Abstract

Beta-2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) mediates neural signaling from the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) to the immune system to modulate immunogenic and immunosuppressive responses for maintaining immune homeostasis. β2-AR regulates various cellular activities on the innate and adaptive immune cells through differential signaling to modulate activation, proliferation, differentiation, and cytokine production. This signaling pathway has been found to be critical for regulating anti-tumor immune responses and autoimmune responses. Recently, β2-AR has also been implicated in the mobilization of immune cells in peripheral blood and ex-vivo expansion of cytotoxic T cells from donor blood that has clinical implications for improving cancer immunotherapy. This review attempts to provide a comprehensive overview of the established and emerging roles of β2-AR signaling in immune homeostasis, cancer immunotherapy, and autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: Beta-2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR), Immune homeostasis, Cancer immunotherapy, Autoimmune diseases

Introduction

Our nervous system communicates with the rest of our body by releasing neurotransmitters including catecholamines that bind adrenergic receptors to induce regulatory functions. Adrenergic receptors (ARs) are guanine nucleotide-binding protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that bind catecholamine neurotransmitters, epinephrine and norepinephrine (NE), to transmit information of the nervous system to other organs. There are two major types of ARs, alpha-adrenergic receptors (α-ARs) and beta-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs), which can further be divided into α-AR sub-types (α1 and α2-AR) and β-AR sub-types (β1, β2, and β3-AR) [1]. These receptors associate with different classes of Gα sub-unit to elicit various signaling pathways. Unlike the selective expression pattern of other sub-types on various organ, tissue and cell types, beta-2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) is broadly expressed on most types of immune cells. Therefore, this review will largely focus on β2-AR signaling in the immune system and related disorders.

In the immune system, both innate and adaptive immune cells express ARs. Innate immune cells including monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs) express both α-AR and β-AR subtypes depending on the site of tissue location [1]. On the other hand, natural killer (NK) cells of innate immune system and adaptive immune cells including B-cells, cytotoxic T-cells (Tc cells), and helper T-cells (Th cells), apart from Th2 cells (a sub-type of Th cells), pre-dominantly express β2-AR [1]. The immune cells that do express β2-ARs have varying β2-AR receptor density on their surface. In contrast, Th2 cells do not express β2-AR due to the epigenetic modifications such as histone-3- & histone-4-acetylation, and histone-3-Lysine-4-, histone-3-Lysine-9-, & histone-3-Lysine-27 methylation in the vicinity of β2-AR promoter that suppresses its transcription [2]. β2-AR signaling regulates the production and secretion of cytokines and modulates the cytotoxic activity of immune cells to elicit immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive responses. The receptor is crucial for mediating regulatory demands from the nervous system to the immune system, thereby, maintaining immune homeostasis. Alternatively, β2-AR also plays an important role in modulating anti-tumor immune responses in the tumor microenvironment (TME). Thus, it is necessary to elucidate the function of β2-AR in immune regulation so that β2-AR signaling can be exploited therapeutically to expand the application of immunotherapy.

β2-AR Regulation by the sympathetic nervous system

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS), a part of the autonomic nervous system that mediates fight or flight response, maintains homeostasis by regulating appropriate responses to physiological and psychological stress. Stressors induce the SNS to release NE through post-ganglionic sympathetic nerve terminals and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis to release epinephrine from adrenal medulla [3]. The post-ganglionic adrenergic/sympathetic nerve fibers travel along blood vessels and innervate the parenchyma of primary and secondary lymphoid organs including thymus, bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes and the TME to release NE locally [3]. Epinephrine released from the adrenal gland circulates through the vasculature. Epinephrine and NE in the vicinity of the immune cells bind β2-AR to induce signaling cascade [3].

Encoded by ADRB2 gene, β2-AR is a GPCR associated with heterotrimeric G-proteins made up of Gα, Gβ, and Gγ sub-units. It can associate with either a stimulatory or an inhibitory sub-class of Gα sub-unit, but β2-AR predominantly associates with the stimulatory Gα (Gαs) sub-unit [1]. In a canonical Gαs-mediated GPCR pathway, NE binds β2 β2-AR to activate G-protein heterotrimer leading to guanosine diphosphate (GDP)/guanosine triphosphate (GTP) exchange on Gαs. Subsequently, GTP-bound Gαs sub-unit activates adenylyl cyclase (AC) to induce the production of a second messenger, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Increasing intracellular cAMP leads to the activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) followed by phosphorylation of the transcription factor cAMP response element binding (CREB) protein [1, 2], which then translocates to the nucleus and regulates gene expression to mediate cellular activity.

