Key Point

-

•

Risky health behaviors were associated with increased hazard of all-cause and nonrelapse–related late mortality after BMT.

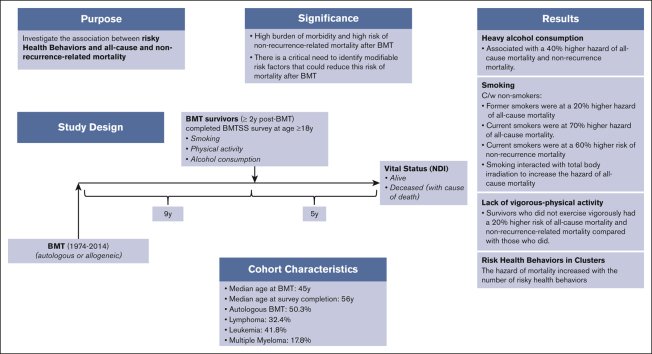

Visual Abstract

Abstract

We examined the association between risky health behaviors (smoking, heavy alcohol consumption, and lack of vigorous physical activity) and all-cause and cause-specific late mortality after blood or marrow transplantation (BMT) to understand the role played by potentially modifiable risk factors. Study participants were drawn from the BMT Survivor Study (BMTSS) and included patients who received transplantation between 1974 and 2014, had survived ≥2 years after BMT, and were aged ≥18 years at study entry. Survivors provided information on sociodemographic characteristics, chronic health conditions, and health behaviors. National Death Index was used to determine survival and cause of death. Multivariable regression analyses determined the association between risky health behaviors and all-cause mortality (Cox regression) and nonrecurrence-related mortality (NRM; subdistribution hazard regression), after adjusting for relevant sociodemographic, clinical variables and therapeutic exposures. Overall, 3866 participants completed the BMTSS survey and were followed for a median of 5 years to death or 31 December 2021; and 856 participants (22.1%) died after survey completion. Risky health behaviors were associated with increased hazard of all-cause mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] former smoker, 1.2; aHR current smoker, 1.7; reference, nonsmoker; aHR heavy drinker, 1.4; reference, nonheavy drinker; and aHR no vigorous activity, 1.2; reference, vigorous activity) and NRM (aHR former smoker, 1.3; aHR current smoker, 1.6; reference, nonsmoker; aHR heavy drinker, 1.4; reference: nonheavy drinker; and aHR no vigorous activity, 1.2; reference, vigorous activity). The association between potentially modifiable risky health behaviors and late mortality offers opportunities for development of interventions to improve both the quality and quantity of life after BMT.

Introduction

Blood or marrow transplantation (BMT) is an established therapeutic option for patients with hematologic malignancies and other life-threatening illnesses. Over 20 000 individuals in the United States receive BMT every year.1,2 Although improvement in transplantation strategies and supportive care have resulted in a decline in early mortality, BMT recipients carry a significant burden of late-occurring morbidity that is directly related to therapeutic exposures and places the survivors at high risk for late mortality when compared with the general population.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Previous studies suggest that the risk of mortality remains elevated for at least 30 years after BMT.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 A recent report from the BMT Survivor Study (BMTSS) showed that the excess mortality translates into 8.7 years of life lost per person, conditional on surviving the first 2 years after allogeneic BMT.22 Previous studies have identified nonmodifiable factors associated with late mortality (eg, refractory disease and therapeutic exposures for control of primary disease).21,22 The association between modifiable factors such as risky health behaviors (smoking, alcohol consumption, and lack of physical activity) and cancer mortality has been documented in epidemiological studies in nontransplant populations.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 However, the association between risky health behaviors and late mortality (all-cause and cause-specific) among BMT survivors, and the interaction between these health behaviors and therapeutic exposures remains unknown. We addressed this knowledge gap by using the resources offered by BMTSS.

Materials and methods

Study participants and data collection

BMTSS is a cohort study, which examines the long-term outcomes of individuals who survived ≥2 years after BMT performed between 1974 and 2014 at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, City of Hope, or University of Minnesota. Study participation consisted of completion of the BMTSS survey by transplant recipients to capture the following: sociodemographics (race/ethnicity, education, annual household income, and health insurance), chronic health conditions as diagnosed by health care providers, chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGvHD), height and weight at the time of study participation that allowed us to calculate body mass index, health behaviors (smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity), and mental health (using Brief Symptom Inventory-18). Chronic health conditions were graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, v5.0.29 Brief Symptom Inventory-18 includes 3 symptom subscales: somatization, depression, and anxiety, with each subscale comprising 6 items; raw scores are converted to T-scores based on gender-specific normative data from community-dwelling US adults.30 Mental health was classified as impaired if the T-score values were ≥63 on any 2 of the 3 subscales.31 Survivors’ age at BMT, sex, primary diagnosis (indication for BMT), type of transplant (autologous or allogeneic), risk of relapse at BMT (standard risk or high risk), conditioning regimen, and conditioning intensity (myeloablative conditioning or nonmyeloablative/reduced intensity conditioning) were retrieved from institutional transplant databases and/or participants’ medical records. National Death Index Plus provided data regarding the date and cause of death till 31 December 2020.32 Additional data from Accurint databases extended vital status information till 31 December 2021. The institutional review board (IRB) at the University of Alabama at Birmingham served as the single IRB of record and approved the study. Participants provided informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. A waiver of consent was granted by the IRB for linking the cohort to National Death Index and Accurint databases. This report includes survivors who were aged ≥18 years at study participation.

Outcome

The primary outcome of interest was death after the completion of the BMTSS survey. Suicides, homicides, and accidents were classified as external causes of death. A cause of death matching the pretransplant diagnosis was classified as recurrence-related mortality (RRM). All other causes of death were classified as nonrecurrence-related mortality (NRM: deaths due to malignant diseases differing from the pretransplant diagnosis [subsequent malignant neoplasms or SMNs], cardiovascular disease, late infections, renal disease, etc).

Exposures

Primary exposures of interest included smoking, alcohol consumption, and lack of vigorous physical activity, examined individually, as well as an ordinal variable: absence of any risky behavior or presence of a single behavior, 2 behaviors, or 3 behaviors.

Smoking

Questions in the BMTSS survey and responses used to classify participants into never smokers, former smokers, and current smokers are detailed in supplemental Table 1.

Alcohol consumption

Questions in the BMTSS survey and responses used to classify participants into never drinkers and drinkers are in supplemental Table 1. Drinkers were further categorized as heavy drinkers and nonheavy drinkers (supplemental Table 1).

Vigorous physical activity

Vigorous physical activity was estimated as the self-reported number of exercise sessions per week (frequency) multiplied by session duration (in minutes), weighted by the standardized classification of energy expenditure for vigorous exercise (ie, metabolic equivalent tasks [METs]) expressed as average MET hour/week-1.33 Levels of vigorous physical activity were defined as 0 MET hour/week-1 (<20 minutes of vigorous exercise/week–1), 3 to <9 MET hour/week-1 (20 minutes to <60 minutes of vigorous exercise/week), and ≥9 MET hour/week–1 (≥60 minutes of vigorous exercise/week) (supplemental Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported using mean (standard deviation), median (range), or counts (percentages) as appropriate. Kaplan-Meier analyses were used to calculate overall survival. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis with time from completing the survey to death or end of study (December 21) as the time axis was used for identifying the association between each risky health behavior (and clusters of risky health behaviors) and all-cause mortality. Cox proportional hazards regression model assumption was examined using Schoenfeld residuals. The following variables were examined for their possible inclusion in the model: age at BMT, sex, race/ethnicity, education, annual household income, health insurance, body mass index, primary diagnosis, disease status at BMT, BMT type (autologous, allogeneic), cGvHD, stem cell source (bone marrow, peripheral blood stem cells, or cord blood), conditioning intensity (myeloablative conditioning or nonmyeloablative/reduced intensity conditioning), conditioning regimen, chronic health conditions, mental health, cancer-related pain and anxiety, time from BMT to survey completion, and BMT era (1974-1989, 1990-2004, and 2005-2014).1 Potential confounders were selected to be included in the multivariable model on the basis of their significant association with late mortality. Race/ethnicity and stem cell source were included in the multivariable analysis because of previous evidence for the association between racial/ethnic and source of stem cell disparities and survival.22,34

Proportional subdistribution hazard (Fine-Gray) models35 were used to examine the association between each risky health behavior (and clusters of risky health behaviors) and NRM; RRM and external causes of death served as competing risk. Survivors with missing or unknown cause of death were excluded from the proportional subdistribution hazard model. We also stratified the analysis by age at study participation (≤56 years; >56 years), years since BMT to study participation (≤10 years; >10 years), age at BMT (<21 years; ≥21 years), and BMT type (autologous; allogeneic). We examined statistical interaction between sex and risky health behaviors and between total body irradiation (TBI) and risky health behaviors to assess whether the effect of risky health behaviors was modified by sex or exposure to TBI.

