Abstract

Rationale

CC16 (Club Cell Secretory Protein) is a protein produced by club cells and other non-ciliated epithelial cells within the lungs. CC16 has been shown to protect against the development of obstructive lung diseases and attenuate pulmonary pathogen burden. Despite recent advances in understanding CC16 effects in circulation, the biological mechanisms of CC16 in pulmonary epithelial responses have not been elucidated.

Objectives

We sought to determine if CC16 deficiency impairs epithelial-driven host responses and identify novel receptors expressed within the pulmonary epithelium through which CC16 imparts activity.

Methods

We utilized mass spectrometry and quantitative proteomics to investigate how CC16 deficiency impacts apically secreted pulmonary epithelial proteins. Mouse tracheal epithelial cells (MTECS), human nasal epithelial cells (HNECs) and mice were studied in naïve conditions and after Mp challenge.

Measurements and main results

We identified 8 antimicrobial proteins significantly decreased by CC16-/- MTECS, 6 of which were validated by mRNA expression in Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) cohorts. Short Palate Lung and Nasal Epithelial Clone 1 (SPLUNC1) was the most differentially expressed protein (66-fold) and was the focus of this study. Using a combination of MTECs and HNECs, we found that CC16 enhances pulmonary epithelial-driven SPLUNC1 expression via signaling through the receptor complex Very Late Antigen-2 (VLA-2) and that rCC16 given to mice enhances pulmonary SPLUNC1 production and decreases Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Mp) burden. Likewise, rSPLUNC1 results in decreased Mp burden in mice lacking CC16 mice. The VLA-2 integrin binding site within rCC16 is necessary for induction of SPLUNC1 and the reduction in Mp burden.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate a novel role for CC16 in epithelial-driven host defense by up-regulating antimicrobials and define a novel epithelial receptor for CC16, VLA-2, through which signaling is necessary for enhanced SPLUNC1 production.

Keywords: CC16, mycoplasma pneumoniae, SPLUNC1, airway epithelia, mass spectrometry

Introduction

Club cell secretory protein (CC16; also known as CC10, CCSP, and uteroglobin) is a homodimeric pneumoprotein encoded by the SCGB1A1 gene and produced by club cells and non-ciliated epithelial cells in the distal pulmonary epithelium (1). Despite its origin in the lungs, CC16 is also detectable in the serum, making it a potential biomarker for lung epithelial integrity and lung function (1–3). Although the complete biological functions of CC16 have not been elucidated, studies have shown that this protein has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, which may protect against the development of obstructive lung disease (4–6). Additionally, our group has previously shown that CC16 deficiency leads to dramatically altered pulmonary function and enhanced airway remodeling (7) and that, by binding to the integrin Very Late Antigen-4 (VLA-4) on leukocytes, CC16 can reduce leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells, lung infiltration, and airway inflammation (8).

We have also previously shown that during infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Mp), CC16 deficient (CC16-/-) mice had significantly higher Mp burden compared to WT mice. This increased Mp burden appeared to be driven by an epithelial impairment since mouse tracheal epithelial cells (MTECs) deficient in CC16 also had significantly higher Mp colonization, compared to wildtype (WT) cells (8, 9). These findings supported the possibility that increased Mp burden observed in the CC16-/- mice and MTECs may be due to decreased pulmonary epithelial-driven antimicrobial responses (9). A better understanding of how CC16 mediates epithelial-driven antimicrobial responses and how this regulation aids in the resolution of pulmonary infections is of paramount importance given that several patient populations have been described as having low CC16 levels, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cystic fibrosis patients (10–14). Therefore, in this study, we used mass spectrometry and quantitative proteomics and identified 8 apically secreted antimicrobial proteins that are significantly downregulated within the pulmonary epithelium when CC16 is absent. We found that of those 8 identified from MTECS, 6 were validated as significantly associated with CC16 mRNA expression in epithelial cells from asthma patients from 2 SARP cohorts (cross sectional and longitudinal) (15). These proteins include BPIFA1 (encodes Short Palate Lung and Nasal Epithelial Clone 1; SPLUNC1), TF (encodes Transferrin), LTF (encodes Lactotransferrin), SCGB3A2 (encodes Secretoglobin 3A2), SFTPD (encodes Surfactant Protein-D), and LYZ (encodes Lyzosyme).

SPLUNC1 was the most differentially expressed antimicrobial protein, with very high expression from WT MTECs and very low to non-detectable expression from CC16-/- MTECs and became the focus of our mechanistic studies. Since SPLUNC1 was the most differentially expressed protein from MTECs dependent on CC16 expression, along with the known roles of SPLUNC1 in respiratory host defense (16–21), we set up a series to additional experiments to understand if and how CC16 regulates the expression of SPLUNC1 using WT and CC16-/- MTECs and mice, as well as human nasal epithelial cells (HNECs) and clinical data from the SARP cohorts.

Methods

Experimental mice

All experiments were handled in accordance with University of Arizona on IACUC approved animal protocols. WT and CC16-/- male mice on a C57BL/6J background were obtained at ~6-8 weeks of age at the time of rCC16 treatment, or males and females >12 weeks of age for MTECs as more cells are recovered for growth on Transwells from aged mice. All mice were born and raised in the same room in the University of Arizona Health Sciences animal facility and were tested to be specific-pathogen free according to standard protocols using sentinel mice from the same room.

Mouse tracheal epithelial cell isolation

MTECs were isolated as previously described (9). Detailed MTEC isolation methods can be found in the supplement.

MTEC culture media, supplements, and in vitro culturing

To reduce biological variation by decreasing the number of mice used for MTECs, we followed a recent culturing protocol published by Eenjes et al. (22). Detailed MTEC culturing methods can be found in the supplement.

NCI-H292 cell culturing

NCI-H292 cells (human pulmonary mucoepidermoid carcinoma cells) (ATCC; Manassas, VA) were cultured in T75 flasks using ATCC-formulated RPMI-1640 medium (ATCC 30-2001) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cell culture medium was replaced every 48 hrs. Once 90% confluency was reached, the cells were removed from by flask by incubation (37°C, 5% CO2) with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA for 10 min. Cells were passaged (1:8 dilution) into fresh RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS.

Human nasal epithelial cell isolation and culturing

Human nasal epithelial cell (HNEC) brushings were obtained from healthy donors under University of Arizona IRB-approved protocols (PI: Ledford). After collection, HNECs were submerged in sputolysin (MilliporeSigma; Burlington, MA) diluted in RPMI supplemented with an antibiotic/antimycotic (Gibco; Waltham, MA) for 30 min (37°C, 5% CO2) followed by centrifugation (350 RCF, 5 min, 4°C). The HNECs were washed three times using 10% FBS/RPMI followed by centrifugation (350 RCF, 5 min, 4°C). HNECs were seeded in collagen coated T25 flasks at a density of 5x105 cells per 25 cm2 using PneumaCult Ex-Plus media (StemCell Technologies; Vancouver, CA). HNECs were removed from the T25 flasks by incubation (37°C, 5% CO2) with ACF enzymatic dissociation solution for 7-8 min, followed by addition of ACF enzyme inhibition solution to stop the reaction. Cells were then plated onto Costar Transwell membranes (12 mm, 0.4 μm membrane pores) at a density of 89,600 cells per membrane. After the initial seeding period, PneumaCult Basal ALI media (StemCell Technologies; Vancouver, VA) supplemented with PneumaCult Basal Media (StemCell Technologies; Vancouver, CA) was replaced every other day. When the cells reached 80% confluency (~5 days), the culture medium was replaced daily, only on the basolateral side, to establish an ALI. After the first day in an ALI, the medium was replaced every 48 hrs. Once full confluency was obtained, the cells were maintained at an ALI for 14 days.

rCC16 treatment for mice

WT and CC16-/- mice were treated with rCC16 (16.7 μg/mouse) intravenously for 3 days as described previously (8). rCC16 was made by Dr. Michael Johnson as previously described (8) and diluted in sterile, USP-grade 0.9% NaCl prior to administration.

rCC16 and D67A treatment for MTECs

WT and CC16-/- MTECs were treated with WT rCC16 (25 μg/mL) for 12-, 24-, and 48-hrs, and D67A rCC16 (25 μg/mL) for 24 hrs (8). WT and D67A rCC16, diluted in MTEC differentiation media, was added to the apical and basolateral chambers of the MTEC cultures.

Mp infection for WT MTECs

Mp infection in MTECs was performed as previously described (9). In short, after the apical surface of the WT MTECs was washed with sterile 1x PBS, Mp (1x106 Mp/200 μL inoculum) was added to the apical side of the MTECs and incubated for 24 hrs (37°C, 5% CO2).

In-solution tryptic digestion

In-solution tryptic digestion of the apically secreted proteins from WT and CC16-/- MTECs was performed as described (23). Detailed tryptic digestion methods can be found in the Supplement.

Mass spectrometry and data search

HPLC-ESI-MS/MS was performed as previously described (24) in positive ion mode on a Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Fusion Lumos tribrid mass spectrometer fitted with an EASY-Spray Source (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA). Detailed mass spectrometry and data search methods can be found in the supplement.

Label-free quantitative proteomics

Progenesis QI for proteomics software (version 2.4, Nonlinear Dynamics Ltd., Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) was used to perform ion-intensity based label-free quantification as previously described (25). Detailed proteomics methods can be found in the supplement.

SYBR green real-time PCR for measurement of gene expression in mice, MTECs, and HNECs

Gene expression for all experiments was performed as previously described (9). Detailed RT-PCR methods can be found in the supplement.

Measuring BPIFA1 in mice and MTECs, and HNECs

BPIFA1 (forward: 5’-GTCCACCCTTGCCACTGAACCA-3’; reverse: 5’-CACCGCTGAGAGCATCTGTGAA-3’) was examined in lung tissue from CC16-/- mice treated with saline (control) or rCC16, as well as WT and CC16-/- MTECs treated with media (control), rCC16 (25 μg/mL), or VLA-2 inhibitor BTT 3033 IC50 = 130 nM) (R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN) by RT-PCR using a Sybr-green compatible system. GAPDH (forward: 5’-CCTGCACCACCAACTGCTTA-3’; reverse: 5’-GTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGAT-3’) was used as a housekeeping control for these sets of experiments.

