZ in a pBAD22lacZ fusion as a reporter gene to estimate the amount of Lrp produced.

Physiological implications of relative affinities of serA and gltD promoters for Lrp.

Expression of serA was much more sensitive to Lrp than expression of gltD (Fig. 3). Half-maximal induction of serA was seen at 1,000 U of pBADlacZ compared to the more than 4,000 U needed for the same proportion of gltD expression. This means that at least in glycerol minimal medium in the presence of serine, other factors apart from Lrp being equal, if serA is not turned on, gltD cannot be turned on either. Conversely, if gltD is fully expressed, serA cannot be turned off. It is obvious that both genes respond to Lrp concentration. However, the difference in sensitivity ensures that there is no way of turning on gltD without turning on serA unless another regulatory factor is invoked.

A difference in sensitivity of promoters to a regulator is not unusual, cyclic AMP-cAMP receptor protein complex activating different genes at different concentrations (17). However, Crp regulates genes whose products are used as alternatives to each other; Lrp-regulated genes include many which are used simultaneously. If the sensitivities of other Lrp-regulated promoters also vary, then at different Lrp concentrations, the cell may achieve very different balances in the chemical reactions that it catalyzes. In fact, lrp transcription varies markedly with growth conditions, being decreased in LB and in the presence of amino acids and certain carbon sources and also affected by the ppGpp concentration of the cell (5, 13, 15). Insofar as the Lrp concentration regulates gene expression, one may expect subtle and not so subtle changes as a result of this variation in Lrp concentration.

Activation of serA and gltD.

It is clear that expression of both genes was highly dependent on Lrp and increased smoothly with the arabinose provided, in the range of 0.1 to 20 μg of arabinose/ml, the same range as cited in the original description of this vector (11), with expression saturated at about the same level as in the lrp+ parent but never exceeding that level. This is consistent with a steadily increasing response to increasing levels of activator, with a saturation level determined by intrinsic promoter strength.

Leucine inhibited transcription of serA and gltD in these studies, where lrp is transcribed from the pBAD promoter, as it does in wild-type cells, where it is transcribed from its own promoter. The leucine inhibition at lower arabinose concentrations is consistent with an equilibrium between free Lrp and leucine-bound Lrp, with leucine reducing the amount of Lrp to the same extent at all concentrations and thus reducing the amount of Lrp available for activation. However, if leucine were simply decreasing the available Lrp concentration, then one would expect that expression would increase at higher arabinose concentrations and the curves with and without leucine would eventually meet—which they clearly do not.

In fact, the curves displayed in Fig. 1 and 2 result from the interaction of a variety of factors. At very low arabinose and Lrp levels, only the promoters with the highest affinity would be transcribed. At higher Lrp concentrations, more and more promoters may be affected. On the basis of in vitro experiments, it is generally thought that several dimers (28) of Lrp bind with high cooperativity (16) at Lrp-regulated promoters like ilvIH. However, our in vivo experiments do not show cooperativity, either because they are insufficiently sensitive or because in vivo Lrp may have to compete with several other nonspecific binding proteins.

If cells grown with a high Lrp concentration transcribe some genes that those grown at low concentration do not, they may also contain different compounds, some of which may modulate the effects of leucine, Lrp, or both. If one or more of these affects serA or gltD transcription, or antagonizes lrp action, this may be (part of) the explanation as to why the curves level off as they do.

Comparison with an earlier study on gltD expression.

We have shown that transcription of both genes increased smoothly with the arabinose provided to reach a plateau which varied little as arabinose was increased further. The rise in activity was also seen in an earlier study of gltBDF by Borst et al. using lrp cloned under the control of an isopropylthiogalactopyranoside-inducible promoter, which showed a large decrease in expression at high Lrp concentrations (Fig. 4 in reference 2). This difference may be due to their using an insert of lacZ in gltB whereas we used one in gltD. If there is, as suggested (4), a minor promoter downstream of gltB, and if that promoter was activated at high Lrp concentration, this would explain the difference in results. It is also possible that this discrepancy is due to their use of an ampicillin-selected plasmid. At high Lrp concentrations, growth slows; there is more time for ampicillin to be degraded and plasmid lost, and the apparent GltD activity would be lower in proportion to the number of cells which lost plasmid. This was indeed our experience in preliminary experiments using ampicillin selection, which were not sufficiently reproducible to analyze and showed a wide variation in plasmid retention (data not shown).

Effect of leucine and serine on transcription from the pBAD22 promoter.

The extent of the inhibition of transcription from pBAD by l-serine was a considerable surprise. l-Serine by itself does not serve as carbon source for our strain (22). However, when provided with limiting amounts of glucose, it does support growth (data not shown). Cells provided with both glycerol and serine may derive most of their carbon and energy from serine and thus cause catabolite repression at pBAD. We are currently investigating whether this is the case or whether some explanation based on arabinose uptake or plasmid copy number is more likely.

Lrp toxicity.

We showed that Lrp overproduction not only slows growth as reported earlier (2) but also is actually toxic to the cell. The cells remain viable for several hours after arabinose is added, but most have died by 24 h of incubation. This may be due simply to overproduction of a positively charged DNA-binding protein clogging the works as suggested by Kurland and Dong (12). However, there may also be more specific effects of Lrp overproduction, an area which we are currently investigating.

Potential problems in uneven arabinose uptake.

