Introduction/History/Definitions/Background

Invasive or selective pulmonary angiography, first described by Sasahara and colleagues in 1964, was historically used as the gold standard diagnostic test for the evaluation of a wide array of congenital and acquired pulmonary arterial conditions, most commonly pulmonary thromboembolic diseases.(1) However, with the emergence of various minimally invasive imaging modalities such as computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA), ventilation-perfusion lung scanning (V/Q scan), and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), the role of invasive pulmonary angiography (IPA) is shifting largely to the assistance of advanced pharmaco-mechanical therapies for conditions such as chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, pulmonary artery stenosis and aneurysms, and pulmonary artery neoplasms.(2) Understanding pulmonary vascular anatomy and the optimal pulmonary angiography technique is crucial for the invasive management of CTEPH. In this issue dedicated to pulmonary vascular interventions, we review the pulmonary arterial anatomy, procedural planning, patient positioning and step-by-step performance of IPA, and interpretation of the most common thromboembolic conditions using IPA.

Nature of the Problem/Diagnosis:

With the proliferation of interventional therapies for pulmonary thrombotic and vascular conditions, training in and the understanding of invasive pulmonary angiography is valuable. The aim of this review is to describe in detail the best practices for this procedure and interpretation of findings.

Discussion:

I). Anatomy

Pulmonary Arterial Circulation

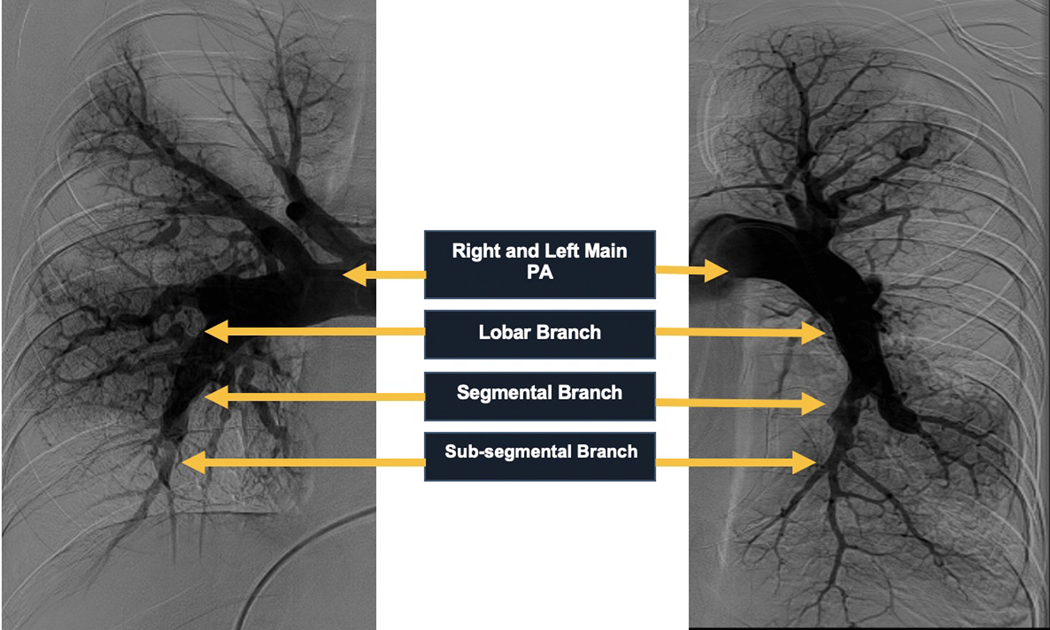

The pulmonary circulatory system is composed of the pulmonary arteries, pulmonary veins, and bronchial arteries. The main pulmonary artery (MPA) arises superiorly from the pulmonary annulus surrounding the base of the right ventricle coursing posteriorly and superiorly and then bifurcates into the right pulmonary artery (RPA) and left pulmonary artery (LPA) below the aortic arch to the left of the midline. The RPA and LPA divide into lobar branches and subsequently into segmental and subsegmental branches. These branches run in parallel to the segmental and subsegmental bronchi (Figure 1). Therefore, the segmental arteries are named according to the bronchopulmonary segment they perfuse.

Figure 1.