β2-AR signaling in major cell types of adaptive and innate immune responses

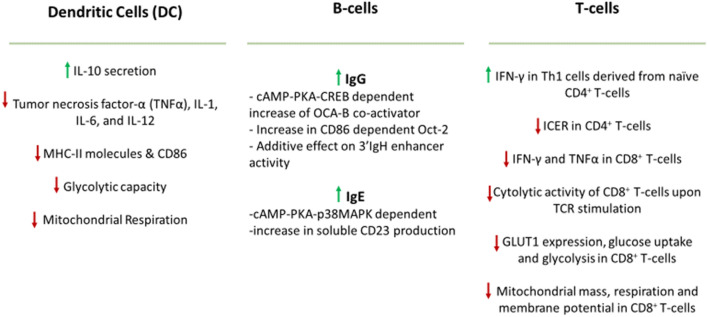

Epinephrine, NE and pharmacological ligands (agonists and antagonists) induce differential β2-AR signaling on innate and adaptive immune cells, which respond in a context-dependent manner such that environmental cues and types of antigens induce various responses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Differential responses to β2-AR signaling in major immune cell types

Antigen presentation machinery and T cell priming

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the professional antigen presenting cells that prime naïve T cells for various effector responses. They do so by forming an immunological synapse with T cells through an MHC-peptide-TCR complex, upregulating co-stimulatory molecules, and releasing polarizing cytokines for T cell activation, expansion, and differentiation. However, β2-AR stimulation impairs this ability of DCs to present antigens and elicit responses in an inhibitory Gα (Gαi) protein-dependent, PKA-independent manner [4, 5]. In LPS-activated murine bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs), β2-AR agonist treatment impairs the phagosomal degradation and cross-presentation of antigen peptides on their MHC class I molecules to CD8+ T cells [5]. β2-AR agonistic stimulation further suppresses the expression of antigen presenting MHC class II molecules in BMDCs [4]. Consequent lack of antigen presentation and TCR stimulation affects differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells and expansion of CD8+ T cells. β2-AR stimulated DCs reduce IL-12p70 and IFN-γ secretion in favor of IL-17a production such that β2-AR signaling may promote Th17 differentiation of T cells [6]. Moreover, β2-AR signal on BMDCs synergizes with their toll like receptor (TLR) signals to drive early IL-10 secretion and suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF- α, IL-6, and IL-12) production in part by inhibiting NF-kB, MAPK, and/or AP-1 pathway [5–7]. β2-AR signaling also suppresses the expression of co-stimulatory marker CD86 and STAT3 phosphorylation in DCs. Metabolic dysregulation, such as increased spare respiratory (mitochondrial respiration) and glycolytic capacity, and decreased mTOR expression upon β2-AR activation further compromises DC function [8]. Altogether, β2-AR signaling skews immunogenic DCs toward tolerogenic DCs.

Humoral immune response

In the case of B-cells, β2-AR signaling promotes the rate of transcription and production of IgG1 and IgE antibodies [1, 2]. IgG1 production is upregulated with the additive effect of two pathways. In a direct pathway, the expression of a coactivator protein (OCA-B) is induced in a cAMP-PKA-CREB dependent manner. The other indirect pathway induces the expression of the costimulatory molecule CD86 that upregulates the expression of Oct-2, a B-cell specific transcription factor. Together, both pathways promote OCA-B and Oct-2 interaction to induce 3’IgH enhancer activity required for more IgG1 production. Another pathway involving cAMP-PKA-p38MAPK leads to the upregulation of soluble CD23 that has been associated with promoting IgE production [1, 2].

Activation and differentiation of T cells

Various subsets of T cells mount different responses to β2-AR signal depending on their differentiation phase and environmental cues. β2-AR engagement on the Th1 clonal cells and naïve CD4+ T cells, but not primary effector Th1 cells, decreases the production of IL-2 and IFN-γ in a cAMP dependent manner [9, 10]. However, Th1 cells generated from naïve CD4+ T cells in the presence of IL-12 produced high level of IFN-γ in response to β2-AR signal [2]. β2-AR-mediated upregulation of cAMP could also suppress IL-2 receptor expression in T cells [2]. Interestingly, β2-AR stimulation can also impair the differentiation of Th1 cells from naïve CD4+ T cells due to reduced IL-12 availability from monocytes and DCs [2]. On CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cells, β2-AR induces suppressive activity of Treg cells and promotes Treg cell-mediated generation of induced Tregs from naïve T cells [11]. NE and pharmacological ligands stimulating β2-AR on CD8+ T cells were found to inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ and TNF-α) and cytolytic activity of CD8+ T cells upon T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation [12]. β2-AR signaling also compromises the metabolic reprograming, glycolytic and mitochondrial activity, in CD8+ T cells necessary for differentiation into effector phenotype. β2-AR engagement in CD8+ T cells leads to suppression of glycolytic activity, which is attributed to the decrease in glucose uptake and expression of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) as well as impaired mitochondrial mass, respiration and membrane potential [13].

