Abstract

Environmental perturbations are encountered by microorganisms regularly and will require metabolic adaptations to ensure an organism can survive in the newly presenting conditions. In order to study the mechanisms of metabolic adaptation in such conditions, various experimental and computational approaches have been used. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are one of the most powerful approaches to study metabolism, providing a platform to study the systems level adaptations of an organism to different environments which could otherwise be infeasible experimentally. In this review, we are describing the application of GEMs in understanding how microbes reprogram their metabolic system as a result of environmental variation. In particular, we provide the details of metabolic model reconstruction approaches, various algorithms and tools for model simulation, consequences of genetic perturbations, integration of ‘-omics’ datasets for creating context-specific models and their application in studying metabolic adaptation due to the change in environmental conditions.

Keywords: genome-scale metabolic models, metabolic adaptation, environmental variation, ‘-omics’ data, tools, simulation, emerging human pathogens, host switching

INTRODUCTION

Since the first genome-scale metabolic reconstruction in 1999 for Haemophilus influenzae RD [1], such models have become a major approach to studying the metabolism of an organism at the systems level. The metabolic models of thousands of bacteria, and hundreds of archaea and eukaryotes have been reconstructed [2]. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) computationally describe the entire set of metabolic reactions existing within an organism [1, 3, 4] and are built by integrating genome annotation and experimental data. Genome annotation quality is therefore paramount in metabolic reconstructions.

The applications for metabolic reconstructions of microbial species are wide-reaching within biology, including but not limited to the design of metabolic engineering approaches [5–7], the modeling of microbial communities [3, 8–11], identification of potential drug targets through in silico gene knockout experiments [12–14], studying metabolic adaptations contributing to virulence and pathogenesis [15, 16] and exploring how microorganisms reprogram their metabolism in response to environmental variation [17–19].

During their lifestyle as reproducing cells, dormant cells, commensals or pathogens, microbes encounter multiple different environmental perturbations, both externally and within a host niche, to which microorganisms must adapt accordingly. Such perturbations are often difficult to study in a laboratory, both technically and financially.

The ever-increasing availability of ‘-omics’ data for microbial species has allowed the integration of such data with GEMs to create context-specific metabolic reconstructions [20–22], detailing the metabolic adaptations occurring in an organism between two separate conditions. Analysis of such context-specific models can generate predictions of how microbes adapt their metabolism in response to environmental perturbations including nutrient limitation, pH, temperature, osmotic stress and oxidative stress. Such predictions can identify genes or pathways of interest to study further in vitro with the aim of identifying just how microbes alter the way they metabolize and respire in order to best survive, colonize a host, induce virulence factors, evade the host’s immune system or produce products of biotechnological interest.

Genome sequencing and annotation

Since the late 2000s, high-throughput sequencing technologies have become more frequently applied in the biology field and have been continually developing. Since first-generation Sanger DNA sequencing technologies [23–25], next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms have subsequently been developed with reduced sequencing costs and improved speed and quality. These platforms commonly work on the principles of creating template short DNA fragments (~600bp) followed by clonal amplification before sequencing and assembly or alignment to reference genomes [26], such as Illumina technologies [27]. The genome of most of the model organisms was sequenced using NGS technologies. Third-generation sequencing, a further development in sequencing technologies, includes the incorporation of fluorescently-labelled nucleotides before real-time sequencing of single molecules [26], such as PacBio sequencing [28]. The major challenge, however, in the NGS field is bioinformatics data analysis, for instance genome assembly and annotation. Whole genome annotation is typically a combination of homology-based methods, where the annotation is assigned to new DNA sequences based on similarity with known genes, followed by gene prediction methods, which are based on intrinsic DNA sequence signatures [29]. For prokaryotic species, annotation tools include EasyGene [30], GeneMark [31], the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) [32], DFAST [33], MicrobeAnnotator [34], Prokka [35] and SNAP [36].

DFAST, MicrobeAnnotator and Prokka all utilize homology-based annotation pipelines whereby reference databases or genomes are used to identify sequence similarity facilitating the prediction of protein coding genes [33–35]. In contrast, EasyGene, GeneMark and SNAP employ intrinsic, or ab initio, gene prediction methods [30, 31, 36]. PGAP is unique in that it employs both homology-based and intrinsic gene prediction methods via the gene finding program GeneMarkS [32, 37]. All of the tools described above utilize a hidden Markov model as part of the annotation pipeline, with the exception of PGAP which instead employs a hidden semi-Markov model [30–36]. The outputs provided by these tools also differ, for example Prokka produces files which must be viewed in a genome browser for interpretation [35], while MicrobeAnnotator can provide graphical outputs [34]. While all these tools can be utilized for the annotation of prokaryotic genomes, GeneMark also provides species-specific software versions for even more precise and accurate annotation [31].

Due to the revolution in the sequencing field, an enormous number of species have been sequenced and annotated [38, 39]. High-quality genome sequencing and annotations are a vital starting point for the reconstruction of metabolic networks at a systems level [40], which typically starts by generating a draft automated reconstruction which is further manually curated using knowledge from several biochemical databases and the literature to fill any gaps and address the presence of dead-end metabolites.

Reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models

With whole genome sequencing techniques becoming more accessible, the number of sequenced genomes has been growing exponentially since the first bacterial genomes were sequenced in 1995 [41–43]. As a result, various automated model reconstruction tools have emerged. These draft reconstructions are built using a genome annotation, and therefore these drafts are only as good as the quality of the annotation.

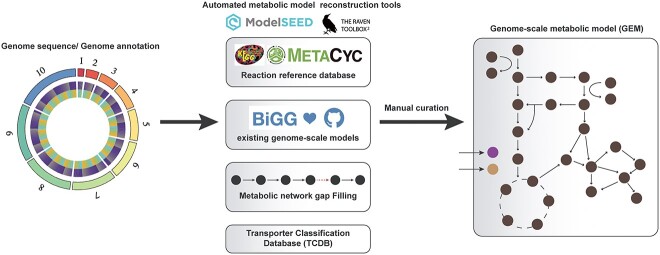

There are several tools available for the creation of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions. The most commonly employed of these tools are the Model SEED [44], the RAVEN toolbox [45], merlin [46], CarveMe [47] and Pathway Tools [48], though others do exist (Table 1). The major advantage of these new tools is that they produce simulation-ready GEMs, and some of them are also capable of implementing different analysis techniques and approaches (Table 1). The key differences among these tools include the type of input genome sequence, different reference reaction databases and various gap filling approaches. Annotated genome sequences are the required input for the RAVEN Toolbox, CarveMe and Pathway Tools, whereas Model SEED and merlin have inbuilt genome annotation tools (Table 1). All of these tools use a different combination of existing biochemical reference databases such as KEGG [56], MetaCyc [58], existing GEMs for other species in the BiGG database [55] and the Transporter Classification Database (TCDB) [57] (Table 1 and Figure 1). Gap filling is the most important feature for producing simulation-ready models, and each tool utilizes different approaches for this process. The Model SEED [44] and Pathway Tools [48] perform complete gap filling iteratively whereas the RAVEN Toolbox [45] identifies candidate reactions and allows the user to properly assign gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations before filling these gaps. The CarveMe [47] tool is based on top-down model reconstruction for specific organisms, where additional media constituents are added and gap filling is performed accordingly. The merlin [46] tool on the other hand does not support the automated filling of gaps though it does identify these gaps in the network.

Table 1.