We used 2003 age-sex–specific US life-table data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention36 to calculate expected population mortality rates (the median year of BMT for the cohort in this study was 2003).

We used the standardized mortality ratio, which is the ratio of observed to expected number of deaths, and compared the mortality experienced by this cohort with the age-, sex-, and calendar-specific mortality of the US population.36 The Poisson regression method was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the standardized mortality ratio. We evaluated excess mortality, which was calculated as the difference between the observed number of deaths among BMT survivors who practiced risky health behaviors and the average excepted number of deaths in the US population.

All analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Findings noted with 2-sided tests were considered statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

Supplemental Figure 1 shows the CONSORT diagram for the study participants. Of 4253 participants approached for study participation, 3866 completed the full version of the BMTSS survey at a median of 9 years (range, 2-41) from BMT. The median length of follow-up from BMTSS survey completion to death or end of follow-up (December 2021) was 5 years (range, 0-22). Of the 3866 study participants, 856 died (22.1%) after survey completion. Table 1 summarizes the clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population. The median age at BMT was 45 years (range, 0-74) and at survey completion was 56 years (range, 18-84). In this cohort, 1944 participants were autologous BMT recipients (50.3%), 1736 were female (44.9%), and 2858 were non-Hispanic White (73.9%). Primary indications for BMT included Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma (32.4%), acute lymphoblastic leukemia/ acute myeloid leukemia/ myelodysplastic syndrome ( 31.6%), plasma cell dyscrasias (17.8%), chronic myeloid leukemia (10.2%), and other diagnoses (8.0%). Peripheral blood stem cells were used as the source of stem cells for 2566 participants (66.4%) and myeloablative conditioning regimens were used in 2673 patients (69.1%). Of the 1922 allogeneic BMT recipients, 1040 carried a history of cGvHD (54.1%). Fifty-eight percent of the survivors reported grade 3 or 4 chronic health conditions (n = 2254); 5% reported impaired mental health, and 4.7% reported cancer-related anxiety.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of study participants by vital status

| Variables of interest | Vital status |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alive N = 3010 (77.9%) |

Deceased N = 856 (22.1%) |

||

| Age at completing the survey in y | |||

| Median (range) | 56 (18-83) | 60 (18-84) | <.0001 |

| Age at completing the survey, n (%) | |||

| ≤56y | 1492 (49.6) | 328 (38.3) | <.0001 |

| >56y | 1518 (50.4) | 528 (61.7) | |

| Follow-up from completing the survey to death or end offollow-upin y | |||

| Median (range) | 6 (1-22) | 4 (0-22) | <.0001 |

| BMT era, n (%) | |||

| 1974-1989 | 210 (7.0) | 108 (12.6) | <.0001 |

| 1990-2004 | 1249 (41.5) | 418 (48.8) | |

| 2005-2014 | 1551 (51.5) | 330 (38.5) | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 1428 (47.4) | 308 (36.0) | <.0001 |

| Male | 1582 (52.6) | 548 (64.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| African American | 154 (5.1) | 30 (3.5) | .1131 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2204 (73.2) | 654 (76.4) | |

| Hispanic | 398 (13.2) | 112 (13.1) | |

| Asian | 168 (5.6) | 34 (4.0) | |

| Other∗ | 83 (2.8) | 26 (3.0) | |

| Missing | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Health insurance, n (%) | |||

| Not insured | 98 (3.3) | 34 (4.0) | .2700 |

| Insured | 2887 (95.9) | 801 (93.6) | |

| Missing | 25 (0.8) | 21 (2.4) | |

| Annual household income, n (%) | |||

| <$19 999 | 848 (28.2) | 250 (29.2) | <.0001 |

| $20 000-$49 999 | 510 (16.9) | 219 (25.6) | |

| >$50 000 | 1366 (45.4) | 313 (36.6) | |

| Missing | 286 (9.5) | 74 (8.6) | |

| Educational status, n (%) | |||

| High school or less | 535 (17.8) | 179 (20.9) | .0411 |

| Post high school education | 2436 (80.9) | 669 (78.2) | |

| Missing | 39 (1.3) | 8 (0.9) | |

| Age at BMT in y | |||

| Median (IQR) | 43 (0-74) | 50 (1-72) | <.0001 |

| Follow-up from BMT to completing the survey in y | |||

| Median (range) | 9 (2-41) | 7 (2-37) | <.0001 |

| BMI, n (%) | |||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 97 (3.2) | 32 (3.7) | .3824 |

| Normal weight (18.5-<25 kg/m2) | 979 (32.5) | 260 (30.4) | |

| Overweight (25-<30 kg/m2) | 897 (29.8) | 243 (28.4) | |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 592 (19.7) | 138 (16.1) | |

| Unknown | 445 (14.8) | 183 (21.4) | |

| Primary diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| AML/MDS/ALL | 986 (32.8) | 237 (27.7) | <.0001 |

| CML | 282 (9.4) | 112 (13.1) | |

| HL/NHL | 978 (32.5) | 273 (31.9) | |

| PCD | 475 (15.8) | 213 (24.9) | |

| Other† | 289 (9.6) | 21 (2.4) | |

| Disease status at first BMT, n (%) | |||

| High risk | 1246 (41.4) | 483 (56.4) | <.0001 |

| Standard risk | 1371 (45.5) | 331 (38.7) | |

| Missing | 393 (13.1) | 42 (4.9) | |

| BMT type/cGvHD, n (%) | |||

| Autologous | 1443 (47.9) | 501 (58.5) | <.0001 |

| Allogeneic with cGvHD | 794 (26.4) | 246 (28.7) | |

| Allogeneic without cGvHD | 718 (23.8) | 104 (12.2) | |

| Allogeneic missing cGvHD | 55 (1.8) | 5 (0.6) | |

| Stem cell source, n (%) | |||

| Bone marrow/cord blood | 1034 (34.3) | 265 (31.0) | .0627 |

| Peripheral stem cells | 1975 (65.6) | 591 (69.0) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.03) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Conditioning intensity, n (%) | |||

| MAC | 2062 (68.5) | 611 (71.4) | <.0001 |

| RIC/NMA | 647 (21.5) | 114 (13.3) | |

| Missing | 301 (10.0) | 313 (15.3) | |

| Conditioning agents, n (%) | |||

| TBI | 1324 (44.0) | 424 (49.5) | .0040 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 1601 (53.2) | 416 (48.6) | .0177 |

| Nitrosoureas | 414 (13.8) | 87 (10.2) | .0058 |

| Etoposide | 1056 (35.1) | 279 (32.6) | .1765 |

| Busulfan | 363 (12.1) | 48 (5.6) | <.0001 |

| Cytarabine | 199 (6.6) | 54 (6.3) | .7519 |

| Melphalan | 782 (26.0) | 226 (26.4) | .8041 |

| Fludarabine | 519 (17.2) | 80 (9.4) | <.0001 |

| Chronic health conditions, n (%) | |||

| Grade 3 or 4 | 1694 (56.3) | 560 (65.4) | <.0001 |

| Mental health‡, n (%) | |||

| Not impaired | 2892 (96.1) | 779 (91.0) | <.0001 |

| Impaired | 118 (3.9) | 77 (9.0) | |

| Some pain from cancer, n (%) | |||

| No | 921 (30.6) | 264 (30.8) | .7931 |

| Yes | 2065 (68.6) | 579 (67.6) | |

| Missing | 24 (0.8) | 13 (1.5) | |

| Anxiety from cancer treatments, n (%) | |||

| Absent | 2821 (93.7) | 784 (91.6) | .7439 |

| Present | 139 (4.6) | 41 (4.8) | |

| Missing | 50 (1.7) | 31 (3.6) | |

| Ever smoke, n (%) | |||

| No | 1992 (66.2) | 438 (51.2) | <.0001 |

| Yes | 1005 (33.4) | 410 (47.9) | |

| Missing | 13 (0.4) | 8 (0.9) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Never smoker | 1992 (66.2) | 438 (51.2) | <.0001 |

| Former smoker | 863 (28.7) | 352 (41.1) | |

| Current smoker | 142 (4.7) | 58 (6.8) | |

| Missing | 13 (0.4) | 8 (0.9) | |

| Ever drink alcohol, n (%) | |||

| No | 1395 (46.3) | 268 (31.3) | <.0001 |

| Yes | 1577 (52.4) | 562 (65.7) | |

| Missing | 38 (1.3) | 26 (3.0) | |

| Heavy drinker, n (%) | |||

| No | 1464 (90.7) | 485 (82.5) | <.0001 |

| Yes | 113 (7.0) | 77 (13.1) | |

| Missing | 38 (2.3) | 26 (4.4) | |

| Vigorous physically active, n (%) | |||

| No | 1572 (52.2) | 403 (47.1) | .029 |

| Yes | 1421 (47.2) | 448 (52.3) | |

| Missing | 17 (0.6) | 5 (0.6) | |

| Levels of vigorous exercise (total metabolic equivalent h/wk-1) | |||

| 0 MET h/wk-1 | 1748 (58.1) | 578 (67.5) | <.0001 |

| 3 to <9 MET h/wk-1 | 964 (32.0) | 120 (14.0) | |

| ≥9 MET h/wk-1 | 281 (9.3) | 153 (17.9) | |

| Missing | 17 (0.6) | 5 (0.6) | |

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BMI, body mass index; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; IQR, interquartile range; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; NMA, nonmyeloablative; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; PCD, plasma cell dyscrasias; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning.