Angiographic Demonstration of Pulmonary Arterial Circulation

Right Pulmonary Artery

The right upper lobe is supplied by the corresponding 3 segmental arteries (apical - A1, posterior - A2, anterior -A3); right middle lobe is supplied by 2 segmental arteries (lateral - A4, medial - A5); and right lower lobe by 5 segmental arteries (superior - A6, medial basal - A7, anterior basal - A8, lateral basal - A9, and posterior basal - A10). The segmental arteries and their course in an anteroposterior and lateral view are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Antero-posterior and Lateral Representation of Right Pulmonary Artery and Segmental Arteries

The RPA divides into 2 lobar branches, the truncus anterior (TA) (superior trunk) and the pars interlobaris (interlobar artery or inferior branch). The TA branches into two segmental upper lobe arteries (A1 and A3). The A1 courses apically and the A3 courses anteriorly. The pars interlobaris continues toward the hilum first supplying a posterior coursing upper segmental artery (A2) and then two middle lobe arteries (A4 and A5). The middle lobe is an anterior structure and thus the A4 and A5 originate together anteriorly from the pars interlobaris and then the A4 courses laterally and the A5 medially. The pars interlobaris then courses inferiorly as the pars basalis and supplies the lower lobe through five segmental arteries. First the A6 originates which supplies the superior segment of the lower lobe which lies posterior to the middle lobe. The A6 divides into a medial and a lateral sub-segmental branch. Subsequently, the anteromedial trunk and posterolateral trunk originate which divide into A7/A8 and A9/A10 segmental arteries respectively. The A7 and A8 are well separated in the frontal projection with the A7 coursing medially. The two trunks are well defined in the lateral projection.

Left Pulmonary Artery

The left upper lobe is supplied by 4 corresponding segmental arteries (apical-posterior - A1/A2, anterior - A3, superior lingular - A4, inferior lingular - A5), and the left lower lobe is supplied by 4 segmental arteries (superior - A6, anteromedial basal - A7/A8, lateral basal - A9, and posterior basal - A10). The segmental arteries and their course in an anteroposterior and lateral view are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Antero-posterior and Lateral Representation of Left Pulmonary Artery and Segmental Arteries

The LPA has highly variable branching pattern. There is usually a relatively larger artery supplying the anterior segment of the upper lobe. The apical-posterior (A1/A2) branch courses apically and posteriorly. The A3 branch courses anteriorly and laterally. After this arise the lingular branches (A4 and A5) that arise anteriorly and course laterally in a superior and inferior direction respectively. There is a paucity of medial branches in the anterior areas of the L lung due to the heart. The first lower lobe branch is the A6 which courses posteriorly and has a medial and lateral branch similar to the right side. The A7/A8 is a common segmental artery which courses laterally. The A9 and A10 similar to the right side course posteriorly.

II). Angiographic Technique

Pre-procedure Planning

Pre-procedural assessment of patients includes a review of relevant medical history and allergies, electrocardiogram, recent laboratory tests including hemoglobin, platelet count, renal function, coagulation parameters and pregnancy screening.

Information regarding intracardiac devices such as pacemakers, inferior vena cava (IVC) filters and history of prior internal jugular (IJ) or femoral vein occlusive disease as well as superior vena cava (SVC) or IVC stenoses should be obtained. Any prior investigations such as transthoracic echocardiogram, CTPA or V/Q scans need to be reviewed in detail to compare with the angiogram findings. Presence of a left bundle branch block (LBBB) should alert the provider to the possibility of complete heart block during the procedure. For a diagnostic pulmonary angiogram, interruption of therapeutic anticoagulation is preferred but not absolutely necessary. Most patients will receive local or light conscious sedation during the procedure. Care should be taken to avoid deep sedation so that the patient can comply with breath holding during the procedure. Patients presenting for pulmonary angiograms often have tenuous hemodynamic status and need close hemodynamic and electrocardiographic monitoring.

Vascular Access

The right IJ vein is the preferred approach as it serves as a smoother course for right heart catheterization using standard balloon tipped, flow-directed catheters especially with a dilated right heart. (3) It also obviates the need for a recumbent position after catheterization. In cases where the right IJ cannot be used, the left IJ or either common femoral vein is an alternate approach; the right femoral vein has a relatively straighter course. Use of ultrasound guidance is paramount to exclude thrombosis of the access vein and facilitate safe access. A 7 or 8 Fr introducer sheath is preferable.

