Abstract

The quality (color, tenderness, juiciness, protein content, and fat content) of poultry meat is closely linked to age, with older birds typically exhibiting increased intramuscular fat (IMF) deposition. However, specific lipid metabolic pathways involved in IMF deposition remain unknown. To elucidate the mechanisms underlying lipid changes, we conducted a study using meat geese at 2 distinct growth stages (70 and 300 d). Our findings regarding the approximate composition of the meat revealed that as the geese aged 300 d, their meat acquired a chewier texture and displayed higher levels of IMF. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was employed for lipid profiling of the IMF. Using a lipid database, we identified 849 lipids in the pectoralis muscle of geese. Principal component analysis and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis were used to distinguish between the 2 age groups and identify differential lipid metabolites. As expected, we observed significant changes in 107 lipids, including triglycerides, diglycerides, phosphatidylethanolamine, alkyl-glycerophosphoethanolamine, alkenyl-glycerophosphoethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylinositol, lysophosphatidylserine, ceramide-AP, ceramide-AS, free fatty acids, cholesterol lipids, and N-acyl-lysophosphatidylethanolamine. Among these, the glyceride molecules exhibited the most pronounced changes and played a pivotal role in IMF deposition. Additionally, increased concentration of phospholipid molecules was observed in breast muscle at 70 d. Unsaturated fatty acids attached to lipid side chain sites enrich the nutritional value of goose meat. Notably, C16:0 and C18:0 were particularly abundant in the 70-day-old goose meat. Pathway analysis demonstrated that glycerophospholipid and glyceride metabolism were the pathways most significantly associated with lipid changes during goose growth, underscoring their crucial role in lipid metabolism in goose meat. In conclusion, this work provides an up-to-date study on the lipid composition and metabolic pathways of goose meat and may provide a theoretical basis for elucidating the nutritional value of goose meat at different growth stages.

Key words: fatty acid, goose, intramuscular fat, lipidomics, meat quality trait

INTRODUCTION

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO-STAT, 2021), China accounts for 95.8% of global goose meat production, making it the largest producer and consumer of goose meat worldwide. Goose meat in China has long been recognized for its high-quality proteins and fatty acids, providing consumers with essential amino acids and unsaturated fatty acids (Cui et al., 2015). In general, meat geese are slaughtered and marketed for approximately 70 d, which can strike a balance between ideal taste and feeding cost. However, in certain regions of China, there is a preference for meat geese that are over 300-day-old. This preference is rooted in the belief that the flavor of goose meat gradually improves with age, resulting in superior taste after cooking. This phenomenon can be attributed to the deposition of intramuscular fat (IMF), which is different from the fat accumulation in the subcutaneous and abdominal areas. The increase in IMF gives meat products a richer taste and nutrients, which generally occur as birds age (Yu et al., 2020). Recent studies have demonstrated that compared with 70-day-old goose meat, 120-day-old goose meat exhibits significant increases in protein and IMF deposition (Weng et al., 2021). Similarly, in chicken breasts, the IMF content increases with age (Baéza et al., 2012).

It is widely recognized that the IMF distributed between the muscle fibers of skeletal muscle plays a vital role in storing triglycerides and phospholipids (Katsumata, 2011), contributing to the tenderness, taste, juiciness, palatability, and other unique characteristics of meat (Wen et al., 2020). Research has shown that lamb meat with high IMF content exhibits a rich taste, whereas lamb meat with low IMF content has a poor texture and contains fewer lipid molecules (Bravo et al., 2018), such as triglycerides, diglycerides, and phospholipids. Lipid molecules, which are key components of meat and vital functional substances in the body, initiate a cascade of physiological and biochemical processes. Lipids serve as essential precursors for flavor formation, enhancing the taste and flavor of meat through the production of various volatile compounds via biochemical reactions, such as oxidation and Maillard reactions (Khan et al., 2015). Moreover, the IMF serves as the primary reservoir for polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) within muscles. Aldehydes produced by PUFAs during heating and oxidation contribute to the improvement in meat quality characteristics (Li et al., 2021a). Unheated and unoxidized PUFAs maintain their intact carbon chain structure and exert their biological activity at the cellular level, thereby influencing human health (Djuricic and Calder, 2021). These effects are recognized for their roles in preventing cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, regulating blood lipid metabolism, and suppressing inflammatory responses (Mensink et al., 2003; Sokoła et al., 2018).

To achieve optimal taste, poultry muscle tissues must maintain an IMF level of <0.5% (Wen et al., 2020). Insufficient IMF content leads to reduced meat tenderness and juiciness. However, the impact of fluctuations in IMF abundance on internal lipid molecular composition remains largely unknown, and the underlying mechanisms are yet to be comprehensively understood. Lipidomic analysis using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) has emerged as a valuable approach for identifying and quantifying a wide range of molecular lipid species (Han and Gross, 2022). This technique facilitates the comprehensive exploration of lipid molecules and enables the comparison of their changes under different physiological states, thereby identifying the key lipid markers involved in metabolic pathways (Shevchenko and Simons, 2010; Yang and Han, 2016). With advancements in detection technology, lipid sequencing analysis has become well-established in meat research. LC-MS has been widely used to identify lipid markers during meat storage, slaughter, and aging (Li et al., 2022). Additionally, it has demonstrated efficacy in distinguishing different livestock and poultry breeds and geographical origins (Zhang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022). Notably, LC-MS also exhibits excellent performance in identifying adulterants in meat and dairy products (Trivedi et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2020).

In this study, we focused on Zhedong white geese (70 and 300 d of age) as the subject of our investigation. We aimed to examine the meat quality attributes of their breast muscles, compare IMF levels between the 2 age groups, and conduct a comprehensive lipid profile analysis of the IMF. By employing widely targeted lipidomics technology, we can gain insights into the overall lipid transformation process in goose meat during growth. This study contributes to a holistic understanding of the meat quality characteristics and lipid alterations in goose meat across different growth stages. It offers novel strategies for elucidating potential metabolic pathways and enhancing our understanding of the nutritional value of goose meat, thus expanding existing knowledge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Handling

