Abstract

Weaning stress can induce diarrhea, intestinal damage and flora disorder of piglets, leading to slow growth and even death of piglets. Traditional Chinese medicine residue contains a variety of active ingredients and nutrients, and its resource utilization has always been a headache. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the effects of traditional Chinese medicine residues (Xiasangju, composed of prunellae spica, mulberry leaves, and chrysanthemum indici flos) on growth performance, diarrhea, immune function, and intestinal health in weaned piglets. Forty-eight healthy Duroc× Landrace × Yorkshire castrated males weaned aged 21 days with similar body conditions were randomly divided into 6 groups with eight replicates of one piglet. The control group was fed a basal diet, the antibiotic control group was supplemented with 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline, and the residue treatment groups were supplemented with 0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0% and 4.0% Xiasangju residues. The results showed that dietary Xiasangju residues significantly reduced the average daily feed intake, but reduced the diarrhea score (P < 0.05). The 1.0% and 2.0% Xiasangju residues significantly increased the serum IgM content of piglets, and the 0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0% and 4.0% Xiasangju residues significantly increased the serum IgG content, while the 1.0%, 2.0% and 4.0% Xiasangju residues significantly increased the sIgA content of ileal contents (P < 0.05). Dietary Xiasangju residues significantly increased the villus height and the number of villus goblet cells in the jejunum and ileum, and significantly decreased the crypt depth (P<0.05). The relative mRNA expression of IL-10 in the ileum was significantly increased in the 1% and 2% Xiasangju residues supplemented groups (P < 0.05), while IL-1β in the ileum was downregulated (P < 0.05). Xiasangju residues improved the gut tight barrier, as evidenced by the enhanced expression of Occludin and ZO-1 in the jejunum and ileum. The diets with 1% Xiasangju residues significantly increased the relative abundance of Lactobacillus johnsonii, and 2% and 4% Xiasangju residues significantly increased the relative abundance of Weissella jogaeotgali (P < 0.05). Dietary supplementation with 0.5%, 1.0%, 2% and 4% with Xiasangju residues significantly decreased the relative abundance of Escherichia coli and Treponema porcinum (P < 0.05). In summary, dietary supplementation with Xiasangju residues improves intestinal health and gut microbiota in weaned piglets.

Keywords: traditional Chinese medicine residues, Xiasangju, weaned piglet, weaning stress, gut health, gut microbiota

1. Introduction

With the increasing scale and intensification of pig production, early weaning of piglets has become a major mode to improve production efficiency (Zhao et al., 2019; Ramirez et al., 2022). However, due to the underdeveloped immune function and gastrointestinal digestive function of early weaned piglets, they show high sensitivity to solid feed and pathogenic bacteria, which easily induce weaning stress, further impair gut function and gut microbiota, cause diarrhea, anorexia, listlessness and other symptoms, and reduce production efficiency (Jayaraman and Nyachoti, 2017; Heuß et al., 2019). According to incomplete statistics, the prevalence of diarrhea in early weaned piglets is as high as 20%, resulting in significant economic losses to the pig industry (Hu et al., 2018). While antibiotics and other drugs can alleviate the stress of weaning piglets, long-term use of nonstandard medications has caused some harm, such as bacterial resistance, drug residues, and environmental pollution (Tucker et al., 2021). As a result, the livestock industry is under tremendous pressure to ban antibiotics in feed and reduce them in treatment. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop new strategies to replace drugs such as antibiotics. As a potential green, safe, environmentally friendly and efficient alternative to antibiotics, plant extracts have attracted increasing attention from all sectors of society in feed production and animal husbandry (Zhao et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2022). Plant extracts, including polyphenols, polysaccharides, alkaloids, and other functional components, have been shown to have positive effects on antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antioxidant, growth promotion, immune regulation, and improved gut microbiota in animals (Du et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2022).

Xiasangju is a classic traditional Chinese medicine formula that comprises Prunellae spica, mulberry leaves, and Chrysanthemum indici flos. It was first recorded in the “Analysis of Warm Diseases (Wen Bing Tiao Bian)” of the Qing Dynasty approximately 1798 AD (Wu et al., 2022). Xiasangju is known for its ability to liver-clearing, enhance eyesight, heat-clearing, and detoxification. Recent research has revealed that Xiasangju possesses antibacterial, antiviral, antioxidant, antitumor, immunomodulatory, and liver-protective properties (Xia et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2022). In southern China, Xiasangju has been widely used as a herbal tea formula, and is regularly employed by clinicians to address conditions such as cold, fever, and sore throat (Xia et al., 2017). In recent years, a growing number of Xiasangju extract products have been developed, such as Xiasangju granules, Xiasangju capsules, Xiasangju oral liquids and Xiasangju herbal tea drinks. As a result, China has a large amount of Xiasangju residues to dispose of each year.

In industry, traditional Chinese medicine residues are generally treated as waste, which wastes resources and pollents the environment. Chinese herbal medicine is affected by the extraction process, and the residue of medicinal components still contains a large number of nutrients and bioactive substances (Huang et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2023). Previous research has indicated that Xiasangju contains a diverse array of active ingredients (Wu et al., 2022). Specifically, prunella spica is characterized by the presence of key compounds such as rosaminic acid, luteolin, rutin, and quercetin (Bai et al., 2016). Likewise, chlorogenic acid, rutin, and quercetin serve as the principal active components in mulberry leaves (Ma et al., 2022), while chrysanthemum indici flos includes chlorogenic acid, luteolin, and monoglycosides as its major bioactive constituents (Shao et al., 2020). These active substances have been found to exert various biological effects, including promoting animal growth, relieving diarrhea, acting as antioxidants, mitigating stress, improving intestinal flora, and modulating immune responses (Kuralkar and Kuralkar, 2021; Tsiplakou et al., 2021). Therefore, the application of Chinese medicine residue to animal production is a measure worth promoting, and it is also an important part of the recycling of Chinese medicine residue resources.

Although existing studies support the potential of Xiasangju to ameliorate weaning stress in piglets (Naveed et al., 2018; Canibe et al., 2022; Gao et al., 2022), there is a lack of information on the effects of Xiasangju residues on weaning stress. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the effects of different levels of Xiasangju residues on the health and gut microbiota of weaned piglets, hoping to provide a new strategy for alleviating weaning stress in piglets, promote the development and utilization of Xiasangju residues as feed, and alleviate environmental stress.

2. Materials and methods

This animal study was reviewed and approved by the Hunan Agricultural University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (202105). Written informed consent was obtained from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study.

2.1. Materials

Dried Xiasangju residue (moisture content 6.64 ± 0.34%) was provided by Guangzhou Baiyunshan Xingqun Pharmaceutical Co., LTD. The preparation of the residue was as follows: Prunella, mulberry leaves, and wild chrysanthemums were sampled according to a weight ratio of 500:175:80, and 10 times the water was added. The traditional Chinese medicine was decoction at 100°C for 1.5 hours, 2 times in total, and filtered and dried to obtain the residue of Xiasangju.

2.2. Quantitative analysis of active ingredients in residues

To determine the content of active ingredients in residues, the LC−MS method was selected for quantitative analysis. Five milligrams of linoside, romaricinic acid, isobromaricin, acacetin, caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid, cryptochlorogenic acid, isochlorogenic acid A, isochlorogenic acid B, and isochlorogenic acid C were placed in a 25 mL volumetric flask, and a small amount of methanol was added to dissolve, returned to room temperature, and then volume to the scale line with methanol. A single standard stock solution of 0.2 mg/mL was prepared. More than 200 μL of a single standard stock solution was placed in a 10 mL brown volumetric flask, and methanol was used to make a 4 μg/mL mixed standard stock liquor (the concentration of each component was 4 μg/mL). Then, the above control mixed standard stock solution was diluted to make mixed standard working curve correction solutions of 2 μg/mL, 1 μg/mL, 0.5 μg/mL, 0.2 μg/mL, and 0.1 μg/mL. A linear equation was drawn with the concentration of active ingredients as the abscissa and the peak area of EIC as the ordinate. The concentration of active ingredients in the tested samples was calculated by the standard curve equation. The specific detection parameters are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Quantitative analysis parameters of active components of residue by LC-MS.

| Item | Method description |

|---|---|

| The chromatographic conditions for LC analysis: | |

| Chromatographic column | Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 (2.1 mm × 150 mm, 1.8 μm) |

| Mobile phase: | |

| Aqueous phase (A) | 0.1% formic acid in water |

| Organic phase (B) | Acetonitrile |

| Gradient elution program: | |

| 0-8 min: | 2%-30% B |

| 8-25 min: | 30%-95% B |

| 25-30 min: | 95% B |

| 30.1 to 35 min: | 2% B |

| Column temperature: | 35°C |

| Autosampler temperature: | Room temperature (25 ± 2°C) |

| Flow rate: | 0.3 mL/min |

| Injection volume: | 1 μL |

| DAD (Diode Array Detector) collected data using full-wavelength scanning mode with a scanning range of 210-400 nm. | |

| The high-resolution primary mass spectrometry (HRMS) conditions: | |

| Ion source: | Agilent Dual AJS ESI source |

| Scan mode: | Positive |

| Full sweep range: | m/z 100-1000 |

| Sheath temperature: | 350 °C |

| Sheath gas flow rate: | 11.0 L/min |

| Drying temperature: | 345°C |

| Drying gas pressure: | 45 psi |

| Drying gas flow rate: | 10 L/min |

| Capillary voltage: | 4000 V |

| Fragmentor: | 135 V |

| Data acquisition software: | Agilent MassHunter Acquisition Workstation Software (B.08.00) |

For high-resolution secondary mass spectrometry in target MS/MS mode, the ion source parameters were the same as the primary mass spectrometry conditions. The appropriate collision energy was chosen based on the molecular weight and structural stability of the target compound, within the range of 5 to 45 eV.

