Abstract

Introduction

To change blood pressure treatment, clinicians can modify medication count or dose. However, existing studies measured count modification, which may miss clinically important dose change in the absence of count change. This research demonstrates how dose modification captures more information about management than medication count alone.

Methods

We included patients ≥65 years old with established primary care at the Veterans Health Administration (7/2011–6/2013). We captured medication count and standardized dose change over 90–120 days using a validated pharmacy fill algorithm. We determined frequency of dose change without count change (and vice versa), no change in either, change in same direction (“concordant”) and change in opposite direction (“discordant”). We compared change according to systolic blood pressure (SBP) and compared concordance using a minimum threshold definition of dose change of ≥50% (instead of any change) of baseline dose modification.

Results

Among 440,801 patients, 64.2% had dose change, 22.0% count change, 35.6% no change in either, 42.4% dose change without count modification, and 0.2% count change without dose modification. Discordance occured in 2.1% of observations. Using the minimum threshold definition of change, 68.7% had no change in either dose or count. Treatment was more frequently changed at SBP >140 mmHg.

Conclusion

Measuring change in antihypertensive treatment using medication count frequently missed an isolated dose change in treatment modification, and less often misclassified regimen modifications where there was no modification. In future research, measuring dose modification using our new algorithm would more precisely capture change in hypertension treatment intensity than current methods.

PRECIS

Medication dose captures modification of hypertension treatment intensity more precisely than medication count, and should be preferred in studies aimed to improve hypertension management.

1. INTRODUCTION

To modify blood pressure (BP) treatment intensity, clinicians can modify the number and/or dose of antihypertensive medications. While trials to reduce cardiovascular events frequently achieved better BP control through the addition of new medications, for older adults, increasing doses before starting new medications can reduce polypharmacy and the risk of potential new side effects.1 Optimizing treatment intensification versus deintensification is particularly relevant to older multimorbid adults, where the absolute magnitude of this effect is greatest given increased baseline risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes, in addition to increased vulnerability to side effects and drug-disease interactions.1 Moreover, large administrative datasets provide a key opportunity to compare change in antihypertensive treatment intensity in this population most frequently excluded from randomized trials.2–6 Studies to date have typically measured treatment modification in terms of medication count,4,5,7–11 a method that could falsely report clinical inertia in patients who actually increased only doses of medications.

To overcome this challenge, we previously developed and validated an algorithm that uses Veterans Health Administration and Medicare Part D pharmacy fill data to measure hypertension treatment intensity by capturing total daily dose equivalents (standardized doses used by hypertension trials), using prefills and refills within 186 days to determine the most likely antihypertensive regimen (medication name and dose) on any day of outpatient care.12,13 Unlike previous measures that focused on toxicity, this measure is based on evidence-based doses of clinical benefit demonstrated in trials of hypertension treatment, and provides standardized doses allowing to compare treatment intensity across all antihypertensive medications.

In this paper, we used this approach to compare the measurement of treatment change by the change in medication dose versus change in medication count.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population and data

We used administrative and clinical information from the Veterans Affairs (VA) Clinical Data Warehouse, which includes all ambulatory care encounters and VHA pharmacy records, between 7/1/2009 and 6/30/2013. Patients’ records are linked with Medicare Part D medication claims (Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Health Services Research and Development Service, VA Information Resource Center (#02–237 and 98–004)). This research was conducted under Human Subjects review (VA IRB 2015–286).

We included all Veterans aged ≥65 years with hypertension (International Classification of Diseases 9 code 401.x), established VHA primary care (≥2 visits between 7/1/2009 and 6/30/2011), and ≥2 primary care visits during the study period (7/1/2011–6/30/2013). Using providers’ codes (Supplemental Text 1), we identified all outpatient visits from primary care and hypertension-managing specialties (cardiology, endocrinology, nephrology, neurology) over the two-year study period. The dates of these visits were used to calculate treatment intensity.

