Abstract

Acanthamoeba species are free-living amoebae those are widely distributed in the environment. They feed on various microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and algae. Although majority of the microbes phagocytosed by Acanthamoeba spp. are digested, some pathogenic bacteria thrive within them. Here, we identified the roles of 3 phagocytosis-associated genes (ACA1_077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1) in A. castellanii. These 3 genes were upregulated after the ingestion of Escherichia coli. However, after the ingestion of Legionella pneumophila, the expression of these 3 genes was not altered after the consumption of L. pneumophila. Furthermore, A. castellanii transfected with small interfering RNS (siRNA) targeting the 3 phagocytosis-associated genes failed to digest phagocytized E. coli. Silencing of ACA1_077100 disabled phagosome formation in the E. coli-ingesting A. castellanii. Alternatively, silencing of ACA1_175060 enabled phagosome formation; however, phagolysosome formation was inhibited. Moreover, suppression of AFD36229.1 expression prevented E. coli digestion and consequently led to the rupturing of A. castellanii. Our results demonstrated that the ACA1_077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1 genes of Acanthamoeba played crucial roles not only in the formation of phagosome and phagolysosome but also in the digestion of E. coli.

Keywords: Acanthamoeba, gene expression, gene silencing, phagocytosis, phagolysosome, phagosome, siRNA

Introduction

Acanthamoeba species are free-living protist pathogens that cause Acanthamoeba keratitis and granulomatous amoebic encephalitis [1]. Acanthamoeba feed on a wide range of microorganisms including bacteria, algae, viruses, and other protists; however, these protozoa can serve as a reservoir host [2]. To date, several endosymbiotic relationships between clinically important pathogens and amoebae have been reported, with the survival of Legionella pneumophila on Acanthamoeba being a prominent example [3–5]. The intracellular survival of L. pneumophila, Legionella-containing vacuole, the defective organelle transport/intracellular multiplication (Dot/Icm) type IV system, and several other effectors of Legionella have been identified and their roles have been studied [6–8]. However, the genes associated with phagocytosis and endosymbiosis in Acanthamoeba have not been extensively studied.

In our previous study, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) acquired from A. castellanii during the phagocytosis of E. coli or endosymbiosis with L. pneumophila were compared [9]. Based on the findings of this previous study, it was hypothesized that the genes upregulated in E. coli-ingested Acanthamoeba were involved in the phagocytosis of Acanthamoeba and those upregulated in L. pneumophila-ingested Acanthamoeba were involved in promoting its survival and endosymbiosis within Acanthamoeba. Among the upregulated genes in L. pneumophila-ingested A. castellanii, ACA1_114460, ACA1_091500, and ACA1_362260 were found to be integral to the formation of excretory vesicles containing L. pneumophila along with the lysosomal colocalization with the vesicles [10].

While elucidating the mechanism of action for these survival and lysosome colocalization-associated genes would be beneficial, we identified another set of genes with interesting expression patterns which became the focal point of the present study. Specifically, we identified several genes that were upregulated in E. coli-ingesting Acanthamoeba whose expressions were upregulated following E. coli ingestion, but remain unaffected upon L. pneumophila ingestion. Given this finding, we anticipated that these genes are essential for phagocytosis and L. pneumophila somehow ensures that the expression of E. coli-induced genes remains near basal levels to prolong their survival within the host. To confirm this hypothesis, we selected 3 genes that meet these criteria (ACA1_077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1) in the present study, and investigated their potential involvement in phagocytosis. Our findings revealed that phagocytosis inhibition could be a mechanism utilized by L. pneumophila to promote its growth and survival in host cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and bacterial infection