Properties of automated metabolic reconstruction tools

| Tool | Input | Reference databases | User platform | Network visualization | Gap filling capability | Analysis capability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model SEED, Pathway Tools, RAVEN Toolbox | Unannotated or annotated sequence (RAST) | Model SEED, MetaCyc, KEGG | Web, GUI, MATLAB | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [44, 45, 48] |

| CarveMe | Unannotated sequences | BiGG | Command-line | × | ✓ | ✓ | [47] |

| AuReMe, FAME, GEMSiRV | Protein-coding sequences, other GEMs, KEGG Organism ID | MetaCyc, BiGG, KEGG, Model SEED | GUI, Web | ✓ | × | ✓ | [49–51] |

| merlin | Unannotated or annotated sequence | KEGG, TCDB | GUI | ✓ | × | × | [46] |

| CoReCo | Protein-coding sequences | KEGG | MATLAB | × | ✓ | × | [52] |

| AutoKEGGRec, MetaDraft | KEGG Organism ID, other GEMs | KEGG, BiGG | MATLAB, GUI | × | × | × | [53, 54] |

Note: Automated reconstruction tools are required for the generation of a draft metabolic network during the initial step of reconstructing the systems level metabolism of an organism. Different tools require different inputs and utilize different biochemical reference databases, and some also facilitate constraint-based analysis. Tick mark indicates a feature present within the software/tool while a cross indicates the absence of a feature.

Figure 1.

Schematic of fully functional genome-scale metabolic model reconstruction. Reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) begins with the generation of an automated draft reconstruction from an inputted genome annotation. There are several tools available for the reconstruction of these draft networks. Draft reconstructions require manual curation involving gap filling and the correction of dead-end metabolites by adding in reactions detailed in biochemical reference databases, including BiGG [55], KEGG [56] and the Transporter Classification Database [57].

Metabolic reconstructions often require extensive manual curation to ensure they best represent the known metabolic capabilities of an organism drawn from the genome annotation and literature. Despite increasingly more sophisticated algorithms implemented in reconstruction tools to maximize gap filling and the quality of automated metabolic reconstructions [59–61], manual curation efforts are still highly recommended to ensure a GEM is of the highest quality [62]. Following the protocol detailed by Thiele & Palsson [63], common stages in this curation process include updating metabolite and reaction identifiers to a universal format, such as those detailed on the BiGG database [55], gap filling by manual cross-checking with reference databases, literature searches and the identification of potential candidate orthologous genes which could fill these gaps [59].

Metabolic reconstructions are ultimately tools designed for researchers to utilize in their own metabolic research, and therefore platforms storing these models for ease of access are important. The BiGG database [55] currently contains 108 highly curated GEMs for both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms all with standardized identifiers for metabolites and reactions which are often integrated into other newly reconstructed GEMs (Table 1). Others include MEMOSys [64] which tracks changes made to GEMs available on the platform and MetExplore [65] which is primarily designed for collaboration.

Each of these tools has individual strengths and weaknesses, which must be taken into consideration. A study looking at differences between automated reconstructions and manually curated networks for Lactobacillus plantarum and Bordetella pertussis identified that while RAVEN performed the best for maintaining gene similarity, it maintained reaction similarity the least [66]. The Model SEED, Pathway Tools and merlin generated networks with the largest proportion of genes not present in the manually curated models [66], further emphasizing the need for manual curation during model reconstruction. MetaDraft maintained metabolite similarity the best and Model SEED, CarveMe and Pathway Tools generated reconstructions the fastest [66]. It is also important to consider the different templates these tools are utilizing for the construction of the biomass reaction and whether this is consistent with a Gram-positive or Gram-negative organism.

Constraint-based analysis approaches

Fluxes across reactions and metabolites in a metabolic reconstruction can be quantified whereby a specific objective function is optimized while satisfying imposed constraints [67–70]. Various constraint-based analysis approaches (Figure 2) have been developed and implemented for the analysis of GEMs, some of which are summarized below.

Figure 2.

Constraint-based analysis approaches for metabolic reconstruction simulations. Metabolic reconstructions are analyzed by imposing stoichiometric and mass balance constraints to generate phenotypic predictions. Linear programming (LP) generally lends itself to Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) which can be expanded beyond the classical steady-state assumption to become dynamic by integrating time (dFBA), to integrate the underlying geometry of the metabolic network (geometric FBA) and to include gene categorization (pFBA). Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) is also achieved through LP to determine the flux range of reactions in a network. Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) is typically applied to the analysis of genetically perturbed networks (i.e. ROOM). Quadratic Programming (QP) can also be used to analyze perturbed networks (i.e. MoMA) but can also expand FBA to integrate time in a dynamic fashion (dFBA).

Flux balance analysis (FBA)

FBA is the first and by far the most common constraint-based analysis approach for analyzing biological networks at the systems level [69, 71]. FBA imposes reaction stoichiometry and mass balance constraints, both of which are simple to implement [71]. A particular objective function can be simulated in silico, such as optimizing biomass production to predict growth phenotypes [72, 73], using FBA whereby the fluxes in the reconstruction must satisfy the stoichiometric and mass balance constraints in an assumed steady state [74]. The steady state allows the network to be mathematically represented through a series of linear equations which can be solved through linear programming [75]. FBA has been integrated with GEMs to address several biological questions, such as in silico gene deletions [76–78], characterization of minimal media conditions [78, 79] and the identification of potential drug targets [12, 79]. However, while the simplicity of FBA allows for its widespread implementation, it does have its limitations. The quality of predictions made through FBA is wholly dependent on the curation efforts during the reconstruction phase of creating a GEM; the presence of gaps or dead-end metabolites in a network will increase the unreliability of these predictions [80, 81].

Dynamic FBA (dFBA)

The steady state assumed in FBA is often not applicable to biological systems, whereby the environment will inevitably fluctuate over time. FBA can be extended to describe these dynamics by integrating a GEM with external metabolites to determine intracellular fluxes [82]. dFBA is performed either through a dynamic optimization approach (DOA) or a static optimization approach (SOA). Like FBA, the SOA uses linear programming to optimize an objective over time by repeatedly solving for this objective in separate time intervals [83]. In contrast, DOA utilizes non-linear programming to optimize for an objective over the entire time period of interest to obtain a single solution [82, 83]. dFBA has successfully been applied to several biological problems, including the modeling of human disease phenotypes [84], the modeling of microbial communities [3, 9, 85] and the optimization of biotechnological processes [86, 87].

Parsimonious FBA (pFBA)

pFBA, or parsimonious enzyme usage FBA, utilizes linear programming to classify genes present in a reconstruction depending on their contribution to the optimal solution and their associated flux [88]. pFBA is predominantly used to validate the expression of genes and proteins determined through transcriptomics or proteomics studies and their potential downstream metabolic effects [88, 89].

Geometric FBA

The optimal value for an objective function determined through FBA can often be achieved by multiple different solutions, known as network degeneracy [68, 75]. Ideally, the solution space in which these fluxes are distributed to support the optimal solution needs to be reduced and this can be achieved by considering the geometry underpinning the network [90]. Utilizing a geometric FBA approach can aid in the identification of particular metabolic pathways contributing to differences in model predictions in different simulations [91].

Minimization of metabolic adjustment (MoMA)

GEMs are often used to assess the effect of genetic perturbation on phenotypic predictions, with the assumption that these altered networks still represent the optimal metabolic state [92]. However, this is not representative of in vitro mutants. MoMA accounts for this discrepancy by relaxing the optimal flux distribution and minimizing the Euclidean distance between the wild-type and mutant flux distribution while still implementing the same constraints as FBA using quadratic programming [92]. MoMA has been used in metabolic engineering to identify optimal production conditions for products of biotechnological interest [93, 94].

Regulatory on/off minimization (ROOM) of metabolic flux changes

Similar to MoMA, ROOM is also a method used to make phenotypic predictions with GEMs following gene deletions [95]. ROOM differs from MoMA in that it identifies a flux distribution in a model experiencing a gene deletion which satisfies constraints while minimizing the number of significant flux changes in comparison to the original model [95], and also uses mixed integer linear programming.