Measuring Mp burden in WT MTECs

Measuring Mp burden by RT-PCR was performed as previously described (9). In short, the MP-SPECIFIC P1 ADHESIN gene was used to assess Mp burden in infected WT MTECs (forward: 5′-CGCCGCAAAGAT GAATGAC-3′; reverse: 5′-TGTCCTTCCCCATCTAACAGTTC-3′) using a Sybr-green compatible system. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping control for these sets of experiments. Non-infected MTECs were used as negative controls.

Determination of SPLUNC1 and integrin protein levels by western blotting

To determine SPLUNC1 protein levels in the lungs, right lung tissue from each sample was homogenized with 400 μL of RIPA (radioimmunoprecipitation assay) buffer (Teknova; Hollister, CA) with protease inhibitors (Roche; Basel, Switzerland). After homogenization, the lungs were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected. Protein concentrations from lung lysates and apical secretions were quantified using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA). Equal amounts of lysate and apical secretion were loaded onto Mini-Protean TGX precast gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories; Hercules, CA). To determine SPLUNC1 protein levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from mice, equal volumes of BALF were loaded into Mini-Protean TGX precast gels, respectively. To determine integrin protein levels in MTECs, a standard concentration (10 μg/mL) was loaded into each well of a Mini-Protean TGX precast gel. Antibodies for SPLUNC1 (Proteintech; Rosemont, IL), ITGA2 (Cell Signaling; Danvers, MA), ITGA4 (Cell Signaling; Danvers, MA), ITGB1 (Cell Signaling; Danvers, MA), and GAPDH (Cell Signaling; Danvers, MA) were used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. All primary antibodies were diluted 1:1000 in 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk-1X TBST and required an anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Cell Signaling; Danvers, MA). The secondary antibody was diluted 1:2000 in 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk-1X TBST. A ChemiDoc imaging system and Image Lab software (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA) were used to image and quantify the densitometry of each western blot.

Human tracheal epithelium single-cell RNA sequencing data analysis

Single-cell RNA sequencing data of epithelial cells isolated from six healthy adult tracheal donors described in Goldfarbmuren et al. were used to assess the expression level and cell-type specificity of genes of interest (26). Detailed methods on this analysis can be found in the supplement.

Flow cytometry on WT and CC16-/- mouse lungs and MTECs

Detailed flow cytometry methods can be found in the supplement.

VLA-2 inhibition in WT MTECs and healthy HNECs

Differentiated WT MTECs and healthy HNECs were pre-treated apically with BTT 3033 at its respective IC50 concentration for 30 minutes (37°C; 5% CO2). After pre-treatment with the BTT3033, media or rCC16 (25 μg/mL) was apically added to their respective cells. Treated MTECs and HNECs were incubated for 24 hrs (37°C; 5% CO2).

rSPLUNC1 Treatment for CC16-/- mice

CC16-/- mice were infected with Mp intranasally (1x108 Mp/mL; 50 μL/mouse) for 2 hrs, followed by oropharyngeal treatment with rSPLUNC1 (50 μg/mL; 40 μL/mouse) (R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN). Mice were given a rSPLUNC1 (10 μg/mL; 40 μL/mouse) 24 hrs after the initial treatment. rSPLUNC1 was diluted in USP-grade 0.9% NaCl prior to administration.

In-silico prediction of CC16 binding with integrin α2 subunit

Using the PRISM® software that predicts protein-protein interactions at a structural level (27), we assessed the protein-protein interaction between rat-CC16, integrin subunit α2, and the cytoplasmic tail of β1, using available protein 3D structure models in the Protein Data Bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org). Please note that there is no available human CC16 structure available in the PDB to conduct the in-silico test. The protein interactions are measured by the Fiberdock energy scoring (28, 29), which measures the negative energy required for such interactions. The negative scores obtained reflect the spontaneity of the binding. The higher the negative number the more spontaneous the protein-protein binding.

Protein affinity calculations using ISLAND

To determine binding affinity between CC16 and VLA-2, a sequence-based protein binding affinity predictor called ISLAND was used (30). The human protein sequences for CC16 and the α2 subunit were inputted and predicted binding and protein affinities were obtained using the ΔΔG and Kd values.

Severe asthma research program participants

SARP is a currently active NHLBI-sponsored multicenter program involving non-smokers with mild to severe asthma and a subset of healthy controls. Participants in SARP were comprehensively phenotyped using standard protocols as described previously (31, 32). Bronchoscopy was performed on a subset of participants in the SARP longitudinal cohort (n = 156) and cross-sectional cohort (n = 155) to obtain epithelial cells from brush biopsies for RNAseq and microarray mRNA chip analysis, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The RNAseq and microarray expression data have been deposited and can be accessed through dbGaP (phs001446) and GEO (GSE63142 and GSE43696), respectively (15, 33). SARP was approved by the appropriate institutional review board including informed consent.

Meta-analysis of genes correlated with CC16 mRNA expression levels

Correlation analyses of CC16 mRNA expression levels in human bronchial epithelial cells with other candidate genes (BPIFA1, BPIFB1, TF, LTF, SCGB3A2, SFTPB, SFTPD, LYZ, ITGA2, and ITGB1) in the SARP cross-sectional and longitudinal cohorts were performed using Spearman correlation as described previously (15, 33). Meta-analysis of Spearman correlation coefficient (rho) was performed in the SARP cohorts (n = 311) using metacor R package based on the Olkin-Pratt fixed-effect meta-analytical model (34) as described previously (15).

Statistical analysis

For all mouse and MTEC experiments, statistics were analyzed using Prism 8 (GraphPad). For all analysis of mouse and MTEC experiments, significance was determined by either Unpaired t test or One-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons, as appropriate.

Results

CC16 deficiency results in decreased apical antimicrobial expression by pulmonary epithelial cells

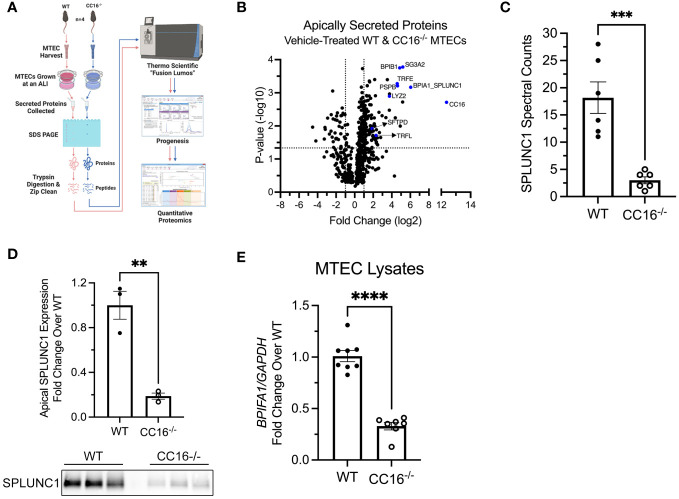

Apically secreted proteins from vehicle/control (media) treated WT and CC16-/- MTECs were identified and characterized using mass spectrometry and quantitative proteomics, respectively (Figure 1A). CC16 and SPLUNC1 (boxed in the volcano plot) were the most differentially expressed proteins detected by mass spectrometry from the WT MTECs in comparison to the CC16-/- MTECs (Figure 1B). More specifically, CC16 and SPLUNC1 secretion by the WT MTECs was approximately 5000 and 66 times greater, respectively, compared to CC16-/- MTECs (Table 1). In total, we found 8 antimicrobial associated proteins that were significantly higher in apical secretions from WT MTECs that are CC16 sufficient (colored blue and labeled in the volcano plot) compared to MTECs deficient in CC16.

Figure 1.

Apical expression of SPLUNC1 is decreased in CC16-/- MTECs. (A) Schematic of the experimental design for the mass spectrometry and quantitative proteomics approach to identify apically secreted proteins by WT and CC16-/- MTECs. (B) Volcano plot illustrating the apically secreted proteins identified. Above the horizontal black line represents the cut-off for a p value of <0.05, while the two vertical lines represent the cut-off values of 2-fold change in either the positive or negative direction. Selected antimicrobial proteins are highlighted in red and labeled. (C) Spectral counts of SPLUNC1 protein secreted by WT and CC16-/- MTECs by LC-MS/MS. ***P<0.001 Unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from six independent experiments. (D) SPLUNC1 apical protein expression was confirmed for control-treated WT and CC16-/- MTECs by western blotting. The same volume of protein (20μl) was loaded for each sample. **P<0.01 Unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean±SEM. (E) WT (n=8) and CC16-/- (n=7) MTECs were treated with media (control) for 48 hours, after which BPIFA1 expression was measured by RT-PCR with GAPDH as a housekeeping control. ****P<0.0001 Unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean±SEM.

Table 1.

Select apically secreted antimicrobial proteins whose expression is decreased in CC16-/- MTECs.

| Protein Abbreviation | Protein Name | Average Fold Change Relative to CC16-/- MTECs | Average P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CC16 | Club Cell Secretory Protein | 5267.1555 | 0.001940074 |

| BPIA1_SPLUNC1 | BPI Fold-Containing Family A Member 1; Short-Palate Lung and Nasal Epithelial Clone 1 | 66.1294 | 0.000679336 |

| SCGB3A2 | Secretoglobin Family 3A Member 2 | 36.5174 | 0.00016662 |

| BPIB1 | BPI Fold-Containing Family B Member 1 | 28.8412 | 0.000177805 |

| PSPB | Pulmonary Surfactant Protein B | 24.4547 | 0.000615467 |

| TRFE | Transferrin | 23.9729 | 0.00053206 |

| LYZ2 | Lysozyme C-2 | 13.4078 | 0.001273525 |

| TRFL | Lactotransferrin | 4.9948 | 0.019350103 |

| SFTPD | Pulmonary Surfactant Protein D | 3.6991 | 0.011988244 |

SPLUNC1 spectral counts, which is a measurement of protein abundance, were significantly higher in the apical secretions from WT MTECs, compared to CC16-/- MTECs (Figure 1C). Protein levels were confirmed by western blotting of SPLUNC1 in the apical secretions taken from the ALI cultures (Figure 1D). Additionally, BPIFA1 gene expression by RT-PCR was higher in WT MTECs, compared to CC16-/- MTECs (Figure 1E), suggesting that CC16 may regulate BPIFA1 expression at the gene level.