Equipment

Obtaining high quality and safe angiograms requires the use of catheters with multiple-side hole which can allow for power injections. Several options exist such as the standard Berman catheter (Teleflex Inc. Wayne, PA), standard straight and curved pigtail shaped catheters or specialized pulmonary catheters such as the Grollman catheter (Cook Inc. Bloomington, IN). The standard Berman catheter (7F 90 cm, max flow rate 24 cc/sec at 700 psi) is a balloon-tipped, end-capped pressure-rated catheter that facilitates easy flow-directed advancement from the right heart into the PA. (3) The presence of an end cap provides protection of distal pulmonary vasculature from iatrogenic damage particularly during high pressure contrast injections. Similarly, a high flow straight or angled (preferable) pigtail can be used. The Grollman catheter (6.7F 100 cm, max flow rate 27 cc/sec at 765 psi) is another alternative which has a 90° curve 3 cm proximal to the pigtail curve. End-hole Swan Ganz catheters should be avoided as they are not compatible with high pressure injections.

III). Approach

Catheter Position

The standard Berman catheter balloon can be advanced from the right IJ similar to ‘floating’ a Swan Ganz catheter. The balloon is inflated in the SVC and when advanced the catheter should traverse the RV with ease and preferentially reach the RPA. When approaching from the femoral vein the balloon can be inflated in the common iliac vein. Clockwise rotation of the catheter as it traverses the tricuspid valve will assist in advancement to the pulmonary artery. Deep inspiration may facilitate catheter entry into the MPA. Alternatively, a loop can be formed in the RA by curving the tip of the catheter against the lateral right atrial wall or by engaging in the hepatic vein ostium. This maneuver maybe helpful with a dilated RV. Catheter advancement should be done under continuous pressure wave monitoring. For instance, the catheter can enter the CS when advancing from the IJ or enter the left atrium via a patent foramen ovale (PFO) or atrial septal defect (ASD). The absence of a transition to RV tracing should alert the operator. A hand injection of contrast can also confirm the catheter path.

The curved pigtail catheter or the Grollman catheter can be advanced over wire until the IVC and then advanced without wire across the tricuspid valve. A counterclockwise rotation will help direct it toward the MPA. In challenging situations, the pulmonary artery can be catheterized using a conventional balloon flotation catheter and exchanged for a pigtail catheter over wire. In most catheterizations the catheter will preferentially enter the RPA. To cannulate the LPA, in case of a pigtail shaped catheter, it can be withdrawn into the MPA and redirected in a superior direction to enter the LPA. If unable to, the shaft of the pigtail in the MPA can be stiffened using the proximal end of an 0.035 wire to allow cannulation of the LPA. A similar maneuver can be used with the Berman catheter as well. Once the Berman catheter is in position the balloon is taken down in preparation for the angiogram.

To image the RPA and branches the angiographic catheter should be positioned beyond the origin of the truncus arteriosus and into the interlobar artery. The catheter in this position has reduced recoil. The middle and lower lobes are imaged first followed quickly by the refluxing contrast opacifying the upper lobe. To image the LPA and branches the catheter is positioned beyond the point where the LPA begins to course inferiorly. In either lung the catheter in position should not have excessive motion with the cardiac cycle in which case the catheter can be advanced a few cm. On the other hand, care should be taken that the catheter is not immobile which may suggest engagement into a clot/obstruction or a deep position of the catheter, in which case the catheter can be withdrawn a few cm. Further, the position of the catheter should be optimized to avoid contrast spillover to the contralateral lung which can compromise image quality, especially for lateral projections.

Patient Position

The patient should preferably be in a supine position with arms raised above shoulder level with hands clasped behind head. This is especially important for high body mass index (BMI) patients or for any patient if lateral (90o) projections are obtained. It is important to ensure that the patient is both comfortable in this position as well able to perform an adequate breath hold for imaging which is essential for optimal angiography quality. An evaluation of the breath hold should be conducted under fluoroscopy prior to obtaining DSA images. In addition, the catheter’s position with deep inspiration can also be observed and adjustments made. If the patient is unable to hold their breath, then a cine-angiography should be obtained instead of digital subtraction angiography (DSA) which although sub-optimal but will provide interpretable information.