2.3. Animals and dietary treatments

Forty-eight healthy Duroc× Landrace × Yorkshire castrated male weanling piglets aged 21 days with similar body conditions were randomly divided into 6 groups, each group of eight repeats each repeat a piglet. The experiment began the next day and lasted for 21 days. The control group was fed a basal diet, the antibiotic control group received 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline (chlortetracycline premix purchased from Zhumadian Huazhong Zhengda Co., LTD.), and the residue treatment groups were supplemented with 0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0% and 4.0% Xiasangju residues. The residues were crushed through a 60-mesh sieve, the basic diet ( Table 2 ) was prepared according to NRC2012, and the nutritional level met the NRC recommendation.

Table 2.

Ingredient composition and nutrient level of the basal diet (%, as-fed basis).

| Ingredients | Content | Nutrient level b | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | 55.00 | Digestible energy, kcal/kg | 3542.1 |

| Fermented soybean meal | 31.00 | Crude protein | 18.51 |

| Soybean oil | 3.00 | Calcium | 0.80 |

| Glucose | 2.00 | Total phosphorus | 0.60 |

| Sucrose | 3.00 | Available phosphorus | 0.38 |

| Limestone | 1.00 | SID Lysine | 0.1.37 |

| CaHPO4 | 1.50 | SID Methionine | 0.53 |

| NaCl | 0.30 | SID Methionine + cystine | 0.0.73 |

| Citric acid | 0.90 | SID Threonine | 0.77 |

| Choline chloride | 0.10 | SID Tryptophan | 0.19 |

| Lysine | 0.60 | ||

| Methionine | 0.30 | ||

| Threonine | 0.30 | ||

| Premix a | 1.00 | ||

| Total | 100.00 |

aPremix provided Cu 126.00 mg/kg diet; Fe 102.00 mg; Zn 106.50 mg; Mn 17.70 mg; I 0.18 mg; Se 0.14 mg; VA 8000U; VB1 1.8 mg; VB2 4.4 mg; VB6 4.4 mg; VB12 0.025 mg; VC 150.00 mg; VD3 1000.00U; 25-OH-D3 0.025 mg; VE 120.00 mg; Pantothenic acid 12.40 mg; Niacinamide 25.00 mg; Folic acid 0.88 mg; Biotin 132.00 mg. bIleal standard digestible amino acids (SID) were calculated values, and the rest were measured values.

2.4. Sample collection

At the end of the experiment, blood samples were taken from the anterior vena cava of all piglets using a 10 ml common blood collection tube, left at room temperature for 20 min, and then centrifuged at 845 rcf (g) for 10 min. The upper serum was collected in sterile frozen tubes, cached in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at -80°C. They were anesthetized with 3% sodium pentobarbital at a dose of 25 mg/kg and killed by exenteration, and the abdominal cavity was opened to separate the viscera and intestine. Two 2 cm pieces of intestinal tissue were taken from the anterior segment of the jejunum and the posterior segment of the ileum, one of which was placed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for subsequent histological analysis. Another portion was quickly cleaned with normal saline, placed in a 2 ml sterile cryostat and stored in liquid nitrogen. Approximately 10 cm of the intestinal tract was taken from the anterior segment of the colon, and a small opening was made with a scalpel, after which the ends were bound together with a string. The gut contents were loaded into a 2 ml sterile cryostat and stored in liquid nitrogen. Furthermore, the ileal digesta was collected in a 2 ml sterile cryostat and stored in liquid nitrogen.

2.5. Growth performance

Each piglet was weighed on day 1 and day 21, and the amount of food supplied and remaining was recorded daily to calculate the average daily feed intake (ADFI), average daily gain (ADG) and feed-to-weight ratio (F/G). The piglets were scored by observing their diarrhea at approximately 15:00 daily, and the scoring criteria were as follows: 1: solid hard stool; 2: slightly loose stool; 3: soft stool, partially formed; 4: semiliquid stool; and 5: stool-water separated, watery, unformed.

2.6. Organ index

After the piglets were slaughtered, the organs were separated, and the surface liquid of the organs was quickly blotted dry with filter paper and then weighed. The formula is as follows: organ index = organ weight (g)/live weight of piglets (kg).

2.7. Serum biochemical parameter analysis

The contents of serum total protein, albumin, total bile acid, glucose, triglyceride, urea nitrogen, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and lactate dehydrogenase were detected by an automatic biochemical analyzer and its matching reagents (KHB 450, Shanghai Kehua bioengineering co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), according to Shi et al. (2022).

2.8. Immunoglobulin analysis

Serum IgA, IgG and IgM levels were detected by ELISA kits (Jiangsu Meimian Industrial Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China), and ileal digesta sIgA content was detected by ELISA kits (Quanzhou Ruixin Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Quanzhou, China). All detection steps were carried out according to the instructions of the kit, according to Yu et al. (2021).

2.9. Intestinal morphology

Following our previous study (Wang et al., 2022), intestinal tissue fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution was cut and dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, dewaxed, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, dehydrated, and sealed with neutral glue. Images were observed and collected with a microscope imaging system (Carl Zeiss, Germany) to measure intestinal villus height (VH) and crypt depth (CD). The ratio of villus height to crypt depth (V/C) was calculated for five randomly selected fields per slice.

2.10. AB-PAS Staining

Following our previous study, tissue paraffin blocks were cut into slices, deparaffinized and rehydrated, stained according to the instructions of the AB-PAS test kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China), sealed with neutral resin, and finally observed and photographed with a Carl Zeiss Microimaging System. Ten intact villi and crypts from each of the piglet samples were selected for goblet cell number determination, and the result was expressed as the number of goblet cells within each villus.

2.11. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Intestine tissue was frozen and ground in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated using RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), followed by reverse transcription using the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Fluorescence quantification was then performed with TB Green® Fast qPCR Mix in a LightCycler 480 System II. The primers used in this study were designed based on porcine sequences ( Table 3 ); PCR cycles and relative expression assays were performed according to our previous study (Yin et al., 2018).

Table 3.

Primers used for gene expression analysis by real-time PCR.

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Product length, bp |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | F: CCTGGACCTTGGTTCTCT | 123 |

| R: GGATTCTTCATCGGCTTCT | ||

| IL-10 | F: TCGGCCCAGTGAAGAGTTTC | 127 |

| R: GGAGTTCACGTGCTCCTTGA | ||

| IL-6 | F: AAATGTCGAGGCCGTGCAGATTAG | 86 |

| R: GGGTGGTGGCTTTGTCTGGATTC | ||

| TNF-α | F: ACAGGCCAGCTCCCTCTTAT | 102 |

| R: CCTCGCCCTCCTGAATAAAT | ||

| ZO-1 | F: TTGATAGTGGCGTTGACA | 126 |

| R: CCTCATCTTCATCATCTTCTAC | ||

| Claudin-1 | F: GCATCATTTCCTCCCTGTT | 97 |

| R: TCTTGGCTTTGGGTGGTT | ||

| Occludin | F: CAGTGGTAACTTGGAGGCGTCTTC | 103 |

| R: CGTCGTGTAGTCTGTCTCGTAATGG | ||

| Mucin2 | F: CTGTGTGGGGCCTGACAA | 65 |

| R: AGTGCTTGCAGTCGAACTCA | ||

| β-actin | F: CTGCGGCATCCACGAAACT | 147 |

| R: AGGGCCGTGATCTCCTTCTG |

IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-10, interleukin-10; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; ZO-1, tight junction protein 1.

2.12. Microbial analysis

Total microbial genomic DNA was extracted from the colonic digesta using the Power Fecal DNA Extraction Kit (MOBIO, USA). Universal primers 341F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’) and 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) were used to amplify the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. After purification, the PCR product was used to construct the library using the NEB NextB UltraTM DNA Library Prep Kit from New England Biolabs, Inc. ‘s Lumina Library Construction Kit. The constructed library is quantized and probed by a Qubit. After eligibility, Illumina MiSeq PE300 was used for on-machine sequencing. The raw sequences were analyzed using QIIME, version 1.7.0. Initial reads were mass filtered, denoised, and assembled, and chimera sequences were removed according to the method of Deblur et al (Callahan et al., 2016). Only ASVs with at least 2 reads and present in more than 2 samples were kept. PICRUSt2 was used to predict gut microbiota function. All data from the NovoMagic cloud platform (https://magic.novogene.com/) were analyzed.