Bold indicates statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Race other includes multiracial (n = 94), American Indian (n = 13), and Pacific Islander (n = 2).

Primary diagnosis other includes severe aplastic anemia, other leukemia, and other.

Mental health is impaired if T-score ≥63 on any 2 of symptom scales of the 3 Brief Symptom Inventory-18 items subscales (depression, somatization, or anxiety).

Risky health behaviors

Smoking

Overall, 1415 participants (36.8%) were ever smokers; of these, 1215 (85.9%) were former smokers and 200 (14.1%) were current smokers. Supplemental Figure 2 shows the prevalence of tobacco products used by smokers. The median age at smoking initiation was 17 years (interquartile range, 10-57). As shown in Table 2, ever smokers were more likely to be male (59.7% vs 52.3%) and non-Hispanic White (79.8% vs 70.7%). Smokers were more likely to report ever drinking alcohol (70.2% vs 46.8%), but the prevalence of participants engaging in vigorous physical activity was comparable by smoking status (47.9% vs 48.8%).

Table 2.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of study participants by exposure of interest

| Variables of interest | Ever smoke |

Ever drink alcohol |

Vigorous physically active |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No n = 2430 (63.0%) |

Yes n = 1415 (36.8%) |

No n = 1663 (43.7%) |

Yes n = 2139 (56.3%) |

No n = 1975 (51.4%) |

Yes n = 1869 (48.6%) |

|

| Age at completing the survey in y | ||||||

| Median (range) | 54 (18-84) | 59 (18-83) | 57 (18-84) | 56 (18-83) | 60 (18-84) | 52 (18-80) |

| P value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||

| BMT era, n (%) | ||||||

| 1974-1989 | 211 (8.7) | 106 (7.4) | 103 (6.2) | 207 (9.7) | 109 (5.5) | 208 (11.3) |

| 1990-2004 | 1043 (42.9) | 614 (43.4) | 670 (40.3) | 957 (44.7) | 730 (37.0) | 931 (49.8) |

| 2005-2014 | 1176 (48.4) | 695 (49.1) | 890 (53.5) | 975 (45.6) | 1136 (57.5) | 730 (39.1) |

| P value | .4311 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Female | 1159 (47.7) | 570 (40.3) | 899 (54.1) | 813 (38.0) | 999 (50.6) | 726 (38.8) |

| Male | 1271 (52.3) | 845 (59.7) | 764 (45.9) | 1326 (62.0) | 976 (49.4) | 1143 (61.2) |

| P value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| African American | 126 (5.2) | 56 (4.0) | 118 (7.1) | 62 (2.9) | 124 (6.3) | 59 (3.2) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1719 (70.7) | 1129 (79.8) | 1118 (67.2) | 1729 (80.8) | 1430 (72.4) | 1419 (75.9) |

| Hispanic | 365 (15.0) | 140 (10.0) | 238 (14.3) | 227 (10.6) | 236 (11.9) | 265 (14.2) |

| Asian | 153 (6.3) | 48 (3.4) | 132 (8.0) | 69 (3.2) | 115 (5.8) | 86 (4.6) |

| Other∗ | 66 (2.7) | 41 (2.9) | 57 (3.4) | 50 (2.3) | 70 (3.5) | 38 (2.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.04) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) |

| P value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||

| Health insurance, n (%) | ||||||

| Not insured | 84 (3.5) | 48 (3.4) | 58 (3.5) | 74 (3.5) | 48 (2.4) | 83 (4.4) |

| Insured | 2325 (95.7) | 1344 (95.0) | 1604 (96.4) | 2061 (96.3) | 1925 (97.5) | 1743 (93.3) |

| Missing | 21 (0.9) | 23 (1.6) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.2) | 2 (1.1) | 43 (2.3) |

| P value | .1010 | .5632 | <.0001 | |||

| Annual household income, n (%) | ||||||

| <$19 999 | 659 (27.1) | 435 (30.7) | 571 (34.3) | 506 (23.7) | 665 (33.7) | 426 (22.8) |

| $20 000-$49 999 | 418 (17.2) | 310 (21.9) | 252 (15.2) | 460 (21.5) | 314 (15.9) | 413 (22.1) |

| >$50 000 | 1121 (46.1) | 552 (39.0) | 655 (39.4) | 1018 (47.6) | 812 (41.1) | 862 (46.1) |

| Missing | 232 (9.5) | 118 (8.3) | 185 (11.1) | 155 (7.2) | 184 (9.3) | 168 (9.0) |

| P value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||

| Educational status, n (%) | ||||||

| ≤High school or less | 383 (15.8) | 327 (23.1) | 353 (21.2) | 319 (14.9) | 419 (21.2) | 288 (15.4) |

| Post high school | 2011 (82.8) | 1083 (76.5) | 1283 (77.1) | 1807 (84.5) | 1532 (77.6) | 1564 (83.7) |

| Missing | 36 (1.5) | 5 (0.4) | 27 (1.6) | 13 (0.6) | 24 (1.2) | 17 (0.9) |

| P value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||

| Age at BMT in y | ||||||

| Median (range) | 42 (0-74) | 49 (0-74) | 44 (0-74) | 45 (0-74) | 49 (0-74) | 39 (0-72) |

| P value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||

| Follow-up since BMT to study start in y | ||||||

| Median (range) | 9 (2-41) | 8 (2-41) | 9 (3-41) | 8 (2-41) | 8 (3-41) | 9 (2-41) |

| P value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||

| BMI, n (%) | ||||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 93 (3.8) | 35 (2.5) | 75 (4.5) | 52 (2.4) | 68 (3.4) | 61 (3.3) |

| Normal weight (18.5 to <25 kg/m2) | 838 (34.5) | 394 (27.8) | 538 (32.3) | 693 (32.4) | 581 (29.4) | 652 (34.9) |

| Overweight (25 to <30 kg/m2) | 674 (27.7) | 464 (32.8) | 445 (29.8) | 691 (32.3) | 574 (29.1) | 560 (30.0) |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 429 (17.7) | 298 (21.1) | 356 (21.4) | 369 (17.2) | 456 (23.1) | 271 (14.5) |

| Unknown | 396 (16.3) | 224 (15.8) | 249 (15.0) | 52 (2.4) | 296 (15.0) | 325 (17.4) |

| P value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||

| Primary diagnosis†, n (%) | ||||||

| AML/MDS/ALL | 796 (32.8) | 420 (29.7) | 549 (33.0) | 653 (30.5) | 605 (30.6) | 612 (32.7) |

| CML | 245 (10.1) | 148 (10.5) | 153 (9.2) | 227 (10.6) | 157 (7.9) | 237 (12.7) |

| HL/NHL | 709 (29.2) | 531 (37.5) | 471 (28.3) | 766 (35.8) | 641 (32.5) | 601 (32.2) |

| PCD | 429 (17.6) | 257 (18.2) | 322 (19.4) | 356 (16.6) | 433 (21.9) | 248 (13.3) |

| Other† | 251 (10.3) | 59 (4.2) | 168 (10.1) | 137 (6.4) | 139 (7.0) | 171 (9.2) |

| P value | <.0001 | <.0001 | .3239 | |||

| Disease status at first BMT, n (%) | ||||||

| High risk | 1038 (42.7) | 681 (48.1) | 726 (43.7) | 976 (45.6) | 959 (48.6) | 758 (40.5) |