The Zhejiang white geese required for lipidome sequencing and meat quality trait determination were from Changzhou Siji Poultry Industry Co., Ltd, including six 70-day-old geese (3.26 ± 0.17 kg) and six 300-day-old geese (4.45 ± 0.11 kg) (half male and half female). Several 1-day-old goslings were randomly selected from a group of purebred families and grown in a controlled environment for 28 d. The 1-day-old birds were housed at an ambient temperature of 32°C, which was then gradually lowered to ensure the most comfortable growing environment. At the age of 28 d, 60 healthy goslings with similar body weights (0.89 ± 0.08 kg) were selected and divided into 6 groups. During the experiment, all birds met the following feeding standards: each group was fed in pens with a density of 5 geese per square meter, and the pens were equipped with a free-moving area and a water pool. Birds were exposed to natural light and temperature with free access to water and food. Each poultry group was fed the same amount. All geese were fed the same commercial diet, whose ingredients and chemical composition are shown in Table S1, according to the national standards of the R.P. China-Zhedong White goose (GB/T 36178–2018). To ensure that the geese of different ages were sampled on the same day, the rearing process was divided into 2 steps. In the first part of the experiment, 60 goslings were fed according to the above-mentioned experimental procedure, and the second part of the experiment was initiated when they were 230-day-old. Similarly, the second part of the experiment required selecting 60 goslings again from several 1-day-old goslings and then feeding them for 70 d according to the above-mentioned feeding process. Errors caused by different sampling times during the experiment were avoided. All experimental procedures performed in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Committee of the Yangzhou University (Permit Number: YZUDWSY, Government of Jiangsu Province, China).

Sample Collection

The experimental collection and analysis were completed between October 2022 and November 2022. The selected geese were fasted for 1 h, given free access to water, and then sent to the laboratory within 4 h. They were weighed separately half an hour before slaughter. All geese were euthanized by cutting the neck artery. The skin of the breast muscle of each poultry was removed, and approximately 5 g of sample was obtained from the left pectoralis (pectoralis major) and collected in a frozen tube. Samples from each bird were kept individually, and no samples were pooled. After sample collection, all obtained samples were stored at -80°C for lipidomic analysis. The right pectoral muscle (pectoralis major) of geese was used to assess the physical quality of the meat. Muscles of 2 × 1 × 1 cm3 were collected for hematoxylin–eosin staining and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde.

HE Staining and Measurement of Meat Quality Traits

Before staining, eosin alcohol and hematoxylin solutions were configured for hematoxylin–eosin staining of the muscle cross-sections. The paraffin sections were placed in xylene and ethanol solutions of different concentrations for dewaxing. Subsequently, the samples were soaked in distilled water for 5 min and stained with a hematoxylin solution for 5 min. The slides were then rinsed with distilled water for 30 s, stained with eosin for 1 min, and rinsed again with distilled water. Finally, sections were subjected to gradient ethanol dehydration, dimethylbenzene transparency, and sealing. The stained muscle samples were analyzed using a Leica Autostainer XL (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), and an image analysis system (Image-Pro Plus, Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD) was used to calculate the fiber diameter and cross-sectional area.

The collected right pectoral muscle was separated into 100 g to evaluate the physical quality of the meat. The approximate composition of the pectoralis muscle was examined using the FoodScan Meat Analyzer (Foss, Hilleroed, Denmark). First, the visible fat, meat film, and connective tissue on the surface of the breast muscle sample were removed, and the sample (100 g) was ground into a paste using a high-speed centrifugal grinder (Teste, Wuhan, China) and placed in a metal cup. The mushy sample in the cup was carefully examined to remove the fine fat and connective tissue. Finally, the water and intermuscular fat content of the samples were detected via FoodScan Meat Analyzer (Anderson, 2007).

Preparation of Samples

From the 5 g sample obtained, 20 mg was isolated for lipid extraction. The sample was thawed, stored at −80°C on an ice block, transferred into a 2-mL Eppendorf tube, and the corresponding number on the tube wall was marked. First, 1 mL of lipid extract and 2 zirconia beads were added to an Eppendorf tube and crushed into a homogenate using a ball mill (MM400; Retsch, Haan, Germany). The steel ball was then removed, and the Eppendorf tube was placed in a multitube vortex oscillator (MIX-200, Shanghai, China) and vortexed for 2 min. After adding 200 uL of ultra-pure water to mix the sample, it was vortexed again for 1 min and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C (5424R, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Finally, 200 μL of the supernatant was taken for concentration and drying, and the dried powder was dissolved with 200 μL of lipid reconstitution solution and stored at −80°C for subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis.

Lipidomic Analysis

Lipidomic assays were performed by Metawell Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). The sample extracts were analyzed using a UPLC-ESI-MS/MS system (UPLC, ExionLC AD, https://sciex.com.cn/; MS, QTRAP 6500+ System, https://sciex.com/). The size of the chromatographic column (Thermo Accucore C30, Waltham, MA) was 2.6 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm i.d., and the temperature was maintained at 45°C. The sample entered from the autosampler, and each injection volume was 2 uL. After the sample entered the instrument, gradient elution was performed under the action of mobile phases A (acetonitrile/water: 60/40, v/v) and B (acetonitrile/isopropanol: 10/90, v/v), and the flow rate was kept at 0.35 mL/min. The elution condition changed according to the change in time: A/B was 80:20(V/V) at 0 min, 40:60(V/V) at 4 min, 5:95 at 15.5 min (V/V), 80:20(V/V) at 17.5 min, and 80:20(V/V) at 20 min. The effluent was alternately connected to an ESI-triple quadrupole linear ion trap (QTRAP)-MS.

Samples were collected via tandem mass spectrometry. The QTRAP 6500+ LC-MS/MS System controlled by Analyst 1.6.3 software (Sciex) was equipped with an ESI Turbo Ion-Spray interface, which can operate in 2 different ion modes, thus realizing the linear ion trap and triple quadrupole (QQQ) scans. The operating standards of the ESI source were as follows: the pressures of ion source gas 1, ion source gas 2, and curtain gas were 45 psi, 55 psi, and 35 psi, respectively, and the temperature of the ion source was kept at 500°C. The MS voltages for positive and negative ion modes were 5,500 V and −4,500 V. Approximately 10 μmol/L and 100 μmol/L polypropylene glycol solutions were used for instrument calibration and mass calibration in QQQ and linear ion trap modes, respectively. In QQQ, each ion pair was scanned and detected based on optimized declustering potential and collision energy. The nitrogen pressure in the QQQ mode was set to 5 psi. The multiple reaction monitoring mode of QQQ mass spectrometry was highly conducive to the quantitative analysis of lipids. In the monitoring mode, the quaternary rod first screened the precursor ions (parent ions) of the target substance and excluded the ions corresponding to other molecular weight substances to preliminarily eliminate interference. The precursor ions were ionized by the collision chamber and then broken to form a large number of fragmented ions. The fragmented ions were then filtered through a triple quadrupole to select the required characteristic fragment ion, which excluded interference from nontarget ions. Qualitative analysis was based on the precursor ions (parent ions, Q1), characteristic fragment ions (daughter ions, Q3), and the retention time of the target substance. This method has a high sensitivity and good repeatability. After obtaining the lipid mass spectrometry analysis data for the different samples, the peak areas of all chromatographic peaks were integrated, and 51 lipid isotopes were obtained. Each lipid subclass contained at least 1 to 2 isotopes as internal standards for quantitative analysis.