The analysis in this report depends on the assumption that the internal arabinose concentration is a direct function of the external concentration. Seigele and Hu have suggested that this is not the case (25). They report that in a population of cells grown in their medium, at low arabinose concentrations only some of them express green fluorescent protein cloned under the control of the pBAD promoter. They ascribe this to a differentiation in the population between some cells being fully induced for uptake and some cells not being induced at all.

Were this the case, our data would reflect an increase in the number of cells being turned on at different arabinose concentrations and could not be interpreted as we have done. We suggest a different interpretation based on our finding of the extreme sensitivity of the arabinose promoter to serine. The experiments of Seigele and Hu were done in the presence of a number of amino acids, among them serine at 40 μg/ml. This is a low concentration compared to the 500 μg/ml needed to saturate a culture of a serine-requiring mutant, and even a serine auxotroph degrades serine extensively (24). Because serine is the first amino acid used from a mixture of amino acids (23), we think that serine disappears rapidly in their experiments and that these experiments were done by accident at a critical level of serine which varies just enough from cell to cell so that some cells have enough serine to inhibit the arabinose promoter and some do not. This caveat would apply to any compound which might affect the arabinose promoter or might displace arabinose in the catabolite repression pecking order.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant A6050 from the Canadian National Science and Engineering Research Council, for which we are extremely grateful.

We are grateful for ongoing discussions with R. D’Ari, G. Szamosi, and V. P. Mathur.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambartsoumian G, D’Ari R, Lin R T, Newman E B. Altered amino acid metabolism in lrp mutants of E. coli K-12 and their derivatives. Microbiology. 1994;140:1737–1744. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-7-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borst D W, Blumenthal R M, Matthews R G. Use of an in vivo titration method to study a global regulator: effect of varying Lrp levels on expression of gltBDF in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6904–6912. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6904-6912.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calvo J M, Matthews R G. Leucine-responsive regulatory protein: a global regulator of metabolism in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:466–498. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.466-490.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castano I N, Flores N, Valle F, Covarrubias A A, Bolivar F. gltDF, a member of the gltBDF operon of Escherichia coli, is involved in nitrogen-regulated gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2744–2741. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C F, Lan J, Korovine M K, Shao Z Q, Tao L, Zhang J, Newman E B. Metabolic regulation of lrp gene expression in Escherichia coli K-12. Microbiology. 1997;143:2079–2084. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-6-2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui Y, Wang Q, Stormo G D, Calvo J M. A consensus sequence for binding of Lrp to DNA. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4872–4880. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4872-4880.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Ari R, Lin R T, Newman E B. The leucine-responsive regulatory protein: more than a regulator? Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:260–263. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90177-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drlica K, Rouviere-Yaniv Y. Histone-like proteins of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:301–319. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.3.301-319.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernsting B R, Atkinson M R, Ninfa A J, Matthews R G. Characterization of the regulon controlled by the leucine-responsive regulatory protein in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1109–1118. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1109-1118.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottesman S. Bacterial regulation: global regulatory networks. Annu Rev Genet. 1984;18:415–441. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.18.120184.002215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzman L M, Belin D, Carson M J, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose pBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurland C G, Dong H. Bacterial growth inhibition by overproduction of protein. Mol Microbiology. 1996;21:1–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5901313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landgraf J R, Wu J, Calvo J H. Effects of nutrition and growth rate on Lrp levels in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6930–6936. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6930-6936.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin R T, D’Ari R, Newman E B. The leucine regulon of Escherichia coli: a mutation in rblA alters expression of l-leucine-dependent metabolic operons. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4529–4535. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4529-4535.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin R T, D’Ari R, Newman E B. λplacMu insertions in genes of the leucine regulon: extension of the regulon to genes not regulated by leucine. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1948–1955. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.6.1948-1955.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin R T. Characterization of the leucine/Lrp regulon of E. coli K-12. Ph.D. thesis. Montreal, Canada: Concordia University; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin S, Riggs A D. The general affinity of lac repressor for E. coli DNA: implications for gene regulation in procaryotes and eucaryotes. Cell. 1975;4:107–111. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman E B, D’Ari R, Lin R T. The leucine-Lrp regulon in E. coli: a global response in search of a raison d’etre. Cell. 1992;68:617–619. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90135-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman E B, Lin R T. Leucine-responsive regulatory protein, a global regulator of gene expression in E. coli. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:747–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman E B, Malik N, Walker C. l-Serine degradation in Escherichia coli K-12: directly isolated ssd mutants and their intragenic revertants. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:710–715. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.2.710-715.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pruss B M, Nelms J M, Park C, Wolfe A J. Mutations in NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase of Escherichia coli affect growth on mixed amino acids. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2143–2150. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2143-2150.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramotar D, Newman E B. An estimate of the extent of deamination of L-serine in auxotrophs of Escherichia coli K-12. Can J Microbiol. 1986;32:842–846. doi: 10.1139/m86-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegele D A, Hu J C. Gene expression from plasmids containing the araBAD promoter at subsaturating inducer concentrations represents mixed populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8168–8172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su H, Newman E B. A novel l-serine deaminase activity in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2473–2480. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2473-2480.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tchetina E, Newman E B. Identification of Lrp-regulated genes by inverse PCR and sequencing: regulation of two mal operons in Escherichia coli by leucine-responsive regulatory protein. J Bacteriol. 1994;177:2679–2683. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2679-2683.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q, Calvo J H. Lrp, a global regulatory protein of E. coli binds cooperatively to multiple sites and activates transcription of ilvIH. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:306–318. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]