Abstract

Magnesium-protoporphyrin chelatase, the first enzyme unique to the (bacterio)chlorophyll-specific branch of the porphyrin biosynthetic pathway, catalyzes the insertion of Mg2+ into protoporphyrin IX. Three genes, designated bchI, -D, and -H, from the strictly anaerobic and obligately phototrophic green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium vibrioforme show a significant level of homology to the magnesium chelatase-encoding genes bchI, -D, and -H and chlI, -D, and -H of Rhodobacter sphaeroides and Synechocystis strain PCC6803, respectively. These three genes were expressed in Escherichia coli; the subsequent purification of overproduced BchI and -H proteins on an Ni2+-agarose affinity column and denaturation of insoluble BchD protein in 6 M urea were required for reconstitution of Mg-chelatase activity in vitro. This work therefore establishes that the magnesium chelatase of C. vibrioforme is similar to the magnesium chelatases of the distantly related bacteria R. sphaeroides and Synechocystis strain PCC6803 with respect to number of subunits and ATP requirement. In addition, reconstitution of an active heterologous magnesium chelatase enzyme complex was obtained by combining the C. vibrioforme BchI and -D proteins and the Synechocystis strain PCC6803 ChlH protein. Furthermore, two versions, with respect to the N-terminal start of the bchI gene product, were expressed in E. coli, yielding ca. 38- and ca. 42-kDa versions of the BchI protein, both of which proved to be active. Western blot analysis of these proteins indicated that two forms of BchI, corresponding to the 38- and the 42-kDa expressed proteins, are also present in C. vibrioforme.

In photosynthetic organisms, the enzyme magnesium-protoporphyrin IX chelatase (Mg-chelatase) catalyzes the insertion of Mg2+ into protoporphyrin IX, the first step unique to the synthesis of (bacterio)chlorophyll. Situated at the branch point of the heme- and (bacterio)chlorophyll-specific parts of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis, Mg-chelatase is believed to have an important regulatory role in channelling intermediates into the (bacterio)chlorophyll-specific branch in response to conditions determining photosynthetic growth. Recently, the genes bchI, -D, and -H of the facultatively anaerobic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides (3) and the homologous genes chlI, -D, and -H of the chlorophyll a-synthesizing cyanobacterium Synechocystis strain PCC6803 (5) have been overexpressed in Escherichia coli. In each case ATP-dependent reconstitution of activity has been achieved in vitro by combining the BchI/ChlI (38 and 42 kDa), BchD/ChlD (60 and 74 kDa), and BchH/ChlH (140 and 150 kDa) overexpressed gene products, thereby demonstrating that the Mg-chelatase enzyme complexes of the two bacteria are encoded by these genes.

Several indications of functional properties of Mg-chelatase subunits have been reported. Spectofluorometric analysis has shown that during expression of the R. sphaeroides bchH gene in E. coli, protoporphyrin IX accumulates, probably because the overexpressed BchH protein binds protoporphyrin IX (3). In support of this assumption, Willows et al. (29) have reported that purified R. sphaeroides monomeric BchH protein binds protoporphyrin IX in an approximate molar ratio of 1:1 (29).

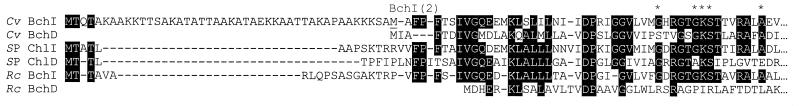

In pea (Pisum sativum) it has been demonstrated that two crude protein fractions of broken chloroplasts confer Mg-chelatase activity when combined and that ATP is absolutely required for both activation (seen as a 6-min lag period preceding activity) of the proteins involved and the chelation of Mg2+ into protoporphyrin IX (26–28). A similar lag period can be eliminated by preincubation of purified R. sphaeroides BchI protein with partially purified BchD protein in the presence of ATP and Mg2+, suggesting that a ternary complex between BchI and -D and Mg2+-ATP is formed during the activation (29). A phosphate-binding motif (GX4GKSX6A) common to a number of ATP/GTP-binding proteins (13) is found near the N terminus in the products of all genes homologous to the Rhodobacter capsulatus bchI gene of prokaryotic (1, 5, 18) as well as eukaryotic (6, 9, 14, 17) origin. The deduced amino acid sequences of the proteins BchD of R. capsulatus (1), BchD of Chlorobium vibrioforme (19), and ChlD of Synechocystis strain PCC6803 (5) all contain a short and very distinct proline-rich stretch, situated approximately in the middle, which may divide the protein into two major domains. Furthermore, the N-terminal halves of the three deduced “D” proteins display significant intraspecies amino acid identity to the “I” proteins (5, 19), suggesting that the ancestral D gene has arisen from a gene duplication of the I gene.

