Abstract

Eight Tn10 Tet repressor mutants with an induction-deficient phenotype and with primary mutations located at or close to the dimer interface were mutagenized and screened for inducibility in the presence of tetracycline. The second-site suppressors with wild-type-like operator binding activity that were obtained act, except for one, at a distance, suggesting that they contribute to conformational changes in the Tet repressor. Many of these long-range suppressors occur along the dimer interface, indicating that interactions between the monomers play an important role in Tet repressor induction.

Active export of tetracycline (TC) is the most frequently found resistance mechanism among gram-negative bacteria (19). The expression of resistance underlies stringent regulation depending on the presence or absence of TC. Seven closely related resistance determinants have been isolated (10). We examine Tet repressors (TetR) encoded by transposon Tn10 (class B) or plasmid RA1 (class D), which have 63% identical amino acids. Genetic and biochemical results reported for TetR(B) are consistent with the crystal structures of TetR(D)-TC complexes (11, 12). TetR is an all-α-helical protein. Its structure is shown in Fig. 1. Helices α1 to α3 form the reading head and contain a DNA binding helix-turn-helix motif (HTH) (2, 27). It is connected via helix α4 to the protein core, which is formed by helices α5 to α10 and which contains the TC binding pocket and the dimer interface. Detailed models of operator recognition (9) and TC binding (6, 11, 12, 14, 16) are available. Based on the crystal structure, a model for induction upon TC binding has been presented. It involves a seesaw-like movement of helix α4 on α6, thereby adjusting the distance and angle between the two reading heads (11, 12). An analysis of induction-deficient TetR mutants (TetRs) (4, 8, 16, 23, 28) led Müller et al. (16) to expand this model by proposing that the distance between the two reading heads is adjusted by the α4/α6 movement, while the angle between them is reduced by a shear movement of α8 and α10 from both subunits. The two helices from both subunits form a four-helix bundle, the main dimerization motif of TetR (11, 12).

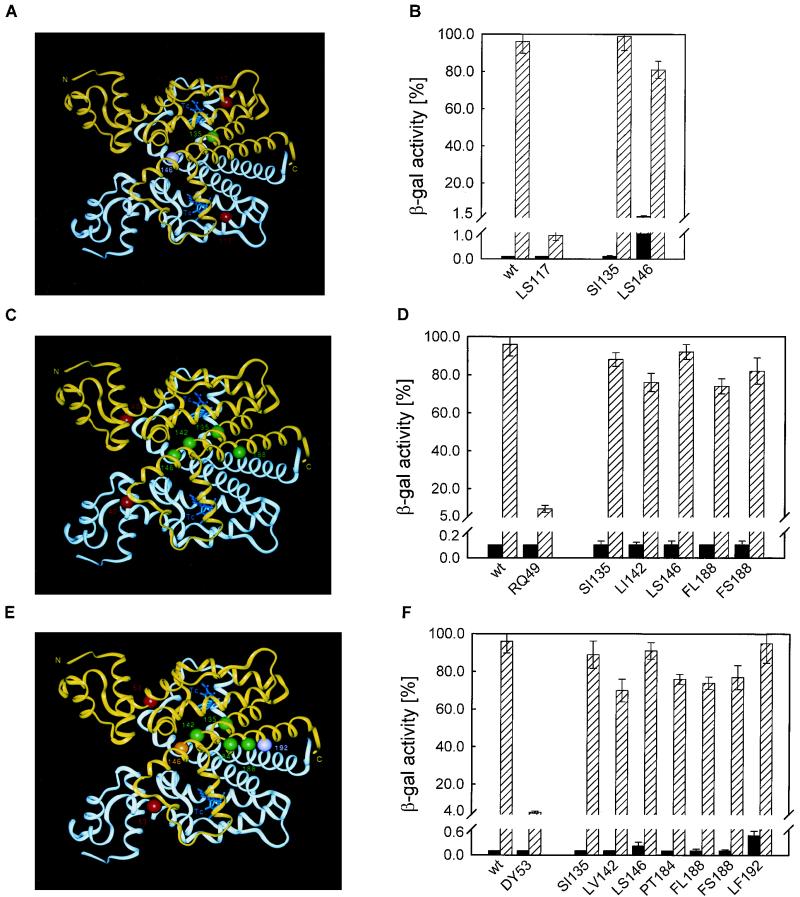

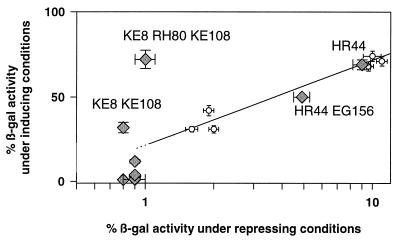

FIG. 1.

