Abstract

This paper addresses the controversy of Granzyme B (GzmB) expression by murine Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs). MDSCs are a heterogenous immature myeloid population that are generated in chronic inflammatory pathologies for the purpose to suppress inflammatory responses. MDSCs express a multitude of factors to induce suppressive function such as PD-L1, reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and Arginase-1. Recently, Dufait et al. sought to demonstrate GzmB as an additional mechanism for suppression by MDSCs. They reported that murine MDSCs not only significantly express GzmB as well as Perforin (Prf1), but this expression is functionally important for tumor growth in vivo as well as tumor migration in vitro. We conducted experiments to address the same question but made confounding observations: MDSCs under stringent developmental process do not express GzmB. Our results show that not only GzmB protein is not produced at functional level, but the mRNA transcript is not detectable either. In fact, the GzmB protein found in the media of MDSC culture was due to T cells or natural killer cells contained in bone marrow and cultured alongside MDSCs. We strengthen this finding by genetically deleting GzmB from the myeloid lineage and measuring tumor burden compared to WT counterpart. Our results show no significant difference in tumor burden, suggesting that even if there is minor expression of GzmB, it is not produced at a functional amount to affect tumor growth. Therefore, this paper proposes alternative theories that align with the known understanding of GzmB expression and secretion.

Keywords: Granzyme B, Myeloid derived suppressor cells, Immune suppression

Introduction

Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) are a heterogenous population of innate immune cells seen in different pathologies but with the similar function to suppress inflammatory responses [1]. In solid tumors, generation and recruitment of MDSCs to the tumor microenvironment occur at the beginning stages of cancer progression. This recruitment is termed myelopoiesis and can be induced through tumor mediated expression of Granulocyte Macrophage Colony Stimulatory Factor (GMCSF), Macrophage Colony Stimulator factor (M-CSF), IL-6, TLR2 ligands, and more [2–5]. This eventually leads to the generation of aberrant circulating MDSCs which have the ability to create a suppressive niche conducive to metastatic outgrowth and therefore indicates worse prognosis [6]. MDSCs have a variety of ways to induce their suppressive function such as the expression of PD-L1 leading to T cell exhaustion or death, production of ROS to induce dissociation of CD3ε from the TCR, H2O2 mediated loss of zeta chain, NO mediated IL-2R signaling inhibition, as well as the depletion of vital T cell nutrients such as arginine by using Arginase-1 to inhibit T cell activation [7–10].

Recent reports have shown that MDSCs also use another mechanism for T cell suppression: the expression of Granzyme B (GzmB) and Perforin (Prf1). One such circumstance is in relation to Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). MDSCs collected from the blood of patient’s diagnosed with MDS and incubated with erythroid precursors resulted in GzmB production by MDSCs and targeted apoptosis of these precursors [11]. Another pathology that mimics this finding is atherosclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Analyzing human atherosclerotic plaques and synovial tissues of rheumatoid arthritic joints, it was shown that CD68 positive macrophages expressed GzmB using immunohistochemistry analyses and in situ hybridization. They also demonstrated that the macrophage cell line, THP-1 can be induced to express GzmB [12]. These results coincide with data proposing that human GzmB is not only present in mature polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) but also in myeloid cell lines such as HL-60 and U937, CD34 + stem cells and PMNs derived from CD34 + cells in vitro [13]. Another discovery was human plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) that express GzmB following IL-3 stimulation [14]. This stimulation through the IL-3 receptor complex is JAK1-STAT3/5 dependent. What they also find is that IL-10 stimulation following IL-3 increases the population of GzmB producing pDCs while TLR7/9 and CD40 stimulation decreases this effect. As IL-10 utilizes the JAK1-STAT3/5 pathway, it does not seem to be redundant as IL-3 prior to stimulation is required to enhance GzmB production [14, 15]. Although the cell types studied are functionally and phenotypically different from MDSCs, this allows for valid speculation in studying MDSCs in the murine model.

In this context, a recent report shows that MDSCs isolated from melanoma-bearing mice in addition to bone marrow derived MDSC (BM-MDSC)-like cells express GzmB and Prf1 and use this pathway to promote tumor growth and invasion [16]. Although the expression of GzmB in this heterogenous myeloid population would grant breakthroughs in research, the stringency of research to prove these statements are of utmost importance. Therefore, in this paper, we described our attempt to validate the expression and function of GzmB in MDSCs. We demonstrate that in vitro BM-MDSCs and in vivo MDSCs do not produce GzmB protein or its mRNA transcript. More notably, genetic deletion of GzmB from the myeloid lineage does not affect tumor growth suggesting that GzmB is not a protumoral mechanism derived by murine MDSCs. This work also discusses the alternative implications of MDSCs that seemingly express GzmB.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and mice

B16-F10-GMCSF cells were a gift from Eduardo Davila which were gifted from Elizabeth Jaffee [17, 18]. Tumor cells were cultured as previously described [19]. B16-F0 and 4T1 cells were obtained from ATCC. GzmB knock out mice (GzmBko) were generated as described [20]. GzmBko mice were maintained in C57BL/6 J mice strain. GzmBfl/fl mice were generated from Cyagen Biosciences Inc (Santa Clara, CA) and maintained in C57BL/6 J mice strain. GzmBfl/fl mice were crossed with Lyz2cre transgenic mice to obtain Lyz2creGzmBfl/fl mice with myeloid cell-specific deletion of GzmB. All mice were maintained in specific pathogen–free housing, and all experiments were conducted in accordance with the animal care guidelines from the Office of Animal Welfare Assurance at the University of Maryland School of Medicine Veterinary Resources using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In vitro generation of myeloid derived suppressor cells