| Standard risk | 1073 (44.2) | 618 (43.7) | 743 (44.7) | 927 (43.3) | 842 (42.6) | 850 (45.5) |

| Missing | 319 (13.1) | 116 (8.2) | 194 (11.7) | 236 (11.0) | 174 (8.8) | 261 (14.0) |

| P value | <.0001 | .4661 | <.0001 | |||

| BMT type/cGvHD, n (%) | ||||||

| Autologous | 1157 (47.6) | 774 (54.7) | 796 (47.9) | 1123 (52.5) | 1030 (52.2) | 898 (48.0) |

| Allogeneic with cGvHD | 685 (28.2) | 349 (24.7) | 470 (28.3) | 545 (25.5) | 532 (26.9) | 504 (27.0) |

| Allogeneic without cGvHD | 555 (22.8) | 266 (18.8) | 366 (22.0) | 443 (20.7) | 374 (18.9) | 447 (23.9) |

| Allogeneic missing cGvHD | 33 (1.4) | 26 (1.8) | 31 (1.9) | 28 (1.3) | 39 (2.0) | 20 (1.1) |

| P value | <.0001 | .0256 | .0002 | |||

| Stem cell source, n (%) | ||||||

| Bone marrow/cord blood | 867 (35.7) | 427 (30.2) | 541 (32.5) | 721 (33.7) | 537 (27.2) | 760 (40.7) |

| Peripheral stem cells | 1562 (64.3) | 988 (69.8) | 1121 (67.4) | 1418 (66.3) | 1438 (72.8) | 1108 (59.3) |

| Missing | 1 (0.04) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.05) |

| P value | .0017 | .3965 | <.0001 | |||

| Conditioning intensity, n (%) | ||||||

| MAC | 1625 (66.9) | 1032 (72.9) | 1092 (65.7) | 1534 (71.7) | 1303 (66.0) | 1354 (72.4) |

| RIC/NMA | 498 (20.5) | 258 (18.2) | 381 (22.9) | 373 (17.4) | 449 (22.7) | 309 (16.5) |

| Missing | 307 (12.6) | 125 (8.8) | 190 (11.4) | 232 (10.9) | 223 (11.3) | 206 (11.0) |

| P value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||

| Conditioning regimen, n (%) | ||||||

| TBI | 1102 (45.3) | 635 (44.9) | 687 (41.3) | 1022 (47.8) | 766 (38.8) | 976 (52.2) |

| P value | .7760 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||

| Cyclophosphamide | 1249 (51.4) | 756 (53.4) | 815 (49.0) | 1181 (55.2) | 928 (47.0) | 1081 (57.8) |

| P value | .2246 | .0001 | <.0001 | |||

| Nitrosoureas | 289 (11.9) | 207 (14.6) | 191 (11.5) | 306 (14.3) | 272 (13.4) | 226 (12.1) |

| P value | .0147 | .0105 | .1210 | |||

| Etoposide | 812 (33.4) | 511 (36.1) | 530 (31.9) | 772 (36.1) | 609 (30.8) | 717 (38.4) |

| P value | .0895 | .0065 | <.0001 | |||

| Busulfan | 273 (11.2) | 135 (9.5) | 223 (13.4) | 182 (8.5) | 223 (11.3) | 184 (9.8) |

| P value | .1000 | <.0001 | .1452 | |||

| Cytarabine | 137 (5.6) | 114 (8.1) | 99 (6.0) | 151 (7.1) | 153 (7.7) | 98 (5.2) |

| P value | .0038 | .1722 | .0017 | |||

| Melphalan | 598 (24.6) | 404 (28.5) | 470 (28.3) | 527 (24.6) | 642 (32.5) | 358 (19.1) |

| P value | .0072 | .0117 | <.0001 | |||

| Fludarabine | 379 (15.6) | 216 (15.3) | 293 (17.6) | 302 (14.1) | 363 (18.4) | 234 (12.5) |

| P value | .7839 | .0032 | <.0001 | |||

| Chronic health conditions, n (%) | ||||||

| Grade 3 or 4 | 1394 (57.4) | 847 (59.9) | 1023 (61.5) | 1215 (56.8) | 1344 (68.0) | 899 (48.1) |

| P value | <.0001 | .0034 | <.0001 | |||

| Mental health‡, n (%) | ||||||

| Not impaired | 2317 (95.4) | 1325 (93.6) | 1579 (95.0) | 2019 (94.4) | 1858 (94.1) | 1782 (95.4) |

| Impaired | 113 (4.6) | 90 (6.4) | 84 (5.0) | 120 (5.6) | 117 (5.9) | 87 (4.6) |

| P value | .0222 | .4480 | .0794 | |||

| Some pain from cancer, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 791 (32.55) | 388 (27.4) | 454 (27.3) | 701 (32.8) | 419 (21.2) | 761 (40.7) |

| Yes | 1616 (66.5) | 1016 (71.8) | 1189 (71.5) | 1424 (66.6) | 1538 (77.9) | 1093 (58.5) |

| Missing | 23 (1.0) | 11 (0.8) | 20 (1.2) | 14 (0.6) | 18 (0.9) | 15 (0.8) |

| P value | .0030 | .0004 | <.0001 | |||

| Anxiety from cancer treatments, n (%) | ||||||

| Absent | 2280 (93.8) | 1308 (92.4) | 1559 (93.7) | 2025 (94.7) | 1849 (93.6) | 1740 (93.1) |

| Present | 104 (4.3) | 74 (5.2) | 85 (5.1) | 93 (4.3) | 108 (5.5) | 70 (3.7) |

| Missing | 46 (1.9) | 33 (2.3) | 19 (1.1) | 21 (1.0) | 18 (0.9) | 59 (3.2) |

| P value | .2507 | .4773 | .0170 | |||

| Vital status, n (%) | ||||||

| Deceased | 438 (18.0) | 410 (29.0) | 268 (16.1) | 562 (26.3) | 403 (20.4) | 448 (24.0) |

| Alive | 1992 (82.0) | 1005 (71.0) | 1395 (83.9) | 1577 (73.7) | 1572 (79.6) | 1421 (76.0) |

| P value | <.0001 | <.0001 | .0078 | |||

| Cause of death, n (%) | ||||||

| Nonrecurrence§ | 204 (46.6) | 209 (51.0) | 113 (42.2) | 288 (51.2) | 159 (39.4) | 256 (57.1) |

| Recurrence | 134 (30.6) | 112 (27.3) | 77 (28.7) | 162 (28.8) | 128 (31.8) | 118 (26.3) |

| Unknown | 95 (21.7) | 80 (19.5) | 78 (29.1) | 98 (17.4) | 113 (28.0) | 63 (14.1) |

| External | 5 (1.1) | 9 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (2.5) | 3 (0.7) | 11 (2.5) |

| P value | .3161 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||

| Ever smoke, n (%) | ||||||

| No | - | - | 1266 (73.1) | 1138 (53.2) | 1231 (62.3) | 1186 (63.5) |

| Yes | - | - | 394 (23.7) | 994 (46.5) | 735 (37.2) | 678 (36.3) |

| Missing | - | - | 3 (0.2) | 7 (0.3) | 9 (0.5) | 5 (0.3) |

| P value | - | <.0001 | .5071 | |||

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||

| Former smoker | - | 1215 (85.9) | 335 (85.0) | 854 (85.9) | 638 (86.8) | 575 (84.8) |

| Current smoker | - | 200 (14.1) | 59 (15.0) | 140 (14.1) | 97 (13.2) | 103 (15.2) |

| Age at smoking initiation | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | - | 17 (10-57) | 17 (10-48) | 17 (10-57) | 17 (10-57) | 17 (10-50) |

| Total y of smoking | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | - | 15 (1-57) | - | - | - | - |

| Ever drink alcohol, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 1266 (52.1) | 394 (27.8) | - | - | 1079 (54.6) | 575 (30.8) |

| Yes | 1138 (46.8) | 994 (70.2) | - | - | 883 (44.7) | 1251 (66.9) |

| Missing | 26 (1.1) | 27 (1.9) | - | - | 13 (0.7) | 43 (2.3) |

| P value | <.0001 | - | <.0001 | |||

| Heavy drinker, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 1058 (93.0) | 884 (88.9) | - | 1949 (91.1) | 839 (95.0) | 1105 (88.3) |

| Yes | 80 (7.0) | 110 (11.1) | - | 190 (8.9) | 44 (5.0) | 146 (11.7) |

| P value | .0011 | - | <.0001 | |||

| Vigorous physical activity, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 1231 (50.7) | 735 (51.9) | 651 (39.1) | 626 (29.3) | - | - |

| Yes | 1186 (48.8) | 678 (47.9) | 575 (34.6) | 1251 (58.5) | - | - |

| Missing | 13 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) | 437 (26.3) | 262 (12.2) | - | - |

| P value | .1362 | - | <.0001 | |||

| Levels of vigorous exercise (total metabolic equivalent h/wk-1) | ||||||

| 0 MET h/wk-1 | 1419 (58.4) | 898 (63.5) | 1157 (69.6) | 1134 (53.0) | 1975 (100.0) | 351 (18.8) |

| 3 to <9 MET h/wk-1 | 736 (30.3) | 343 (24.2) | 410 (24.6) | 668 (31.2) | - | 1084 (58.0) |

| ≥ 9 MET h/wk-1 | 262 (10.8) | 172 (12.2) | 87 (5.2) | 332 (15.5) | - | 434 (23.2) |

| Missing | 13 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) | 9 (0.5) | 5 (0.2) | - | - |

| P value | .0001 | <.0001 | - | |||

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BMI, body mass index; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; IQR, interquartile range; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; NMA, nonmyeloablative; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; PCD, plasma cell dyscrasias; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning; -, data are not relevant or applicable.