Position and phenotype of TetRs suppressor mutants. (A, C, E, G, and I) Crystal structure of the TetR(D)-TC complex. The two monomers are shown in white and yellow; TC is in blue. The position of the TetRs mutation is shown in red for both monomers, whereas the suppressors are only shown in the yellow monomer. Suppressors identified based on reduced operator binding affinity are pink; those identified based on mechanistic effects are green. Suppressors which could not be classified this way are orange. N and C indicate the N and C termini of the protein, respectively. The numbers give the positions of the respective amino acids and are marked with an additional prime in the white monomer. (B, D, F, H, and J) DNA binding (black bars) and inducibility by TC (hatched bars) are shown for TetR (wt) and the TetRs mutant with the indicated mutation in the left part of each panel and for the TetRs mutant with the indicated mutation in combination with the respective suppressor mutation in the right part of each panel. Standard deviations of repeated experiments are shown as vertical error bars.

Insight into movements within a protein can be gained from intragenic suppression, in which a functional deficiency caused by one mutation is compensated for by a second mutation. Examples of this approach include the identification of interacting regions within Escherichia coli RNA polymerase (26) or yeast mitochondrial cytochrome b (7). Poteete et al. (18) presented a very detailed structural analysis of second-site suppressors restoring the activity of a T4 lysozyme mutant. In these three cases, the intragenic suppressors are located near the sites of the respective primary mutations.

The large number of mutant residues in the dimer interface of induction-deficient TetR (8) suggested that this region is crucial for induction by TC (16). We reasoned that second-site suppressors of TetRs mutants might help identify contacts between the two monomers that are important for induction. Eight TetRs mutant residues were selected, and the positions of five of them in the TetR(D)-[Mg-TC]+ crystal structure are shown in Fig. 1A (LS117), 1C (RQ49), 1E (DN53), 1G (EG150), and 1I (Δ164–166). These residues are located at or close to the dimer interface, being not further than 4 Å away from amino acid residues in the second TetR monomer. They were selected from the three structural classes defined by Müller et al. (16) for mutants with a TetRs phenotype. Position L-117 directly contacts TC via a hydrophobic interaction (12) and, thus, LS117 belongs to the TC proximity class. RQ49, DY53, and EG150 belong to the domain connection class, since they are located at the interface between the reading head and the protein core. YC110, LF146, HR151, and Δ164–166 are less than 4 Å distant from residues in the other monomer of TetR and are grouped in the dimer interface class. It has been shown for all mutations selected that they exert their effects primarily by interfering with the conformational change which occurs upon TC binding and not by affecting TC binding itself (5, 16).

A stock of second-site mutants was prepared by fusing a pool of chemically mutagenized tetR fragments (8) to the respective tetR alleles encoding induction-deficient TetR mutants by using appropriate restriction sites (XbaI/BstXI for the N-terminal part (codons for residues 1 to 33), BstXI/MluI, for the central part (codons for residues 33 to 130), and MluI/SphI for the C-terminal fragment of TetR. The mutagenized fragments were chosen to encode residues in the other monomer of the TetR dimer which are located close to the respective primary mutations in the crystal structure. The tetR Δ164–166 allele was randomly mutagenized by error prone PCR (30).

The selection system consists of the λtet50 prophage (23) containing a single-copy tetPAO-lacZ transcriptional fusion. TetR is constitutively expressed in trans by plasmid pWH520 (3) or pWH1919 (Table 1) (8) and represses β-galactosidase (β-Gal) expression by binding to tetO in the absence of TC. Thus, growth on minimal medium with lactose as the sole carbon source is not possible without TC except for strains expressing TetR mutants deficient in operator binding. TetRs mutants are not able to grow on this medium even in the presence of TC. We selected for candidates from the second-site mutant stocks with the ability to grow on lactose minimal medium containing 0.4 or 0.5 μg of TC per ml or screened for dark-colored colonies on MacConkey lactose agar in the presence of 0.5 μg of TC per ml. Nonfunctional repressor mutants were identified by growth on selective media without TC and eliminated from further analysis.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains, plasmids, and phages

| Strain, plasmid(s), or phage | Genotype or description | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| CB454 | Selector strain; ΔlacZ galK rpsL recA56 | 20 |

| DH5α | Cloning strain; hsdR17(rK− mK+) recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi relA1 supE44 φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA argF)U169 | Gibco-BRL |