To assess short-term (three-month) treatment modification, we identified all pairs of visits during the study period (7/1/2011–6/30/2013) with an interval between 90 and 120 days between the visits. We refer to the earlier visit (baseline visit) as “visit 1”, and the later as “visit 2” (Supplemental Figure 1). The 90-day minimum interval was chosen because it is a typical medication fill duration. We added the 120-day upper limit to allow for a small degree of delay in refill, while ensuring that the visit interval was still short-term. To assess longer-term (one-year) treatment modification, we used a 365–395-day interval to pair the visits during the study period. For each time interval-based analysis, we included only the first available pair of visits per patient, so that no patient could appear in any analysis more than once.

2.2. Main study variables

To identify antihypertensive treatment from pharmacy fills, we employed a calibrated algorithm that we previously developed and validated in a sample of this cohort.12,13 Briefly, this algorithm uses VA and Medicare Part D pharmacy prefills (within 186 days before an outpatient visit), and refills (within 186 days after) to determine the most likely antihypertensive medication on any day, including name, medication, and dose. To allow comparison across antihypertensive medications, we assigned Hypertension Daily Dose (HDD) units, where one HDD corresponds to a standardized moderate dose, defined as half of the maximum beneficial dose demonstrated in trials for a given antihypertensive medication. These doses are published in the Joint National Committee (JNC) 7 and 8 guidelines,14,15 and American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) Hypertension guideline.16 For example, hydrochlorothiazide’s maximum beneficial trial-proven dose is 50 mg, thus 25 mg represents one HDD. To capture dose reduction that might occur by splitting pills during a supply, we adjusted doses downward if a medication was refilled >30 days after planned refill (e.g., we halved dose for a 90-day supply that was first refilled after 180 days). We summed all antihypertensive medication doses to assign a total dose to a patient for each visit. All data were extracted electronically. The algorithm measures were validated by chart review.13

2.3. Main measures

We calculated the change in both total standardized dose and in medication count between the two visits (i.e., total dose at visit 2 minus total dose at visit 1, and medication count at visit 2 minus medication count at visit 1). We specified three levels of treatment modification for both dose and count and: deintensification (total dose or medication count decrease between visits), intensification (total dose or medication count increase between visits), stable treatment (no change by either definition between visits). To assess how much the relationship between dose and count changed according to the amount of dose modification, we conducted sensitivity analyses where we defined dose change (i.e., deintensification or intensification) as modification of at least 25% or 50% of baseline dose.

2.4. Statistical analyses

To assess agreement between dose and medication count change, we compared the proportions of each possible combination of dose and count modifications, and specifically measured no change in either dose or count, a concordant change (dose and count change in the same direction), an isolated change (dose change without medication count modification, or the opposite), and a discordant change (change in the opposite direction). We performed those analyses for both time intervals separately. Furthermore, in a sensitivity analysis, we assessed the relationships between dose and count change by baseline systolic BP (SBP), grouped as: <120 mmHg, 120–140 mmHg and >140 mmHg. Finally, in another sensitivity analysis, we assessed those relationships in which a dose change was defined based on as at least 25% or 50% change in the baseline dose.

We used χ2 tests to assess statistical significance. We conducted all analyses with Stata 16 software (Stata-Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA), and SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute).

3. RESULTS

Among 1,331,111 patients with 7,026,781 visits, we identified 440,801 patients with a paired visit interval of 90–120 days, and 499,207 patients with a visit interval of 365–395 days. Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients for the 90–120-day visit intervals (N=440,801).

| Characteristics | Mean (SD), or N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Demographics | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 75.1 (7.5) |

| Male, N (%) | 431,700 (97.9) |

|

| |

| Blood pressure | |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean (SD) | 130.6 (15.8) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean (SD) | 70.6 (10.2) |

