Abstract

Background:

Virtual reality (VR) simulators are increasingly being used for surgical skills training. It is unclear what skills are best improved via VR, translate to live surgical skills, and influence patient outcomes.

Objective:

To assess surgeons in VR and live surgery using a suturing assessment tool and evaluate the association between technical skills and a clinical outcome.

Design, setting, and participants:

This prospective five-center study enrolled participants who completed VR suturing exercises and provided live surgical video. Graders provided skill assessments using the validated End-To-End Assessment of Suturing Expertise (EASE) suturing evaluation tool.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis:

A hierarchical Poisson model was used to compare skill scores among cohorts and evaluate the association of scores with clinical outcomes. Spearman’s method was used to assess correlation between VR and live skills.

Results and limitations:

Ten novices, ten surgeons with intermediate expertise (median 64 cases, interquartile range [IQR] 6–80), and 26 expert surgeons (median 850 cases, IQR 375–3000) participated in this study. Intermediate and expert surgeons were significantly more likely to have ideal scores in comparison to novices for the subskills needle hold angle, wrist rotation, and wrist rotation needle withdrawal (p < 0.01). For both intermediate and expert surgeons, there was positive correlation between VR and live skills for needle hold angle (p < 0.05). For expert surgeons, there was a positive association between ideal scores for VR needle hold angle and driving smoothness subskills and 3-mo continence recovery (p < 0.05). Limitations include the size of the intermediate surgeon sample and clinical data limited to expert surgeons.

Conclusions:

EASE can be used in VR to identify skills to improve for trainee surgeons. Technical skills that influence postoperative outcomes may be assessable in VR.

Patient summary:

This study provides insights into surgical skills that translate from virtual simulation to live surgery and that have an impact on urinary continence after robot-assisted removal of the prostate. We also highlight the usefulness of virtual reality in surgical education.

Keywords: Robotics, Skills assessment, Surgical training, Virtual reality

1. Introduction

Surgical technical performance is associated with patient outcomes [1,2]. For prostate cancer treatment, evidence suggests that the frequency of surgical complications is higher for robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) cases performed by less experienced surgeons. We previously showed that technical skills are associated with urinary continence recovery after RARP [3,4]. With our understanding of surgeon skill as a predictor of patient outcomes, conventional methods for skills training have been supplemented with high-fidelity models to improve surgical skills to reach a proficiency standard before operation on live patients. This approach may mitigate the risks of training in a high-stakes environment (ie, live surgery) in which there is a potential for worse clinical outcomes for patients.

Virtual reality (VR) has been applied as a training tool to improve proficiency in robotic surgery and can provide an effective alternative to traditional intraoperative learning experiences [5–8]. VR training curricula have been proposed because simulation translates to skill improvements in live surgery [9–11]. Previous studies identified correlation between VR technical skills and live surgical skills but relied on VR scoring metrics provided by the simulator [10,12]. A limitation of those metrics is that they do not always provide targeted feedback for improvement of specific skills; in addition, it is not clear how the scores are generated. Adoption of assessment tools created for live surgery can bridge this gap and provide context for skills assessment in a virtual setting.

There are various tools for assessing robotic surgical skills. Global Evaluative Assessment of Robotic Skills (GEARS) aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of a surgeon’s overall skill level in robotic surgery [13], and Robotic Anastomosis Competency Evaluation (RACE) was designed to evaluate robotic suturing skills during the vesicourethral anastomosis (VUA) step in RARP [14]. Both of these assessment tools have been used to assess surgeon performance in VR [12,15]. To provide trainee surgeons with objective evaluation and feedback for specific robotic suturing skills, we previously developed and validated an assessment tool called End-To-End Assessment of Suturing Expertise (EASE) that breaks down components of robotic suturing and can distinguish the performance of surgeons across varying experience levels [16].

The aims of the present multi-institution study were to evaluate EASE in a VR environment to provide granular technical skills feedback, and to assess correlation between VR performance and live surgical skills. We also assessed the association of specific suturing technical skills with continence recovery after RARP.

2. Materials and methods

We used EASE to evaluate robotic suturing skills in both VR and live surgery. We chose suturing skills because our previous results indicated that surgeon performance assessed during suturing was associated with urinary continence recovery [3,4]. Medical students, residents, fellows, and attending urologic surgeons in this five-center prospective study completed a suturing VR exercise using the Tubes 3 module (Fig. 1) on the Surgical Science Flex VR simulator. Tubes 3 was selected because it evaluates the skills needed to complete the VUA step in RARP [17]. The participants were divided into three groups: novices (no prior robotic cases), intermediate surgeons (<100 robotic cases), and expert surgeons (>100 robotic cases) on the basis of our previous work [18].