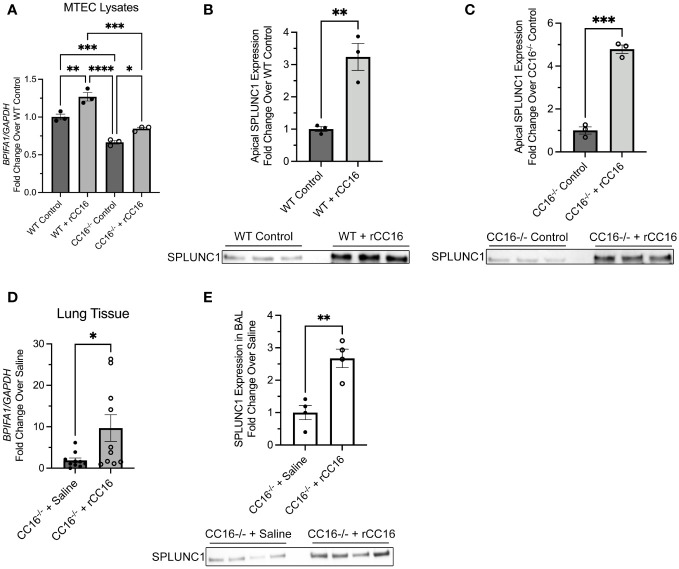

Recombinant CC16 increases SPLUNC1 expression in WT and CC16-/- MTECs and mice

We next sought to determine if exogenous rCC16 could augment SPLUNC1 expression at the gene and protein level. For this, WT and CC16-/- MTECs were incubated with media (control) or recombinant CC16 (rCC16) for 12-, 24-, and 48-hrs to determine which time point resulted in the most significant upregulation of SPLUNC1 expression. The 24-hr time point resulted in the highest BPIFA1 gene expression by RT-PCR in both WT and CC16-/- MTECs and was therefore chosen as the time point for assessment moving forward (Figure 2A). Apical expression of SPLUNC1 protein levels in WT (Figure 2B) and CC16-/- (Figure 2C) MTECs by western blotting confirmed that rCC16 treatment significantly increases SPLUNC1 expression. However, we did not observe significantly increased SPLUNC1 expression between WT and CC16-/- MTEC lysates (Supplementary Figure 1A).

Figure 2.

rCC16 treatment increases SPLUNC1 expression in vitro and in vivo. (A) WT (n=3) and CC16-/- (n=3) MTECs were treated with media (control) or rCC16 (25μg/ml) for 24 hours, after which BPIFA1 expression in cell lysates was measured by RT-PCR with GAPDH as a housekeeping control. *P<0.05, * *P<0.01, * **P<0.001, * ***P<0.0001 by One-Way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test. SPLUNC1 apical protein expression was confirmed for control- and rCC16-treated WT (B) and CC16-/- (C) MTECs by western blotting (n=3 per group). The same volume of protein (20μl) was loaded for each sample. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 by Unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean±SEM. (D) CC16-/- mice were treated intravenously with saline (n=10) and rCC16 (n=10) for 3 days, after which BPIFA1 expression in lung tissue was measured by RT-PCR with GAPDH as a housekeeping control. *P<0.05 by Unpaired t test. (E) SPLUNC1 protein expression was measured in the BALF from the 3-day saline (n=4) and rCC16 (n=4) treated CC16-/- mice. The same volume of protein (20μl) was loaded for each sample. **P<0.01 by Unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean±SEM.

Additional studies were carried out in CC16-/- mice treated intravenously with saline or rCC16 for 3 days, followed by assessment of BPIFA1 gene expression in lung tissue and SPLUNC1 protein levels in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). rCC16 treatment resulted in significantly increased BPIFA1 gene expression in the lung tissue of CC16-/- mice, compared to saline-treated CC16-/- mice (Figure 2D). SPLUNC1 protein levels, assessed by western blotting of BALF, showed that CC16-/- mice treated with rCC16 had significantly higher SPLUNC1 levels in the luminal lining fluid of their lungs, but not in their lung tissue (Supplementary Figure 1B), compared to saline treated mice (Figure 2E).

SCGB1A1 and antimicrobial gene expression significantly and positively associated in human cohorts

We next chose to examine if SCGB1A1 and BPIFA1 associate in human samples using the well-established SARP cohorts. Correlation analysis between SCGB1A1 and BPIFA1 mRNA expression was performed using data from two human cohorts – the cross-sectional cohort (SARP1-2) and the longitudinal cohort (SARP3). Data included mRNA expression from asthma and non-asthma participants. The cross-sectional (n=155; p=0.017) data and the longitudinal (n=156; p=0.021) data showed significant correlation between SCGB1A1 and BPIFA1 bronchial gene expression with meta-analysis significance of p=2.9x10-4 (rho=0.19) (Table 2). Next, the same set of 8 identified proteins from apical secretions of MTECS (Table 1) were assessed for corresponding gene expression in the human SARP cohort data. Of the 8 genes assessed by meta-analysis, 6 were found to be positively and significantly correlated with CC16 expression, including: BPIFA1, TF, LTF, SCGB3A2, SFTPD, and LYZ. This human data provides additional support and is in line with the findings from MTECS that respiratory epithelial expression of CC16 is associated with gene expression of several key antimicrobial genes.

Table 2.

Correlation of mRNA expression levels of eight antimicrobial genes with CC16 in bronchial epithelial cells in SARP.

| Mouse Protein | Human Gene | Cross-Sectional Cohort (n = 155) |

Longitudinal Cohort (n = 156) |

Meta-Analysis* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rho | P value | rho | P value | rho | P value | ||

| CC16 | SCGB1A1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| BPIA1_SPLUNC1 | BPIFA1 | 0.19 | 0.017 | 0.19 | 0.021 | 0.19 | 2.9x10-4 |

| BPIB1 | BPIFB1 | -0.071 | 0.38 | -0.14 | 0.073 | -0.11 | 0.027 |

| TRFE | TF | 0.028 | 0.73 | 0.24 | 0.003 | 0.13 | 0.009 |

| TRFL | LTF | 0.51 | 1.3x10-11 | 0.55 | <2.2x10-16 | 0.53 | 1.6x10-39 |

| SCGB3A2 | SCGB3A2 | 0.23 | 0.003 | 0.018 | 0.82 | 0.13 | 0.012 |

| PSPB | SFTPB | -0.027 | 0.74 | 0.022 | 0.78 | -0.002 | 0.48 |

| SFTPD | SFTPD | 0.19 | 0.019 | 0.034 | 0.67 | 0.11 | 0.024 |

| LYZ2 | LYZ | -0.062 | 0.44 | -0.17 | 0.034 | -0.12 | 0.019 |

*Meta-analysis of Spearman correlation coefficient (rho) was performed in the SARP cohorts (n=311) using metacor R package on the Olkin-Pratt fixed-effect meta-analytical model.

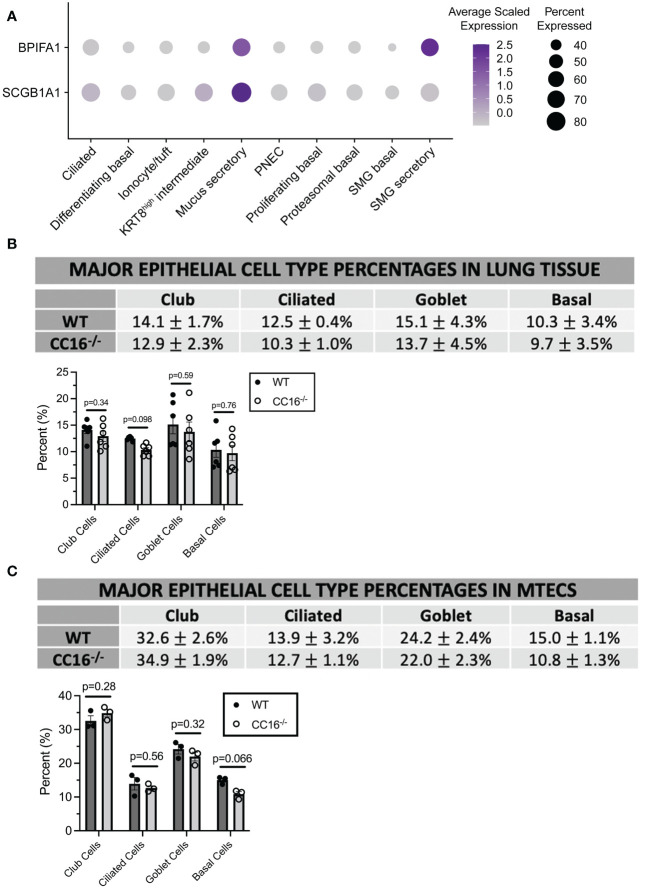

SPLUNC1 is highly expressed by mucus and submucosal gland secretory cells in the pulmonary epithelium

There has been some discrepancy between publications in identifying which respiratory cell types produce SPLUNC1 (17, 18, 35–37). To better understand the source of BPIFA1 expression, we utilized published single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from healthy adult tracheal epithelial cells described in Goldfarbmuren et al. (26) (Figure 3A). BPIFA1 and SCGB1A1 were expressed (expression greater than 0) in 47.4% and 68.6% of the total cells in the dataset, respectively. However, the cell type annotated as “mucus secretory” cells by the original authors, which includes the club cell population, exhibited significant upregulation of both BPIFA1 (average log fold-change = 4.58 relative to all other cells, adjusted p-value = 2.4x10-6) and SCGB1A1 (average log fold-change = 4.46, adjusted p-value = 7.7x10-6). “Submucosal gland secretory” cells also had significant upregulation of BPIFA1 (average log fold-change = 3.98, adjusted p-value = 3.5x10-5), while SCGB1A1 expression was not significantly upregulated in this population. Furthermore, considering individual mucus secretory cells, we found a subtle but significant positive relationship between BPIFA1 and SCGB1A1 expression (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.33, p-value = 9.7 x10-31) (Supplementary Figure 2). Taken together, these data suggest that mucus secretory cells are the primary source of BPIFA1 expression in the airways.

