Abstract

Self-regulated learning (SRL) is critical to students' academic success and lifelong learning. Although the benefits of SRL have been examined in many studies, few have explored it in a broader educational context. This study presents an eight-month institutional case study that demonstrates how SRL has been developed as a pedagogy through the collective endeavours of teachers, researchers, and experts at a university in Hong Kong. A case study method protocol was followed. Data were obtained from multiple sources, including surveys of teachers (N = 93) and students (N = 215), interviews with teachers (n = 5) and students (n = 19), archived course documents, videos, and project reports. T-tests, coding, and document analysis were applied to analyse the collected data. The results showed that the teachers had good knowledge of SRL strategies but some students struggled to apply them effectively. Our study's findings have various implications for the effective promotion of SRL at the university level, and include the importance of developing a collective approach involving various members of the university, integrating responsive pedagogy, and adapting SRL strategies to students' individual needs. Future research can follow our methodology to replicate the study in different educational contexts.

Keywords: case study, Higher education, Institutional survey, Protocol, Self-regulated learning

1. Introduction

Self-regulated learning (SRL) has been recognised as an important approach to developing students' ability to thrive in today's digital world [1]. SRL is a multifaceted process in which students actively participate in their own learning by managing their cognition, metacognition, motivation, and behaviour [e.g., [[2], [3], [4]]]. According to Butler and Winne [[5], p. 245], ‘the most effective learners are self-regulating’. Others have found that students' engagement in SRL is positively related to their academic achievement in higher education [e.g., [[2], [6], [7]]]. Broadbent and Poon [[8], p. 1] identified various SRL strategies that can lead to academic success, including ‘time management, metacognition, effort regulation, and critical thinking’. In addition, Latif et al. [9] found that self-regulated learners possess more self-control, confidence, and a greater sense of responsibility in learning than others.

1.1. Research gap and Significance of the study

Despite its reported benefits, extending the implementation of SRL to a broad educational context is challenging. SRL has often been studied as a skill required in specific subjects such as music [2], mathematics [10], and language learning [11,12], and little evidence has been provided on how SRL can be developed as a pedagogy for other student populations and subjects. As SRL is associated with students' lifelong learning, in today's digital world [1] it is important to promote SRL in a broader educational context.

This study was conducted in the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic, when most learning was transferred from physical classrooms to online platforms. Students gained autonomy and often enjoyed discretionary time in their studies. To ensure that their virtual performance was maintained and, if possible, increased, both university educators and students were encouraged to apply SRL. However, research activities on campuses became more challenging during the pandemic, as less control over the research conditions was possible due to the physical self-distancing requirements. We therefore considered the case study method, as this allows researchers to investigate a phenomenon with a small sample of participants in a real-life setting and has the potential to make an impact in a broader context [13,14]. Our novel approach of combining a case study with a survey, thus eliciting the comprehensive perspectives of multiple participants including teachers, students, researchers, and experts, reveals how SRL has been promoted at the institutional level over the long term. Our longitudinal investigation conducted over eight months enabled to transform our theoretical insights into meaningful SRL practice for teachers and students over time.

1.2. Research questions

In this study, we examined how SRL has been developed as a pedagogy at the institutional level. Our participants came from various subject backgrounds, and our case study was a renowned education university in Hong Kong. Unlike other studies [1,2,6] exploring the pedagogical approaches to teaching SRL, our aim was to demonstrate how SRL has been developed as a pedagogy through the collective endeavour of teachers, researchers, and experts at the case university. By also presenting students’ experiences of the process, future researchers and educators could apply our insights to SRL in other educational contexts.

The research was guided by the following questions: (1). How is SRL being developed as a pedagogy at the case university? (2). Why are some students able to adopt SRL strategies effectively while others are not?

2. Literature review

2.1. Conceptualisations of SRL

SRL is a self-steering process in which learners use cognitive and metacognitive strategies to regulate their learning and attain their goals [[15], [16], [17]]. The theorisation and development of the concept of SRL was initially influenced by Bandura's [18] social cognitive theory. Bandura [18] proposed that human functioning involves the interaction between an individual, their behaviour, and the environment. Several SRL frameworks were subsequently developed based on this work, aimed at understanding and guiding students' learning. For example, Schunk [19] considered SRL to consist of a combination of goal-setting, self-efficacy, and self-regulation. Zimmerman [3] proposed that the SRL process consists of the three phases of forethought, performance, and self-reflection. Forethought entails task analysis and a self-motivation belief, performance entails self-control and self-observation, and self-reflection entails self-judgement and self-reaction [17]. Pintrich [20] introduced the notions of metacognition and social context to the concept of SRL and included regulating behaviours in the forethought phase and planning in both cognitive strategies and recourse management, which differentiates his framework from those of others. Despite the differences in subsequent frameworks, most researchers agree that SRL takes place when learners (a) actively participate in the learning process; (b) set goals for their learning; (c) control, monitor, and regulate their cognition and behaviour; and (d) mediate the relationships between their perceptions, the learning environment, and their learning behaviour [15,17,20].

We adopted Zimmerman's [17] SRL framework to address our research questions. Zimmerman explicitly described the SRL process in phases, thereby offering specific and actionable strategies that educators can implement [21]. In addition, Zimmerman's framework is the most comprehensive because it covers most of the elements of other SRL frameworks. For example, the subprocesses (self-observation, self-judgement, and self-reaction) in Schunk's [19] SRL framework fall within the performance and self-reflection phases of Zimmerman's framework. Pintrich's [22] four phases can also be considered part of Zimmerman's framework. His monitoring and control phases align with Zimmerman's notion of performance, and his forethought, planning, and activation phase and reaction and reflection phase echo Zimmerman's forethought phase and self-reflection phase. Zimmerman's framework has been widely applied in recent research. For example, Spruce and Bol [23] applied the framework to investigate elementary and middle school teachers' beliefs, knowledge, and practices in relation to SRL. They identified gaps in teachers' knowledge of goal-setting and evaluation, but found that teachers knew how to encourage students to practise metacognition. Kizilcec et al. [24] used Zimmerman's SRL framework to investigate undergraduate online learners' SRL in massive open online courses (MOOCs). They found that goal-setting and planning correlated with learners' high achievement and that help seeking was related to lower levels of goal achievement. They also found that students' SRL skill levels helped to determine their chosen cognitive strategies. Those with higher skill levels were more likely to construct their knowledge from previously learnt materials than those with lower levels [24].

2.2. Measurements of SRL

Various questionnaires have been developed in previous SRL studies, such as the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) of Pintrich et al. [25], Weinstein and Palmer's [26] Learning and Study Strategies Inventory (LASSI), and the Online Self-Regulated Learning Questionnaire (OSLQ) of Barnard et al. [27]. We used the OSLQ in this study because it fits the context of blended learning, which involves both online and face-to-face teaching and is suitable for our study. The questionnaire includes six dimensions, which demonstrate the three phases of Zimmerman's [17] framework in the context of online learning. These dimensions are environment structuring, goal-setting, time management, help seeking, task strategies, and self-evaluation [27]. The questionnaire has been applied as a survey instrument in numerous studies [e.g., [[28], [29], [30], [31]]]. Kintu et al. [30] used a questionnaire to examine how the design features of the online learning environment and students' characteristics and backgrounds can affect learning outcomes. They found that SRL skills and design features such as the quality of technology in the learning environment were positively related to learning outcomes. Biwer et al. [29] adapted this questionnaire to investigate students' SRL during remote learning and found that they did not have the skills to effectively regulate their time and attention and were less motivated to learn online than in a physical learning environment.