We have previously reported that a ca. 15-kbp region (18, 19) of the genome of C. vibrioforme includes three open reading frames (ORFs), designated bchI, -D, and -H, encoding proteins with deduced molecular masses of 38, 67, and 145 kDa, respectively. The three ORFs display significant homology to the Mg-chelatase-encoding genes of R. capsulatus and Synechocystis strain PCC6803, and the three genes are homologous to the putative Mg-chelatase-encoding genes of higher plants.

In the present work the genes bchI, -D, and -H of C. vibrioforme f. sp. thiosulfatophilum NCIB 8327 have been expressed separately in E. coli, and evidence showing that the BchI, -D, and -H polypeptides are required for reconstitution of Mg-chelatase activity in vitro is presented. In addition, reconstitution of an active heterologous Mg-chelatase enzyme complex consisting of the C. vibrioforme BchI and -D proteins and the Synechocystis strain PCC6803 ChlH protein is demonstrated. Furthermore, two constructs expressing a ca. 42- and a ca. 38-kDa version of the BchI protein, which were both active in Mg-chelatase assays, have been made. Western blot analysis of protein extracts of C. vibrioforme indicates that two forms of the BchI protein, corresponding to the 42- and 38-kDa versions of the expressed BchI proteins, are indeed present in C. vibrioforme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of pET derivates of the C. vibrioforme bchI, -D, and -H genes.

The primer pairs, which include two possible start codons and the corresponding stop codon of ORFs bchI, -D, and -H, respectively, were designed as follows: PCVI (5′-AACCAAGTGCATATGACCCAGACTG-3′) or PCVI2 (5′-GAAGAAGAGTCATATGGCATTCC-3′) and PCVI3 (5′-CTTGGCCAGATCTATTCCTACAAT-3′), PCVD (5′-CCGAAGTAGCCATATGATAGCAT-3′) and PCVD3′ (5′-ATAAGAGGGGGATCCAGGTAATGA-3′), and PCVH (5′-GGTTCTTAACCATATGTCAGTAG-3′) and PCVH3 (5′-ACGGTCAAGGATCCACTAATCGTC-3′), where underlining designates the restriction sites NdeI, BglII, and BamHI and boldface designates the ATG start codon. These primer pairs were used in PCRs to amplify the ORFs designated bchI, -I(2), -D, and -H, respectively, where 2 designates the shorter of the two ORFs (Fig. 1). Approximately 100 ng of C. vibrioforme f. sp. thiosulfatophilum NCIB 8327 genomic DNA was subjected to amplification by PCR in a total volume of 100 μl containing 1× PCR buffer (Boehringer Mannheim), 1.8 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM four deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 0.2 pM each primer, and 3.5 U of Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Boehringer Mannheim). Cycle parameters were 97°C for 4 min (hot start) and then 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min 30 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 70°C for 2 min (4 min for bchH). PCR products were purified from agarose gels and cloned, by standard procedures (2, 23), in the pET15b vector (22), yielding the constructs pET15b-bchI and -I(2), pET15b-bchD, and pET15b-bchH (Fig. 1). The correctness of the 5′ cloning site for each of the different ORFs was verified by sequence analysis. Sequencing reactions were carried out with the Thermo Sequenase core sequencing kit with 7-deaza-dGTP and run on a Vistra 725 DNA sequenator (Amersham Life Science). Insert-specific oligonucleotide primers were labelled with the 5′ oligonucleotide Texas red labelling kit (Amersham Life Science) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and used together with the Texas red-labelled T7 primer (Amersham Life Science) to sequence the 5′ ends, containing the cloning site, of all pET-derived constructs.

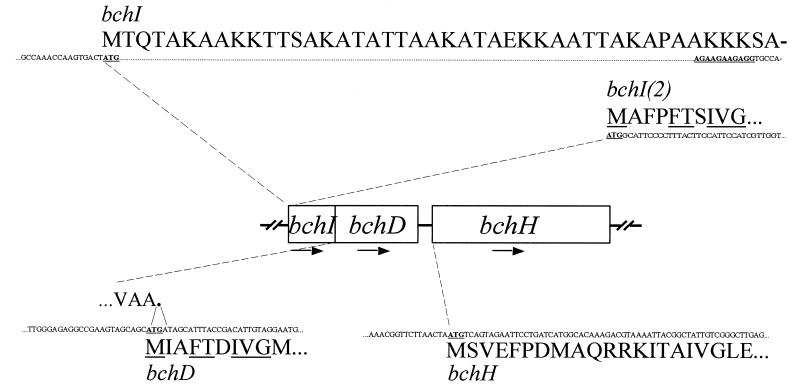

FIG. 1.