Figure 3.

CC16 deficiency does not affect epithelial cell differentiation. (A) Dot plot showing the average normalized expression of BPIFA1 and SCGB1A1 (rows) across cell types (columns) generated from single-cell RNA sequencing data of healthy adult tracheal epithelial cells described in Goldfarburen et al. (33). The color of the dot represents the average gene expression in the cell type and the diameter of the dot indicates the fraction of cells that express the gene within the cell type. (B, C) Major epithelial cell type expression was measured in WT (n=6) and CC16-/- (n=6) mice (B) and in WT (n=3) and CC16-/- (n=3) MTECS (C) using flow cytometry. Indirect FACs staining was used to identify club (CYP2F2), ciliated (TUBA1A), goblet (MUC5AC), and basal (KRT5) expression. No significant differences in epithelial cell expression were observed between WT and CC16-/- mice and MTECs by Unpaired t test. NS=not significant. Data are presented as mean±SEM.

CC16 deficiency does not affect major epithelial cell populations in mice and MTECs

To confirm that differences in major epithelial cell populations were not driving the differences in SPLUNC1 expression, flow cytometry was performed on WT and CC16-/- mice and on MTECs grown at an ALI for two weeks for major epithelial cell markers (club, ciliated, goblet, and basal cells). In WT and CC16-/- mouse lungs (Figure 3B, Supplementary Figure 3) and MTECs (Figure 3C, Supplementary Figure 4), there were no significant differences in the expression of these epithelial cell populations.

CC16 does not activate the SPLUNC1 promoter

To mechanistically understand how CC16 activates BPIFA1 expression, we used a luciferase reporter assay in which NCI-H292 cells were transfected with the BPIFA1 promoter, treated with rCC16 for 24 hrs, and quantified promoter activation by luminescence. To elucidate how CC16 regulates SPLUNC1 expression, we sought to determine if CC16 directly activates the SPLUNC1 promoter. Additionally, we aimed to determine if there are apically secreted protein(s) or intracellular protein(s) from WT and/or CC16-/- MTECs that activate the BPIFA1 promoter, and if this activation is dependent in CC16. Overall, transfection of the reporter constructs into the NCI-H292 cells was successful, as ACTB luminescence was significantly higher than the negative control and SPLUNC1 luminescence. However, rCC16 did not activate the BPIFA1 promoter directly (Supplementary Figure 5A). Additionally, there were no apically secreted proteins (Supplementary Figure 5B), nor intracellular proteins (Supplementary Figure 5C), from the WT and CC16-/- MTECs that significantly activated the BPIFA1 promoter. These results suggest CC16-mediated induction of SPLUNC1 expression is not direct through enhancing promoter activity, but instead likely involves intermediate signaling.

CC16 does not signal through TLR2 to activate SPLUNC1 expression in MTECs

Multiple papers have shown that TLR2 activation stimulates SPLUNC1 expression in airway epithelial cells (17, 38, 39); therefore, we sought to determine if CC16 signals through TLR2 to activate SPLUNC1 expression in WT MTECs. WT MTECs were incubated with a TLR2 blocking antibody (α-TLR2 antibody) or IgG1 isotype control antibody, followed by incubation with media (negative control), rCC16, or Pam3CSK4 (positive control). For the α-TLR2 antibody-treated MTECs, BPIFA1 gene expression was significantly increased during rCC16 treatment, compared to Pam3CSK4 treatment, indicating that CC16 does not signal through TLR2 to activate BPIFA1 expression (Supplementary Figure 6A). If CC16 were to signal through TLR2, BPIFA1 expression levels would be at similar levels as the Pam3CSK4-treated MTECs, since Pam3CSK4 activates TLR2, and this interaction would be disrupted due to α-TLR2 antibody incubation. Apical expression of SPLUNC1 further indicated that CC16 does not signal through TLR2 in WT MTECs (Supplementary Figure 6B).

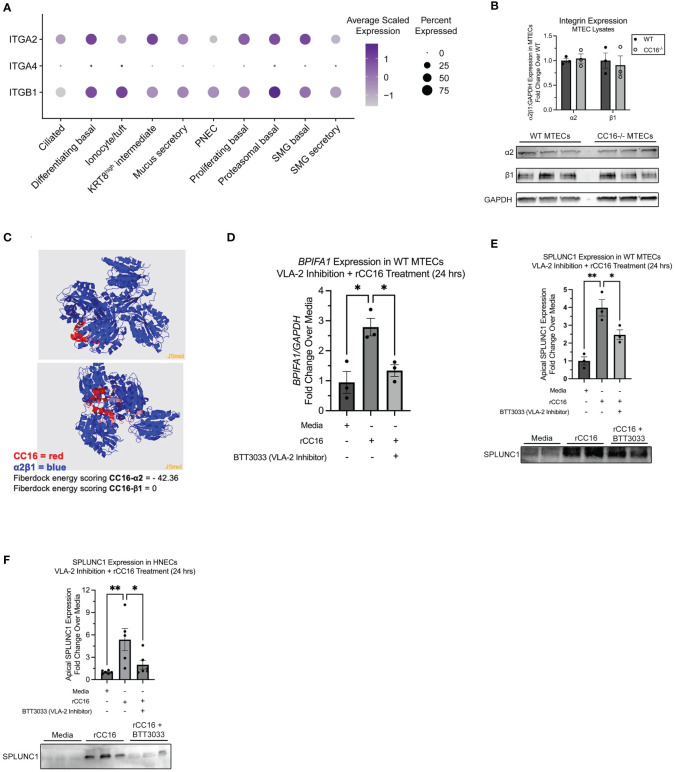

VLA-2 is necessary for rCC16-induced SPLUNC1

Our group has previously shown that CC16 binds to VLA-4 to prevent leukocyte extravasation into the lung (8). Using scRNA-seq data from healthy human tracheal epithelial cells, we confirmed that VLA-4 is expressed in the airways, albeit at very low levels. However, we found that VLA-2 (α2β1) is highly expressed across numerous airway cell types (Figure 4A). Based on this, we aimed to determine if CC16 could interact with VLA-2 to influence SPLUNC1 expression within the pulmonary epithelium. First, we confirmed that the integrins alpha-2 (α2) and beta-1 (β1) were expressed in both WT and CC16-/- MTECs at similar levels by western blotting and the doublet bands appeared as expected (Figure 4B). Next, a VLA-2 specific inhibitor, BTT3033, was added to WT MTECs in the presence of rCC16 for 24 hrs, followed by assessment of SPLUNC1 gene and apical protein expression by RT-PCR and western blotting, respectively. Compared to the positive control (rCC16), rCC16 was unable to upregulate SPLUNC1 when cells were co-treated with the BTT3033 inhibitor and had levels like the media only negative control (Figures 4D, E). For translatability, similar experiments were conducted in healthy primary HNECs, which produced similar results demonstrating that rCC16 could not upregulate SPLUNC1 when VLA-2 was inhibited (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of VLA-2 decreases SPLUNC1 expression in WT MTECs and healthy HNECs. (A) Dot plot of α2, β1, and α4 integrin subunit (gene names: ITGA2, ITGA4, and ITGB1, respectively) expression across healthy human adult tracheal epithelial cells from single-cell RNA sequencing data as described in Goldfarbmuren et al. (B) Expression of α2 and β1 integrin subunits was verified in WT MTECs (n=3) and CC16-/- MTECs (n=3) by western blotting. The same amount of protein (10 μg) was loaded for each sample. α2 and β1 protein levels are normalized to GAPDH. (C) Protein-protein interactions between CC16 and the integrin receptor components α2β1 using protein 3D structure modeling in the Protein Data Bank. The strength of interactions were measured by the Fiberdock energy scoring. The negative scores reflect the strength of binding. (D) WT MTECs (n=3) were treated with media, rCC16 (25 μg/mL), or rCC16 in combination with BTT3033 (VLA-2 inhibitor) (130 nM) for 24 hrs. Following the treatments, BPIFA1 gene expression was measured by RT-PCR with GAPDH as a housekeeping control. *P<0.05 by One-Way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (E) SPLUNC1 apical protein expression was assessed in the WT MTECs treated with media, rCC16, and rCC16 in combination with BTT3033 by western blotting (n=3/group). The same volume of protein (20μl) was loaded for each sample. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by One-Way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (F) SPLUNC1 apical protein expression was assessed by western blotting in healthy human nasal epithelial cells (HNECs) treated with media, rCC16 (25 μg/mL), or rCC16 in combination with BTT3033 (VLA-2 inhibitor) (130 nM) for 24 hrs (n=5-6 per group). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by One-Way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

From the SARP data, human bronchial epithelial cells mRNA expression levels of alpha 2 subunit of VLA-2 (gene name: ITGA2) were positively and significantly correlated with CC16, further supporting the potential role of VLA-2 in CC16-SPLUNC1 signaling pathway (Table 3). Along these lines, we assessed the protein-protein interaction between CC16 and the integrin receptor components α2β1. The strength of protein-protein interactions were measured by Fiberdock energy scoring. CC16 and α2 exhibit strong interaction, as indicated by a Fiberdock energy scoring of -42.36, whereas there were no predicted possible interactions with the intracytoplasmic tail β1 (Figure 4C).