Acanthamoeba castellanii (ATCC 30868 and ATCC 30011) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured axenically in peptone-yeast-glucose (PYG) medium at 25°C. Escherichia coli DH5α (Enzynomics, Seoul, Korea) was cultured in tryptone-yeast-NaCl (LB) media at 37°C using a shaking incubator. Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia-1 (ATCC 33152) was cultured on a buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE) agar plate at 37°C with 5% CO2. A. castellanii was infected by E. coli and L. pneumophila as previously described [11]. Briefly, E. coli and L. pneumophila were diluted in PBS until the OD600 absorbance reading reached 1 which corresponds to 109 CFU/ml [12]. Next, 1×107 of Acanthamoeba were incubated with 1 ml of E. coli and L. pneumophila suspension at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 1 h. After incubation, Acanthamoeba was washed with Page’s amoeba saline (PAS) and incubated with new PYG media containing 100 μg/ml of gentamicin for 2 h to kill extracellular bacteria. Acanthamoeba infected with E. coli (A+E) and L. pneumophila (A+L) were washed with PAS twice and incubated in fresh PYG media for 12 h, 25°C.

Gene expression analysis by real-time PCR

Target gene expressions were determined by real-time PCR analysis. The total RNA was purified using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and the cDNA was synthesized using a RevertAid first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was conducted using a Magnetic Induction Cycler PCR machine (PhileKorea, Seoul, Korea) as previously described [13] which included preincubation at 95°C for 1 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, and 60°C for 30 sec. All reaction mixtures were made using a Luna Universal qPCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) with different sense and antisense primers (Supplementary Table S1).

Gene silencing

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting ACA1_077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1 of Acanthamoeba were synthesized by Bioneer Inc (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea), based on their cDNA sequences (Supplementary Table S2). The siRNA (final concentration of 100 nM) was transfected into live Acanthamoeba trophozoites at a cell density of 4×105 cells using the Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Successful transfection of siRNA was confirmed by observing cells under a fluorescent microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Observation of phagosomes and phagolysosomes

Phagosomes and phagolysosomes of A. castellanii containing E. coli were observed with Giemsa and LysoTracker staining. Acanthamoeba was subjected to siRNA transfection (siRNA-A), followed by E. coli (siRNA-A+E) infection as aforementioned. For Giemsa staining assays, cells were fixed with methanol for 5 min and stained with Giemsa solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) for 10 min. For the LysoTracker stain, cells were stained with 50 μM LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h. Stained cells were washed with PBS, and observed under a fluorescent microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±SD from three independent experiments. Student’s t-tests were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8 (Dotmatics, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance between the means of groups was denoted using an asterisk. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, and ****P<0.0001).

Results

Identification of up-regulated genes in Acanthamoeba feeding on E. coli

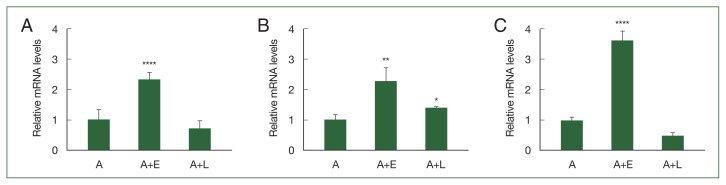

Based on our previous study involving DEGs, 3 genes (ACA1_077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1) that were upregulated in A. castellanii after E. coli ingestion but unchanged after L. pneumophila ingestion were selected in the present study. To confirm their expression levels, real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed using gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S1). As depicted in Fig. 1A. ACA1_077100 was upregulated in Acanthamoeba that ingested E. coli (A+E) but not in Acanthamoeba that ingested L. pneumophila (A+L). Furthermore, the expression patterns of ACA1_175060 and AFD36229.1 were similar to those of ACA1_077100 in both A+E and A+L (Fig. 1B, C).