Fig. 1 –

Virtual reality exercise using the Tubes 3 module with 16 predetermined targets.

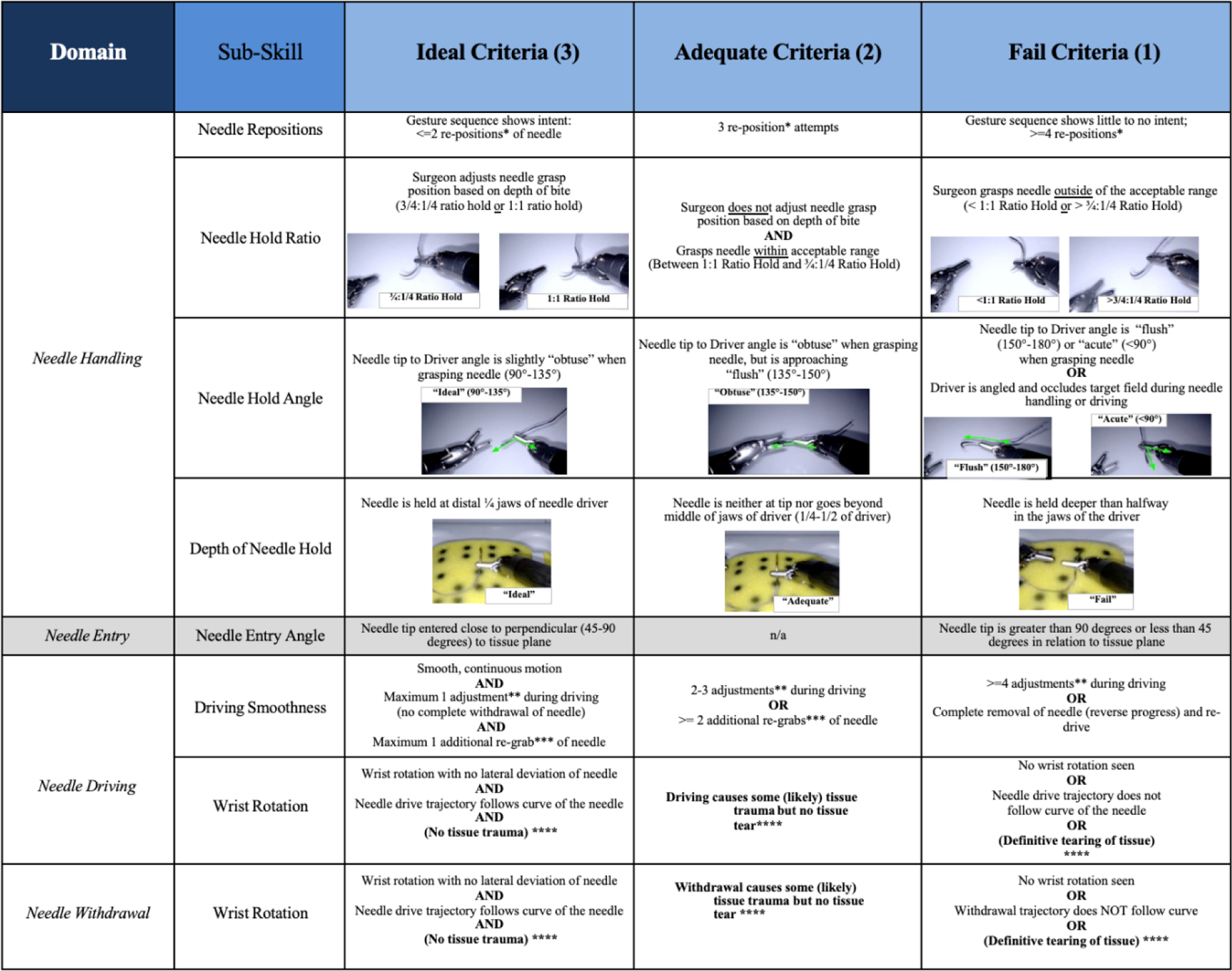

Live surgical videos of intermediate and expert surgeons performing the VUA step of a RARP were also gathered for analysis. EASE, which was originally developed for assessment of live surgical skills, was modified for VR skills assessment. The modified EASE tool is denoted as EASE-VR hereafter (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 –

End-To-End Assessment of Suturing Expertise scoring criteria for virtual reality. Definitions: *Reposition: discrete changing of the needle position with both drivers involved. **Adjustment: when driving the needle and seeing that it will not hit the intended target, without complete withdrawal (some reversal is acceptable) the needle trajectory/exit point is altered. ***Re-grab/grasp: the driver is released and then without moving the needle/suture it is grasped again (usually more distally). ****VR: not applicable in virtual reality.