In this study, we drew on both Zimmerman's [17] three phases and the six dimensions of SRL proposed by Barnard et al. [27]. Zimmerman suggested that the forethought phase represents the process that precedes any learning effort, which aligns with the dimensions of environment structuring and goal-setting in the OSLQ proposed by Barnard et al. The performance phase includes behaviours that take place during the learning process and align with the time management, help seeking, task strategy, and self-evaluation aspects of the OSLQ. The self-reflection phase occurs after the learning process and is aligned with the self-evaluation aspect in the OSLQ.

2.3. SRL in higher education

Given the diversity of both students and modes of instruction in higher education, the differences in students' individual approaches to learning should be considered [e.g., [32]]. Learning has become more accessible to a larger student population as information communication technologies have developed, further increasing student diversity [33]. SRL is recognised as an effective way to capture students' individual differences in learning and enables teachers to adjust their teaching to students’ needs [e.g., [34]]. Numerous studies have examined how SRL is promoted in higher education with the aim of helping students develop the lifelong skills necessary for their future success [e.g., [[30], [35], [36]]]. For example, Broadbent and Poon [8] conducted a systematic review of the relationship between SRL and academic achievement in the context of online higher education. They found that strategies such as critical thinking, metacognition, and time management were strongly correlated with student achievement.

Mega et al. [36] also found that undergraduate students' emotions played a role in their SRL, influencing their learning performance. They found that the relationship between students' emotions and performance was fully mediated by SRL, meaning that positive emotions only facilitated learning through the mediating effect of SRL. Mega et al. [36] suggested that in addition to promoting SRL, greater efforts are needed to understand undergraduate students' emotions, as this can improve their academic performance. Nugent et al. [37] recommended various explicit approaches to help students self-regulate their learning. They suggested that teachers should be involved in students’ planning, monitoring, and evaluating so that students can apply more metacognitive practices in their learning. Consistent with the propositions of Mega et al. [36], Nugent et al. [37] also suggested that students need cues to engage in SRL and that their emotional learning should be understood and addressed so that they can regulate their emotions and achieve their learning goals.

Despite substantial research demonstrating the importance of SRL, effectively encouraging it in higher education can be challenging. Students are often assumed to be prepared for SRL when they enter university, but they may not have sufficiently developed the required skills [37,38]. Previous studies have suggested that SRL skills can be enhanced by life experience and maturity, but learning and assessment can also help to develop them in an educational context [16,37]. In the present study, we examined how SRL can be broadly developed as an effective pedagogy at the university level by conducting an institutional case study.

2.4. A case study approach

The benefits of SRL for students' academic success have been empirically confirmed, and many studies have provided practical suggestions for teachers to enhance students' SRL. Research approaches include survey instruments [e.g., [34]], interviews [e.g., [2]], case studies [e.g., [39]], or combinations of these approaches [e.g., [40]]. These studies have suggested technology-based tools that support students' SRL [e.g., [[41], [42]]], SRL teaching strategies [e.g., [40]], professional development programmes that increase teachers' knowledge of and belief in SRL [e.g., [39]], and the benefits of identifying students’ cognitive, motivational, or affective conditions, which can lead to adjustments that enhance the teaching of SRL [e.g., [[34], [43]]].

We considered the case study to be an effective approach compatible with the research background of this study. This approach makes it possible to describe and explore the multiple details of a complex phenomenon in a real-life context [13,14,44]. It is especially relevant when addressing ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions [45]. The case study approach has the benefits of qualitative research, as it helps researchers understand the underlying motivations and perceptions [44,46], and also enables the validation of the given phenomenon through quantitative data [44]. It is also appropriate when researchers have little control over the investigated phenomenon [44,47] and for investigations of small samples. The underlying motivations and opinions of a small number of participants can be revealed and then applied to a broader context [13,14].

The case study approach has been applied in previous studies of SRL in higher education (e.g., Refs. [[48], [49], [50]]. Case study methodologists have not reached a consensus on how a case study should be designed and implemented, and various approaches have been taken to SRL case studies. For example, Moseki and Schulze [50] assessed whether an intervention on SRL skills could enhance students' SRL and engineering performance by delivering a 12-session workshop (24 h in total) in a technological university. They collected data through survey instruments and written feedback from 20 students. Kim et al. [48] conducted a case study at a women's university in South Korea. They analysed 284 students' log data on the online learning platform Moodle and collected surveys to explore their SRL learning patterns over two consecutive semesters. However, the large sample size and intensive interventions applied in previous SRL studies may not be feasible in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first SRL study to apply a case study protocol. The case study protocol developed by Yin [51] is suitable for real-world investigations with a small sample. Yin [51] noted that using a protocol can also strengthen the reliability of a case study and that the research procedures are made explicit, so that other researchers can repeat them and thus replicate the results.

3. Method

In this study, we applied a case study method and collected data from multiple sources. Both quantitative and qualitative data were analysed. We applied Yin's case study protocol [51], which includes (a) an overview of the case study, (b) data collection procedures, (c) protocol questions, and (d) a case study report.

3.1. Overview of the case study

The case university focuses on educational research and supporting the strategic development of teaching. The university's research centres played an important role in transferring teaching and learning onto an online platform when physical self-distancing was required during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, some courses were challenging to teach online so the university had to find new solutions to maintain teaching and learning. One of the university's research centres launched a research project through which SRL was advocated as the most effective solution for online teaching and learning. The centre promoted SRL as a pedagogy for university teachers, and by working closely with the centre, we were able to collect data.

3.2. Data collection procedures

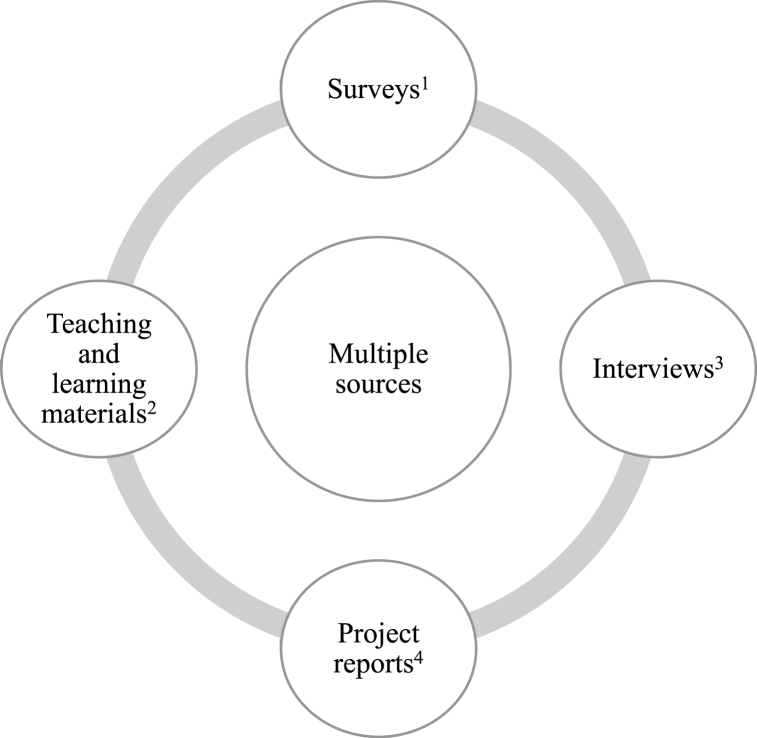

The aim of conducting a case study is to reveal a particular phenomenon in a real-life context via in-depth investigation [51]. Collecting relevant data from multiple sources can provide greater depth and context and also allows for data triangulation, which can strengthen the construct validity of the case study [51]. Using multiple sources to measure the same phenomenon also increases the accuracy of the investigation [52]. Therefore, we obtained our data through surveys, interviews, teaching and learning materials, and project reports. Ethical approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the university (Ref. No. 2020-2021-0401) for the data collected for this study. Fig. 1 summarises the sources used.