Flux variability analysis (FVA)

This analysis approach works on the same principles as FBA, using the same stoichiometric and mass balance constraints. For each reaction in a reconstruction, FVA determines the minimum and maximum flux value which still satisfies the constraints and results in the optimal solution, thereby identifying the flux variability [75], accounting for network degeneracy explained previously. A similar result has also been described utilizing an approach whereby the minimum set of reactions which fulfill the optimal solution to an objective are identified [96]. FVA is commonly used to assess how well a network responds to perturbations, also referred to as robustness, but other applications include identifying optimal production conditions for a product of interest [97, 98].

Constraint-based modeling tools

Various tools exist to perform constraint-based analysis on metabolic reconstructions (Table 2). Toolboxes, which are installed as libraries in other commonly used analysis or visualization software [111], are by far the most commonly used and comprehensive in terms of the type of analysis that can be performed within them. The two most common available toolboxes are COBRA [99] and RAVEN [45], both of which can be installed as libraries in MATLAB. The COBRA toolbox has algorithms to perform all the different types of analyses described above, while RAVEN can be used for most with the exception of pFBA, geometric FBA and ROOM [45, 99]. In addition, both toolboxes can be used to aid the reconstruction process, including functions for gap filling and updating identifiers from other databases. Other available toolboxes include FluxAnalyzer [102], SNA [103], FBA-SimVis [104] and MetaFlux [80]. These toolboxes are capable of performing basic FBA and FVA, though are very limited in types of the other constraint-based analysis which can be implemented, unlike the COBRA and RAVEN toolboxes which have a far wider range of available analysis algorithms (Table 2).

Table 2.

Constraint-based analysis tools

| Tool | FBA | dFBA | pFBA | Geometric FBA | MoMA | ROOM | FVA | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [99] |

| RAVEN | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × | ✓ | [45] |

| OptFlux, FASIMU | ✓ | × | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [100, 101] |

| SBRT, MetaFluxNet, SurreyFBA, GEMSiRV, FluxAnalyzer, SNA, FBA-SimVis, FAME, Acorn, GSMN-TB | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | [50, 51, 102–109] |

| MicrobesFlux | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | [110] |

| MetaFlux, Model SEED | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | × | [44, 80] |

Note: All of the constraint-based analysis tools available for metabolic reconstruction simulations are capable of performing standard Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), but there are also several tools available to perform more advanced analyses which are capable of analyzing perturbed networks. The COBRA toolbox [99] is the most comprehensive of the tools described in this review. A tick mark indicates a feature present within the software/tool while a cross indicates the absence of a feature.

While toolboxes are installed within other mathematical software, there are also pieces of software which can be installed independently for analysis of metabolic reconstructions. While not as comprehensive as COBRA or RAVEN, OptFlux [100] and FASIMU [101] perform basic FBA, FVA, MoMA and ROOM. Other types of stand-alone software packages include the Systems Biology Research Tool (SBRT) [105], MetaFluxNet [106], SurreyFBA [107] and GEMSiRV [51].

Both toolboxes and independent software packages require some programming experience, but there are several web-based platforms which do not require any prior programming knowledge and are very easy to use. These platforms are more rendered for model reconstruction, such as the Model SEED [44] discussed previously, so do have limited capabilities though all can perform basic FBA. However, MicrobesFlux [110] can also perform dFBA and FAME [50], Acorn [108] and GSMN-TB [109] can run FVA.

In recent years, there has been a huge increase in the development of tools to analyze the metabolism of microbial communities including the gut microbiota [112], determining metabolic limitations of such communities [113] and predicting microbial abundances within consortia [114]. Modeling and analysis of metabolic communities is challenging in terms of selecting an appropriate objective to account for trade-offs between the different species in the consortia and the community growth rate [9] as well as logistical challenges such as the integration of multiple reconstructions for each species in the community [113]. Community FBA (cFBA) is a methodology developed for such purposes [113], which integrates individual microbial GEMs and details metabolite exchanges between the species in the community [113], but other available tools include MICOM [112], SteadyCom [114] and metaGEM [115] which is a pipeline for metabolic reconstruction of microbial communities from metagenomes.

Integration of ‘-omics’ data

GEMs can be expanded through the integration of transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics data to create context-specific models (Figure 3), describing the metabolism of an organism in a particular environment. The majority of research involving the reconstruction of context-specific models refers to those describing the metabolism of a particular cell line or tissue [116–118], or to human models to identify potential therapeutic targets [119, 120]. However, context-specific microbial metabolic models also have several applications.

Figure 3.

Integration of ‘-omics’ data to create context-specific models. Context-specific models describe the metabolism of an organism in two particular conditions, providing valuable platforms to study the metabolic adaptations occurring in an organism in a particular condition. Mapping gene or protein expression to the gene-protein-reaction associations present in metabolic reconstructions can define which reactions are active and inactive between two different conditions while metabolomics data can provide insight into metabolic use requirements. Context-specific models have several applications in biology, including investigating the effect of environmental and genetic perturbations in microbial strains.

GEMs contain gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations, and therefore gene expression data obtained through transcriptomic experiments can be integrated into networks by adjusting reaction fluxes. Gene expression data are mapped onto GPR associations to define inactive and active reactions in the condition of interest, and from this definition context-specific models are extracted [121]. Several algorithms have been developed to integrate such data with metabolic networks, but the most common are the Gene Inactivity Moderated by Metabolism and Expression (GIMME) algorithm [20] which can be implemented from within the COBRA or RAVEN toolboxes [45, 99] and the integrative Metabolic Analysis Tool (iMAT) [122]. GIMME uses quantitative gene expression data, such as differential gene expression datasets, along with an objective function [20] to alter reconstructions to represent the condition in which the transcriptomics data were collected. iMAT can integrate functional data, either from a transcriptomics or proteomics experiment, with a metabolic network to create a map in which the metabolic state of an organism in a particular condition can be visualized [122]. Interestingly, it has been shown that the accuracy of flux predictions is comparable for models integrated with transcriptomics or proteomics data [123].

To ensure that context-specific models are representative of the organism’s metabolism in a particular context, it is vital to evaluate expression scores while mapping to GPR associations [22, 121]. Thresholds for these expression scores must be determined carefully to ensure predictive accuracy of these reconstructions. Several algorithms have been developed for this purpose, such as single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) which can be combined with GIMME [124]. Consideration of such expression scores allows housekeeping genes, which will be expressed in low quantities, to be kept in the final reconstruction [22]. There are also developed techniques to utilize transcriptomics data to expand metabolic reconstructions to include information regarding regulatory interactions for the reconstruction of transcriptional regulatory networks (TRNs) [125].

The GIMME algorithm can also be extended to include metabolomics: the Gene Inactivation Moderated by Metabolism, Metabolomics and Expression (GIM3E) algorithm [126]. Integration of metabolomics data into metabolic reconstructions relates the structural properties of the network to quantitatively determined metabolite levels [126]. GIM3E determines metabolite use requirements from metabolomics data to ensure that necessary metabolites are accounted for in the reconstruction and carry flux to optimize the objective function [126], and acts as a further constraint alongside the gene expression data. Integration of such data reduces the number of alternate optimal solutions following constraint-based analysis [67]. Other tools, such as Relative Expression and Metabolomics Integration (REMI) [67], utilize exo-metabolomics data to integrate metabolic abundance data into reconstructions to maximize metabolite concentrations in context-specific models [21].