| Systolic blood pressure <120 mmHg, N (%) | 96,856 (22.0%) |

| Systolic blood pressure 120–140 mmHg, N (%) | 242,024 (54.9%) |

| Systolic blood pressure >140 mmHg, N (%) | 101,941 (23.1%) |

|

| |

| Chronic conditions | |

| - number, mean (SD) | 5.1 (3.8) |

| - multimorbidity (≥2 chronic conditions), N (%) | 375,250 (85.1%) |

| - cardio-, cerebro-, or peripheral vascular disease, N (%) | 188,654 (42.8%) |

| - heart failure/valve disorder, N (%) | |

| - diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 98,539 (22.4%) |

| - arrhythmia, N (%) | 183,143 (41.6%) |

| 65,405 (14.8%) | |

|

| |

| Baseline blood pressure medication regimen | |

| - medication count, mean (SD) * | 2.2 (1.1) |

| ≥2 medications, N (%) | 313,632 (71.2%) |

| ≥4 medications, N (%) | 53,003 (12.0%) |

| - HDD, unit, mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.8) |

| ≥2 HDDs, N (%) | 220,250 (50.0%) |

| ≥4 HDDs, N (%) | 78,343 (17.8%) |

Abbreviations: HDD, Hypertension Daily Dose; N, number; SD standard deviation.

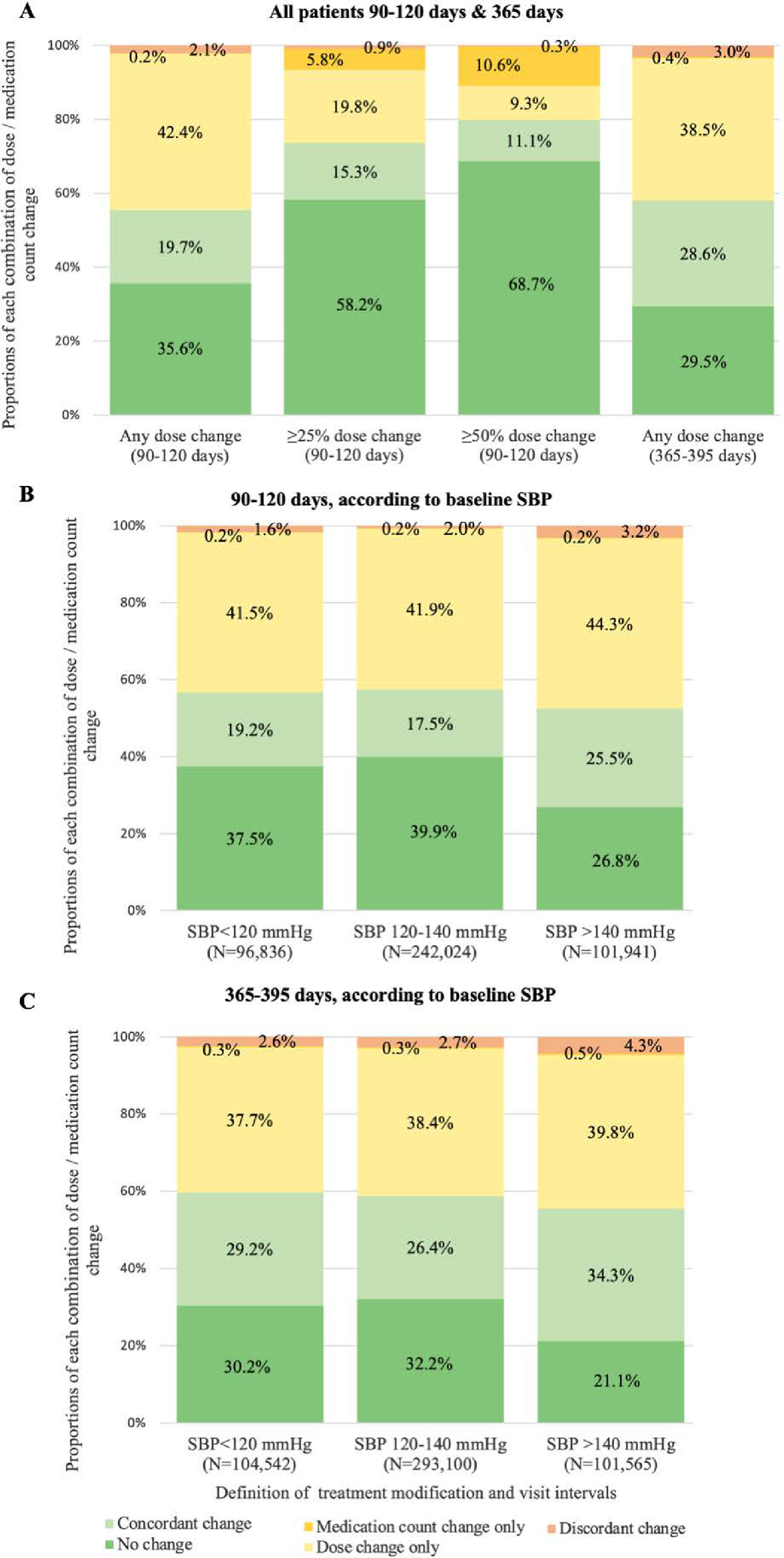

3.1. Change over three months (Figure 1A, column 1)

Figure 1.