2.13. Statistical analysis

Data on growth performance, organ index, serum parameters, and RT−qPCR were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with SPSS 26.0 statistical software, and multiple comparisons were performed using Duncan’s method. P < 0.05 was considered a significant difference, and P < 0.01 was considered an extremely significant difference. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative analysis of active ingredients in residues

The results of LC-MS quantitative analysis are shown in Table 4 . The main active ingredients in residues included lineside (83.22 ± 56.2 μg/g), rosmarinic acid (25.92 ± 13.47 μg/g), isrosmarinic acid (10.68 ± 4.71 μg/g), caffeic acid (10.18 ± 5.53 μg/g), and several different types of chlorogenic acid (9.08 ± 4.75 μg/g).

Table 4.

Quantitative analysis of active ingredients in the residues of Xiasangju.

| Item | Neochlorogenic acid | Cryptochlorogenic acid | Chlorogenic acid | Caffeic acid | Isochlorogenic acid B | Isochlorogenic acid A | Isochlorogenic acid C | Rosmarinic acid | Isorosmarin | Linarin | Acacetin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | 3.86 ± 1.79 | 3.84 ± 3.01 | 4.25 ± 2.02 | 9.08 ± 4.75 | 1.6 ± 1.01 | 2.38 ± 1.21 | 3.98 ± 1.48 | 25.92 ± 13.47 | 10.68 ± 4.71 | 83.22 ± 56.2 | 10.18 ± 5.53 |

The mean value (n = 15) was used for the quantitative analysis of active ingredients in the residues of Xiasangju.

3.2. Growth performance and diarrhea score

The results of growth performance and diarrhea score are shown in Table 5 . Compared with the control group, Xiasangju residues had no significant effect on the final test body weight, average daily gain or feed/gain of weanling piglets (P > 0.05). Adding 0.5%, 1.0%, and 2.0% Xiasangju residues significantly reduced the diarrhea score of piglets (P < 0.05), and the effect was equivalent to chlortetracycline.

Table 5.

Effect of Xiasangju residues on the growth performance and diarrhea score of weaned piglets.

| Item | CON | AUR | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial body weight(kg) | 6.82 ± 0.03 | 6.83 ± 1.06 | 6.94 ± 1.07 | 6.82 ± 0.97 | 6.77 ± 1.04 | 6.94 ± 0.91 | 1.000 |

| Final body weight(kg) | 11.46 ± 0.34 | 11.24 ± 1.36 | 10.77 ± 1.86 | 11.00 ± 0.18 | 11.23 ± 1.20 | 10.43 ± 0.42 | 0.932 |

| ADG(kg/d) | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.368 |

| ADFI(kg/d) | 0.49 ± 0.02a | 0.42 ± 0.00b | 0.40 ± 0.03b | 0.39 ± 0.03b | 0.42 ± 0.03b | 0.41 ± 0.01b | 0.049 |

| F/G | 2.21 ± 0.06 | 2.01 ± 0.14 | 2.20 ± 0.29 | 1.99 ± 0.24 | 2.00 ± 0.06 | 2.50 ± 0.25 | 0.197 |

| Diarrhea score | 3.88 ± 0.07a | 3.14 ± 0.01cd | 3.23 ± 0.17bcd | 3.08 ± 0.31d | 3.50 ± 0.01bc | 3.56 ± 0.06ab | 0.011 |

CON, basal diet fed; AUR, 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline added to the basal diet; X1, 0.5% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X2, 1.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X3, 2.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X4, 4.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal die; ADG, average daily gain; ADFI, average daily feed intake; F/G, the ratio of feed intake to gain.

The mean values of the same row of data without the same superscript letter were significantly different at the P-value (n=6).

3.3. Organ index

As shown in Table 6 , Xiasangju residues and chloromycetin had no significant effect on the liver index, kidney index or spleen index of piglets compared with the control group (P > 0.05).

Table 6.

Effect of Xiasangju residues on the organ indices of weaned piglets.

| Item | CON | AUR | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver index | 28.25 ± 1.58 | 25.96 ± 2.08 | 25.92 ± 2.29 | 27.49 ± 4.16 | 25.52 ± 3.53 | 28.64 ± 3.04 | 0.187 |

| Renal index | 5.83 ± 0.75 | 5.98 ± 1.09 | 5.52 ± 0.36 | 6.08 ± 0.33 | 6.24 ± 0.68 | 5.65 ± 1.69 | 0.717 |

| Spleen index | 2.00 ± 0.47 | 2.30 ± 0.56 | 2.17 ± 0.35 | 2.37 ± 0.58 | 2.12 ± 0.20 | 2.49 ± 1.39 | 0.781 |

CON, basal diet fed; AUR, 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline added to the basal diet; X1, 0.5% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X2, 1.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X3, 2.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X4, 4.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal die.

3.4. Serum biochemical parameters

Table 7 shows the effect of the Xiasangju residues on the serum biochemical parameters of piglets. In terms of serum enzyme content, compared with the control group, adding 0.5% and 2.0% Xiasangju residues could significantly reduce the content of AST (P < 0.05). Adding 0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0% and 4.0% Xiasangju residues significantly reduced the ALP content (P < 0.05), and adding 2.0% Xiasangju residues significantly reduced the LDH content (P < 0.05).

Table 7.

Effect of Xiasangju residues on serum biochemical parameters of weaned piglets.

| Item | CON | AUR | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT(U/L) | 68.89 ± 13.28 | 68.52 ± 15.40 | 55.84 ± 9.73 | 58.69 ± 16.44 | 52.79 ± 12.32 | 65.66 ± 10.10 | 0.208 |

| AST(U/L) | 157.09 ± 51.52a | 145.20 ± 44.60ab | 100.14 ± 18.76bc | 124.66 ± 38.70abc | 80.09 ± 10.60c | 121.53 ± 43.49abc | 0.032 |

| ALP(U/L) | 402.95 ± 49.96a | 305.58 ± 44.09b | 242.19 ± 34.40c | 313.63 ± 38.00b | 294.08 ± 39.65b | 274.12 ± 26.47bc | 0.000 |

| LDH(U/L) | 815.67 ± 146.01a | 703.33 ± 133.54ab | 666.67 ± 170.99ab | 845.00 ± 197.40a | 583.17 ± 54.47b | 730.17 ± 125.71ab | 0.042 |

| TBA(umol/L) | 63.54 ± 13.10 | 56.09 ± 11.15 | 60.24 ± 18.36 | 58.27 ± 20.90 | 46.60 ± 5.03 | 71.72 ± 13.58 | 0.111 |

| TP(g/L) | 48.80 ± 6.40a | 32.86 ± 4.14b | 58.04 ± 11.12a | 57.71 ± 11.18a | 54.01 ± 5.80a | 54.77 ± 2.65a | 0.000 |

| ALB(g/L) | 9.87 ± 2.43c | 11.95 ± 1.28c | 8.23 ± 1.44c | 27.65 ± 4.68b | 31.91 ± 4.41a | 34.48 ± 3.91a | 0.000 |

| GLB(g/L) | 36.86 ± 5.81b | 17.17 ± 6.40d | 50.00 ± 10.35a | 32.50 ± 16.69bc | 22.33 ± 4.37cd | 20.50 ± 2.07d | 0.000 |

| A/G | 0.28 ± 0.13c | 0.46 ± 0.18c | 0.17 ± 0.04c | 1.24 ± 0.55b | 1.57 ± 0.24a | 1.59 ± 0.28a | 0.000 |

| GLU(mmol/L) | 5.22 ± 0.89b | 4.97 ± 0.34b | 5.43 ± 0.33b | 5.44 ± 0.63b | 5.28 ± 0.89b | 6.52 ± 1.08a | 0.023 |

| BUN(mmol/L) | 5.85 ± 1.18ab | 6.07 ± 0.96a | 5.71 ± 0.47abc | 4.68 ± 1.00cd | 4.55 ± 0.59d | 4.85 ± 0.91bcd | 0.015 |

| TC(mmol/L) | 2.31 ± 0.27a | 1.85 ± 0.35b | 2.33 ± 0.23a | 2.21 ± 0.18a | 2.11 ± 0.26ab | 2.16 ± 0.35ab | 0.062 |

| TG(mmol/L) | 0.85 ± 0.14 | 0.87 ± 0.33 | 0.73 ± 0.20 | 0.81 ± 0.25 | 0.76 ± 0.26 | 0.73 ± 0.29 | 0.874 |

| HDL-C(mmol/L) | 0.78 ± 0.09a | 0.62 ± 0.07b | 0.81 ± 0.04a | 0.79 ± 0.03a | 0.87 ± 0.19a | 0.81 ± 0.23a | 0.048 |

| LDL-C(mmol/L) | 2.07 ± 0.37a | 1.34 ± 0.39b | 2.18 ± 0.44a | 1.12 ± 0.32bc | 0.90 ± 0.08c | 0.93 ± 0.20c | 0.000 |

CON, basal diet fed; AUR, 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline added to the basal diet; X1, 0.5% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X2, 1.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X3, 2.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X4, 4.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal die; ALT, glutamic-pyruvic transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; LDH, lactic dehydrogenase; TBA, total bile acid; TP, total protein; ALB, albumin; GLB, globulin; A/G, albumin/globulin; GLU, glucose; BNU, blood urea nitrogen; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

The mean values of the same row of data without the same superscript letter were significantly different at the P-value (n=6).