Integration of microbial GEMs with ‘-omics’ data can enhance our understanding of microbial metabolism during infection such as deciphering the metabolic changes induced in pathogens by antibiotic treatment [127], exploring changes in growth rate experienced by microbes during adaptation [21] and identifying potential virulence factors [15, 16]. Context-specific models can also have biotechnological applications including analyzing the thermotolerance of biomass degrading fungi and yeasts with potential use in the food and pharmaceutical industry [128].

For models of Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae integrated with transcriptomics data, pFBA was the most accurate at predicting reaction fluxes compared with experimentally measured fluxes [123]. However, metabolomics data are sparce, and the small amount of experimental data available is likely to introduce biases [123] when comparing different methods for the generation of context-specific models.

Investigating genetic perturbations

Genome-scale metabolic models are a valuable tool to investigate the lethality and downstream metabolic effects of gene knockouts or mutations in species [80, 92, 95, 129], which is not always feasible, both practically and financially, in a laboratory setting.

Identifying essential genes

Genome-scale essentiality studies have become increasingly popular in the last 20 years, but they are expensive and not always feasible, particularly for less well-studied species. Such datasets are often used to validate phenotypic predictions generated from model reconstructions [15, 130, 131]. However, context-specific models can be utilized to identify potential essential genes in simulated conditions of interest (Figure 4). To simulate the knockout (KO) of a particular gene, all associated reactions are switched off and the model is simulated to optimal growth; if this predicted growth rate is zero then the gene is considered essential. It has been shown that essential genes predicted by highly curated and validated models in this approach are highly accurate, and these reconstructions can be used for the identification of potential drug or therapeutic targets [19, 132–134].

Figure 4.

Investigating the effect genetic perturbations have on the metabolism of an organism. Genetically perturbed microbial strains, including single or double gene knockouts (KOs) and gene knockdowns, can be investigated using GEMs. In silico single gene KOs, performed by making all reactions controlled by an individual gene inactive, can identify candidate essential genes for further investigation in vitro to optimize culture medium or as potential therapeutic targets. Mutant strains can be created in silico by incorporating gene KOs and/or gene knockdowns, by inactivating and reducing the flux of reactions controlled by a gene(s), respectively. Optimization of mutant strains in silico can predict mutant phenotypes which can be further confirmed in the laboratory for the identification of potential drug targets, virulence factors and metabolic engineering purposes. By increasing the flux of reactions associated with an individual gene, in silico genetic overexpression can be used in metabolic engineering to predict candidate genes which increase the yield of a product of interest. The growth rate of mutant strains can be compared to the predicted growth of the wild-type model to elucidate any phenotypic effects induced by the genetic perturbation.

Investigating mutant strain phenotypes

Generating mutant bacterial strains, gene knockdowns or knockouts, can be challenging and elucidating any downstream effects can be even more challenging. Creating reconstructions of mutant strains in silico can be particularly helpful to determine the effects this genetic perturbation has on metabolism. For example, simulation of in silico single and double mutant strains of Mycoplasma pneumonia, using an experimentally validated GEM, revealed that biomass synthesis in this pathogen has very limited adaptability [135]. Metabolic modeling can also be used as a platform to investigate the mechanisms underlying known mutant phenotypes (Figure 4); however this is currently rarely applied to microbial models and instead has been used in models of eukaryotes, such as the model organism Neurospora [136].

Examining gene overexpression

Strain-design algorithms can be implemented with GEMs in metabolic engineering approaches to identify optimal conditions for the maximal production of a particular metabolite of interest. Such approaches have been implemented to identify that the overexpression of genes encoding the enzymes acetyl-CoA carboxylase and branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase in Streptomyces coelicolor increase antibiotic production [137]. Similar approaches have also been used to optimize rapamycin and ascomycin production by Streptomyces hygroscopicus [5, 7]. Guided strain design can also utilize FVA to make similar predictions for products of industrial interest, such as increasing the production of isoprene by overexpressing glycolysis and cofactor biosynthetic genes [6] (Figure 4).

Investigating environmental perturbations

Context-specific models can be an invaluable tool when studying the metabolic adaptations microbes employ to various stresses encountered in the environment (Figure 5), and can help elucidate the mechanisms underlying such stress responses in both commensal and pathogenic microbial species.

Figure 5.

Investigating environmental perturbations using metabolic reconstructions. Context-specific genome-scale metabolic models are valuable platforms to study the metabolic adaptations occurring in an organism in response to different environmental perturbations, including altering nutritional environments, pH, osmotic stress, temperature changes and oxidative stress. These perturbations are predominantly studied through the integration of transcriptomics and proteomics data, but stoichiometric reconstructions can also be expanded to include further kinetic constraints to create more predictive models in regards to environmental perturbations, particularly osmotic stress and temperature changes.

Nutrient limitation and supplementation

Nutrients available in an organism’s environment can vary depending on whether this environment is aerobic or anaerobic, the population of different microbial species also present and if it represents a niche within a multicellular host. Exchange reactions describing the uptake of a metabolite from the extracellular to cytosolic compartment can be used to simulate the nutrient conditions of interest [138]. The ability to alter the nutrient availability during constraint-based analysis allows the identification of media compositions for a variety of purposes, which can be replicated experimentally, such as a nutrient-rich medium to identify essential genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [139], the identification of supplemental nutrients to support the anaerobic growth of Parageobacillus thermoglucosidasius [140] and examining how lysine supplementation triggers underground polyamine metabolism as an antioxidant strategy [141]. Analysis of the utilization of multiple nutrients is frequently used as a validation step during GEM reconstruction through comparison with experimental data [77, 130, 142–144].

Pathogenic and symbiotic microbes often encounter nutrient limitations in the host niche, and must adapt their metabolism accordingly in regards to nutrient assimilation [145]. In response to infection by bacterial pathogens, mammalian hosts often sequester essential nutrients in an attempt to prevent bacterial growth, yet several of these pathogens have developed techniques to subvert these mechanisms, which is often referred to as a nutritional virulence strategy [146]. Metabolic reconstructions can be used to analyze the metabolic adaptations which occur in bacterial pathogens to best survive within the host niche by simulating these limiting nutrient conditions encountered in these environments [147–149].

pH

Microbes encounter changes in pH in several environments, such as during fermentation, as part of the gut microbiota and in the soil following rainfall. While GEMs do not contain ion channels, they do include the presence of charged ions as metabolites, including protons, with corresponding exchange reactions between the extracellular and cytosolic space. However, metabolic reconstructions do not contain information on the extracellular accumulation of such ions which would describe the change in environmental pH. Integration of ‘-omics’ data with metabolic models can still lead to the creation of context-specific models encapsulating the metabolism of an organism at a particular pH. The integration of proteomics data for Enterococcus faecalis grown at physiological pH revealed mechanisms the pathogen undergoes to grow at the pH encountered in a human host [150]. Use of experimental data describing enzymatic function at a particular pH can also be integrated with the GPR associations in a reconstruction, though this relies extensively on specific experimental data of the kind of which is extremely limited in the literature at present [151].

Osmotic stress

Studying the metabolic profile of halophilic bacteria has revealed several adaptations that contribute to the survival of such microorganisms in response to osmotic stress. Metabolic reconstructions of the well-characterized halophilic genuses Chromohalobacter and Microbacterium have successfully reproduced phenotypes displaying the osmoadaptation of these species, predominantly focused on the accumulation of osmoprotectants and production of salt-tolerant enzymes which have applications in biotechnology [18, 152–154]. Microbes also encounter osmotic stress in artificial environments, such as batch cultures. Studies using metabolic reconstructions of E. coli identified the optimal salt concentration in batch cultures to induce a switch from aerobic to fermentative pathways [17]. Typical stoichiometric reconstructions can be expanded to also include reaction kinetics, such as Michaelis–Menten kinetics of enzymes, to create kinetic models which are more mechanistic representations of a system than metabolic reconstructions analyzed through FBA [155]. Kinetic models are becoming increasingly applied to studying the effects enzyme kinetics in high salinity environments have on downstream metabolism, though currently these approaches have only been described in yeast [155].