2.1. Inter-rater reliability

Six independent and blinded raters received standardized training and provided technical skills assessment for VR exercises and live surgical videos using EASE-VR or EASE, respectively. Inter-rater reliability was measured using prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted κ. Raters reached a median agreement rate of 0.74 (interquartile range [IQR] 0.62–0.86) for eight graded subskills before independently assessing exercises.

Clinical data for 3-mo continence recovery after RARP performed by expert surgeons were gathered by the study coordinator at each site. Continence was defined as no pads or 1 safety pad (remains mostly dry) per day.

2.2. Statistical methods

We performed three analyses: (1) whether EASE scores differ across novices, intermediate surgeons, and expert surgeons; (2) whether technical performance in VR correlates with performance in live surgery; and (3) whether technical performance in VR or live surgery is associated with 3-mo continence recovery.

For analysis 1, a hierarchical Poisson model with generalized estimating equations and a natural log link function was used to compare EASE scores in VR for the three surgeon cohorts. A Tukey test was used to correct the multiple comparison error from pairwise comparisons. For analysis 2, each surgeon conducted a suturing exercise in VR and live surgery, without direct matching of VR and live pairs. To examine the correlation between VR and live EASE scores, we calculated the percentage of ideal (3 points), adequate (2 points), and fail (1 point) results among all suturing scores for each surgeon in the VR exercise and live surgery separately and then tested for Spearman correlation. For analysis 3, we used the hierarchical Poisson model with exchangeable working correlation to assess the association between EASE scores and 3-mo continence recovery.

We performed an exploratory subgroup analysis in which “super” expert surgeons with a caseload >2000 (range 2000–5000) were excluded. Thus, the expert surgeons included in this subgroup analysis had a caseload of 100–1000. SAS v9.4 was used for all data analyses.

More detailed information on the materials and methods can be found in the Supplementary material. This study complied with all guidelines set by the University of Southern California institutional review board in relation to obtaining informed consent from human subjects.

3. Results

Ten novices, ten intermediate surgeons (median 64 cases, IQR 6–80), and 26 expert surgeons (median 850 cases, IQR 375–3000) participated in the study (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 –

Cohorts included for each step of the analysis. Analysis 1: all participants performing the VR exercise. Analysis 2: association between VR and live skills performed by intermediate and expert surgeons. Analysis 3: association between live surgical performance and a clinical outcome after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy for expert surgeons. * Clinical outcomes were available for 19/26 of the expert surgeons. EASE = End-To-End Assessment of Suturing Expertise; VR = virtual reality.

When comparing EASE-VR scores among novice, intermediate, and expert surgeons, differences for needle hold angle, wrist rotation, and wrist rotation needle withdrawal were statistically significant (all p < 0.05). When comparing novices to intermediate and expert surgeons, there were significant differences in scores for needle handling subskills (needle hold angle) and needle driving subskills (wrist rotation and wrist rotation needle withdrawal); intermediate and expert surgeons were significantly more likely to have scores of 3 (ideal) in comparison to novices (Tukey test, p < 0.01). When comparing EASE-VR scores between expert and intermediate surgeons, experts were significantly more likely to have scores of 3 (ideal) for the entry angle domain (Tukey test, p = 0.05). There were no significant differences for the other subskills measured (Fig. 4). A more detailed analysis is provided in the Supplementary material.

Fig. 4 –

Comparison of ideal End-To-End Assessment of Suturing Expertise scores for virtual reality subscores for three cohorts. * Statistically significant pairwise difference (Tukey test, p < 0.05) between cohorts.