Mass spectral data were processed using Analyst 1.6.3. The lipids in the samples were qualitatively analyzed via mass spectrometry, according to the lipid database built by Metwell Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The MultiQuant software was used to correct the chromatographic peaks detected in different samples for each substance to ensure the accuracy of quantification.

Statistical and Bioinformatics Analyses

The experimental procedure is illustrated in Figure 1. SPSS software (version 26.0) was used to analyze the data between the 2 groups of samples, test the homogeneity of variance, and analyze the significance of differences using Duncan's multiple-range test after meeting the requirements. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the statistical function prcomp in R (www.r-project.org). Multidimensional data can be converted into several important variables that aid in displaying data aggregation and dispersion more intuitively. Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was performed using the MetaboAnalystR package OPLSR.Anal function in R software. Data were log-transformed (log2) and mean-centered prior to OPLS-DA. Differential lipids were screened according to variable importance in projection (VIP > 1), Fold Change (FC ≥ 2 and FC ≤ 0.5), and P-value (P < 0.05) of univariate analysis, and VIP value was extracted from OPLS-DA results. The lipid content data were processed via unit variance scaling. A heat map was drawn using the R software complex heatmap package, and hierarchical cluster analysis was performed on the accumulation pattern of lipids among different samples. The Corrplo package was used to perform Pearson's correlation analysis of the differential lipids, and a correlation chord diagram was drawn. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) compound database (http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/compound/) and the MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/) platforms were used to map and differentiate lipids related metabolic pathways. Topological analyses were performed on these significantly different lipids to calculate the p-values and pathway effects. Associated pathways with P < 0.05 and impact value > 0.1 were significant, and the metabolic pathways mapped were subjected to metabolite set enrichment analysis.

Figure 1.

Lipid identification flow chart of intramuscular fat in goose meat.

RESULTS

Meat Quality Traits of Muscle

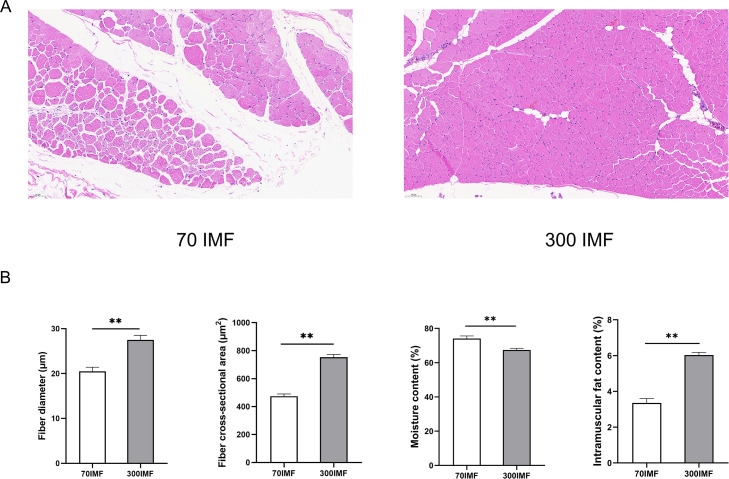

We conducted a comprehensive study of the muscle fibers, IMF content, and approximate composition of goose pectoral muscles (70IMF and 300IMF) to analyze the dynamic changes in goose meat across different growth stages (Figure 2). Over the period of 70 to 300 d, there was a substantial increase in both the muscle fiber diameter and the cross-sectional area of goose meat (P < 0.05). This growth was accompanied by fat accumulation in the muscles (Figure 2A). Notably, the IMF content of the 300-day-old goose pectoral muscle was 43.8% higher than that of the 70-day-old goose pectoral muscle (P < 0.05) (Figure 2B). However, the moisture content of goose meat exhibited an inverse relationship with IMF content, with higher levels observed at 70 d (P < 0.05) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Pectoral muscle phenotype of 70-d and 300-d geese. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining (25.0×). Red arrow indicates the location of the IMF in the pectoral muscle of the 300-d geese. (B) Physical properties of goose meat. The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). In the histogram, * indicates P < 0.05 and ** indicates P < 0.01.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Goose Meat Lipids at Different Growth Stages

The lipid profiles of the samples from the 70IMF and 300IMF groups were characterized and analyzed using UPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Additionally, multivariate visual analysis of the detected liposome data was performed (Figure 3A, Supplementary Data S1). This comprehensive analysis identified 849 lipids, which were further categorized into 6 distinct classes: glycerides (44.64%), glycerophospholipids (42.41%), sphingolipids (8.01%), fatty acyls (4.36%), sterol lipids (0.47%), and pregnenolone esters (0.12%). Glycerides and glycerophospholipids were the predominant components in the IMF of goose meat. Furthermore, to enhance our understanding of lipid molecules, we conducted a more detailed classification of lipid classes, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of lipid functions and metabolic pathways. According to lipid classification standards, lipid molecules are classified into various types and species. These include 2 subclasses of fatty acids (acylcarnitine [CAR] and free fatty acid [FFA]), 4 subclasses of glycerides (diglyceride [DG], ether-linked diacylglycerol, monoglycerides, and triglycerides [TG]), 18 subclasses of glycerophospholipids (N-acyl-lysophosphatidylethanolamine [LNAPE], lysophosphatidic acid, alkyl-lysophosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidic acid, lysophosphatidylethanolamine, alkenyl-lysophosphatidylethanolamine, lysophosphatidylethanolamine, lysophosphatidylserine [LPS], phosphatidic acid, phosphati- dylcholine [PC], alkyl-glycerophosphocholines, phosphatidylethanolamine [PE], alkyl-glycerophosphoethanolamine [PE-O], alkenyl-glycerophosphoethanolamine [PE-P], phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol [PI], phosphatidylmethanol, and phosphatidylserine [PS]), 1 subclass of pregnenolone esters (coenzyme Q), 10 subclasses of sphingolipids (ceramide-ADS, ceramide-AP [Cer-AP], ceramide-AS [Cer-AS], ceramide-NDS, ceramide-NP, ceramide-NS, 1-phosphoceramide, glycosphingolipid-AP, glycosphingolipid-NS, and sphingomyelin), and 2 subclasses of sterol lipids (cholesteryl lipids[CE] and bile acids).