N-terminal starts of the constructs designated pET15b-bchI, -I(2), -D, and -H. Underlining and boldface designate the possible ATG start codon(s) and possible ribosome binding sequences, using the consensus motif AGGAGG(N2–10)ATG (1). Note that the stop codon (TGA) of the bchI ORF overlaps the start codon of the bchD ORF. The underlined amino acids designate conserved amino acids within the first eight and nine residues of the N-terminal parts of the deduced BchI(2) and -D proteins.

Expression and partial purification of gene products.

The optimal temperature, with regard to yield of soluble protein, during induction was determined in initial small-scale experiments (10-ml volume) in accordance with pET System Manual (6th ed.) from Novagen (data not shown). In these experiments induction at 30°C for pET15b-bchI and pET15b-bchI(2), 18°C for pET15b-bchD, and 37°C for pET-bchH was found to be optimal (data not shown). However, the construct pET15b-bchD was induced at 30°C and processed as described below.

The pET15b-derived constructs were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) and grown at 25°C in Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml in volumes of 0.4 liter for the bchI- and -D-containing constructs and 3 liters for the bchH-containing constructs until the A600 of the cultures reached 0.6 to 0.8. Gene expression was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside to the cultures at a final concentration of 1 mM. One hour prior to the time of induction, 5-aminolevulinic acid was added at a final concentration of 0.2 mM to cultures of pET15b-bchH. After 6 to 8 h of induction at temperatures found optimal in the small-scale experiments, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the pellets were stored at −20°C until use. His-tag purification of overexpressed BchI, -I(2), and -H proteins on an Ni2+-agarose affinity column was carried out according to the pET System Manual (6th ed.) from Novagen, with the exception that the imidazole concentration in the elution buffer was 0.5 instead of 1 M. One-milliliter fractions with high protein concentrations were pooled (typically 4 to 6 ml) and dialyzed twice against 3 liters of Mg-chelatase buffer (50 mM Tricine [pH 7.9], 0.3 M glycerol) containing 2 mM dithiothreitol at 4°C. BchH protein was additionally dialyzed in the presence of 1 μM protoporphyrin IX and 2 mM MgCl2.

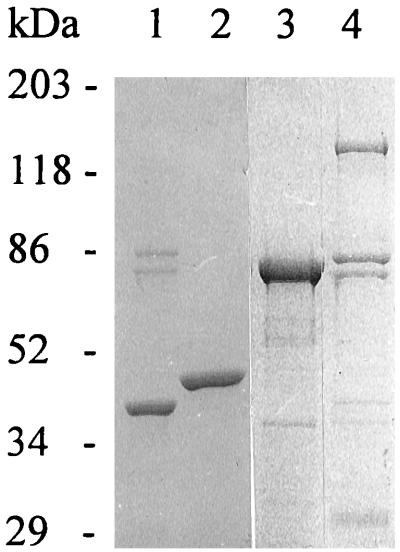

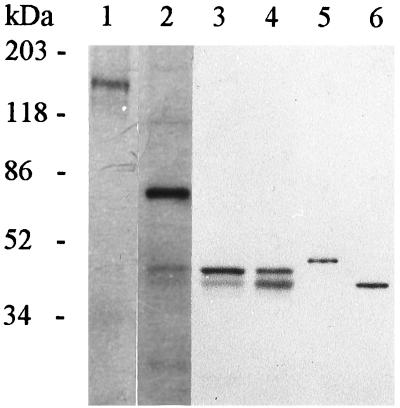

Cell pellets containing BchD protein were dissolved in 10 ml of Mg-chelatase buffer containing 1 mM dithiothreitol and disrupted by sonication in an ice bath. Insoluble protein and cellular debris were pelleted by centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatants were discarded, and the pellets, which by phase-contrast microscopy revealed the presence of inclusion bodies of BchD, were dissolved and incubated overnight at 4°C in Mg-chelatase buffer containing 6 M urea (analytical grade) and 1 mM dithiothreitol. Cellular debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the protein concentration in the supernatant was typically 25 to 30 mg/ml. As judged from sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels, the BchI protein was purified to homogeneity, the BchI(2) and -H proteins were estimated to be >80 and >10% pure, respectively, and the urea-solubilized BchD protein was estimated to be >80 to 90% pure (Fig. 2). The difference in N termini between the BchI and BchI(2) proteins seems to have a decisive effect on the purity of the BchI protein. Two contaminating E. coli-derived proteins, seen as the ca. 80- and 85-kDa bands on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (Fig. 2), were present after His-tag purification of the BchI(2) and -H proteins.