Fig. 1.

Multiple sources of this case study.

Notes.

-

1.Surveys. Questionnaire adapted from the SRL instrument of Barnard et al. (2009)

-

(a)teachers (n = 93).

-

(b)students (n = 215).

-

(a)

-

2.Teaching and learning materials.

-

(a)archived course documents such as syllabi, teaching slides, assignment requirements, and sample student assignments.

-

(b)recorded videos of two seminars.

-

(c)tutorial videos recorded by the research centre.

-

(a)

-

3.Interviews.

-

(a)teacher participants (n = 5).

-

(b)student participants (n = 19).

-

(a)

-

4.Project reports.

-

(a)progress report by the research centre.

-

(b)evaluation report by experts.

-

(a)

3.2.1. Surveys

To obtain a basic understanding of the approach to SRL at the university, separate surveys were sent out to all of the teachers and all of the students at the university by email in January 2022. Both surveys were based on the SRL questionnaire developed by Barnard et al. [27] and used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The teacher questionnaire investigated their support of students' SRL, and the student questionnaire captured their actual SRL behaviour and their perceptions of their teachers' support. A sample item for teachers is ‘I suggest that my students study in a favourable physical learning environment, which can optimise their learning,’ and a sample item for students is ‘I know where and when I can study most efficiently’. A total of 93 teachers (female n = 47; male n = 46) and 215 students (female n = 177; male n = 38) completed the questionnaires. T-tests were performed to examine the differences between the teachers' and students' responses.

3.2.2. Interviews

Participants. All of the teacher and student participants were informed of the aims of this study at the university via email. Five teachers of different courses and 19 of their students joined the case study voluntarily. Pseudonyms were allocated to the teacher participants (Sarah, Linda, Chris, Wendy, and Ryan) for ethical purposes. The student participants were anonymised and labelled using a combination of the initial letter of their teachers' pseudonym and a number. For example, Student S1 was Sarah's student. Participant information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant information.

| Teacher | Gender | Student | Gender | Department | Course Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarah | Female | Student S1 | Female | Cultural and creative arts | Design a workshop and implement it |

| Student S2 | Female | ||||

| Student S3 | Female | ||||

| Student S4 | Female | ||||

| Student S5 | Female | ||||

| Linda | Female | Student L1 | Female | English language education | Write an academic research proposal |

| Student L2 | Female | ||||

| Chris | Male | Student C1 | Female | English language education | Conduct small-scale research |

| Student C2 | Female | ||||

| Student C3 | Female | ||||

| Wendy | Female | Student W1 | Male | English language education | Design a workshop and implement it |

| Student W2 | Male | ||||

| Student W3 | Male | ||||

| Student W4 | Male | ||||

| Student W5 | Male | ||||

| Ryan | Male | Student R1 | Female | Health and physical education | Create a lesson plan and implement it |

| Student R2 | Female | ||||

| Student R3 | Male | ||||

| Student R4 | Female |

In-depth interviews were conducted with the teacher and student participants over three stages in January, April, and August 2022, respectively. In stages 2 and 3, we provided the teacher participants with feedback on how their students perceived and practised SRL in their learning, and the teachers could then adjust their teaching strategies accordingly. As mentioned, the aim of conducting a case study is to investigate a phenomenon in its real-life context, so data collection should take place in the participants' everyday situations rather than being restricted to a specific environment or tool such as a laboratory, library, or structured survey [51]. Therefore, our interviews were open-ended and the interviewees were not restricted to the interviewers’ line of questioning.

The interview questions were developed based on Zimmerman's [17] three SRL phases and the six dimensions identified by Barnard et al. [27]. An example of an interview question for the teacher participants is ‘How do you help students to plan their study, for example in terms of goal-setting?’ and for the student participants is ‘What are your goals for this course and how do you plan to achieve them?’ All of the interviews were recorded with the consent obtained from the participants and each lasted around 30 min. They were subsequently transcribed and coded. Both deductive and inductive approaches were used for coding. The data were first categorised according to the six dimensions of environment structuring, goal-setting, time management, help seeking, task strategies, and self-evaluation proposed by Barnard et al. [27]. The participants' perceptions and practices regarding each dimension were then identified. A sentence segment from a teacher participant such as ‘ … and for them to aim higher, I'll tell them what I expect from them’ would first be categorised as goal-setting and then coded as ‘setting expectations’.

3.2.3. Teaching and learning materials

Teaching and learning materials were collected to review how SRL was implemented at the university, first in the form of archived course documents. These included the course syllabus, teaching slides, assignment requirements, and the sample student assignments that were uploaded to the university's learning management system (Moodle) by teachers and students. The students could access the materials for their preparation and reflection. Second, two seminars were organised by the research centre and delivered to teachers and students in February and March 2022, respectively. Both seminars were given by an expert in the field of SRL and aimed at developing teachers' and students' SRL strategies. The seminars were recorded with the consent of all of the attendees and subsequently reviewed. Third, tutorial videos on how to develop SRL strategies were created by the research centre and uploaded to the university website for teachers and students. We also examined these videos for this study.

3.2.4. Project reports

Two project reports were reviewed in this study. One (hereafter ‘the progress report’) was provided by the research centre and presented both quantitative and qualitative evidence regarding the progress and outcomes of the project. The other (hereafter ‘the evaluation report’) was prepared by a quality committee comprising various experts nominated by the faculty deans. This highlighted some of the practices that were effective in the promotion of SRL at the university. The quality committee also made suggestions on how SRL at the university could be developed on a larger scale in the future. We extensively reviewed the evaluation report to understand how the practice of SRL is evaluated from an expert perspective.

3.3. Protocol questions

‘Protocol questions’ is termed by Yin [51]. Unlike survey instruments or interview questions, protocol questions are posed to the researchers instead of the participants of the study. Yin [51] suggested that protocol questions can be useful to keep data collection and data analysis on track. They are also of value when conducting a case study, especially when data are obtained from multiple sources, and remind the researchers of what data should be collected and why. In addition, protocol questions can be used as prompts when designing survey instruments and posing interview questions to participants. However, they may not necessarily be in the form of questions, but can be statements that represent researchers' lines of inquiry when conducting the case study. A list of potential sources of evidence should be provided along with these statements [51]. These guided the authors through the process of answering the research questions. Fig. 2 presents the protocols and potential sources of evidence.

Fig. 2.

Protocols.

3.4. Case study report

We developed a case study report that was structured according to Zimmerman's [17] SRL framework of forethought, performance, and self-reflection. Multiple sources of evidence were reported and triangulated for each dimension of the model.