Temperature

The majority of temperature-specific metabolic models are created through the integration of transcriptomics data of organisms growing at two different temperatures in vitro. The integration of ‘-omics’ data to create temperature-specific models is predominantly achieved using FVA to align flux and expression ratios [156]. Metabolic factors contributing to thermotolerance have been investigated using temperature-specific reconstructions of the fungus Kluyveromyces marxianus [128] and the Antarctic bacterium Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis [157]. Enzyme structure and function can be affected by temperature fluctuations. Kinetic models are more typically associated with studying temperature responses in different organisms. The Arrhenius law describes how reaction rates are dependent on temperature, and using this law in kinetic models has been applied to studying temperature adaptations in eukaryotes, including yeast and plants [158]. However, the expansion of stoichiometric-based reconstructions with Michaelis–Menten dynamics and mass-action kinetics can also be used to study the bacterial metabolic response to fluctuations in temperature [159]. The recently published GECKO toolbox could enhance the generation of temperature-specific microbial reconstructions through providing a platform to integrate enzyme constraints elucidated through proteomics data [160].

Oxidative stress

Context-specific metabolic models detailing microbial metabolism in conditions of oxidative stress are relatively limited compared to the other environmental perturbations described. However, the limited examples available do provide insights into the metabolic pathways vital for metabolic adaptations during oxidative stress. Models of the gut bacterium Enterococcus have identified that the metabolism of reactive oxygen species induced by cancer treatments is highly linked with the metabolism of folate [161], while simulating an environment conducive to the production of reactive nitrogen species in Rhodococcus predicted a metabolic reroute through the pentose phosphate pathway [162].

CONCLUSION

GEMs are becoming an increasingly valuable tool to study how the metabolism of microorganisms facilitates adaptation to different environmental perturbations. Metabolic reconstructions of a microbial species can be generated from a genome annotation using several different tools, with the COBRA Toolbox [99], RAVEN Toolbox [45] and the Model SEED [44] being the most comprehensive. Other tools can generate these reconstructions from an unannotated sequence, such as CarveMe [47], while others can utilize other published GEMs as templates, including AuReMe [49], GEMSiRV [51] and MetaDraft [54].

While multiple genetic or environmental perturbations can be studied using metabolic reconstructions, the type of constraint-based analysis applied to the study of these different perturbations, and the tool chosen for this analysis, needs to be carefully selected in order to get the most accurate predictions. The most common type of constraint-based analysis applied to predict fluxes across microbial metabolic networks is FBA, which can be expanded to account for fluctuating dynamics across time in dFBA or for network topology in geometric FBA. Other approaches can assess the effects of genetic or environmental perturbation on a system, including MoMA [92], ROOM [95] and FVA [75, 96]. Both FBA and FVA can be implemented in almost all available constraint-based analysis tools. The COBRA Toolbox can implement all the constraint-based analysis described in this study [99]. All the remaining tools are limited to the implementation of FBA and FVA with the exception of FASIMU [101] and OptFlux [100] which can implement MoMA and ROOM, and the RAVEN Toolbox [45] which is capable of MoMA and dFBA.

The study of some environmental perturbations, particularly temperature and pH, is limited with standard metabolic reconstructions, but integration with other data, such as enzyme kinetics, will greatly enhance the predictive qualities and applications of such models. The predictions generated by metabolic reconstructions provide valuable insight when designing experiments, such as the identification of promising gene or proteins of interest for adaptation studies that would otherwise have been infeasible to elucidate experimentally, either for financial or technical reasons.

Key Points

Genome-scale metabolic models are valuable tools for investigating microbial metabolism at a systems-level, and are becoming increasingly utilized with the increasing speed, accuracy and accessibility of genome sequencing and annotation technologies.

Several tools exist for the automated reconstruction of microbial metabolic networks, though manual curation is often still required to address gaps in these networks.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is the most common method to predict fluxes across reactions in metabolic reconstructions, but has limitations; therefore, several other methods have been developed to expand upon this methodology, including dynamic FBA, geometric FBA and parsimonious FBA.

Microbes will adapt their metabolism in response to several genetic and environmental perturbations, and simulating these perturbations through the integration of ‘-omics’ datasets with metabolic reconstructions and the use of other constraint-based analysis approaches can aid in the elucidation of such adaptations.

Elena Lucy Carter is a final year PhD student at Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7HL, UK. Her research interests are metabolic model reconstruction, microbial metabolic adaptation and bioinformatics.

Chrystala Constantinidou has been a Principal Research Fellow in Microbial Genomics at Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick. She is an expert in the field of next-generation sequencing.

Mohammad Tauqeer Alam is an Assistant Professor at the United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, UAE. His research interests are metabolic modeling, microbial metabolic interactions, network analysis, bioinformatics and systems biology.

Contributor Information

Elena Lucy Carter, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7HL, UK.

Chrystala Constantinidou, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick.

Mohammad Tauqeer Alam, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, UAE.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.L.C. and M.T.A. wrote the first draft of the paper followed by contributions from all authors in the final draft.

FUNDING

The funding for E.L.C. is provided through the MRC Doctoral Training Partnership at the University of Warwick, under the grant number MR/N014294/1. This funding source also covers the publication fees. M.T.A. was supported by the UAE University internal research grants (startup grant code G00003688, and UAEU Program for Advanced Research (UPAR) grant code G00004152).