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE of His-tag-purified proteins. Lane 1, BchI(2) (38 kDa); lane 2, BchI (42 kDa); lane 3, BchD (67 kDa); lane 4, BchH (145 kDa). Approximately 0.5 μg of the His-tag-purified or urea-dissolved proteins was loaded onto the gel. The two bands of ca. 80 and 85 kDa present in preparations of BchI(2) and -H proteins are considered to be E. coli-derived contaminants.

SDS-PAGE, protein concentration, and Mg-chelatase assays.

Protein concentrations were estimated with the Bio-Rad Protein Assay reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. SDS-PAGE was carried out and porphyrin solutions were made as described by Laemmli (10) and Gibson et al. (3), respectively. The Mg-chelatase assay mixture contained 20 mM MgCl2, 4 mM ATP, 5 μM protoporphyrin IX, 20 mM phosphocreatine, 5 U of creatine kinase, 1.5 to 2 mM dithiothreitol, protein, and Mg-chelatase buffer adjusted to a total volume of 100 μl. Assay mixtures containing ca. 30 μg of BchI and -D proteins and 60 to 70 μg of BchH protein, deduced from the purity on SDS-polyacrylamide gels following His-tag purification, were incubated at 30°C in the dark for 4 h, the reactions were stopped by addition of 1.9 ml of acetone–H2O–32% NH4OH (80:20:1, vol/vol/vol) and the mixtures were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min. The preparation and use of purified Synechocystis strain PCC6803 subunits will be described elsewhere (7). A fluorescence emission spectrum of the aqueous phase (excitation, 420 nm) of each assay mixture was obtained in a Kontron SFM 25 spectrofluorimeter and recorded at between 550 and 650 nm. The emission at 595 nm was used as a measure of the Mg-protoporphyrin IX formed, which was quantified by integration of the peak area from the fluorescence intensity response of authentic Mg-protoporphyrin IX (Porphyrin Products, Logan, Utah); this was found to be linear in the range of 1 to 500 pmol.

Growth of C. vibrioforme and Western blot analysis.

C. vibrioforme f. sp. thiosulfatophilum NCIB 8327 was grown in 100-ml completely filled screw-capped bottles containing the medium of Sirevåg and Ormerod (25) as described by Rieble et al. (21) under incandescent tungsten lamps at a light intensity of ca. 5,000 lx at 25°C. Cell cultures in the exponential phase were harvested after reaching an optical density at 650 nm of approximately 0.7, and cells of the stationary phase were harvested 2 to 4 h after having reached an optical density at 650 nm of ca. 1.2. For protein extraction, 50 ml of cell culture was pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the pellets were stored at −70°C until use. The pellets were dissolved in 1 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl–2 mM EDTA (pH 8.0)–0.01% Triton X-100, lysozyme at a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml was added, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 30°C and sonicated vigorously in an ice bath until clearing of the suspension. Protein was precipitated by the addition of 5 volumes of acetone–H2O–32% NH4OH (80:20:1, vol/vol/vol) mixed twice with 1 volume of hexane in order to remove bacteriochlorophylls. This suspension was mixed vigorously and incubated at 4°C for 1 h, and protein was pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Western blot analysis was done in accordance with the instructions supplied with the ECL Western blotting analysis kit (Amersham Life Science), with the exception that the blocking time was 2 h. Primary antibodies were raised in rabbit against purified Synechocystis strain PCC6803 ChlI, -D, and -H proteins and used at a final dilution of 1:10,000 (ChlI) or 1:5,000.

HPLC analysis of pigments.

For analysis of porphyrin content, 200 μl of the assay mixture was extracted with 1.0 ml of 80% acetone containing 0.1 M NH3, mixed with 400 μl of hexane, and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 3 min. The acetone phase was analyzed for porphyrins by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a Beckman Ultrasphere octyldecyl silane column (150 by 4.6 mm). The column was eluted with a 10-min linear gradient from 15% solvent A to 100% solvent B at 1 ml/min. Solvent A contained 0.05% (vol/vol) triethylamine in water; solvent B contained 100% acetonitrile. Porphyrins were detected with a Waters in-line fluorescence detector. Excitation at 420 ± 5 nm and emission at 595 ± 5 nm were used to detect Mg-protoporphyrin IX.

RESULTS

Features of the C. vibrioforme bchI and -D ORFs.