Proportions of changes for each possible combination of dose and medication count modification, according to intensity of dose change to define treatment modification, visit intervals (N=440,801 patients for 90–120 days, and N=499,207 patients for 365–395 days), and baseline SBP.

The figure displays the proportions of change for each possible combination of dose change (or no change) and medication count change (or no change). No change was defined as no change in either medication dose or count. A concordant change was defined as a dose and medication count change in the same direction. A discordant change was defined as a dose increase with medication count reduction, or a dose decrease with medication count increase. “Dose change only” refers to a dose change without any medication count modification. “Medication count change only” refers to a medication count change without dose modification (or with dose modification <25% or <50% of baseline dose for the second and third columns of the first panel).

Abbreviations: N, number; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Among our 440,801 patients, 64.2% had a dose change, whereas 22.0% had a count change in the 90–120-day visit interval (p<0.001). No change in either dose or medication count was observed in 35.6% of patients, a concordant change in 19.7%, and a discordant change in 2.1%. Dose modification without medication count change was observed in 42.4% of patients, while 0.2% had count change with no change in dose.

3.2. Change according to amount of dose modification (Figure 1A)

When we defined a dose modification only if there was at least 25% change of baseline dose5.8% of patients had an isolated medication count modification, as opposed to 0.2% using any dose change to define dose modification, 19.8% had a dose change without any modification of medication count change (instead of 42.4% for any dose change definition), and 58.2% had no change in either dose or medication count (instead of 35.6% for any dose change definition).

3.3. Concordance of change over one year (Figure 1A, column 4)

Similar to what we observed over three months, dose change was more frequent than medication count modification over one year (70.1% versus 32.0% of the 499,207 patients with a 365–395-day visit interval; p<0.001), while 29.5% of patients had no change in either dose or count, 28.6% had concordant change, and 3.0% had discordant change.

3.4. Concordance according to baseline SBP (Figure 1B&C)

The relationship between dose and medication count modification was mostly similar for baseline SBP <120mmHg vs. 120–140 mmHg. However, compared to patients with SBP ≤140 mmHg, those with SBP >140 mmHg had a concordant or discordant change with greater frequency, and no change in either dose or medication count with greater frequency. . When treatment was modified, it was most frequently intensified in patients with higher SBP, and deintensified in those with lower SBP. The relationships were similar over the two time intervals.

4. DISCUSSION

In this large study using a validated pharmacy fill algorithm in older Veterans with hypertension, measuring changes in standardized total dose identified more modifications in treatment intensity than counting medications alone. A dose change without a concurrent medication count modification was frequent: 42% of patients had a change in treatment intensity that would have been missed if only medication counts been considered. On the other hand, a change in medication count without a change in dose was rare. The daily dose and medication count methods agreed more when we increased the criteria stringency required to define a treatment change from any change, to at least 25% or 50% of the baseline dose. Discordant changes were uncommon. This under-estimation of treatment modification rates when using medication count alons vs dose change was more pronounced for patients with SBP >140mmHg, where treatment changes between visits were more common compared to patients with SBP ≤140mmHg. Our results suggest that future research to improve hypertension management care that measures dose changes would more precisely capture clinical action and the continuum of treatment intensity than medication count alone. Our algorithm offers a validated way to apply such measures into healthcare practice and health outcome research.