DATA AVAILABILITY

There is no additional data available. All the details are included in the article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Edwards JS, Palsson BO. Systems properties of the Haemophilus influenzae RD metabolic genotype. J Biol Chem 1999;274:17410–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gu C, Kim GB, Kim WJ, et al. Current status and applications of genome-scale metabolic models. Genome Biol 2019;20:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colarusso AV, Goodchild-Michelman I, Rayle M, Zomorrodi AR. Computational modeling of metabolism in microbial communities on a genome-scale. Curr Opin Syst Biol 2021;26:46–57. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang C, Hua Q. Applications of genome-scale metabolic models in biotechnology and systems medicine. Front Physiol 2016;6:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dang L, Liu J, Wang C, et al. Enhancement of rapamycin production by metabolic engineering in Streptomyces hygroscopicus based on genome-scale metabolic model. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2017;44:259–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hendry JI, Bandyopadhyay A, Srinivasan S, et al. Metabolic model guided strain design of cyanobacteria. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2020;64:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang J, Wang C, Song K, Wen J. Metabolic network model guided engineering ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway to improve ascomycin production in Streptomyces hygroscopicus var. ascomyceticus. Microb Cell Factories 2017;16:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ankrah NYD, Bernstein DB, Biggs M, et al. Enhancing microbiome research through genome-scale metabolic modeling. mSystems 2021;6:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diener C, Gibbons SM. More is different: metabolic modeling of diverse microbial communities. mSystems 2023;8:e0127022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heinken A, Basile A, Thiele I. Advances in constraint-based modelling of microbial communities. Curr Opin Syst Biol 2021;27:100346. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yu JSL, Correia-Melo C, Zorrilla F, et al. Microbial communities form rich extracellular metabolomes that foster metabolic interactions and promote drug tolerance. Nat Microbiol 2022;7:542–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jamshidi N, Palsson BØ. Investigating the metabolic capabilities of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv using the in silico strain iNJ 661 and proposing alternative drug targets. BMC Syst Biol 2007;1:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rienksma RA, Suarez-Diez M, Spina L, et al. Systems-level modeling of mycobacterial metabolism for the identification of new (multi-)drug targets. Semin Immunol 2014;26:610–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Viana R, Dias O, Lagoa D, et al. Genome-scale metabolic model of the human pathogen candida albicans: a promising platform for drug target prediction. J Fungi 2020;6:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bartell JA, Blazier AS, Yen P, et al. Reconstruction of the metabolic network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to interrogate virulence factor synthesis. Nat Commun 2017;8:14631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jenior ML, Leslie JL, Powers DA, et al. Novel drivers of virulence in Clostridioides difficile identified via context-specific metabolic network analysis. mSystems 2021;6:e0091921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Metris A, George SM, Mulholland F, et al. Metabolic shift of Escherichia coli under salt stress in the presence of glycine betaine. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014;80:4745–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mandakovic D, Cintolesi Á, Maldonado J, et al. Genome-scale metabolic models of Microbacterium species isolated from a high altitude desert environment. Sci Rep 2020;10:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ding T, Case KA, Omolo MA, et al. Predicting essential metabolic genome content of niche-specific enterobacterial human pathogens during simulation of host environments. PLoS One 2016;11:e0149423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Becker SA, Palsson BO. Context-specific metabolic networks are consistent with experiments. PLoS Comput Biol 2008;4:e1000082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hadadi N, Pandey V, Chiappino-Pepe A, et al. Mechanistic insights into bacterial metabolic reprogramming from omics-integrated genome-scale models. NPJ Syst Biol Appl 2020;6:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gopalakrishnan S, Joshi CJ, Valderrama-Gómez MÁ, et al. Guidelines for extracting biologically relevant context-specific metabolic models using gene expression data. Metab Eng 2023;75:181–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sanger F. The Croonian lecture, 1975. Nucleotide sequences in DNA. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol Sci 1975;191:317–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sanger F, Coulson AR. A rapid method for determining sequences in DNA by primed synthesis with DNA polymerase. J Mol Biol 1975;94:441–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1977;74:5463–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pareek CS, Smoczynski R, Tretyn A. Sequencing technologies and genome sequencing. J Appl Genet 2011;52:413–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Steemers FJ, Gunderson KL. Illumina, Inc. Pharmacogenomics 2005;6:777–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rhoads A, Au KF. PacBio sequencing and its applications. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2015;13:278–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mathé C, Sagot M-F, Schiex T, Rouzé P. Current methods of gene prediction, their strengths and weaknesses. Nucleic Acids Res 2002;30:4103–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Larsen TS, Krogh A. EasyGene—a prokaryotic gene finder that ranks ORFs by statistical significance. BMC Bioinformatics 2003;4:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Besemer J, Borodovsky M. GeneMark: web software for gene finding in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses. Nucleic Acids Res 2005;33:W451–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tatusova T, DiCuccio M, Badretdin A, et al. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:6614–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tanizawa Y, Fujisawa T, Nakamura Y. DFAST: a flexible prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline for faster genome publication. Bioinformatics 2018;34:1037–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ruiz-Perez CA, Conrad RE, Konstantinidis KT. MicrobeAnnotator: a user-friendly, comprehensive functional annotation pipeline for microbial genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 2021;22:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014;30:2068–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 2004;5:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Besemer J, Lomsadze A, Borodovsky M. GeneMarkS: a self-training method for prediction of gene starts in microbial genomes. Implications for finding sequence motifs in regulatory regions. Nucleic Acids Res 2001;29:2607–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Besser J, Carleton HA, Gerner-Smidt P, et al. Next-generation sequencing technologies and their application to the study and control of bacterial infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018;24:335–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kobras CM, Fenton AK, Sheppard SK. Next-generation microbiology: from comparative genomics to gene function. Genome Biol 2021;22:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Carey MA, Dräger A, Beber ME, et al. Community standards to facilitate development and address challenges in metabolic modeling. Mol Syst Biol 2020;16:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fraser CM, Gocayne JD, White O, et al. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science 1995;270:397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fleischmann RD, Adams MD, White O, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae RD. Science 1995;269:496–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Land M, Hauser L, Jun S-R, et al. Insights from 20 years of bacterial genome sequencing. Funct Integr Genomics 2015;15:141–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Henry CS, DeJongh M, Best AA, et al. High-throughput generation, optimization and analysis of genome-scale metabolic models. Nat Biotechnol 2010;28:977–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang H, Marcišauskas S, Sánchez BJ, et al. RAVEN 2.0: a versatile toolbox for metabolic network reconstruction and a case study on Streptomyces coelicolor. PLoS Comput Biol 2018;14:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dias O, Rocha M, Ferreira EC, Rocha I. Reconstructing genome-scale metabolic models with merlin. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:3899–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Machado D, Andrejev S, Tramontano M, Patil KR. Fast automated reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models for microbial species and communities. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46:7542–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Karp PD, Paley S, Romero P. The pathway tools software. Bioinformatics 2002;18(Suppl 1):S225–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Aite M, Chevallier M, Frioux C, et al. Traceability, reproducibility and wiki-exploration for ‘à-la-carte’ reconstructions of genome-scale metabolic models. PLoS Comput Biol 2018;14:e1006146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Boele J, Olivier BG, Teusink B. FAME, the flux analysis and modeling environment. BMC Syst Biol 2012;6:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Liao Y-C, Tsai M-H, Chen F-C, Hsiung CA. GEMSiRV: a software platform for GEnome-scale metabolic model simulation, reconstruction and visualization. Bioinformatics 2012;28:1752–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pitkänen E, Jouhten P, Hou J, et al. Comparative genome-scale reconstruction of gapless metabolic networks for present and ancestral species. PLoS Comput Biol 2014;10:e1003465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Karlsen E, Schulz C, Almaas E. Automated generation of genome-scale metabolic draft reconstructions based on KEGG. BMC Bioinformatics 2018;19:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hanemaaijer M, Olivier BG, Röling WFM, et al. Model-based quantification of metabolic interactions from dynamic microbial-community data. PLoS One 2017;12:e0173183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. King ZA, Lu J, Dräger A, et al. BiGG models: a platform for integrating, standardizing and sharing genome-scale models. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:D515–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kanehisa M. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2000;28:27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Saier MH, Reddy VS, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, et al. The transporter classification database (TCDB): 2021 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2021;49:D461–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Caspi R, Billington R, Keseler IM, et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes—a 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2020;48:D445–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Benedict MN, Mundy MB, Henry CS, et al. Likelihood-based gene annotations for gap filling and quality assessment in genome-scale metabolic models. PLoS Comput Biol 2014;10:e1003882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pan S, Reed JL. Advances in gap-filling genome-scale metabolic models and model-driven experiments lead to novel metabolic discoveries. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2018;51:103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Thiele I, Vlassis N, Fleming RMT. fastGapFill: efficient gap filling in metabolic networks. Bioinformatics 2014;30:2529–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Karp PD, Weaver D, Latendresse M. How accurate is automated gap filling of metabolic models? BMC Syst Biol 2018;12:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Thiele I, Palsson BØ. A protocol for generating a high-quality genome-scale metabolic reconstruction. Nat Protoc 2010;5:93–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pabinger S, Snajder R, Hardiman T, et al. MEMOSys 2.0: an update of the bioinformatics database for genome-scale models and genomic data. Database 2014;2014:bau004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cottret L, Frainay C, Chazalviel M, et al. MetExplore: collaborative edition and exploration of metabolic networks. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46:W495–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mendoza SN, Olivier BG, Molenaar D, Teusink B. A systematic assessment of current genome-scale metabolic reconstruction tools. Genome Biol 2019;20:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pandey V, Hadadi N, Hatzimanikatis V. Enhanced flux prediction by integrating relative expression and relative metabolite abundance into thermodynamically consistent metabolic models. PLoS Comput Biol 2019;15:e1007036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Murabito E, Simeonidis E, Smallbone K, Swinton J. Capturing the essence of a metabolic network: a flux balance analysis approach. J Theor Biol 2009;260:445–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Raman K, Chandra N. Flux balance analysis of biological systems: applications and challenges. Brief Bioinform 2009;10:435–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Becker SA, Feist AM, Mo ML, et al. Quantitative prediction of cellular metabolism with constraint-based models: the COBRA toolbox. Nat Protoc 2007;2:727–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Orth JD, Thiele I, Palsson BO. What is flux balance analysis? Nat Biotechnol 2010;28:245–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ibarra RU, Edwards JS, Palsson BO. Escherichia coli K-12 undergoes adaptive evolution to achieve in silico predicted optimal growth. Nature 2002;420:186–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Carlson R, Srienc F. Fundamental Escherichia coli biochemical pathways for biomass and energy production: creation of overall flux states. Biotechnol Bioeng 2004;86:149–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Oberhardt MA, Chavali AK, Papin JA. Flux balance analysis: interrogating genome-scale metabolic networks. Methods Mol Biol 2009;500:61–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mahadevan R, Schilling CH. The effects of alternate optimal solutions in constraint-based genome-scale metabolic models. Metab Eng 2003;5:264–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Edwards JS, Palsson BO. The Escherichia coli MG1655 in silico metabolic genotype: its definition, characteristics, and capabilities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:5528–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Duarte NC, Herrgård MJ, Palsson BØ. Reconstruction and validation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae iND750, a fully compartmentalized genome-scale metabolic model. Genome Res 2004;14:1298–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Schilling CH, Covert MW, Famili I, et al. Genome-scale metabolic model of Helicobacter pylori 26695. J Bacteriol 2002;184:4582–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Becker SA, Palsson BØ. Genome-scale reconstruction of the metabolic network in Staphylococcus aureus N315: an initial draft to the two-dimensional annotation. BMC Microbiol 2005;5:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Latendresse M, Krummenacker M, Trupp M, Karp PD. Construction and completion of flux balance models from pathway databases. Bioinformatics 2012;28:388–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mackie A, Keseler IM, Nolan L, et al. Dead end metabolites—defining the known unknowns of the E. coli metabolic network. PLoS One 2013;8:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. de Oliveira RD, Le Roux GAC, Mahadevan R. Nonlinear programming reformulation of dynamic flux balance analysis models. Comput Chem Eng 2023;170:108101. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mahadevan R, Edwards JS, Doyle FJ, 3rd. Dynamic flux balance analysis of diauxic growth in Escherichia coli. Biophys J 2002;83:1331–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ben Guebila M, Thiele I. Dynamic flux balance analysis of whole-body metabolism for type 1 diabetes. Nat Comput Sci 2021;1:348–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Karimian E, Motamedian E. ACBM: an integrated agent and constraint based modeling framework for simulation of microbial communities. Sci Rep 2020;10:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chang L, Liu X, Henson MA. Nonlinear model predictive control of fed-batch fermentations using dynamic flux balance models. J Process Control 2016;42:137–49. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Dvoretsky DS, Temnov MS, Markin IV, et al. Problems in the development of efficient biotechnology for the synthesis of valuable components from microalgae biomass. Theor Found Chem Eng 2022;56:425–39. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Lewis NE, Hixson KK, Conrad TM, et al. Omic data from evolved E. coli are consistent with computed optimal growth from genome-scale models. Mol Syst Biol 2010;6:390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Jenior ML, Moutinho TJ, Dougherty BV, Papin JA. Transcriptome-guided parsimonious flux analysis improves predictions with metabolic networks in complex environments. PLoS Comput Biol 2020;16:e1007099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Smallbone K, Simeonidis E. Flux balance analysis: a geometric perspective. J Theor Biol 2009;258:311–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yuan H, Cheung CYM, Hilbers PAJ, et al. Flux balance analysis of plant metabolism: the effect of biomass composition and model structure on model predictions. Front Plant Sci 2016;7:537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Segrè D, Vitkup D, Church GM. Analysis of optimality in natural and perturbed metabolic networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2002;99:15112–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Tang PW, Choon YW, Mohamad MS, et al. Optimising the production of succinate and lactate in Escherichia coli using a hybrid of artificial bee colony algorithm and minimisation of metabolic adjustment. J Biosci Bioeng 2015;119:363–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Arif MA, Mohamad MS, Abd Latif MS, et al. A hybrid of cuckoo search and minimization of metabolic adjustment to optimize metabolites production in genome-scale models. Comput Biol Med 2018;102:112–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Shlomi T, Berkman O, Ruppin E. Regulatory on/off minimization of metabolic flux changes after genetic perturbations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:7695–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Burgard AP, Vaidyaraman S, Maranas CD. Minimal reaction sets for Escherichia coli metabolism under different growth requirements and uptake environments. Biotechnol Prog 2001;17:791–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Feist AM, Zielinski DC, Orth JD, et al. Model-driven evaluation of the production potential for growth-coupled products of Escherichia coli. Metab Eng 2010;12:173–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Pharkya P, Maranas CD. An optimization framework for identifying reaction activation/inhibition or elimination candidates for overproduction in microbial systems. Metab Eng 2006;8:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Heirendt L, Arreckx S, Pfau T, et al. Creation and analysis of biochemical constraint-based models using the COBRA toolbox v.3.0. Nat Protoc 2019;14:639–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Rocha I, Maia P, Evangelista P, et al. OptFlux: an open-source software platform for in silico metabolic engineering. BMC Syst Biol 2010;4:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Hoppe A, Hoffmann S, Gerasch A, et al. FASIMU: flexible software for flux-balance computation series in large metabolic networks. BMC Bioinformatics 2011;12:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Klamt S, Stelling J, Ginkel M, et al. FluxAnalyzer: exploring structure, pathways, and flux distributions in metabolic networks on interactive flux maps. Bioinformatics 2003;19:261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Urbanczik R. SNA—a toolbox for the stoichiometric analysis of metabolic networks. BMC Bioinformatics 2006;7:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Grafahrend-Belau E, Klukas C, Junker BH, et al. FBA-SimVis: interactive visualization of constraint-based metabolic models. Bioinformatics 2009;25:2755–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Wright J, Wagner A. The systems biology research tool: evolvable open-source software. BMC Syst Biol 2008;2:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Lee D-Y, Yun H, Park S, et al. MetaFluxNet: the management of metabolic reaction information and quantitative metabolic flux analysis. Bioinformatics 2003;19:2144–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Gevorgyan A, Bushell ME, Avignone-Rossa C, et al. SurreyFBA: a command line tool and graphics user interface for constraint-based modeling of genome-scale metabolic reaction networks. Bioinformatics 2011;27:433–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Sroka J, Bieniasz-Krzywiec L, Gwóźdź S, et al. Acorn: a grid computing system for constraint based modeling and visualization of the genome scale metabolic reaction networks via a web interface. BMC Bioinformatics 2011;12:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Beste DJV, Hooper T, Stewart G, et al. GSMN-TB: a web-based genome-scale network model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis metabolism. Genome Biol 2007;8:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Feng X, Xu Y, Chen Y, et al. MicrobesFlux: a web platform for drafting metabolic models from the KEGG database. BMC Syst Biol 2012;6:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Lakshmanan M, Koh G, Chung BKS, Lee DY. Software applications for flux balance analysis. Brief Bioinform 2014;15:108–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Diener C, Gibbons SM, Resendis-Antonio O. MICOM: metagenome-scale modeling to infer metabolic interactions in the gut microbiota. mSystems 2020;5:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Khandelwal RA, Olivier BG, Röling WFM, et al. Community flux balance analysis for microbial consortia at balanced growth. PLoS One 2013;8:e64567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Chan SHJ, Simons MN, Maranas CD. SteadyCom: predicting microbial abundances while ensuring community stability. PLoS Comput Biol 2017;13:e1005539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Zorrilla F, Buric F, Patil KR, et al. metaGEM: reconstruction of genome scale metabolic models directly from metagenomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2021;49:e126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Richelle A, Chiang AWT, Kuo CC, et al. Increasing consensus of context-specific metabolic models by integrating data-inferred cell functions. PLoS Comput Biol 2019;15:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Granata I, Manipur I, Giordano M, et al. TumorMet: a repository of tumor metabolic networks derived from context-specific genome-scale metabolic models. Sci Data 2022;9:607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Gustafsson J, Anton M, Roshanzamir F, et al. Generation and analysis of context-specific genome-scale metabolic models derived from single-cell RNA-Seq data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023;120:e2217868120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Cho JS, Gu C, Han TH, et al. Reconstruction of context-specific genome-scale metabolic models using multiomics data to study metabolic rewiring. Curr Opin Syst Biol 2019;15:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 120. Nam H, Campodonico M, Bordbar A, et al. A systems approach to predict oncometabolites via context-specific genome-scale metabolic networks. PLoS Comput Biol 2014;10:e1003837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Ponce-de-León M, Apaolaza I, Valencia A, et al. On the inconsistent treatment of gene-protein-reaction rules in context-specific metabolic models. Bioinformatics 2020;36:1986–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Zur H, Ruppin E, Shlomi T. iMAT: an integrative metabolic analysis tool. Bioinformatics 2010;26:3140–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Machado D, Herrgård M. Systematic evaluation of methods for integration of transcriptomic data into constraint-based models of metabolism. PLoS Comput Biol 2014;10:e1003580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Jalili M, Scharm M, Wolkenhauer O, et al. Metabolic function-based normalization improves transcriptome data-driven reduction of genome-scale metabolic models. NPJ Syst Biol Appl 2023;9:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Chandrasekaran S, Price ND. Metabolic constraint-based refinement of transcriptional regulatory networks. PLoS Comput Biol 2013;9:e1003370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Schmidt BJ, Ebrahim A, Metz TO, et al. GIM3E: condition-specific models of cellular metabolism developed from metabolomics and expression data. Bioinformatics 2013;29:2900–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Zhao J, Zhu Y, Han J, et al. Genome-scale metabolic modeling reveals metabolic alterations of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a murine bloodstream infection model. Microorganisms 2020;8(11):1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Marcišauskas S, Ji B, Nielsen J. Reconstruction and analysis of a Kluyveromyces marxianus genome-scale metabolic model. BMC Bioinformatics 2019;20(1):551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. O’Brien EJ, Monk JM, Palsson BO. Using genome-scale models to predict biological capabilities. Cell 2015;161:971–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Seif Y, Monk JM, Mih N, et al. A computational knowledge-base elucidates the response of Staphylococcus aureus to different media types. PLoS Comput Biol 2019;15:1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Nogales J, Mueller J, Gudmundsson S, et al. High-quality genome-scale metabolic modelling of Pseudomonas putida highlights its broad metabolic capabilities. Environ Microbiol 2020;22:255–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Broddrick JT, Rubin BE, Welkie DG, et al. Unique attributes of cyanobacterial metabolism revealed by improved genome-scale metabolic modeling and essential gene analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:E8344–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. van’t Hof M, Mohite OS, Monk JM, et al. High-quality genome-scale metabolic network reconstruction of probiotic bacterium Escherichia coli Nissle 1917. BMC Bioinformatics 2022;23:566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Kaynar B, Uzuner D, Çakır T. Reconstruction and analysis of a genome-scale metabolic model for the gut bacteria Prevotella copri. Biochem Eng J 2023;196:108947. [Google Scholar]