Table 3.

Correlation of mRNA expression levels of ITGA2 and ITGB1 with CC16 in bronchial epithelial cells in SARP.

| Gene | Gene Annotation | Cross-Sectional Cohort (n = 155) |

Longitudinal Cohort (n = 156) |

Meta-Analysis* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rho | P value | rho | P value | rho | P value | ||

| ITGA2 | VLA-2 subunit alpha 2 | 0.15 | 0.068 | 0.32 | 4.0x10-5 | 0.24 | 5.2x10-6 |

| ITGB1 | VLA-2 subunit beta 1 | 0.0056 | 0.94 | 0.087 | 0.28 | 0.046 | 0.21 |

*Meta-analysis of Spearman correlation coefficient (rho) was performed in the SARP cohorts (n=311) using metacor R package on the Olkin-Pratt fixed-effect meta-analytical model.

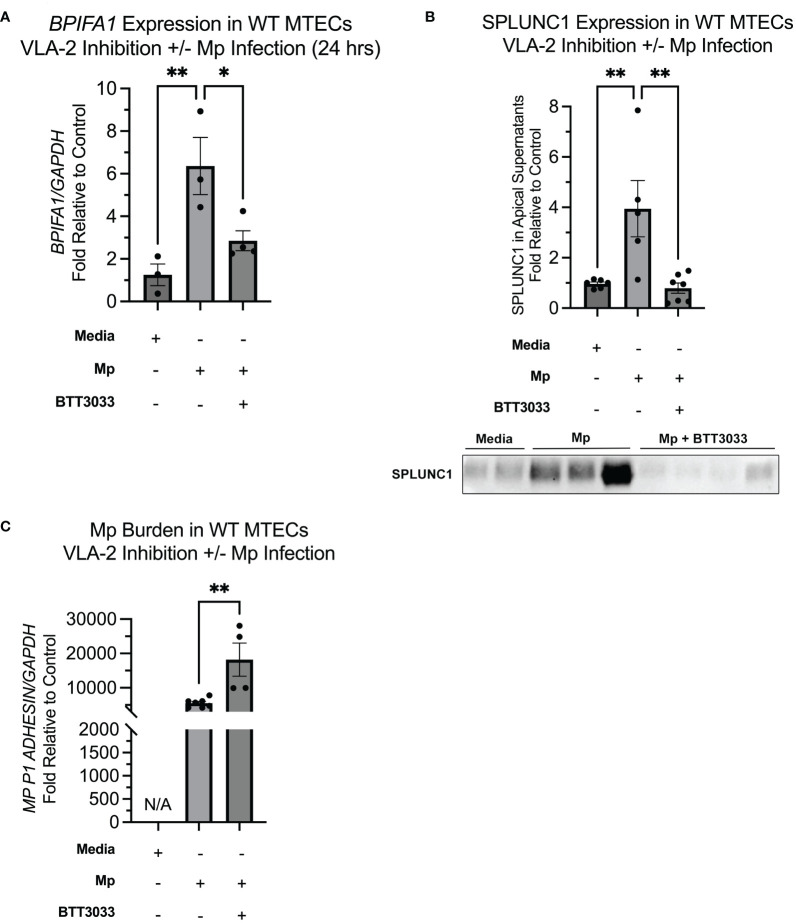

VLA-2 inhibition results in decreased SPLUNC1 during Mp infection

We next sought to determine the impact of CC16 and VLA-2 inhibition on SPLUNC1 expression in the context of Mp infection. Similar to what has been reported by Gally et al., we observed that upon infection with Mp, SPLUNC1 expression is significantly increased, compared to the media only control (Figures 5A, B) (40). Addition of BTT3033 during Mp infection, without exogenous rCC16, resulted in lower levels of SPLUNC1 expression, which we propose is likely due to inhibition of endogenous CC16 from signaling through VLA-2 (Figures 5A, B). The significantly decreased SPLUNC1 levels in the Mp+BTT3033 group correlated to significantly increased Mp burden, compared to control (Figure 5C), which is in line with previous publications that demonstrated SPLUNC1 activity against Mp infection (17).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of VLA-2 results in decreased SPLUNC1 expression and increased Mp burden. (A) BPIFA1 gene expression was measured by RT-PCR in WT MTECs treated with media only (n=3), Mp (n=3), Mp+rCC16 (n=4), Mp+rCC16+BTT3033 (n=4), or Mp+BTT3033 (n=4). GAPDH was used as a housekeeping control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by One-Way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (B) Apical SPLUNC1 protein expression was measured in the same samples from panel A, as well as additional experimental samples to confirm reproducibility, by western blotting. A representative blot is shown. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by One-Way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (C) Mp burden was measured in the same samples from panels A by RT-PCR. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by One-Way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Data are presented as mean±SEM.

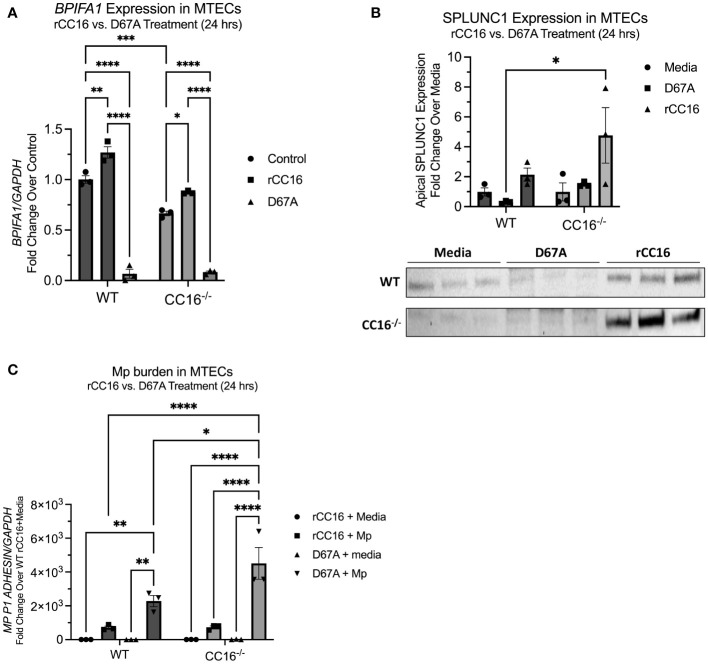

Mutant D67A rCC16 fails to increase SPLUNC1 expression in MTECs

To determine if the LVD integrin binding site within CC16 is necessary for induction of SPLUNC1 expression via VLA-2 interactions, we treated WT and CC16-/- MTECs with a mutant rCC16 that has a mutation in the leucine-valine-aspartic acid (LVD) motif as described previously (8). Our group has previously shown that this mutant rCC16 (D67A rCC16) is unable to bind to the VLA-4 integrin complex (8). Upon treatment with the mutant D67A rCC16, not only did the mutant fail to promote an increase in SPLUNC1, but we also actually observed significantly decreased SPLUNC1 expression by both WT and CC16-/- MTECs (Figures 6A, B). In line with decreased SPLUNC1, we also observed significantly increased Mp burden from MTECs treated with D67A rCC16 (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

D67A rCC16 does not induce SPLUNC1 expression and results in increased Mp burden. (A) Bpifa1 expression was measured by RT-PCR in WT and CC16-/- MTECs that were treated with media, WT rCC16, and mutant D67A rCC16 for 24 hrs. Gapdh was used as a housekeeping control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 by Two-Way ANOVA Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. (B) SPLUNC1 expression was measured in the same samples as panel (A) by western blotting. *P<0.05 by Two-Way ANOVA Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. (C) Mp burden was measured by RT-PCR in WT and CC16-/- MTECs that were infected with Mp or treated with media during rCC16 and/or mutant D67A rCC16 treatment for 24 hrs. Gapdh was used as a housekeeping control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 by Two-Way ANOVA Šídák’s multiple comparisons test.

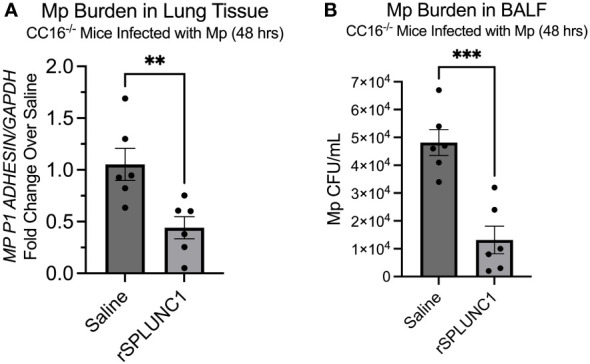

rSPLUNC1 treatment decreases Mp burden in CC16-/- mice

Since our data suggests that SPLUNC1 expression is dependent on the presence of CC16, we aimed to demonstrate that rSPLUNC1 treatment could decrease and “rescue” Mp burden in CC16-/- mice. CC16-/- mice were infected with Mp, followed by treatment with rSPLUNC. Mp burden was assessed in lung tissue and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). Treatment with rSPLUNC1 resulted in significantly decreased Mp burden in both the lungs and BALF from the CC16-/- mice (Figures 7A, B). These data suggest that rSPLUNC1 treatment may benefit individuals with decreased CC16 levels and recurrent Mp infections, such as asthma, COPD, and cystic fibrosis patients (10, 11, 17, 37, 41–47).

Figure 7.

rSPLUNC1 treatment decreases Mp burden in CC16-/- mice. (A) Mp burden was measured by RT-PCR in lung tissue from CC16-/- infected with Mp, followed by rescue with rSPLUNC1 treatment. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping control. **P<0.01 by Unpaired t-test. (B) Mp burden was measured in the BALF from these same mice in panel (A); however, Mp burden was measured by plating samples on PPLO agar, followed by counting colonies, to determine Mp CFU/mL. ***P<0.001 by Unpaired t-test.