Within each surgeon cohort, the EASE-VR scores for intermediate and expert surgeons were significantly correlated with their EASE scores for live surgery (p < 0.05). Specifically, there was a positive correlation between VR and live surgery for needle handling (needle hold ratio) for both the intermediate surgeon cohort (r = 0.79, p < 0.01) and the expert surgeon cohort (r = 0.44, p = 0.03). There was a weak negative correlation between VR and live surgical scores for the wrist rotation subskill in the expert surgeon cohort (r = −0.4, p = 0.05). In our study, 282 cases with 3-mo continence recovery data after RARPs performed by 19 expert surgeons across the five institutions were available for analysis (Table 1). We found several associations between VR and live skills and 3-mo urinary continence recovery after RARP. In live surgery, a higher ideal score percentage for subskills for needle handling (needle hold ratio, rate ratio [RR] 1.15, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.04–1.28; p < 0.01) and needle driving (wrist rotation needle withdrawal, RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.02–1.52; p = 0.03) was significantly associated with a higher chance of 3-mo continence. In VR, a higher ideal score percentage for subskills for needle handling (needle hold angle, RR 1.4, 95% CI 1.11–1.76; p < 0.01) and needle driving (driving smoothness, RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.01–1.88; p = 0.04) was significantly associated with a higher chance of 3-mo continence recovery. For select subskills in VR, there was a negative association between ideal scores and 3-mo continence recovery (needle repositions, RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.79–0.93; p < 0.01; wrist rotation needle withdrawal, RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.85–0.91; p < 0.01; Fig. 5).

Table 1 –

Patient characteristics

| Parameter | Achieved continence within 90 d | |

|---|---|---|

| No (n = 180) | Yes (n = 102) | |

| Median age, yr (IQR) | 67 (62–71) | 64 (60–70) |

| ASA score, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 3 (1.67) | 1 (0.99) |

| 2 | 75 (41.67) | 47 (46.53) |

| 3 | 99 (55) | 52 (51.49) |

| 4 | 3 (1.67) | 1 (0.99) |

| Median biopsy GS (IQR) | 7 (7–7) | 7 (6–7) |

| Median BMI, kg/m2 (IQR) | 28.48 (25.55–32.1) | 27.52 (25.82–30.61) |

| Median final GS (IQR) | 7 (7–7) | 7 (7 to 7) |

| pT stage, n (%) | ||

| pT0 | 1 (0.56) | 0 (0) |

| pT2 | 81 (45) | 57 (55.88) |

| pT3 | 96 (53.33) | 45 (44.12) |

| pT4 | 2 (1.11) | 0 (0) |

| Postoperative RT, n (%) | 33 (18.97) | 13 (13.13) |

| Median prePSA, ng/ml (IQR) | 6.95 (5.05–11.52) | 6.33 (4.7–9.8) |

| Median prostate weight, g (IQR) | 48.5 (38–66) | 42.7 (30–58) |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI = body mass index; GS = Gleason score; IQR = interquartile range; prePSA = preoperative prostate-specific antigen; RT = radiation therapy.

Fig. 5. –

Rate ratio (95% confidence interval) for the association of ideal End-To-End Assessment of Suturing Expertise virtual reality scores with 3-mo continence recovery. * Significant association.

In our subgroup analysis for expert surgeons, we found that a higher ideal score percentage in VR for subskills for needle handling (needle repositions, RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.12–2.03; p < 0.01) and needle driving (driving smoothness, RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.01–1.64; p = 0.04) was significantly associated with a higher chance of 3-mo continence recovery, while the other negative association was no longer statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Our study demonstrates meaningful associations between VR skill, live surgical skill, and a primary functional outcome after RARP. First, we showed that EASE can distinguish surgeon skill on a VR platform, supporting the utility of EASE and highlighting the value of VR as a tool for assessment of surgical skills. We also identified correlations for EASE subskill scores between VR and live environments for both intermediate and expert surgeons. Finally, we observed an association between technical performance (in both VR and live environments) and 3-mo continence recovery in the expert surgeon cohort. Previous studies have used more general assessment tools to evaluate surgeon performance in VR and investigate its correlation with live surgical skills and patient outcomes [15,19,20]. Prior research was limited to surgeons from one or two institutions, so our data from five centers (with funding through the National Institutes of Health) greatly enhance the generalizability of our results.

Our group comparison distinguished VR surgical skill levels for three different cohorts. Comparisons in VR revealed subskills (hold angle, wrist rotation, wrist rotation needle withdrawal) for which both expert surgeons and intermediate surgeons exhibited superior performance to their novice counterparts. These subskills should represent educational targets for trainee surgeons. Although there were not many significant VR skill differences between intermediate and expert surgeons, we believe that this can be attributed to the relatively high median caseload among intermediate surgeons (60 cases) being sufficient to match the robotic suturing skills of our defined experts.