Bold indicates statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Race other includes multiracial (n = 93), American Indian (n = 12), and Pacific Island (n = 2).

Primary diagnosis other includes severe aplastic anemia, other leukemia, and other.

Mental health is impaired outcome (T-score ≥63) in any of the 3 Brief Symptoms Inventory-18 items subscales (depression, somatization, or anxiety).

Nonrecurrence cause of death includes SMN (n = 149), cardiac (n = 86), infection (n = 84), pulmonary (n = 29), renal (n = 22), stroke (n = 12), neurologic (n = 10), other (n = 8), hepatic (n = 6), hemorrhage (n = 5), and VTE (n = 2).

Alcohol consumption

Overall, 2139 participants reported consuming alcohol (56.3%); 190 were heavy drinkers (8.9%). As shown in Table 2, participants who reported consuming alcohol were more likely to be male (62% vs 45.9%) and non-Hispanic White (80.8% vs 67.2%). In addition, those reporting alcohol consumption were more likely to be smokers (46.5% vs 23.7%) and more likely to practice vigorous physical activity (58.5% vs 34.6%).

Vigorous physical activity

Overall, 1975 participants reported not engaging in vigorous physical activity (51.4%). Participants not engaging in vigorous physical activity were more likely to be female (50.6% vs 38.8%), report cancer-related pain (77.9% vs 58.5%), and have grade 3 or 4 chronic health conditions (68.0% vs 48.1%) compared with individuals who reported vigorous physical activity. Furthermore, those not engaging in vigorous physical activity were less likely to report consuming alcohol (44.7% vs 54.6%) (Table 2).