Innate immune responses

In addition to T cell and B cell responses, several recent studies have highlighted the roles of β2-AR signaling in innate immune responses. The group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) are potent sources of the type 2 inflammatory response that is induced by various environmental and infectious stimuli. Murine ILC2s were shown to express β2-AR and colocalize with adrenergic neurons in the intestine, and the β2-AR pathway acts as a cell-intrinsic negative regulator of ILC2 responses through inhibition of cell proliferation and effector function [14]. In addition, genetic, pharmacologic, or surgical removal of local sympathetic innervations promoted LPS-elicited innate immune response in the lung [15]. Sympathetic ablation also enhanced IL-33-elicited type 2 innate immunity. Notably, NE or pharmacologic agonists of the β2-AR, can inhibit the LPS- or IL-33-elicited immune response in a cell-intrinsic manner that involves that macrophage activation, neutrophil recruitment, and ILC2-mediated type 2 inflammatory response [15]. Together, these recent studies exemplified the critical function β2-AR signaling in modulating innate immune responses.

Migration and mobilization of immune cells

β2-AR inhibits lymphocyte egress of B cells and T cells, more specifically central memory T cells, from lymph nodes by enhancing retention signals mediated by CCR7 and CXCR4 chemokine receptors. However, it does not seem to affect lymphocyte homing to lymph nodes [16]. Circadian rhythm could play a role in how β2-AR regulates lymphocyte migration as β2-AR-mediated lymphocyte retention in lymph nodes peaks at nighttime while lymphocyte recirculation and humoral immune response varies during the day [17]. β2-AR signaling is also involved in the migration of immune cells to blood circulation. Studies in healthy humans subjected to exercise-induced stress found that β-AR activation, essentially β2-AR, promotes the mobilization of non-classical monocytes, γδ T-cells, NK cells, and subsets of CD8+ T cells (central memory, effector memory and CD45RA+ effector memory subsets) to the circulation [18]. This effect was not observed in naïve CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells and classical monocytes [18]. In addition, mobilization and ex vivo expansion of virus specific T cells, generated from PBMCs isolated from healthy humans, against cytomegalovirus (CMV) were found to be partially regulated by β2-AR post exercise [19].

β2-AR signaling in tumor immunity: preclinical animal models and human studies

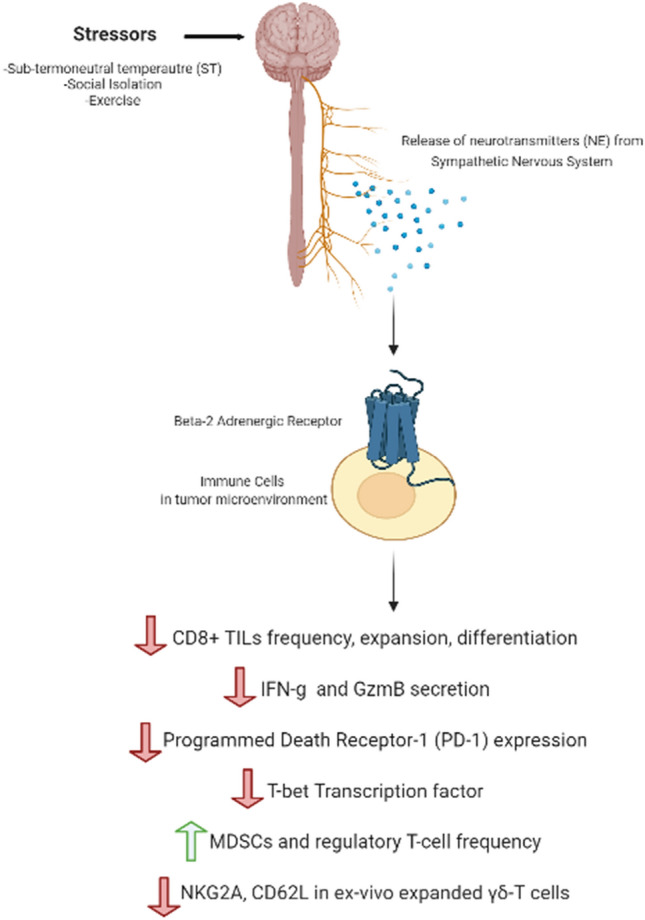

Mounting evidence has demonstrated that physiological and psychological stress may lead to upregulation of β2-AR signaling [20], which results in suppression of antitumor immune response in the tumor microenvironment and limits the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Physiological and psychological stress leads to upregulation of β2-AR signaling that suppresses anti-tumor immune response in the tumor microenvironment