Figure 3.

Lipid identification of goose meat (n = 6). (A) Types and quantities of lipids in intramuscular fat of goose meat. (B) Lipid class percentage of goose meat (70IMF group). (B) Lipid class percentage of goose meat (300IMF group).

In goose meat, TG lipid molecules were the most abundant, accounting for 37.10% of the total. PE constituted 7.89% of lipid molecules, making it the most prevalent phospholipid. Furthermore, to examine the number of lipid classes present in goose meat of different ages, we identified the number of lipids in samples from the 70IMF and 300IMF groups, which amounted to 838 and 798 lipid molecules, respectively (Figures 3B and 3C). Consistent with the aforementioned findings, the glyceride class remained the most abundant lipid molecule in both the 70IMF (45.11%) and 300IMF (47.12%) groups, with no significant differences observed between the 2 sample groups.

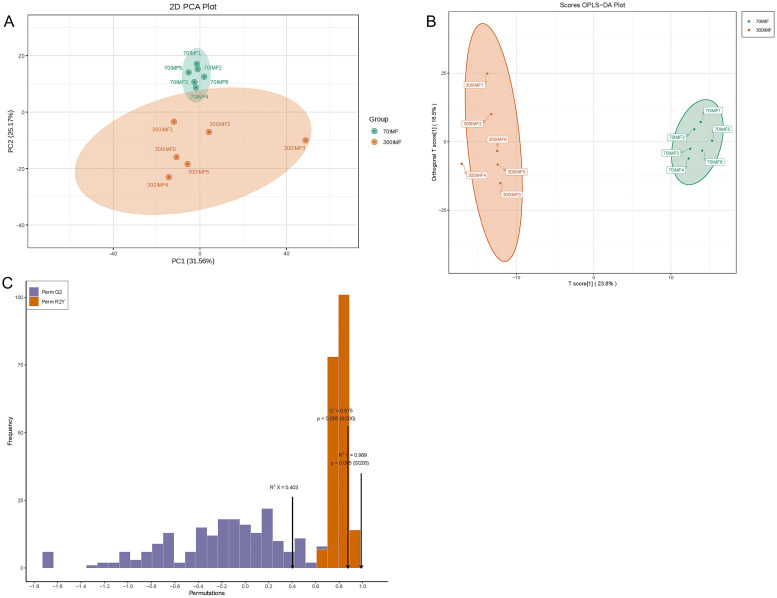

Multivariate Data Analytics for Lipids

Before identifying the differential lipid molecules, it was necessary to conduct unsupervised PCA on samples from the 70IMF and 300IMF groups. This analysis allowed us to observe the variability between the different treatment groups and within the samples of each group. As shown in Figure 4A, the separation between the 2 sample groups was more pronounced. The first principal component accounted for 31.56% of the variance in the original dataset, whereas the second principal component accounted for 25.17%. Six samples from the 70IMF group exhibited good repeatability and high data similarity. However, the samples in the 300IMF group showed a low degree of aggregation, with the No. 3 sample clearly distinguished from the other 5 samples in the group. To maximize the differentiation between the 70IMF and 300IMF group samples, we employed a supervised OPLS-DA model for data analysis. OPLS-DA is a multivariate statistical analysis method that operates in supervised mode. Partial least-squares regression was used to establish a relationship model between metabolite expression and sample categories, enabling the prediction of sample categories. The OPLS-DA score plot (Figure 4B) demonstrated a significant difference in the lipid composition between the 2 sample groups, effectively distinguishing between geese of different ages. The reliability of the analysis was verified using the model's predicted parameters R2X, R2Y, and Q2. As depicted in Figure 4C, the results for R2Y (0.989, P < 0.005) and Q2 (0.875, P < 0.005) indicate the model's reliable predictive ability and stability, without overfitting issues. Both PCA and OPLS-DA models revealed comprehensive lipid changes throughout the growth process.

Figure 4.

Principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) of goose meat lipid. (A) Plot of PCA scores for 70IMF and 300IMF (n = 6). (B) Plot of OPLS-DA scores for 70IMF and 300IMF (n = 6). (C) OPLS-DA score plots of the lipids.