Contrast Injection

Contrast is diluted with saline at a 3:1 dilution to reduce contrast amount. Contrast is delivered typically through a power injector at 18–20 cc/sec for 2.5 seconds at a minimum of 600 psi. The flow rate and volume should be reduced in cases of severely reduced cardiac output or extensive CTEPH burden to 15 cc/sec for 2 seconds. For significant PH but moderate CTEPH disease burden, reduce flow rate to 15 cc/sec to minimize hemodynamic consequences, but the duration can be extended to 2.5 seconds so the pulmonary vasculature is filled adequately. A test injection with 5–10 ml can allow the operator to gauge the extent of proximal CTEPH and antegrade flow through the vessel and calibrate the contrast settings. Ang et. al. have suggested contrast settings based on body size, cardiac index and disease severity.(3)

Angiographic Projections

Angiograms are obtained using DSA. Two orthogonal projections should be obtained for comprehensive interpretation of all pulmonary segmental anatomy. We suggest for the R lung RAO 30 o (frontal projection) and LAO 40 o (lateral projection) (Figure 4) and for the L lung LAO 40 o (frontal projection) and RAO 50 o (lateral projection). Alternatively, for the R lung, a straight anterior-posterior (AP) and LAO 90 o can be used (3) (Figure 5). A straight projection should not be taken of the L lung to avoid overlap from the mediastinum. Optimization of views should be based on individual anatomy. Imaging should be continued beyond arterial system opacification and until the pulmonary venous system fills (levophase), as this is important for a complete assessment. (Figure 6) Collimate in both axes to maximize the lung fields. Biplane angiography can help greatly reduce contrast volume and radiation exposure, however, it may not be available at many centers. Digital processing settings should be optimized for optimal brightness and contrast and reduce artifact. Different angiographic systems may have preset optimized settings for pulmonary angiograms.

Figure 4.

Angiographic Projections- Frontal and Lateral Views of Right Pulmonary Vasculature

Figure 5.

Angiographic Projections – Frontal and Lateral Views of the Left Pulmonary Vasculature

Figure 6.

Frontal and Lateral Angiograms of the Right Lung showing the Levophase

IV). Imaging

Angiographic Patterns of CTEPH

Angiography findings in CTEPH can involve the main PA and lobar arteries (proximal disease) or involve the segmental and sub-segmental arteries (distal disease). Proximal disease imaging findings can also include filling defects which suggest relatively acute emboli which can be seen in CTEPH patients. The remainder of the lesions, similar to that seen in distal disease, are bands or ring like stenoses, web like lesions, sub-total occlusions and total occlusions/pouch defects (Figure 7).(4)

Figure 7.

Frontal and Lateral Angiograms of the Right Lung in a patient with CTEPH showing common lesion morphologies

An understanding of the perfusion zones and respective segmental arteries (Figures 8 and 9) is helpful to define the distribution of disease pathology and identify involved vessels to assist in planning catheter-based interventions. To avoid missing total occlusions careful counting of major vessels is recommended, but natural variation in anatomy can complicate vessel origin identification.(3) It is often helpful to look at the distal lung perfusion on the angiograms and in the areas with poor perfusion follow backwards centrally to identify lesions. It is critical to obtain imaging until the levophase. Reduced venous return in a particular segmental territory raises the suspicion of a corresponding segmental arterial stenosis. Sometimes web like lesions are not clearly apparent on a non-selective angiogram and the venous return helps indirectly identify these lesions. It is also important to complement the angiogram with CTA and V/Q scan information. V/Q scans will typically report the areas with reduced perfusion on the basis of involved bronchopulmonary segments.

Figure 8:

Perfusion zones of the right lung in anteroposterior and lateral views

Figure 9:

Perfusion zones of the left lung in anteroposterior and lateral views

Selective angiograms of segmental arteries taken during balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) demonstrate the presence and characteristics of CTEPH lesions with greater definition. However, these are typically obtained after the decision for BPA is made. In later articles in this issue selective angiograms will be discussed. A high quality non-selective pulmonary angiogram following the above suggestions is sufficient in most cases to both make the diagnosis and assess candidacy for invasive therapies.