Discussion

CC16 has been shown to protect from lung function deficits in the setting of infectious as well as non-infectious conditions, partly through its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects (7–10); however, the mechanisms by which CC16 exerts these effects, especially regarding the pulmonary epithelium, have not been fully elucidated. To better understand if and how CC16 regulates the expression of pulmonary epithelial-driven antimicrobial proteins, we utilized mass spectrometry and quantitative proteomics to identify apically secreted proteins from WT and CC16-/- MTECs. Using this approach, we are the first, to our knowledge, to show that SPLUNC1 expression is induced by CC16 within the pulmonary epithelium, which we validated in human primary airway cells. Further, we show in MTECs and HNECs that CC16 signals through the VLA-2 integrin complex within the pulmonary epithelium to induce SPLUNC1 expression. The identification of VLA-2 as novel receptor for CC16 on the respiratory epithelia provides another layer of understanding for how CC16 provides protection in the airway by another direct integrin interaction, in addition to the interaction with VLA-4 on circulating leukocytes.

Since studies have previously defined that low serum and BALF CC16 levels associate with declines in lung function in patients (7, 10–12, 14), our work now sheds light on a novel mechanism by which low CC16 contributes to decreased expression of epithelial-driven antimicrobials, which likely results in more persistent respiratory infections and a decrease in lung function over time. Low SPLUNC1 has been shown to result in decreased ASL volume, altered mucociliary clearance, decreased lung function, and increased pathogen burden during infection (10–12, 14). Based on these previous publications in which SPLUNC1 activity has been defined, one can surmise that the clinical implications for individuals with low CC16 levels, such as asthma, COPD, and cystic fibrosis patients (10–12, 14), is that they may also have decreased pulmonary SPLUNC1 levels and therefore a myriad of SPLUNC1-deficiency related respiratory symptoms.

Previously, our group showed that CC16-/- mice and MTECs had higher Mp burden after infection compared to their WT counterparts (8, 9). In support of our published findings, we identified 8 antimicrobial proteins from MTECs, 6 of which were corroborated by bronchial gene expression in the SARP cohorts, whose expression appears to be associated with the level of CC16, each of which may aid in the resolution of Mp infection, as well as additional respiratory pathogens. SPLUNC1 was the antimicrobial protein that was the most differentially regulated between WT MTECs and CC16-/- MTECs; therefore, further studies were conducted to better understand how CC16 regulates the expression of SPLUNC1. SPLUNC1 has been shown to have direct antimicrobial activity against Mp (40); therefore, the decreased expression of this protein by CC16-/- MTECs provides mechanistic insight into the observed increased Mp burden in these MTECs (9). Translationally, this suggests that therapeutics targeting at increasing or replacing CC16 could provide benefit to individuals that have decreased pulmonary SPLUNC1 levels, such as cystic fibrosis patients (47–49), asthmatics (44, 50–52), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients (19, 53, 54), as these individuals may have decreased clearance of Mp infections leading to increased pathogen burden and decreased lung function. Interestingly, and supportive of our findings, each of these diseased populations have been shown to have decreased CC16 levels as well (7, 10–12), although the mechanistic connection between CC16 and SPLUNC1 had not been made.

To determine if CC16 could enhance expression of SPLUNC1, we added rCC16 to WT and CC16-/- MTECs, after which we measured SPLUNC1 expression at the gene and protein level. rCC16-treated WT and CC16-/- MTECs had significantly increased SPLUNC1 gene and protein expression, compared to their control-treated counterparts, indicating that CC16 can activate SPLUNC1 expression within the pulmonary epithelium and that CC16-/- MTECs can generate SPLUNC1 if given exogenous CC16. We further confirmed this in vivo, by performing a rescue experiment by intravenously treating CC16-/- mice for 3 days with rCC16 and assessing SPLUNC1 levels in BALF. We observed significantly increased SPLUNC1 levels in the BALF from CC16-/- mice treated with rCC16, compared to saline-treated CC16-/- mice. Interestingly, since we treated these mice intravenously, these data suggest that systemic rCC16 can rescue SPLUNC1 levels within the lung, which provides a path forward to consider therapeutic development of a systemic delivery as opposed to lung only delivery. Our group has similarly observed that intravenously administered rCC16 decreased airway hyperresponsiveness and resistance during methacholine treatment of Mp-infected WT and CC16-/- mice (8); therefore, further supporting the claim that circulating CC16 exerts protective effects within the lung.

Correlation analysis in human data cohorts showed that CC16 and SPLUNC1 are significantly and positively correlated. Two human cohorts – SARP1-2 and SARP3 – were used to correlate CC16 and Splunc1 mRNA levels to ascertain clinical relevance. Asthmatics within the cohorts had positive Rho values and p values ≤ 0.05, confirming there is a significant and positive correlation between SCGB1A1 and BPIFA1 mRNA levels.

Since we determined that CC16 was not directly activating the BPIFA1 promoter, or signaling through TLR2 to activate SPLUNC1, we next decided to focus on CC16 signaling through integrins on the pulmonary epithelium to induce SPLUNC1 expression. Our group has previously shown that CC16 binds to VLA-4 on leukocytes, thereby preventing extravasation into the lung and decreasing exuberant airway inflammation during Mp infection (8). While VLA-4 levels were very low to non-detectable in airway respiratory cells, using single cell RNA-seq data, we determined that VLA-2 is highly expressed within the pulmonary epithelium; therefore, we thought that it was highly likely that VLA-2 might be a previously undiscovered binding partner for CC16. Studies have shown that VLA-2 is not only highly expressed on airway bronchial epithelial cells but is also apically expressed; therefore, possibly playing a role in cell signaling (55–57). Based on this, we inhibited VLA-2 to determine if CC16 is signaling through this integrin complex to induce SPLUNC1 expression. We observed that VLA-2 was essential for rCC16 to increase SPLUNC1 expression in WT MTECs and healthy HNECs. Additionally, we show that expression of the alpha-2 (gene name: ITGA2), but not beta-1 (gene name: ITGB1), is significantly (5.4x10-6) and positively correlated to CC16 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells, which suggests a potential greater interaction between CC16 and the alpha subunit of VLA-2.

Using “ISLAND: In silico protein affinity predictor” (30) we were able to predict the binding affinity of CC16 and VLA-2. These results showed that the binding affinity between CC16 and VLA-2, particularly the α2 subunit, was favorable (ΔΔG = -10.861 J) and the dissociation constant (Kd) exhibited strong binding (1.08x10-8 M). Furthermore, using in silico protein 3D structure models, we confirmed by Fiberdock energy scoring that CC16 preferentially binds to the α2 subunit of the α2β1 integrin receptor complex. This finding is in line with the human data from the SARP cohort that indicated significant associations between BEC CC16 expression and the α2, but not the β1, subunit. To further support this interaction, we treated WT and CC16-/- MTECs with WT and mutant (D67A) rCC16 (8), followed by assessment of SPLUNC1 expression and Mp burden. As previously described, D67A rCC16 has a mutation in the leucine-valine-aspartic acid (LVD) binding motif, and we have shown that this mutation limits binding between CC16 and VLA-4 on leukocytes (8). Not only does our data show that treatment of MTECs with D67A inhibits SPLUNC1 expression, but it seems to repress expression of SPLUNC1 below baseline levels, although future studies are needed to better understand mechanisms driving this observation. Along these lines, we observed that the MTECs treated with the mutant D67A rCC16 had significantly increased Mp burden, which corresponds to the decreased SPLUNC1 expression within these samples. Taken together these data suggest that the previously detailed integrin binding site is also relevant for CC16’s interaction with VLA-2 within the pulmonary epithelium.

We next wanted to study the impact of CC16 and VLA-2 inhibition on Mp burden. As previously described by Chu et al., we observed that Mp infection increases expression of SPLUNC1 (17). We also observed that VLA-2 inhibition during Mp infection results in significantly decreased SPLUNC1 expression and subsequently increased Mp burden. We have previously shown that Mp infection increases expression of CC16 (8); therefore, these data suggest that VLA-2 inhibition was able to block endogenous CC16 from signaling during Mp infection.

We then went on to assess if rSPLUNC1 treatment would decrease Mp burden in the absence of CC16. We infected CC16-/- mice with Mp, followed by treatment with rSPLUNC1 for 48 hrs. We observed that rSPLUNC1 treatment significantly decreased Mp burden within the lungs and BALF of these mice; therefore, rSPLUNC1 may be a viable treatment for individuals with decreased CC16 levels, such as asthma (8, 9, 11, 58), COPD (7, 10, 13, 45), and cystic fibrosis (14) patients, who have significantly decreased CC16 levels.

Overall, our data, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to show that CC16 induces the expression of a major pulmonary epithelial-driven antimicrobial protein, SPLUNC1, by signaling through VLA-2. We provided evidence that CC16 and SPLUNC1 are significantly and positively correlated within the pulmonary epithelium of mice and humans. Future studies are needed to determine if CC16 induces the expression of the other identified antimicrobial proteins (shown in Figure 1, Table 1) through this same mechanism of action or if there are other novel receptors and mechanisms by which CC16 is signaling within the pulmonary epithelium to promote host defense against respiratory infections. Additionally, further studies are needed to determine if there are potential sex differences regulating CC16 and SPLUNC1 expression, although none were detected in our studies using both male and female mice. Clinically, these results suggest that individuals with low CC16 may have decreased SPLUNC1 and higher susceptibility to Mp infection and that administration of CC16 as a therapeutic may be important to activate the expression of SPLUNC1 to aid in the induction of antimicrobial responses and decrease pathogen burden. Since several chronic respiratory diseases have been associated with low CC16 levels, including asthma (42, 43, 59–61), COPD (1, 6, 10, 46, 62–65), and cystic fibrosis (14), those individuals may be at an increased risk for respiratory infections due to loss of SPLUNC1 as well as low CC16. Taken together, our findings reinforce the potential of CC16 augmentation as a novel therapeutic approach to enhance resilience to respiratory infections among a variety of airway diseases.

Data availability statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD046830 and 10.6019/PXD046830. Additionally, publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. For the single-cell sequencing data, this dataset can be found here: GitHub [https://github.com/seiboldlab/SingleCell_smoking].