| JM101 | Mutagenesis strain; Δ(lac-proAB) thi supE F′ [traD36 proAB lacIqZΔM15] | 29 |

| NK5031(λtet50) | Source of tetA-lacZ transcriptional fusion; ΔlacM5265 supF nalR thi; λtet50 is integrated in single copy into the NK5031 genome | 23 |

| RZ1032 | Mutagenesis strain; HfrKL16 PO/45 lysA(61-62) dut-1 ung-1 thi-1 relA1 supE44 Zbd-279::Tn10 | 13 |

| SCS1 | Cloning strain; hsdR17(rK− mK+) recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 supE44 | Stratagene |

| WH207 | Tester strain; ΔlacX74 galK2 rpsL recA | 28 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pWH520, pWH520Δ164–166 | Derivatives of pWH1201; tetR and tetR Δ164–166 expression plasmids | 3, 4 |

| pWH1012 | Apr; pBR322 derivative; tetA-lacZ transcriptional fusion | 22 |

| pWH1201 | Cloning vector; Kmr; pACYC177 derivative | 1 |

| pWH1919 | Same as pWH520; tetR with additional restriction sites for BstXI and MluI | 8 |

| pWH1919-X | X:RQ49, DY53; YC110; LS117; LF146; EG150; HR151; tetR mutants chosen for suppression | 8 |

| Phages | ||

| λtet50 | Wild-type cI; tetA-lacZ transcriptional fusion | 23 |

| mWH819 | Mutagenesis vector | 27 |

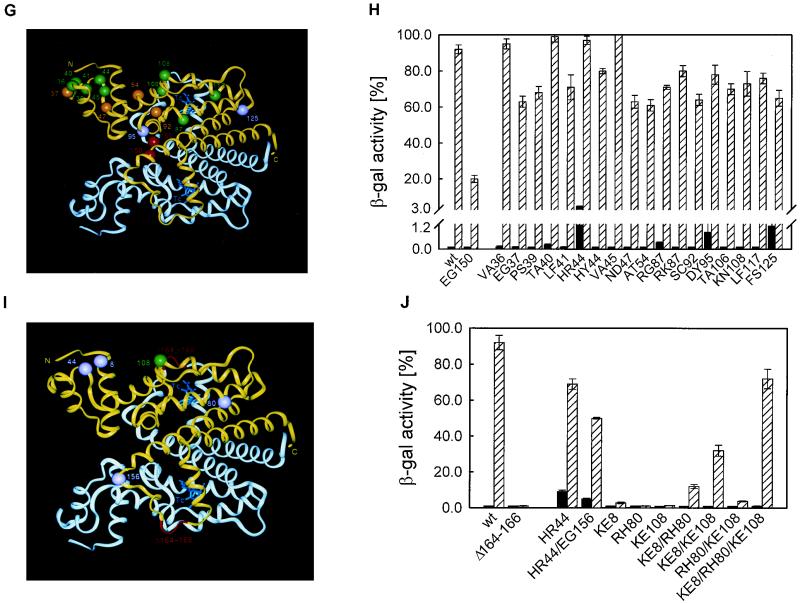

Apart from allosteric suppression, TetRs suppression may also result from reduced intracellular protein amounts, reduced operator affinity, or increased TC binding. The intracellular amounts of several TetRs suppressors were checked by Western blotting (data not shown). No mutants with reduced intracellular TetR levels were found. Reduced operator binding affinity was tested by introducing mutations conferring reduced DNA binding activity into tetR Δ164–166 (5). The β-Gal expression levels in the presence of TC of strains carrying the resulting double mutants were plotted in Fig. 2 versus their β-Gal expression levels in the absence of TC. The semilogarithmic graph is nearly linear between the lower resolution limit of expression without TC and the upper limit corresponding to wild-type (wt) inducibility. This demonstrates that decreased tetO binding leads to increased apparent inducibility. Suppressor mutants whose expression levels lie on the reference line most likely act by reducing tetO binding. Induction of β-Gal expression to levels above the line would indicate suppression that is not solely due to decreased tetO binding. Induction to a level below the line would suggest a stronger TetRs phenotype. Suppressors with reduced or ambiguous tetO binding will not be discussed in detail. Increased TC binding needs to be determined in vitro and is not experimentally addressed in this study. Judging by the crystal structures, we do not consider increased TC binding of the suppressor mutant residues likely, since they do not contact TC.

FIG. 2.