In pre-clinical studies, chronic adrenergic stress is induced through cold temperature, social isolation, or physical exertion. It has been reported that sub-thermoneutral temperature (ST) of 20–26 °C housing of mice, mandated by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), induces mild, chronic adrenergic stress that increases the level of NE release from the SNS to produce more body heat by upregulating metabolic activities, a process also known as adaptive thermogenesis. In tumor bearing mice, ST elevates the level of NE and pro-tumoral anti-apoptotic molecules and induces β2-AR activation in comparison to the mice housed at thermoneutral temperature (TT) of 30–31 °C [21, 22]. Additional studies demonstrate that ST induced adrenergic stress suppresses antitumor adaptive immune responses. In various murine tumor models including B16.F10 & B16-OVA melanoma, CT26 colorectal carcinoma, Pan02 pancreatic, and 4T1 breast cancer models, ST induced cold stress led to rapid tumor growth that was significantly delayed by pre-treatment with pan-β-AR antagonist (propranolol) [23, 24]. Importantly, the pan-β-AR antagonist treatment had minimal effect on the tumor control in ADRB2 deficient mice suggesting that β2-AR is responsible for transmitting ST induced stress signal [23]. Lower frequency of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cells and IFN-γ producing CD8+ T-cells was observed in the tumor microenvironment (TME) of a subset (B16.F10, CT26) of the tumor models housed at ST than that at TT [23]. ST housed murine models exhibited lower expression of Glut-1 and higher frequency of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), potent suppressors of T-cell function, and Treg cells in TME [24]. ST induced adrenergic stress, most likely through β2-AR, can be alleviated with propranolol that increases activity of CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) by upregulating T-box transcription factor TBX21 (T-bet) that drives the transcriptional activity of IFN-γ and granzyme B (GzmB). The antagonist significantly increased the frequency of T-bet+ CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells as well as the ratio of effector IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells to Treg cells in B16-OVA tumor model, and decreased the frequency of programmed cell death protein (PD-1) receptor expressing CD8+ TILs on 4T1 and B16-OVA tumor models [23].

In support of the role of β2-AR in anti-tumor immunity, Mohammadpour et al. reported that ADRB2-deficient host mice exhibited improved graft-versus-tumor (GVT) effect by promoting expansion and memory formation of donor CD8+ T-cells, while ameliorating graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) by improving Treg cell reconstitution from donor BM-derived stem cells after allogenic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) [8]. β2-AR signaling is also involved in regulating anti-tumor immune responses in non-irradiated tumors to promote abscopal effect following ionizing radiation therapy (RT). Chen et al. observed that in comparison to the irradiated WT mice, irradiated ADRB2-deficient mice increased intra-tumoral effector CD8+ T cells, marked by IFN-γ, GzmB, TNF-α, T-bet, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 3 (CXCR3), and decreased M2 macrophages in the distant non-irradiated tumor sites, while the amount of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and C-X-C motif chemokine 9 (CXCL9)-ligand for CXCR3 increased in the murine serum [21]. They propose that β2-AR signaling leads to the retention of effector CD8+ T-cells within tumor draining lymph nodes, associated with reduced CXCR3-CXCL9 mediated T cell egress, to suppress systemic immune response following radiation [21].

TCR-γδ T-cells, a class of T-cell sub-lineages with the other being TCR-αβ T-cells, that recognize antigens without MHC presentation have also been investigated in anti-tumor immune responses. Baker et al. found that systemic β-AR activation through acute dynamic exercise increases TCR-γδ T-cell mobilization in the peripheral blood of healthy humans and induces Vγ9Vδ2 TCR-γδ subtype of T-cell generation from blood via ex-vivo expansion [25]. The expanded TCR-γδ T-cells post exercise downregulated inhibitory receptors like NKG2A and CD62L so that the dominant activating receptor NKG2D exerted cytotoxic effects against HLA expressing multiple myeloma cell line U266 and 221.AEH lymphoma cell line. Administering nadolol (β1- & β2-AR antagonist) and bisoprolol (β1-AR antagonist) revealed that such cytolytic effects are largely modulated by β2-AR signaling [25].

β2-AR signaling in breast cancer

Breast cancer is a major type of solid tumor for which both clinical studies of cancer patients and preclinical animal models have revealed the biological relevance the β2-AR pathway. Immunohistochemical studies on breast cancer tissue samples have found a strong correlation of β2-AR expression with Her2 and luminal estrogen receptor positive (ER +) tumor status, and interestingly, among the hormone receptor positive (HR +) patients, strong β2-AR expression correlated with better disease-free survival [26]. In contrast, high β2-AR expression among estrogen receptor (ER)-negative patients in a cohort of breast cancer patients served as an independent, poor prognostic factor for survival. The ER-negative patients with high β2-AR tumors exhibited significant association with programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) negativity [27].