Conditioned media (CM) was harvested from B16-F10-GMCSF, B16-F0, or 4T1 cells, centrifuged for 5 min at 1500 rpm and filtered with 0.2-micron strainer and used to differentiate bone marrow cells into MDSCs. Briefly, 10 × 106 bone marrow cells were cultured for 6 days in 75% CM and 25% Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100 units Penicillin/100 ng Streptomycin/mL (Sigma), and 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma) in non-TC-treated petri dish plates (CELLTREAT, 229,693). B16-F0 MDSCs were cultured in 15 ng/mL murine that GMCSF (Biolegend, 713,704) Cells were then harvested for flow cytometry or RNA extraction. Supernatant was used for ELISA as described below.

In vitro T cell assay

Spleens were harvested from WT and GzmBko mice and processed to single cell suspension. CD4 + and CD8 + T cells (purity > 95%) were purified from the spleens by using Pan-T isolation Kit II, mouse (Miltenyi Biotec). 1 × 106 cells were cultured on αCD3-αCD28 coated plate for 48 h in T cell media (TCM) (RPMI-1640, 10% FBS, 100 units Penicillin/100 ng Streptomycin/mL (Sigma), 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.05 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol) Cells were washed with fresh TCM and split 1:1 and plated on fresh non-coated plate for 3 days, with media being replaced after two days. On the 5th day, cells were again split 1:1 and plated on newly coated αCD3-αCD28 plate. Cells were then harvested for flow cytometry or RNA extraction. Supernatant was used for ELISA as described below.

For T cell suppression assays, T cells were labeled with 0.3 mM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Invitrogen, C34554), incubated in 37 °C incubator for 10 min, quenched with 30 mL of cold TCM and further incubated for 5 min on ice. The assays were setup by adding a variable number of CD11b-sorted MDSCs (5 × 104–2.5 × 105;1:1–1:5) to a constant 5 × 104 T cells on αCD3-αCD28 coated black plates for 72 h. Then cells were harvested for flow cytometry.

In vivo tumor growth

To determine growth kinetics and obtain tumors for MDSC characterization, 2 × 105 tumor cells were injected subcutaneously at the right flank of WT or Lyz2creGzmBfl/fl mice. Tumor growth was measured daily using an automated caliper. Tumors were allowed to grow to 4200mm3 or 20 mm in any dimension for survival studies. Upon endpoint, mice were euthanized, and lungs were harvested to measure metastasis. Tumors of 600 + / − tc100 mm3 were isolated and reduced to single cell suspensions using enzymatic digestion as described. [21] Resected tumors were separated for RNA extraction and flow cytometry. MDSCs present in these cell suspensions were characterized by flow cytometry.

ELISA

Following culture conditions as described above, supernatants of BMD-MDSC cell culture (100µL) and activated T cells (1µL in 99µL reagent diluent) were collected, and the production of GzmB was quantified using a Granzyme B kit (Duoset) (R&D systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance at 450 nm was analyzed using a microplate ELISA reader (Synergy HTX).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Tumors were disrupted using enzymatic digestion as described above. Splenic MDSCs were disrupted and brought to single cell suspension as described above. Splenic and tumor infiltrating MDSCs were sorted using EasySep Mouse CD11b Positive Selection Kit II (Stem Cell Technologies) to allow for most pure population to measure GzmB transcripts. RNA from CD11b + cells from splenic and tumor infiltrating MDSCs, as well as BMD-MDSC and activated T cells were extracted using RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen), according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was reversely transcribed using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa). cDNA was then used as template in the quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). Primers specific for mouse Actin-B (ActB), Granzyme B (GzmB), Arginase-1 (Arg-1), inducible Nitric Oxide (iNOS) were used, and relative gene expression was determined using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The comparative threshold cycle method was used to calculate gene expression normalized to ActB as a reference gene.

Flow cytometry

Antibodies, including anti-mouse CD11b (M1/70, 101,257/101208), GR-1 (RB6-8C5, 108,412/108441), CD3 (145-2C11, 100,218), TCRβ (H57-597, 109,243), GzmB (GB11, 515,408), CD4 (RM4-5, 563,727), CD8 (53–6.7, 100,734, 100,747), iNOS (CXNFT, 12,592,082), Arg-1 (A1exF5, 12,369,782), TGFβ (TW7-16B4, 141,413), IFNγ (XMG1.2, 562,020) were ordered from BioLegend or BD Biosciences and used for spectral flow cytometry. Briefly, cells were washed using flow buffer (PBS with 2% FBS), and Fc receptors were blocked with the addition of unlabeled anti-CD16/CD32 (BD Biosciences, 553,142) for 20 min in 4 °C. Extracellular markers and fixable LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua (Invitrogen, L34966A) were stained together in PBS for 40 min in 4 °C and washed two times with flow buffer. Intracellular stains were performed using the eBioscience FoxP3/Transcription factor staining buffer set (Invitrogen, 00,552,100). Cells were fixed overnight in 4 °C using the intracellular fixation buffer. Cells were resuspended in 1 × permeabilization buffer and incubated for 5 min. Cells were washed using 1 × permeabilization buffer, and potential intracellular Fc receptors were blocked with the addition of unlabeled anti-CD16/CD32 for 10 min in 4 °C. Samples were split, and test Abs or isotype control Abs were added and incubated for 1 h in 4 °C and washed twice in 1 × permeabilization buffer before resuspending in flow buffer. Samples were run on the Aurora spectral flow cytometer (Cytek Biosciences) in the Center for Innovative Biomedical Resources at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Unmixed samples were analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo). Background staining was assessed with unstained controls, stained isotype controls, and experimental negative controls when possible.