A main finding of this study is the high frequency of dose modification without medication count change. While medication count remains the most common method to assess a change in hypertension treatment intensity,4,5,7–11 our results suggest that this may miss some trajectories of treatment intensity modification. Capturing dose change may be particularly relevant in older adults with polypharmacy and higher vulnerability to adverse drug events,1 and should thus be considered in further studies. We observed a slightly higher proportion of treatment intensity modification when looking at paired visits over one year than three months. This is likely due to a greater opportunity for clinical encounters, more time to make a change, and a larger window in which to capture the change in dose on the subsequent refills. In addition, older multimorbid patients have more health events per unit of time than younger healthier ones. A cardiovascular event might justify intensification, while a global health deterioration may lead to deintensification and more of these events will be seen over longer time intervals. The lower rates of treatment modification in shorter intervals may also be due to patient, physician, system-level, and environmental barriers to treatment modification that may lead to therapeutic inertia,17,18 potentially exacerbated by a lack of recognition of the benefits of controlling SBP even among very old patients. In the presence of barriers, more time may also be required to allow for reflection and shared decision-making. Finally, because blood pressure fluctuates over time, physicians may wait to document blood pressure measurements over several visits before modifying treatment intensity. However, the higher proportion of treatment modification (mostly intensification) for baseline SBP >140 mmHg suggests that physicians are more reactive when SBP is high.

Modifications in medication count without dose change, are not necessarily paradoxical and may result from the management of non-hypertension conditions. For example, a physician might start a beta blocker for rate control in atrial fibrillation, while reducing the dose of another antihypertensive medication to keep treatment intensity the same. Discordant changes might occur when an antihypertensive medication at a low dose is discontinued due to side effects or to reduce treatment complexity and polypharmacy, but the dose of another antihypertensive medication is increased with a goal of net intensification to treat a BP still above goal. Non-hypertension conditions may be more frequent in patients with higher SBP, potentially explaining a higher proportion of discordant observations for baseline SBP >140mm Hg. Discordant changes represented only 2.1% of all observations, while a medication count modification without dose change occurred in 0.2%. Therefore, our findings suggest that whereas antihypertensive medication count will frequently miss dose modifications (false negatives), a medication count change rarely will classify an episode with no change in dose as having treatment modification (false positives).

Our pharmacy fill algorithm allowing to measure change in standardized dose of antihypertensive medications has several potential implications. First, in light of recent more aggressive recommendations for hypertension management,16,19 it will allow for more precise tracking of antihypertensive treatment intensity. Second, it could serve in future studies assessing the outcomes related to hypertension treatment intensity modification, which are required to improve hypertension care and management of older multimorbid patients, who are often excluded from clinical trials used for guideline development.2–6

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, pharmacy fills are not perfect to capture medication discontinuation when a patient stops taking their medication before the pill supply ends. Our algorithm partly accounts for this if there is no further refill but that the visit date is within 80–90% of the final pill supply duration, a criterion that was probabilistically determined in prior research.20,21 Furthermore, some data suggest that pharmacy fills are a reliable source of information to capture medication consumption.22,23 Second, although the data date from 2011–2013, the medications we studied remain in widespread use today. Furthermore, while hypertension guidelines have changed following the SPRINT trial,4 we do not expect the relationship between dose and count to have changed. Third, we included only patients aged ≥65 years old, so the results may not generalized to younger patients. Nonetheless, older adults account for the large majority of hypertension and cardiovascular deaths such that older populations are of heightened clinical relevance. This study’s strengths are its large national sample across US regions of the largest US health system, with excellent medication capture linking both VA and Medicare prescription data, and the use of a standardized method to assess antihypertensive medication doses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, applying standardized doses based on beneficial doses demonstrated in trials, and using a near-universal medication data source for the largest US healthcare system, antihypertensive medication dose identified changes in hypertension treatment intensity more precisely than medication count. Using standardized medication doses may therefore better represent practice change. This method is an additional tool that can be used by health systems and observational studies such as comparative effectiveness research in intensification and deintensification approaches.

Supplementary Material

TAKE-AWAY POINTS.

Antihypertensive medication count frequently missed modification in treatment intensity when there was an isolated dose change, but rarely misclassified regimen modifications when there was no change in treatment intensity.

We provide a measure of hypertension treatment intensity over time that uses standardized antihypertensive medication doses, which is more precise than medication count alone and offers a better way to assess hypertension treatment intensity over time in further studies aiming to improve hypertension management.