Semilogarithmic plot of β-Gal activities in the presence of inducer versus β-Gal activities in the absence of TC. β-Gal expression was determined as described by Miller (15) with cells grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. For measuring inducibility, TC was added at a concentration of 0.2 μg/ml. Three to four independent cultures were assayed for each strain, and measurements were carried out at least twice. The open circles correspond to the TetRs mutant TetR Δ164–166 (0.8% ± 0.0% β-Gal activity under repressed conditions and 0.9% ± 0.0% activity under induced conditions) and the TetR Δ164–166 double mutants with substitutions within the HTH. The mutations and the corresponding activities under repressed and induced conditions, respectively, are as follows: TG40, 1.6% ± 0.1% and 31% ± 1.6%; TQ27, 1.9% ± 0.1% and 42% ± 3.0%; VS36, 2.0% ± 0.1% and 31% ± 2.2%; LT41, 9.6% ± 0.5% and 68% ± 2.7%; QG38, 10% ± 0.9% and 74% ± 3.0%; VW36, 15% ± 0.7% and 85% ± 2.5%; WG43, 17% ± 2.1% and 87% ± 4.4%; KT48, 20% ± 1.1% and 82% ± 2.9%. The filled diamonds represent the suppressors isolated or constructed for the mutant TetR Δ164–166. The reference line was fitted by linear regression. Mutants above or on this line are labelled.

TC proximity class.

TetR LS117 was suppressed by mutations SI135 and LS146 (Fig. 1A). (The nomenclature for suppressors is as follows. The primary mutation is given first and is followed by the suppressor mutation(s), with amino acids abbreviated by standard one-letter coding. Individual mutation designations are as in the following example: LS117 denotes a leucine-to-serine exchange at position 117 in the TetR primary structure.) In Fig. 1B, TetR LS117;LS146 has reduced repression efficiency compared to the wt, while TetR LS117;SI135 shows almost wt repression, indicating allosteric suppression. Both primary and suppressing mutations approach helix α9 from the other monomer. This helix is important for induction. Its proposed role is to act as a bolt locking the four-helix bundle in its conformation in the induced structure (16).

Domain connection class.

Eight mutations were isolated as intragenic suppressors for TetR RQ49 (Fig. 1C and D). Two of them (FI186 and LF191) confer significantly reduced tetO affinity. The other six suppressor mutations cause no (ED147 and FL188) or only a less-than-twofold (SI135, LI142, LS146, and FS188) reduction of operator affinity. Five mutants exhibit a high level of inducibility (≥70% of wt β-Gal activity), indicating allosteric suppression of the TetRs phenotype, while TetR RQ49;ED147 is not as inducible.

All seven suppressors isolated for TetR DY53 (Fig. 1E and F) are inducible to at least 70% of the wt efficiency. FL188, LS146, and LF192 give rise to moderately decreased operator affinities; the other suppressor mutations confer wt-like (SI135, LV142, and PT184) or only slightly reduced (FS188) tetO affinities.

Except for SI135, the allosteric suppressors isolated for TetR RQ49 and TetR DY53 are located in helices α8 and α10 at the helix contact sites and are, thus, part of the dimerization interface. In most of the cases, the suppressing amino acids are smaller than the original amino acids, which might introduce greater flexibility into the four-helix bundle and explain the suppression observed. This finding underscores the importance of the dimerization interface for the induction mechanism, in support of the model of Müller et al. (16), in which conformational changes in the four-helix bundle are crucial for TetR induction.

Eighteen mutations suppressing the TetRs phenotype of TetR EG150 were isolated (Fig. 1G and H). Thirteen suppressor mutants show repression efficiencies like that of the wt or TetR EG150, with ≤0.1% β-Gal activity. Four of these TetR EG150 derivatives combine near-wt inducibility (≥80% β-Gal activity) with wt (mutations HY44 and RK87) or only slightly reduced (mutations VA36 and VA45) operator affinities. The remaining nine suppressors have similar affinities for tetO but slightly lesser inducibilities of about 60% (mutations EG37, ND47, AT54, and SC92) or 70% (mutations PS39, LF41, TA106, KN108, and LF117) of wt β-Gal activity. Suppressor mutations TA40, HR44, RG87, DY95, and FS125 confer decreased operator affinity. The allosteric suppressors located in the reading head (residues 36 to 47) are at positions which do not contact tetO but rather are involved in structure formation of the HTH (27). Mutations at these residues might alter the structure of the HTH, thus contributing to suppression. Mutant residues located at the dimer interface (mutations RK87, TA106, KN108, and LF117) are in the vicinity of the variable loop separating helices α8 and α9 and helix α9 of the other monomer. Both elements are involved in the conformational change that occurs upon induction by TC (5, 16).