Results

MDSCs do not express GzmB as an intracellular protein

We generated MDSCs phenotypically similar to those found in tumor bearing mice in vivo by culturing bone marrow cells in tumor conditioned media (CM) of B16-F10 cells that have been retrovirally altered to secrete high levels of GMCSF. Following culture conditions, we collected cells and performed flow cytometry to assess surface markers as well as intracellular markers. These BMD-MDSCs are not only phenotypically similar but also express suppressive markers consistent to previously published data such as TGFβ and Arg-1 (Fig. 1a, b) and are able to suppress T cell proliferation and activation (Fig. 1c, d). However, among the many molecules being expressed, GzmB was not one of them (Fig. 1b). As proper controls, we included not only BMD-MDSCs from GzmBko mice but also CD8+ T cells that have been activated and cultured from the same mice (Fig. 2a). The WT CD8+ T cells showed a range of GzmB being produced while GzmBko CD8+ T cells showed no GzmB expression. We tested these findings on two additional cell lines, B16-F0 supplemented with murine GMCSF and 4T1. Both models generated MDSCs but did not show GzmB expression (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, to ensure the lack of GzmB expression by BMD-MDSCs was not due to the methods of generation, we studied MDSCs isolated from the tumor and spleen of mice bearing B16-GMCSF melanoma and the spleen of mice bearing 4T1 breast cancer. The flow cytometry analysis shows that tumor infiltrating and splenic MDSCs did not express GzmB (Fig. 2a).

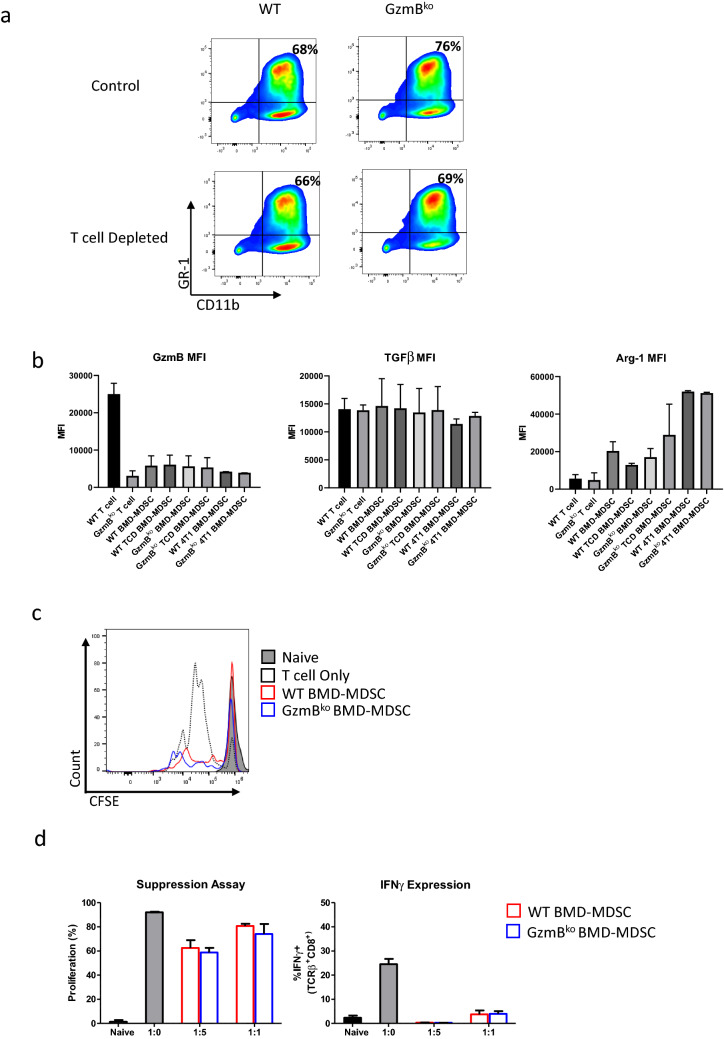

Fig. 1.