Angiographic Patterns of Non-Thromboembolic Pulmonary Artery Diseases

Although this angiogram review is focused on imaging in CTEPH, in practice patients may present with undifferentiated dyspnea and no prior pulmonary vascular diagnoses. Thus is it remains important to be able to identify on pulmonary angiography patterns of non-thromboembolic pulmonary artery disease which are summarized in the figure below (Table 1, Figure 10). Other pulmonary arterial conditions that are visible on coronary and not pulmonary arteriograms include coronary artery to pulmonary artery fistulae and anomalous coronaries originating from pulmonary artery etc.

Table 1.

Summary of Angiographic Patterns of Non-Thromboembolic Pulmonary Artery Diseases on Pulmonary Angiograms

| Disease Process | Angiographic Pattern |

|---|---|

| Main Pulmonary artery stenosis | Pulmonary artery narrowing. Pressure gradient on catheterization. |

| Pulmonary artery aneurysm | Focal saccular or fusiform pulmonary arterial dilation with a wide neck |

| Pulmonary arteritis | Distal pulmonary artery stenoses or occlusions – can mimic CTEPH |

| Pulmonary artery neoplasms | Localized stenosis with irregular margins – can mimic CTEPH |

| Pulmonary artery agenesis | Absence of the right or left pulmonary artery with an intact main pulmonary artery |

| Pulmonary artery sling | Origin of the left pulmonary artery from the right pulmonary artery, coursing between the trachea and esophagus |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | Patent communication between descending aorta and pulmonary artery. Can be seen as negative contrast but seen better on aortograms. |

| Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation and fistula | Abnormal direct communication between the branches of the pulmonary artery and vein in conditions like hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. |

| Atrial Septal Defect | Communication visualized between left and right atrium during levophase |

| Partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection | One or more pulmonary veins draining into the right atrium during levophase |

| Pulmonary vein stenosis | Stenosis of one or more pulmonary veins as they drain into the left atrium in the levophase |

Figure 10.

Angiographic Examples of Non-Thromboembolic Pulmonary Artery Diseases

Summary

Invasive angiography remains a valuable technique in the diagnosis and management of numerous pulmonary thromboembolic diseases. Components of IPA methodology include optimal patient positioning, vascular access, catheter selections, angiographic positioning, contrast settings, recognition of angiographic patterns of common thromboembolic and non-thromboembolic conditions.

Key Points.

Proper equipment, catheter position, contrast settings and image acquisition technique can optimize pulmonary angiogram quality

Providing clear patient instruction during the procedure can improve angiographic image acquisition

Reviewing and complementing information from previous non-invasive imaging improves interpretation of pulmonary angiograms

Synopsis.

Invasive or selective pulmonary angiography has historically been used as the gold standard diagnostic test for the evaluation of a wide array of pulmonary arterial conditions, most commonly pulmonary thromboembolic diseases. With the emergence of various non-invasive imaging modalities, the role of invasive pulmonary angiography (IPA) is shifting to the assistance of advanced pharmaco-mechanical therapies for conditions. We review the pulmonary vascular anatomy, step-by-step performance and interpretation of IPA.

Clinical Care Points.

Proper equipment, catheter position, contrast settings and image acquisition technique can optimize pulmonary angiogram quality

Providing clear patient instruction during the procedure can improve angiographic image acquisition

Reviewing and complementing information from previous non-invasive imaging improves interpretation of pulmonary angiograms

Disclosures

Dr. Murugiah received support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (under award K08HL157727).

Contributor Information

Ju Young Bae, Section of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale New Haven Health Bridgeport Hospital, Bridgeport, CT, United States

Karthik Murugiah, Section of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Yale New Haven Hospital, New Haven, CT, United States.

References

- 1.Sasahara AA, Stein M, Simon M, Littmann D. Pulmonary angiography in the diagnosis of thromboembolic disease. N Engl J Med 1964;270:1075–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kandathil A, Chamarthy M. Pulmonary vascular anatomy & anatomical variants. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2018;8:201–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang L, McDivit Mizzell A, Daniels LB, Ben-Yehuda O, Mahmud E. Optimal Technique for Performing Invasive Pulmonary Angiography for Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Disease. J Invasive Cardiol 2019;31:E211–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawakami T, Ogawa A, Miyaji K et al. Novel Angiographic Classification of Each Vascular Lesion in Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension Based on Selective Angiogram and Results of Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]