Using MCF-7 cells overexpressing Her2 (MCF-7/Her2), Shi et al. found a positive feedback loop between Her2 and β2-AR that induces phosphorylation and activation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and STAT3 to upregulate the expression of the receptor [28]. It was also observed that there is a negative correlation between β2-AR expression and trastuzumab response in Her2-overexpressing breast cancer patients [29]. Trastuzumab treatment, dependent on inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/ protein kinase B (Akt) pathway, is altered by catecholamine induced β2-AR activation that upregulates the expression of miR-21 and Mucin 1 through Her2-STAT3 mediated pathway and downregulates miR-199a/d-3p [29]. Subsequent inhibition of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and mTOR inhibition leads to activation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway conferring trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer patients [29]. Similarly, treatment of triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells with propranolol and ICI 118,551 (a selective β2-AR antagonist) inhibited the viability and cell cycle progression by suppressing the activation of ERK1/2:COX-2 signaling pathways to induce apoptosis [30].

Chronic social-psychological stress has also been associated with breast cancer progression. Psychological stress inhibits peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), a critical nuclear receptor for adipogenesis, through β2-AR activation. Subsequent induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) promoted vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2)-mediated angiogenesis [31]. Similar experiment found that social-psychological stress induced higher expression of epinephrine and M2-like tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) in breast cancer tumor models. Antagonizing β-AR with propranolol suppressed epinephrine-induced M1 to M2 macrophage polarization primarily through β2-AR, and the knock down of β2-AR on macrophages inhibited tumor proliferation in vitro [32].

Several pre-clinical studies have utilized ADBR2-deficient mice with orthotopic implantation of metastatic 4T1 tumor cell lines or non-metastatic AT-3 tumor cell lines. These studies have employed pharmacological ligands and cold induced stress at ST to induce adrenergic signaling and study the rate of tumor growth. Kokolus et al. reported that ST induced cold stress promotes rapid tumor growth in 4T1 mammary tumor models. Higher frequency of CD8+ T-cells with metabolically active markers (CD69+, INF-g+, and Glut-1+) in tumor bearing mice at TT accounted for better control of tumor. Significant reduction on Treg cells was also observed in the tumor bearing mice housed at TT [24]. ST accelerated mammary tumor growth is most likely to be mediated by β2-ARs since Bucsek et al. showed that propranolol, a pan-β-AR antagonist, slowed tumor growth on β2-AR WT 4T1 tumor models at ST but failed to reduce tumor growth on ADRB2 deficient mice, especially when 4T1 tumor cells lack β-ARs [23]. Notably, combination treatment of propranolol and anti-PD-1 inhibited tumor growth and increased the frequency of effector CD8+ IFNγ+ TILs in TME of the 4T1 models [23].

Similarly, Mohammadpour et al. (2019) found that 4T1 and AT-3 tumor models housed at ST exhibit rapid tumor growth, increased tumor weight and circulating pro-tumoral cytokines. β2-AR activation on MDSCs increased their frequency, survival, and immunosuppressive activity in TME of the breast tumor models [33]. Tumor vascularization might also be affected by the β2-AR signaling as CD31 and VEGF-α expression was significantly higher in TME. Increased survival of MDSCs in response to β2-AR signaling can be attributed to STAT3 phosphorylation/activation and partially to the resistance to apoptosis regulated by Fas/FasL pathway [33].

β2-AR signaling in graft-versus-host disease

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is the flip side of graft-versus-tumor (GVT) effect that occurs when treating blood cancers with allogenic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT). While alloHCT is desired to target cancer cells, some normal host tissues are also affected by this treatment. Naturally, cold adrenergic stress induced by standard temperature housing also affects GVHD along with GVT effect. Cold adrenergic stress transmits signal through β2-AR to reduce the severity and lethality of GVHD as identified by using various pharmacological ligands of β2-AR. β2-AR signaling suppresses the proliferation of donor T cells in both T-cell intrinsic and APC-mediated extrinsic manner and limits their infiltration of to host liver [34]. Furthermore, alloHCT with ADRB2 deficient donor T cells leads to more severe and lethal acute GVHD [35]. β2-AR regulates the phenotypic shift of Th1/Th17:Th2/Treg balance in donor CD4+ and CD8+ T cells toward immunosuppressive Th2/Treg phenotype both in vivo and in vitro. AlloHCT with β2-AR proficient donor cells also increased the population of donor-derived myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). Similar effect of reduced severity and lethality of GVHD in alloHCT models was observed with selective agonism of β2-AR with bambuterol, a long-acting beta adrenoreceptor agonist [35].