In terms of serum protein content, compared with the control group, the content of albumin was significantly increased by adding 1.0%, 2.0% and 4.0% Xiasangju residues (P < 0.05), the content of globulin was significantly increased by adding 0.5% Xiasangju residues (P < 0.05), and the content of globulin was significantly decreased by adding 2.0% and 4.0% Xiasangju residues (P < 0.05). At the same time, the ratio of albumin to globulin was significantly increased by 1.0%, 2.0% and 4.0% Xiasangju residues (P < 0.05).

In terms of glucose and lipid metabolism, supplementation with 2.0% and 4.0% Xiasangju residues significantly reduced serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol content (P < 0.05), while 4.0% Xiasangju residues significantly increased serum glucose content (P < 0.05). In addition, the serum urea nitrogen content was significantly reduced by adding 1.0%, 2.0% and 4.0% Xiasangju residue (P < 0.05).

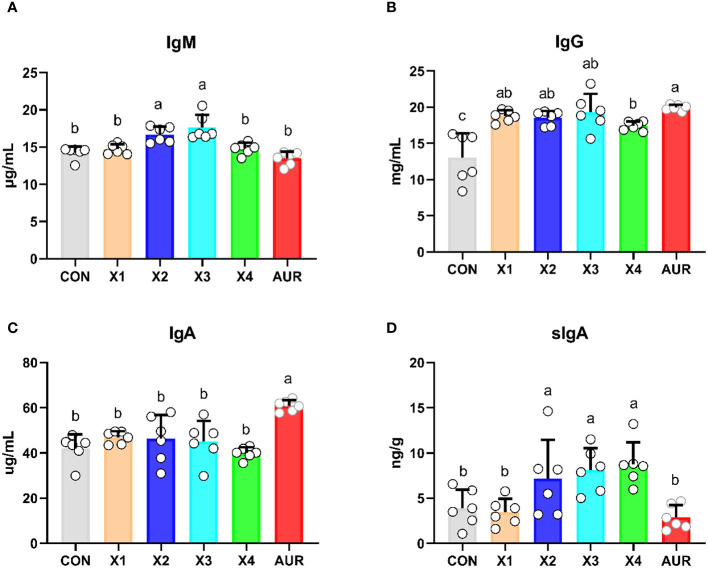

3.5. Immunoglobulin content

As shown in Figure 1 , compared with the control group, the addition of 1% and 2% Xiasangju residues significantly increased the serum IgM level (P < 0.05), the addition of 0.5%, 1%, 2% and 4% Xiasangju residues all increased the serum IgG level (P < 0.05), and the addition of 1%, 2% and 4% Xiasangju residues all increased the level of sIgA in the ileum contents of piglets (P < 0.05), while the effect of Xiasangju residues on the serum IgA level was not significant (P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effect of Xiasangju residues on immunoglobulin content in weaned piglets. (A), serum immunoglobulin A content. (B) Serum immunoglobulin G content. (C) serum immunoglobulin A content. (D) secretory immunoglobulin A content of ileal contents. CON, basal diet fed; AUR, 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline added to the basal diet; X1, 0.5% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X2, 1.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X3, 2.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X, 4.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal die; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgA, immunoglobulin A; sIgA, secretory immunoglobulin A. Means without the superscript same letter were significantly different at the P-value(n=6).

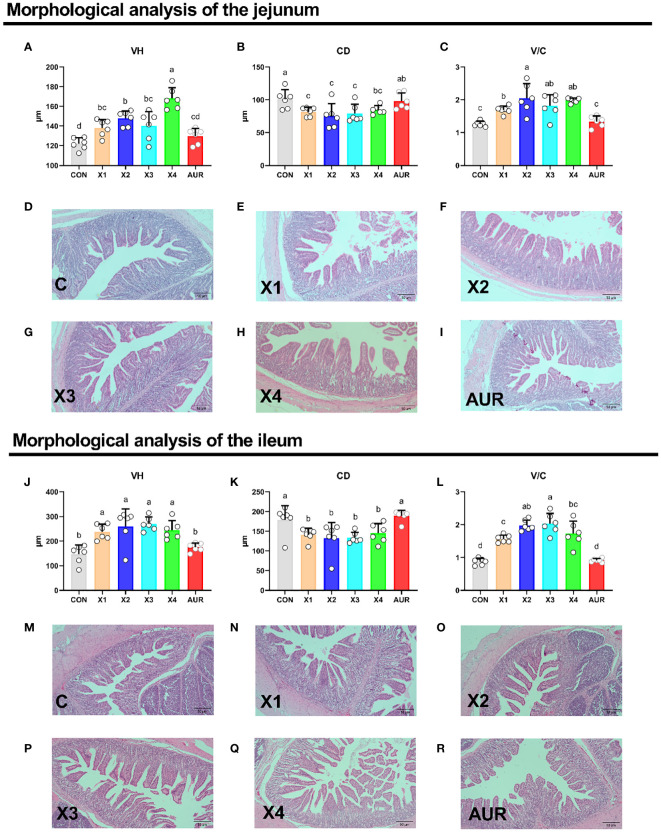

3.6. Intestinal morphology

As shown in Figure 2 , the addition of 0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0% and 4% Xiasangju residues to the diet of weaned piglets significantly increased VH and V/C and decreased CD in the jejunum and ileum of the piglets compared to the control group (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effect of Xiasangju residues on intestinal morphology in weaned piglets. (A–C) are the villus height, crypt depth and villus height/crypt depth of jejunum tissue of weaned piglets, respectively. (D–I) shows HE stained sections of jejunal tissues with different treatments. (J–L) are the villus height, crypt depth and villus height/crypt depth of the ileum tissue of weaned piglets, respectively. (M–R) shows HE stained sections of different treatments of ileal tissues. CON, basal diet fed; AUR, 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline added to the basal diet; X1, 0.5% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X2, 1.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X3, 2.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X4, 4.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; VH, villous height; CD, crypt depth; V/C, villous height/crypt depth. Means without the same superscript letter were significantly different at the P-value (n=6).

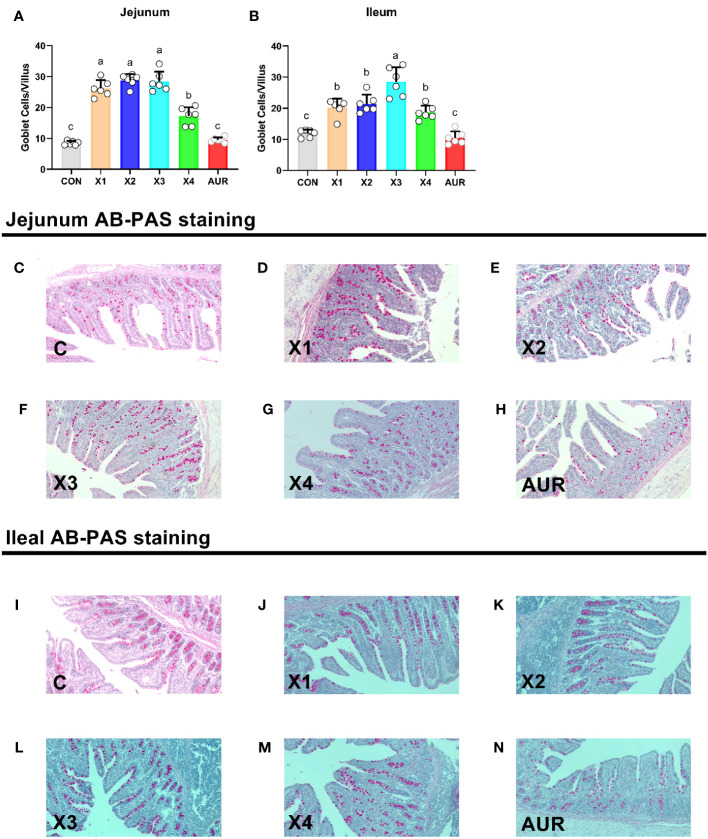

3.7. Goblet cells

As shown in Figure 3 , the addition of 0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0% and 4% Xiasangju residues to the diet of weaned piglets significantly increased goblet cells in the jejunum and ileum of the piglets compared to the control group (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effect of Xiasangju residues on intestinal goblet cells in weaned piglets. (A, B) are the number of villus goblet cells in jejunum and ileum of weaned piglets, respectively. (C–H) shows AB-PAS stained sections of jejunal tissues with different treatments. (I–N) are AB-PAS stained sections of ileum tissue from weaned piglets. CON, basal diet fed; AUR, 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline added to the basal diet; X1, 0.5% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X2, 1.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X3, 2.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X4, 4.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet. Means without the same superscript letter were significantly different at the P-value (n=6).