Measuring antihypertensive dose modification instead of medication count alone may be particularly relevant in older adults, because of their vulnerability to dose-related averse medication events.

Funding:

This research was funded by R01 from the National Institute on Aging (Min AG047178) and the Veterans Health Administration (Min IIR 14–083). Dr. Aubert was supported by an Early Postdoc.Mobility grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant P2LAP3_184042). Dr. Terman was supported by the University of Michigan Department of Neurology Training Grant 5T32NS007222–38. The funders had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Informed consent: Was not required.

Code availability: Codes are available on reasonable request upon request by the corresponding author.

Availability of data and material:

Individual patient data are not available for sharing by our data use agreement with the Department of Veterans Affairs.

6. REFERENCES BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Onder G, van der Cammen TJ, Petrovic M, Somers A, Rajkumar C. Strategies to reduce the risk of iatrogenic illness in complex older adults. Age Ageing. 2013;42(3):284–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gueyffier F, Bulpitt C, Boissel JP, et al. Antihypertensive drugs in very old people: a subgroup meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. INDANA Group. Lancet. 1999;353(9155):793–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staessen JA, Gasowski J, Wang JG, et al. Risks of untreated and treated isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet. 2000;355(9207):865–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sprint Research Group Wright JT Jr., Williamson JD, et al. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373(22):2103–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1887–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A, et al. Benefits and Harms of Intensive Blood Pressure Treatment in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(6):419–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boockvar KS, Song W, Lee S, Intrator O. Hypertension Treatment in US Long-Term Nursing Home Residents With and Without Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(10):2058–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luymes CH, Poortvliet RKE, van Geloven N, et al. Deprescribing preventive cardiovascular medication in patients with predicted low cardiovascular disease risk in general practice - the ECSTATIC study: a cluster randomised non-inferiority trial. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moonen JE, Foster-Dingley JC, de Ruijter W, et al. Effect of Discontinuation of Antihypertensive Treatment in Elderly People on Cognitive Functioning--the DANTE Study Leiden: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1622–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song W, Intrator O, Lee S, Boockvar K. Antihypertensive Drug Deintensification and Recurrent Falls in Long-Term Care. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(6):4066–4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr EA, Lucatorto MA, Holleman R, et al. Monitoring performance for blood pressure management among patients with diabetes mellitus: too much of a good thing? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(12):938–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Min L, Ha JK, Aubert CE, et al. A Method to Quantify Mean Hypertension Treatment Daily Dose Intensity Using Health Care System Data. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Min L, Ha JK, Hofer TP, et al. Validation of a Health System Measure to Capture Intensive Medication Treatment of Hypertension in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e205417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;71(19):e127–e248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sonmez A, Tasci I, Demirci I, et al. A Cross-Sectional Study of Overtreatment and Deintensification of Antidiabetic and Antihypertensive Medications in Diabetes Mellitus: The TEMD Overtreatment Study. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11(5):1045–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shawahna R, Odeh M, Jawabreh M. Factors Promoting Clinical Inertia in Caring for Patients with Dyslipidemia: A Consensual Study Among Clinicians who Provide Healthcare to Patients with Dyslipidemia. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111(1):18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Veterans Affairs - Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis and management of hypertension in the primary care setting. Version 4.0 - 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Min L CW, Sussman J, Maciejewski M, Kim M, Hofer T, Kerr E, Ha J, Langa K, Tinetti M. Cardiovascular, death, fall injury, & syncope outcomes of high-intensity BP medications [abstract]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(S1):176.31617581 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Min L, Ha J-K, Hofer TP, et al.Validation of a Health System Measure To Capture Intensive Medication Treatment of Hypertension. JAMA Int Med (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grymonpre R, Cheang M, Fraser M, Metge C, Sitar DS. Validity of a prescription claims database to estimate medication adherence in older persons. Med Care. 2006;44(5):471–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anghel LA, Farcas AM, Oprean RN. An overview of the common methods used to measure treatment adherence. Med Pharm Rep. 2019;92(2):117–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Individual patient data are not available for sharing by our data use agreement with the Department of Veterans Affairs.