4. Results

The survey results were analysed with SPSS 28 analytical software. The teachers' perceptions of the six dimensions and the students’ ratings of their actual SRL practice were compared using paired t-tests. An inductive approach was taken when analysing the qualitative data from the interviews, teaching and learning materials, and project reports via the NVivo 12 program. A careful reading of the data sources was carried out to identify meaningful segments related to the six dimensions. These segments were then organised and triangulated with other data sources to generate interpretations relevant to the research questions. Data processing was conducted by the authors and informed by the opinions of the external experts from the SRL project. Any disagreements were addressed through ongoing discussions between the authors and experts.

4.1. Survey results

Table 2 summarises the results of the teacher and student surveys. The paired t-test results showed significant gaps between the teachers' (n = 93) and students' (n = 215) perceptions of goal-setting (t = 4.16, p < .001), time management (t = 6.93, p < .001), help seeking (t = 4.14, p < .001), and task strategies (t = 4.06, p < .001). The teachers' perceptions of their support for these dimensions were significantly higher than the students' ratings of their own SRL practices. In addition, the teachers' perceptions of their support for environment structuring were lower than their students' ratings, while their perceptions were higher for self-evaluation. However, the differences for both environment structuring (t = −0.54, p > .05) and self-evaluation (t = 1.13, p > .05) were not significant. The survey results provide a rough baseline of teachers' and students’ perceptions and behaviours related to SRL at the university. Other perspectives of teachers and students were revealed through other data sources.

Table 2.

T-test results of the surveys.

| Six Dimensions of Self-Regulated Learning | Students (n = 215) |

Teachers (n = 93) |

Mean Difference | Paired T-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Environment Structuring | 4.09 (0.70) | 4.04 (0.73) | −0.48 | −0.54 |

| Goal-Setting | 3.91 (0.66) | 4.24 (0.56) | 0.32 | 4.16*** |

| Time Management | 3.97 (0.69) | 4.46 (0.51) | 0.49 | 6.93*** |

| Help Seeking | 4.01 (0.70) | 4.34 (0.54) | 0.33 | 4.14*** |

| Task Strategies | 3.84 (0.65) | 4.17 (0.63) | 0.32 | 4.06*** |

| Self-Evaluation | 3.81 (0.70) | 3.91 (0.71) | 0.10 | 1.13 |

| Total | 3.93 (0.58) | 4.20 (0.45) | 0.27 | 4.03*** |

Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

4.2. Forethought: environment structuring

The social distancing policy implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic meant that learning was largely dependent on an e-platform environment at the time of the study. During the three interviews, most of the teachers and students held positive attitudes towards the online environment. Linda mentioned that the e-platform helped students to engage more in class. She used various e-tools such as Kahoot and Padlet to design quizzes. The students also said that they enjoyed using the e-tools because they found them interesting and interactive. They also said that they used multiple devices while attending the online courses. Student S2 reported that he could use his smartphone to search for course-related resources while attending the course on his laptop, which he believed made his study more efficient. In addition, Student C2 stated that as the online course was recorded, he could watch the lecture again if he needed to, which was helpful for his self-learning.

However, some of the students raised concerns. For example, inadequate Internet connections and devices prompted some of the students to study on campus rather than at home. As Student S5 explained, ‘The Wi-Fi at home is not working well, as it is being used by my family at the same time. A few times, I missed the key points of the lecture because of my poor Internet’. He also expressed that his home environment was not suitable for online study: ‘My room is rather small, I must attend the course in the living room. Sometimes they [his family] make quite a lot of noise in the living room, and I cannot really focus on my study’. In addition, the online environment restricted some of the students' practical activities. Student W3 reported that ‘STEM [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics] has been developing really fast this year in Hong Kong. I want to be an ICT [information, computer, and technology] teacher after I graduate. I wish I could visit some schools and see what facilities they use to implement STEM, so I could learn something from the schools and practise for my future job. However, it is difficult to visit schools currently, as most of the courses [of those schools] are conducted online’.

For the teachers, the main concern about the online teaching environment, as Linda explained in the Stage 1 interview, was that almost all of the students turned off their cameras. Linda found it difficult to engage students when their cameras were off. Chris reported the same concern about students refusing to turn on their camera. The situation had not improved by the time of the Stage 2 interview. Linda explained, ‘I tried so many times to encourage them to turn on their camera. Only a few would do so after I made the request, but they turned it off again shortly after. However, I noticed that even though their camera was not on, they were concentrating on the course’. Student C1 said, ‘I just don't want to turn on my camera because no one is turning it on. I will only turn it on when I need to deliver a presentation’.

4.3. Forethought: goal-setting

Table 2 shows a significant difference between the teachers' support for goal-setting and the students' actual goal-setting practices before the Stage 1 interview, which may indicate that the students did not effectively transform their teachers' instructions into practice. However, some improvement was noted after the research centre provided seminars and tutorial materials. Linda applied the strategies she learnt during the seminar. In her teaching slides, she broke down the reading plan into small and specific tasks and set due dates for each task. She also explained why chunking the tasks was necessary. In terms of the students' perceptions, Student L1 said in the Stage 3 interview, ‘I used to lose my motivation quickly after I set a final goal for the course. Now my teacher taught me how to set small goals. With those small goals, I know what I need to do by steps. For example, to complete my essay, I set some time for reading notes and literature, and then I move on to writing. I feel so much more motivated by achieving every small goal now’.

4.4. Performance: help seeking

Table 2 shows that in the surveys, help seeking was rated significantly higher by the teachers than by the students. However, the interviews indicated less of a gap. The teachers offered consultation sessions to help their students with SRL and uploaded learning resources to the university's learning management system (Moodle). All of the teachers offered more than one consultation to keep the students on track. Sarah believed that the consultations were valuable to the students because they helped them with their studies: ‘Most of the students would stay online after the course. They would show me their work and ask for feedback and suggestions’. Similarly, Ryan said, ‘I offer consultations to my students every lesson, and they are encouraged to approach me after the course if they have any questions regarding the course content. Usually, around half of the class would stay behind and ask for feedback on their work’. In addition to consultations, the teachers offered learning materials to help their students with SRL. By examining the archived documents, we found that Sarah prepared many resources to upload to Moodle. For example, for one lesson she provided her students with the course outlines, student grouping list, assignment requirements, reference papers, and links to tutorial videos.

The three stages of the interviews showed that most of the students (e.g., W2, W5, R1, S3, and S4) attempted to solve their problems on their own by searching for information online or in the library before they reached out to others for help. Student S4 said, ‘I need to make a project plan on my own. I need to find a potential organisation to cooperate with. However, I do not know how to reach and invite these people [from the potential organisation]. All I need to do is to look up information about the organisation online. Combining that with what I learnt during the lesson, I think I can learn a lot more from the Internet by myself’. In addition, some of the students tended to seek help from their peers if they encountered difficulties, as Student S3 explained: ‘When I encounter problems, the first thing I do is text my groupmates, asking them for suggestions. I would ask them where I can find some useful information for my project. Also, I would show them my work and ask them for feedback. For example, I showed them my poster, and then I asked them if there was any information that should be added to the poster and how I should make my poster stand out to the audience’.

The teachers and students all said that the process for obtaining help was smooth and effective. Thus, no perception gap between the teachers and students was identified during the interviews.