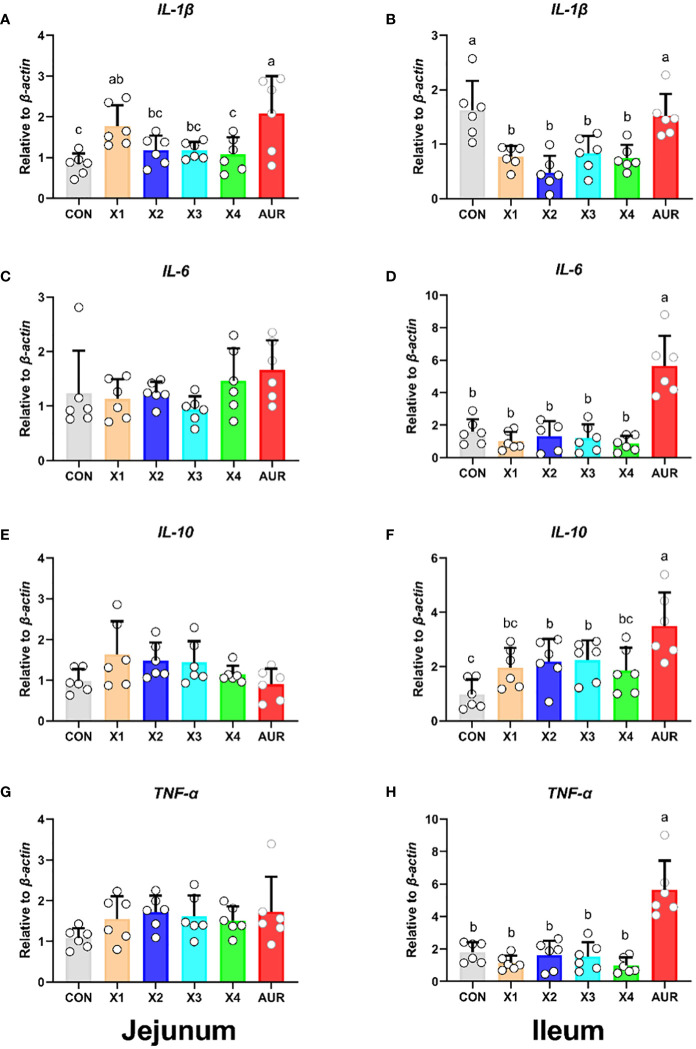

3.8. Expression of inflammation-related genes

As shown in Figure 4 , 0.5% Xiasangju residues significantly increased jejunal IL-1β relative expression compared with the control group (P < 0.05), although Xiasangju residues had no significant effect on jejunal IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α relative expression (P > 0.05). Interestingly, 0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0%, and 4.0% Xiasangju residues significantly decreased ileal IL-1β relative expression, and 1.0% and 2.0% Xiasangju residues significantly increased IL-10 relative expression (P < 0.05), with nonsignificant effects on IL-6 and TNF-α (P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect of Xiasangju residues on the expression of intestinal inflammation-related genes in weaned piglets. (A, C, E, G) are the relative expression of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α in jejunum tissue, respectively. (B, D, F, H) are the relative expression of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α in ileum tissue, respectively. CON, basal diet fed; AUR, 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline added to the basal diet; X1, 0.5% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X2, 1.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X3, 2.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X4, 4.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; IL-1β, interleukin-1 beta; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-10, interleukin-10; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha. Means without the same superscript letter were significantly different at the P-value (n=6).

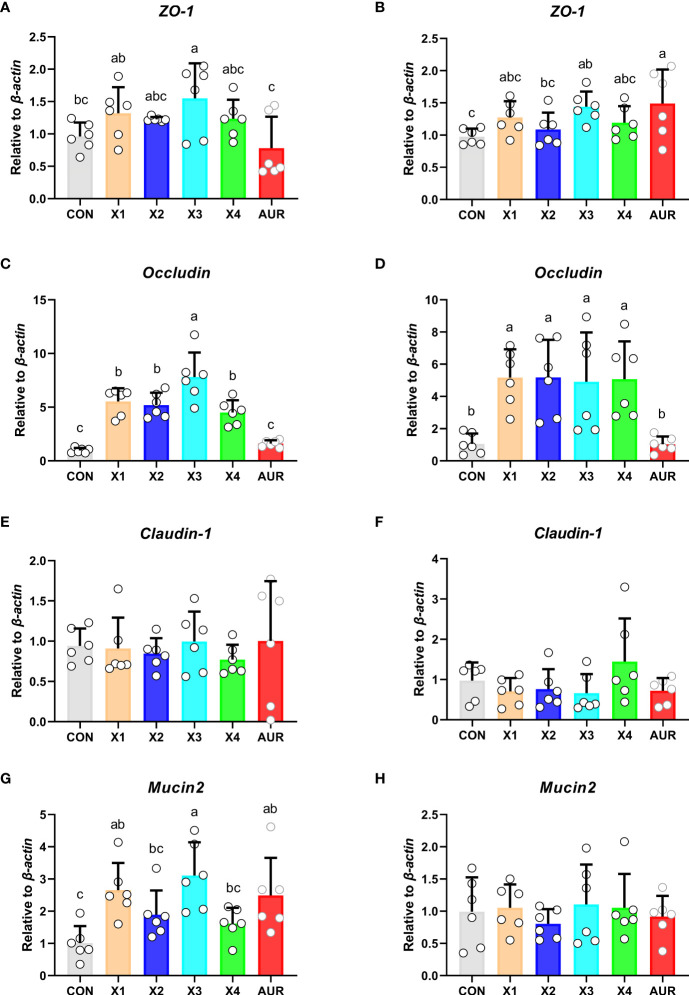

3.9. Expression of intestinal barrier-related genes

Compared with the control group, treatment with 2% significantly increased the relative expression of ZO-1 in the jejunum and ileum ( Figures 5A, B ) (P < 0.05), treatment with 0.5%, 1%, 2.0%, and 4% significantly increased the relative expression of Occludin in the jejunum and ileum ( Figures 5C, D ) (P < 0.05), and treatment with 0.5% and 2% significantly increased the relative expression of Mucin2 in the jejunum ( Figure 5G ) (P < 0.05). Claudin-1 in the jejunum and ileum ( Figures 5E, F ) and Mucin2 in the ileum ( Figure 5H ) did not have a significant effect (P > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effect of Xiasangju residues on the expression of genes related to intestinal barrier in weaned piglets. (A, C, E, G) are the relative expressions of ZO-1, Occludin, Claudin-1 and Mucin2 in jejunum tissue, respectively. (B, D, F, H) are the relative expressions of ZO-1, Occludin, Claudin-1 and Mucin2 in ileum tissue, respectively. CON, basal diet fed; AUR, 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline added to the basal diet; X1, 0.5% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X2, 1.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X3, 2.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X4, 4.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; ZO-1, tight junction protein 1. Means without the same superscript letter were significantly different at the P-value (n=6).

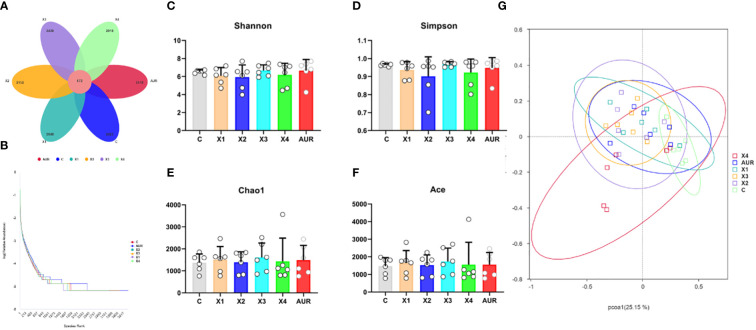

3.10. Colonic bacterial richness, diversity, and similarity

To investigate the effect of dietary therapy on the bacterial community of the piglets, 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed on a colonic digested sample of the piglets on day 21 of the trial ( Figure 6 ). A total of 13951 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were identified in chyme of the colon, with a total of 672 OTUs. Compared to the control group, the unique OTUs in the Xiasangju residues treatment group initially increased with increasing concentration and then decreased at 4%. There were 405 more unique OTUs in the 3% Xiasangju residue treatment group than in the control group. Alpha diversity is a basic indicator for evaluating bacterial richness and diversity, and Shannon, Simpson, Chao1, and Ace indices were not significantly different among treatments in this experiment. Subsequently, Bray−Curtis was used to analyze the β diversity of the microbiota in the colonic chyme of piglets, and no significant difference was found among all treatments.

Figure 6.

Abundance, diversity and similarity of colonic microbiota (n=6). (A), petal plot of the number of common and uniquely observed taxonomic units (OTUs) in the colonic contents of weaned piglets on day 21 of the experiment. (B), Rank Abundance curves of gut microbiota in the colonic contents of weaned piglets on day 21 of the experiment. (C–F) are the Shannon index, Simpson index, Chao1 index, and ACE index of the colonic microbiota of weaned piglets on day 21 of the experiment, respectively. (G) shows principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plot of the gut microbiota in the colonic contents of weaned piglets on day 21 of the experiment. CON, basal diet fed; AUR, 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline added to the basal diet; X1, 0.5% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X2, 1.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X3, 2.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X4, 4.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet.