Murine BMD-MDSCs suppress T cells in vitro in a GzmB-independent fashion. a Representative plots showing important surface markers for cell subset selection. BMD-MDSCs were generated by bone marrow cells in B16-GMCSF conditioned media for 6 days. T cells and NK cells were depleted and labeled TCD. Depleting T cells and NK cells from BMD-MDSC culture does not significantly alter MDSC phenotype. b Representative graphs showing the Mean Fluorescence Intensity of labeled Flow Cytometry markers. c Representative plot showing suppression of T cell proliferation. d Representative graphs showing suppression of T cell proliferation or activation gated on CD8 T cells. T cells were labeled with CFSE, activated using αCD3-CD28, and cultured with or without indicated BMD-MDSCs

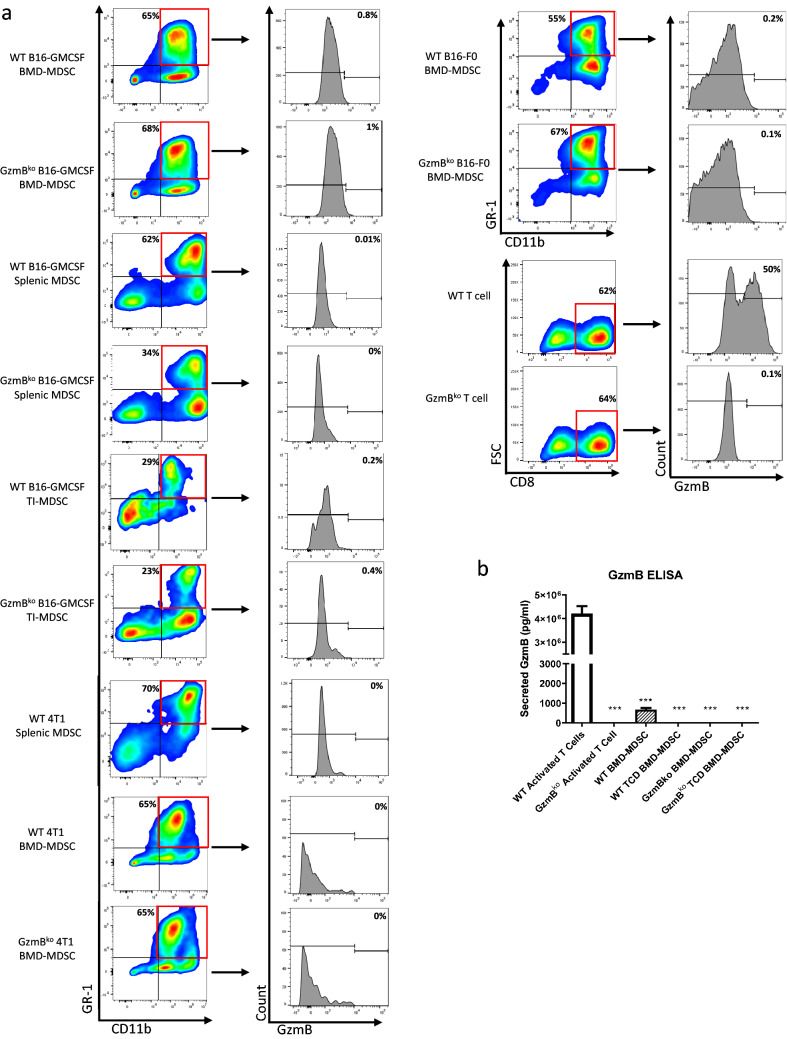

Fig. 2.

GzmB protein is not expressed in murine MDSCs in vivo or in vitro. a Representative plots showing important surface markers for cell subset selection. Representative histogram plot of GzmB expression. b Representative plot showing the concentration of secreted GzmB in the supernatant of indicated culture system. The graph shows the mean ± SEM of at least three data points. Experiments were performed twice. A student’s t-test was used to calculate the statistics. BMD-MDSCs were generated by bone marrow cells cultured in B16-GMCSF, B16-F0 supplemented with murine GMCSF, or 4T1 conditioned media for 6 days. Splenic and Tumor Infiltrating (TI) MDSCs were generated by euthanizing representative B16-GMCSF or 4T1 tumor bearing mice that have reached endpoint. TI-MDSCs were collected by percoll gradient selection followed by CD11b + sorting. T cells were generated by sorting for Pan-T cells from naïve mice and activating via αCD3-CD28 stimulation for 6 days

GzmB released in culture media originates from T cell and NK cells

Due to the lack of expression of GzmB intracellularly, we wanted to investigate if GzmB was already being released by the BMD-MDSCs prior to our flow cytometric analysis. We used the media of the BMD-MDSC culture and conducted an ELISA to measure the amount of GzmB in the media. As proper controls, we included the media from the WT and GzmBko CD8+ T cell culture. We found a significant amount of GzmB in the media of WT CD8+ T cells, however the amount of GzmB found in WT BMD-MDSCs were detectable but at very low levels compared to the T cells (Fig. 2b). This is understandable due to the profile of the cell types. As they are not classical GzmB producing cell types, we can assume that if GzmB is being produced, it would be at a fraction of the expression compared to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). However, we were concerned with the possibility of CTL or NK cells from the BM producing and releasing small amounts of GzmB during the BMD-MDSC culture. The small population of lymphocytes still present could lead to the release of GzmB in the media. To address this, we depleted T cells and NK cells prior to the BMD-MDSC culture conditions. We found that depleting T cells and NK cells resulted in undetectable amount GzmB in the media (Fig. 2b). The phenotype of the MDSCs were not altered following T cell depletion. (Fig. 1a).