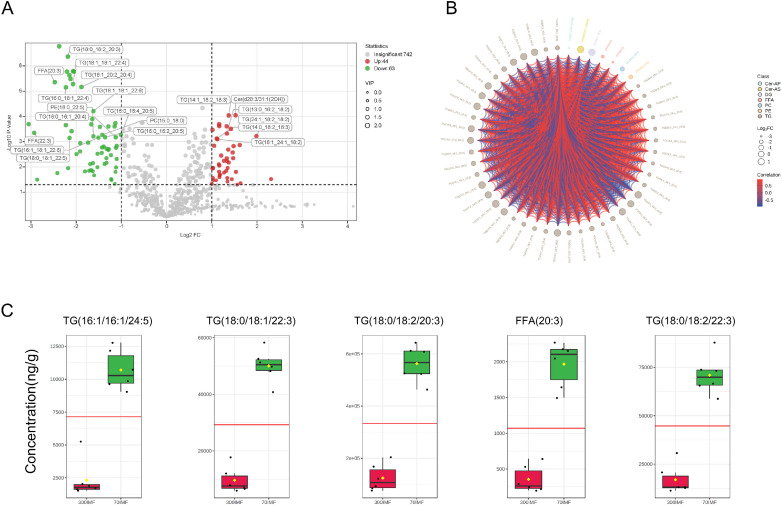

Identification of Total Differential Lipid Molecules

Based on the abovementioned OPLS-DA results, we selected lipid molecules with VIP > 1, Log2FC ≥ 1 or ≤ −1 and P < 0.05 as differential metabolites for downstream data visualization analysis. The volcano plot effectively revealed the differences in lipids between the 2 sample groups (Figure 5A). Among these, labels were assigned to the top 20 lipid molecules with the lowest P values. From the volcano plot results, 107 lipid molecules that significantly changed during the growth of geese were identified. Moreover, more lipids were upregulated in the 70-day-old goose IMF. In comparison to the 70IMF group, 44 lipids were upregulated in the 300IMF group, including 34 TG, 4 DG, 3 Cer-As, 1 FFA, 1 CE, and 1 PC (P < 0.05) (Figure 5A, Supplementary Data S2). Additionally, the 70IMF group displayed upregulation of 63 lipids, including 33 TG, 6 DG, 6 PE, 6 PC, 4 PE-O, 3 FFA, 1 Cer-AP, 1 LPS, 1 PE-P, 1 PI, and 1 LNAPE (P < 0.05) (Figure 5A, Supplementary Data S3). Notably, although TG molecules were upregulated in both groups, PE, PE-O, and PC were predominantly upregulated in the 70IMF group. The contents of PE, PE-O, and PC in the IMF gradually decreased with age, exhibiting a significant negative correlation with goose growth (P < 0.05). Lipid molecules within the same subclass typically possess similar physiological functions and molecular characteristics and play comparable roles in the growth process of geese. We generated a hierarchical clustering heatmap of the differential metabolites using all the differential lipids (Figure S1). The hierarchical clustering tree within the heatmap clearly distinguishes samples from the 70IMF and 300IMF groups. Furthermore, the correlation chord plot demonstrated stronger similarity among lipid molecules of the same subclass than among those of different subclasses (Figure 5B). In the chord diagram, red indicates a positive correlation and blue indicates a negative correlation, and the intensity of the color represents the strength of the correlation. TG was mostly negatively correlated with PE and PC, whereas DG was also negatively correlated with PE and PC. In contrast, PE and PC showed significant positive correlations.

Figure 5.

Lipid markers in goose meat at different growth stages. (A) Volcano map of differential lipids. Under the triple screening conditions of VIP + FC + P-value, the abscissa represents the fold change (log2FoldChange), the vertical axis indicates the significance level of the difference (−log10P-value), and the size of the dot represents the VIP value. (B) Candidate lipids used as biomarkers.

VIP scoring was used to identify the representative lipids that could serve as potential biomarkers of species segregation. We selected the 5 lipid molecules with the highest VIP scores and significantly different abundances as biomarkers. Among these candidate biomarkers, TG (18:0_18:1_22:3), TG (18:0_18:2_20:3), TG (18:0_18:2_22:3), FFA (20:3), and TG (16:1_16:1_24:5) were all upregulated in the IMF of 70-day-old geese compared with that of 300-day-old geese (Figure 5C). These marker metabolites allowed for differentiation between 70-day-old and 300-day-old geese.

Distribution of Fatty Acids at Different Sites in Lipid Molecules

Fatty acids bound to the side chains of lipid molecules are easily attacked by hydrolytic enzymes to form free fatty acids or are oxidized to release various volatile substances. Figure 6A presents the distribution of fatty acid chain lengths at the 3 sites of the 67 TG molecules. Upregulation indicates high lipid abundance in 300-day-old geese, whereas downregulation signifies high lipid levels in 70-day-old geese. Our findings demonstrated that advancing age promotes an increase in longer fatty acid chains at the sn-1 site of TG molecules, particularly in 300-day-old goose meat (P < 0.05) (Figure 6A). Conversely, the fatty acid composition at the sn-1 site of the TG molecules remained relatively stable in the 70-day-old goose meat, primarily consisting of C16 and C18 fatty acids. Moreover, the sn-1 site of TG exhibited high saturation, leading to the accumulation of abundant C16:0 and C18:0 fatty acids in 70-day-old goose meat (P < 0.05) (Figure 6B). In contrast, the sn-3 site of TG displayed more polyunsaturated fatty acids (Figure 6B). Notably, no significant variations in fatty acid chain length were observed at the sn-2 site of TG among goose meats of different ages. However, a high proportion of unsaturated fatty acids, particularly C18:1, was detected (P < 0.05) (Figure 6B). Overall, the sn-1 site of TG was predominantly composed of saturated fatty acids, whereas the sn-3 site was enriched with polyunsaturated fatty acids. Furthermore, the sn-2 site of TG exhibited C18:1 enrichment, whereas C16:0 and C18:0 were predominantly distributed at the sn-1 site in 70-day-old geese.

Figure 6.

Length and saturation of side chain fatty acids of TG, PC, and PE lipids. (A) Changes in the length of side chain fatty acids of 67 differential TG molecules. Upregulation indicates high lipid abundance in 300-day-old geese, while downregulation signifies high lipid levels in 70-day-old geese. (B) Saturation degree of side chain fatty acids of TG molecules. (C) Saturation degree of side chain fatty acids of PE and PC molecules.

Consistent with these findings, we analyzed fatty acid saturation in 2 classes of phospholipid molecules: PE and PC. Our results indicated that the fatty acids at the sn-1 site of these phospholipids were primarily saturated, whereas PC showed a high 18:0 fatty acid content (P < 0.05). Conversely, the sn-2 sites of both PE and PC contained a high proportion of unsaturated fatty acids (Figure 6C).

Metabolic Pathway Analysis of Differential Lipids

Metabolic pathway analysis plays a crucial role in understanding the metabolic processes of lipid molecules in the IMF across different growth stages in geese. To elucidate the disparities in lipid metabolism within goose IMF of varying ages, we mapped 107 marker metabolites to the KEGG database (http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/compound/), resulting in the identification of 25 metabolic pathways (Figure 7A, Supplementary Data S4). To gain deeper insights into the key pathways influencing lipid metabolism in goose meat, we employed the MetaboAnalyst 5.0 platform (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/) to perform topology analysis on these differentially abundant lipids, calculating both the P-value and pathway influence. Significance was attributed to correlation pathways with P < 0.05 and effect value > 0.1. We identified 9 metabolic pathways associated with lipid changes in goose meat (Figure 7B, Supplementary Data S5). These pathways, ranked based on the p-value and impact value derived from topological analysis, included glycerophospholipid metabolism, glycerolipid metabolism, linoleic acid metabolism, alpha-linolenic acid metabolism, glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor biosynthesis, phosphatidylinositol signaling system, inositol phosphate metabolism, arachidonic acid metabolism, and biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids. Among these metabolic pathways, glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism were the most significant pathways influencing the transformation of lipid molecules during goose growth (Figures S2 and S3). Notably, TG, PE, PC, 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycerol, and dihomo-gamma-linolenate lipids have emerged as key players in these pathways.

Figure 7.