Our study also revealed correlations between VR skills and live surgical skills among intermediate and expert surgeons. These cohorts had significant correlations between VR and live skills for needle handling (needle hold ratio), but the association was stronger for intermediate surgeons than for expert surgeons. This finding aligns with our previously published results [15] and suggests a level of cognitive dissonance among experts who are unaccustomed to the VR environment, in which exercises do not perfectly replicate live surgery. Nonetheless, these associations between VR and live skills support the utility of this assessment system in targeting specific surgical skills for improvement in the VR training environment, which may translate to live surgical skills and shorten the learning curve.

Our investigation of the relationship between surgical skill and continence recovery revealed a significant positive association between specific ideal EASE subskills in both VR and live surgery and 3-mo continence recovery. Our previous single-institution study correlated VR needle driving scores with continence recovery following RARP in a smaller surgeon cohort with fewer clinical cases [15]. The present results, with a greater diversity of surgeons from five institutions and hundreds of clinical cases, further support the role of two needle driving subskills in VR (driving smoothness wrist rotation needle withdrawal) in continence recovery. This finding suggests that certain elements of suturing may be useful as measures of surgeon skill, and furthers the generalizability of EASE as an assessment tool. Furthermore, the data indicate that EASE has the potential to identify specific skills for improvement among trainee surgeons and support the validity of a VR training environment for live robotic surgical training. While it is possible that suturing skill alone may not directly impact postoperative urinary continence, these skills might be a robust surrogate measure of overall surgeon performance, which is known to contribute to functional recovery after RARP. Therefore, we are also currently studying other key steps identified that require technical skill, such as the degree of nerve-sparing and apical dissection (urethral length preservation), and their relationship to functional outcomes.

Of note, in our initial analysis there were subskills (repositions and wrist rotation needle withdrawal) that were negatively associated with 3-mo continence recovery. Interestingly, the significant negative associations were no longer evident after removing expert surgeons with the highest caseloads from the analysis. Again, this may point to cognitive dissonance among expert surgeons while operating in VR, resulting in less than optimal VR performance.

As surgical skill is traditionally assessed by human graders, which involves significant time and resources, artificial intelligence (AI) systems are likely to play a key role in surgical training and skill assessment in the future. AI will allow rapid and accurate skill assessment but will only be as accurate as the ground-truth data on which it is trained. Thus, it is critical that AI is trained with the most accurate and objective ground-truth data to objectify surgical performance. While our group has already made significant recent progress in objectively assessing surgical skill via AI systems, much more work remains to be done [21].

Our study is not without limitations. We only evaluated surgical technical skills in VR using a single exercise. This exercise has been established as a valid representation of the VUA step in RARP [17]. Although our sample size for trainee surgeons was limited, the training cohort represents a robust set of trainees from various institutions. Each institution and attending surgeon has different policies for determining when trainee surgeons can perform certain robotic surgical procedures, which makes it challenging to capture a larger standardized cohort. Our clinical outcome analysis was limited to expert surgeons only, without incorporating outcomes that may be attributed to intermediate surgeons. Studying the outcomes of cases performed by intermediate surgeons may be confounded by the fact that they often do not complete entire procedures singlehandedly, thereby introducing attribution bias. Finally, optimal inter-rater reliability should be measured at >0.8, but our lower quartile bound was 0.62, which may have affected the reliability of performance assessment for certain subskills.

In future studies, we hope to study VR exercises that assess other surgical skills to further explore the relationship between transfer of technical skills to live surgery and its effects on clinical outcomes. We also aim to compare EASE as a scoring tool against existing validated instruments for scoring surgical performance [13,14,22] while considering comparisons with scores generated by the VR platform. Another goal is to stratify surgeons by clinical outcomes and compare differences in EASE scores and subskills to further understand the skill-outcome relationship in robotic surgery.

5. Conclusions

Our multi-institutional study provides valuable insights into associations between VR surgical skills, live skills, and functional outcomes after RARP. We demonstrated the utility of EASE in VR as an assessment tool and identified specific subskills that may be important for improvement in trainee surgeons. We also found associations between VR and live surgical technical skills, and continence recovery. Our results further support VR as an effective tool for surgical skills training and assessment. Overall, this study provides valuable evidence supporting continued development and implementation of VR training in surgical education and practice.