MDSCs do not express GzmB transcript

In the hope to reproduce the work done by Dufait et al., we were puzzled that we could not detect GzmB protein within these MDSCs in vivo or in vitro [16]. Due to the highly regulated nature of GzmB, we assumed that maybe the protein has not been made but the mRNA transcript has. We conducted qPCR on CD11b sorted cells following in vitro MDSC generation and measured GzmB expression as well as other known mechanisms utilized by MDSCs. We found that the GzmB mRNA transcript expression of MDSCs was similar to that of GzmBko T cell expression; virtually non-detectable (Fig. 3). We were curious of the cell types generated from our MDSC culture. Although the phenotype is consistent to published data, it is crucial to measure the functional mechanisms that would delineate MDSCs from non-suppressive neutrophils and monocytes. We found Arg-1 mRNA transcripts to be highly upregulated (Fig. 3), indicating that the generated MDSCs are consistent to the previous data supporting suppressive mechanisms of MDSCs.

Fig. 3.

BMD-MDSC and Ex-vivo MDSCs do not express GzmB mRNA transcript. Summarizing graph showing fold change, as measured by quantitative PCR of GzmB, Arg-1, and iNOS of cultured cells and ex-vivo MDSCs from WT or GzmBko mice. The fold change for GzmB is normalized to activated GzmBko T cells. The fold change for Arg-1 and iNOS were normalized to activated WT T cells. The graph shows the mean ± SEM of at least three data points. Experiments were performed twice. A student’s t-test was used to calculate the statistics. BMD-MDSCs were generated by culturing bone marrow cells in B16-GMCSF conditioned media for 6 days. TCD indicates T cell and NK cell depleted bone marrow that was then cultured in tumor conditioned media. T cells were generated by sorting for Pan-T cells from naïve mice and activating via αCD3-CD28 stimulation for 6 days

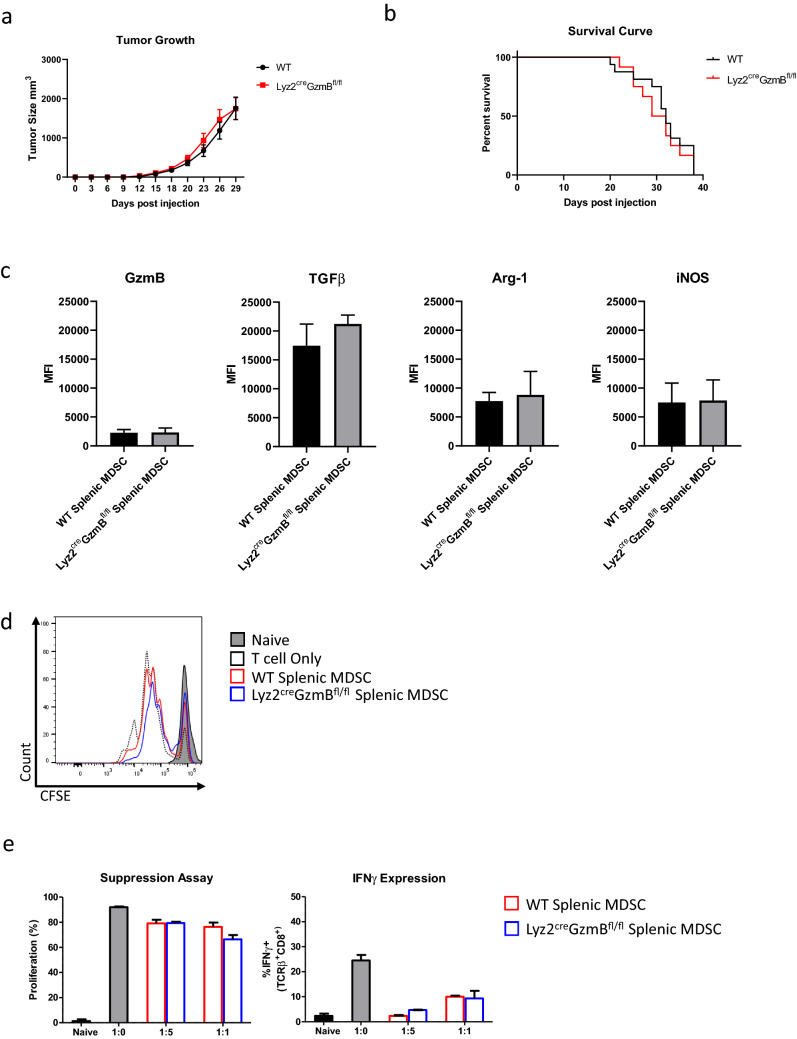

Myeloid specific deletion of GzmB does not impact tumor growth and metastasis

Lastly, we wanted to determine where genetic deletion of GzmB in MDSCs has any impact on tumor growth and antitumor immune response. We generated Lyz2creGzmBfl/fl mice which would specifically delete the GzmB gene from the Myeloid lineage (Fig. 4a, b). This does not alter the expression of GzmB in T cells in the same mice (Fig. 4c). We then injected B16-GMCSF cells into WT or Lyz2creGzmBfl/fl mice and measured the tumor growth as well as potential metastasis to the lungs. We found that there was no difference in tumor burden and survival between these two groups (Fig. 5a, b), while MDSCs harvested from the spleens of these tumor bearing mice express other markers such as TGFβ, Arg-1, and iNOS (Fig. 5c) and were able to inhibit T cell activation (Fig. 5d, e). With these results, we can assume one of two scenarios: murine MDSCs do not produce GzmB under any scenario, or if they do GzmB is not produced or secreted at a functional amount that would affect the growth of tumors.