Mortality after completing BMTSS survey

Smoking

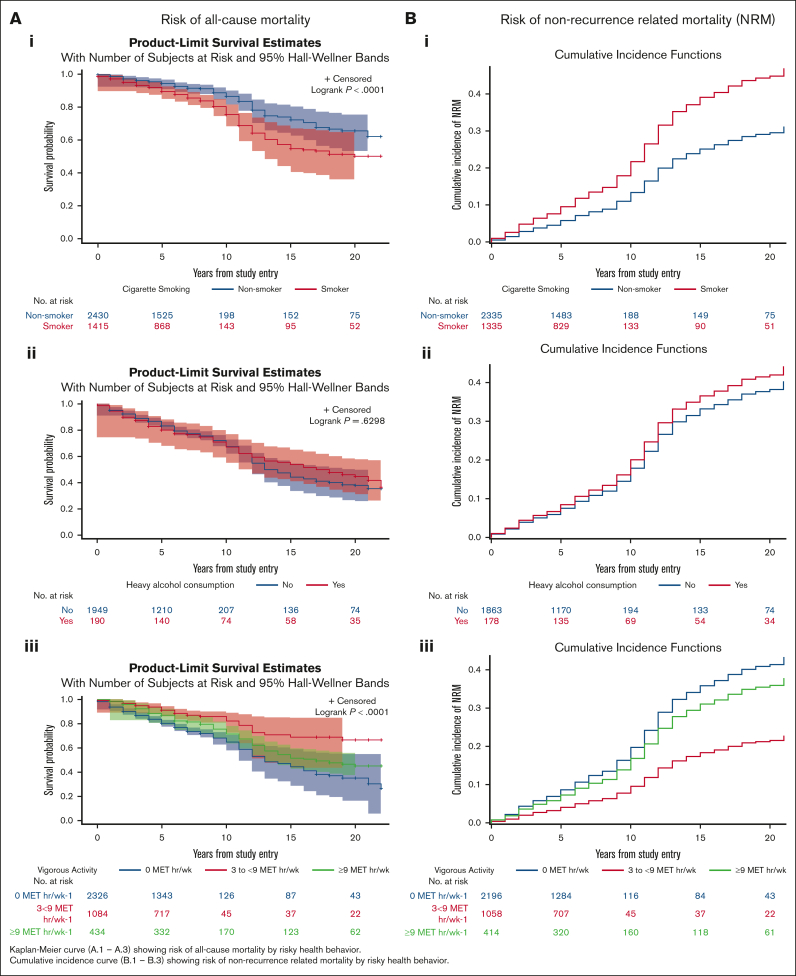

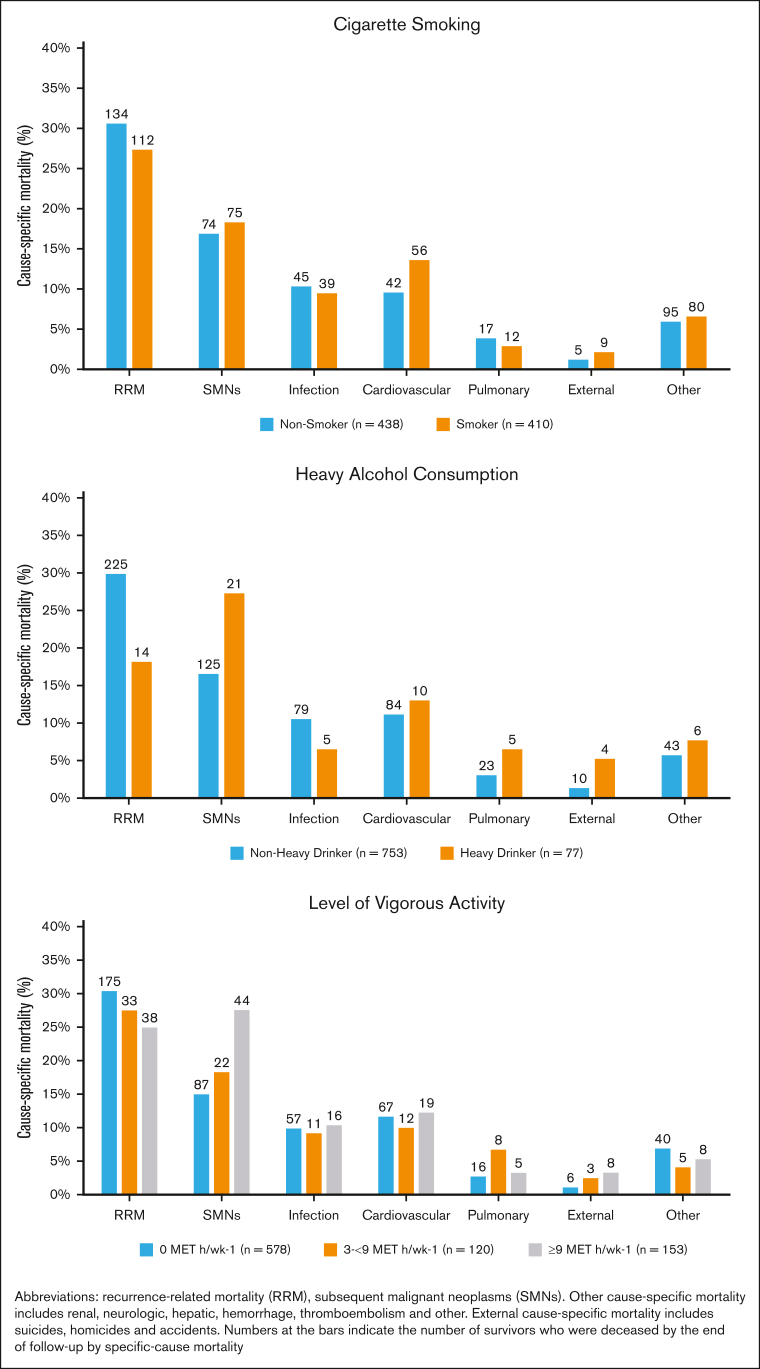

Smokers had inferior survival probability (Figure 1Ai) and a higher cumulative incidence of NRM (Figure 1Bi) compared with nonsmokers. As shown in Table 3, multivariable analysis revealed significantly higher hazards of all-cause mortality among ever smokers (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.5; reference, never smokers). Furthermore, all-cause mortality was higher among former smokers (aHR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.5) and current smokers (aHR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2-2.5) than nonsmokers. The adjusted hazard of NRM was 1.3-fold higher for former smokers (aHR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.8) and 1.6-fold higher for current smokers (aHR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.0-2.7) than for nonsmokers (Table 3). Figure 2 shows the common causes of death among smokers (RRM, 27.3%; SMNs, 18.3%; cardiovascular disease, 14%; and pulmonary disease, 3%). The specific SMN-related deaths among smokers were more likely because of smoking-related malignancies (76% vs 24%), such as lung, bladder, esophagus, stomach, hypopharynx, tongue, leukemia, colon, rectum, kidney, liver, and pancreas. There was a significant interaction (P = .019) between TBI and smoking, such that smokers who had received TBI had a 1.4-fold higher hazard of all-cause mortality (95% CI, 1.1-1.9), whereas smokers who had not received TBI did not demonstrate a higher hazard of all-cause mortality (HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.8-1.4). As shown in Table 4, the never smokers, former smokers, and current smokers were at a 4.3-fold, 4.5-fold, and 8.7-fold higher risk of death than the age- and sex-matched general population, respectively. The corresponding excess deaths per 1000 person-years were 25.5, 36.9, and 39.4, respectively.

Figure 1.

Risk of mortality by risky health behaviors. (A) Risk of all-cause mortality after blood or marrow transplantation (BMT). (B) Risk of non-recurrence mortality after BMT.

Table 3.

Risky health behaviors and hazard of subsequent all-cause and nonrecurrence–related late mortality

| Variables of interest | Crude HR (95% CI) |

aHR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | All-cause mortality | Nonrecurrence-related mortality | |

| Ever smoke∗ | |||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.5 (1.4-1.8) | 1.2 (1.1-1.5) | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) |

| Smoking status∗ | |||

| Non-smoker | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Former smoker | 1.6 (1.4-1.8) | 1.2 (1.1-1.5) | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) |

| Current smoker | 1.4 (1.1-1.9) | 1.7 (1.2-2.5) | 1.6 (1.0-2.7) |

| Ever drink alcohol† | |||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) |

| Heavy drinker† | |||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 0.9 (0.7-1.2) | 1.4 (1.0-1.8) | 1.4 (1.0-2.0) |

| Vigorous physical activity for at least 10 min at a time§ | |||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| No | 1.5 (1.3-1.7) | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | 1.2 (1.0-1.6) |

| Levels of vigorous exercise (total metabolic equivalent h/wk-1)§ | |||

| ≥ 9 MET h/wk-1 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 3 to <9 MET h/wk-1 | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | 0.7 (0.6-0.1) |

| 0 MET h/wk-1 | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) | 1.3 (1.1-1.7) | 1.3 (1.0-1.7) |

Bolded values indicate statistical significance (CI does not include 1).

Adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, BMT era, time from BMT to study entry, age at BMT, primary diagnosis, stem cell source, disease status at BMT, BMT type, cGvHD, conditioning intensity, TBI, cyclophosphamide, nitrosoureas, busulfan, fludarabine, household income, educational status, chronic health conditions, mental health, physical activity status, alcohol consumption (ever), and total years of smoking. Survivors with missing smoking status were excluded from this analysis.

Adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, BMT era, time from BMT to study entry, stem cell source, age at BMT, primary diagnosis, disease status at BMT, BMT type, cGvHD, conditioning intensity, TBI, cyclophosphamide, nitrosoureas, busulfan, fludarabine, household income, chronic health conditions, educational status, mental health, physical activity status, and smoking status (ever). Survivors with missing alcohol consumption status were missing from this analysis.

Adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, BMT era, time from BMT to study entry, stem cell source, age at BMT, primary diagnosis, disease status at BMT, BMT type, cGvHD, conditioning intensity, TBI, cyclophosphamide, nitrosoureas, busulfan, fludarabine, household income, chronic health condition, educational status, mental health, anxiety from cancer treatment, smoking status (ever), and alcohol consumption (ever). Survivors with missing physical activity status were excluded from this analysis.

Figure 2.

Survivors’ risk of cause-specific mortality by risky health behaviors.

Table 4.

Study participants’ age- and sex-standardized mortality ratio compared with US general population and excess deaths per 1000 person-years

| SMR (95% CI) | Excess deaths per 1000 person-y (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking status | ||

| Never | 4.3 (3.8-4.7) | 25.5 (22-29) |

| Former | 4.5 (4.0-5.0) | 36.9 (32-42) |

| Current | 8.7 (6.4-10.9) | 39.4 (28-51) |

| Alcohol consumption status | ||

| Nonheavy drinker | 4.0 (3.6-4.3) | 30.7 (28-34) |

| Heavy drinker | 13.0 (10.0-15.9) | 53.5 (40-67) |

| Levels of vigorous exercise (total metabolic equivalent h/wk-1) | ||

| 0 MET h/wk-1 | 4.9 (4.4-5.2) | 35.4 (32-39) |

| 3 to <9 MET h/wk-1 | 2.4 (1.9-2.8) | 11.0 (7-15) |

| ≥9 MET h/wk-1 | 6.7 (5.7-7.9) | 30.4 (24-36) |

SMR, standardized mortality ratio.

Alcohol consumption

We did not observe a significant difference in all-cause mortality (aHR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.3) or NRM (aHR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9-1.4) between patients who reported ever drinking alcohol and those who did not (Table 3). Figure 1Aii,Bii show that heavy drinkers had a lower risk of all-cause mortality and NRM after BMT than nonheavy drinkers. However, after adjusting for time from BMT to study entry, age at BMT, sex, race/ethnicity, BMT era, stem cell source, primary diagnosis, disease status at BMT, BMT type, cGvHD, conditioning intensity, TBI, cyclophosphamide, nitrosoureas, busulfan, fludarabine, household income, chronic health conditions, educational status, mental health, physical activity status, and smoking status, a significantly higher hazard of all-cause mortality was observed among heavy drinkers (aHR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0-1.8; reference, nonheavy drinkers). In addition, heavy alcohol drinkers were at increased risk of NRM compared with nonheavy drinkers (aHR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0-2.0) (Table 3). The most common causes of death among heavy drinkers included disease recurrence (18.2%), SMNs (27.3%), cardiovascular disease (13%), and infection (6.5%) (Figure 2). Alcohol consumption did not show any interaction with TBI in increasing the hazard of all-cause mortality (ever drinker: P = .627; heavy drinker: P = .136). As shown in Table 4, the nonheavy and heavy drinkers were at a 4.0-fold and a 13.0-fold higher risk of death than the age- and sex-matched general population, respectively. The corresponding excess deaths per 1000 person-years were 30.7 and 53.5, respectively.

Vigorous physical activity

Figure 1Aiii,Biii show that survivors who exercised 3 to <9 MET hour/week-1 had the greatest survival probability (all-cause mortality and NRM) after BMT compared with the other groups. Increased hazard of all-cause mortality was observed among those not engaging in vigorous physical activity (HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.4; reference, reported vigorous physical activity). Survivors who exercised 0 MET hour/week-1 were at a higher risk of all-cause mortality than individuals who exercised ≥9 MET hour/week-1 (aHR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1-1.7). Individuals who exercised 3 to <9 MET hour/week-1 were at 30% lower risk of all-cause mortality than those who exercised ≥9 MET hour/week-1 (aHR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5-1.0) (Table 3). Individuals who exercised 0 MET hour/week-1 were at higher risk of NRM (aHR=1.3, 95%CI=1.0-1.7) than individuals who exercised ≥9 MET hour/week-1. Individuals who exercised 3 to <9 MET hour/week-1 were at lower risk of NRM than those who exercised ≥9 MET hour/week-1 (aHR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.6-1.0). As shown in Figure 2, the causes of death did not differ by level of vigorous exercise, with the exception of SMN-related deaths, in which the prevalence was highest among those with the highest level of activity. However, the adjusted hazards of SMN-related deaths revealed that survivors who exercised 0 MET hour/week-1 had a higher risk of SMN-related deaths than survivors who exercised ≥9 MET hour/week-1 (aHR, 1.9; 95% CI, 0.4-1.2) (supplemental Table 3). Vigorous physical activity did not demonstrate a significant interaction with TBI in increasing the hazard of all-cause mortality (P = .627). As shown in Table 4, survivors who practiced 0 MET hour/week-1, 3 to >9 MET hour/week-1, and ≥9 MET hour/week-1 were at a 4.9-fold, 2.4-fold, and 6.7-fold higher risk of death than the age- and sex-matched general population, respectively. The corresponding excess deaths per 1000 person-years were 35.4, 11.0, and 30.4, respectively.