Fig. 1.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of 3 differentially expressed genes in Acanthamoeba. A. castellanii ingested E. coli (A+E) and L. pneumophila (A+L) for 12 h, and the gene expression ACA1_077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1 was determined by RT-PCR. (A) ACA1_077100, (B) ACA1_175060, and (C) AFD36229.1. Data are expressed as mean±SD from 3 individual experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance compared to the Acanthamoeba control (A), as determined by Student’s t-test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001).

siRNA-mediated gene silencing

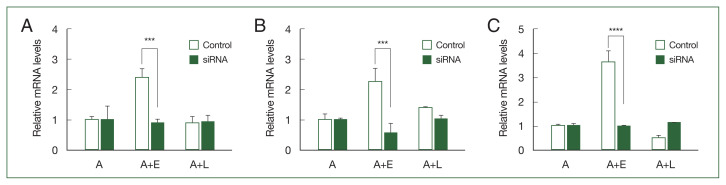

To investigate the phagocytic roles of ACA1_077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1 within A. castellanii, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) specific for each gene (Supplementary Table S2) were synthesized. The gene silencing effects of siRNAs were validated using RT-PCR (Fig. 2). The transfection of ACA1_077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1 sequence-specific siRNAs significantly suppressed the expression of the respective mRNAs in A. castellanii during E. coli ingestion (Fig. 2A–C).

Fig. 2.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of the 3 differentially expressed genes in Acanthamoeba after transfection of siRNA. A. castellanii were transfected with siRNA and coincubated with either E. coli (A+E) or L. pneumophila (A+L) for 12 h. siRNA-mediated gene silencing was confirmed by RT-PCR. (A) ACA1_077100, (B) ACA1_175060, and (C) AFD36229.1. Data are expressed as mean ±SD from 3 individual experiments. Asterisks indicate that the means are significantly different compared to untransfected Acanthamoeba (***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001).

Effect of gene silencing on the phagosome formation

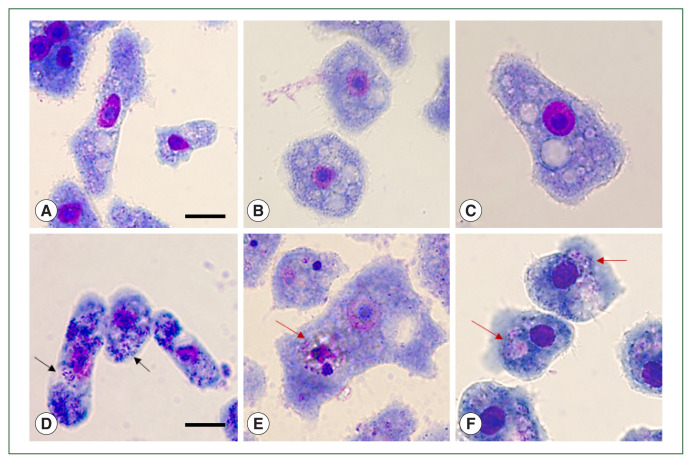

To visually confirm the effects of ACA1_077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1 gene silencing in A+E, Giemsa staining was performed (Fig. 3). E. coli digestion was observed in the A+E control group because none of the 3 genes was downregulated (Fig. 3B). However, the suppression of ACA1_077100 in A+E inhibited the formation of phagosome-like structures, with E. coli dissemination occurring in the cytosols of Acanthamoeba (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, the silencing of ACA1_175060 and AFD36229.1 in A+E resulted in the formation of phagosomes containing E. coli, however, the phagocytized E. coli remained undigested in the phagosomes (Fig. 3E, F). These phenomena were not observed in the Acanthamoeba control group (Fig. 3A) and siRNA-transfected Acanthamoeba control group (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

siRNA-transfected Acanthamoeba containing E. coli. Acanthamoeba that did and did not undergo siRNA transfection were cultured with E. coli for 12 h. Those containing E. coli were stained with Giemsa staining solution. (A) A. castellanii control, (B) A. castellanii containing E. coli, (C) siRNA-transfected A. castellanii control, (D) ACA1_077100 siRNA-transfected A. castellanii containing E. coli, (E) ACA1_175060 siRNA-transfected A. castellanii containing E. coli, and (F) AFD36229.1 siRNA-transfected A. castellanii containing E. coli. Black arrows: E. coli in the cytoplasm of Acanthamoeba. Red arrows: E. coli in the phagosomes of Acanthamoeba. Bar=10 μm.