In Chlorobium, a number of genes have no Shine-Dalgarno (SD) motifs at the more typical locations just upstream of the start codon (11, 12, 15, 20, 30), and putative intragenic SDs have been suggested to exist within 70 bp of the start codons of the atp2βɛ and the putative hemACD operons (24), a phenomenon which has also been observed in other bacteria (for instance, the archaea [31]). The existence of more than one possible translation start codon and intragenic SD-like sequences found near the N-terminal end of the bchI ORFs complicates the prediction of the in vivo translation start codon (Fig. 1). The overlapping stop and start codons of the bchI and -D ORFs, respectively, indicate that the bchD ORF is the one translated in C. vibrioforme, and alignment of the deduced BchI(2) and -D proteins suggests that these proteins are the ones translated in C. vibrioforme (19), a notion which is supported by the presence of three nested SD motifs found just upstream of the bchI(2) ORF. However, a lysine-, alanine-, and threonine rich-stretch of 44 amino acids is found upstream and in frame with the bchI(2) ORF yielding the bchI ORF (38 and 42 kDa from the deduced amino acid sequence, respectively). Residues 3 to 33 of BchI are able to form a coiled coil structure, and short coiled coils are known to serve as dimerization domains in several families of proteins. Interestingly, Willows et al. (29) have reported that purified R. sphaeroides BchI protein is dimeric. Thus, two constructs corresponding to the bchI and -I(2) ORFs, respectively, were made (Fig. 1).

Reconstitution of activity in vitro and properties of the Mg-chelatase subunits.

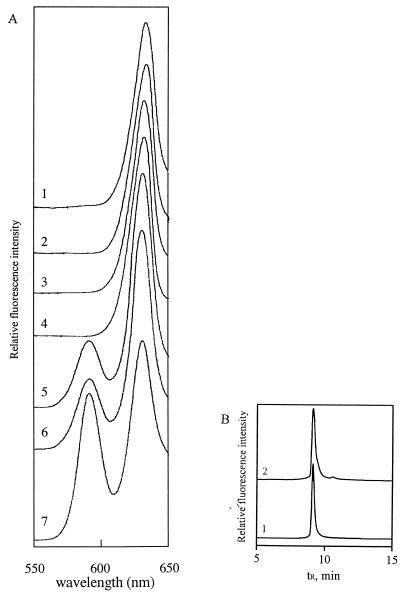

Activity from crude extracts of overexpressed R. sphaeroides BchI, -D, and -H subunits and Synechocystis strain PCC6803 ChlI, -D, and -H subunits was routinely obtained, in accordance with results of Gibson et al. (3) and Jensen et al. (5). However, in vitro reconstitution of activity from crude extracts of the three C. vibrioforme subunits could not be achieved. As a consequence of this, the overexpressed His-tagged BchI, -I(2), and -H proteins were purified on an Ni2+-agarose affinity column, and insoluble BchD proteins, mainly as inclusion bodies, were solubilized in 6 M urea. ATP-dependent Mg-chelatase activity was obtained when His-tag-purified BchI or -I(2), BchH, and urea-denatured BchD proteins were combined (Fig. 3), thereby establishing that the C. vibrioforme Mg-chelatase is similar to the Mg-chelatases of R. sphaeroides and Synechocystis strain PCC6803 with respect to the number of subunits and the ATP requirement. In assays with 30 μg of BchI or -I(2), 30 μg of BchD, and 60 to 70 μg of BchH, ca. 15 pmol of Mg-protoporphyrin IX was formed after 4 h. The continued formation of Mg-protoporphyrin IX during the relatively long incubation time suggests that a large fraction of one or more of the three subunits was initially inactive and was subsequently activated during the incubation period. When the BchH protein was replaced by an approximately equal amount of His-tag-purified Synechocystis strain PCC6803 ChlH protein, activity was increased twofold. Thus, the BchH protein was found to be limiting in assays with the other two C. vibrioforme subunits. Several possibilities might explain this: (i) only a minor fraction of BchH protein is folded into an active form, (ii) the contaminating ca. 80- and 85-kDa E. coli-derived proteins bind to or form aggregates with BchH or have some other inhibitory effect on activity, or (iii) the Mg-protoporphyrin IX formed is not released or is only slowly released from the BchH subunit, thereby limiting the amount of active protein over time. The bchI, -I(2), -D, and -H ORFs have been reamplified by PCR and recloned in pET15b (see Materials and Methods), and identical results with respect to protein expression and Mg-chelatase activity were obtained when expressed proteins from three clones derived from each PCR were assayed. Thus, it seems unlikely that PCR-derived errors could have caused the limited activity of especially the BchH protein.

FIG. 3.