- 135. Wodke JAH, Puchałka J, Lluch-Senar M, et al. Dissecting the energy metabolism in Mycoplasma pneumoniae through genome-scale metabolic modeling. Mol Syst Biol 2013;9:653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Dreyfuss JM, Zucker JD, Hood HM, et al. Reconstruction and validation of a genome-scale metabolic model for the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa using FARM. PLoS Comput Biol 2013;9:e1003126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Kim M, Sang Yi J, Kim J, et al. Reconstruction of a high-quality metabolic model enables the identification of gene overexpression targets for enhanced antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Biotechnol J 2014;9:1185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Österlund T, Nookaew I, Bordel S, et al. Mapping condition-dependent regulation of metabolism in yeast through genome-scale modeling. BMC Syst Biol 2013;7:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Minato Y, Gohl DM, Thiede JM, et al. Genomewide assessment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis conditionally essential metabolic pathways. mSystems 2019; 25;4(4):e00070–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Mol V, Bennett M, Sánchez BJ, et al. Genome-scale metabolic modeling of P. thermoglucosidasius NCIMB 11955 reveals metabolic bottlenecks in anaerobic metabolism. Metab Eng 2021;65:123–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Olin-Sandoval V, Yu JSL, Miller-Fleming L, et al. Lysine harvesting is an antioxidant strategy and triggers underground polyamine metabolism. Nature 2019;572:249–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Jijakli K, Jensen PA. Metabolic modeling of Streptococcus mutans reveals complex nutrient requirements of an oral pathogen. mSystems 2019;4(5):e00529–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Metz ZP, Ding T, Baumler DJ. Using genome-scale metabolic models to compare serovars of the foodborne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS One 2018;13:e0198584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Weaver DS, Keseler IM, Mackie A, et al. A genome-scale metabolic flux model of Escherichia coli K-12 derived from the EcoCyc database. BMC Syst Biol 2014;8:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Brown SA, Palmer KL, Whiteley M. Revisiting the host as a growth medium. Nat Rev Microbiol 2008;6:657–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Abu Kwaik Y, Bumann D. Microbial quest for food in vivo: ‘nutritional virulence’ as an emerging paradigm. Cell Microbiol 2013;15:882–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Lobel L, Sigal N, Borovok I, et al. Integrative genomic analysis identifies isoleucine and CodY as regulators of Listeria monocytogenes virulence. PLoS Genet 2012;8:e1002887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Peyraud R, Cottret L, Marmiesse L, et al. Control of primary metabolism by a virulence regulatory network promotes robustness in a plant pathogen. Nat Commun 2018;9:418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Schoen C, Kischkies L, Elias J, et al. Metabolism and virulence in Neisseria meningitidis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2014;4:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Großeholz R, Koh C-C, Veith N, et al. Integrating highly quantitative proteomics and genome-scale metabolic modeling to study pH adaptation in the human pathogen Enterococcus faecalis. NPJ Syst Biol Appl 2016;2:16017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Jansma J, El Aidy S. Understanding the host-microbe interactions using metabolic modeling. Microbiome 2021;9:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Ates O, Oner ET, Arga KY. Genome-scale reconstruction of metabolic network for a halophilic extremophile, Chromohalobacter salexigens DSM 3043. BMC Syst Biol 2011;5:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Enuh BM, Nural Yaman B, Tarzi C, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and genome-scale metabolic modeling of Chromohalobacter canadensis 85B to explore its salt tolerance and biotechnological use. Microbiology 2022;11:e1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Ventosa A, Nieto JJ. Biotechnological applications and potentialities of halophilic microorganisms. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 1995;11:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Hasdemir D, Hoefsloot HCJ, Westerhuis JA, et al. How informative is your kinetic model? Using resampling methods for model invalidation. BMC Syst Biol 2014;8:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]