Fig. 4.

Generation of Lyz2-Cre X GzmBflox mice and confirmation of specificity of Cre-LoxP system. a Schematic of mouse lines used to characterize the expression pattern. Lyz2-Cre driver line was crossed with GzmBflox/flox. In the presence of Cre recombinase, GzmB will be deleted. b A Lyz2 PCR yields a 700-bp for the cre recombinase allele (top). A 307-bp for the GzmB LoxP allele and 194-bp for WT lacking LoxP allele (middle). When the constitutive LoxP allele has been deleted PCR will yield a 338-bp allele. (bottom). c Representative flow cytometry plots showing GzmB expression is not altered in T cells following GzmB deletion from the myeloid lineage. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with IL-2 complex for 3 consecutive days. 5 days following first injection, mice spleens were harvested and stained for flow cytometry. Plots shown were gated on live single cells. d Representative flow cytometry plots showing no difference in GzmB expression in CD11b + GR-1 + cells in WT and Lyz2creGzmBfl/fl mice. Cells were collected following B16-GMCSF experimental endpoint

Fig. 5.

Myeloid cell-specific deletion of GzmB does not affect tumor growth in vivo. a Representative tumor growth curve of mice inoculated with B16-GMCSF as measured by caliper. The graph was shown until day 29. The mean ± SEM of at least 10 data points is shown. All experiments were repeated at least once. b Representative survival curve of mice inoculated with B16-GMCSF. Mice were either found succumb to tumor or sacrificed upon tumor size endpoint as established through IACUC protocol. n = 12–16 mice for each group pooled from 2 independent experiments. c Representative graphs showing the Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of labeled Flow Cytometry markers. d Representative plot showing suppression of T cell proliferation. e Representative graphs showing suppression of T cell proliferation or activation gated on CD8 T cells. Splenic MDSCs were harvested from sacrificed mice upon tumor size endpoint. T cells were labeled with CFSE, activated using αCD3-CD28, and cultured with or without indicated splenic MDSCs

Discussion

The results we acquired were at first glance obviously alarming due to the published data showing significant expression of GzmB by murine MDSCs [16]. However upon rigorous analysis, our data consistently show that neither GzmB protein nor mRNA transcript is detectable in the models classically known to produce highly suppressive MDSCs. In addition, our in vivo analysis to decipher the function of GzmB producing MDSCs using the cleanest possible model confirms that there is no functional expression due to no difference in tumor growth or survival in wild-type vs. myeloid specific GzmB deleted mice. Therefore, we conclude that murine MDSCs do not express functional levels of GzmB as an additional suppressive mechanism.

In our analysis, we determined that the details for the expression as well as the release of GzmB by this immature cell population need to be addressed. In the report by Dufait et al., in which they showed GzmB in MDSCs, the MDSCs that expressed GzmB were not given any additional stimulation other than the culture conditions used to generate the heterogenous cell population: conditioned media from Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor (GMCSF) producing tumor cells. This can also be interpreted as that MDSCs can express GzmB ubiquitously as long they are in their immature state. This would be groundbreaking because it is the first cell type that does not need a first or second activation signal for producing and secreting a cytotoxic molecule such as GzmB. GMCSF binding to its receptor allows for utilizing JAK2/STAT3/5 pathway, different from the signaling pathways that allow for GzmB production by CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells [22–25]. Under tumor conditions, IL-6 will also be secreted in the environment which would signal through STAT3/5 [22]. However, this signaling pathway for GzmB production by MDSCs has not been validated.

Although there has been recent research into understanding extracellular roles of GzmB in the microenvironment, the finding of Prf1 in addition to GzmB allows us to surmise an intracellular killing mechanism by MDSCs [26–28]. The combination of Prf1 with GzmB allows for a cascade of events, ultimately leading to apoptosis of the targeted cell. Classically, this mechanism has been described by Prf1 oligomerizing to create a pore which allows GzmB to translocate into the cytoplasm of the targeted cell. [29] Once in the cytoplasm, GzmB cleaves multiple downstream substrates such as caspase-3, -8, -6, and -7 [30–33]. Recent examples that we can use to compare to MDSC expressing GzmB and Prf1 is the finding of GzmB and Prf1 being important for Tregs ability to kill target cells under experimental conditions [34–37]. Generally, cells that express these molecules simultaneously are thought to act as a cell killer.

One figure published by Dufait et al. that we found particularly alarming was Fig. 4 [16]. This figure showed that while co-injection of WT MDSC with tumor cells greatly promoted tumor growth, co-injection of GzmB-Prf1 KO MDSC had no effect on tumor growth. This result suggests that the GzmB-Prf1 pathway alone accounts for all the tumor-promoting activity of MDSC, or that the other immune suppressive mechanisms of MDSC rely on GzmB and Prf1. This is highly unlikely as those mechanisms are known to function separately and independent of GzmB or Prf1.