Metabolic pathway analysis of differential lipids. (A) KEGG enrichment map of differential lipids. The abscissa indicates the Rich Factor corresponding to each pathway, the ordinate indicates the pathway name (sorted by P-value), and the color of the point reflects the P-value size. (B) Key metabolic pathways involved in lipid changes. Metabolic pathway analysis. The topological analysis of these significantly different lipids was performed using the MetaboAnalyst 5.0 platform, and the P-value and pathway influence were calculated. Correlation pathways with P < 0.05 and effect value > 0.1 were defined as significant.

DISCUSSION

Meat Quality Traits of Muscle

Compared to young geese, meat geese aged over 300 d are highly favored and sought after by Chinese consumers. This phenomenon is speculated to be associated with changes in IMF content, which gradually accumulates in goose meat as it ages. Therefore, we compared meat quality traits between 70-day-old and 300-day-old geese. We observed a high IMF content in 300-day-old goose meat, which is preferred by consumers. In previous study, enzymes and genes regulating fatty acid synthesis and transport were found to be involved in IMF deposition (Luo et al., 2022; Mao et al., 2022). IMF synthesis is intricately linked to fatty acid metabolism and can be achieved through the expression of specific fatty acid-related genes in adipocytes (Luo et al., 2022). Unlike other meat animals, poultry muscle exhibits an extremely low IMF content, with goose meat typically ranging from 3% to 5%. Although not readily visible to the naked eye, IMF deposition in muscles significantly affects meat tenderness, flavor, juiciness, and texture. Their sensory effects could not be disregarded. Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated a significant negative correlation between IMF and moisture content (Wen et al., 2020). Compared to 70-day-old goose meat, breast muscle water content significantly decreased in 120-day-old goose meat (Weng et al., 2021). These observations are consistent with our conclusions. With increasing age, 300-day-old geese exhibited elevated IMF content at the expense of moisture content. The diameter and cross-sectional area of muscle fibers were crucial factors affecting meat tenderness, with fiber thickness regulating the magnitude of muscle shear force (Roy and Bruce, 2023). Thicker muscle fibers contribute to a chewier texture, enhancing the flavor distribution. From a nutritional perspective, the 300-day-old goose meat provides consumers with a chewier texture.

Applications of Lipidomics

In recent years, the widespread application of lipidomics in poultry science has provided insights into the mechanisms of lipid changes and identification of lipid metabolites associated with meat quality traits. Phenotypic analysis revealed differences in IMF content among goose meat of different age groups, with 300-day-old geese exhibiting a significantly high IMF content. However, little is known regarding how IMF deposition progressively alters the lipidome of goose meat with age. Hence, this study aimed to characterize the lipidome of 70-d and 300-d geese meat. Using the UPLC-ESI-MS/MS platform, 849 lipid molecules belonging to 37 subclasses were identified from both positive and negative ionization patterns. The amounts of these lipids were comparable to those previously reported in pork and chicken meat studies (Mi et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). Evaluating the biological functions of lipid molecules at the subclass level alone is insufficient to reveal comprehensive changes. The results of the OPLS-DA model demonstrated a significant disparity in the lipid composition of goose meat between the 70-d and 300-d samples. As expected, 107 lipids, including TG, DG, PE, PE-O, PE-P, PC, PI, LPS, Cer-AS, Cer-AP, FFA, CE, and LNAPE, exhibited significant alterations during goose growth.

Contribution of Fatty Acyls to Goose Meat

Except for a minor portion of fatty acids existing in the form of free fatty acids, the majority of fatty acyl molecules play a fundamental role in the lipid structure (Vanni et al., 2019). They participate in glycerol backbone formation through esterification, generating GP and GL molecules, and interacting with other complex lipids, influencing various aspects, such as food texture, formation of flavor compounds, and nutritional value (Mottram, 1998). In their esterified states, they are typically regarded as precursors of aromatic compounds. For instance, compounds formed after the oxidation of linoleic and linolenic acids impart many characteristic flavors to food items (Shahidi and Hossain, 2022). Furthermore, fatty acids frequently combine with lipid molecules at different sites in the form of saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, or polyunsaturated fatty acids, resulting in diverse combinations that lead to the functional diversification of lipid molecules. Lipid molecules containing polyunsaturated fatty acids often exhibit pronounced nutritional and physiological benefits (Djuricic and Calder, 2021). Consequently, the presence of fatty acids positively influences the development of the flavor and nutritional value of goose meat.

Contribution of Phospholipid Molecules to Goose Meat

Phospholipids are essential organic compounds that play a crucial role in various biological processes. They actively participate in vital activities, such as material metabolism, cell growth, and information transduction and recognition (Shevchenko and Simons, 2010; Han and Gross, 2022). Moreover, phospholipid molecules have a unique impact on meat flavor formation (Khan et al., 2015). According to our current findings, goose meat exhibited an increased deposition of phospholipid molecules, including PE, PE-O, PI, and PC, at 70 d. This aligns with previous reports that the PE and PC contents in pork gradually decrease with age and IMF (Li et al., 2021c). Therefore, our conclusion may not fully support the preference of Chinese consumers, as 70-day-old geese contain more flavor-forming substances, which may not be desirable for 300-day-old geese. However, it is important to consider that meat flavor development is a complex process influenced by multiple factors, and further research is required to elucidate the differences between these 2 flavors. PC serves as the primary phospholipid responsible for storing fatty acids in muscle tissue, contributing to the overall health of meat. In addition to maintaining cell membrane integrity, PC also serves as a precursor for choline synthesis. Goose meat serves as a significant source of choline for consumers, and its consumption is beneficial for alleviating memory loss and neurodegenerative diseases (Enomoto et al., 2020). PE decomposition is the main cause of the increase in free fatty acids, which are essential for flavor formation during meat processing (Xu et al., 2008). Moreover, our results revealed a high abundance of unsaturated fatty acids at sn-2 sites in PE and PC. These findings provide evidence to meat enthusiasts that incorporating goose meat into the diet, particularly 70-day-old goose meat, can be advantageous for health. Furthermore, the formation of intramuscular lipid droplets is characterized by changes in PE, PC, and PS (Hörl et al., 2011), with the intracellular PC/PE ratio decreasing with the formation of lipid droplets. In line with this, we observed the downregulation of all differential PEs in 300-day-old goose meat, and a negative correlation was found between IMF and PE contents. Hence, our study supports the hypothesis that increased age suppresses PE content, while promoting the deposition of intramuscular lipid droplets and IMF.