Risky health behaviors and late mortality by clinical/demographic characteristics

The association between risky health behaviors of interest and all-cause late mortality did not differ based on sex. Time from BMT to study participation, age at BMT, and BMT type were not effect-modifiers (supplemental Table 2). Analyses stratified by age at survey completion (<56 years; ≥56 years) revealed that the magnitude of association between risky health behaviors and late mortality did not differ by age at study participation, with the exception that the association between lack of physical activity and mortality was higher in the younger age group (supplemental Figures 3-5).

Risk health behaviors in clusters

Supplemental Figure 6 shows the numbers of participants practicing risky health behaviors in clusters. The hazard of all-cause mortality and NRM increased with the number of risk behaviors. The hazard of all-cause mortality (aHR, 3.7; 95% CI, 1.8-7.6; reference, no risky behavior) and NRM (aHR, 2.9; 95% CI, 0.8-9.5; reference, no risky behavior) was highest among participants who reported practicing all 3 risky behaviors (smoking, heavy alcohol drinking, and lack of physical activity) compared with those practicing no risky behaviors (supplemental Table 4).

Discussion

This analysis of a large cohort of adult BMT survivors followed for a median of 15 years from BMT, including 5 years after completing a comprehensive health-related survey, indicates that risky health behaviors were associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality. In particular, smoking (current or former), heavy drinking, and not engaging in vigorous physical activity increased the risk of NRM.

Although former smokers were at a 20% higher hazard of all-cause mortality, current smokers were at 70% higher risk. Furthermore, current smokers were at a 60% higher risk of NRM than nonsmokers. The most common causes of nonrecurrence-related death were subsequent malignancies and cardiovascular disease. Our findings are consistent with previous studies in the general population demonstrating a definitive association between smoking and twofold to threefold higher hazards of all-cause mortality.37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 Epidemiologic studies strongly support the association between cigarette smoking and cardiovascular events and mortality.46, 47, 48 Even low-tar cigarette smoking is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality in comparison with not smoking.49,50 Cigarette smoking causes endothelial dysfunction, resulting in thrombotic lesions.51 However, given the high risk of late mortality among BMT recipients,22,52 the addition of smoking, especially in the setting of TBI increases the risk even further.

Heavy alcohol consumption was associated with a 40% higher hazard of all-cause mortality and NRM. Common causes of nonrecurrence-related mortality included subsequent malignancies and cardiovascular disease. Our findings are consistent with several previous studies among cancer and noncancer populations.53, 54, 55, 56 Observational studies have consistently shown a higher risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in people with high level of alcohol consumption in the general population.57,58 High doses of alcohol are associated with the development of hypertension, coronary and peripheral atherosclerosis, changes in lipid profile, and an increased risk of stroke.59,60

Physical inactivity increases the risk of coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and breast and colon cancers, resulting in a shortened life expectancy.61 We found that lack of vigorous exercise among BMT survivors was associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality and NRM. Survivors who did not exercise vigorously had a 20% higher risk of all-cause mortality and NRM than those who did. Previous studies in the general population report higher hazards of all-cause mortality among participants who are inactive.62,63 A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study suggested that vigorous exercise is associated with a lower risk of mortality in adult survivors of childhood cancer.64 When examining the intensity of vigorous activity, we found a 30% higher hazard of all-cause mortality and NRM among participants who exercised 0 MET hour/week-1 than those who exercised ≥9 MET hour/week-1. Interestingly, the hazard of all-cause mortality and NRM among participants who reported 3 to >9 MET hour/week-1 vigorous physical activity was lower than in individuals who exercised ≥9 MET hour/week-1. Previous studies suggest that exercise dose-response associations with mortality are not necessarily linear.63,65 Several studies have demonstrated a U-shaped or a reverse J-shaped relationship between physical activity and mortality (ie, the mortality risk reduction is attenuated or eliminated at a high threshold of physical activity).66 Long-term excessive exercise may induce pathologic structural remodeling of the heart and large arteries. Emerging data suggest that excessive exercise can cause transient acute volume overload of the atria and right ventricle, with transient reductions in right ventricular ejection fraction and elevations of cardiac biomarkers, all of which return to normal within 1 week. Over months to years of repetitive injury, this process, in some individuals, may lead to patchy myocardial fibrosis, particularly in the atria, interventricular septum, and right ventricle, creating a substrate for atrial and ventricular arrhythmias. Additionally, long-term excessive sustained exercise may be associated with coronary artery calcification, diastolic dysfunction, and large-artery wall stiffening.67

From a public health perspective, addressing risky health behaviors and promoting positive health behaviors is important because they are potentially modifiable.68 Previous studies in the general population report that smoking, alcohol-related disorders, and physical inactivity can directly affect health–related quality of life.69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74 The association between these potentially modifiable factors and late mortality offers opportunities for development of interventions to improve both the quality and quantity of life after BMT.