Effect of gene silencing on the phagolysosome formation and E. coli digestion

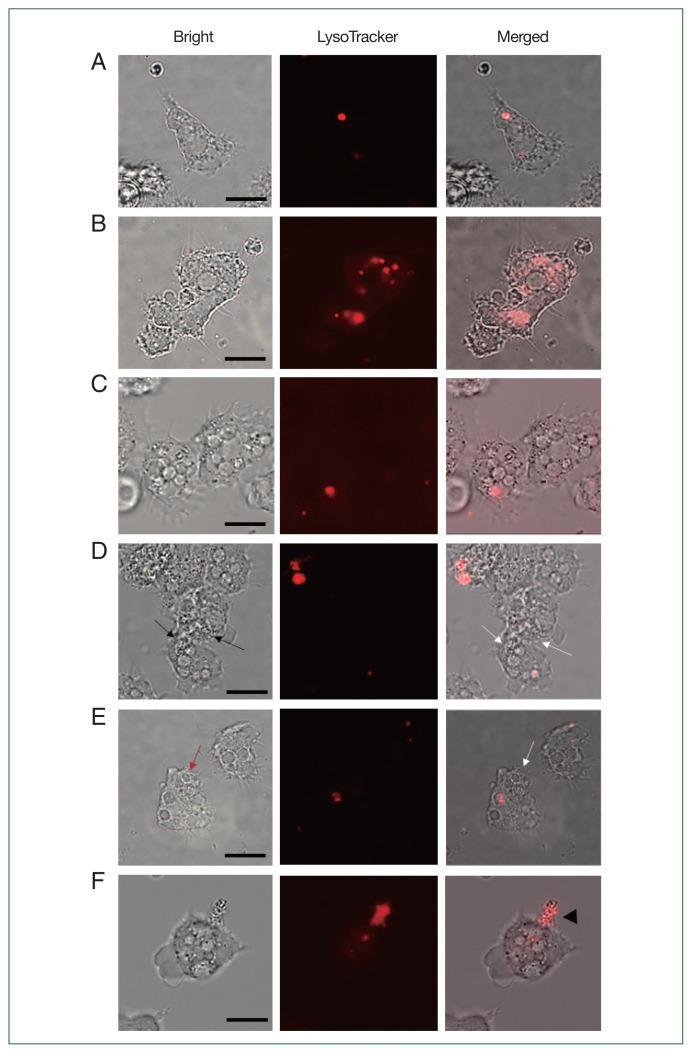

To verify whether the failure of E. coli digestion in the siRNA-transfected Acanthamoeba was related to lysosomal acidifications, LysoTracker Red DNA-99 staining and fluorescent microscopy were conducted (Fig. 4). Phagolysosome-like structures were barely detected in uninfected Acanthamoeba (Fig. 4A) but were prevalent in A+E (Fig. 4B). Similar to the uninfected control, siRNA transfection in Acanthamoeba did not affect LysoTracker staining (Fig. 4C). However, LysoTracker-stained intracellular organelles were not observed in ACA1_077100-silenced Acanthamoeba (Fig. 4D). Lysosome fusion could not occur because Acanthamoeba did not form E. coli-containing phagosomes, and E. coli was distributed in the cytosols of Acanthamoeba (Fig. 4D). These findings suggested that the ACA1_ 077100 gene in A. castellanii was involved in the formation of the phagosomal membrane during E. coli ingestion. Alternatively, silencing of ACA1_175060 led to the formation of E. coli-containing phagosomes (Fig. 4E) but failed to form phagolysosomes (Fig. 4E). The ACA1_175060 gene in A. castellanii was believed to play a role in the formation of the phagolysosome within Acanthamoeba. Fig. 4F shows the leakage of proliferating E. coli out of AFD36229.1-silenced Acanthamoeba, possibly indicating the rupturing of Acanthamoeba. Bacterial digestion did not occur, despite the fusion of lysosomes with E. coli-containing phagosomes, leading to the exponential growth of E. coli and subsequent bursting of Acanthamoeba. These findings suggest that AFD36229.1 is crucial for the phagosomal digestion of microbial contents in Acanthamoeba.