4.5. Performance: task strategies

In the surveys, the teachers rated the task strategies significantly higher than the students (Table 2). The interviews indicated that the teachers learnt SRL strategies through seminars and tutorial videos. They suggested many strategies to their students, but some of the students believed that their SRL depended more on their interest in the tasks than on the resources available to them. If they were not interested in the tasks, they were unlikely to spend time exploring the suggested strategies. In the Stage 3 interview, Student S5 explained, ‘It really depends on my interest in the task. I have my own way to complete the tasks. Even if the teacher offers me some strategies, I would still complete the tasks in my way if the tasks do not seem interesting to me. I do not want to spend time exploring the tasks’. Student L1 further explained that the strategies that the teacher provided did not suit her: ‘There was a time when I totally lost my motivation in the course. I approached my teacher for help. My teacher sent me a timetable template, suggesting that I plan my own schedule with that template. That template looked good, but it was just not for me. I already have my own way to plan my schedule. I think that [the template] might be helpful for others, but not for me’.

Despite the minor gap between the teachers and students identified during the interviews, evidence of good practice in terms of SRL task strategies emerged. Most of the students reported that they learnt strategies for making full use of the learning resources and monitoring their learning progress. The use of mind maps was encouraged at each of the three interview stages in Linda's course and the students were required to summarise the course content in the form of a mind map. All of the mind maps in the archived documents uploaded to Moodle showed that the students were clear about what they had learnt during the course. They believed that the mind maps enhanced their understanding of the course content, as Student L1 explained: ‘It really helps a lot. First, it helps me go through the [course] content after the lesson, which makes my understanding of the lesson deeper. Second, by reading my classmates’ mind maps, I can spot what I have missed in the course, which helps me improve my learning’.

4.6. Performance: time management

The survey results showed that the teachers' ratings of time management were significantly higher than those of the students (see Table 2). However, the perception gap was not overt across the three interview stages, although Student C3 reported that he had difficulty meeting deadlines: ‘I think it is mostly due to my poor self-discipline. I did make plans for my study. However, I did not stick to my plan, which usually led to the situation where I was rushing my assignments or even could not finish my assignments by the deadlines’.

Most of the teachers provided their students with their teaching schedules, which specified the required tasks and the deadlines for each task. The teachers also conducted regular compulsory consultations. Chris explained his approach to arranging the consultations: ‘The deadlines for each task are very specific. We have two consultations for this course. By the first consultation, students are required to submit their draft [proposal] by the first deadline. After the first consultation, they need to revise their draft by the second deadline before the second consultation. Then, after the consultation, they need to present their proposal by the third deadline. Finally, after the presentation, they need to submit the final proposal by the fourth deadline. As you can see, the tasks are specific, as are the deadlines. This is to keep them [the students] on track’. Student C1 said, ‘With those deadlines, I can prioritise some tasks over others. I always try my best to complete the tasks with an approaching deadline, simply because I don't want to rush at the end of the day when the deadline comes'.

4.7. Self-reflection

All of the teachers provided their students with guidance on self-reflection. This included strategies for self-reflection and rubrics for self-examination. For example, Wendy required her students to make a proposal for their course assignment. Regular meetings were set up between Wendy and her students so she could ensure that they were progressing towards the proposed goals. According to Wendy, ‘self-reflection occurs every time when they [students] re-visit their proposals. It is a good practice for them to reflect on what they have done to meet their goals, what more could be done, and what could be improved’. Students' self-reflection occurred when they reviewed the course materials (e.g., R3, R4, W4, L1, and L2) and when they compared themselves with their classmates (S2, R2, and W1). Students L1 and L2 reported that they got into the routine of reviewing the course materials after every lesson. Linda explained, ‘I think reflection is really important. Reflection should be involved in the course design. In practice, we should constantly require students to make reflections. With the habit of self-reflecting, I believe they will find it beneficial not only for this course but for other courses as well’.

Sarah required her students to upload their assignments to Google Drive and encouraged them to make comparisons and learn from each other: ‘ … in that way, you [students] get to know that your classmates might do a better job than you do. So, go and check what you can learn from them’. Student S2 said, ‘One of my seniors, who used to be a student of this course, showed me her assignment for the course. After reading her proposal, I realised that so many details were missing in mine. I never knew that the proposal could be designed in such a specific way. She used to work for my teacher on some projects, and she knows my teacher's expectations for the course, so after comparing my proposal with hers, I realised that there was still room for mine to improve’. Student S1 said, ‘Other than comparing with my classmates, I also compared with the “old me”. I mean, I would compare my current assignments with my former ones, reflecting on whether I had made some progress or not’.

4.8. Summary

In addition to the interviews and teaching and learning materials, the experts' evaluation report identified various good SRL practices at the university. The experts confirmed that the teaching resources offered by the research centre were well-designed and supported by theory. They also noted that the seminars organised by the research centre delivered the target content for SRL and offered an effective experience-sharing platform. The tutorial videos offered were deemed to be rich and highly actionable in terms of their content. However, the experts also raised some concerns, pointing out that the pedagogical design and activities were not sufficient for the successful promotion of SRL. Although extensive resources were provided by the research centre, the rationale behind them was vague, and how they could facilitate SRL was unclear. Overall, the experts rated the project's progress as satisfactory and suggested that their concerns should be addressed in a future stage. By integrating all of the data sources and answering the protocol questions, we summarise the elements of the university's development of SRL as a pedagogy (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Developing SRL as a pedagogy, as suggested by the case university.

| Entity | Strategies |

|---|---|

| Researchers and experts |

|

| Teachers |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

5. Discussion

Developing SRL as a pedagogy requires not only the efforts of university teachers but also administrative assistance from the university. The student participants in this study showed their progressively better experience of SRL over the eight months. The teachers’ strategies along with the tutorial seminars and videos offered by the research centre may have contributed to this improvement. This study also illustrates how the practice of SRL was evaluated at the university. Some of the merits and concerns regarding this practice were highlighted by the experts. In general, the practice of SRL that we found through this case study offers actionable implications for the development of SRL as a pedagogy in higher education (Table 3), which answers our first research question: How is SRL being developed as a pedagogy at the case university?

The surveys revealed that before this study, there were some gaps between the teachers' and students' perceptions of goal-setting, help seeking, time management, and task strategies. The experiences of the participants in the surveys can be seen as a reflection of their experience within the university as a whole and can be taken as a reference. The subsequent interviews showed that the teachers appeared to have a good knowledge of how to teach the six dimensions of SRL and that they applied strategies that followed the theories they had learnt. However, the students did not seem able to transform these strategies into their own practice. Therefore, we argue that instead of dwelling on the procedural details of teachers' strategies for implementing every dimension of SRL, it is more important to explore and reveal the factors that promote and hinder students’ SRL. Our analysis of the last factor (i.e., individualising SRL strategies) answers our second research question: Why are some students able to adopt SRL strategies effectively while others are not?