This study needs to be placed in the context of its limitations. Our analysis relied on self-reported measures, which are subject to reporting and recall bias. There is a potential for survival bias because the time from BMT to survey completion varied between survivors. We adjusted for time from BMT to survey completion to address this concern, and the magnitude of the association between risky behaviors and mortality did not differ when stratified by time from BMT to survey completion. There is a potential for behavior change between completion of the survey and last follow-up or death. We attempted to address this by using the time from survey to death or end of follow-up as the time axis in the analysis. These limitations notwithstanding, to our knowledge, this is the first large, multi-institutional study with mature follow-up that evaluated risky health behaviors and their association with late mortality. Investigating these risky health behaviors could inform the development of interventions to reduce late mortality after BMT. It also highlights the importance of educating survivors and their health care providers about their risks and the need for long-term surveillance.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA078938 and U01 CA213140; S.B.) and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (R6502-16; S.B.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.B., S.J.F., D.J.W., S.H.A., and R.B. contributed to study conception and design; S.B., L.H., E.R., N.B, A.B., H.S.T., F.L.W. and Q.M. collected and assembled the data; N.B. and S.B. analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript; S.B., L.H., W.L., E.R., and N.B. provided administrative, technical, or material support; S.B. and S.H.A. supervised the study; and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Data will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Smita Bhatia (smitabhatia@uabmc.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.D’Souza A, Fretham C, Lee SJ, et al. Current use of and trends in hematopoietic cell transplantation in the United States. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26(8):e177–e182. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niederwieser D, Baldomero H, Szer J, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation activity worldwide in 2012 and a SWOT analysis of the Worldwide Network for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group including the global survey. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51(6):778–785. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majhail NS. Long-term complications after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2017;10(4):220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gangaraju R, Chen Y, Hageman L, et al. Venous thromboembolism in autologous blood or marrow transplantation survivors: a report from the blood or marrow transplant survivor study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(11):2261–2266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora M, Chen Y, Hageman L, et al. Morbidity burden in survivors of multiple myeloma who underwent autologous transplantation: a bone marrow transplantation survivor study. Cancer. 2020;126(14):3322–3329. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharafeldin N, Bosworth A, Patel SK, et al. Cognitive functioning after hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematologic malignancy: results from a prospective longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(5):463–475. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker KS, Ness KK, Steinberger J, et al. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular events in survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the bone marrow transplantation survivor study. Blood. 2007;109(4):1765–1772. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-022335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun CL, Francisco L, Kawashima T, et al. Prevalence and predictors of chronic health conditions after hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2010;116(17):3129–3139. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-229369. quiz 3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun CL, Kersey JH, Francisco L, et al. Burden of morbidity in 10+ year survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation: report from the bone marrow transplantation survivor study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(7):1073–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armenian SH, Sun CL, Shannon T, et al. Incidence and predictors of congestive heart failure after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;118(23):6023–6029. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-358226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arora M, Sun CL, Ness KK, et al. Physiologic frailty in nonelderly hematopoietic cell transplantation patients: results from the bone marrow transplant survivor study. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(10):1277–1286. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armenian SH, Sun CL, Mills G, et al. Predictors of late cardiovascular complications in survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(8):1138–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangaraju R, Chen Y, Hageman L, et al. Late-occurring venous thromboembolism in allogeneic blood or marrow transplant survivors: a BMTSS-HiGHS2 risk model. Blood Adv. 2021;5(20):4102–4111. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonald AM, Chen Y, Wu J, et al. Total body irradiation and risk of breast cancer after blood or marrow transplantation: a blood or marrow transplantation survivor study report. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(25):2872–2882. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong FL, Teh JB, Atencio L, et al. Conditional survival, cause-specific mortality, and risk factors of late mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(11):1153–1161. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmqvist AS, Chen Y, Wu J, et al. Assessment of late mortality risk after allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation performed in childhood. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12) doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatia S, Francisco L, Carter A, et al. Late mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation and functional status of long-term survivors: report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2007;110(10):3784–3792. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duell T, van Lint MT, Ljungman P, et al. Health and functional status of long-term survivors of bone marrow transplantation. EBMT Working Party on Late Effects and EULEP Study Group on Late Effects. European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(3):184–192. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-3-199702010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Socie G, Stone JV, Wingard JR, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Late effects Working Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(1):14–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907013410103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pond GR, Lipton JH, Messner HA. Long-term survival after blood and marrow transplantation: comparison with an age- and gender-matched normative population. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(4):422–429. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.11.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin PJ, Counts GW, Jr., Appelbaum FR, et al. Life expectancy in patients surviving more than 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(6):1011–1016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhatia S, Dai C, Landier W, et al. Trends in late mortality and life expectancy after allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation over 4 decades: a blood or marrow transplant survivor study report. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(11):1626–1634. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shopland DR. Tobacco use and its contribution to early cancer mortality with a special emphasis on cigarette smoking. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103(Suppl 8):131–142. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s8131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradshaw PT, Ibrahim JG, Khankari N, et al. Post-diagnosis physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis: the Long Island Breast Cancer Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145(3):735–742. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2966-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, Chan JM. Physical activity and survival after prostate cancer diagnosis in the health professionals follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(6):726–732. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell PT, Patel AV, Newton CC, Jacobs EJ, Gapstur SM. Associations of recreational physical activity and leisure time spent sitting with colorectal cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(7):876–885. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasco AJ, Secretan MB, Straif K. Tobacco smoking and cancer: a brief review of recent epidemiological evidence. Lung Cancer. 2004;45(Suppl 2):S3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.07.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(3):580–593. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 3) 2013. Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Recklitis CJ, Blackmon JE, Chang G. Validity of the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) for identifying depression and anxiety in young adult cancer survivors: comparison with a structured clinical diagnostic interview. Psychol Assess. 2017;29(10):1189–1200. doi: 10.1037/pas0000427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merport A, Recklitis CJ. Does the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 case rule apply in adult survivors of childhood cancer? Comparison with the Symptom Checklist-90. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37(6):650–659. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National death index; 2022. National Center for Health Statistics.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ndi/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. 2011 Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(8):1575–1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majhail NS, Nayyar S, Santibañez MEB, Murphy EA, Denzen EM. Racial disparities in hematopoietic cell transplantation in the United States. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47(11):1385–1390. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1997;(99):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Center for Health Statistics . Health data interactive; 2022. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/life_tables.htm [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jee SH, Samet JM, Ohrr H, Kim JH, Kim IS. Smoking and cancer risk in Korean men and women. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15(4):341–348. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000027481.48153.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, Colditz GA. Smoking and smoking cessation in relation to mortality in women. JAMA. 2008;299(17):2037–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.17.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, et al. 50-year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):351–364. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Estimates of global mortality attributable to smoking in 2000. Lancet. 2003;362(9387):847–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones LW, Liu Q, Armstrong GT, et al. Exercise and risk of major cardiovascular events in adult survivors of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(32):3643–3650. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.7511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1885–1906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakata R, McGale P, Grant EJ, Ozasa K, Peto R, Darby SC. Impact of smoking on mortality and life expectancy in Japanese smokers: a prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):341–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banks E, Joshy G, Weber MF, et al. Tobacco smoking and all-cause mortality in a large Australian cohort study: findings from a mature epidemic with current low smoking prevalence. BMC Med. 2015;13:38. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0281-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammond E, Horn D. Smoking and death rates: report on forty-four months of follow-up of 187,783 men. 2. Death rates by cause. J Am Med Assoc. 1958;166(11):1294–1308. doi: 10.1001/jama.1958.02990110030007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doll R, Peto R. Mortality in relation to smoking: 20 years' observations on male British doctors. Br Med J. 1976;2(6051):1525–1536. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6051.1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willett WC, Green A, Stampfer MJ, et al. Relative and absolute excess risks of coronary heart disease among women who smoke cigarettes. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(21):1303–1309. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711193172102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Negri E, Franzosi MG, La Vecchia C, Santoro L, Nobili A, Tognoni G. Tar yield of cigarettes and risk of acute myocardial infarction. GISSI-EFRIM Investigators. BMJ. 1993;306(6892):1567–1570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6892.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolinder G, Alfredsson L, Englund A, de Faire U. Smokeless tobacco use and increased cardiovascular mortality among Swedish construction workers. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(3):399–404. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(10):1731–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhatia S, Dai C, Landier W, et al. Trends in late mortality and life expectancy after autologous blood or marrow transplantation over three decades: a BMTSS report. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(18):1991–2003. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xi B, Veeranki SP, Zhao M, Ma C, Yan Y, Mi J. Relationship of alcohol consumption to all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer-related mortality in U.S. adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(8):913–922. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, Bagnardi V, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G. Alcohol dosing and total mortality in men and women: an updated meta-analysis of 34 prospective studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(22):2437–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.22.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ronksley PE, Brien SE, Turner BJ, Mukamal KJ, Ghali WA. Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d671. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Behrens G, Leitzmann MF, Sandin S, et al. The association between alcohol consumption and mortality: the Swedish women's lifestyle and health study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(2):81–90. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9545-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Day E, Rudd JHF. Alcohol use disorders and the heart. Addiction. 2019;114(9):1670–1678. doi: 10.1111/add.14703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goel S, Sharma A, Garg A. Effect of alcohol consumption on cardiovascular health. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018;20(4):19. doi: 10.1007/s11886-018-0962-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fernandez-Sola J. Cardiovascular risks and benefits of moderate and heavy alcohol consumption. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(10):576–587. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O'Keefe EL, DiNicolantonio JJ, O'Keefe JH, Lavie CJ. Alcohol and CV health: Jekyll and Hyde J-curves. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;61(1):68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee IM, Sesso HD, Oguma Y, Paffenbarger RS., Jr. The "weekend warrior" and risk of mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(7):636–641. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O'Donovan G, Lee IM, Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Association of "Weekend Warrior" and other leisure time physical activity patterns with risks for all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):335–342. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scott JM, Li N, Liu Q, et al. Association of exercise with mortality in adult survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(10):1352–1358. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arem H, Moore SC, Patel A, et al. Leisure time physical activity and mortality: a detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):959–967. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee DH, Rezende LFM, Ferrari G, et al. Physical activity and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: assessing the impact of reverse causation and measurement error in two large prospective cohorts. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36(3):275–285. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00707-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O'Keefe JH, Patil HR, Lavie CJ, Magalski A, Vogel RA, McCullough PA. Potential adverse cardiovascular effects from excessive endurance exercise. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(6):587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Filippidis FT, Agaku IT, Vardavas CI. Geographic variation and socio-demographic determinants of the co-occurrence of risky health behaviours in 27 European Union member states. J Public Health. 2016;38(2):e13–20. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cui Y, Forget EL, Torabi M, Oguzoglu U, Ohinmaa A, Zhu Y. Health-related quality of life and economic burden to smoking behaviour among Canadians. Can J Public Health. 2019;110(5):533–541. doi: 10.17269/s41997-019-00244-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heikkinen H, Jallinoja P, Saarni SI, Patja K. The impact of smoking on health-related and overall quality of life: a general population survey in Finland. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(7):1199–1207. doi: 10.1080/14622200802163142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tillmann M, Silcock J. A comparison of smokers' and ex-smokers' health-related quality of life. J Public Health Med. 1997;19(3):268–273. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Srivastava S, Bhatia MS. Quality of life as an outcome measure in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):41–46. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.123617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bize R, Johnson JA, Plotnikoff RC. Physical activity level and health-related quality of life in the general adult population: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45(6):401–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gillison FB, Skevington SM, Sato A, Standage M, Evangelidou S. The effects of exercise interventions on quality of life in clinical and healthy populations; a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(9):1700–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.