Fig. 4.

LysoTracker staining of siRNA-transfected Acanthamoeba containing E. coli. The Acanthamoeba that did and did not undergo siRNA transfection were allowed to ingest E. coli for 12 h, and those containing E. coli were stained with LysoTracker. (A) A. castellanii control, (B) A. castellanii containing E. coli, (C) siRNA-transfected A. castellanii control, (D) ACA1_077100 siRNA-transfected A. castellanii containing E. coli, (E) ACA1_175060 siRNA-transfected A. castellanii containing E. coli, and (F) AFD36229.1 siRNA-transfected A. castellanii containing E. coli. Black arrows, E. coli in the cytoplasm of Acanthamoeba. Red arrow, E. coli in the phagosomes of Acanthamoeba; White arrows, E. coli in Acanthamoeba cytoplasm or phagosomes without lysosomes. Black arrowhead, E. coli that burst out of Acanthamoeba. Bar=10 μm.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the role of 3 genes (ACA1_077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1) upregulated in A. castellanii feeding on E. coli. We observed that the ACA1_ 077100 gene in Acanthamoeba was involved in the formation of the phagosomal membrane during E. coli ingestion. We also observed that the ACA1_175060 gene played a role in the formation of the phagolysosome within Acanthamoeba, and the AFD36229.1 gene is crucial for the phagosomal digestion of bacteria in Acanthamoeba.

The 3 upregulated genes ACA1_077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1 observed in A+E were identified to be a Rab1/RabD family small GTPase (96% sequence identity to that of Acanthamoeba spp.), a vacuolar proton ATPase (99% sequence identity to that of Acanthamoeba spp.), and a cyst-specific cysteine proteinase (100% sequence identity to that of Acanthamoeba spp.), respectively (Table 1). The Rab family protein is a member of the Ras superfamily of small G proteins; moreover, Rab1/RabD GTPase regulates the transport of proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi bodies, membrane tethering, and vesicle fusion in plants and humans [14,15]. Vacuolar ATPase is a proton pump responsible for controlling the intracellular and extracellular pH of cells [16], and the cyst-specific cysteine proteinase plays an important role in the autophagosomal degradation of mitochondria during A. castellanii encystation [17].

Several methods are frequently employed to detect phagosome, as well as phagolysosome formation. Giemsa staining has been traditionally used to observe such phenomena in numerous cell lines [18]. However, due to monochrome staining, accurately differentiating between amoebal mitochondria from E. coli was somewhat problematic. To accurately observe phagosomes or phagolysosomes, LysoTracker reagents were used in the present study. LysoTracker reagents are frequently used to stain acidic cellular components, such as phagolysosomes and autophagosomes, and it is suitable for confirming whether the bacterial aggregates observed under the microscope are truly phagolysosomes. In the present study, siRNA-treated Acanthamoeba demonstrated impaired phagocytic function. Based on this finding, we reasoned that these genes could be associated with phagocytosis. Additional studies, such as gain of function studies investigating the overexpression of ACA1_ 077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1 genes in A. castellanii are highly desired. Specifically, exposing A. castellanii overexpressing these genes to L. pneumophila and subsequently assessing whether phagocytosis of these pathogenic bacteria occurs within the amoeba is worth investigating. Findings from such studies could confirm that L. pneumophila downregulates the expression of several genes associated with phagocytosis through an unknown mechanism to prevent their degradation in phagosomes.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated the roles of ACA1_077100, ACA1_175060, and AFD36229.1 genes in A. castellanii during phagocytosis of E. coli. These upregulated genes in the A+E were heavily involved in phagosome formation, phagolysosomal fusing, and digestion of phagocytized microbial contents. However, these genes were not upregulated in Acanthamoeba that consumed L. pneumophila. This suggested that the expression of these genes was inhibited by Legionella for its survival within Acanthamoeba. Confirming L. pneumophila digestion within Acanthamoeba when these gene are overexpressed would imply that the survival of intracellular pathogen such as Legionella and Mycobacterium spp. is inhibited and thereby contribute to preventing the bacetrial infection with Acanthamoeba.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1F1A1068719).