A hypothesis that we propose is that GzmB secreted by CTLs or NK cells can be taken up by MDSCs, creating a false positive expression of GzmB in MDSCs. This can also explain the non-gradient expression of GzmB by MDSCs that the results of Dufait et al. show. The expression of GzmB by CD8+ T cells does not represent a singular peak but a gradient of expression [37, 38]. Although expression would not be as intense as CTLs, the expression pattern of GzmB by MDSCs should present as a gradient, especially if this is a rare occurrence. As with many cell types that express functional proteins, results will show both a negative and positive population. Results showing solely positive expression without a prominent negative population should raise eyebrows and be stringently analyzed.

In addition to focusing on the discovery of GzmB in these cell types, an important step is to establish transcription factors that are indicative of the expression of GzmB by non-lymphocytes. At this time, MDSCs do not express Tbx21 (T-Bet), which has been known to control the expression of GzmB by the classical GzmB producing cells [39]. Due to its regulation, determining the co-expression of known or novel transcription factors in non-lymphoid GzmB producing cells can be a daunting, yet necessary task to progress the study of this cytotoxic molecule.

Our results do not discredit the findings of GzmB expression in human MDSCs or myeloid cells. The complexity between human and murine species is broad. However from prior studies, we can surmise that the mechanisms that regulate GzmB expression are not conserved between human and mice. This can be correlated to the findings of GzmB being found in human B cells upon IL-21 stimulation but not in murine B cells [40]. There are inherent differences in the functions of the various paralogues of human GzmB that may be split into different Gzms in mice instead of just GzmB. For example, GzmB is found in human testis while GzmN, not GzmB, is found in the testis of mice [41, 42]. We believe that GzmB expression in human studies should still be rigorous and precise in their methods and analysis and also include upstream signaling mechanistic studies.

We reason that the findings reflecting the expression of GzmB by cells in the myeloid lineage can be explained by confounding factors such as engulfment or trafficking from activated lymphocytic cell populations.

Further studies are required to define whether MDSCs can actually uptake GzmB and use it to impact inflammation and tumor immunity. We expect new models to be developed that can delineate how GzmB can be transferred into MDSCs, which will contribute to better understanding of novel roles of GzmB as well as possible receptors that bind on the cellular surface. These other pathological findings would help propel our understanding of unknown roles that GzmB may play in relation to cancer and inflammation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nicholas Ciavattone for technical assistance. This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA184728), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (T32AI095190), the Maryland Department of Health's Cigarette Restitution Fund Program and used shared core facilities supported by University of Maryland Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center (UMGCC) Support Grant (P30CA134274).