Contribution of Glyceride Molecules to Goose Meat

Changes in glycerides are closely associated with the growth process of geese, including TG and DG. DG molecules, particularly sn-1,3-DG, have the potential to inhibit fat deposition and regulate serum lipid and glucose levels (Lee et al., 2020). This is attributed to the unique structure of DG, which leads to its utilization through a metabolic pathway distinct from that of triacylglycerols. Typically, TG molecules are the most abundant in animal skeletal muscle fat (Li et al., 2021b; Lv et al., 2023). Our study confirmed that TG was the most abundant lipid in both 70-d and 300-d goose meat, accounting for 37.59% and 39.35% of the total lipid content, respectively. While TG molecules exhibit the greatest differences between the 2 sample groups, their variations are primarily related to the formation of lipid droplets (Hilgendorf et al., 2019) and do not exhibit many physiological or biochemical functions. Therefore, our research primarily focused on fatty acids bound to the side chain sites of TG molecules, which are susceptible to hydrolysis by hydrolases to form free fatty acids, or undergo oxidation to release various volatile substances (Lien, 1994). In this study, unsaturated fatty acids were predominantly distributed at the sn-2 and sn-3 sites of TG, with the sn-3 site being the PUFA accumulation site. Generally, consumption of PUFA-rich meat is beneficial to human health (Sokoła et al., 2018). However, the presence of PUFAs in meat can accelerate the oxidation process, resulting in the deterioration of flavor, color, and nutritional value (Huang et al., 2012). This poses a significant challenge in meat storage.

Unlike polyunsaturation at the sn-3 site, the sn-2 site of the TG molecule accumulated a large amount of C18:1 in 70-day-old or 300-day-old geese. This finding aligns with recent studies on donkey meat, where abundant C18:1 was found at the sn-2 position of TG (Li et al., 2021b). The unique characteristics of the sn-2 site provide a stable environment for C18:1 and the fatty acids present at the external site prevent most attacks from hydrolytic enzymes. This facilitates fatty acids absorption by the body. Consistently, C18:1 has a positive effect on human health, including protecting cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health, preventing lipotoxicity, and promoting lipid droplet formation (Yki et al., 2021; Castillo et al., 2023). In this study, saturated fatty acids (C16:0 and C18:0) were enriched at the sn-1 position of TG, particularly in 70-day-old goose meat. This is similar to previous findings indicating that C16:0 is predominantly distributed in the external positions of the TG molecules (Liu et al., 2019). Pancreatic lipase selectively hydrolyzes fatty acids at the triglyceride external checkpoint to produce free fatty acids (Lien, 1994). Therefore, goose meat with saturated fatty acids distributed in the external positions of the TG is readily mobilized by the human body, thereby reducing the risk of fat accumulation and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

CONCLUSION

This is the first application of lipidomics to describe the lipid characteristics of goose meat at different growth stages. Overall, changes in liposomes revealed the effect of age on goose meat quality and revealed significantly different growth-related lipids and metabolic pathways, including glycerides and glycerophospholipids. These lipids play crucial roles in IMF deposition and development of a meaty flavor. Although the intrinsic role of differential lipids in goose meat quality and flavor warrants further validation, this study provides a comprehensive lipidomic result for assessing the nutritional value of goose meat and contributes to the understanding of lipid changes within goose meat IMF.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Modern Agro-Industry Technology Research System (grant number CARS-42-3), Jiangsu Agricultural Science and Technology Independent Innovation Fund Project (grant number CX (21)1001), Key and General Projects of Modern Agriculture in Jiangsu Province (grant number BE2022350), and Jiangsu Province Seed Industry Revitalization Unveiled Project (grant number JBGS [2021] 023).

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.psj.2023.103172.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Anderson S. Determination of fat, moisture, and protein in meat and meat products by using the FOSS FoodScan near-infrared spectrophotometer with FOSS artificial neural network calibration model and associated database: collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 2007;90:1073–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baéza E., Arnould C., Jlali M., Chartrin P., Gigaud V., Mercerand F., Durand C., Méteau K., Le E.B.D., Berri C. Influence of increasing slaughter age of chickens on meat quality, welfare, and technical and economic results. J. Anim. Sci. 2012;90:2003–2013. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo L.L., Barron L.J.R., Farmer L., Aldail N. Fatty acid composition of intramuscular fat and odour-active compounds of lamb commercialized in northern Spain. Meat Sci. 2018;139:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Q.J.I., Steinbaugh M.J., Fernández-Cárdenas L.P., Pohl N.K., Wu Z., Zhu F., Moroz N., Teixeira V., Bland M.S., Lehrbach N.J., Moronetti L., Teufl M., Blackwell T.K. An antisteatosis response regulated by oleic acid through lipid droplet-mediated ERAD enhancement. Sci. Adv. 2023;9:8917. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adc8917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.Y., Peng X.Y., Sun X., Pan L., Shi J.C., Gao Y., Lei Y.L., Jiang F., Li R.Z., Liu Y.F., Xu Y.J. Development and application of feature-based molecular networking for phospholipidomics analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022;70:7815–7825. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c01770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L.L., Wang J.F., Xie K.Z., Li A.H., Geng T.Y., Sun L.R., Liu J.Y., Zhao M., Zhang G.X., Dai G.J., Wang J.Y. Analysis of meat flavor compounds in pedigree and two-strain Yangzhou geese. Poult. Sci. 2015;9:2266–2271. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djuricic I., Calder P.C. Beneficial outcomes of omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on human health: an update for 2021. Nutrients. 2021;13:2421. doi: 10.3390/nu13072421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto H., Furukawa T., Takeda S., Hatta H., Zaima N. Unique distribution of diacyl-, alkylacyl-, and alkenylacyl-phosphatidylcholine species visualized in pork chop tissues by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry imaging. Foods. 2020;9:2–5. doi: 10.3390/foods9020205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO-STAT. 2021. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Livestock primary, https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#date/QCL.