5.1. Creating a collective endeavour

Teachers, researchers, and experts cooperated at the university to create a rational and resource-rich environment for improving students' SRL experience, which is one of the factors favourable to promoting SRL. Many SRL studies have suggested practical solutions that teachers can apply to enhance students' SRL [e.g., [[40], [41], [42], [43]]]. However, most of the proposed solutions rely on teachers' ability to carry them out, although research has shown that teachers may not have sufficient knowledge to promote SRL. For example, although the teachers in the study by Dignath-van Ewijk and Van der Werf [53] acknowledged the importance of SRL, most of them did not know how to equip their students with SRL strategies. They typically offered a learning environment in which students had the autonomy to learn, but they explicitly taught few strategies for regulating this autonomy due to their lack of SRL knowledge [53]. Professional development programmes can help to improve teachers' knowledge of and belief in promoting SRL [39]. However, a lack of professional development is not the sole reason for weak SRL instruction regarding students’ lifelong learning. Spruce and Bol [23] found that time and curriculum constraints were more challenging for teachers than the need for professional development. The teachers commented that their teaching schedule was tight and that there was not much room left in the curriculum for them to teach learning skills. These findings align with those of Cleary et al. [39], who suggested that external barriers and constraints such as insufficient time and low student engagement hindered the integration of SRL into teaching. Therefore, we argue that teachers alone cannot overcome the challenges of promoting SRL among students, especially in the broad context of a university and all of its students.

Our study contributes to the literature by providing a comprehensive case analysis of a situation in which multiple entities are involved in promoting SRL. Researchers, with the help of experts, educate teachers and offer them resources such as seminars and tutorial videos to help them teach SRL. The researchers bridge the relationship between teachers and students in the teaching of SRL. They track students' perceptions and expectations of their SRL and give feedback so that teachers can adjust their teaching accordingly. The experts then evaluate the teachers' and researchers’ promotion of SRL and give feedback and advice to improve the experience. Finally, a platform is created for researchers, experts, and teachers to promote SRL as an effective pedagogy. This case study is the first attempt to investigate SRL from the perspective of a collective university effort. Thus, it offers a valuable reference for educators who wish to develop SRL as a pedagogy in their universities.

5.2. Integrating a responsive pedagogy

We identified regular feedback practices between the teacher and student participants, which is another favourable factor for the promotion of SRL. Feedback was provided through consultations that the teachers offered to their students. This practice can be considered part of a responsive pedagogy, which is ‘the recursive dialogue between the learner's internal feedback and external feedback provided by significant others, e.g., teachers, peers, parents' [54, p. 9]. This responsive form of pedagogy occurs in all three phases of SRL [54]. Internal feedback is continually generated by students as they regulate their learning [55] and as they engage in a learning activity. They evaluate and monitor the gap between their goals and their actual performance, either intentionally or unconsciously. This is an inherent process in SRL [5, p. 246]. External feedback from a teacher or a peer must be processed and transformed into internal feedback for it to have an impact on students' actual performance [56]. Effective external feedback should facilitate students' internal monitoring and help them to close the gap between their goals and current performance. The intention should be to develop students' confidence and self-efficacy in their ability to successfully complete tasks [54,57]. Researchers have found that ineffective or absent external feedback leads to poor internal feedback, which can further impede student learning [e.g., 57, 58]. For example, students with poor internal feedback might adopt poor strategies, lower their goals, and over- or under-estimate their competence, all of which may be detrimental to their SRL [58].

Consultations were conducted on a regular basis by all of the teacher participants in this study. These consultations had two main positive effects. First, the teacher participants believed that the consultations could help them keep their students' learning on track by enabling them to monitor their students' learning progress and adjust their teaching accordingly. Second, the student participants regarded the consultations as important sources of useful feedback, which helped to improve their learning and facilitate their SRL. We consider regular consultations as a form of responsive pedagogy because they led to recursive dialogues between the student participants' internal and external feedback. When the student participants received feedback from their teachers, they reflected on what they had learnt and what they could have done better, and then revised their work (e.g., Students W1 and R2). Through this process, the students transformed external feedback into internal feedback. They evaluated their teachers' external feedback on their current work, during which internal feedback was produced, which increased their self-efficacy and confidence. Importantly, the gap between the students’ goals and their current performance narrowed [55]. This finding indicates that integrating responsive pedagogy can help to develop SRL as a pedagogy. However, for external feedback to be effective, it must be straightforward so that students can understand it and increase their confidence in meeting challenges; they can then successfully turn this external feedback into internal feedback that has a positive impact on their SRL.

5.3. Individualising SRL strategies

Teachers' strategies may not be suitable for all students, and thus may hinder some students' SRL. According to Azevedo [59], cognitive, affective, metacognitive, and motivational (CAMM) processes are central to students' SRL. First, students construct knowledge from their cognitive system [3,22]; second, they apply metacognitive strategies to regulate the knowledge they construct; third, they apply their motivational beliefs such as self-efficacy and affective beliefs (i.e., positive or negative opinions about the learning tasks) to their learning; and fourth, they regulate these motivational and affective beliefs. Finally, the CAMM processes determine students' choice of behaviours, such as seeking help and task strategies [22]. As the CAMM processes will differ by student, the SRL outcomes of fixed strategies are likely to vary. Teachers' strategies can contribute to students' SRL if they fit with the students' CAMM processes. Conversely, students’ SRL may be discouraged if the stratigies are not individualised, answering the second research question of this study: Why are some students able to adopt SRL strategies effectively while others are not?

In this study, some of the student participants manifested affective and motivational processes. Those such as Student L1 reported that their teachers' strategies were not suitable for them. They believed that their needs were unique and that the teachers' offerings were not compatible with their goals. They also felt that motivation played a more important role in their SRL than strategies for learning. Teachers should therefore ensure they are aware of their students' goals and where their motivation comes from. Students' goals can be categorised as mastery- or performance-oriented [60]. Those with mastery-oriented goals are more intrinsically motivated and aim to enhance their personal competencies, while students with performance-oriented goals are more extrinsically motivated and will aim to outperform their peers [60]. Students’ goals and motivation determine what strategies are appropriate and the level of SRL instruction they require. For example, students with mastery-oriented goals may perceive scaffolding as a constraint and manifest more autonomy in SRL, so teachers should provide more autonomy and less scaffolding to these students [41]. In our study, Student L1 reported having lost her motivation for the course and found that the timetable template offered by her teacher was not as well suited to her as the timetable she had created for herself and had been using. We reviewed the three stages of interviews with Student L1 and triangulated all of her responses at different time points. She can be considered a mastery-oriented learner because first, she manifested autonomy in her learning by creating her own timetable before the teacher asked for it; second, she mentioned that she had created a folder where she listed the required competencies for her future career; and third, she aligned her competencies such as presentation skills with the top performance in the rubrics. According to Ryan and Deci [61], a mastery-oriented learner is likely to need more challenges and require more curiosity and interest to motivate them to learn. Student L1 mentioned in each interview stage that the strategies offered by the teacher and teaching assistants did not contribute much to her SRL. She explained that she had already been using similar strategies. Her lack of curiosity and interest could therefore be because she did not find such strategies challenging. Therefore, when Student L1 sought help from her teacher, she may have been seeking challenge, curiosity, and interest in her learning. Instead of providing her with the same template as other students, the teacher could have assigned her other topics that she would find more interesting, thus allowing the tasks to be performed in a range of ways instead of by filling in the template. Comparatively, students with performance-oriented goals may perceive scaffolding as useful to their success and welcome the external support for their SRL, so teachers should create prompts for these students [41].