(A) Fluorescence emission spectra from assays demonstrating that the C. vibrioforme subunits BchI/I(2), BchD, and BchH and ATP are required for in vitro reconstitution of Mg-chelatase activity. Trace 1, BchI plus BchD; trace 2, BchI plus BchH; trace 3, BchD plus BchH; traces 4 and 5, BchI plus BchD plus BchH; trace 6, BchI(2) plus BchD plus BchH; trace 7, BchI plus BchD plus ChlH. Assay conditions were as described in Materials and Methods, with the exception that ATP was omitted in the assay shown as trace 4. The characteristic fluorescence maxima of protoporphyrin IX and Mg-protoporphyrin IX are 633 and 595 nm, respectively. (B) HPLC identification of the product formed in Mg-chelatase assays. Trace 1, authentic Mg-protoporphyrin IX; trace 2, product formed from the assay shown as trace 5 in panel A. tR, retention time.

With respect to the BchD subunit, activity was achieved only when highly concentrated insoluble BchD protein was solubilized in 6 M urea and added as the last component to the assay, yielding a final urea concentration of 60 mM. Refolding of urea-denatured BchD protein is likely to occur during the formation of the putative ternary complex between the BchI and -D subunits and Mg2+-ATP, as proposed for the Mg-chelatase of R. sphaeroides (29).

Alignment of the deduced N-terminal amino acid sequences of the “I” and “D” genes from R. capsulatus (1), C. vibrioforme (19), and Synechocystis strain PCC6803 (5) suggests that the C. vibrioforme BchI(2) and -D proteins delineate a homologous core of the aligned proteins (Fig. 4). When assayed under identical conditions together with BchD and -H proteins, the BchI and -I(2) proteins were found to be approximately equally active (Fig. 3). It can thus be concluded that the BchI(2) protein is sufficient for obtaining activity and that the 44-amino-acid N-terminal part of the BchI protein does not have a negative effect on activity. In order to gain further information on the start of the bchI ORF in C. vibrioforme, total protein of C. vibrioforme was subjected to Western blot analysis. Surprisingly, the antibody raised against the Synechocystis strain PCC6803 ChlI subunit reacted specifically with two bands, which appeared to comigrate along with the His-tag-purified BchI and -I(2) proteins (Fig. 5). This suggests that the native BchI protein might be present as two alternative forms. While the 42-kDa form seems to dominate in cells in the exponential phase, the ca. 38-kDa protein is most abundant in cells in the stationary phase. This might indicate either that the ca. 42-kDa protein is the one which is translated and subsequently processed to yield the ca. 38-kDa protein or that the two proteins are translated separately.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the N termini of the I and D deduced amino acid sequences from C. vibrioforme (Cv), Synechocystis strain PCC6803 (SP), and R. capsulatus (Rc). Amino acids conserved in four or more of the aligned sequences are marked by reverse shading, and asterisks designate the phosphate-binding motif (GX4GKSX6A) present in the three I sequences. With respect to the N termini, note that the C. vibrioforme BchI(2) and -D deduced proteins seem to delineate a homologous core of the aligned proteins.

FIG. 5.

C. vibrioforme proteins cross-reacting with antibodies directed against purified Synechocystis strain PCC6803 ChlH (lane 1), -D (lane 2), and -I (lanes 3 to 6) proteins. Lanes 1 to 3, ca. 10 μg of total protein of C. vibrioforme in exponential phase; lane 4, ca. 10 μg of total protein of C. vibrioforme in stationary phase; lanes 5 and 6, ca. 0.05 μg of His-tag-purified BchI (42-kDa) and -I(2) (38-kDa) proteins, respectively (cf. Fig. 2). While the 42-kDa-like protein is dominant in exponential phase cells, the 38-kDa-like protein is most prominent in cells in the stationary phase.

Finally, all combinations of the C. vibrioforme and Synechocystis strain PCC6803 subunits were assayed. Reconstitution of an active heterologous enzyme complex was achieved only when the C. vibrioforme BchI/I(2) and -D proteins and the Synechocystis strain PCC6803 ChlH protein were combined (Fig. 3) or when the Synechocystis strain PCC6803 ChlI and -D proteins and the C. vibrioforme BchH protein were combined, with the latter of the combinations giving rise to only trace amounts of activity (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We have, through reconstitution of Mg-chelatase activity in vitro, demonstrated that the Mg-chelatase of C. vibrioforme is composed of three subunits encoded by the genes bchI, -D, and -H. The Mg-chelatase of C. vibrioforme is similar to the Mg-chelatases of the distantly related bacteria Synechocystis strain PCC6803 (5) and R. sphaeroides (3) with respect to the number and sizes of the subunits as well as the absolute requirement for ATP. Chlorobium, being a strictly anaerobic and obligate phototrophic organism, is believed to resemble some of the earliest life forms present in an anaerobic environment. The finding that the Mg-chelatases of C. vibrioforme, R. sphaeroides, and Synechocystis strain PCC6803 are encoded by three homologous genes, together with genetic and biochemical data which strongly imply that the higher-plant Mg-chelatase is also encoded by three genes (4, 6, 8), makes the three-gene scheme of the Mg-chelatase a ubiquitous feature of probably all photosynthetic organisms. Thus, the ATP-requiring chelation of Mg2+ into protoporphyrin IX seems to be a reaction which imposes considerable constraints on the enzyme.