β2-AR signaling in autoimmune diseases

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease that mainly affects the synovium of joints leading to synovitis and joint destruction. The presence of autoantibodies such as anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs) and rheumatoid factors (RFs) serve as a diagnostic and prognostic marker for RA. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on the β2-AR gene at amino acid position 16 and 27, especially Arg16 and Gln27, have been associated with the susceptibility to RA as well as the level of RFs and ACPAs [36, 37]. The expression of β2-ARs is downregulated on the peripheral blood lymphocytes and synovial fluid lymphocytes of RA patients. Within the lymphocytes, B cells and CD8+ T-cells have significantly lower density of β2-ARs in RA patients. Consequently, β2-AR stimulation of PBMCs from RA patients failed to suppress T cell proliferation or induce apoptosis of B cells [38]. Dysregulated β2-AR signaling in the early stages of RA pathogenesis is related with inflammation through B-cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages [38]. While B-cells proliferate and produce autoantibodies, DCs and macrophages upregulate antigen processing and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-2 and IL-6 [38]. However, in the later stage of RA, β2-AR exerts more immunosuppressive activity by inducing the production of IL-10 and IL-33 from B-cells, macrophages and DCs [38]. β2-AR signaling in adjuvant-induced arthritis and collagen-induced arthritis rodent models have been reported to disrupt lymphocyte proliferation, Th1 to Th2 cell differentiation, TGF-β production, and β2-AR desensitization [38]. Administration of pan-β blocker carvedilol rescued the splenic atrophy and reduced inflammatory cytokines and markers such as TNF-α and C-reactive protein [38].

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system characterized by demyelinating lesions in the white and grey matter of brain and spinal cord. Astrocytic β2-AR regulates the expression of major histocompatibility class II molecule (MHC II) by inactivating coactivator class II transactivator (CIITA), which is required for the transcription of MHC II, through Protein Kinase A [39]. β2-AR on astrocytes is also involved in regulation of glycogenolysis, glutamate excitotoxicity, and in the production of neurotrophic factors [40]. However, astrocytes in the MS lesions and surrounding normal-appearing white matter in MS patients are deficient of β2-AR. The loss of β2-AR impairs the ability of astrocytes to generate energy through glycogenolysis and ultimately results in the accumulation of intra-axonal Calcium ions that can activate proteases and phospholipases. In parallel, β2-AR deficiency leads to the expression of MHC II on the surface of astrocytes such that these glial cells can serve as facultative APCs capable of driving an inflammatory cascade [39, 40]. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of MS, revealed that the depletion of central adrenergic nerves in CNS lowers NE level and accelerates the onset of EAE symptoms. Araujo et al. reported that β2-AR signaling suppresses the development of EAE by limiting encephalitogenic CD4+ T-cell responses. The proliferative capability of the CD4+ T-cells was also impaired by β2-AR signaling [41].

Myasthenia gravis

Myasthenia Gravis is caused by autoantibodies against nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR), muscle-specific kinase (MuSK), or low-density lipoprotein-receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4) that destabilize the postsynaptic membrane at the neuromuscular junction. The disease affects several muscles including ocular, facial, neck, limb, truncal, bulbar, and respiratory muscles resulting in muscle weakness. β2-AR gene polymorphism at amino acid position 16, particularly the prevalence of homozygosity of Arg16, may confer susceptibility to MG [42]. Analyses of blood serum have revealed that some MG patients have autoantibodies against β2-AR, most likely corresponding to 172–197 residue on the second extracellular loop of the receptor [42]. There is a possibility that these autoantibodies could bind to β2-AR and downregulate its expression to lower the density of β2-AR on the surface of the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of MG patients. Autoreactive T cells and anti-β2-AR IgG secreting B cells have also been detected in MG patients. Treatment of congenital myasthenic syndrome patients with albuterol (a β2-AR agonist) has been effective in improving muscle strength and daily activities. In an experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis (EAMG) mice model generated by passive transfer of rat anti-AChR IgG2a, terbutaline (a β2-AR agonist) treatment decreased the clinical severity of illness. Similarly, albuterol treatment of another MG mouse model, developed through passive transfer of anti-MuSK-positive IgG from MG patients, leads to reduced whole body weakness and weight loss. However, these studies failed to identify the mechanism for the neuromuscular improvements as the agonist treatment did not rescue loss of postsynaptic AChR, loss of synaptic transmission, nor the decline of compound muscle action potential [43].