- Han X., Gross R.W. The foundations and development of lipidomics. J. Lipid Res. 2022;63:100–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jlr.2021.100164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgendorf K.I., Johnson C.T., Mezger A., Rice S.L., Norris A.M., Demeter J., Greenleaf W.J., Reiter J.F., Kopinke D., Jackson P.K. Omega-3 fatty acids activate ciliary FFAR4 to control adipogenesis. Cell. 2019;179:1289–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hörl G., Wagner A., Cole L.K., Malli R., Reicher H., Kotzbeck P., Köfeler H., Höfler G., Frank S., Bogner-Strauss J.G., Sattler W., Vance D.E., Steyrer E. Sequential synthesis and methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine promote lipid droplet biosynthesis and stability in tissue culture and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:17338–17350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.234534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumata M. Promotion of intramuscular fat accumulation in porcine muscle by nutritional regulation. Anim. Sci. J. 2011;2011:17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-0929.2010.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M.I., Jo C., Tariq M.R. Meat flavor precursors and factors influencing flavor precursors: a systematic review. Meat Sci. 2015;201:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.Y., Tang T.K., Phuah E.T., Tan C.P., Wang Y., Li Y., Cheong L.Z., Lai O.M. Production, safety, health effects and applications of diacylglycerol functional oil in food systems: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;60:2509–2525. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1650001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Al-Dalali S., Zhou H., Wang Z.P., Xu B.C. Influence of mixture of spices on phospholipid molecules during water-boiled salted duck processing based on shotgun lipidomics. Food Res. Int. 2021;149:1106–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yang Y.Y., Tang C.H., Yue S.N., Zhao Q.Y., Li F.D., Zhang J.M. Changes in lipids and aroma compounds in intramuscular fat from Hu sheep. Food Chem. 2022;383 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yang Y.Y., Zhan T.F., Zhao Q.Y., Ao J.M.Z.X., He J., Zhou J.C., Tang C.H. Effect of slaughter weight on carcass characteristics, meat quality, and lipidomics profiling in longissimus thoracis of finishing pigs. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2021;140 [Google Scholar]

- Li M.M., Zhu M.X., Chai W.Q., Wang Y.H., Fan D.M., Lv M.Q., Jiang X.J., Liu Y.X., Wei Q.X., Wang C.F. Determination of lipid profiles of Dezhou donkey meat using an LC-MS-based lipidomics method. J. Food Sci. 2021;86:4511–4521. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lien E.L. The role of fatty acid composition and positional distribution in fat absorption in infants. J. Pediatr. 1994;125:62–68. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(06)80738-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Jiao J.G., Gao S., Ning L.J., Limbu S.M., Qiao F., Chen L.Q., Zhang M.L., Du Z.Y. Dietary oils modify lipid molecules and nutritional value of fillet in Nile tilapia: a deep lipidomics analysis. Food Chem. 2019;277:515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo N., Shu J.T., Yuan X.T., Jin Y.X., Cui H.X., Zhao G.P., Wen J. Differential regulation of intramuscular fat and abdominal fat deposition in chickens. BMC Genom. 2022;23:308. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08538-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv J.X., Ma J.J., Liu Y., Li P.P., Wang D.Y., Geng Z.M., Xu W.M. Lipidomics analysis of Sanhuang chicken during cold storage reveals possible molecular mechanism of lipid changes. Food Chem. 2023;417 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.135914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao H.G., Yin Z.Z., Wang M.T., Zhang W.M., Raza S.H.A., Althobaiti F., Qi L.L., Wang J.B. Expression of DGAT2 gene and its associations with intramuscular fat content and breast muscle fiber characteristics in domestic pigeons (Columba livia) Front. Vet. Sci. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.847363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensink R.P., Zock P.L., Kester A.D., Katan M.B. Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003;77:1146–1155. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S., Shang K., Jia W., Zhang C.H., Li X., Fan Y.Q., Wang H. Characterization and discrimination of Taihe black-boned silky fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus Brisson) muscles using LC/MS-based lipidomics. Food Res. Int. 2018;109:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottram D.S. Flavour formation in meat and meat products: a review. Food Chem. 1998;62:415–424. [Google Scholar]

- Roy B.C., Bruce H.L. Contribution of intramuscular connective tissue and its structural components on meat tenderness-revisited: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023;22:11671. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2023.2211671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahidi F., Hossain A. Role of lipids in food flavor generation. Molecules. 2022;27:5014. doi: 10.3390/molecules27155014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A., Simons K. Lipidomics: coming to grips with lipid diversity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nrm2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoła W.E., Wysoczański T., Wagner J., Czyż K., Bodkowski R., Lochyński S., Patkowska-Sokoła B. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their potential therapeutic role in cardiovascular system disorders: a review. Nutrients. 2018;10:1561. doi: 10.3390/nu10101561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi D.K., Hollywood K.A., Rattray N.J., Ward H., Trivedi D.K., Greenwood J., Ellis D.I., Goodacre R. Meat, the metabolites: an integrated metabolite profiling and lipidomics approach for the detection of the adulteration of beef with pork. Analyst. 2016;141:2155–2164. doi: 10.1039/c6an00108d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanni S., Riccardi L., Palermo G., Vivo M.D. Structure and dynamics of the acyl chains in the membrane trafficking and enzymatic processing of lipids. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019;52:3087–3096. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.N., Li X.D., Liu L., Zhang H.D., Zhang Y., Chang Y.H., Zhu amd Q.P. Comparative lipidomics analysis of human, bovine and caprine milk by UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS. Food Chem. 2020;310:1258–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y.Y., Liu H.H., Liu K., Cao H.Y., Mao H.G., Dong X.Y., Yin Z.Z. Analysis of the physical meat quality in partridge (Alectoris chukar) and its relationship with intramuscular fat. Poult. Sci. 2020;99:1225–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng K.Q., Huo W.R., Gu T.T., Bao Q., Cao Z.F., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Xu Q., Chen G. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis unveil the effect of marketable ages on meat quality in geese. Food Chem. 2021;361 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Xu X., Zhou G., Wang D., Li C. Changes of intramuscular phospholipids and free fatty acids during the processing of Nanjing dry-cured duck. Food Chem. 2008;110:279–284. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K., Han X. Lipidomics: techniques, applications, and outcomes related to biomedical sciences. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016;41:954–969. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yki J.H., Luukkonen P.K., Hodson L., Moore J.B. Dietary carbohydrates and fats in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021;18:770–786. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00472-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J., Yang H.M., Lai Y.Y., Wan X.L., Wang Z.Y. The body fat distribution and fatty acid composition of muscles and adipose tissues in geese. Poult. Sci. 2020;99:4634–4641. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.W., Liao Q.C., Sun Y., Pan T.L., Liu S.Q., Miao W.W., Li Y.X., Zhou L., Xu G.X. Lipidomic and transcriptomic analysis of the longissimus muscle of Luchuan and Duroc pigs. Front. Nutr. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.667622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.