Two interesting features of the C. vibrioforme Mg-chelatase have been found. First, Western blot analysis indicates the existence of two forms of the BchI protein, which probably correspond to the overexpressed BchI and -I(2) proteins, which were found to be equally active when assayed in vitro. The probable presence of the two BchI forms in C. vibrioforme might relate to the finding that anesthetic gases, such as N2O, ethylene, and acetylene, in C. vibrioforme have been found to inhibit the formation of chlorosomes and bacteriochlorophyll d, which is primarily found in the chlorosomes, without affecting the synthesis of bacteriochlorophyll a, which is associated primarily with the cell membrane and its photosynthetic reaction centers (16). Inhibited cells were found to accumulate primarily Mg-protoporphyrin IX monomethyl ester, the substrate of the enzyme Mg-protoporphyrin IX monomethyl ester cyclase, and it was suggested that bacteriochlorophylls a and d could be differently affected because of compartmentalization of their biosynthetic apparatus (16). Second, in vitro reconstitution of an active heterologous Mg-chelatase enzyme complex between C. vibrioforme and Synechocystis strain PCC6803 subunits has been demonstrated for the first time, and it was found that reconstitution of activity required that the I and D subunits be derived from the same species. The Synechocystis strain PCC6803 ChlH protein has recently been shown to act as a carrier of the substrate protoporphyrin IX, and the interaction of ChlH-protoporphyrin IX with the presumed ternary complex between ChlI and -D and Mg2+-ATP was found to be of a transient nature, at least in vitro (7). The finding that the H subunit from one species can interact with I and D subunits from another species supports the role of the H subunit as a substrate carrier and also suggests involvement of weak or unspecific protein-protein interactions between H and the I-D-Mg2+-ATP complex.

Recloning of the BchH ORF in an alternative expression system and further purification of the subunits have to be carried out before a more comprehensive characterization of the enzyme complex will be possible. Verification of the existence of the two forms of the BchI protein and their localization in C. vibrioforme is in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Inoculum stocks of C. vibrioforme f. sp. thiosulfatophilum NCIB 8327 were kindly provided by H. Scheller, Department of Plant Biology, Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Frederiksberg, Denmark.

This work has been supported by grants from the Danish Agricultural and Veterinary Research Council to Knud W. Henningsen (no. 9601206 and 13-5005) and Poul Erik Jensen (no. 9600928) and from Købmand Sven Hansen og hustru Ina Hansens Fond, Sorø, Denmark. C. Neil Hunter and Lucien C. D. Gibson gratefully acknowledge financial support from the BBSRC, United Kingdom. We are grateful to Ulla Rasmussen and Kirsten Henriksen for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alberti M, Burke D H, Hearst J E. Structure and sequence of the photosynthesis gene cluster. In: Blankenship R E, Madigan M T, Bauer C E, editors. Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 1083–1106. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Strul K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson L C D, Willows R D, Kannangara C G, von Wettstein D, Hunter C N. Magnesium-protoporphyrin chelatase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: reconstitution of activity by combining the products of the bchH, -I and -D genes expressed in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1941–1944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibson L C D, Marrison J L, Leech R M, Jensen P E, Bassham D C, Gibson M, Hunter C N. A putative Mg chelatase subunit from Arabidopsis thaliana cv C24. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:61–71. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen P E, Gibson L C D, Henningsen K W, Hunter C N. Expression of the chlI, chlD and chlH genes from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC6803 in Escherichia coli and demonstration that the three cognate proteins are required for magnesium-protoporphyrin chelatase activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16662–16667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen P E, Willows R D, Petersen B L, Vothknecht U C, Stummann B M, Kannangara G C, von Wettstein D, Henningsen K W. Structural genes for Mg-chelatase subunits in barley: Xantha-f, -g and -h. Mol Gen Genet. 1996b;250:383–394. doi: 10.1007/BF02174026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen, P. E., L. C. D. Gibson, and C. N. Hunter. Unpublished data.