The CAMM processes are also affected by students' prior knowledge [e.g., [[42], [62]]]. Taub et al. [42] found that students with little prior knowledge tended to apply more help-seeking strategies in their SRL than those with extensive prior knowledge, who were less likely to seek help and rely more on themselves. They also found that little prior knowledge led students to choose more cognitive strategies, as they needed to learn the content, whereas those with extensive prior knowledge engaged in more metacognitive strategies, as they tended to monitor what they already did and did not know [42]. We found that the student participants' choice of strategies was affected by their prior knowledge. For example, Sarah's students were required to design and implement a workshop. Student S2 had some knowledge and experience of planning a workshop before the course, but Student S4 demonstrated very little prior understanding of the course content. In terms of SRL strategies, Student S2 summarised and monitored what she already knew and did not yet know about designing a workshop, and she preferred searching for information and resources online on her own if she encountered any problems. However, Student S4 felt that searching was not helpful as she did not know where to start; instead, she asked for help from her peers if she encountered difficulties. This observation indicates that teachers must be aware of students' differing prior knowledge, so they can better gauge when and where they should be involved in students' SRL. Teachers should therefore adapt their strategies to their students' individual motivations and provide them with a better experience of SRL.

5.4. Limitations

The case study method has various inherent limitations, which could potentially affect this study, such as a lack of generalisability, bias, weak cause-and-effect relationships, and difficulties in replicating the results [63,64]. In terms of strengthening the generalisability of the study, Argyris [63] suggested that researchers can make further observations and apply a theoretical framework to their studies. We tracked the case university over a comparatively long period of eight months, and we applied Zimmerman's [17] three phases of SRL, which is a widely used theoretical framework, to guide and support the entire study. In addition, to make it easier for future researchers and educators to replicate our study, we strictly followed Yin's [51] case study protocol. However, as it is not an empirical investigation, this study cannot present any cause-and-effect relationship, and bias may have been unavoidably introduced when we interpreted the data collected from the interviews and documents. Nevertheless, researchers have agreed that it is more important to emphasise how participants interpret meanings from their experience than to rely solely on statistics [65]. In this study, we present various understandings and perceptions of promoting SRL at the university level. A statistical analysis might not offer results as rich and contextualised as the original sources [66].

The limitations of this study can provide future research opportunities. First, further empirical studies could investigate SRL in a broader educational context. Educators could also replicate the method used in this study to reveal additional factors that affect the promotion of SRL at the university level.

6. Conclusion

We present an eight-month case study of how SRL has been developed as a pedagogy through the collective endeavour of teachers, researchers, and experts at the university level. We summarise the identified elements of the process of promoting SRL at the case university. The results suggest that the teachers had a good knowledge of teaching SRL strategies, but some of the students failed to effectively transform these strategies into SRL. These findings have implications for the better promotion of SRL at the university level. First, SRL development should be a collective endeavour involving various entities at the university. Second, responsive pedagogy can be integrated into the teaching of SRL strategies so that teachers' feedback can be transformed into students' high self-efficacy and academic achievement. Finally, SRL strategies should be tailored to students’ individual differences, allowing a larger student population to benefit from the SRL experience. Future studies could replicate our method to reveal more factors that contribute to SRL, thus helping us better understand how SRL can be developed as a pedagogy.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Siu-Cheung Kong: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Tingjun Lin: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22115.

Contributor Information

Siu-Cheung Kong, Email: sckong@eduhk.hk.