Domain interface class.

Two second-site suppressor mutations were found for TetR YC110 (ED147 and FI186), one for TetR LF146 (TA40), and five for TetR HR151 (VA36, TA40, RW49, WR75, and RT87). None of them conferred a high level of inducibility without significant increase of β-Gal expression in the absence of TC, indicating that these suppressor mutations act by reducing the tetO affinity (data not shown).

Thirty-two candidate suppressors were isolated for TetR Δ164–166. The DNA binding activity of twenty-one suppressors was found to be reduced to 20 to 30% of β-Gal expression observed in the reference measurements without TetR. They were not analyzed further. The other suppressors were sequenced, and the mutations determined are shown in Fig. 1I. Six suppressors contain the HR44 exchange, known to reduce DNA binding activity (2); one of these has an additional EG156 substitution. They exhibit reduced tetO binding; those with the HR44 exchange show 8% of β-Gal expression, and that with the additional EG156 substitution shows 5% of wt β-Gal expression (Fig. 1J). The other five candidates bind the operator at the wt level. They all contain the three-amino-acid exchanges KE8;RH80;KE108. Since it is not clear whether the three mutations are necessary for suppression, we constructed all possible combinations of single and double exchanges (13, 25). Their DNA binding activities and inducibilities are shown in Fig. 1J. All mutant combinations of TetR Δ164–166 repress β-Gal expression as efficiently as the wt. Of the single-amino-acid substitutions, only TetR Δ164–166;KE8 is marginally inducible. The double exchanges are all partially inducible; the highest level of inducibility is observed for the original suppressor, TetR Δ164–166;KE8;RH80;KE108. The inducibilities of the mutants were plotted in Fig. 2 against their repression. Only TetR Δ164–166;KE8;KE108 and TetR Δ164–166;KE8;RH80;KE108 lie above the straight line and are, thus, considered to be allosteric suppressors. The RH80 exchange might contribute to inducibility by reducing the affinity for tetO. K-8 lies in the first turn of helix α1. Its side chain points towards the N terminus of TetR and the C terminus of HTH-positioning helix α2 (12). The N-terminal residues are important for the structure and orientation of the HTH (3, 12). Substitution of the positively charged Lys with a negatively charged Glu could introduce unfavorable steric and electrostatic interactions, for example, at the negatively charged dipole at the C terminus of α2 (17, 21). This might alter the structure of the DNA binding domain, contributing to suppression. K-108 is located in the protein core at the end of the loop separating helices α6 and α7. Its side chain points towards residue K-6 in the DNA binding domain and comes close to residues in the C-terminal part of α4. Substitution of the wt Lys with Glu could lead to the formation of a novel hydrogen bond with residue K-6 (24). This H bond in the domain connection might stabilize the induced conformation, thereby suppressing the TetRs phenotype.

Conclusions.