- 8.Kannangara G C, Vothknecht U C, Hansson M, von Wettstein D. Magnesium chelatase: association with ribosomes and mutant complementation studies identify barley subunit Xantha-G as a functional counterpart of Rhodobacter subunit BchD. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;254:85–92. doi: 10.1007/s004380050394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koncz C, Mayerhofer R, Koncz-Kalman Z, Nawrath C, Reiss B, Redei G P, Schell J. Isolation of a gene encoding a novel chloroplast protein by T-DNA tagging in Arabidopsis thaliana. EMBO J. 1990;9:1337–1346. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majumdar D, Avissar Y J, Wyche J H, Beale S I. Structure and expression of the Chlorobium vibrioforme hemA gene. Arch Microbiol. 1991;156:281–289. doi: 10.1007/BF00262999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moberg P A, Avissar Y J. A gene cluster in Chlorobium vibrioforme encoding the first enzymes of chlorophyll biosynthesis. Photosynth Res. 1994;41:253–259. doi: 10.1007/BF02184166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moeller W, Amons R. Phosphate-binding sequences in nucleotide-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 1985;186:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)81326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakayama M, Masuda T, Sato N, Yamagata H, Bowler C, Ohta H, Shioi Y, Takamiya K. Cloning, subcellular localization and expression of ChlI, a subunit of magnesium-chelatase in soybean. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;215:422–428. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okkels J K, Kjær B, Hansson O, Svendsen I, Møller B L, Scheller H V. A membrane bound monoheme cytochrome c-551 of a novel type is immediate electron donor to P840 of the Chlorobium vibrioforme photosynthetic reaction center complex. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21139–21145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ormerod J G, Nesbakken T, Beale S I. Specific inhibition of antenna bacteriochlorophyll synthesis in Chlorobium vibrioforme by anesthetic gases. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1352–1360. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1352-1360.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orsat B, Monfort A, Chatellard P, Stutz E. Mapping and sequencing of an actively transcribed Euglena gracilis chloroplast gene (ccsA) homologous to the Arabidopsis thaliana nuclear gene cs (ch42) FEBS Lett. 1992;303:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80514-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petersen B L, Møller M G, Stummann B M, Henningsen K W. Clustering of genes with function in the biosynthesis of bacteriochlorophyll and heme in the green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium vibrioforme. Hereditas. 1996;125:93–96. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen, B. L., M. G. Møller, B. M. Stummann, and K. W. Henningsen. Structure and organization of a 25 kbp region of the genome of the green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium vibrioforme containing Mg-chelatase encoding genes. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Rhie G-E, Avissar Y J, Beale S I. Structure and expression of the Chlorobium vibrioforme hemB gene and characterisation of its encoded enzyme, porphorbilinogen synthase. J Biol Chem. 1996;14:8176–8182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rieble S, Ormerod J G, Beale S I. Transformation of glutamate to δ-aminolevulinic acid by soluble extracts of Chlorobium vibrioforme. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3782–3787. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3782-3787.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg A H, Lade B N, Chui D-S, Lin S-W, Dunn J J, Studier F W. Vectors for selective expression of cloned DNAs by T7 RNA polymerase. Gene. 1987;56:125–135. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiozawa J A. Genetics of green sulfur, green filamentous and heliobacteria. In: Blankenship R E, Madigan M T, Bauer C E, editors. Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 1159–1173. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sirevåg R, Ormerod J G. Carbon dioxide fixation in green sulfur bacteria. Biochem J. 1970;120:399–408. doi: 10.1042/bj1200399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker C J, Weinstein J D. In vitro assay of the chlorophyll biosynthetic enzyme Mg-chelatase: resolution of the activity into soluble and membrane bound fractions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5789–5793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker C J, Hupp L R, Weinstein J D. Activation and stabilization of Mg-chelatase activity by ATP as revealed by a novel in vitro continuous assay. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1992;30:263–269. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker C J, Weinstein J D. The magnesium-insertion step of chlorophyll biosynthesis is a two step reaction. J Biochem. 1994;299:277–284. doi: 10.1042/bj2990277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willows R D, Gibson L C D, Kanangara G C, Hunter C N, von Wettstein D. Three separate proteins constitute the magnesium chelatase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Eur J Biochem. 1996;235:438–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie D-L, Lill H, Hauska G, Futai M, Nelson N. The atp2 operon of the green bacterium Chlorobium limicola. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1172:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90213-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zillig W, Palm P, Reiter W-D, Gropp F, Pühler G, Klenk H-P. Comparative evaluation of gene expression in archaebacteria. Eur J Biochem. 1988;173:473–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]