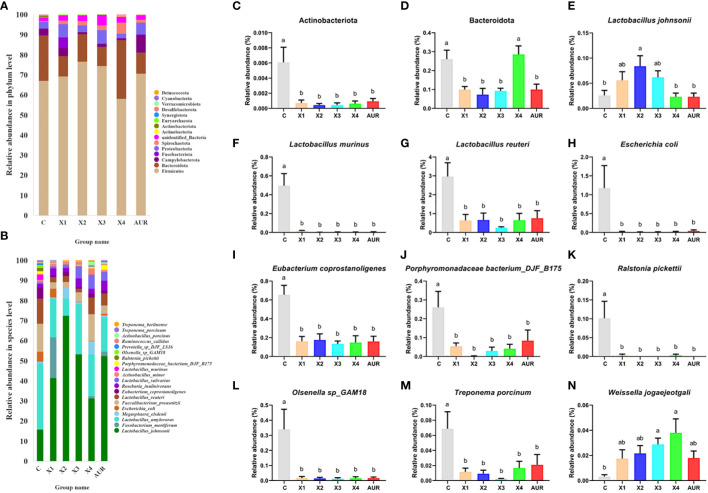

3.11. Colonic microbiota composition

Next, we assessed the colonic microbiota composition of weaned piglets at both the phylum and species levels ( Figure 7A ). At the phylum level, Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Campylobacterota, Fusobacteriota, Proteobacteria, Spirochaetota, unidentified_Bacteria, Actinobacteria, Actinobacteriota and Euryarchaeota were the main components of the colonic microbiota. Notably, Actinobacteriota and Bacteroidota were significantly decreased by 0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0%, and 4% Xiasangju residues and 0.5%, 1.0%, and 2.0% Xiasangju residues, respectively, compared with the control (P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Structure of colon microbiota (n=6). (A, B) shows the TOP20 species composition at the phylum level and species level of the piglet colon, respectively. (C–N) represents the relative abundance of Actinobacteriota, Bacteroidota, Lactobacillus johnsonii, Lactobacillus murinus, Lactobacillus reuteri, Escherichia coli, Eubacterium coprostanoligenes, Porphyromonadaceae bacterium_DJF_B175, Ralstonia pickettii, Olsenella sp_GAM18, Treponema porcinum and Weissella jogaeotgali, respectively. CON, basal diet fed; AUR, 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline added to the basal diet; X1, 0.5% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X2, 1.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X3, 2.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet; X4, 4.0% Xiasangju residues added to the basal diet. Means without the same superscript letter were significantly different at the P-value (n=6).

At the species level, the Xiasangju residues significantly altered the colonic microbiota structure of the piglets ( Figure 7B ). The 1% Xiasangju residues significantly increased the abundance of Lactobacillus johnsonii, and the 2% and 4% Xiasangju residues significantly increased the abundance of Weissella jogaeotgali compared to the control group (P < 0.05). Interestingly, the abundance of Lactobacillus murinus, Lactobacillus reuteri, Escherichia coli, Eubacterium coprostanoligenes, Porphyromonadaceae bacterium_DJF_B175, Ralstonia pickettii, Olsenella sp_GAM18, and Treponema porcinum was significantly reduced in all treatments (P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

Intracellular damage and the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria are often induced by changes in the feed, physiology, psychology and environment of piglets after weaning, resulting in diarrhea and reduced growth performance of piglets, resulting in significant economic losses in pig breeding (Li et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2022). In the current context of antibiotic-free pig diets and treatment with few antibiotics, it is particularly important to find nutritional regulation measures to alleviate the stress of weaning in piglets. Previous studies have shown that adding Chinese herbal medicines to feed improves the growth performance of piglets, increases the feed-to-gain ratio, and reduces diarrhea rates (Canibe et al., 2022). In this study, we found that the residues of Xiasangju contain high contents of linoside, rosmarinic acid, isogrosmarinic acid, acacetin, caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid, cryptochlorogenic acid, isochlorogenic acid A, isochlorogenic acid B and isochlorogenic acid C. Most of these substances have anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and antioxidant effects. However, there is no report on the application of Xiasangju residues in livestock and poultry production. In the present trial, we observed that supplementation with 0.5%, 1.0%, and 2.0% of the Xiasangju residues significantly reduced the diarrhea score of the piglets, similar to the results of chlortetracycline. After weaning, piglets are prone to diarrhea due to changes in dietary status and environment, their own digestive systems are not fully developed, their resistance is weak, and the condition can even be life threatening (Jayaraman and Nyachoti, 2017; Gao et al., 2019). In the present study, supplementation of weaned piglets with Xiasangju residues significantly reduced the diarrhea score of the piglets. The reduction in diarrhea in weanling piglets caused by Xiasangju residues may be due to the presence of lutein, caffeic acid, and chlorogenic acid, which inhibit pathogenic bacteria (Köksal et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022), are anti-inflammatory and improve the intestinal barrier (Naveed et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2023), as also confirmed in this study.

Serum biochemical parameters are important indicators for the clinical assessment of animal health and metabolic status. AST, ALP, and LDH are intracellular enzymes that are released into the blood when cells are damaged (Zaitsev et al., 2021). In the present study, serum AST, ALP, and LDH were significantly reduced by the addition of Xiasangju residues, suggesting that Xiasangju residues are beneficial for liver and cardiac health in weaned piglets. At the same time, Xiasangju residues also improved ALB, BUN, GLU, and LDL-C, suggesting that Xiasangju residues may be beneficial for glucose and lipid metabolism and protein metabolism in piglets. Chen et al. also observed an increase in serum ALB and a decrease in BUN in weaned piglets supplemented with chlorogenic acid, similar to the results of the present study (Chen et al., 2018a). They are the main antibodies involved in the body’s immune response. IgA, IgG and IgM are the main immunoglobulins in animal serum, of which IgG and IgM help the body defend against the invasion of bacteria and viruses, and IgA has the immunological activity of IgG and IgM (Castro-Dopico and Clatworthy, 2019; Perše and Večerić-Haler, 2019). In this study, we observed that the presence of heparin residue increases the serum IgM and IgG contents of piglets, suggesting that heparin residue may improve the immune capacity of piglets. Some studies have also observed an immune-boosting effect of Xiasangju residues in chickens, rabbits, and fish (Chen et al., 2022; Jin et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022). Secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) is an important antibody in the intestinal tract. It recognizes lipopolysaccharides, capsular polysaccharides, and flagellins on the surface of some bacteria, forms sIgA to coat the bacteria, prevents pathogens from contacting intestinal epithelial cells, enhances intestinal barrier function, reduces the pathogen proinflammatory response, and thus protects the intestinal tract (Ding et al., 2021; Seikrit and Pabst, 2021). In the present study, supplementation of the diet of weanling piglets with 1%, 2% and 4% Xiasangju residues significantly increased the sIgA content of ileus digesta, suggesting that Xiasangju residues are beneficial to the immunity of the mucosal lining of the gut of weanling piglets.

The intestine is the main site of nutrient digestion and absorption and is composed of villi and crypts covered by a single layer of columnar epithelial cells. Changes in its structure directly affect the digestion and absorption of nutrients. However, early weaning stress can damage the gut structure of the piglet, mainly by reducing the height of the villus and deepening the crypt depth (Cao et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2022). In this experiment, supplementation with Xiasangju residues significantly increased the villous height of the jejunum and ileum, significantly decreased the crypt depth, and significantly increased the ratio of villous height to crypt depth, suggesting that Xiasangju residues are beneficial in improving intestinal structural damage in weanling piglets. Chlorogenic acid, which is the main active ingredient in Xiasangju residues, has been reported to increase the ratio of villus height and crypt depth in the small intestine of piglets and to decrease crypt depth (Zhang et al., 2018; Qin et al., 2023). Goblet cells are the most abundant secretory cells in the epithelium of the gut and mainly secrete trefoil factor and mucin 2. They are essential for clearing the gut epithelium of external pathogens and allergens, so they protect against many potential threats (Birchenough et al., 2015; Gustafsson and Johansson, 2022). In the present study, Xiasangju residues significantly increased the number of goblet cells in the jejunum and ileum villi of weanling piglets, suggesting that Xiasangju residues are beneficial for the proliferation of goblet cells (Qin et al., 2023).

The mechanical barrier is the first line of defense to prevent harmful substances from invading the intestinal mucosa and disrupting intestinal homeostasis. The mechanical barrier consists mainly of tight junctions between the epithelium and cells of the gut mucosa, mainly containing claudin, occludin, and zonula occludens, which are the main determinants of the mechanical barrier (Okumura and Takeda, 2017; Sylvestre et al., 2023). Previous studies have shown that traditional Chinese medicine and the plant extract cacao can improve the mechanical barrier and maintain intestinal barrier function by regulating intestinal mucosal epithelial cells and intercellular junctions, increasing intestinal mucosal blood flow, and promoting intestinal peristalsis (Che et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). In this study, supplementation of Xiasangju residues to the diet of weanling piglets increased the relative mRNA expression of ZO-1 and Occludin in the jejunum and ileum, and jejunum Mucin2 was also significantly increased when Xiasangju residues were added to the diet of weanling piglets, indicating that Xiasangju residues were beneficial to the intestinal barrier function of piglets. Cytokines also play an important role in the regulation of the intestinal tight junction barrier (Chen et al., 2021). Previous studies have shown that the active ingredient in Xiasangju residues has a good anti-inflammatory effect, increasing the expression and secretion of anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-10 and decreasing the expression and secretion of pro-inflammatory factors (Chen et al., 2018b; Formiga et al., 2020; Zielińska et al., 2021). In this study, we also observed that Xiasangju residues could increase the relative expression of IL-10 mRNA and decrease the relative expression of IL-1β mRNA in the ileum, indicating that Xiasangju residues could improve the inflammatory state of weanling piglets.