Except for one (TetR EG150;DY95), all allosteric suppressor mutations affect residues which are not in direct contact with the primary mutation in the crystal structure of the TetR(D)-[Mg-TC]+ complex (11, 12). This hints that global structural changes involving both mutations occur between the operator binding and induced forms of TetR. Interference of a TetRs mutant with these conformational changes could then be suppressed by mutations at distant sites. The numerous suppressor residues at the dimer interface lend strong support to the proposal by Müller et al. (16) that a conformational change in the four-helix bundle contributes to the induction of TetR by TC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dirk Schnappinger and Andreas Ratajczak for help in setting up the selection system.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Fonds der chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschmied L, Baumeister R, Pfleiderer K, Hillen W. A threonine to alanine exchange at position 40 of Tet repressor alters the recognition of the sixth base pair of tet operator from GC to AT. EMBO J. 1988;7:4011–4017. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumeister R, Helbl V, Hillen W. Contacts between Tet repressor and tet operator revealed by new recognition specificities of single amino acid replacement mutants. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:1257–1270. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91065-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berens C, Altschmied L, Hillen W. The role of the N terminus in Tet repressor for tet operator binding determined by a mutational analysis. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1945–1952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berens C, Pfleiderer K, Helbl V, Hillen W. Deletion mutagenesis of Tn10 Tet repressor—localisation of regions important for dimerization and inducibility in vivo. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:437–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berens C, Schnappinger D, Hillen W. The role of the variable region in Tet repressor for inducibility by tetracycline. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6936–6942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.6936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Degenkolb J, Takahashi M, Ellestad G A, Hillen W. Structural requirements of tetracycline-Tet repressor interaction: determination of equilibrium binding constants for tetracycline analogs with the Tet repressor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1591–1595. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.8.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.di Rago J-P, Hermann-Le Denmat S, Pâques F, Risler J-I, Netter P, Slonimski P P. Genetic analysis of the folded structure of yeast mitochondrial cytochrome b by selection of intragenic second-site revertants. J Mol Biol. 1995;248:804–811. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hecht B, Müller G, Hillen W. Noninducible Tet repressor mutations map from the operator binding motif to the C terminus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1206–1210. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1206-1210.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helbl V, Baumeister R, Hillen W. A molecular model for Tet repressor-tet operator recognition based upon a genetic analysis: implications for sequence specific interaction of α-helices with DNA. Curr Top Mol Genet. 1993;1:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillen W, Berens C. Mechanisms underlying expression of Tn10 encoded tetracycline resistance. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:345–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinrichs W, Kisker C, Düvel M, Müller A, Tovar K, Hillen W, Saenger W. Antibiotic resistance: structure of the Tet repressor-tetracycline complex and mechanism of induction. Science. 1994;264:418–420. doi: 10.1126/science.8153629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kisker C, Hinrichs W, Tovar K, Hillen W, Saenger W. The complex formed between Tet repressor and tetracycline-Mg2+ reveals mechanism of antibiotic resistance. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:260–280. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunkel T A, Roberts J D, Zakour R A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. In: Wu R, Grossman L, editors. Methods in enzymology. 154, Recombinant DNA (part E) San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 367–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lederer T, Kintrup M, Takahashi M, Sum P-E, Ellestad G A, Hillen W. Tetracycline analogs affecting binding to Tn10-encoded Tet repressor trigger the same mechanism of induction. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7439–7446. doi: 10.1021/bi952683e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Müller G, Hecht B, Helbl V, Hinrichs W, Saenger W, Hillen W. Characterization of non-inducible Tet repressor mutants suggests conformational changes necessary for induction. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:693–703. doi: 10.1038/nsb0895-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicholson H, Becktel W J, Matthews B W. Enhanced protein thermostability from designed mutations that interact with α-helix dipoles. Nature. 1988;336:651–655. doi: 10.1038/336651a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poteete A R, Dao-Pin S, Nicholson H, Matthews B W. Second-site revertants of an inactive T4 lysozyme mutant restore activity by restructuring the active site cleft. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1425–1432. doi: 10.1021/bi00219a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts M C. Epidemiology of tetracycline-resistance determinants. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:353–357. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90610-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider K, Beck C F. Promoter-probe vectors for the analysis of divergently arranged promoters. Gene. 1986;42:37–48. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shoemaker K R, Kim P S, York E J, Stewart J M, Baldwin R L. Tests of the helix dipole model for stabilization of α-helices. Nature. 1987;326:563–567. doi: 10.1038/326563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sizemore C, Wissmann A, Gülland U, Hillen W. Quantitative analysis of Tn10 Tet repressor binding to a complete set of tet operator mutants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:2875–2880. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.10.2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith L D, Bertrand K P. Mutations in the Tn10 tet repressor that interfere with induction; location of the tetracycline-binding domain. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:949–959. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stickle D F, Presta L G, Dill K A, Rose G D. Hydrogen bonding in globular proteins. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:1143–1159. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91058-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su T-Z, El-Gewely M R. A multisite-directed mutagenesis using T7 DNA polymerase: application for reconstructing a mammalian gene. Gene. 1988;69:81–89. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tavormina P L, Reznikoff W S, Gross C A. Identifying interacting regions in the β subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:213–223. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wissmann A, Baumeister R, Müller G, Hecht B, Helbl V, Pfleiderer K, Hillen W. Amino acids determining operator binding specificity in the helix-turn-helix motif in Tn10 Tet repressor. EMBO J. 1991;10:4145–4152. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wissmann A, Wray L V, Jr, Somaggio U, Baumeister R, Geissendörfer M, Hillen W. Selection for Tn10 Tet repressor binding to tet operator in Escherichia coli: isolation of temperature-sensitive mutants and combinatorial mutagenesis in the DNA binding motif. Genetics. 1991;128:225–232. doi: 10.1093/genetics/128.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Y, Zhang X, Ebright R H. Random mutagenesis of gene-sized DNA molecules by use of PCR with Taq DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6052. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.21.6052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]