Supplementary Material

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor:

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (#R01CA251579). The sponsor played a role in preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosures: Andrew J. Hung certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Andrew J. Hung has financial relationships with Intuitive Surgical. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

This five-institution study provides insights into the relationship between virtual reality (VR) simulation skills and live surgical skills with implications for functional outcomes after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. The results emphasize the potential of VR in surgical education.

References

- 1.Birkmeyer JD, Finks JF, O’Reilly A, et al. Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1434–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stulberg JJ, Huang R, Kreutzer L, et al. Association between surgeon technical skills and patient outcomes. JAMA Surg 2020;155:960–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trinh L, Mingo S, Vanstrum EB, et al. Survival analysis using surgeon skill metrics and patient factors to predict urinary continence recovery after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol Focus 2022;8:623–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hung AJ, Chen J, Ghodoussipour S, et al. A deep-learning model using automated performance metrics and clinical features to predict urinary continence recovery after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. BJU Int 2019;124:487–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hung AJ, Oh PJ, Chen J, et al. Experts vs super-experts: differences in automated performance metrics and clinical outcomes for robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. BJU Int 2019;123:861–8. 10.1111/bju.14599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mao RQ, Lan L, Kay J, et al. Immersive virtual reality for surgical training: a systematic review. J Surg Res 2021;268:40–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma R, Reddy S, Vanstrum EB, Hung AJ. Innovations in urologic surgical training. Curr Urol Rep 2021;22:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larcher A, Turri F, Bianchi L, et al. Virtual reality validation of the ERUS simulation-based training programmes: results from a high-volume training centre for robot-assisted surgery. Eur Urol 2019;75:885–7. 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culligan P, Gurshumov E, Lewis C, et al. Predictive validity of a training protocol using a robotic surgery simulator. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2014;20:48–51. 10.1097/spv.0000000000000045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerull W, Zihni A, Awad M. Operative performance outcomes of a simulator-based robotic surgical skills curriculum. Surg Endosc 2020;34:4543–8. 10.1007/s00464-019-07243-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volpe A, Ahmed K, Dasgupta P, et al. Pilot validation study of the European Association of Urology robotic training curriculum. Eur Urol 2015;68:292–9. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubin AK, Julian D, Tanaka A, Mattingly P, Smith R. A model for predicting the GEARS score from virtual reality surgical simulator metrics. Surg Endosc 2018;32:3576–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goh AC, Goldfarb DW, Sander JC, Miles BJ, Dunkin BJ. Global evaluative assessment of robotic skills: validation of a clinical assessment tool to measure robotic surgical skills. J Urol 2012;187:247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raza SJ, Field E, Jay C, et al. Surgical competency for urethrovesical anastomosis during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: development and validation of the robotic anastomosis competency evaluation. Urology 2015;85:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanford DI, Ma R, Ghoreifi A, et al. Association of suturing technical skill assessment scores between virtual reality simulation and live surgery. J Endourol 2022;36:1388–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haque TF, Hui A, You J, et al. An Assessment Tool to provide targeted feedback to robotic surgical trainees: development and validation of the End-to-End Assessment of Suturing Expertise (EASE). Urol Prac 2022;9:532–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang SG, Cho S, Kang SH, et al. The Tube 3 module designed for practicing vesicourethral anastomosis in a virtual reality robotic simulator: determination of face, content, and construct validity. Urology 2014;84:345–50. 10.1016/j.urology.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hung AJ, Chen J, Jarc A, et al. Development and validation of objective performance metrics for robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: a pilot study. J Urol 2018;199:296–304. 10.1016/j.juro.2017.07.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newcomb LK, Bradley MS, Truong T, et al. Correlation of virtual reality simulation and dry lab robotic technical skills. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2018;25:689–96. 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitehurst SV, Lockrow EG, Lendvay TS, et al. Comparison of two simulation systems to support robotic-assisted surgical training: a pilot study (swine model). J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2015;22:483–8. 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.12.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiyasseh D, Ma R, Haque TF, et al. A vision transformer for decoding surgeon activity from surgical videos. Nat Biomed Eng. In press. 10.1038/s41551-023-01010-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puliatti S, Mazzone E, Amato M, et al. Development and validation of the objective assessment of robotic suturing and knot tying skills for chicken anastomotic model. Surg Endosc 2021;35:4285–94. 10.1007/s00464-020-07918-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.