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board at the University of Arizona. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The animal study was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Arizona. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

NI: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HW: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. NL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. MJ: Formal Analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing. JR-Q: Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. FP: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. SG: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. XL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. DC: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Validation. PL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JL: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Hong Wei Chu for valuable discussions relating to SPLUNC1, and to Dr. Fernando Martinez for review and discussion of our manuscript.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding was obtained from NHBLI (Awards: HL142769 and T32 HL007249-44/45) and NIAID (Award: AI135108).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1277582/full#supplementary-material

Intracellular SPLUNC1 is not impacted by CC16 deficiency. SPLUNC1 protein expression was confirmed for control-treated WT and CC16-/- MTECs lysates (n=3), and CC16-/- mice (n=4) by western blotting. The same amount of protein (10 μg) was loaded for each sample. SPLUNC1 protein levels are normalized to GAPDH. Data are presented as mean±SEM.

Scatter plot of SCGB1A1 and BPIFA1 normalized expression within mucus secretory cells. Each point represents an individual cell. Pearson correlation coefficient (p-value = 9.7 x10-31) displayed above graph. The blue line is a regression line fit to the expression values of these two genes.

Representative major epithelial cell populations in WT and CC16-/- mouse lungs by flow cytometry. Club (CYP2F2), ciliated (TUBA1A), goblet (MUC5AC), and basal (KRT5) cell percentages were measured in WT (A) and CC16-/- (B) mouse lungs by flow cytometry. Alexa Flour 647 was used as the secondary antibody for detection of club, ciliated, and goblet cells. Alexa Fluor 488 was used as the secondary antibody for detection of basal cells. Gray histograms represent unstained cells; black histograms represent isotype controls; and blue histograms represent experimental antibody.

Representative major epithelial cell populations in WT and CC16-/- MTECs by flow cytometry. Club (CYP2F2), ciliated (TUBA1A), goblet (MUC5AC), and basal (KRT5) cell percentages were measured in WT (A) and CC16-/- (B) MTECs by flow cytometry. Alexa Flour 647 was used as the secondary antibody for detection of club, ciliated, and goblet cells. Alexa Fluor 488 was used as the secondary antibody for detection of basal cells. Gray histograms represent unstained cells; black histograms represent isotype controls; and blue histograms represent experimental antibody.

CC16 does not directly activate the SPLUNC1 promoter. NCI-H292 were transfected with a SPLUNC1 promoter reporter construct containing a novel luminescent reporter gene (RenSP luciferase). After transfection (24 hrs), media or rCC16 (A), apically secreted proteins from WT and CC16-/- MTECs (B), and WT and CC16-/- MTEC lysates (C) were added to the transfected NCI-H292 cells (24 hrs), after which promoter activity was measured by luminescence. An actin beta (ACTB) promoter vector was used as a positive control; a random genomic fragment promoter vector was used as a negative control; and the SPLUNC1 promoter vector was used as the experimental condition. ****P<0.0001 by Two-Way ANOVA Šidák’s multiple comparison test. Data are presented as mean±SEM.

CC16 activation of SPLUNC1 expression is independent of TLR2. (A) WT MTECs (n=4; except α-TLR2+rCC16 n=3) were treated with either a TLR2 blocking antibody (α-TLR2) or an isotype control antibody (IgG1) (10 μg/mL) for 30 min, followed by treatment with media only, rCC16 (25 μg/mL), or Pam3CSK4 (1 μg/mL) for 24 hrs. Following the treatments, Splunc1 gene expression was measured by RT-PCR with Gapdh as a housekeeping control. *P<0.05 by One-Way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (B) SPLUNC1 apical protein expression was assessed for media-, rCC16-, and Pam3CSK4-treated WT MTECs following incubation with an α-TLR2 antibody or IgG1 isotype antibody (10 μg/mL) by western blotting (n=3 per group). The same volume of protein (20μl) was loaded for each sample. **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 by One-Way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