The gut microbiome plays an important role in the digestion and absorption of nutrients and in animal health. Early weaning can lead to a disturbed gut flora in piglets, and rapid proliferation of intestinal pathogens such as Escherichia coli can cause weaning diarrhea (Gresse et al., 2017; Guevarra et al., 2019). In this study, while the alpha and beta diversity of the colonic microbiome of Weissella jogaeotgali and Lactobacillus johnsonii was not significantly affected at the species level, the relative abundance of two typical probiotics, Lactobacillus johnsonii and Weissella jogaeotgali, was increased at the species level. At the same time, it reduced the relative abundance of Escherichia coli and Treponema porcinum, indicating that Xiasangju residues can improve the gut microbiota of weaned piglets, which may be one of the main reasons that Xiasangju residues improve diarrhea and the intestinal barrier of piglets, but further verification is needed. The dietary fiber and active ingredients in the residue may be beneficial for the growth and proliferation of Lactobacillus johnsonii and Weissella jogaeotgali, among others. At the same time, the growth of pathogenic bacteria is inhibited (Makki et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2023). Lactobacillus johnsonii and Weissella jogaeotgali are two important probiotics that produce acid, inhibit bacteria and have good adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells. It performs well in improving the structure of the gut microbiota and enhancing the integrity of the intestinal barrier (Teixeira et al., 2021; Bai et al., 2022; Han et al., 2022; Fanelli et al., 2023).

5. Conclusion

In summary, dietary supplementation with Xiasangju residues alleviates diarrhea caused by early weaning, improves intestinal barrier and immune status, and modulates gut microbiota composition, suggesting that Xiasangju residues have some potential as an antibiotic alternative. However, this study was only a preliminary study and the Xiasanju residues did not have a significant effect on the weight gain and feed/gain of the piglets. Large groups and long-term feeding trials are necessary in the future.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: NCBI, PRJNA1011898.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Hunan Agricultural University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (202105). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

WS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZC: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZH: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing. AW: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. MZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JG: Writing – review & editing.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