Concluding remarks: gap of knowledge and future directions

Catecholamines released from the SNS modulate the activity of β2-AR on immune cells to mediate various functions in homeostatic, tumorigenic, and autoimmune conditions. Due to limitation of space, this overview only summarizes limited examples of these conditions. In summary, β2-AR is involved in modulating antigen presentation machinery of DCs, dampening of T-cell responses, retaining B and T lymphocytes, altering type 2 immune responses, and more. While beta adrenergic receptors on the surface of tumor cells have been tested as therapeutic targets in various cancers, β2-AR-targeted modulation of immune response has not been explored as extensively in the cancer setting. That is at least partially due to the remaining gap of knowledge regarding the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which the β2-AR pathway affects immune responses systemically and locally in the TME. Nevertheless, as mounting evidence shows that β2-AR regulates anti-tumor immune response as well as cancer progression, the use of β2-AR antagonists in combination with typical immunotherapy could prove to be beneficial for cancer treatment in clinical settings. A number of such ongoing clinical trials are expected to reveal potential efficacy in the next few years. β2-AR has also been associated with mobilization of immune cells which has clinical implications for adoptive cell transfer and allogenic hematopoietic cell transplantation therapies. Furthermore, considering that SNPs on similar positions of the β2-AR gene occur frequently in patients of rheumatoid arthritis and myasthenia gravis, the role of β2-AR in autoimmune diseases cannot be dismissed easily. Therefore, currently FDA-approved pharmacologic agonists and/or antagonists should also be tested in re-purposing trials for better management of relevant types of autoimmune diseases. Altogether, it is imperative that more studies should investigate the fundamental regulatory mechanisms of β2-AR in cancer and autoimmune diseases while an increasing number of clinical re-purposing trials are being performed to test the effect of targeting β2-AR on various types of immunotherapies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funds through the National Institute of Health (R01HL159973), the Maryland Department of Health's Cigarette Restitution Fund (CRF) Program and University of Maryland Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center (UMGCC) Support Grant (P30CA134274).