Tingjun Lin, Email: tlin@eduhk.hk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Anthonysamy L., Koo A.C., Hew S.H. Self-regulated learning strategies in higher education: fostering digital literacy for sustainable lifelong learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020;25:2393–2414. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10201-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miksza P., Blackwell J., Roseth N.E. Self-regulated music practice: microanalysis as a data collection technique and inspiration for pedagogical intervention. J. Res. Music Educ. 2018;66(3):295–319. doi: 10.1177/0022429418788557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmerman B.J. In: Handbook of Self-Regulation. Boekaerts M., Pintrich P.R., Zeidner M., editors. Academic Press; 2000. Attaining self-regulation: a social cognitive perspective; pp. 13–39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman B.J. Becoming a self-regulated learner: an overview. Theor. Pract. 2002;41(2):64–70. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler D.L., Winne P.H. Feedback and self-regulated learning: a theoretical synthesis. Rev. Educ. Res. 1995;65(3):245–281. doi: 10.3102/00346543065003245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humrickhouse E. Flipped classroom pedagogy in an online learning environment: a self-regulated introduction to information literacy threshold concepts. J. Acad. Librarian. 2021;47(2) doi: 10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jansen R.S., van Leeuwen A., Janssen J., Conijn R., Kester L. Supporting learners' self-regulated learning in massive open online courses. Comput. Educ. 2020;146 doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broadbent J., Poon W.L. Self-regulated learning strategies and academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: a systematic review. Internet High Educ. 2015;27:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latif B., Yuliardi R., Tamur M. Computer-assisted learning using the Cabri 3D for improving spatial ability and self-regulated learning. Heliyon. 2020;6(11) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun Z., Xie K., Anderman L.H. The role of self-regulated learning in students' success in flipped undergraduate math courses. Internet High Educ. 2018;36:41–53. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.09.003 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alotumi M. EFL college junior and senior students' self-regulated motivation for improving English speaking: a survey study. Heliyon. 2021;7(4) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun T., Wang C. College students' writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulated learning strategies in learning English as a foreign language. System. 2020;90 doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heale R., Twycross A. What is a case study? Evid. Base Nurs. 2018;21(1):7–8. doi: 10.1136/eb-2017-102845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaarbo J., Beasley R.K. A practical guide to the comparative case study method in political psychology. Polit. Psychol. 1999;20(2):369–391. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boekaerts M., Niemivirta M. In: Handbook of Self-Regulation. Boekaerts M., Pintrich P.R., Zeidner M., editors. Academic Press; 2000. Self-regulated learning: finding a balance between learning goals and ego-protective goals; pp. 417–450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schunk D.H., Zimmerman B.J. Guilford Press; 1998. Self-regulated Learning: from Teaching to Self-Reflective Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmerman B.J. Investigating self-regulation and motivation: historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2008;45(1):166–183. doi: 10.3102/0002831207312909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A. Fearful expectations and avoidant actions as coeffects of perceived self-inefficacy. Am. Psychol. 1986;41(12):1389–1391. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.41.12.1389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schunk D.H. Goal setting and self-efficacy during self-regulated learning. Educ. Psychol. 1990;25(1):71–86. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1207/s15326985ep2501_6 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pintrich P.R. A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2004;16:385–407. doi: 10.1007/s10648-004-0006-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huh Y., Reigeluth C.M. Self-regulated learning: the continuous-change conceptual framework and a vision of new paradigm, technology system, and pedagogical support. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2017;46(2):191–214. doi: 10.1177/0047239517710769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pintrich P.R. Multiple goals, multiple pathways: the role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000;92(3):544. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-0663.92.3.544 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spruce R., Bol L. Teacher beliefs, knowledge, and practice of self-regulated learning. Metacognition and Learning. 2015;10:245–277. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s11409-014-9124-0 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kizilcec R.F., Pérez-Sanagustín M., Maldonado J.J. Self-regulated learning strategies predict learner behavior and goal attainment in massive open online courses. Comput. Educ. 2017;104:18–33. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pintrich P.R., Smith D.A.F., Garcia T., McKeachie W.J. University of Michigan, National Center for Research to Improve Postsecondary Teaching and Learning; Ann Arbor: 1991. A Manual for the Use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinstein C.E., Palmer D.R. second ed. H & H; Clearwater, FL: 2002. Learning and Study Strategies Inventory LASSI User's Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnard L., Lan W.Y., To Y.M., Paton V.O., Lai S.L. Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. Internet High Educ. 2009;12(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abuhassna H., Al-Rahmi W.M., Yahya N., Zakaria M.A.Z.M., Kosnin A.B.M., Darwish M. Development of a new model on utilizing online learning platforms to improve students' academic achievements and satisfaction. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. 2020;17:1–23. doi: 10.1186/s41239-020-00216-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biwer F., Wiradhany W., Oude Egbrink M., Hospers H., Wasenitz S., Jansen W., De Bruin A. Changes and adaptations: how university students self-regulate their online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.642593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kintu M.J., Zhu C., Kagambe E. Blended learning effectiveness: the relationship between student characteristics, design features and outcomes. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. 2017;14(1):1–20. doi: 10.1186/s41239-017-0043-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai C.L., Hwang G.J. A self-regulated flipped classroom approach to improving students' learning performance in a mathematics course. Comput. Educ. 2016;100:126–140. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cassidy S. Self-regulated learning in higher education: identifying key component processes. Stud. High Educ. 2011;36(8):989–1000. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2010.503269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ben Youssef A., Dahmani M., Ragni L. ICT use, digital skills and students' academic performance: exploring the digital divide. Information. 2022;13(3):129. doi: 10.3390/info13030129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hong J.C., Lee Y.F., Ye J.H. Procrastination predicts online self-regulated learning and online learning ineffectiveness during the coronavirus lockdown. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2021;174 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110673. 10.1016%2Fj.paid.2021.110673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dumford A.D., Miller A.L. Online learning in higher education: exploring advantages and disadvantages for engagement. J. Comput. High Educ. 2018;30:452–465. doi: 10.1007/s12528-018-9179-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mega C., Ronconi L., De Beni R. What makes a good student? How emotions, self-regulated learning, and motivation contribute to academic achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014;106(1):121. doi: 10.1037/a0033546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nugent A., Lodge J.M., Carroll A., Bagraith R., MacMahon S., Matthews K., Sah P. The University of Queensland; 2019. Higher Education Learning Framework: an Evidence Informed Model for University Learning. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell J.M., Baik C., Ryan A.T., Molloy E. Fostering self-regulated learning in higher education: making self-regulation visible. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2022;23(2):97–113. doi: 10.1177/1469787420982378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cleary T.J., Kitsantas A., Peters-Burton E., Lui A., McLeod K., Slemp J., Zhang X. Professional development in self-regulated learning: shifts and variations in teacher outcomes and approaches to implementation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022;111 doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ng E.M. Integrating self-regulation principles with flipped classroom pedagogy for first year university students. Comput. Educ. 2018;126:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duffy M.C., Azevedo R. Motivation matters: interactions between achievement goals and agent scaffolding for self-regulated learning within an intelligent tutoring system. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015;52:338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taub M., Azevedo R., Bouchet F., Khosravifar B. Can the use of cognitive and metacognitive self-regulated learning strategies be predicted by learners' levels of prior knowledge in hypermedia-learning environments? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014;39:356–367. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marini J.A.D.S., Boruchovitch E. Self-regulated learning in students of pedagogy. Paideia. 2014;24:323–330. doi: 10.1590/1982-43272459201406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quintão C., Andrade P., Almeida F. How to improve the validity and reliability of a case study approach? Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education. 2020;9(2):264–275. doi: 10.32674/jise.v9i2.2026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin R.K. Validity and generalization in future case study evaluations. Evaluation. 2013;19(3):321–332. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1177/1356389013497081 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alpi K.M., Evans J.J. Distinguishing case study as a research method from case reports as a publication type. J. Med. Libr. Assoc.: JMLA. 2019;107(1):1. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2019.615. 10.5195%2Fjmla.2019.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin R.K. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim D., Yoon M., Jo I.H., Branch R.M. Learning analytics to support self-regulated learning in asynchronous online courses: a case study at a women's university in South Korea. Comput. Educ. 2018;127:233–251. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.023 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laru J., Järvelä S. In: Seamless Learning in the Age of Mobile Connectivity. Wong L.-H., Milrad M., Specht M., editors. Springer; Singapore: 2015. Integrated use of multiple social software tools and face-to-face activities to support self-regulated learning: a case study in a higher education context; pp. 471–484. 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moseki M., Schulze S. Promoting self-regulated learning to improve achievement: a case study in higher education. Afr. Educ. Rev. 2010;7(2):356–375. doi: 10.1080/18146627.2010.515422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yin R.K. sixth ed. Sage Publications; 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patton M.Q. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2015. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dignath-van Ewijk C., Van der Werf G. What teachers think about self-regulated learning: investigating teacher beliefs and teacher behavior of enhancing students' self-regulation. Education Research International. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/741713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith K., Gamlem S.M., Sandal A.K., Engelsen K.S. Educating for the future: a conceptual framework of responsive pedagogy. Cogent Education. 2016;3(1) doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1227021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nicol D. Reconceptualising feedback as an internal not an external process. Italian Journal of Educational Research. 2019:71–84. doi: 10.7346/SIRD-1S2019-P57. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nicol D. In: Advances and Innovations in University Assessment and Feedback. Kreber C., Anderson C., Entwistle N., McArthur J., editors. Edinburgh University Press; 2014. Guiding principles of peer review: unlocking learners' evaluative skills; pp. 197–224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chou C.Y., Zou N.B. An analysis of internal and external feedback in self-regulated learning activities mediated by self-regulated learning tools and open learner models. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. 2020;17(1):1–27. doi: 10.1186/s41239-020-00233-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chou C.Y., Lai K.R., Chao P.Y., Lan C.H., Chen T.H. Negotiation based adaptive learning sequences: combining adaptivity and adaptability. Comput. Educ. 2015;88:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Azevedo R. Using hypermedia as a metacognitive tool for enhancing student learning? The role of self-regulated learning. Educ. Psychol. 2018;40:199–209. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benita M., Roth G., Deci E.L. When are mastery goals more adaptive? It depends on experiences of autonomy support and autonomy. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014;106(1):258. doi: 10.1037/a0034007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ryan R.M., Deci E.L. vols. 171–195. Routledge; 2009. Promoting self-determined school engagement. (Handbook of Motivation at School). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sáiz-Manzanares M.C., Marticorena-Sánchez R., Martín-Antón L.J., Díez I.G., Almeida L. Perceived satisfaction of university students with the use of chatbots as a tool for self-regulated learning. Heliyon. 2023;9(1) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e12843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Argyris C. Some limitations of the case method: experiences in a management development program. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1980;5(2):291–298. doi: 10.2307/257439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yazan B. Three approaches to case study methods in education: Yin, Merriam, and Stake. Qual. Rep. 2015;20(2):134–152. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Charmaz K. Special invited paper: continuities, contradictions, and critical inquiry in grounded theory. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2017;16:1–8. doi: 10.1177/1609406917719350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morse J.M., Barrett M., Mayan M., Olson K., Spiers J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2002;1(2):13–22. doi: 10.1177/160940690200100202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.