Author WS, ZH and AW are employed by Guangzhou Baiyunshan Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Bai Y., Lyu M., Fukunaga M., Watanabe S., Iwatani S., Miyanaga K., et al. (2022). Lactobacillus johnsonii enhances the gut barrier integrity via the interaction between GAPDH and the mouse tight junction protein JAM-2. Food Funct. 13, 11021–11033. doi: 10.1039/d2fo00886f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Xia B., Xie W., Zhou Y., Xie J., Li H., et al. (2016). Phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of the genus Prunella. Food Chem. 204, 483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.02.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchenough G. M., Johansson M. E., Gustafsson J. K., Bergström J. H., Hansson G. C. (2015). New developments in goblet cell mucus secretion and function. Mucosal Immunol. 8, 712–719. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan B. J., McMurdie P. J., Rosen M. J., Han A. W., Johnson A. J., Holmes S. P. (2016). DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canibe N., Højberg O., Kongsted H., Vodolazska D., Lauridsen C., Nielsen T. S., et al. (2022). Review on preventive measures to reduce post-weaning diarrhoea in piglets. Anim. (Basel) 12 (19), 2585. doi: 10.3390/ani12192585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S., Hou L., Sun L., Gao J., Gao K., Yang X., et al. (2022). Intestinal morphology and immune profiles are altered in piglets by early-weaning. Int. Immunopharmacol. 105, 108520. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Dopico T., Clatworthy M. R. (2019). IgG and fcγ Receptors in intestinal immunity and inflammation. Front. Immunol. 10. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che Q., Luo T., Shi J., He Y., Xu D.-L. (2022). Mechanisms by which traditional chinese medicines influence the intestinal flora and intestinal barrier. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 12. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.863779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Li Y., Yu B., Chen D., Mao X., Zheng P., et al. (2018. a). Dietary chlorogenic acid improves growth performance of weaned pigs through maintaining antioxidant capacity and intestinal digestion and absorption function. J. Anim. Sci. 96, 1108–1118. doi: 10.1093/jas/skx078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Song Z., Ji R., Liu Y., Zhao H., Liu L., et al. (2022). Chlorogenic acid improves growth performance of weaned rabbits via modulating the intestinal epithelium functions and intestinal microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1027101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Yu B., Chen D., Huang Z., Mao X., Zheng P., et al. (2018. b). Chlorogenic acid improves intestinal barrier functions by suppressing mucosa inflammation and improving antioxidant capacity in weaned pigs. J. Nutr. Biochem. 59, 84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Yu B., Chen D., Zheng P., Luo Y., Huang Z., et al. (2019). Changes of porcine gut microbiota in response to dietary chlorogenic acid supplementation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 8157–8168. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-10025-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Cui W., Li X., Yang H. (2021). Interaction between commensal bacteria, immune response and the intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Immunol. 12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.761981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding M., Yang B., Ross R. P., Stanton C., Zhao J., Zhang H., et al. (2021). Crosstalk between sIgA-coated bacteria in infant gut and early-life health. Trends Microbiol. 29, 725–735. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2021.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J.-H., Xu M.-Y., Wang Y., Lei Z., Yu Z., Li M.-Y. (2022). Evaluation of Taraxacum mongolicum flavonoids in diets for Channa argus based on growth performance, immune responses, apoptosis and antioxidant defense system under lipopolysaccharide stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 131, 1224–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2022.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli F., Montemurro M., Verni M., Garbetta A., Bavaro A. R., Chieffi D., et al. (2023). Probiotic potential and safety assessment of type strains of weissella and periweissella species. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0304722. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03047-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formiga Rd, Alves Júnior E. B., Vasconcelos R. C., Guerra G. C., Antunes de Araújo A., de Carvalho T. G., et al. (2020). p-cymene and rosmarinic acid ameliorate TNBS-induced intestinal inflammation upkeeping ZO-1 and MUC-2: role of antioxidant system and immunomodulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (16), 5870. doi: 10.3390/ijms21165870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Yang Z., Zhao C., Tang X., Jiang Q., Yin Y. (2022). A comprehensive review on natural phenolic compounds as alternatives to in-feed antibiotics. Sci. China Life Sci 66 (7), 1518–1534. doi: 10.1007/s11427-022-2246-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Yin J., Xu K., Li T., Yin Y. (2019). What is the impact of diet on nutritional diarrhea associated with gut microbiota in weaning piglets: A system review. BioMed. Res. Int. 2019, 6916189. doi: 10.1155/2019/6916189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresse R., Chaucheyras-Durand F., Fleury M. A., van de Wiele T., Forano E., Blanquet-Diot S. (2017). Gut microbiota dysbiosis in postweaning piglets: understanding the keys to health. Trends Microbiol. 25, 851–873. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevarra R. B., Lee J. H., Lee S. H., Seok M.-J., Kim D. W., Kang B. N., et al. (2019). Piglet gut microbial shifts early in life: causes and effects. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 10 (1), 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40104-018-0308-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson J. K., Johansson M. E. (2022). The role of goblet cells and mucus in intestinal homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19, 785–803. doi: 10.1038/s41575-022-00675-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S., Zheng H., Han F., Zhang X., Zhang G., Ma S., et al. (2022). Lactobacillus johnsonii 6084 alleviated sepsis-induced organ injury by modulating gut microbiota. Food Sci. Nutr. 10, 3931–3941. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.2989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuß E. M., Pröll-Cornelissen M. J., Neuhoff C., Tholen E., Große-Brinkhaus C. (2019). Invited review: Piglet survival: benefits of the immunocompetence. Animal 13, 2114–2124. doi: 10.1017/S1751731119000430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Ma L., Nie Y., Chen J., Zheng W., Wang X., et al. (2018). A microbiota-derived bacteriocin targets the host to confer diarrhea resistance in early-weaned piglets. Cell Host Microbe 24, 817–832.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Li Z.-X., Wu Y., Huang Z.-Y., Hu Y., Gao J. (2021). Treatment and bioresources utilization of traditional Chinese medicinal herb residues: Recent technological advances and industrial prospect. J. Environ. Manage 299, 113607. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K., Zhang P., Zhang Z., Youn J. Y., Wang C., Zhang H., et al. (2021). Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in the treatment of COVID-19 and other viral infections: Efficacies and mechanisms. Pharmacol. Ther. 225, 107843. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman B., Nyachoti C. M. (2017). Husbandry practices and gut health outcomes in weaned piglets: A review. Anim. Nutr. 3, 205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X., Su M., Liang Y., Li Y. (2022). Effects of chlorogenic acid on growth, metabolism, antioxidation, immunity, and intestinal flora of crucian carp (Carassius auratus). Front. Microbiol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1084500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C.-K., Yu J., Le D., Han S., Yu S., Lee M. (2023). Anti-inflammatory activity of caffeic acid derivatives from Ilex rotunda. Int. Immunopharmacol. 115, 109610. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köksal E., Tohma H., Kılıç Ö, Alan Y., Aras A., Gülçin İ, et al. (2017). Assessment of antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of nepeta trachonitica: analysis of its phenolic compounds using HPLC-MS/MS. Sci. Pharm. 85 (2), 24. doi: 10.3390/scipharm85020024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuralkar P., Kuralkar S. V. (2021). Role of herbal products in animal production - An updated review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 278, 114246. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Chen L., Zhao Y., Sun H., Zhao L. (2022). Research on the mechanism of HRP relieving IPEC-J2 cells immunological stress based on transcriptome sequencing analysis. Front. Nutr. 9. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.944390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Xia S., Jiang X., Feng C., Gong S., Ma J., et al. (2021). Gut microbiota and diarrhea: an updated review. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.625210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Chen P., Lv X., Zhou Y., Li X., Ma S., et al. (2022). Effects of chlorogenic acid on performance, anticoccidial indicators, immunity, antioxidant status, and intestinal barrier function in coccidia-infected broilers. Anim. (Basel) 12 (8), 963. doi: 10.3390/ani12080963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Yang R., Ma F., Jiang W., Han C. (2023). Recycling utilization of Chinese medicine herbal residues resources: systematic evaluation on industrializable treatment modes. Environ. Sci. pollut. Res. Int. 30, 32153–32167. doi: 10.1007/s11356-023-25614-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G., Chai X., Hou G., Zhao F., Meng Q. (2022). Phytochemistry, bioactivities and future prospects of mulberry leaves: A review. Food Chem. 372, 131335. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makki K., Deehan E. C., Walter J., Bäckhed F. (2018). The impact of dietary fiber on gut microbiota in host health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 23, 705–715. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveed M., Hejazi V., Abbas M., Kamboh A. A., Khan G. J., Shumzaid M., et al. (2018). Chlorogenic acid (CGA): A pharmacological review and call for further research. BioMed. Pharmacother. 97, 67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.10.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura R., Takeda K. (2017). Roles of intestinal epithelial cells in the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Exp. Mol. Med. 49, e338. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perše M., Večerić-Haler Ž. (2019). The role of igA in the pathogenesis of igA nephropathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (24), 6199. doi: 10.3390/ijms20246199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y., Wang S., Huang W., Li K., Wu M., Liu W., et al. (2023). Chlorogenic acid improves intestinal morphology by enhancing intestinal stem-cell activity. J. Sci. Food Agric. 103, 3287–3294. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.12469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez B. C., Hayes M. D., Condotta I. C., Leonard S. M. (2022). Impact of housing environment and management on pre-/post-weaning piglet productivity. J. Anim. Sci. 100 (6), skac142. doi: 10.1093/jas/skac142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seikrit C., Pabst O. (2021). The immune landscape of IgA induction in the gut. Semin. Immunopathol. 43, 627–637. doi: 10.1007/s00281-021-00879-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y., Sun Y., Li D., Chen Y. (2020). Chrysanthemum indicum L.: A Comprehensive Review of its Botany, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology. Am. J. Chin. Med. 48, 871–897. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X20500421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y.-C., Zhao Y.-R., Zhang A.-Z., Zhao L., Yu Z., Li M.-Y. (2022). Hexavalent chromium-induced toxic effects on the hematology, redox state, and apoptosis in Cyprinus carpio. Regional Stud. Mar. Sci. 56, 102676. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2022.102676 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Sun Z., Wang D., Liu F., Wang D. (2022). Contribution of ultrasound in combination with chlorogenic acid against Salmonella enteritidis under biofilm and planktonic condition. Microb. Pathog. 165, 105489. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre M., Di Carlo S. E., Peduto L. (2023). Stromal regulation of the intestinal barrier. Mucosal Immunol. 16, 221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.mucimm.2023.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X., Xiong K., Fang R., Li M. (2022). Weaning stress and intestinal health of piglets: A review. Front. Immunol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1042778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira C. G., Fusieger A., Milião G. L., Martins E., Drider D., Nero L. A., et al. (2021). Weissella: an emerging bacterium with promising health benefits. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 13, 915–925. doi: 10.1007/s12602-021-09751-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiplakou E., Pitino R., Manuelian C. L., Simoni M., Mitsiopoulou C., de Marchi M., et al. (2021). Plant feed additives as natural alternatives to the use of synthetic antioxidant vitamins in livestock animal products yield, quality, and oxidative status: A review. Antioxidants (Basel) 10 (5), 780. doi: 10.3390/antiox10050780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker B. S., Craig J. R., Morrison R. S., Smits R. J., Kirkwood R. N. (2021). Piglet viability: A review of identification and pre-weaning management strategies. Anim. (Basel) 11 (10), 2902. doi: 10.3390/ani11102902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Dempsey E., Corr S. C., Kukula-Koch W., Sasse A., Sheridan H. (2022). The Traditional Chinese Medicine Houttuynia cordata Thunb decoction alters intestinal barrier function via an EGFR dependent MAPK (ERK1/2) signalling pathway. Phytomedicine 105, 154353. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Xu K., Cai X., Wang C., Cao Y., Xiao J. (2023). Rosmarinic acid restores colonic mucus secretion in colitis mice by regulating gut microbiota-derived metabolites and the activation of inflammasomes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 4571–4585. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c08444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Zhou M., Gong X., Zhou Y., Chen J., Ma J., et al. (2022). Starch-protein interaction effects on lipid metabolism and gut microbes in host. Front. Nutr. 9. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1018026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Luo H., Zhong Z., Ai Y., Zhao Y., Liang Q., et al. (2022). Phytochemistry, pharmacology and quality control of xiasangju: A traditional Chinese medicine formula. Front. Pharmacol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.930813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia B.-H., Hu Y.-Z., Xiong S.-H., Tang J., Yan Q.-Z., Lin L.-M. (2017). Application of random forest algorithm in fingerprint of Chinese medicine: different brands of Xiasangju granules as example. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 42, 1324–1330. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20170121.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia B.-H., Yan D., Cao Y., Zhou Y.-M., Li Y.-M., Xie J.-C., et al. (2016). Analysis of different dosage forms of Xiasangju granules on fingerprints and models using high performance liquid chromatography. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 41, 416–420. doi: 10.4268/cjcmm20160309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J., Li Y., Han H., Chen S., Gao J., Liu G., et al. (2018). Melatonin reprogramming of gut microbiota improves lipid dysmetabolism in high-fat diet-fed mice. J. Pineal Res. 65, e12524. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Zhao Y.-Y., Zhang Y., Zhao L., Ma Y.-F., Li M.-Y. (2021). Bioflocs attenuate Mn-induced bioaccumulation, immunotoxic and oxidative stress via inhibiting GR-NF-κB signalling pathway in Channa asiatica. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 247, 109060. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2021.109060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Zhao L., Zhao J.-L., Xu W., Guo Z., Zhang A.-Z., et al. (2022). Dietary Taraxacum mongolicum polysaccharide ameliorates the growth, immune response, and antioxidant status in association with NF-κB, Nrf2 and TOR in Jian carp (Cyprinus carpio var. Jian). Aquaculture 547, 737522. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsev S. Y., Belous A. A., Voronina O. A., Rykov R. A., Bogolyubova N. V. (2021). Correlations between antioxidant and biochemical parameters of blood serum of duroc breed pigs. Anim. (Basel) 11 (8), 2400. doi: 10.3390/ani11082400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Cui X., Zhang M., Bai B., Yang Y., Fan S. (2022). The antibacterial mechanism of perilla rosmarinic acid. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 69, 1757–1764. doi: 10.1002/bab.2248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wang Y., Chen D., Yu B., Zheng P., Mao X., et al. (2018). Dietary chlorogenic acid supplementation affects gut morphology, antioxidant capacity and intestinal selected bacterial populations in weaned piglets. Food Funct. 9, 4968–4978. doi: 10.1039/c8fo01126e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Li M., Sun H. (2019). Effects of dietary calcium to available phosphorus ratios on bone metabolism and osteoclast activity of the OPG /RANK/RANKL signalling pathway in piglets. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl) 103, 1224–1232. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Yuan B.-D., Zhao J.-L., Jiang N., Zhang A.-Z., Wang G.-Q., et al. (2020). Amelioration of hexavalent chromium-induced bioaccumulation, oxidative stress, tight junction proteins and immune-related signaling factors by Allium mongolicum Regel flavonoids in Ctenopharyngodon idella. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 106, 993–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Zhao J.-L., Bai Z., Du J., Shi Y., Wang Y., et al. (2022). Polysaccharide from dandelion enriched nutritional composition, antioxidant capacity, and inhibited bioaccumulation and inflammation in Channa asiatica under hexavalent chromium exposure. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 201, 557–568. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.12.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielińska D., Zieliński H., Laparra-Llopis J. M., Szawara-Nowak D., Honke J., Giménez-Bastida J. A. (2021). Caffeic acid modulates processes associated with intestinal inflammation. Nutrients 13 (2), 544. doi: 10.3390/nu13020554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: NCBI, PRJNA1011898.