References

- 1. Broeckaert F, Bernard A. Clara cell secretory protein (CC16): characteristics and perspectives as lung peripheral biomarker. Clin Exp Allergy (2000) 30:469–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00760.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rong B, Fu T, Gao W, Li M, Rong C, Liu W, et al. Reduced serum concentration of CC16 is associated with severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and contributes to the diagnosis and assessment of the disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis (2020) 15:461–70. doi: 10.2147/copd.S230323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hermans C, Petrek M, Kolek V, Weynand B, Pieters T, Lambert M, et al. Serum Clara cell protein (CC16), a marker of the integrity of the air-blood barrier in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J (2001) 18:507–14. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.99102601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mukherjee AB, Zhang Z, Chilton BS. Uteroglobin: A steroid-inducible immunomodulatory protein that founded the secretoglobin superfamily. Endocrine Rev (2007) 28:707–25. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mango GW, Johnston CJ, Reynolds SD, Finkelstein JN, Plopper CG, Stripp BR. Clara cell secretory protein deficiency increases oxidant stress response in conducting airways. Am J Physiol (1998) 275:L348–356. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.2.L348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Laucho-Contreras ME, Polverino F, Tesfaigzi Y, Pilon A, Celli BR, Owen CA. Club cell protein 16 (CC16) augmentation: A potential disease-modifying approach for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Expert Opin Ther Targets (2016) 20:869–83. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2016.1139084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhai J, Insel M, Addison KJ, Stern DA, Pederson W, Dy A, et al. Club cell secretory protein deficiency leads to altered lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2019) 199:302–12. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1345oc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson MDL, Younis US, Menghani SV, Addison KJ, Whalen M, Pilon AL, et al. CC16 Binding to α(4)β(1) Integrin Protects against Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2021) 203:1410–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2576OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iannuzo N, Insel M, Marshall C, Pederson WP, Addison KJ, Polverino F, et al. CC16 deficiency in the context of early-life mycoplasma pneumoniae infection results in augmented airway responses in adult mice. Infect Immun (2022) 90:e0054821. doi: 10.1128/iai.00548-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guerra S, Halonen M, Vasquez MM, Spangenberg A, Stern DA, Morgan WJ, et al. Relation between circulating CC16 concentrations, lung function, and development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease across the lifespan: a prospective study. Lancet Respir Med (2015) 3:613–20. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(15)00196-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guerra S, Vasquez MM, Spangenberg A, Halonen M, Martin RJ. Club cell secretory protein in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage of patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2016) 138:932–934.e931. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.03.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rava M, Tares L, Lavi I, Barreiro E, Zock J-P, Ferrer A, et al. Serum levels of Clara cell secretory protein, asthma, and lung function in the adult general population. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2013) 132:230–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Silva GE, Sherrill DL, Guerra S, Barbee RA. Asthma as a risk factor for COPD in a longitudinal study. Chest (2004) 126:59–65. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhai J, Emond MJ, Spangenberg A, Stern DA, Vasquez MM, Blue EE, et al. Club cell secretory protein and lung function in children with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros (2022) 21(5):811–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2022.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li X, Hawkins GA, Moore WC, Hastie AT, Ampleford EJ, Milosevic J, et al. Expression of asthma susceptibility genes in bronchial epithelial cells and bronchial alveolar lavage in the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) cohort. J Asthma (2016) 53:775–82. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2016.1158268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahmad S, Kim CSK, Tarran R. The SPLUNC1-βENaC complex prevents Burkholderia cenocepacia invasion in normal airway epithelia. Respir Res (2020) 21:190. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01454-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chu HW, Thaikoottathil J, Rino JG, Zhang G, Wu Q, Moss T, et al. Function and regulation of SPLUNC1 protein in Mycoplasma infection and allergic inflammation. J Immunol (2007) 179:3995–4002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Di YP. Functional roles of SPLUNC1 in the innate immune response against Gram-negative bacteria. Biochem Soc Trans (2011) 39:1051–5. doi: 10.1042/bst0391051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jiang D, Wenzel SE, Wu Q, Bowler RP, Schnell C, Chu HW. Human neutrophil elastase degrades SPLUNC1 and impairs airway epithelial defense against bacteria. PloS One (2013) 8:e64689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jiang S, Deslouches B, Chen C, Di ME, Di YP. Antibacterial properties and efficacy of a novel SPLUNC1-derived antimicrobial peptide, α4-short, in a murine model of respiratory infection. mBio (2019) 10:e00226–19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00226-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu Y, Di ME, Chu HW, Liu X, Wang L, Wenzel S, et al. Increased susceptibility to pulmonary pseudomonas infection in splunc1 knockout mice. J Immunol (2013) 191:4259–68. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eenjes E, Mertens TCJ, Kempen MJB-v, Wijck Yv, Taube C, Rottier RJ, et al. A novel method for expansion and differentiation of mouse tracheal epithelial cells in culture. Sci Rep (2018) 8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25799-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. James J, Varghese MV, Vasilyev M, Langlais PR, Tofovic SP, Rafikova O, et al. Complex III inhibition-induced pulmonary hypertension affects the mitochondrial proteomic landscape. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21. doi: 10.3390/ijms21165683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kruse R, Krantz J, Barker N, Coletta RL, Rafikov R, Luo M, et al. Characterization of the CLASP2 protein interaction network identifies SOGA1 as a microtubule-associated protein. Mol Cell Proteomics (2017) 16:1718–35. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA117.000011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parker SS, Krantz J, Kwak E-A, Barker NK, Deer CG, Lee NY, et al. Insulin induces microtubule stabilization and regulates the microtubule plus-end tracking protein network in adipocytes. Mol Cell Proteomics (2019) 18:1363–81. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA119.001450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goldfarbmuren KC, Jackson ND, Sajuthi SP, Dyjack N, Li KS, Rios CL, et al. Dissecting the cellular specificity of smoking effects and reconstructing lineages in the human airway epithelium. Nat Commun (2020) 11:2485. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16239-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tuncbag N, Gursoy A, Nussinov R, Keskin O. Predicting protein-protein interactions on a proteome scale by matching evolutionary and structural similarities at interfaces using PRISM. Nat Protoc (2011) 6:1341–54. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mashiach E, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. FiberDock: a web server for flexible induced-fit backbone refinement in molecular docking. Nucleic Acids Res (2010) 38:W457–461. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Macalino SJY, Basith S, Clavio NAB, Chang H, Kang S, Choi S. Evolution of in silico strategies for protein-protein interaction drug discovery. Molecules (2018) 23. doi: 10.3390/molecules23081963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Abbasi WA, Yaseen A, Hassan FU, Andleeb S, Minhas FUAA. ISLAND: in-silico proteins binding affinity prediction using sequence information. BioData Min (2020) 13:20. doi: 10.1186/s13040-020-00231-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, Teague WG, Li H, Li X, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2010) 181:315–23. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Teague WG, Phillips BR, Fahy JV, Wenzel SE, Fitzpatrick AM, Moore WC, et al. Baseline features of the severe asthma research program (SARP III) cohort: differences with age. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract (2018) 6:545–554.e544. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li X, Christenson SA, Modena B, Li H, Busse WW, Castro M, et al. Genetic analyses identify GSDMB associated with asthma severity, exacerbations, and antiviral pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2021) 147:894–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schulze R. Meta-Analysis - A Comparison of Approaches. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe Publishing; (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bingle L, Bingle CD. Distribution of human PLUNC/BPI fold-containing (BPIF) proteins. Biochem Soc Trans (2011) 39:1023–7. doi: 10.1042/bst0391023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Britto CJ, Liu Q, Curran DR, Patham B, Cruz CSD, Cohn L. Short palate, lung, and nasal epithelial clone-1 is a tightly regulated airway sensor in innate and adaptive immunity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2013) 48:717–24. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0072OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bingle L, Barnes FA, Cross SS, Rassl D, Wallace WA, Campos MA, et al. Differential epithelial expression of the putative innate immune molecule SPLUNC1 in cystic fibrosis. Respir Res (2007) 8:79. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thaikoottathil J, Chu HW. MAPK/AP-1 activation mediates TLR2 agonist-induced SPLUNC1 expression in human lung epithelial cells. Mol Immunol (2011) 49:415–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chu HW, Gally F, Thaikoottathil J, Janssen-Heininger YM, Wu Q, Zhang G, et al. SPLUNC1 regulation in airway epithelial cells: role of toll-like receptor 2 signaling. Respir Res (2010) 11:155. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gally F, Di YP, Smith SK, Minor MN, Liu Y, Bratton DL, et al. SPLUNC1 promotes lung innate defense against Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in mice. Am J Pathol (2011) 178:2159–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jung C-G, Cao TBT, Quoc QL, Yang E-M, Ban G-Y, Par H-S. Role of club cell 16-kDa secretory protein in asthmatic airways. Clin Exp Allergy (2023) 53:648–58. doi: 10.1111/cea.14315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Laing IA, Hermans C, Bernard A, Burton PR, Goldblatt J, Le Souëf PN. Association between plasma CC16 levels, the A38G polymorphism, and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2000) 161:124–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9904073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li X, Guerra S, Ledford JG, Kraft M, Li H, Hastie AT, et al. Low CC16 mRNA expression levels in bronchial epithelial cells are associated with asthma severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2023) 438–51. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202206-1230OC. null. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schaefer N, Li X, Seibold MA, Jarjour NN, Denlinger LC, Castro M, et al. The effect of BPIFA1/SPLUNC1 genetic variation on its expression and function in asthmatic airway epithelium. JCI Insight (2019) 4. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.127237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Braido F, Riccio AM, Guerra L, Gamalero C, Zolezzi A, Tarantini F, et al. Clara cell 16 protein in COPD sputum: a marker of small airways damage? Respir Med (2007) 101:2119–24. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Laucho-Contreras ME, Polverino F, Gupta K, Taylor KL, Kelly E, Pinto-Plata V, et al. Protective role for club cell secretory protein-16 (CC16) in the development of COPD. Eur Respir J (2015) 45:1544. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00134214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Khanal S, Webster M, Niu N, Zielonka J, Nunez M, Chupp G, et al. SPLUNC1: a novel marker of cystic fibrosis exacerbations. Eur Respir J (2021) 58. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00507-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Webster MJ, Reidel B, Tan CD, Ghosh A, Alexis NE, Donaldson SH, et al. SPLUNC1 degradation by the cystic fibrosis mucosal environment drives airway surface liquid dehydration. Eur Respir J (2018) 52. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00668-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Terryah ST, Fellner RC, Ahmad S, Moore PJ, Reidel B, Sesma JI, et al. Evaluation of a SPLUNC1-derived peptide for the treatment of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol (2018) 314:L192–l205. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00546.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thaikoottathil JV, Martin RJ, Di PY, Minor M, Case S, Zhang B, et al. SPLUNC1 deficiency enhances airway eosinophilic inflammation in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2012) 47:253–60. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0064OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wrennall JA, Ahmad S, Worthington EN, Wu T, Goriounova AS, Voeller AS, et al. A SPLUNC1 peptidomimetic inhibits orai1 and reduces inflammation in a murine allergic asthma model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2022) 66:271–82. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2020-0452OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vlahos R. SPLUNC1 α6 peptidomimetic: A novel therapeutic for asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2022) 66:241–2. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2021-0451ED [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Moore PJ, Reidel B, Ghosh A, Sesma J, Kesimer M, Tarran R, et al. Cigarette smoke modifies and inactivates SPLUNC1, leading to airway dehydration. FASEB J (2018) 32:fj201800345R. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800345R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moore PJ, Sesma J, Alexis NE, Tarran R. Tobacco exposure inhibits SPLUNC1-dependent antimicrobial activity. Respir Res (2019) 20:94. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1066-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schoenenberger CA, Zuk A, Zinkl GM, Kendall D, Matlin KS. Integrin expression and localization in normal MDCK cells and transformed MDCK cells lacking apical polarity. J Cell Sci (1994) 107:527–41. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.2.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Peterson RJ, Koval M. Above the matrix: functional roles for apically localized integrins. Front Cell Dev Biol (2021) 9:699407. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.699407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sheppard D. Functions of pulmonary epithelial integrins: from development to disease. Physiol Rev (2003) 83:673–86. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00033.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ledford J, Guerra S, Martinez F, Kraft M. Club cell secretory protein: a key mediator in Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Eur Respir J (2018) 52. doi: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2018.PA4972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Goudarzi H, Kimura H, Kimura H, Makita H, Takimoto-Sato M, Abe Y, et al. Association of serum CC16 levels with eosinophilic inflammation and respiratory dysfunction in severe asthma. Respir Med (2023) 206. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2022.107089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sengler C, Heinzmann A, Jerkic S-P, Haider A, Sommerfeld C, Niggemann B, et al. Clara cell protein 16 (CC16) gene polymorphism influences the degree of airway responsiveness in asthmatic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2003) 111:515–9. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stenberg H, Wadelius E, Moitra S, Åberg I, Ankerst J, Diamant Z, et al. Club cell protein (CC16) in plasma, bronchial brushes, BAL and urine following an inhaled allergen challenge in allergic asthmatics. Biomarkers (2018) 23:51–60. doi: 10.1080/1354750x.2017.1375559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chen M, Xu K, He Y, Jin J, Mao R, Gao L, et al. CC16 as an inflammatory biomarker in induced sputum reflects chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) severity. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis (2023) 18:705–17. doi: 10.2147/copd.S400999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pang M, Liu H-Y, Li T, Wang D, Hu X-Y, Zhang X-R, et al. Recombinant club cell protein 16 (CC16) ameliorates cigarette smoke−induced lung inflammation in a murine disease model of COPD. Mol Med Rep (2018) 18(2):2198–206. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rojas-Quintero J, Laucho-Contreras ME, Wang X, Fucci Q-A, Burkett PR, Kim S-J, et al. CC16 augmentation reduces exaggerated COPD-like disease in Cc16-deficient mice. JCI Insight (2023) 8. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.130771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhai J, Stern DA, Sherrill DL, Spangenberg AL, Wright AL, Morgan WJ, et al. Trajectories and early determinants of circulating CC16 from birth to age 32 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2018) 198:267–70. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201712-2398LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Intracellular SPLUNC1 is not impacted by CC16 deficiency. SPLUNC1 protein expression was confirmed for control-treated WT and CC16-/- MTECs lysates (n=3), and CC16-/- mice (n=4) by western blotting. The same amount of protein (10 μg) was loaded for each sample. SPLUNC1 protein levels are normalized to GAPDH. Data are presented as mean±SEM.

Scatter plot of SCGB1A1 and BPIFA1 normalized expression within mucus secretory cells. Each point represents an individual cell. Pearson correlation coefficient (p-value = 9.7 x10-31) displayed above graph. The blue line is a regression line fit to the expression values of these two genes.

Representative major epithelial cell populations in WT and CC16-/- mouse lungs by flow cytometry. Club (CYP2F2), ciliated (TUBA1A), goblet (MUC5AC), and basal (KRT5) cell percentages were measured in WT (A) and CC16-/- (B) mouse lungs by flow cytometry. Alexa Flour 647 was used as the secondary antibody for detection of club, ciliated, and goblet cells. Alexa Fluor 488 was used as the secondary antibody for detection of basal cells. Gray histograms represent unstained cells; black histograms represent isotype controls; and blue histograms represent experimental antibody.

Representative major epithelial cell populations in WT and CC16-/- MTECs by flow cytometry. Club (CYP2F2), ciliated (TUBA1A), goblet (MUC5AC), and basal (KRT5) cell percentages were measured in WT (A) and CC16-/- (B) MTECs by flow cytometry. Alexa Flour 647 was used as the secondary antibody for detection of club, ciliated, and goblet cells. Alexa Fluor 488 was used as the secondary antibody for detection of basal cells. Gray histograms represent unstained cells; black histograms represent isotype controls; and blue histograms represent experimental antibody.