Author contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bronte V et al (2016) Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat Commun 7(1), Art. 1. 10.1038/ncomms12150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Chalmin F, et al. Membrane-associated Hsp72 from tumor-derived exosomes mediates STAT3-dependent immunosuppressive function of mouse and human myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(2):457–471. doi: 10.1172/JCI40483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lechner MG, Liebertz DJ, Epstein AL. Characterization of cytokine-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells from normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Immunol. 2010;185(4):2273–2284. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiang X, et al. TLR2-mediated expansion of MDSCs is dependent on the source of tumor exosomes. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(4):1606–1610. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Z, et al. Development and function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells generated from mouse embryonic and hematopoietic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28(3):620–632. doi: 10.1002/stem.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Aburatani H, Maru Y (2006) Tumour-mediated upregulation of chemoattractants and recruitment of myeloid cells predetermines lung metastasis Nat Cell Biol 8(12):1369. 10.1038/ncb1507 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Nagaraj S, Gabrilovich DI (2010) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in human cancer. Cancer J 16(4):348. 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181eb3358 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Noman MZ, et al. PD-L1 is a novel direct target of HIF-1α, and its blockade under hypoxia enhanced MDSC-mediated T cell activation. J Exp Med. 2014;211(5):781–790. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao Y, Feng Y, Zhang Y, Zhu X, Jin F. L-Arginine supplementation inhibits the growth of breast cancer by enhancing innate and adaptive immune responses mediated by suppression of MDSCs in vivo. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:343. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2376-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bian Z, et al. Arginase-1 is neither constitutively expressed in nor required for myeloid-derived suppressor cell-mediated inhibition of T-cell proliferation. Eur J Immunol. 2018;48(6):1046–1058. doi: 10.1002/eji.201747355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, et al. Induction of myelodysplasia by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(11):4595–4611. doi: 10.1172/JCI67580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim W-J, Kim H, Suk K, Lee W-H. Macrophages express granzyme B in the lesion areas of atherosclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Lett. 2007;111(1):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner C, Stegmaier S, Hänsch GM. Expression of granzyme B in peripheral blood polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN), myeloid cell lines and in PMN derived from haemotopoietic stem cells in vitro. Mol Immunol. 2008;45(6):1761–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jahrsdörfer B, et al. Granzyme B produced by human plasmacytoid dendritic cells suppresses T-cell expansion. Blood. 2010;115(6):1156–1165. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley JK, Takeda K, Akira S, Schreiber RD. Interleukin-10 Receptor Signaling through the JAK-STAT Pathway requirement for two distinct receptor-derived signals for anti-inflammatory action. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(23):16513–16521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dufait I et al (2019) Perforin and Granzyme B expressed by murine myeloid-derived suppressor cells: a study on their role in outgrowth of cancer cells. Cancers 11(6):808. 10.3390/cancers11060808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Kumar R, Yoneda J, Fidler IJ, Dong Z. GM-CSF-transduced B16 melanoma cells are highly susceptible to lysis by normal murine macrophages and poorly tumorigenic in immune-compromised mice. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65(1):102–108. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danciu C, et al. A characterization of four B16 murine melanoma cell sublines molecular fingerprint and proliferation behavior. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13:75. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-13-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoon CK, et al. Expansion of melanoma-specific lymphocytes in alternate gamma chain cytokines: gene expression variances between T cells and T cell subsets exposed to IL-2 versus IL-7/15. Cancer Gene Ther. 2014;21(10):441–447. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2014.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heusel JW, Wesselschmidt RL, Shresta S, Russell JH, Ley TJ. Cytotoxic lymphocytes require granzyme B for the rapid induction of DNA fragmentation and apoptosis in allogeneic target cells. Cell. 1994;76(6):977–987. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90376-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quatromoni JG, Singhal S, Bhojnagarwala P, Hancock WW, Albelda SM, Eruslanov E. An optimized disaggregation method for human lung tumors that preserves the phenotype and function of the immune cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;97(1):201–209. doi: 10.1189/jlb.5TA0814-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Condamine T, Gabrilovich DI. Molecular mechanisms regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cell differentiation and function. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston JA, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of STAT5, STAT3, and Janus kinases by interleukins 2 and 15. PNAS. 1995;92(19):8705–8709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mui AL, Wakao H, O’Farrell AM, Harada N, Miyajima A. Interleukin-3, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor and interleukin-5 transduce signals through two STAT5 homologs. EMBO J. 1995;14(6):1166–1175. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dufait I, Elsa VV, Eline M, David E, Mark DR, Karine B (2016) Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in myeloid-derived suppressor cells: an opportunity for cancer therapy. Oncotarget 7(27):42698–42715. 10.18632/oncotarget.8311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Prakash MD, et al. Granzyme B promotes cytotoxic lymphocyte transmigration via basement membrane remodeling. Immunity. 2014;41(6):960–972. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prakash MD, Bird CH, Bird PI. Active and zymogen forms of granzyme B are constitutively released from cytotoxic lymphocytes in the absence of target cell engagement. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87(3):249–254. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi K, Nakamura T, Adachi H, Yagita H, Okumura K. Antigen-independent T cell activation mediated by a very late activation antigen-like extracellular matrix receptor. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21(6):1559–1562. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keefe D, et al. Perforin triggers a plasma membrane-repair response that facilitates CTL induction of apoptosis. Immunity. 2005;23(3):249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darmon AJ, Nicholson DW, Bleackley RC. Activation of the apoptotic protease CPP32 by cytotoxic T-cell-derived granzyme B. Nature. 1995;377(6548):446–448. doi: 10.1038/377446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darmon AJ, Ley TJ, Nicholson DW, Bleackley RC. Cleavage of CPP32 by granzyme B represents a critical role for granzyme B in the induction of target cell DNA fragmentation *. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(36):21709–21712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu Y, Sarnecki C, Fleming MA, Lippke JA, Bleackley RC, Su MS-S. Processing and activation of CMH-1 by granzyme B (∗) J Biol Chem. 1996;271(18):10816–10820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chinnaiyan AM, et al. Cytotoxic T-cell-derived granzyme B activates the apoptotic protease ICE-LAP3. Curr Biol. 1996;6(7):897–899. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00614-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao X, et al. Granzyme B and perforin are important for regulatory T cell-mediated suppression of tumor clearance. Immunity. 2007;27(4):635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boissonnas A, et al. Foxp3+ T cells induce perforin-dependent dendritic cell death in tumor-draining lymph nodes. Immunity. 2010;32(2):266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gondek DC, Lu L-F, Quezada SA, Sakaguchi S, Noelle RJ. Cutting edge: contact-mediated suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells involves a granzyme B-dependent, perforin-independent mechanism. J Immunol. 2005;174(4):1783–1786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao D-M, Thornton AM, DiPaolo RJ, Shevach EM. Activated CD4+CD25+ T cells selectively kill B lymphocytes. Blood. 2006;107(10):3925–3932. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Younes S-A, et al. IL-15 promotes activation and expansion of CD8+ T cells in HIV-1 infection. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(7):2745–2756. doi: 10.1172/JCI85996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cruz-Guilloty F, et al. Runx3 and T-box proteins cooperate to establish the transcriptional program of effector CTLs. J Exp Med. 2009;206(1):51–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hagn M, et al. Activated mouse B cells lack expression of granzyme B. J Immunol. 2012;188(8):3886–3892. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirst CE, Buzza MS, Sutton VR, Trapani JA, Loveland KL, Bird PI. Perforin-independent expression of granzyme B and proteinase inhibitor 9 in human testis and placenta suggests a role for granzyme B-mediated proteolysis in reproduction. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7(12):1133–1142. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.12.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takano N, Matusi H, Takahashi T. Granzyme N, a novel granzyme, is expressed in spermatocytes and spermatids of the mouse testis1. Biol Reprod. 2004;71(6):1785–1795. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.030452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.