Author contributions

S.T. and X.C. designed the review project. S.T. and X.C. wrote the manuscript.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Padro CJ, Sanders VM. Neuroendocrine regulation of inflammation. Semin Immunol. 2014;26(5):357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders VM. The beta2-adrenergic receptor on T and B lymphocytes: do we understand it yet? Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(2):195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elenkov IJ, et al. The sympathetic nerve–an integrative interface between two supersystems: the brain and the immune system. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52(4):595–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herve J, et al. beta2-adrenergic stimulation of dendritic cells favors IL-10 secretion by CD4(+) T cells. Immunol Res. 2017;65(6):1156–1163. doi: 10.1007/s12026-017-8966-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herve J, et al. beta2-Adrenoreceptor agonist inhibits antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2013;190(7):3163–3171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takenaka MC, et al. Norepinephrine Controls Effector T Cell Differentiation through beta2-Adrenergic Receptor-Mediated Inhibition of NF-kappaB and AP-1 in Dendritic Cells. J Immunol. 2016;196(2):637–644. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agac D, et al. The beta2-adrenergic receptor controls inflammation by driving rapid IL-10 secretion. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;74:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohammadpour H, et al. Blockade of Host beta2-Adrenergic Receptor Enhances Graft-versus-Tumor Effect through Modulating APCs. J Immunol. 2018;200(7):2479–2488. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders VM, et al. Differential expression of the beta2-adrenergic receptor by Th1 and Th2 clones: implications for cytokine production and B cell help. J Immunol. 1997;158(9):4200–4210. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.158.9.4200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramer-Quinn DS, et al. Cytokine production by naive and primary effector CD4+ T cells exposed to norepinephrine. Brain Behav Immun. 2000;14(4):239–255. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2000.0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guereschi MG, et al. Beta2-adrenergic receptor signaling in CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells enhances their suppressive function in a PKA-dependent manner. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43(4):1001–1012. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estrada LD, Agac D, Farrar JD. Sympathetic neural signaling via the beta2-adrenergic receptor suppresses T-cell receptor-mediated human and mouse CD8(+) T-cell effector function. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46(8):1948–1958. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiao G, et al. beta-Adrenergic signaling blocks murine CD8(+) T-cell metabolic reprogramming during activation: a mechanism for immunosuppression by adrenergic stress. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68(1):11–22. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2243-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moriyama S, et al. beta(2)-adrenergic receptor-mediated negative regulation of group 2 innate lymphoid cell responses. Science. 2018;359(6379):1056–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu T, et al. Local sympathetic innervations modulate the lung innate immune responses. Sci Adv. 2020;6(20):eaay1497. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakai A, et al. Control of lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes through beta2-adrenergic receptors. J Exp Med. 2014;211(13):2583–2598. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki K, et al. Adrenergic control of the adaptive immune response by diurnal lymphocyte recirculation through lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2016;213(12):2567–2574. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graff RM, et al. beta(2)-Adrenergic receptor signaling mediates the preferential mobilization of differentiated subsets of CD8+ T-cells, NK-cells and non-classical monocytes in response to acute exercise in humans. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;74:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunz HE, et al. The effects of beta1 and beta1+2 adrenergic receptor blockade on the exercise-induced mobilization and ex vivo expansion of virus-specific T cells: implications for cellular therapy and the anti-viral immune effects of exercise. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2020;25(6):993–1012. doi: 10.1007/s12192-020-01136-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang W, Cao X. Beta-Adrenergic Signaling in Tumor Immunology and Immunotherapy. Crit Rev Immunol. 2019;39(2):93–103. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.2019031188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen M, et al. Adrenergic stress constrains the development of anti-tumor immunity and abscopal responses following local radiation. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1821. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15676-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eng JW, et al. Housing temperature-induced stress drives therapeutic resistance in murine tumour models through beta2-adrenergic receptor activation. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6426. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bucsek MJ, et al. beta-Adrenergic Signaling in Mice Housed at Standard Temperatures Suppresses an Effector Phenotype in CD8(+) T Cells and Undermines Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Cancer Res. 2017;77(20):5639–5651. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kokolus KM, et al. Baseline tumor growth and immune control in laboratory mice are significantly influenced by subthermoneutral housing temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(50):20176–20181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304291110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker FL, et al. Systemic beta-Adrenergic Receptor Activation Augments the ex vivo Expansion and Anti-Tumor Activity of Vgamma9Vdelta2 T-Cells. Front Immunol. 2019;10:3082. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du Y, et al. Association of alpha2a and beta2 adrenoceptor expression with clinical outcome in breast cancer. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(7):1337–1344. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.890928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurozumi S, et al. beta2-Adrenergic receptor expression is associated with biomarkers of tumor immunity and predicts poor prognosis in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;177(3):603–610. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi M, et al. The beta2-adrenergic receptor and Her2 comprise a positive feedback loop in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125(2):351–362. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0822-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu D, et al. beta2-AR signaling controls trastuzumab resistance-dependent pathway. Oncogene. 2016;35(1):47–58. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie WY, et al. betablockers inhibit the viability of breast cancer cells by regulating the ERK/COX2 signaling pathway and the drug response is affected by ADRB2 singlenucleotide polymorphisms. Oncol Rep. 2019;41(1):341–350. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou J, et al. Activation of beta2-Adrenergic Receptor Promotes Growth and Angiogenesis in Breast Cancer by Down-regulating PPARgamma. Cancer Res Treat. 2020;52(3):830–847. doi: 10.4143/crt.2019.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qin JF, et al. Adrenergic receptor beta2 activation by stress promotes breast cancer progression through macrophages M2 polarization in tumor microenvironment. BMB Rep. 2015;48(5):295–300. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2015.48.5.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohammadpour H, et al. beta2 adrenergic receptor-mediated signaling regulates the immunosuppressive potential of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(12):5537–5552. doi: 10.1172/JCI129502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leigh ND, et al. Housing Temperature-Induced Stress Is Suppressing Murine Graft-versus-Host Disease through beta2-Adrenergic Receptor Signaling. J Immunol. 2015;195(10):5045–5054. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohammadpour H, et al. β2-Adrenergic receptor activation on donor cells ameliorates acute GvHD. JCI Insight. 2020 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.137788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malysheva O, et al. Association between beta2 adrenergic receptor polymorphisms and rheumatoid arthritis in conjunction with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DRB1 shared epitope. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(12):1759–1764. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.083782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu B, et al. beta2-adrenergic receptor gene single-nucleotide polymorphisms are associated with rheumatoid arthritis in northern Sweden. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33(6):395–398. doi: 10.1080/03009740410010326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu L, et al. Bidirectional Role of beta2-Adrenergic Receptor in Autoimmune Diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1313. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Keyser J, et al. Astrocytes as potential targets to suppress inflammatory demyelinating lesions in multiple sclerosis. Neurochem Int. 2010;57(4):446–450. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Durfinova M, et al. Role of astrocytes in pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis and their participation in regulation of cerebral circulation. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2014;35(8):666–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Araujo LP, et al. The sympathetic nervous system mitigates CNS autoimmunity via β2-adrenergic receptor signaling in immune cells. Cell Rep. 2019;28(12):3120–3130.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang L, Zhang Y, He M. beta2-Adrenergic receptor gene polymorphisms in the relapse of myasthenia gravis with thymus abnormality. Int J Neurosci. 2017;127(4):291–298. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2016.1202952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghazanfari N, et al. Effects of the ss2-adrenoceptor agonist, albuterol, in a mouse model of anti-MuSK myasthenia gravis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e87840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]