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Kong HH

Data curation: Kim MJ, Moon EK, Jo HJ, Quan FS, Kong HH

Funding acquisition: Kong HH

Investigation: Kim MJ, Moon EK, Jo HJ

Methodology: Kim MJ, Moon EK, Jo HJ, Quan FS

Writing – original draft: Moon EK

Writing – review & editing: Kim MJ, Jo HJ, Quan FS, Kong HH

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.

Supplementary Information

References

- 1.Siddiqui R, Khan NA. Biology and pathogenesis of Acanthamoeba. . Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diehl MLN, Paes J, Rott MB. Genotype distribution of Acanthamoeba in keratitis: a systematic review. Parasitol Res. 2021;120(9):3051–3063. doi: 10.1007/s00436-021-07261-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iovieno A, Ledee DR, Miller D, Alfonso EC. Detection of bacterial endosymbionts in clinical acanthamoeba isolates. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(3):445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheikl U, Sommer R, Kirschner A, Rameder A, Schrammel B, et al. Free-living amoebae (FLA) co-occurring with legionellae in industrial waters. Eur J Protistol. 2014;50(4):422–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greub G, Raoult D. Microorganisms resistant to free-living amoebae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(2):413–433. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.2.413-433.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nora T, Lomma M, Gomez-Valero L, Buchrieser C. Molecular mimicry: an important virulence strategy employed by Legionella pneumophila to subvert host functions. Future Microbiol. 2009;4(6):691–701. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segal G, Feldman M, Zusman T. The Icm/Dot type-IV secretion systems of Legionella pneumophila and Coxiella burnetii . FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29(1):65–81. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiu J, Luo ZQ. Effector translocation by the Legionella Dot/Icm type IV secretion system. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013;376:103–115. doi: 10.1007/82_2013_345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moon EK, Kim MJ, Lee HA, Quan FS, Kong HH. Comparative analysis of differentially expressed genes in Acanthamoeba after ingestion of Legionella pneumophila and Escherichia coli. . Exp Parasitol. 2022;232:108188. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2021.108188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim MJ, Moon EK, Jo HJ, Quan FS, Kong HH. Identifying the function of genes involved in excreted vesicle formation in Acanthamoeba castellanii containing Legionella pneumophila. . Parasit Vectors. 2023;16(1):215. doi: 10.1186/s13071-023-05824-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mou Q, Leung PHM. Differential expression of virulence genes in Legionella pneumophila growing in Acanthamoeba and human monocytes. Virulence. 2018;9(1):185–196. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2017.1373925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harding CR, Schroeder GN, Reynolds S, Kosta A, Collins JW, et al. Legionella pneumophila pathogenesis in the Galleria mellonella infection model. Infect Immun. 2012;80(8):2780–2790. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00510-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon EK, Kim MJ, Lee HA, Quan FS, Kong HH. Comparative analysis of differentially expressed genes in Acanthamoeba after ingestion of Legionella pneumophila and Escherichia coli. . Exp Parasitol. 2022;232:108188. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2021.108188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lycett G. The role of Rab GTPases in cell wall metabolism. J Exp Bot. 2008;59(15):4061–4074. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barr FA. Review series: Rab GTPases and membrane identity: causal or inconsequential? J Cell Biol. 2013;202(2):191–199. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201306010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pamarthy S, Kulshrestha A, Katara GK, Beaman KD. The curious case of vacuolar ATPase: regulation of signaling pathways. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0811-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moon EK, Hong Y, Chung DI, Kong HH. Cysteine protease involving in autophagosomal degradation of mitochondria during encystation of Acanthamoeba . Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2012;185(2):121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbett Y, Parapini S, Perego F, Messina V, Delbue S, et al. Phagocytosis and activation of bone marrow-derived macrophages by Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes. Malar J. 2021;20(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03589-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.